Submitted:

02 March 2025

Posted:

05 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Basis and Research Hypothesis

2.1. Risk Management

2.2. Digital Technology Literacy

2.3. Modern Learning Environment

2.4. Student Resilience

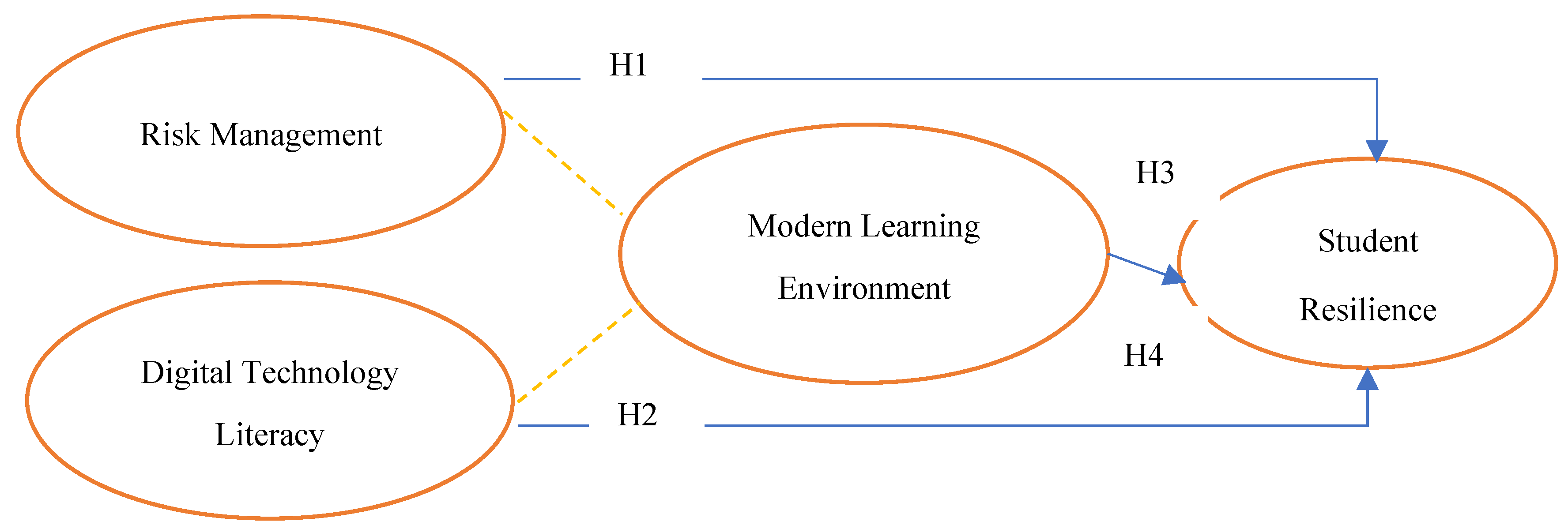

2.5. Hypothesized Model

2.5.1. Risk Management and Student Resilience

2.5.2. Digital Technology Literacy and Student Resilience

2.5.3. Modern Learning Environment as a Moderating Variable

3. Research Methods

3.1. Profile Responden

3.2. Measurement

3.3. Method

4. Data Analysis

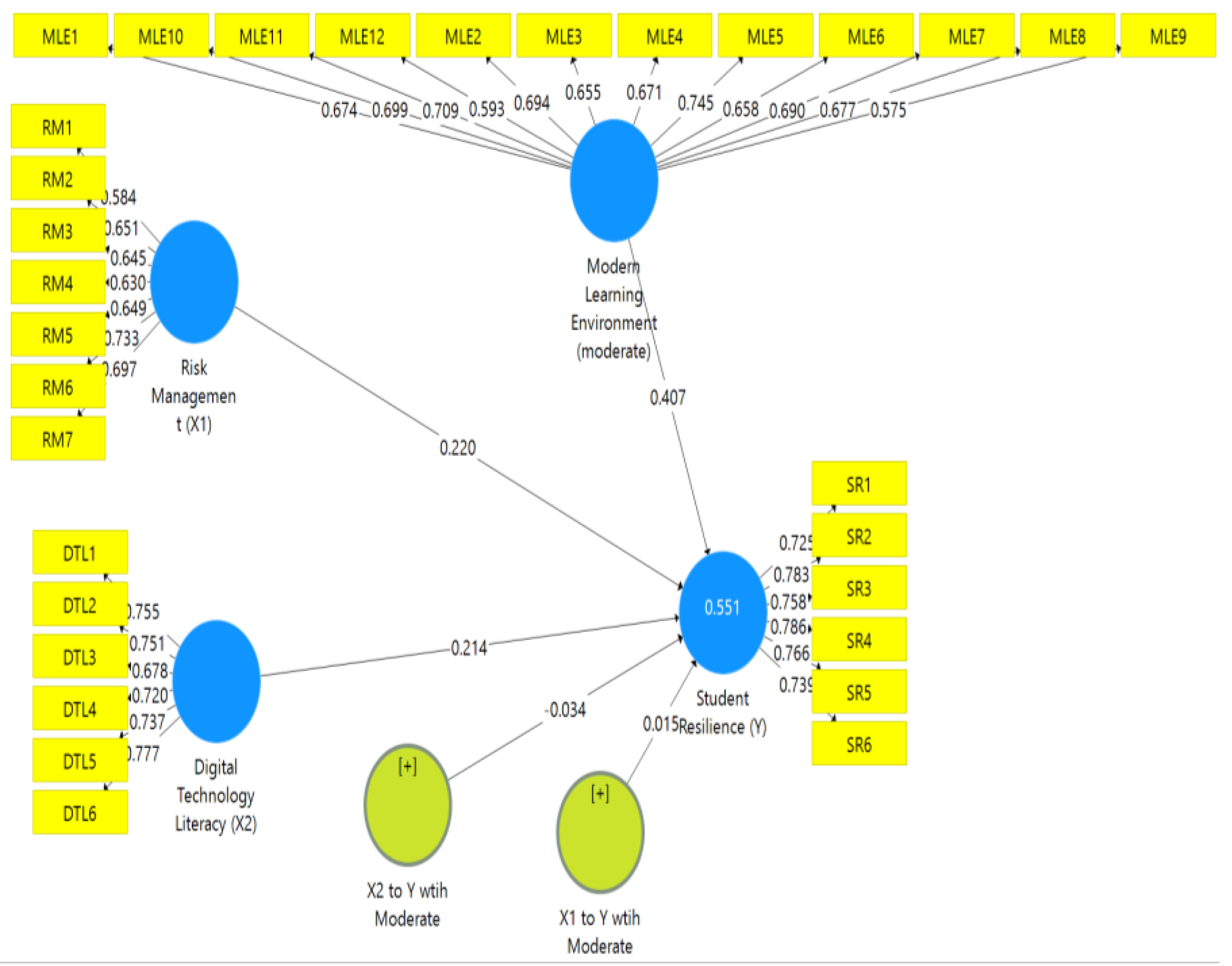

4.1. Measurement and Structural Model

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

- 1)

- H1: Risk Management has a positive and significant effect on Student Resilience

- 1)

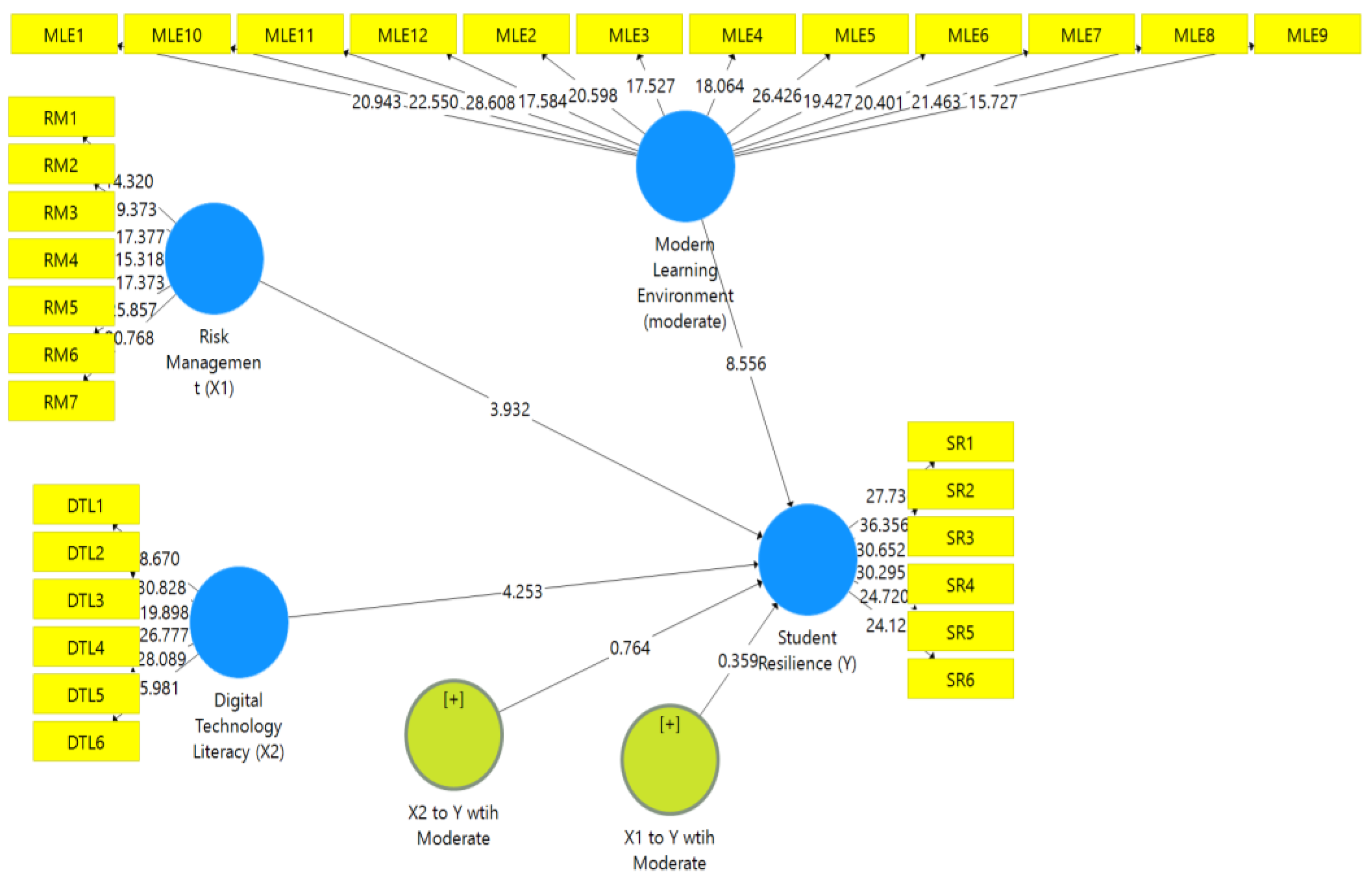

- The results show a path coefficient of 0.220, t-statistics of 3.932 (greater than 1.96), and a p-value of 0.000 (below 0.05). This confirms that effective risk management implementation significantly enhances student resilience. Institutions with well-implemented risk management approaches provide better support for students in overcoming learning challenges.

- 2)

- H2: Digital Technology Literacy has a positive and significant effect on Student Resilience

- 2)

- With a path coefficient of 0.214, t-statistics of 4.253, and a p-value of 0.000, the results indicate that high digital technology literacy significantly contributes to strengthening student resilience. Students with strong technological skills are better equipped to adapt and utilize technology to support their learning process.

- 3)

- H3: Modern Learning Environment moderates the relationship between Risk Management and Student Resilience

- 3)

- path coefficient of 0.407, t-statistics of 8.556, and a p-value of 0.000 show that the modern learning environment significantly strengthens the relationship between risk management and student resilience. Modern learning infrastructure and technology act as catalysts that enhance the effectiveness of risk management in supporting student resilience.

