Submitted:

18 February 2025

Posted:

18 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mice

2.2. Plasmids and siRNA

2.3. Superovulation and Granulosa Cell Cultures

2.3. Real-time Quantitative RT-PCR (qPCR) Analysis

2.4. In Situ Hybridization

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

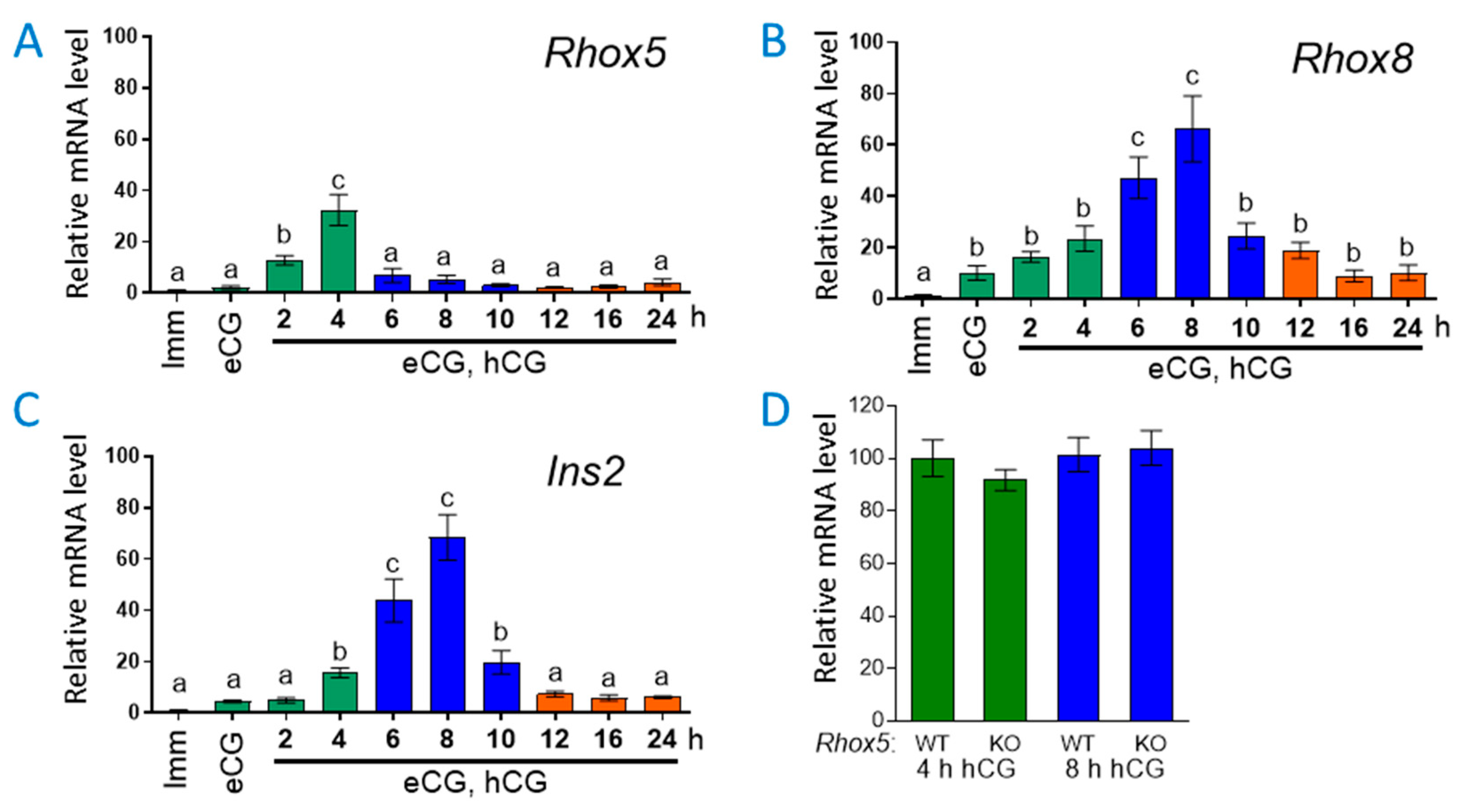

