Submitted:

03 March 2025

Posted:

06 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- The collective contribution of SDN, NFV, and C-RAN to reducing energy consumption in cellular networks.

- Existing challenges and limitations in the convergence of these technologies for energy-efficient communication networks.

- A cellular architecture is proposed based on SDN, NFV, and C-RAN to make the cellular network power efficient.

2. Related Work and Motivation

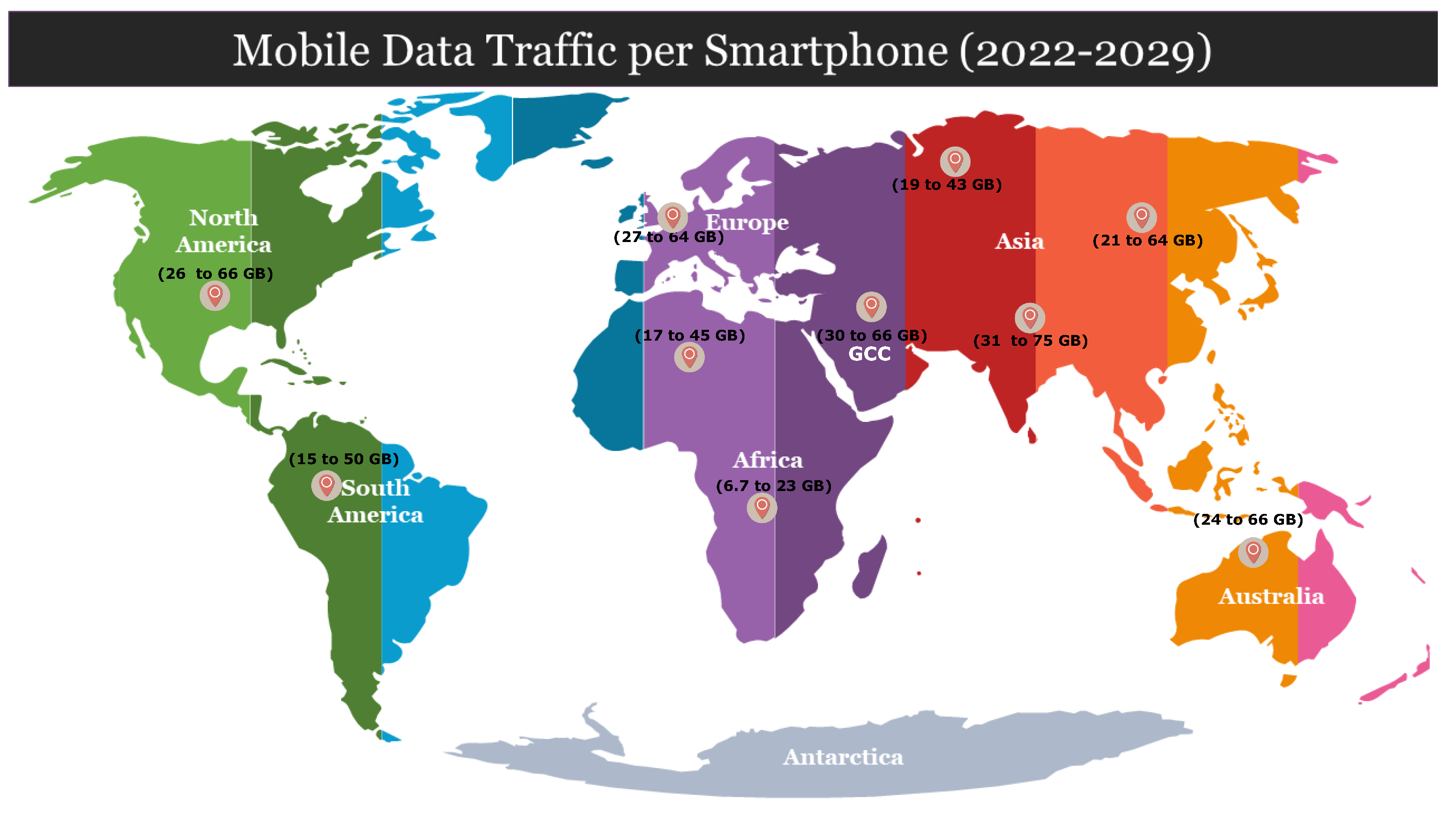

2.1. Motivation

3. What is SDN?

3.1. Working Principle

| Literature (Ref.) |

Hardware Solutions/ Smart Grid |

Renewable Energy Source/ Energy Harvesting |

mMIMO | mmWave | HetNet | Cell Zooming | Beamforming | D2D Communication |

AI/ML | Sleep Modes Basestation |

C-RAN | SDN | NFV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chia et al. [18] | X | ||||||||||||

| Tahsin et al. [20] | X | ||||||||||||

| Alsharif et al. [21] | X | X | |||||||||||

| A. Jahid et al. [22] | X | X | |||||||||||

| A. Jahid et al. [23] | X | ||||||||||||

| M. S. Hossain et al. [24] | X | ||||||||||||

| J. An et al. [25] | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Z. Hasan et al. [26] | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Malathy et al. [27] | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Ishfaq Bashir Sofi et al. [28] | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Fatima Salahdine et al. [29] | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| S. Jamil et al. [30] | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| S. Buzzi et al. [31] | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| B. Mao et al. [32] | X | ||||||||||||

| F. O. Ehiagwinal et al. [34] | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Q. Wu et al. [35] | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| M. Feng et al. [36] | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Y. Alsaba et al. [37] | X | X | |||||||||||

| Alsharif et al. [38] | X | ||||||||||||

| Nicola Piovesan et al. [40] | X | X | |||||||||||

| L. M. P. Larsen et al. [42] | X | ||||||||||||

| K. N. R. S. V. Prasad et al. [44] | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| S. R. Danve et al. [49] | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| A. Jahid et al. [50] | X | X | |||||||||||

| Shunging Zhang et al. [46] | X | X | |||||||||||

| Sofana Reka et al. [33] | X | ||||||||||||

| S. Guo et al. [41] | X | ||||||||||||

| A. Bohli et al. [47] | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| M. M. Mowla et al. [48] | X | X | |||||||||||

| Alimi et al. [51] | X | X | |||||||||||

| U. K. Dutta et al. [39] | X | ||||||||||||

| Miao Yao et al. [45] | X | ||||||||||||

| L. M. P. Larsen et al. [43] | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Bojkovic et al. [6] | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Dawadi et al. [52] | X | ||||||||||||

| Alsharif et al. [53] | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Usama M et al. [54] | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Zhang et al. [55] | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| Dlamini T. et al. [56] | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| D. A. Temesgene et al. [57] | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| E. J. Kitindi et al. [58] | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Chih-Lin I. et al. [59] | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| This Paper | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

