Introduction

Many human research papers focused on extending life. To achieve this goal, many studies have been conducted on different modalities, such as supplements, including curcumin, resveratrol, and sulforaphane. Other phytochemical substances include moringa and Rhodiola. Drugs such as metformin have been shown to have anti-aging efficacy. Other modalities include intermittent fasting, exercise, and diet restriction. All these measures exerted biphasic effects where low doses had a mechanism different from that of higher doses. Different models, such as yeast and nematodes (Caenorhabditis elegans), have been tested for their ability to prolong life spans. Other representations were fish and rodents. Multiple human factors play important roles in human aging, including genetic disorders, environmental factors, lifestyle factors, and social factors. Many plant derivatives have been shown to induce longevity, creating a chemical library of anti-aging remedies. (Agathokleous, Kitao et al. 2020, Calabrese, Nascarella et al. 2024).

Human biological, physiological, and behavioral processes, including gene expression and DNA repair, are affected by the biological clock. It has been proposed that an impaired biological clock is a risk factor for tumorigenesis. Unfortunately, clock-related therapy did not succeed. Further research is needed to decipher carcinogenesis (Sancar and Van Gelder 2021).

The questions in this review are as follows: does the biological clock control gene expression, or does gene expression control the biological clock? DNA methylation has been proposed to be a biological clock parameter. DNA methylation was used as an indicator of age accurately. DNA methylation is termed the epigenetic clock. This clock depends on the DNA thread as a regulator of the biological clock. In this article, it is suggested that RNA transcription is a universal biological clock and is responsible for why all creatures age (Horvath and Raj 2018).

RNA polymerase inhibitors were developed to treat RNA viruses. These drugs inhibit the transcription machinery and have highly conserved targets in many viruses in humans. These groups of drugs, such as remdesivir, favipiravir, sofosbuvir, zidovudine, and ribavirin, have been approved to treat SARS-CoV-2, influenza, hepatitis C, and HIV, respectively. (Lu, Su et al. 2021).

Sofosbuvir is a potent oral RNA polymerase inhibitor that effectively eradicates hepatitis C. This drug is relatively new and has been used since 2013. It is available as a tablet of 400 mg per day. It is taken in combination with other drugs such as ribavirin at a 1000 mg dose. The combination was applied daily for 12 weeks. A new combination of sofosbuvir with other drugs, such as Harvoni, has been applied to treat HCV for 8 weeks. Other drugs, such as peginterferon, simeprevir, daclatasvir, or ledipasvir, have been added to sofosbuvir to overcome HCV. (2012).

Rifampicin is a well-known wide-range antibiotic used to treat tuberculosis. Its main mechanism of action is an inhibitor of the bacterial RNA polymerase. Its target is the crystal structure of the Thermus aquaticus core RNA polymerase. The inhibition of the transcription process is considered the mechanism of the bactericidal effect (Campbell, Korzheva et al. 2001).

Eukaryotic RNA Polymerases

The eukaryotic nucleus is the site of 3 RNA polymerases (Biswas, Ganguly et al. 1975, Blair 1988). RNA polymerase I (Pol I), RNA polymerase II (Pol II), and RNA polymerase III (Pol III) have different subunit compositions with specific biochemical functions; all of them are the main components of the transcription machinery, but they are different in the groups of genes they transcribe. RNA polymerases are available in all living organisms, from viruses to humans (Werner and Grohmann 2011). Pol I transcribes ribosomal RNA, and Pol II is responsible for messenger RNA generation in addition to long noncoding RNAs. Pol III transcribes microRNA (Kulaberoglu, Malik et al. 2021). Both Pol I and Pol III transcribe a few genes, and they produce the most abundant amount of RNA (White, Gottlieb et al. 1995, Scott, Cairns et al. 2001).

Specific rDNA repeats are considered templates for Pol I to catalyze the manufacture of rRNA. To achieve this machinery precisely with an efficient output, several accessory factors are required to enable polymerase recruitment, initiation, promoter escape, elongation, termination, and reinitiation. This complex process occurs in the subnuclear zone (Goodfellow and Zomerdijk 2013).

Pol II is a Multi-subunit protein responsible for the transcription of all protein-coding genes in eukaryotes. The largest subunit of Pol II consists of seven component (heptad) repeats, which are located in the carboxyl-terminal domain (CTD). The CTD cooperates with many general and specific transcription factors, regulators, and other domains to initiate and control transcription. Across eukaryotes, the number of repeats and the structure of these domains or subunits are conserved across different species (Venkat Ramani, Yang et al. 2021).

Pol III is responsible for the transcription of highly abundant, stable small RNAs that play crucial functional regulatory functions, chiefly in the protein synthesis machinery. The expression of these genes is associated with high energy consumption and subsequently changes the need for protein synthesis during cell growth and proliferation (Turowski and Tollervey 2016).

Double Effects of Sofosbuvir on the Liver

Sofosbuvir, a powerful viral anti-hepatitis C drug, has been applied experimentally to rat cell lines. The toxic concentrations ranged from 25 to 50 to 100 µM. A lower potential toxic dose was associated with a classic oxidative stress burden with mitochondrial injury. However, a mega concentration of 400 µM has been shown to have antioxidant and protective effects (Yousefsani, Nabavi et al. 2020). In this important study, relatively low doses of the toxic agent sofosbuvir had dual effects. The drug could intoxicate the mitochondria in the presence of oxidative stress. However, at high doses, the drug loses its selectivity and inhibits rat liver RNA polymerases in my opinion. As a result, the transcription machinery is interrupted or at least the speed of the transcription is delayed, leading to the possible longevity effect on the rat liver. The faster the transcription machinery works, the faster the rate of aging develops. Further research is required to test this hypothesis. The aging process is an end product of basic biological activity. Recent reports from 2020 revealed an increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma after the use of direct-acting drugs, such as sofosbuvir, in decompensated hepatic patients. Other reports. Recent research has suggested that advanced cirrhotic patients do not benefit much from direct-acting drugs, and this is a major concern about hepatocellular carcinoma, especially after 2020 (Delgado Martinez, Gomez-Rubio et al. 2021, Lee, Chen et al. 2022, Santana-Salgado, Bautista-Santos et al. 2022, Sapena, Enea et al. 2022, Abdelhamed and El-Kassas 2023). It is too optimistic to prove the safety of direct-acting drugs after many years of follow-up.

Effects of Rifampicin on Longevity in a Worm Model

Rifampicin has been tested as a longevity drug against degenerative disorders, such as aging, in C. elegans. Experimentally, the addition of rifampicin to C. elegans increased the C. elegans life span and decreased protein glycation. Other versions of the rifampicin-like chemical exhibited a long C. elegans life span. However, this process results in less protein glycation. Rifampicin is thought to act on PTEN, JNK.1, and DAF-16.(Golegaonkar, Tabrez et al. 2015) Rifampicin has been suggested to function as an mTOR inhibitor, along with sirolimus, which is another derivative that works as a rifampicin-like drug. Both structures were effective in prolonging the life span of rats, worms, and yeast. They were proven for human applications. These compounds have been suggested to be promising candidates for treating aging-related disorders (Blagosklonny 2006, Blagosklonny 2007). The toxicity of rifampicin includes hepatotoxicity and increased free radical release. (Shen, Cheng et al. 2009). These findings are not contradictory to the antiaging effects of these agents. It was proposed that mitochondrial injury plays a role in the toxicology results.

Allicin Longevity Effects

Allicin is extracted from garlic. It has been demonstrated to have antioxidant properties. In addition, it demonstrated longevity effects in experimental work performed in vitro. In a study on animal oocytes and embryos, the addition of allicin improved survival and modulated autophagy in addition to exerting antioxidant effects (Park, Lee et al. 2019). Similar in vitro results were recorded in human umbilical endothelial cells, as allicin showed marked antioxidant effects. These anti-aging effects are mediated by the Sirt-1 enzyme (Lin, Liu et al. 2017). Allicin has other non-redox effects, such as the modulation of inflammatory and longevity mechanisms (Augusti, Jose et al. 2012). The antimicrobial and possibly longevity effects could be mediated by anti-protein manufacturing through the inhibition of RNA polymerases (Feldberg, Chang et al. 1988).

Ribavirin and Longevity

Ribavirin works as an antiviral RNA polymerase inhibitor (Celik, Erol et al. 2022). It has been suggested that ribavirin has an antiaging mechanism, as demonstrated experimentally in Caenorhabditis elegans (

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/neuroscience/caenorhabditis-elegans). The drug increases the life span of worms, similar to other RNA polymerase inhibitors. The antiviral medication inhibits the target of the rapamycin (mTOR) pathway and stimulates the AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathway. Furthermore, it reduces the levels of ATP, which promotes antiaging functions (Li, Xie et al. 2023).

