1. Introduction

The universal demand for sustainable and renewable energy sources has grown exponentially due to concerns about environmental degradation, fossil fuel depletion, and greenhouse gas emissions. Among various renewable energy sources, biodiesel has emerged as a promising alternative, offering a cleaner and more sustainable option for powering industries and transportation [

1,

2]. Biodiesel is primarily produced from vegetable oils, animal fats, and other renewable feedstock. However, the rising demand for edible oils in biodiesel production has raised concerns about food security, necessitating the exploration of non-edible and underutilized oilseed crops [

3].

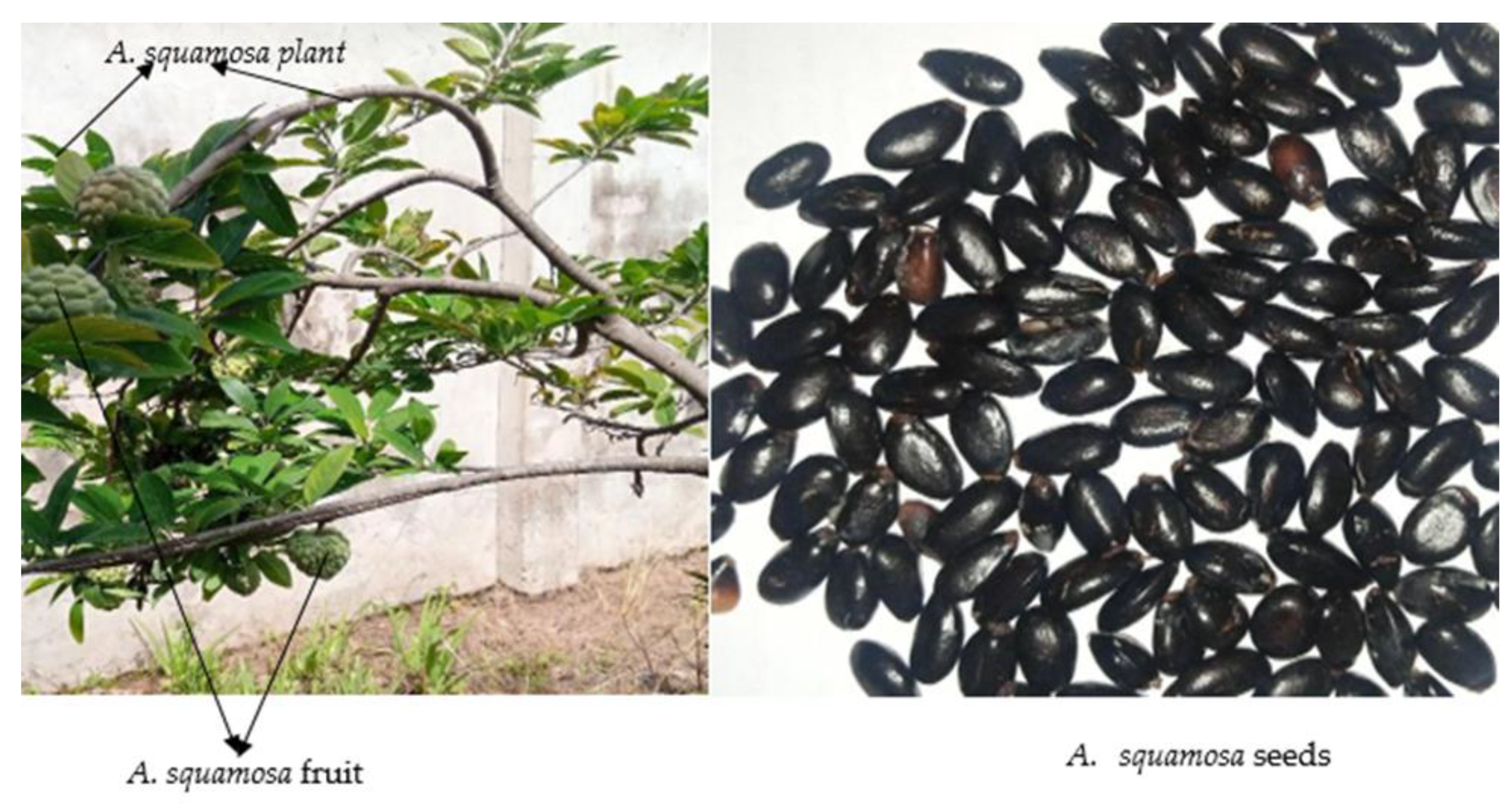

Annona squamosa (

A. squamosa), also known as custard apple or sweetsop is a tropical fruit commonly found in regions of Africa, Asia, and the Americas. The fruit is one of the families of

Annonaceae plant, genus

Annona, class

magnoliopsida and, species

Annona [

4].

A squamosa has different cultivars like pale-green, red and pink-bluish with similar characteristics [

5]. Moreover, the pale-green cultivar which is used in this study is commonly found in the tropical region of Africa and produces seeds rich in oil content (23-25% per 100g) [

6]. The prevailing fatty acids present in

squamosa seed oil are oleic with 49.75%, Linoleic, 22.50%, palmitic, 15.06%, and stearic, 4.63%. Thus, makes the seed oil suitable as potential feedstock for biodiesel synthesis [

5,

7]. Despite the potential of

A. squamosa seed oil to serve as valuable feedstock for biodiesel production, yet the seeds are often discarded as agricultural waste [

6].

In the field of machine design, the study of material properties and their behaviour under various compression loading conditions is crucial for ensuring optimal performance and durability [

8]. Agricultural biomaterials, such as seeds, offer a unique perspective due to their complex structure and mechanical responses. Mechanical compression is a widely employed method for extracting oil from seeds due to its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and eco-friendliness [

9]. The effectiveness of this process depends heavily on the mechanical properties of the seeds, such as hardness, deformation, and compressive strength [

10]. These properties are influenced by factors like seed moisture content and the speed of compression during the extraction process. Thus, understanding the compression loading behaviour of

A. squamosa seeds is of particular interest as it can provide insights into the seed structural integrity and potential applications in machine design for maximizing oil yield [

11,

12]. Furthermore, the loading speed applied to a material and the material moisture level during compression can greatly influence its mechanical response. The rate at which a force is applied can affect the deformation, stress distribution, and failure mechanisms of the material [

13]. To improve oil recovery efficiency of

A. squamosa seed in mechanical screw presses and expellers, it is important to deeply understand how the seed react to compression forces. This involves exploring how the applied force relates to the compression loading speed and moisture content of

A. squamosa seeds, which can be done using a universal compression testing machine [

10].

The mechanical properties of various oil seeds under compression loading in related to varying loading speeds or moisture contents have been studied by different researchers such as [

12] for Jatropha seeds, [

10] for Soursop seed and kernel, [

14] for

Moringa oleifera seeds, [

15] for paddy rice, [

16] for myrobalan seed,

[17] for plum kernel, [

8] for maize grain, and [

18] for mucuna bean, among others. However, information on the behaviour of

A. squamosa seeds under compression loading at varying compression loading speeds and moisture contents seems not to be available in literature. Therefore, the novelty of this study focuses on the compression loading behaviour of

A. squamosa seeds at varying speeds and moisture contents, aiming to analyze the seeds mechanical response during oil extraction. The findings will not only advance the understanding of

A. squamosa seed mechanics but also provide critical insights into designing efficient, sustainable, and scalable machinery for handling

A. squamosa seeds as potential feedstock for biodiesel production systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection and Preparation A. squamosa Seed

The

A. squamosa seeds (

Figure 1) used in this study were sourced from fruits harvested from plants growing in Ogbomoso North Local Government Area, situated at latitude 8.1335°N and longitude 4.2538°E. This region was selected due to its abundant

squamosa plant population. The seeds were manually separated from the white-pulp and rinsed to remove impurities and foreign materials. The seeds were then sun-dried to reduce their moisture content to a level suitable for storage.

2.2. Determination of Initial Moisture Content of A. squamosa Seeds

The initial moisture content of

Annona squamosa seeds on a dry basis (db) was determined following the American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers (ASABE) standard S352.2 (2001), as described by Adeyanju et al. [

19], and Oloyede et al. [

6]. The procedure utilized the oven-drying method with a laboratory oven (Model: DGH-9101, USA) set at a temperature of 103 ± 2°C. For the analysis, 5.0 g of seed samples (measured in triplicate) were weighed using a digital weighing balance (Model: MP 1001, with 0.1 g sensitivity) and placed in three separate aluminum cans. The cans, containing the seed samples, were then placed in the oven, and the weights of the samples were monitored at three-hour intervals till a constant weight was achieved. The average initial moisture content of the seed samples was calculated using Equation 1.

Where

= moisture Content (%, db),

= Mass of water (g),

= Mass of dry matter (g).

2.3. Conditioning of A. squamosa Seed Moisture Content

The moisture content of

A. squamosa seeds was adjusted to five predetermined levels (8.0–32.5% dry basis) using the rewetting method, as described by Mousaviraad and Tekeste [

20], and Hashemifesharaki [

21]. To achieve these moisture levels, a calculated amount of clean water was added to seed samples with known initial moisture content and weight. After adding the water, the samples were sealed in airtight bags, stowed in a refrigerator for at least seven days to ensure uniform moisture distribution thru the samples. Before testing, the essential quantity of the sample was removed from the refrigerator and allowed to equilibrate to room temperature. The amount of water to be added to the samples was calculated using Equation 2.

Where = Amount of water added (g), = sample’s Initial weight (g), = sample desired moisture level (%, db), and = sample’s initial moisture content (%, db).