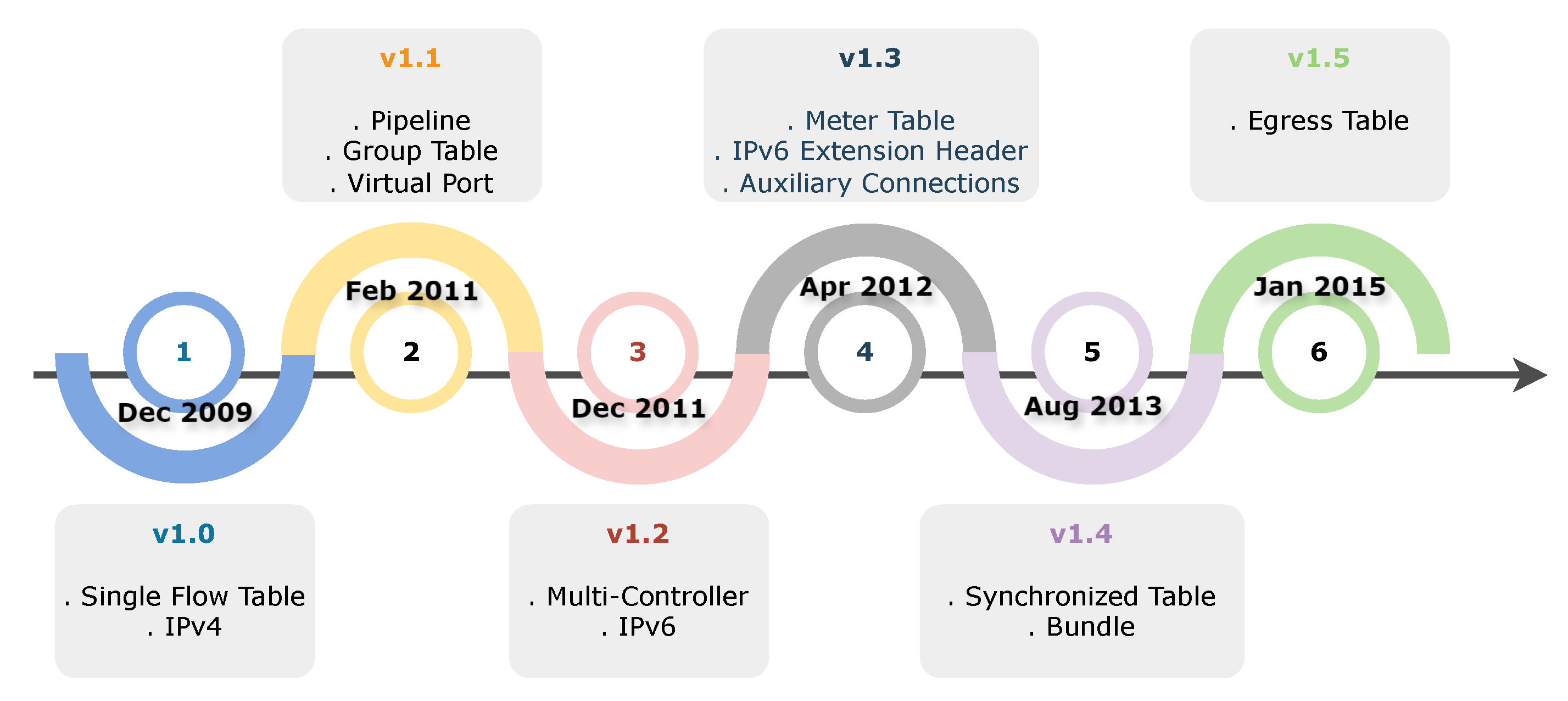

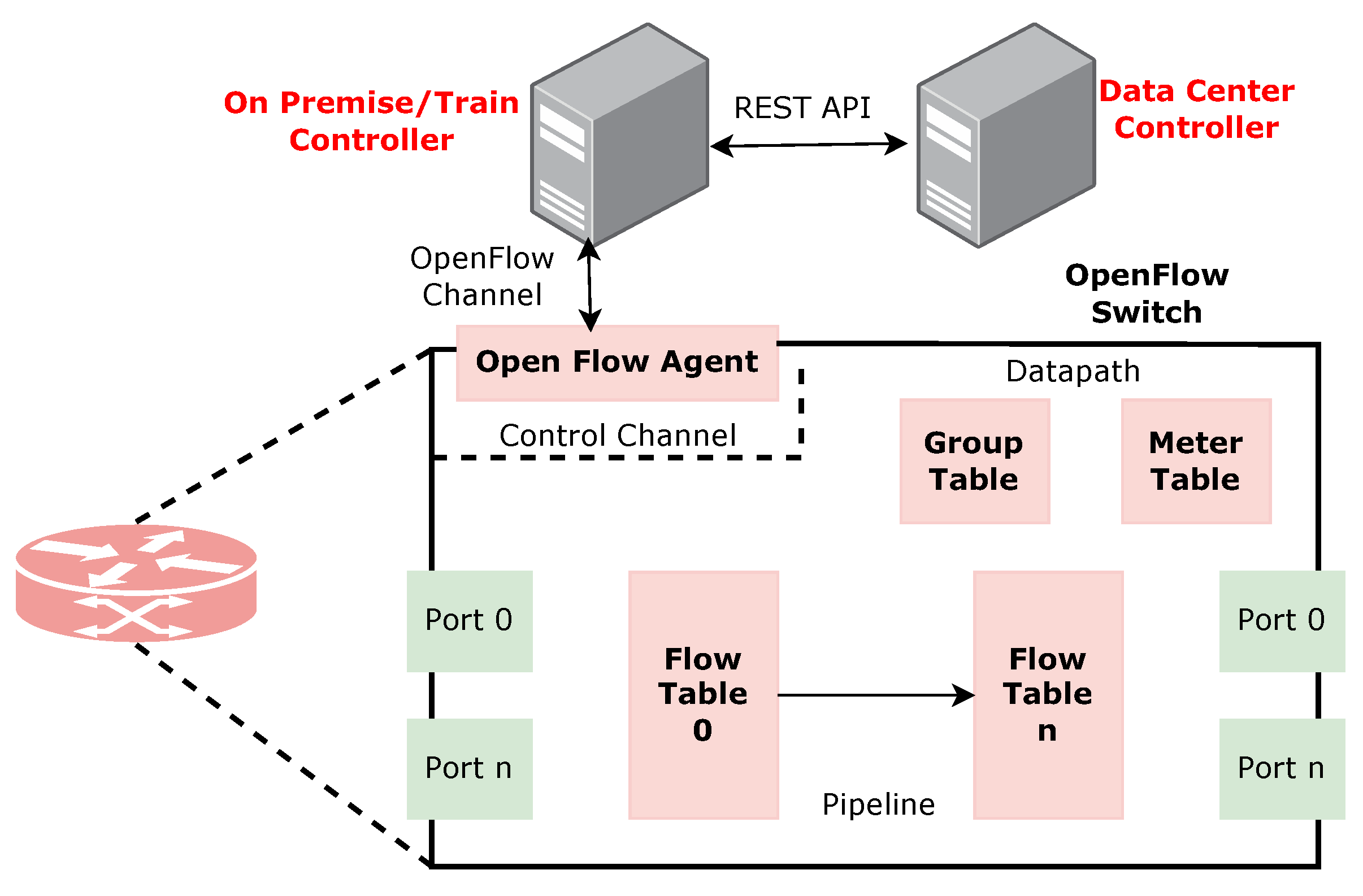

3.1.1. OpenFlow

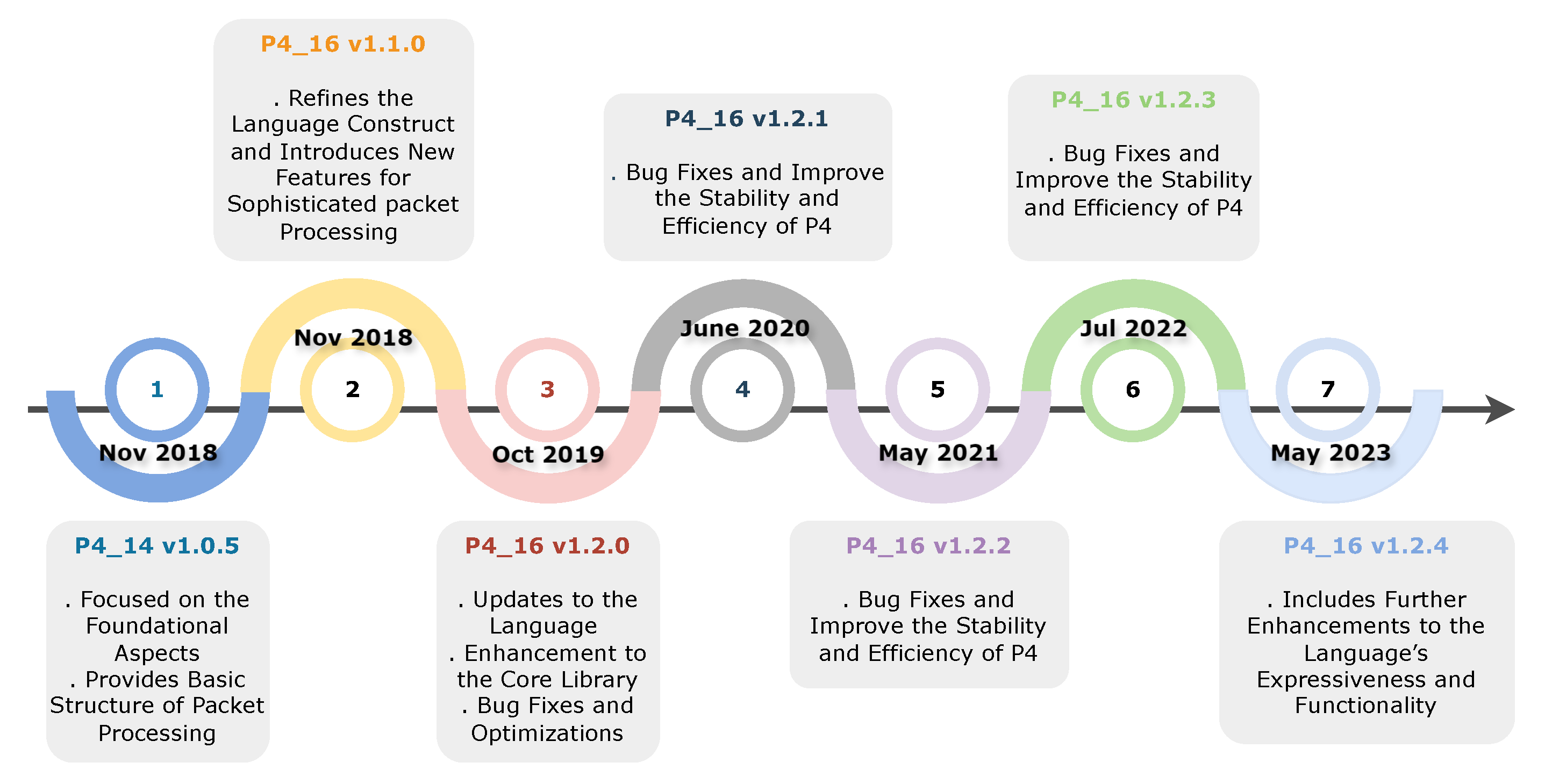

3.1.2. P4 Language

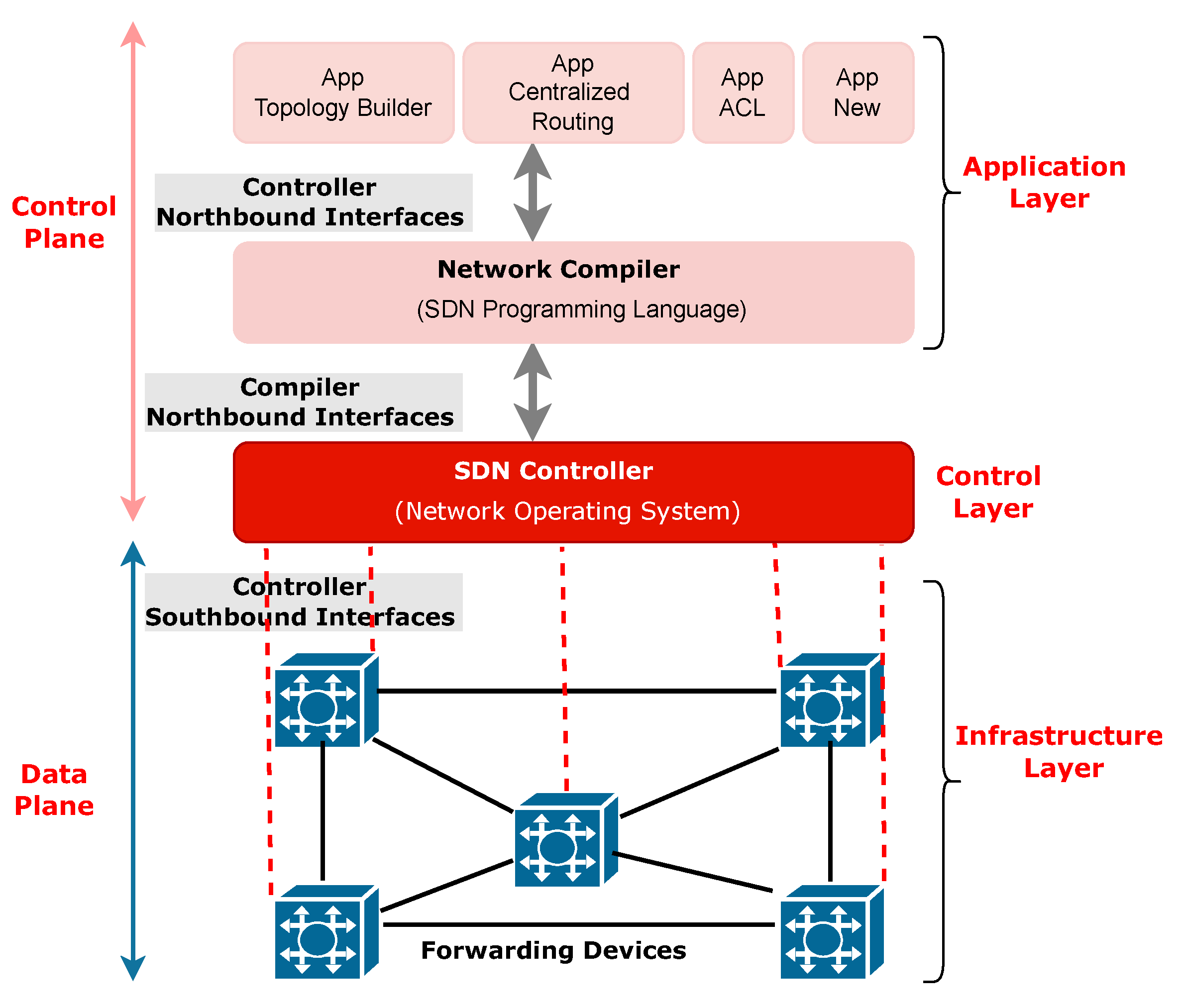

3.2. Architecture of SDN

- Application Layer: This top layer contains all the applications that need to communicate with the network. These applications can include network topology builders, logging and monitoring tools, network Access Control Lists (ACLs), and other network services [64,74]. The applications are agnostic to the Southbound protocols, whether they use OpenFlow or P4Runtime.

- Control Layer: This central layer houses the SDN controller, which manages the flow of data traffic in the network devices based on the requirements of the application layer. The SDN controller uses Northbound APIs to communicate with the application layer and Southbound APIs to interact with the infrastructure layer [64,74].

- Applications and Services: These programs and systems use the network to communicate and interact with the SDN controller via the Northbound Interface to request network services.

- Northbound Interface: This communication link between the SDN controller and the applications allows applications to request network services and receive network information.

- Network Operating System (NOS): The software running on the SDN controller provides the necessary functionality for managing the network.

- SDN Controller: The heart of the SDN architecture, the SDN controller acts as the network’s "brain," making packet routing decisions. It interacts with network devices through the Southbound Interface and communicates with applications via the Northbound Interface. Examples of controllers include ONOS, OpenDaylight, Floodlight, IRIS, POX, and Ryu [75].

- Southbound Interface: This communication link between the SDN controller and network devices transmits instructions from the controller to the devices and provides the controller with network state information.

- Network Devices: The physical infrastructure, including switches, routers, and other networking hardware, receives instructions from the SDN controller and forwards or drops data packets accordingly.

3.3. How SDN will Help Cellular Network 5G and Beyond?

3.4. Challenges and Solutions

4. What is NFV?

4.1. Working Principle of NFV

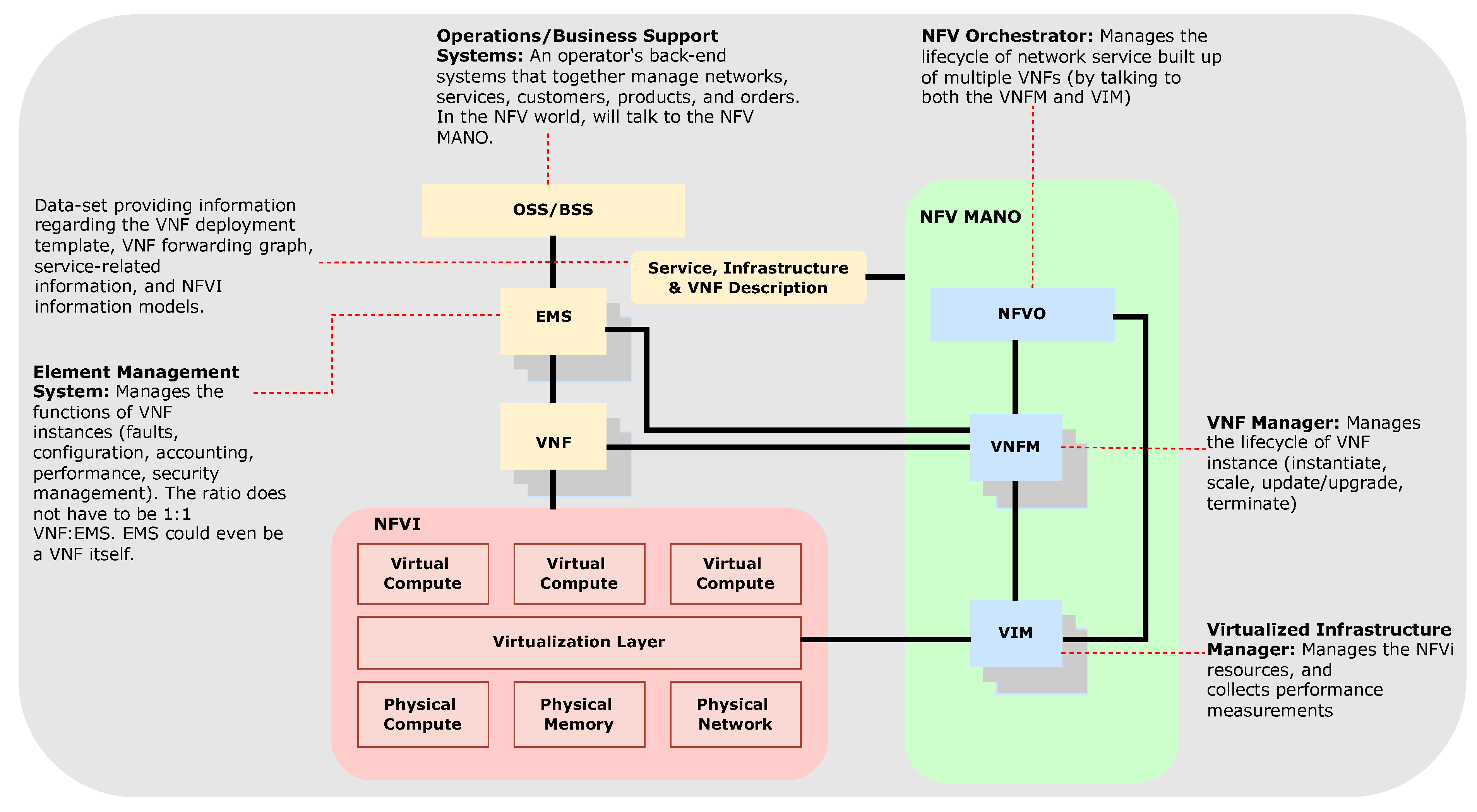

4.2. Architecture of NFV

- 1.

- Virtualized Network Functions (VNFs): VNFs are the virtual instances of network functions implemented as software-based functions that were traditionally implemented using dedicated hardware. The network functions such as routing, firewall, and network optimization can be implemented using software and deployed and managed on the data centers or in the cloud.

- 2.

-

NFV Infrastructure (NFVI): NFVI is responsible for providing the underlying physical and virtual infrastructure for hosting the VNFs. It includes the following elements:

- (a)

- Compute Resources: NFVI provides general-purpose servers or cloud-based compute instances where VNFs run.

- (b)

- Network and Storage Resources: NFVI uses virtualized network components like connectivity, switches, routers, VLANs, and storage (including cloud storage) to handle data and configurations. These resources form the backbone for managing information within NFVI.

- (c)

- Virtualization Layer: The virtualization layer is responsible for providing virtualization technologies, such as hypervisors and containerization, to run VNFs on available physical hardware.

- 3.

- Element Management System (EMS): It manages the physical network equipment including legacy hardware which is used for the deployment of NFV. It ensures coordination between virtualized and traditional network elements.

- 4.

- Operations Support System (OSS) and Business Support System (BSS): These systems provide end-to-end network service management, billing, and provisioning.

- 5.

-

MANO: Management and orchestration in network function virtualization, is divided into three key functional blocks:

- (a)

- NFV Orchestrator (NFVO): The NFVO is responsible for VNF lifecycle management, handling deployment, and scaling coordination. It integrates with NFVI to provide the required resources and communicate with the VNF Manager (VNFM) for VNF-specific tasks.

- (b)

- VNF Manager (VNFM): VNFM manages the lifecycle of VNFs which includes instantiation, configuration, and termination (on/off) of VNFs. VNF Manager communicates with NFVO and VNF itself to manage the functionality of VNFs.

