1. Introduction

The Bardeen–Cooper–Schrieffer (BCS) theory of superconductivity in the late 1950 is an extremely successful paradigm within which to understand conventional superconductors. The basic physics is that the electrons collectively bind into Cooper pairs (as bosons) and simultaneously condense into a superfluid state. The relatively weak

net attractions between electrons induced by the coupling to the excitations of the lattice structure (phonons) can bind the electrons into pairs at energies smaller than the typical phonon energy. The consensus among theoretical physicists [

1] seems to be that boson-excitation mediated pairing of electrons is limited to around 30 K or a little above, to 39 K by applying pressure to increase the typical phonon energies. However, this is still far below the maximum

of the copper oxides. In other words excitations or boson-mediated pairing, to produce composite bosonic-charge quasiparticles that condense into superfluid state, is incapable of attaining high-

superconductivity.

The superconducting transition temperatures in the copper oxides, discovered in 1986, comes as a great surprise to the physics community. The maximum

greatly exceed those of any previously known superconductors. In fact, for HgBaCaCuO under pressure [

1], the highest

. This high

cannot be achieved by any boson-excitation mediated pairing mechanism of electrons. Generally, excitation above the ground state of a system is expected in the domain of low-energy physics. Although, several decades have passed since its discovery, no satisfactory theory has been able to explain the main phase diagram of high-

copper oxides. Moreover, the

stripy pattern of

unidirectional planar conduction in superconducting states, as seen in scanning tunneling spectroscopy (STS) [

2,

3], appears mysterious. The origin of complex spin texture of some copper oxides obtained by more recent spin-resolved ARPES remains heuristic or empirical [

4,

5,

6]. The holy grail lies in the search for a strong pairing mechanism, different from BCS paradigm, responsible for the high

of the copper oxides. The belief is that this new pairing mechanism is also responsible for the

strange metal behavior above the optimum superconducting temperature,

.

Here, we suggest that quantum entanglement and confinement (i.e., coupling strength increasing linearly with distance between pairs) present a new pairing mechanism, devoid of Coulomb repulsion, for strong coupling leading to high

superconductivity. This is essentially characterized by the ’stripy’ pattern of superconductive regions, or rivers of charge [

2,

3,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13] near and at optimal doping levels. These rivers of charge also acts as domain walls for the antiferromagnetic order [

14,

15,

16].

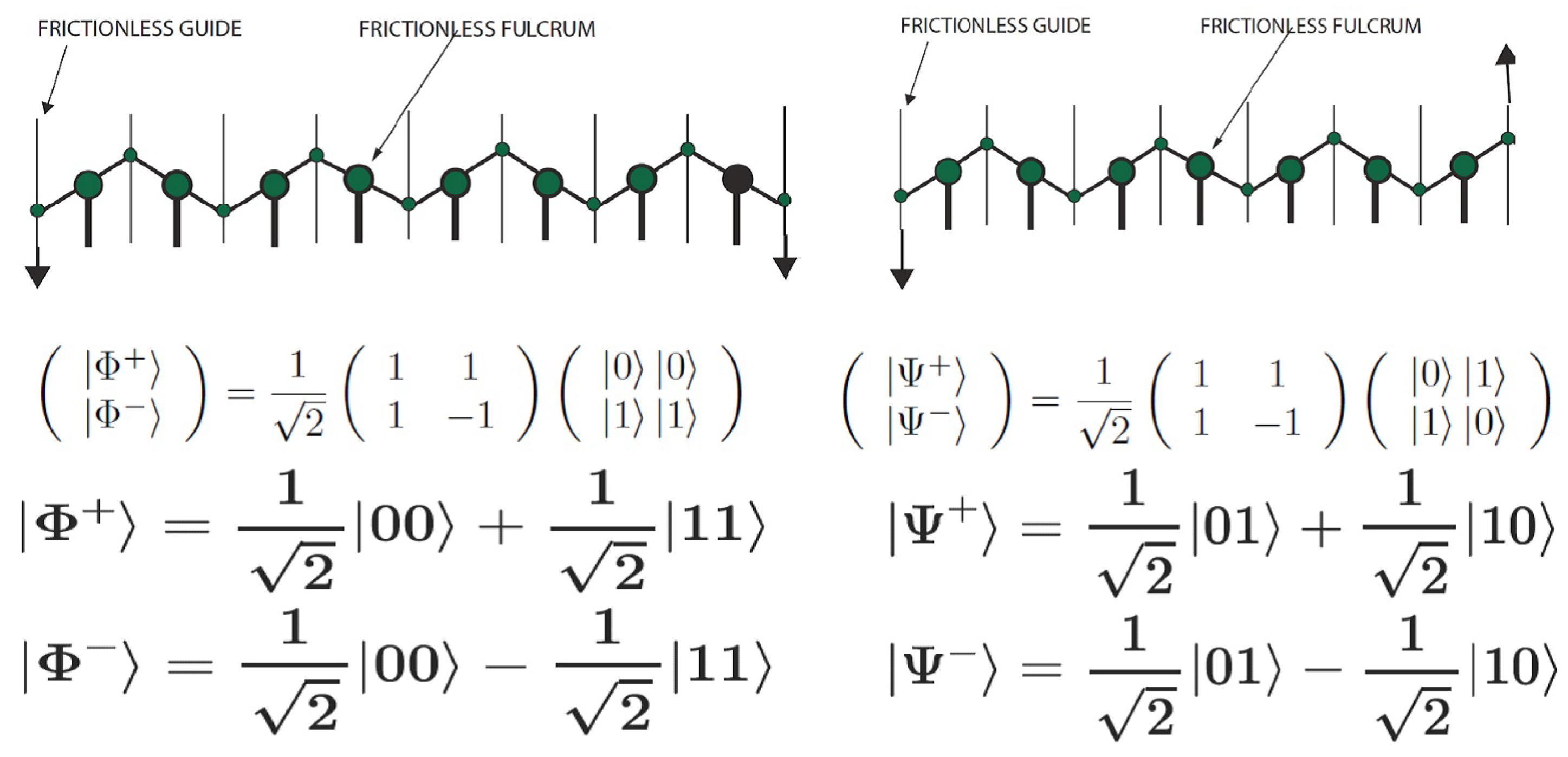

2. Entanglement as a Strong Pairing Mechanism

In preparation for employing the concept of quantum entanglement and confinement (or degree of entanglement) in proposing a new strong pairing mechanism for high-

cuprates, first we give some perspective and introduce a physical realization [

17,

18] of entanglement. The intention is to make similar considerations leading to the new pairing mechanism occurring in antiferromagnetic cuprates. This physical implementation of entanglement is schematically shown in

