Submitted:

14 February 2025

Posted:

17 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Case Description

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ME/CFS | Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/ Chronic Fatigue Syndrome |

| MS | Multiple Sclerosis |

| MG | Myasthenia Gravis |

| HERV | Human Endogenous Retrovirus |

| HERV-W ENV | Human Endogenous Retrovirus type W (tryptophan), Envelope protein |

| MSRV | Multiple Sclerosis Retrovirus |

| PBMC | Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells |

| EBV | Epstein Bar Virus |

| AchR | Acetylcholine Receptor |

| aAb | Autoantibody |

References

- Harrison, J.E.; Weber, S.; Jakob, R.; Chute, C.G. ICD-11: An international classification of diseases for the twenty-first century. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2021, 21 (Suppl. S6), 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Carruthers, B.M.; van de Sande, M.I.; De Meirleir, K.L.; Klimas, N.G.; Broderick, G.; Mitchell, T.; et al. Myalgic encephalomyelitis: International consensus criteria. J Intern Med. 2011, 270, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carruthers, B.M.; Jain, A.K.; De Meirleir, K.L.; Peterson, D.L.; Klimas, N.G.; Lerner, A.; et al. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: Clinical working case definition, diagnostic and treatment protocols. J Chron Fatigue Syndr. 2003, 11, 7–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, E.W. Beyond myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: An IOM report on redefining an illness. JAMA. 2015, 313, 1101–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walton, C.; King, R.; Rechtman, L.; et al. Rising prevalence of multiple sclerosis worldwide: Insights from the Atlas of, M.S.; third edition. Mult Scler. 2020, 26, 1816–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwibel, H.L.; Smrtka, J. Improving quality of life in multiple sclerosis: An unmet need. Am J Manag Care. 2011, 17 (Suppl. S5), S139. [Google Scholar]

- Lublin, F.D.; Reingold, S.C.; Cohen, J.A.; et al. Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: The 2013 revisions. Neurology 2014, 83, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalfari, A.; Neuhaus, A.; Degenhardt, A.; et al. The natural history of multiple sclerosis: A geographically based study 10: Relapses and long-term disability. Brain 2010, 133 Pt 7, 1914–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Confavreux, C.; Vukusic, S. Natural history of multiple sclerosis: A unifying concept. Brain 2006, 129 Pt 3, 606–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, M.; Kingwell, E.; Rieckmann, P.; et al. The natural history of secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2010, 81, 1039–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almenar-Pérez, E.; Sánchez-Fito, T.; Ovejero, T.; Nathanson, L.; Oltra, E. Impact of Polypharmacy on Candidate Biomarker miRNomes for the Diagnosis of Fibromyalgia and Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Striking Back on Treatments. Pharmaceutics. 2019, 11, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Montalban, X.; Gold, R.; Thompson, A.J.; Otero-Romero, S.; Amato, M.P.; Chandraratna, D.; et al. ECTRIMS/EAN guideline on the pharmacological treatment of people with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2018, 24, 96–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rae-Grant, A.; Day, G.S.; Marrie, R.A.; Rabinstein, A.; Cree, B.A.C.; Gronseth, G.S.; et al. Practice guideline recommendations summary: Disease-modifying therapies for adults with multiple sclerosis: Report of the guideline development, dissemination, and implementation subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2018, 90, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harding, K.; Williams, O.; Willis, M.; Hrastelj, J.; Rimmer, A.; Joseph, F.; et al. Clinical outcomes of escalation vs early intensive disease-modifying therapy in patients with multiple sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2019, 76, 536–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.W.L.; Coles, A.; Horakova, D.; Havrdova, E.; Izquierdo, G.; Prat, A.; et al. Association of initial disease-modifying therapy with later conversion to secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. JAMA. 2019, 321, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, A.; Merkel, B.; Brown, J.W.L.; Zhovits Ryerson, L.; Kister, I.; Malpas, C.B.; et al. Timing of high-efficacy therapy for multiple sclerosis: A retrospective observational cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2020, 19, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buron, M.D.; Chalmer, T.A.; Sellebjerg, F.; Barzinji, I.; Christensen, J.R.; Christensen, M.K.; et al. Initial high-efficacy disease-modifying therapy in multiple sclerosis: A nationwide cohort study. Neurology. 2020, 95, e1041–e1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spelman, T.; Magyari, M.; Piehl, F.; Svenningsson, A.; Rasmussen, P.V.; Kant, M.; et al. Treatment escalation vs immediate initiation of highly effective treatment for patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: Data from 2 different national strategies. JAMA Neurol. 2021, 78, 1197–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uher, T.; Krasensky, J.; Malpas, C.; Bergsland, N.; Dwyer, M.G.; Kubala Havrdova, E.; et al. Evolution of brain volume loss rates in early stages of multiple sclerosis. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2021, 8, e979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanninen, K.; Viitala, M.; Atula, S.; Laakso, S.M.; Kuusisto, H.; Soilu-Hanninen, M. Initial treatment strategy and clinical outcomes in Finnish MS patients: A propensity-matched study. J Neurol. 2022, 269, 913–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, A.K.; Amin, M.; Cohen, J.A. Drugs Targeting CD20 in Multiple Sclerosis: Pharmacology, Efficacy, Safety, and Tolerability. Drugs 2024, 84, 285–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

