1. Introduction

Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) molecules play a central role in the immune system by presenting peptides (also known as antigens) to T cells, thereby initiating immune responses. These molecules are essential for the recognition of self and non-self, making them key players in the body’s defense mechanisms against pathogens and cancer, but they also play an important role in the context of autoimmunity and transplant rejection. MHC molecules are polygenic and polymorphic, making them the most diverse genes. The polygenic nature enhances the ability of an individual’s immune system to recognise a wide array of pathogens. At the same time, the polymorphic diversity on the population level is crucial for the survival of mammalian species, as it increases the likelihood that some individuals within a population will be able to mount an effective immune response against emerging infectious diseases.

Immunopeptidomics is a branch of proteomics that focuses on the study of peptide antigens bound to MHC molecules [

1]. By analysing the entire breadth of the antigenic peptide repertoire, immunopeptidomics not only provides insights into the antigen processing and presentation pathway, but also aids in the identification of potential targets for vaccine development and immunotherapies. Advances in mass spectrometry and bioinformatics have greatly enhanced the ability to detect and quantify these peptides. However, some limitations still persist due to the extensive diversity of MHC variants, which can complicate the analysis of the immunopeptidome on the population level.

Mice have long been a cornerstone of immunological and MHC research due to the wealth of genetically modified strains and their well-characterized immune systems. Among these, the C57BL/6 and BALB/c strains are the most extensively studied, providing an insight into immune responses and the aetiology of diseases. However, there remains a significant gap in our understanding of MHC antigen presentation in other strains, including Swiss mice that are the focus of this study.

These mice, also known as Swiss Webster and CD-1 mice, are a versatile outbred albino strain. Unlike the inbred C57BL/6 and BALB/c strains, outbred Swiss mice exhibit greater genetic diversity, making them valuable for studies requiring a broader genetic background [

2]. This diversity can provide more generalisable results, particularly in toxicology, pharmacology, and general biomedical research. Furthermore, Swiss mice are exceptionally good breeders and used where large litter sizes or embryo transfers are required.

Somewhat surprisingly, despite their widespread use in biomedical research, little is known on the MHC haplotype of Swiss mice and detailed information on antibody clones that recognise MHC allotypes specifically expressed by Swiss mice is lacking. It must be noted that the MHC haplotypes of C57BL/6, BALB/c, and Swiss mice exhibit significant differences when examined by serological typing, reflecting their distinct genetic backgrounds. C57BL/6 mice possess the H-2b haplotype, characterized by specific MHC class I (H-2Kb, H-2Db) and class II (I-Ab) molecules. This haplotype is associated with a robust immune response and is widely used in immunological research. BALB/c mice carry the H-2d haplotype, with H-2Kd, H-2Dd, H-2Ld (MHC class I) and I-Ad, I-Ed (MHC class II) molecules. This haplotype is known for its susceptibility to certain infections and tumours, making BALB/c mice valuable in cancer and infectious disease studies. For Swiss mice, it is known that the SWR/J inbred sub-strain carries the H-2q haplotype: MHC class I molecules H-2Kq, H-2Dq and class II I-Aq molecules. Some limited information exists on selected antibody clones recognising the H-2q haplotype for applications like flow cytometry, however to date, no information is available regarding the antigen peptide repertoire (immunopeptidome) presented by H-2q MHC molecules. A further complication is that most data for the H-2q haplotype comes from B10 and DBA/1 mice, not Swiss mice. Accordingly, widely used immunopeptidomics tools like NetMHC and MHC Motif Atlas mostly do not provide an opportunity to choose MHC allotypes from the H-2q haplotype. This gap in knowledge limits the full potential of Swiss mice as a genetically diverse model organism in immunological research. By addressing it, we aimed to enhance the utility of Swiss mice, expanding our understanding of strain-specific murine MHC diversity and providing insights into antigen presentation in this strain.

2. Materials and Methods

Mice

Swiss mice were imported into Monash University from the Australian CSL laboratories prior to 1997 and maintained as an isolated colony at the Animal Services Monash University (Asmu) for >28 years. The colony is referred to here as Asmu:Swiss or Swiss mice. A rotational Poiley breeding system was applied throughout to maintain genetic diversity in this outbred population. Further historic information about Australian-bred Swiss lines and their origins has been covered by Cui et al. [

3]. To analyse thymus pre-involution, organs of 20 day old mice were collected for analysis (flow cytometry and immunopeptidomics of adult mice yielded similar results, data not shown). SNP genotyping was performed by Transnetyx/Neogen using the MiniMUGA assay v2.3.13 [

4].