Favipiravir and Longevity

The most recent antiviral versions, such as favipiravir, have not been tested widely. Its toxicity induces oxidative stress. The high doses induced hepatorenal injury. This injury could be due to mitochondrial injury resulting from mitochondrial RNA polymerase inhibition. Supplementation with vitamin C improved the toxicity profile. We are not sure whether all anti-RNA polymerases have the same toxicity profile, yet it seems that RNA polymerases are conserved across different species (Gunaydin-Akyildiz, Aksoy et al. 2022, Dogan, Kaya et al. 2023).

Other RNA Polymerase Inhibitors and Longevity

Other agents function as RNA polymerase inhibitors, such as remdesivir, sandacrabins, and ripostatins. These medications have been shown to inhibit RNA polymerase activity in microorganisms. However, it is not known whether these agents, at higher doses, affect human RNA polymerases (Irschik, Augustiniak et al. 1995, Tang, Liu et al. 2014, Bader, Panter et al. 2022). It is not known what the full mechanisms of these drugs are. We suggest conducting both in vivo and in vitro studies on the aging or antiaging properties of these inhibitors.

Table 1.

shows the most common RNA polymerase inhibitors and studies tracking their mechanisms and possible longevity roles.

Table 1.

shows the most common RNA polymerase inhibitors and studies tracking their mechanisms and possible longevity roles.

| The drug |

The target |

Effect |

Mechanism |

| Sofosbuvir |

HCV |

May Increase the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma In vitro (Tsai, Cheng et al. 2022). |

PHOSPHO2, KLHL23, TRIM39, TSNAX-DISC1, and RPP21 gene expression (Tsai, Cheng et al. 2022). |

| Ribavirin |

HCV |

Anemia if used in combination (Krishnan and Dixit 2011). |

Decrease liver inflammation and induce RBCs hemolysis (Soota and Maliakkal 2014). |

| Remdesivir |

COVID-19 |

Decrease inflammation (Kandhaya-Pillai, Yang et al. 2022) |

JAC/STAT1 pathway (Kandhaya-Pillai, Yang et al. 2022) |

| zidovudine |

HIV |

Prolog life span and antiaging (McIntyre, Molenaars et al. 2023) |

Inhibit mTOR and activate the AMPK pathway. other mechanisms (Thanapairoje, Junsiritrakhoon et al. 2023) |

| Favipiravir |

Anti -influenzas |

No experiments on longevity |

Not confirmed |

| Rifampicin |

Mycobacteria (antibiotic). |

Promote longevity and inhibit oxidative stress (Lee, Baek et al. 2020). |

Increase IGF-1 and SERB lipid signaling (Admasu, Chaithanya Batchu et al. 2018). |

Transcription Machinery and Aging

It is thought that high doses of medications, such as sofosbuvir, ribavirin, and other RNA polymerase inhibitors, promote longevity, and we think that the effects of the metabolic profile are a second messenger of what we call the transcription clock. It is an enormous dream to live for a longer life span. However, transcription is a fundamental process that pushes living organisms toward aging. Indeed, it is possible to improve quality of life rather than hinder aging. Aging is an active process, and it is part of nature. However, it is possible to live with the best health status. DNA methylation is a strong marker of aging. It is considered an epigenetic control of transcription. (Levine, Lu et al. 2018). The possibility for a new theory is that the process of transcription itself acts as a biological clock. We believe that combining DNA and transcription machinery could be the best biological clock for controlling various biological processes.

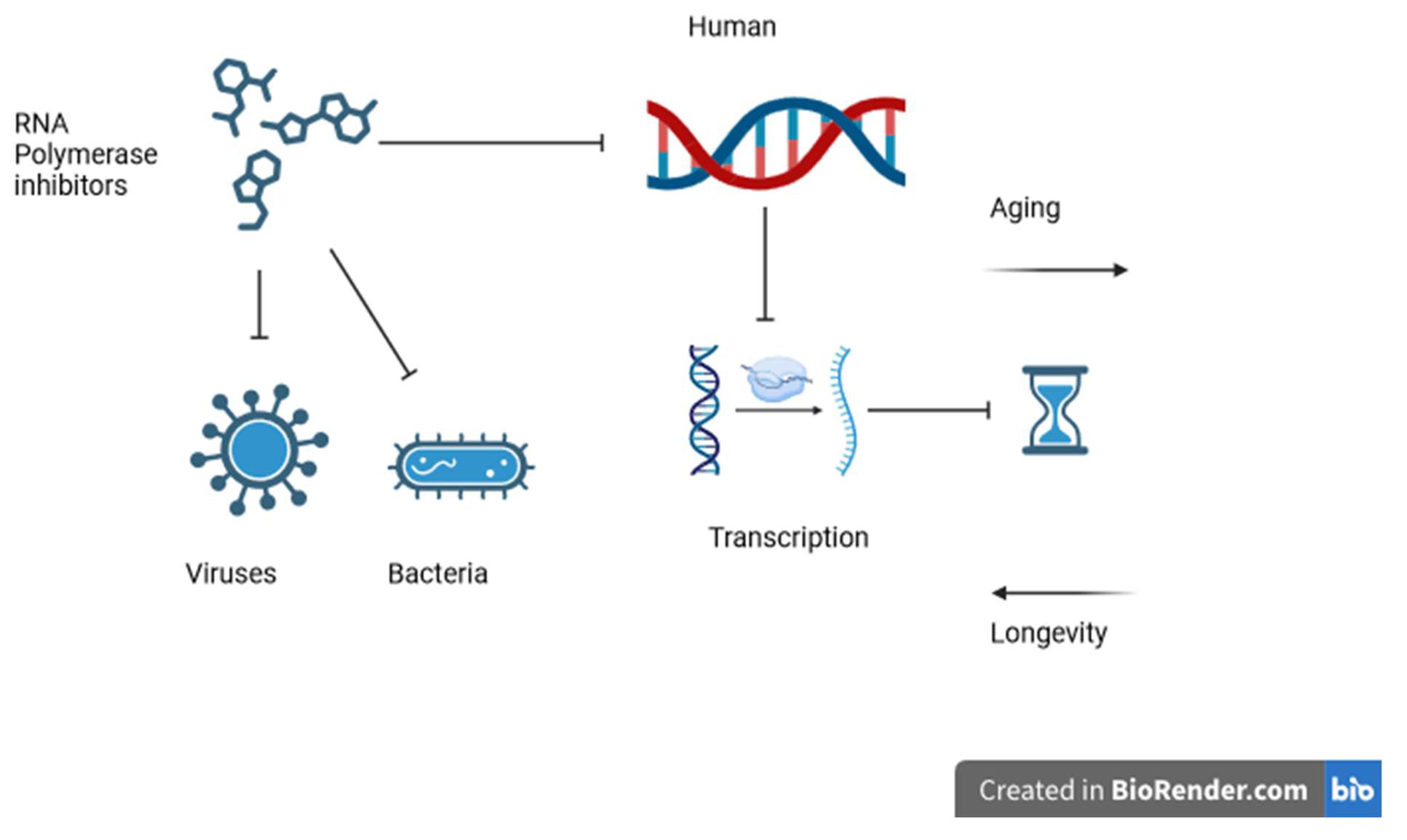

Figure 1.

Shows how RNA polymerase inhibitors affect viruses, bacteria, and possibly human RNA polymerases, modulating the transcription rate and changing the biological clock rate.

Figure 1.

Shows how RNA polymerase inhibitors affect viruses, bacteria, and possibly human RNA polymerases, modulating the transcription rate and changing the biological clock rate.

Partial Inhibition of RNA Polymerase and Aging

Experimental work demonstrated that partial inhibition of Pol I in a fruit fly model was associated with an increase in the lifespan of the flies. It is expected that extreme inhibition of transcription is incompatible with life by delaying transcription, supporting the hypothesis of the current review that transcription ends during the aging process (Martinez Corrales, Filer et al. 2020). Partial mutation of RNA polymerase 1 was associated with a decrease in the amount of ribosomal RNA (rRNA). The authors of that work concluded that less rRNA contributed to longevity. The current review shows that antiviral and bacterial drugs cause partial human polymerase inhibition. It is not clear whether partial inhibition can be applied to all subtypes of eukaryotic polymerases (Martinez Corrales, Filer et al. 2020). Other reports have demonstrated that active polymerase 3 in the gastrointestinal tract is correlated with a decreased life span of Drosophila (Filer, Thompson et al. 2017). The theory in this review is that transcription is part of the aging phenomenon rather than the abundance of RNA in the cytoplasm. More research is needed to verify this hypothesis.

