1. Introduction

1.1. What Is the Gut Microbiota?

In recent years, interest in the relationship between an individual and the microorganisms residing in their gut has grown significantly. The gut microbiota consists of a vast array of bacteria, fungi, viruses, archaea, and protozoa that inhabit the host's gastrointestinal tract, establishing a symbiotic relationship. This diverse microbial community plays a crucial role in canine health and immunity, influencing a wide range of physiological functions, including nutrient digestion, vitamin synthesis, immune response modulation, and protection against pathogens [

1,

2,

3].

The composition of the human gut microbiota varies along the gastrointestinal tract. Microbial populations are sparse in the stomach and small intestine, whereas the large intestine harbors approximately 10¹² bacteria per gram, encompassing between 300 and 1,000 distinct species, most of which are anaerobic. The predominant phyla in the human gut microbiota include Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, and Proteobacteria. The most representative bacterial genera are

Bacteroides,

Clostridium,

Peptococcus,

Bifidobacterium,

Eubacterium,

Ruminococcus,

Faecalibacterium, and

Peptostreptococcus [

4]. Microbial diversity reaches its peak when Bacteroidetes account for 15% of the total population and Firmicutes comprise 80%. Additionally, the presence of Tenericutes, Euryarchaeota, Lentisphaerae, and Cyanobacteria has been associated with increased diversity, whereas Proteobacteria and Fusobacteria are linked to lower diversity levels [

5]. In-depth analysis of microbiota composition and structural differences between healthy and diseased individuals has led to the development of microbiota-targeted therapeutic strategies for various medical conditions [

6].

The composition of the gut microbiota is currently one of the most dynamic fields of scientific research, due to its profound impact on human health. Microbiota balance is often evaluated through overall diversity, commonly assessed using alpha and beta diversity metrics. These parameters quantify differences in microbial composition between individuals or groups. Alpha diversity measures microbiota richness (the number of taxonomic groups present) and evenness (the relative abundance of each taxonomic group) within a single sample or population. In contrast, beta diversity assesses compositional differences between distinct groups or samples [

7].

A lower alpha diversity has been associated with the onset of both acute and chronic diseases [

5], particularly inflammatory and autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, and multiple sclerosis [

8]. Certain diseases, such as colorectal cancer, are linked to an increased presence of pathogenic bacteria (

Fusobacterium,

Porphyromonas,

Peptostreptococcus,

Parvimonas, and

Enterobacter). In contrast, conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease are more prevalent in individuals with a reduced abundance of beneficial bacterial families (Ruminococcaceae and Lachnospiraceae) within their gut microbiota [

9].

Like humans, animals and the environment also harbor a highly diverse microbiota, whose composition significantly influences host health. Human, animal, and environmental health are deeply interconnected, with each relying on the others. As part of this intricate relationship, genetic material is exchanged among the microorganisms that comprise the microbiota of these three components. This highlights the fundamental role of the microbiota in humans, animals, and the environment within the One Health framework [

10,

11].

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) genes, present in both pathogenic and commensal bacteria within the microbiota, can be horizontally transferred to other bacterial species through conjugation, transduction, and transformation. However, antibiotic residues and resistance genes enter the environment through various sources, including hospital wastewater, excreta from domestic and livestock animals, and pollutants generated during antibiotic production. These factors promote the development and dissemination of antimicrobial resistance within environmental microbiota. Environmental bacteria can, in turn, colonize the gut microbiota of wild animals within an ecosystem. Additionally, these microorganisms can travel long distances via aerosols, water, or wildlife, eventually returning to humans and domestic or livestock animals through food and drinking water. This cycle underscores the intricate interconnection between human, animal, and environmental microbiota and their crucial role in the spread of antimicrobial resistance among these hosts [

10,

11,

12].

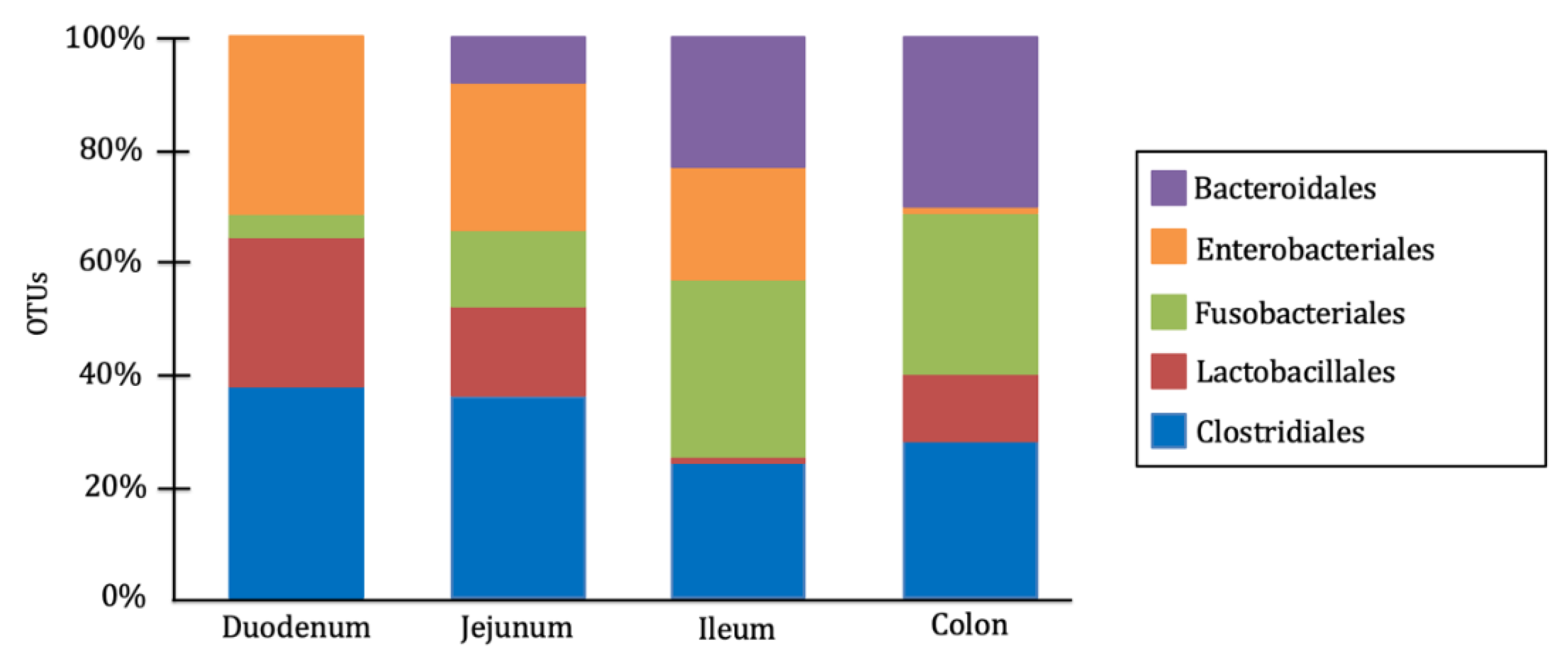

In dogs, the gut microbiota is composed of a wide variety of microbial genera, with their specific distribution having a significant impact on host health. The predominant bacterial phyla in the canine gut microbiota include Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, Fusobacteria, and Actinobacteria [

1,

13]. However, their composition varies across different intestinal segments, adapting to the conditions, metabolites, and physiological functions of each region. Anaerobic bacteria predominate in the large intestine, whereas the small intestine harbors a similar proportion of aerobic and facultative anaerobic bacteria. The order Clostridiales is dominant in the duodenum and jejunum, while Fusobacteriales and Bacteroidales are most abundant in the ileum and colon. Additionally, the order Lactobacillales are widely distributed throughout the entire intestinal tract, whereas Enterobacteriales are more prevalent in the small intestine than in the large intestine [

14,

15] (

Figure 1).

Therefore, the canine gut microbiota consists of a diverse range of bacterial genera and other microorganisms, forming intricate interdependent relationships that contribute to a complex equilibrium essential for host health. This microbial community protects the intestinal mucosa from pathogen colonization and supports gastrointestinal health through the fermentation of carbohydrates and low-digestibility proteins, participation in bile acid metabolism, and production of a wide array of metabolites involved in gastrointestinal functions and various physiological processes in other organs and systems [

1,

13].

1.2. Intestinal Dysbiosis and Its Effects on Canine Health

This delicate balance within the gut microbiota, closely linked to microbial diversity, can be disrupted by numerous factors, including diet, antibiotic use, host immune response, and the presence of pathogenic bacteria, among others. Such disturbances can lead to an imbalance in the microbial composition, known as dysbiosis. Intestinal dysbiosis results in impaired microbial function, reducing its contribution to nutrient digestion and the production of essential metabolites for the host [

1,

13]. These functional alterations in the gut microbiota can trigger acute digestive disorders, such as diarrhea, and predispose dogs to chronic digestive conditions like inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [

15].

In general, dysbiosis increases intestinal epithelial permeability, facilitating the translocation of inflammatory compounds, such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), into the bloodstream. This, in turn, triggers the release of proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-1 and TNF-α. If this condition persists chronically, prolonged inflammation may lead to the development of systemic allergic and immune-mediated diseases, as well as structural damage to organs, such as joints and blood vessels [

16]. Due to the close relationship between the microbiota and the rest of the body (

Figure 2), alterations in microbial composition have been associated with various canine diseases, including atopic dermatitis [

17], osteoarthritis [

18], behavioral disorders [

3,

19], and chronic kidney disease [

20].