MHC cell surface staining

Swiss mouse spleens were processed into single-cell suspensions, cryopreserved in 90% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (Gibco)/10% dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma-Aldrich) and stored in liquid nitrogen until further use. For flow cytometry, splenocytes were thawed, resuspended and washed twice in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and subsequently stained for MHC surface expression. CT26 (BalbC), DC2.4 (C57BL/6), and 9004 (human) cell lines were used as controls. All incubation steps were performed in the dark on ice, with washing steps carried out by centrifuging the plate at 445 × g between staining steps using FACS buffer (2% fetal calf serum and 2.5 mM Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid in PBS). Briefly, 3 × 10

5 cells were plated into 96-well plates. Splenocytes and control cell lines were first incubated with anti-CD16/CD32 Fc block in cold FACS buffer for 15 min, followed by addition of primary antibodies (refer to

Table 1) for 30 min. MHC-specific antibodies used in this experiment were produced and purified in-house except for M5-114-15-2. Afterwards, cells were washed and incubated with the appropriate secondary antibody (APC or FITC) or FACS buffer for 30 min, followed by another wash. Splenocytes were then stained with CD4 PeCy7, while control cell lines were resuspended in FACS buffer for 15 min. Finally, cells were washed again, resuspended in FACS buffer containing 0.1 µg/ml DAPI, and acquired by flow cytometry using the LSR Fortessa X-20 flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). The data was analysed using FlowJo software, version 10.9.0 (BD Biosciences).

Small scale immunoaffinity purification

To prepare tissue lysates, 400 µL of lysis buffer [0.5% IGEPAL (Sigma Aldrich), 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0, Invitrogen), 150 mM NaCl (Supelco), and one quarter equivalent of a cOmplete™ Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche)] tablet (dissolved in Optima Water, Fisher Chemical) was added to snap-frozen thymus and spleen tissues that were harvested from Swiss mice and stored at -80°C. Tissue disruption was performed using a bead mill (TissueLyser LT, Qiagen) at 50 Hz for 2 minutes. Following homogenization, the lysates were incubated on a tube roller mixer (Ratek) at 4°C for 45 minutes to facilitate complete lysis, then centrifuged at 21,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C. The clarified lysates were transferred to pre-column tubes containing either protein A agarose resin (CaptivA®, Repligen) or protein G agarose resin (pH Scientific). The selection of protein resin was based on the antibody isotype and its known binding affinity to Protein A or G. The mixtures were incubated with gentle rolling for 1 hour at 4°C to remove non-specific binders, after removal of agarose resin the lysate was transferred onto immunoaffinity resin. Immunoaffinity resin were prepared by incubating 100 µL of protein A resin each with 200 µg of the antibodies 28-14-8 (targeting H-2Db, H-2Ld), 34-1-2 (H-2Kd, H-2Dd), and MK-D6 (I-Ad), or 100 µL of protein G resin with 200 µg of the N22 antibody (targeting I-A, I-E) in 2 mL Eppendorf protein LoBind tubes for 1 hr. Unbound antibodies were subsequently removed by washing with 10 mL of 1× PBS twice, using a Poly-Prep® Chromatography Column (Bio-Rad), and aliquoted into Eppendorf LoBind tubes in preparation for immunoprecipitation. Peptide-MHC complexes were captured by rolling one pre-cleared organ lysate with each respective antibody resin (one antibody per lysate) overnight at 4°C. Following the incubation, the peptide-MHC containing affinity resin was loaded onto pre-washed (three times 10% acetic acid, three times with 1× PBS) Mobicol spin columns (MoBiTec GmbH) inserted with a 10 µm pore size filter. The immunoaffinity resin was washed three times with 250 mM NaCl in Optima Water, followed by three washes with 1× PBS. The washing steps were performed with a benchtop mini-centrifuge at 1700 × g to remove detergent and salts. Bound peptide-MHC complexes were eluted in two lots of 200 µL of 10% acetic acid. To liberate the peptides from MHC and antibodies, the eluate was heated to 70°C for 10 minutes using a heat block (Benchmark Scientific isoBlock™) and allowed to cool before being passed through a pre-conditioned (2x wash with 10% acetic acid) 5 kDa centrifugal filter unit (Ultrafree®-MC-PLHCC, Merck Millipore). The filter units were centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 45 minutes, and the peptide eluate flow-through was collected. To recover any residual peptides retained on the filter, an additional 50 µL of 10% acetic acid was added and centrifugation repeated. The filtered peptide eluates were then concentrated using a vacuum centrifugation system (Labconco) and stored at -80°C until further use. Prior to analysis, the concentrated peptide samples were reconstituted in 2% (v/v) acetonitrile (Fisher Chemical), 0.1% (v/v) formic acid (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in Optima Water with a mixture of 11 iRT peptides (Biognosys) spiked in to aid retention time alignment [

5]. The peptide samples were sonicated for 10 minutes, centrifuged at 21,000 × g and loaded onto the EvoSep liquid chromatography system to be analysed by Bruker timsTOF Pro2 (Bruker Daltonics).

Mass spectrometry

Samples were analysed using a hybrid trapped ion mobility-quadrupole time of flight mass spectrometer (Bruker timsTOF Pro 2, Bruker Daltonics) coupled to EvoSep liquid chromatography system. The HLA ligands were loaded onto an IonOpticks Aurora Elite column (15 cm x 75um x 1.7 um, of 120 A pore size) and separated using a Zoom Whisper 20 SPD method. Data dependent acquisition was performed with the following settings: m/z range: 100-1700mz, capillary voltage:1600V, Target intensity of 30000, TIMS ramp of 0.60 to 1.60 Vs/cm 2 for 166 ms.

