Submitted:

02 March 2025

Posted:

03 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Statement

2.2. Viruses

2.3. Animal Experiments

2.4. Hemagglutination Inhibition Test

2.5. Immunohistochemical and Histopathological Studies

2.6. Lectin Staining Assay

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

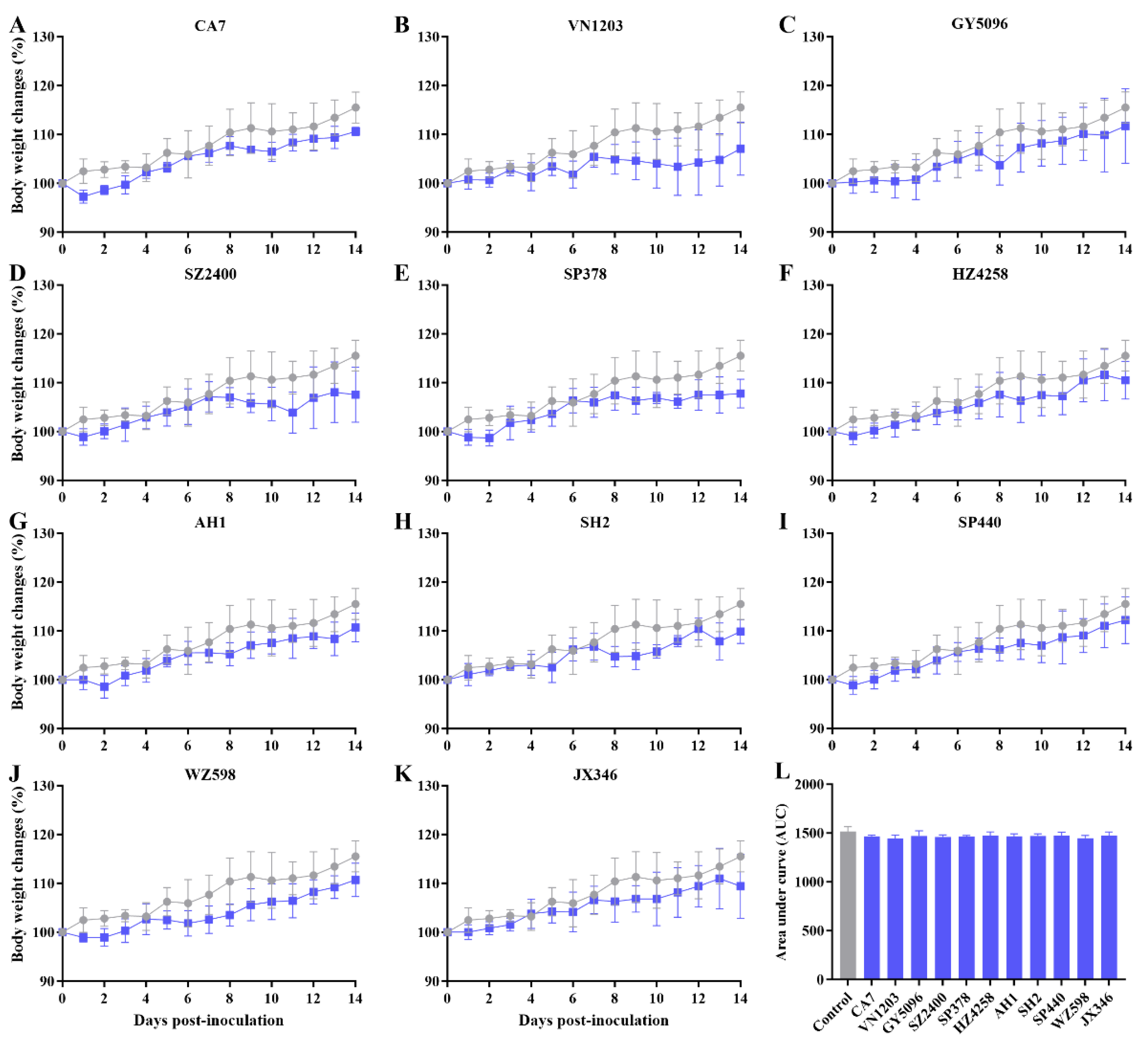

3.1. Asymptomatic Infection with IAVs in SD Rats

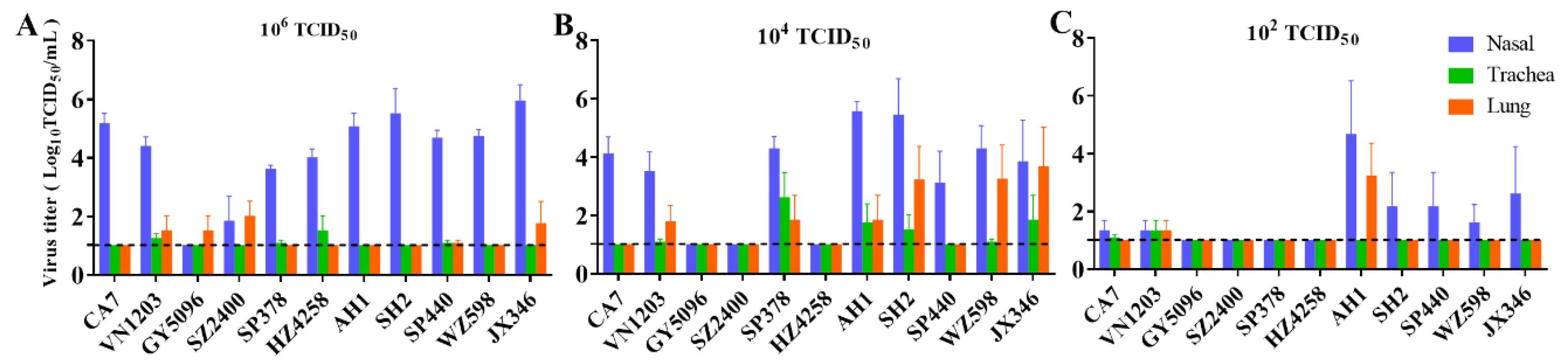

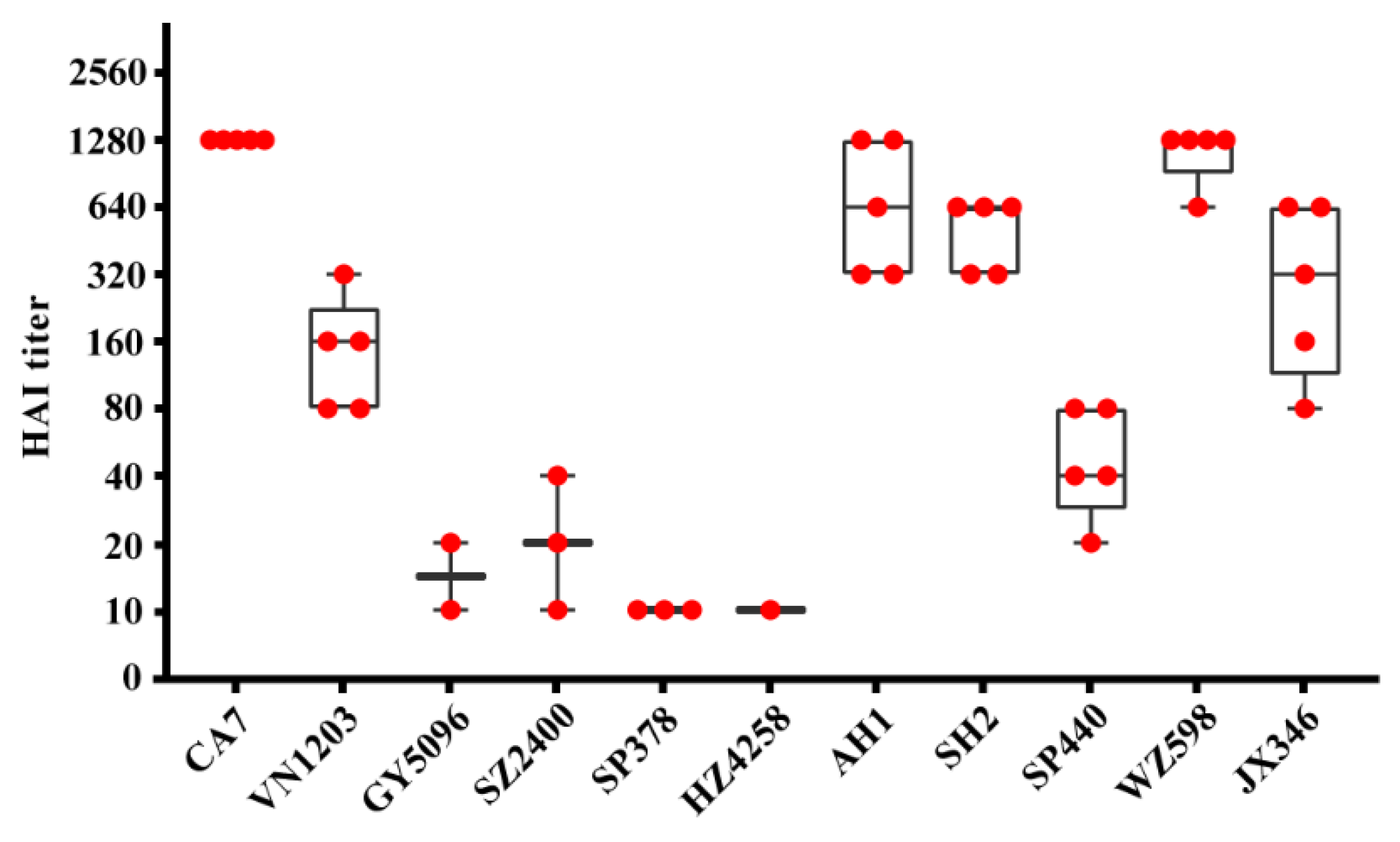

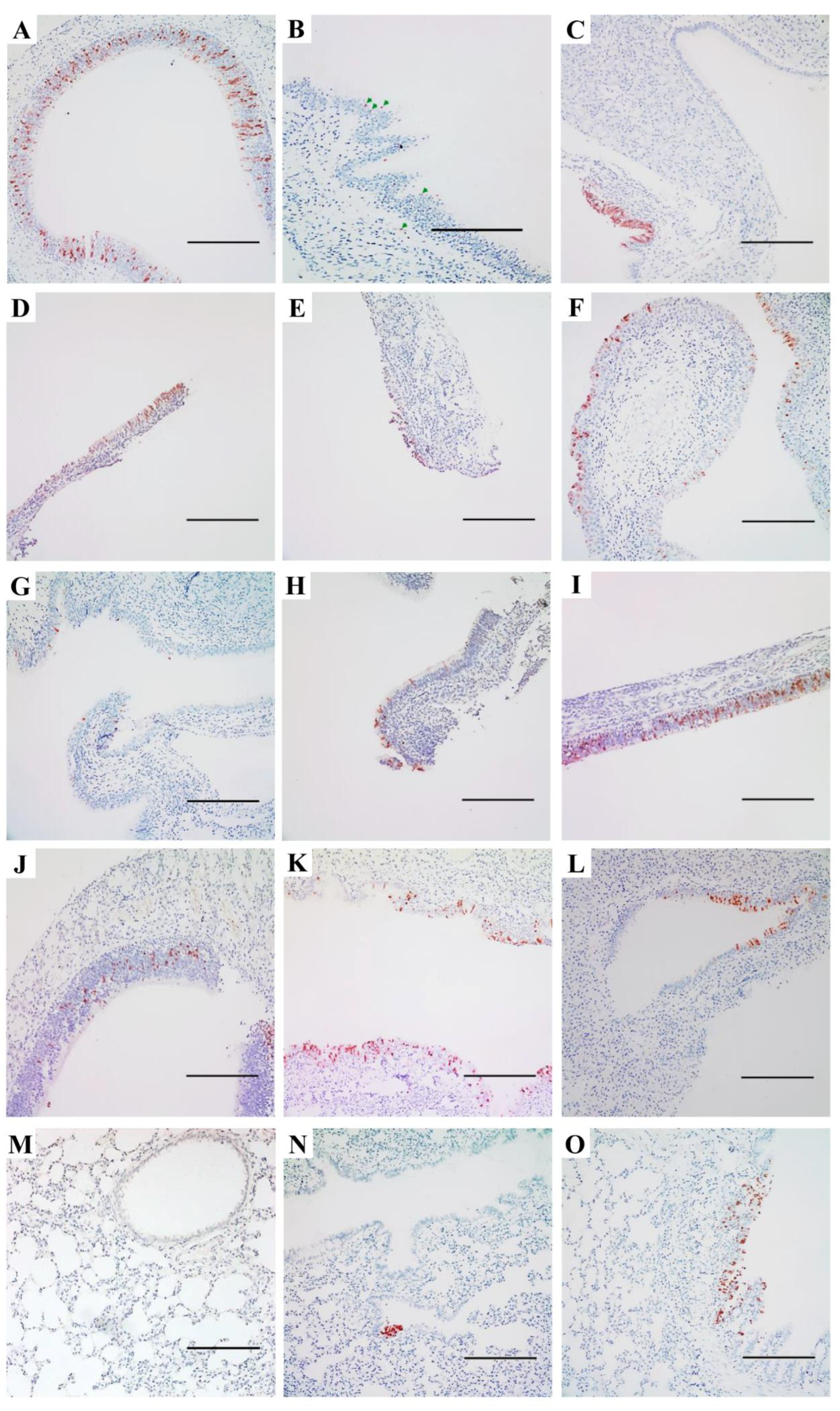

3.2. Replication and Distribution of Different IAVs in the Rat Respiratory Tract