Figure 1

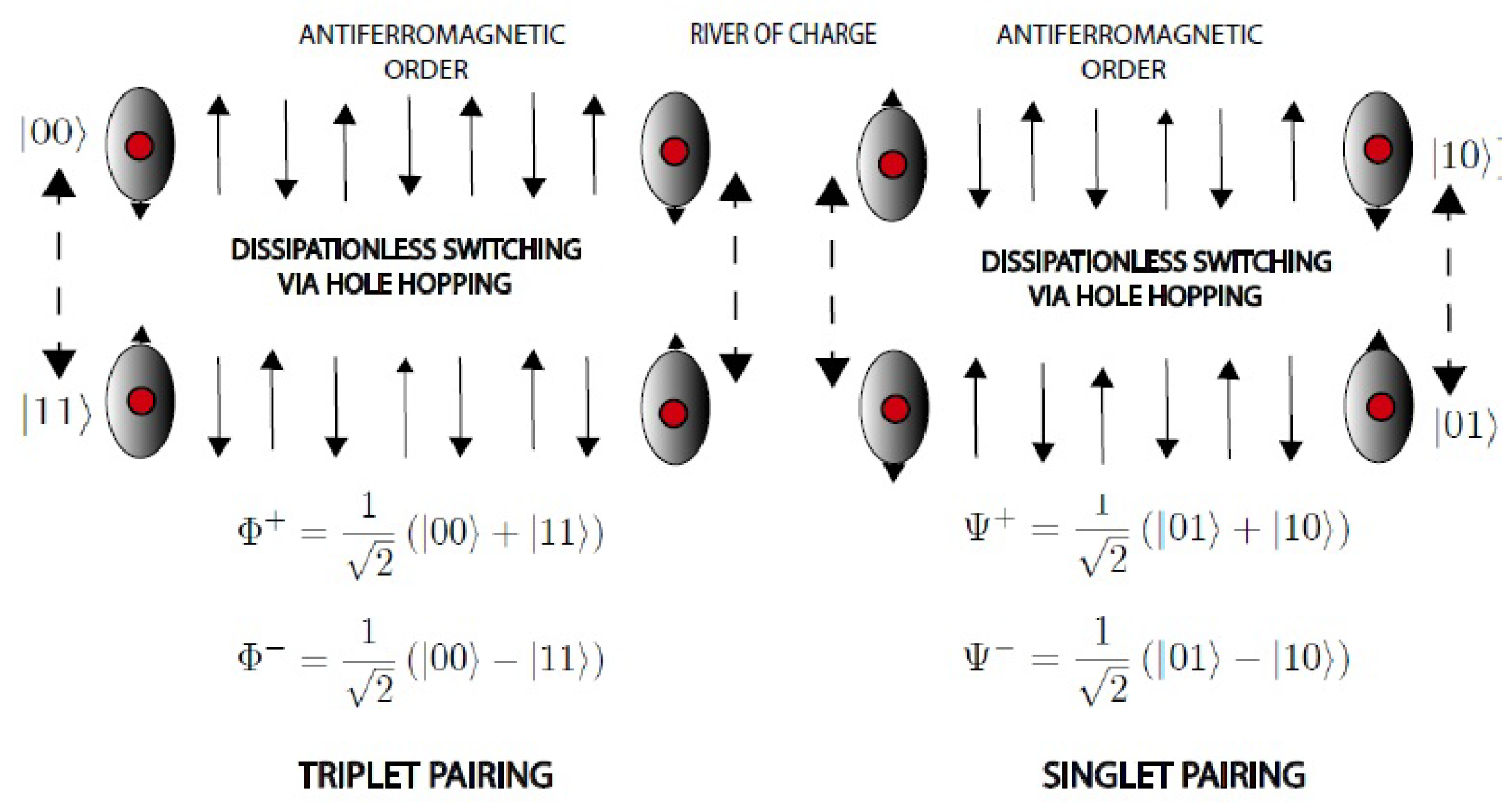

Mathematically, the inverter-chain link model of entanglement may be formulated as a series of

operations, represented by physical inverters or see-saws. Assume at first that there are two locally-entangled qubits

A and

B in either singlet or triplet state [

19], with singlet joined with one see-saw (

) or triplet joined by two see-saw’s (

⊗

). Then using the unitary single-qubit operation,

, on one of the two qubits will result in an additional extension of a inverter-chain-linked entangled two qubits, either

or

, depending on the initial singlet or triplet state. Using a series of

operations will then yield a physically longer inverter-chain link between the two entangled qubits. A series of odd number of

operations will result in eventual inversion of one of the qubit, whereas an even number of

operations is equivalent to an identify operation of one of the qubit, although the inverter-chain link is always extended by one see-saw with each

operation. In fact, the transformation function between the

or

Bell basis states is the Pauli inversion matrix operator

. Remarkably, a segment of antiferromagnetic chain is a realistic configuration of the above physical model of

Figure 1.

We can see that in realistic system, friction cannot be avoided, the length of the antiferromagnetic chain between coupled pair of spin determines the amount of coupling energy between the pair. Thus, by increasing the length of the antiferromagnetic chain between coupled pair of spin, the coupling energy also increases or the system becomes more stable compared to shorter link. This situation helps define confinement, i.e., the strength of interaction increases linearly with distance (

akin to strong force in quantum chromodynamics, mediated by gluons, which increases with distance). In other words, longer antiferromagnetic chain pairing is more stable than shorter chain. Moreover, as we shall see later, the

entanglement entropy of formation is larger for longer chain mediated pairing than for shorter chain pairing. This also defines weak and strong interaction between pairs of doped holes. If one considers the whole system, namely the two paired charges connected by antiferromagnetic chain, we basically have an

extended boson system. However, there must be an optimum chain length, or strength of pairing, to create a pattern or "lattice" of entangled pairs by symmetry considerations. This is seen experimentally by scanning tunneling spectroscopy (STS), for example, in cuprates [

2,

7].

