Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by cognitive decline and memory loss. With AD being a popular condition worldwide, and the limited effectiveness of treatment, it’s vital to emphasize the urgent need for alternative, modifiable interventions. Despite advances in research into its pathophysiology, the mechanisms driving AD progression and its modifiable interventions remain poorly substantiated [

1]. One critical factor in AD pathogenesis is the phosphorylation of tau proteins (TP), which leads to a rapid formation of neurofibrillary tangles [

2]. Tau protein, abundantly found in Alzheimer’s disease patients, is still common in those who may not be diagnosed with the condition [

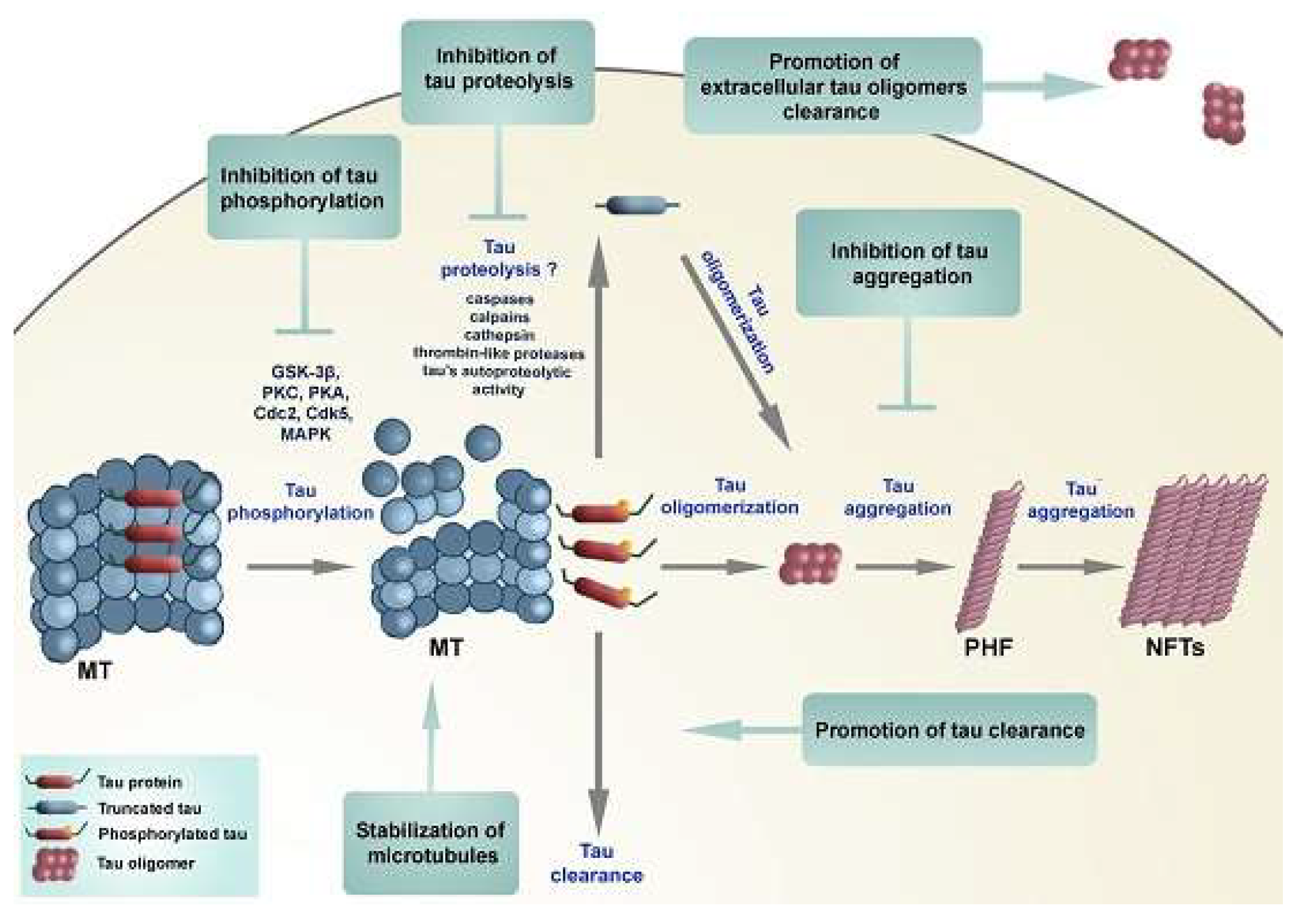

3]. The protein plays a crucial role in neurons by stabilizing microtubule structures. However, TP becomes problematic when hyperphosphorylated, causing significant damage to microtubules, initiating one of the key progression pathways of AD (