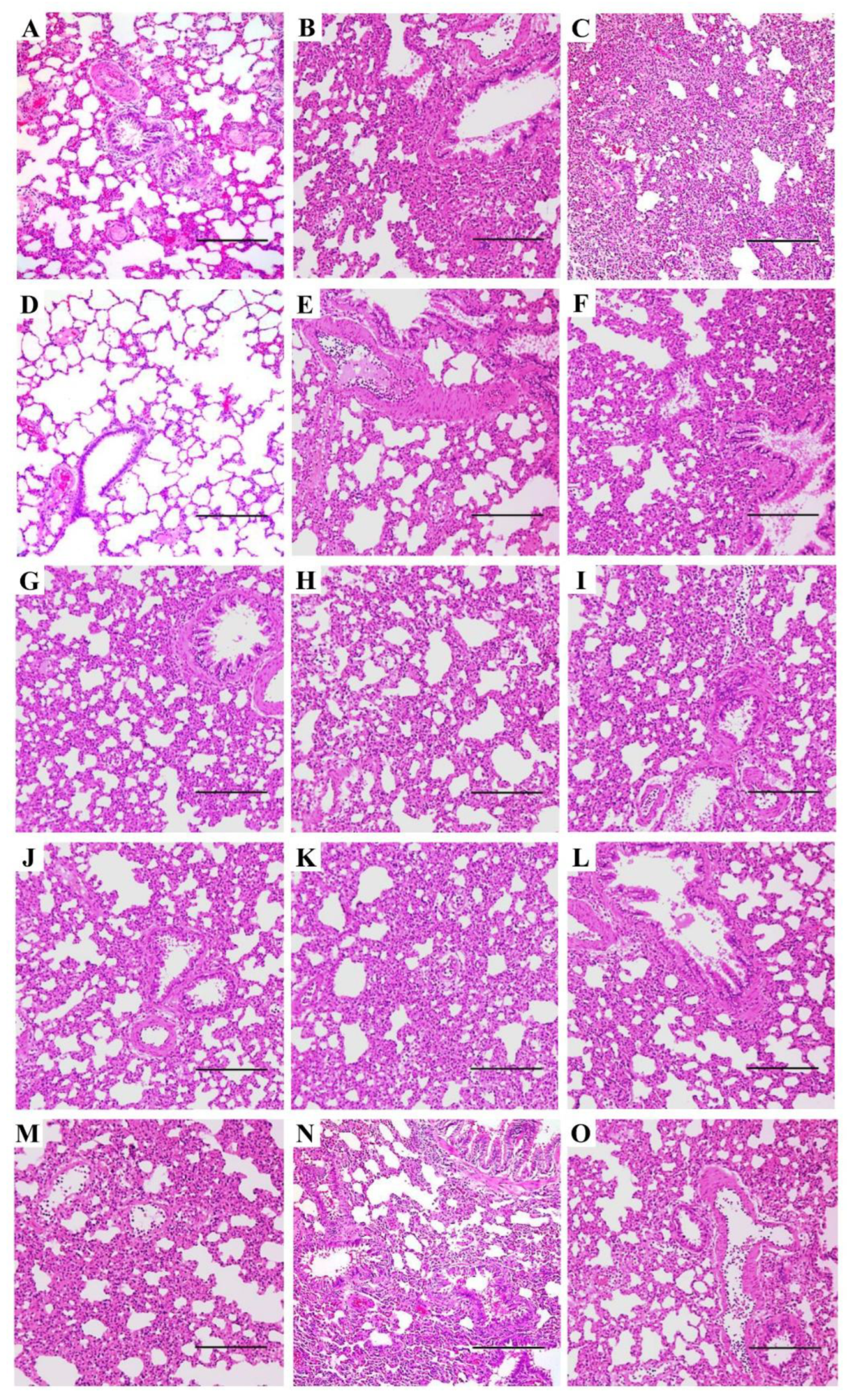

3.3. Pneumonia and Histopathological Changes Induced by IAVs in SD Rats

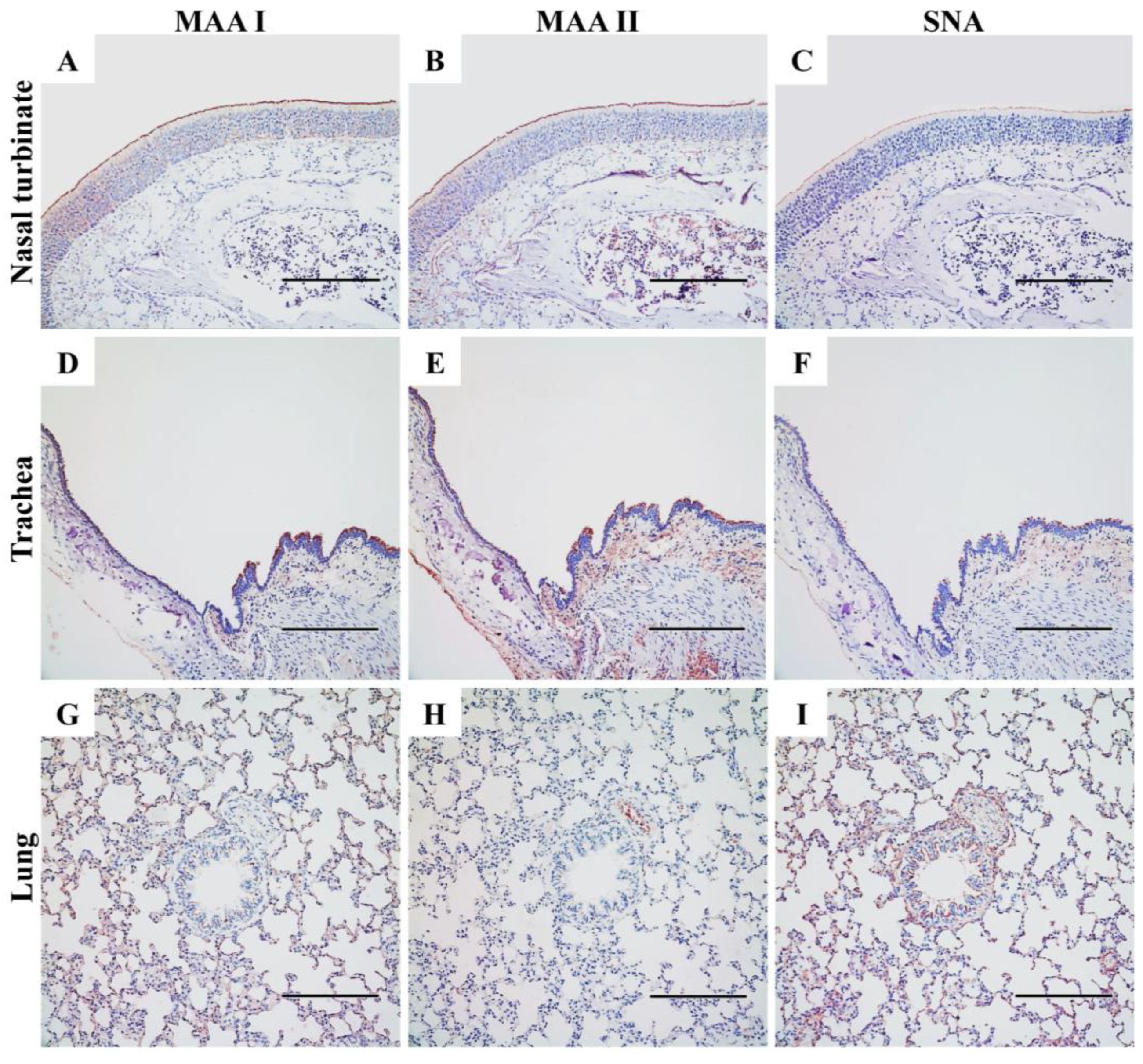

3.4. Expression of Sialic Acid-Linked Receptors in the Respiratory Tract of SD Rats

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IAV | influenza A virus |

| HPAI | highly pathogenic avian influenza |

| LPAI | low pathogenic avian influenza |

| BSL-3 | Biosafety Level 3 |

| MDCK | Madin-Darby canine kidney |

| CA7 | A/California/07/2009 |

| VN1203 | A/Vietnam/1203/2004 |