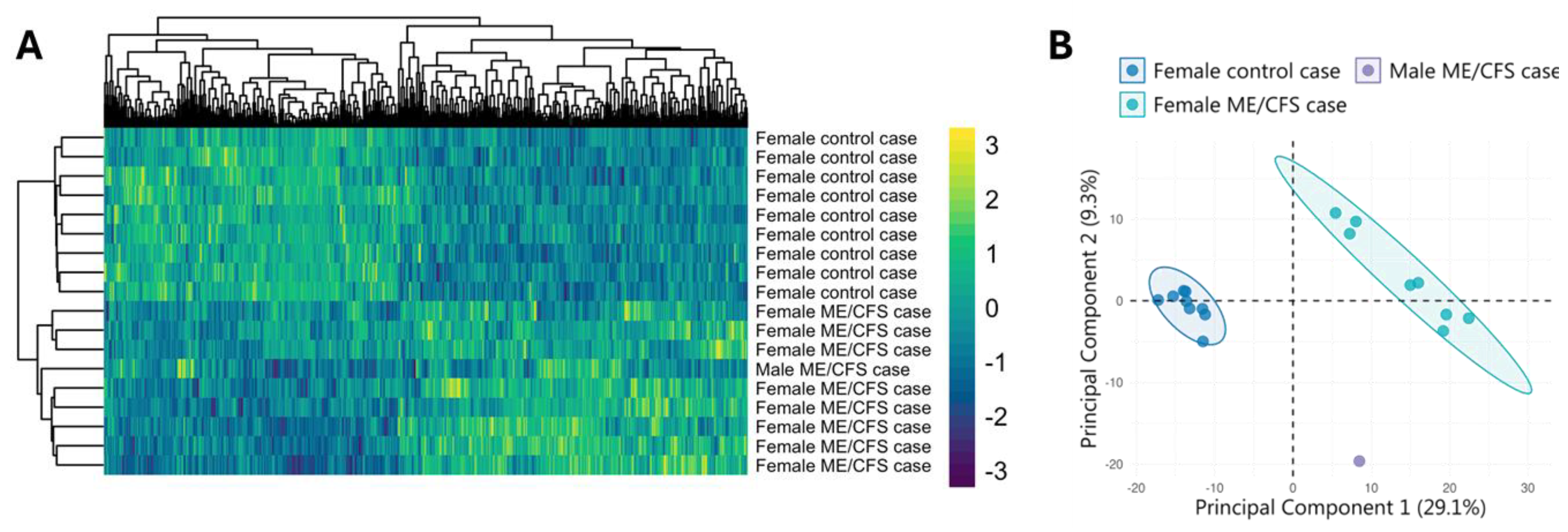

- Giménez-Orenga, K.; Martín-Martínez, E.; Nathanson, L.; Oltra, E. HERV activation segregates ME/CFS from fibromyalgia while defining a novel nosologic entity. eLife 2025, 14, RP104441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.J.; Banwell, B.L.; Barkhof, F.; Carroll, W.M.; Coetzee, T.; Comi, G.; Correale, J.; Fazekas, F.; Filippi, M.; Freedman, M.S.; Fujihara, K.; Galetta, S.L.; Hartung, H.P.; Kappos, L.; Lublin, F.D.; Marrie, R.A.; Miller, A.E.; Miller, D.H.; Montalban, X.; Mowry, E.M.; Sorensen, P.S.; Tintoré, M.; Traboulsee, A.L.; Trojano, M.; Uitdehaag, B.M.J.; Vukusic, S.; Waubant, E.; Weinshenker, B.G.; Reingold, S.C.; Cohen, J.A. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.T.; Wang, L.; Deng, X.Y.; Yu, G. Pharmacological treatments for fatigue in patients with multiple sclerosis: A sys-tematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol Sci. 2017, 380, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giménez-Orenga, K.; Oltra, E. Human Endogenous Retrovirus as Therapeutic Targets in Neurologic Disease. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Perron, H.; Lazarini, F.; Ruprecht, K.; Péchoux-Longin, C.; Seilhean, D.; Sazdovitch, V.; Créange, A.; Battail-Poirot, N.; Sibaï, G.; Santoro, L.; Jolivet, M.; Darlix, J.L.; Rieckmann, P.; Arzberger, T.; Hauw, J.J.; Lassmann, H. Human endogenous retrovirus (HERV)-W ENV and GAG proteins: Physiological expression in human brain and pathophysiological modulation in multiple sclerosis lesions. J Neurovirol. 2005, 11, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giménez-Orenga, K.; Pierquin, J.; Brunel, J.; Charvet, B.; Martín-Martínez, E.; Perron, H.; Oltra, E. HERV-W ENV antigenemia and correlation of increased anti-SARS-CoV-2 immunoglobulin levels with post-COVID-19 symptoms. Front Immunol. 2022, 13, 1020064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ritchie, M.E.; Phipson, B.; Wu, D.; Hu, Y.; Law, C.W.; Shi, W.; Smyth, G.K. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Becker, J.; Pérot, P.; Cheynet, V.; Oriol, G.; Mugnier, N.; Mommert, M.; Tabone, O.; Textoris, J.; Veyrieras, J.B.; Mallet, F. A comprehensive hybridization model allows whole HERV transcriptome profiling using high density microarray. BMC Genomics. 2017, 18, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kolde RLizee AMetsalu T.2018Pheatmap: Pretty heatmapsGitHub. Available online: https://github.com/raivokolde/pheatmap.