Figure 1). Increasing activation of phosphatases (enzymes that remove phosphate groups from proteins) may counteract the phosphate activity in TP and result in a more gradual progression of the disease.

Researchers are looking towards modifiable lifestyle factors, such as diet and exercise, to prevent the progression of AD to the farthest extent and mitigate the role age and genetics play in AD development. Dietary interventions, including modifications to both nutrient intake and meal frequency, may play a crucial role in influencing the progression of AD by impacting key biochemical pathways. One such pathway could be the process of activating phosphatases to minimize phosphate bonding in TP. Previous studies [

4] reveal that magnesium is an essential mineral in many biochemical processes, including the activation of certain phosphatases. For instance, it has been demonstrated that magnesium levels are notably lower in the brains of patients with mitochondrial cytopathies, and supplementation has been shown to improve oxidative phosphorylation. Magnesium deficiency has been linked to increased inflammation and oxidative stress, which could potentially inhibit phosphatase activity. Existing research [

5] concluded that magnesium supplementation can restore optimal levels of magnesium in the brain, thereby reducing the deleterious effects of oxidative stress and inflammation. This may facilitate the activation of phosphatases, which could regulate tau phosphorylation and prevent phosphate bonding in TP. Therefore, ensuring a magnesium-rich diet would ideally promote proper regulation of phosphates. Based on these findings, we hypothesize that magnesium supplementation can play a role in regulating tau phosphorylation, potentially slowing AD progression.

In addition to sufficient intake of nutrients, another preliminarily explored dietary intervention is intermittent or irregular fasting (IF). Research has proven that IF has been shown to increase levels of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) [

6], a protein that plays a critical role in promoting neuronal growth, enhancing synaptic plasticity, and supporting overall brain function. Elevated BDNF levels may activate signaling pathways that support phosphatase activity. Furthermore, studies indicate that when fasting, especially when irregular, the body undergoes metabolic changes to adapt to the sudden caloric restriction. Promoted BDNF and metabolic changes have been proven to initiate the activation of pathways that can influence phosphatases [

7], such as protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), which is directly involved in the dephosphorylation of tau proteins [

8]. We suggest that IF’s increase in BDNF levels could lead to an acceleration of PP2A enzymatic processes in the brain, potentially mitigating tau phosphorylation and slowing the progression of neurodegeneration associated with AD. The novel combination of magnesium supplementation and IF may work synergistically to amplify the regulatory processes affecting tau phosphorylation.

Previous studies of magnesium and IF corresponding to AD have been conducted on mice [

9,

10], but the exact correlation of these interventions in humans, their relation to phosphatases in TP, and how they complement each other are still yet to be investigated. This proposal aims to confirm the hypothesis that combining magnesium supplementation in diets with intermittent fasting will enhance phosphatase activity and reduce tau phosphorylation in individuals with early-stage AD. ANOVA statistical software will be used to analyze the data collected from cerebrospinal fluid and glucose levels, helping to assess whether the combination of magnesium supplementation and intermittent fasting impacts phosphatase enzymatic activity in TP significantly, in order to be considered a valid dietary intervention for AD. The findings from this study could lead to simple dietary-based interventions that are practical, more accessible, and affordable for AD patients, ultimately alleviating the burden they face and contributing to improved management strategies.

