1. Introduction

Principles and procedures from Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) are frequently used to produce socially relevant behavior change (Baer et al., 1968). Differential reinforcement practices, use of prompts and their subsequent fading to teach discrimination, among other measures, are commonly used, for example, to treat learners such as those diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and other cases of learning disabilities (Cooper et al., 2014). ASD frequently involve deficits in language and communication and the presence of stereotypic/repetitive behavior patterns (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2014). For cases of children and young people who require comprehensive specialized monitoring, a recommended format of ABA-based interventions to target multiple skill acquisition is called discrete trial teaching (DTT) (Lovaas, 1987; Souza & Ribeiro, 2023; Varella & Souza, 2018).

DTT is usually applied in a structured environment with control of possible distracting stimuli. When a trial to teach a skill is about to be administered, the interventionist first needs to evoke the learner’s attention and make sure that all necessary materials are available. When the instruction of the trial is provided, some seconds are allowed for the emission of a response by the learner. If the response is correct, a reinforcer is provided. If an error occurs (or no response is emitted during the allowed time), a correction procedure is applied. Prompts may also be used along the process to increase the likelihood of independent performance. The termination of the trial is followed by a brief interval until a new teaching trial is presented (Souza & Ribeiro, 2023; Varella & Souza, 2018).

In Brazil, the number of well-trained professionals is still not sufficient for the growing number of children with ASD who need intensive behavioral interventions (Ávila & Matos, 2023; Matos, Nascimento, et al., 2021). An alternative to this could be training parents and other caregivers to implement interventions to their children themselves, which is considered evidence-based practice (Schmidt et al., 2024). Leaf et al. (2017b) states that parent training increases the intensity of interventions and may promote improvements in the relationship with their children with ASD. However, involving caregivers in the process of implementing interventions through DTT (e.g., Ávila & Matos, 2023; Higgins et al., 2023) and other more naturalistic formats (e.g., Bagaiolo et al., 2017; Ferguson et al., 2022a, 2022b; Sena et al., 2024; Tsami et al., 2019) may not be an easy task in Brazil. Many families have a low socioeconomic status, the members spend many hours at work or on household chores and are many times unavailable to be trained (Ávila & Matos, 2023; Gomes et al., 2022). Training programs for a greater number of professionals are warranted to expand the possibilities of access to quality and lower-cost behavioral interventions for children with ASD, whose family members lack the time to be properly trained.

A recommended training package for people interested in carrying out behavioral interventions using a format such as DTT is called behavioral skills training (BST). It consists of four components: Didactic instructions to implement the interventions properly; modeling (two actors, representing interventionist and child with ASD, rehearse the implementation of DTT trials, or the trainer directly rehearses with a child); role-play (the person being trained implements DTT to a confederate/actor or child with ASD); performance feedback by the trainer concerning the correct or incorrect implementation of DTT. Research reveals that BST has been used in training professionals, university students and caregivers (e.g., parents) to implement DTT to learners with atypical development (Ávila & Matos, 2023; Clayton & Headley, 2019; Ferreira et al., 2016; Guimarães & Matos, 2024; Higgins et al., 2023; Lerman et al., 2008; Matos, Hübner, et al., 2021; Matos, Nascimento, et al., 2021; Sarokoff & Sturmey, 2004; Sarokoff & Sturmey, 2008; Souza et al., 2022).

In some of the investigations, during training, the participants always interacted directly with children with ASD and other cases of atypical development to teach repertoires (Clayton & Headley, 2019; Lerman et al., 2008; Sarokoff & Sturmey, 2004; Sarokoff & Sturmey, 2008). In other studies, the participants interacted during training with a confederate who pretended to be a child with ASD (Ferreira et al., 2016; Guimarães & Matos, 2024; Matos, Higgins et al., 2023; Hübner, et al., 2021; Matos, Nascimento, et al., 2021; Souza et al., 2022). Overall, in all studies shown, BST was successful in the sense that the participants, either professionals or university students, learned to teach several skills accurately. There were cases with evidence of generalization of accurate teaching of skills to children with ASD, based on training DTT rehearsal with a confederate (Higgins et al., 2023; Guimarães & Matos, 2024; Matos, Hübner, et al., 2021; Souza et al., 2022). In all studies, increases in performance accuracy (or teaching integrity levels) referred to the correct implementation of several DTT components (e.g., the interventionist evoked the learner’s attention; provided instruction consistently; specified the expected response and without repetition; reinforced only the learner’s correct response etc.) by each participant across the presentation of trials to teach repertoires. The more the components were implemented correctly, the more accurate the teaching of skills was.

Through the studies, verbal (Skinner, 1992), non-verbal and academic repertoire were successfully taught to children or confederates. However, it is important to emphasize that, in the investigations mentioned so far, the effects of BST training were not clearly investigated on the accurate teaching of multiple skills, that is, at least ten. According to Gomes et al. (2022), a greater number of programs, aimed at teaching several skills, may be a predictor of further gains in development. In this previous research, caregivers, who were trained to systematically teach at least ten different skills through DTT across a year, produced significant developmental gains for their children with ASD. So, one of the research questions of the new investigation consisted of the following: 1) Did BST effectively train university students to accurately teach multiple skills to a confederate pretending to be a child with ASD?

Plus, considering that the assessment of generalization is a predictor of the effectiveness of an intervention, once BST proved successful, the second research question consisted of the following: 2) Did BST training produce the generalization of accurate teaching of multiple repertoires, including new ones not covered in training, to children with ASD across post-training probes? Finally, considering that the previous studies did not clearly assess the impact of BST on performance accuracy by the university students and acquisition of repertoire by the children in the long term, that is across several months, the final research question consisted of the following: 3) After BST training and assessment of generalization proved successful, would the high teaching integrity levels by the university students, during the provision of DTT and acquisition of repertoire by the children, be demonstrated across four months on average?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Six undergraduate Psychology students (P1, P2, P3, P4, P5 and P6) participated in the research, with ages ranging between 20 and 23 years old. None of them showed previous experience with ABA-based interventions, including DTT, to children with ASD, which represented an inclusion criterion. Participants with previous knowledge would be excluded from the study. Six children with ASD (CD1, CD2, CD3, CD4, CD5 and CD6), aged between 5 and 9 years, also participated as learners in DTT-based interventions. They all received interventions once a week for 1 hour and 30 minutes in the university-based laboratory where data collection was carried out. To be eligible to participate, the children could not demonstrate severe behaviors related to hetero-aggression, self-injury and property destruction.