- Kassambara AMundt F.2019F actoextra: Extract and Visualize the Results of Multivariate Data AnalysesR package. Available online: https://rpkgs.datanovia.com/factoextra/index.html.

- Bhasin, J.M.; Ting, A.H. Goldmine integrates information placing genomic ranges into meaningful biological contexts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 5550–5556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machtoub, D.; Fares, C.; Sinan, H.; Al Hariri, M.; Nehme, R.; Chami, J.; Joukhdar, R.; Tcheroyan, R.; Adib, S.; Khoury, S.J. Factors affecting fatigue progression in multiple sclerosis patients. Sci Rep. 2024, 14, 31682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ridley, B.; Minozzi, S.; Gonzalez-Lorenzo, M.; Del Giovane, C.; Piggott, T.; Filippini, G.; Peryer, G.; Foschi, M.; Tramacere, I.; Baldin, E.; Nonino, F. Immunomodulators and immunosuppressants for progressive multiple sclerosis: A network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2024, 9, CD015443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fluge, Ø.; Risa, K.; Lunde, S.; Alme, K.; Rekeland, I.G.; Sapkota, D.; Kristoffersen, E.K.; Sørland, K.; Bruland, O.; Dahl, O.; Mella, O. B-Lymphocyte Depletion in Myalgic Encephalopathy/ Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. An Open-Label Phase II Study with Rituximab Maintenance Treatment. PLoS ONE. 2015, 10, e0129898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fluge, Ø.; Rekeland, I.G.; Lien, K.; Thürmer, H.; Borchgrevink, P.C.; Schäfer, C.; Sørland, K.; Aßmus, J.; Ktoridou-Valen, I.; Herder, I.; Gotaas, M.E.; Kvammen, Ø.; Baranowska, K.A.; Bohnen, L.M.L.J.; Martinsen, S.S.; Lonar, A.E.; Solvang, A.H.; Gya, A.E.S.; Bruland, O.; Risa, K.; Alme, K.; Dahl, O.; Mella, O. B-Lymphocyte Depletion in Patients With Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2019, 170, 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazaridis, K.; Tzartos, S.J. Myasthenia Gravis: Autoantibody Specificities and Their Role in MG Management. Front Neurol. 2020, 11, 596981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gilhus, N.E.; Andersen, H.; Andersen, L.K.; Boldingh, M.; Laakso, S.; Leopoldsdottir, M.O.; Madsen, S.; Piehl, F.; Popperud, T.H.; Punga, A.R.; Schirakow, L.; Vissing, J. Generalized myasthenia gravis with acetylcholine receptor antibodies: A guidance for treatment. Eur J Neurol. 2024, 31, e16229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- van Horssen, J.; van der Pol, S.; Nijland, P.; Amor, S.; Perron, H. Human endogenous retrovirus W in brain lesions: Rationale for targeted therapy in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2016, 8, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giménez-Orenga, K.; Pierquin, J.; Brunel, J.; Charvet, B.; Martín-Martínez, E.; Perron, H.; Oltra, E. HERV-W ENV antigenemia and correlation of increased anti-SARS-CoV-2 immunoglobulin levels with post-COVID-19 symptoms. Front Immunol. 2022, 13, 1020064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Madeira, A.; Burgelin, I.; Perron, H.; Curtin, F.; Lang, A.B.; Faucard, R. MSRV envelope protein is a potent, endogenous and pathogenic agonist of human toll-like receptor 4: Relevance of GNbAC1 in multiple sclerosis treatment. J Neuroimmunol. 2016, 291, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamer, J.; Van Booven, D.J.; Zarnowski, O.; Arango, S.; Elias, M.; Kurian, A.; Joseph, A.; Perez, M.; Collado, F.; Klimas, N.; Oltra, E.; Nathanson, L. Sex-Dependent Transcriptional Changes in Response to Stress in Patients with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A Pilot Project. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 10255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Germain, A.; Giloteaux, L.; Moore, G.E.; Levine, S.M.; Chia, J.K.; Keller, B.A.; Stevens, J.; Franconi, C.J.; Mao, X.; Shungu, D.C.; Grimson, A.; Hanson, M.R. Plasma metabolomics reveals disrupted response and recovery following maximal exercise in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. JCI Insight. 