LC-MS/MS Data Analysis

In lack of a specific Swiss mouse proteome, LC-MS/MS data was searched using PEAKS Online 11 (Bioinformatics Solutions Inc.) against the reference Mus musculus proteome 10090 (Uniprot/Swissprot v2023) and a contaminant database containing iRT reference peptides plus the Protein A sequence. Peptide identities were subject to strict bioinformatic criteria including the use of a decoy database to calculate the peptide false discovery rate (FDR) of 5%. The following search parameters were used: peptide length 6-30, no cysteine alkylation, no enzyme digestion (considers all peptide bond cleavages), instrument-specific settings for TimsTOF Pro 2 (parent and fragment ion tolerance of 20 ppm and 0.02 Da respectively), variable modifications set to: oxidation of M, Acetylation N-term and deamidation of NQ. Additionally, Peaks PTM search was performed after a Peaks DB search with all default in-built modifications with the same mass tolerance settings as Peaks DB. Immunolyser was used for visualization of results [

6]. Reference motifs were extracted from

https://services.healthtech.dtu.dk/services/NetMHC-4.0/ and

https://services.healthtech.dtu.dk/services/NetMHCIIpan-4.0/ [

7,

8].

3. Results

3.1. SNP Genotyping of Swiss Mice

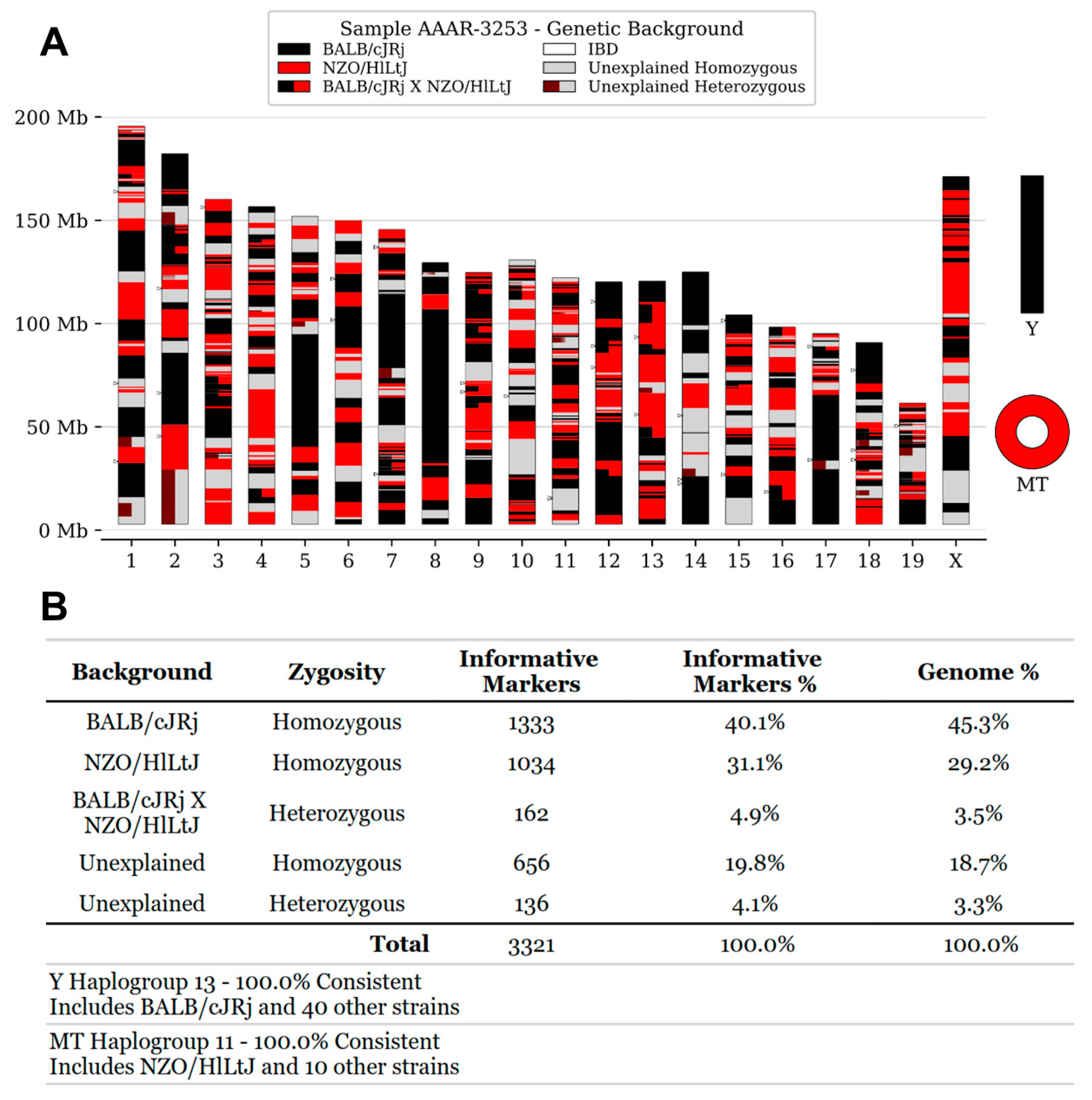

In order to establish the genetic background of the Swiss:Asmu colony held at our facility, we performed SNP genotyping on three mice from this strain using the published MiniMUGA genotyping array3. The results confirmed that the strain was outbred. Overall, 42-46% of the genome was consistent with the BALB/cJRj background, 29-32% of the genome was most consistent with either NZW/LacJ or NZO/HlLtJ background, 3-4% of the loci were heterozygous for BalbC x NZW/NZO while 22% of the genome contained unique genomic material that could not be matched to known strains in the database (

Figure 1). Therefore, the genotyping results confirmed that the Swiss:Asmu mouse strain is outbred with a high diversity and numerous genetic variations within the colony.