Methodology

This randomized controlled clinical trial will be conducted with participants who are diagnosed with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease (AD), with the age range of 55-80 years. Participants will be required to have documented evidence of tau pathology, as confirmed by PET imaging with tau tracers, such as flortaucipir or tau-PET, showing elevated binding in regions typically affected by AD (e.g., the entorhinal cortex or hippocampus). All participants will be required to provide informed consent prior to enrollment, ensuring they fully understand the study’s procedures, potential risks, and benefits. Participants will be given the opportunity to ask questions and will be assured that they can withdraw from the study at any time without penalty. Participant confidentiality will be strictly maintained throughout the study, with all personal and medical information stored securely and only accessible to the research team. Identifiable data will be anonymized in reports and publications to ensure privacy and compliance with HIPAA and other relevant ethical guidelines [

12].

A power analysis will be conducted using G*Power software to determine the appropriate sample size for this study. Based on an expected medium effect size (Cohen’s f = 0.28) [

13], an alpha level of α = 0.05, n = 4 groups, and a desired power of 1 - β = 0.80, the analysis should indicate that a sample size of approximately 32 per group would be sufficient to detect significant differences between groups. To account for potential attrition, a total of 200 participants will be recruited, ensuring the study will provide reliable results. Participants will be individuals diagnosed with Alzheimer’s exhibiting tau pathology (p-tau+), selected randomly from consenting adults through medical paperwork at local hospitals. PET/MRI scans will be used to confirm AD in all. The participants will be randomly assigned to one of four groups (50 per group) using stratified randomization, ensuring balanced representation of demographics [

13]. To control for varying baseline magnesium levels, all participants will follow a low-magnesium diet for one week prior to beginning the study interventions, providing a consistent starting point for magnesium intake across all groups. The first group will be regarded as the control group (G1, control), in which the participants would continue with a standard diet (containing a normal 3-meal schedule with a calorie intake range of 2,000 - 2500 kcal per day [

14]) with no magnesium supplementation or fasting. The second group (G2) would be dedicated to only intermittent fasting (IF), utilizing the 16:8 method, and will not be given magnesium supplements. The 3rd group (G3) will be the magnesium group with a daily magnesium intake of 320 mg per day for females and 420 mg per day for males (aligning with the recommended dietary magnesium intake for adults [

15]) with a standard diet. Finally the fourth group (G4) would be a combination of both the magnesium intake method and the IF 16:8 method. The study will last for a duration of 2 years before the results will be compared to evaluate the effectiveness of the study and the impact of modifiable dietary interventions, including fasting and magnesium supplementation, on Alzheimer's disease progression.

To prove that the levels of tau phosphorylation in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and blood plasma is decreased by carrying out a lumbar puncture. The lumbar puncture will be performed to collect preliminary data to quantify changes in tau phosphorylation resulting from magnesium intake and intermittent fasting [

16]. The lumbar punctures are administered to everyone at the start, after six months, and in the end. To start the experiment we will be taking a baseline ELISA lumbar puncture test to administer the amount of hyperphosphorylated tau present in the CSF.

