1. Introduction

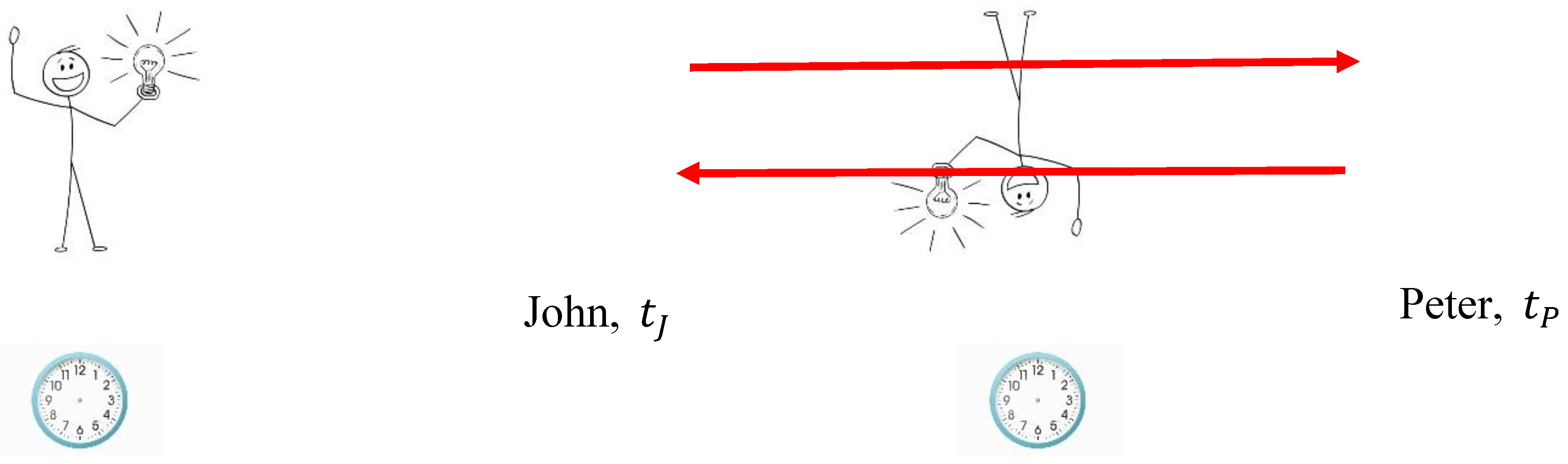

Synchronization of clocks is a cornerstone of the special and general relativity [1–4]. In Newtonian mechanics, the synchronization of clocks is a trivial, straightforward procedure, because time is considered absolute, meaning it flows the same for all observers, regardless of their state of motion or location [5–7]. In the Einstein relativity, in contrast, the situation is more complicated: synchronized clocks could not be transported from one point to another without intervention into their functioning. Two solutions were suggested for synchronization of the clocks in the special relativity: i) Einstein lattice of synchronized clocks [1–4]; ii) Eddington slow clock transport [8,9]. Einstein synchronization is introduced, as follows [3]. John records an arbitrary time on his clock, denoted

, and simultaneously sends a light pulse to Peter, who records the time

, on his clock when he received the pulse (see

Figure 1). He reflects the pulse back to John, who records the time on his clock when he receives it as

. John then sends to Peter the time

, instructing him that it is the time his clock should have been reading at time

(see

Figure 1). Thus, Peter obtains an estimate of

, the time difference between their clocks. This procedure is repeated many times and the results are averaged to obtain an accurate estimate of the interval

A modern experimental technique using Einstein synchronization is known as Time Transfer by Laser Link, developed by OCA (Observatoire de la Cote d'Azur) and tested with the Russian space station Mir, which predicted that ground stations communicating their light pulses to a common satellite can synchronize within 100 ps [10].

Within the Eddington scheme, the two clocks A and B are first synchronized locally, and then they are transported adiabatically (infinitesimally slowly) to their final separate locations [8]. These schemes of synchronization, adopted in special relativity, are very different, as it will be discussed in detail below. Einstein synchronization procedure is transitive. This means, that if clock “A” is synchronized with clock “B”, and clock “B” is synchronized with clock “C”, this necessarily means that clock “A” is synchronized with clock “C”. And the transitivity does not hold for the Eddington synchronization procedure.

The synchronization of clocks becomes much more complicated in general relativity [1,11]. Consider observers, named John and Peter, located in different points of the curved space. In general relativity, the time difference between their coordinate clocks is given by [1,11]:

where

is the metric tensor. The time span

in general relativity is not an exact differential:

Synchronization of clocks placed along a closed path becomes possible, when Eq. 3 is true, namely [11]:

which may be re-written as follows:

Thus, synchronization generally is not transitive, and simultaneity it is transitive if and only if a space-time is time-orthogonal [1,11]. In particular, Eddington's slow-clock-transport method involves physically moving a clock. If the clock moves through different gravitational potentials, this inevitably leads to non-transitivity of synchronization, if space-time is not time-orthogonal. This synchronization procedure is approximately transitive only in weak time-orthogonal gravitational fields.

