1. Introduction

Metal-hydride hydrogen storage systems based on magnesium alloys are currently being intensively studied and are considered as most promising ones for use in practical applications of hydrogen energy [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. This interest is primarily due to high mass content of hydrogen in magnesium hydride (7.6%), as well as its availability and cheapness. The main purpose of the ongoing research is to increase the kinetics of sorption/desorption processes, lower their operating temperature, enthalpy of phase transitions, and energy costs for activation. There are two approaches to solving these problems: powder and film. The powder approach consists in reducing the dispersion of the powder and using special technologies for its activation [

10,

11]. In the film approach, thin films applied in various ways are used instead of bulk powders [

12,

13,

14]. This work relates to the film approach. Earlier studies of film structures have shown the possibility of significant decrease in temperature and increase in kinetics of sorption/desorption processes:

- -

when using a nanoscale Mg/Ni sandwich-like structure, in which Ni film (4 nm thick) served to protect against oxidation, to dissociate H

2 molecules, and as a catalyst for hydrogenation of Mg film (340 nm thick) [

19];

- -

when using multilayer nanoscale Mg85Ni14Ce1 film structures (with total thickness of 50-500 nm) with a protective layer of Pd (10 nm thick) [

13];

- -

when using multilayer nanoscale Mg/Fe films (with total thickness of 300-800 nm) with a 10 nm thick protective Pd coating [

20].

Our studies of micro–sized Mg/Ni sandwich-like film structures (~5 µm Mg and 200 – 400 nm Ni) also showed possibility of achieving the sufficiently high sorption/desorption characteristics of hydrogen, but on significantly thicker films [

17]. At sorption pressure of ~ 5 atm and desorption under vacuum conditions, the mass content of hydrogen in such films was ~ 5.4 wt. % (without significant fluctuations during subsequent sorption cycles) with decrease in temperature peaks of desorption to 150 – 200°C and reduction in desorption time to ~ 20 min. The results of subsequent studies of microscale Ni-Mg-Ni-Mg film structures (5 layers of Mg 1.3 – 1.8 µm thick and 6 layers of Ni 0.25 – 0.35 µm thick) deposited on a polyimide substrate (12.5 µm thick) showed possibility of saturating such film structures to 7.0 – 7.5 wt. % hydrogen at pressures up to 30 atm and temperatures 200 – 250°С with reversible amount of stored hydrogen up to 3.4 wt. % when desorbed at pressure of 1 atm and temperatures of 200 – 250°С with phase-formation enthalpy in the range of 19.8 − 46.7 kJ/mol H

2 depending on the nickel content (nickel layer thickness) [

18]. These exciting results motivated us to conduct studies of multilayer Ni-Mg-Ni-Mg film structures with increased number of layers, move from small-sized to long-length samples, and develop a prototype of film metal-hydride hydrogen accumulator on this basis.

The paper describes the results of studies of the characteristics of multilayer Ni-Mg-Ni-Mg film structures (38/37 Ni/Mg layers with a total thickness up to 45 µm) deposited on both small-sized and extended (up to 40 m) polyimide substrates. The developed design of a prototype of film metal-hydride hydrogen accumulator and the results of its tests are presented. Specific energy characteristics of the prototype accumulator and possibility of increasing them when scaling the prototype are discussed.

2. Materials and Methods

ПМ-1ЭУ polyimide film 12.5 µm thick was used as a substrate. The preliminary preparation of the substrates before deposition of film structures on them was carried out according to the procedure described in [

18]. Ni-Mg-Ni-Mg film structures were deposited on the same equipment and under the same technological conditions as in [

