Submitted:

17 February 2025

Posted:

19 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

To better understand adult neurogenesis, the biomolecular specificity of the subgranular zone should be investigated in comparison to other layers of the hippocampus. Adult neurogenesis occurs at a reduced rate in adulthood compared to the period of development, but it can be increased with exposure to enriched environment. This can be used to investigate the regulatory role of molecules present in the extracellular matrix, such as tenascin C. This study using Synchrotron radiation Fourier Transform Infrared spectroscopy (SR-FTIR) shows that the differences between the hippocampal layers in adolescence are maintained as subtle and significant in adulthood. Moreover, we have detected biomolecular changes that accompany the process of neurogenesis under the influence of enriched environment, while these effects are lacking in mice with a gene ablation for tenascin C.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Experimental Paradigm for Enriched Environment

2.3. Synchrotron-Based FTIR Spectroscopy and Imaging

2.3.1. Tissue Preparation

2.3.2. SR-FTIR Spectroscopy

2.3.3. Data Analysis

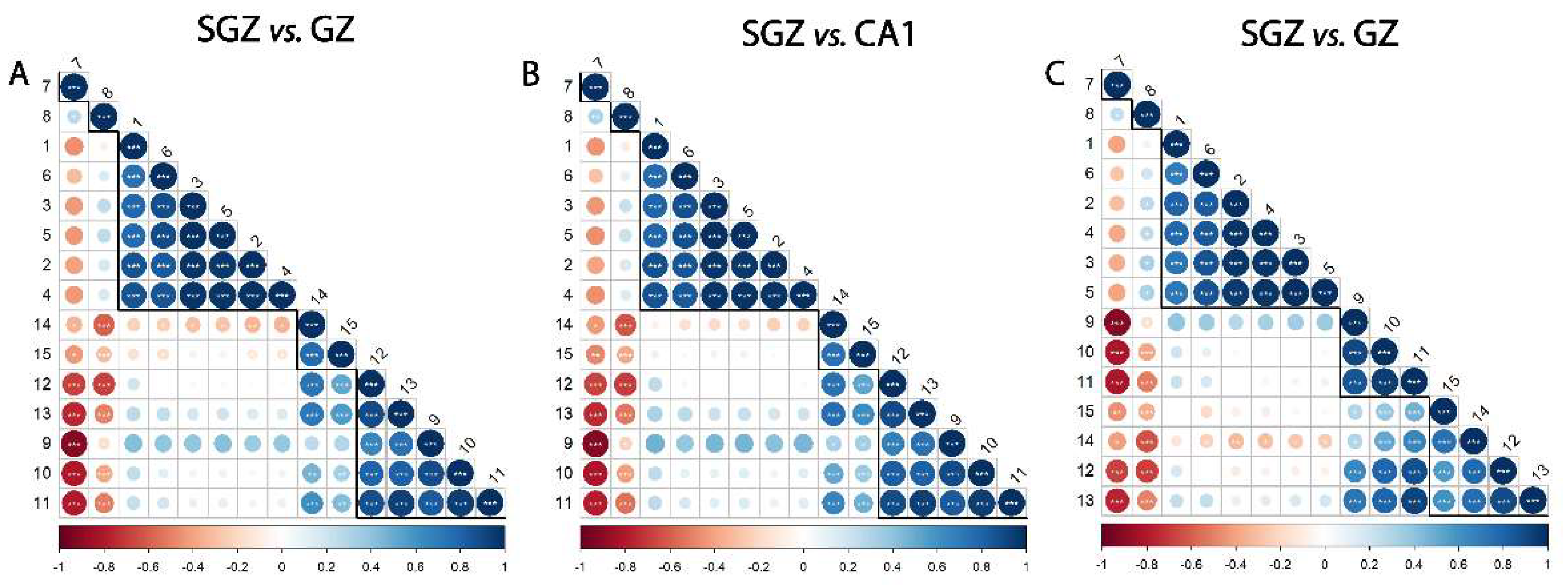

2.3.3.1. Correlation Analysis

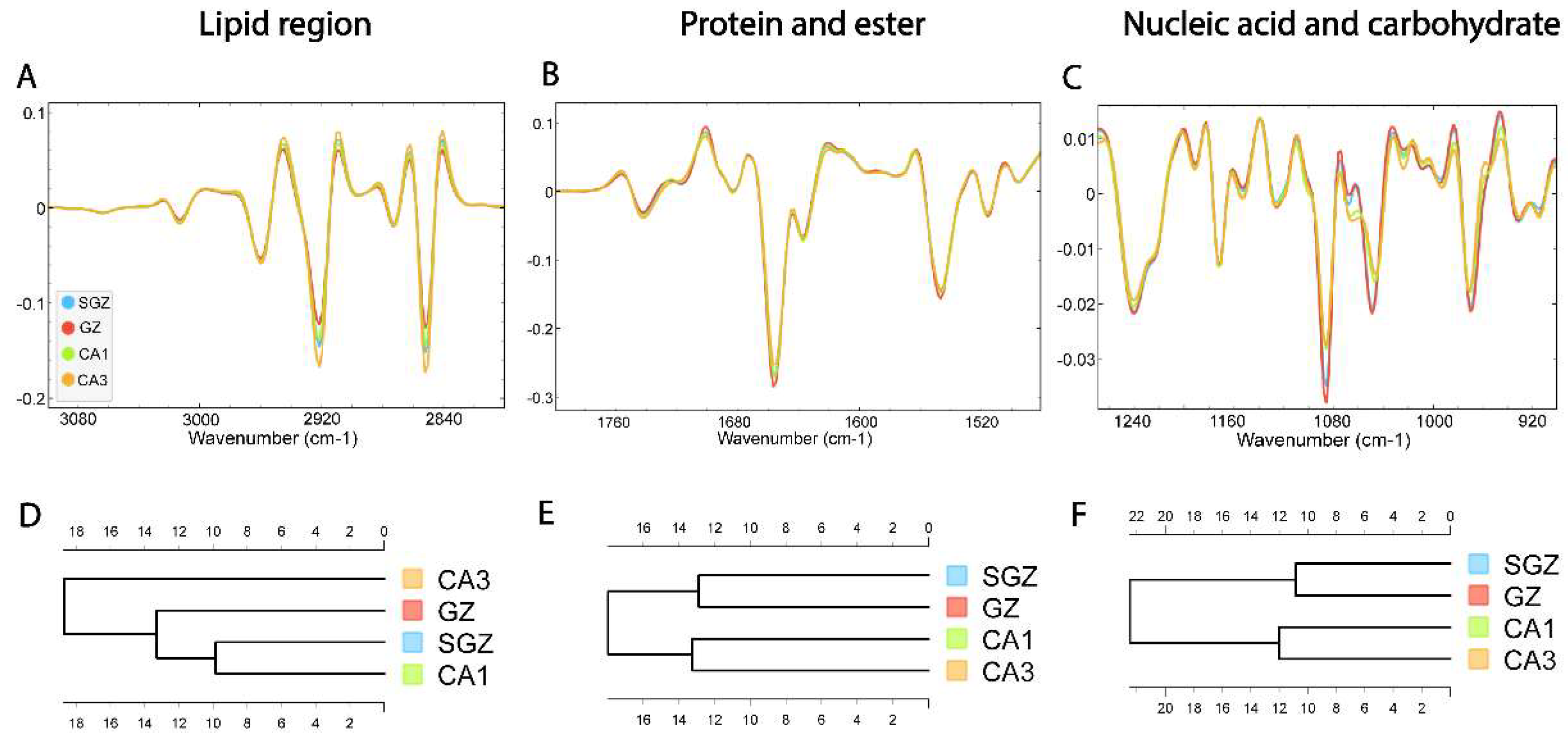

2.3.3.2. Hierarchical Cluster Analysis