Quantum synchronization is intensively discussed in the past decades [12–17]. Quantum synchronization is not necessarily transitive [12–17]. If two clocks are entangled for synchronization, their relationship does not necessarily extend transitively to a third clock [12–17]. The relation of transitivity of clocks synchronization is crucial for our approach. We apply the Ramsey theory to the problem of synchronization of clocks, whether relativistic or quantum. The Ramsey theory is the field of the general graph theory [18,19]. The fundamental idea, resulting from the Ramsey graph theory, is that in any sufficiently large graph (seen a set of vertices connected by edges), patterns or structures must emerge [20–23]. More specifically, no matter how you color the edges of a sufficiently large complete graph (where every pair of vertices is connected), you are guaranteed to find a monochromatic subgraph of a particular type (for example, represented by monochromatic triangles). The philosophical meaning of the Ramsey theory may be understood as follows: the complete chaos does not exist; ordered structures are necessarily present in sufficient large structures [20–23]. We apply the Ramsey graph to the analysis of synchronization of lattices of clocks.

2. Results

2.1. Einstein Relativistic Synchronization of Clocks: The Ramsey Approach

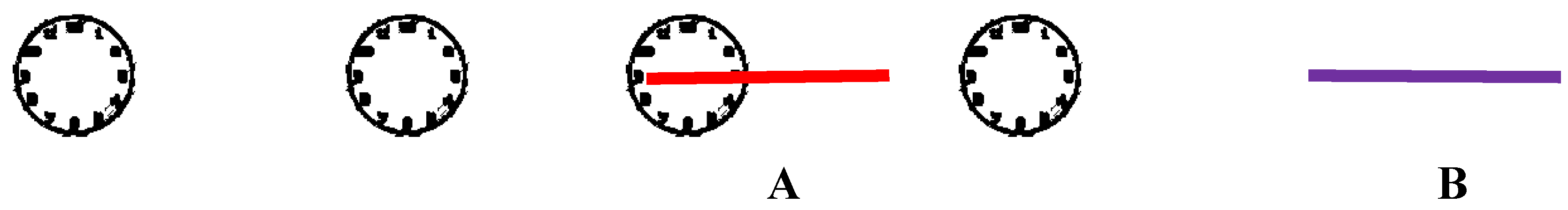

Consider the pair of clocks, depicted in Figure 2. We see the clocks as the vertices of the graph. If the clocks/vertices are synchronized with the Einstein synchronization procedure [3,4,24], they are connected with the red link/edge (see Figure 2A). If the clocks are not synchronized/unsynchronized they are connected with the violet link/edge (see Figure 2B).

This convention gives rise to the complete, bi-colored graph, which mat be introduced for any lattice of clocks. We call this graph the synchronization graph. The structure and properties of synchronization graphs will be addressed below in detail.

Figure 2.

Einstein synchronization is converted into the graph. A. Clocks synchronized with the Einstein synchronization are connected with the red link. B. Clocks, which are not synchronized with the Einstein procedure are connected with a violet link.

Figure 2.

Einstein synchronization is converted into the graph. A. Clocks synchronized with the Einstein synchronization are connected with the red link. B. Clocks, which are not synchronized with the Einstein procedure are connected with a violet link.

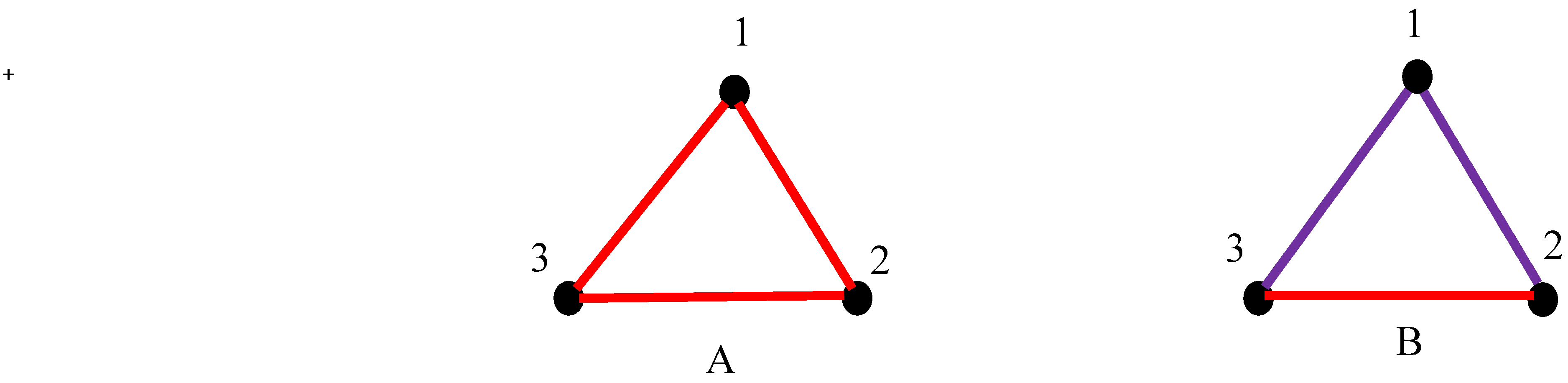

Now consider the triad of clocks, represented by the vertices of the graphs, depicted in Figure 3. Let us start from inset A. Synchronization of clocks with the Einstein protocol is transitive. Thus, if clock “1” is synchronized with clock “2”, and clock “2” is synchronized with clock “3” with the Einstein procedure, clock “1” is necessarily synchronized with clock “3”, as shown in inset A of Figure 3. Thus, all of the clocks appearing in inset A are connected with red links, and consequently the monochromatic red triangle emerges. Contrastingly, the relation “to be not synchronized” is not transitive for the Einstein synchronization, as shown in inset B. Pairs of clocks “1” and “3”, and “1” and “2” are not synchronized, and they connected with the violet links. In contrast, clocks “2” and “3” may be synchronized under the Einstein protocol, as illustrated in inset B.

Figure 3.