2.2. Environment

Data collection was carried out in a university laboratory room. It contained a table and two chairs. At different stages of the research, a confederate, who simulated behaviors of a child with ASD, sat on one of the chairs. Sometimes, either a Psychology student or an experimenter sat on the other chair, facing the confederate, to provide DTT trials. The experimenter conducted trials when he needed to demonstrate the correct teaching of skills. Each participating student conducted DTT trials under assessment and BST training conditions to establish more accurate teaching of repertoires to the confederate. In other situations, designed to measure generalization and maintenance of accurate teaching of repertoires over four months, each of the six children with ASD sat on the chair that previously accommodated the confederate.

2.3. Data Collection Instruments

Firstly, the definition of repertoires taught by the university participants was based on possible curricular goals commonly established to many learners diagnosed with ASD in a manual of ABA-based interventions (Matos, 2016). When the research began, the participants used recording sheets to measure skill gains attained by a confederate and children with ASD involved. The research team also used recording sheets to measure the correct and incorrect implementation among 11 possible DTT components, which could be demonstrated across the administration of each of ten trials per session to teach a given repertoire.

The 11 components were as follows: C1 - The participant kept the area free from distractions, removing unnecessary items from the table surface; C2 - the participant organized necessary materials such as pencil, recording sheet, stimuli cards and reinforcers to be within reach; C3 - the participant evoked behaviors that indicate attention such as eye contact and shoulders facing the interventionist; C4 - the participant waited for the emission of behaviors that indicated sustained attention for at least 2 seconds; C5 - the participant provided well-articulated and clear verbal instructions in a way that she did not use more than four words; C6 - the participant waited for a response from the learner for up to 5 seconds; C7 - if the learner emitted a correct response, the participant provided praise and access to an arbitrary reinforcer; C8 - if the learner emitted an incorrect response, the participant implemented a correction procedure; C9 - the participant recorded the learner’s response; C10 - the participant removed used stimuli before the provision of the next trial; C11 - the participant waited 5 seconds before starting the next trial.

Part of the stimuli used to teach repertoires by the university participants was organized in plastic cards, measuring 6 x 3cm. The cards comprised images representing several categories such as animals and transportation. Whenever a learner emitted a correct response across DTT trials, praised and access to a preferred game or toy were provided.

2.4. Dependent Variable and Independent Variable

In this investigation, the main dependent variable (DV) consisted of the number of DTT components implemented correctly by the university participants during the teaching of repertoires to confederate and child with ASD. As mentioned before, each participant could implement among 11 possible components during the provision of each teaching trial in a session. The independent variable (IV) consisted of the implementation of four BST training components (didactic instruction, modeling, role-play and performance feedback) by an experimenter. During BST role-play, across trials with the emission of correct responses by the confederate learner, the implementation of a correction component by the university participant was not possible.

Across trials with the emission of incorrect responses by the confederate, the implementation of a reinforcement component by the university participant was not possible. The data was organized in a percentage format per session, that is, the number of DTT components implemented correctly was divided by the total number of possible components, and the result was multiplied by 100. A secondary DV of the research consisted of the cumulative number of correct and incorrect responses emitted by six children with ASD across five months of DTT teaching sessions following the end of BST training.

2.5. Interobserver Agreement

Across many sessions involving most of the research conditions (baseline, BST training with immediate and delayed feedback, assessment of generalization and maintenance), data collection related to the DTT components implemented correctly and incorrectly by the participants was conducted by an experimenter and an independent researcher. This was done to establish agreement rates between the two observers. For each of the six university participants (P1, P2, P3, P4, P5 and P6) with whom IOA was obtained, agreement calculations were carried out by dividing the number of agreements by the number of agreements added to the number of disagreements and multiplied by 100 to obtain a percentage. The two observers showed agreement when they both recorded that a given participant either implemented DTT components correctly or incorrectly. For P1, IOA was obtained in 43.75% of the sessions and ranged between 96% and 100% (98% on average). For P2, IOA was obtained in 78.94% of the sessions and ranged between 90% and 100% (98% on average). For P3, IOA was obtained in 38.09% of the sessions and ranged between 94% and 100% (98% on average). For P4, IOA was obtained in 80% of the sessions and ranged between 44% and 100% (91% on average). For P5, IOA was obtained in 66,67% of the sessions and ranged between 93% and 100% (98% on average). For P6, IOA was obtained in 71,42% of the sessions and ranged between 82% and 100% (92% on average).

2.6. Experimental Design

The effects of the IV, BST, on the main DV, number of DTT components implemented correctly by the university participants, were investigated with a single case design consisting of nonconcurrent multiple baselines across participants (following recommendations by Cooper et al., 2014). Watson and Workman (1981) asserted that this design involves the observation of participants at different times. Data collection does not occur simultaneously. Baseline and intervention are set at different times for the participants.

In this study, six participants were allocated into two triads. Within each triad, the baseline condition was established first. Across sessions, each participant conducted sequences of ten trials to teach repertoires to a confederate. An experimenter took data on the correct and incorrect implementation of DTT components. After a low and stable performance was demonstrated, an intervention started for one participant, and the others remained in the baseline condition. The intervention involved the four components of BST in the following order: Didactic instructions about the repertoires to be taught, modeling (the experimenter rehearsed the correct implementation of DTT with the confederate), role-play (each university student conducted DTT trials with the confederate) and performance feedback provided by the experimenter per teaching trial across the sessions (immediate feedback).

Data on correct and incorrect implementation of DTT components was systematically collected during role-play as in baseline, but the experimenter programmed differential consequences for the participant’s performance. After an arbitrary learning criterion was demonstrated (two sessions with at least 90% of DTT components implemented correctly), another BST intervention condition was established. The only difference from the previous case was that performance feedback was delayed, that is, in each session, feedback was solely provided by the experimenter after the university participant administered the ten teaching trials to the confederate.

After the learning criterion was achieved, probe sessions were conducted to assess the generalization of teaching new skills to a child with ASD instead of the confederate. Then, a maintenance (follow-up) condition was defined for the university participant over four months in which she had the opportunity to teach multiple repertoires through DTT to a child with ASD based on his/her individualized curriculum goals. Throughout this period, skill gains by the child were measured (secondary DV) and three probe sessions, to assess the participant’s maintenance of accurate skill teaching, were conducted. Finally, a self-assessment questionnaire was administered to obtain measures of social validation of the research procedures by the participant.