2.4. Determination of Mechanical Properties of A. squamosa Seed

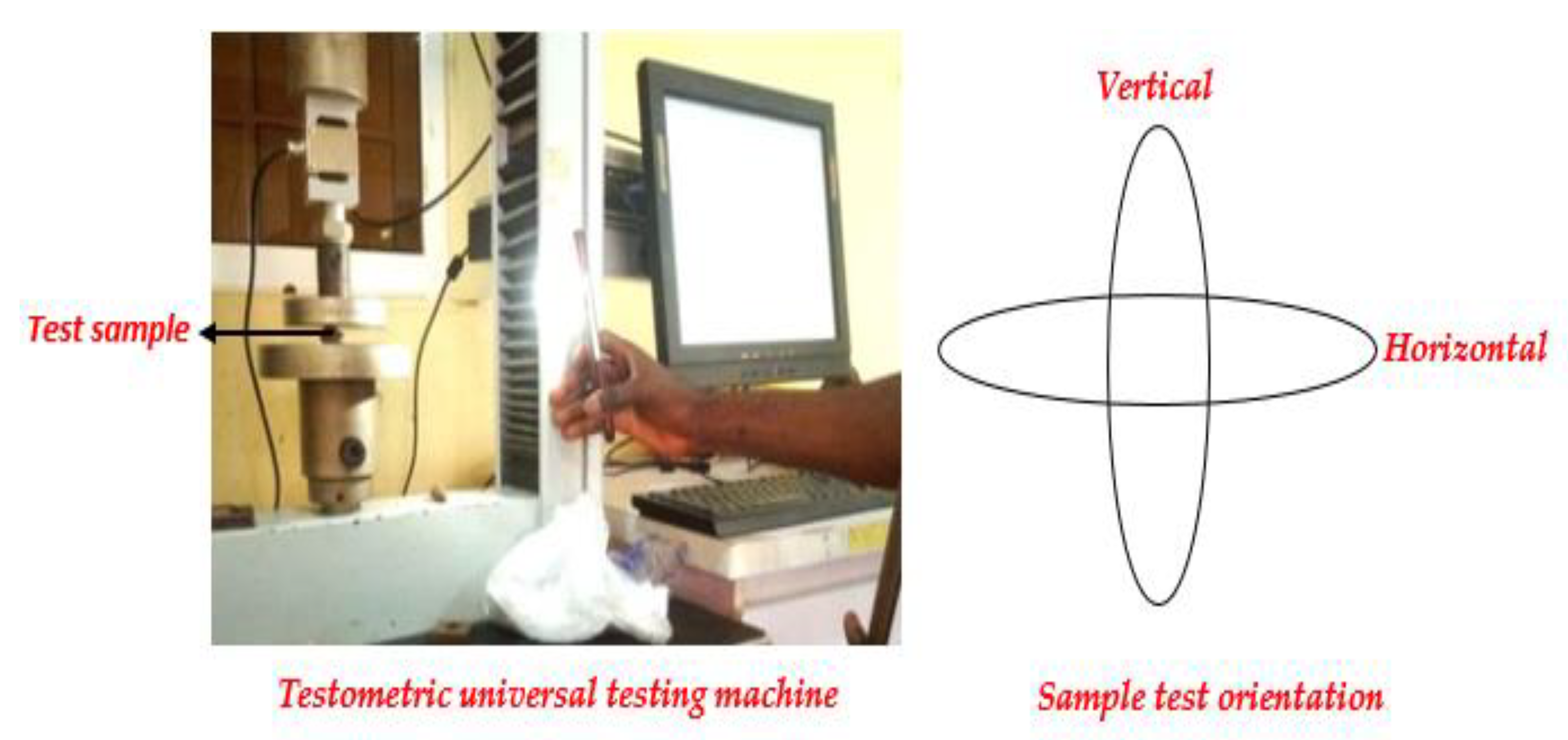

The mechanical properties of

A. squamosa seeds, under compression loading which include rupture force, rupture energy, bio-yield force, bio-yield energy, and deformation at the rupture point, were evaluated based on the forces acting on the two major orientations (horizontal and vertical) of the seeds. These parameters were measured at different compression loading speeds (5.0-25 mm/min) and moisture contents (8.0-32.5% db) following the recommendations of ASABE S368.4 (2013) for oilseeds, as outlined by Jan [

22] and Simbeye et al. [

23]. The tests were conducted using a Testometric material testing machine (

Figure 2), which has a measurement accuracy of 0.001 N for force and 0.001 mm for deformation. All testing was carried out at the Material Testing Laboratory of the National Centre for Agricultural Mechanization (NCAM) in Ilorin, Kwara State, Nigeria.

2.5. Determination of the Hardness A. squamosa Seed

The hardness of

A. squamosa seed was determined based on the ratio of rupture force to deformation at rupture point and calculated using Equation 3 [

17].

Where: H = hardness, Fr = rupture force, Rdp = deformation at rupture point.

2.6. Data Analysis

Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) in SPSS software (Version 21) was used to statistically examine the data gathered from the compressive tests. This was carried out in order to assess the noteworthy impacts that different loading rates and moisture concentrations had on the compressive characteristics of A. squamosa seeds. Duncan's Multiple Range Test (DMRT) was performed to compare the mean values of the compressive characteristics for the vertical and horizontal loading orientations. A probability level of was used to assess for the significance of the differences.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1 Moisture Content of A. squamosal Seed

The average initial moisture content of the

A. squamosal seed samples was obtained to be 8.0% (db) while the moisture levels obtained after conditioning the seed samples were 11.9, 15.4, 22.6 and 32.5% (db). Similar moisture variations have been used for

Annona muricata seed and kernel, a cultivar of

A squamosa, and reported by the authors, Oloyede et al. [

24], and Jaiyeoba et al. [

25], respectively.