Triads of the clocks synchronized with the Einstein protocol are shown. A. The clocks labeled “1”, “2” and “3” are synchronized. The protocol of synchronization is transitive; thus, the monochromatic “red” triangle emerges. B. Pairs of clocks “1” and “3”, and “1” and “2” are not synchronized/unsynchronized, and they connected with the violet links clocks “2” and “3” are, in turn, synchronized under the Einstein protocol and they are connected with a red link.

Figure 3.

Triads of the clocks synchronized with the Einstein protocol are shown. A. The clocks labeled “1”, “2” and “3” are synchronized. The protocol of synchronization is transitive; thus, the monochromatic “red” triangle emerges. B. Pairs of clocks “1” and “3”, and “1” and “2” are not synchronized/unsynchronized, and they connected with the violet links clocks “2” and “3” are, in turn, synchronized under the Einstein protocol and they are connected with a red link.

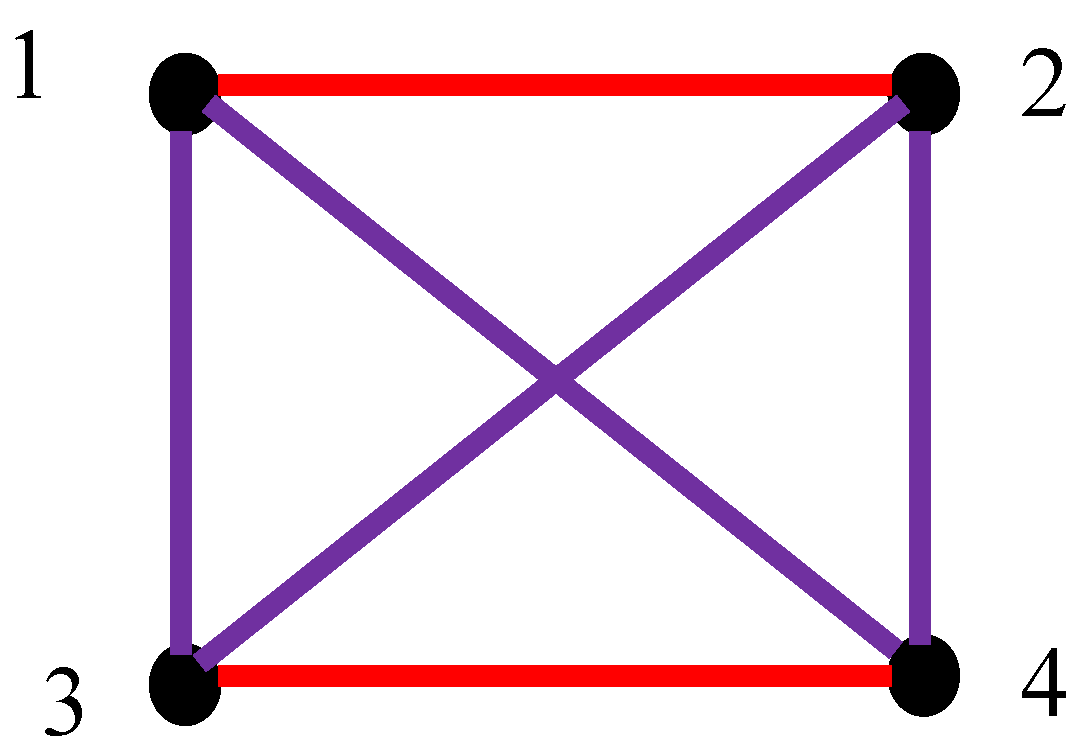

Thus, the relation between vertices/clocks to “be synchronized with the Einstein protocol” is transitive; whereas, the relation “the clocks are not synchronized” is not transitive. Thus, the semi-transitive, complete, bi-colored graph emerges from any lattice of clocks synchronized with the Einstein procedure. The properties of semi-transitive graphs were studied and reported recently [25]. Consider the bi-colored, complete graph representing four clocks some of which are synchronized under Einstein protocol and some of which are not, depicted in

Figure 4. This graph is regarded as the synchronization graph for a given lattice of four clocks.

The coloring procedure is prescribed by

Figure 2. No monochromatic triangle is present in the graph.

Figure 4.

Lattice built of four clocks/vertices some of which are synchronized with the Einstein protocol. Red link corresponds to the synchronized clocks; violet link corresponds to non-synchronized clocks. No monochromatic triangle is present in the graph.

Figure 4.

Lattice built of four clocks/vertices some of which are synchronized with the Einstein protocol. Red link corresponds to the synchronized clocks; violet link corresponds to non-synchronized clocks. No monochromatic triangle is present in the graph.

