1. Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is curable and preventable infectious disease that caused by a gram-positive Bacilli bacteria called Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. The bacteria usually attack the lungs causing Pulmonary TB (PTB) and it also attacks other organs where it called Extra pulmonary TB (EPTB) [

1].

TB ranked as the 6th leading cause of death worldwide according to World Health Organization (WHO) data. The number of TB deaths decreased ranking to the 10th in the list of top 10 causes of death [

2]. Recent data showed that globally an estimated 1.2 million TB deaths among Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) negative people in 2019 (a reduction from 1.7 million in 2000), and an additional 208,000 deaths among HIV-positive people. The risk factors of TB includes HIV infection, asthma, age, overcrowding, gender, smoking habits and contact with tuberculosis patients [

3]. Oman and the Arabian gulf countries are among the counties with an estimated TB incidence rate of less than 10 per 100 000 population in 2019 [

2]. In Eastern Mediterranean Region the estimated number of TB cases was 582767 in 2007. Pakistan alone contributed to the half of these cases [

4]. There is high contribution to the prevalence of the TB in middle east by the expatriate workers [

5].

The National Tuberculosis Program in Oman was initiated in 1981. The major aim is to control the disease and stop it with the reduction of its morbidity, mortality, and transmission [

6]. The most common type of TB is pulmonary TB (PTB) which has epidemiological significance due to its extremely contagious nature [

7]. It is critical for adequate treatment and disease control to have an accurate diagnosis using different diagnostic tools, including chest radiography, sputum smear microscopy, mycobacterial culture, and nucleic acid amplification tests [

8].

In diagnosing pulmonary tuberculosis, the condition is suspected when either the tuberculin skin test or blood Interferon Gamma Release Assay (IGRA) is positive, when a chest X-ray (CXR) reveals a Ghon focus, and when there is a history of close contact with a TB patient. The primary diagnostic method is sputum sampling for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and/or Ziehl-Neelsen (ZN) staining. However, the gold standard for diagnosis remains TB culture, which is also crucial for drug susceptibility testing. If there is uncertainty or if the patient is unable to produce sputum, bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage can be employed for diagnosis [

10].

Symptoms of PTB develop gradually and include a persistent cough with mucus, shortness of breath, chest pain, hemoptysis, wheezing, general malaise, weight loss, loss of appetite, fever, fatigue, and night sweats [

11].

The use of pleural biopsy specimens is crucial for the diagnosis of tuberculous pleuritis, which is an extrapulmonary TB (EPTB) type. This test detects EPTB either by microscopy and/or culture or by the histological demonstration of caseating granulomas in the pleura along with acid-fast bacilli (AFB) [

9]. A tissue biopsy is the most reliable method for diagnosing EPTB, but it is invasive and sometimes difficult to perform. As a result, more accessible body fluids, such as pleural, peritoneal, and pericardial fluids, can often provide valuable diagnostic insights for EPTB patients [

12].

In this study, we will present the epidemiology of TB cases at our tertiary care facility, Royal Hospital in Oman, from 2015 to 2020. This will cover data on gender, age groups, risk factors, symptoms, and complications of patients with PTB and EPTB during that time, along with the diagnostic methods used and their effectiveness.

2. Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted at a tertiary care hospital in the Sultanate of Oman from 2015 to 2020, focusing on the clinical profiles of patients diagnosed with PTB and EPTB. The goal was to analyze these profiles and compare them with global data to identify any significant trends or differences.

The study involved collecting a wide range of data from electronic medical records, including patient demographics such as gender and age group, to understand the distribution of TB cases. It also examined the diagnostic methods used, such as sputum smear microscopy, culture techniques, and molecular tests like PCR, to evaluate their effectiveness in identifying TB. The presenting symptoms of patients at the time of diagnosis were documented, providing insights into the clinical manifestations of the disease. Additionally, the study investigated TB risk factors, including prior exposure and comorbid conditions, to better understand the underlying causes and potential preventive measures.

Drug resistance was another key focus, with the study analyzing instances of drug-resistant TB strains to assess treatment challenges and the effectiveness of current therapies. The research also explored associated complications, offering a broader perspective on the overall impact of TB on patients' health.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 23 to ensure thorough and accurate interpretation of the data. The study was conducted with ethical rigor, receiving approval from the Royal Hospital Ethical Committee.

3. Results

The research involved 158 patients who were diagnosed with either PTB or EPTB. The number of patients with PTB was 99 (62.7%) and EPTB was 54 (35.4%). [

Table 1]. The distribution shows that males are more prevalent in this sample. Of the participants, 63.9% were male and 36.1% were female. [

Table 2]. The prevalence of PTB in males is 69 cases compared to EPTB which is 29 cases. EPTB is slightly more common among females 27 cases compared to PTB in the same gender group 30 cases [

Table 3]. Most of the patients with TB in general are in the age group of 51 years and older [

Table 4]. The average age was approximately 50 years old. Male predominance was present in all types of TB, with 101 cases, while females accounted for 57 cases.