3.2. Effect of Loading Speeds on Mechanical Properties of A. squamosa Seed Under Compression Loading Behaviour.

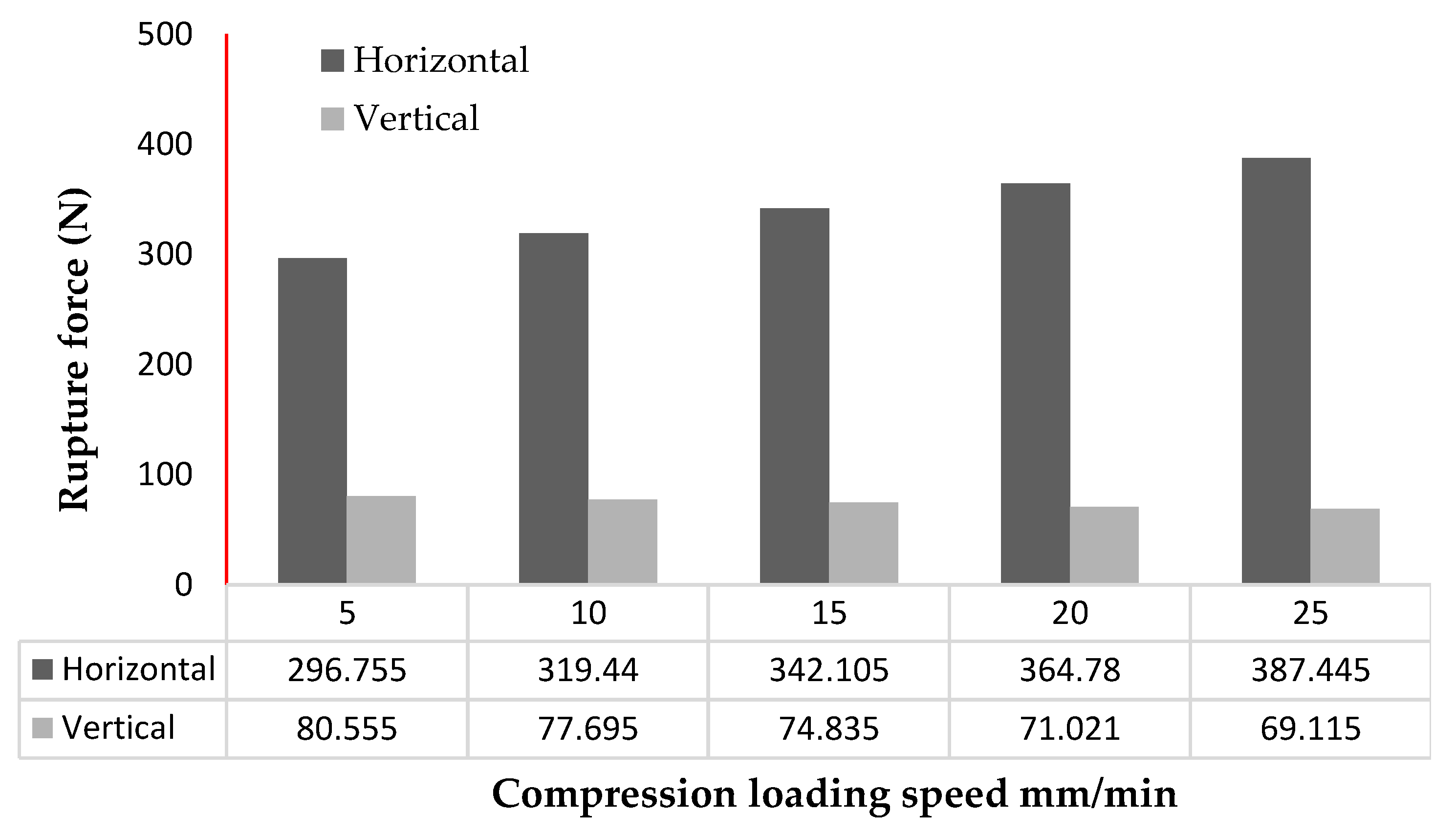

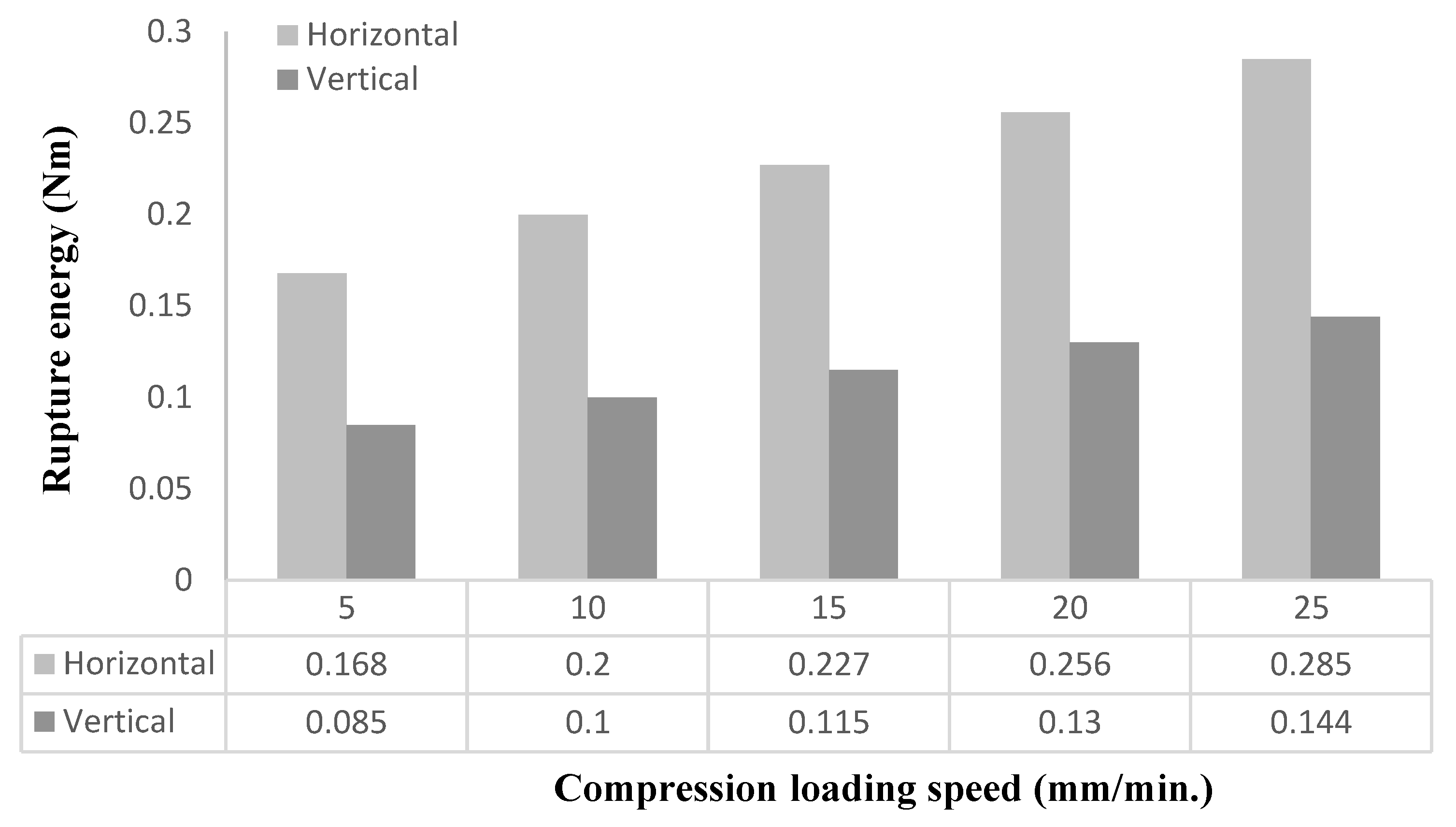

3.2.1. Effect of Loading Speeds on Rupture Force and Energy

The effect of varying loading speeds on mechanical properties of the seed under compression loading was examined at the seed moisture level of 8.0%, db. The horizontal and vertical rupture force and energy of

A. squamosa seeds at varying compression loading speeds (5.0-25.0 mm/min) at a safe storage moisture level of 8.0% (db) are presented in

Figure 3a,b. The results show that seed rupture force and energy significantly (

increased linearly with increasing compression loading speeds for both loading orientations, except for the rupture force at vertical loading orientation, which significantly (

) decreased linearly with increasing loading speeds (

Figure 3a). Similar behaviour was reported by Chandio [

8], and Etim [

18] for maize grains and mucuna beans, respectively. The seed rupture force and energy at horizontal loading orientation ranged from 295.86 to 386.11 N and 0.164 to 0.274 Nm, respectively (

Table 1). At vertical loading orientation, the rupture force ranged from 81.89 to 69.44 N, and the rupture energy from 0.0483 to 0.104 Nm at loading speeds of 5.0 to 25.0 mm/min. Lower rupture force and energy were observed at the seed vertical orientation. This behaviour can be attributed to the seed's structural anisotropy of

A squamosa seed [

17]. This observation was consistent with the findings of Zareiforoush [

26] for paddy grains and Hasseldine et al. [

27] for millet. These results indicate that less force is required to break

A. squamosa seeds in the vertical position compared to the horizontal position. ANOVA results (

Table 1) revealed significant F-values for rupture force (893.71 horizontal, 29.15 vertical) and rupture energy (43.49 horizontal, 13.99 vertical). The p-values

indicated that compression loading speeds have a significant effect on the seed rupture force and energy. Furthermore, Duncan's multiple range test (

Table 2) showed that vertical and horizontal rupture forces and energies mean values were significantly different (

) for all studied loading speeds. The linear regression models relating the loading speeds to the force and energy required to break the seed on its two major axes are shown in

Table 3. A strong positive correlation coefficient (

was obtained for both rupture force and energy at the two major orientations.

Figure 3a.

Effect of loading speeds on rupture force of A. squamosa seed.

Figure 3a.

Effect of loading speeds on rupture force of A. squamosa seed.

Figure 3b.

Effects of loading speeds on rupture energy of A. squamosa seed.

Figure 3b.

Effects of loading speeds on rupture energy of A. squamosa seed.

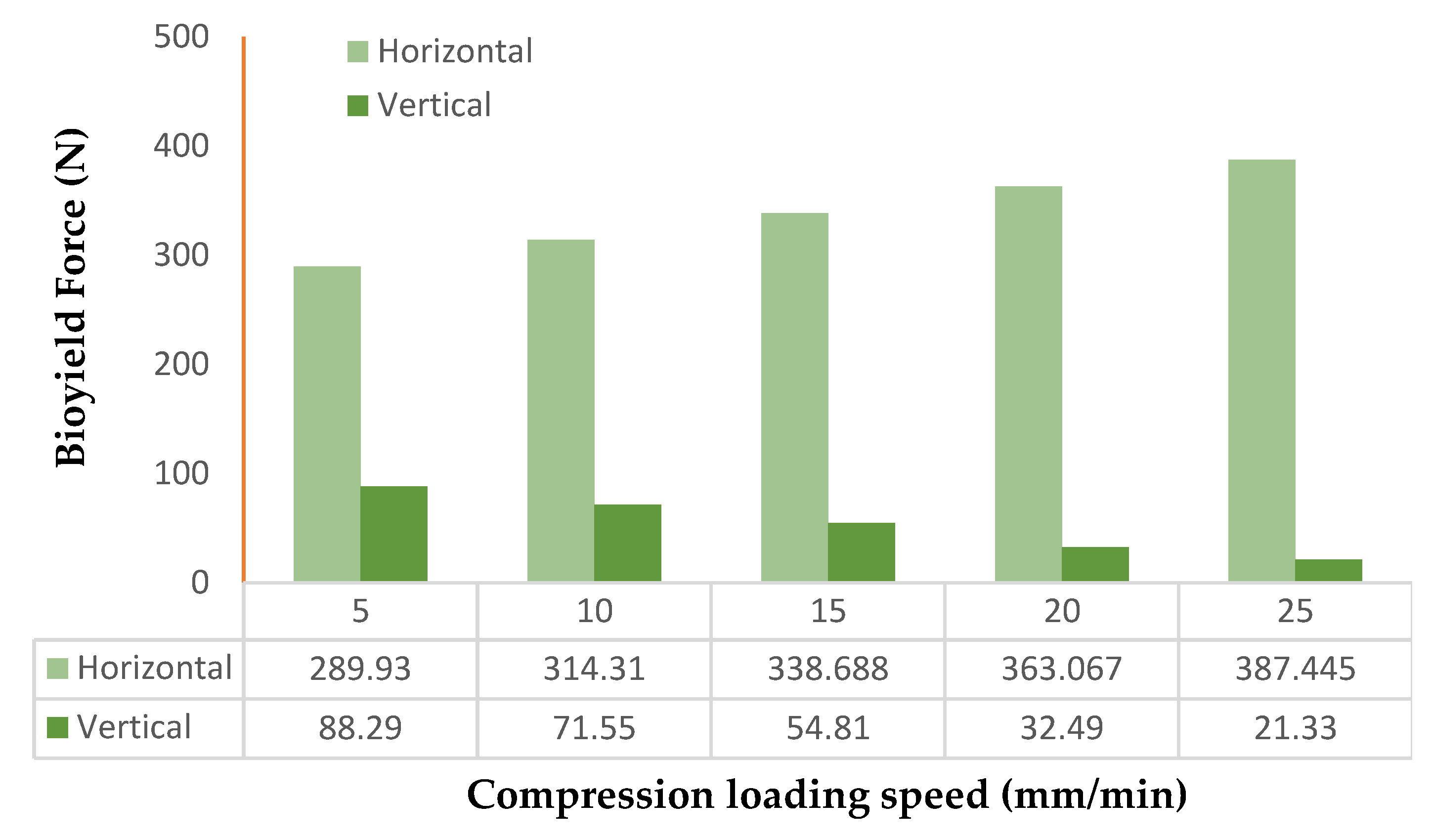

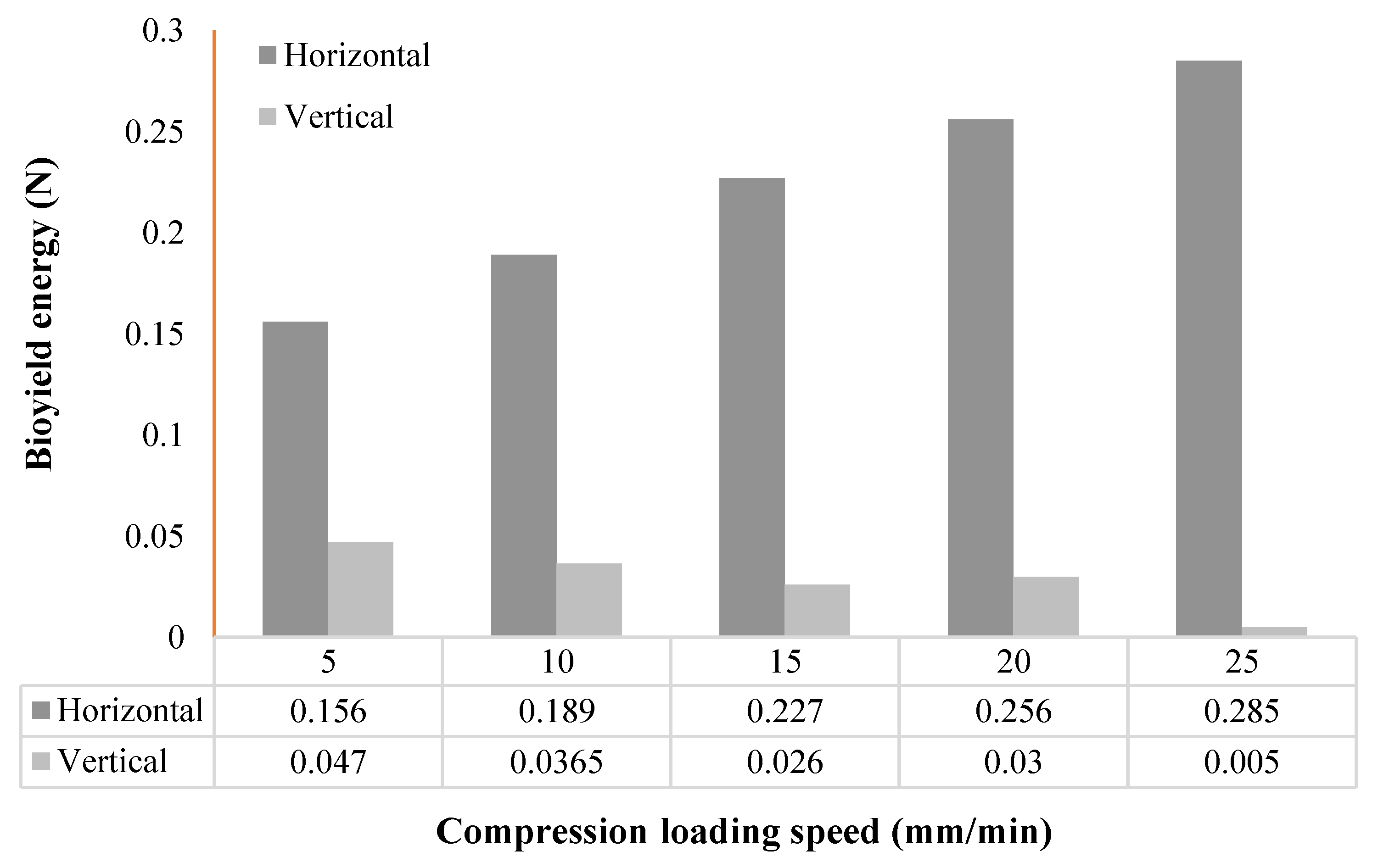

3.2.2. Effect of Loading Speeds on Bioyield Force and Energy

The interactions between compression loading speeds, bioyield force, and energy of