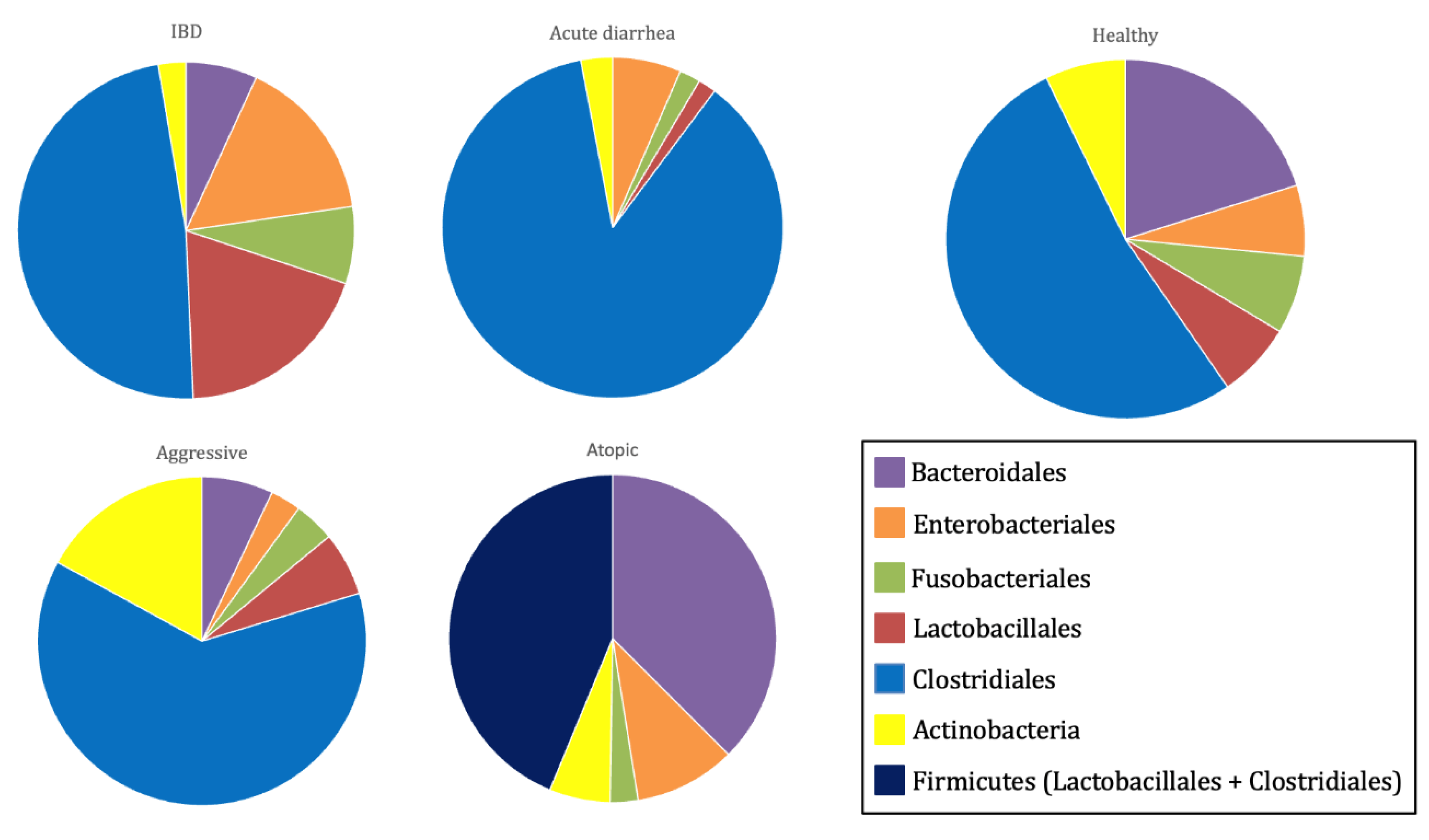

These findings explain the observed differences in gut microbiota composition and diversity between healthy and diseased dogs [

15]. In healthy dogs, the gut microbiota is characterized by a higher abundance of bacterial species from the families Lachnospiraceae, Anaerovoracaceae, and Oscillospiraceae, as well as the genera

Ruminococcus,

Fusobacterium, and

Fecalibacterium [

17]. Conversely, dogs with acute diarrhea commonly exhibit a reduction in Bacteroidetes populations and in key bacterial families involved in short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production, such as Erysipelotrichaceae (e.g.,

Turicibacter), Ruminococcaceae (e.g.,

Ruminococcus and

Faecalibacterium), and Lachnospiraceae (e.g.,

Blautia). Additionally, these dogs show an increase in Fusobacteria, as well as the genera

Clostridium and

Sutterella [

15].

In dogs suffering from chronic enteropathies, including IBD, a decline in

Faecalibacterium spp. and Fusobacteria populations has been observed [

15]. Dogs with atopic dermatitis present lower alpha diversity than their healthy counterparts, with increased representation of the genera

Conchiformibius,

Catenibacterium, and

Megamonas [

17]. Similarly, dogs with osteoarthritis exhibit a gut microbiota enriched in

Megamonas, while showing a decreased abundance of bacterial families Paraprevotellaceae, Porphyromonadaceae, and Mogibacteriaceae [

18]. Furthermore, aggressive dogs display a more diverse microbiome than healthy dogs, with a predominance of the genera

Catenibacterium and

Megamonas [

3,

19] (

Figure 3).

Therefore, the wide range of functions performed by the intestinal microbiota extends beyond digestive health, influencing the overall well-being of the individual. This has led to the identification of several physiological axes, such as the gut-brain axis, which relies on a bidirectional communication network between the enteric nervous system (ENS) and the central nervous system (CNS), with serotonin being the key neurotransmitter of this axis. Due to its role in tryptophan metabolism and serotonin production, the intestinal microbiota has been shown to be essential in this axis and has been linked to the development of behavioral disorders [

3,

19].

Another important connection is the gut-lung axis, which highlights the close relationship between the microbiota in both organs. Under normal conditions, dendritic cells process antigens present in the intestine and promote T lymphocyte proliferation in locations exposed to pathogen entry, such as the respiratory tract. However, in cases of intestinal dysbiosis, an imbalance in bacterial metabolite synthesis and an increase in proinflammatory mediators lead to dysregulation in the maturation and proliferation of T lymphocytes in the respiratory tract, altering immune responses in this region. As a result, intestinal dysbiosis has been associated with respiratory infections and other conditions, including asthma and allergic respiratory diseases [

21].

Similarly, the gut-skin axis describes the bidirectional relationship between the microbiota of both organs. In cases of intestinal dysbiosis, increased intestinal epithelial permeability facilitates the absorption of inflammatory cytokines, whose production is also elevated. The proinflammatory activity of these molecules in the skin promotes the development of various conditions, such as erythematous processes, atopic dermatitis, and other allergic disorders [

22].

Another example is the gut-kidney axis, in whichthe microbiota also plays a crucial role. Studies have shown a higher prevalence of intestinal dysbiosis in dogs with chronic kidney disease. In these patients, the bacterial composition of their intestinal microbiota leads to increased production of uremic toxins, such as indoxyl sulfate (IS) and p-cresyl sulfate (pCS), which contribute to nephron damage and the progression of kidney disease [

20].

1.3. Modulation of Intestinal Microbiota Composition

Studies on various animal species have shown that diet significantly influences the composition and diversity of intestinal microbiota, establishing a direct relationship between specific types of food and changes in the gut microbiome is challenging in dogs, which are classified as omnivorous. However, variations in nutritional components, particularly fiber quantity and type, have been associated with microbiota alterations [

3,

23]. Diets with higher crude protein content but lower crude fiber and nitrogen-free extract reduce the abundance of bacteria from the genera

Peptostreptococcus,

Faecalibacterium,

Bacteroides, and

Prevotella. These bacteria are involved in the fermentation of dietary fiber and carbohydrates, producing short-chain fatty acids, which play a crucial role in host health. Consequently, their reduction can have detrimental effects [

3,

24,

25].

These findings suggest that the canine intestinal microbiota can adapt to physiological needs depending on dietary intake. However, this microbial population is also influenced by external factors, such as antibiotics [

26]. Numerous adverse gastrointestinal effects have been reported following antibiotic administration, as these drugs induce intestinal dysbiosis by disrupt the host’s microbiota [

26,

27]. Antibiotic use significantly reduces both alpha and beta diversity, which has been linked to the development of various conditions, including immune-mediated disorders, atopic dermatitis, degenerative joint disease, and skin allergies [

17,

18,

28,

29].

The increasing recognition of the intestinal microbiota’s role has driven the field of animal nutrition towards the use of functional ingredients and bioactive compounds to modulate gut microbial composition and enhance overall canine health (

Figure 4). This approach includes prebiotics, probiotics, and symbiotics, with postbiotics recently added to the list [

13,

30].

Prebiotics are nutritional compounds (typically fiber-based) that resist intestinal digestion, absorption, and adsorption, allowing them to be fermented by the host's gut microbiota. This fermentation promotes the growth or activity of specific bacterial species, leading to beneficial changes in microbiota composition, increased microbial diversity, and enhanced short-chain fatty acid production, all of which positively impact host health [

31,

32]. The most commonly used prebiotics in canine nutrition include lactulose, fructooligosaccharides (FOS), inulin, beta-glucans, and mannan-oligosaccharides (MOS) [

33].

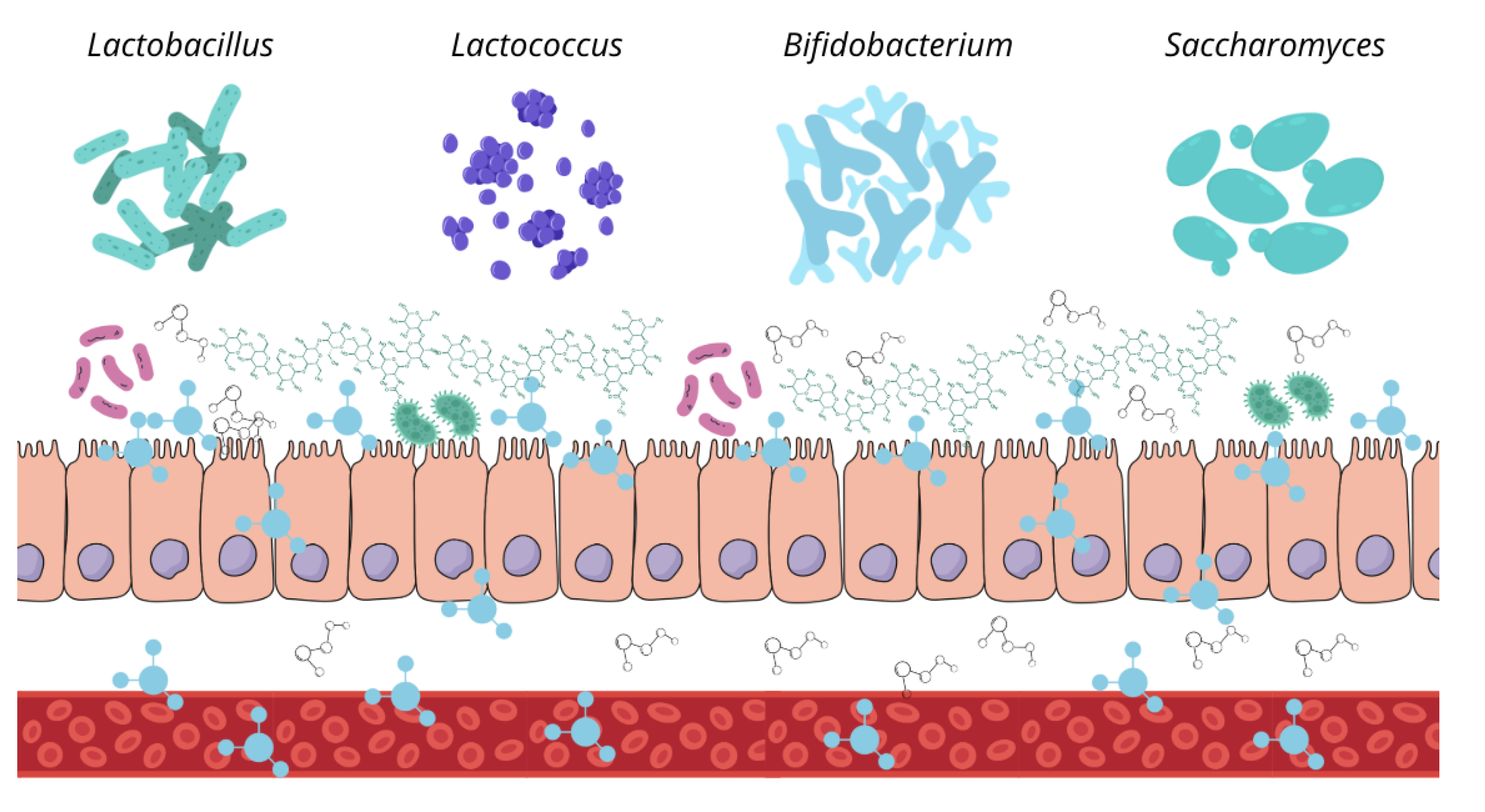

Probiotics are live microorganisms that have been isolated and characterized, with scientific evidence supporting their health benefits when administered in adequate amounts. Ideally, these microorganisms should be non-pathogenic to the host, capable of withstanding low pH and high bile acid concentrations (intestinal conditions), and able to adhere to the intestinal epithelium. Probiotic supplementation allows for the introduction of beneficial bacteria into the intestinal microbiota, helping to maintain microbial balance and the physiological processes it regulates [

34].