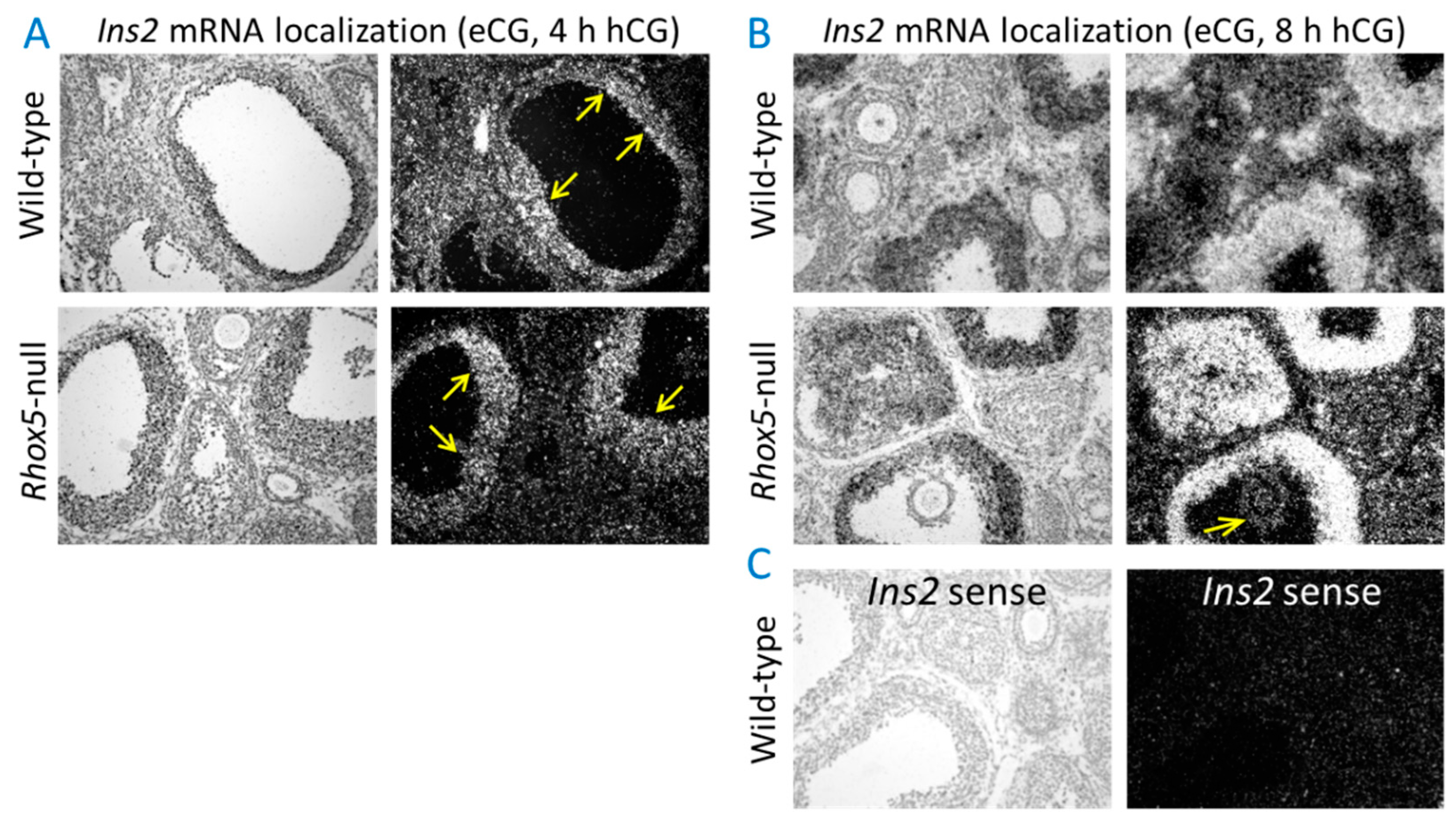

3.1. Ins2 Expression Tracks with Rhox8 Expression in the Ovary

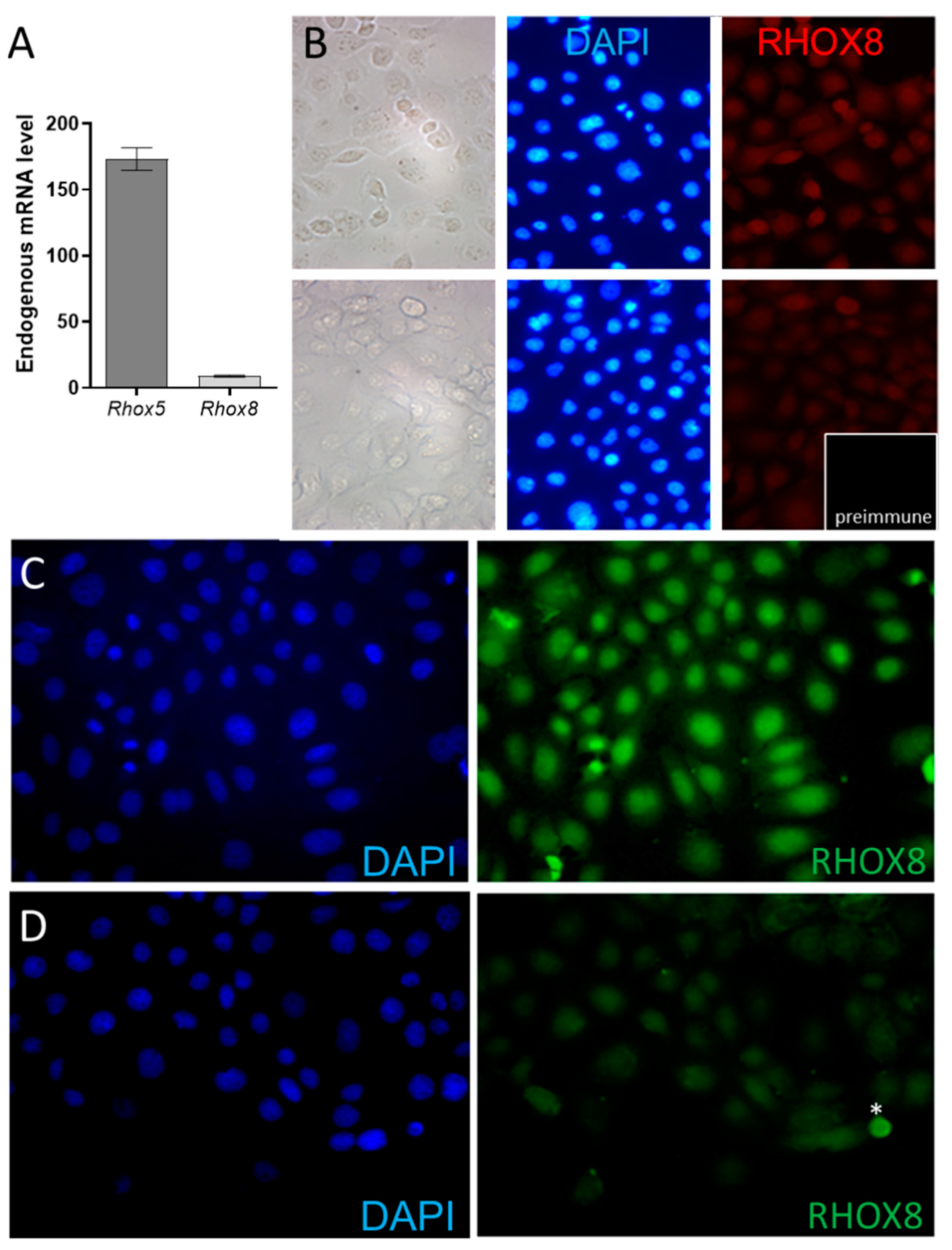

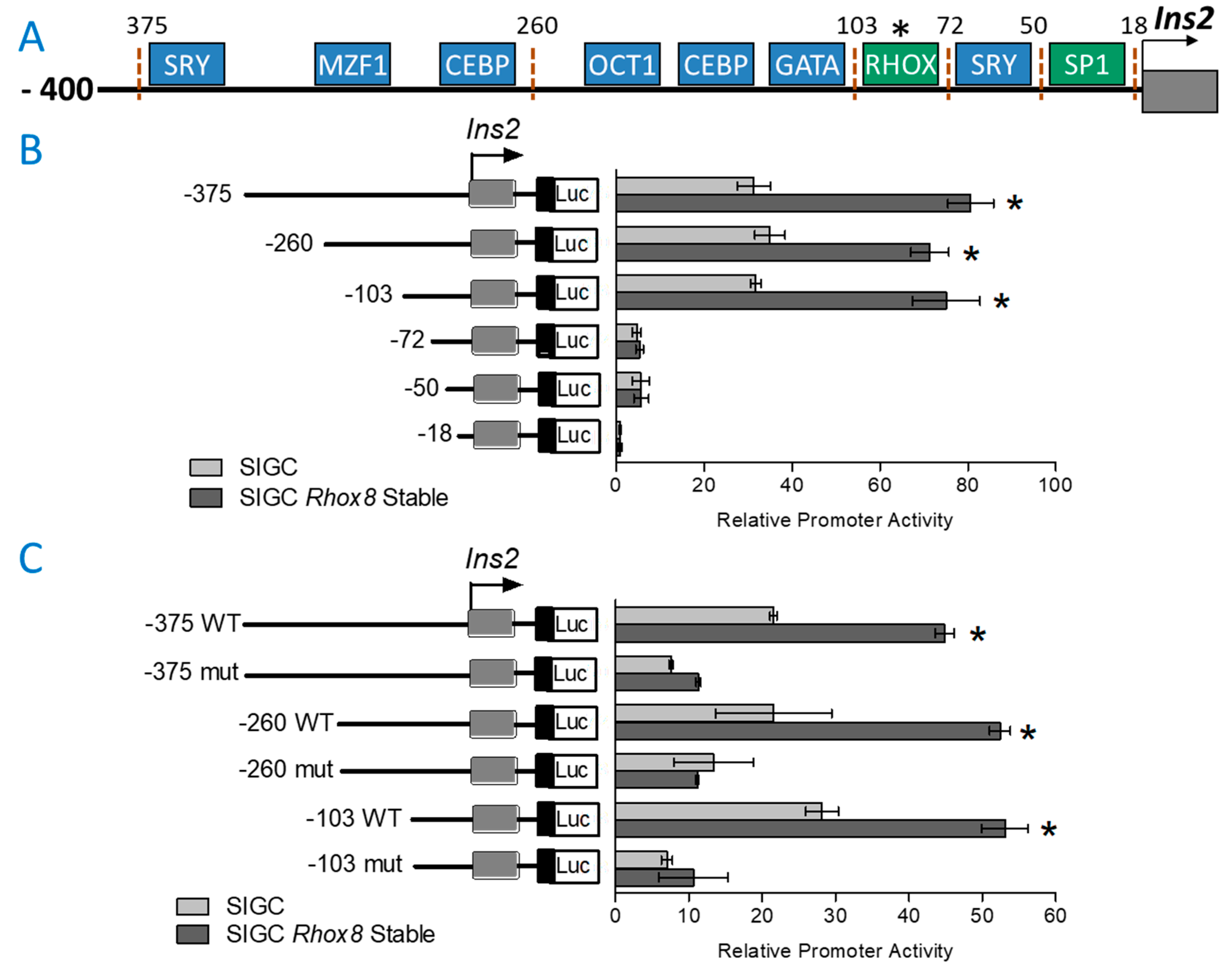