| GY5096 | A/Duck/Guiyang/5096/2013 |

| SZ2400 | A/Chicken/Shenzhen/2400/2013 |

| SP378 | A/Shenzhen/SP378/2015 |

| HZ4258 | A/Duck/Huzhou/4258/2013 |

| AH1 | A/Anhui/1/2013 |

| SH2 | A/Shanghai/2/2013 |

| SP440 | A/Guangdong/SP440/2017 |

| WZ598 | A/Chicken/Wenzhou/598/2013 |

| JX346 | A/Jiangxi-Donghu/346/2013 |

| SPF | specific-pathogen-free |

| SD | Sprague-Dawley |

| TCID50 | 50% tissue culture infectious dose |

| dpi | day(s) post-inoculation |

| RDE | receptor-destroying enzyme |

| HAI | hemagglutination inhibition |

| TRBC | turkey red blood cell |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| IHC | immuno-histochemical |

| H&E | hematoxylin and eosin |

| NP | nucleoprotein |

| SA | sialic acid |

| MAA | Maackia amurensis agglutinin |

| SNA | Sambucus nigra agglutinin |

| AUC | area under the curve |

| ANOVA | one-way analysis of variance |

| pdmH1N1 | pandemic 2009 H1N1 |

| mTEDC | mouse tracheal epithelial cells |

| RNA | ribonucleic acid |

References

- Smith, G.J.; Vijaykrishna, D.; Bahl, J.; Lycett, S.J.; Worobey, M.; Pybus, O.G.; Ma, S.K.; Cheung, C.L.; Raghwani, J.; Bhatt, S.; et al. Origins and evolutionary genomics of the 2009 swine-origin H1N1 influenza A epidemic. Nature 2009, 459, 1122–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, R.; Cao, B.; Hu, Y.; Feng, Z.; Wang, D.; Hu, W.; Chen, J.; Jie, Z.; Qiu, H.; Xu, K.; et al. Human infection with a novel avian-origin influenza A (H7N9) virus. N Engl J Med 2013, 368, 1888–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Influenza Programme. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-influenza-programme/avian-influenza/monthly-risk-assessment-summary (accessed on 27 February, 2025).