3.2. Identification of Established anti-MHC Antibody Clones Capable of Cross-Reactivity with Swiss Cells

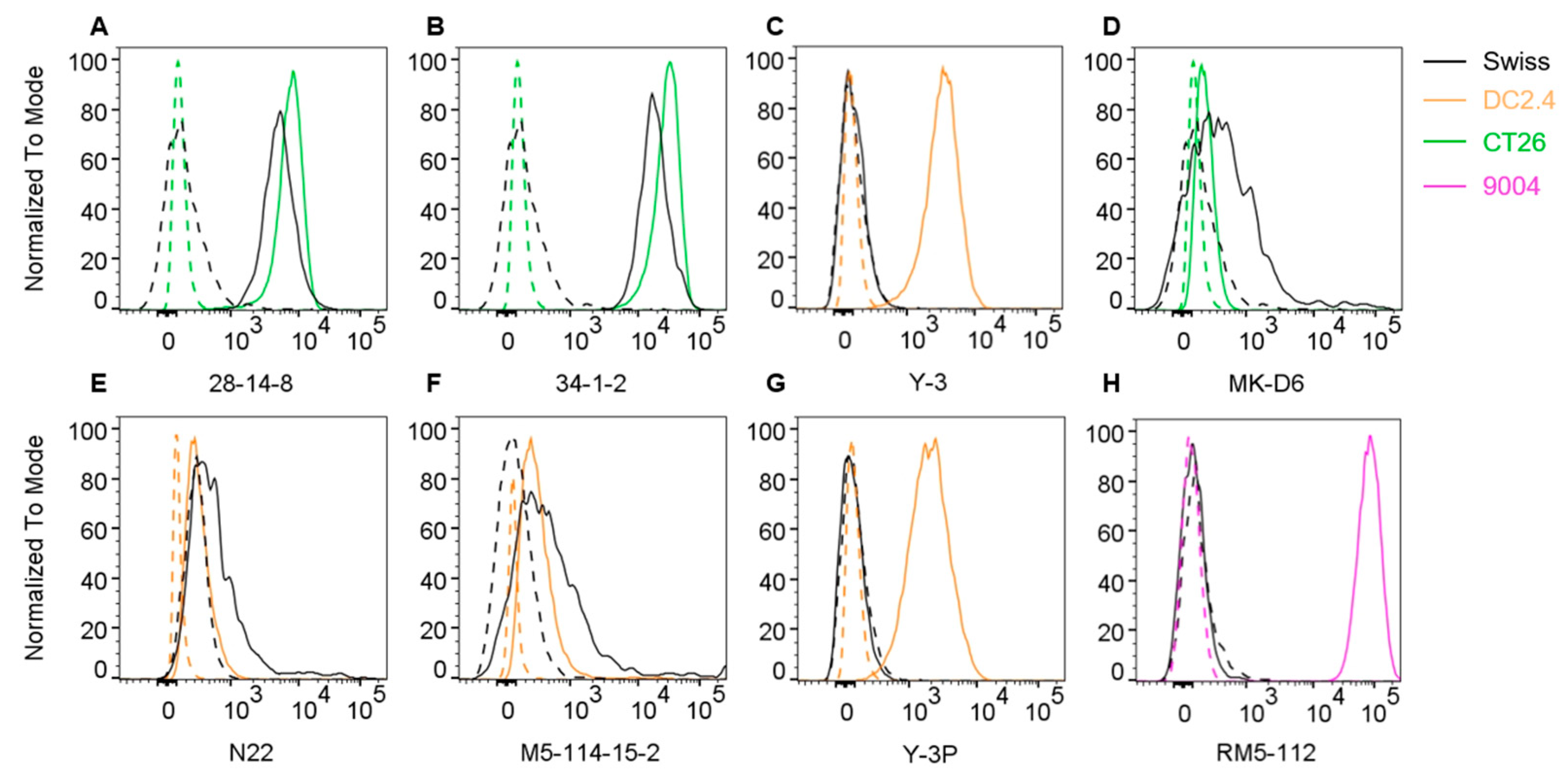

In order to identify antibodies able to detect MHC class I and MHC class II molecules in Swiss mice, we performed flow cytometric staining of Swiss mouse splenocytes with a range of antibodies known to detect MHC allotypes across a range of different strains of mice (

Figure 2, gating in

Figure S1). First we tested the 28-14-8 antibody (also known as 28-14-8.S) which binds to the α3 domain of H-2Db and has also been reported to cross-react with H-2Ld, H-2Dq and H-2Lq but not H-2Kd or H-2Dd [

9]. The data on its reactivity with H-2q genes was previously reported based on the staining of cells from B10.AKM, B10.MBR and DBA/1 mice. We found that the antibody was indeed also able to stain Swiss splenocytes (

Figure 2A). Next, we analysed the 34-1-2 antibody (also known as 34-1-2.S) which binds H-2Kd and H-2Dd. It also cross-reacts with other MHC class I allotypes such as H-2Kb/s/r/p/q, the cross-reactivity to H-2q genes was originally determined based on reactivity with B10.A mice [

10]. We could confirm that the 34-1-2 antibody was able to stain Swiss splenocytes (

Figure 2B). In addition, we tested the highly H-2Kb specific antibody Y-3 which does not cross-react with H-2Kd, Y-3 did not produce a staining on Swiss cells (

Figure 2C).