- 4)

- H4: Modern Learning Environment moderates the relationship between Digital Technology Literacy and Student Resilience

- 4)

- With a path coefficient of 0.015, t-statistics of 5.129, and a p-value of 0.000, the results indicate that the modern learning environment significantly strengthens the effect of digital technology literacy on student resilience. A supportive modern learning environment enables students to maximize the use of digital technology literacy in addressing academic challenges.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Risk Management Has a Significant Positive Effect On Student Resilience

5.2. Digital Technology Literacy Has a Significant Positive Effect On Student Resilience

5.3. Modern Learning Environment Moderates the Relationship Between Risk Management and Student Resilience

5.4. Modern Learning Environment Moderates the Relationship Between Digital Technology Literacy and Student Resilience

5.5. Conclusion

6. Theoretical Implications

7. Practical Implications

8. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HRM | Human Resource Management |

| SET | Social Exchange Theory |

| SDT | Self-Determination Theory |

| CSR | Corporate Social Responsibility |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ICT | Information and Communication Technology |

| MLE | Modern Learning Environment |

| PLS-SEM | Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling |

References

- Ahmad, I. , Sharma, S., Singh, R., Gehlot, A., Gupta, L. R., Thakur, A. K., Priyadarshi, N., & Twala, B. Inclusive learning using industry 4.0 technologies: addressing student diversity in modern education. Cogent Education. [CrossRef]

- Akpen, C. N. , Asaolu, S., Atobatele, S., Okagbue, H., & Sampson, S. Impact of online learning on student’s performance and engagement: a systematic review. Discover Education 2024, 3, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aladini, A. , Bayat, S., & Abdellatif, M. S. Performance-based assessment in virtual versus non-virtual classes: impacts on academic resilience, motivation, teacher support, and personal best goals. Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education 2024, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldridge, J. M. , Blackstock, M. J., & McLure, F. I. School climate: Using a person–environment fit perspective to inform school improvement. Learning Environments Research 2024, 27, 411–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amo-Filva, D. , Escudero, D. F., Sanchez-Sepulveda, M. V., García-Holgado, A., García-Holgado, L., García-Peñalvo, F. J., Orehovački, T., Krašna, M., Pesek, I., Marchetti, E., Valente, A., Witfelt, C., Ružić, I., Fraoua, K. E., & Moreira, F. (2023). Security and Privacy in Academic Data Management at Schools: SPADATAS Project. [CrossRef]

- Anthonysamy, L. Being learners with mental resilience as outcomes of metacognitive strategies in an academic context. Cogent Education 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthonysamy, L. , Koo, A. C., & Hew, S. H. Self-regulated learning strategies in higher education: Fostering digital literacy for sustainable lifelong learning. Education and Information Technologies 2020, 25, 2393–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assefa, Y. , Gebremeskel, M. M., Moges, B. T., Tilwani, S. A., & Azmera, Y. A. (2024). Rethinking the digital divide and associated educational in(equity) in higher education in the context of developing countries: the social justice perspective. The International Journal of Information and Learning Technology. [CrossRef]

- Audrin, C. , & Audrin, B. Key factors in digital literacy in learning and education: a systematic literature review using text mining. Education and Information Technologies 2022, 27, 7395–7419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baanqud, N. S. , Al-Samarraie, H., Alzahrani, A. I., & Alfarraj, O. Engagement in cloud-supported collaborative learning and student knowledge construction: a modeling study. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 2020, 17, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balica, M. (n.d.). SUPPORTING STUDENT WELLBEING.

- Barbayannis, G. , Bandari, M., Zheng, X., Baquerizo, H., Pecor, K. W., & Ming, X. (2022). Academic Stress and Mental Well-Being in College Students: Correlations, Affected Groups, and COVID-19. Frontiers in Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Beale, J. , & K. I. (2023). Building Academic Resilience in Secondary School Students: A Research Review and Case Study. In Transcending Crisis by Attending to Care, Emotion, and Flourishing, Routledge.

- Bernacki, M. L. , Greene, M. J., & Lobczowski, N. G. A Systematic Review of Research on Personalized Learning: Personalized by Whom, to What, How, and for What Purpose(s)? Educational Psychology Review 2021, 33, 1675–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertsia, V. , & Poulou, M. Resilience: Theoretical Framework and Implications for School. International Education Studies 2023, 16, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne Jacobson. (2021, April 19). Risk management in digital transformation for universities, 19 April.

- Buchan, M. C. , Bhawra, J., & Katapally, T. R. Navigating the digital world: development of an evidence-based digital literacy program and assessment tool for youth. Smart Learning Environments 2024, 11, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulut, M. , Bulut, A., Kaban, A., & Kirbas, A. Exploring the Nexus of Technology, Digital, and Visual Literacy: A Bibliometric Analysis. International Journal of Education in Mathematics, Science and Technology 2023, 12, 345–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahill, H. , & Dadvand, B. (2020). Social and Emotional Learning and Resilience Education. In Health and Education Interdependence (pp. 205–223). Springer Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, F. , Blank, L., Cantrell, A., Baxter, S., Blackmore, C., Dixon, J., & Goyder, E. Factors that influence mental health of university and college students in the UK: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carsone, B. , Bell, J., & Smith, B. Fostering academic resilience in higher education. Fostering academic resilience in higher education. Journal of Perspectives in Applied Academic Practice 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassidy, S. (2015). Resilience Building in Students: The Role of Academic Self-Efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Cattelino, E. , Testa, S., Calandri, E., Fedi, A., Gattino, S., Graziano, F., Rollero, C., & Begotti, T. Self-efficacy, subjective well-being and positive coping in adolescents with regard to Covid-19 lockdown. Current Psychology 2023, 42, 17304–17315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cayubit, R. F. O. Why learning environment matters? An analysis on how the learning environment influences the academic motivation, learning strategies and engagement of college students. Learning Environments Research 2022, 25, 581–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G. W. , Cooper-Thomas, H. D., Lau, R. S., & Wang, L. C. Reporting reliability, convergent and discriminant validity with structural equation modeling: A review and best-practice recommendations. Asia Pacific Journal of Management 2024, 41, 745–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, S. K. S. , Kwok, L. F., Phusavat, K., & Yang, H. H. Shaping the future learning environments with smart elements: challenges and opportunities. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 2021, 18, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chye, S. M. , Kok, Y. Y., Chen, Y. S., & Er, H. M. Building resilience among undergraduate health professions students: identifying influencing factors. BMC Medical Education 2024, 24, 1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ColourmyLearning. (n.d.). Essential Skills for University Students: Adaptability and Resilience, 2024.