Symbiotics are products that combine prebiotics and probiotics, enhancing the benefits of both while improving the survival of these supplements in the gastrointestinal tract. The most commonly used probiotics in these formulations include

Saccharomyces boulardii,

Heyndrickxia coagulans, and bacteria from the genera

Lactobacillus and

Bifidobacterium. Regarding prebiotics, fructooligosaccharides (FOS), galactooligosaccharides (GOS), xylooligosaccharides (XOS), and inulin are commonly used [

35].

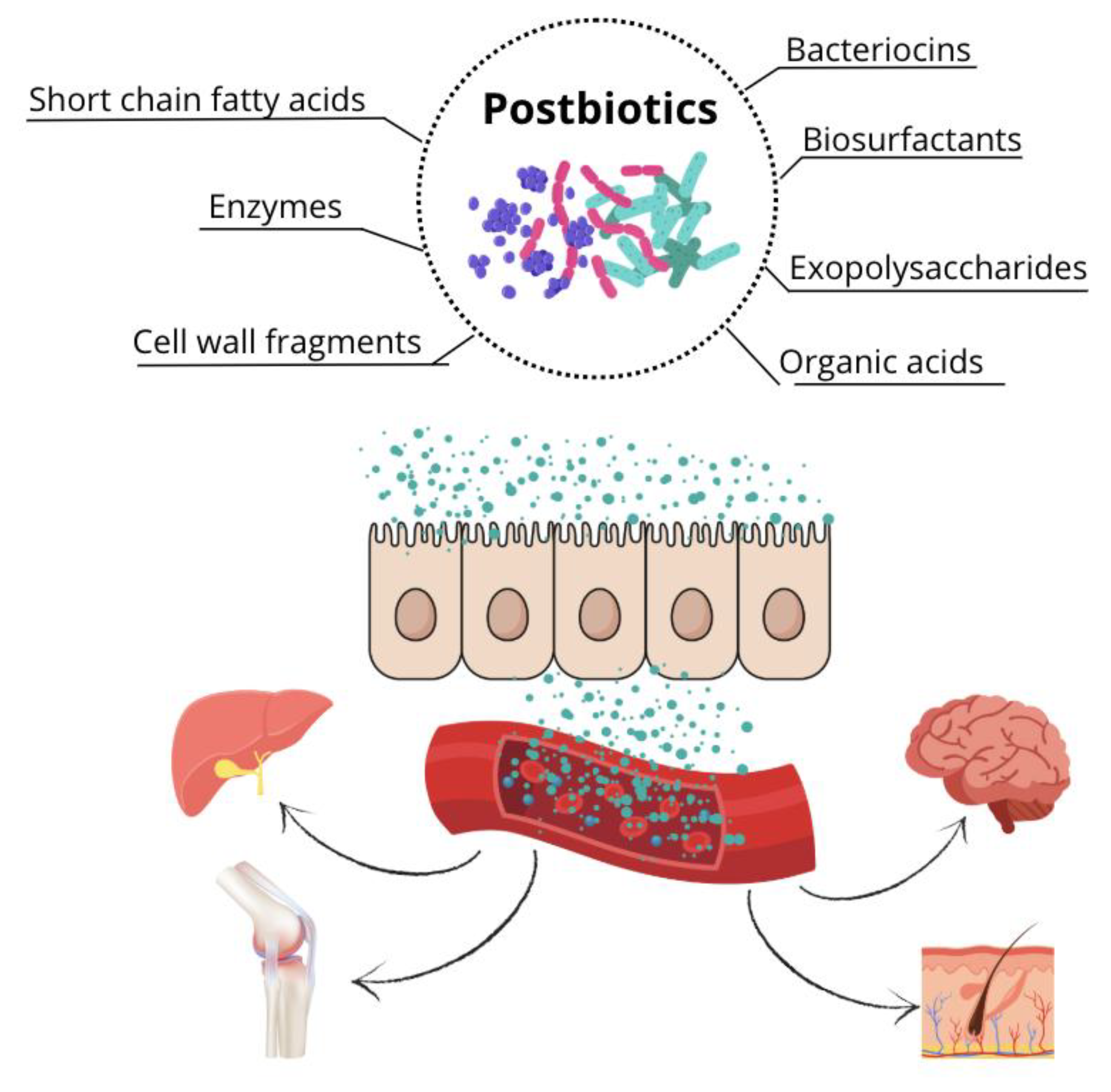

The term postbiotic was defined in 2021 by the International Scientific Association of Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) as a preparation of inactivated microorganisms and/or their components that provide health benefits to the host [

32]. Therefore, postbiotics are soluble, bioactive metabolic products secreted by live bacteria or yeasts and released during fermentation following cell membrane lysis. Their composition includes both metabolites (enzymes, peptides, proteins, exopolysaccharides, organic acids, and lipids) and structural components of the bacterial cell wall (teichoic and lipoteichoic acids, peptidoglycans, bacterial surface layer proteins, and other polysaccharides) [

36,

37]. The use of postbiotics in dogs is a relatively recent development. Therefore, this literature review aims to explore the existing types of postbiotics, their mechanisms of action, and their effects on canine health.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Systematic Literature Review

The bibliographic search for this study was conducted using three online databases: PubMed (National Library of Medicine, NIH), Scopus (Elsevier), and Web of Science (Clarivate Analytics). The research question formulated to guide this review was: "What types of postbiotics exist, how do they exert their action, and what effects do they have on canine health?".

To maximize the number of relevant articles for each aspect of the research question, the following keywords were used, combining different Boolean operators: [(postbiotic OR postbiotics) AND (type) AND (mechanism OR action)] OR [(dog OR dogs OR Canis familiaris) AND (treatment OR treatments OR therapy OR therapies OR therapeutic) AND (postbiotic OR postbiotics)].

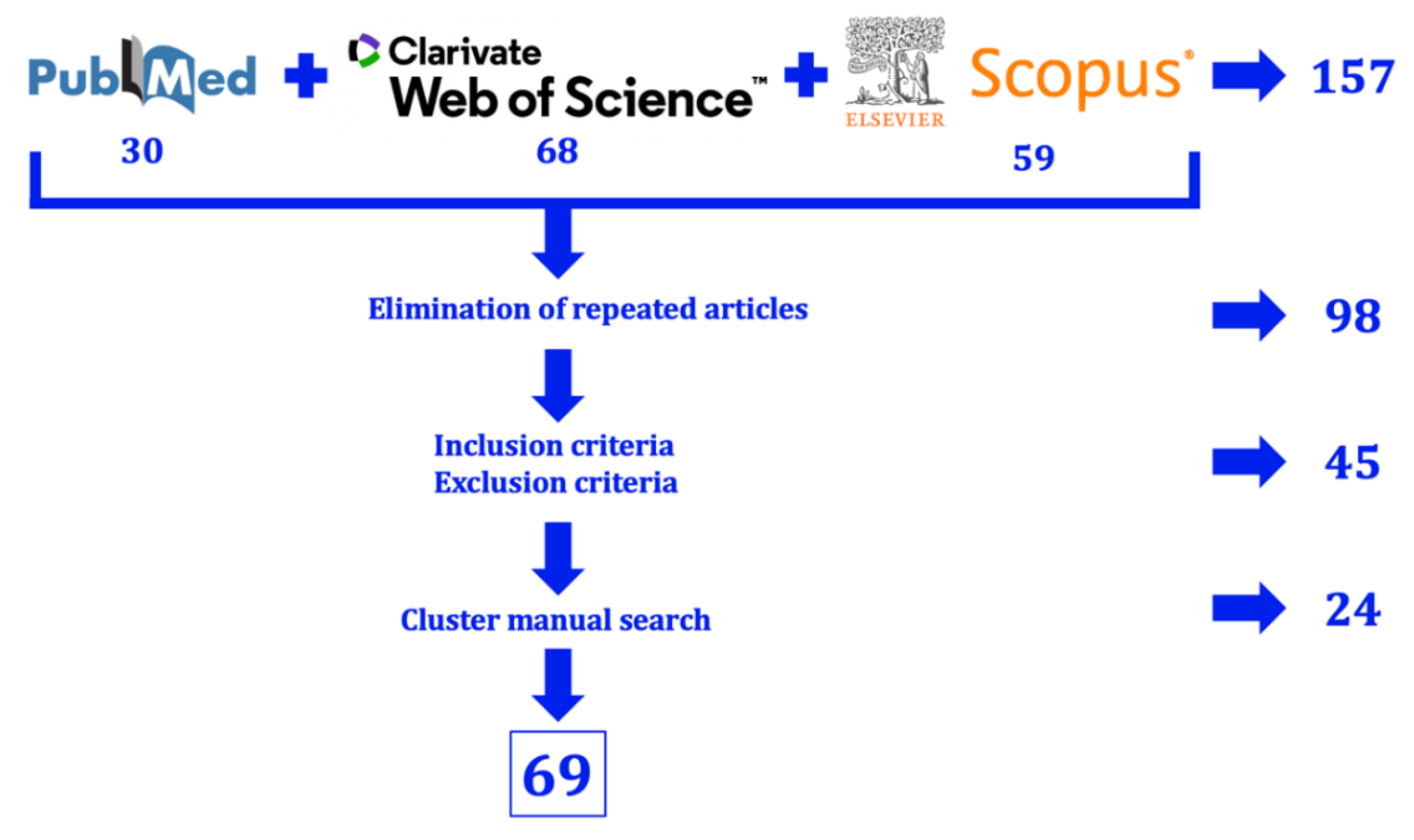

Using this search equation (conducted between September 22, 2024, and October 10, 2024), a total of 157 results were obtained (30 from PubMed, 59 from Scopus, and 68 from Web of Science). After removing duplicate articles, 98 unique records remained.