3.1. Clinical Presentation of Tuberculosis:

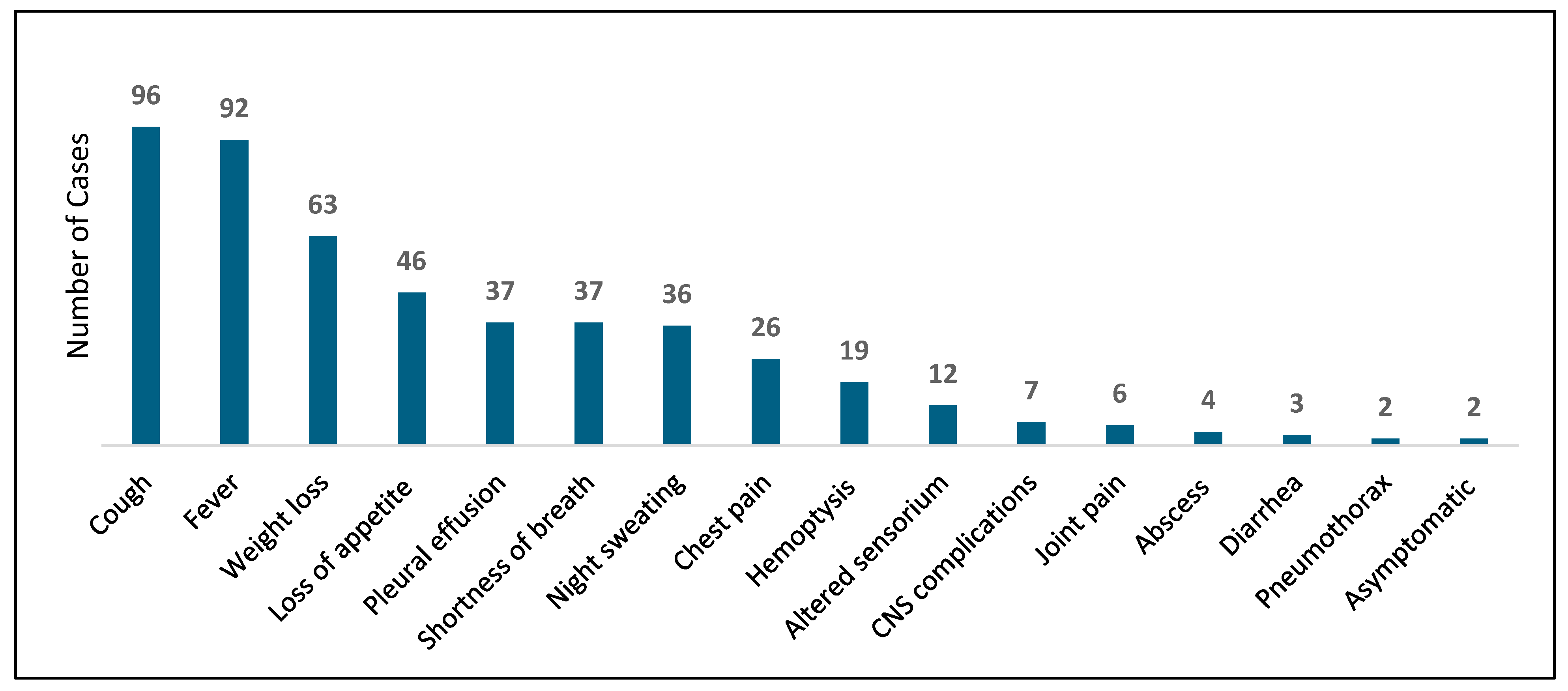

The most common presenting symptom was cough, found in 92 patients, which represents approximately 60.7% of the total study population. The second most reported symptom was fever, present in 92 cases and accounting for 58.2% of the population. Other symptoms included weight loss (63 cases), loss of appetite (46 cases), shortness of breath (37 cases), pleural effusion (37 cases), and night sweats (36 cases). Less frequently reported symptoms are listed in [

Chart 1], which details all the symptoms. Notably, TB was identified in two patients who were entirely asymptomatic. Both had PTB: the first case was detected by MTB PCR from sputum, while the second case was identified through TB culture from sputum.