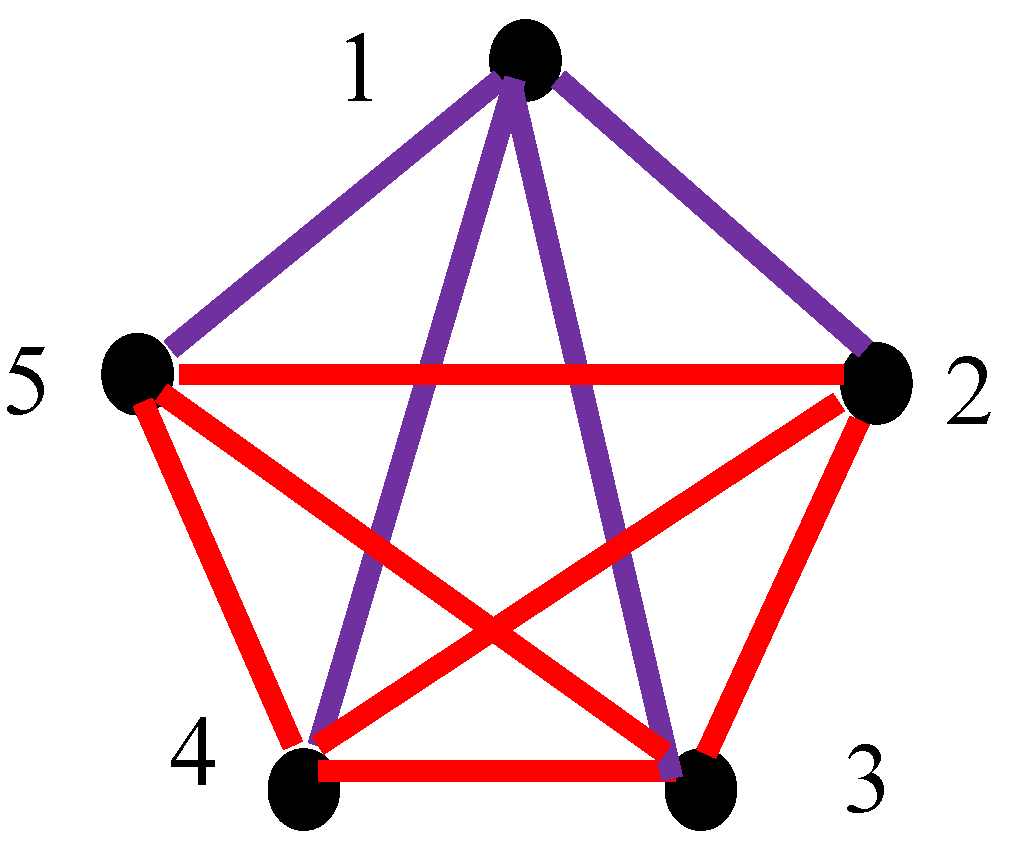

Now consider the lattice built of five clocks, synchronized with the Einstein protocol, depicted in

Figure 5. The coloring is, again, pre-scribed with

Figure 2. We recognize four monochromatic red triangles, in the synchronization graph, shown in

Figure 5; namely triangles “245”, “235” “234”, and “345”. In other words, triangles “245”, “235” “234”, and “345” are built form synchronized clocks only.

This observation follows from the fact, that the Ramsey semi-transitive number was established as . Thus, any semi-transitive, complete graph built of five vertices will necessarily contain at least one mono-chromatic triangle [25]. Recall, that for the non-transitive, complete, bi-colored graph . This means that in any bi-colored, complete graph built of six vertices, the monochromatic triangle will inevitably appear.

2.2. Synchronization of Clocks in General Relativity: The Ramsey Approach

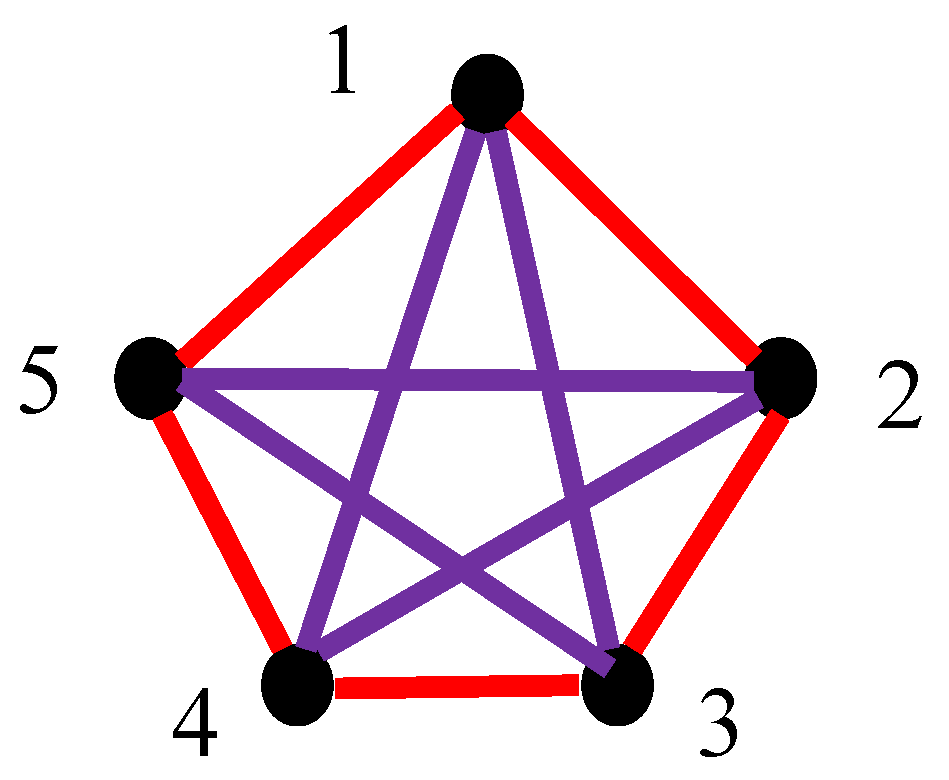

Consider the synchronization of clocks in general relativity, when a space-time is not time-orthogonal. We address first the lattice built of five clocks, depicted in

Figure 6. The coloring procedure is prescribed by

Figure 2. Now the synchronization is non-transitive [1,11].