A. squamosa seed at vertical and horizontal orientations are presented in

Figure 4a,b, respectively. The data showed that the seed bioyield force and energy significantly (

) increased linearly at horizontal position but decreased linearly at vertical loading position with increasing speeds from 5.0 to 25.0 mm/min. The increase in bioyield force and energy at the seed horizontal orientation, contrasted by a decrease in the vertical orientation, can be attributed to the strain rate sensitivity of the seed [

28]. At horizontal orientation, the structural components of the seed may align in a manner that offers greater resistance to deformation thus, resulting in increased bioyield force and energy. However, in vertical orientation, the alignment of structural components may facilitate deformation under rapid loading, leading to decreased bioyield force and energy. These findings align with previous research on bioyield force and energy of pumpkin and sunflower seeds by Fadebiyi and Ozunde [

29], and Vasilachi et al. [

30], respectively. In horizontal orientation, the mean values for bioyield force and energy ranged from 289.93 to 387.445 N and 0.156 to 0.285 Nm, respectively. At vertical orientation, they ranged from88.29 to 21.33 N and 0.047 to 0.005 Nm (

Table 1) with increasing loading speed. The lower bioyield force and energy at the seed's vertical orientation can guide the design of agricultural processing machines to optimize seed oil extraction efficiency with reduced energy consumption [

12]. The ANOVA results (

Table 2) showed that the model term (loading speeds) had significant (

) effects on the bioyield force and energy of

A. squamosa seeds with significant F-values for bioyield force (712.47N horizontal, 723.840N vertical) and bioyield energy (56.68Nm horizontal, 22.75Nm vertical). Duncan's multiple range test (

Table 1) revealed that the mean values for bioyield forces and energies were significantly different (

) for all studied loading speeds, except at 5 and 20 mm/min at the seed vertical orientation for bioyield energy. The linear regression models relating the loading speeds with bioyield force and energy at the two orientations are shown in

Table 3. High positive

values were obtained for both bioyield force and energy at the two orientations. This trend aligns with previous findings for soursop seeds by Oniya [

10].

Figure 4a.

Effect of loading speed on bioyield force of A. squamosa seed.

Figure 4a.

Effect of loading speed on bioyield force of A. squamosa seed.

Figure 4b.

Effect of loading speed on bio-yield energy of A. squamosa seed.

Figure 4b.

Effect of loading speed on bio-yield energy of A. squamosa seed.

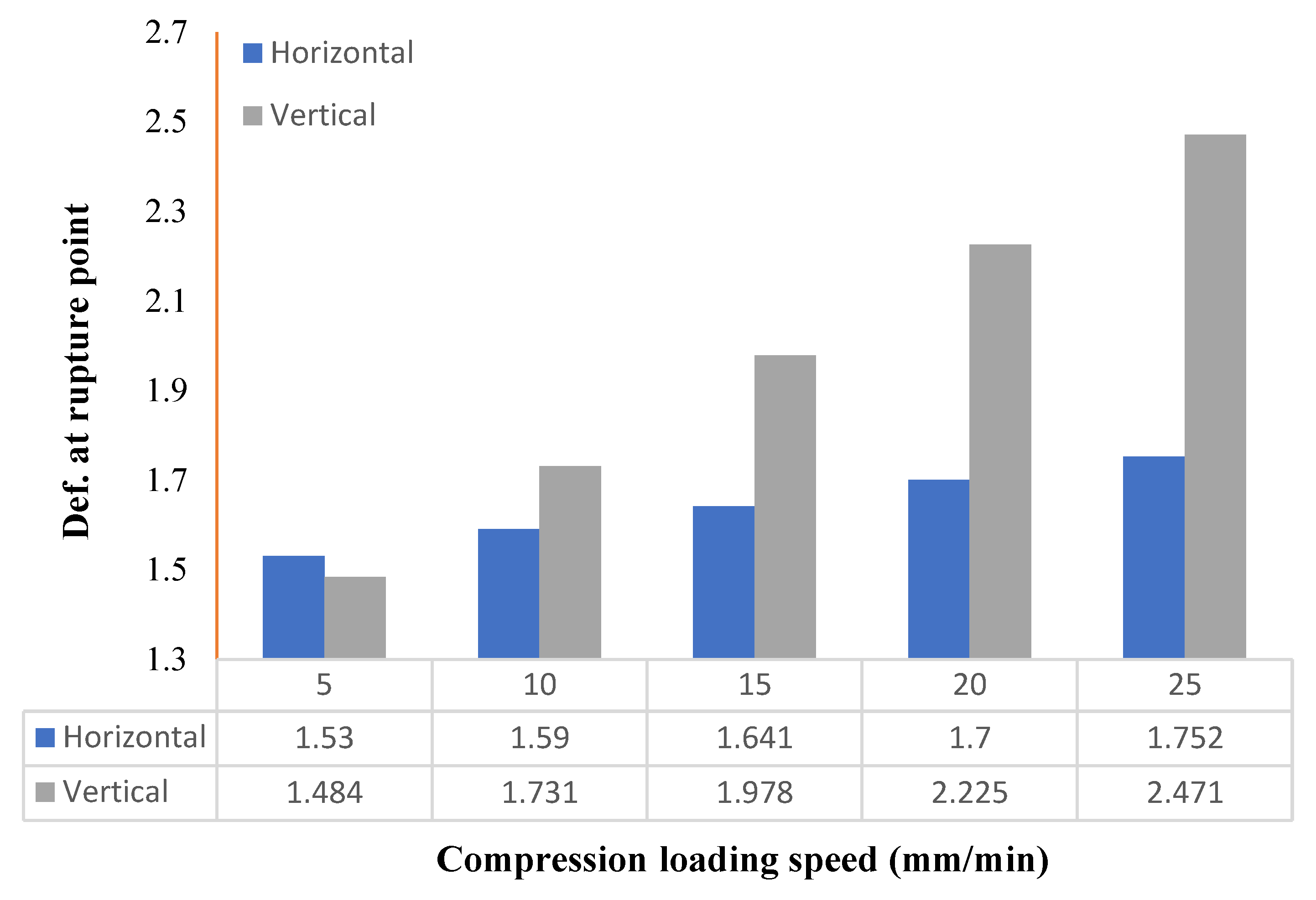

3.2.3. Effect of Loading Speed on Deformation at Rupture Point

The effect of loading speeds on deformation at rupture point (

of

A. squamosa seed is presented in

Figure 5. At the horizontal and vertical loading orientations, the seed deformation ranged from 0.164 to 0.274 mm, and from 1.574 to 2.51 mm, respectively as loading speeds increased from 5.0 to 25.0 mm/min. The results show that the deformation at rupture point of

A. squamosa seed significantly (

) increased linearly with loading speeds at both major loading orientations (

Figure 5). Higher values of deformation were observed at the seed vertical loading orientation compared to the horizontal orientation. This difference could be credited to the fact that in horizontal orientation, transverse loading causes an earlier failure because of structural buckling and load concentration, whereas the alignment of cells and vascular bundles along the vertical orientation offers greater resistance to axial compression [

8]. The highest deformation values were observed at loading speed of 25 mm/mm at both orientations, which implies that the high loading speed offers flexibility and elasticity to

A. squamosa seed during deformation. similar findings for deformation at rupture point were reported by Chandio [

8] for maize grains varieties. ANOVA results showed that loading speeds had a significant effect on deformation at rupture point of

A. squamosa seed with model F-values for of 1.36 (horizontal) and 67.43 (vertical) confirming the significance of the models. The linear regression model relating the loading speed and

with high positive

confirming a strong correlation between loading speed and

is shown in

Table 3.

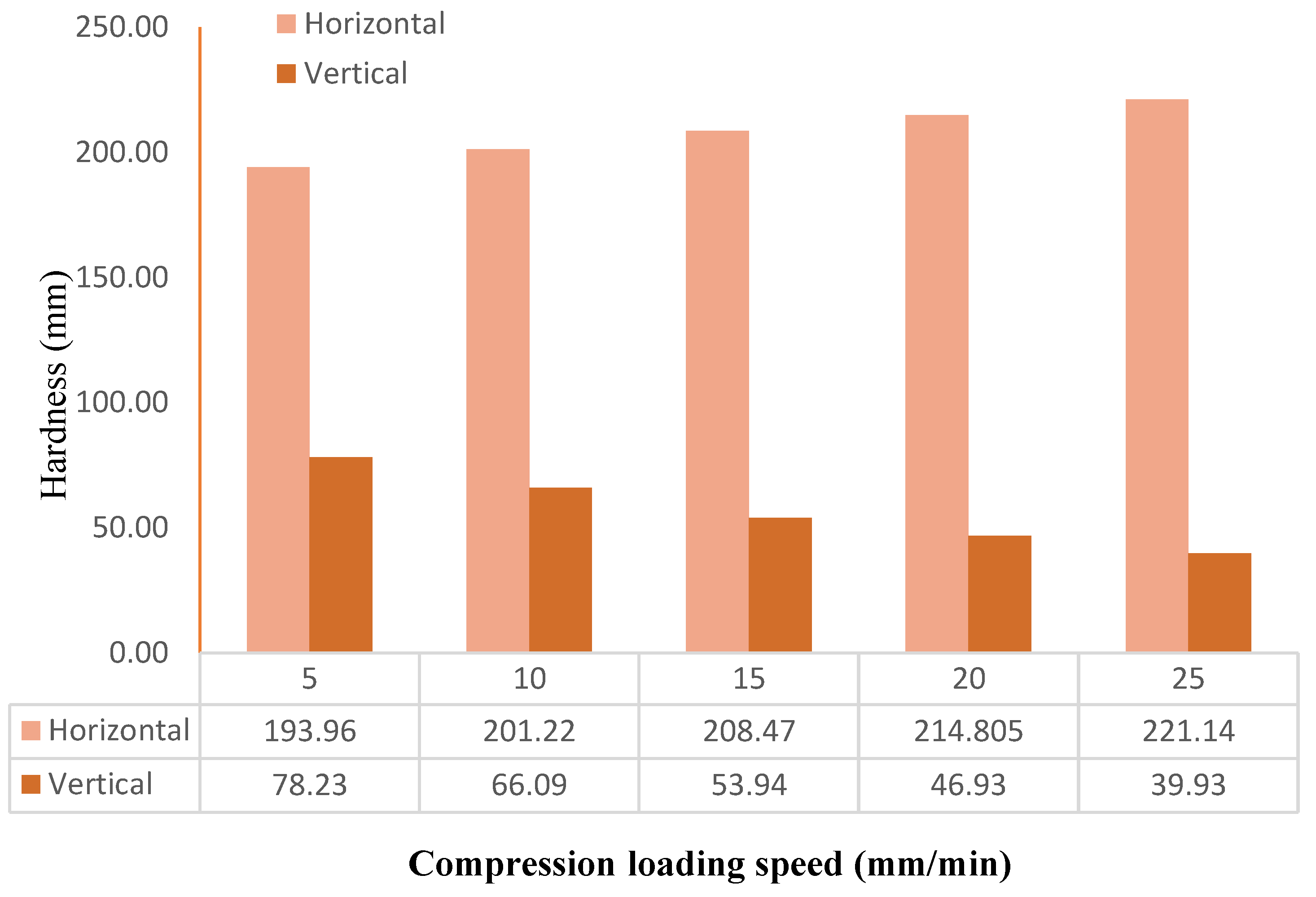

3.2.4. Effect of Loading Speed on Hardness of A. squamosal Seed

The mean value for the seed hardness at the horizontal loading orientation significantly (

