Submitted:

05 March 2025

Posted:

05 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

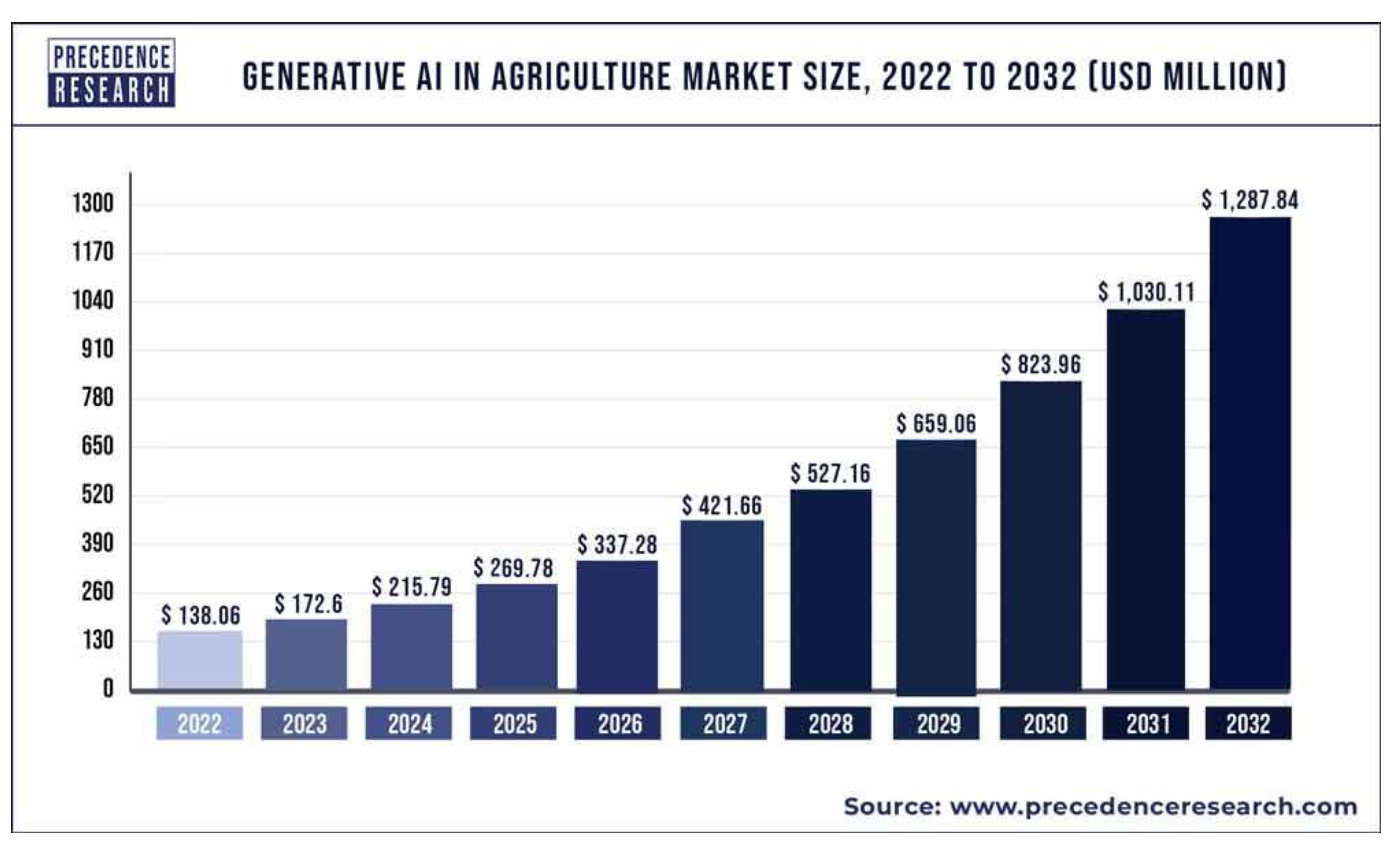