- Webster, R.G.; Bean, W.J.; Gorman, O.T.; Chambers, T.M.; Kawaoka, Y. Evolution and ecology of influenza A viruses. Microbiol Rev 1992, 56, 152–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.W.; Webby, R.J.; Webster, R.G. Evolution and ecology of influenza A viruses. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2014, 385, 359–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, D.K.W.; Perera, R.; Ali, A.; Oladipo, J.O.; Mamo, G.; So, R.T.Y.; Zhou, Z.; Chor, Y.Y.; Chan, C.K.; Belay, D.; et al. Influenza A Virus Infections in Dromedary Camels, Nigeria and Ethiopia, 2015-2017. Emerg Infect Dis 2020, 26, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, C.D.; Icochea, M.E.; Espejo, V.; Troncos, G.; Castro-Sanguinetti, G.R.; Schilling, M.A.; Tinoco, Y. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) from Wild Birds, Poultry, and Mammals, Peru. Emerg Infect Dis 2023, 29, 2572–2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mok, C.K.P.; Qin, K. Mink infection with influenza A viruses: an ignored intermediate host? One Health Adv 2023, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrough, E.R.; Magstadt, D.R.; Petersen, B.; Timmermans, S.J.; Gauger, P.C.; Zhang, J.; Siepker, C.; Mainenti, M.; Li, G.; Thompson, A.C.; et al. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Clade 2.3.4.4b Virus Infection in Domestic Dairy Cattle and Cats, United States, 2024. Emerg Infect Dis 2024, 30, 1335–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velkers, F.C.; Blokhuis, S.J.; Veldhuis Kroeze, E.J.B.; Burt, S.A. The role of rodents in avian influenza outbreaks in poultry farms: a review. Vet Q 2017, 37, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, T.M.; Lundkvist, Å. Rat-borne diseases at the horizon. A systematic review on infectious agents carried by rats in Europe 1995-2016. Infect Ecol Epidemiol 2019, 9, 1553461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shortridge, K.F.; Gao, P.; Guan, Y.; Ito, T.; Kawaoka, Y.; Markwell, D.; Takada, A.; Webster, R.G. Interspecies transmission of influenza viruses: H5N1 virus and a Hong Kong SAR perspective. Vet Microbiol 2000, 74, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, A.; Prince, A.; Fawzy, A.; Nadra, E.; Abdou, M.I.; Omar, L.; Fayed, A.; Salem, M. Sero-prevalence of avian influenza in animals and human in Egypt. Pak J Biol Sci 2013, 16, 524–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummings, C.O.; Hill, N.J.; Puryear, W.B.; Rogers, B.; Mukherjee, J.; Leibler, J.H.; Rosenbaum, M.H.; Runstadler, J.A. Evidence of Influenza A in Wild Norway Rats (Rattus norvegicus) in Boston, Massachusetts. Front Ecol Evol 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, W.; Gao, Y.; Wen, Y.; Ke, X.; Ou, Z.; Li, Y.; He, H.; Chen, Q. Detection of Virus-Related Sequences Associated With Potential Etiologies of Hepatitis in Liver Tissue Samples From Rats, Mice, Shrews, and Bats. Front Microbiol 2021, 12, 653873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camp, J.V.; Desvars-Larrive, A.; Nowotny, N.; Walzer, C. Monitoring Urban Zoonotic Virus Activity: Are City Rats a Promising Surveillance Tool for Emerging Viruses? Viruses 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, J.W.; Zhang, X.L.; Sun, J.; Liu, H.; Chen, J.M. Infection of wild rats with H5N6 subtype highly pathogenic avian influenza virus in China. J Infect 2023, 86, e117–e119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, M.I.; Maassab, H.F.; Jennings, R.; Potter, C.W. Influenza virus infection of a newborn rats: virulence of recombinant strains prepared from a cold-adapted, attenuated parent. Arch Virol 1979, 61, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, M.J.; Selgrade, M.K.; Doerfler, D.; Gilmour, M.I. Kinetic profile of influenza virus infection in three rat strains. Comp Med 2003, 53, 293–298. [Google Scholar]