- (c)

- Virtualized Infrastructure Manager (VIM): VIM manages virtual resources which are required for VNFs. It identifies, allocates, and handles faults in physical and virtual resources.

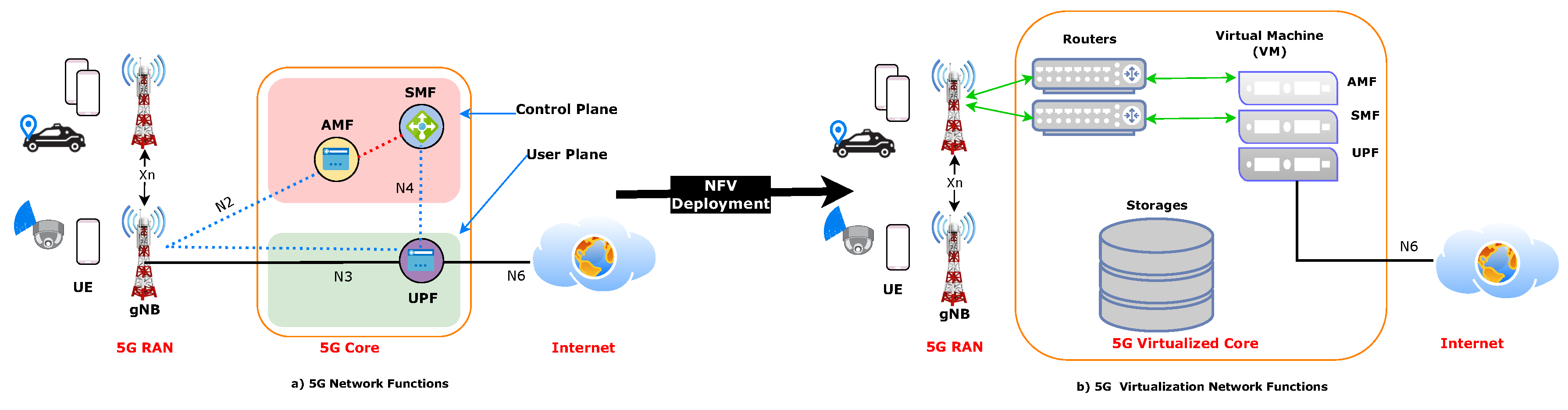

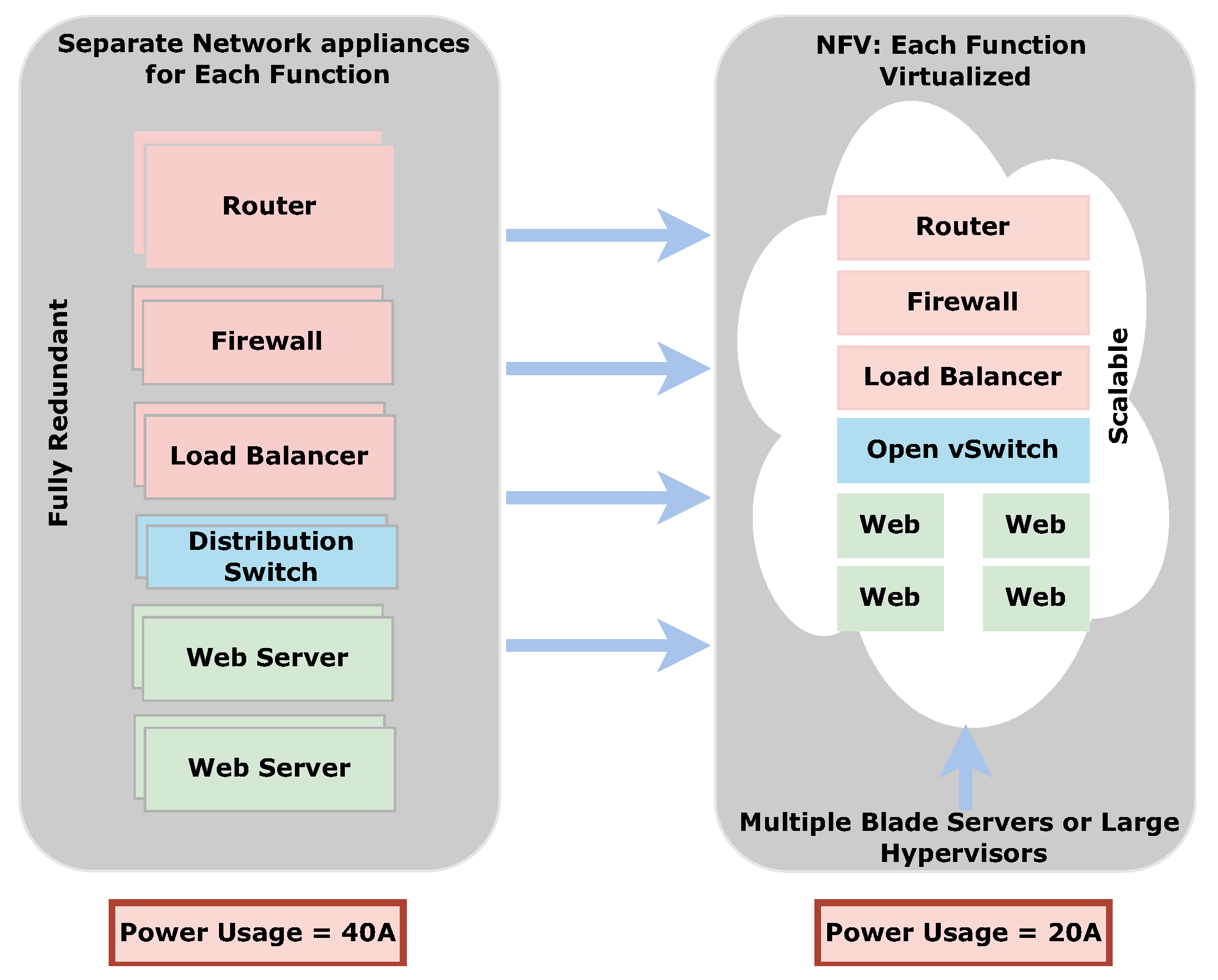

4.3. How NFV will Help Cellular Network?

4.4. Challenges and Solutions

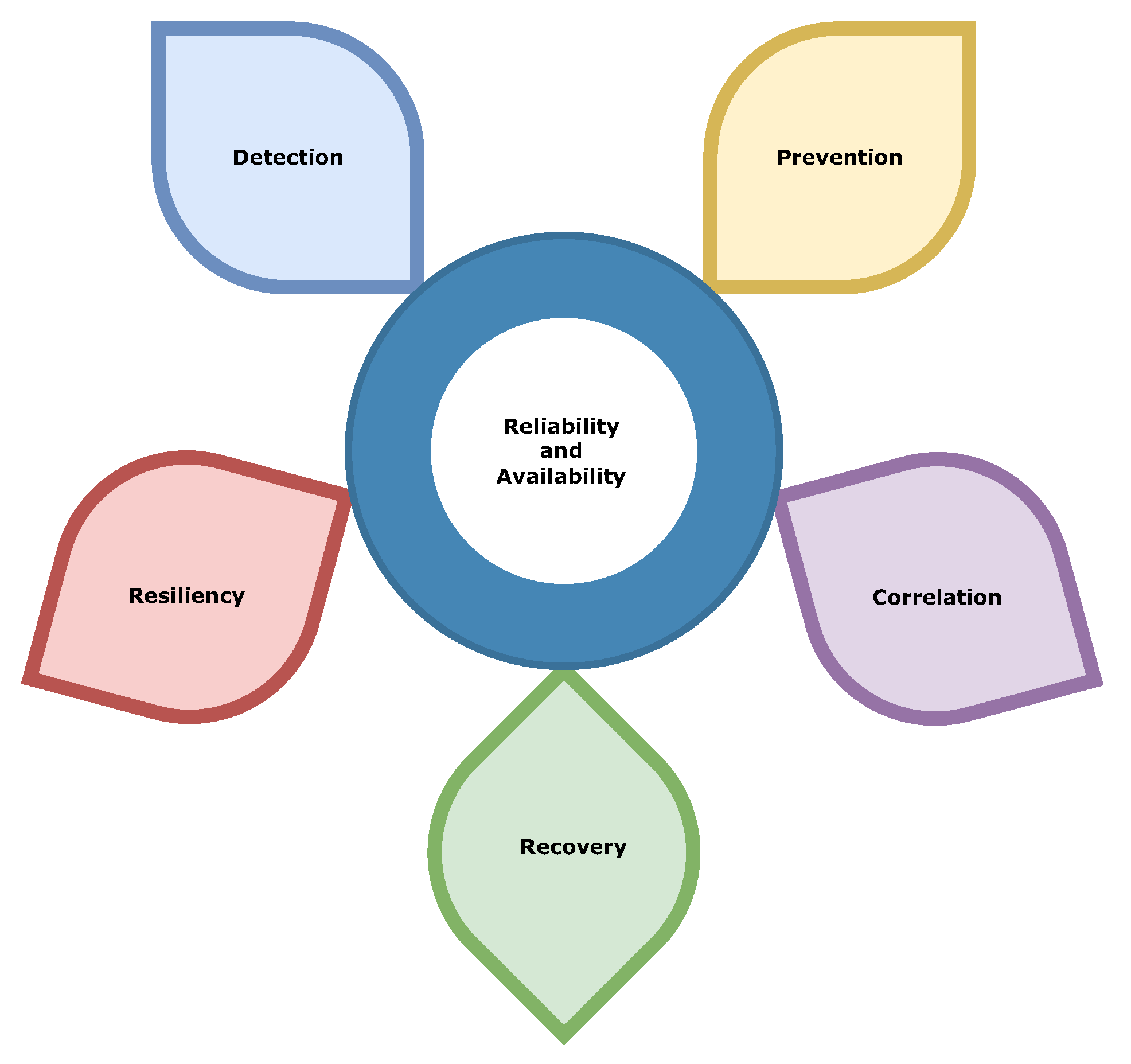

4.4.1. Core: Challenges and Solutions

4.4.2. RAN: Challenges and Solutions

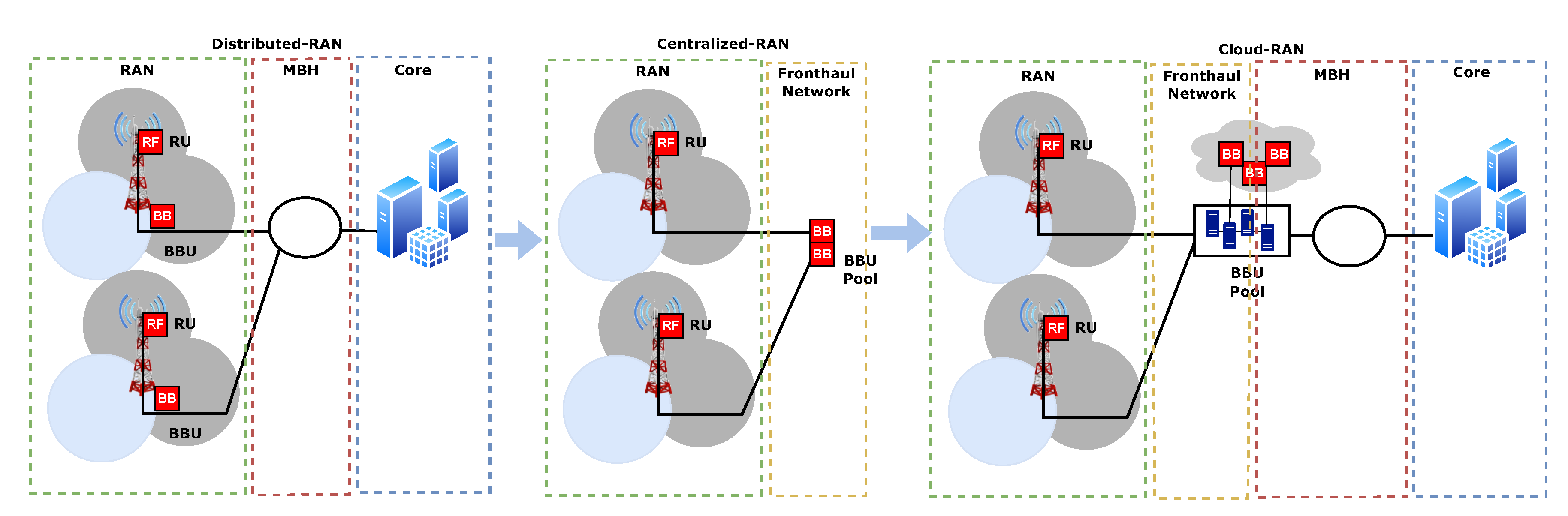

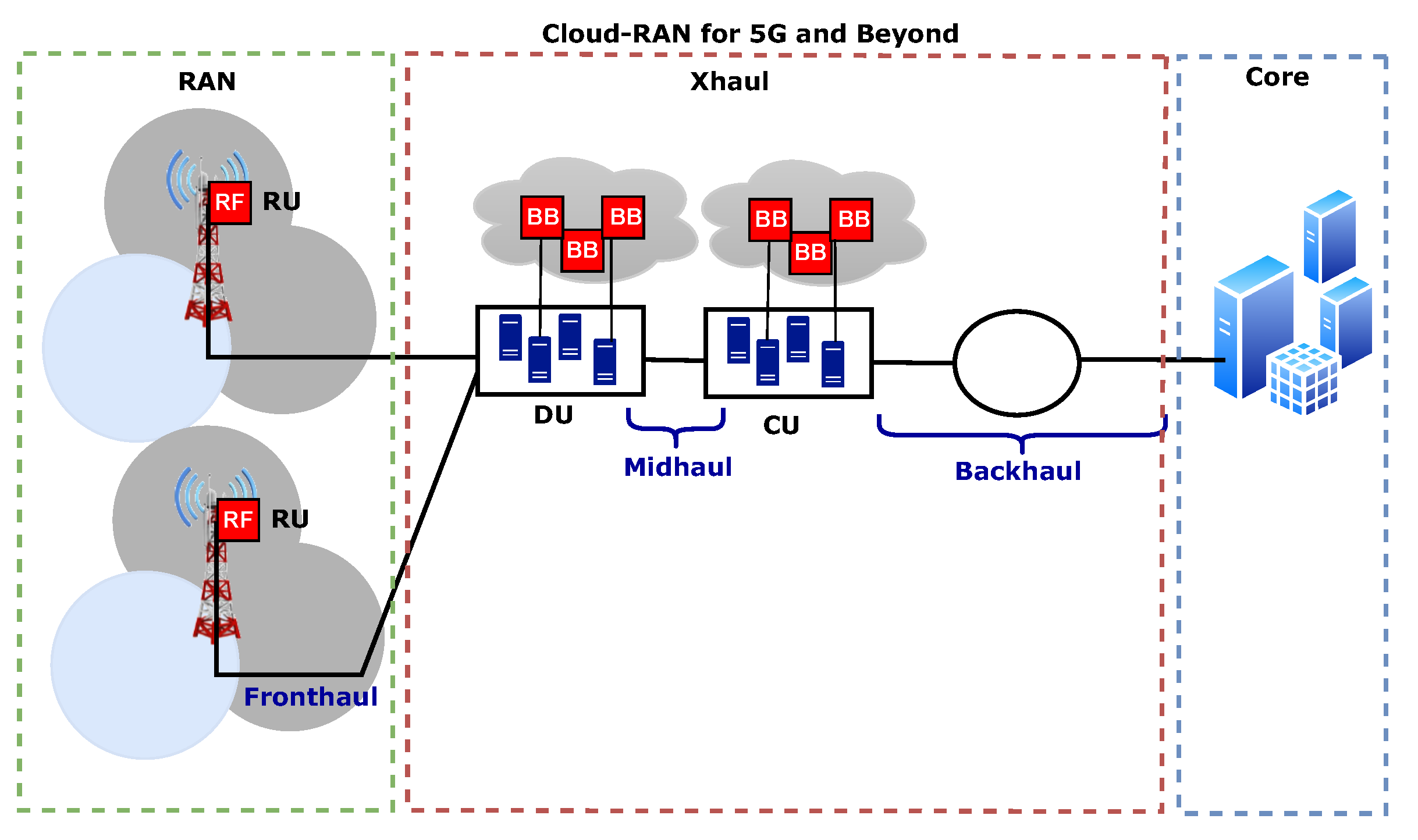

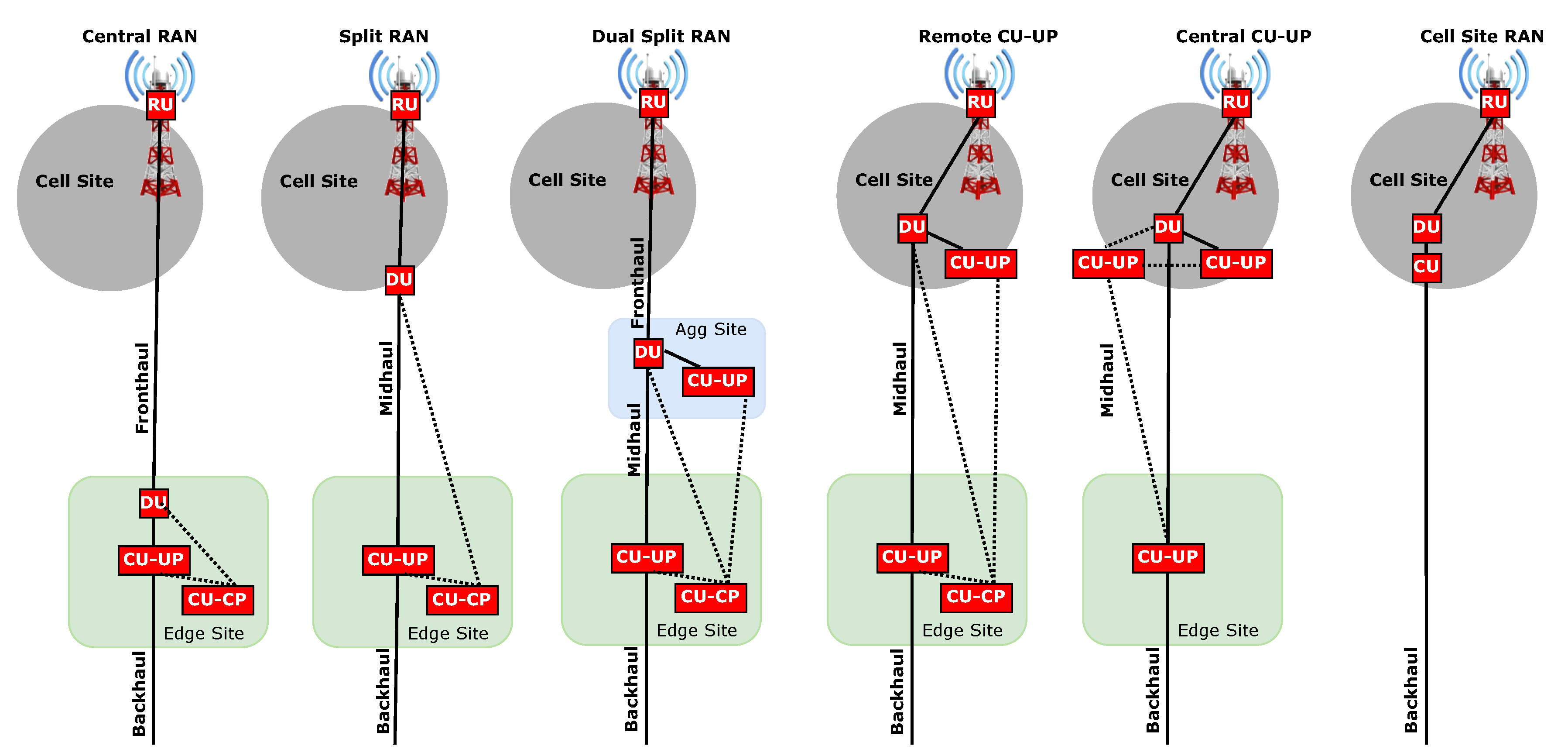

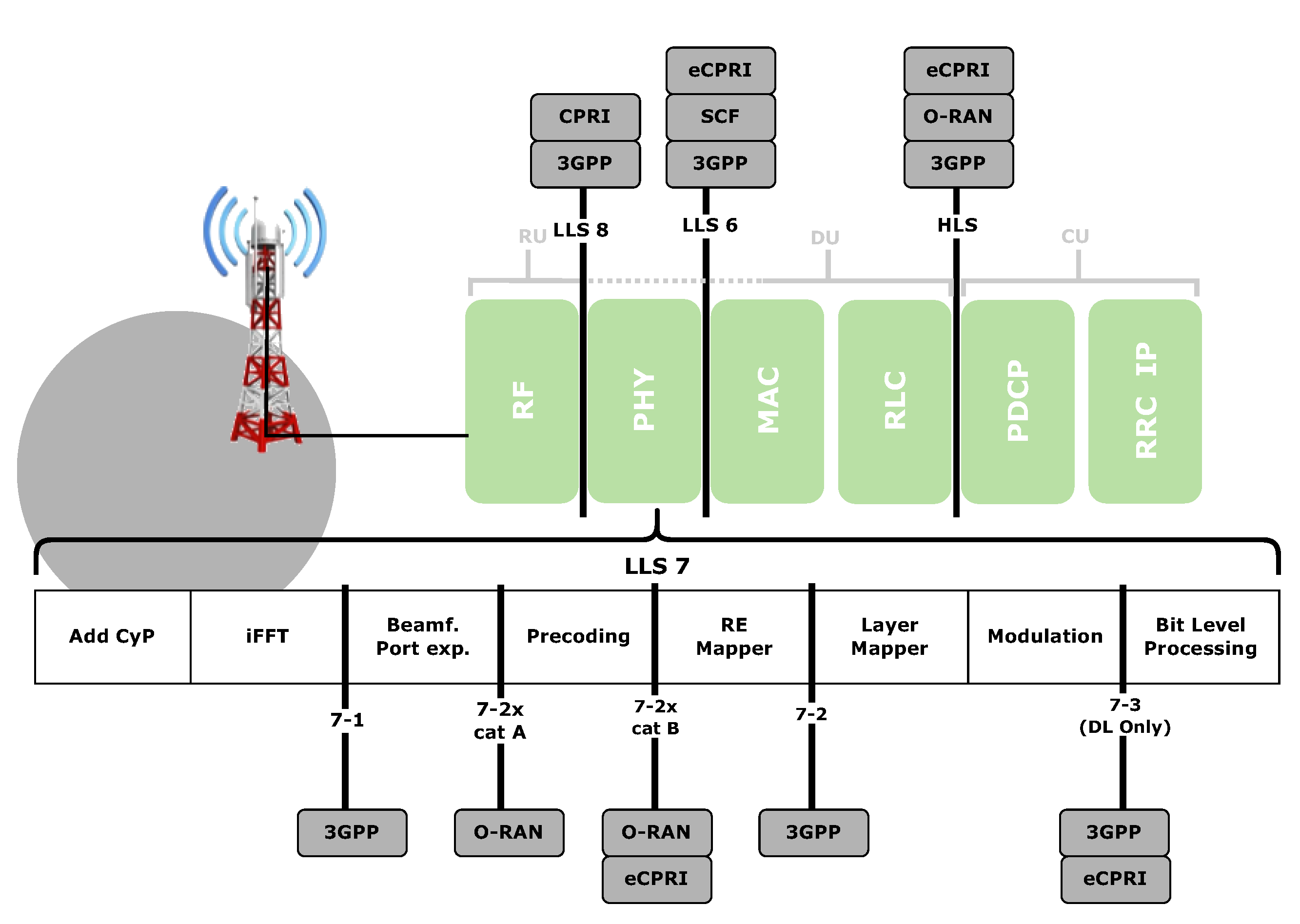

5. What is C-RAN?

5.1. Working Principle of C-RAN

5.2. Architecture of C-RAN

5.3. How can C-RAN improve the sustainability of Cellular Networks

5.4. Challenges and Solutions

6. Pitfalls and Potentials

- Interoperability and Standardization: Different vendors may implement the supporting hardware and software related to SDN, NFV, and C-RAN technologies using their proprietary protocols and interfaces, resulting in interoperability issues. To avoid the interoperability issue there should be a strong collaboration between the different stakeholders. The telecom industry should promote organizations like ONF [121] and ETSI [122] that support the standardization of these tools and technologies [123].

- Scalability: As telecom networks expand in size to support the increasing demand for connectivity raises the complexity of the network and leads to scalability issues related to SDN, NFV, and C-RAN. Dynamic scaling mechanisms can be implemented to solve the scalability issues. Technologies like orchestration can also be employed to handle the scalability issue [124].

- Network Performance and Latency: Introducing the virtualization and centralization control of network functions may increase the latency and affect real-time applications for instance voice and video streaming. To mitigate latency issues SDN and NFV-based edge computing capabilities can be deployed near the end-users. The use of efficient routing algorithms and optimization of network architecture can also minimize latency [125].

- Management and Orchestration: It can be challenging to manage and orchestrate virtualized network functions across distributed environments. Utilizing comprehensive management and orchestration platforms that can provide centralized control and automation capabilities to ease network operations. These platforms also support multi-vendor environments [126].

- Resource Utilization and Optimization: Amplifying resource utilization in virtualized environments, whether it is computing, storage, or networking is crucial for achieving cost-effectiveness. Utilizing intelligent resource allocation algorithms and analytics-driven optimization techniques can help optimize resource utilization. Furthermore, network-slicing technologies can facilitate efficient resource allocation for specific applications [127].

- Regulatory and Compliance Issues: Ensuring compliance with regulatory requirements and standards during the implementation of SDN, NFV, and C-RAN solutions introduces some challenges due to the dynamic nature of virtualized networks. It is crucial to be updated with the new rules and regulations set by the regulatory bodies. Utilize features such as network segmentation and encryption to protect your data and avoid compliance issues[128].