) increased linearly from 193.96 to 221.14 N/mm, while it decreased linearly from 78.23 to 39.93 N/mm at the seed vertical loading position within the loading speed range of 5.0 to 25.0 mm/min (

Figure 6). At horizontal position, the seed hardness was consistently higher than at vertical loading position across all experimental loading speeds. This behaviour may be due to the loading position of the seed, which allowed easier fracture at vertical position compared to horizontal. The effect of loading speeds on the hardness was found to be significant (

) (

Table 3). More so, the mean values

A. squamosa seed hardness showed significant (

) differences at all experimental loading speeds (

Table 1). Similar result was reported by Chandio [

8] for maize grain whose grain hardness ranged from 711.06 to 381.65 N/mm for vertical hardness and 91.10 to 370.99 N/mm for lateral hardness. The linear regression model relating the loading speed and

A. squamosa seed hardness is presented in

Table 3. The high positive correlation coefficient (

confirmed a strong correlation between loading speed and the seed hardness.

Figure 5.

Effect of loading speed on deformation at rupture point of A. squamosa seed.

Figure 5.

Effect of loading speed on deformation at rupture point of A. squamosa seed.

3.3. Effect of Moisture Contents on Mechanical Properties of A. squamosa Seed Under Compression Loading

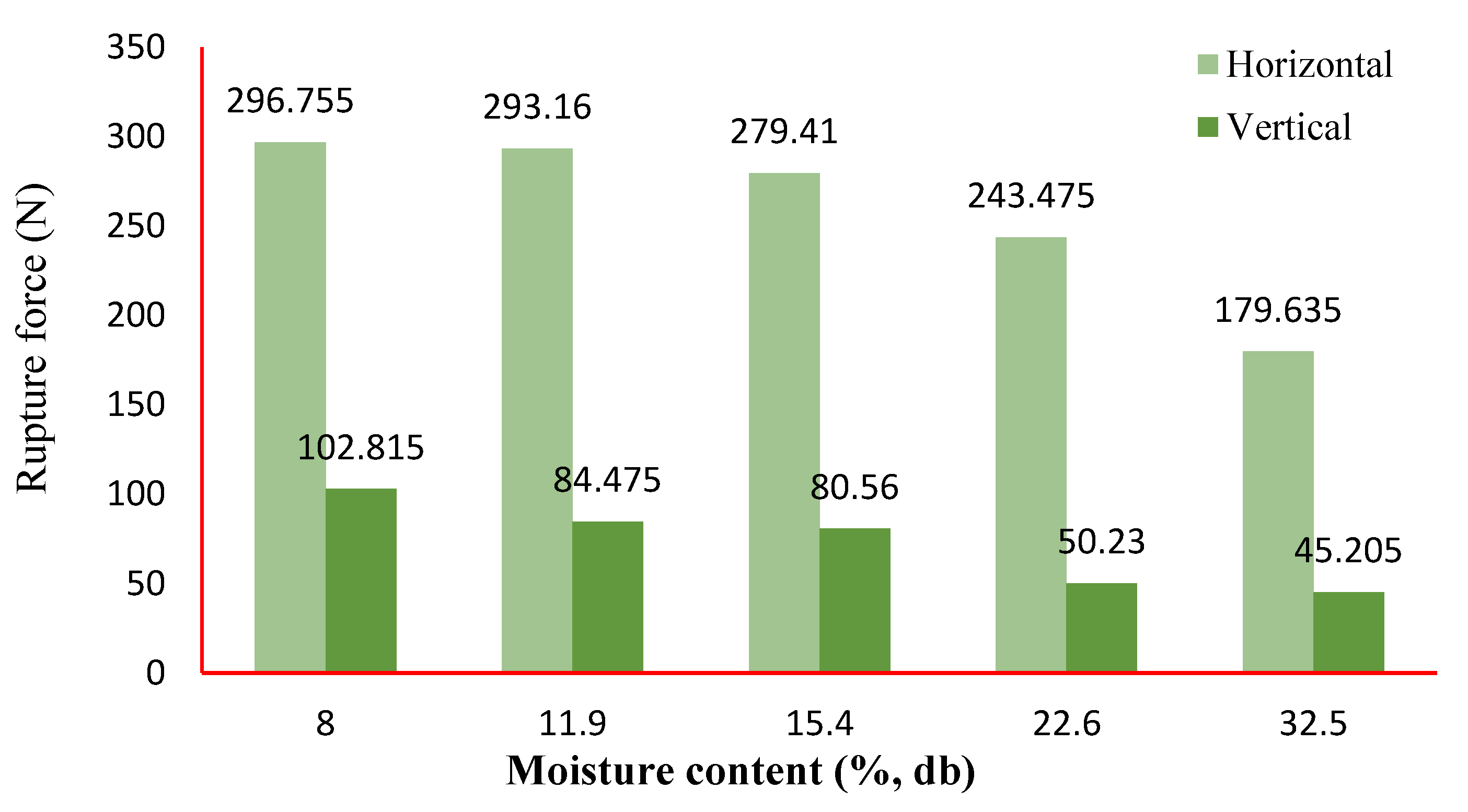

3.3.1. Effect of Moisture Content on the Seed’s Rupture Force and Energy

The correlation between the mean rupture force of

A. squamosa seed and moisture content along horizontal and vertical orientations is given in

Figure 7a and 7b, respectively. At all moisture levels, the horizontal position exhibited higher rupture force and energy compared to the vertical position of

A squamosa seed. The force needed to initiate rupture along the horizontal and vertical loading orientations ranged from 296.76 to 179.64 N, and 102.82 to 45.21 N, respectively with an increase in moisture content from 8.0 to 32.5% (db). The energy required to initiate force increased with moisture content from 0.168 to 0.285 Nm, and 0.055 to 0.105 Nm at horizontal and vertical orientations, respectively (

Figure 6b). These results indicate that

A. squamosa seed requires lower compression force to rupture in the vertical orientation compared to the horizontal orientation. This may be credited to the force being applied on the hilum portion of the seed in the vertical position, leading to easier rupture, and differences in the seed surface area [

10]. A similar range in rupture force and energy have been reported by Nyorere and Uguru [

31] for Beachwood seed. The interaction between the seed rupture force and moisture content in the horizontal position decreased significantly (

) and linearly with increasing moisture content (Figure6a), while it increased linearly in the vertical position. The reduction in rupture force with increasing moisture content in the horizontal orientation can be attributed to the seed becoming weaker at higher moisture content due to cellular structure modification through water absorption, thus requiring less force to break [

18]. Hence, the likely reason for higher rupture energy in the horizontal orientation. Similar trends have been reported for plum kernels by Aaqib [

17], and soursop seed by Oniya [

10]. The results for both major orientations (horizontal and vertical) were found to be statistically significant at

. The regression equations showing the relationship between moisture content, rupture force, and energy of

A. squamosa seed with strong positive

are presented in

Table 4. Understanding the mechanical behavior of the seed in relation to moisture content under applied forces is crucial for engineers and scientists. Therefore, when designing equipment for seed handling, both the orientation and moisture content of the seed should be given primary consideration.

Figure 7a.

Effects of moisture contents on rupture force of A. squamosa seed.

Figure 7a.

Effects of moisture contents on rupture force of A. squamosa seed.

Figure 7b.

Effects of moisture contents on rupture energy of A. squamosa seed.

Figure 7b.

Effects of moisture contents on rupture energy of A. squamosa seed.

