1. Introduction

COVID-19, caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, was first

identified in December 2019 in Wuhan, China, marking the onset of a global

pandemic [

1]. Initially characterized

primarily as a respiratory infection, subsequent investigations have

demonstrated that COVID-19’s impact extends beyond the respiratory system.

Research has indicated that the virus can infiltrate the central nervous system

(CNS), leading to a range of neuropsychiatric and neurological complications [

2]. The spectrum of neuropsychiatric manifestations

associated with COVID-19 is significant. A meta-analysis encompassing 27

studies revealed alarming prevalence rates for various mental health disorders

among COVID-19 survivors. Specifically, the rates of Post-Traumatic Stress

Disorder (PTSD), anxiety, psychological distress, depression, and sleep

disorders were found to be 20% (95% CI = 16–24%), 22% (95% CI = 18–27%), 36%

(95% CI = 22–51%), 21% (95% CI = 16–28%), and 35% (95% CI = 29–41%)

respectively, based on a cohort of 9,605 individuals who had recovered from

COVID-19 [

3].

Cognitive impairment and psychopathological

symptoms have been documented in patients recovering from the acute phase of

COVID-19 [

4,

5]. Research indicates that these

negative effects may persist over time. For instance, a study revealed that

COVID-19 patients exhibited declining performance in reaction time tasks,

alongside lower mental health scores and higher fatigue indices, extending

beyond two years post-recovery [

6].

Furthermore, these adverse effects are not limited to older populations; they

can also impact younger individuals. A study focusing on young university

students demonstrated that 39 months after recovery, both the infection itself

and its severity had detrimental effects on their overall health. Additionally,

there was a negative correlation observed between the severity of COVID-19 and

cognitive performance among these students [

7].

Research has identified brain structural changes, neuroinflammation, and viral

invasiveness as potential contributors to long-term neurological and mental

health adversities associated with these infections [

8].

Furthermore, more recent evidence suggests that the adverse effects can last

for more than four years following the initial infection [

9,

10].

In this respect, several studies have investigated

the mental health impact of COVID-19 infection on patients post-recovery;

however, many of these studies either did not employ a validated questionnaire

to assess the adverse effects on patients’ mental health or overlooked it

altogether (e.g.,[

6,

11]). Consequently, the present study aims to

further explore this relationship by utilizing a standardized instrument that

is widely recognized in psychiatric and psychological research. Additionally,

this research intends to focus on young individuals with a history of mild to

moderate COVID-19, an area that remains relatively underexplored compared to

research involving elderly populations with severe COVID-19 histories.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

A total of 346 students from Bu-Ali Sina University

volunteered to participate in this cross-sectional study. Participants were

approached on the university campus and invited to engage in research focused

on individuals with a history of either mild or moderate COVID-19.

Specifically, mild cases were defined as those who had recovered at home

without requiring medical intervention, while moderate cases included

individuals who had received medical care at outpatient clinics.

Out of the initial cohort, 41 participants were

excluded from the study due to incomplete data or pre-existing mental health

disorders and also medical conditions known to affect mental health, such as

hyperthyroidism. Consequently, the final sample consisted of 305 subjects who

met the inclusion criteria and participated in this study.

2.2. Data Collection

Data were collected in person through the

administration of the ‘Symptom Checklist 90-Revised’ (SCL-90-R) to the

participants. Each participant received comprehensive information regarding the

study, including its objectives and significance. Based on the questionnaire’s

manual, instructions were provided to ensure that participants could accurately

complete the checklist [

12].

Before participating in the research, all

respondents were assured of their anonymity, and voluntary informed consent was

obtained from each individual. Participants were informed about the scope of

the study, its objectives, and the fact that the findings would be published as

an article in a scientific journal. They were also informed of their right to

withdraw from the study at any time without facing any conditions or

consequences.

The ethical conduct of this research adhered to the

principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.3. Instrument

The instrument utilized in this study was the Farsi

version of the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R). This self-report

questionnaire comprises 90 items, each rated on a five-point Likert scale,

where responses range from 0 (“None”) to 4 (“Extreme”). The SCL-90-R is in part

structured around nine primary symptom dimensions: Somatization (SOM),

Obsessive-Compulsive (O-C), Interpersonal Sensitivity (INS), Depression (DEP),

Anxiety (ANX), Hostility (HOS), Phobic Anxiety (PHO), Paranoid Ideation (PAR),

and Psychoticism (PSY) [

13].

The internal consistency coefficients for these

nine subscales have been reported to range from .76 to .88, with an overall

coefficient of .97, indicating high reliability of the instrument across its

various dimensions [

14].