After establishing that two anti-MHC I antibodies, 28-12-8 and 34-1-2, can be used to detect MHC I in Swiss mice, we moved on to test anti-MHC II antibodies. The MK-D6 antibody was raised against B10.D2 splenocytes as an immunogen, it recognises specifically I-Ad and does not react with I-Ak, I-Ab, I-As, I-Af or I-Aa [

11]. In this study, we could show that it does react with I-Aq of Swiss mice (

Figure 2D). We also tested the N22 antibody which is known to interact with a monomorphic part of I-A and I-E molecules [

12]. We found that Swiss splenocytes could be successfully stained with N22 (

Figure 2E). Next, the M5/114.15.2 antibody was tested. It reacts with a polymorphic epitope on I-Ab, I-Ad, I-Aq, I-Ed, I-Ek, but not I-Af, I-Ak, or I-As [

13,

14]. Swiss cells stained with M5/114.15.2 while other anti-MHC-II antibodies such as Y-3P (reacts with I-Ab/f/p/q/r/s/u/v haplotypes and weakly with I-Ak as well as rat I-A like molecules) and RM5-112 (pan-HLA class II β-chain) did not produce a staining on Swiss splenocytes (

Figure 2F-H) [

15].

Based on our flow cytometric analysis, we progressed with the antibodies 28-14-8 and 34-1-2 for MHC class I capture as well as MK-D6 and N22 for MHC class II affinity purification in following experiments.

3.3. Immunopeptidomic Analysis in Swiss Mice

Next, we wanted to assess the characteristics of MHC-bound peptides in Swiss mice via immunopeptidomic affinity purification experiments. The workflow was similar to previously published detailed protocols from our lab, but included a tissue disruption step in cell lysis buffer (

Figure 3) [

1,

16,

17]. In brief, frozen organs were added to 400 µl cold lysis buffer and dissociated at 50 Hz for 2 min in Tissuelyser LT. The lysate was rolled at 4°C for 45 min, nuclei spun down and the lysate co-incubated with anti-MHC antibodies bound to Protein A/G resin. Peptide-MHC complexes were eluted with 10% acetic acid and peptides isolated using 5 kDa molecular weight cut-off filters prior to mass spectrometric analysis.