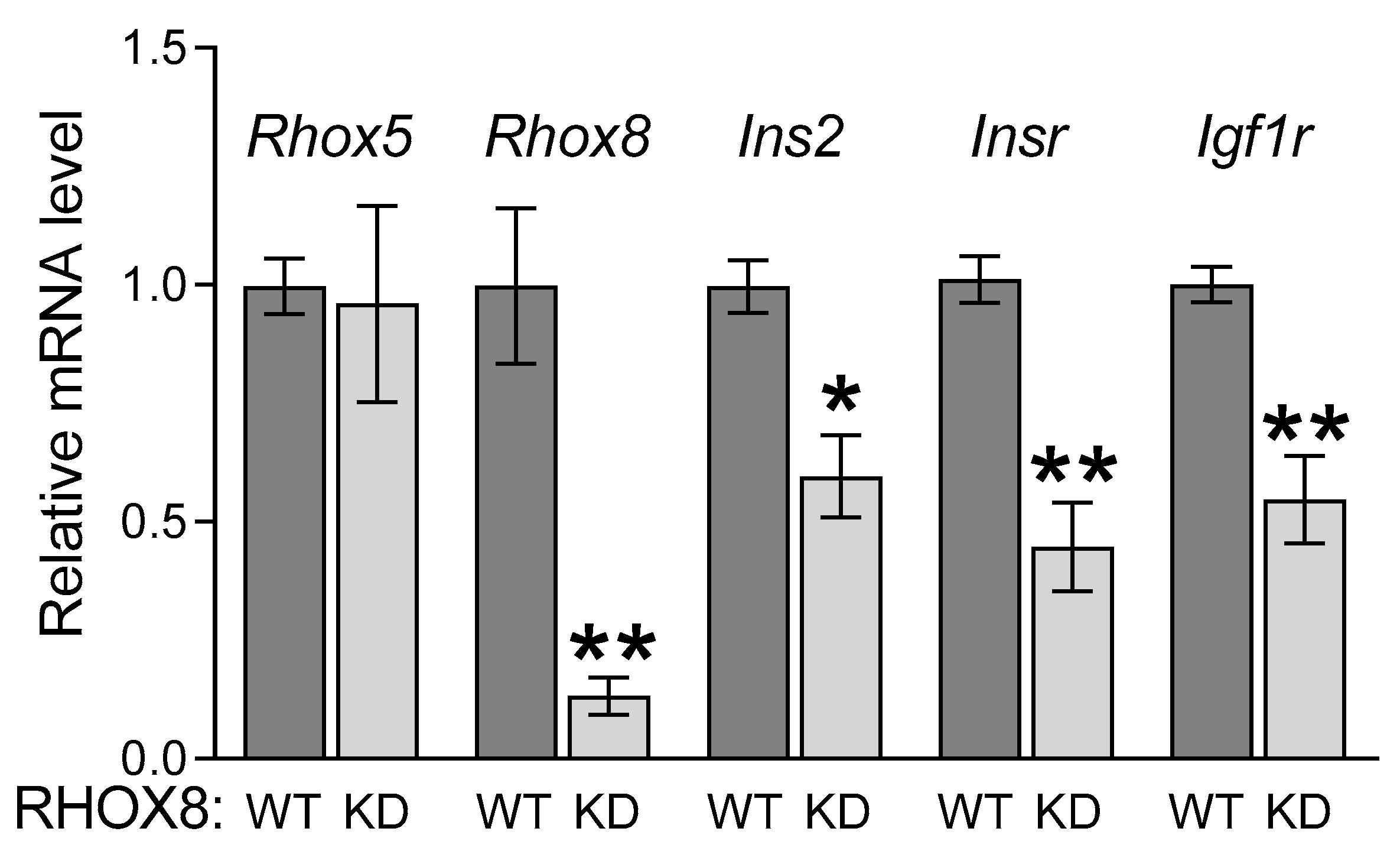

3.2. Regulation of Ins2 in Spontaneously Immortalized Rat Granulosa Cells (SIGC)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SIGC | Spontaneously Immortalized Granulosa Cells |

| PGR | Progesterone receptor |

| LH | Luteinizing hormone |

| qPCR | Quantitative real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction |

References

- Neirijnck, Y.; Papaioannou, M.D.; Nef, S. The Insulin/IGF System in Mammalian Sexual Development and Reproduction. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentworth, B.M.; Schaefer, I.M.; Villa-Komaroff, L.; Chirgwin, J.M. Characterization of the two nonallelic genes encoding mouse preproinsulin. Journal of molecular evolution 1986, 23, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, J.I.; Clemmons, D.R. Insulin-like growth factors and their binding proteins: biological actions. Endocrine reviews 1995, 16, 3–34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bengtsson, M.; Stahlberg, A.; Rorsman, P.; Kubista, M. Gene expression profiling in single cells from the pancreatic islets of Langerhans reveals lognormal distribution of mRNA levels. Genome research 2005, 15, 1388–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deltour, L.; Leduque, P.; Blume, N.; Madsen, O.; Dubois, P.; Jami, J.; Bucchini, D. Differential expression of the two nonallelic proinsulin genes in the developing mouse embryo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1993, 90, 527–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, V.L.; Moore, N.C.; Parnell, S.M.; Mason, D.W. Intrathymic expression of genes involved in organ specific autoimmune disease. J Autoimmun 1998, 11, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLean, J.A., 2nd; Hu, Z.; Welborn, J.P.; Song, H.W.; Rao, M.K.; Wayne, C.M.; Wilkinson, M.F. The RHOX homeodomain proteins regulate the expression of insulin and other metabolic regulators in the testis. The Journal of biological chemistry 2013, 288, 34809–34825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoeller, E.L.; Albanna, G.; Frolova, A.I.; Moley, K.H. Insulin rescues impaired spermatogenesis via the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis in Akita diabetic mice and restores male fertility. Diabetes 2012, 61, 1869–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izumi, T.; Yokota-Hashimoto, H.; Zhao, S.; Wang, J.; Halban, P.A.; Takeuchi, T. Dominant negative pathogenesis by mutant proinsulin in the Akita diabetic mouse. Diabetes 2003, 52, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.S.; Dale, A.N.; Moley, K.H. Maternal diabetes adversely affects preovulatory oocyte maturation, development, and granulosa cell apoptosis. Endocrinology 2005, 146, 2445–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Moley, K.H. Maternal diabetes and oocyte quality. Mitochondrion 2010, 10, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, M.; Brannstrom, M.; Akins, J.W.; Curry, T.E., Jr. New insights into the ovulatory process in the human ovary. Human reproduction update 2025, 31, 21–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, T.R. Rerouting of follicle-stimulating hormone secretion and gonadal function. Fertil Steril 2023, 119, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ackert, C.L.; Gittens, J.E.; O'Brien, M.J.; Eppig, J.J.; Kidder, G.M. Intercellular communication via connexin43 gap junctions is required for ovarian folliculogenesis in the mouse. Developmental biology 2001, 233, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, R.J.; Cook-Andersen, H. Disordered follicle development. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2013, 373, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangas, S.A.; Choi, Y.; Ballow, D.J.; Zhao, Y.; Westphal, H.; Matzuk, M.M.; Rajkovic, A. Oogenesis requires germ cell-specific transcriptional regulators Sohlh1 and Lhx8. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2006, 103, 8090–8095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Choi, Y.; Zhao, H.; Simpson, J.L.; Chen, Z.J.; Rajkovic, A. NOBOX homeobox mutation causes premature ovarian failure. Am J Hum Genet 2007, 81, 576–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkovic, A.; Pangas, S.A.; Ballow, D.; Suzumori, N.; Matzuk, M.M. NOBOX deficiency disrupts early folliculogenesis and oocyte-specific gene expression. Science 2004, 305, 1157–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, J.S.; Gao, L. Irx3 is differentially up-regulated in female gonads during sex determination. Gene Expr Patterns 2005, 5, 756–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkovic, A.; Yan, C.; Yan, W.; Klysik, M.; Matzuk, M.M. Obox, a family of homeobox genes preferentially expressed in germ cells. Genomics 2002, 79, 711–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.S.; Kim, E.Y.; Kim, K.H.; Moon, J.; Park, K.S.; Kim, K.S.; Lee, K.A. Obox4 critically regulates cAMP-dependent meiotic arrest and MI-MII transition in oocytes. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology 2010, 24, 2314–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.S.; Kim, K.H.; Kim, E.Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Ko, J.J.; Lee, K.A. Obox4-silencing activated STAT3 and MPF/MAPK signaling accelerate GVBD in mouse oocytes. Reproduction 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacLean, J.A. , 2nd. The role of Rhox homeobox factors in tumorigenesis. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2013, 18, 474–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLean, J.A., 2nd; Wilkinson, M.F. The Rhox genes. Reproduction 2010, 140, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilming, L.G.; Boychenko, V.; Harrow, J.L. Comprehensive comparative homeobox gene annotation in human and mouse. Database (Oxford) 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne, C.M.; MacLean, J.A.; Cornwall, G.; Wilkinson, M.F. Two novel human X-linked homeobox genes, hPEPP1 and hPEPP2, selectively expressed in the testis. Gene 2002, 301, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, R.M.; Davis, M.G.; Hayashi, K.; MacLean, J.A. Regulated expression of Rhox8 in the mouse ovary: evidence for the role of progesterone and RHOX5 in granulosa cells. Biology of reproduction 2013, 88, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daggag, H.; Svingen, T.; Western, P.S.; van den Bergen, J.A.; McClive, P.J.; Harley, V.R.; Koopman, P.; Sinclair, A.H. The rhox homeobox gene family shows sexually dimorphic and dynamic expression during mouse embryonic gonad development. Biology of reproduction 2008, 79, 468–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLean, J.A., 2nd; Rao, M.K.; Doyle, K.M.; Richards, J.S.; Wilkinson, M.F. Regulation of the Rhox5 homeobox gene in primary granulosa cells: preovulatory expression and dependence on SP1/SP3 and GABP. Biology of reproduction 2005, 73, 1126–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welborn, J.P.; Davis, M.G.; Ebers, S.D.; Stodden, G.R.; Hayashi, K.; Cheatwood, J.L.; Rao, M.K.; MacLean, J.A. , 2nd. Rhox8 Ablation in the Sertoli Cells Using a Tissue-Specific RNAi Approach Results in Impaired Male Fertility in Mice. Biology of reproduction 2015, 93, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maclean, J.A., 2nd; Chen, M.A.; Wayne, C.M.; Bruce, S.R.; Rao, M.; Meistrich, M.L.; Macleod, C.; Wilkinson, M.F. Rhox: a new homeobox gene cluster. Cell 2005, 120, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, Y.; Kasu, M.; Bottoms, C.J.; Douglas, J.C.; Sekulovski, N.; Hayashi, K.; MacLean Ii, J.A. Rhox8 homeobox gene ablation leads to rete testis abnormality and male subfertility in micedagger. Biology of reproduction 2023, 109, 520–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacLean, J.A., 2nd; Hayashi, K.; Turner, T.T.; Wilkinson, M.F. The Rhox5 homeobox gene regulates the region-specific expression of its paralogs in the rodent epididymis. Biology of reproduction 2012, 86, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitman, J.L.; Lin, T.P.; Kleeman, J.E.; Erickson, G.F.; MacLeod, C.L. Normal reproductive and macrophage function in Pem homeobox gene-deficient mice. Developmental biology 1998, 202, 196–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleenor, D.E.; Freemark, M. Prolactin induction of insulin gene transcription: roles of glucose and signal transducer and activator of transcription 5. Endocrinology 2001, 142, 2805–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekulovski, N.; Whorton, A.E.; Shi, M.; Hayashi, K.; MacLean, J.A. , 2nd. Periovulatory insulin signaling is essential for ovulation, granulosa cell differentiation, and female fertility. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology 2020, 34, 2376–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, L.S.; Stoica, G.; Tilley, R.; Burghardt, R.C. Rat ovarian granulosa cell culture: a model system for the study of cell-cell communication during multistep transformation. Cancer research 1991, 51, 696–706. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi, K.; Yoshioka, S.; Reardon, S.N.; Rucker, E.B., 3rd; Spencer, T.E.; DeMayo, F.J.; Lydon, J.P.; MacLean, J.A. , 2nd. WNTs in the neonatal mouse uterus: potential regulation of endometrial gland development. Biology of reproduction 2011, 84, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, L.S.; Stein, D.W.; Echols, J.; Burghardt, R.C. Concomitant alterations of desmosomes, adhesiveness, and diffusion through gap junction channels in a rat ovarian transformation model system. Exp Cell Res 1993, 207, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Yaba, A.; Kasiman, C.; Thomson, T.; Johnson, J. mTOR controls ovarian follicle growth by regulating granulosa cell proliferation. PloS one 2011, 6, e21415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Fang, F.; Liou, Y.C.; Ng, H.H. Zfp143 regulates Nanog through modulation of Oct4 binding. Stem cells (Dayton, Ohio) 2008, 26, 2759–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlaeminck-Guillem, V.; Vanacker, J.M.; Verger, A.; Tomavo, N.; Stehelin, D.; Laudet, V.; Duterque-Coquillaud, M. Mutual repression of transcriptional activation between the ETS-related factor ERG and estrogen receptor. Oncogene 2003, 22, 8072–8084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hippenmeyer, S.; Youn, Y.H.; Moon, H.M.; Miyamichi, K.; Zong, H.; Wynshaw-Boris, A.; Luo, L. Genetic mosaic dissection of Lis1 and Ndel1 in neuronal migration. Neuron 2010, 68, 695–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tasic, B.; Hippenmeyer, S.; Wang, C.; Gamboa, M.; Zong, H.; Chen-Tsai, Y.; Luo, L. Site-specific integrase-mediated transgenesis in mice via pronuclear injection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2011, 108, 7902–7907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla, V.; Coumoul, X.; Deng, C.X. RNAi-based conditional gene knockdown in mice using a U6 promoter driven vector. International journal of biological sciences 2007, 3, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, V.; Coumoul, X.; Wang, R.H.; Kim, H.S.; Deng, C.X. RNA interference and inhibition of MEK-ERK signaling prevent abnormal skeletal phenotypes in a mouse model of craniosynostosis. Nat Genet 2007, 39, 1145–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamin, S.P.; Arango, N.A.; Mishina, Y.; Hanks, M.C.; Behringer, R.R. Genetic studies of the AMH/MIS signaling pathway for Mullerian duct regression. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2003, 211, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, J.C.; Sekulovski, N.; Arreola, M.R.; Oh, Y.; Hayashi, K.; MacLean, J.A. , 2nd. Normal Ovarian Function in Subfertile Mouse with Amhr2-Cre-Driven Ablation of Insr and Igf1r. Genes (Basel) 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Beulze, M.; Daubech, C.; Balde-Camara, A.; Ghieh, F.; Vialard, F. Mammal Reproductive Homeobox (Rhox) Genes: An Update of Their Involvement in Reproduction and Development. Genes (Basel) 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.T.; Moley, K.H. Paternal effect on embryo quality in diabetic mice is related to poor sperm quality and associated with decreased glucose transporter expression. Reproduction 2008, 136, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, H.C.; Kim, S.Y.; Cho, G.J.; Woodruff, T.K. Poorly-Controlled Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus Impairs LH-LHCGR Signaling in the Ovaries and Decreases Female Fertility in Mice. Yonsei Med J 2019, 60, 667–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandi, A.; Wang, X.; Accili, D.; Wolgemuth, D.J. The effect of insulin signaling on female reproductive function independent of adiposity and hyperglycemia. Endocrinology 2010, 151, 1863–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekulovski, N.; Whorton, A.E.; Shi, M.; Hayashi, K.; MacLean, J.A. , 2nd. Insulin signaling is an essential regulator of endometrial proliferation and implantation in mice. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology 2021, 35, e21440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).