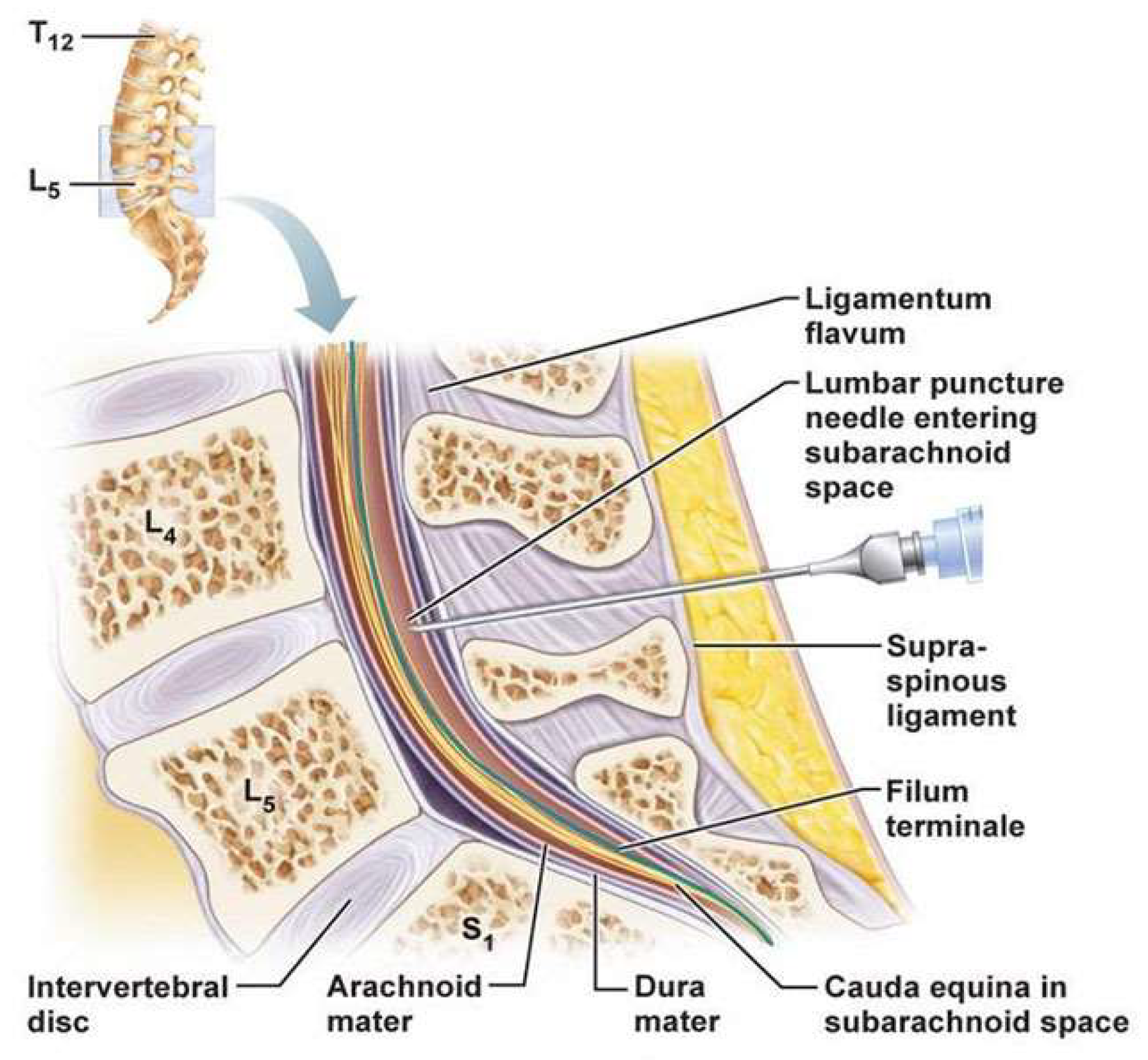

When administering the lumbar puncture, the participant will lie in a fetal position. A 1% concentration (10 mg per 1 mL) of lidocaine will be administered in a 0.45 mL / kg dose to the patient to decrease discomfort [

17]. Once the participant is under anesthesia, a sterile needle will be injected in the lumbar spine vertebrae in between L4-L5 to access the subarachnoid space where the CSF is present (

Figure 2). The injection will extract 15 mL of CSF with the sterile needle. The needle will be carefully taken out and the site will be bandaged and sanitized. Post procedure care will be administered to the participants, by ensuring proper hydration to avoid headaches. The CSF, handled with care to prevent contamination or protein degradation, will then be centrifuged to remove any debris or cells that would’ve been present in the 15 mL concentration. Finally, the CSF will be distributed into 5 mg each in 3 tubes so that the smaller volumes would avoid repeated freeze- thaw cycles. The liquid will also be kept at -80o Celsius till the product is used for ELISA. ELISA is used to quantify the amount of proteins in the brain, and for our experiment we are focusing on the availability of the specific hyperphosphorylated TP [

18]. First, we will start by diluting the anti-tau antibody into the Carbonate-Bicarbonate Buffer (pH 9.6 and serves as the coating buffer) [