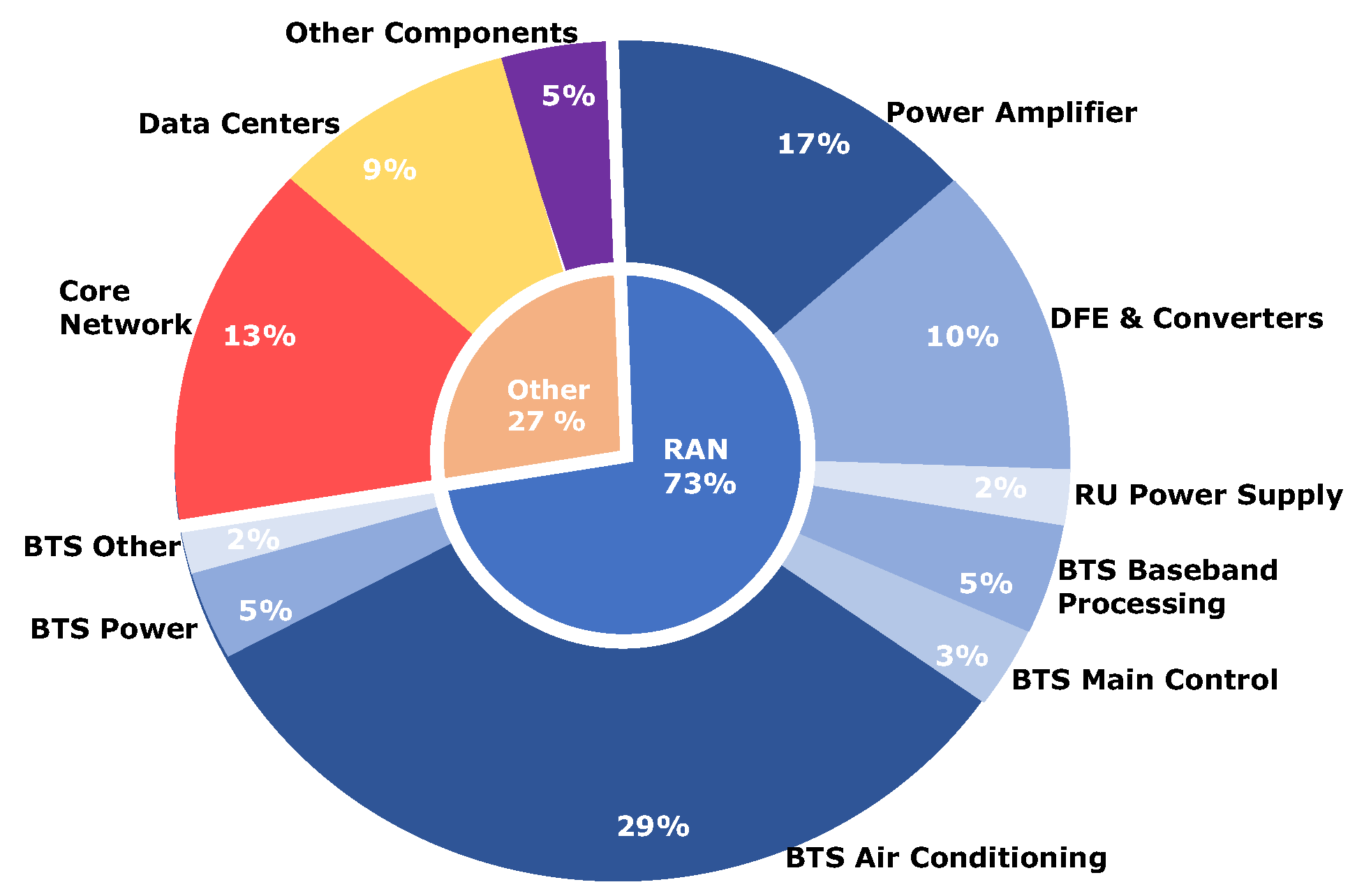

6.1. Reducing the Energy Consumption

6.2. Virtualization Feasibility of Network Functions

6.2.1. Core Functions Easy for Virtualization

6.2.2. Core Functions Complex for Virtualization

6.2.3. Virtualization of RAN Functions

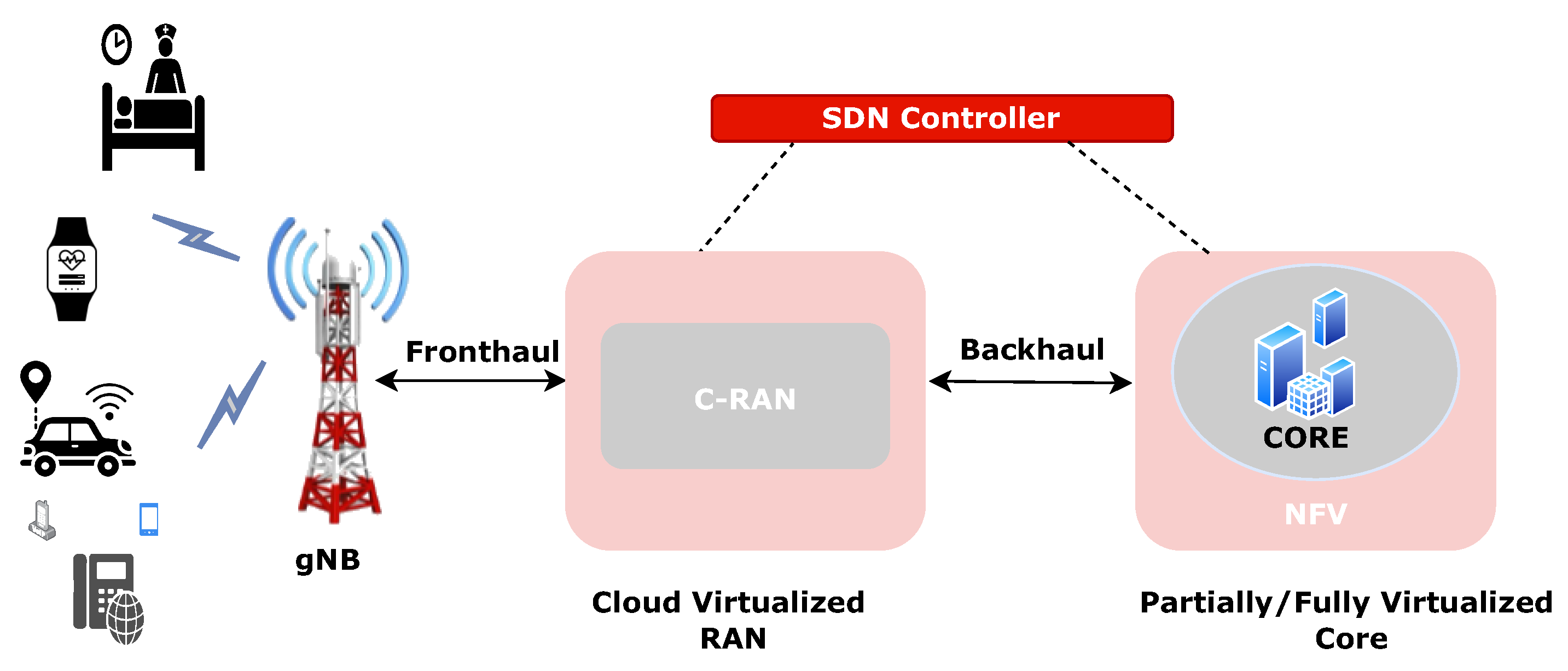

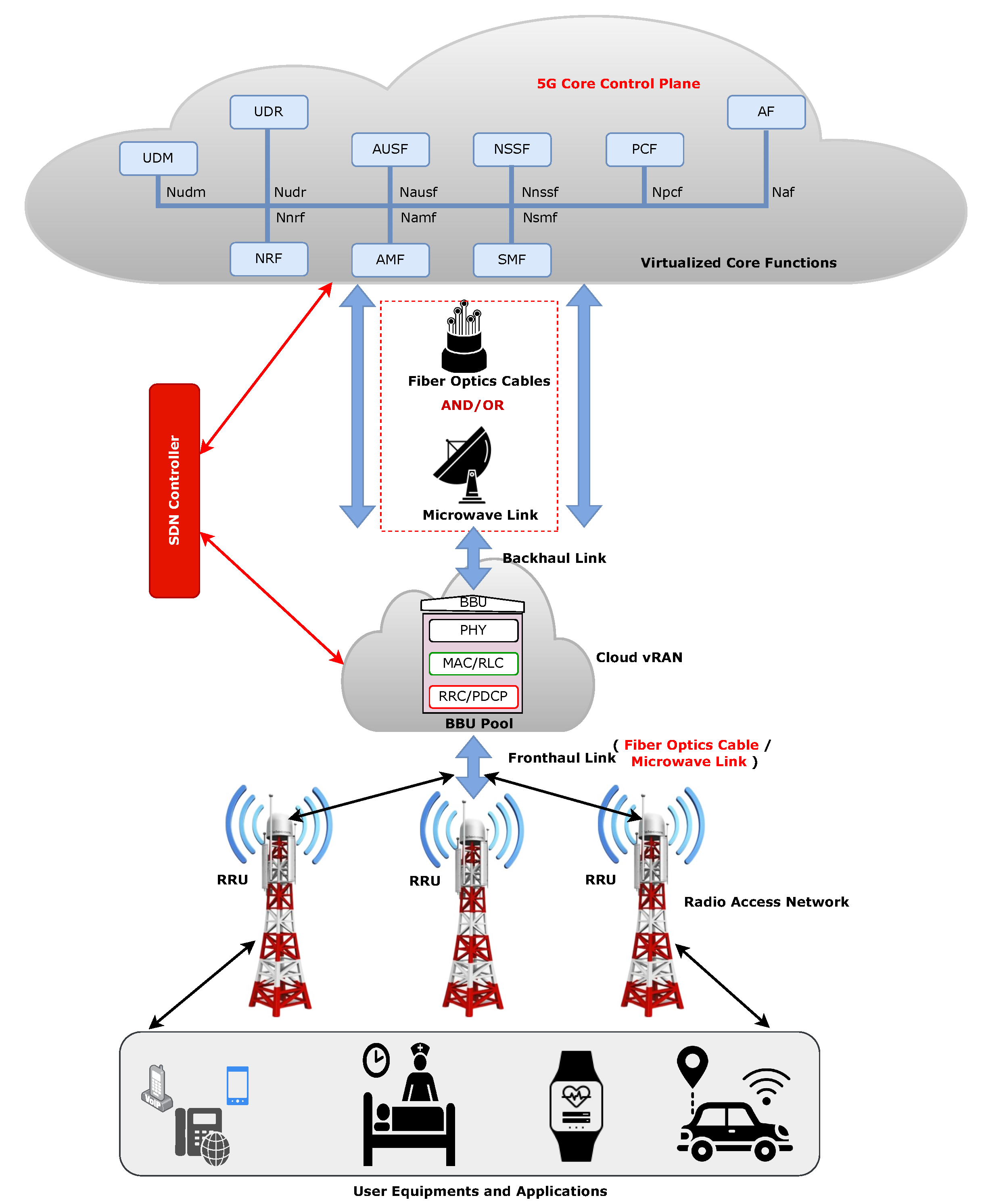

7. Proposed Architecture for Cellular System Based on SDN, NFV, and C-RAN

- 5G Core Control Plane With Virtualized Core Functions: The core of the 5G and beyond cellular network can be fully virtualized since flexibility is more important for operators to support different use cases. Virtualization of core will help to develop quicker solutions/applications and the developed solutions can be deployed and tested faster. It could also pave the way for more innovative and flexible network services, as network operators would have more freedom to customize and optimize their networks based on a single, unified platform [97].

- SDN Controller: The SDN controller oversees the entire network element and manages the resource allocation based on the demands. This is a central point that manages the data flow in the network through SDN principles, making the network programmable and more adaptable to varying traffic patterns and demands [97].

- Backhaul and Fronthaul Link: Fiber optics cables and microwave links are two options for the backhaul connections that link the core network to the RAN architecture. Fiber optic cables are more energy-efficient under heavy load conditions, while microwave links are better under low load conditions [48]. Fronthaul connects the BBUs in the C-RAN architecture to RRUs on cell towers, typically using high-bandwidth, low-latency connections such as fiber cables.

-

Cloud vRAN: The elements of C-RAN could also be virtualized to curtail the use of energy. The C-RAN elements are given below:

- -

- BBU: Processes the baseband signal and is part of the C-RAN that can be centralized in a data center to serve multiple radio sites.

- -

- PHY (Physical Layer): The layer in the BBU that handles the physical connection to the network.

- -

- MAC/RLC: These layers manage multiple access protocols and data transfer reliability.

- -

- RRC/PDCP: These layers manage radio resources and the convergence of data from different sources.

- NFV in C-RAN: When NFV and C-RAN are combined, they offer more energy-efficient, flexible, and scalable cellular networks. In C-RAN, functions with stringent latency requirements such as Digital Signal Processing (DSP) are deployed on the dedicated hardware and co-located with RRHs. On the other hand, BBU’s functionalities such as packet scheduling and user management could be virtualized since these functions are not as latency-sensitive and could be decoupled from hardware and deployed as software instance [145].

- User Equipment and Applications: This represents the devices and applications that use the cellular network, such as smartphones, wearables, and vehicles.

7.1. Interaction Between SDN Controller, NFV MANO and C-RAN

-

C-RAN Management:

- -

- Centralization: The SDN controller can centralize the control of the C-RAN infrastructure, allowing for the pooling of BBUs that can be dynamically assigned to RRUs based on the current network load and demand.

- -

- Network Optimization: Through the SDN controller, the network can optimize the routing of traffic between the RRUs and BBUs. It can also manage the split of control and user plane functions to improve performance and efficiency.

- -

- Dynamic Configuration: The SDN controller enables the dynamic reconfiguration of network resources in response to changing traffic patterns. This will help C-RAN to allocate and reallocate radio resources in real-time.

-

NFV Management:

- -

- Oversees the Underlying Network Infrastructure: In the proposed architecture the SDN Controller doesn’t directly handle the core network functions. Instead, it oversees the underlying network infrastructure. This infrastructure allows various network functions such as signaling, session management, and authentication to communicate with each other and with the radio access network. The SDN Controller ensures that the data plane where actual data flows aligns smoothly with the control plane where decisions are made, resulting in an efficient and agile network [104].

- -

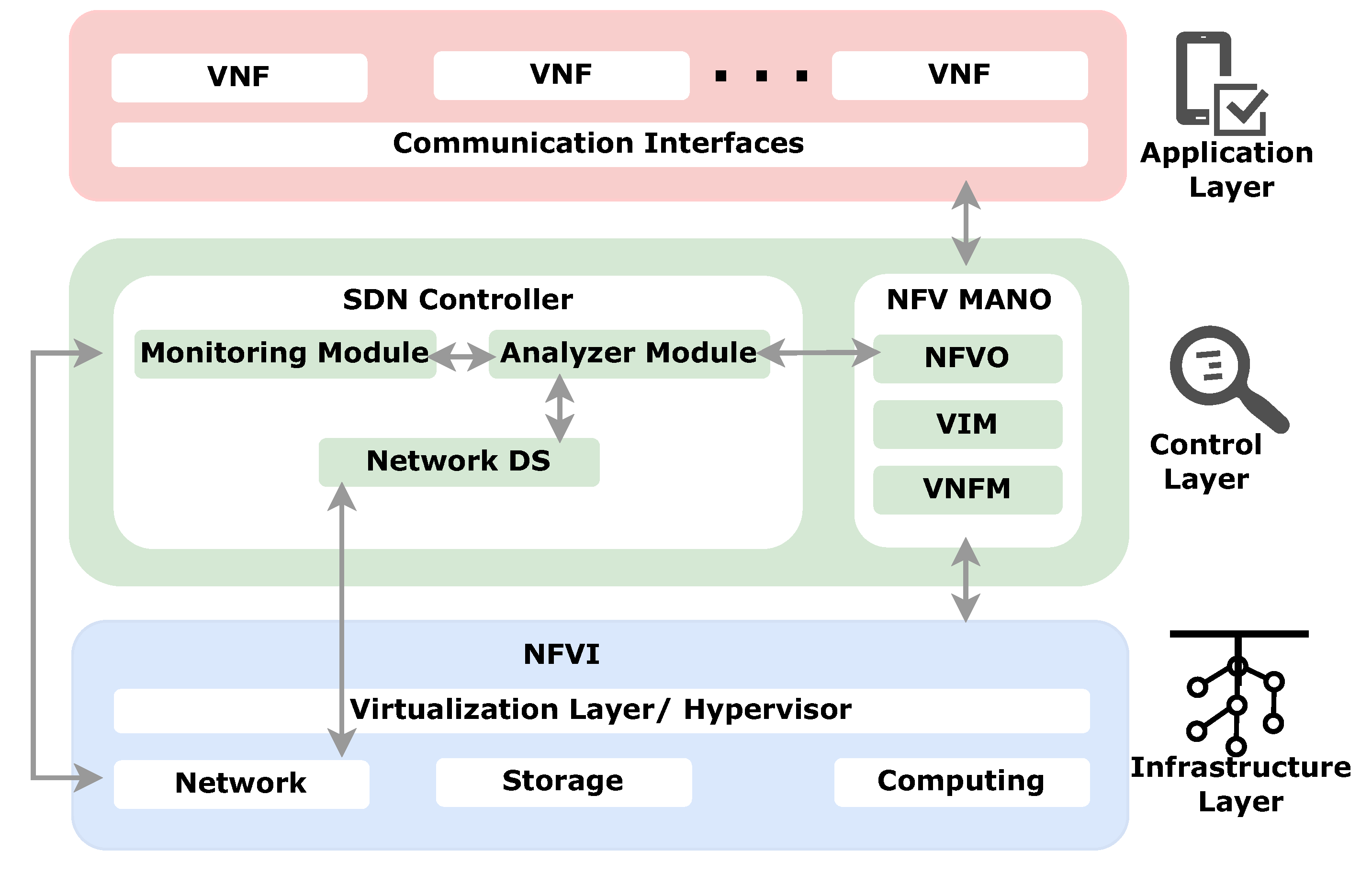

- Interconnectivity: Figure 18 shows the layered architecture of integration of SDN and NFV systems. It is similar to SDN architecture and consists of infrastructure, control, and application layers. It utilizes the principle of NFV to facilitate the implementation and management of network functions. The SDN controller orchestrates network resources to ensure proper communication among VNFs. Under the management of the VIM, the controller can modify network behavior as required, responding to network user requests [97]. The SDN Controller and NFV MANO work together to improve network services. SDN enhances NFV by providing better traffic steering and service chaining. MANO is responsible for managing and orchestrating the virtual network resources and connections between VNFs for a complete network service. This requires the SDN controller and MANO to collaborate for efficient traffic routing [104].