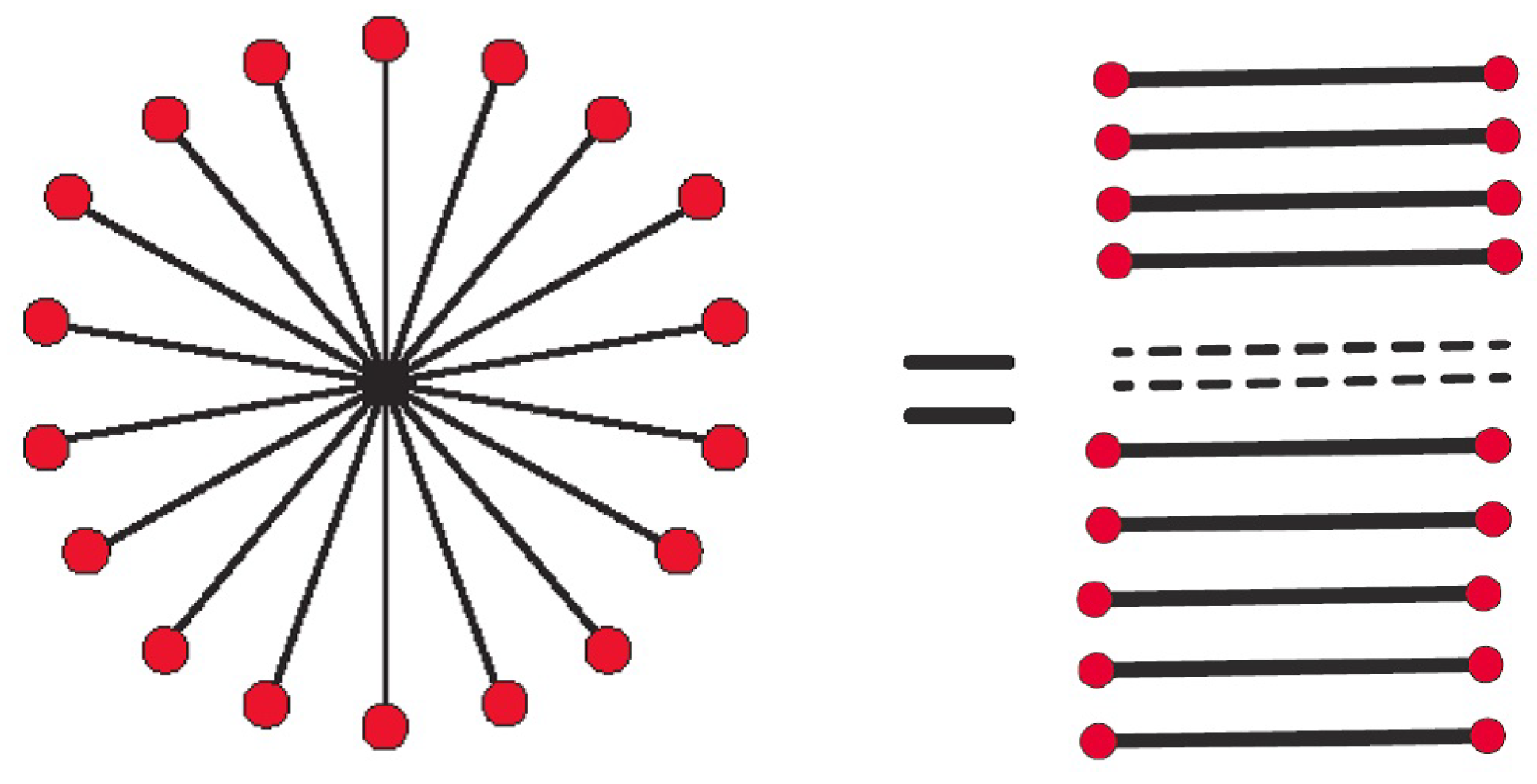

3. Monogamous Entanglement Versus Multi-Qubit Entanglement

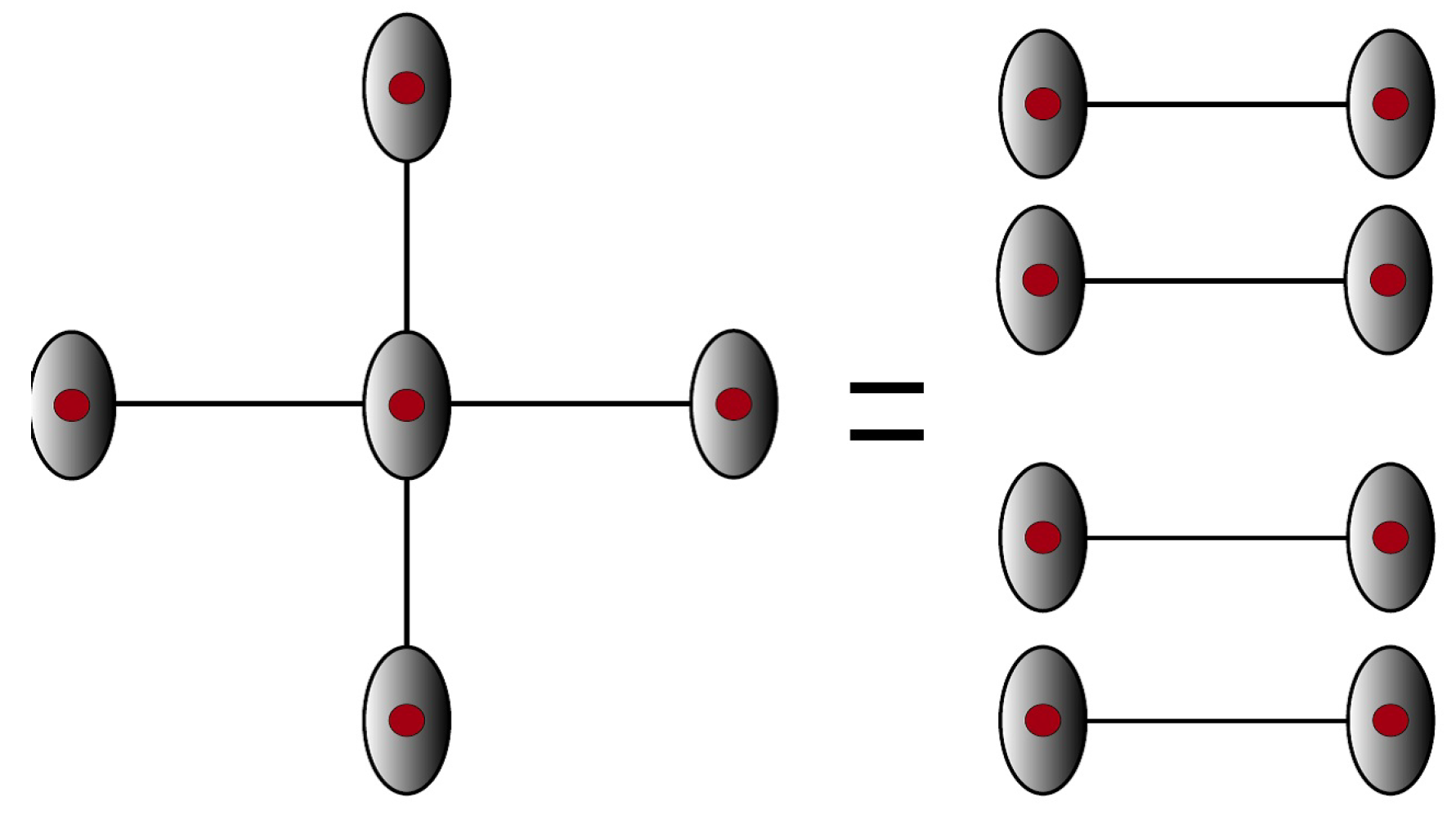

We continue our treatment of our physical realization of quantum mechanical entanglement.

Figure 2 shows that multi-qubit entanglement has the same

entanglement entropy of formation [

20,

21] as that of a corresponding number of monogamous qubit entanglement or entanglement in pairs. In cuprates, the monogamous doping atoms entanglement is probably more favored in nature, i.e., nature favors monogamy, in the absence of any external fields besides the unidirectional electric fields. The entanglement entropy of formation of monogamous or doping pair in cuprates is thought to be more favorable