19]. 100 µL of this diluted solution would be inputted in the well of the microplate. Then, let the plate incubate overnight at 4 degrees celsius, allowing for immobilization. Then, the coating will be removed by washing with PBS-T (PBS with Tween-20, 0.05–0.1%). The solution will then be introduced to a 200 µL BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin, 1–5%) as a blocking buffer to make sure unnecessary proteins aren’t being quantified instead of our target. After blocking with BSA, dilute the CSF samples to an appropriate concentration (1:10 by adding 900 µL of PBS) with the appropriate assay buffer. Add 200 µL of the diluted CSF solution into each well. Incubate this solution for 1 hour at room temperature. The plate will then be washed multiple times with PBS-T (PBS with Tween-20, 0.05 – 0.1%) to eliminate unbound detection of other materials that do not need to be quantified. Then we will add 100 µL of substrate solution and incubate in the dark for 15 minutes. Finally the reaction will be stopped by adding 50 µL, which will stop the color development. Now, the microplate reader will be put to 450 nm.

The intermittent fasting technique (16:8 method) will be used similarly for both G2 and G4. The 16:8 method restricts a participant to only 8 hours to intake necessary diet, and requires them to fast for the remaining 16. The 16:8 IF method was chosen, as it has been shown to be one of the most sustainable and effective approaches for improving metabolic health, regulating insulin sensitivity, and supporting neuroprotective pathways, while also being easier for older participants to adhere to over an extended period [

21]. Usually the time period that is assigned for food intake is anytime between 2 PM–8 PM, 10 AM–6 PM, or 1 PM–9 PM which depends on the participants' personal lifestyle and preferences. For this study, the research team will identify one of the three time periods at their discretion and require individuals to participate in IF every day for 24 months. During the 16 hour fasting period only black coffee, water, and tea is allowed. These tasks will be supported by our researchers, who will maintain a 1:5 researcher-to-participant ratio. The researchers will monitor participants and utilize fasting logs to track their progress. Rather than simply logging onto the fasting tracks, to make sure the fastings are showing moderate changes, the researchers will also attach wearable continuous glucose monitors (CGM) to the patients. These monitors will be attached to all patients, ensuring glucose variability data can be collected from all participants. However, this method will be specifically targeted towards G2 and G4, as they will practice IF. There will be a constant log of the glucose variability in fasting periods and post-meal periods (lower glucose variability will be interpreted as stronger metabolic health). This will allow us to have a real time monitor that is non-invasive with personalized insights throughout the fasting process.