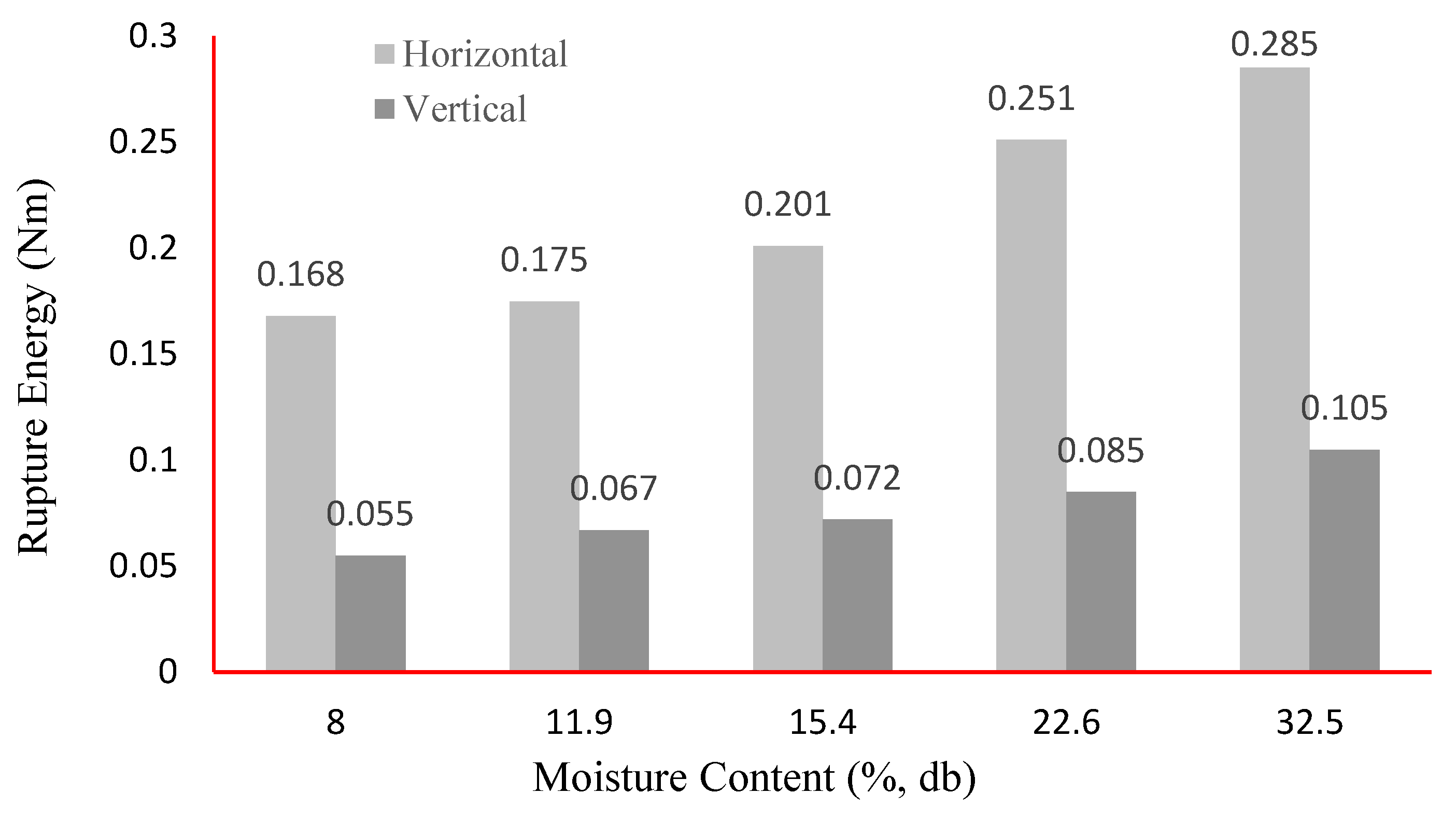

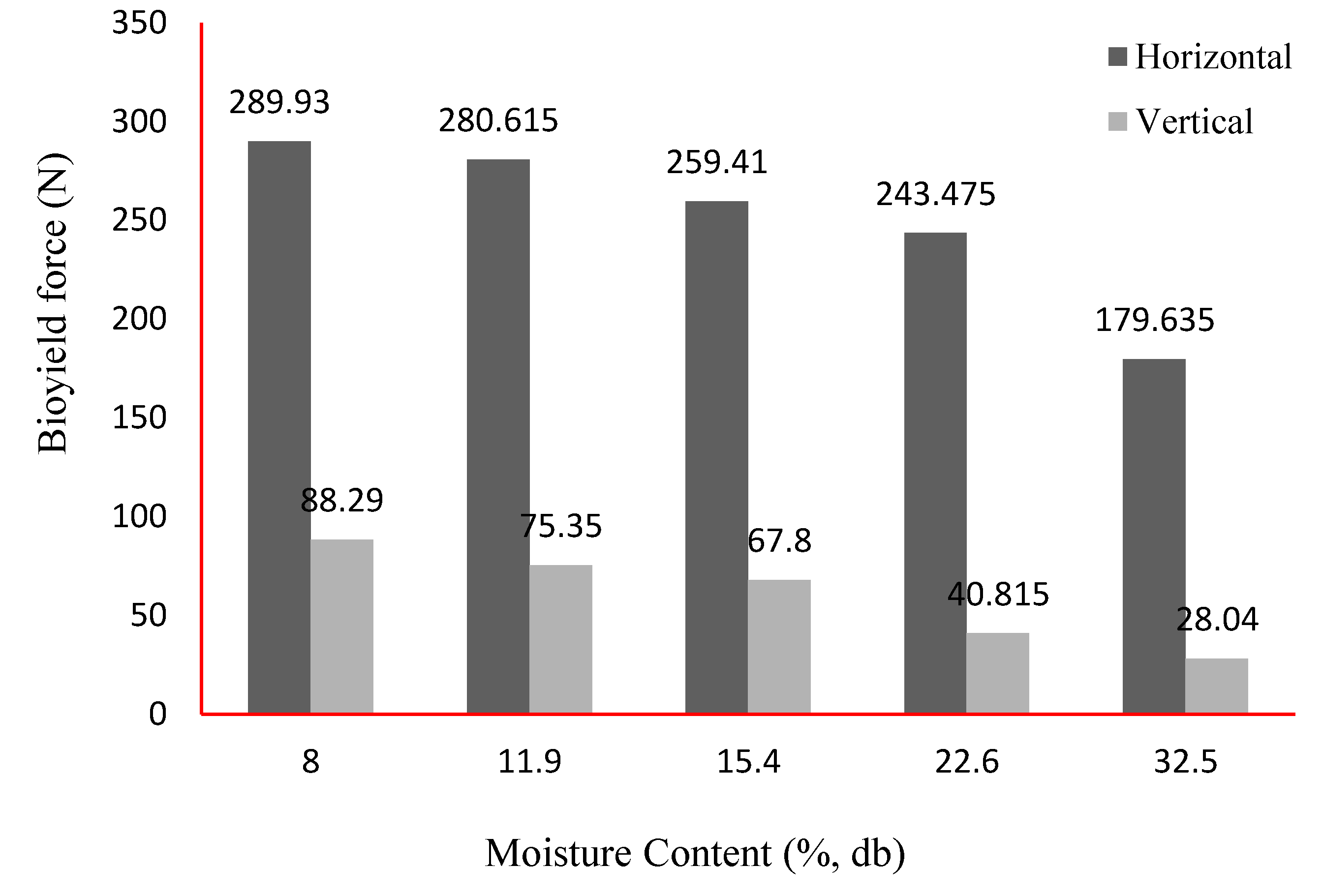

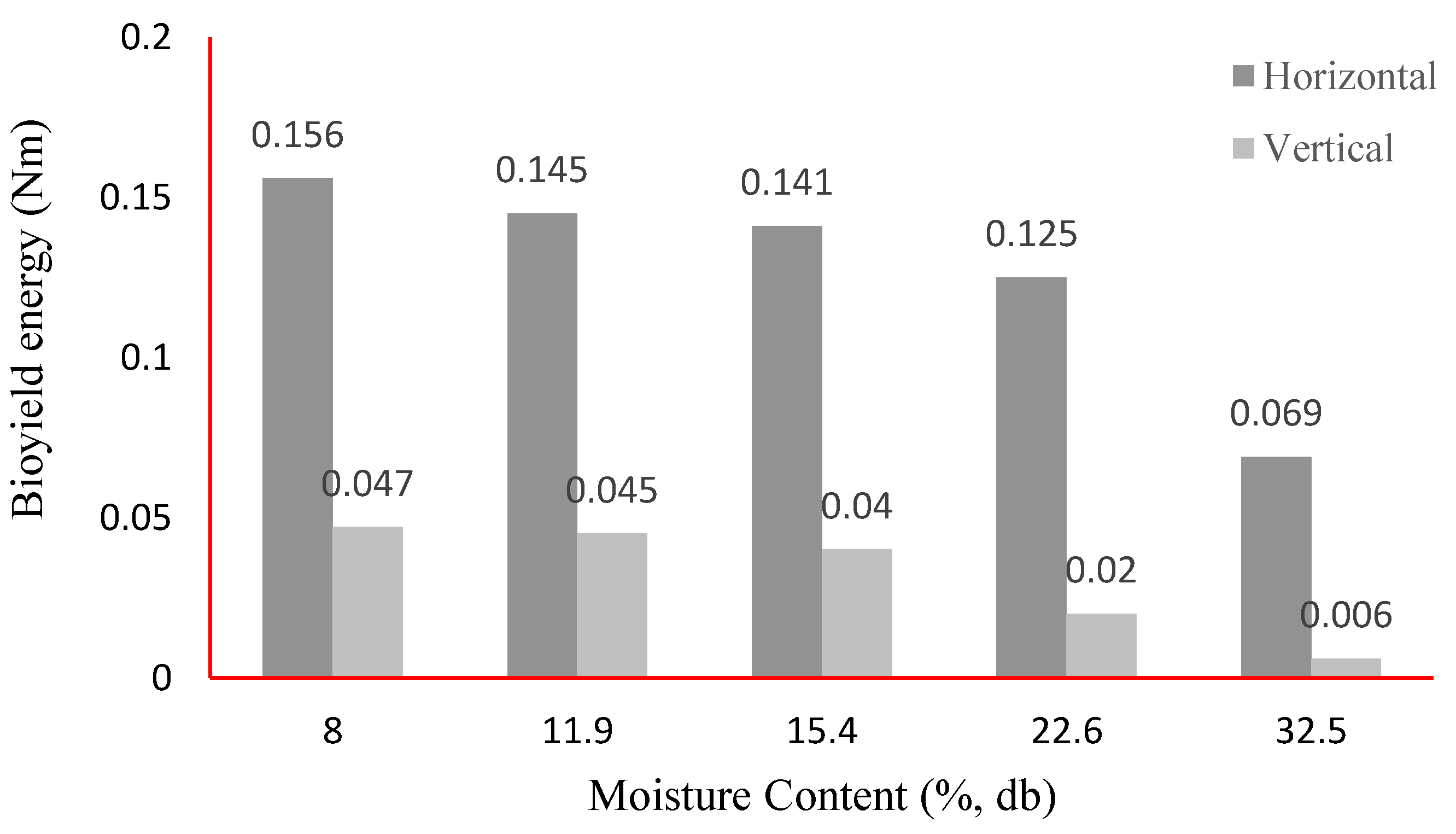

3.3.2. Effect of Moisture Content on Bioyield Force and Energy of A. squamosa Seed

The average bioyield force and energy of the seed in both horizontal and vertical loading orientations decreased linearly with increasing moisture content from 8.0 to 32.5% (

Figure 8a-b). In the horizontal position, the seed bioyield force and energy ranged from 289.93 to 179.64 N and 0.156 to 0.069 Nm, respectively. In the vertical orientation, these values ranged from 88.29 to 28.04 N and 0.047 to 0.006 Nm, respectively. The bioyield force in the horizontal orientation was consistently higher than in the vertical orientation. This suggests that structural alignment of

A. squamosa seed in the vertical loading position offers less resistance to applied force, possibly due to structural and mechanical anisotropies within the seed (Mohsenin 1986 in [

10]. Similar trends were detailed by Chandio [

8] maize grain. The relationship between seed moisture content, bioyield force, and energy was found to be significant at

for both loading orientations (

Table 5). The mean values for the horizontal bioyield force and energy of the seed showed no significant difference (

) except at moisture levels of 8.0, 22.6, and 32.5%. In the vertical loading orientation, no significant difference was observed between the mean values of bioyield force and energy across all moisture levels except at 8.0 and 22.4% (db). These trends align with findings reported for soursop seeds by Oniya et al. [

10] High correlation coefficients

indicate strong relationship between seed moisture contents, bio-yield force, and energy.