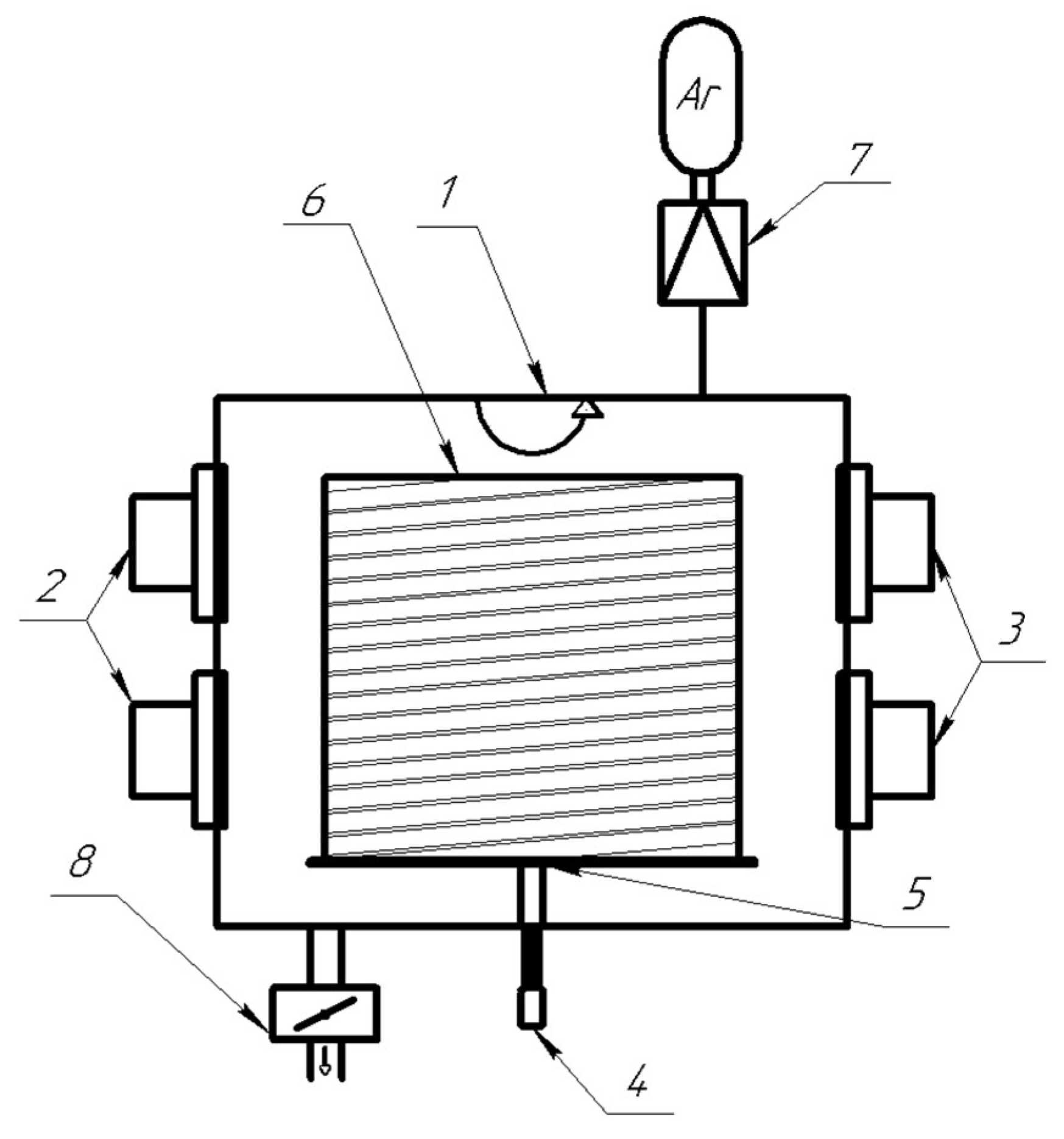

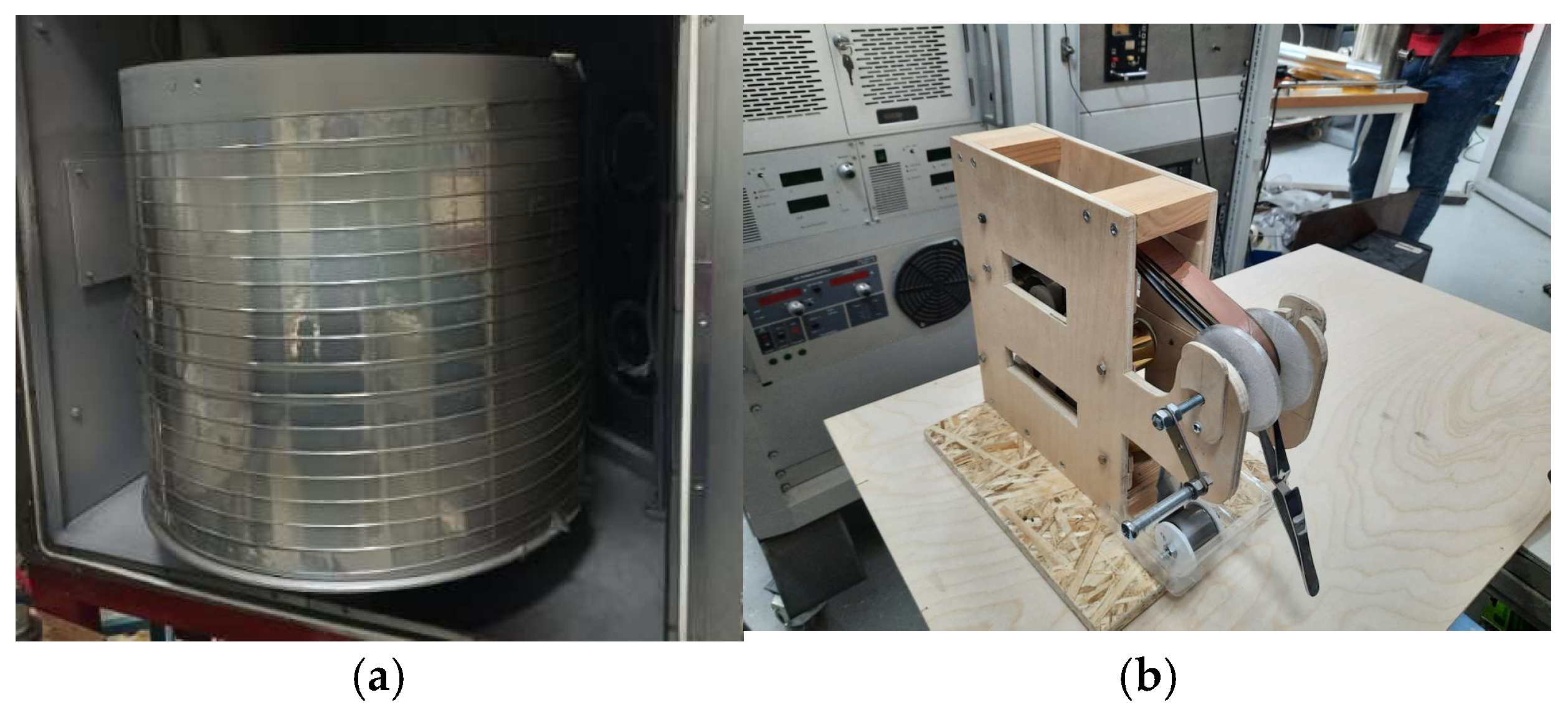

18]. The difference was the use of four magnetron sputtering systems (two magnetrons with magnesium cathodes and two magnetrons with nickel cathodes) and a large rotating drum with a wound polyimide film substrate mounted in the center of the chamber (

Figure 1).

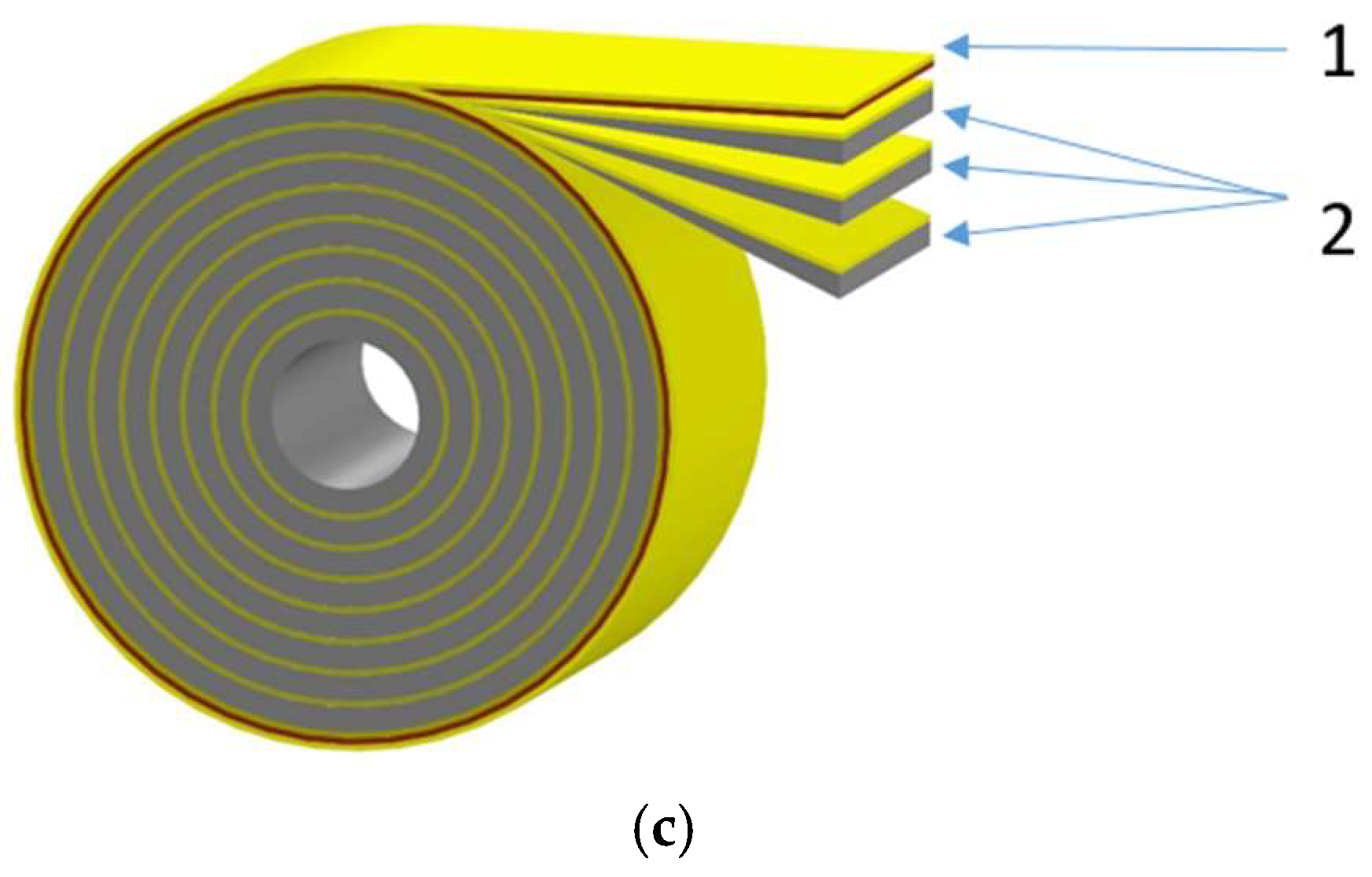

The distance between the axes of each pair of the magnetrons was 28 cm. Drum dimensions (diameter 64 cm, height 55 cm) made it possible to place up to 40 m of polyimide film with a width of 25 mm. The drum was rotated by an asynchronous motor. The distance from the magnetron target surface to the drum was 17 cm which ensured nonuniformity of deposited film not exceeding 15%. 37 Mg and 38 Ni layers with a total thickness of 40 – 45 µm were deposited layer by layer on the polyimide tape substrate. The thickness of Mg layers was in the range of 0.9 – 1.2 µm, and the thickness of Ni layers was in the range of 0.1 – 0.2 µm. The total deposition time of such Ni-Mg-Ni-Mg film structures on 40 m polyimide tape was about 33 h. The thicknesses of Mg and Ni cathodes were insufficient for one-time continuous deposition of such film structure. Therefore, after cathodes wearing the next Ni layer was deposited on the polyimide tape, and then vacuum chamber was opened to replace the cathodes. The Ni layer protected the Mg film from air oxidation. For subsequent studies, the finished tape with Ni-Mg-Ni-Mg film structure deposited in this way was cut into samples of the required size. The studies were carried out with both small-sized (20 × 20 mm) and long-length (5 m and 40 m) samples. Long-length samples with Ni-Mg-Ni-Mg film structure deposited on the polyimide tape were wound onto a cylindrical metal shell together with the polyimide tape of the same length with a resistive layer (copper, ~1 µm thick) previously deposited on it. This made it possible to produce their uniform heating for sorption and desorption processes when current was passed through the resistive layer.

Saturation of the samples with hydrogen (purity >99.999%) was carried out by the Sievers method on AKNDM automated complex of JSC “NIIEFA” (pressure up to 50 atm, temperature up to 950°C). Thermal desorption analysis of saturated samples was also carried out here. The internal dimensions of the measuring chamber of the complex (diameter 20 mm and length 20 mm) made it possible to test only small-sized samples. In this regard, long–length samples with a resistive layer (wound on the cylindrical shell) were installed in the separate thermally insulated chamber, which was connected to the gas path of the AKNDM complex and equipped with its own pressure sensor (1-30 atm) and a thermocouple. Studies of long-length samples were carried out in this chamber with their heating by passing current through a resistive layer. The amount of desorbed hydrogen was determined using ideal gas law.

Desorption was carried out in the pressure range from ~1 Pa to ~1 atm. At pressure increase, a gas portion was regularly discharged into a buffer volume, which was then evacuated to the pressure of ~1 Pa. The error in pressure determining was: in the pressure range 1∙10-5…1 atm: ±0.25% (ATOVAC ACM300 baratron), and in the pressure range 1…30 atm − ±0.5% (KELLER 9FLD piezometric sensor), the error in temperature determining was ±2°С. The complex was calibrated using a standard LaNi5 powder sample and allowed to determine the mass content of hydrogen with accuracy of at least ± 10%.

The microstructure of the films was studied using a Phenom 3G ProX scanning electron microscope equipped with an energy dispersion spectrum analysis device.

X-ray diffraction analysis (XRD) before and after hydrogen saturation was performed using a DRON-8 diffractometer equipped with a Mythen 2R linear position-sensitive detector. Diffraction patterns were recorded at the following parameters: angle range of 2θ – 20…100°; scanning speed – 1°/min; scanning step – 0.1°; exposure time at the point – 3 s; voltage – 40 kV; current – 20 mA. Diffraction pattern analysis and phase identification were performed using the COD database and the DrWin program.

To determine the absolute hydrogen content in the films, LECO RHEN602 analyzer was used, which provides an accuracy of 2% of the measured value. Saturated or desorbed Ni-Mg-Ni-Mg films were separated from the substrate and placed in the crucible of the device. The data obtained was averaged over the results of five measurements.