NRF2 and RNA Polymerase II Inhibition

NRF2 (NF-E2-related factor-2) is an important transcription factor that promotes antioxidant capacity to overcome oxidative stress. It downregulates inflammatory and oxidative stressors. It is not clear how it dampens these aging factors. Studies have shown that NRF2 inhibits macrophage Pol II. NRF2 modulates inflammation transcription and controls the cell’s redox balance. These findings open the door to discussing the loop relationship between NRF2 and Pol II (Kobayashi, Suzuki et al. 2016).

Aging and Transcriptome Changes

Gene expression is regulated by the reorganization of the genome. With age, chromatin alterations are associated with changes in gene expression signatures. On the other hand, little research data are available about changes in the transcriptome. Multi-omics profiling revealed that ATAC-related and age-related modifications in the chromatin configuration of the livers of aged rats resulted in the formation of more accessible promoter regions without increasing the transcriptome yield. This outcome can be explained by a decrease in proximal pausing of the promoter of Pol II. The study concluded that disinhibition of moving Pol II is a marker of aging. In this review, it was concluded that moving Pol II is not only a marker but also a core mechanism of aging (Bozukova, Nikopoulou et al. 2022).

Gene expression profiles that are altered by aging were studied in mice to explore possible explanations for these changes. Recent advances in RNA-seq in combination with chromatin immunoprecipitation revealed variations in wild-type elderly mice. The experimental results showed that 40% of elongating RNA polymerases are stalled, resulting in lower transcriptional productivity at the gene-length level. These outcomes conflict with those of other studies. However, the cause of aging in this model is DNA damage with aging, not the increase in RNA activity. This transcriptional stress is caused by DNA damage, which explains the majority of gene expression modifications associated with aging, mainly in post-mitotic organs. Aging pathways include nutrient detection, autophagy, protein integrity, energy breakdown, immune activity, and cellular stress pliability pathways. Age-related transcriptional stress is evolutionarily conserved in all living organisms. Thus, the accumulation of DNA breaks during aging downregulates transcription, which creates an age-related profile that causes DNA instability, which is a key mechanism in aging-related disorders. These results indicate that transcription creates stress at two levels. One level is at the level of RNA polymerase, where partial interruption prolongs the life span, and the other level is at the DNA break, where the DNA repair mechanism promotes longevity (Lee, Lee et al. 2019, Gyenis, Chang et al. 2023). From experimental work, it can be said that the DNA/RNA cycle is a hybrid biological clock.

Pol II is the cornerstone component in reading the DNA code. During transcription initiation, the double-stranded DNA is opened by Pol II, exposing the DNA template to the active site. It is not well-known how to control the process of DNA opening or how to drive the process. In this study, all-atom steered molecular dynamics simulations were applied to identify a nonstop pathway of DNA opening in humans Pol II. This dynamic interaction involves displacement of the DNA strand to 55 A°. This movement allows the DNA to displace for nearly an entire circle. This strong maneuver depends on the violation of hydrogen bonds to allow Pol II to transcribe the genome. The interaction between the moving RNA polymerase and DNA is associated with the influence of polar and electrostatic forces (Lapierre and Hub 2022). Furthermore, Pol II opens DNA via an ATP-dependent mechanism (Dienemann, Schwalb et al. 2019). The speed of strand movements is proposed to affect the longevity of the organism. More research is needed to correlate the momentum, energy, and aging of the transcription apparatus.

Interaction Between Environmental Stress and Polymerase Inhibition

Since the mid-1970s, yeast cells have been tested for their ability to modify ribosome protein translation in response to growth needs and nutrient availability (Rhoads, Dinkova et al. 2006). However, 20 years later, strong convincing evidence for the fine-tuned regulation of the transcription output was revealed through the role of the secretory pathway and target of rapamycin (TOR) signaling in the inhibition of the fundamental RNA polymerases I, II, and III (Zaragoza, Ghavidel et al. 1998). Thus, the mTOR pathway coordinates the balance between the energy supply, environmental stress, and cellular bio-functions. Common signaling molecules (TOR kinase and components of the cell integrity pathway) were found to mediate coordinated transcriptional responses to nutrients and perturbations of cellular function. Maf1 was discovered to be a regulator of transcription (Pluta, Lefebvre et al. 2001). The MAF1 gene was discovered in mice and humans, and in yeast, a knockout of the Maf1 gene in mice is viable and productive (Willis 2018). Mammalian cell lines need MAF1 for successful repression of Pol III transcription in response to hunger and inhibition of TOR complex 1 (TORC1) or DNA damage (Willis and Moir 2018). It can be concluded that the cell nucleus is a closed box and that the aging phenomenon is a loop condition.

MAF1 Inhibition of Pol III as a Target for Treating Aging Disorders

Cardiac hypertrophy is a medical condition in which dysregulation of protein transcription, translation, and degradation is a potential explanation for this devastating condition. An animal model of cardiac hypertrophy in which MAF1 was knocked out was used to treat the cardiac condition. The successful restoration of MAF1 function and subsequent Pol III improved this condition. Furthermore, the application of Pol III inhibitors was effective in treating an animal model of cardiomyopathy. Notably, Erk1/2 also plays a role in inhibiting polymerase 3. It has been suggested that MAF1 binds ERK1/2 and that ERK1/2 inhibits Pol III (Sun, Chen et al. 2019).

MAF1 Regulation of Cancer

The transcription of RNA polymerase III is a canonical factor that controls cell growth and is frequently altered in many types of cancers. MAF1 suppresses RNA polymerase III transcription. Currently, it is unclear whether MAF1 is an important gene deregulated in various human tumors. Recently, altered MAF1 expression has been detected in colorectal and hepatocellular carcinomas and luminal breast malignancies. Research has shown that MAF1 is overexpressed in 39% of all breast cancer subcategories and that co-expression of MYC is amplified. MAF1 overexpression significantly correlated with hyper-methylation of the MAF1 promoter. Increased MAF1 expression correlated with five years of relapse-free survival in response to trastuzumab treatment. It was concluded that MAF1 is a prognostic biomarker in breast cancer. MAF1 and subsequent Pol III play heterogeneous roles in carcinogenesis based on the heterogeneous nature of cancer (Hokonohara, Nishida et al. 2019, Cabarcas-Petroski, Olshefsky et al. 2023)

Other Functions of MAF1

MAF1 is considered a key inhibitor of Pol III-dependent transcription because it is a sensor that responds to multiple extracellular factors affecting the functions and stability of cells, such as growth factors, nutrient availability, and stressors. The feedback phosphorylation mechanism controls MAF1 activity. The mTOR pathway controls the activity of MAF1, the mTOR kinase is responsible for the posttranslational feedback. The mammalian MAF1 also regulates Pol I and Pol II Transcription machinery. Furthermore, MAF1 modulates the activation or inhibition of Pol II to select target genes that affect cell growth and metabolism. While MAF1 inhibits targets such as TATA-binding protein (TBP) and fatty acid synthase (FASN), it activates the expression of PTEN, a major tumor suppressor inhibiting mTOR signaling. An increasing number of studies have indicated that MAF1 plays an important role in different physiological functions, including aging, longevity, and tumorigenesis (Zhang, Li et al. 2018).

PTEN Control of RNA Polymerase

PTEN is a master regulator of transcription. PTEN overexpression and PTEN knockdown models. It is currently under investigation. PTEN controls the expression of hundreds of genes, and knocking out PTEN in null cell lines results in the control of proximal pausing of the Pol II promoter in PTEN null cells. Furthermore, PTEN redistributes Pol II, which is important for the proper function of Pol II and pauses at a wide scope. These results support the understanding of the function of PTEN, PTEN Pol II-associated diseases, and possible new treatments (Abbas, Padmanabhan et al. 2019).

Gene transcription is a highly complex process with a high-order regulatory mechanism. The Pol II C-terminal domain (CTD) is exposed to posttranslational phosphorylation cycles of phosphorylation and dephosphorylation during the process of gene transcription. This mechanism offers interactive modulation for transcription initiation, elongation, termination, and adjustment. PTEN can dephosphorylate the Pol II catalytic site and bind to the promotor proximal region, regulating the process of global gene expression (Abbas, Romigh et al. 2019).

Polymerases and Cancer

Pol II is overexpressed in hematological tumors in response to proliferative demands. This basic enzyme has been a target of chemotherapy. Transgenic animals expressing Pol 1 are available. New drugs against Pol 1 are being tested (Bywater, Pearson et al. 2013).

The activity of Pol II promoters induces a selective profile of the transcriptome expression of genes with TATA box-containing promoters. The overexpression of TBP has been demonstrated in colon carcinoma (Johnson, Dubeau et al. 2003).