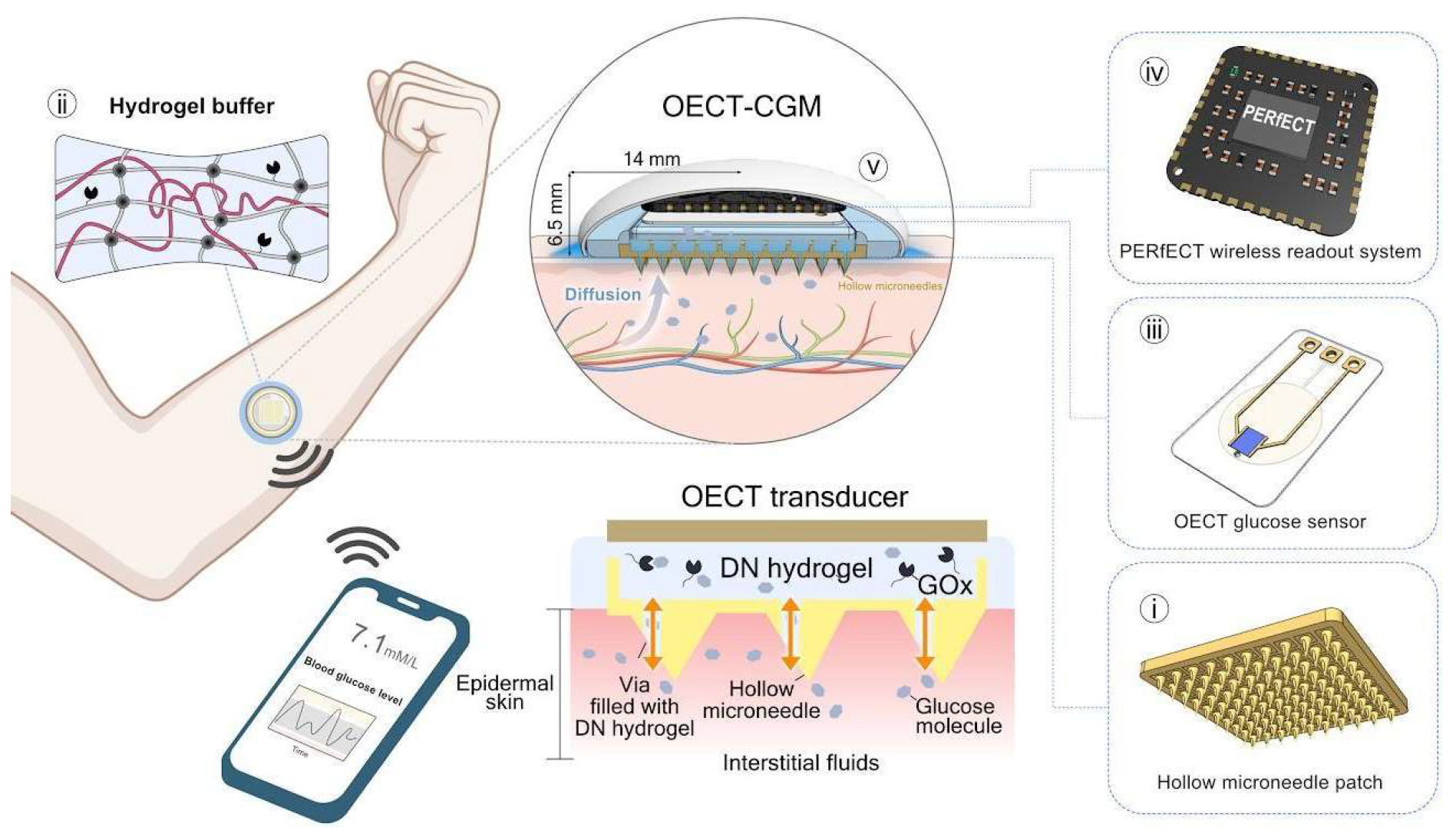

Figure 3.

The Concept and Design Principle of the OECT-CGM System.

Gives a visual presentation incorporating CGM onto the human body. This process is slightly invasive but will give significant data that will help us understand the IF and magnesium supplement combination on Alzheimer’s patients. [

22].

Figure 3.

The Concept and Design Principle of the OECT-CGM System.

Gives a visual presentation incorporating CGM onto the human body. This process is slightly invasive but will give significant data that will help us understand the IF and magnesium supplement combination on Alzheimer’s patients. [

22].

The magnesium supplement intake will be taken by G3 and G4. The doses of magnesium-L-threonate are administered orally in doses of 350 mg/day for 24 months. The supplements will be made sure to be taken after the first meal to maximize absorption. By utilizing CGM technology, we can determine the effectiveness of this method by recognizing how magnesium promotes a decreasing trend in fasting glucose levels and post-meal spikes. Minimal variability in glucose will signify a healthier metabolic status in participants.