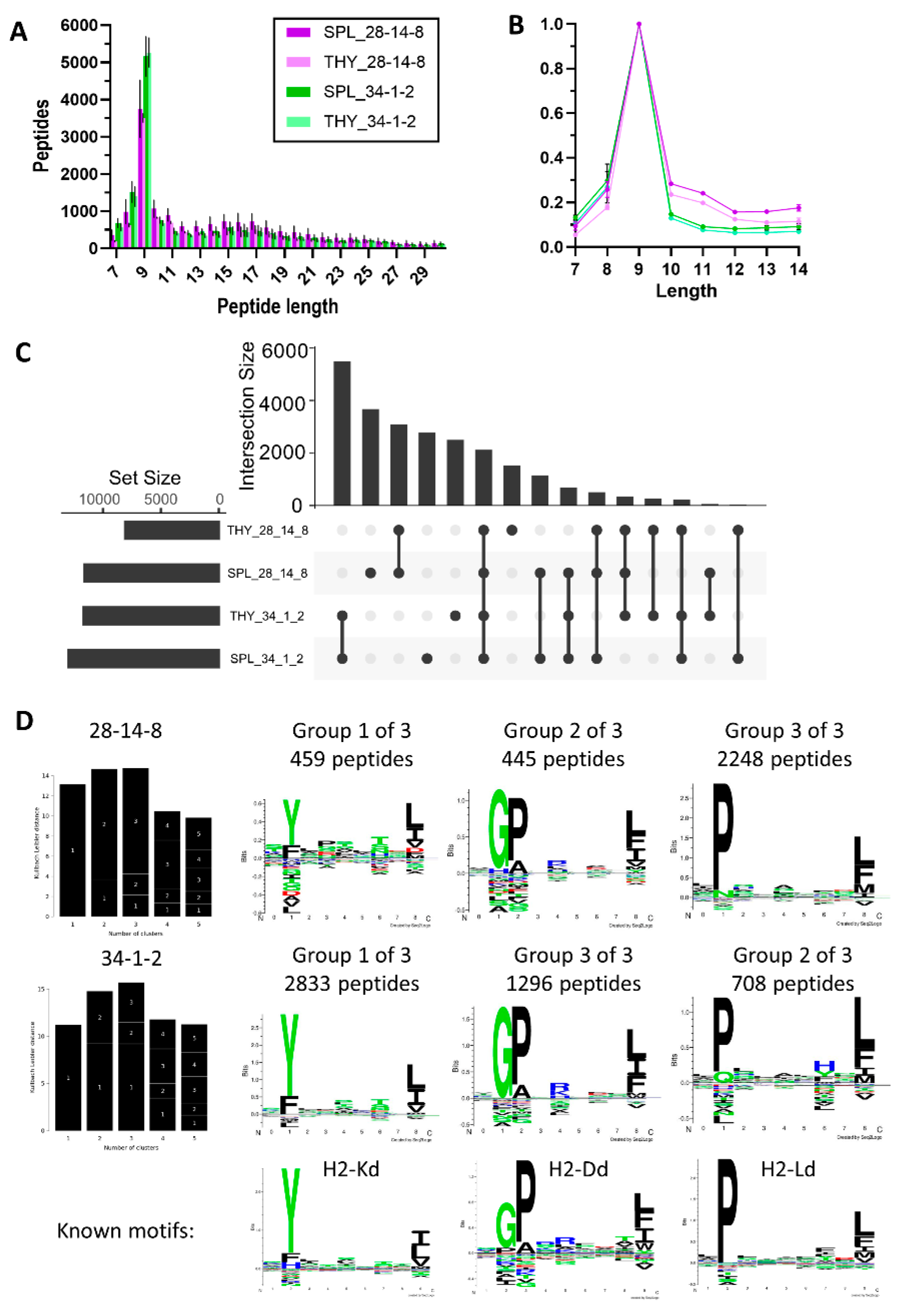

Peptides eluted with the anti-MHC I antibodies 28-12-8 and 34-1-2 in both cases showed a preference for 9-mers as is expected for MHC I-bound peptides (

Figure 4A), although peptides eluted with 28-14-8 contained a higher proportion of longer peptides (

Figure 4B). Overlap analysis revealed that there was a high proportion of antibody-specific captured MHC ligands, but also a significant number of shared peptides (

Figure 4C). To explore the characteristics of the isolated peptides further, we performed Gibbs cluster analysis which allows to identify subsets of peptides contained within a dataset. For both antibodies, a division into three clusters was the best fit and both antibodies pulled down the same three clusters of peptides (

Figure 4D). When comparing the cluster motifs with published and deposited immunopeptidome data from other mouse strains, they showed a close match to H-2Kd, H-2Dd and H-2Ld (

Figure 4D, bottom panel). It needs to be noted that 28-14-8 preferentially pulls down peptides in line with the H2-L allotype, while 34-1-2 preferentially captures peptides that align mostly with the H2-K motif and a significant proportion of peptides with a H2-D motif.