2.4. Data Analysis

R (version 4.2.0) and SPSS (SPSS Statistics V26)

were utilized for the analysis of the data collected in this study. Descriptive

statistics were computed to provide a comprehensive overview of the sample

characteristics. To explore potential differences between participants based on

sex and severity of COVID-19, crosstabulation methods were employed.

Subsequently, a multivariate analysis of covariance

(MANCOVA), controlled for age, was performed to determine whether any

independent variables or their interactions could significantly forecast the

respondents’ scores on the dependent variables. Following the MANCOVA,

univariate models of covariance (ANCOVA), controlled for age, were examined for

each independent variable and their interactions to assess their possible

effects on each dependent variable.

Given concerns regarding normality and homogeneity

of variances, which were revealed through the descriptive analysis and the

Levene’s test, which assesses the assumption of equality of error variances,

the partial Kendall Tau correlational analysis, a non-parametric multivariate

analysis method, was employed, stratified by sex and controlled for age. These

non-parametric tests served to validate whether or not the findings from

parametric tests remained robust when the data did not follow a Gaussian distribution.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistical analysis revealed that the

participants had an average age of 22.80 years, and a mean duration of 15.18

months since infection. Among the psychological measures assessed, the

depression scale exhibited the highest mean score (15.90), followed by

somatization (14.01). In contrast, the phobic anxiety scale recorded the lowest

mean score (3.95) (

Table 1).

Crosstabulation analysis revealed that among the women included in the study

(total n = 156), 53.8% (n = 84) had experienced a mild case of COVID-19, while

46.2% (n = 72) had encountered its moderate form. For men (total n = 149), the

analysis showed that 57.7% (n = 86) had experienced mild COVID-19, whereas

42.3% (n = 63) had undergone its moderate form. When examining the distribution

of mild cases across these two sexes (total n = 170), it was observed that

49.4% (n = 86) were men, and 50.6% (n = 84) were women. For moderate cases

(total n = 135), the proportions shifted slightly, with 53.3% (n = 72) being

women and 47.7% (n = 63) being men. The chi-square test conducted to evaluate

these differences did not yield statistically significant results (

χ2(1) =

0.463, p = 0.496).