considering its antiferromagnetic lattice structure and one-dimensionality of charge conduction under electric fields. However, under the influence of external magnetic fields, the LHS of

Figure 2 may become a more favorable configuration to produce circular currents or current-carrying plaquettes.

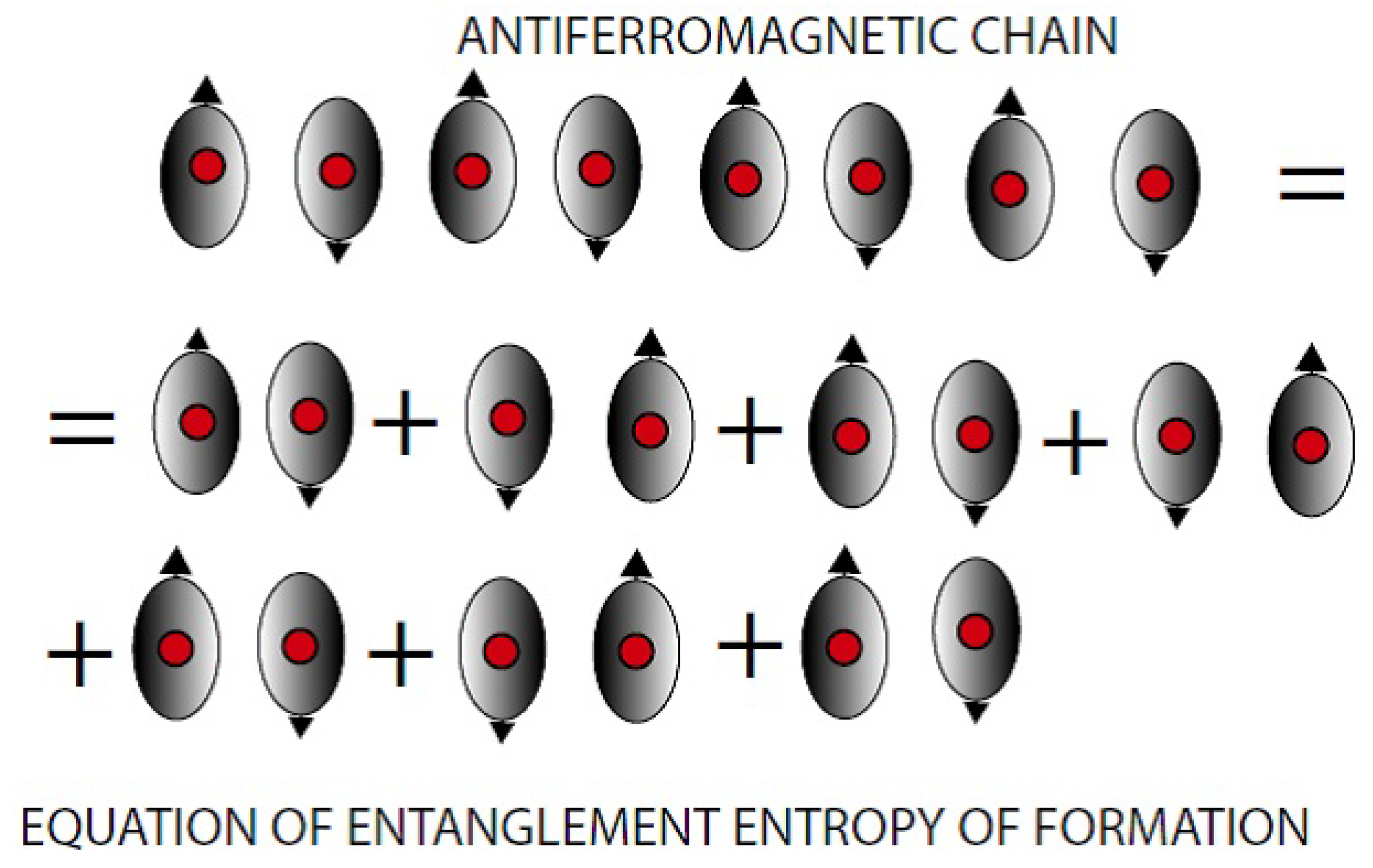

3.1. Entanglement entropy of formation for a 1D chain versus monogamy

Here we extend the concept of entanglement and confinement pertinent to our proposed new pairing mechanism in cuprates. In

Figure 3 is shown that the entanglement of formation of a longer chain is larger than the entanglement of formation of a shorter chain. This is the spirit of the concept of confinement employed in this paper.