- Marchenko, V.; Zelinskaya, I.; Toropova, Y.; Shmakova, T.; Podyacheva, E.; Lioznov, D.; Zhilinskaya, I.N. Influenza A Virus Causes Histopathological Changes and Impairment in Functional Activity of Blood Vessels in Different Vascular Beds. Viruses 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaels, R.H.; Mahmud, M.I.; Coup, A.J.; Jennings, R.; Potter, C.W. Influenza virus infection in newborn rats: a possible marker of attenuation for man. J Med Virol 1978, 2, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, R.; Potter, C.W.; Teh, C.Z.; Mahmud, M.I. The replication of type A influenza viruses in the infant rat: a marker for virus attenuation. J Gen Virol 1980, 49, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teh, C.; Jennings, R.; Potter, C.W. Influenza virus infection of newborn rats: virulence of recombinant strains prepared from influenza virus strain A/Okuda/57. J Med Microbiol 1980, 13, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhur, A.; Galan, P.; Hannoun, C.; Huot, K.; Hercberg, S. Effects of iron deficiency upon the antibody response to influenza virus in rats. J Nutr Biochem 1990, 1, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaciong, Z.; Alexiewicz, J.M.; Massry, S.G. Impaired in vivo antibody production in CRF rats: role of secondary hyperparathyroidism. Kidney Int 1991, 40, 862–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, M.L. Urbanization as a major cause of biotic homogenization. Biological Conservation 2006, 127, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, A.Y.T.; Himsworth, C.G. The secret life of the city rat: a review of the ecology of urban Norway and black rats (Rattus norvegicus and Rattus rattus). Urban Ecosystems 2014, 17, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Global Influenza Surveillance Network. Manual for the laboratory diagnosis and virological surveillance of influenza. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/manual-for-the-laboratory-diagnosis-and-virological-surveillance-of-influenza (accessed on 27 February, 2025).

- Zhu, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, P.; Song, W.; Zheng, Z.; Chen, R.; Guo, K.; Zhang, T.; Peiris, J.S.; Chen, H.; et al. Substitution of lysine at 627 position in PB2 protein does not change virulence of the 2009 pandemic H1N1 virus in mice. Virology 2010, 401, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Wang, D.; Kelvin, D.J.; Li, L.; Zheng, Z.; Yoon, S.W.; Wong, S.S.; Farooqui, A.; Wang, J.; Banner, D.; et al. Infectivity, transmission, and pathology of human-isolated H7N9 influenza virus in ferrets and pigs. Science 2013, 341, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibricevic, A.; Pekosz, A.; Walter, M.J.; Newby, C.; Battaile, J.T.; Brown, E.G.; Holtzman, M.J.; Brody, S.L. Influenza virus receptor specificity and cell tropism in mouse and human airway epithelial cells. J Virol 2006, 80, 7469–7480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, J.M.; Bourne, A.J.; Chen, H.; Guan, Y.; Peiris, J.S. Sialic acid receptor detection in the human respiratory tract: evidence for widespread distribution of potential binding sites for human and avian influenza viruses. Respir Res 2007, 8, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, Z.Y.; Luo, M.Y.; Qi, W.B.; Yu, B.; Jiao, P.R.; Liao, M. Detection of expression of influenza virus receptors in tissues of BALB/c mice by histochemistry. Vet Res Commun 2009, 33, 895–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shortridge, K.F.; Zhou, N.N.; Guan, Y.; Gao, P.; Ito, T.; Kawaoka, Y.; Kodihalli, S.; Krauss, S.; Markwell, D.; Murti, K.G.; et al. Characterization of avian H5N1 influenza viruses from poultry in Hong Kong. Virology 1998, 252, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achenbach, J.E.; Bowen, R.A. Transmission of avian influenza A viruses among species in an artificial barnyard. PLoS One 2011, 6, e17643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiono, T.; Okamatsu, M.; Yamamoto, N.; Ogasawara, K.; Endo, M.; Kuribayashi, S.; Shichinohe, S.; Motohashi, Y.; Chu, D.H.; Suzuki, M.; et al. Experimental infection of highly and low pathogenic avian influenza viruses to chickens, ducks, tree sparrows, jungle crows, and black rats for the evaluation of their roles in virus transmission. Vet Microbiol 2016, 182, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VanDalen, K.K.; Nemeth, N.M.; Thomas, N.O.; Barrett, N.L.; Ellis, J.W.; Sullivan, H.J.; Franklin, A.B.; Shriner, S.A. Experimental infections of Norway rats with avian-derived low-pathogenic influenza A viruses. Arch Virol 2019, 164, 1831–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, J.; Wang, S.; Yin, Y.; Zhang, G.; Carter, R.A.; Wang, J.; Xu, G.; Sun, H.; Wang, M.; Wen, C.; et al. Evolution of the H9N2 influenza genotype that facilitated the genesis of the novel H7N9 virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112, 548–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, T.T.; Wang, J.; Shen, Y.; Zhou, B.; Duan, L.; Cheung, C.L.; Ma, C.; Lycett, S.J.; Leung, C.Y.; Chen, X.; et al. The genesis and source of the H7N9 influenza viruses causing human infections in China. Nature 2013, 502, 241–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, T.T.; Zhou, B.; Wang, J.; Chai, Y.; Shen, Y.; Chen, X.; Ma, C.; Hong, W.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Dissemination, divergence and establishment of H7N9 influenza viruses in China. Nature 2015, 522, 102–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Lam, T.T.; Chai, Y.; Wang, J.; Fan, X.; Hong, W.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Liu, Y.; Smith, D.K.; et al. Emergence and evolution of H10 subtype influenza viruses in poultry in China. J Virol 2015, 89, 3534–3541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; Ma, W.; Sun, N.; Huang, L.; Li, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Wen, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, H.; Li, Q.; et al. PB2-588 V promotes the mammalian adaptation of H10N8, H7N9 and H9N2 avian influenza viruses. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 19474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Y.; Chen, Q.; Wang, Q.; Chen, J.; Jin, T.; Wong, G.; Quan, C.; Liu, J.; Wu, J.; Yin, R.; et al. Genesis, Evolution and Prevalence of H5N6 Avian Influenza Viruses in China. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 20, 810–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, R.; Sun, H.; Gao, F.; Luo, K.; Huang, Z.; Tong, Q.; Song, H.; Han, Q.; Liu, J.; Lan, Y.; et al. Human infection of avian influenza A H3N8 virus and the viral origins: a descriptive study. Lancet Microbe 2022, 3, e824–e834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, U.S.; Department of Agriculture. Detections of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza in Mammals. Available online: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/livestock-poultry-disease/avian/avian-influenza/hpai-detections/mammals (accessed on 27 February, 2025).