- Contrino, M. F. , Reyes-Millán, M., Vázquez-Villegas, P., & Membrillo-Hernández, J. Using an adaptive learning tool to improve student performance and satisfaction in online and face-to-face education for a more personalized approach. Smart Learning Environments 2024, 11, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COSO. (n.d.). Enterprise Risk Management.

- Cowling, M. , Sim, K. N., Orlando, J., & Hamra, J. (2024). Untangling Digital Safety, literacy, and Wellbeing in School activities for 10 to 13 Year Old Students. Education and Information Technologies. [CrossRef]

- Demir, K. A. Smart education framework. Smart Learning Environments 2021, 8, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depedtambayan. (n.d.). Enhancing Student Engagement through Interactive Teaching Methods: Strategies and Best Practices for Educators.

- DLE. (2024, November 25). Effective Strategies for Online Learning Risk Management, 25 November.

- Drossel, K. , Eickelmann, B., & Vennemann, M. Schools overcoming the digital divide: in depth analyses towards organizational resilience in the computer and information literacy domain. Large-Scale Assessments in Education 2020, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duin, A. H. , Pedersen, I., & Tham, J. (2021). Building Digital Literacy Through Exploration and Curation of Emerging Technologies: A Networked Learning Collaborative. [CrossRef]

- Dursun, C. (2024). Risk Management in Digital Era: Opportunities and Challenges. [CrossRef]

- Dwiningrum, S. I. A. , Rukiyati, R., Setyaningrum, A., Sholikhah, E., & Sitompul, N. Digital Literacy Requires School Resilience. Jurnal Kependidikan Penelitian Inovasi Pembelajaran 2023, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Galad, A. , Betts, D. H., & Campbell, N. (2024). Flexible learning dimensions in higher education: aligning students’ and educators’ perspectives for more inclusive practices. Frontiers in Education. [CrossRef]

- Elmoazen, R. , Saqr, M., Khalil, M., & Wasson, B. Learning analytics in virtual laboratories: a systematic literature review of empirical research. Smart Learning Environments 2023, 10, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sabagh, H. A. Adaptive e-learning environment based on learning styles and its impact on development students’ engagement. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 2021, 18, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y. Van. Digital integration for clean technologies: sustainability and policy implications. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy 2024, 26, 2753–2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, M. S. , & Evans, K. B. Integrating Digital Tools to Enhance Access to Learning Opportunities in Project-based Science Instruction. TechTrends 2024, 68, 882–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, A. , Zriker, A., & Sapir, Z. Optimal educational climate among students at risk: the role of teachers’ work attitudes. European Journal of Psychology of Education 2022, 37, 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiutinova, E. I. , & Pervushina, T. L. (2021). Educational Institution Risk Management Model. [CrossRef]

- Galos, S. , & Aldridge, J. M. Relationships between learning environments and self-efficacy in primary schools and differing perceptions of at-risk students. Learning Environments Research 2021, 24, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerardo, V. , & Fajar, A. N. Academic IS Risk Management using OCTAVE Allegro in Educational Institution. Journal of Information Systems and Informatics 2022, 4, 687–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getenet, S. , Cantle, R., Redmond, P., & Albion, P. Students’ digital technology attitude, literacy and self-efficacy and their effect on online learning engagement. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 2024, 21, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, A. , Masurkar, S., & Pathade, G. R. An Overview of Digital Transformation and Environmental Sustainability: Threats, Opportunities, and Solutions. Sustainability 2024, 16, 11079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, S. , Ferreira, L., Pereira, L., & Sousa, B. (2025). The Influence of Resilience on the Digital Resilience of Higher Education Students: Preliminary Insights. [CrossRef]

- Gourisaria, M. K. , Chufare, A. T., & Banik, D. (2023). Cybersecurity Imminent Threats with Solutions in Higher Education. [CrossRef]

- Grierson, E. M. Modern learning environments. Educational Philosophy and Theory 2017, 49, 743–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grima, S., T. E., C. M., K. M., M. D., & P. L. (Eds. ). (2023). Digital transformation, strategic resilience, cyber security and risk management.

- Grima, S. , Thalassinos, E., Cristea, M., Kadłubek, M., Maditinos, D., & Peiseniece, L. (Eds.). (2023). Digital Transformation, Strategic Resilience, Cyber Security and Risk Management. [CrossRef]

- Guaña-Moya, J. , Salgado-Reyes, N., Arteaga-Alcívar, Y., & Espinosa-Cevallos, A. (2024a). Importance of Cybersecurity Education to Reduce Risks in Academic Institutions. [CrossRef]

- Guaña-Moya, J. , Salgado-Reyes, N., Arteaga-Alcívar, Y., & Espinosa-Cevallos, A. (2024b). Importance of Cybersecurity Education to Reduce Risks in Academic Institutions. [CrossRef]

- Gull, M. , Parveen, S., & Sridadi, A. R. Resilient higher educational institutions in a world of digital transformation. Foresight 2024, 26, 755–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F. , Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N. P., & Ray, S. (2021). Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R. [CrossRef]