3. Results

Investigations of small-sized samples of periodic Ni-Mg-Ni-Mg film structures:

Table 1 presents the list of small-sized samples showing the compositions and parameters of the films deposited by the magnetron sputtering (38 Ni layers and 37 Mg layers).

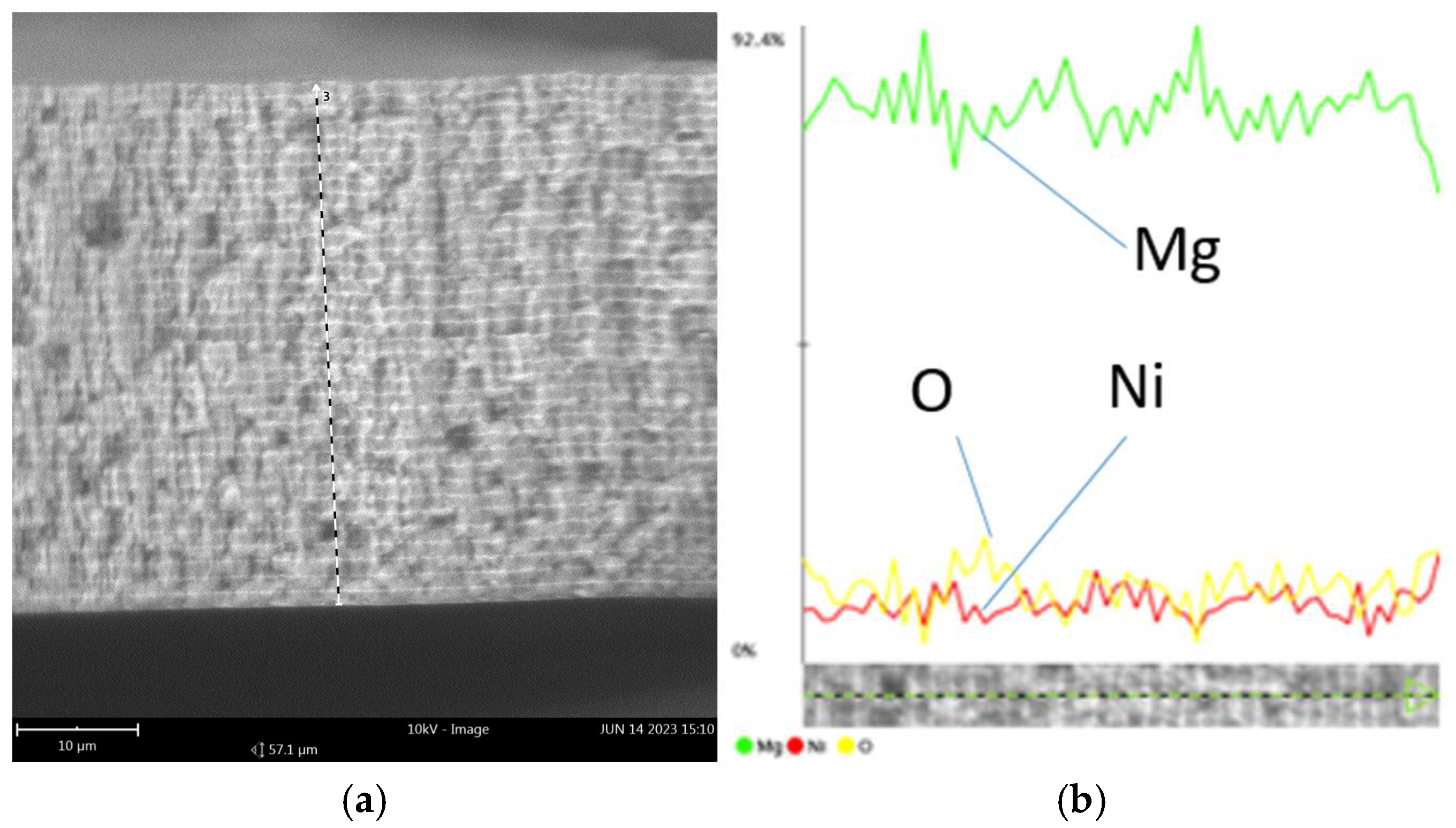

Figure 2 shows the sample of the microstructure of the deposited films (Mg/Ni5 sample).

The scanning electron microscope (SEM) image clearly shows the multilayer structure of the deposited films. All samples contain oxygen (from 2 to 5 at. %) due to the fact that the samples were at atmospheric pressure when prepared for the investigations and due to the high activity of Mg.

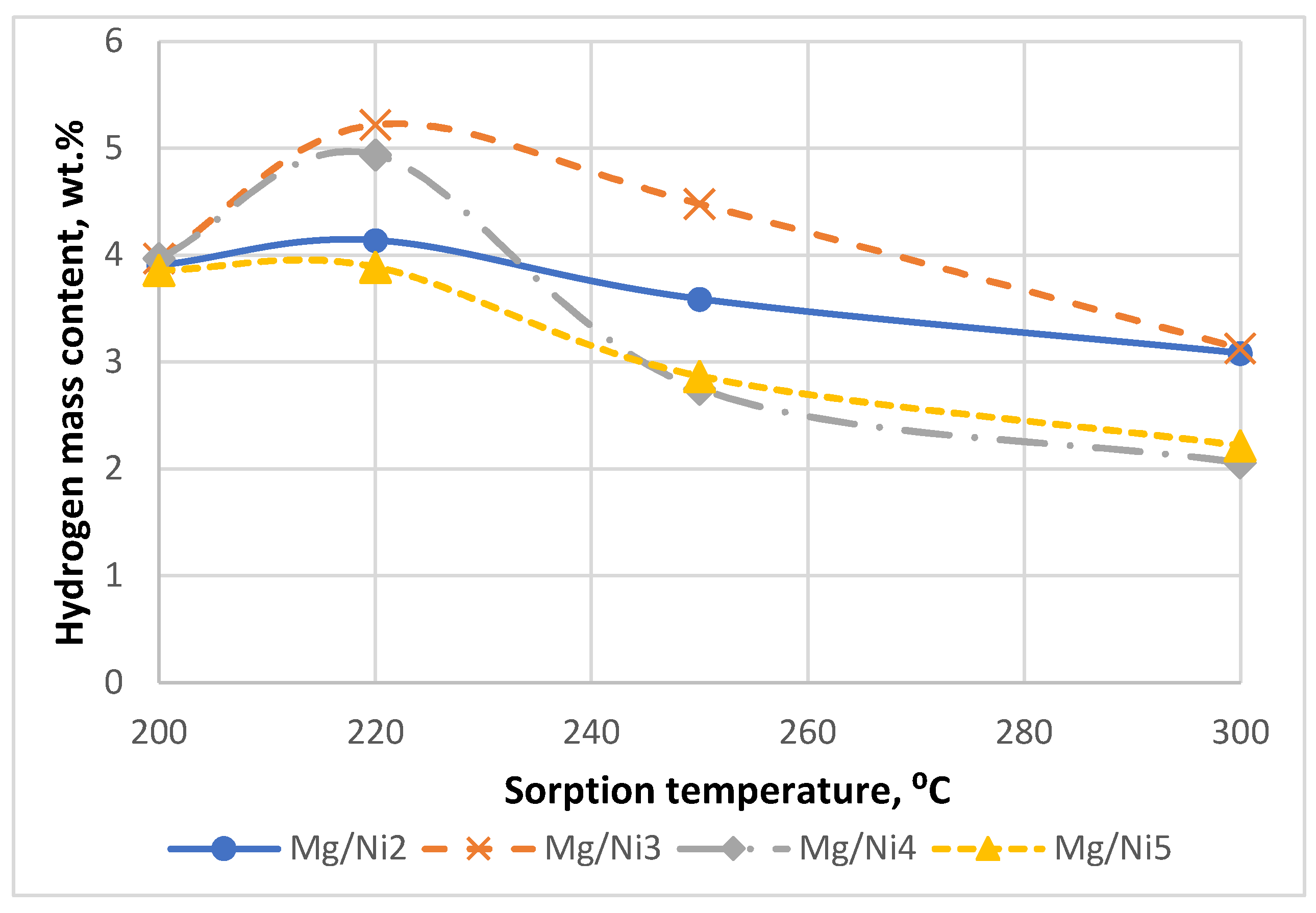

Figure 3 shows the dependence of the hydrogen mass content (specified by an analyzer of hydrogen absolute content) on the saturation temperature (at saturation pressure of 20 atm and holding for 4 h).

As can be seen from

Figure 3, the optimum saturation temperature at pressure of 20 atm is 220С. The maximum content of hydrogen after the first sorption/desorption cycle was 5.2 wt. %.

Three sorption/desorption cycles were carried out with Mg/Ni2 and Mg/Ni3 samples (sorption: temperature 220°С, pressure 20 atm, time 2 h; desorption: temperature 250°С, pressure 1 Pa, time 4 h) with determining the mass content of hydrogen on the LECO analyzer.

Table 2 presents the values of hydrogen mass content in the samples averaged over five measurements after the first and third sorption cycles.

The obtained results show the significant influence of activation (the number of performed sorption/desorption cycles) on the amount of hydrogen stored in the film.