4. Realization in High- Cuprates

In this section, we discuss how the ideas put forth in previous section are realized in high-

cuprates.

Figure 4 is thought to realize the principle of

Figure 2 in realistic antiferromagnetic cuprate environment. The lines represents the ferromagnetic ordered chains, while the ’

blob’ is our representation of renormalized hole [

2,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. In

Figure 4, the LHS of the equality, representing multiparticle entanglement, is less favored than the RHS equivalent arrangement having the same entanglement entropy of formation, following the discussion of

Figure 2. In condensed phase, the results is a pattern of

noninteracting entanglement pairings leading to ’rivers’ of charge. This is schematically depicted in

Figure 5.

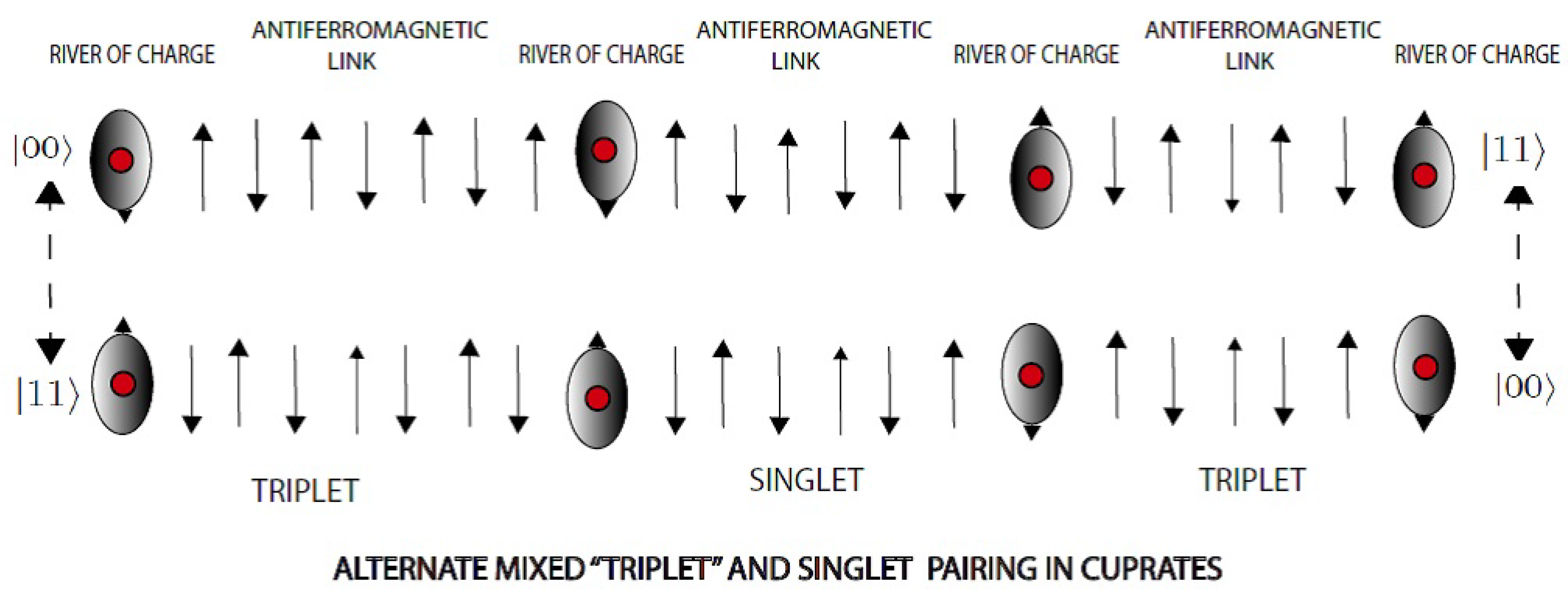

In

Figure 5, the formation of river of charge and periodic arrangement of alternate

and

entangled hole pair segments are strongly suggested. In condensed phase, these entangled pairs are all degenerate. The uncoupled

and

Bell basis states are thought to be the dominant contribution in the underdoped region of cuprates, as discussed below. This view agrees with some results of the SR-ARPES experiments.

5. Experiments Relevant to Proposed Pairing Mechanism

Here we mention some experimental works that validates the proposed entanglement pairing as the new mechanism in cuprates via antiferromagnetic entanglement links.

5.1. Experiments on Antiferromagnetic Entanglement Link Between Spins

The low-temperature magnetization and specific heat studies by Bayat [

27], Sahling [

28], and Sivkov [

29] on antiferromagnetic entanglement link between spins are directly relevant to our proposed entanglement pairing mechanism, and thus lending strong experimental support. The readers are referred to these references dealing with long-distance antiferromagnetic-chain entanglement link in solid state systems for more details [

27,

28,

29].

6. Experiments Relevant to Spin Dynamics of the Entanglement Mechanism

Here we mention some experimental works that bears on the spin-pairing structure of cuprates. The findings on the dependence on the doping level clearly signifies the dominant role of the entanglement of dopants, as independent Bell states or series of mixed (coupled) long chain of triplet-singlet entangled pairs, depending on the dopant level and doping material in the antiferromagnetic environment.