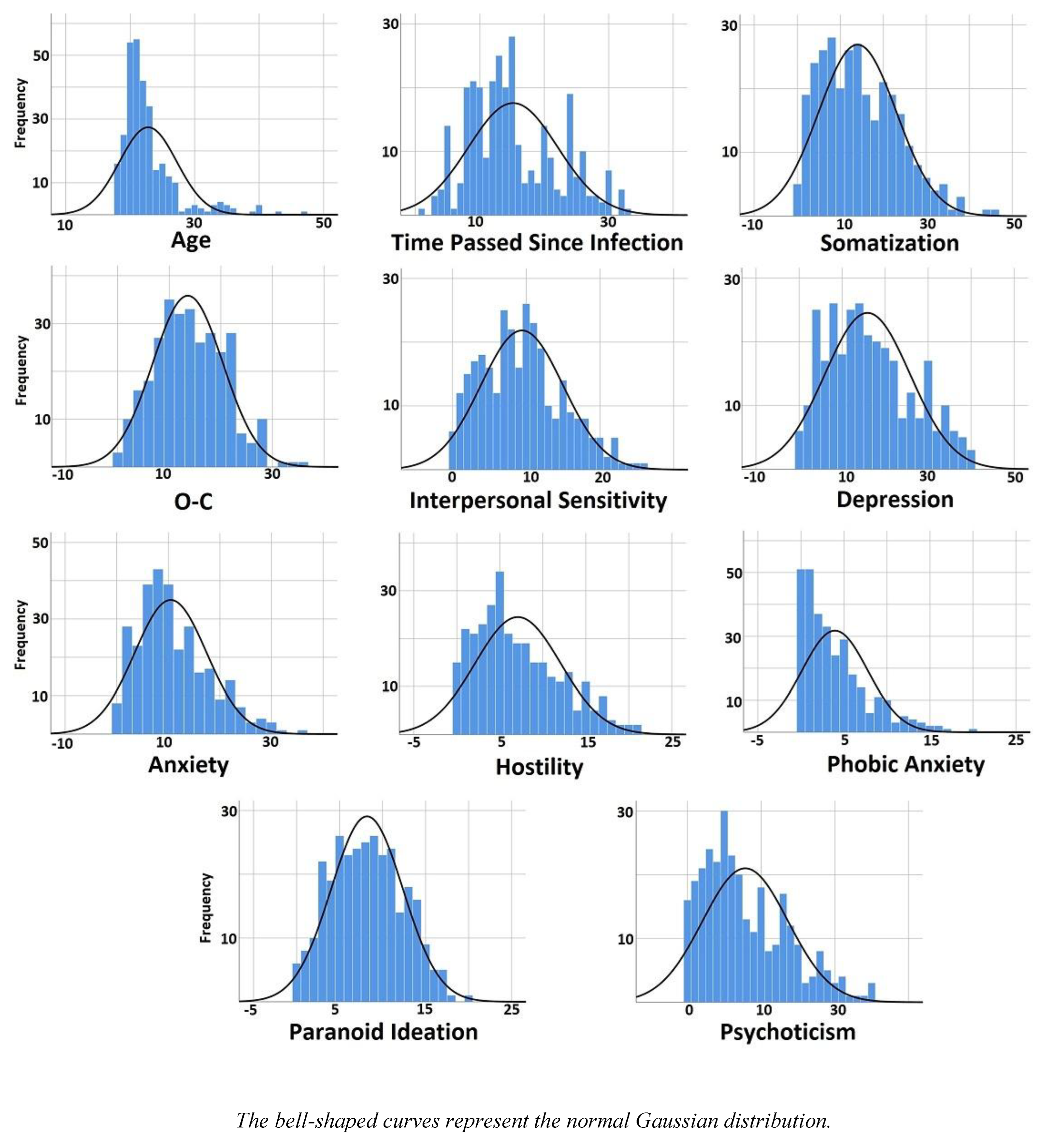

In addition, an examination of the skewness values and histograms of the dataset indicated that the distributions did not conform to a Gaussian model (

Table 1 and

Figure 1).

3.2. MANCOVA Results

To elucidate the potential effects of the

independent variables on the dependent variables, a MANCOVA was conducted,

while controlling for age as a covariate.

The results showed that two models were statistically

significant. The first model identified the time passed since COVID-19

infection (TPSI) as a significant independent variable, with F

(270, 1845)

= 1.197, p = 0.022, and a partial eta squared value of 0.149, suggesting a

moderate effect size. The second model demonstrated that sex was also a

significant independent variable, with F

(9, 197) = 2.442, p = 0.012,

and a partial eta squared value of 0.100, indicating a small to moderate effect

size. However, none of the other independent variables or their interactions

reached statistical significance (

Table 2).

Table 2.

MANCOVA results for the independent variables and their interactions with regard to the scales of the SCL-90-R.

Table 2.

MANCOVA results for the independent variables and their interactions with regard to the scales of the SCL-90-R.

| Effect |

Value |

F |

Hypothesis df |

Error df |

Sig. |

Partial Eta Squared |

| Intercept |

Pillai's Trace |

0.167 |

4.373 |

9 |

197 |

0.000 |

0.167 |

| Age |

Pillai's Trace |

0.027 |

0.609 |

9 |

197 |

0.789 |

0.027 |

| TPSI |

Pillai's Trace |

1.342 |

1.197 |

270 |

1845 |

0.022 |

0.149 |

| Severity |

Pillai's Trace |

0.042 |

0.962 |

9 |

197 |

0.472 |

0.042 |

| Sex |

Pillai's Trace |

0.100 |

2.442 |

9 |

197 |

0.012 |

0.100 |

| TPSI * Severity |

Pillai's Trace |

1.036 |

1.026 |

234 |

1845 |

0.386 |

0.115 |

| TPSI * Sex |

Pillai's Trace |

0.951 |

0.969 |

225 |

1845 |

0.614 |

0.106 |

| Severity * Sex |

Pillai's Trace |

0.077 |

1.822 |

9 |

197 |

0.066 |

0.077 |

| TPSI * Severity * Sex |

Pillai's Trace |

0.475 |

0.816 |

126 |

1845 |

0.931 |

0.053 |

3.3. ANCOVA Results

To further explore these findings, ANCOVA models for each dependent variable were constructed to identify which independent variables had a statistically significant impact on the dependent variables under consideration (

Table S1). The findings demonstrated that sex had a statistically significant effect on Somatization (F

(1) = 10.186, p = 0.002, partial η² = 0.047), which suggests that differences in Somatization symptoms are influenced by sex, with a moderate effect size.