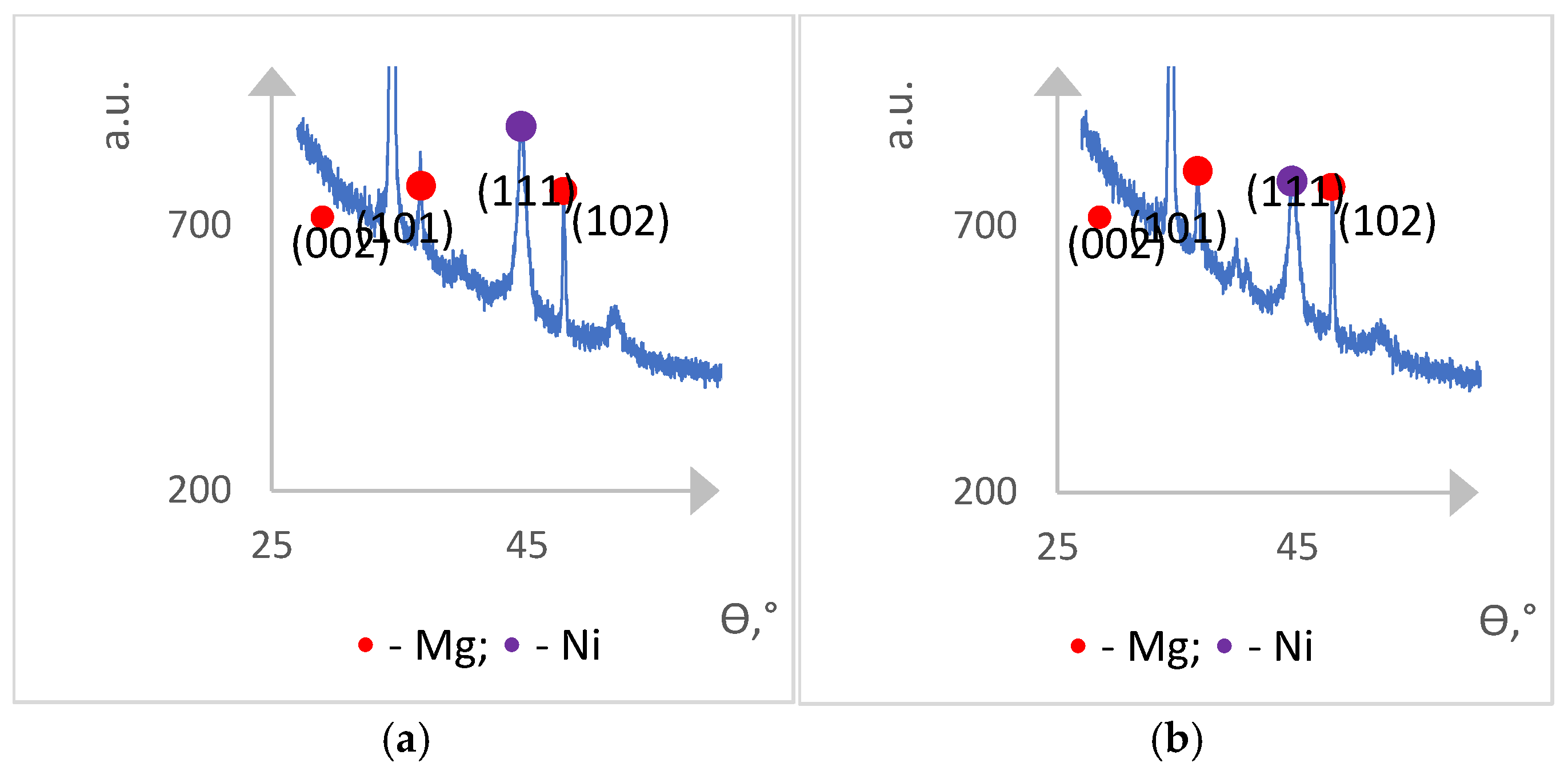

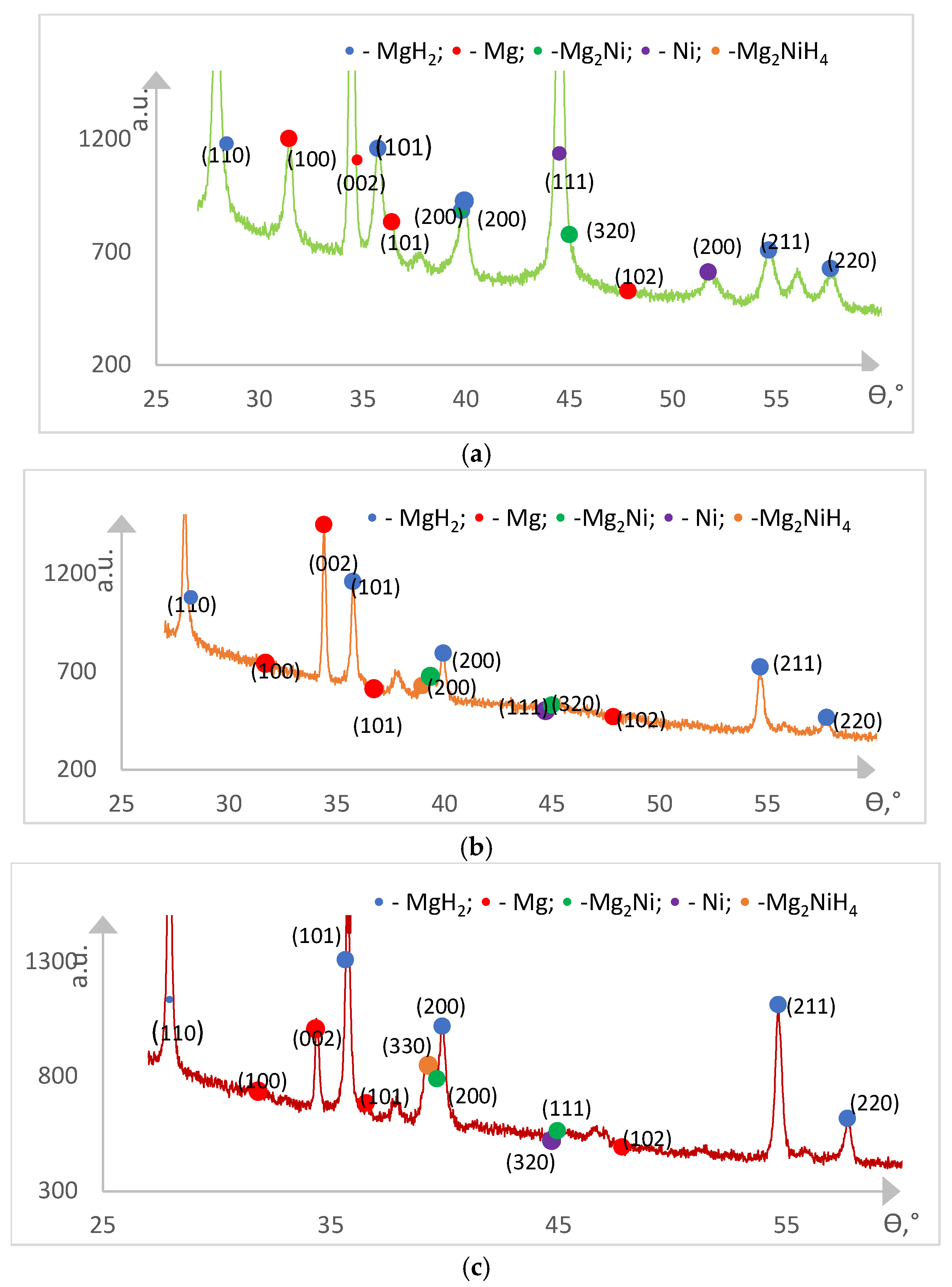

Figure 4 shows the results of the X-ray diffraction analysis of the Mg/Ni1 and Mg/Ni4 hydrogen unsaturated samples.

Only Mg and Ni phases are found on the diagrams, and no Mg2Ni intermetallide phases were observed.

Then the Mg/Ni1 and Mg/Ni4 samples were saturated with hydrogen at 5 sorption/desorption cycles (sorption: temperature 220°С, pressure 20 atm, time 2 h; desorption: temperature 250°С, pressure 1 Pa, time 4 h).

Figure 5 shows X-ray diffraction analysis results for the hydrogen saturated Mg/Ni1 samples after the first, third and fifth sorption cycles (X-ray diffraction analysis results for the Mg/Ni4 samples are similar).

As a result of hydrogen saturation of the samples, the MgH

2, Mg

2Ni and Mg

2NiH

4 phases appear.

Table 3 presents mass fractions for the phase composition of the saturated samples after the first, third and fifth sorption cycles.

The fraction of hydride MgH2 and Mg2NiH4 phases in the samples increases rapidly as far as the number of sorption/desorption cycles increases and achieves in total ~98% at the fifth sorption cycle. Meanwhile, the fraction of Mg and Ni phases and the fraction of Mg2Ni intermetallide (formed at the first sorption cycle) decrease. The results obtained indicate the activation of hydride-forming material of the film as a result of successive sorption/desorption cycles with the achievement of its almost complete hydridization on the fifth cycle. In unsaturated Mg/Ni 1 and Mg/N 4 samples, according to the results of both XRD and SEM EDS studies, the mass fraction of Ni was 14.6 wt.% and 19.1 wt.%, respectively. It was not possible to understand what is the reason for the noticeably greater fraction of the Ni phase recorded in the samples after the first sorption cycle.