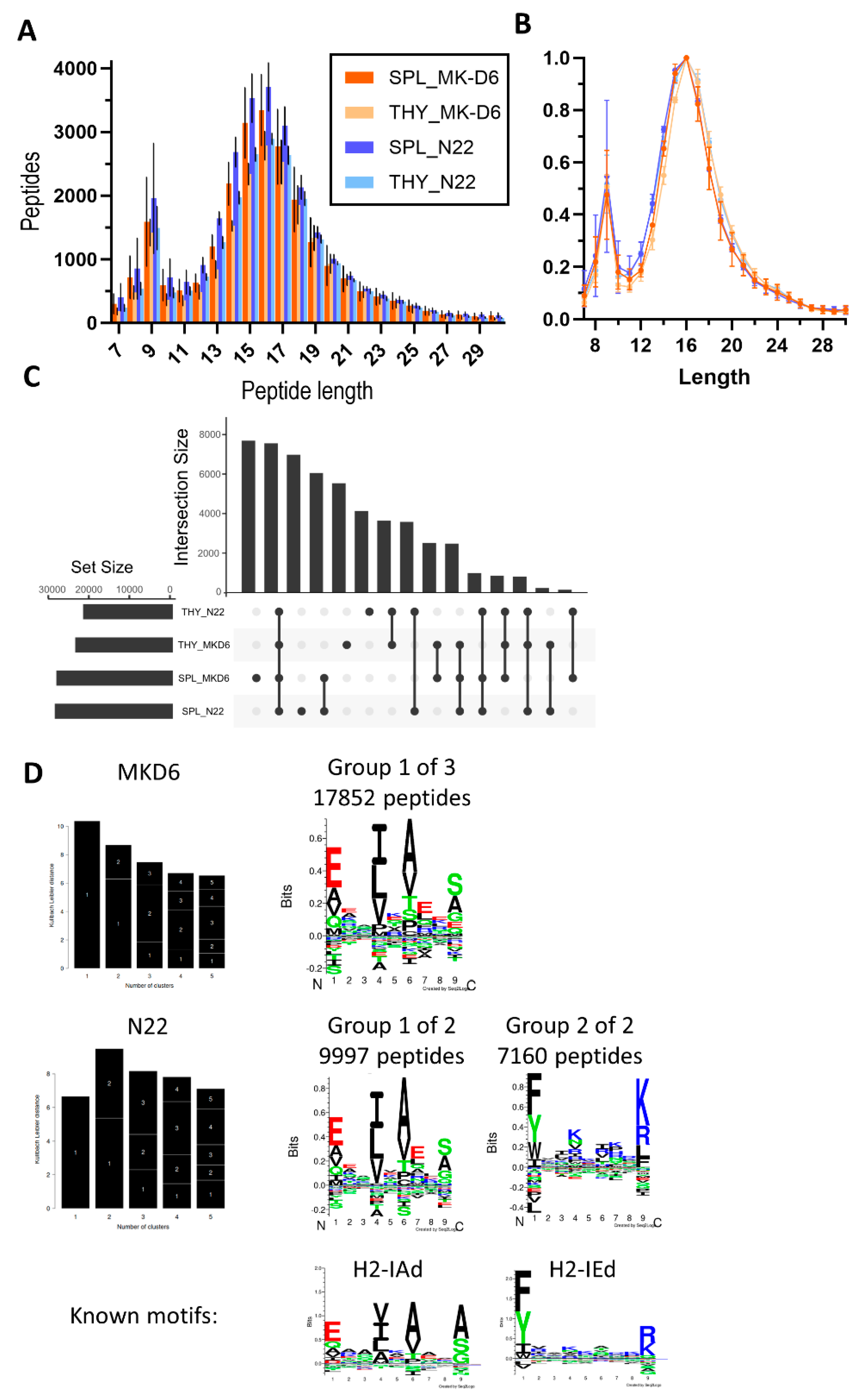

In order to isolate the MHC II-bound immunopeptidome, we chose the MK-D6 and N22 antibody clones. Both antibodies predominantly captured longer peptides, as is typical for MHC II-derived peptides, with 16-mers constituting the predominant length (

Figure 5A). However, a considerable contamination of shorter MHC I peptides could be observed, resulting in a second peak around 8-10-mers (

Figure 5A,B). Therefore, to analyse the peptide overlap between these antibodies, we filtered for 12-25-mers first, before generating an Upset plot. There was substantial overlap in peptides captured by both antibodies and main groups of unique peptides were attributed to source organ rather than antibody type (

Figure 5C). Accordingly, Gibbs clustering revealed the same peptide motif for both antibodies which is in line with the published H2-IAd motif. However, N22 is also capable of capturing a second group of distinct peptides that display a motif in line with H2-IEd.

4. Discussion

This study provides information on antibodies able to recognise and isolate various MHC class I and class II alleles in Swiss mice. We identified that the anti-MHC I antibodies 28-14-8 and 34-1-2 both capture all three major class I alleles, yet together are rather complementary. While 34-1-2 preferably binds to and captures H2-K and H2D-derived peptides, 28-14-8 is detecting predominantly H2-L alleles. Both antibodies are highly specific to class I MHC molecules. However, for the anti-MHC II antibodies MKD6 and N22 substantial amounts of shorter MHC I peptides are co-isolated which contain H-2K, H-2D and H-2L motifs in similar proportions. For MHC II immunopeptidome capture, it could therefore be recommended to design elution experiments in a tandem setup by first depleting MHC class I peptides using a mix of 28-14-8 and 34-1-2 followed by incubation of the remaining cell lysate with anti-MHC class II antibodies. MKD6 can we used where exclusive capture of H2-IA is sought while N22 is a preferred choice if both, H2-IA and H2-IE, need to be isolated.

The motif analysis of all antibodies revealed that the H2-q haplotype of Swiss:Asmu mice is similar to the H2-d haplotype of BalbC mice. To date, only very limited genomic sequencing data exists for the Swiss strain and the only available MHC I protein sequence from the H2-q haplotype, is the H2-Kq protein accession (P14428.1) derived from Swiss SWR mice. It displays 98% homology to the H2-Kd protein accession (P01902.1) derived from BalbC/J mice [

18,

19]. The here seen high similarities in the presented peptides by the H2-q and H2-d haplotypes are also in line with the previously reported cross-reactivity of some antibodies between these two haplotype strains that we could confirm in our flow cytometric analysis. Furthermore, it is in line with the genomic miniMUGA analysis which found that the MHC-gene containing region on chromosome 17 aligns best with the genomic background of the Balb/cJRj strain.

Overall, this study aids in developing a better understanding of MHC diversity in mice and helps to shed light on antigen presentation in the Swiss mouse strain that is used across different areas of medical research.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Investigation, A.C., I.K.-J., S.E.G., R.S., N.H.L., L.A.C. Conceptualisation A.B., A.W.P., methodology A.W.P., A.C., resources, A.W.P., writing – original draft A.B; writing—review and editing, all authors.; analysis and visualization, A.C., A.B..; supervision, A.B., A.W.P., L.A.C., J.F.B;. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by NH&MRC, grant numbers 2018897 (JFB) and 2016596 (AWP).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Monash University (protocol code AE36630). Wild-type Asmu:Swiss mice were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions at the Animal Research Laboratory (ARL) of Monash University.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Any additional data not contained in the manuscript will be made available upon reasonable request to the authors.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the entire Monash Animal Research Laboratory team, especially Cherelle Baldock for help in retrieving historic Swiss strain genealogy records.

Conflicts of Interest

AWP is a member of the scientific advisory board (SAB) of Bioinformatic Solutions Inc. (Canada) and is a shareholder and SAB member of Evaxion Biotech (Denmark). He is a co-founder of Resseptor Therapeutics (Australia). None of these entities had any influence on this publication.