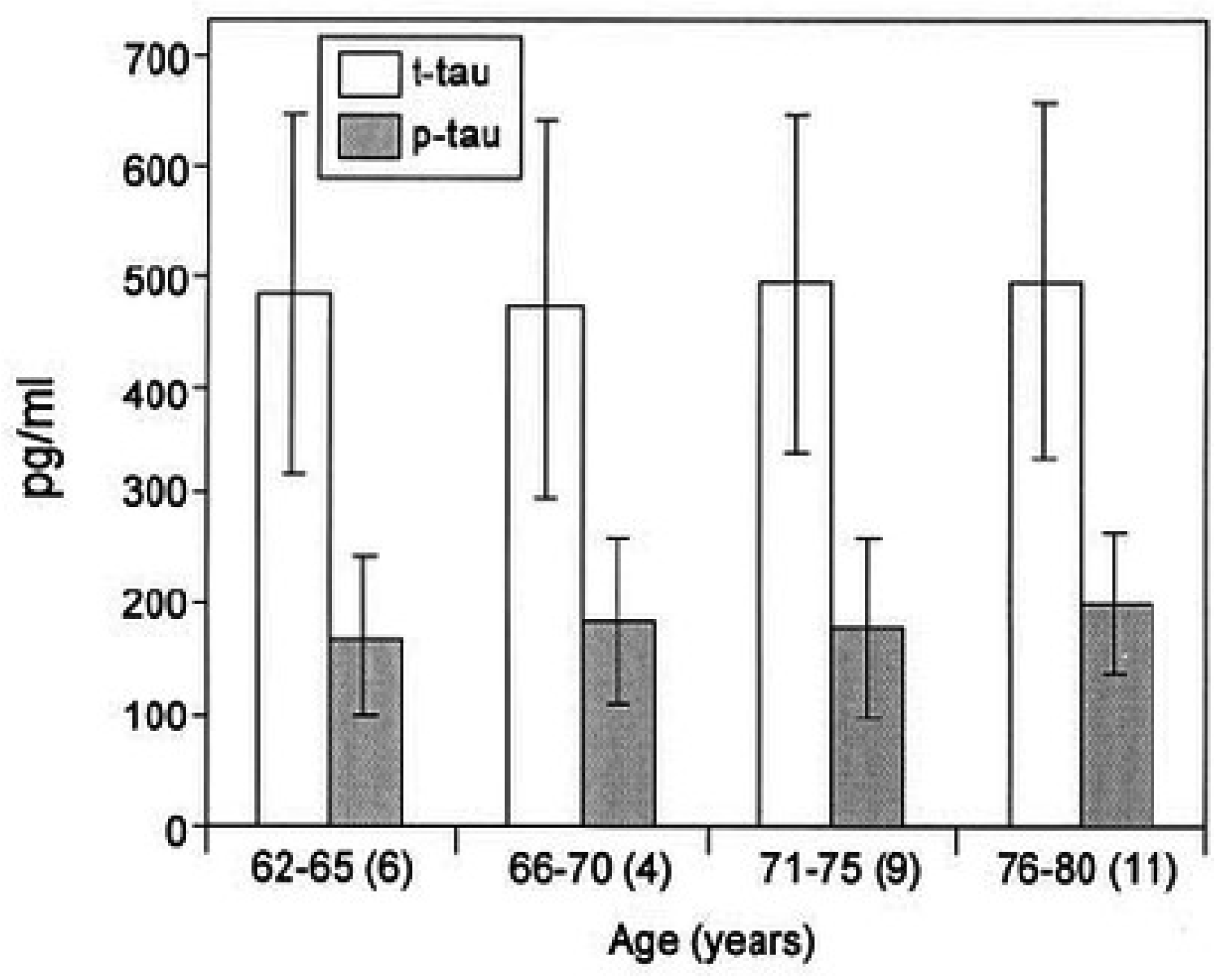

After collecting p-tau+ data from ELISA, we would then input it into the SPSS analytic software, applying the one way ANOVA test, where the group would be considered the independent variable and the p-tau intensity as the dependent variable. To analyze the data from the ANOVA, we will focus on the p-tau value from the F-statistic. A p-value less than 0.05 would indicate a significant difference between two groups. We will calculate the p-value difference between the statistical data of the ELISA tests from the p-tau quantities that are present. While reviewing the ANOVA test results, it is important to keep in mind that the data should maintain the same mean p-value throughout all demographic factors, to ensure it is not affected by the gender or average age of the participant group (utilize filter settings for certain demographic factors and check if the p-value changes) (

Figure 4). We will review the 12-month variation in glucose levels both before and after eating for each group. These datasets will provide insight into whether our hypothesis was accurate and positively impacted the results.

Hypothesized Results

To analyze the potential results of this study, several key parameters will be measured. The primary outcome could show the level of hyperphosphorylated tau (p-tau), quantified using ELISA (

Figure 4). A colorimetric response in the microplate will indicate the presence of p-tau+, with higher intensity corresponding to higher levels of tau phosphorylation. The optical density (OD) at 450 nm will be used to quantify the concentration of p-tau in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and blood plasma. A significant reduction in color intensity from baseline to post-intervention would most likely indicate a decrease in tau phosphorylation [

23]. The results will be analyzed using statistical tests such as ANOVA or t-tests, with a p-value of < 0.05 considered significant [

23].