Investigations of the long-length (5 m) sample with multilayer Ni-Mg-Ni-Mg film structure deposited on the polyimide tape:

The concept of the film metal-hydride hydrogen accumulator [

18] assumes heating of the Ni-Mg-Ni-Mg film structure with the current passing through the resistive layer preliminary deposited on the polyimide tape. To check the efficiency of such approach, the long (5 m) Mg/Ni6 sample was manufactured with the same quantity of Mg and Ni layers on the polyimide film as for the small-sized samples (37 Mg and 38 Ni layers). The total thickness of the hydride-formation film structure was 44.8 µm with the weight of 11.25 g and Mg/Ni ratio of 92/8 at. %. To heat this sample, the polyimide film of the same length was prepared with the resistive layer deposited on it by magnetron sputtering (copper ~1 µm thick). The long Mg/Ni6 sample together with the tape of resistive heating were wound on a hollow roll and loaded in the test chamber connected with the AKNDM complex where hydrogen saturation and desorption were carried out. Saturation was carried out in the temperature range 160-246°C, pressure 20 atm and exposure time 4 hours, desorption was carried out in the temperature range 275-305°C in the pressure range 0.2 - 1.7 atm (at initial and final pressure ~ 1 Pa with periodic discharge of the released gas into the buffer volume at pressures exceeding 1 atm, until almost complete hydrogen release) for 2 – 4 h. The volume of the buffer volume was 2.4 l. Nine sequential sorption/desorption cycles were performed with step-by-step determination of the mass fraction for released hydrogen.

Table 4 presents the experimental results.

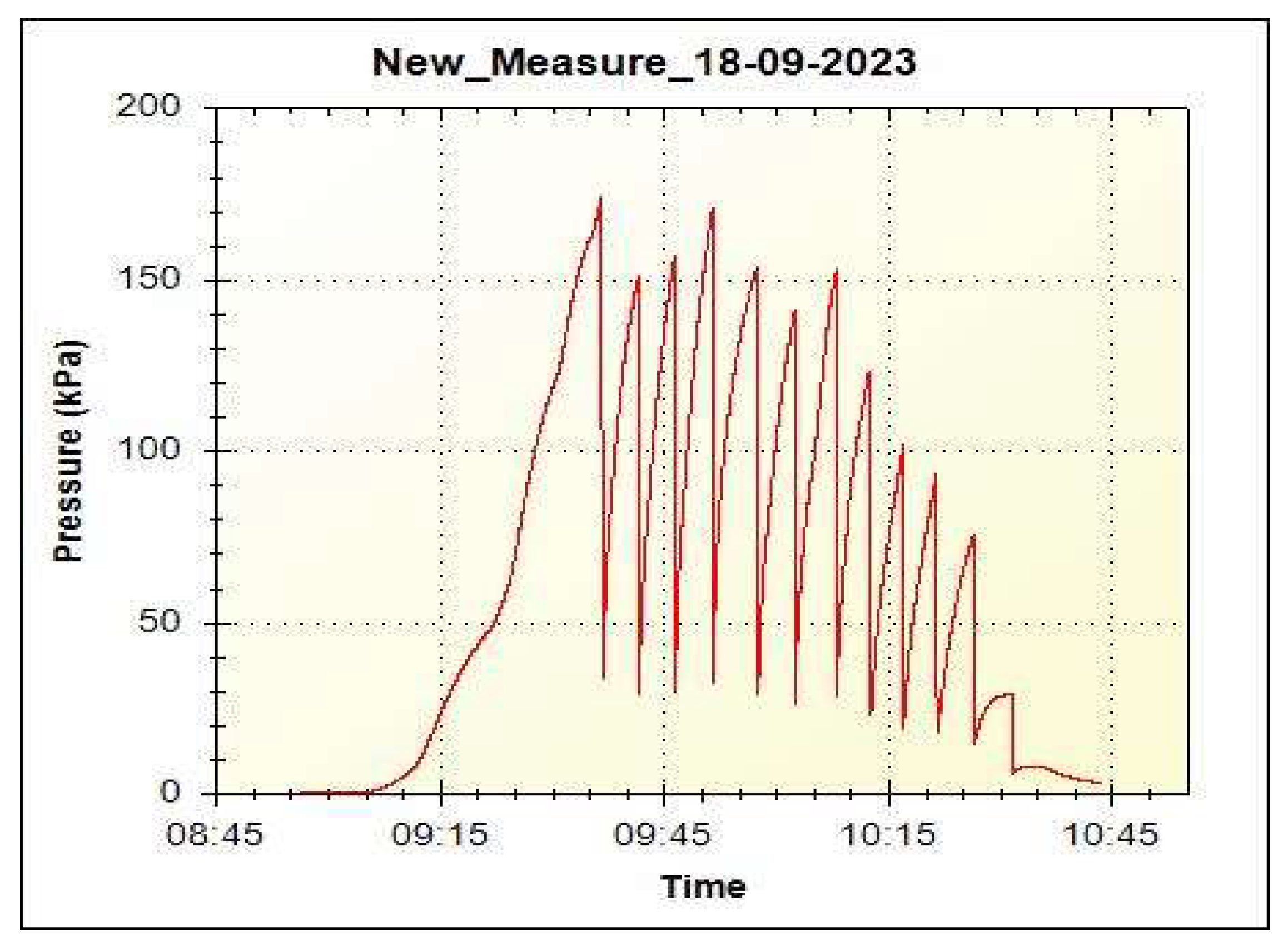

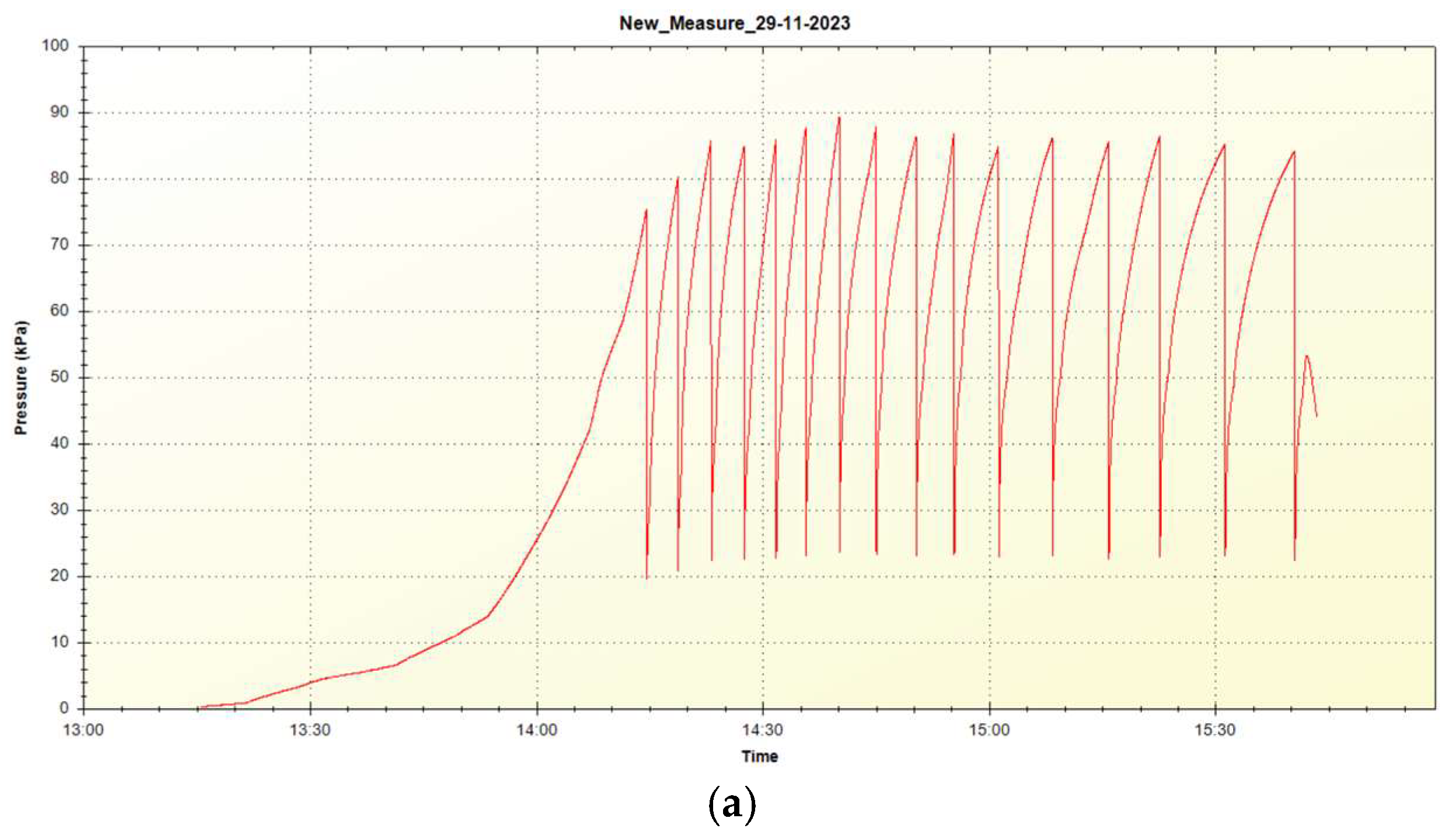

Figure 6 shows the pressure diagram for the eighth desorption cycle.

To accelerate the completion of the desorption process, the pressure was discharged until achievement of the plateau. As can be seen from

Figure 6, gas pressure before its discharge into the buffer volume is above 1 atm up to the 9th cycle, which may indicate the possibility of hydrogen release in such storage systems at operating pressures of more than 1 atm. The mass fraction of the released hydrogen for 9 cycles of its discharge was 4.4 wt.%, for all 12 cycles of discharge 5.1 wt.%.