Figure 8a.

Effect of moisture content on bio-yield force of A. squamosa seed.

Figure 8a.

Effect of moisture content on bio-yield force of A. squamosa seed.

Figure 8b.

Effect of moisture content on bioyield energy of A. squamosa seed.

Figure 8b.

Effect of moisture content on bioyield energy of A. squamosa seed.

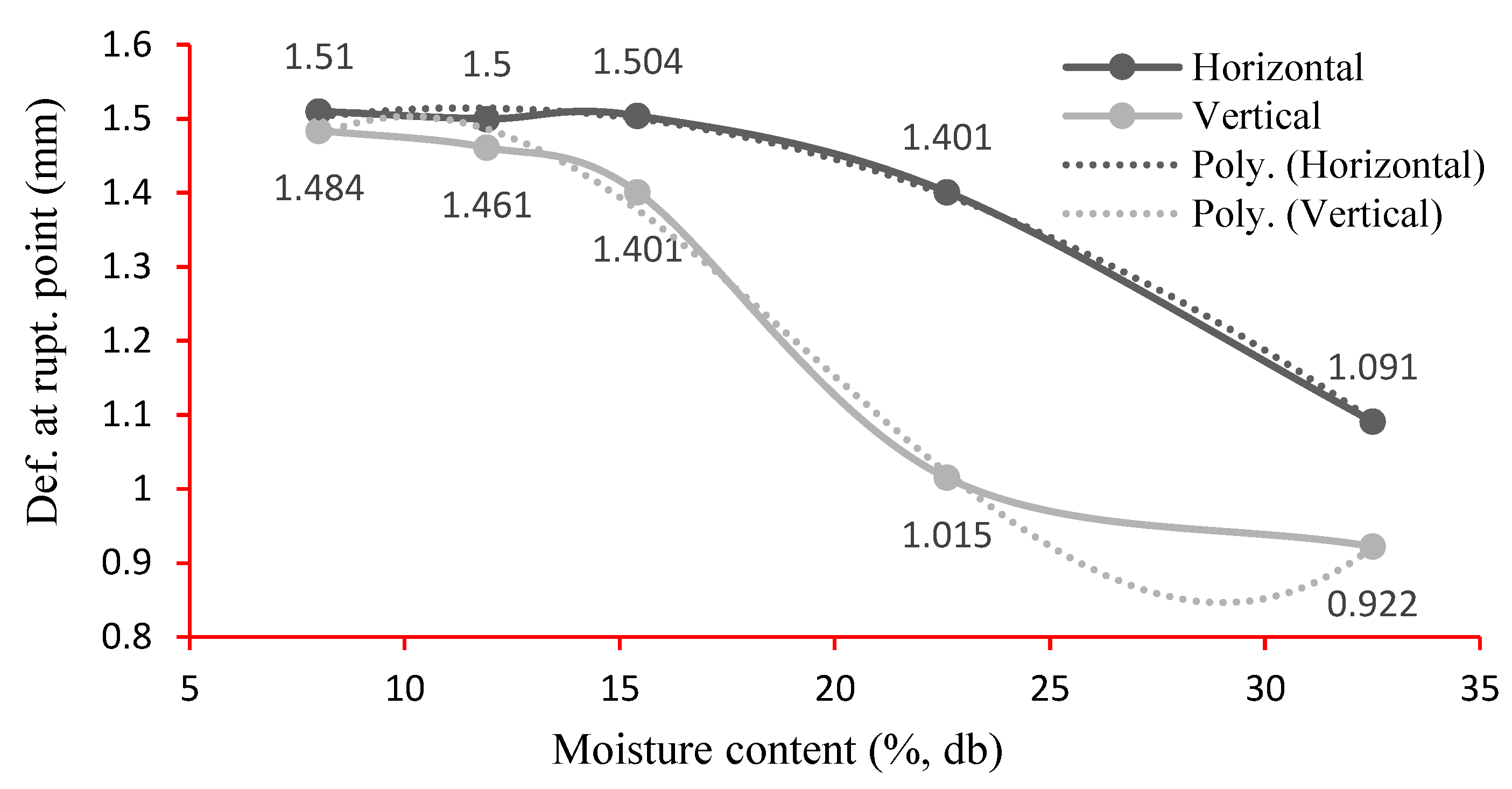

3.3.3. Effect of Moisture Content on Deformation at Rupture Point

The mean values of deformation at rupture point for compression via horizontal and vertical loading orientations of

A. squamosa seed at five moisture contents are presented in

Figure 9. At the rupture point, seed deformation decreased non-linearly (with second-order and third-order polynomial relationships in horizontal and vertical orientations, respectively) as moisture content increased from 8.0 to 32.5%. This indicates that the rate of decline was more pronounced at lower moisture levels for both loading orientations. The deformation at rupture point of

A. squamosa seed compressed along the horizontal orientation was higher at all moisture levels, suggesting that the seed is more resistant and flexible to compression in this orientation. In both orientations, lower moisture contents resulted in more mechanical damage, a trend also reported by Aaqib et al. [

17] for plum kernels. The average values for deformation at rupture point ranged from 1.51 to 0.91 mm and 1.48 to 0.49 mm for horizontal and vertical loading orientations, respectively. Along both orientations, statistical analysis revealed that deformation at rupture point varied significantly (

) with changing moisture content (

Table 5). Strong positive correlation coefficients (

described by the regression equations in

Table 6 indicate a robust relationship between seed moisture content and deformation at rupture point. According to DMRT, the mean differences across moisture content levels were not statistically significant (

) for either orientation, except between 22.6 and 32.5% (horizontal), and 15.4 and 32.5% (vertical) moisture levels. This suggests that moisture content changes within these ranges have a notable impact on deformation at rupture point. Similar trends were reported by Lupu et al. (2016) and Chandio et al. [

8] for wheat and maize grains, respectively.

Figure 9.

Effect of moisture content on deformation at rupture point of A. squamosa seed.

Figure 9.

Effect of moisture content on deformation at rupture point of A. squamosa seed.

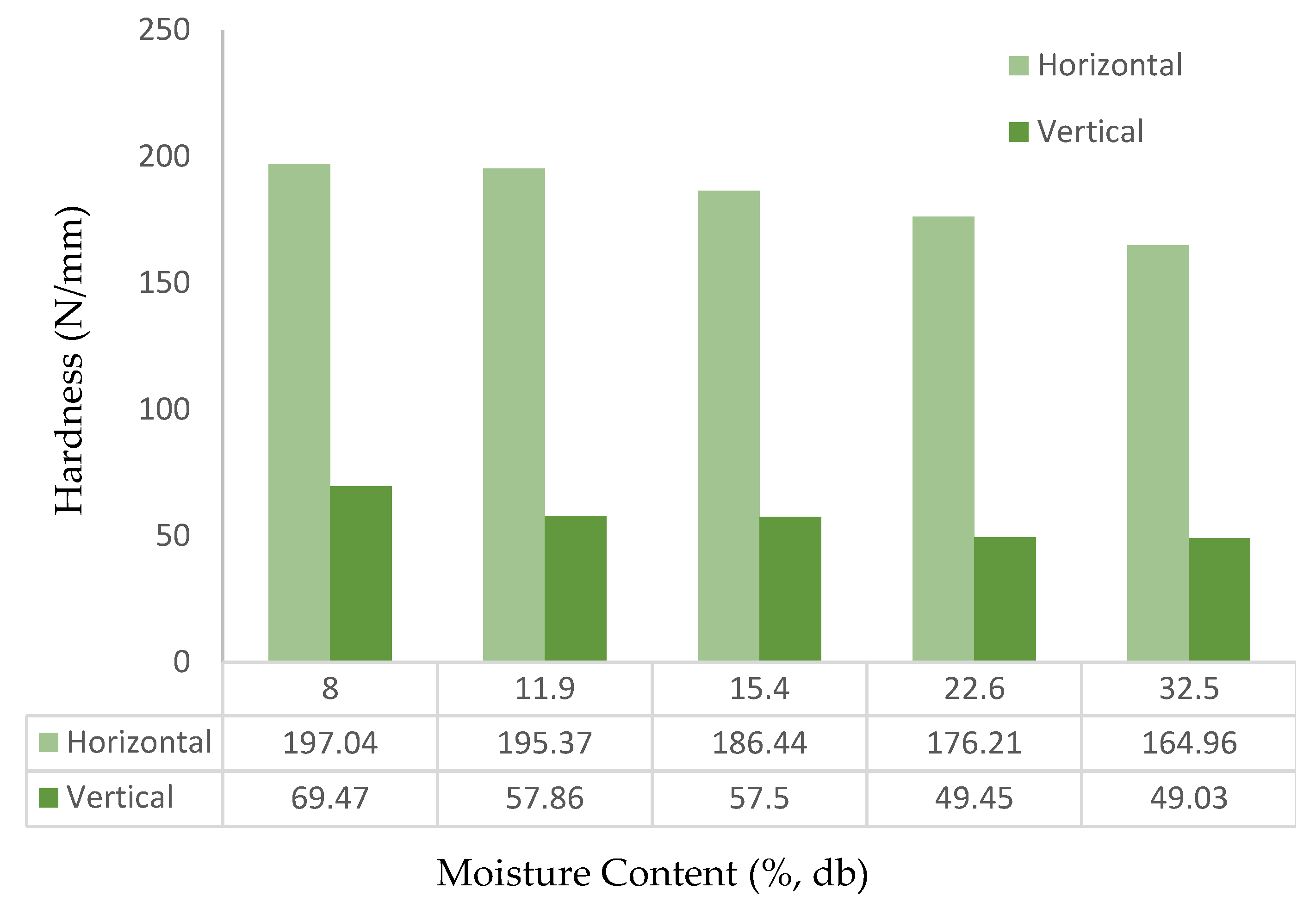

3.3.4. Effect of Moisture Content on A. squamosa Seed Hardness

The hardness of

A. squamosa seeds exhibited a clear inverse relationship with moisture content, decreasing as moisture contents increased from 8.0% to 32.5% in both horizontal and vertical orientations (

Figure 10). The average values for seed hardness ranged from 197.04 to 164.96 N/mm and 69.47 to 49.03 N/mm in the horizontal and vertical orientations, respectively. This reduction in hardness can be attributed to moisture-induced softening of the seed structure, which diminishes its resistance to compressive forces (Oyerere and Uguru, 2018). Similar patterns have been reported for other biomaterials, including plum kernels [

17], maize grain varieties [

8], and paddy grains [

26]. The seed hardness in the horizontal orientation was higher at all moisture levels compared to the vertical orientation. This can be credited to the force application in the horizontal position encountering multiple tissue layers perpendicular to their natural orientation, thus, resulting in greater compression resistance [

28]. Statistical analysis confirmed that moisture content significantly (

) influenced seed hardness (

Table 6). Additionally, DMRT analysis showed significant differences (

) in seed hardness at all experimental moisture levels for both orientations (

Table 5). Understanding this relationship between hardness and moisture content is crucial for optimizing processing operations and improving energy efficiency in

A. squamosa seed handling systems. A high positive correlation coefficient confirmed a strong relationship between moisture content and hardness of the seed. Engineers should consider seed hardness data when selecting materials for the design of processing machinery for

A. squamosa seeds to ensure equipment can withstand potential abrasion without excessive wear.

Figure 10.