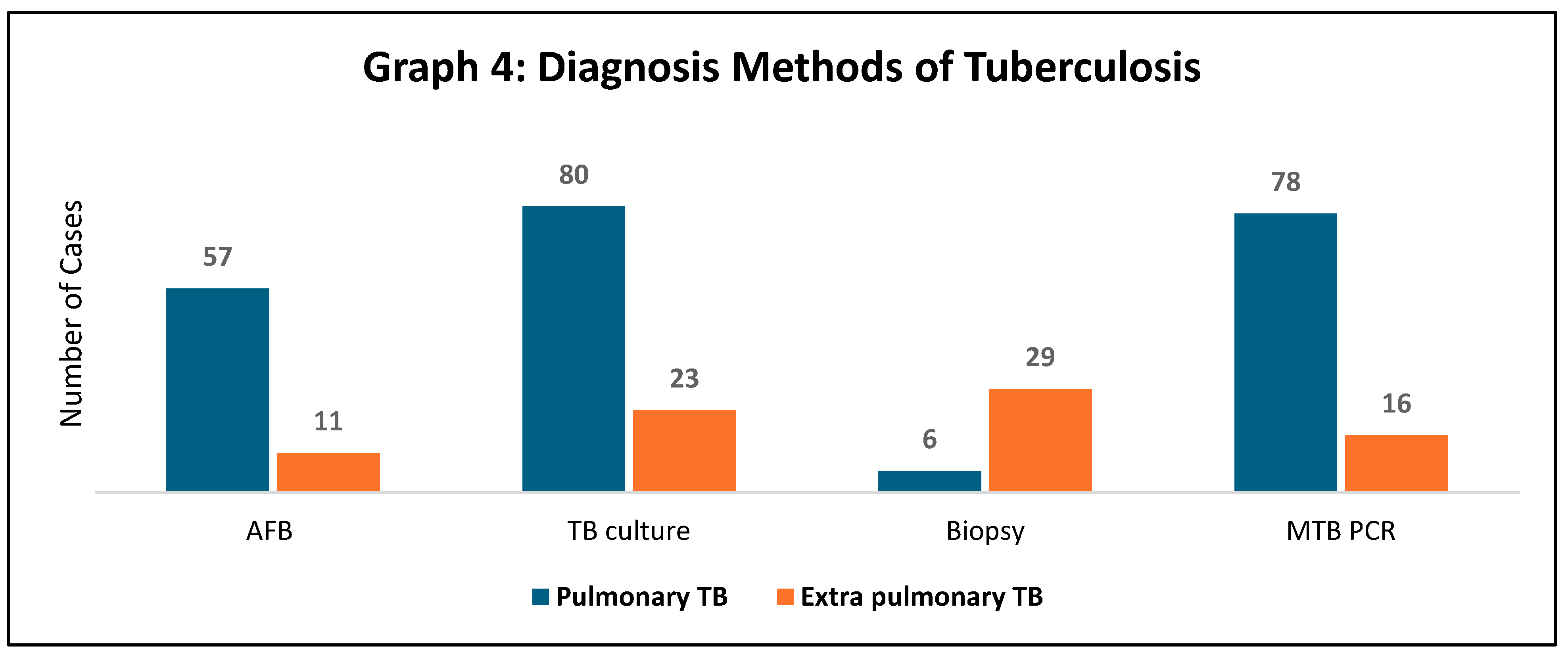

3.2. Method of Diagnosis:

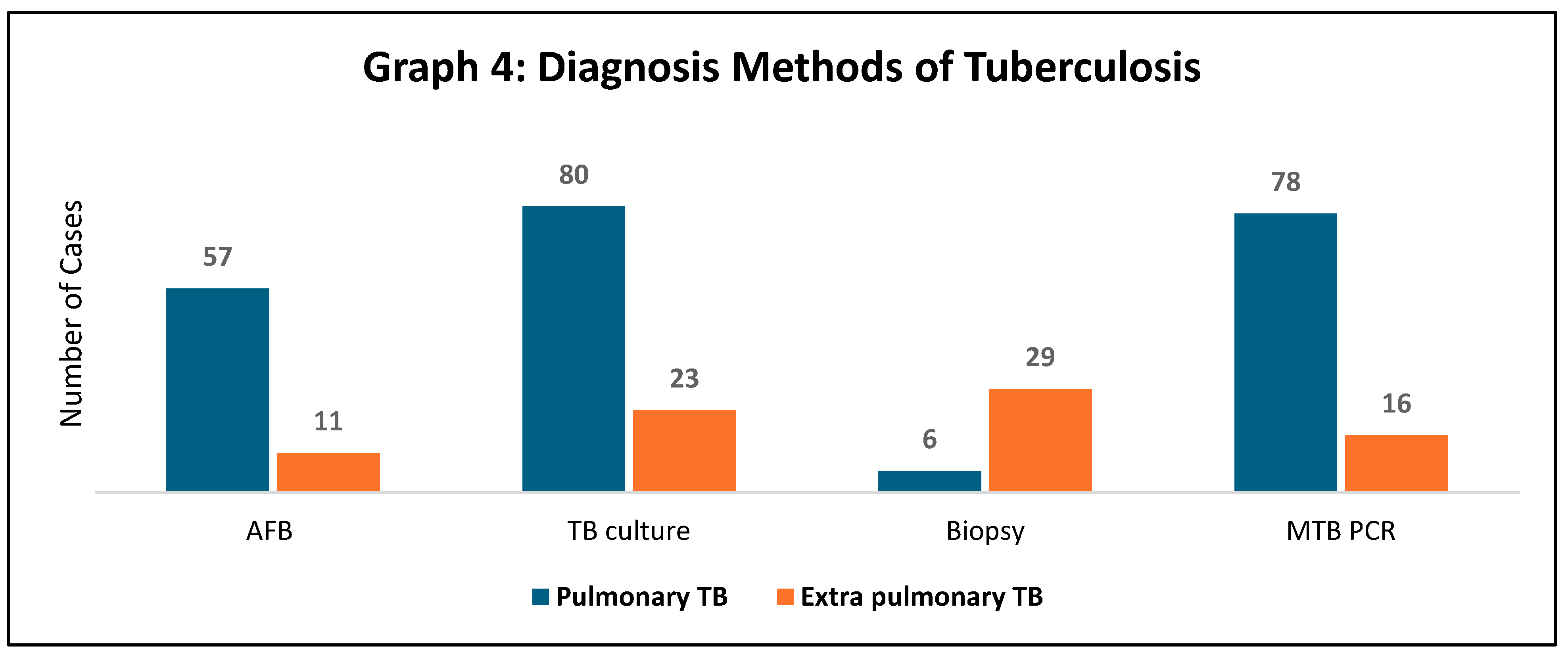

Regarding the diagnostic methods used, 57 patients in the PTB group were diagnosed with AFB study either through sputum or bronchoalveolar lavage. A lung biopsy was positive for six patients with PTB. MTB PCR was detected in 78 cases in the pulmonary TB group using sputum and bronchoalveolar lavage.

In the EPTB population, a total of 29 cases were diagnosed with TB through biopsy from the site of infection. Additionally, 23 cases had positive TB cultures from the infection site within the same group [

Table 4].

Rifampicin sensitivity was tested in some patients. It was found that 29 patients with PTB were sensitive to rifampicin, while 8 patients in the EPTB group were also sensitive. Rifampicin-resistant strains were observed in 2 patients with PTB, and 4 cases had indeterminate test results [

Table 5].