- Handley, F. J. L. Developing Digital Skills and Literacies in UK Higher Education: Recent developments and a case study of the Digital Literacies Framework at the University of Brighton, UK. PUBLICACIONES 2018, 48, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M. A. , Ahmad, S., John, A., Mishra, K., Mishra, B. K., Kumar, K., & Nazeer, J. Cybersecurity in Universities: An Evaluation Model. SN Computer Science 2023, 4, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J. , Hubona, G., & Ray, P. A. Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: updated guidelines. Industrial Management & Data Systems 2016, 116, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdsworth, S. , Turner, M., & Scott-Young, C. M. (2019). Developing the Resilient Learner: A Resilience Framework for Universities. In Transformations in Tertiary Education (pp. 27–42). Springer Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Holm, P. (2024). Impact of digital literacy on academic achievement: Evidence from an online anatomy and physiology course. E-Learning and Digital Media. [CrossRef]

- Huang, R. , Adarkwah, M. A., Liu, M., Hu, Y., Zhuang, R., & Chang, T. (2024). Digital Pedagogy for Sustainable Education Transformation: Enhancing Learner-Centred Learning in the Digital Era. Frontiers of Digital Education. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, R. K. , Al Sabbah, S., Al-Jarrah, M., Senior, J., Almomani, J. A., Darwish, A., Albannay, F., & Al Naimat, A. The mediating effect of digital literacy and self-regulation on the relationship between emotional intelligence and academic stress among university students: a cross-sectional study. BMC Medical Education 2024, 24, 1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izumi, T., P. I., & S. R. (2022). Safety and resilience of higher educational institutions.

- Jaya, F. , & Sucipto, S. Digital Literacy, Academic Self-Efficacy, and Student Engagement: Its Impact on Student Academic Performance in Hybrid Learning. Journal of Innovation in Educational and Cultural Research 2023, 4, 458–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Mijangos, L. P. , Rodríguez-Arce, J., Martínez-Méndez, R., & Reyes-Lagos, J. J. Advances and challenges in the detection of academic stress and anxiety in the classroom: A literature review and recommendations. Education and Information Technologies 2023, 28, 3637–3666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jisc. (n.d.). Digital transformation in higher education.

- Jisc. (2023, March 7). Framework for digital transformation in higher education, 7 March.

- Kaspar, K. , Burtniak, K., & Rüth, M. Online learning during the Covid-19 pandemic: How university students’ perceptions, engagement, and performance are related to their personal characteristics. Current Psychology 2024, 43, 16711–16730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerimbayev, N. , Umirzakova, Z., Shadiev, R., & Jotsov, V. A student-centered approach using modern technologies in distance learning: a systematic review of the literature. Smart Learning Environments 2023, 10, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keržič, D. , Alex, J. K., Pamela Balbontín Alvarado, R., Bezerra, D. da S., Cheraghi, M., Dobrowolska, B., Fagbamigbe, A. F., Faris, M. E., França, T., González-Fernández, B., Gonzalez-Robledo, L. M., Inasius, F., Kar, S. K., Lazányi, K., Lazăr, F., Machin-Mastromatteo, J. D., Marôco, J., Marques, B. P., Mejía-Rodríguez, O., … Aristovnik, A. Academic student satisfaction and perceived performance in the e-learning environment during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence across ten countries. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0258807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanal, S. , & P. S. R. (2024). Analysis, Modeling and Design of Personalized Digital Learning Environment. ArXiv Preprint ArXiv:2405.10476.

- Khaw, T. Y. , & Teoh, A. P. Risk management in higher education research: a systematic literature review. Quality Assurance in Education 2023, 31, 296–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. J. , Hong, A. J., & Song, H.-D. The roles of academic engagement and digital readiness in students’ achievements in university e-learning environments. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 2019, 16, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimmons, R. Safeguarding student privacy in an age of analytics. Educational Technology Research and Development 2021, 69, 343–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, C. , Khoo, S.-M., Czerniewicz, L., Lilley, W., Bute, S., Crean, A., Abegglen, S., Burns, T., Sinfield, S., Jandrić, P., Knox, J., & MacKenzie, A. Understanding Digital Inequality: A Theoretical Kaleidoscope. Postdigital Science and Education 2023, 5, 894–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagubeau, G., T. S., & H. C. Active learning reduces academic risk of students with nonformal reasoning skills: Evidence from an introductory physics massive course in a Chilean public university. Physical Review Physics Education Research.

- Lavanya, Dr. P. , Kumari, B. S. S., & Padmambika, P. (2024a). Collaborative learning and group dynamics in digital environments. ( 6(2), 105–108. [CrossRef]

- Lavanya, Dr. P. , Kumari, B. S. S., & Padmambika, P. (2024b). Collaborative learning and group dynamics in digital environments. ( 6(2), 105–108. [CrossRef]

- Li, H. , Martin, A. J., & Yeung, W.-J. J. Academic risk and resilience for children and young people in Asia. Educational Psychology 2017, 37, 921–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K. , Wang, H., Siu, O.-L., & Yu, H. How and When Resilience can Boost Student Academic Performance: A Weekly Diary Study on the Roles of Self-Regulation Behaviors, Grit, and Social Support. Journal of Happiness Studies 2024, 25, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. , Xu, Y., & Wen, C. (2024). Digital pathways to sustainability: the impact of digital infrastructure in the coordinated development of environment, economy and society. Environment, Development and Sustainability. [CrossRef]

- Lin, J. , & Zhan, M. The influence of university management strategies and student resilience on students well-being & psychological distress: investigating coping mechanisms and autonomy as mediators and parental support as a moderator. Current Psychology 2024, 43, 25604–25620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-L. , & Wang, W.-T. Enhancing students’ online collaborative PBL learning performance in the context of coauthoring-based technologies: A case of wiki technologies. Education and Information Technologies 2024, 29, 2303–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, V. I. , & Castañeda, L. (2022). Developing Digital Literacy for Teaching and Learning. In Handbook of Open, Distance and Digital Education (pp. 1–20). Springer Nature Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Martin, A. , & M. H. (2020). Student resilience and boosting academic buoyancy.