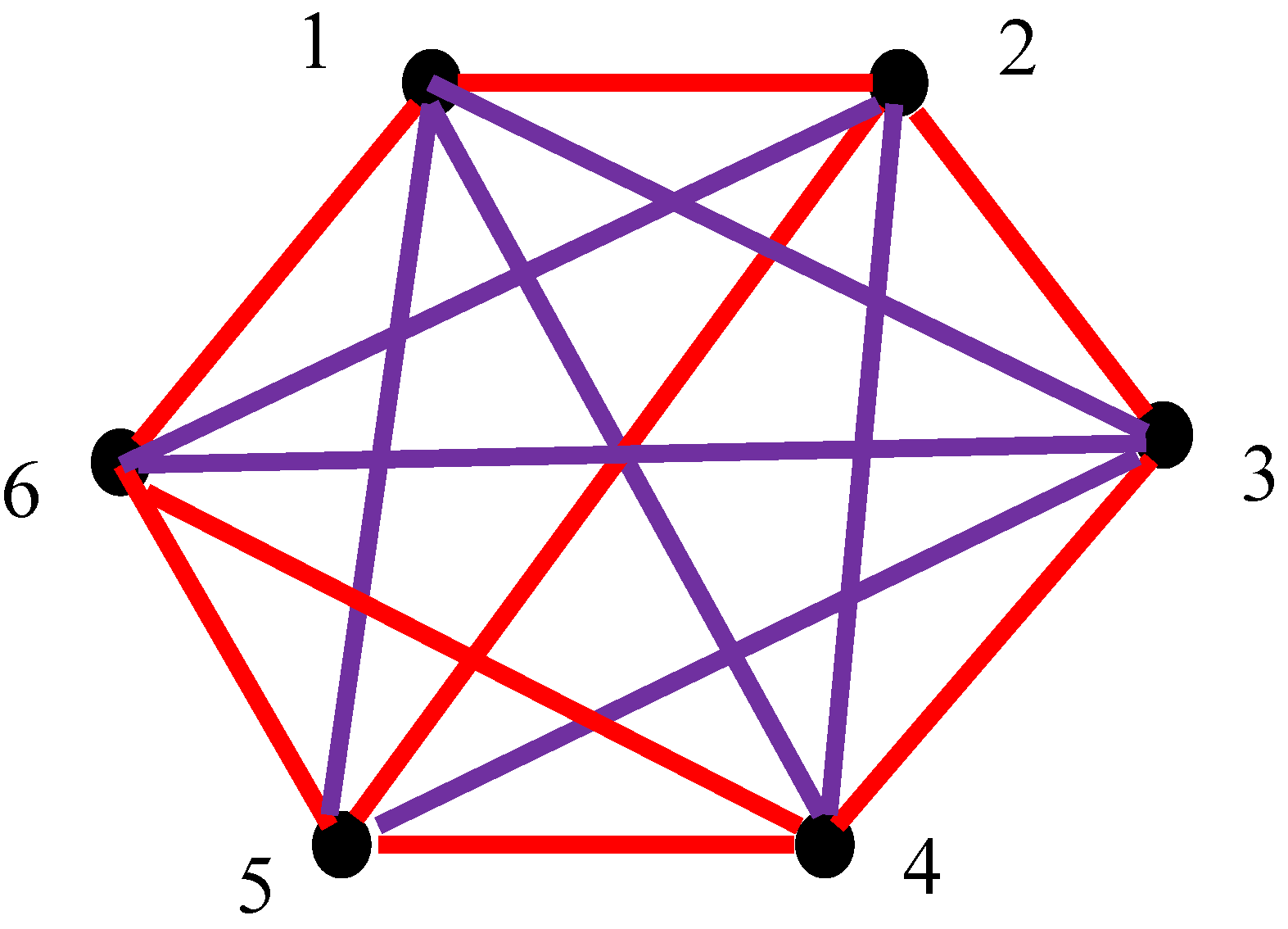

Now we address the lattice built of six clocks, depicted in

Figure 7. The procedure of synchronization is supposed to be non-transitive. This lattice contains two monochromatic triangles, namely, we recognize from

Figure 7, that the triangle “456” is monochromatic red, and it represents the triad of synchronized clocks. Triangle “135” is, in turn, monochromatic violet, and it in turn represents the triad of non-synchronized clocks. Moreover, any lattice built of six clocks will contain at least one monochromatic triangle. This immediately follows from the Ramsey theorem and the fact that the Ramsey number

Thus, we demonstrated the following theorem.

Theorem: Consider the lattice built of six clocks, embedded into the relativistic curved space-time. Some pairs of the clocks are synchronized and some of them are not synchronized. The procedure of synchronization is supposed to be non-transitive. The lattice will inevitably contain the triad of synchronized, or alternatively non-synchronized clocks.

It should be emphasized that the Ramsey theory does not predict that the exact color of the mono-chromatic triangle to be present in the lattice built of synchronized/non synchronized clocks [20–23].

2.3. Ramsey Approach to Quantum Synchronization of Clocks

Various procedures of quantum synchronization were suggested [12–17]. We consider synchronization protocol exploiting quantum entanglement [13–17]. Synchronization of clocks based on quantum entanglement is not transitive [12–17]. Thus, we consider the lattice of six clocks, depicted in

Figure 7. Some of clocks are synchronized with quantum entanglement and some of them are not. Any lattice built of six clocks, represented by the synchronization graph, will inevitably contain the mono-chromatic triangle, as follows from the Theorem, demonstrated in the previous section.