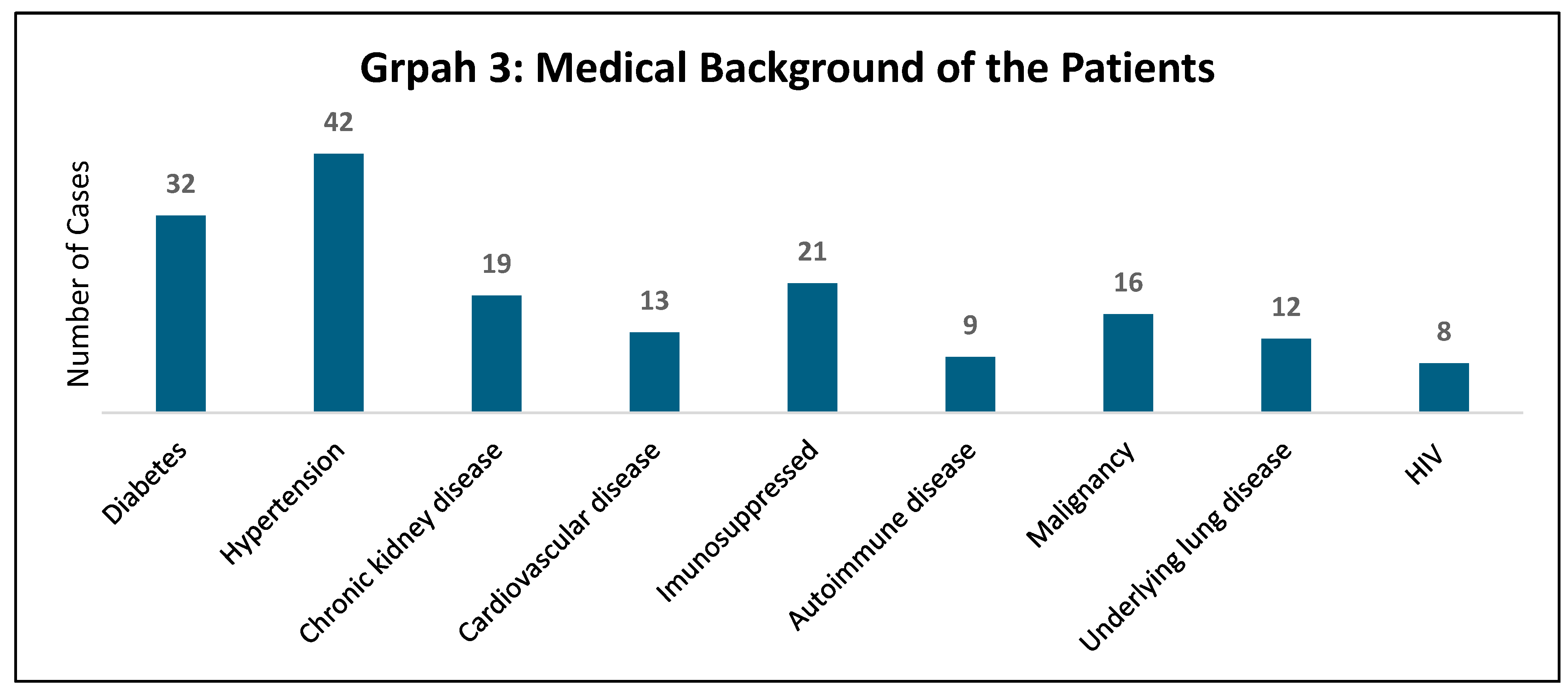

3.3. Medical Background and Associated Comorbid Conditions:

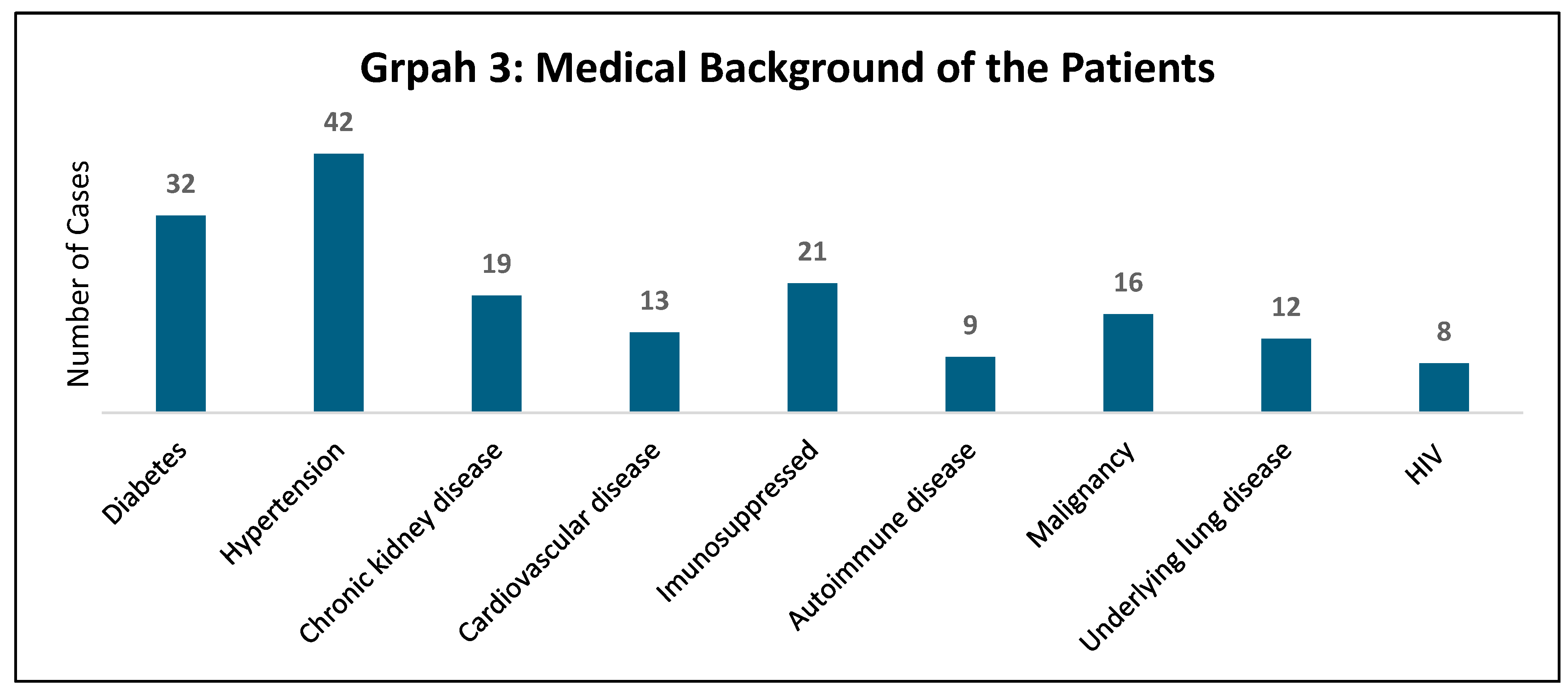

Hypertension is the most prevalent comorbidity, affecting 42 patients. Followed by diabetes, with 32 patients having this condition. Immunosuppressed patients accounted for 21 cases. Autoimmune disease and underlying lung disease are also less common, affecting 9 and 12 patients, respectively. HIV is the least common among the listed comorbidities, affecting 8 patients.