The experimental results for the Mg/Ni6 sample have shown the operability of the long Ni-Mg-Ni-Mg film structure with the film resistive heater as a hydrogen accumulator. The film structure is activated to the eighth sorption/desorption cycle with the values of hydrogen mass content similar to those for the small-sized samples activated to the third sorption/desorption cycle.

Investigations of the long-length (40 m) sample with multilayer Ni-Mg-Ni-Mg film structure deposited on the polyimide tape:

Similar to the Mg/Ni6 sample, the Mg/Ni7 sample was manufactured consisting of eight tapes 5 m long each and containing in total 40 m of hydride-forming film structure. Eight tapes with hydride-forming material and the tape with the resistive layer were wound in parallel on the hollow roll which then was mounted in the testing facility.

Figure 7 shows the parallel tape winding device and winding diagram. The total weight of the hydride-forming material was 80.1 g. The resistance of the resistive layer was 0.6 Ohm.

During the tests, all sorption cycles were carried out at the temperature of 220°С and pressure of 20 atm. When the pressure decreased, hydrogen was introduced to maintain it. The holding time was from 1 to 8 h. The desorption cycles were carried out in the conditions similar to those for the Mg/Ni6 sample, but at the temperature of 250°С. The desorption temperature was reduced to the minimum to determine its effect on the amount and time of hydrogen discharge. The volume of the buffer volume was 2.4 l.

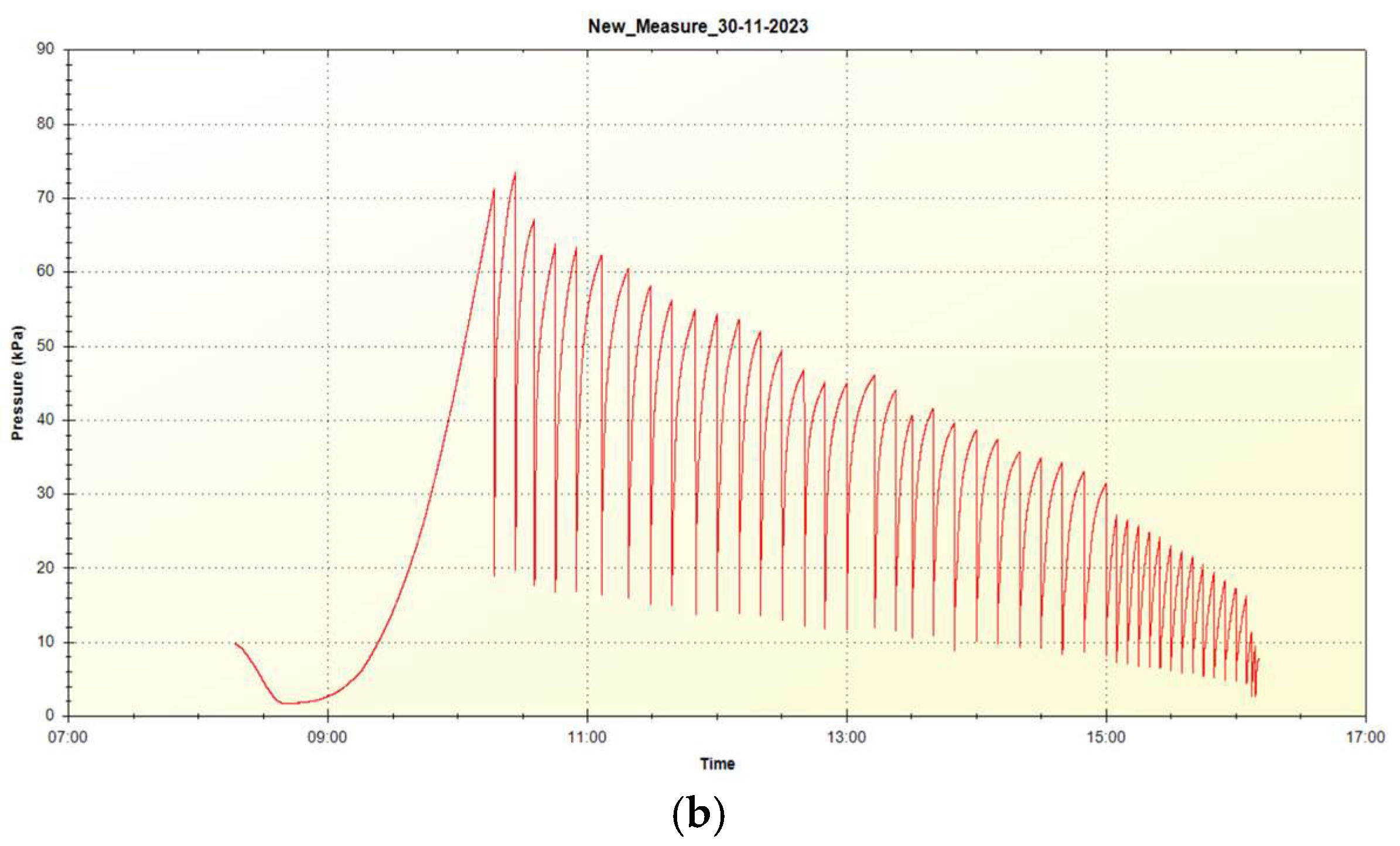

Table 5 presents the test results for the Mg/Ni7 sample.

Figure 8 shows pressure diagrams at the sorption and desorption within the fourth test cycle. For the fourth test cycle, the desorption was performed (due to its duration) with a stop and pause, therefore in

Figure 8 (b), the initial pressure increase is visible at the start of heating.

Development of a prototype of film metal-hydride hydrogen accumulator:

The results obtained on the high reversible amount of stored hydrogen during testing of the Mg/Ni7 sample were the motivation for the development of a prototype of a film metal-hydride hydrogen accumulator.