The duration of time elapsed since infection significantly affected several psychological dimensions. Specifically, it had a notable impact on Interpersonal Sensitivity (F(30) = 1.529, p = 0.046, partial η² = 0.183), Depression (F(30) = 1.939, p = 0.004, partial η² = 0.221), and Anxiety (F(30) = 1.829, p = 0.008, partial η² = 0.211), which indicate that this variable plays a role in shaping these psychological outcomes, with large effect sizes observed for Depression and Anxiety in particular. Additionally, its influence on O-C approached statistical significance (F(30) = 1.492, p = 0.057, partial η² = 0.179), suggesting a potential trend.

The severity of COVID-19 was found to significantly affect multiple psychological variables. It had a significant impact on Somatization (F(1) = 6.277, p = 0.013, partial η² = 0.030), O-C (F(1) = 3.942, p = 0.048, partial η² = 0.019), and Anxiety (F(1) = 4.866, p = 0.028, partial η² = 0.023), the effect sizes were small to moderate for these variables. Furthermore, the severity of COVID-19 showed an almost significant relationship with Psychoticism scores (F(1) = 3.825, p = 0.052, partial η² = 0.018). While this result did not reach conventional thresholds for statistical significance (p < 0.05), it indicates a possible association trend between disease severity and Psychoticism.

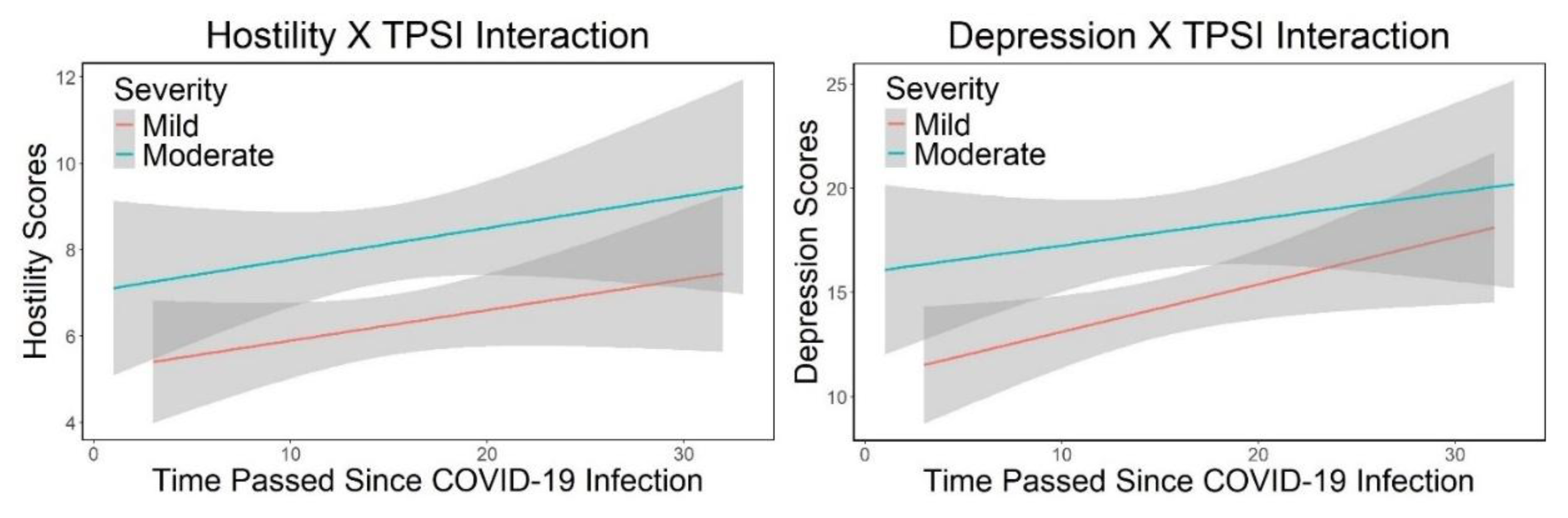

Further examination of the statistical models revealed that the interaction between the duration of time since infection and the severity of the disease was statistically significant for Depression (F

(26) = 2.158, p = 0.002, partial η² = 0.215) and Hostility (F

(26) = 1.578, p = 0.043, partial η² = 0.167). The interaction plots for the examined variables indicated that the interaction effect was more pronounced and obvious for depression than for hostility (

Figure 2). Depression scores were consistently lower in mild cases compared to moderate cases; however, there was a notable increase in depression scores over time since infection, particularly from month 10 onwards. This increase was steeper in mild cases when compared to moderate cases. In contrast, hostility scores displayed a relatively stable gradient of increase over time, with the interaction effect being prominently less obvious.