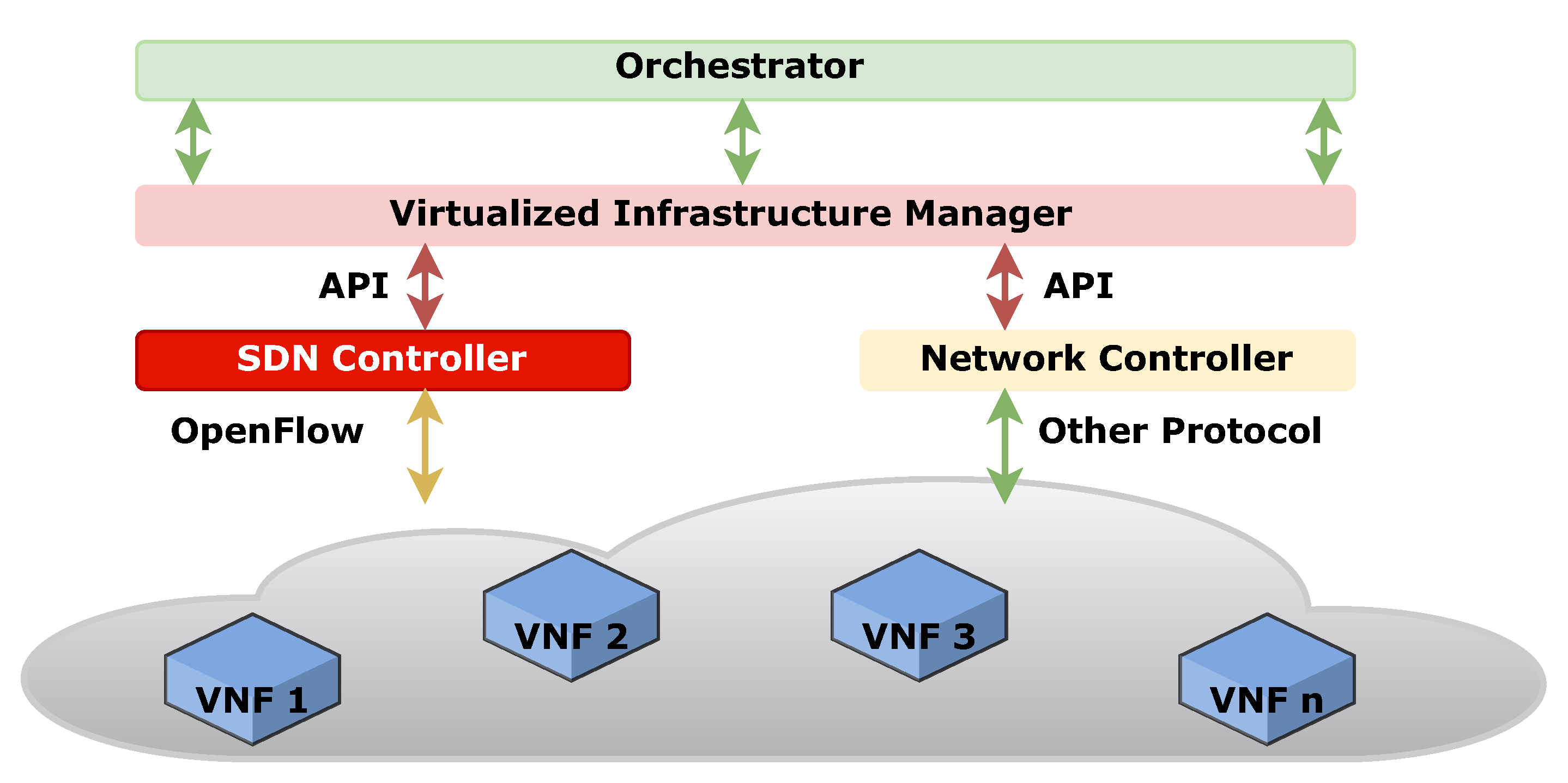

- -

- Deployment and Orchestration: The SDN controller, in collaboration with NFV orchestration tools, can deploy and manage the lifecycle of VNFs, such as scaling out or in, based on the network’s requirements. As depicted in Figure 19 the network orchestration function is utilized to establish network service chaining policies. These policies are also shared with the SDN controller within the NFVI networking layer through the NFV MANO framework. This collaboration provides efficient traffic routing and enhances overall network services [104].

- -

- Policy Enforcement: The SDN controller can enforce network policies at a granular level, directing specific types of traffic to pass through certain VNFs for processing, such as firewalls and load balancers.

-

Integration of SDN with C-RAN and VNF:

- -

- Flexibility and Scalability: By integrating SDN with C-RAN and VNFs, the network gains flexibility and scalability, allowing it to support a wide range of services and adapt to changes in traffic patterns or network conditions.

- -

- Resource Utilization: The SDN controller enhances resource utilization by matching computing and radio resources with network demands in real-time, which is critical for the efficiency of both C-RAN and VNFs.

7.2. Supporting Organization

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mobile data traffic outlook. Available online: https://www.ericsson.com/en/reports-and-papers/mobility-report/dataforecasts/mobile-traffic-forecast Accessed on: February 12, 2025.

- What’s the real story behind the explosive growth of data? Available online: https://www.red-gate.com/blog/database-development/whats-the-real-story-behind-the-explosive-growth-of-data Accessed on: February 10, 2025.

- What’s causing the exponential growth of data? Available online: https://www.red-gate.com/blog/database-development/whats-the-real-story-behind-the-explosive-growth-of-data Accessed on: February 04, 2025.

- This is how much data we’re using on our phones. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/08/how-the-pandemic-sparked-a-data-boom/ Accessed on: February 02, 2025.

- Ericsson and SDGs: Partnership for the future. Available online: https://www.ericsson.com/en/blog/2023/9/ericsson-sdgs-partnership-for-the-future Accessed on: February 15, 2025.

- Bojkovic, Z.S.; Milovanovic, D.A.; Fowdur, T.P., Eds. 5G Multimedia Communication: Technology, Multiservices, and Deployment, 1st ed.; CRC Press: 2020. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Ensure efficient energy consumption of 5G core. Available online: https://www.nokia.com/networks/core/5g-core/ Accessed on: February 13, 2025.

- Ahmed, Z.E.; Saeed, R.A.; Mukherjee, A. Challenges and Opportunities in Vehicular Cloud Computing. In Cloud Security: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications; Management Association, Information Resources, Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 2168-2185. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Dursch, A.; Yen, D.C.; Huang, S.M. Fourth generation wireless communications: an analysis of future potential and implementation. Comput. Stand. Interfaces 2005, 13–25.

- Bai, F.; Elbatt, T.; Hollan, G.; Krishnan, H.; Sadekar, V. Towards characterizing and classifying communication-based automotive applications from a wireless networking perspective. In Proceedings of the IEEE Workshop on Automotive Networking and Applications (AutoNet), San Francisco, CA, USA, 27 November–1 December 2006; pp. 1–25.

- Chuanmin, C.; Feng, W. Evolution of the telecommunications industry, a natural monopoly attributed from the U.S. telecommunications industry. Financ. Econ. 2012, 10, 70–72.

- Dagnaw, G.A. The Intelligent Six Generation Networks for Green Communication Environment, 2020.

- Saeed, M.; Saeed, R.A.; Saeid, E. Identity Division Multiplexing Based Location Preserve in 5G. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference of Technology, Science and Administration (ICTSA), 2021. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. SDN and NFV in 5G. In Network Function Virtualization: Concepts and Applicability in 5G Networks; IEEE, 2018; pp. 109–146. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Fondo-Ferreiro, P.; Gil-Castiñeira, F. The Role of Software-Defined Networking in Cellular Networks. Proceedings 2019, 21, 23. Available online: . [CrossRef]

- Software-Defined Networking (SDN) Definition. Available online: https://opennetworking.org/sdn-definition/ Accessed on: February 19, 2025.

- Network Functions Virtualisation – Introductory White Paper. Available online: https://portal.etsi.org/nfv/nfv_white_paper.pdf Accessed on: February 14, 2025.

- Chia, Yeow-Khiang & Sun, Sumei & Zhang, Rui. (2013). Energy Cooperation in Cellular Networks with Renewable Powered Base Stations. Wireless Communications, IEEE Transactions on. 13. . [CrossRef]

- HOMER Microgrid and Hybrid Power Modeling Software, [Online] Available: https://www.ul.com/software/homer-microgrid-and-hybrid-power-modeling-software Accessed on: February 20, 2025.

- Tahsin, Anika & Roy, Palash & Razzaque, Md. Abdur & Rashid, Mamun & Siraj, Mohammad & Alqahtani, Salman & Hassan, Md & Hassan, Mohammad. (2023). Energy Cooperation Among Sustainable Base Stations in Multi-Operator Cellular Networks. IEEE Access. 11. 19405-19417. [CrossRef]

- Alsharif, M.H.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.H. Green and Sustainable Cellular Base Stations: An Overview and Future Research Directions. Energies 2017, 10, 587. [CrossRef]

- A. Jahid and S. Hossain, "Intelligent Energy Cooperation Framework for Green Cellular Base Stations," 2018 International Conference on Computer, Communication, Chemical, Material and Electronic Engineering (IC4ME2), Rajshahi, Bangladesh, 2018, pp. 1-6, . [CrossRef]

- A. Jahid, M. K. H. Monju, M. E. Hossain and M. F. Hossain, "Renewable Energy Assisted Cost Aware Sustainable Off-Grid Base Stations With Energy Cooperation," in IEEE Access, vol. 6, pp. 60900-60920, 2018, . [CrossRef]

- M. S. Hossain, A. Jahid, K. Z. Islam and M. F. Rahman, "Solar PV and Biomass Resources-Based Sustainable Energy Supply for Off-Grid Cellular Base Stations," in IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 53817-53840, 2020, . [CrossRef]

- J. An, K. Yang, J. Wu, N. Ye, S. Guo and Z. Liao, "Achieving Sustainable Ultra-Dense Heterogeneous Networks for 5G," in IEEE Communications Magazine, vol. 55, no. 12, pp. 84-90, Dec. 2017, . [CrossRef]

- Z. Hasan, H. Boostanimehr and V. K. Bhargava, "Green Cellular Networks: A Survey, Some Research Issues and Challenges," in IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 524-540, Fourth Quarter 2011, . [CrossRef]

- Malathy, S., Jayarajan, P., Ojukwu, H. et al. A review on energy management issues for future 5G and beyond network. Wireless Netw 27, 2691–2718 (2021).

- Ishfaq Bashir Sofi, Akhil Gupta, A survey on energy efficient 5G green network with a planned multi-tier architecture, Journal of Network and Computer Applications, Volume 118, 2018, Pages 1-28, ISSN 1084-8045.

- 2021; Fatima Salahdine, Johnson Opadere, Qiang Liu, Tao Han, Ning Zhang, Shaohua Wu, A survey on sleep mode techniques for ultra-dense networks in 5G and beyond, Computer Networks, Volume 201, 2021, 108567, ISSN 1389-1286,.

- S. Jamil, Fawad, M. S. Abbas, M. Umair and Y. Hussain, "A Review of Techniques and Challenges in Green Communication," 2020 International Conference on Information Science and Communication Technology (ICISCT), Karachi, Pakistan, 2020, pp. 1-6, . [CrossRef]

- S. Buzzi, C. -L. I, T. E. Klein, H. V. Poor, C. Yang and A. Zappone, "A Survey of Energy-Efficient Techniques for 5G Networks and Challenges Ahead," in IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications, vol. 34, no. 4, pp. 697-709, April 2016, . [CrossRef]

- B. Mao, F. Tang, Y. Kawamoto and N. Kato, "AI Models for Green Communications Towards 6G," in IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 210-247, Firstquarter 2022, . [CrossRef]

- S, S.R.; Dragičević, T.; Siano, P.; Prabaharan, S.R.S. Future Generation 5G Wireless Networks for Smart Grid: A Comprehensive Review. Energies 2019, 12, 2140. [CrossRef]

- An Insight into Deployments of Green Base Stations (GBSs) for an Environmentally Sustainable World F. O. Ehiagwina1, O. O. Kehinde1, A. A. Adewale2, O. E. Seluwa1 and J. J. Anifowose3, Published under licence by IOP Publishing Ltd, IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, Volume 1107, nternational Conference on Engineering for Sustainable World (ICESW 2020) 10th-14th August 2020, Ota, Nigeria.