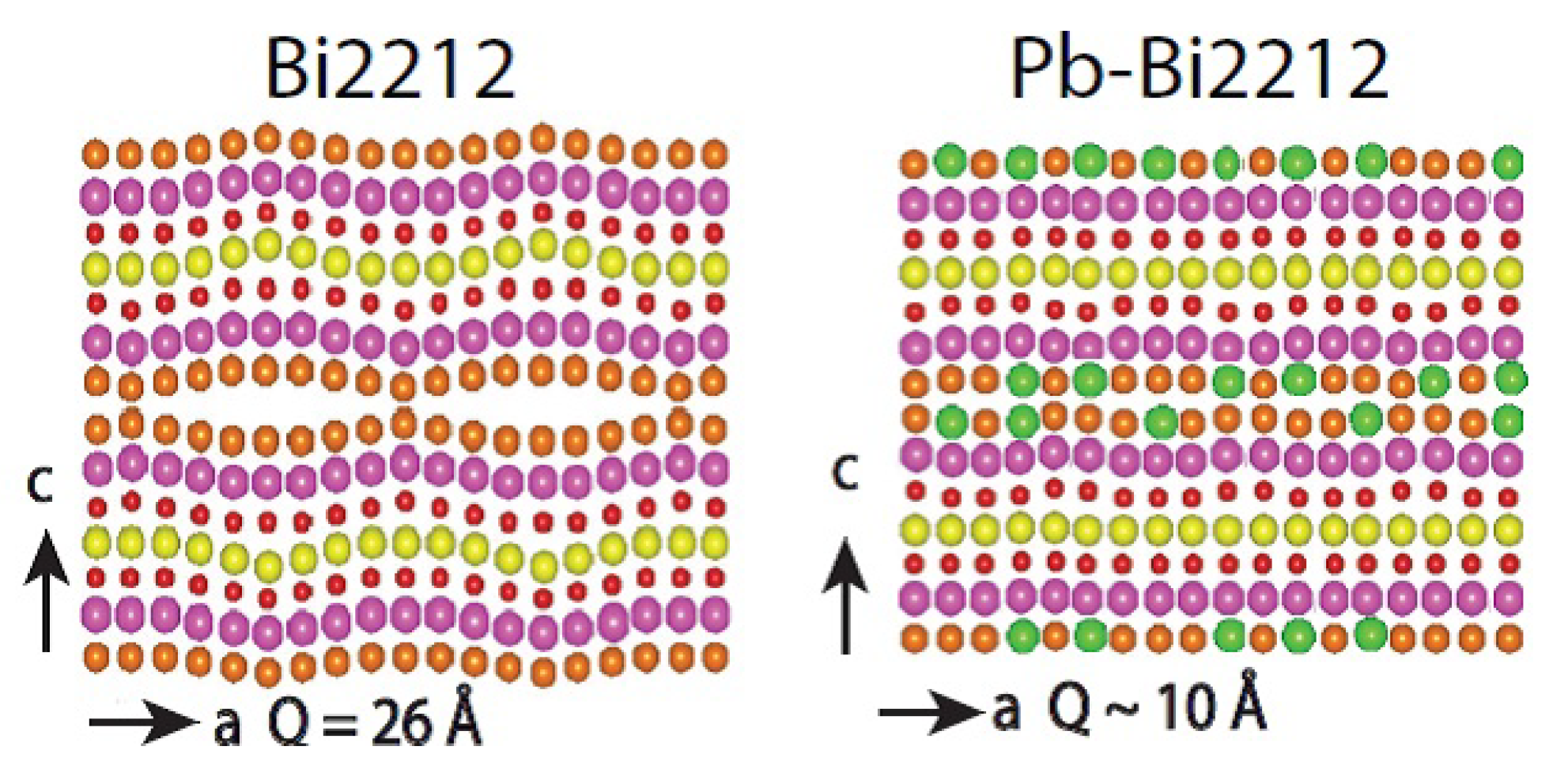

6.1. Doping Dependence of Spin Texture in High- Cuprates

Spin-resolved ARPES spectra on the spin texture of

(Bi2212) and Pb doped,

(Pb-Bi2212) has been performed, essentiallyby Gotlieb, et al [

4], by Iwasawa, et al [

5] and by Lou, et al [

6]. Iwasawa, et al have raised some of the difficulties in SR-ARPES experiments and emphasized that due to the complexity of the spin texture reported by Gotlieb, et al, the origin of the spin polarization in high-

cuprates remains unclear. Indeed, Iwasawa, et al SR-ARPES results [

5] differ from Gotlieb, et al [

4]. Here we sense some reproducibility issue perhaps due to the complex

dynamical origin of the spin texture which we will discuss below.

6.2. Single-Layer

The more recent paper by Lou, et la [

6] made interesting observations. Two main trends are observed in their data: (1) the first is a decrease of the spin polarization from overdoped to underdoped samples for both coherent and incoherent quasiparticles; (2) the second is the shift of spin polarization from positive to negative as a function of momentum.

The present concensus is that what drives the spin texture in high-temperature cuprate superconductors is the local structural fluctuations. In line with local symmetry breaking view proposed in Ref. [

6], we associate the pattern of entanglement schematically shown in

Figure 6

6.3. Suppression of Spin Polarization in Pb-Doped ( )

A striking reduction of the spin polarization is observed in the coherent part of the spectra for the Pb-doped sample, with respect to Bi2212, with the imbalance of the spin-up and spin-down intensities completely diminished [

30]. In the absence of or much reduced local symmetry breaking for Pb-doped (

)

[

6], we figure that the condensed phase of this boson system of degenerate states defines a pattern schematically depicted in

Figure 5.

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram of the out-of plane incommensurate distortion in over-doped Bi2212 and over-doped Pb-Bi2212 . The is much less distortion for the over-doped Pb-Bi2212 [Reproduced from Ref. [

30]

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram of the out-of plane incommensurate distortion in over-doped Bi2212 and over-doped Pb-Bi2212 . The is much less distortion for the over-doped Pb-Bi2212 [Reproduced from Ref. [

30]

7. Strange Metal and Overdoped Cuprates

Above

, the entangled pairs are no longer degenerate. The resistivity is linear at low temperature by virtue of the fact that entanglement allows for larger charge flow (hole flow at both ends of antiferromagnetic segments) in parallel of charge

since entanglement is still intact above

) compared to conventional metals for similar mean free path between scattering events. This complex scattering of extended entangled pairs will result in lower linear resistance at low temperature just above

and higher linear resistance at higher temperatures compared to conventional metals [

31].

7.1. Overdoped Region

In the over-doped regions, the weaken coupling brought by shorter intermediate antiferromagnetic-order link (weaker confinement or entanglement entropy of formation) between entangled holes, statistically brought about by the increasing population of holes, will on the average start to dominate so that superconductivity start to set in at lower temperatures than the optimal point. This decrease in will continue with further increase in doping levels, until a fermi liquid sets in and the system eventually behaves as conventional paramagnetic conductors.