2.3.3.3. Principal Component Analysis

2.3.3.4. Linear Discriminant Analysis

2.3.3.5. Random Forest

2.3.3.5. Statistics

2.4. Immunofluorescence

2.4.1. Tissue Preparation and Immunostaining

2.4.1. Tissue Preparation and Immunostaining

3. Results

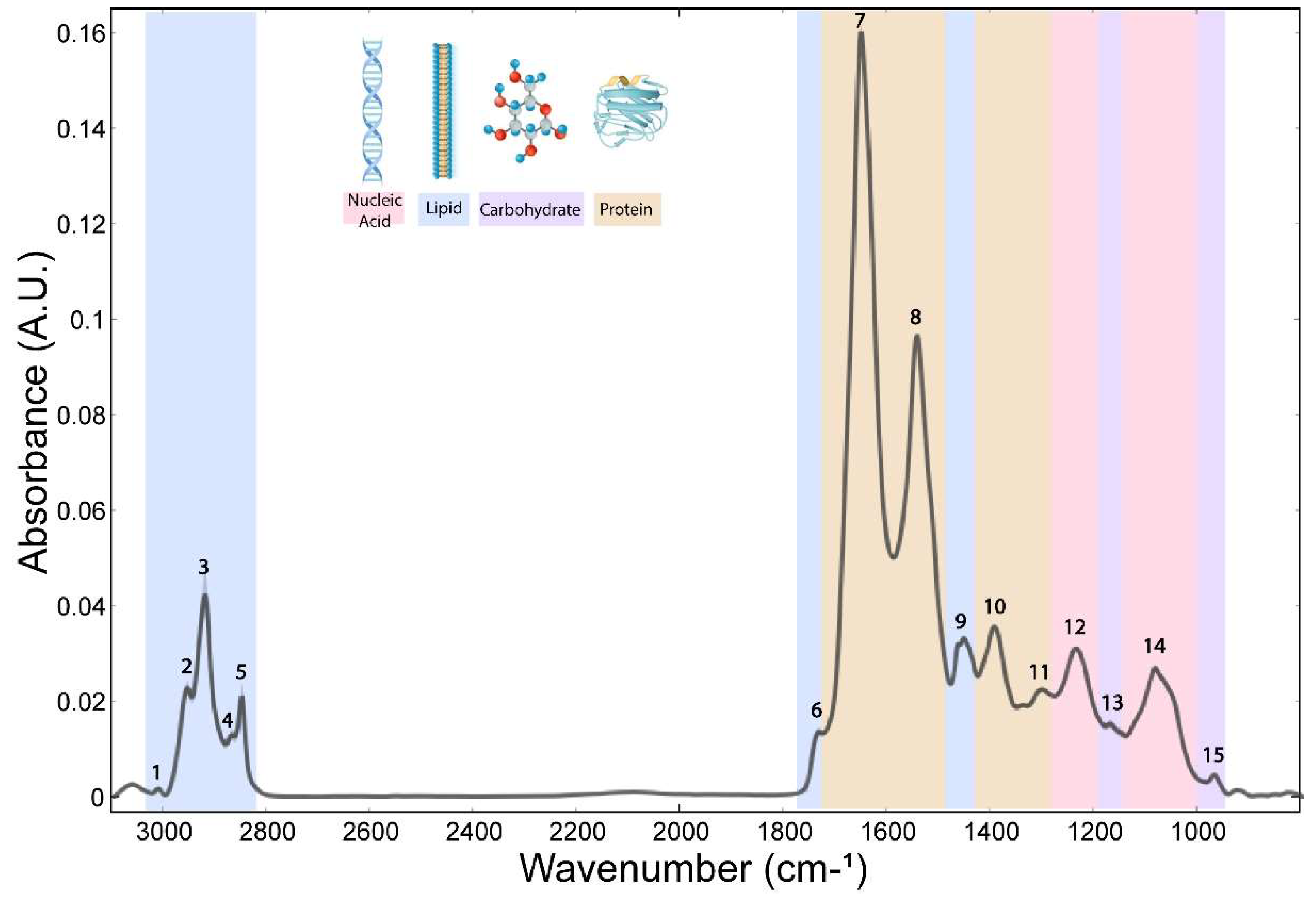

3.1. Correlation Analysis of FTIR Spectral Data Between Hippocampal Layers

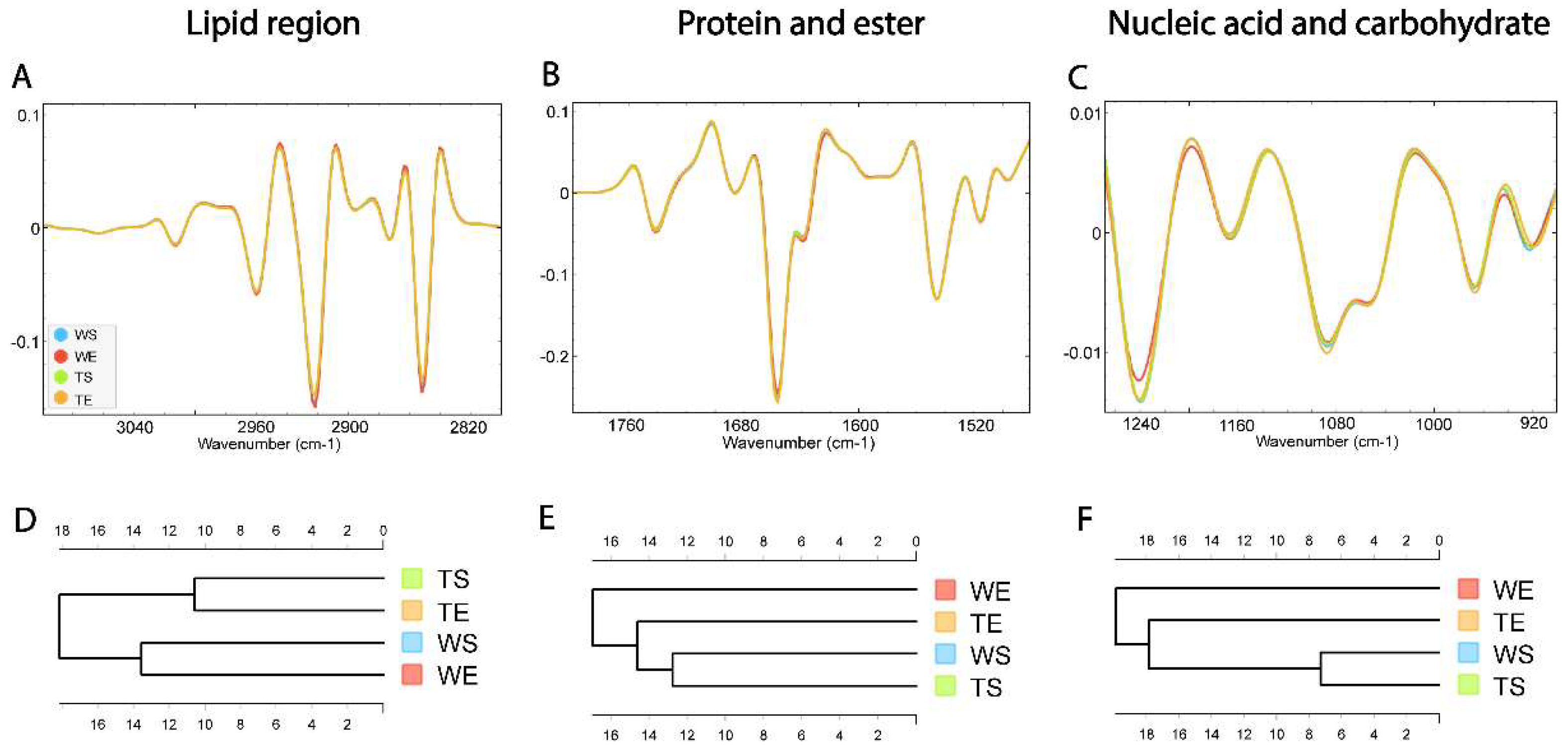

3.2. Similarity of Hippocampal Layers

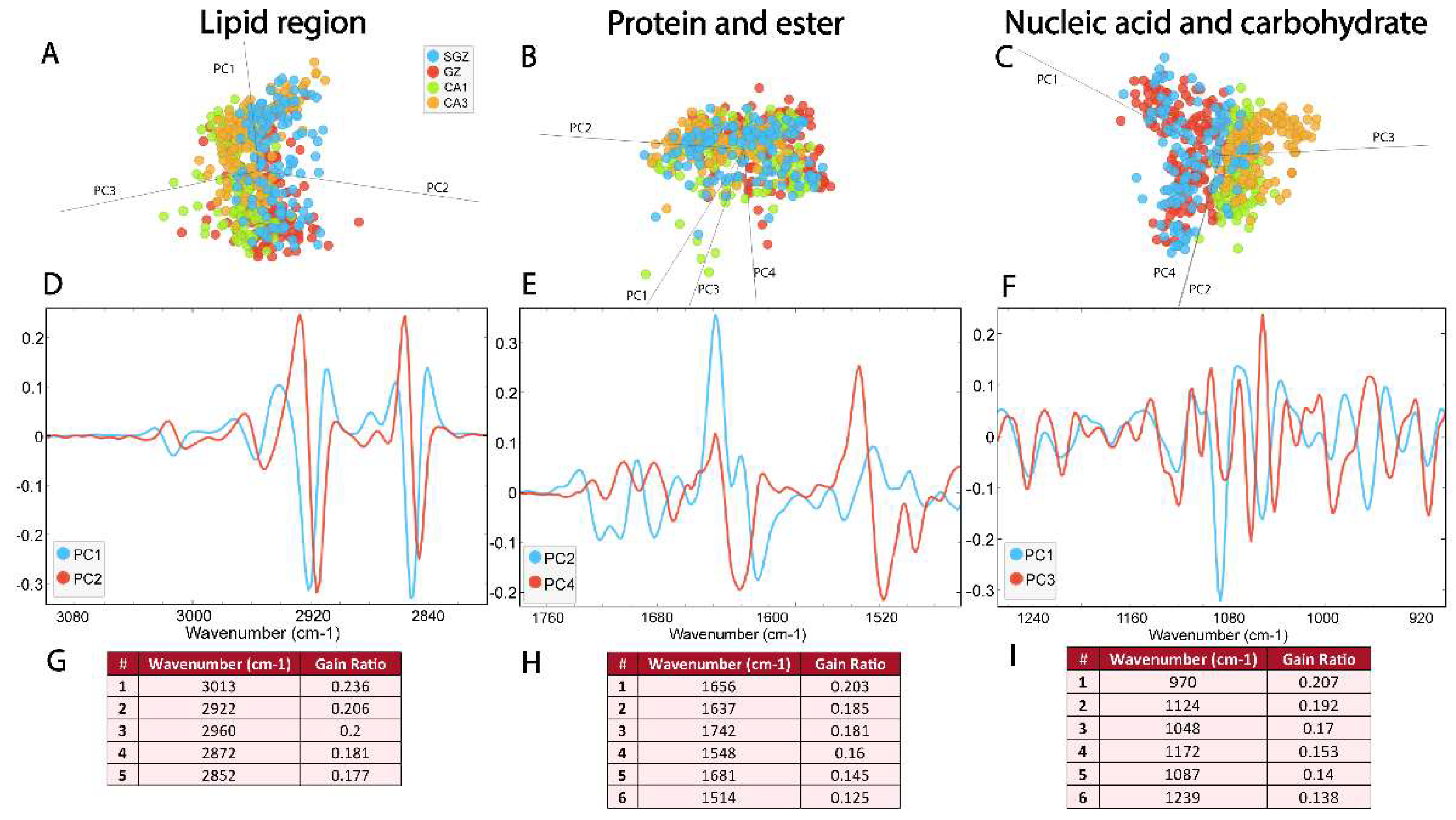