An injury to ribosome biosynthesis (called nucleolar stress), induced by interruption of RNA polymerase (Pol) ends in the activation of cell cycle checkpoints that result in the induction of p53 and then cell cycle arrest or cell death. Chemical inhibition of Pol I transcription has been used to treat cancer via nucleolar stress. Thus, Pol I transcription is a canonical mechanism controlling protein synthesis, which is an essential component of tumor growth. Furthermore, Pol I is important for nucleolus construction and stability, and Pol I inhibits p53 buildup, which opens the door to tumor development (Drygin, Rice et al. 2010, Drygin, Lin et al. 2011, Bywater, Poortinga et al. 2012, Ruggero 2012).

On the other hand, these anti-RNA polymerase drugs, such as actinomycin, are known to induce other tumors. In other words, these chemicals are both anticancer and carcinogenic (Harris 1976, Lien and Ou 1985, Schmahl 1986). This review focuses on the carcinogenic effects of inhibiting transcription machinery.

Capicua (CIC) is a transcriptional repressor with a conserved structure that is responsible for mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) expression or genetic transcription in human malignancies. The role of CIC in tumor progression and metastasis depends on the transcriptional control of genes at the transcriptional level. Research on CIC dysfunction has focused on selected categories of malignancy (Kim, Ponce et al. 2021).

Unstable genomes are a cornerstone mechanism in cancer development in humans. Abnormal protein production, either related to genetic (amplification, mutation, and deletion) or epigenetic alterations (DNA methylation and histone deacetylation), is involved in different pathways related to the evolution of malignancy. The overexpression of the 19q13 locus containing a novel pancreatic differentiation 2 (PD2) gene in humans corresponds to yeast RNA polymerase II-associated factor 1 (yPaf1) and is a component of the human Pol II-associated factor (hPAF) complex. This multidomain protein was first identified in yeast, Drosophila, and humans. Research advances have revealed multiple human functions, including efficient transcription elongation, mRNA quality control, and cell cycle regulation. The amplified protein was detected in multiple tumors. Moreover, an increase in PD2/hPaf1 resulted in a transformation connection to carcinogenesis. The potential overexpression of this complex protein and POL II may be linked to the development of cancers. Further research is needed to explore the relationship between human RNA polymerase II overexpression and tumorigenesis. It is not known whether the overexpression of Pol II can promote longevity or mediate aging. This review indicated that partial RNA polymerase inhibition can be a longevity tool, but how cells respond to RNA polymerase overexpression is unclear. It is not known how the overexpression of RNA polymerases affects the speed of transcription (Moniaux, Nemos et al. 2006, Chaudhary, Deb et al. 2007).

As living creatures are subjected to the aging phenomenon, physiological machines become weakened, including canonical RNA transcription and splicing. However, the molecular mechanisms responsible for the impairment of these processes have not been elucidated, and the regular transcriptional elongation speed (RNA polymerase II speed) increases with the aging process in animals and humans. Additionally, it was demonstrated that with these variations in elongation speed, scientists noted changes in splicing, including a decrease in transcription splicing with increased production of excess circular RNAs. Two longevity measures, caloric restriction, and insulin-IGF inhibition, both reversed most of these age-associated markers. Genetic makeup associated with reduced Pol II induces longevity in flies and worms. Similarly, overexpression of histone proteins inhibits the speed of Pol II and modified age-related chromatin structure changes, extending life span [

3]. In this review, it is proposed that the relationship between Pol II speed and aging is reciprocal. Aging impairs the transcriptional machinery, and the transcription machine induces aging. It is a loop of the control life (Debes, Papadakis et al. 2023).

Aging in animals is a syndrome characterized by the modification of transcription with a special signature affecting DNA repair responses, protein stability, immune activity, and stem cell remodeling (Lopez-Otin, Blasco et al. 2013). Additionally, some reports have demonstrated that transcriptional errors result in defective gene expression (Rangaraju, Solis et al. 2015, Vermulst, Denney et al. 2015, Martinez-Jimenez, Eling et al. 2017).

The catalytic subunit circPOLR2A of Pol II is overexpressed in aggressive glioblastoma multiform tumors (Chen, Mai et al. 2022). Other studies have shown a link between this catalytic subunit and gastric carcinoma and aggressive breast cancer (Xu, Liu et al. 2019, Jiang, Zhang et al. 2021). The overactive unit of Pol II corresponds to a resistant malignancy. It is not clear whether overactive RNA polymerase induces extreme longevity or responds to the high demands of tumors. Indeed, further research is important to determine the speed of elongation in these situations. Classic RNA polymerase inhibitors are not the best choice for treating special subtypes of cancers because they modify the biological clock to induce more severe malignancies.

Pol III is responsible for manufacturing a wide array of important transcripts, such as tRNA, 5S rRNA, and 7SL RNA, which play important roles in protein synthesis and trafficking. The overexpression of pol III is required for cell growth and proliferation. Unfortunately, malignant cells depend on the oncoprotein Pol III, which is overexpressed. Transcription factors such as TFIIIB and TFIIIC2, which stimulate pol III, are activated by other common oncoproteins, such as MYC oncogenes. On the other hand, tumor suppressors such as p53 inhibit the unnecessary expression of Pol III to limit neoplastic transformation (White 2004). POLIII has been implicated in many tumors, such as prostate and breast cancers (Winter, Sourvinos et al. 2000, Loveridge, Slater et al. 2020, Lautre, Richard et al. 2022).

Pol III and Longevity

Studies have tracked the role of Pol III in longevity. Pol III-transcriptional products are tangled in a wide range of cellular procedures, including translation, genome and transcriptome control, and RNA production. Abnormal Pol III function is involved in disorders such as leukodystrophy, Alzheimer’s disease, fragile X syndrome, and numerous types of malignancies. Recent research has shown that Pol III is conserved in terms of its structure and possibly functions in different species. It affects mTORC1. Pol III inhibition promotes longevity in yeast, worms, and flies, and Pol III affects the intestines of worms and flies, especially intestinal stem cells. Fascinatingly, Pol III activation achieved its effects by overcoming its key inhibitor Maf1.(Kulaberoglu, Malik et al. 2021) Studies have demonstrated that knockout improved gut-related abnormalities. (Filer, Thompson et al. 2017). This review suggested that the direct transcription apparatus itself controls aging and that the speed of RNA elongation is a master regulator of cell aging.

The Danger of Carcinogenic Effects of Human RNA Polymerase Inhibitors

Despite the value of longevity in overcoming diseases, the process of hormesis has a very devastating negative impact. Carcinogenesis depends on longevity strategies to overcome unfavorable conditions such as hypoxia and chemotherapy. (Klaunig 2005). The normal aging process suppresses carcinogenesis. Mechanisms such as telomere shortening and stem fatigue are very important defense mechanisms against oncogenesis. Despite the positive role of macroautophagic mechanisms in overcoming neurodegenerative disorders, they promote tumorigenesis. Notably, cellular senescence is protective against malignancy (Lopez-Otin, Pietrocola et al. 2023). On the other hand, an aberrant aging; quality of life induces an unstable genome, ending other forms of cancer. It seems that extreme conditions of aging or hormesis result in the development of tumors (Yoshioka, Kusumoto-Matsuo et al. 2021, Lopez-Otin, Pietrocola et al. 2023).

The process of aging is the mechanism by which injured cells are exposed to oxidative stress. It is responsible for the physiological phenomenon of an unstable genome, damaged fat, and damaged proteins. These changes culminate in apoptosis. Unfortunate cells that evade normal aging mechanisms undergo carcinogenesis. p53, the guardian of the genome, functions as a tumor suppressor by controlling aging and apoptosis and preventing carcinogenesis(Horikawa 2020).

The notion of longevity or hormesis is a double-edged sword depending on the dose. The dose induces biphasic or U-shaped effects; in this review, this mechanism can be applied to RNA polymerase. At moderate doses, it promotes cell longevity or trophic effects, and it is a potential candidate for treating diseases such as neurodegenerative diseases, diabetes, and obesity. However, high doses of these drugs induce nongenotoxic carcinogenesis (Calabrese and Baldwin 1998, Fukushima, Kinoshita et al. 2005). It is important to note that blocking RNA polymerase produces nucleolar stress, which is beneficial for treating cancer. However, partial inhibition of RNA polymerase activity could produce longevity models in contrast to blocking the transcription machinery. Further research to test the dose-response curve of RNA inhibition was performed. We predicted a U-shaped response curve.