Alongside tau measurement, we will also collect continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) data from participants in the IF groups to assess glucose variability during fasting and post-meal periods. The variability will be calculated using parameters such as the coefficient of variation (CV), with lower CV values indicating improved metabolic health. Participants in the magnesium + IF group (G4) are expected to show the greatest reduction in glucose variability [

25], supporting the hypothesis that magnesium enhances metabolic regulation alongside IF. These analyses will be performed using paired t-tests or repeated measures of ANOVA.

Mitochondrial function will also be assessed through appropriate assays, with improvements in mitochondrial health indicating neuroprotective effects of the dietary interventions. Statistical significance will be determined with a p-value threshold of < 0.05 [

23], and effect sizes will be calculated to determine the magnitude of the observed effects.

This study would provide compelling evidence that both magnesium supplementation and intermittent fasting (IF) can significantly reduce tau phosphorylation in individuals with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease (AD). The findings would support our hypothesis that dietary interventions can influence key biochemical pathways involved in AD progression, specifically by modulating tau phosphorylation. Our data is most likely to show notable reductions in hyperphosphorylated tau (p-tau +) levels in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and blood plasma in the groups that received either magnesium supplementation or IF, with the combined magnesium + IF group (G4) showing the most pronounced effects. These results align with prior studies [

26] suggesting that magnesium plays a crucial role in phosphatase activation, which may contribute to the dephosphorylation of tau proteins. Additionally, the potential neuroprotective effects of IF, particularly through the activation of BDNF and PP2A, further emphasize the value of this dietary approach [

4,

5].

Discussion

This study highlights the potential of magnesium supplementation and intermittent fasting as accessible and low-cost interventions to modulate tau phosphorylation and potentially slow the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. The combination of magnesium supplementation and IF also will have a significant impact on metabolic health, as will be evidenced by improved glucose variability and reduced fasting glucose levels in participants. This is consistent with previous studies that have shown magnesium's role in regulating glucose metabolism, insulin sensitivity, and overall metabolic function [

25]. Magnesium supplementation has been linked to reduced oxidative stress and inflammation, both of which are key contributors to the pathogenesis of AD [

27]. This will particularly be notable in the magnesium + IF group, which would suggest that the metabolic changes induced by IF, in combination with the neuroprotective effects of magnesium, may enhance the activation of phosphatases involved in tau dephosphorylation. The use of continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) should provide real-time data on glucose fluctuations, highlighting how these dietary interventions may stabilize metabolic processes that are linked to better neurobiological outcomes.

While these results are promising, there are limitations to consider. First, the relatively smaller sample size (200 participants) and the short duration of the study (24 months) require caution when generalizing the findings. Longer-term studies with larger participant pools are needed to confirm the durability of these effects and their broader applicability. Previous studies [

28] have shown that sample size and duration are critical factors in the generalizability of clinical trials, with larger cohorts and extended timelines offering more reliable and sustainable data. Furthermore, although the study focused on participants in the early stages of AD with tau pathology, it remains unclear how these interventions would affect individuals at later stages of the disease or those without tau pathology (A+, T-). Additionally, while our methodology included objective data from CGMs, adherence to the intermittent fasting regimen was reported manually through fasting logs by researchers, which could induce human error as mentioned by recent publications [

29]. Although the CGMs provided valuable metabolic data, future studies could benefit from incorporating more robust tracking methods, such as real-time tracking apps, to ensure consistent adherence and reduce the potential for bias. Future studies are open to explore the potential benefits of magnesium supplementation and IF in a wider range of AD stages and across diverse populations.

Looking ahead, further investigation is needed to better understand the molecular mechanisms that underlie the combined effects of magnesium supplementation and IF on tau phosphorylation. Research should focus on pathways involving phosphatases like PP2A and examine how these interventions may influence other AD-related biomarkers, including amyloid-beta plaques and neuroinflammation. Expanding the study to include a broader patient population, including individuals with mild cognitive impairment, and extending the duration of research will be critical to assessing the long-term efficacy of these interventions in mitigating disease progression.