For each triad, when the effects of the IV on the main DV were demonstrated by the first participant (improvement in teaching accuracy through BST with immediate feedback), BST training was also established for the second university participant, who also went through the remaining research conditions thereafter. Finally, when the second participant also showed improvement in performance accuracy through BST with immediate feedback, this condition and the others in the study were also implemented with the third participant. Everything that was done served the purpose of measuring experimental control, through the logic of the multiple baseline design, replicating the effects of interventions across different participants.

2.7. Ethical Procedures

This research was approved by the human research ethics committee of the Federal University of Maranhão (authorization 4.284.271). The six university students, the six children with ASD and those responsible for them signed an informed consent form. All personal information was confidential. The participants could remove their consent at any time, if they wished, without any harm.

2.8. Procedure

The study conditions were administered as follows:

Baseline. All university participants had access to part of a manual (Matos, 2016), a week before data collection, with the purpose of reading descriptions on how to conduct DTT to teach the following ten repertoires: Sitting still (e.g., the learner corrected his posture to an erect position while sitting and following the model provided by the interventionist); motor imitation (e.g., the learner clapped his hands based on the model provided by the interventionist); making requests (e.g., the learner said “can you give me juice?” in the presence of the interventionist); vocal imitation (e.g., the learner said “airplane” after the interventionist presented the verbal instruction “say airplane”); receptive identification of non-verbal stimuli (e.g., the learner pointed to the picture of a car in an array with several different pictures, and under the verbal instruction “point to the car” by the interventionist); making eye contact (e.g., the learner maintained eye contact with the interventionist for 10s upon request); following instructions (e.g., the learner raised his hands after the interventionist provided the verbal instruction “put your hands up”); intraverbal (e.g., the learner said “apple” after the interventionist presented the verbal stimulus “what do you eat?”); labeling (e.g., the learner said “cat” when the interventionist showed a picture of cat and asked “what is this?”); receptive identification of non-verbal stimuli by function, feature and class (e.g., the learner pointed to the picture of a tree in an array with several different pictures, and under the verbal instruction “show me something with leaves” by the interventionist).

When the baseline condition began, across sessions, each participant conducted ten DTT trials to teach the ten previously mentioned repertoires to a confederate, who pretended to be a learner with ASD. He followed scripts to randomly emit correct responses, incorrect responses and no response across trials. In each session, each trial corresponded to the teaching of a different repertoire. During baseline, the university participants did not receive feedback from the experimenter regarding their performance accuracy to teach skills. The termination criterion for this research condition consisted of demonstrating a low and stable performance of correct implementation of DTT components across sessions.

BST training with immediate feedback. The experimenter administered four BST components (didactic instruction, modeling, role-play, and performance feedback) to train each of the six university participants. During the first component, didactic instruction, classes on how to teach five of the previously mentioned repertoires in baseline (sitting still, motor imitation, making requests, vocal imitation and receptive identification of non-verbal stimuli) were given. The classes were organized in power point slides. The contents explained how to provide DTT instructions, reinforce correct responses and correct errors (or no response during an allowed time) committed by a possible learner. The didactic instruction component was administered just once and lasted 30 minutes on average. Modeling was, then, conducted. The experimenter and the confederate, representing interventionist and learner respectively, practiced ten DTT trials under a randomized order involving the five repertoires (two trials for each) for each participant to observe. The confederate followed scripts to emit correct responses, incorrect responses and failure to respond along the trials and the experimenter demonstrated the correct way to intervene on the confederate’s responses.

Thereafter, the role-play component was established and each participant had to teach the five repertoires across sessions of ten trials (two trials for each repertoire) in a randomized order to the confederate, who followed scripts to emit responses the same way as in the modeling component. After each trial administered across sessions, the experimenter provided feedback on the participant’s performance in implementing the DTT components. For those implemented correctly, verbal praise was delivered. For those implemented incorrectly, corrective feedback was provided, that is, the experimenter clarified what was wrong and demonstrated the correct way to intervene with the confederate. The termination criterion for this research condition consisted of two sessions with at least 90% of DTT components implemented correctly.

It is important to emphasize that it was only during the role-play component that the experimenter collected data on accurate teaching of repertoires (DTT components implemented correctly and incorrectly) by the university participants. In this research, the effects of each of the BST components were not investigated separately. It has been discussed in the literature that the development of a comprehensive training package, involving the use of all BST components together by the trainer, represents the best way to reduce integrity errors by participants interested in implementing ABA interventions to ASD, such as those based on DTT.

BST training with delayed feedback. This research condition was similar to the previous one. The only difference was that, during the role-play component through which each university participant taught five repertoires to the confederate, performance feedback by the experimenter on correct and incorrect implementation of DTT was delayed. In other words, for each session, feedback was provided solely after the administration of ten teaching trials by each participant. The termination criterion was the same as the one from the previous research condition.

Generalization assessment. In this condition, as in baseline, the university participants conducted ten DTT trials to teach repertoires along sessions, and no performance feedback was provided by the experimenter. As in baseline, the participants taught the same ten repertoires, one per trial in each session. As was said before, five of these repertoires (sitting still, motor imitation, making requests, vocal imitation and receptive identification of non-verbal stimuli) were involved in the training conditions through BST. The five remaining (making eye contact, following instructions, intraverbal, labeling and receptive identification of non-verbal stimuli by function, feature and class) were never used in training. Their teaching by the participants during the current research condition served as a way of assessing generalization of teaching integrity with new skills. In addition, across sessions, every participant taught a child diagnosed with ASD instead of a confederate. Therefore, generalization of teaching integrity was also assessed through the teaching of six children with ASD (one per university participant).

Maintenance of accurate teaching and monitoring skill gains by children with ASD. Two weeks after the previous conditions, each university participant taught a child with ASD (the same one from the previous generalization assessment condition) once a week on average across up to four months. The repertoires taught were directly related to the curricular goals of each child regardless of the research. Children’s progress in skills was systematically measured during this condition. In addition, three follow up probe sessions were conducted by the experimenter to assess the level of integrity of each university participant in teaching via DTT without performance feedback. The first session was conducted during the beginning of skills teaching for each child. The second session was conducted after the second month and, the third and last one, in the end.

Social validity assessment. The university participants rated the BST training by answering a Likert scale questionnaire. It consisted of six questions with alternatives ranging from “1”, meaning “I completely disagree”, to “5”, meaning “I completely agree”. The following questions were presented to each participant: 1) I enjoyed participating in the BST training; 2) I felt comfortable with the training process; 3) I learned important skills; 4) BST was effective for teaching children with ASD accurately; 5) I will continue to use the procedures I mastered to teach other skills to children with ASD; 6) I recommend the training to other interested people.