8. Pseudo-Gap and Underdoped Region

The pseudo gap is probably a manifestation of the motion of single hole, i.e., dilute doping, in antiferromagnetic domain [

32,

33,

34]. Increase in doping levels would benefits from conventional BCS pairing through several excitation mechanisms, such magnons and so on. This results in gradual increase of

with the developing contribution of entangled pair of holes (i.e., contribution of strong entanglement pairing). At optimal doping the main contribution comes from the condensed pattern of entangled holes as depicted in

Figure 5.

9. Concluding Remarks

The concept of entanglement in strongly correlated system has been hinted before [

35,

36,

37]. The main point of this paper is that entanglement in the sense depicted in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 in condensed phase (simulating the frictionless system of

Figure 1) can readily explain the

stripy pattern of conduction characterized by the configuration of holes between antiferromagnetic order in high-

cuprates. It is also make sense that the periodicity of the

and

independent sections of the pattern obey apparent periodicity. The rivers of superconductive charge is a natural consequence of our model. The idea of confinement also help to elucidate the decrease of

with over doping. We believe our model is a good representation of the phase diagram from optimal doping to over doping, eventually resulting in fermi liquid and paramagnetic behavior of conventional metals. The entanglement also predict a lower resistivity at low temperature just above

in contrast with conventional metals, i.e., the linear resistivity at lower temperature just above

for strange metal, by virtue of strongly-coupled entangled pairs as the more effective conduction carriers that are subjected to mean-free path between scatterings. However, at much larger temperatures, our model can have much larger resistance than conventional metals.

9.1. Explanation of Spin Texture in SR-ARPES Experiments

Let us now discuss Lou, et la [

6] experimental observations.

The decrease of the spin polarization from overdoped to underdoped samples for both coherent and incoherent quasiparticles. It appears that for overdoped samples, the mixed triplet-singlet entanglement pairing behave in the manner depicted in

Figure 6, resulting in polarized river of charge, whereas in the underdoped samples these entanglement pairing are independent as shown in

Figure 5 with unpolarized river of charge;

The shift of spin polarization from positive to negative as a function of momentum. Iwasawa group [

5] raise some reproducibility issue of the SR-ARPES results with those of Gotlieb [

4] group, perhaps due to the complex

dynamical origin of the spin texture induced by the doping as shown in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6.

The present consensus is that local structural fluctuations drive the spin texture in high-temperature cuprate superconductors. In line with local symmetry breaking view proposed in Ref. [

6], we associate the pattern schematically shown in

Figure 6, showing the mixed up of the triplet-singlet entanglement pair with resulting spin dynamics, as the origin of the doping-dependent complex spin texture found in SR-ARPES experiments for overdoped region.

However, in the underdoped region the decrease in the polarization maybe due to the formation of independent or noninteracting and periodic arrangement of alternate and entangled hole pairs where the rivers of charge are unpolarized.

A striking reduction of the spin polarization or spin texture for the Pb-doped sample, with respect to Bi2212 [

30] is due to onset of periodic arrangement of alternate

and

entangled hole pairs where the rivers of charge are not polarized,

Figure 5 . This is consistent with the consensus that the source of spin texture is due to local structural fluctuations inducing the mixed entanglement pairing depicted in

Figure 6

9.2. Effect of Magnetic Field and Meissner Effect

The equality of the

entanglement entropy of formation between multi-qubit and monogamy allows for the flexibility of conduction directions in our model under the influence of external fields. It is conceivable that in the presence of the external magnetic field, an effective ’multi-qubit’ entanglement allows for the configuration phase of a circular charge or plaquette conduction channel similar to that depicted in

Figure 2. This will then induce the observable Meissner effect in superconductivity.

9.3. Impact on Nonequilibrium Superconductivity Theory

There is still the task of faithfully incorporating the correct expression for the entanglement pairing potential,

, indicated in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, into the most general nonequilibrium quantum transport physics of superconductivity [

38,

39]. Clearly,

will be a spatially modulated, nonlocal in phase space to account for changes in hole doping levels and spin dynamics. This will be an interesting research topic which has the potential to reveal much deeper fundamental physics of quantum materials.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to Roland E. Otadoy, Danilo Yanga, Unofre Pili for motivation and helpful comments on the manuscript, and to Gibson Maglasang, Allan R. Elnar, and Marcelo Callelero for helpful discussions.

References

- Keimer, B.; Kivelson, S.A.; Norman, M.R.; Uchida, S.; Zaanen, J. From quantum matter to high-temperature superconductivity in copper oxides. Nature 2015, 518, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaanen, J. High Tc superconductivity in copper oxides: the condensing bosons as stripy plaquettes. npj Quantum Materials 2023, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaanen, J. Why high-TCis exciting. arXiv 2001, arXiv:cond-mat/0103255. [Google Scholar]

- Gotlieb, K.; Lin, C.; Serbyn, M.; Zhang, W.; Smallwood, C.L.; Jozwiak, C.; Eisaki, H.; Hussain, Z.; Vishwanath, A.; Lanzara, A. Revealing hidden spin–momentum locking in a high-temperature cuprate superconductor. Science 2018, 362, 1271–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwasawa, H.; Sumida, K.; Ishida, S.; Fèvre, P.L.; Bertran, F.; Yoshida, Y.; Eisaki, H.; Santander-Syro, A.F.; Okuda, T. Exploring spin-polarization in Bi-based high-TC cuprates. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 13451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Currier, K.; Lin, C.; Gotlieb, K.; Mori, R.; Esaki, H.; Fedorov, A.; Hussain, Z.; Lanzara, A. Doping dependence of spin-momentum locking in bismuth-based high-temperature cuprate superconductors. Com. Materials 2024, 5, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaanen, J. Self-Organized One Dimensionality. Science 1999, 286, 251–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razkowski, M.; Oles, A.M.; Frésard, R. Stripe phases - possible ground state of the high-Tc superondutors. arXiv 2005, arXiv:cond-mat/0512420. [Google Scholar]