3.4. Partial Kendall Tau Results

To validate the aforementioned findings, the multivariate non-parametric test known as Partial Kendall Tau correlational method was utilized. This statistical method was employed to examine whether the observed results remained consistent when analyzed within a non-parametric framework. The use of Partial Kendall Tau is particularly advantageous in scenarios where the assumptions of parametric tests may not be met, allowing for a robust assessment of the relationships among multiple variables without relying on normality or homogeneity of variances. In addition, it allows researchers to analyze associations between binary, ordinal, and continuous variables. The application of this test involved calculating the partial correlation coefficients that quantify the strength and direction of associations between the independent and dependent variables while controlling for age.

3.4.1. All Participants

For all participants regardless of their sex, the findings indicated that there were positive and statistically significant correlations between age and O-C. Additionally, a positive and significant relationship was observed between the duration since COVID-19 infection and various scales, including O-C, Interpersonal Sensitivity, Depression, Anxiety, Hostility, and Paranoid Ideation. Furthermore, the severity of COVID-19 infection demonstrated significant positive correlations with Somatization, O-C, Interpersonal Sensitivity, Depression, Anxiety, Hostility, Phobic Anxiety, Paranoid Ideation, and Psychoticism. Lastly, sex was found to have a negative and significant correlation with Somatization, O-C, Interpersonal Sensitivity, Depression, and Anxiety. It is important to note that in this study, men were coded as 1 and women as -1; thus, the negative correlation associated with sex suggests that women exhibited higher scores on these scales compared to their men (

Table 3).

3.4.2. Men

Amongst men, it was found that the duration since the initial infection was positively and significantly correlated with levels of hostility. The positive correlation indicates that as the time since the initial COVID-19 infection increases, levels of hostility among men also tended to increase. Furthermore, the severity of the COVID-19 infection exhibited significant positive correlations with various scales, including somatization, O-C, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism. These imply that individuals who experienced more severe symptoms during their illness were likely to report higher levels of psychological distress across multiple dimensions. (

Table 3).

3.4.3. Women

For women, the duration of time elapsed since infection with the virus exhibited a significant positive correlation with Interpersonal Sensitivity, Depression, and Anxiety. This means that as the time since infection increased, women tended to experience higher levels of sensitivity in their interactions with others, along with increased feelings of depression and anxiety. Furthermore, the severity of the COVID-19 infection was also significantly and positively correlated with various scales, including Somatization, O-C, Depression, Anxiety, Hostility, Paranoid Ideation, and Psychoticism. This suggests that individuals experiencing more severe COVID-19 symptoms reported higher scores on these scales (

Table 3).

4. Discussion

This study examined the influence of the duration since COVID-19 infection TPSI, the severity of the infection, and sex, while controlling for age, among university students who experienced mild to moderate courses of COVID-19.

4.1. Sex

The results from MANCOVA indicated that sex had statistically significant associations with the scales of the SCL-90-R. Furthermore, ANCOVA revealed that sex significantly affected Somatization. To explore these relationships further, partial Kendall Tau correlations demonstrated a negative association between sex and Somatization. When considering the coding for sex (-1 for women and 1 for men), this finding suggested that there was a correlation indicating higher somatization scores among women relative to men. Additionally, partial correlational analysis indicated that there were significant correlations between being a woman and higher levels of O-C, Interpersonal Sensitivity, Depression, and Anxiety compared to being a man.

These findings align with previous research indicating that COVID-19 infection is correlated with more severe acute inflammatory symptoms in men, whereas women tend to exhibit long-term symptoms associated with autoimmune responses. For instance, in this regard, increased expression of XIST, an RNA gene linked to autoimmunity during infection in women [

15], involving neurological complications [

16], has been suggested as the underlying causal link. Other factors, such as psychobiological elements, also appear to mediate these associations more significantly in women; a prominent example of this is depression [

17].

4.2. Time Passed Since COVID-19 Infection (TPSI)

There was a significant interaction between TPSI and the severity of COVID-19 infection concerning Depression and Hostility. In terms of Depression, the findings suggested that as TPSI increased, there was a more pronounced increase in depression scores among individuals with mild cases compared to those with moderate cases. However, it is noteworthy that overall depression scores remained higher for individuals with a history of moderate COVID-19 infection. Regarding Hostility, while overall scores were higher for moderate cases, the interaction effect was less pronounced compared to that observed for Depression.