3. Results

Next, the percentages of DTT components implemented correctly by the six university participants (P1, P2, P3, P4, P5 and P6) involved the research conditions are presented.

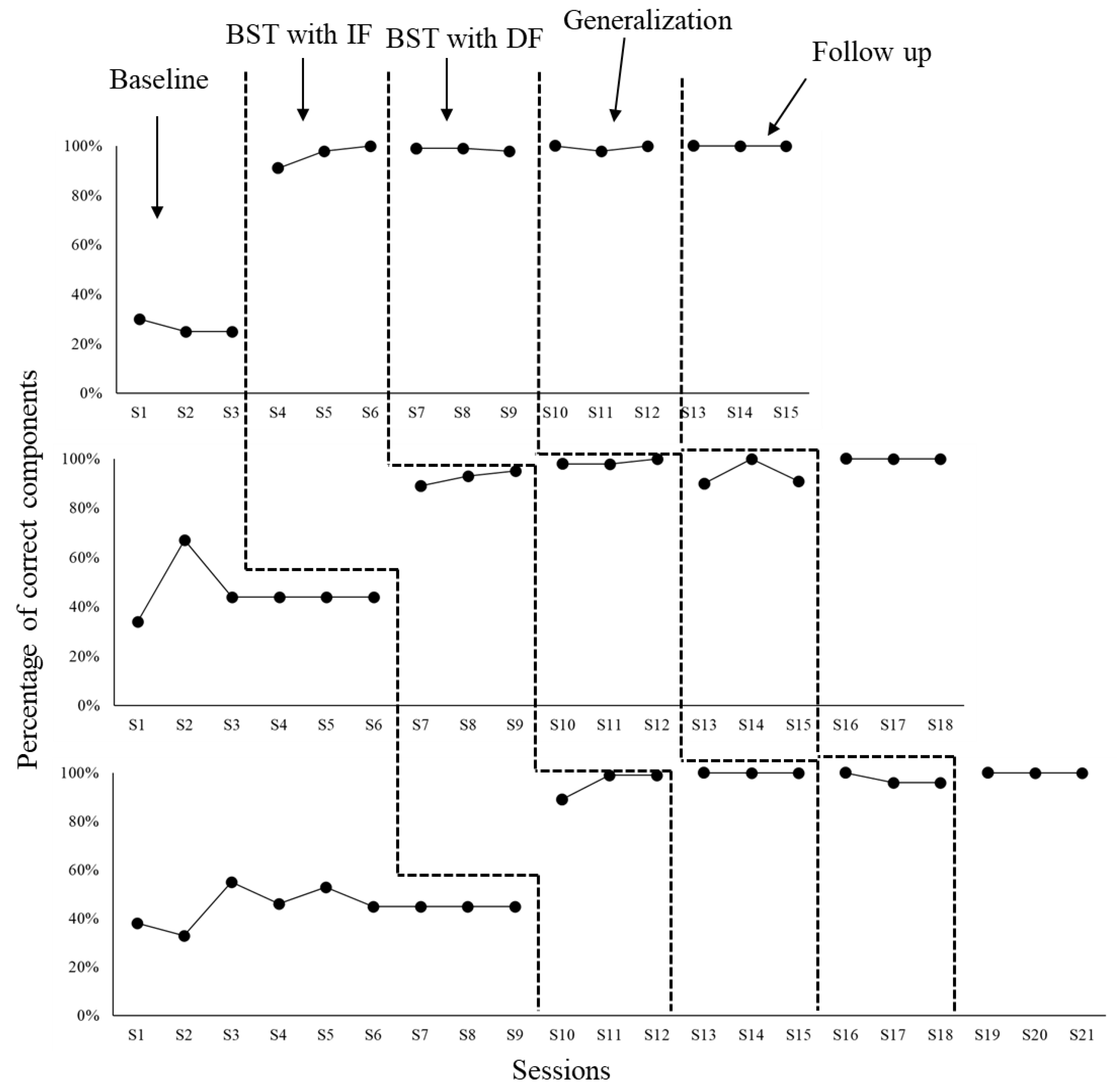

Figure 1 shows data from the first triad, that is, P1, P2 and P3.

As may be seen in

Figure 1, at the end of baseline, P1’s teaching integrity level consisted of 1% of DTT components implemented correctly (session S3). The BST training condition with immediate feedback (BST IF) was terminated after three sessions with 96% teaching integrity (S6). The BST training condition with delayed feedback (BST DF) was terminated after four sessions with 100% teaching integrity (S10). The generalization assessment condition ended with 98% teaching integrity (S13). Finally, by the end of maintenance (follow up) assessment condition, teaching integrity level was 100% of DTT components implemented correctly (S16).

In the case of P2, baseline ended with 40% teaching integrity (S6). BST IF was completed in three sessions, highlighting 99% teaching integrity at the end (S9). BST DF was terminated in four sessions with 100% teaching integrity at the end (S13). Both generalization and maintenance conditions were also finished with 100% teaching integrity (sessions S16 and S19, respectively). For P3, baseline ended with 1% teaching integrity (S9). Both BST IF and BST DF took three sessions to be terminated with 100% teaching integrity (sessions S12 and S15 respectively). By the end of both generalization and maintenance assessment conditions, teaching integrity was also 100% of DTT components implemented correctly (sessions S18 and S21, respectively).

Figure 2 shows teaching integrity for each participant in the second triad (P4, P5 and P6) across the research conditions.

According to

Figure 2, P4’s teaching integrity level by the end of baseline was of 25% DTT components implemented correctly (S3). Both BST IF and BST DF ended after three sessions with 100% (S6) and 98% (S9) teaching integrity, respectively. Both generalization and maintenance (follow up) assessments were also terminated in three sessions with 100% teaching integrity (sessions S12 and S15, respectively). P5’s teaching integrity level by the end of baseline was 44% (S6). Both BST IF and BST DF conditions ended in three sessions with 95% (S9) and 100% (S12) teaching integrity, respectively. Teaching integrity for both generalization and maintenance assessments were, at the end of three sessions, 91% (S15) and 100% (S18). P6’ teaching integrity level at the end of baseline was 45%. Both BST IF and BST DF ended in three sessions with 99% (S12) and 100% (S15), respectively. Both generalization and maintenance assessment ended with teaching integrity level of 96% (S18) and 100% (S21), respectively.

Table 1 shows the number of implementation errors of DTT components committed by all university participants across the research conditions.