2022, 7, e157621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cheema, A.K.; Sarria, L.; Bekheit, M.; Collado, F.; Almenar-Pérez, E.; Martín-Martínez, E.; Alegre, J.; Castro-Marrero, J.; Fletcher, M.A.; Klimas, N.G.; Oltra, E.; Nathanson, L. Unravelling myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS): Gender-specific changes in the microRNA expression profiling in ME/CFS. J Cell Mol Med. 2020, 24, 5865–5877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Macchietto, M.G.; Langlois, R.A.; Shen, S.S. Virus-induced transposable element expression up-regulation in human and mouse host cells. Life Sci Alliance. 2020, 3, e201900536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bjornevik, K.; Cortese, M.; Healy, B.C.; Kuhle, J.; Mina, M.J.; Leng, Y.; Elledge, S.J.; Niebuhr, D.W.; Scher, A.I.; Munger, K.L.; Ascherio, A. Longitudinal analysis reveals high prevalence of Epstein-Barr virus associated with multiple sclerosis. Science. 2022, 375, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanz, T.V.; Brewer, R.C.; Ho, P.P.; Moon, J.S.; Jude, K.M.; Fernandez, D.; Fernandes, R.A.; Gomez, A.M.; Nadj, G.S.; Bartley, C.M.; Schubert, R.D.; Hawes, I.A.; Vazquez, S.E.; Iyer, M.; Zuchero, J.B.; Teegen, B.; Dunn, J.E.; Lock, C.B.; Kipp, L.B.; Cotham, V.C.; Ueberheide, B.M.; Aftab, B.T.; Anderson, M.S.; DeRisi, J.L.; Wilson, M.R.; Bashford-Rogers, R.J.M.; Platten, M.; Garcia, K.C.; Steinman, L.; Robinson, W.H. Clonally expanded B cells in multiple sclerosis bind EBV EBNA1 and GlialCAM. Nature 2022, 603, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Armangue, T.; Spatola, M.; Vlagea, A.; Mattozzi, S.; Cárceles-Cordon, M.; Martinez-Heras, E.; Llufriu, S.; Muchart, J.; Erro, M.E.; Abraira, L.; Moris, G.; Monros-Giménez, L.; Corral-Corral, Í.; Montejo, C.; Toledo, M.; Bataller, L.; Secondi, G.; Ariño, H.; Martínez-Hernández, E.; Juan, M.; Marcos, M.A.; Alsina, L.; Saiz, A.; Rosenfeld, M.R.; Graus, F.; Dalmau, J.; Spanish Herpes Simplex Encephalitis Study Group. Frequency, symptoms, risk factors, and outcomes of autoimmune encephalitis after herpes simplex encephalitis: A prospective observational study and retrospective analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17, 760–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Iversen, R.; Sollid, L.M. Dissecting autoimmune encephalitis through the lens of intrathecal B cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2024, 121, e2401337121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ruiz-Pablos, M.; Paiva, B.; Zabaleta, A. Epstein-Barr virus-acquired immunodeficiency in myalgic encephalomyelitis-Is it present in long COVID? J Transl Med. 2023, 21, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kasimir, F.; Toomey, D.; Liu, Z.; Kaiping, A.C.; Ariza, M.E.; Prusty, B.K. Tissue specific signature of HHV-6 infection in ME/CFS. Front Mol Biosci. 2022, 9, 1044964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- O'Neal, A.J.; Hanson, M.R. The Enterovirus Theory of Disease Etiology in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A Critical Review. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021, 8, 688486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Morris, G.; Maes, M. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome and encephalomyelitis disseminata/multiple sclerosis show remarkable levels of similarity in phenomenology and neuroimmune characteristics. BMC Med. 2013, 11, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Danikowski, K.M.; Jayaraman, S.; Prabhakar, B.S. Regulatory T cells in multiple sclerosis and myasthenia gravis. J Neuroinflammation. 2017, 14, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pérez-Carbonell, L.; Iranzo, A. Sleep Disturbances in Autoimmune Neurological Diseases. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2023, 23, 617–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).