This list of articles was then reviewed according to the inclusion criteria (descriptive studies and literature reviews on postbiotic types and mechanisms of action; in vivo studies evaluating the effects of products containing at least one postbiotic component on canine health) and the exclusion criteria (in vivo studies assessing postbiotic administration in non-canine species; studies on postbiotics in dogs that had not undergone peer review; reviews and articles discussing other types of biotics).

After applying these criteria, only 45 relevant articles remained. This reduction was because many retrieved studies focused on the mechanisms of action of prebiotics and probiotics but did not address postbiotics. Additionally, some experimental studies investigated postbiotic administration in humans but did not explore the underlying mechanisms of these metabolites.

For this reason, articles that met the inclusion criteria and were cited in the reference lists of the selected studies were also included (manual cluster searching). This approach increased the total number of relevant records to 69 (

Figure 5). This increase can be attributed to the fact that many articles do not explicitly use the term postbiotic but instead describe the mechanisms of action of specific metabolites, such as bacteriocins, biosurfactants, or exopolysaccharides. This may be due to the novelty of the postbiotic concept, which was not formally defined by ISAPP until 2021 [

37]. As a result, many publications still refer to these compounds as bacterial metabolites rather than using this specific nomenclature.

Only 13 articles were found that evaluate the effects of postbiotic administration on canine health (

Table 1). Six of these studies used postbiotics derived from Saccharomyces cerevisiae, while the remaining eight administered metabolites of bacterial origin. Except for the studies by Tate et al. (2024) [

107] and Wilson et al. (2022) [

108], which were conducted in dogs with pruritic conditions, the others were performed on healthy dogs. Five of these studies exposed the animals to stressful or physically demanding conditions to compare changes in blood parameters between postbiotic-supplemented and non-supplemented dogs.

2.2. Meta-Analysis

Based on the 13 identified studies evaluating the effects of postbiotic administration in dogs, several meta-analysis were conducted on selected parameters assessed in these studies. These meta-analysis aims to (i) determine the average findings regarding the effects of postbiotics on canine health, (ii) identify parameters for which postbiotic effects remain inconclusive, and (iii) establish a foundation for future research in this field.

The parameters of interest included oxidative stress markers (superoxide dismutase, malondialdehyde), inflammation markers (pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines), cell-mediated immune response (levels of different T-lymphocyte subtypes), humoral immune response (immunoglobulin concentration), fecal characteristics (fecal score, pH, and concentrations of specific molecules such as short-chain fatty acids, phenol, indole, and ammonia), and gut microbiota composition. However, due to the high heterogeneity in experimental design among the 13 studies, only a subset of parameters—fecal characteristics and gut microbiota composition—had sufficient data for meta-analysis. Among the 13 studies, only two measured different types of lymphocytes and immune cells [

105,

108], two studies analyzed immunoglobulin levels [

105,

113], two measured cytokine levels [

105,

106], and two quantified oxidative stress markers [

105,

108].

Table 2 presents the parameters included in the meta-analysis and the respective studies from which data were extracted. Regarding fecal characteristics, the meta-analysis compared findings from different studies on fecal score, fecal pH, and the fecal concentrations of short-chain fatty acids (acetate, propionate, and butyrate), branched-chain fatty acids (isobutyrate, isovalerate, and valerate), phenol, and indole. However, fecal ammonia concentration could not be analyzed, as only two studies reported data for this parameter [

105,

112].

Regarding intestinal microbiota, the meta-analysis focused on alpha diversity (expressed as richness and the Shannon index) and the abundance of the most important phyla in the canine gut microbiota (Fusobacteria, Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Proteobacteria).

Alpha diversity consists of richness and evenness, from which various indices can be calculated, such as the Shannon index (H) or Faith’s phylogenetic diversity index [

7]. Although these indices provide a more comprehensive analysis of alpha diversity, only the Shannon index could be examined across three studies [

107,

112,

113], whereas richness (expressed as the number of detected operational taxonomic units [OTUs]) could be compared across five studies [

105,

107,

112,

113,

116].

The abundance of bacterial phyla, expressed as the percentage of each phylum relative to the total bacterial population, was analyzed based on four studies [

105,

107,

112,

116]. While additional studies among the 13 identified articles assessed microbiota composition, they used different measurement units, such as the logarithm of colony-forming units (CFU) [

111] or changes relative to baseline [

113].

For all the parameters specified above, the mean levels obtained from different studies were analyzed for both the control group and the postbiotic-supplemented group. Additionally, differences between both groups were examined to determine the effect of postbiotic use on these parameters.

The statistical analysis was conducted using Jamovi software (version 2.6.23). To analyze the mean levels of each parameter for both groups (control and supplemented), heterogeneity among studies was assessed using the Q test (statistical significance set at p < 0.05). Publication bias was also evaluated using the Fail-Safe N analysis, Egger’s test, and Begg and Mazumdar Rank Correlation Test (statistical significance set at p < 0.05).

Regarding the analysis of differences between groups (control vs. supplemented), both heterogeneity (Q test, p < 0.05) and publication bias (Fail-Safe N, Egger’s test, and Begg and Mazumdar Rank Correlation Test, p < 0.05) were assessed. Additionally, a random-effects model was applied to determine statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) between groups for each parameter.

3. Type of Postbiotics

3.1. Short-Chain Fatty Acids

Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) are primarily derived from the fermentation of polysaccharides by intestinal bacteria. Prebiotics (mainly FOS, MOS, and inulin) serve as fermentation substrates for these microorganisms, leading to SCFA production [

38]. However, these postbiotics can also be synthesized from protein-based substrates, such as low-molecular-weight peptides [

39].

SCFAs include acetic, propionic, and butyric acids, as well as their corresponding salts (acetate, propionate, and butyrate) [

40]. Although their concentration varies throughout the intestine, the highest levels are found in the colon [

41]. In feces, acetic acid accounts for 60% of SCFAs, while propionic and butyric acids each represent 20% [

40]. These postbiotics are primarily produced by lactic acid bacteria, including

Lactobacillus acidophilus,

Lactobacillus fermentum,

Lactobacillus paracasei ATCC 335, and

Lactobacillus brevis [

42].

Among the three, butyrate is the most significant due to its role as an energy source for enterocytes, supporting proper intestinal epithelium renewal and reinforcing intestinal barrier function [

41]. Butyrate also possesses anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties, primarily by inhibiting the transcription factor NF-κB1 [

43].

Both butyrate and, to a greater extent, propionate serve as substrates for hepatic gluconeogenesis [

41] and exhibit antineoplastic activity, promoting apoptosis of malignant cells in the intestine [

44] (

Figure 6). These two molecules also play a role in erythropoiesis by enhancing duodenal iron absorption. This effect is mediated through the inhibition of hypoxia-inducible factor 2α (HIF2α), which regulates the production of ferroportin, duodenal cytochrome b, and divalent metal transporter 1 [

45,

46].

On the other hand, acetate has been shown to increase insulin sensitivity in humans [

47] and improve resistance to enterohemorrhagic

Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection, while simultaneously reducing intestinal epithelial permeability to the toxins produced by this bacterium [

48].

3.2. Cell Wall Fragments

The bacterial cell wall is composed of a wide variety of proteins, phospholipids, peptidoglycans, glycoproteins, and other molecular components [

49]. Some of these components, when isolated as cell wall fragments, have been shown to exert beneficial effects on intestinal microbiota and overall mammalian health. This includes teichoic and lipoteichoic acids, which account for approximately 60% of the cell wall mass in Gram-positive bacteria, making them one of their predominant components [

50]. These molecules exhibit immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory effects in the host. By interacting with Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) on host immune cells, these compounds reduce interleukin-12 (IL-12) production while increasing the secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-10 (IL-10). They also decrease levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), a pro-inflammatory cytokine induced by lipopolysaccharides [

51,

52].

Another cell wall-derived molecule of interest as a postbiotic is peptidoglycan. This molecule is recognized by NOD-like receptors (NLRs), specifically NOD1, and NOD2, expressed on dendritic cells. Through this interaction, peptidoglycan promotes the maturation and proliferation of CD4+ T lymphocytes, which in turn downregulate pro-inflammatory cytokine production, exerting an anti-inflammatory effect [

52].

This category of postbiotics also includes surface-associated bacterial peptides. Some of these peptides reinforce epithelial barrier function in enterocytes, while others reduce the intestinal absorption of heavy metals or exhibit anti-inflammatory and anti-adhesive properties against specific pathogenic bacteria [

53].

3.3. Exopolysaccharides

Exopolysaccharides are large carbohydrate molecules composed of either repeating units of a single type of monosaccharide (homopolysaccharides) or multiple types of monosaccharides (heteropolysaccharides) [

54]. Bacteria can synthesize these macromolecules, which accumulate on their surfaces and play key roles in cellular communication and adhesion, thereby contributing to biofilm formation [

55,

56]. Exopolysaccharides produced by lactic acid bacteria (

Lactococcus,

Leuconostoc,

Streptococcus,

Pediococcus, and

Bifidobacterium) are widely used in the food and pharmaceutical industries due to their stabilizing and emulsifying properties [

57,

58]. However, these compounds have also been shown to provide health benefits when used as postbiotics.

These substances stimulate immune responses, as they are recognized by dendritic cells and macrophage receptors, promoting the proliferation of natural killer (NK) cells and T lymphocytes [

59]. Some of these molecules enhance macrophage phagocytic activity and induce the secretion of nitric oxide (NO)

in vitro [

60]. Additionally, exopolysaccharides exhibit anti-inflammatory properties by reducing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α) while increasing IL-10 secretion, an anti-inflammatory cytokine [

61,

62].

In vitro studies have demonstrated that bacterially derived polysaccharides exert antibacterial effects, as their presence has been shown to inhibit the growth of various pathogenic bacteria, including

Escherichia coli,

Staphylococcus aureus,

Bacillus subtilis, and

Salmonella typhimurium, among others [

63,

64,

65]. Moreover, exopolysaccharides have also exhibited antitumor and antioxidant properties in cell culture models [

66].

A key example of an exopolysaccharide is polysaccharide A (PSA), which is recognized by TLR2 receptors on CD4+ T lymphocytes. This recognition promotes the differentiation of these lymphocytes into FoxP3+ regulatory T cells, which produce IL-10. Additionally, PSA has been shown to inhibit the Th17 pro-inflammatory response and restore Th1/Th2 immune balance (the balance between cellular immune response and humoral immune response) in murine models [

67].