For the repertoires taught, each university participant could, within sessions involving ten trials, commit up to ten implementation errors of DTT components per trial. In a trial during which a confederate or child with ASD as learner did not emit a correct response, the implementation of a DTT component concerning reinforcer delivery was not possible. Likewise, in a trial during which the learner did emit a correct response, the implementation of a DTT component concerning a correction procedure was not possible. According to

Table 1, all participants committed many errors during baseline. However, when BST IF was established, implementation errors of DTT components were greatly reduced for everyone. In addition, implementation errors remained very low or absent in the following conditions of BST DF and GEN for all participants. Even more significant data were identified in the last condition, MAN, during which no participant made any errors in implementing DTT components across probes performed three times in a four-month period. It is important to remember that GEN and MAN conditions involved interactions to teach repertoires solely to children with ASD as learners.

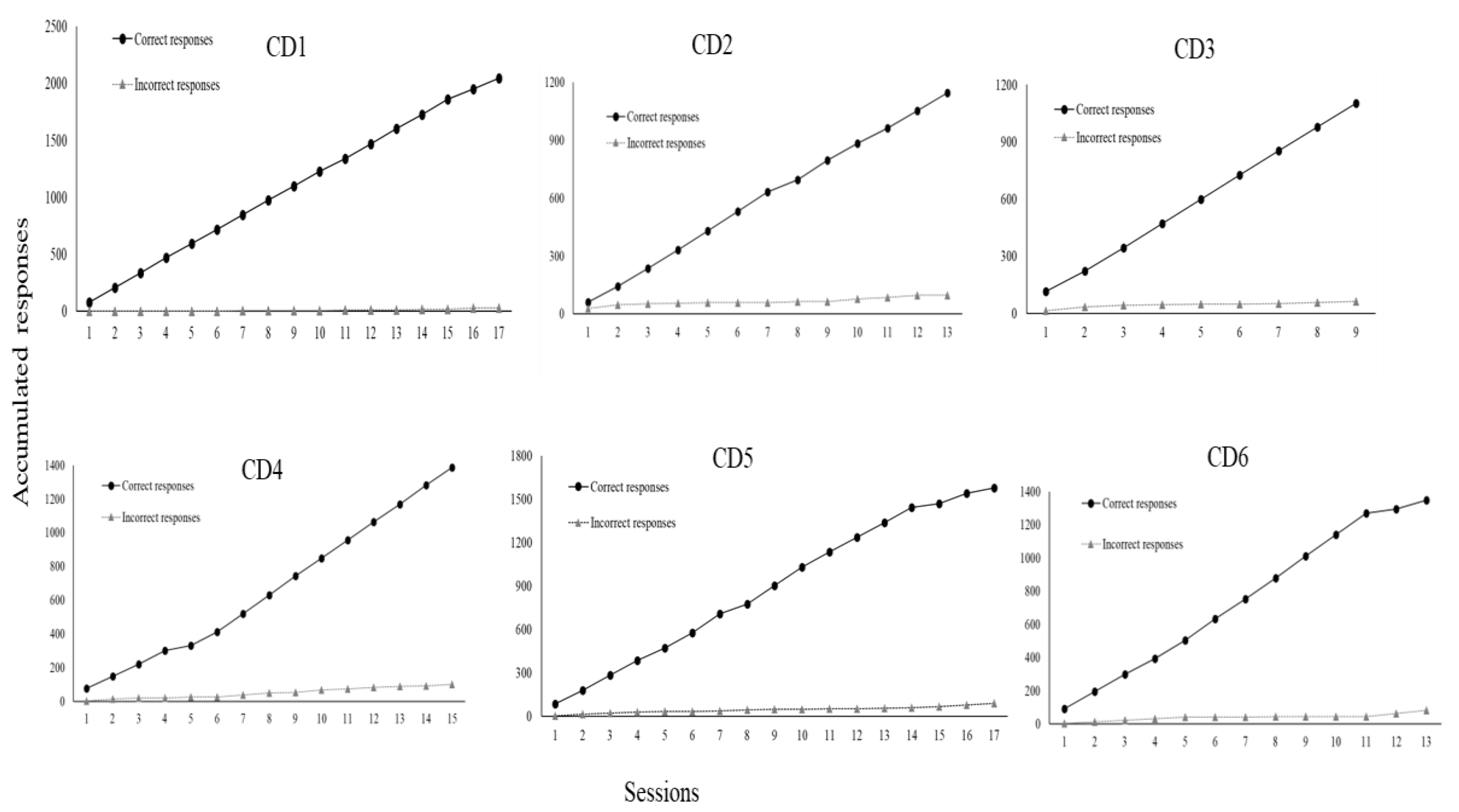

Figure 3 shows repertoire gains by the six participating children (CD1, CD2, CD3, CD4, CD5 and CD6) across these two mentioned research conditions (GEN and MAN).

As may be seen in

Figure 3, CD1 accumulated 2047 correct responses and only 27 incorrect responses. 13 repertoires were taught during the MAN condition (from session three to session 17): 1 - sitting still; 2 - making eye contact; 3 - answering questions; 4 – describing non-verbal stimuli (pictures) through vocal verbal sentences; 5 – retelling of stories; 6 – three-step motor imitation; 7 – three-step following instructions; 8 – describing actions; 9 – reading syllables; 10 – copying numbers; 11 – following the contours of the name with the pencil; 12 – receptively identifying pictures by function, feature and class; 13 – filling words in the blanks while singing.

CD2, in turn, accumulated 1145 correct responses and solely 97 incorrect responses. Ten repertoires were taught during MAN (from session three to session 13): 1 – sitting still; 2 – making eye contact; 3 – performing dictation with words; 4 – summing numbers; 5 – subtracting numbers; 6 – retelling of stories; 7 – answering questions; 8 – reading texts and answering comprehension questions; 9 – filling words in the blanks while singing; 10 – playing functionally.

CD3 accumulated 1104 correct responses and 62 incorrect responses. 13 repertoires were taught during MAN (from session three to session nine): 1 – sitting still; 2 – making eye contact; 3 – motor imitation; 4 – following instructions; 5 – making vocal verbal requests; 6 – describing actions vocally; 7 – receptively identifying pictures by their names; 8 - receptively identifying pictures by function, feature and class; 9 – answering questions and other verbal stimuli; 10 – vocal verbal imitation of words and sentences; 11 – playing functionally; 12 – drawing; 13 – reading letters and numbers.