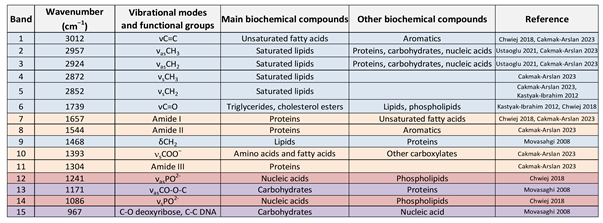

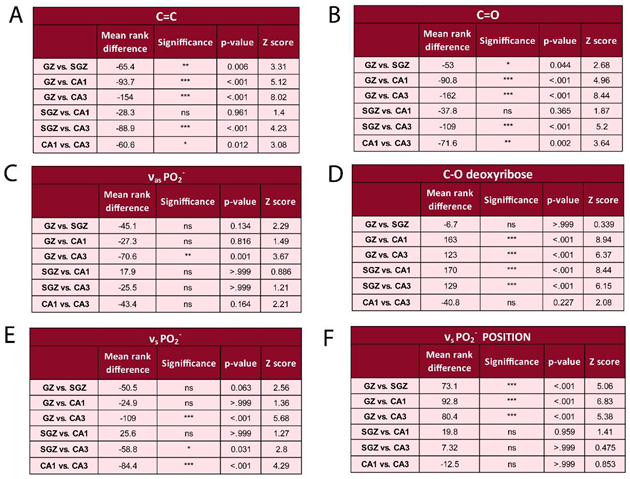

3.2. Biomolecular Characterization of Hippocampal Layers

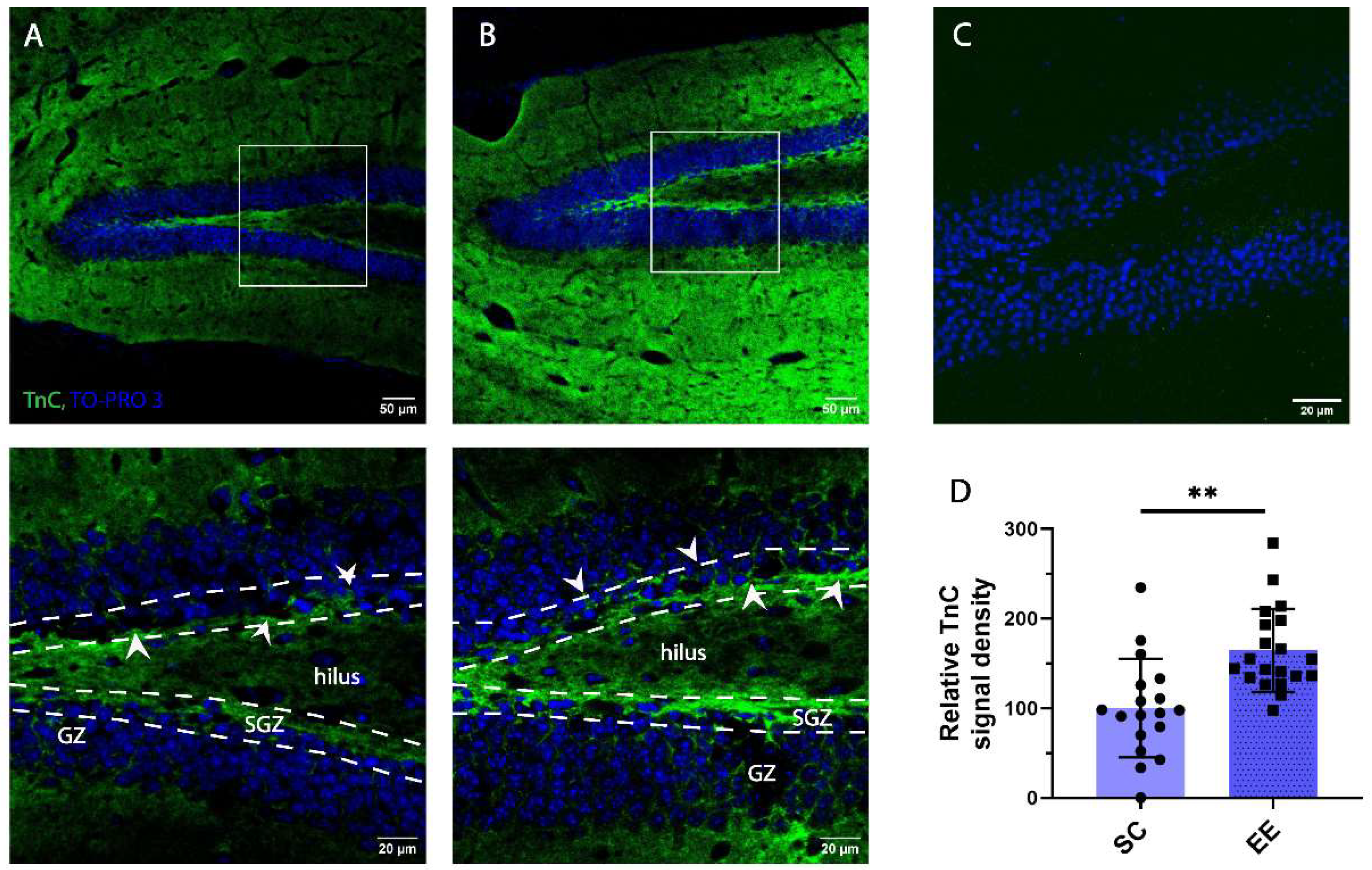

3.3. Expression of Tenascin C in Adult SGZ

3.4. Comparison of the Biomolecular Composition of the SGZ in Different Experimental Conditions

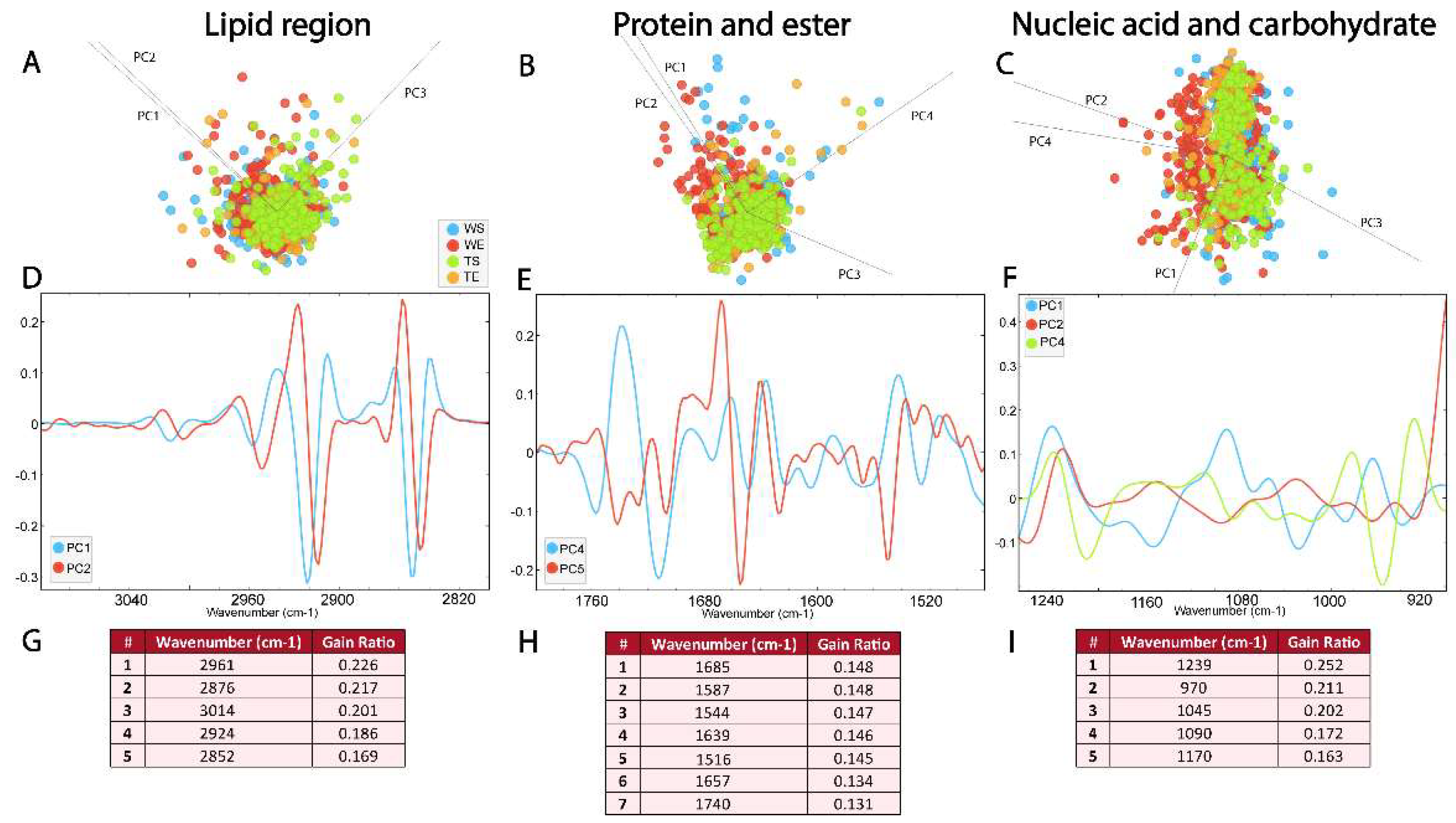

3.4. Biomolecular Profile of the SGZ Depends on the Environmental Conditions and Expression of TnC

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DG | Dentate gyrus |

| FTIR | Fourier transform infrared |

| SR | Synchrotron radiation |

| SGZ | Subgranular zone |

| TnC | Tenascin C |

| EE | Enriched environment |

| SC | Standard condition |

| GZ | Granular zone |

| TnC KO | Tenascin-C-deficient |

| HCA | Hierarchical cluster analysis |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| PC | Principal component |