Further post-hoc partial Kendall Tau correlations indicated that as the TPSI increased, scores for O-C symptoms, Interpersonal Sensitivity, Depression, Anxiety, Hostility, and Paranoid Ideation also exhibited an upward trend. A separate analysis of these associations by sex revealed that with increasing TPSI, men’s scores in Hostility rose, while women’s scores in Interpersonal Sensitivity, Depression, and Anxiety increased. These findings align with existing literature suggesting that mental health deterioration along the trajectory of time elapsed since COVID-19 infection is observed in patients with a history of COVID-19 infection [

10,

18,

19]. Furthermore, the current study demonstrates that these associations are more prevalent in women than in men. This finding is consistent with previous research [

20].

The persistent effects of COVID-19 beyond the acute phase of infection are believed to arise from several factors, including the persistence of SARS-CoV-2, direct damage to organs, disturbances in both the innate and adaptive immune systems, autoimmunity, reactivation of latent viruses, endothelial dysfunction, and alterations in the microbiome (for a comprehensive review, see [

21]).

Variations in associations related to sex, concerning the relationships between TPSI and the above-mentioned scales, may stem from a range of influences. These include pathophysiological differences between men and women concerning COVID-19 infection [

15], psychological disparities between individuals experiencing long-COVID and those who do not [

22], as well as sociocultural determinants that affect these outcomes [

23].

4.3. Severity of COVID-19 Infection

The findings indicate that the severity of COVID-19 is significantly associated with somatization, O-C, and anxiety. This observation aligns with previous research suggesting that the severity of COVID-19 infection may be a contributing factor to long COVID [

7], [

24]. The robust results obtained from the partial Kendall Tau correlation analysis demonstrated a significant association between COVID-19 severity and various scales, including somatization, O-C, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism.

Separate analyses for men revealed similar associations; however, the correlation with phobic anxiety was not observed. For women, the results were largely consistent with those of men. Nonetheless, in addition to phobic anxiety, interpersonal sensitivity did not show a significant correlation among women. These findings corroborate existing literature that has identified a relationship between the severity of COVID-19 and psychiatric outcomes associated with long COVID (e.g. [

11], [

25]).

The observed effects are likely attributed to anatomical damage and neuroinflammation [

26], as well as dysregulation of neurotransmitters, with a particular emphasis on serotonin [

27].

4.4. Strengths

This study involved 305 participants, which provides a relatively large sample size. A large sample size can enhance the reliability and generalizability of the results. In addition, the inclusion of multiple independent variables (TPSI, severity of COVID-19, and sex) allowed for a relatively comprehensive examination of factors that might be associated with mental health outcomes as measured by the SCL-90-R, which is a well-established assessment tool. Utilizing validated instrument lends credibility to the findings and allows for comparisons with other studies in the field.

By employing non-parametric partial Kendall tau to check the results, it became possible to take steps to validate the findings against potential violations of parametric test assumptions, adding robustness to the conclusions.

Targeting university students offered valuable insights into a specific demographic relatively understudied in long-COVID research. This group is characterized by being young, generally healthy, and less likely to have experienced severe COVID-19 compared to older age cohorts.

4.5. Limitations

As a cross-sectional study, it captured data at one point in time, making it challenging to establish temporal relationships between independent and dependent variables. In this sense, longitudinal studies would be more effective in assessing changes over time and establishing causality. Accordingly, the findings in this article are presented in terms of associations rather than causal relationships.

The reliance on self-reported measures from participants can introduce bias due to social desirability or recall bias; however, ensuring anonymity during the completion of the questionnaire should have helped to mitigate this limitation to a large degree. Furthermore, self-reported surveys represent a widely accepted, cost-effective, and accessible methodology employed in mental health research involving large sample sizes.

The absence of a control group (individuals without a history of COVID-19) limited the ability to draw causal inferences about the effects of COVID-19 on mental health outcomes, to determine whether observed effects are specifically attributable to COVID-19 or other confounding factors. Accordingly, the interpretations and conclusions of the findings presented in this article are framed in terms of associations rather than causal relationships.

The recruitment of participants from a university campus may restrict the generalizability of the findings beyond this particular demographic group. However, this study was deliberately designed to focus on this often-overlooked cohort, exploring the relationships between COVID-19 infection and its long-term impacts on mental health in young adults.

Although age was controlled for in the analyses and participants with pre-existing mental or physical health conditions were excluded, and the homogeneity of the cohort may have provided a similar contextual background for all participants, it remains possible that unknown confounding factors could have influenced the results independently of COVID-19 infection history. Research in the human and social sciences is vulnerable to confounding variables, in contrast to experimental natural sciences that are conducted under rigorously controlled laboratory conditions. However, it is also crucial to acknowledge that these confounding effects can be largely mitigated through careful study design. This includes controlling for confounding variables, filtering participants, and incorporating relevant independent variables into the study, as was tried to be done in the current research.