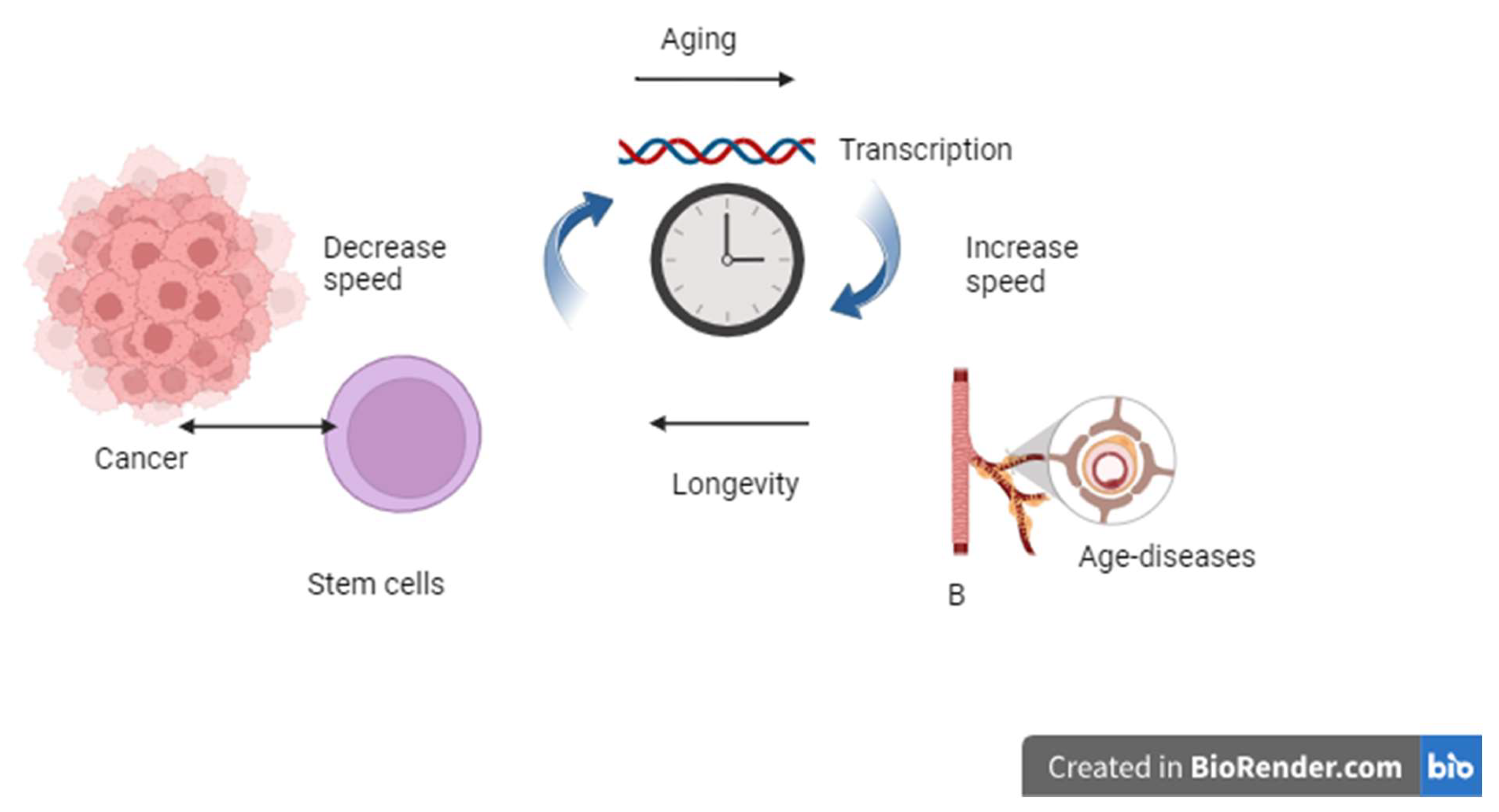

Figure 2.

The effects of the speed of the transcription machine as a biological clock. High-speed transcription ends in the aging process and disease, while a slow transcription rate promotes longevity, and excess longevity stimulates stem cells to initiate cancer progression.

Figure 2.

The effects of the speed of the transcription machine as a biological clock. High-speed transcription ends in the aging process and disease, while a slow transcription rate promotes longevity, and excess longevity stimulates stem cells to initiate cancer progression.

Antiangiogenic Properties and Carcinogenesis

Despite the major concern about human RNA polymerase drugs, there is hope to overcome the risks of tumorigenesis. Rifampicin, a well-known anti-tuberculosis medication, has been tested for decades without clinical evidence of cancer. The major concern with rifampicin is resistance (Ugwu, Onah et al. 2020, Ulasi, Nwachukwu et al. 2022). The important question is why this drug is not a non-genotoxic carcinogen. The answer in this situation could be the ability of rifampicin to inhibit vascular endothelial growth factor.

Vascular endothelial factor (VEGF). Is a very important factor in the process of aging. Vascular insufficiency is a marker and a mechanism of organ aging. An increase in the expression of VEGF is mitogenic and a cofactor of hormesis, and it is expected to play a role in non-genotoxic carcinogen induction. On the other hand, blocking vascular adequacy is part of the other coin, where it increases inflammation, oxidative burden, unstable genomics, and finally genotoxic carcinogenesis. It can be concluded that VEGF is a key target for understanding and managing tumorigenesis (Grunewald, Kumar et al. 2021). It is believed that combination therapy, including VEGF-modulating drugs, should be part of cancer chemotherapy, especially for hepatic tumors. This may prevent the use of RNA polymerase inhibitors.

Experiments have demonstrated the strong chemotherapeutic effects of rifampicin on hepatic cancer. This study showed that low doses of rifampicin inhibited neovascularization. This dual mechanism is postulated to protect against RNA polymerase inhibition. The presence of low concentrations of rifampicin in the hepatobiliary system was confirmed to inhibit carcinogenesis (Shichiri and Tanaka 2010). However, the study concluded that rifampicin is still an adjuvant therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Indeed, the development of a drug with dual action will be a good strategy to fight cancer. The current review recommends focusing research on specific polymerase inhibitors for liver cells with associated or combined antiangiogenic effects. In this work, it is important to use longevity, oxidative stress, microRNA, and genotoxic biomarkers as precision medicine strategies (Vahidi, Agah et al. 2024).

Regarding the debate about the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma after direct antiviral medication in decompensated hepatic patients, we propose that advanced cirrhotic livers are in an extreme mitosis/necrosis cycle and that the combined effects of RNA polymerase inhibitors and hormesis induce extreme conditions favorable for carcinogenesis. The current review does not recommend drugs such as sofosbuvir for decompensated hepatic patients, despite this drug having the potential to theoretically increase the overall survival rate.

Future Prospects

This review has tracked the potential role of RNA polymerases in the aging process. Although the crystal structure of human RNA polymerase is not available, the similar effects of different bacterial and viral anti-RNA polymerases predict a conserved structure from yeast and possibly humans. Using computer simulation, it is relatively easy to obtain the human target. To confirm the hypothesis of this review, we can test serial toxic doses of rifampicin and direct-acting drugs such as sofosbuvir both in vivo and in vitro in both animal and human cell lines, and it will be possible to track longevity markers and measure the expression of human RNA polymerase specifically. If the data indicates a positive cellular anti-aging pattern with changes in human RNA polymerase expression levels, the hypotheses will be on the right track. Other longevity markers and signaling pathways are secondary or interacting factors.

This experimental work can be applied to humans as healthy candidates receiving sofosbuvir to test the methylation of DNA, expression of RNA polymerases, and other longevity/hormesis markers.

Conclusion

From this review, it is concluded that RNA polymerases are suggested to be conserved across different species, and toxic doses are also suggested to inhibit human RNA polymerase. This mechanism induces longevity in human cells. RNA polymerase inhibition reduces the basal function of RNA transcription, promoting antiaging mechanisms. The RNA transcription machinery can be considered a biological clock in which aging is an unavoidable condition of a normal life span. We believe that the development of human polymerase inhibitors could lead to the development of a new group of antiaging drugs for treating conditions such as neurodegenerative disorders, for example, Alzheimer’s disease or Parkinson’s disease. It is important to focus research on human RNA polymerases acting as drugs, either inhibitors or enhancers, to treat both types of diseases, either aging- or hormesis-related conditions. The major drawback of the potential development of human versions of polymerase inhibitors is the aberrant stimulation of stem cells, which may lead to the development of new forms of cancer. It is hoped that specific anti-RNA polymerase-modifying drugs that are selective for special organs, such as the brain, could have multiple indications. It may be useful to use direct-acting drugs at higher doses for a wider range of diseases in combination with antiangiogenic drug combinations with an expected safety profile to treat many diseases.

Author Contributions

Doaa Ghorab shared this hypothesis with Ahmed Helaly. Ahmed Helaly was responsible for the hypothesis, writing, and submission.

Funding

No funding sources.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the Forensic and Toxicology Department, Faculty of Medicine, Mansoura University for the valuable support.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Human Ethics

Not applicable.

References

- Sofosbuvir. LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury. Bethesda (MD).