CD4 accumulated 1387 correct responses and 101 incorrect responses. Eight repertoires were taught during MAN (from session three to session 15): 1 – sitting still; 2 – making eye contact; 3 – motor imitation; 4 – following instructions; 5 - receptively identifying pictures by function, feature and class; 6 – labeling pictures; 7 – playing functionally; 8 – making requests through one-word utterances.

CD5 accumulated 1576 correct responses and 90 incorrect responses. 13 repertoires were taught during MAN (from session three to session 17): 1 – sitting still; 2 – making eye contact; 3 – three-step motor imitation; 4 – following instructions; 5 – making requests through sentences; 6 – labeling actions in pictures; 7 – answering questions and other verbal stimuli; 8 – drawing; 9 – playing functionally; 10 – reading written or printed sentences; 11 – reading numbers; 12 - three-step following instructions with toys and other items; 13 - performing dictation with words.

CD6 accumulated 1348 correct responses and 81 incorrect responses. 13 repertoires were taught during MAN (from session three to session 13): 1 – sitting still; 2 – making eye contact; 3 – three-step motor imitation; 4 - following instructions; 5 – making requests through sentences; 6 – labeling actions in pictures; 7 – answering questions and other verbal stimuli; 8 – drawing; 9 – playing functionally; 10 - reading written or printed sentences; 11 – reading numbers; 12 - three-step following instructions with toys and other items; 13 - performing dictation with words.

Table 2, next, shows the results of the social validity assessment conducted with each of the six university participants who were trained through BST.

According to

Table 2, overall, all university participants rated the six social validity questions with the highest score, that is, five. They were satisfied with the entire BST training process.

4. Discussion

In this study, the four BST components (didactic instruction, modeling, role-play, and performance feedback) were used to train six undergraduate Psychology students in implementing the accurate teaching of multiple repertoires to a confederate pretending to be a child with ASD. BST was successful in the sense that all the university participants could teach five different repertoires to the confederate with a high teaching integrity level, that is, representing at least 90% DTT components implemented correctly. Besides, the high-performance accuracy generalized to the teaching of ten repertoires (including the five from BST training with immediate and delayed feedback) to six children diagnosed with ASD.

These data corroborate the findings of previous studies on BST involving professionals, university students and caregivers of children with ASD (Ávila & Matos, 2023; Clayton & Headley, 2019; Ferreira et al., 2016; Guimarães & Matos, 2024; Higgins et al., 2023; Lerman et al., 2008; Matos, Hübner, et al., 2021; Matos, Nascimento, et al., 2021; Sarokoff & Sturmey, 2004; Sarokoff & Sturmey, 2008; Souza et al., 2022). However, the current investigation was also an extension because, by the end of the generalization assessment condition, all six university participants were able to accurately teach ten different repertoires unlike the cases of the previous studies, whose participants taught fewer skills to learners.

This investigation also extended the previously mentioned studies on BST by training the university participants to accurately teach repertoires via DTT to children with ASD in the long term. During the follow up/maintenance assessment condition, three probe sessions were conducted across four months and no implementation errors of DTT components occurred. During this period, the six university participants systematically taught multiple repertoires to the six children with ASD involved. The skills were directly related to the curriculum goals of each child in the university laboratory attended by them once a week for 1 hour and 30 minutes. Overall, the children accumulated more than 1000 correct responses across several sessions in which they were taught by the university participants of this research.

All the repertoires taught to the six children with ASD in the study over the course of months tend to have a positive impact on their development, possibly influencing them to be more functional in different environments. This may be a prerequisite for the development of more spontaneous and naturalistic communication and greater independence in carrying out daily routines, including engagement in behavioral sequences that are important for promoting health and preventing infectious diseases such as COVID-19 (Costa & Matos, 2025).

In addition, the three probe sessions conducted by an experimenter across four months revealed that the university participants implemented all possible DTT components without any errors. All these data mentioned represent, possibly, the most relevant contributions of this study, as they suggest that BST training produced a high impact on skill gains for all the 12 participants (children and university students) in the long term. In addition, all university participants rated their training across the six questions of the social validity assessment with the highest score.

The results of this study corroborate the data involving caregivers from research by Gomes et al. (2022). In this case, the caregivers systematically taught at least ten different repertoires to six out of 17 children with ASD submitted to intensive behavioral interventions across a year. Post tests involving a standardized developmental assessment protocol showed that the six mentioned children demonstrated significant gains in repertoire compared to the others to whom multiple skills were not targeted. In the current study, all six participating children with ASD showed significant skill gains across multiple targets as well. These targets consisted of ten different skills across most of the research conditions until generalization assessment, and several other skills across the sessions in the follow up/maintenance assessment condition. However, as a limitation of this study, no standardized developmental assessment tool was used unlike the study by Gomes et al. with caregivers.

Another limitation of this study refers to the number of sessions in which the six children with ASD were submitted to DTT interventions across the four months of the maintenance assessment condition. Each child was taught only a day per week for 1 hour and 30 minutes. It is expected that many children with ASD, with difficulties in developing multiple skills, be submitted to more intensive interventions lasting several hours per week. However, the children in this research come from low-income families, unable to afford the costs of more intensive weekly interventions. The university laboratory in which they were taught is only able to allow one session per week, so more children may also be involved. Even so, it should be noted that, as another limitation of the research, some children sometimes missed sessions due to variables such as illness, or even difficulties by their caregivers due to work and other competing activities.

As was said before, an alternative may be training parents and other caregivers to implement interventions themselves (Leaf et al., 2017b), but, as was said before, it may be a challenge to train caregivers in a country where many people with low income need to spend many hours at work or on household chores, being many times unavailable (Ávila & Matos, 2023; Gomes et al., 2022). Then, it has been discussed that joining efforts to train an ever-increasing number of university students as future professionals, through BST, represents a way of increasing the number of interventionists who are better qualified to provide ABA-based services with quality and methodological precision, reducing costs for families (Matos, Nascimento, et al., 2021).

In this research, the effects of the four BST components were not assessed separately, making it impossible to isolate the effects of each component on teaching integrity levels by the university participants. However, meta-analysis research developed by Fingerhut and Moyeart (2022) discussed that the effects of BST components (didactic instruction, modeling, role-play, and performance feedback) are better when they are administered together. These authors even stated that when the four components of BST are employed together, they are statistically significant. The current study took this argument into consideration and assessed the effects of the BST components together.