- Kuiken, T.; Rimmelzwaan, G.; van Riel, D.; van Amerongen, G.; Baars, M.; Fouchier, R.; Osterhaus, A. Avian H5N1 influenza in cats. Science 2004, 306, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Songserm, T.; Amonsin, A.; Jam-on, R.; Sae-Heng, N.; Meemak, N.; Pariyothorn, N.; Payungporn, S.; Theamboonlers, A.; Poovorawan, Y. Avian influenza H5N1 in naturally infected domestic cat. Emerg Infect Dis 2006, 12, 681–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, L.; Xu, L.; Zhu, H.; Deng, W.; Chen, T.; Lv, Q.; Li, F.; Yuan, J.; Xu, Y.; Huang, L.; et al. Transmission of H7N9 influenza virus in mice by different infective routes. Virol J 2014, 11, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.C.; Sonnberg, S.; Webby, R.J.; Webster, R.G. Influenza A(H7N9) virus transmission between finches and poultry. Emerg Infect Dis 2015, 21, 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Chen, R.; Yan, Z. , Cai, Q.; Guan, Y., Zhu, H. Experimental infection of rats with influenza A viruses: Implications for murine rodents in in-fluenza A virus ecology. In Abstract Book, 3rd Annual CEIRR Network Meeting, New York Academy of Medicine, 1216 5th Ave, New York, NY 10029, July 21-24, 2024. [Google Scholar]

| Strain Name | Abbreviation | Subtype | Clade1 |

| A/California/07/2009 | CA7 | H1N1 | H1N1/2009 prototype |

| A/Vietnam/1203/2004 | VN1203 | H5N1 | HAPI H5 clade 1.0 |

| A/Duck/Guiyang/5096/2013 | GY5096 | H5N1 | HPAI H5 clade 2.3.4.4g |

| A/Chicken/Shenzhen/2400/2013 | SZ2400 | H5N6 | HPAI H5 clade 2.3.4.4a |

| A/Shenzhen/SP378/2015 | SP378 | H5N6 | HPAI H5 clade 2.3.4.4e |

| A/Duck/Huzhou/4258/2013 | HZ4258 | H5N8 | HPAI H5 clade 2.3.4.4b |

| A/Anhui/1/2013 | AH1 | H7N9 | H7N9 prototype |

| A/Shanghai/2/2013 | SH2 | H7N9 | H7N9 prototype |

| A/Guangdong/SP440/2017 | SP440 | H7N9 | HPAI H7N9 |

| A/Chicken/Wenzhou/598/2013 | WZ598 | H9N2 | H9N2 Y280 lineage |

| A/Jiangxi-Donghu/346/2013 | JX346 | H10N8 | H10N8 prototype |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).