5. Conclusions

Investigation of the long-term effects of COVID-19 is an emerging area in health sciences, mostly pointing to the importance of studying and monitoring the relevant conditions in vulnerable populations. However, the present study’s findings, along with the emerging literature, suggests that these considerations should be also extended to the young adults among other age groups. The findings of the present study show that severity of COVID-19 infection and the time passed since the acute phase of the disease are positively associated with higher scores in the scales of SCL-90-R. In addition, the findings indicate that being a woman is more strongly associated with these long-term post-infection complications compared to being a man. Accordingly, it is suggested that in the investigation of mental health issues, factors such as sex, the severity of COVID-19, and the duration of time elapsed since infection be considered as risk factors.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1: ANCOVA results for the dependent variables and their interactions with regard to the scales of the SCL-90-R.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A. L.; methodology, A. L.; validation, A. L.; formal analysis, A. L.; investigation, A. L.; data curation, A. L.; writing—original draft preparation, A. L.; writing—review and editing, A. L.; visualization, A. L.; supervision, A. L.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The author would like to express his sincere gratitude for the enthusiastic participation of the students from Bu-Ali Sina University in Hamedan in this research study. The author also wishes to convey his appreciation to Dr. Mohammad Reza Zoghipaydar for his invaluable guidance.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TPSI |

Time passed since COVID-19 Infection |

| O-C |

Obsessive-Compulsive |

References

- C. Huang et al., “Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China,” The Lancet, vol. 395, no. 10223, pp. 497–506, Feb. 2020, doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [CrossRef]

- H. Solomon et al., “Neuropathological Features of Covid-19,” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 383, no. 10, pp. 989–992, Sep. 2020, doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2019373. [CrossRef]

- B. Khraisat, A. Toubasi, L. AlZoubi, T. Al-Sayegh, and A. Mansour, “Meta-analysis of prevalence: the psychological sequelae among COVID-19 survivors,” Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract, vol. 26, no. 3, pp. 234–243, Sep. 2022, doi: 10.1080/13651501.2021.1993924. [CrossRef]

- T. Nasserie, M. Hittle, and S. N. Goodman, “Assessment of the Frequency and Variety of Persistent Symptoms Among Patients With COVID-19,” JAMA Netw Open, vol. 4, no. 5, p. e2111417, May 2021, doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.11417. [CrossRef]

- M. Cai, Y. Xie, E. J. Topol, and Z. Al-Aly, “Three-year outcomes of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19,” Nat Med, vol. 30, no. 6, pp. 1564–1573, Jun. 2024, doi: 10.1038/s41591-024-02987-8. [CrossRef]

- J. Flegr and A. Latifi, “COVID’s long shadow: How SARS-CoV-2 infection, COVID-19 severity, and vaccination status affect long-term cognitive performance and health,” Biol Methods Protoc, vol. 8, no. 1, Jan. 2023, doi: 10.1093/biomethods/bpad038. [CrossRef]

- Latifi and J. Flegr, “Is recovery just the beginning? Persistent symptoms and health and performance deterioration in post-COVID-19, non-hospitalized university students—a cross-sectional study,” Biol Methods Protoc, vol. 8, no. 1, Jan. 2023, doi: 10.1093/biomethods/bpad037. [CrossRef]

- P. Jin, F. Cui, M. Xu, Y. Ren, and L. Zhang, “Altered brain function and structure pre- and post- COVID-19 infection: a longitudinal study,” Neurological Sciences, vol. 45, no. 1, pp. 1–9, Jan. 2024, doi: 10.1007/s10072-023-07236-3. [CrossRef]

- T. Iba, J. H. Levy, C. L. Maier, J. M. Connors, and M. Levi, “Four years into the pandemic, managing COVID-19 patients with acute coagulopathy: what have we learned?,” Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis, vol. 22, no. 6, pp. 1541–1549, Jun. 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.jtha.2024.02.013. [CrossRef]

- Latifi and J. Flegr, “Persistent Health and Cognitive Impairments up to Four Years Post-COVID-19 in Young Students: The Impact of Virus Variants and Vaccination Timing,” Biomedicines, vol. 13, no. 1, p. 69, Dec. 2024, doi: 10.3390/biomedicines13010069. [CrossRef]

- S. Kim et al., “Short- and long-term neuropsychiatric outcomes in long COVID in South Korea and Japan,” Nat Hum Behav, vol. 8, no. 8, pp. 1530–1544, Jun. 2024, doi: 10.1038/s41562-024-01895-8. [CrossRef]

- D. LR., “SCL-90-R : administration, scoring and procedures,” Manual II for the R (evised) Version and Other Instruments of the Psychopathology Rating Scale Series, 1983, Accessed: Dec. 25, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1573387450267334400.