- Martin, A. J. , Collie, R. J., & Nagy, R. P. (2021). Adaptability and High School Students’ Online Learning During COVID-19: A Job Demands-Resources Perspective. Frontiers in Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Masten, A. S. , Nelson, K. M., & Gillespie, S. (2022). Resilience and Student Engagement: Promotive and Protective Processes in Schools. In Handbook of Research on Student Engagement (pp. 239–255). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Matías-García, J. A. , Cubero, M., Santamaría, A., & Bascón, M. J. The learner identity of adolescents with trajectories of resilience: the role of risk, academic experience, and gender. European Journal of Psychology of Education 2024, 39, 2739–2761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsieli, M. , & Mutula, S. COVID-19 and Digital Transformation in Higher Education Institutions: Towards Inclusive and Equitable Access to Quality Education. Education Sciences 2024, 14, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meepung, T. , Pratsri, S., & Nilsook, P. Interactive Tool in Digital Learning Ecosystem for Adaptive Online Learning Performance. Higher Education Studies 2021, 11, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejeh, M. , & Rehm, M. Taking adaptive learning in educational settings to the next level: leveraging natural language processing for improved personalization. Educational Technology Research and Development 2024, 72, 1597–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meridha, J. M. The causes of poor digital literacy in educational practice, and possible solutions among the stakeholders: a systematic literature review. SN Social Sciences 2024, 4, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnett, K. , & Stephenson, Z. (2024). Exploring the Psychometric Properties of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Adversity and Resilience Science. [CrossRef]

- Miranda, P. , Isaias, P., & Pifano, S. (2018). Digital Literacy in Higher Education. [CrossRef]

- Mithembu, Thato. (2024, September 6). Powering Progress: How Learning Management Systems Shape Modern Education, 6 September.

- Motz, R. , Porta, M., & Reategui, E. (2023). Building Resilient Educational Systems: The Power of Digital Technologies. [CrossRef]

- Namaziandost, E. , Heydarnejad, T., & Azizi, Z. To be a language learner or not to be? The interplay among academic resilience, critical thinking, academic emotion regulation, academic self-esteem, and academic demotivation. Current Psychology 2023, 42, 17147–17162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L. A. T. , & Habók, A. Tools for assessing teacher digital literacy: a review. Journal of Computers in Education 2024, 11, 305–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odlin, D. , Benson-Rea, M., & Sullivan-Taylor, B. Student internships and work placements: approaches to risk management in higher education. Higher Education 2022, 83, 1409–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- One Education. (2024, July 30). Understanding Resilience and Its Importance in Education, 30 July.

- Otto, S. , Bertel, L. B., Lyngdorf, N. E. R., Markman, A. O., Andersen, T., & Ryberg, T. Emerging Digital Practices Supporting Student-Centered Learning Environments in Higher Education: A Review of Literature and Lessons Learned from the Covid-19 Pandemic. Education and Information Technologies 2024, 29, 1673–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, A. , Tsusaka, T. W., Nguyen, T. P. L., & Ahmad, M. M. Assessment of vulnerability and resilience of school education to climate-induced hazards: a review. Development Studies Research. [CrossRef]

- Peng, H. , Ma, S., & Spector, J. M. Personalized adaptive learning: an emerging pedagogical approach enabled by a smart learning environment. Smart Learning Environments 2019, 6, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins-Porras, L. (2023). The Impact of Stress Among Undergraduate Students: Supporting Resilience and Wellbeing Early in Career Progression. In The Palgrave Handbook of Occupational Stress (pp. 347–372). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Polat, M. Readiness, resilience, and engagement: Analyzing the core building blocks of online education. Education and Information Technologies 2024, 29, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pro Futuro. (2023, July 28). Digital resilience: a superpower to address digital dangers, 28 July.

- Qi, C. , & Yang, N. (2024a). Digital resilience and technological stress in adolescents: A mixed-methods study of factors and interventions. Education and Information Technologies, 9067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, C. , & Yang, N. (2024b). Digital resilience and technological stress in adolescents: A mixed-methods study of factors and interventions. Education and Information Technologies, 9067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quraishi, T., U. H., M. A., H. I. M., & O. M. R. Empowering students through digital literacy: A case study of successful integration in a higher education curriculum. Journal of Digital Learning and Distance Education 2024, 2, 667–681. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Monsivais, C. L. , Rodríguez-Cano, S., Lema-Moreira, E., & Delgado-Benito, V. Relationship between mental health and students’ academic performance through a literature review. Discover Psychology 2024, 4, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyaz Ahmad Bhat. The Impact of Technology Integration on Student Learning Outcomes: A Comparative Study. International Journal of Social Science, Educational, Economics, Agriculture Research and Technology (IJSET) 2023, 2, 592–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, M. P. , & Chiappe, A. Artificial Intelligence and Digital Ecosystems in Education: A Review. Technology, Knowledge and Learning 2024, 29, 2153–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, P. M. , Scanes, E., & Locke, W. (2023). Stress adaptation and resilience of academics in higher education. Asia Pacific Education Review. [CrossRef]

- Ruzic-Dimitrijevic, L. , & D. J. The risk management in higher education institutions. Online Journal of Applied Knowledge Management 2014, 2, 137–152. [Google Scholar]

- Saastamoinen, U. , Eronen, L., Juvonen, A., & Vahimaa, P. Wellbeing at the 21st century innovative learning environment called learning ground. Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning 2023, 16, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shandilya, S. K. , Datta, A., Kartik, Y., & Nagar, A. (2024). Achieving Digital Resilience with Cybersecurity. [CrossRef]

- Shaya, N. , Abukhait, R., Madani, R., & Khattak, M. N. Organizational Resilience of Higher Education Institutions: An Empirical Study during Covid-19 Pandemic. Higher Education Policy 2023, 36, 529–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoulidas, N. , Alexopoulos, N., & Raptis, N. Higher Education Students’ Perceptions of Risk and Crisis Management in Universities. European Journal of Education and Pedagogy 2024, 5, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowell, J. Making Learning Inclusive in Digital Learning Environments. In English Teaching Forum 2023, 61, 2–13. [Google Scholar]