- Abbas, A.; Padmanabhan, R.; Romigh, T.; Eng, C. PTEN modulates gene transcription by redistributing genome-wide RNA polymerase II occupancy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2019, 28, 2826–2834. [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.; Romigh, T.; Eng, C. PTEN interacts with RNA polymerase II to dephosphorylate polymerase II C-terminal domain. Oncotarget 2019, 10, 4951–4959. [CrossRef]

- Abdelhamed, W.; El-Kassas, M. Hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatitis C virus treatments: The bold and the beautiful. J. Viral Hepat. 2022, 30, 148–159. [CrossRef]

- Admasu, T.D.; Batchu, K.C.; Barardo, D.; Ng, L.F.; Lam, V.Y.M.; Xiao, L.; Cazenave-Gassiot, A.; Wenk, M.R.; Tolwinski, N.S.; Gruber, J. Drug Synergy Slows Aging and Improves Healthspan through IGF and SREBP Lipid Signaling. Dev. Cell 2018, 47, 67–79.e5. [CrossRef]

- Agathokleous, E.; Kitao, M.; Calabrese, E.J. Hormesis: Highly Generalizable and Beyond Laboratory. Trends Plant Sci. 2020, 25, 1076–1086. [CrossRef]

- Augusti, K.T.; Jose, R.; Sajitha, G.R.; Augustine, P. A Rethinking on the Benefits and Drawbacks of Common Antioxidants and a Proposal to Look for the Antioxidants in Allium Products as Ideal Agents: A Review. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 2011, 27, 6–20. [CrossRef]

- Bader, C.D.; Panter, F.; Garcia, R.; Tchesnokov, E.P.; Haid, S.; Walt, C.; Spröer, C.; Kiefer, A.F.; Götte, M.; Overmann, J.; et al. Sandacrabins – Structurally Unique Antiviral RNA Polymerase Inhibitors from a Rare Myxobacterium**. Chem. – A Eur. J. 2022, 28, e202104484. [CrossRef]

- Biswas, B. B., A. Ganguly and A. Das (1975). “Eukaryotic RNA polymerases and the factors that control them.” Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol 15(0): 145-184. [CrossRef]

- Blagosklonny, M.V. Aging and Immortality: Quasi-Programmed Senescence and Its Pharmacologic Inhibition. Cell Cycle 2006, 5, 2087–2102. [CrossRef]

- Blagosklonny, M.V. An anti-aging drug today: from senescence-promoting genes to anti-aging pill. Drug Discov. Today 2007, 12, 218–224. [CrossRef]

- Blair, D. G. (1988). “Eukaryotic RNA polymerases.” Comp Biochem Physiol B 89(4): 647-670.

- Bozukova, M.; Nikopoulou, C.; Kleinenkuhnen, N.; Grbavac, D.; Goetsch, K.; Tessarz, P. Aging is associated with increased chromatin accessibility and reduced polymerase pausing in liver. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2022, 18, e11002. [CrossRef]

- Bywater, M.J.; Pearson, R.B.; McArthur, G.A.; Hannan, R.D. Dysregulation of the basal RNA polymerase transcription apparatus in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2013, 13, 299–314. [CrossRef]

- Bywater, M.J.; Poortinga, G.; Sanij, E.; Hein, N.; Peck, A.; Cullinane, C.; Wall, M.; Cluse, L.; Drygin, D.; Anderes, K.; et al. Inhibition of RNA Polymerase I as a Therapeutic Strategy to Promote Cancer-Specific Activation of p53. Cancer Cell 2012, 22, 51–65. [CrossRef]

- Cabarcas-Petroski, S.; Olshefsky, G.; Schramm, L. MAF1 is a predictive biomarker in HER2 positive breast cancer. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0291549. [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, E. J. and L. A. Baldwin (1998). “Can the concept of hormesis Be generalized to carcinogenesis?” Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 28(3): 230-241.

- Calabrese, E.J.; Nascarella, M.; Pressman, P.; Hayes, A.W.; Dhawan, G.; Kapoor, R.; Calabrese, V.; Agathokleous, E. Hormesis determines lifespan. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 94, 102181. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, E.A.; Korzheva, N.; Mustaev, A.; Murakami, K.; Nair, S.; Goldfarb, A.; Darst, S.A. Structural Mechanism for Rifampicin Inhibition of Bacterial RNA Polymerase. 2001, 104, 901–912. [CrossRef]

- Celik, I., M. Erol and Z. Duzgun (2022). “In silico evaluation of potential inhibitory activity of remdesivir, favipiravir, ribavirin and galidesivir active forms on SARS-CoV-2 RNA polymerase.” Mol Divers 26(1): 279-292. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, K.; Deb, S.; Moniaux, N.; Ponnusamy, M.P.; Batra, S.K. Human RNA polymerase II-associated factor complex: dysregulation in cancer. Oncogene 2007, 26, 7499–7507. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Mai, Q.; Wang, Q.; Gou, Q.; Shi, F.; Mo, Z.; Cui, W.; Zhuang, W.; Li, W.; Xu, R.; et al. CircPOLR2A Promotes Proliferation and Impedes Apoptosis of Glioblastoma Multiforme Cells by Up-regulating POU3F2 to Facilitate SOX9 Transcription. Neuroscience 2022, 503, 118–130. [CrossRef]

- Debès, C.; Papadakis, A.; Grönke, S.; Karalay, Ö.; Tain, L.S.; Mizi, A.; Nakamura, S.; Hahn, O.; Weigelt, C.; Josipovic, N.; et al. Ageing-associated changes in transcriptional elongation influence longevity. Nature 2023, 616, 814–821. [CrossRef]

- Martínez, C.D.; Gómez-Rubio, M.; Gómez-Domínguez, C. Is hepatitis C direct-acting antiviral therapy a risk factor for the development and recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma? Narrative literature review and clinical practice recommendations. Ann. Hepatol. 2020, 21, 100225. [CrossRef]

- Dienemann, C.; Schwalb, B.; Schilbach, S.; Cramer, P. Promoter Distortion and Opening in the RNA Polymerase II Cleft. Mol. Cell 2019, 73, 97–106.e4. [CrossRef]

- Doğan, M.F.; Kaya, K.; Demirel, H.H.; Başeğmez, M.; Şahin, Y.; Çiftçi, O.; Oban, V.; Dikeç, G. The effect of vitamin C supplementation on favipiravir-induced oxidative stress and proinflammatory damage in livers and kidneys of rats. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2023, 45, 521–526. [CrossRef]

- Drygin, D.; Lin, A.; Bliesath, J.; Ho, C.B.; O’Brien, S.E.; Proffitt, C.; Omori, M.; Haddach, M.; Schwaebe, M.K.; Siddiqui-Jain, A.; et al. Targeting RNA Polymerase I with an Oral Small Molecule CX-5461 Inhibits Ribosomal RNA Synthesis and Solid Tumor Growth. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 1418–1430. [CrossRef]

- Drygin, D.; Rice, W.G.; Grummt, I. The RNA Polymerase I Transcription Machinery: An Emerging Target for the Treatment of Cancer. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2010, 50, 131–156. [CrossRef]

- Feldberg, R.S.; Chang, S.C.; Kotik, A.N.; Nadler, M.; Neuwirth, Z.; Sundstrom, D.C.; Thompson, N.H. In vitro mechanism of inhibition of bacterial cell growth by allicin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1988, 32, 1763–1768. [CrossRef]

- Filer, D.; Thompson, M.A.; Takhaveev, V.; Dobson, A.J.; Kotronaki, I.; Green, J.W.M.; Heinemann, M.; Tullet, J.M.A.; Alic, N. RNA polymerase III limits longevity downstream of TORC1. Nature 2017, 552, 263–267. [CrossRef]

- Fukushima, S.; Kinoshita, A.; Puatanachokchai, R.; Kushida, M.; Wanibuchi, H.; Morimura, K. Hormesis and dose–response-mediated mechanisms in carcinogenesis: evidence for a threshold in carcinogenicity of non-genotoxic carcinogens. Carcinog. 2005, 26, 1835–1845. [CrossRef]

- Golegaonkar, S.; Tabrez, S.S.; Pandit, A.; Sethurathinam, S.; Jagadeeshaprasad, M.G.; Bansode, S.; Sampathkumar, S.; Kulkarni, M.J.; Mukhopadhyay, A. Rifampicin reduces advanced glycation end products and activates DAF-16 to increase lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging Cell 2015, 14, 463–473. [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, S. J. and J. C. Zomerdijk (2013). “Basic mechanisms in RNA polymerase I transcription of the ribosomal RNA genes.” Subcell Biochem 61: 211-236. [CrossRef]

- Grunewald, M.; Kumar, S.; Sharife, H.; Volinsky, E.; Gileles-Hillel, A.; Licht, T.; Permyakova, A.; Hinden, L.; Azar, S.; Friedmann, Y.; et al. Counteracting age-related VEGF signaling insufficiency promotes healthy aging and extends life span. Science 2021, 373, 533–+. [CrossRef]