- Emery, V.J.; Kivelson, S.A.; Tranquada, J.M. Stripe phases in high-temperature superconductors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 8814–8817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simutis, G.; Küspert, J.; Wang, Q.; Choi, J.; Bucher, D.; Boehm, M.; Bourdarot, F.; Bertelsen, M.; Wang, C.N.; Kurosawa, T.; Momono, N.; Oda, M.; nsson, M.M.; Sassa, Y.; Janoschek, M.; Christensen, N.B.; Chang, J.; Mazzone, D.G. Single-domain stripe order in a high-temperature superconductor. Comms. Phys. 2022, 5, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lane, C.; Furness, J.W.; Barbiellini, B.; Perdew, J.P.; Markiewicz, R.S.; Bansil, A.; Sun, J. Competing stripe and magnetic phases in the cuprates from first principles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loder, F.; Graser, S.; Schmid, M.; Kampf, A.P.; Kopp, T. Modeling of superconducting stripe phases in high-Tc cuprates. New J. Phys. 2011, 13, 113037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Ying, T.; Scalettar, R.T.; Mondaini, R. Stripes and the Emergence of Charge π-phase Shifts in Isotropically Paired Systems. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.17305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Chung, C.-M.; Qin, M.; Schollwöck, U.; White, S.R.; Zhang, S. Coexistence of superconductivity with partially filled stripes in the Hubbard model. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.085376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons Foundation. Quantum Mystery Solved – Scientists Shed Light on Perplexing High-Temperature Superconductors. Scitech Daily -Physics 2024.

- Ma, Q.; Rule, K.C.; Cronkwright, Z.W.; Dragomir, M.; Mitchell, G.; Smith, E.M.; Chi, S.; Kolesnikov, A.I.; Stone, M.B.; Gaulin, B.D. Parallel Spin Stripes and Their Coexistence with Superconducting Ground States at Optimal and High Doping in La1.6-xNd0.4SrxCuO4. arXiv See also Science 2024, 384, 6696. 2024, arXiv:2009.04627. See also Science 2024, 384, 6696384, 6696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buot, F.A.; Otadoy, R.E.S.; Bacalla, A.X.L. An inverter-chain link implementation of quantum teleportation and superdense coding. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.03276V2. [Google Scholar]

- Buot, F.A.; Elnar, A.R.; Maglasang, G.; Galon, C.M. A Mechanical Implementation and Diagrammatic Calculation of Entangled Basis States. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2112.10291. [Google Scholar]

- The use of the term “triplet” is actually a misnomer here since the entangled system is not free to assume a singlet or zero spin state. It has only two states. Thus, this term is used here only as a label. Indeed, the transformation function between triplet and singlet is the Pauli spin matrix operator, σx.

- Buot, F.A. Baker, O.K., Ed.; Perspective Chapter: On entanglement measure-Discrete phase space and inverter chain link viewpoint, Chapter 3. In Quantum Entanglement in High Energy Physics; Intech Open Book, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Buot, F.A. Nonequilibrium Quantum Transport Theory of Spinful and Topological Systems (Part 5); World Scientific, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, D.N.; Chen, Y.C.; Weng, Z.Y. Phase String Effect in a Doped Antiferromagnet. Phys. Rev. Letts. 1996, 77, 5102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Z.Y.; Sheng, D.N.; Chen, Y.-C.; Ting, C.S. Phase String Effect in the t - J Model: General Theory. Phys. Rev. B 1997, 55, 3894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Z.-Y. Phase string theory for doped antiferromagnets. arXiv 2007, arXiv:0704.2875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilov, M.; van Loon, E.G.C.P.; Brener, S.; Iskakov, S.; Katsnelson, M.I.; Lichtenstein, A.I. Degenerate plaquette physics as key ingredient of high-temperature superconductivity in cuprates. npj Quantum Materials 2022, 7, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.-Y.; Weng, Z.-Y. Mottness, Phase String, and High-Tc Superconductivity. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2204.05504. [Google Scholar]

- Bayat, A.; Bose, S. Entanglement Transfer through an Antiferromagnetic Spin Chain. Advances in Math. Physics 2009, 2010, 127182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahling, S.; Remenyi, G.; Paulsen, C.; Monceau, P.; Saligrama, V.; Marin, C.; Revcolevschi, A.; Regnault, L.P.; Raymond, S.; Lorenzo, J.E. Experimental realization of long-distance entanglement between spins in antiferromagnetic quantum spin chains. 2015. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272426327.

- Sivkov, I.N.; Bazhanov, D.; Stepanyuk, V.S. Switching of spins and entanglement in surface-supported antiferromagnetic chains. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currier, K.; Lin, C.Y.; Gotlieb, K.; Mori, R.; Eisaki, H.; Greven, M.; Fedorov, A.; Hussain, Z.; Lanzara, A. Driving Spin Texture in High-Temperature Cuprate Superconductors via Local Structural Fluctuations. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.A.; Guo, H.; Esterlis, I.; Sachdev, S. Universal theory of strange metals from spatially random interactions. Science See also The Mystery of “Strange” Metals Explained, Physics 16, 148, August 31, (2023). 2023, 381, 790–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sous, J.; Pretko, M. Fractons from frustration in hole-doped antiferromagnets. npj Quantum Materials 2020, 81, Published. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdev, S.; Shankar, R. Superconductivity of itinerant· electrons coupled to spin chains. Phys. Rev B 1988, 38, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlömer, H.; Hilker, T.A.; Bloch, I.; Schollwxoxck, U.; Grusdt, F.; Bohrdt, A. Quantifying hole-motion-induced frustration in doped antiferromagnets by Hamiltonian reconstruction. Comm. Materials 2023, 4, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivkov, I.N.; Bazhanov, D.I.; Stepanyuk, V.S. Switching of spins and entanglement in surface-supported antiferromagnetic chains. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, C.; Sémon, P.; Poulin, D.; Sordi, G.; Tremblay, A.-M.S. Entanglement and Classical Correlations at the Doping-Driven Mott Transition in the Two-Dimensional Hubbard Model. PRX Quantum 2020, 1, 020310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitaev, A.Y. Talks at KITP, University of California, Santa Barbara Entanglement in Strongly-Correlated Quantum Matter, 2015.

- Buot, F.A. Nonequilibrium Quantum Transport Physics in Nanosystems; World Scientific, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Buot, F.A. General theory of quantum distribution function transport equations. La Rivista del Nuovo Cimento 1997, 20, 1–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).