- Spante, M. , Hashemi, S. S., Lundin, M., & Algers, A. Digital competence and digital literacy in higher education research: Systematic review of concept use. Cogent Education 2018, 5, 1519143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukup, L. , & C. R. Examing the Effects of Resilience on Stress and Academic Performance in Business Undergraduate College Students. College Student Journal 2021, 55, 293–304. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, W. J. (2021). Educational Institution Safety and Security. In Encyclopedia of Security and Emergency Management (pp. 243–252). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y. , & Liu, L. Structural equation modeling of university students’ academic resilience academic well-being, personality and educational attainment in online classes with Tencent Meeting application in China: investigating the role of student engagement. BMC Psychology 2023, 11, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H. , Arslan, O., Xing, W., & Kamali-Arslantas, T. Exploring collaborative problem solving in virtual laboratories: a perspective of socially shared metacognition. Journal of Computing in Higher Education 2023, 35, 296–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Education Hub. (n.d.). How to help students improve their resilience, 2019.

- The relationship between digital literacy and academic performance of college students in blended learning: the mediating effect of learning adaptability. Advances in Educational Technology and Psychology 2023, 7. [CrossRef]

- Timotheou, S. , Miliou, O., Dimitriadis, Y., Sobrino, S. V., Giannoutsou, N., Cachia, R., Monés, A. M., & Ioannou, A. Impacts of digital technologies on education and factors influencing schools’ digital capacity and transformation: A literature review. Education and Information Technologies 2023, 28, 6695–6726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tondeur, J. , Howard, S., Carvalho, A. A., Kral, M., Petko, D., Ganesh, L. T., Røkenes, F. M., Starkey, L., Bower, M., Redmond, P., & Andresen, B. B. The DTALE Model: Designing Digital and Physical Spaces for Integrated Learning Environments. Technology, Knowledge and Learning 2024, 29, 1767–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tondeur, J. , Howard, S., Van Zanten, M., Gorissen, P., Van der Neut, I., Uerz, D., & Kral, M. The HeDiCom framework: Higher Education teachers’ digital competencies for the future. Educational Technology Research and Development 2023, 71, 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishnu, S. , Tengli, M. B., Ramadas, S., Sathyan, A. R., & Bhatt, A. Bridging the Divide: Assessing Digital Infrastructure for Higher Education Online Learning. TechTrends 2024, 68, 1107–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, H. , & Ho, H. Online learning environment and student engagement: the mediating role of expectancy and task value beliefs. The Australian Educational Researcher 2024, 51, 2183–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. , Wang, Y., & Zhao, L. (2024). Effects of Psychological Resilience on Online Learning Performance and Satisfaction Among Undergraduates: The Mediating Role of Academic Burnout. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher. [CrossRef]

- Wedyaswari, M. , Grace Lusiani Larasati Simanjuntak, J., Hanafitri, A., & Witriani. Resilience process in Bidikmisi students: understanding risk, protective and promotive factor, and resilient outcome. Cogent Education. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z. Navigating Digital Learning Landscapes: Unveiling the Interplay Between Learning Behaviors, Digital Literacy, and Educational Outcomes. Journal of the Knowledge Economy 2023, 15, 10516–10546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzheng Wu, L. Y. The relationship between digital literacy and academic performance of college students in blended learning: the mediating effect of learning adaptability. Advances in Educational Technology and Psychology 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widowati, A. , Siswanto, I., & Wakid, M. Factors Affecting Students’ Academic Performance: Self Efficacy, Digital Literacy, and Academic Engagement Effects. International Journal of Instruction 2023, 16, 885–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikiversity. (2021). Academic resilience: What is academic resilience, why does it matter, and how can it be enhanced? 2021.

- Wollscheid, S. , Scholkmann, A., Capasso, M., & Olsen, D. S. (2023). Digital Transformations in Higher Education in Result of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Findings from a Scoping Review. In Digital Transformations in Nordic Higher Education (pp. 217–242). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Wong, Z. Y. , & Liem, G. A. D. Student Engagement: Current State of the Construct, Conceptual Refinement, and Future Research Directions. Educational Psychology Review 2022, 34, 107–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Education. (2022, April 29). Putting Digital Literacy and Digital Resilience into Frame, 29 April.

- Worldbank. (2024, October 30). Ensuring Learning Continuity During Crises: Applying Lessons from the COVID-19 Pandemic to Shape Resilience and Adaptability, 30 October 2024.

- Wright, N. (2018). Framing Learning Spaces: Modern Learning Environments and ‘Modern’ Pedagogy. In Becoming an Innovative Learning Environment (pp. 21–45). Springer Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X. , Li, Z., Hin Hong, W. C., Xu, X., & Zhang, Y. Effects and side effects of personal learning environments and personalized learning in formal education. Education and Information Technologies 2024, 29, 20729–20756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S. , & Wang, W. (2022). The Role of Academic Resilience, Motivational Intensity and Their Relationship in EFL Learners’ Academic Achievement. Frontiers in Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Ye, W. , Strietholt, R., & Blömeke, S. Academic resilience: underlying norms and validity of definitions. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability 2021, 33, 169–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z. (2022a). Sustaining Student Roles, Digital Literacy, Learning Achievements, and Motivation in Online Learning Environments during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability, 4388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z. (2022b). Sustaining Student Roles, Digital Literacy, Learning Achievements, and Motivation in Online Learning Environments during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability, 4388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X. , Rehman, S., Altalbe, A., Rehman, E., & Shahiman, M. A. Digital literacy as a catalyst for academic confidence: exploring the interplay between academic self-efficacy and academic procrastination among medical students. BMC Medical Education 2024, 24, 1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajda, J. (2021). Creating Effective Learning Environments in Schools Globally. [CrossRef]