2.4. Ramsey Approach to Synchronization of Logical Clocks

Logical clocks were introduced for ordering events in distributed databases. Logical clocks order events without relying on physical time. Logical clocks were introduced by Lamport in 1978 [26]. Lamport clocks lead to a situation where all events in a distributed system are totally ordered. That is, if

, then we define that

a logically happened before

b [27]. Synchronization of logical clocks (such as Lamport timestamps) is transitive, but only in the sense of causality propagation [26,27]. The relation “to be not synchronized” is not transitive for the synchronization of logical clocks. Thus, we return to the semi-transitive graphs, such as depicted in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5. Thus, any lattice built of five synchronized/non synchronized clocks will contain at least one monochromatic triangle.

2.5. Synchronization of Clocks and Symmetry

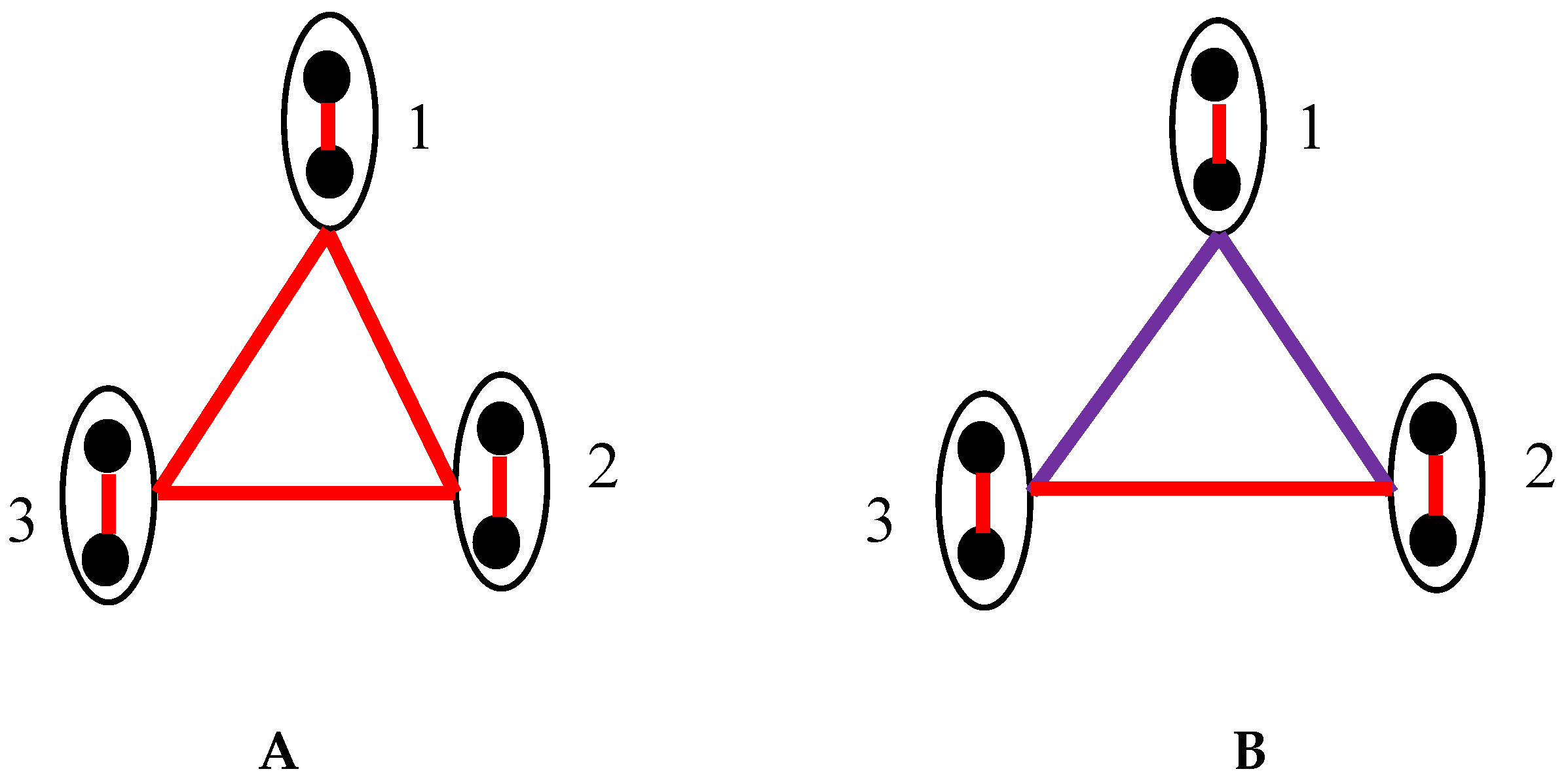

Symmetry considerations are one of the most fundamental in physics [28,29]. Let us introduce symmetry considerations in our analysis. Consider four-fold symmetrical lattice of clocks, synchronized with the Einstein transitive relativistic protocol, depicted in inset A of

Figure 8. The synchronization graph, reflecting the symmetry of the lattice, shown in inset A, does not contain monochromatic triangles. Five-fold symmetrical lattice of five clocks, synchronized with the Einstein transitive relativistic protocol, which does not contain monochromatic triangles is impossible.

Five-fold symmetrical lattice of clocks synchronized/non synchronized with the non-transitive protocol, which does not contain monochromatic triangles is possible and its synchronization graph is depicted in inset B of

Figure 8.