References

- Purcell, A.W.; Ramarathinam, S.H.; Ternette, N. Mass spectrometry-based identification of MHC-bound peptides for immunopeptidomics. Nat Protoc 2019, 14, 1687-1707. [CrossRef]

- Rice, M.C.; O’Brien, S.J. Genetic variance of laboratory outbred Swiss mice. Nature 1980, 283, 157-161. [CrossRef]

- Cui, S.; Chesson, C.; Hope, R. Genetic variation within and between strains of outbred Swiss mice. Lab Anim 1993, 27, 116-123. [CrossRef]

- Sigmon, J.S.; Blanchard, M.W.; Baric, R.S.; Bell, T.A.; Brennan, J.; Brockmann, G.A.; Burks, A.W.; Calabrese, J.M.; Caron, K.M.; Cheney, R.E.; et al. Content and Performance of the MiniMUGA Genotyping Array: A New Tool To Improve Rigor and Reproducibility in Mouse Research. Genetics 2020, 216, 905-930. [CrossRef]

- Escher, C.; Reiter, L.; MacLean, B.; Ossola, R.; Herzog, F.; Chilton, J.; MacCoss, M.J.; Rinner, O. Using iRT, a normalized retention time for more targeted measurement of peptides. Proteomics 2012, 12, 1111-1121. [CrossRef]

- Munday, P.R.; Fehring, J.; Revote, J.; Pandey, K.; Shahbazy, M.; Scull, K.E.; Ramarathinam, S.H.; Faridi, P.; Croft, N.P.; Braun, A.; et al. Immunolyser: A web-based computational pipeline for analysing and mining immunopeptidomic data. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 2023, 21, 1678-1687. [CrossRef]

- Andreatta, M.; Nielsen, M. Gapped sequence alignment using artificial neural networks: application to the MHC class I system. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 511-517. [CrossRef]

- Reynisson, B.; Barra, C.; Kaabinejadian, S.; Hildebrand, W.H.; Peters, B.; Nielsen, M. Improved Prediction of MHC II Antigen Presentation through Integration and Motif Deconvolution of Mass Spectrometry MHC Eluted Ligand Data. J Proteome Res 2020, 19, 2304-2315. [CrossRef]

- Ozato, K.; Hansen, T.H.; Sachs, D.H. Monoclonal antibodies to mouse MHC antigens. II. Antibodies to the H-2Ld antigen, the products of a third polymorphic locus of the mouse major histocompatibility complex. J Immunol 1980, 125, 2473-2477. [CrossRef]

- Sharrow, S.O.; Flaherty, L.; Sachs, D.H. Serologic cross-reactivity between Class I MHC molecules and an H-2-linked differentiation antigen as detected by monoclonal antibodies. J Exp Med 1984, 159, 21-40. [CrossRef]

- Kappler, J.W.; Skidmore, B.; White, J.; Marrack, P. Antigen-inducible, H-2-restricted, interleukin-2-producing T cell hybridomas. Lack of independent antigen and H-2 recognition. J Exp Med 1981, 153, 1198-1214. [CrossRef]

- Metlay, J.P.; Witmer-Pack, M.D.; Agger, R.; Crowley, M.T.; Lawless, D.; Steinman, R.M. The distinct leukocyte integrins of mouse spleen dendritic cells as identified with new hamster monoclonal antibodies. J Exp Med 1990, 171, 1753-1771. [CrossRef]

- Braunstein, N.S.; Germain, R.N.; Loney, K.; Berkowitz, N. Structurally interdependent and independent regions of allelic polymorphism in class II MHC molecules. Implications for Ia function and evolution. J Immunol 1990, 145, 1635-1645. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, A.; Dorf, M.E.; Springer, T.A. A shared alloantigenic determinant on Ia antigens encoded by the I-A and I-E subregions: evidence for I region gene duplication. J Immunol 1981, 127, 2488-2495. [CrossRef]

- Russ, G.R.; Pascoe, V.; d’Apice, A.J.; Seymour, A.E. Expression of HLA-DR, -DQ, and -DP antigens on renal tubular cells during rejection episodes. Transplant Proc 1986, 18, 293-297.

- Braun, A.; Rowntree, L.C.; Huang, Z.; Pandey, K.; Thuesen, N.; Li, C.; Petersen, J.; Littler, D.R.; Raji, S.; Nguyen, T.H.O.; et al. Mapping the immunopeptidome of seven SARS-CoV-2 antigens across common HLA haplotypes. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 7547. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, K.; Ramarathinam, S.H.; Purcell, A.W. Isolation of HLA Bound Peptides by Immunoaffinity Capture and Identification by Mass Spectrometry. Curr Protoc 2021, 1, e92. [CrossRef]

- Kress, M.; Glaros, D.; Khoury, G.; Jay, G. Alternative RNA splicing in expression of the H-2K gene. Nature 1983, 306, 602-604. [CrossRef]

- Morita, T.; Delarbre, C.; Kress, M.; Kourilsky, P.; Gachelin, G. An H-2K gene of the tw32 mutant at the T/t complex is a close parent of an H-2Kq gene. Immunogenetics 1985, 21, 367-383. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).