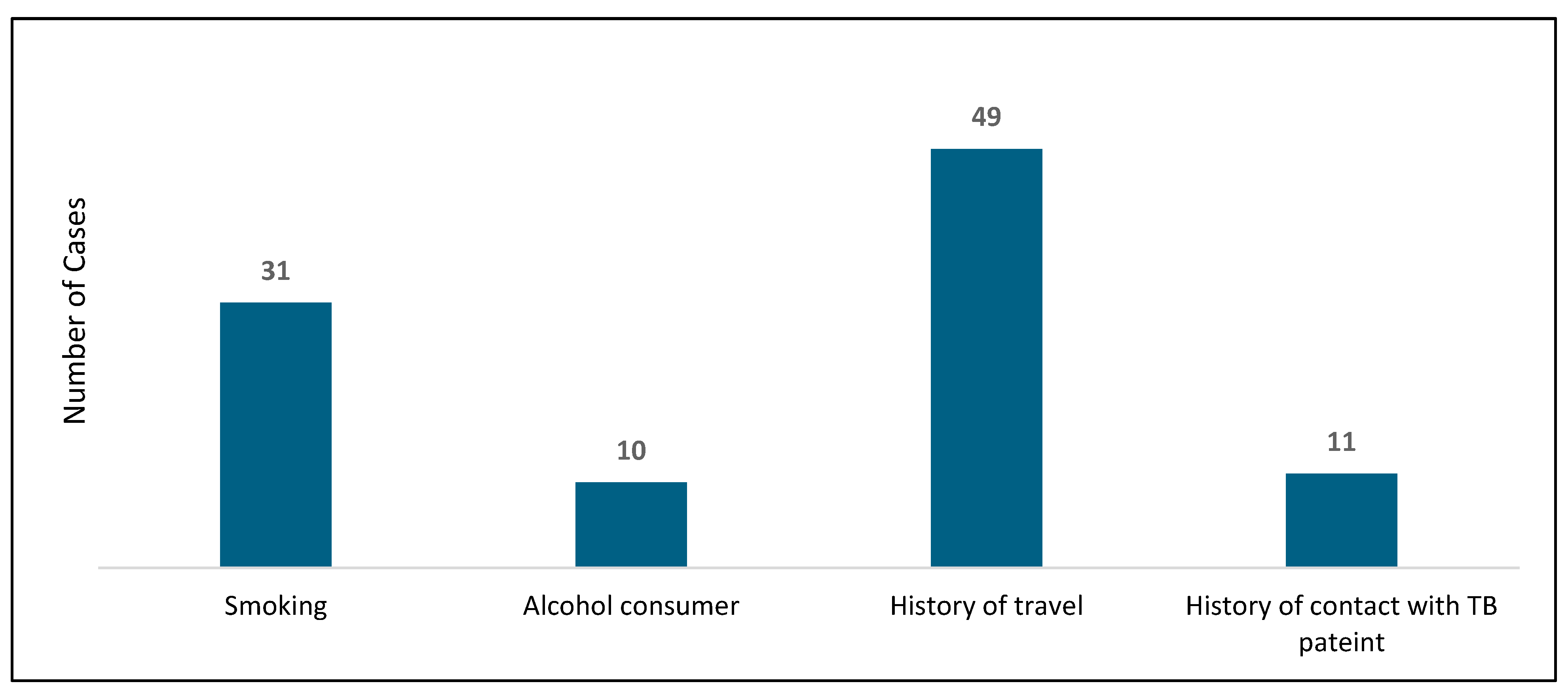

Regarding the risk factors, 31 patients were smokers, representing 19.6% of the population, while 49 patients had a history of travel. Additionally, 11 patients had a history of contact with TB patients. Only eight patients were HIV-positive. [

Chart 2 illustrates the risk factors].

3.4. Complications:

Pleural effusion was the most prevalent complication in our cohort, affecting 37 patients, or 23% of the total. The second most common complication was death, with 16 patients, or 10%, having succumbed to their condition. No cases of empyema were reported. Additionally, two patients experienced pneumothorax.

3.5. Figures, Tables and Schemes

4. Discussion

Epidemiology:

This research examines the distinct features of PTB and EPTB patients who were admitted to the Royal Hospital, a tertiary care institution in the Sultanate of Oman, from 2015 to 2020. We reviewed the records of 158 patients diagnosed with TB during this timeframe. PTB was diagnosed in 99 patients (62.7%), and EPTB was diagnosed in 56 patients (35.4%). The remaining 1.9% had disseminated TB. According to a study published in 2017 from Sultan Qaboos University Hospital, another tertiary care institution in Oman, 53% of the TB cases were pulmonary, 37% were extrapulmonary, and the rest had disseminated TB (10%) [

15]. In comparing our data to previous Omani journals, our study found almost similar percentages of types of tuberculosis, with a predominance of PTB.

The estimated TB incidence rate has decreased by 3%, and TB-related deaths have dropped by 10% since 2015 in the Western Pacific [

14]. The aim of the national program is to control the target of <1 per 100,000 population by 2035. In 2020, the annual incidence of TB was 7 cases per 100,000 people in Oman, indicating that the target for TB elimination has not yet been reached [

16].

Globally, TB cases exhibit a male-to-female ratio of 1.6:1, reflecting gender differences. [

17]. In other countries where TB still has a high prevalence, like South India, the ratio of males to females was 2.4:1 [

18]. In this study, the male-to-female ratio was 1.77:1, aligning closely with the global ratio.

Risk Factors:

Several risk factors for TB have been identified in a study done in China, including older age, residing in rural areas, being underweight, having diabetes, and close contact with PTB patients [

19]. A systematic review and meta-analysis revealed strong evidence linking tobacco smoking to a higher risk of TB [

20]. In this study, we identified that 31 patients were smokers, accounting for 19.6% of the total cohort. Among these smokers, a greater number were diagnosed with PTB, with 25 cases, compared to only 5 cases of EPTB. This suggests a stronger association between smoking and PTB in our patient population. TB control programs must take action to incorporate tobacco control as a preventive intervention [

21].