3.4. Bacteriocins

Bacteriocins are bacterially derived peptides with antimicrobial activity against bacteria that are not of the same strain as the bacteriocin-producing bacterium [

68,

69]. All bacterial species are capable of producing at least one type of bacteriocin [

69], and they protect themselves from the antimicrobial effects of their own bacteriocins by expressing specific immunity proteins encoded within the same operon as the bacteriocin they counteract [

70].

The most commonly used postbiotic bacteriocins are those produced by lactic acid bacteria (LAB). These bacteriocins are composed of 30–60 amino acids [

71], are thermostable, and typically do not undergo post-translational modifications [

72]. One of the most common mechanisms of action of LAB-derived bacteriocins is pore formation in the cell membrane of target bacteria, exerting an inhibitory effect at nanomolar concentrations [

73]. Additionally, many bacteriocins prevent biofilm formation through various mechanisms, including inhibiting pilus motility, reducing virulence factor expression, and interfering with quorum sensing—a bacterial communication system essential for biofilm development [

74].

Through these mechanisms, bacteriocins have been shown to effectively inhibit the growth of several major pathogenic bacteria, including

Staphylococcus aureus,

Proteus spp.,

Enterococcus spp.,

Pseudomonas aeruginosa,

Escherichia coli,

Salmonella spp.,

Clostridium difficile, and

Klebsiella pneumoniae [

75,

76]. Furthermore, these compounds have demonstrated efficacy against multidrug-resistant strains of

S. aureus,

Salmonella spp., and

E. coli, suggesting their potential as alternatives to conventional antimicrobials for infection control [

72,

76].

In this regard, in vitro administration of LAB-derived bacteriocins to multidrug-resistant

Enterococcus faecium cultures has demonstrated inhibitory effects on bacterial growth. Moreover, the combined use of these postbiotics with tetracycline resulted in a synergistic effect, enhancing bacterial growth inhibition [

77]. Similarly, postbiotics derived from

Lactobacillus casei,

Lactobacillus plantarum, and

Lactobacillus salivarius—commensal bacteria found in wild boars (

Sus scrofa)—were shown to inhibit the in vitro growth of

Mycobacterium bovis, the pathogen responsible for tuberculosis, whose primary reservoir is wild boars. These findings highlight the potential role of bacteriocins in infection control within their host organisms [

78].

LAB-derived bacteriocins generally exhibit a narrower spectrum of activity than antibiotics, meaning that beneficial bacteria within the host's gut microbiota remain unaffected by their antimicrobial action. This represents a key advantage over traditional antimicrobials, as their use does not lead to gut dysbiosis [

79]. Although toxicity studies in mammals have not yet been conducted,

in vitro studies have shown that high concentrations of bacteriocins do not exhibit cytotoxic effects on eukaryotic cell cultures, suggesting that bacteriocins, as postbiotics, can help eliminate pathogenic bacteria without harming host enterocytes or negatively impacting commensal gut bacteria [

79].

3.5. Organic Acids

The most common bacterially derived organic acids include acetic, citric, tartaric, malic, and—most notably—lactic acid. These molecules exert antimicrobial effects by acidifying the surrounding environment, which inhibits bacterial growth by reducing intracellular pH and disrupting bacterial membrane integrity [

80,

81]. Under these acidic conditions, non-tolerant bacteria expend significant amounts of energy attempting to expel protons from their cytoplasm, ultimately leading to cell death [

82].

The most commonly used bacterium for organic acid production is

Lactobacillus plantarum, which can synthesize both D- and L-isomers of lactic acid. In

in vitro cultures, the organic acids produced by

L. plantarum have demonstrated inhibitory effects on pathogenic bacteria, such as

E. coli and

Salmonella spp. [

83]. Therefore, the use of these postbiotics appears to promote gut health by acting as antimicrobial agents.

3.6. Biosurfactants

Biosurfactants are surface-active macromolecules synthesized by bacteria, which are either released into the extracellular environment or remain attached to the bacterial surface. These compounds exhibit amphiphilic properties, containing both a hydrophobic and a hydrophilic region, allowing them to position themselves at the interface between fluids with different polarities, such as intestinal water and the lipid membranes of bacteria or enterocytes. Bacterially derived biosurfactants are commonly glycolipids, polysaccharides, phospholipids, glycopeptides, and glycoproteins, with varying structural complexity depending on their monomer composition and branching [

84,

85].

Due to their ability to interact with bacterial and cellular membranes, biosurfactants prevent pathogenic bacteria from colonizing the intestinal epithelium, hinder biofilm formation, and disrupt pre-existing biofilms, thereby promoting gut health [

86,

87].

Moreover, protein-based biosurfactants, derived from microbial synthesis, possess an amino acid balance close to that of an ideal protein, providing the host with high biological value proteins. This contributes to growth, tissue maintenance, and repair in the host organism [

88].

3.7. Enzymes

Bacteria can produce a wide variety of enzymes, among which antioxidant enzymes stand out, including catalase, glutathione peroxidase (GPx), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and NADH oxidase [

41].

In vitro studies have demonstrated that lactic acid bacteria, such as

Lactobacillus fermentum, exhibit antioxidant effects by reducing hydroxyl radical formation through the synthesis of these enzymes [

41,

89] (

Figure 7).

Antioxidant enzymes neutralize free radicals generated during the normal metabolism of both bacterial and eukaryotic cells, as well as those produced by certain pathogenic bacteria as virulence factors. In this way, these enzymes exert antioxidant effects, protecting lipid membranes, proteins, carbohydrates, and nucleic acids from oxidative damage caused by free radicals [

41,

89].

Since oxidative stress is pro-inflammatory, its reduction can lead to decreased inflammation. Therefore, beyond their antioxidant activity, these enzymes also exhibit anti-inflammatory effects in the host. For instance, the administration of postbiotics derived from

Lactobacillus plantarum has been shown to increase serum GPx levels in ruminants [

90]. Additionally, in murine models, the use of

Lactobacillus strains producing SOD and catalase improved clinical signs associated with chronic intestinal disease and Crohn’s disease [

91,

92].

3.8. Other Metabolites

In addition to the postbiotics previously mentioned, bacteria produce a wide range of metabolites that also exhibit postbiotic activity. One such example is vitamins, which cannot be synthesized by the host but are essential for maintaining overall health, as they play key roles in numerous physiological functions [

93].

Folic acid (vitamin B9) is one of the vitamins produced by bacteria used for postbiotic production and plays a crucial role in DNA synthesis, repair, and methylation, while also being recognized for its antioxidant properties [

41]. Another noteworthy vitamin is cyanocobalamin (vitamin B12), which is essential for proper hematopoiesis and neural health [

94]. Studies have shown that supplementation with postbiotics derived from

Lactobacillus acidophilus increases serum levels of vitamins B9 and B12, reducing the anemia prevalence in humans [

95].

Similarly, vitamin K is essential for blood coagulation, bone health, and neuronal function, whereas riboflavin (vitamin B2) plays a key role in redox reactions as a hydrogen carrier. All these vitamins are synthesized by lactic acid bacteria and

Bifidobacterium species, making them promising candidates for use as postbiotics to promote host health [

87,

93].

Bacteria used for postbiotic production also synthesize aromatic amino acids, which are bioactive compounds that influence organs beyond the intestine, including the brain, kidneys, and heart [

96]. These molecules have shown beneficial effects in mice with chronic kidney disease [

97].

Another key group of postbiotics includes polyphenols, such as urolithin A, equol, and 8-prenylnaringenin. Administration of urolithin A in mice for 10 weeks has been shown to reduce obesity and insulin resistance [

98]. In humans, polyphenols have been associated with improved mitochondrial health, enhanced fatty acid oxidation, increased serum acylcarnitine levels [

99], and greater bone density, particularly in postmenopausal women [

100].

Additionally,

Lactobacillus plantarum,

Lactobacillus brevis, and

Bifidobacterium species synthesize several neurotransmitters, including serotonin, acetylcholine, and catecholamines (primarily dopamine and norepinephrine). These postbiotic molecules are involved in numerous neurological processes, such as mood regulation, motor control, memory, and learning [

87,

101].

Another molecule of particular interest is tryptophan, an amino acid and a precursor of serotonin. Tryptophan is degraded via the kynurenine pathway, which, when dysregulated, has been associated with inflammatory, neurodegenerative, depressive, and tumor-related processes in humans [

45]. Furthermore, tryptophan is essential for protein synthesis and cell growth, influencing erythropoiesis. A 10% increase in tryptophan levels has been reported to raise hemoglobin and ferritin levels by 1.59% and 6.45%, respectively, thereby enhancing red blood cell production [

102].

4. Mechanisms of Action and Health Effects in Dogs

4.1. Immunomodulatory Action

In

in vitro studies and murine models, numerous postbiotic compounds have been shown to regulate immune system cells. For example, peptidoglycan promotes the maturation and proliferation of CD4+ T lymphocytes [

52]. Exopolysaccharides enhance the functions of antigen-presenting cells, improve macrophage phagocytic activity, and promote the proliferation of T and NK lymphocytes [

60]. Additionally, polysaccharide A (PSA) is recognized by CD4+ T lymphocytes, helping to restore the balance between cell-mediated and humoral immune responses [

67].

A significant proportion of geriatric dogs suffer from chronic diseases, which can lead to chronic oxidative stress and accelerate cellular aging, including that of immune cells. This process negatively impacts immune responses by reducing the CD4+:CD8+ T lymphocyte ratio—resulting in decreasing activation of CD4+ helper T cells and an increase in CD8+ cytotoxic T cells population. Consequently, immunosenescence, or aging of the immune system, disrupts the balance between Th1 and Th2 responses, making the host more susceptible to infections [

103,

104].

In a study conducted by Wambacq et al. (2024) [

104], a postbiotic supplement containing short-chain fructooligosaccharides (scFOS) derived from yeast was administered to healthy geriatric dogs to evaluate its effects on their immune system. The supplemented dogs showed lower serum IgA concentrations compared to the control group, suggesting that the postbiotic promoted greater local IgA immune responses in mucosal tissues. Furthermore, supplemented dogs exhibited a higher CD4+:CD8+ T lymphocyte ratio, indicating that scFOS supplementation may help counteract T-cell immunosenescence in dogs.

In another study [

105], the administration of fermentation products from

Saccharomyces cerevisiae to healthy adult dogs increased the population of monocytes, antigen-presenting B lymphocytes (MHC class II+ B cells), helper T cells, and IFN-γ-producing cytotoxic T cells compared to the control group. Dogs that received the postbiotic also exhibited higher serum IgE levels. Additionally, immune cells extracted from these dogs produced lower levels of TNF-α when stimulated with Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists targeting TLR2, TLR3, TLR4, and TLR7/8.