Other research on training university students and caregivers also discusses possible alternatives to in-person BST training. Barboza et al. (2019) evaluated the effectiveness of an instructional video modeling approach to train mothers to implement DTT to teach repertoires to their children with ASD. Although access to instructional video modeling increased the mother’s levels of teaching integrity, the authors discussed that the instructional video modeling is more effective as part of a more comprehensive training program involving interactions with the behavior analyst trainer. Freitas et al. (2022) assessed the effectiveness of a self-instruction manual to train university students to accurately teach repertoires via DTT to children with ASD. Although the manual improved the participants’ performance, the authors also discussed that the self-instruction manual should be part of a more comprehensive approach involving other strategies such as, for example, performance feedback by the trainer.

This discussion suggests that BST, with its four components, seems to be a gold standard in training people interested in implementing ABA-based interventions, such as DTT, appropriately. However, the delivery of in-person BST may pose some important limitations. People in need to learn how to implement proper ABA interventions may encounter limitations for an in-person BST training process to conduct DTT due to variables such as, for example, living in a rural area with little access to training and supervision services, and health-related variables such as, for example, a pandemic like COVID-19, establishing the need for social isolation (Carneiro et al., 2020; Ferguson et al., 2022a, 2022b; Schieltz & Walker, 2020; Tsami et al., 2019).

Recent studies have presented as an alternative to the constraints mentioned the use of remote BST training. Ávila and Matos (2023) and Higgins et al. (2023), for example, implemented the four training components with caregivers remotely, that is, through internet. In both studies, experimenters and caregivers were accommodated at different locations and they communicated between themselves by using computers with internet. Although both studies reported positive results, in the sense that participants learned how to implement DTT accurately to teach repertoires to their children with ASD, access to computers or laptops might pose a challenge for many families with lower socioeconomic status in a country like Brazil, and who often do not have access to devices such as computers at home. It is important that alternatives be developed to address this issue. Lower-cost devices could be targeted for software development that would make remote BST more accessible to a large portion of the population that does not have a computer but does have, for example, a smartphone. It would be interesting to conduct a systematic replication study of procedures such as those used in this research, and to analyze the effects of using a remote training device such as a smartphone with internet on long-term gains in repertoire among research participants. This may represent a new important avenue for research.

5. Conclusions

BST successfully trained six Psychology undergraduate students to accurately teach multiple repertoires via DTT to a confederate and six children diagnosed with autism in the context of a university laboratory. The follow up/maintenance condition across four months on average indicated that BST training effects were long-lasting. The university participants implemented all possible DTT components in three probe sessions without errors, and the children demonstrated over 1000 correct responses across multiple skills, although each of them was only taught one day per week for 1 hour and 30 minutes. An avenue for future research may be replicating the procedures of the current study with parents and other caregivers as participants. One possible way to increase the likelihood that caregivers, from a country such as Brazil with so many socio-economic inequalities, participate in training may be through internet with remote meetings. The meetings may be held with devices such as smartphones, which many people, regardless of their socio-economic status, own.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.C.M.; L.B; C.R.P.; and P.G.S.; methodology, D.C.M.; J.R.R.C; R.M.S.M,B; F.B.S; L.B; C.R.P.; and P.G.S. ; validation, D.C.M.; L.B; C.R.P.; and P.G.S.; formal analysis, D.C.M.; J.R.R.C; and P.G.S.; investigation, J.R.R.C; R.M.S.M,B; F.B.S; L.B; C.R.P.; and P.G.S.; resources, J.R.R.C.; D.C.M.; and P.G.S.; data curation, D.C.M.; L.B; C.R.P.; and P.G.S.; writing—original draft preparation, D.C.M.; R.M.S.M.B; P.G.S.; J.R.R.C.; writing—review and editing, D.C.M.; L.B; C.R.P.; and P.G.S.; visualization, D.C.M.; L.B; C.R.P.; and P.G.S.; supervision, D.C.M.; L.B; C.R.P.; and P.G.S.; project administration, J.R.R.C.; P.G.S and D.C.M.; funding acquisition, J.R.R.C.; P.G.S and D.C.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa e ao Desenvolvimento Científico, Tecnológico e Inovação do Estado do Maranhão – FAPEMA, Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil CAPES – Código de Financiamento 001. Grant number PDPG CAPES/FAPEMA Proc. ACT-01784/21.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Federal University of Maranhão (protocol code 6.585.992 on 17 December 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study and their caregivers. .

Data Availability Statement

The authors make the raw data underlying the conclusions in this article available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- American Psychiatry Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental di sorders - DSM-5.

- Ávila, E.M.M. Ávila, E.M.M., & Matos, D.C. (2023). Efeitos do treino de habilidades comportamentais remoto em familiares de criança com transtorno do espectro autista. Revista Perspectivas em Análise do Comportamento, 14. [CrossRef]

- Baer, D.M. Baer, D.M., Wolf, M.M., & Risley, T.R. (1968). Some current dimensions of applied behavior analy sis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 1. [CrossRef]

- Bagaiolo, L.F. Bagaiolo, L.F., Mari, J.J., Bordini, D., Ribeiro, T.C., Martone, M.C.C., Caetano, S.C., Brunoni, D., Brentani, H., & Paula, C.S. (2017). Procedures and compliance of a video modeling applied behavior analysis intervention for Brazilian parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. Autism, 21. [CrossRef]

-

Barboza, A; a systematic replication: A., Costa, L.C.B., & Barros, R.S. (2019). Instructional videomode ling to teach mothers of children with autism to implement discrete trials. [CrossRef]

-

Carneiro, A; Uma revisão de literatura e recomendações em tem pos de COVID-19: C.C., Brassolatti, I.M., Nunes, L.F.S., Damasceno, F.C.A., & Cortez, M.D. (2020). Ensino de pais via telessaúde para a implemen tação de procedimentos baseados em aba. [CrossRef]

- Clayton, M. Clayton, M., & Headley, A. (2019). The use of behavioral skills training to improve staff performance of discrete trial teaching. Behavioral Interventions, 34. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.O. Cooper, J.O., Heron, T.E., & Heward, W. L. (2014). Applied behavior analysis. Second edition.

- Costa, J.R.R. Costa, J.R.R., & Matos, D.C. (2025). Teaching communication and functional life skills in children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. Behavioral Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, J., Dounavi. K.,; Craig, E.A. (2022a). The impact of a telehealth plataform on aba-based pa rent training targeting social communication in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities. ht tps://doi.org/10. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities; //doi: ht tps, 1007. [Google Scholar]

- Fergurson, J., Dounavi, K.,; Craig, E.A. (2022b). The efficacy of using telehealth to coach pa rents of children with autism spectrum disor der on how to use naturalistic teaching to in crease mands, tacts and intraverbals. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities. https:// doi.org/10. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities; // doi: https, 1007. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, L. A. Ferreira, L. A., Silva, A. J. M., & Barros, R. S. (2016). Ensino de aplicação de tentativas dis cretas a cuidadores de crianças diagnosticadas com autismo. Revista Perspectivas em Análise do Comportamento, 7(1), 101-113. https://doi. org/10.18761/pac.2015.034.