Effect of moisture content on hardness of A. squamosa seed.

Figure 10.

Effect of moisture content on hardness of A. squamosa seed.

5. Conclusions

This study examined the mechanical behaviour of Annona squamosa seed under compression loading at different compression loading speeds (5.0-25.0 mm/min) and moisture content (8.0-32.5%, db) for sustainable biodiesel synthesis. Based on the experimental results, the following conclusions were drawn:

The effect of loading speeds and moisture contents on the rupture force, rupture energy, bioyield force, bioyield energy, deformation at rupture point and hardness was significant at level of ANOVA for the horizontal and vertical orientations.

The differences between the mean data of rupture force and energy, bioyield force, and energy, deformation at rupture point and hardness of the seed at all experimental loading speeds and moisture contents for the two loading orientations were found to be statistically significant (, except between 22.6 and 32.5% (horizontal), and 15.4 and 32.5% (vertical) moisture levels.

The correlations between loading speeds, moisture contents and the parameters under compressive loading behaviour of A. squamosa seeds were mostly linear except for deformation (horizontal and vertical), and hardness (vertical) which were polynomial with moisture contents only.

The coefficient of correlation ( for the developed regression models, was high for the loading speed and moisture contents of the seed.

Therefore, grasping the impact of loading speeds and moisture content on the mechanical behavior of A. squamosa seeds is essential for tailoring equipment to improve oil recovery efficiency in mechanical screw presses and expellers. Hence, this research offers important insights for the biodiesel feedstock processing sector, aiding in the design of machinery that can effectively manage A. squamosa seeds, thereby assuring consistent and high-quality oil extraction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, CTO and JSO.; methodology, CTO, JSO, OI.; software, CTO and OI.; validation, CTO., JSO. and CCE.; formal analysis, CTO.; investigation, CTO and OI.; resources, CTO.; JSO, CCE and OI.; data curation, CTO, JSO and OI.; writing—original draft preparation, CTO and OI.; writing—review and editing, CTO and OI.; visualization, JSO and CCE.; supervision, CTO and JSO.; project administration, CTO and JSO.; funding acquisition, CTO, JSO, OI and CCE. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DB |

Dry basis |

| MC |

Moisture content |

| ASABE |

Americal Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers |

| ANOVA |

Analysis of Variance |

| SPSS |

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| DMRT |

Duncan’s Multiple Range Test |

References

- Oladipo, B.; Betiku, E. Optimization and kinetic studies on conversion of rubber seed (Hevea brasiliensis) oil to methyl esters over a green biowaste catalyst. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 268, 110705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oloyede, C.T.; Jekayinfa, S.O.; Alade, A.O.; Ogunkunle, O.; Otung, N.U.; Laseinde, O.T. Exploration of agricultural residue ash as a solid green heterogeneous base catalyst for biodiesel production. Eng. Rep. 2022, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betiku, E.; Okeleye, A.A.; Ishola, N.B.; Osunleke, A.S.; Ojumu, T.V. Development of a Novel Mesoporous Biocatalyst Derived from Kola Nut Pod Husk for Conversion of Kariya Seed Oil to Methyl Esters: A Case of Synthesis, Modeling and Optimization Studies. Catal. Lett. 2019, 149, 1772–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safira, A.; Widayani, P.; An-Najaaty, D.; Rani, C.A.M.; Septiani, M.; Putra, Y.A.S.; Solikhah, T.I.; Khairullah, A.R.; Raharjo, H.M. A Review of an Important Plants: Annona squamosa Leaf. Pharmacogn. J. 2022, 14, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshra, D.H.; Shehata, A.R.; Ahmed, A.-N.A.; Saber, J.I. Physicochemical Properties of the Seed Kernels and the Oil of Custard Apple (Annona squamosa L.). Int. J. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2019, 4, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oloyede, C.T.; Jekayinfa, S.O.; Adebonojo, S.A.; Uduaghan, A.A.; Adebayo, J.M.; Rizwanul, F.I.M. Moisture-modulated thermo-physical analysis of sweetsop seed (Annona squamosa L.): A potential biofuel feedstock plant. J. Food Process. Eng. 2024, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. R. Hotti and O. D. Hebbal, “from Sugar Apple Seed Oil ( Annona squamosa ) and Its Characterization,” vol. 2015, 2015.

- Chandio, F.A.; Li, Y.; Ma, Z.; Ahmad, F.; Syed, T.N.; Shaikh, S.A.; Tunio, M.H. Influences of moisture content and compressive loading speed on the mechanical properties of maize grain orientations. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2021, 14, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwe, D.N.; Umani, K.C.; Olosunde, W.A.; Ossom, I.S. Comparative analysis of moisture-dependent physical and mechanical properties of two varieties of African star apple (Chrysophyllum albidum) seeds relevant in engineering design. Sci. Afr. 2020, 8, e00303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oniya, O.; Oloyede, C.; Akande, F.; Adebayo, A.; Onifade, T. Some Mechanical Properties of Soursop Seeds and Kernels at Different Moisture Contents under Compressive Loading. Res. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. ` 2016, 12, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chandio, F.A.; Ma, Z.; Lakhiar, I.A.; Sahito, A.R.; Ahmad, F.; Mari, I.A.; Farooq, U.; Suleman, M. Mechanical strength of wheat grain varieties influenced by moisture content and loading rate. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2018, 11, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabutey, A.; Herák, D.; Chotěborský, R.; Sigalingging, R.; Mizera, Č. Effect of compression speed on energy requirement and oil yield of Jatropha curcas L. bulk seeds under linear compression. Biosyst. Eng. 2015, 136, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzabe, A.H.; Hajiahmad, A.; Asadollahzadeh, A.H. Moisture-dependent engineering properties of arugula seed relevant in mechanical processing and bulk handling. J. Food Process. Eng. 2021, 44, e13704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. M. A. Olayanju et al., “Mechanical behaviour of Moringa oleifera seeds under compression loading,”. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Technol. 2018, 9, 848–859.

- Y. Li, F. Ali, Z. Ma, M. Zaman, and B. Li, “Post harvesting technology : effects of moisture content and loading speed on shearing failure of paddy grains,”. Int. Agric. Eng. J. 2018, 27, 342–249.

- Pathak, S.S.; Sonawane, A.; Pradhan, R.C.; Mishra, S. Effect of Moisture and Axes Orientation on the Mechanical Properties of the Myrobalan Fruits and its Seed Under Compressive Loading. J. Inst. Eng. (India): Ser. A 2020, 101, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, M.A.; Saini, C.S.; Sharma, H.K. Computation of design-related engineering properties and fracture resistance of plum (Prunus domestica) kernels to compressive loading. J. Agric. Food Res. 2021, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. J. Etim, A. F. Alonge, and G. E. Akpan, “Effect of moisture content on some mechanical and frictional properties of mucuna bean ( mucuna crens ) relevant to its cracking,”. Agric. Eng. Int. CIGR J. 2021, 23, 265–273.

- J. A. Adeyanju, A. O. Abioye, A. A. Adekunle, A. A. Olokoshe, T. H. Ibrahim, and A. L. Faboade, “Investigation on the Effect of Moisture Content on Physical and Thermal Properties of Ofada Rice ( Oryza Sativa L .) Relevant To Post-Harvest Handling,”. 2021, 15, 108–116.

- Mousaviraad, M.; Tekeste, M.Z. Effect of grain moisture content on physical, mechanical, and bulk dynamic behaviour of maize. Biosyst. Eng. 2020, 195, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Hashemifesharaki, “Moisture-Dependent Engineering Characterization of Psyllium Seeds : Physical , Frictional , Aerodynamic , Mechanical , and Thermal Properties,”. Biosyst. Eng. 2021, 45, 374–384.

- Jan, K.N.; Panesar, P.S.; Singh, S. Effect of moisture content on the physical and mechanical properties of quinoa seeds. Int. Agrophys. 2019, 33, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D. S. Simbeye, “RESEARCH ORGANISATION| Computerized Measurement and Control System of the Universal Testing Machine Based On Virtual Instruments,” J. Inf. Sci. Comput. Technol., vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 456–465, 2016, [Online]. Available: www.scitecresearch.

- C. T. Oloyede, F. B. Akande, and O. O. Oniya, “Moisture dependent physical properties of sour-sop (Annona muricataL.) seeds,”. Agric. Eng. Int. CIGR J. 2015, 17, 185–190.

- K. . Jaiyeoba et al., “Exploring Soursop Kernel as a Sustainable Biofuel : Analyzing Physical and Solid Flow Properties for Feasibility Assessment,”. LAUTECH J. Eng. Technol. 2022, 16, 190–199.

- Zareiforoush, H.; Komarizadeh, M.; Alizadeh, M.; Tavakoli, H.; Masoumi, M. Effects of Moisture Content, Loading Rate, and Grain Orientation on Fracture Resistance of Paddy (Oryza SativaL.) Grain. Int. J. Food Prop. 2012, 15, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasseldine, B.P.; Gao, C.; Collins, J.M.; Jung, H.-D.; Jang, T.-S.; Song, J.; Li, Y. Mechanical response of common millet (Panicum miliaceum) seeds under quasi-static compression: Experiments and modeling. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2017, 73, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shashikumar, C.; Pradhan, R.C.; Mishra, S. Influence of Moisture Content and Compression Axis on Physico-mechanical Properties of Shorea robusta Seeds. J. Inst. Eng. (India): Ser. A 2018, 99, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Fadeyibi and Z. D. Osunde, “Mechanical Behaviour of Rubber Seed under Compressive Loading,”. Curr. Trends Technol. Sci. 2012, 1, 2279–535.

- (Baltăţu), C.V.; Biriş, S.; Gheorghe, G. Study of the compression behaviour of grape seeds using the Finite Element Method. E3S Web Conf. 2020, 180, 128–136. [Google Scholar]

- O. Nyorere and H. Uguru, “Full-text Available Online at Effect of Loading Rate and Moisture Content on the Fracture Resistance of Beechwood ( Gmelina arborea ) Seed. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manag. 2018, 22, 1609–1613. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).