In dogs exposed to stress factors (such as daily physical exercise and transportation), supplementation with postbiotics derived from

Saccharomyces cerevisiae helped modulate immune responses, preventing significant alterations during recovery from exercise and stressful periods. The use of these products prevented an increase in blood leukocyte counts, particularly lymphocytes and eosinophils [

106].

Atopic dermatitis is a chronic inflammatory and pruritic skin disease that affects 10–15% of dogs. This condition is associated with environmental allergens and tends to manifest more severely in body areas with higher allergen exposure. Affected dogs often exhibit elevated IgE levels, and additional factors such as skin barrier defects, oxidative stress, secondary infections, immune system disorders, and gut microbiota alterations also contribute to the disease pathogenesis [

100].

In a study by Tate et al. (2024) [

107], researchers evaluated a supplement containing probiotics (Lactobacillus rhamnosus, Bifidobacterium bifidum, Bifidobacterium infantis, Bifidobacterium animalis, Lactobacillus acidophilus, and Lactobacillus casei), prebiotics (mannan-oligosaccharides and fructooligosaccharides), and a postbiotic obtained from Saccharomyces cerevisiae fermentation. The supplement was administered for 10 weeks to dogs with atopic dermatitis, and clinical improvements were assessed using the Pruritus Visual Analog Scale (PVAS10) and the Owner-Administered Skin Allergy Severity Index (OA-SASI), based on the Canine Atopic Dermatitis Extent and Severity Index (CADESI-4). Compared to the control group, supplemented dogs exhibited greater and earlier improvements in PVAS10 and OA-SASI scores, with PVAS10 values reaching normal ranges within four weeks in many cases.

In another study [

108], researchers administered a 10-week supplementation of fermentation products from

Saccharomyces cerevisiae to dogs with atopic dermatitis. By the end of the study, compared to the control group, supplemented dogs exhibited reduced transepidermal water loss in the ear region, higher sebum concentration, lower blood levels of activated T lymphocytes, and higher serum concentrations of the antioxidant enzyme superoxide dismutase (SOD). These findings led to clinical improvements in dogs with atopic dermatitis, suggesting that postbiotic supplementation may serve as a valuable adjunctive therapy for managing this condition.

4.2. Anti-Inflammatory Action

Postbiotics have demonstrated anti-inflammatory effects through various mechanisms. For example, butyrate inhibits the NF-κB1 transcription factor [

43], while cell wall fragments and polysaccharide A (PSA) are recognized by TLR2 receptors, reducing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-12 and TNFα) and increasing anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10) [

51,

52,

67]. Similarly, exopolysaccharides promote IL-10 production while decreasing IL-1β, IL-6, and TNFα levels [

61].

In a study where postbiotics derived from

Saccharomyces cerevisiae were administered to dogs under stress [

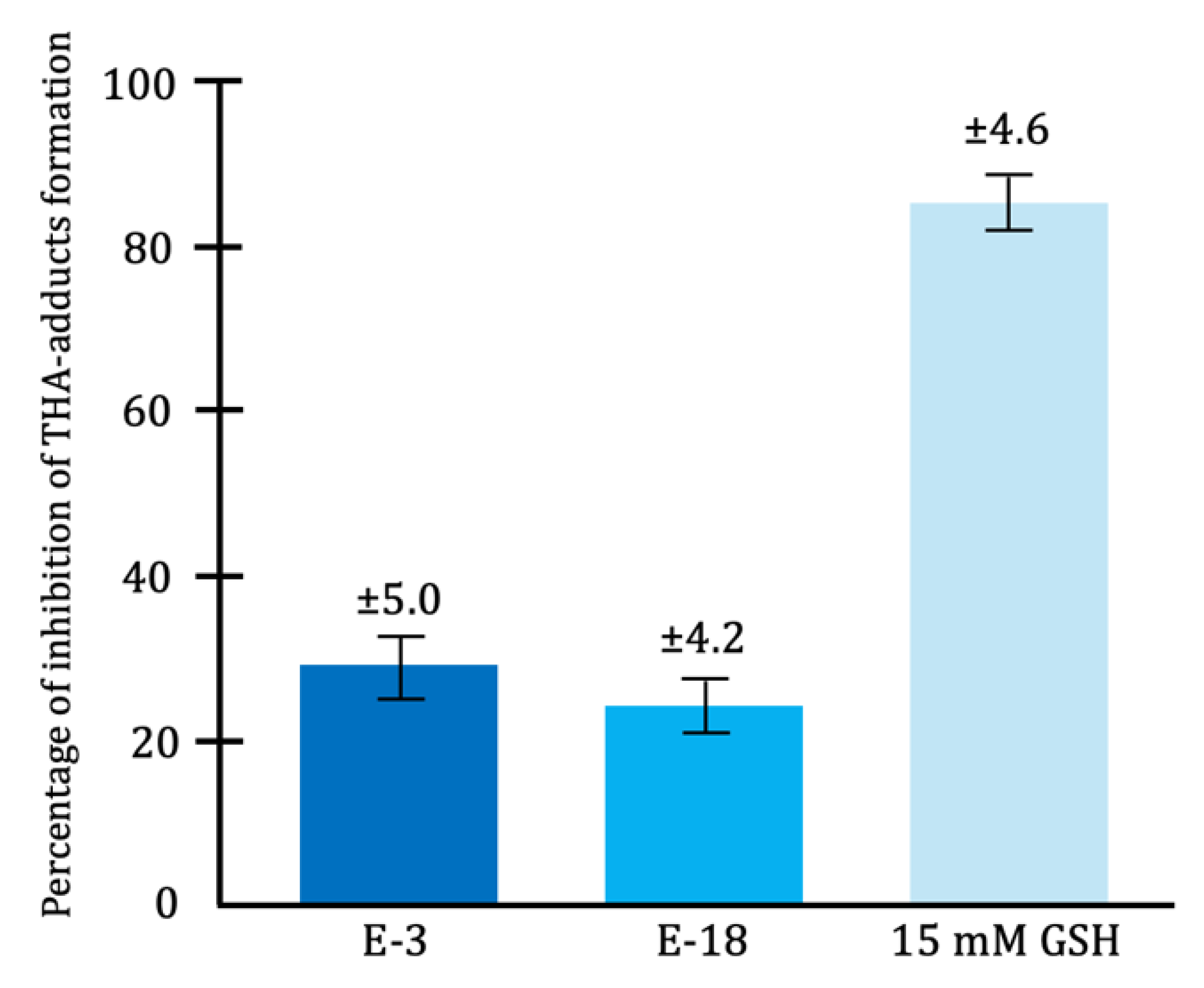

106], the supplemented group showed higher IL-10 levels (an anti-inflammatory cytokine) and maintained stable levels of IL-8 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (both pro-inflammatory cytokines). In contrast, the control group experienced an increase in these pro-inflammatory cytokines following the stressful event. Similarly, Xuan et al. (2024) [

109] reported reductions of 7.85%, 23.97%, and 29.54% in serum levels of immunoglobulin G, TNFα, and interleukin-1, respectively, in adult dogs supplemented with postbiotics (

Figure 8).

4.3. Modulatory Effects on the Gut Microbiota

Through different mechanisms, postbiotics can modulate the composition and diversity of the gut microbiota, which in turn impacts host health. In in vitro studies, the use of a postbiotic derived from

Limosilactobacillus reuteri NBF 1 led to an increase in Lactobacillus spp. and Bifidobacterium spp.—bacteria beneficial to the host due to their ability to ferment prebiotics and produce short-chain fatty acids. This postbiotic also enhanced the populations of

Bacteroides spp.,

Prevotella spp.,

Porphyromonas spp.,

Staphylococcus spp., and Enterobacteriaceae family (including genera such as

Escherichia spp.,

Salmonella spp.,

Shigella spp.,

Citrobacter spp.,

Enterobacter spp.,

Erwinia spp.,

Klebsiella spp., and

Proteus spp.) [

110].

Belà et al. (2024) [

111] administered the same postbiotic derived from

Limosilactobacillus reuteri NBF 1 to sled dogs during competition to compare microbiota composition changes before and after the race in both the control and supplemented groups. After exercise, dogs receiving the postbiotic showed a lower increase in

E. coli and

Streptococcus spp.—bacteria considered enteropathogenic and indicators of dysbiosis. Conversely, these dogs exhibited a higher increase in bacteria from the genera

Faecalibacterium,

Turicibacter,

Blautia, and

Fusobacterium, as well as

Clostridium hiranonis. These bacteria contribute to short-chain fatty acid production, providing health benefits to the host [

111].

Similarly, administering fermentation products from Saccharomyces cerevisiae to physically stressed dogs increased

Turicibacter spp. and

Lactobacillus spp. populations compared to the control group, along with a reduction in

Clostridium spp. [

112]. Other studies have also shown that

S. cerevisiae fermentation products positively affect gut microbiota composition. In stressed dogs, supplementation with this type of postbiotic increased

Clostridium hiranonis populations while reducing

Fusobacterium spp. and

Blautia spp. [

106]. Another study found that

S. cerevisiae fermentation products increased

Bifidobacterium spp. abundance while reducing

Fusobacterium spp. [

105].

Tate et al. (2024) [

107] investigated the use of this postbiotic in dogs with atopic dermatitis and found an increase in beneficial bacteria from the Firmicutes phylum, alongside a reduction in pathogenic bacteria from the Proteobacteria phylum. There was also an increase in Lachnospiraceae, a bacterial family involved in short-chain fatty acid production and intestinal barrier integrity, which is typically reduced in dogs with atopic dermatitis. Additionally, these dogs exhibited a rise in

Weissella spp. (mainly

W. cibaria and

W. confusa), which appear to support the recovery of patients with skin and allergic diseases.

Koziol et al. (2023) [

113] evaluated postbiotics derived from

Limosilactobacillus fermentum and

Lactobacillus delbrueckii in adult dogs. After five weeks, supplemented dogs showed greater alpha diversity, with increased counts of bacteria from the Actinobacteriota phylum and the genera

Faecalibaculum spp.,

Bifidobacterium spp., and

Butyricicoccaceae spp. However, the control group exhibited a higher increase in

Peptoclostridium spp.,

Sarcina spp., and

Faecalitalea spp. In a similar study, postbiotic supplementation boosted the abundance of beneficial bacteria like

Lactobacillus spp. and

Bacillus spp., while reducing harmful bacteria such as

Fusobacterium spp. and

Anaerobiospirillum spp. [

109].

4.4. Antimicrobial Action

Postbiotics are effective in treating bacterial infections, offering a promising alternative to antibiotics in response to the increasing development of antimicrobial resistance [

77]. The most important postbiotics with antimicrobial activity include bacteriocins, organic acids, and biosurfactants. These molecules, particularly bacteriocins, exert antimicrobial effects through various mechanisms, such as cell wall lysis, interference with quorum sensing, inhibition of biofilm formation, reduction of bacterial adhesion to the intestinal epithelium, and lowering intestinal pH [

73,

74,

80,

81,

82,

86,

87].