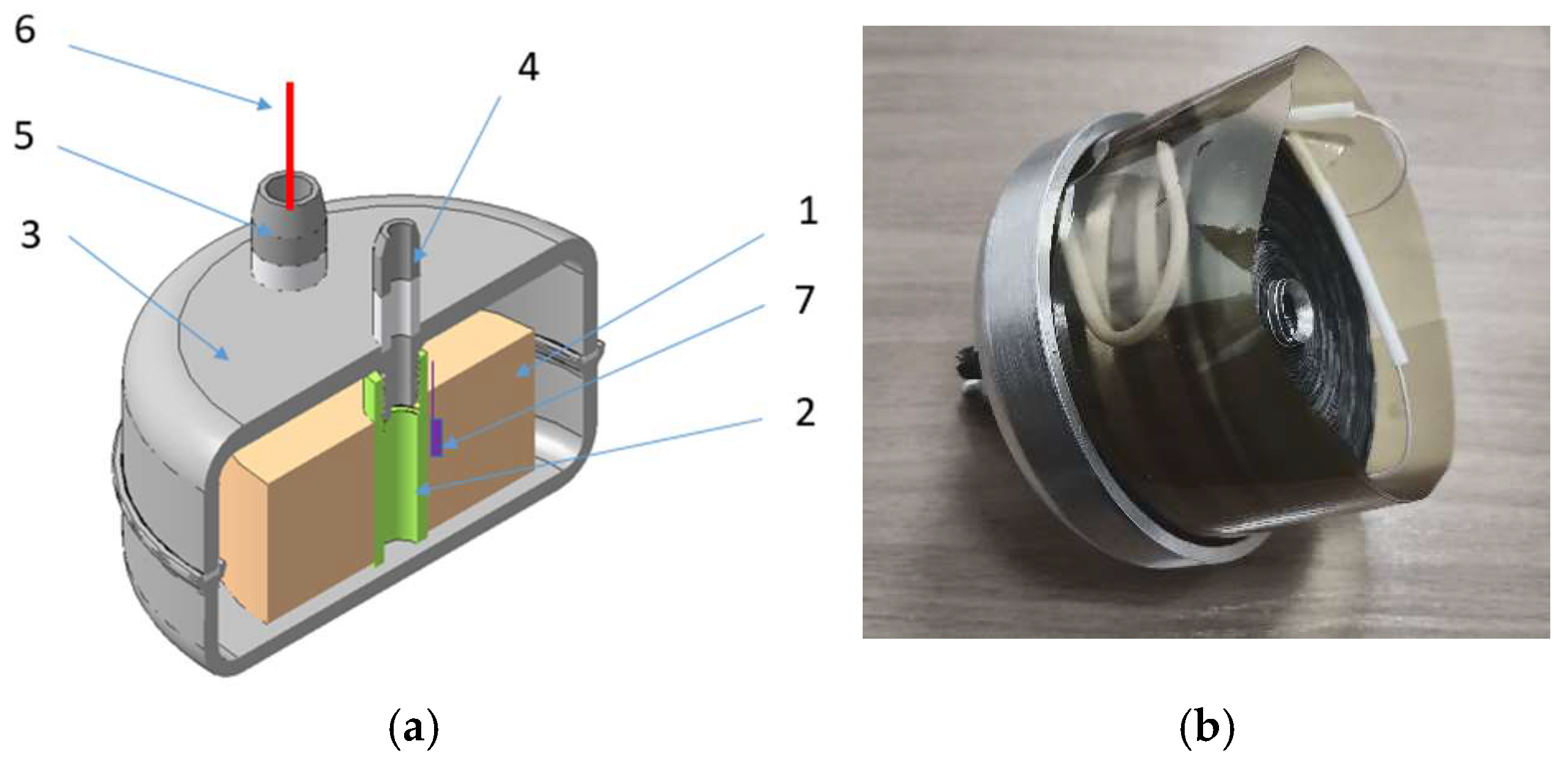

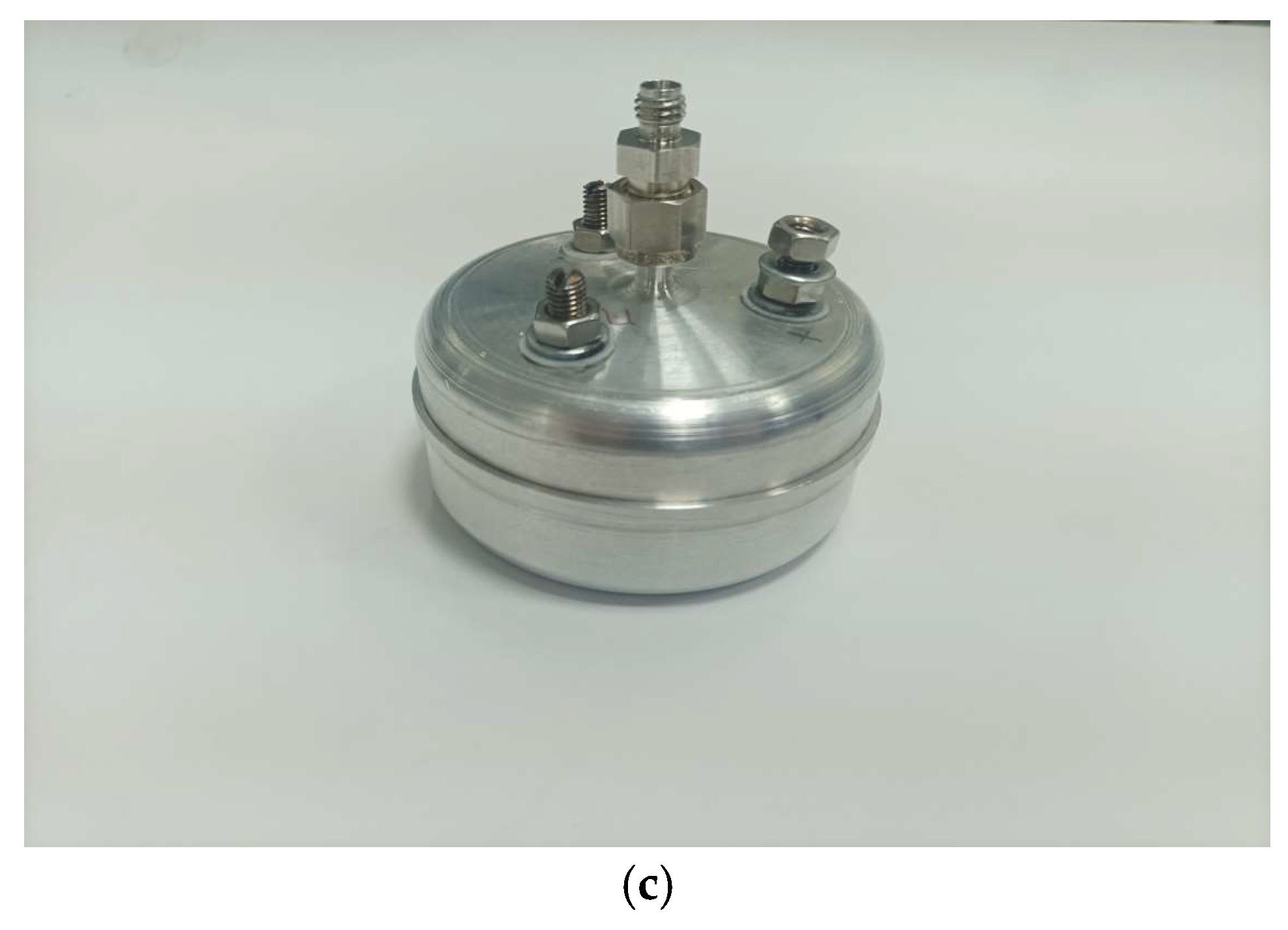

Figure 9 shows the diagram of the developed accumulator prototype. The polyimide tape with the deposited resistive layer and hydride-forming material forms a carrier (polyimide – resist – hydride-forming material). The required amount of carrier is wound on the hollow roll (serving as one of heating circuit electrodes). Then the hollow roll with carrier winding is mounted in the accumulator case, and the second heating circuit electrode and temperature sensors are mounted (thermocouple or thermal resistance).

The developed case of the accumulator prototype is optimized with respect to weight and consists of two weldable (by laser welding) sections – cover and semi-case. Three vacuum electrical inputs and a gas pipe are welded into the cover. On the inside of the cover there is a mounting surface with a thread to fix the hollow roll with the wound carrier. When the hollow roll with the wound carrier is fixed in the cover and the heating electrodes and temperature sensor are connected with the welded electrical inputs, the cover is assembled to the semi-case, and their laser welding is performed.

Weldable aluminum АМг6 alloy was selected as a case material which has sufficiently high mechanical properties (tensile strength up to 340 MPa, yield strength of 285 – 315 MPa). As a result of strength analysis in extreme operating conditions (excessive pressure of 30 atm, case temperature of 200°С), the wall thickness for the cylindrical cell of the case was selected to be 2 mm and for the end surfaces – 4 mm.

Weight, volume and energy characteristics of the film hydrogen accumulator prototype: hydride-forming material weight – 80.1 g, carrier winding weight (polyimide film with the deposited resistive layer and hydride-forming material) – 100 g, weight of the aluminum case with welded electrical inputs, inner electrodes, gas pipe and fitting – 250 g, assembled accumulator prototype weight – 350 g, specific gravimetric energy consumption – 400 W*h/kg (3.6 g of stored hydrogen), outer volume of the case – 0.22 l, specific volumetric energy consumption – 630 W*h/l.

4. Discussion

The experimental results for the small-sized samples have shown that the multilayer Ni-Mg-Ni-Mg films (38 layers of Ni and 37 layers of Mg) can be saturated with the high mass percents of hydrogen in the same manner as the similar films with a small number of layers (6 layers of Ni and 5 layers of Mg) [

18]. The experimentally specified optimum sorption temperature (according to the maximum hydrogen content) was 220°С at the pressure of 20 atm for all samples. The pattern was established between the growth of hydrogen mass content in the multilayer films and increasing the number of sorption/desorption cycles performed which was accompanied by the increase in MgH

2 and Mg

2NiH

4 hydride phases. At the fifth sorption cycle the hydride phases totally reached ~98 wt. %. This pattern allows us to assume the successive step-by-step growth of film hydrogenation along its thickness from one sorption/desorption cycle to another until reaching the plateau of complete hydrogenation. When the hydride phases are formed in the part of hydride-formation material at the n-th sorption cycle, the hydride phases are certainly formed in the same part of the material at the (n+1)-th sorption cycle with their formation having the better kinetics. This is also confirmed by long-term cycle tests (20 sorption/desorption cycles): when an amount of sorbed/desorbed hydrogen reached the plateau, its amount was constant within the statistical error in the subsequent cycles. It is interesting to note the appearance of a noticeable amount of Mg

2Ni intermetallide phase (which was absent before the sorption process) in the multilayer Ni-Mg-Ni-Mg film structure at the first sorption cycle with almost complete transition to the Mg

2NiH

4 hydride phase during subsequent cycles.

Testing of the five-meter sample of multilayer Ni-Mg-Ni-Mg film structure together with a resistive layer applied to a polyimide tape of the same length (sample Mg/Ni6) showed the operability of such a heating system for a carrier with hydride-forming film material. During all sorption/desorption cycles the ohmic resistance of the resistive film was stable. The mass content of hydrogen in 5 m film winding was 4.9 wt. % after the ninth sorption cycle that corresponded to its mass content in the small-sized Mg/Ni2 sample after the third sorption cycle. During the desorption processes, the pressure was relieved before reaching equilibrium pressure. In other words, the equilibrium pressure at the desorption processes was always higher than the pressure at the gas relieve. When hydrogen content in the sample decreases (from one pressure relieve to another), the equilibrium pressure also decreases. A tendency can be observed in

Figure 6 for gas relieve pressure reduction from 1.7 atm at its first relieve to 1 atm at its nineth relieve and to 0.3 atm at its twelfth relieve. Thus, it can be claimed that the equilibrium pressure of the multilayer film structures of the Mg/Ni6 sample exceeds 1 atm at the residual fraction of hydrogen 5.1 – 4.4 = 0.7 wt. %, and the fraction of reversibly stored hydrogen at the desorption pressure of ~1 atm is 4.4 wt. %.

Testing of 40 m multilayer Ni-Mg-Ni-Mg film structure with the resistive layer (by the scheme: eight 5 m tapes with the deposited hydride-forming material and one tape with the deposited resistive layer) have shown the similar results: increase in the mass fraction of stored hydrogen from 1.1 wt. % at the first sorption cycle to 4.5 wt. % at its fifth cycle (the amount of stored hydrogen was 3.6 g at the weight of hydride-forming material of 80.1 g). During these tests, the possibility of reducing the desorption temperature to 250 ° C was demonstrated, but with significant increase in the desorption cycle time.