- Gunaydin-Akyildiz, A.; Aksoy, N.; Boran, T.; Ilhan, E.N.; Ozhan, G. Favipiravir induces oxidative stress and genotoxicity in cardiac and skin cells. Toxicol. Lett. 2022, 371, 9–16. [CrossRef]

- Gyenis, A.; Chang, J.; Demmers, J.J.P.G.; Bruens, S.T.; Barnhoorn, S.; Brandt, R.M.C.; Baar, M.P.; Raseta, M.; Derks, K.W.J.; Hoeijmakers, J.H.J.; et al. Genome-wide RNA polymerase stalling shapes the transcriptome during aging. Nat. Genet. 2023, 55, 268–279. [CrossRef]

- Harris, C. C. (1976). “The carcinogenicity of anticancer drugs: a hazard in man.” Cancer 37(2 Suppl): 1014-1023. [CrossRef]

- Hokonohara, K.; Nishida, N.; Miyoshi, N.; Takahashi, H.; Haraguchi, N.; Hata, T.; Matsuda, C.; Mizushima, T.; Doki, Y.; Mori, M. Involvement of MAF1 homolog, negative regulator of RNA polymerase III in colorectal cancer progression. Int. J. Oncol. 2019, 54, 1001–1009. [CrossRef]

- Horikawa, I. (2020). “Balancing and Differentiating p53 Activities toward Longevity and No Cancer?” Cancer Res 80(23): 5164-5165. [CrossRef]

- Horvath, S.; Raj, K. DNA methylation-based biomarkers and the epigenetic clock theory of ageing. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2018, 19, 371–384. [CrossRef]

- Irschik, H.; Augustiniak, H.; Gerth, K.; Höfle, G.; Reichenbach, H. Antibiotics from gliding bacteria. No. 68. The Ripostatins, Novel Inhibitors of Eubacterial RNA Polymerase Isolated from Myxobacteria. J. Antibiot. 1995, 48, 787–792. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Li, F.; Ma, X.; Wu, F.; Miao, J.; Li, Q.; Wang, X.; Sun, R.; Yang, Y.; et al. POLR2A Promotes the Proliferation of Gastric Cancer Cells by Advancing the Overall Cell Cycle Progression. Front. Genet. 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S. A., L. Dubeau, M. Kawalek, A. Dervan, A. H. Schonthal, C. V. Dang and D. L. Johnson (2003). “Increased expression of TATA-binding protein, the central transcription factor, can contribute to oncogenesis.” Mol Cell Biol 23(9): 3043-3051. [CrossRef]

- Kandhaya-Pillai, R., X. Yang, T. Tchkonia, G. M. Martin, J. L. Kirkland and J. Oshima (2022). “TNF-alpha/IFN-gamma synergy amplifies senescence-associated inflammation and SARS-CoV-2 receptor expression via hyper-activated JAK/STAT1.” Aging Cell 21(6): e13646. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. W., R. K. Ponce and R. A. Okimoto (2021). “Capicua in Human Cancer.” Trends Cancer 7(1): 77-86. [CrossRef]

- Klaunig, J.E. Cancer Biology and Hormesis: Commentary. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2005, 35, 593–594. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, E.H.; Suzuki, T.; Funayama, R.; Nagashima, T.; Hayashi, M.; Sekine, H.; Tanaka, N.; Moriguchi, T.; Motohashi, H.; Nakayama, K.; et al. Nrf2 suppresses macrophage inflammatory response by blocking proinflammatory cytokine transcription. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11624. [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, S.M.; Dixit, N.M. Ribavirin-Induced Anemia in Hepatitis C Virus Patients Undergoing Combination Therapy. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2011, 7, e1001072. [CrossRef]

- Kulaberoglu, Y., Y. Malik, G. Borland, C. Selman, N. Alic and J. M. A. Tullet (2021). “RNA Polymerase III, Ageing and Longevity.” Front Genet 12: 705122. [CrossRef]

- Lapierre, J.; Hub, J.S. DNA opening during transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II in atomic detail. Biophys. J. 2022, 121, 4299–4310. [CrossRef]

- Lautré, W.; Richard, E.; Feugeas, J.-P.; Dumay-Odelot, H.; Teichmann, M. The POLR3G Subunit of Human RNA Polymerase III Regulates Tumorigenesis and Metastasis in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 5732. [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.H.; Baek, S.Y.; Park, J.Y.; Kim, Y.W. Rifampicin activates AMPK and alleviates oxidative stress in the liver as mediated with Nrf2 signaling. Chem. Interactions 2020, 315, 108889. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H.; Lee, J.-H.; Lee, H.-Y.; Min, K.-J. Sirtuin signaling in cellular senescence and aging. BMB Rep. 2019, 52, 24–34. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-W.; Chen, L.-S.; Yang, S.-S.; Huang, Y.-H.; Lee, T.-Y. Direct-Acting Antiviral Therapy for Hepatitis C Virus in Patients with BCLC Stage B/C Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Viruses 2022, 14, 2316. [CrossRef]

- Levine, M.E.; Lu, A.T.; Quach, A.; Chen, B.H.; Assimes, T.L.; Bandinelli, S.; Hou, L.; Baccarelli, A.A.; Stewart, J.D.; Li, Y.; et al. An epigenetic biomarker of aging for lifespan and healthspan. Aging 2018, 10, 573–591. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-L.; Xie, Y.; Chen, Y.-L.; Zhang, Z.-M.; Tao, Y.-F.; Li, G.; Wu, D.; Wang, H.-R.; Zhuo, R.; Pan, J.-J.; et al. The RNA polymerase II subunit B (RPB2) functions as a growth regulator in human glioblastoma. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2023, 674, 170–182. [CrossRef]

- Lien, E. J. and X. C. Ou (1985). “Carcinogenicity of some anticancer drugs--a survey.” J Clin Hosp Pharm 10(3): 223-242. [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.-L.; Liu, Y.; Liu, M.; Hu, H.; Pan, Y.; Fan, X.-J.; Hu, X.-M.; Zou, W.-W. Inhibition of Hydrogen Peroxide-Induced Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells Aging by Allicin Depends on Sirtuin1 Activation. Med Sci. Monit. 2017, 23, 563–570. [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Otin, C., M. A. Blasco, L. Partridge, M. Serrano and G. Kroemer (2013). “The hallmarks of aging.” Cell 153(6): 1194-1217. [CrossRef]

- López-Otín, C.; Pietrocola, F.; Roiz-Valle, D.; Galluzzi, L.; Kroemer, G. Meta-hallmarks of aging and cancer. Cell Metab. 2023, 35, 12–35. [CrossRef]

- Loveridge, C.J.; Slater, S.; Campbell, K.J.; Nam, N.A.; Knight, J.; Ahmad, I.; Hedley, A.; Lilla, S.; Repiscak, P.; Patel, R.; et al. BRF1 accelerates prostate tumourigenesis and perturbs immune infiltration. Oncogene 2019, 39, 1797–1806. [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Su, S.; Yang, H.; Jiang, S. Antivirals with common targets against highly pathogenic viruses. Cell 2021, 184, 1604–1620. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Jimenez, C.P.; Eling, N.; Chen, H.-C.; Vallejos, C.A.; Kolodziejczyk, A.A.; Connor, F.; Stojic, L.; Rayner, T.F.; Stubbington, M.J.T.; Teichmann, S.A.; et al. Aging increases cell-to-cell transcriptional variability upon immune stimulation. Science 2017, 355, 1433–1436. [CrossRef]

- Corrales, G.M.; Filer, D.; Wenz, K.C.; Rogan, A.; Phillips, G.; Li, M.; Feseha, Y.; Broughton, S.J.; Alic, N. Partial Inhibition of RNA Polymerase I Promotes Animal Health and Longevity. Cell Rep. 2020, 30, 1661–1669.e4. [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, R. L., M. Molenaars, B. V. Schomakers, A. W. Gao, R. Kamble, A. Jongejan, M. van Weeghel, A. B. P. van Kuilenburg, R. Possemato, R. H. Houtkooper and G. E. Janssens (2023). “Anti-retroviral treatment with zidovudine alters pyrimidine metabolism, reduces translation, and extends healthy longevity via ATF-4.” Cell Rep 42(1): 111928. [CrossRef]

- Moniaux, N., C. Nemos, B. M. Schmied, S. C. Chauhan, S. Deb, K. Morikane, A. Choudhury, M. Vanlith, M. Sutherlin, J. M. Sikela, M. A. Hollingsworth and S. K. Batra (2006). “The human homologue of the RNA polymerase II-associated factor 1 (hPaf1), localized on the 19q13 amplicon, is associated with tumorigenesis.” Oncogene 25(23): 3247-3257. [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Lee, S.; Yoon, J.; Kim, E.; Park, S. Allicin protects porcine oocytes against damage during aging in vitro. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2019, 86, 1116–1125. [CrossRef]

- Pluta, K.; Lefebvre, O.; Martin, N.C.; Smagowicz, W.J.; Stanford, D.R.; Ellis, S.R.; Hopper, A.K.; Sentenac, A.; Boguta, M. Maf1p, a Negative Effector of RNA Polymerase III in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001, 21, 5031–5040. [CrossRef]

- Rangaraju, S., G. M. Solis, R. C. Thompson, R. L. Gomez-Amaro, L. Kurian, S. E. Encalada, A. B. Niculescu, 3rd, D. R. Salomon and M. Petrascheck (2015). “Suppression of transcriptional drift extends C. elegans lifespan by postponing the onset of mortality.” Elife 4: e08833. [CrossRef]

- Rhoads, R. E., T. D. Dinkova and N. L. Korneeva (2006). “Mechanism and regulation of translation in C. elegans.” WormBook: 1-18.