In adult dogs, supplementation with postbiotics derived from

Bifidobacterium animalis subsp.

lactis CECT 8145 fermentation led to a decrease in intestinal pH to 5.8, compared to 6.1 in the control group. This reduction is beneficial, as it inhibits bacteria that cannot tolerate low pH environments [

114]. Kayser et al. [

115] compared fecal properties among three groups of dogs: those receiving live

Bifidobacterium animalis subsp.

lactis CECT 8145 (probiotic), those supplemented with inactivated

Bifidobacterium animalis subsp.

lactis CECT 8145 (postbiotic), and an unsupplemented control group. Similar to the previous study, the feces of dogs receiving the postbiotic exhibited a lower pH and a higher concentration of propionate, which was associated with a healthier gut microbiota composition.

4.5. Antioxidant Action

The concept of postbiotics also includes bacterial enzymes, many of which have antioxidant properties, such as catalase, glutathione peroxidase (GPx), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and NADH oxidase [

41,

89]. In a study involving adult dogs, supplementation with fermentation products from

Saccharomyces cerevisiae over 10-weeks increased serum concentrations of SOD and catalase [

108]. Another study in adult dogs showed that administering a postbiotic supplement derived from

Limosilactobacillus fermentum and

Lactobacillus delbrueckii for five weeks resulted in a greater increase in serum superoxide dismutase levels compared to the control group [

113].

4.6. Other Effects of Postbiotics

Bacteria produce a wide range of bioactive molecules and metabolites with postbiotic activity, many of which play roles in various metabolic processes. For example, in mice, postbiotic supplementation has been shown to reduce obesity and insulin resistance [

98].

In dogs, supplementation with postbiotics has been associated with a 51.16% reduction in serum triglyceride levels, a 29.92% decrease in cholesterol levels, and an 11.43% decline in uric acid levels [

109]. Furthermore, in dogs exposed to stressful events, supplementation with

Limosilactobacillus fermentum and

Lactobacillus delbrueckii resulted in smaller fluctuations in serum levels of corticosteroid isoenzyme alkaline phosphatase and alanine aminotransferase [

113]. Additionally, dogs receiving postbiotics derived from

Bifidobacterium animalis subsp.

lactis CECT 8145 exhibited lower plasma concentrations of pancreatic polypeptide [

114].

5. Meta-Analysis

Conducting a meta-analysis in a new research area is essential, to know less evaluated aspects and to give a context for future research. It allows us to combine findings from the existing studies, highlighting areas that require further investigation, aspects that need to be evaluated in detail, and different methodologies to follow. The main limitation is the small number of studies, which could produce biases, being important to have into account. However, a meta-analysis in an early-stage topic, as is the use of postbiotics in dogs, is an essential step to determine further research.

5.1. Fecal Parameters

Table 3 presents the results of mean value, heterogeneity (Q-test) and publication bias (Fail-Safe N, Begg and Mazumdar Rank Correlation, and Egger’s Regression) for all fecal parameters in both the control and postbiotic-supplemented groups. Additionally,

Table 4 displays the estimated effects of postbiotic administration when comparing both groups, along with heterogeneity and publication bias results.

As shown in these tables, despite the limited number of studies included in the meta-analysis, no statistically significant results (p > 0.05) were found regarding heterogeneity or publication bias for any fecal parameter, except for fecal butyrate concentration. This suggests that, except for this specific case, the results were homogeneous across studies, and no publication bias was detected, with no outliers or influential studies affecting result stability.

No significant differences (p > 0.05) were observed between the two groups for any fecal parameter. Regarding the fecal score, none of the analyzed studies [

105,

112,

116] reported significant differences between groups. This may be because these experiments involved only clinically healthy dogs in both groups, all of whom had normal fecal scores at baseline. This stability in fecal scores is expected, as variations occur tipycally in pathological conditions, such as diarrhea or food allergies [

117,

118].

Although some postbiotic molecules, such as organic acids, lower the pH of their environment [

80,

81], the meta-analysis did not detect significant differences in fecal pH between groups. Among the analyzed studies [

105,

112,

115,

116], only Kayser et al. (2024) [

115] observed significant differences in fecal pH. This study administered postbiotics for the longest duration (90 days compared to 21 days in the other studies), suggesting that prolonged supplementation may be required to acidify the intestine and alter fecal pH.

Similarly, no statistically significant differences were found between groups regarding fecal concentrations of various compounds, including short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs: acetate, propionate, and butyrate), branched-chain fatty acids (BCFAs: isobutyrate, isovalerate, and valerate), indole, and phenol. When analyzing individual studies, significant changes related to postbiotic use were observed only in the reduction of fecal phenol and indole concentrations [

105] and the increase in propionate levels [

115].

SCFAs are produced by bacterial fermentation of polysaccharides in the gut [

38], while BCFAs, indole, and phenol result from proteolytic fermentation by gut microbiota [

116]. Postbiotic products contain these molecules, which, upon reaching the intestine, can be utilized by gut bacteria to complete metabolic pathways. For instance, SCFAs are rapidly absorbed by enterocytes, as they serve as their primary energy source. This utilization of fermentative products by both intestinal bacteria and epithelial cells may explain the lack of changes in fecal concentrations of these compounds following postbiotic administration [

119].

5.2. Gut Microbiota

Table 5 presents the results of mean value, heterogeneity (Q-test) and publication bias (Fail-Safe N, Begg and Mazumdar Rank Correlation, and Egger's Regression) for all parameters related to gut microbiota in both the control and postbiotic-supplemented groups. Likewise,

Table 6 shows the estimated effect of postbiotic administration on these parameters by comparing both groups, as well as the heterogeneity and publication bias results.

Similar to the fecal parameters, despite the low number of studies included in the meta-analysis, no statistically significant results (p > 0.05) were found regarding heterogeneity and publication bias for any of these parameters, except for the abundance of the Fusobacteria and Firmicutes phyla. This suggests stability in the results.

Regarding alpha diversity (richness and Shannon index), the meta-analysis does not reveal significant differences between the control group and the postbiotic-supplemented group. However, when analyzing each study individually, greater statistical significance (p < 0.10) was observed in experiments where the postbiotic was administered for a longer period (5 weeks [

113] and 10 weeks [

107]), compared to the three weeks of supplementation in the other studies [

105,

112]. This suggests that a longer supplementation period with postbiotics is necessary to observe changes in alpha diversity. Additionally, in the study by Tate et al., 2023 [

107], where dogs with atopic dermatitis were used, postbiotic supplementation appeared to produce significant changes in the microbiota compared to healthy animals with a normal microbial population.

No statistically significant differences were detected in the relative abundance of any of the major phyla in the canine gut microbiota (Fusobacteria, Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Proteobacteria). Two of the four studies included in this meta-analysis [

112,

116] did not detect significant changes in phylum abundance following supplementation. In contrast, Tate et al., 2023 [

107], observed a significant increase in the Firmicutes phylum and a decrease in the Proteobacteria phylum. Meanwhile, Lin et al., 2019 [

105], detected a significant increase in the Actinobacteria phylum and a reduction in the abundance of the Fusobacteria phylum.

Across these four studies, significant changes were observed in several bacterial genera, particularly an increase in genera associated with SCFA production and a decrease in the abundance of pathogenic bacteria such as Klebsiella pneumoniae or Streptococcus pasteurianus. However, due to the heterogeneity in the genera studied across studies, a meta-analysis at the genus taxonomic level could not be performed.

The lack of significant results in the meta-analyses indicates that there is still no clear answer regarding the use of postbiotics in dogs, signaling the need of future research on this key topic. Our findings also provide insight into which parameters would be worth evaluating, highlighting the microbial composition of the gut, and suggesting that to find clear answers, future research should primarily focus on experimental studies in diseased individuals.

6. Production and Presentation Forms of Postbiotics

The production of postbiotics from bacterial or fungal populations is not a recent development. In the food industry, particularly in dairy products, fermentative processes using lactic acid bacteria are very common. However, in this type of fermentation, neither the quantity nor the type of postbiotics produced is controlled, making their health effects on consumers less evident. For this reason, industrial postbiotic production typically involves the use of biofermenters. These are tanks with several liters of capacity in which optimal conditions are established for the growth of the target bacterial strain: aerobic or anaerobic conditions, a temperature suitable for the species, and a nutrient-rich substrate necessary for its development (proteins, polysaccharides, etc.) [

94].

The most used species in postbiotic production belong to the genera

Lactobacillus,

Streptococcus,

Bifidobacterium,

Eubacterium,

Saccharomyces, and

Faecalibacterium [

94]. During the fermentation process, these microorganisms produce a wide variety of bioactive postbiotic compounds, such as short-chain fatty acids, organic acids, exopolysaccharides, and proteins. Furthermore, through biofermentation processes, it is possible to control both the type and concentration of postbiotics produced by adjusting incubation time, the type of fermentation substrate, and the bacterial strain used. As a result, products obtained through this method have demonstrated anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and immunomodulatory properties in the host consuming these postbiotics [

41,

120,

121].

Once the fermentation process is complete, postbiotics can be extracted in different ways. One type of product is cell-free supernatant (CFS), a liquid containing the metabolites produced during microbial fermentation and soluble nutrients that were not consumed, but without cellular debris. Therefore, CFS contains fatty acids, organic acids, and protein molecules that exert antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antitumor effects on the consumer [

41,

122].

Another method of postbiotic production involves inactivating the microorganisms used in biofermentation. Various bacterial cell wall lysis techniques can be employed for this purpose, such as enzymatic lysis, heat lysis, sonication, or high-pressure lysis [

123]. These treatments allow for the extraction of not only soluble metabolites but also intracellular metabolites and bacterial structural components, resulting in what is known as bacterial lysates [

94,

124].

Once obtained, postbiotics can be marketed in liquid form or, more commonly, in solid form, typically as lyophilized (freeze-dried) products [

125]. The viability of these products can be affected by various environmental factors, such as humidity, storage temperature, or oxidation. Therefore, it is essential to apply specific techniques to ensure their stability. For solid products, capsules with a semi-permeable coating are used to isolate postbiotic substances from external conditions and ensure their release at a specific point in the gastrointestinal tract. These coatings are usually made from plant-based biopolymers (e.g., cellulose, pectin, gum arabic, alginate, inulin, etc.), animal-based biopolymers (e.g., chitin, hyaluronic acid, etc.), or microbial-origin polymers (e.g., xanthan, dextran, gellan gum, etc.). Proteins from animal sources (e.g., caseins, albumins, whey proteins, etc.) or plant sources (e.g., soy or pea protein) may also be used. For liquid products, UV-protected glass containers are commonly used to prevent solar radiation penetration. Emulsions can also be used to help stabilize the product [

126].