Based on the research results, the prototype of a film metal-hydride hydrogen accumulator with specific gravimetric energy consumption of 400 W*h/kg and specific volumetric energy consumption of 630 W*h/l was developed, manufactured and tested. It should be noted that the body weight of this prototype significantly exceeds the weight of the carrier (250 and 100 g, respectively). When scaling the film accumulator, this ratio will decrease, increasing the specific gravimetric energy consumption of the accumulator up to its maximum value of 1340 W*h/kg (the specific gravimetric energy consumption of the carrier itself). In addition, the ratio of the carrier volume to the internal volume of the case was 0.33 for this prototype. This small value is related to the imperfections in the manual winding mechanism and can be significantly increased with corresponding increase in the specific volumetric energy consumption up to 1900 W*h/l (the specific volumetric energy consumption of the carrier itself). It is also worth noting that the specific gravimetric energy capacity of modern electrochemical accumulators does not exceed 260 W*h/kg and their specific volumetric energy capacity does not exceed 350 W*h/l. This comparison may indicate the great energy potential of film metal-hydride hydrogen accumulators and the prospects of their use in industrial applications of hydrogen energy.

5. Conclusions

Multilayer films base on the Ni-Mg-Ni-Mg film structures up to 45 µm thick can be saturated with hydrogen up to 6.4 wt. % at the pressure up to 20 atm and temperature of 200 – 250°С. The mass content of hydrogen in multilayer films grows significantly with increase in the number of sorption/desorption cycles performed, which is accompanied by corresponding increase in the content of hydride phases MgH2 and Mg2NiH4 in them. The optimal temperature of hydrogen sorption determined from experiments (in terms of the maximum amount of hydrogen content) was 220°С, minimum temperature of hydrogen desorption was 250°С, but with sufficiently long time for its complete release (up to 8 h). For practical applications, desorption temperature of 300°С with total hydrogen release time of ~1 h is more appropriate.

Tests of long-length (5 m and 40 m) samples of multilayer film structures with a resistive layer have shown their operability as a metal-hydride hydrogen accumulator without arranging additional hydrogen inlet and outlet channels. The experiments have demonstrated that such long-length carries provide a reversible content of hydrogen exceeding 4 wt. % at the desorption pressure of ~1 atm.

Based on the conducted research, a prototype of film metal-hydride hydrogen accumulator was developed, manufactured and tested. With a stored amount of 3.6 g of hydrogen, the specific gravimetric energy consumption of the accumulator was 400 W*h/kg, and the specific volumetric energy consumption was 630 W*h/l. When scaling the accumulator prototype, the ratio of the mass and volume of the hydride-forming carrier to the mass and volume of the case will increase (in this prototype, these ratios were 0.40 and 0.33 respectively). Along with growth of this ratio, the specific energy characteristics of the accumulator will also increase, reaching the specific energy characteristics of its carrier: specific gravimetric energy consumption of 1340 W*h/kg and specific volumetric energy consumption of 1900 W*h/l.

Author Contributions

D.A. Karpov: organization of the workflow, analysis of experimental results and preparation of the article; A.G. Ivanov: study of the microstructure of samples and analysis of experimental results; E.S. Chebukov: sorption–desorption experiments; M.I. Yurchenkov: deposition of multilayer film structures, X-ray diffraction analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jain, I.P.; Lal, Chhagan; Jain, Ankur. Hydrogen storage in Mg: A most promising material. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy, 2010, 35, 5133–5144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellosta von Colbe, J.; Ares, J.-R.; Barale, J.; Baricco, M.; Buckley, C.; Capurso, G.; Gallandat, N.; Grant, D.M.; Guzik, M.N.; Jacob, I.; Jensen, E.H.; Jensen, T.; Jepsen, J.; Klassen, T.; Lototskyy, M.V.; Manickam, K.; Montone, A.; Puszkiell, J.; Sartori, S.; Sheppard, D.A.; Stuart, A.; Walker, G.; Webb, C.J.; Yang, H.; Yartys, V.; Zuttel, A.; Dornheim, M. Application of hydrides in hydrogen storage and compression: Achievements, outlook and perspectives. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 7780–7808. [Google Scholar]

- Novaković, J. G.; Novaković, N.; Kurko, S.; Govedarović, S. M.; Pantić, T.; Mamula, B. P.; Batalović, K.; Radaković, J.; Rmuš, J.; Shelyapina, M.; Skryabina, N.; de Rango, P. and Fruchart, D. Influence of defects on the stability and hydrogen-sorption behavior of Mg based hydrides. ChemPhysChem 2019, 20, 1216–1247. [Google Scholar]

- Korablov, D.; Bezdorozhev, O.; Yartys, V.; Solonin, Y. Mg-based composites as effective materials for storage and generation of hydrogen for FC applications. In HYDROGEN BASED ENERGY STORAGE: STATUS AND RECENT DEVELOPMENTS, November 2021, Publisher: Prostir-M, Editor: Volodymyr YARTYS; Yuriy SOLONIN; Ihor ZAVALIY, ISBN: 9786178055097.

- Sui, Y; Yuan, Z. ; Zhou, D; Zhai, T.; Li, X.; Feng, D.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y. Recent progress of nanotechnology in enhancing hydrogen storage performance of magnesium based materials: A review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 30546–30566. [Google Scholar]

- Pasquini, L.; Sakaki, K.; Akiba, E.; Allendorf, M.D.; Alvares, E.; Ares, J.-R.; Babai, D.; Baricco, M.; Bellosta von Colbe, J.; Bereznitsky, M.; Buckley, C.E.; Cho, Y.W.; Cuevas, F.; de Rango, P.; Dematteis, E.M.; Denys, R.V.; Dornheim, M.; Fernández, J.F.; Hariyadi, A.; Hauback, B.C.; Heo, T.W.; Hirscher, M.; Humphries, T.D.; Huot, J.; Jacob, I.; Jensen, T.R.; Jerabek, P.; Kang, S.Y.; Keilbart, N.; Kim, H.; Latroche, M.; Leardini, F.; Li, H.; Ling, S.; Lototskyy, M.V.; Mullen, R.; Orimo, S.-I.; Paskevicius, M.; Pistidda, C.; Polanski, M.; Puszkiel, J.; Rabkin, E.; Sahlberg, M.; Sartori, S.; Santhosh, A.; Sato, T.; Shneck, R.Z.; Sørby, M.H.; Shang, Y.; Stavila, V.; Suh, J.-Y.; Suwarno, S.; Thu, L.T.; Wan, L.F.; Webb, C.J.; Witman, M.; Wan, C.; Wood, B.C. and Yartys, V.A. Magnesium- and intermetallic alloys-based hydrides for energy storage: modelling, synthesis and properties. Prog. Energy 2022, 4, 032007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Lin, X. Surface modifications of magnesium-based materials for hydrogen storage and nickel–metal hydride batteries: A Review. Coatings 2023, 13, 1100–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jangir, M.; Jain, I.P.; Mirabile Gattia, D. Effect of Ti-based additives on the hydrogen storage properties of MgH2: A review. Hydrogen 2023, 4, 523–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Li, Y.; Yang, H.; Lu, Y.; Tan, J.; Li, J.; Li, Q.; Chen, Y.; Shaw, L. L.; Pan, F. Tailoring MgH2 for hydrogen storage through nanoengineering and catalysis. J. Magn. Alloys 2022, 10, 2946–2967. [Google Scholar]

- Klyamkin, S.N. Metal-hydride magnesium-based compositions as materials for hydrogen accumulation. Ross. Chim. Zhurnal 2006, 50, 49–55. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Shelyapina, M.G. Structure, Stability and Dynamics of Multi-Component Metal Hydrides According to the Data of the Theory of Density Functional and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. Dr. Sci, SPbGU, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 2018; pp. 91–160. (In Russian)

- Jain, I.P.; Vijay, Y.K.; Malhotra, L.K.; Uppadhyay, K.S. Hydrogen storage in thin film metal hydride – a review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 1988, 13, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Yu, S.; Wang, H.; Lu, Y.; Lin, H.-J. Nanosize effect on the hydrogen storage properties of Mg-based amorphous alloy. Scripta Mater. 2022, 216, 114736. [Google Scholar]

- Lider, A.; Kudiiarov, V.; Kashkarov, E.; Syrtanov, M.; Murashkina, T.; Lomygin, A.; Sakvin, I.; Karpov, D.; Ivanov, A. Hydrogen Accumulation and Distribution in Titanium Coatings at Gas-Phase Hydrogenation. Metals 2020, 10, 880–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldi, A.; Gonzalez-Silveira, M.; Palmisano, V.; Dam, B.; Griessen, R. Destabilization of the Mg-H system through elastic constraints. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 102, 226102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gharavi, A.G.; Akyildiz, H.; Öztürk, T. Thickness effects in hydrogen sorption of Mg/Pd thin films. J. Alloys Compd. 2013, 580 (Suppl. S1), S175–S178. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov, A.G.; Karpov, D.A.; Chebukov, E.S.; Yurchenkov, M.I. Research of hydrogen saturation of magnesium and magnesium-aluminum films and the influence of a protective nickel coating on it. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1954, 012014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, A.G.; Karpov, D.A.; Chebukov, E.S.; Yurchenkov, M.I. Investigation of Microscale Periodic Ni-Mg-Ni-Mg Film Structures as Metal-Hydride Hydrogen Accumulators. Hydrogen 2023, 4, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stillesjö, F.; Ólafsson, S.; Hjörvarsson, B.; Karlsson, E. Hydride Formation in Mg/Ni-Sandwiches Studied by Hydrogen Profiling and Volumetric Measurements. Z. Phys. Chem. 1993, 181, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Majid, N.A.; Watanabe, J.; Notomi, M. Improved desorption temperature of magnesium hydride via multi-layering Mg/Fe thin film. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 4181–4187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).