-

Fingerhut, J; a meta-analysis: , & Moeyaert, M. (2022). Training individuals to implement discrete trials with fidelity. [CrossRef]

- Freitas, L.A.B. Freitas, L.A.B., Silva, A.M., Pinheiro, M.G., Rocca, J.Z., Pinheiro, H.G.A.V.A., Osowski, V.S., & Junior, R.F.C. (2022). Avaliação da eficiência de um manual de autoinstrução para ensinar estudantes universitários a aplicar o procedimento de ensino em tentativas discretas. Revista Brasileira de Terapia Comportamental e Cognitiva, 24. [CrossRef]

- Gomes, C.G.S., Souza, J.F., Nishikawa, C.H., Andrade, P.H.M., Talma, E., Jardim, D.D. (2022). Training of caregivers of autistic children in intervention via sus. Psicologia: Teoria e Prática, 24(3), 1-14. https://doi. org/10. Psicologia: Teoria e Prática, 24; //doi: (3), 1-14. https, 5935. [Google Scholar]

- Guimarães, L.F. Guimarães, L.F., & Matos, D.C. (2024). Treino de habilidades comportamentais sobre o ensino preciso de repertórios por estudantes de pedagogia. Revista Educação Especial, 37. [CrossRef]

-

Higbee, T; a replication and extension: S., Aporta, A.P., Resende, A., Nogueira, M., Goyos, C., & Pollard, J.S. (2016). Interactive computer training to teach discrete-trial instruction to undergraduates and special educators in brazil. [CrossRef]

- Higgins, W.J., Fisher, W.W., Hoppe, A.L.,; Velasquez, L. (2023). Evaluation of a telehealth training package to remotely teach caregivers to conduct discrete-trial instruction. Behavior Modification, 47(2), 390-401. https://doi. org/10. Behavior Modification, 47; //doi: (2), 390-401. https, 1177. [Google Scholar]

- Leaf, J. B., Cihon, J. H., Weinkauf, S. M., Oppenheim- Leaf, M. L., Taubman, M.,; Leaf, R. (2017b). Parent training for parents of individuals diag nosed with autism spectrum disorder. In J. L. Matson (Ed.) Handbook of early intervention for autism spectrum disorders (5 ed., Vol. 36, pp. 109–125). Springer International Publishing. ht tps://doi.org/10. Handbook of early intervention for autism spectrum disorders; //doi: (5 ed., Vol. 36, pp. 109–125). Springer International Publishing. ht tps, 1007. [Google Scholar]

- Lerman, D.C., Tetreault, A., Hovanetz, A., Strobel, M.,; Garro, J. (2008). Further evaluation of a brief, intensive teacher-training model. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 41(2), 243-248. https://doi. org/10. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 41; //doi: (2), 243-248. https, 1901. [Google Scholar]

- Lovaas, O. I. (1987). Behavioral treatment and nor mal education and intellectual functioning in young autistic children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 55, 3-9. https://doi. org/10. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 55; //doi: , 3-9. https, 1037. [Google Scholar]

- Matos, D.C. Matos, D.C. (2016). Análise do comportamento apli cada ao desenvolvimento atípico com ênfase em autismo.

- Matos, D.C. Matos, D.C., Hübner, M.M.C., Matos, P.G.S., Araújo, C.X., & Silva, L.G. (2021). Efeitos do behavioral skills training sobre o desempenho de universitários no atendimento a crianças autistas. Revista Brasileira de Terapia Comportamental e Cognitiva, 23. [CrossRef]

- Matos, D.C. Matos, D.C., Nascimento, J.V.S., Ávila, E.M.M., & Matos, P.G.S. (2021). Comparação entre tipos de behavioral skills training para capacitação de estagiárias de psicologia. Contextos Clínicos, 14. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, C., Nunes, D.R.P., & Finatto, M.(2024). Práticas baseadas em evidências para a educação de crianças brasileiras com transtorno do espectro do autismo. In C; pesquisas na saúde e na educação (1 ed: Schmidt, C.S. Paula (Orgs.) Transtorno do espectro autista; pp. 125–146.

- Sarokoff, R.A. Sarokoff, R.A., & Sturmey, P. (2004). The effect of behavioral skills training on staff implementation of discrete-trial teaching. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 37. [CrossRef]

- Sarokoff, R.A. Sarokoff, R.A., & Sturmey, P. (2008). The effects of instructions, rehearsal, modeling, and feedback on acquisition and generalization of staff use of discrete trial teaching and student correct responses. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 2. [CrossRef]

-

Schieltz, K; a brief summary: M., & Wacker, D.P. (2020). Functional assessment and function-based treatment deli vered via telehealth. [CrossRef]

-

Acta Comportamentalia, 32; //actacomportamentalia.cucba.udg.mx/index: (2), 201-221. https.

- Skinner, B. F. Skinner, B. F. (1992). Verbal behavior.

- Souza, T.O.P. Souza, T.O.P., & Ribeiro, D.M. (2023). Revisão sistemática da literatura sobre o treinamento para a aplicação do ensino por tentativas discretas. Revista Brasileira de Terapia Comportamental e Cognitiva, 25, 1-22. [CrossRef]

-

Souza, D; an effective training for staff integrity on dtt in the application of the peak in brasil: J.M., Robertson, C.L., & Ré, T.C. (2022). A cultural generalization. [CrossRef]

- Tsami, L. Tsami, L., Lerman, D., Toper-Korkmaz, O. (2019) Effectiveness and acceptability of a parent trai ning via telehealth among families around the world. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 52, 1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varella, A.A.B.,; Souza, C.M.C. (2018). Ensino por tentativas discretas: revisão sistemáti ca dos estudos sobre treinamento com ví deo modelação. Revista Brasileira de Terapia Comportamental e Cognitiva, 20 (3), 73-85. ht tps://doi.org/10. Revista Brasileira de Terapia Comportamental e Cognitiva, 20; //doi: (3), 73-85. ht tps, 3150. [Google Scholar]

-

Watson, P; an extension of the traditional multiple baseline design: J., & Workman, E. (1981). The non-concurrent multiple baseline across-individuals design. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).