7. Future Perspectives

The meta-analysis conducted in this study did not yield a statistically significant expected effect from the use of postbiotics on fecal parameters and gut microbiota composition. Although the statistical tests performed to assess heterogeneity and publication bias did not show significant values (p > 0.05), it is important to note that the different meta-analyses carried out for each parameter were based on only 2-4 studies. It would be advisable to have more studies available to validate these results. In most of these studies, postbiotics were administered to healthy dogs for approximately three weeks. However, when these products were administered to sick dogs [

107] or over a longer period (about 9-12 weeks) [

107,

115], the effect of postbiotics showed greater statistical significance in the analyzed parameters. Additionally, some authors suggest that higher doses of postbiotics may be neccesary to better evaluate their effects in these cases [

112,

116].

From the systematic literature review, not enough studies (only one or two examples) were found to conduct a meta-analysis on other parameters, such as specific bacterial genera, inflammatory markers, or cellular and humoral immune responses. Furthermore, there is a lack of studies evaluating the evolution of blood test results (hematology, biochemical panel) in dogs supplemented with postbiotics. Therefore, it would be beneficial to conduct further research on postbiotic supplementation in dogs, particularly in those suffering from intestinal or immune-mediated diseases, to measure not only fecal and microbial parameters (analyzing variations in the abundance of major bacterial families and genera) but also immune, inflammatory, and serological markers. Moreover, these studies should be conducted over periods longer than three weeks and with higher doses of postbiotics.

Despite these limitations, available results from both in vitro experiments and studies in humans and other animal species demonstrate the potential benefits of these compounds. Postbiotics have been shown to improve gastrointestinal health through various mechanisms of action, such as their anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects, antimicrobial activity, and ability to regulate gut microbiota composition. However, due to the close relationship between the gut and the rest of the body, as well as the absorption of some of these bacterial metabolites, postbiotics may also enhance the health of other organs, including the kidneys, heart, nervous system, skin, and joints [

17,

18,

19,

20,

41,

94,

110,

111].

As a result, postbiotics represent a promising tool for treating common canine diseases, such as gastrointestinal disorders (acute diarrhea or chronic inflammatory bowel disease [IBD]), inflammatory and immune-mediated conditions (atopic dermatitis, osteodegenerative disease, food allergies, bacterial infections, parasitic diseases, etc.), kidney diseases, metabolic and endocrine disorders (primarily diabetes), and behavioral disorders. Although preliminary results on their effects in healthy dogs are limited, future research should focus on patients with the aforementioned conditions.

Postbiotics also offer a promising solution in the fight against antimicrobial resistance. This is mainly due to the activity of bacteriocins produced by certain bacterial strains, which have been shown to effectively inhibit the growth of major pathogenic bacteria, such as

Escherichia coli and

Salmonella spp. Furthermore, the use of these compounds in combination with antibiotics has demonstrated a synergistic effect in the treatment of infections caused by multidrug-resistant bacteria [

70].

A common practice in small animal clinics is the administration of probiotics alongside antibiotics to reduce the harmful effects of antibiotics on gut microbiota, preventing intestinal dysbiosis. However, most bacterial species used as probiotics have been shown to be susceptible to common antibiotics. Therefore, their co-administration with antibiotics remains controversial, as antibiotics inhibit probiotics, preventing them from exerting their regulatory effect on gut microbiota composition [

127]. In contrast, the activity of postbiotics is not diminished by antibiotics. This is because postbiotics are already synthesized bacterial compounds, meaning their concentration and efficacy are not reduced by antimicrobial molecules, allowing them to be effective in reducing dysbiosis caused by antibiotic administration [

113]. Additionally, since probiotics are composed of live bacteria, they colonize the host’s intestine and can exchange genetic material with resident bacteria through horizontal gene transfer. This poses a risk for the transfer of antimicrobial resistance genes, as studies have already demonstrated the presence and transfer of such genes from probiotic bacterial strains to commensal bacteria [

128]. In contrast, because postbiotics are bacterial components or non-viable bacteria, they do not exchange genetic material with the host's gut microbiota [

41].

The exclusive administration of postbiotics offers numerous advantages for improving canine well-being and treating various diseases. However, their use in combination with conventional treatments for certain conditions could be particularly interesting, as a synergistic effect is expected. Combining postbiotics with prebiotics and probiotics could also enhance their beneficial effects, as seen in symbiotics. For example, both postbiotics and probiotics have been shown to reduce the severity of skin lesions in dogs with atopic dermatitis, suggesting that their combined administration could have a synergistic effect in these cases [

107,

108,

129,

130].

In addition to their numerous benefits for overall health and specific organs and systems, postbiotics are considered safe for administration. None of the reviewed studies on postbiotic use in humans or animals reported any adverse effects. Moreover, bacteria commonly used for postbiotic production have received Qualified Presumption of Safety (QPS) status, as they are generally regarded as posing no health risks. In many cases, the genomes of these bacteria are sequenced to search for resistance or virulence genes. Therefore, although further safety and toxicity studies are necessary, the use of these compounds appears to be safe [

93].

For these reasons, further development in the field of postbiotics is highly valuable, both in terms of their production and the development of new strains capable of producing these metabolites, as well as in the formulation of various food products containing them. By expanding research on their effects on overall health and exploring their potential combination with pharmaceutical treatments or other bioactive components (prebiotics and probiotics), postbiotics may aid in the management and treatment of chronic diseases affecting a significant portion of the pet population, such as osteoarthritis, atopic dermatitis, diabetes, and IBD.

8. Conclusions

This systematic literature review explores the different types of postbiotics, their mechanisms of action, and the effects of their administration on canine health. These microbial-derived substances help regulate the immune system, inflammatory response, and gut microbiota composition, which in turn influences overall health and aids in the management of various systemic diseases. The meta-analysis conducted did not yield statistically significant results regarding the use of postbiotics. This lack of significant results highlights the novelty of the research field and the need for further investigation, given the potential importance of postbiotics in canine health. Further research is recommended to explore the application of postbiotics in sick dogs, establishing administration guidelines for the treatment of various diseases, investigate their potential in combination with other bioactive compounds, such as prebiotics or probiotics.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14886968, Figure S1 to Figure S17: Forest Plot of the estimated effect of postbiotic administration (difference from the control group) for every parameter studies in the meta-analysis (fecal score; fecal pH; fecal concentration of acetate, propionate, butyrate, isobutyrate, isovalerate, valerate, indole, and phenol; richness; Shannon Index, and relative abundance of Fusobacteria, Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Proteobacteria phyla).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Beatriz Isabel Redondo and Paloma Maria Garcia Fernandez; methodology, Paloma Martinez-Alesón García; software, Javier Pineda-Pampliega and Diego Paul Bonel Ayuso; validation, Jesús de la Fuente, Beatriz Isabel Redondo and Paloma Maria Garcia Fernandez.; formal analysis, Diego Paul Bonel Ayuso; investigation, Diego Paul Bonel Ayuso; resources, X.X.; data curation, Montserrat Fernandez-Muela; writing—original draft preparation, Diego Paul Bonel Ayuso; writing—review and editing, Beatriz Isabel Redondo, Javier Pineda-Pampliega, Paloma Maria Garcia Fernandez, and Jesús de la Fuente; visualization, Montserrat Fernandez-Muela; supervision, Beatriz Isabel Redondo, Paloma Maria Garcia Fernandez, and Jesús de la Fuente; project administration, Beatriz Isabel Redondo; funding acquisition, Beatriz Isabel Redondo. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by DEHELIFE PROJECT CDTI-ABS 20230188.

Review and Meta-analysis Statement

The Systematic Literature Review was not registered. Information regarding the protocol used for conducting the literature review can be found in the Materials and Methods section (

Section 2). For further details related to the systematic review or the meta-analysis, please refer to the

Supplementary Materials or contact

dbonel@ucm.es.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are openly available in Veterinary Sciences at [DOI or link]. Researchers and interested parties are encouraged to utilize these data for further analysis and replication studies. If additional information is required, the corresponding author can be contacted at

dbonel@ucm.es.

Acknowledgments

This work was made possible thanks to the financial support provided by the DEHELIFE PROJECT CDTI-ABS 20230188. We deeply appreciate the trust placed in this research, as well as the technical and administrative support received.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SCFA |

Short-Chain Fatty Acids |

| BCFA |

Branched-Chain Fatty Acids |

| TLR |

Toll-like receptor |

| IBD |

Inflammatory bowel disease |

| LPS |

Lipopolysaccharide |

| AMR |

Antimicrobial resistance |

| ENS |

Enteric nervous system |

| CNS |

Central nervous system |

| MOS |

Mannan-oligosaccharides |

| FOS |

Fructooligosaccharides |

| ISAPP |

International Scientific Association of Probiotics and Prebiotics |

| IL |

Interleukin |

| TNF-α |

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| GPx |

Glutathione peroxidase |

| SOD |

Superoxide dismutase |

| THA |

Terephtalic acid |

| GSH |

Reduced glutathione |

References

- Yang, Q.; Wu, Z. Gut Probiotics and Health of Dogs and Cats: Benefits, Applications, and Underlying Mechanisms. Microorganisms 2023, 11(10), 2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, I.; Gibson, G.; Heinken, A.; Scott, K.; Swann, J.; Thiele, I.; Tuohy, K. Gut microbiota functions: metabolism of nutrients and other food components. Eur. J. Nutr. 2017, 57(1), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilla, R.; Suchodolski, J.S. The Role of the Canine Gut Microbiome and Metabolome in Health and Gastrointestinal Disease. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomaa, E.Z. Human gut microbiota/microbiome in health and diseases: a review. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2020, 113(12), 2019–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manor, O.; Dai, C.L.; Kornilov, S.A.; Smith, B.; Price, N.D.; Lovejoy, J.C.; Gibbons, S.M.; Magis, A.T. Health and disease markers correlate with gut microbiome composition across thousands of people. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinross, J.M.; Darzi, A.W.; Nicholson, J.K. Gut microbiome-host interactions in health and disease. Genome Med. 2011, 3(3), 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kers, J.G.; Saccenti, E. The Power of Microbiome Studies: Some Considerations on Which Alpha and Beta Metrics to Use and How to Report Results. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente, J.C.; Manasson, J.; Scher, J.U. The role of the gut microbiome in systemic inflammatory disease. BMJ 2018, j5145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvallet, C.; Gibbons, S.M.; Gurry, T.; Irizarry, R.A.; Alm, E.J. Meta-analysis of gut microbiome studies identifies disease-specific and shared responses. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Zhao, H.; Wu, L.B.; Cheng, Z.; Liu, C. Impact of the microbiome on human, animal, and environmental health from a One Health perspective. Sci. One Health 2023, 2, 100037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]