- Zayed, A. M. Digital Resilience, Digital Stress, and Social Support as Predictors of Academic Well-Being among University Students. Journal of Education and Training Studies 2024, 12, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S. , Rehman, S., Zhao, Y., Rehman, E., & Yaqoob, B. Exploring the interplay of academic stress, motivation, emotional intelligence, and mindfulness in higher education: a longitudinal cross-lagged panel model approach. BMC Psychology 2024, 12, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J. , Cheung, K., & Sit, P. Identifying key features of resilient students in digital reading: Insights from a machine learning approach. Education and Information Technologies 2024, 29, 2277–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X. , Smith, C. J. M., & Al-Samarraie, H. Digital technology adaptation and initiatives: a systematic review of teaching and learning during COVID-19. Journal of Computing in Higher Education 2024, 36, 813–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S. , Li, J., Bai, J., Yang, H. H., & Zhang, D. (2023). Assessing Secondary Students’ Digital Literacy Using an Evidence-Centered Game Design Approach. [CrossRef]

- Zone of Education. (n.d.). Innovative teaching strategies to enhance students’ learning.

| Variable | Code | Indicator | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Risk Management | RM1 | Identification of potential risks in learning environments | (Galiutinova & Pervushina, 2021; Gerardo & Fajar, 2022; Sullivan, 2021) |

| RM2 | Development of contingency plans to mitigate risks | ||

| RM3 | Implementation of security measures to protect data | ||

| RM4 | Evaluation of risk management effectiveness | ||

| RM5 | Integration of risk management strategies into institutional policies | ||

| RM6 | Provision of clear communication about risks to stakeholders | ||

| RM7 | Continuous improvement of risk management practices | ||

| Digital Technology Literacy | DTL1 | Ability to use digital tools for learning | (Audrin & Audrin, 2022; Getenet et al., 2024; Nguyen & Habók, 2024) |

| DTL2 | Evaluation of information credibility in digital platforms | ||

| DTL3 | Effective collaboration using digital technologies | ||

| DTL4 | Adaptation to new learning technologies | ||

| DTL5 | Problem-solving using digital resources | ||

| DTL6 | Confidence in using digital tools for academic purposes | ||

| Modern Learning Environment | MLE1 | Access to reliable digital infrastructure | (Grierson, 2017; Saastamoinen et al., 2023; Wright, 2018; Zajda, 2021) |

| MLE2 | Availability of user-friendly learning platforms | ||

| MLE3 | Quality of internet connectivity for learning | ||

| MLE4 | Integration of interactive tools in learning | ||

| MLE5 | Personalization of learning experiences | ||

| MLE6 | Use of collaborative platforms for group learning | ||

| MLE7 | Support from instructors in using digital platforms | ||

| MLE8 | Flexibility in learning schedules enabled by technology | ||

| MLE9 | Use of virtual labs and simulations | ||

| MLE10 | Provision of learning analytics tools | ||

| MLE11 | Inclusivity of the learning environment | ||

| MLE12 | Continuous improvement of learning platforms | ||

| Student Resilience | SR1 | Ability to recover from academic setbacks | (J. Lin & Zhan, 2024; Yang & Wang, 2022; Zhang et al., 2024) |

| SR2 | Maintenance of motivation under pressure | ||

| SR3 | Effective coping with stress in academic settings | ||

| SR4 | Adaptation to changing academic demands | ||

| SR5 | Proactive problem-solving in challenging situations | ||

| SR6 | Perseverance in achieving academic goals |

| Variable | Indicator (Code) | Outer Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha (CA) | Composite Reliability (CR) | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk Management | RM1 | 0.584 | 0.780 | 0.841 | 0.583 |

| RM2 | 0.651 | ||||

| RM3 | 0.645 | ||||

| RM4 | 0.630 | ||||

| RM5 | 0.649 | ||||

| RM6 | 0.733 | ||||

| RM7 | 0.697 | ||||

| Digital Technology Literacy | DTL1 | 0.755 | 0.832 | 0.877 | 0.543 |

| DTL2 | 0.751 | ||||

| DTL3 | 0.678 | ||||

| DTL4 | 0.720 | ||||

| DTL5 | 0.737 | ||||

| DTL6 | 0.777 | ||||

| Modern Learning Environment | MLE1 | 0.674 | 0.889 | 0.908 | 0.620 |

| MLE2 | 0.699 | ||||

| MLE3 | 0.709 | ||||

| MLE4 | 0.593 | ||||

| MLE5 | 0.694 | ||||

| MLE6 | 0.655 | ||||

| MLE7 | 0.671 | ||||

| MLE8 | 0.745 | ||||

| MLE9 | 0.658 | ||||

| MLE10 | 0.690 | ||||

| MLE11 | 0.677 | ||||

| MLE12 | 0.575 | ||||

| Student Resilience | SR1 | 0.725 | 0.853 | 0.891 | 0.577 |

| SR2 | 0.783 | ||||

| SR3 | 0.758 | ||||

| SR4 | 0.786 | ||||

| SR5 | 0.766 | ||||

| SR6 | 0.739 |

| Endogenous Variable | R² Value | Interpretation |

| Student Resilience | 0.546 | 54.6% of the variability in student resilience is explained by risk management, digital technology literacy, and modern learning environment. |

| Hypothesis | Path Coefficient (β) | t-Statistics | p-Value | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: Risk Management → Student Resilience | 0.220 | 3.932 | 0.000 | Accepted (positive and significant) |

| H2: Digital Technology Literacy → Student Resilience | 0.214 | 4.253 | 0.000 | Accepted (positive and significant) |

| H3: Moderation of Modern Learning Environment on the relationship between Risk Management → Student Resilience | 0.407 | 8.556 | 0.000 | Accepted (significantly strengthens the relationship) |

| H4: Moderation of Modern Learning Environment on the relationship between Digital Technology Literacy → Student Resilience | 0.015 | 5.129 | 0.000 | Accepted (significantly strengthens the relationship) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).