- Q. Wu, G. Y. Li, W. Chen, D. W. K. Ng and R. Schober, "An Overview of Sustainable Green 5G Networks," in IEEE Wireless Communications, vol. 24, no. 4, pp. 72-80, Aug. 2017, . [CrossRef]

- M. Feng, S. Mao and T. Jiang, "Base Station ON-OFF Switching in 5G Wireless Networks: Approaches and Challenges," in IEEE Wireless Communications, vol. 24, no. 4, pp. 46-54, Aug. 2017, . [CrossRef]

- Y. Alsaba, S. K. A. Rahim and C. Y. Leow, "Beamforming in Wireless Energy Harvesting Communications Systems: A Survey," in IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 1329-1360, Secondquarter 2018, . [CrossRef]

- Alsharif, M.H.; Kelechi, A.H.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.H. Energy Efficiency and Coverage Trade-Off in 5G for Eco-Friendly and Sustainable Cellular Networks. Symmetry 2019, 11, 408. [CrossRef]

- U. K. Dutta, M. A. Razzaque, M. Abdullah Al-Wadud, M. S. Islam, M. S. Hossain and B. B. Gupta, "Self-Adaptive Scheduling of Base Transceiver Stations in Green 5G Networks," in IEEE Access, vol. 6, pp. 7958-7969, 2018, . [CrossRef]

- Nicola Piovesan, Angel Fernandez Gambin, Marco Miozzo, Michele Rossi, Paolo Dini, Energy sustainable paradigms and methods for future mobile networks: A survey, Computer Communications, Volume 119,2018, Pages 101-117, ISSN 0140-3664. [CrossRef]

- S. Guo, D. Zeng and L. Gu, "Green C-RAN: A Joint Approach to the Design and Energy Optimization," 2017 IEEE 86th Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC-Fall), Toronto, ON, Canada, 2017, pp. 1-5, . [CrossRef]

- L. M. P. Larsen, S. Ruepp, M. S. Berger and H. L. Christiansen, "Energy Consumption Modelling of Next Generation Mobile Crosshaul Networks," 2021 IEEE International Conferences on Internet of Things (iThings) and IEEE Green Computing & Communications (GreenCom) and IEEE Cyber, Physical & Social Computing (CPSCom) and IEEE Smart Data (SmartData) and IEEE Congress on Cybermatics (Cybermatics), Melbourne, Australia, 2021, pp. 153-160, . [CrossRef]

- L. M. P. Larsen, H. L. Christiansen, S. Ruepp and M. S. Berger, "Toward Greener 5G and Beyond Radio Access Networks—A Survey," in IEEE Open Journal of the Communications Society, vol. 4, pp. 768-797, 2023, . [CrossRef]

- K. N. R. S. V. Prasad, E. Hossain and V. K. Bhargava, "Energy Efficiency in Massive MIMO-Based 5G Networks: Opportunities and Challenges," in IEEE Wireless Communications, vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 86-94, June 2017, . [CrossRef]

- Miao Yao, Munawwar M. Sohul, Xiaofu Ma, Vuk Marojevic, and Jeffrey H. Reed. 2019. Sustainable green networking: exploiting degrees of freedom towards energy-efficient 5G systems. Wirel. Netw. 25, 3 (April 2019), 951–960. [CrossRef]

- Shunqing Zhang, Qingqing Wu, Shugong Xu, and Geoffrey Ye Li. 2017. Fundamental Green Tradeoffs: Progresses, Challenges, and Impacts on 5G Networks. Commun. Surveys Tuts. 19, 1 (Firstquarter 2017), 33–56. [CrossRef]

- A. Bohli and R. Bouallegue, "How to Meet Increased Capacities by Future Green 5G Networks: A Survey," in IEEE Access, vol. 7, pp. 42220-42237, 2019, . [CrossRef]

- M. M. Mowla, I. Ahmad, D. Habibi and Q. V. Phung, "Energy Efficient Backhauling for 5G Small Cell Networks," in IEEE Transactions on Sustainable Computing, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 279-292, 1 July-Sept. 2019, . [CrossRef]

- S. R. Danve, M. S. Nagmode and S. B. Deosarkar, "Energy Efficient Cellular Network Base Station: A Survey," 2019 IEEE Pune Section International Conference (PuneCon), Pune, India, 2019, pp. 1-4, . [CrossRef]

- A. Jahid, M. H. Alsharif, P. Uthansakul, J. Nebhen and A. A. Aly, "Energy Efficient Throughput Aware Traffic Load Balancing in Green Cellular Networks," in IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 90587-90602, 2021, . [CrossRef]

- Alimi, I.A., Abdalla, A.M., Olapade Mufutau, A., Pereira Guiomar, F., Otung, I., Rodriguez, J., Pereira Monteiro, P. and Teixeira, A.L. (2019). Energy Efficiency in the Cloud Radio Access Network (C-RAN) for 5G Mobile Networks. In Optical and Wireless Convergence for 5G Networks (eds A.M. Abdalla, J. Rodriguez, I. Elfergani and A. Teixeira). [CrossRef]

- Dawadi, BR, Rawat, DB, Joshi, SR, Keitsch, MM. Towards energy efficiency and green network infrastructure deployment in Nepal using software defined IPv6 network paradigm. E J Info Sys Dev Countries. 2020; 86:e12114. doi: . [CrossRef]

- Alsharif, MH, Nordin, R, Abdullah, NF, Kelechi, AH. How to make key 5G wireless technologies environmental friendly: A review. Trans Emerging Tel Tech. 2018; 29:e3254. [CrossRef]

- Usama M, Erol-Kantarci M. A Survey on Recent Trends and Open Issues in Energy Efficiency of 5G. Sensors (Basel). 2019 Jul 15;19(14):3126. PMID: 31311203; PMCID: PMC6679251. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Shunliang & Cai, Xuejun & Zhou, Weihua & Wang, Yongming. (2019). Green 5G enabling technologies: An overview. IET Communications. 13. 10.1049/iet-com.2018.5448.

- Dlamini Thembelihle, Michele Rossi, Daniele Munaretto, "Softwarization of Mobile Network Functions towards Agile and Energy Efficient 5G Architectures: A Survey", Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing, vol. 2017, Article ID 8618364, 21 pages, 2017. [CrossRef]

- D. A. Temesgene, J. Nuñez-Martinez and P. Dini, "Softwarization and Optimization for Sustainable Future Mobile Networks: A Survey," in IEEE Access, vol. 5, pp. 25421-25436, 2017, . [CrossRef]

- E. J. Kitindi, S. Fu, Y. Jia, A. Kabir and Y. Wang, "Wireless Network Virtualization With SDN and C-RAN for 5G Networks: Requirements, Opportunities, and Challenges," in IEEE Access, vol. 5, pp. 19099-19115, 2017, . [CrossRef]

- Chih-Lin I., Han Shuangfeng, Xu Zhikun, Sun Qi and Pan Zhengang 20165G: rethink mobile communications for 2020+Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A.3742014043220140432.

- Q. Waseem, W. Isni Sofiah Wan Din, A. Aminuddin, M. Hussain Mohammed and R. F. Alfa Aziza, "Software-Defined Networking (SDN): A Review," 2022 5th International Conference on Information and Communications Technology (ICOIACT), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 2022, pp. 30-35, . [CrossRef]

- M. Mousa, A. M. Bahaa-Eldin and M. Sobh, "Software Defined Networking concepts and challenges," 2016 11th International Conference on Computer Engineering & Systems (ICCES), Cairo, Egypt, 2016, pp. 79-90, . [CrossRef]

- D. Kreutz, F. M. V. Ramos, P. E. Veríssimo, C. E. Rothenberg, S. Azodolmolky and S. Uhlig, "Software-Defined Networking: A Comprehensive Survey," in Proceedings of the IEEE, vol. 103, no. 1, pp. 14-76, Jan. 2015, . [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Suhail & Mir, Ajaz. (2023). SECURING CENTRALIZED SDN CONTROL WITH DISTRIBUTED BLOCKCHAIN TECHNOLOGY. Computer Science. 24. 10.7494/csci.2023.24.1.4605.

- ONF, [Online] Available: https://opennetworking.org/, Accessed on: January 26, 2025.

- Prados-Garzon, J., Adamuz-Hinojosa, O., Ameigeiras, P., Ramos-Munoz, J., Andres-Maldonado, P. & Lopez-Soler, J. Handover implementation in a 5G SDN-based mobile network architecture. 2016 IEEE 27th Annual International Symposium On Personal, Indoor, And Mobile Radio Communications (PIMRC). pp. 1-6 (2016).

- Ameigeiras, P., Ramos-munoz, J., Schumacher, L., Prados-Garzon, J., Navarro-Ortiz, J. & Lopez-soler, J. Link-level access cloud architecture design based on SDN for 5G networks. IEEE Network. 29, 24-31 (2015).

- Guerzoni, R., Trivisonno, R. & Soldani, D. SDN-Based Architecture and Procedures for 5G Networks. Proceedings Of The 2014 1st International Conference On 5G For Ubiquitous Connectivity, 5GU 2014. (2014,11).

- Silva, M., Teixeira, P., Gomes, C., Dias, D., Luís, M. & Sargento, S. Exploring software defined networks for seamless handovers in vehicular networks. Vehicular Communications. 31 pp. 100372 (2021), https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214209621000413.

- P. Göransson, C. Black, and T. Culver, “The OpenFlow Specification,” in Software Defined Networks, pp. 89–136, Elsevier, 2017.

- Pat Bosshart, Dan Daly, Glen Gibb, Martin Izzard, Nick McKeown, Jennifer Rexford, Cole Schlesinger, Dan Talayco, Amin Vahdat, George Varghese, and David Walker. 2014. P4: programming protocol-independent packet processors. SIGCOMM Comput. Commun. Rev. 44, 3 (July 2014), 87–95. [CrossRef]

- P4 Specification [Online] Available: https://github.com/p4lang/p4-spec/releases, Accessed on: February 02, 2025.

- P416 Language Specification, [Online] Available: https://p4.org/p4-spec/docs/P4-16-v1.2.2.html, Accessed on: February 03, 2025.

- Athanasios Liatifis, Panagiotis Sarigiannidis, Vasileios Argyriou, and Thomas Lagkas. 2023. Advancing SDN from OpenFlow to P4: A Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 55, 9, Article 186 (January 2023).

- Evangelos Haleplidis, Mojatatu Networks, "Overview of RFC7426: SDN Layers and Architecture", IEEE Softwarization, Canada, September 2017, [Online] Available: https://sdn.ieee.org/newsletter/september-2017/overview-of-rfc7426-sdn-layers-and-architecture-terminology, Accessed on: January 26, 2025.

- A. Shirvar and B. Goswami, "Performance Comparison of Software-Defined Network Controllers," 2021 International Conference on Advances in Electrical, Computing, Communication and Sustainable Technologies (ICAECT), Bhilai, India, 2021, pp. 1-13, . [CrossRef]

- Singh, R., Reliable and Secure M2M/IoT Communication Engineering: Control, Management, and Benchmarking, Department of Electrical and Photonics Engineering Networks Technology and Service Platforms, Technical University of Denmark.

- M. Gharbaoui et al., "Demonstration of Latency-Aware and Self-Adaptive Service Chaining in 5G/SDN/NFV infrastructures," 2018 IEEE Conference on Network Function Virtualization and Software Defined Networks (NFV-SDN), Verona, Italy, 2018, pp. 1-2, . [CrossRef]

- Overview, [Online] Available: https://www.infosys.com/services/engineering-services/service-offerings/sdn-5g-overview.html, Accessed on: January 26, 2025.

- S. K. Syed-Yusof, P. E. Numan, K. M. Yusof, J. B. Din, M. N. Bin Marsono and A. J. Onumanyi, "Software-Defined Networking (SDN) and 5G Network: The Role of Controller Placement for Scalable Control Plane," 2020 IEEE International RF and Microwave Conference (RFM), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2020, pp. 1-6, . [CrossRef]

- S. Khan Tayyaba and M. A. Shah, "5G cellular network integration with SDN: Challenges, issues and beyond," 2017 International Conference on Communication, Computing and Digital Systems (C-CODE), Islamabad, Pakistan, 2017, pp. 48-53, . [CrossRef]

- B. Allen et al., "Next-Generation Connectivity in A Heterogenous Railway World," in IEEE Communications Magazine, vol. 61, no. 4, pp. 34-40, April 2023. keywords: Rail transportation;Quality of service;GSM-R;5G mobile communication;3GPP;Europe . [CrossRef]

- Kreutz, D., Ramos, F. and Verissimo, P. (2013) Towards Secure and Dependable Software-Defined Networks. In Proceedings of the 2nd ACM SIGCOMM Workshop on Hot Topics in Software Defined Networking, ACM, New York, 55-60. [CrossRef]

- Maleh, Y., Qasmaoui, Y., El Gholami, K. et al. A comprehensive survey on SDN security: threats, mitigations, and future directions. J Reliable Intell Environ 9, 201–239 (2023). [CrossRef]

- S. Scott-Hayward, G. O’Callaghan and S. Sezer, "Sdn Security: A Survey," 2013 IEEE SDN for Future Networks and Services (SDN4FNS), Trento, Italy, 2013, pp. 1-7, . [CrossRef]

- Chen, M., Qian, Y., Mao, S., Tang, W., & Yang, X. (2016). Software-defined mobile networks security. Mobile Networks and Applications, 21(5), 729-743.

- S. MESSAOUDI, A. Ksentini and C. BONNET, "SDN Framework for QoS provisioning and latency guarantee in 5G and beyond," 2023 IEEE 20th Consumer Communications & Networking Conference (CCNC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2023, pp. 587-592, . [CrossRef]

- G. Kakkavas, A. Stamou, V. Karyotis and S. Papavassiliou, "Network Tomography for Efficient Monitoring in SDN-Enabled 5G Networks and Beyond: Challenges and Opportunities," in IEEE Communications Magazine, vol. 59, no. 3, pp. 70-76, March 2021, . [CrossRef]

- Network Functions Virtualisation (NFV) [Online] Available: https://www.etsi.org/technologies/nfv Accessed on: January 03, 2025.

- NFV Architectural Framework: The ETSI architectural framework explained [Online] Available: https://stlpartners.com/articles/network-innovation/nfv-architectural-framework/ Accessed on: January 03, 2025.

- What Is NFV. [Online] Available: https://info.support.huawei.com/info-finder/encyclopedia/en/NFV.html Accessed on: February 19, 2025.

- Liu Y, Ran J, Hu H, Tang B. Energy-Efficient Virtual Network Function Reconfiguration Strategy Based on Short-Term Resources Requirement Prediction. Electronics. 2021; 10(18):2287. [CrossRef]

- B. Kar, E. H. -K. Wu and Y. -D. Lin, "Energy Cost Optimization in Dynamic Placement of Virtualized Network Function Chains," in IEEE Transactions on Network and Service Management, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 372-386, March 2018, . [CrossRef]

- A. N. Al-Quzweeni, A. Q. Lawey, T. E. H. Elgorashi and J. M. H. Elmirghani, "Optimized Energy Aware 5G Network Function Virtualization," in IEEE Access, vol. 7, pp. 44939-44958, 2019, . [CrossRef]

- R. Mijumbi, J. Serrat, J. L. Gorricho, N. Bouten, F. De Turck, and R. Boutaba, “Network Function Virtualization: State-of-the-art and Research Challenges,” 9 2015.