Travelers who go from countries with low TB incidence to those with high TB incidence have a considerable risk of contracting TB. It is recommended for those travelers to undergo a two-step tuberculin skin test before departure and a single-step tuberculin test upon their return [

22]. As observed in our study, a total of 49 cases had a history of travel. Among these cases, 29 individuals were non-Omanis, while 20 individuals were of Omani nationality. This distribution highlights the diverse backgrounds of the patients and suggests that both local and expatriate populations are affected by travel-related TB risks. In addition to other risk factors, 11 cases reported having contact with confirmed TB patients. This contact remains one of the primary risk factors for the transmission of the disease. The association between exposure to known TB cases and the likelihood of developing the infection underscores the importance of monitoring and managing close contacts to control the spread of TB within communities.

HIV is the most important risk factor for the progression of latent TB to active disease by 20-fold (23, 24). There is a clear link between these two diseases observed. TB impairs CD4 cell recovery and hastens the onset of AIDS and mortality in those with HIV, while HIV heightens susceptibility to TB and its progression [

25]. In South African gold mines, HIV-negative miners have a TB incidence of about 1,000 per 100,000 annually, while the overall rate is approximately 4,000 per 100,000 [

26]. In our study, we found that 8 cases had HIV positives, which accounted for 5% of the total studied population. Six of them had PTB, and two had EPTB.

Diabetes is another common comorbidity found in TB patients. Up to 30% of people with TB have diabetes, and those with diabetes have a two-to-four-fold increased risk of developing active TB. Poor glycemic control disrupts the cytokine response and weakens alveolar macrophage defenses [

27]. In this study, 20.2% (32 cases) had a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus.

Clinical Presentation:

The classical reported symptoms in individuals with TB were an intense cough lasting > 14 days, chest pain, weight loss, fever, fatigue, night sweats, and hemoptysis [

10,

28]. The classic combination of fever, night sweats, and weight loss occurs in about 75%, 45%, and 55% of patients, respectively [

29]. This study yielded comparable results. Cough was the most reported symptom (60.7%), followed by fever (58.2%), weight loss (39.8%), and loss of appetite (29.1%). The least commonly reported symptoms were primarily seen in those diagnosed with EPTB, such as abdominal pain (8 cases in the EPTB group) and lymphadenopathy (22 cases in the EPTB group).

Complications:

TB can lead to both acute and chronic complications. Commonly reported chronic complications include aspergilloma, bronchiectasis, calcifications, and malignancies arising from scars, while acute complications consist of pleural effusion and pneumothorax [

30]. Pleural effusion was the most common complication in this study, reported in twenty-one cases of PTB, 15 cases of EPTB, and 1 case of disseminated TB. A total of 16 patients (10%) died; nine had PTB, five had EPTB, and both patients with disseminated TB died. Rifampicin resistance was also tested in 40 cases. Sensitivity to rifampicin was higher in PTB 25, EPTB 8, and 1 with disseminated TB. Only two cases had rifampicin-resistant TB in the PTB group.

Limitations:

The study was conducted at a single center, which may not represent the entire population of TB cases in the country. The findings may not be applicable to broader populations due to this limitation. The duration of the study and follow-up for these patients was also limited to 5 years, which may not adequately capture long-term outcomes. During data collection, some patients had missing data that was not recorded in the medical records, as they were referred from other peripheral hospitals for follow-up treatment.

5. Conclusions

In summary, most of our patients were aged 50 years and older, with a predominant incidence of PTB. Key risk factors identified included diabetes, hypertension, and smoking. Patients are typically presented with symptoms such as cough, fever, and weight loss. The primary diagnostic methods used were AFB ZN staining and sputum culture for pulmonary TB, while issue biopsy was used for EPTB. The most frequent complications observed were pleural effusion, death, and pneumothorax.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Redha Al Lawati and Maryam Al Kamzari; methodology, Nasser Al Busaidi and Redha Al Lawati; X.X.; formal analysis, Abdul Hakeem Al Rawahi and Maryam Al Kamzari; data curation, Maryam Al Kamzari; writing—original draft preparation, Maryam Al Kamzari; writing—review and editing, Nasser Al Busaidi and Redha Al Lawati.; visualization, Redha Al Lawati.; supervision, Nasser Al Busaidi. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Royal Hospital, Ministry of Health, Sultanate of Oman with protocol code SRC#75/2022 on 4th October 2020.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived as it’s a retrospective study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TB |

Tuberculosis |

| PTB |

Pulmonary Tuberculosis |

| EPTB |

Extra Pulmonary Tuberculosis |

| HIV |

Human immunodeficiency virus |

| AFB |

Acid Fast Bacilli |

| MTB – PCR |

Mycobacterium Tuberculosis – Polymerase Chain Reaction |

References

- Centers for disease control and prevention [CDC] Tuberculosis, (2020, January20 ). https://www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/basics/default.htm) . Tubercolosis.

- Global tuberculosis report 2020 Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020.

- Tavakoli, A. Incidence and prevalence of tuberculosis in Iran and neighboring countries. Zahedan Journal of Research in Medical Sciences. 2017, 19(7).

- World Health Organization. Tuberculosis control in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: progress report 2009. 2010.