2.6. Generalization of Suggested Approach: Pairs of Synchronized Clocks Seen as the Vertices of Bi-Colored, Complete Graph

Generalization of suggested approach for pairs of synchronized clocks, seen as the vertices of bi-colored, complete graph is possible. Even number of

N clocks may be separated into

pairs of clocks. These pairs may be synchronized within one the aforementioned synchronization protocols. Now we consider these pairs of clocks as the vertices of the graph. The pairs are not necessarily synchronized. At the next stage, the pairs may be synchronized with one of the aforementioned procedures. Synchronization with the Einstein protocol is shown in

Figure 9. The transitivity of the Einstein synchronization is illustrated with

Figure 9A. The further analysis is straightforward; general relativity and quantum synchronization of the pairs of clocks is performed in a similar way. The suggested procedure is easily extended to the logical clocks.

3. Discussion

Ramsey theory is applicable to any set of physical objects related each to other with different kinds of physical relations. These relations may, for example, represent interactions between physical bodies, seen as the vertices of the graph [30]. The interactions, classified as attractions and repulsions, may be seen as the differently colored links of the graph [30]. Thus, the bi-colored, complete Ramsey graph emerges. The transitivity of the interactions plays a crucial role in the analysis of the graph [30]. Thus, it seems that the Ramsey theory demonstrates an enormous potential for physics. However, the applications of the Ramsey theory to physical problem are still infrequent [30–35].

We suggest the Ramsey approach to synchronization of lattices of clocks, in which the clocks serve as the vertices of the synchronization graph, and relations between the clicks considering their synchronization define the color links, connecting the vertices/clocks. The synchronized clocks are connected with the red link. Thus, the synchronized clocks are considered as “friends” in the terms of the Ramsey theory; whereas, the vertices/clocks, which are not synchronized are considered as “strangers” [20–23]. Thus, the complete, bi-colored, Ramsey graph describing the synchronization within the given lattice of clocks emerges. Clock synchronization is one of the critical factors for time-based localization, in particular, in the GPS-based time synchronization [36,37]. The problem is also crucial for synchronization of computers in networks [38]. Thus, the addressed approach demonstrates an obvious applicative potential.

4. Conclusions

Synchronization of clocks plays the key role in the special and general relativity and also in the quantum theory. Various protocols providing such a synchronization were suggested. We propose the Ramsey approach to synchronization of the lattices of clocks. The clocks may be synchronized and may be unsynchronized. The clocks serve at the vertices of the graph and the synchronization defines the color of the link connecting the vertices/clocks. Synchronized clocks are connected with the red link; they are seen as “friends” in the terms of the famous “party problem” of the Ramsey theory. Unsynchronized clocks are seen, in turn, as “strangers”. They are connected with the violet link. Thus, the complete, bi-colored, Ramsey synchronization graph emerges in any given lattice of physical clocks. The coloring of the graph depends on the transitivity of the applied method of synchronization of the clocks. For example, Einstein protocol of synchronization of clocks in special relativity is transitive; whereas, synchronization of clocks in general relativity is not necessarily transitive. The relation “to be unsynchronized” is not transitive for all kinds of accepted protocols of synchronization. If the synchronization is transitive, the semi-transitive Ramsey graph emerges. The Ramsey number for semi-transitive graphs was established as . This means that in any semi-transitive lattice, built of five clocks, at least one monochromatic triangle will necessarily appear. If the synchronization is non-transitive, the usual, bi-colored, complete Ramsey graph arises. The Ramsey numbers for these graphs are known as: This means that in any non-transitive graph, reflecting the lattice of built of six clocks, at least one monochromatic triangle will necessarily appear. The Ramsey theory does not predict the exact color of the monochromatic triangle to be present in the bi-colored, complete graph, built of six vertices.

This approach is easily extended to quantum synchronization protocol exploiting quantum entanglement. Synchronization of clocks based on quantum entanglement is not transitive. Any lattice built of six clocks, synchronized with quantum entanglement, will inevitably contain the mono-chromatic triangle built of synchronized/non-synchronized clocks. Thus, “ordering” spontaneously emerges in the lattices of clocks.

Now consider the logical clocks, which were introduced for ordering events in distributed databases. Logical (Lamport) clocks order events, being disconnected from physical time, keep logical causality. Synchronization of logical clocks is transitive. Any lattice built of five synchronized/non synchronized clocks will contain at least one monochromatic triangle.

The relation between symmetry of the lattices of clocks and their coloring was addressed. Four-fold symmetrical lattice of clocks, synchronized with the Einstein transitive relativistic protocol is possible; whereas, the five-fold symmetrical lattice of clocks, synchronized with the Einstein protocol, which does not contain mono-chromatic triangles is impossible. Five-fold symmetrical lattice of clocks synchronized/unsynchronized with the non-transitive protocol, which does not contain monochromatic triangles is possible. Applications of the developed approach are addressed. We conclude, that logical transitivity deeply influence the synchronization within the given lattices of clocks. In other words, logical transitivity could not be separated from the properties of space-time.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.B.; methodology, E. B.; formal analysis, E.B.; investigation, E.B.; writing—original draft preparation, E.B.; writing—review and editing, E.B.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The author is thankful to Nir Shvalb for useful discussions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Landau, L.; Lifshitz, E.M. The Classical Theory of Fields, 4th ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 1975; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Tolman, R.C. Relativity, Thermodynamics and Cosmology; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Bohm, D. The Special Theory of Relativity, Taylor & Francis, London, UK, 2025.

- Moller, C. The Theory of Relativity, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 1952.

- DiSalle, R. Understanding Space-Time: The Philosophical Development of Physics from Newton to Einstein. Cambridge, Cambridge University Pres, UK, 2006.