- NFV C-RAN for Efficient RAN Resource Allocation [Online] Available: https://uk.nec.com/en_GB/en/global/solutions/nsp/sc2/doc/wp_c-ran.pdf, Accessed on: February 16, 2025.

- Network Function Virtualization or NFV Explained, [Online] Available: http://wikibon.org/wiki/v/Network_Function_Virtualization_or_NFV_Explained, Accessed on: February 06, 2025.

- Evgenia Nikolouzou, Goran Milenkovic, Georgia Bafoutsou and Slawomir Bryska (ENISA), NFV Security in 5G - Challenges and Best Practices, [Online] Available: https://www.enisa.europa.eu/publications/nfv-security-in-5g-challenges-and-best-practices, Accessed on: January 07, 2025.

- Security in SDN/NFV and 5G Networks - Opportunities and Challenges. Ashutosh Dutta, Senior Wireless Communication Systems Research Scientist, Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Labs (JHU/APL), [Online] Available: https://resourcecenter.fd.ieee.org/education/future-networks/fdfnweb0017?check_logged_in=1, Accessed on: January 23, 2025.

- Kamisiński, A. et al. (2020). Resilient NFV Technology and Solutions. In: Rak, J., Hutchison, D. (eds) Guide to Disaster-Resilient Communication Networks. Computer Communications and Networks. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- The Most Widely Deployed Open Source Cloud Software in the World, [Online] Available: https://www.openstack.org/, Accessed on: January 07, 2025.

- OPNFV, [Online] Available: https://www.opnfv.org/, Accessed on: January 07, 2025.

- Y. Zhang and S. Banerjee, "Efficient and verifiable service function chaining in NFV: Current solutions and emerging challenges," 2017 Optical Fiber Communications Conference and Exhibition (OFC), Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017, pp. 1-3.

- Evolving NFV towards the next decade, [Online] Available: https://www.etsi.org/images/files/ETSIWhitePapers/ETSI-WP-54-Evolving_NFV_towards_the_next_decade.pdf, Accessed on: January 17, 2025.

- White Paper - Huawei Observation to NFV, [Online] Available: https://www.huawei.com/mediafiles/CBG/PDF/Files/hw_399662.pdf Accessed on: February 20, 2025.

- Agrawal, R., Bedekar, A., Kolding, T. et al. Cloud RAN challenges and solutions. Ann. Telecommun. 72, 387–400 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Inline vs. lookaside: Which accelerator architecture is best for unlocking the benefits of Open vRAN? [Online] Available: https://networkblog.global.fujitsu.com/2024/01/11/inline-vs-lookaside-which-accelerator-architecture-is-best-for-unlocking-the-benefits-of-open-vran/, Accessed on: February 12, 2025.

- Fujitsu, "What is the difference between inline and lookaside accelerators in virtualized distributed units?", whitepaper, 2023.

- L. M. P. Larsen, H. L. Christiansen, S. Ruepp and M. S. Berger, "The Evolution of Mobile Network Operations: A Comprehensive Analysis of Open RAN Adoption" in Computer Networks, vol. 243, pp. 1389-1286, 2024, . [CrossRef]

- Iain Morris, "Chip choices kickstart open RAN war between lookaside and inline", https://www.lightreading.com/semiconductors/chip-choices-kickstart-open-ran-war-between-lookaside-and-inline, Accessed: January 20, 2025.

- 3GPP, "TR 38.801 V14.0.0: Study on new radio access technology: Radio access architecture and interfaces", Specification, 2017.

- L. M. P. Larsen, et al., “A Survey of the Functional Splits Proposed for 5G Mobile Crosshaul Networks.” IEEE Communications Surveys and Tutorials, vol. 21, no. 1, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2018, pp. 146–72, . [CrossRef]

- X. Rao, V. K. N. Lau, "Distributed fronthaul compression and joint signal recovery in cloud-RAN", IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing, 63(4), 1056–1065. [CrossRef]

- L. M. P. Larsen, M. S. Berger, and H. L. Christiansen, “Energy-Aware Technology Comparisons for 5G Mobile Fronthaul Networks,” International Journal on Advances in Networks and Services, vol. 13, no. 1&2, pp. 21–32, 2020.

- NGMN Alliance, “NGMN Overview on 5G RAN Functional Decomposition,” whitepaper, 2018.

- O-RAN alliance, "O-RAN.WG9.XPSAAS.0-R003-v06.00: Xhaul Packet Switched Architectures and Solutions", Technical specification, 2023.

- IEEE Communications Society, “IEEE Std 1914.1-2019: IEEE Standard for Packet-based Fronthaul Transport Network,” specification, 2019.

- Small Cell Forum, “159.07.02: Small cell virtualization functional splits and use cases,” technical report, 2016.

- NGMN Alliance, “Green future networks: Network energy efficiency,” Whitepaper, 2021.

- Webpage - CPRI Specifications, [Online] Available: http://www.cpri.info/spec.html, Accessed on: February 09, 2025.

- O-RAN Alliance Work Group 4 (Open Fronthaul Interfaces Working Group), "O-RAN.WG4.CUS.0-R003-v13.00: Control, User and Synchronization Plane Specification", Specification, 2023.

- ONF, [Online] Available: https://opennetworking.org/, Accessed on: January 12, 2025.

- ETSI, [Online] Available: https://www.etsi.org/, Accessed on: January 12, 2025.

- G. C. Valastro, D. Panno & S. Riolo, "A SDN/NFV based C-RAN architecture for 5G Mobile Networks," International Conference on Selected Topics in Mobile and Wireless Networking (MoWNeT), Morocco, 2018, pp. 1-8, . [CrossRef]

- Tayyaba, S.K., Shah, M.A. Resource allocation in SDN based 5G cellular networks. Peer-to-Peer Netw. Appl. 12, 514–538 (2019). [CrossRef]

- I. Parvez, A. Rahmati, I. Guvenc, A. I. Sarwat and H. Dai, "A Survey on Low Latency Towards 5G: RAN, Core Network and Caching Solutions," in IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, vol. 20, no. 4, pp. 3098-3130, Fourthquarter 2018, . [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar Buyya; Satish Narayana Srirama, "Management and Orchestration of Network Slices in 5G, Fog, Edge, and Clouds," in Fog and Edge Computing: Principles and Paradigms, Wiley, 2019, pp.79-101, . [CrossRef]

- Sehrish Khan Tayyaba, Resource Allocation and Bandwidth Optimization in SDN-Based Cellular Network, PhD Thesis in Computer Science, COMSATS University Islamabad, Pakistan, Spring, 2020.

- Murillo, Andrés & Rueda, Sandra & Morales, Laura & Cardenas, Alvaro. (2017). SDN and NFV Security: Challenges for Integrated Solutions. [CrossRef]

- W. H. Al-Zubaedi, S. R. Aldaeabool, M. F. Abbod and H. S. Al-Raweshidy, "Reducing Energy Consumption and Operating Costs in C-RAN Based on DWDM/SCM-PON-RoF," 2018 10th Computer Science and Electronic Engineering (CEEC), Colchester, UK, 2018, pp. 95-100, . [CrossRef]

- Nokia 5G Core (5GC) [Online] Available: https://www.nokia.com/networks/core/5g-core/, Accessed on: January 05, 2025.

- 5G Core Network – Architecture, Network Functions, and Interworking, [Online] Available: https://www.rfglobalnet.com/doc/g-core-network-architecture-network-functions-and-interworking-0001, Accessed on: January 15, 2025.

- Som D, 5G Core Network Architecture: Detailed Guide, [Online] Available: https://networkbuildz.com/5g-core-network-architecture/, Accessed on: February 16, 2025.

- Chen, WS., Leu, FY. (2020). The Study on AUSF Fault Tolerance. In: Barolli, L., Okada, Y., Amato, F. (eds) Advances in Internet, Data and Web Technologies. EIDWT 2020. Lecture Notes on Data Engineering and Communications Technologies, vol 47. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- A. Orsino, G. Araniti, L. Wang, and A. Iera, “Enhanced C-RAN Architecture Supporting SDN and NFV Functionalities for D2D Communications,” pp. 3–12, 2016.

- Papidas AG, Polyzos GC. Self-Organizing Networks for 5G and Beyond: A View from the Top. Future Internet. 2022; 14(3):95. [CrossRef]

- Salman, Tara. “Cloud RAN: Basics, Advances and Challenges A Survey of CRAN Basics, Virtualization, Resource Allocation, and Challenges.” (2016).

- T. X. Tran, A. Younis and D. Pompili, "Understanding the Computational Requirements of Virtualized Baseband Units Using a Programmable Cloud Radio Access Network Testbed," 2017 IEEE International Conference on Autonomic Computing (ICAC), Columbus, OH, USA, 2017, pp. 221-226, . [CrossRef]

- Abdelhakam, Mostafa & Elmesalawy, Mahmoud & Elhattab, Mohamed & Esmat, Haitham. (2020). Energy-efficient BBU Pool Virtualisation for C-RAN with QoS Guarantees. IET Communications. 14. [CrossRef]

- I. Parvez, A. Rahmati, I. Guvenc, A. I. Sarwat and H. Dai, "A Survey on Low Latency Towards 5G: RAN, Core Network and Caching Solutions," in IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, vol. 20, no. 4, pp. 3098-3130, Fourthquarter 2018, . [CrossRef]

- Virtualized 5G RAN: why, when and how? [Online] Available: https://www.ericsson.com/en/blog/2020/2/virtualized-5g-ran-why-when-and-how, Accessed on: January 13, 2025.

- The four key components of Cloud RAN, [Online] Available: https://www.ericsson.com/en/blog/2020/8/the-four-components-of-cloud-ran, Accessed on: February 17, 2025.

- 3GPP 5G System Overview, [Online] Available: https://www.3gpp.org/technologies/5g-system-overview, Accessed on: February 15, 2025.

- Sylla T, Mendiboure L, Maaloul S, Aniss H, Chalouf MA, Delbruel S. Multi-Connectivity for 5G Networks and Beyond: A Survey. Sensors. 2022; 22(19):7591. [CrossRef]

- Pliatsios, D., Sarigiannidis, P., Goudos, S. et al. Realizing 5G vision through Cloud RAN: technologies, challenges, and trends. J Wireless Com Network 2018, 136 (2018). [CrossRef]

- NEC White Paper, NFV CRAN for Efficient RAN Resource Allocation, [Online] Available: https://uk.nec.com/en_GB/en/global/solutions/nsp/sc2/doc/wp_c-ran.pdf, Accessed on: January 14, 2025.

- Samsung Joins Forces with Industry Leaders to Advance 5G vRAN Ecosystem, [Online] Available: https://www.samsung.com/global/business/networks/insights/press-release/0228-samsung-joins-forces-with-industry-leaders-to-advance-5g-vran-ecosystem/, Accessed on: January 13, 2025.

- What is vRAN (virtualized RAN)? [Online] Available: https://www.rcrwireless.com/20210916/5g/what-is-vran-virtualized-ran, Accessed on: January 13, 2025.

- 5G Companies: Which Players are Leading the Market? [Online] Available: https://www.greyb.com/blog/5g-companies/, Accessed on: January 13, 2025.

| Category | NFV | SDN |

|---|---|---|

| Concept | Abstracts network functions from conventional devices and encapsulates them as software. |

Separates the forwarding plane from the control plane to enable automated and programmable network control. |

| Goal | Service providers propose replacing distributed network devices with consolidated ones. |

To achieve network hardware devices’ programmability and centralized management and control. |

| Key Aspects | 1. Established procedure 2. Hardware-based forwarding functions are detached from dedicated hardware |

1. An open and programmable control plane, 2. Hardware-based traffic forwarding, and decision-making within the control plane. |

| Conflict or Not | The fusion of NFV and SDN introduces a novel network model. NFV enables adaptable service orchestration, while SDN realizes unified management and configuration of network functions. |

|

| Category | NFV | Proprietary Network Equipment/Devices |

|---|---|---|

| Hardware Used | Generic x86-based servers, versatile storage devices, and adaptable switching equipment are utilized. | Dedicated devices are used. |

| Hardware-Software Separation | Software is separated from hardware and provided as module components. | Hardware and software are closely integrated, with software functions relying on dedicated hardware. |

| Receptiveness | Universal hardware foundation and standardized interfaces enable an open ecosystem through collaboration among multiple parties. | Relying on dedicated services results in a closed system, making it challenging to onboard third-party partners. |

| Network Resilience | General-purpose hardware and resource virtualization technologies enable dynamic adjustments of both software and hardware resources to meet specific service demands. | Dedicated devices do not align with virtualization technologies, hindering resource-sharing and flexible scaling capabilities. |

| Upgradation | Device upgrades occur swiftly, primarily involving software enhancements. | Deployment of network devices is time-consuming, necessitating both software and hardware provisioning. |

| Operation and Management | Virtualizes hardware resources and automates operations and management intelligently. | Upgrading and replacing devices is a complex process, as maintenance involves manual or semi-manual preparations and configurations through the CLI or web-based systems. |

| Service Organizations | NFV networks are deployed according to service requirements and can be dynamically orchestrated with flexibility. | Traditional networks operate with relative independence. Converting service requirements into network specifications is not swift, resulting in a sluggish network response. |

| Category | Centralized RAN | Virtualized RAN | Cloud RAN |

|---|---|---|---|

| Concept | Baseband processing is moved away from the cell sites to a central baseband pool. | Baseband processing is virtualized, running as software instances independently from the underlying hardware. | Virtualized baseband processing is centralized in a datacenter. Deployment options are agile. |

| Benefits | Reduced site footprint, improved cell cooperation, and shared cooling mechanisms. | Load balancing, agile service deployment, faster updates. | In addition to the benefits derived from centralized and virtualized RAN, Cloud-RAN also benefits from dynamic capacity assignment, improved scalability, and increased resource utilization. |

| Drawbacks | Large capacity and latency requirements for the transport network connecting radio functions to centralized baseband processing (fronthaul network). | Complexity of virtualized functions and challenges in running time-critical RAN functions on COTS hardware. | Cloud-RAN faces the same drawbacks as virtualized RAN, but its agile deployment options can reduce fronthaul complexity seen in centralized RAN. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).