- Habibzadeh, Farrokh. (2012). Tuberculosis in the Middle East. The Lancet. http://download.thelancet.com/flatcontentassets/middle-east/Dec12_MiddleEastEd.pdf.

- Manual of TB Control Programme.2007.4th edition.OM.MOH.

- Ates Guler S, Bozkus F, Inci MF, Kokoglu OF, Ucmak H, Ozden S, Yuksel M. Evaluation of pulmonary and extrapulmonary tuberculosis in immunocompetent adults: a retrospective case series analysis. Medical Principles and Practice. 2015, 24, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong YJ, Lee KS, Yim JJ. The diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis: a Korean perspective. Precision and future medicine. 2017, 1, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorster MJ, Allwood BW, Diacon AH, Koegelenberg CF. Tuberculous pleural effusions: advances and controversies. Journal of thoracic disease. 2015, 7, 981. [Google Scholar]

- Loddenkemper R, Lipman M, Zumla A. Clinical aspects of adult tuberculosis. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine. 2016, 6, a017848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luies L, Du Preez I. The echo of pulmonary tuberculosis: mechanisms of clinical symptoms and other disease-induced systemic complications. Clinical microbiology reviews. 2020, 33, 10–128. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, JY. Diagnosis and treatment of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Tuberculosis and respiratory diseases. 2015, 78, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbett EL, Bandason T, Cheung YB, Makamure B, Dauya E, Munyati SS, Churchyard GJ, Williams BG, Butterworth AE, Mungofa S, Hayes RJ. Prevalent infectious tuberculosis in Harare, Zimbabwe: burden, risk factors and implications for control. The international journal of tuberculosis and lung disease. 2009, 13, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar]

- Morishita F, Viney K, Lowbridge C, Elsayed H, Oh KH, Rahevar K, Marais BJ, Islam T. Epidemiology of tuberculosis in the Western Pacific Region: Progress towards the 2020 milestones of the End TB Strategy. Western Pacific surveillance and response journal: WPSAR. 2020, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaifer, Z. Epidemiology of extrapulmonary and disseminated tuberculosis in a tertiary care center in Oman. The International Journal of Mycobacteriology. 2017, 6, 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babiker HA, Al-Jardani A, Al-Azri S, Petit III RA, Saad E, Al-Mahrouqi S, Mohamed RA, Al-Hamidhi S, Balkhair AA, Al Kharusi N, Al Balushi L. Mycobacterium tuberculosis epidemiology in Oman: whole-genome sequencing uncovers transmission pathways. Microbiology spectrum. 2023, 11, e02420–23. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2023). Global tuberculosis report 2023. World Health Organization. Retrieved from WHO website.

- Peer V, Schwartz N, Green MS. Gender differences in tuberculosis incidence rates—A pooled analysis of data from seven high-income countries by age group and time period. Frontiers in Public Health. 2023, 10:997025.

- Zhang CY, Zhao F, Xia YY, Yu YL, Shen X, Lu W, Wang XM, Xing J, Ye JJ, Li JW, Liu FY. Prevalence and risk factors of active pulmonary tuberculosis among elderly people in China: a population based cross-sectional study. Infectious diseases of poverty. 2019, 8, 26–35. [Google Scholar]

- Lin HH, Ezzati M, Murray M. Tobacco smoke, indoor air pollution and tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS medicine. 2007, 4, e20.

- Pai M, Mohan A, Dheda K, Leung CC, Yew WW, Christopher DJ, Sharma SK. Lethal interaction: the colliding epidemics of tobacco and tuberculosis. Expert review of anti-infective therapy. 2007, 5, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Jahdali H, Memish ZA, Menzies D. Tuberculosis in association with travel. International journal of antimicrobial agents. 2003, 21, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rewari BB, Kumar A, Mandal PP, Puri AK. HIV TB coinfection-perspectives from India. Expert review of respiratory medicine. 2021, 15, 911–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawlowski A, Jansson M, Sköld M, Rottenberg ME, Källenius G. Tuberculosis and HIV co-infection. PLoS pathogens. 2012, 8, e1002464. [Google Scholar]

- Tornheim JA, Dooley KE. Tuberculosis associated with HIV infection. Microbiology spectrum. 2017, 5, 10–128. [Google Scholar]

- Martinson NA, Hoffmann CJ, Chaisson RE. Epidemiology of tuberculosis and HIV: recent advances in understanding and responses. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 2011, 8, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishna S, Jacob JJ. Diabetes Mellitus and Tuberculosis.[Updated 2021 Apr 18]. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText. com, Inc. 2000.

- Barman TK, Roy S, Hossain MA, Bhuiyan GR, Abedin S. Clinical Presentation of Adult Pulmonary Tuberculosis (PTB): A Study of 103 Cases from a Tertiary Care Hospital. Mymensingh Medical Journal: MMJ. 2017, 26, 235–240. [Google Scholar]

- Heemskerk D, Caws M, Marais B, Farrar J. Tuberculosis in adults and children.

- Gayathri Devi, HJ. Complication of pulmonary tuberculosis. 2014.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).