- DiSalle, R. Absolute space and Newton’s theory of relativity. Studies in History & Philosophy Sci. 2020, 71, 232–244. [Google Scholar]

- Bussotti, P., Lotti, B. Newton and His System of the World. In: Cosmology in the Early Modern Age: A Web of Ideas. Logic, Epistemology, and the Unity of Science, 2022, vol 56. Springer, Cham, Switzerland.

- S. Eddington, The Mathematical Theory of Relativity, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 1924.

- Anderson, R.; Vetharaniam, I.; Stedman, G.E. Conventionality of synchronisation, gauge dependence and test theories of relativity, Physics Reports, 1998, 295 (3–4), 93-180.

- Samain. E.; Fridelance, P. Time Transfer by Laser Link (T2L2) experiment on Mir, Metrologia, 1998, 35, 151.

- Zheng, Z.; Chen, P. Zeroth law of thermodynamics and transitivity of simultaneity. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 1997, 36, 2153–2159. [Google Scholar]

- de Burgh, M.; Bartlett, S. D. Quantum methods for clock synchronization: Beating the standard quantum limit without entanglement, Phys. Rev. A 2005, 72, 042301.

- Ilo-Okeke, E.O. , Tessler, L., Dowling, J.P. et al. Remote quantum clock synchronization without synchronized clocks. NPJ Quantum Inf. 2018, 4, 40. [Google Scholar]

- Zhirov, O.; Shepelyansky, D. Quantum synchronization. Eur. Phys. J. D 2006, 38, 375–379. [Google Scholar]

- Vinokur, V.; Baturina, T.; Fistul, M.; Mironov, A. Yu.; Baklanov, M. R.; Strunk, C. Superinsulator and quantum synchronization. Nature 2008, 452, 613–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roulet, A.; Bruder, C. Quantum Synchronization and Entanglement Generation, Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 121, 063601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohe, M. A. Quantum synchronization over quantum networks. J. Phys. A: Math. Theor. 2010, 43, 465301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondy, J. A.; Murty, U.S. R Graph Theory, Springer, New York, 2008.

- Bollobás, B. Modern graph theory, vol 184. Springer, Berlin, 2013.

- Graham, R. L.; Rothschild, B.L.; Spencer, J, H. Ramsey theory, 2nd ed., Wiley-Interscience Series in Discrete Mathematics and Optimization, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, A Wiley-Interscience Publication, 1990, pp. 10-110.

- Graham, R.; Butler, S. Rudiments of Ramsey Theory (2nd ed.). American Mathematical Society: Providence, Rhode Island, USA, 2015; pp. 7–46.

- Di Nasso, M.; Goldbring, I.; Lupini, M. Nonstandard Methods in Combinatorial Number Theory, Lecture Notes in Mathematics, vol. 2239, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 2019.

- Katz, M.; Reimann, J. Introduction to Ramsey Theory: Fast Functions, Infinity, and Metamathematics, Student Mathemati-cal Library Volume: 87; 2018; pp. 1-34.

- Taylor, E.F.; Wheeler, J. H. Spacetime Physics, 2nd edition, W. H. Freeman and Co, New, York, USA, 1992.

- Gilevich, A.; Shoval, Sh.; Nosonovsky, M.; Bormashenko Ed., Converting Tessellations into Graphs: From Voronoi Tessellations to Complete Graphs, Mathematics 2024, 12(15), 2426.

- Lamport, L. Time, clocks, and the ordering of events in a distributed system, Communications of the ACM, 1978, 21 (7), 558–565.

- Kulkarni, S.S.; Demirbas, M.; Madappa, D.; Avva, B.; Leone, M. Logical Physical Clocks. In: Aguilera, M.K., Querzoni, L., Shapiro, M. (eds) Principles of Distributed Systems. OPODIS 2014. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 8878. Springer, Cham, Switzerland, 2014.

- Rosen, J. Symmetry in Science: An Introduction to the General Theory; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Weyl, H. Symmetry; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bormashenko Ed. Universe as a Graph (Ramsey Approach to Analysis of Physical Systems), World J. Physics, 2023, 1 (1), 1-24.

- de Gois, C.; Hansenne, K.; Gühne, O. Uncertainty relations from graph theory. Phys. Rev. A 2023, 107, 062211. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z-P.; Schwonnek, R.; Winter, A. Bounding the Joint Numerical Range of Pauli Strings by Graph Parameters. PRX Quantum, 2024, 5, 020318.

- Hansenne, K.; Qu, R.; Weinbrenner, L. T.; de Gois, C.; Wang, H.; Ming, Y.; Yang, Z.; Horodecki, P.; Gao, W.; Gühne, O. Optimal overlapping tomography, arXiv: 2408.05730, 2024.

- Wouters, J.; Giotis, A.; Kang, R.; Schuricht, D.; Fritz, L. Lower bounds for Ramsey numbers as a statistical physics problem. J. Stat. Mech. 2022, 2022, 0332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bormashenko, Ed.; Shvalb, N. A Ramsey-Theory-Based Approach to the Dynamics of Systems of Material Points. Dynamics 2024, 4, 845–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Braun, T.; Dimitrova, D.C. Methodology for GPS Synchronization Evaluation with High Accuracy. In 2015 IEEE 81st Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC Spring), Glasgow, UK, 2015, 1–6.

- Pallier, D.; Le Cam, V.; Pillement, S. Energy-Efficient GPS Synchronization for Wireless Nodes, IEEE Sensors J. 2021, 21 (4), 5221-5229.

- Chefrour, D. Evolution of network time synchronization towards nanoseconds accuracy: A survey, Computer Communications, 2022, 191, 26-35.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).