- Ruggero, D. Revisiting the Nucleolus: From Marker to Dynamic Integrator of Cancer Signaling. Sci. Signal. 2012, 5, pe38–pe38. [CrossRef]

- Sancar, A. and R. N. Van Gelder (2021). “Clocks, cancer, and chronochemotherapy.” Science 371(6524). [CrossRef]

- Santana-Salgado, I.; Bautista-Santos, A.; Moreno-Alcántar, R. Risk factors for developing hepatocellular carcinoma in patients treated with direct-acting antivirals. Rev. De Gastroenterol. De Mex. 2022, 87, 455–461. [CrossRef]

- Sapena, V., M. Enea, F. Torres, C. Celsa, J. Rios, G. E. M. Rizzo, P. Nahon, Z. Marino, R. Tateishi, T. Minami, A. Sangiovanni, X. Forns, H. Toyoda, S. Brillanti, F. Conti, E. Degasperi, M. L. Yu, P. C. Tsai, K. Jean, M. El Kassas, H. I. Shousha, A. Omar, C. Zavaglia, H. Nagata, M. Nakagawa, Y. Asahina, A. G. Singal, C. Murphy, M. Kohla, C. Masetti, J. F. Dufour, N. Merchante, L. Cavalletto, L. L. Chemello, S. Pol, J. Crespo, J. L. Calleja, R. Villani, G. Serviddio, A. Zanetto, S. Shalaby, F. P. Russo, R. Bielen, F. Trevisani, C. Camma, J. Bruix, G. Cabibbo and M. Reig (2022). “Hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence after direct-acting antiviral therapy: an individual patient data meta-analysis.” Gut 71(3): 593-604. [CrossRef]

- Schmähl, D. Carcinogenicity of anticancer drugs and especially alkylating agents. 1986, 29–35.

- Scott, P. H., C. A. Cairns, J. E. Sutcliffe, H. M. Alzuherri, A. McLees, A. G. Winter and R. J. White (2001). “Regulation of RNA polymerase III transcription during cell cycle entry.” J Biol Chem 276(2): 1005-1014. [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Cheng, X.; Li, D.; Meng, Q. Investigation of rifampicin-induced hepatotoxicity in rat hepatocytes maintained in gel entrapment culture. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2008, 25, 265–274. [CrossRef]

- Shichiri, M.; Tanaka, Y. Inhibition of cancer progression by rifampicin: Involvement of antiangiogenic and anti-tumor effects. Cell Cycle 2010, 9, 64–68. [CrossRef]

- Soota, K.; Maliakkal, B. Ribavirin induced hemolysis: A novel mechanism of action against chronic hepatitis C virus infection. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 16184–90. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y., C. Chen, R. Xue, Y. Wang, B. Dong, J. Li, C. Chen, J. Jiang, W. Fan, Z. Liang, H. Huang, R. Fang, G. Dai, Y. Yan, T. Yang, X. Li, Z. P. Huang, Y. Dong and C. Liu (2019). “Maf1 ameliorates cardiac hypertrophy by inhibiting RNA polymerase III through ERK1/2.” Theranostics 9(24): 7268-7281.

- Tang, W.; Liu, S.; Degen, D.; Ebright, R.H.; Prusov, E.V. Synthesis and Evaluation of Novel Analogues of Ripostatins. Chem. – A Eur. J. 2014, 20, 12310–12319. [CrossRef]

- Thanapairoje, K.; Junsiritrakhoon, S.; Wichaiyo, S.; Osman, M.A.; Supharattanasitthi, W. Anti-ageing effects of FDA-approved medicines: a focused review. J. Basic Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2023, 34, 277–289. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.-L.; Cheng, J.-S.; Liu, P.-F.; Chang, T.-H.; Sun, W.-C.; Chen, W.-C.; Shu, C.-W. Sofosbuvir induces gene expression for promoting cell proliferation and migration of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Aging 2022, 14, 5710–5726. [CrossRef]

- Turowski, T.W.; Tollervey, D. Transcription by RNA polymerase III: insights into mechanism and regulation. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2016, 44, 1367–1375. [CrossRef]

- Ugwu, K. O., I. S. Onah, G. C. Mbah and I. M. Ezeonu (2020). “Rifampicin resistance patterns and dynamics of tuberculosis and drug-resistant tuberculosis in Enugu, South Eastern Nigeria.” J Infect Dev Ctries 14(9): 1011-1018. [CrossRef]

- Ulasi, A.; Nwachukwu, N.; Onyeagba, R.; Umeham, S.; Amadi, A. Prevalence of rifampicin resistant tuberculosis among pulmonary tuberculosis patients In Enugu, Nigeria. Afr. Heal. Sci. 2022, 22, 156–161. [CrossRef]

- Vahidi, S.; Agah, S.; Mirzajani, E.; Gharakhyli, E.A.; Norollahi, S.E.; Taramsari, M.R.; Babaei, K.; Samadani, A.A. microRNAs, oxidative stress, and genotoxicity as the main inducers in the pathobiology of cancer development. Horm. Mol. Biol. Clin. Investig. 2024, 45, 55–73. [CrossRef]

- Ramani, M.K.V.; Yang, W.; Irani, S.; Zhang, Y. Simplicity is the Ultimate Sophistication—Crosstalk of Post-translational Modifications on the RNA Polymerase II. J. Mol. Biol. 2021, 433, 166912–166912. [CrossRef]

- Vermulst, M.; Denney, A.S.; Lang, M.J.; Hung, C.-W.; Moore, S.; Moseley, M.A.; Thompson, J.W.; Madden, V.; Gauer, J.; Wolfe, K.J.; et al. Transcription errors induce proteotoxic stress and shorten cellular lifespan. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Werner, F.; Grohmann, D. Evolution of multisubunit RNA polymerases in the three domains of life. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 9, 85–98. [CrossRef]

- White, R.J. RNA polymerase III transcription and cancer. Oncogene 2004, 23, 3208–3216. [CrossRef]

- White, R.J.; Gottlieb, T.M.; Downes, C.S.; Jackson, S.P. Cell Cycle Regulation of RNA Polymerase III Transcription. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1995, 15, 6653–6662. [CrossRef]

- Willis, I. M. (2018). “Maf1 phenotypes and cell physiology.” Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech 1861(4): 330-337. [CrossRef]

- Willis, I.M.; Moir, R.D. Signaling to and from the RNA Polymerase III Transcription and Processing Machinery. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2018, 87, 75–100. [CrossRef]

- Winter, A.G.; Sourvinos, G.; Allison, S.J.; Tosh, K.; Scott, P.H.; Spandidos, D.A.; White, R.J. RNA polymerase III transcription factor TFIIIC2 is overexpressed in ovarian tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2000, 97, 12619–12624. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Stewart, S.; Van der Jeught, K.; Agarwal, P.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhao, G.; et al. Precise targeting of POLR2A as a therapeutic strategy for human triple negative breast cancer. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2019, 14, 388–397. [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, K.-I.; Kusumoto-Matsuo, R.; Matsuno, Y.; Ishiai, M. Genomic Instability and Cancer Risk Associated with Erroneous DNA Repair. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12254. [CrossRef]

- Yousefsani, B.S.; Nabavi, N.; Pourahmad, J. Contrasting Role of Dose Increase in Modulating Sofosbuvir-Induced Hepatocyte Toxicity. Drug Res. 2020, 70, 137–144. [CrossRef]

- Zaragoza, D.; Ghavidel, A.; Heitman, J.; Schultz, M.C. Rapamycin Induces the G0 Program of Transcriptional Repression in Yeast by Interfering with the TOR Signaling Pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998, 18, 4463–4470. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S., X. Li, H. Y. Wang and X. F. Steven Zheng (2018). “Beyond regulation of pol III: Role of MAF1 in growth, metabolism, aging and cancer.” Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech 1861(4): 338-343. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).