| LDA | Linear discriminant analysis |

| RF | Random forest |

| WS | Wild type mice housed in standard conditions |

| WE | Wild type mice house in enriched environment |

| TS | TnC-deficient mice housed in standard conditions |

| TE | TnC-deficient mice housed in enriched environment |

References

- A Alkadhi, K. Cellular and Molecular Differences Between Area CA1 and the Dentate Gyrus of the Hippocampus. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019, 56, 6566–6580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hörtnagl, H.; Berger, M.; Sperk, G.; Pifl, C. Regional heterogeneity in the distribution of neurotransmitter markers in the rat hippocampus. Neuroscience 1991, 45, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, L.M.; Dumas, P. From structure to cellular mechanism with infrared microspectroscopy. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2010, 20, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J. Dudała, K. J. Dudała, K. Janeczko, Z. Setkowicz, D. Eichert, and J. Chwiej, “The use of SR-FTIR microspectroscopy for a preliminary biochemical study of the rat hippocampal formation tissue in case of pilocarpine induced epilepsy and neutroprotection with FK-506,” Nukleonika, vol. 57, no. 4, pp. 615–619, 2012.

- Ustaoglu, S.G.; Ali, M.H.M.; Rakib, F.; Blezer, E.L.A.; Van Heijningen, C.L.; Dijkhuizen, R.M.; Severcan, F. Biomolecular changes and subsequent time-dependent recovery in hippocampal tissue after experimental mild traumatic brain injury. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Praag, H.; Schinder, A.F.; Christie, B.R.; Toni, N.; Palmer, T.D.; Gage, F.H. Functional neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus. Nature 2002, 415, 1030–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjell, J.; Fischer-Sternjak, J.; Thompson, A.J.; Friess, C.; Sticco, M.J.; Salinas, F.; Cox, J.; Martinelli, D.C.; Ninkovic, J.; Franze, K.; et al. Defining the Adult Neural Stem Cell Niche Proteome Identifies Key Regulators of Adult Neurogenesis. Cell Stem Cell 2020, 26, 277–293.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucić, M.; Stamenković, V.; Andjus, P. The Extracellular Matrix Glycoprotein Tenascin C and Adult Neurogenesis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cope, E.C.; Gould, E. Adult Neurogenesis, Glia, and the Extracellular Matrix. 24. [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.; Cooper-Kuhn, C.M.; Kempermann, G.; Van Praag, H.; Winkler, J.; Gage, F.H.; Kuhn, H.G. Enriched environment and physical activity stimulate hippocampal but not olfactory bulb neurogenesis. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2003, 17, 2042–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Praag, H.; Shubert, T.; Zhao, C.; Gage, F.H. Exercise Enhances Learning and Hippocampal Neurogenesis in Aged Mice. J. Neurosci. 2005, 25, 8680–8685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzi, C.; Schnell, E.; Westbrook, G.L.; States, U. Localized hypoxia within the subgranular zone determines the early survival of newborn hippocampal granule cells. eLife 2015, 4, e08722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cembrowski, M.S.; Wang, L.; Sugino, K.; Shields, B.C.; Spruston, N.; States, U. Hipposeq: a comprehensive RNA-seq database of gene expression in hippocampal principal neurons. eLife 2016, 5, e14997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chwiej, J.G.; Ciesielka, S.W.; Skoczen, A.K.; Janeczko, K.J.; Sandt, C.; Planeta, K.L.; Setkowicz, Z.K. Biochemical Changes Indicate Developmental Stage in the Hippocampal Formation. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2018, 10, 628–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arellano, J.I.; Duque, A.; Rakic, P. A coming-of-age story: adult neurogenesis or adolescent neurogenesis in rodents? Front. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1383728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evers, M.R.; Salmen, B.; Bukalo, O.; Rollenhagen, A.; Bösl, M.R.; Morellini, F.; Bartsch, U.; Dityatev, A.; Schachner, M. Impairment of L-type Ca2+Channel-Dependent Forms of Hippocampal Synaptic Plasticity in Mice Deficient in the Extracellular Matrix Glycoprotein Tenascin-C. J. Neurosci. 2002, 22, 7177–7194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cancedda, L.; Putignano, E.; Sale, A.; Viegi, A.; Berardi, N.; Maffei, L. Acceleration of Visual System Development by Environmental Enrichment. J. Neurosci. 2004, 24, 4840–4848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Magalhães, C.R.; Carrilho, R.; Schrama, D.; Cerqueira, M.; da Costa, A.M.R.; Rodrigues, P.M. Mid-infrared spectroscopic screening of metabolic alterations in stress-exposed gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata). Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dučić, T.; Sanchez-Mata, A.; Castillo-Sanchez, J.; Algarra, M.; Gonzalez-Munoz, E. Monitoring oocyte-based human pluripotency acquisition using synchrotron-based FTIR microspectroscopy reveals specific biomolecular trajectories. Spectrochim. Acta Part A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2023, 297, 122713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crase, S.; Hall, B.; Thennadil, S.N. Cluster Analysis for IR and NIR Spectroscopy: Current Practices to Future Perspectives. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2021, 69, 1945–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, A.; Scroferneker, M.L.; de Souza, N.M.P.; de Moraes, P.C.; Pereira, B.A.S.; Cavalcante, R.d.S.; Mendes, R.P.; Corbellini, V.A. Rapid Classification of Serum from Patients with Paracoccidioidomycosis Using Infrared Spectroscopy, Univariate Statistics, and Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA). J. Fungi 2024, 10, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, S.O.M.; Saad, A.S.I.; Tadano, S.; Takeda, Y.; Konaka, T.; Yamasaki, Y.; Tahir, I.S.A.; Tsujimoto, H.; Akashi, K. Chemical Fingerprinting of Heat Stress Responses in the Leaves of Common Wheat by Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, D.C.; Pupin, B.; Borma, L.d.S. Influence of sample preparation methods on FTIR spectra for taxonomic identification of tropical trees in the Atlantic forest. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Holman, H.-Y.N.; Hao, Z.; Bechtel, H.A.; Martin, M.C.; Wu, C.; Chu, S. Synchrotron Infrared Measurements of Protein Phosphorylation in Living Single PC12 Cells during Neuronal Differentiation. Anal. Chem. 2012, 84, 4118–4125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toplak, M.; Read, S.T.; Sandt, C.; Borondics, F. Quasar: Easy Machine Learning for Biospectroscopy. Cells 2021, 10, 2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferhat, L.; Louis, N.C.A.; Jorquera, I.; Niquet, J.; Khrestchatisky, M.; Ben-Ari, Y.; Represa, A. Transient increase of tenascin-C in immature hippocampus: astroglial and neuronal expression. J. Neurocytol. 1996, 25, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cakmak-Arslan, G.; Kaya, Y.; Mamuk, S.; Akarsu, E.S.; Severcan, F. The investigation of the molecular changes duringlipopolysaccharide-induced systemic inflammation on rat hippocampus by usingFTIRspectroscopy. J. Biophotonics 2024, 17, e202300541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chwiej, J.; Dulinska, J.; Janeczko, K.; Dumas, P.; Eichert, D.; Dudala, J.; Setkowicz, Z. Synchrotron FTIR micro-spectroscopy study of the rat hippocampal formation after pilocarpine-evoked seizures. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 2010, 40, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andjus, P.; Stamenković, S.; Dučić, T. Synchrotron radiation-based FTIR spectro-microscopy of the brainstem of the hSOD1 G93A rat model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Eur. Biophys. J. 2019, 48, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNair, K.; Broad, J.; Riedel, G.; Davies, C.; Cobb, S. Global changes in the hippocampal proteome following exposure to an enriched environment. Neuroscience 2007, 145, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carulli, D.; Foscarin, S.; Rossi, F. Activity-Dependent Plasticity and Gene Expression Modifications in the Adult CNS. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2011, 4, 15205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakic, M.; Manahan-Vaughan, D.; Reymann, K.G.; Schachner, M. Long-term potentiationin vivo increases rat hippocampal tenascin-C expression. J. Neurobiol. 1998, 37, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Berg, D.A.; Zhu, Y.; Shin, J.Y.; Song, J.; Bonaguidi, M.A.; Enikolopov, G.; Nauen, D.W.; Christian, K.M.; Ming, G.-L.; et al. Single-Cell RNA-Seq with Waterfall Reveals Molecular Cascades underlying Adult Neurogenesis. Cell Stem Cell 2015, 17, 360–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamenkovic, V.; Stamenkovic, S.; Jaworski, T.; Gawlak, M.; Jovanovic, M.; Jakovcevski, I.; Wilczynski, G.M.; Kaczmarek, L.; Schachner, M.; Radenovic, L.; et al. The extracellular matrix glycoprotein tenascin-C and matrix metalloproteinases modify cerebellar structural plasticity by exposure to an enriched environment. Anat. Embryol. 2016, 222, 393–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Josifovska, N.; Andjelic, S.; Lytvynchuk, L.; Lumi, X.; Dučić, T.; Petrovski, G. Biomacromolecular Profile in Human Primary Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells—A Study of Oxidative Stress and Autophagy by Synchrotron-Based FTIR Microspectroscopy. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maffezzini, C.; Calvo-Garrido, J.; Wredenberg, A.; Freyer, C. Metabolic regulation of neurodifferentiation in the adult brain. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2020, 77, 2483–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).