- D. LR, “SCL-90 : an outpatient psychiatric rating scale-preliminary report,” Psychopharmacol Bull, vol. 9, pp. 13–28, 1973, doi: 10.15064/JJPM.53.4_334. [CrossRef]

- F. Akhavan Abiri and M. R. Shairi, “Validity and Reliability of Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R) and Brief Symptom Inventory-53 (BSI-53),” Clinical Psychology and Personality, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 169–195, Sep. 2020, doi: 10.22070/CPAP.2020.2916. [CrossRef]

- R. E. Hamlin et al., “Sex differences and immune correlates of Long Covid development, symptom persistence, and resolution,” Sci Transl Med, vol. 16, no. 773, Nov. 2024, doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.adr1032. [CrossRef]

- Gorenshtein, L. Leibovitch, T. Liba, S. Stern, and Y. Stern, “Gender Disparities in Neurological Symptoms of Long COVID: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” Neuroepidemiology, pp. 1–15, Aug. 2024, doi: 10.1159/000540919. [CrossRef]

- J. Matta et al., “Depressive symptoms and sex differences in the risk of post-COVID-19 persistent symptoms: a prospective population-based cohort study,” Nature Mental Health, vol. 2, no. 9, pp. 1053–1061, Jul. 2024, doi: 10.1038/s44220-024-00290-6. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, V. M. Chinchilli, P. Ssentongo, and D. M. Ba, “Association of Long COVID with mental health disorders: a retrospective cohort study using real-world data from the USA,” BMJ Open, vol. 14, no. 2, p. e079267, Feb. 2024, doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2023-079267. [CrossRef]

- J. D. Bremner, S. J. Russo, R. Gallagher, and N. M. Simon, “Acute and long-term effects of COVID-19 on brain and mental health: A narrative review,” Brain Behav Immun, vol. 123, pp. 928–945, Jan. 2025, doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2024.11.007. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Onieva, C. A. Soto Castro, V. García Morales, M. Aneri Vacas, and A. Hidalgo Requena, “Long COVID: Factors influencing persistent symptoms and the impact of gender,” Medicina de Familia. SEMERGEN, vol. 50, no. 5, p. 102208, Jul. 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.semerg.2024.102208. [CrossRef]

- Skevaki, C. D. Moschopoulos, P. C. Fragkou, K. Grote, E. Schieffer, and B. Schieffer, “Long COVID: Pathophysiology, current concepts, and future directions,” Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, Dec. 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2024.12.1074. [CrossRef]

- K. Sakai, S. Tarutani, T. Okamura, H. Yoneda, T. Kawasaki, and M. Takeda, “Comparing personality traits of healthcare workers with and without long COVID: Cross-sectional study,” Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences Reports, vol. 3, no. 4, Dec. 2024, doi: 10.1002/pcn5.70017. [CrossRef]

- C. E. Gebhard et al., “Impact of sex and gender on post-COVID-19 syndrome, Switzerland, 2020,” Eurosurveillance, vol. 29, no. 2, Jan. 2024, doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2024.29.2.2300200. [CrossRef]

- R. Van Cleve et al., “Risk of developing long COVID based on acute COVID-19 severity,” J Public Health (Bangkok), Nov. 2024, doi: 10.1007/s10389-024-02364-2. [CrossRef]

- S. Kananian, A. Nemani, and U. Stangier, “Risk and protective factors for the severity of long COVID – A network analytic perspective,” J Psychiatr Res, vol. 178, pp. 291–297, Oct. 2024, doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2024.08.031. [CrossRef]

- F. Couto Amendola et al., “A Two-Year cohort study examining the impact of cytokines and chemokines on cognitive and psychiatric outcomes in Long-COVID-19 patients,” Brain Behav Immun, vol. 124, pp. 218–225, Feb. 2025, doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2024.12.006. [CrossRef]

- U. Bonnet and J. Kuhn, “Serotonin deficiency and psychiatric long COVID: both caused specifically by the virus itself or an adaptive general stress response?,” Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci, Feb. 2024, doi: 10.1007/s00406-024-01769-0. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).