2. The Rise of AI in Agriculture: The Data-Driven Paradigm

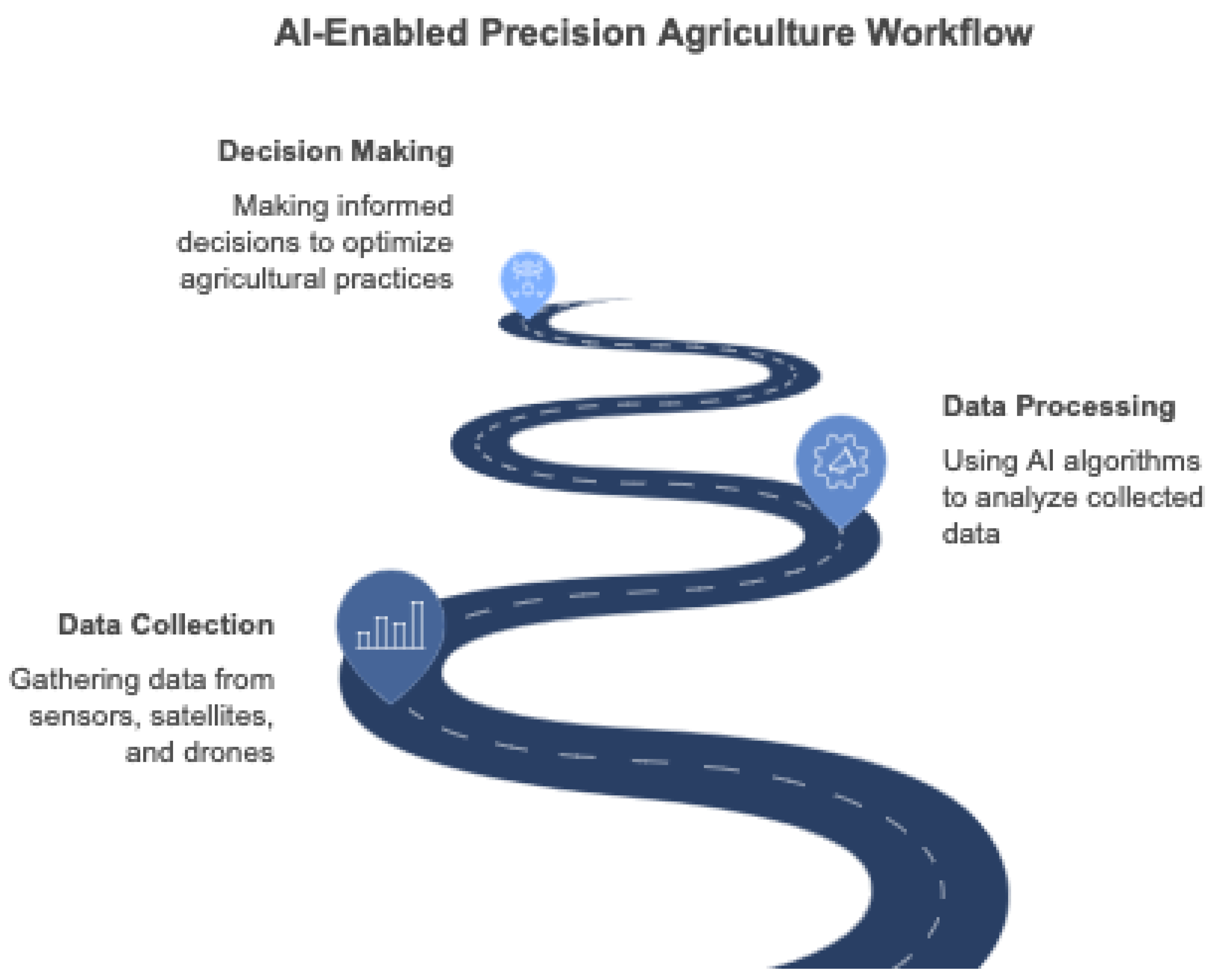

3. Transforming Agriculture: AI Applications in the Field

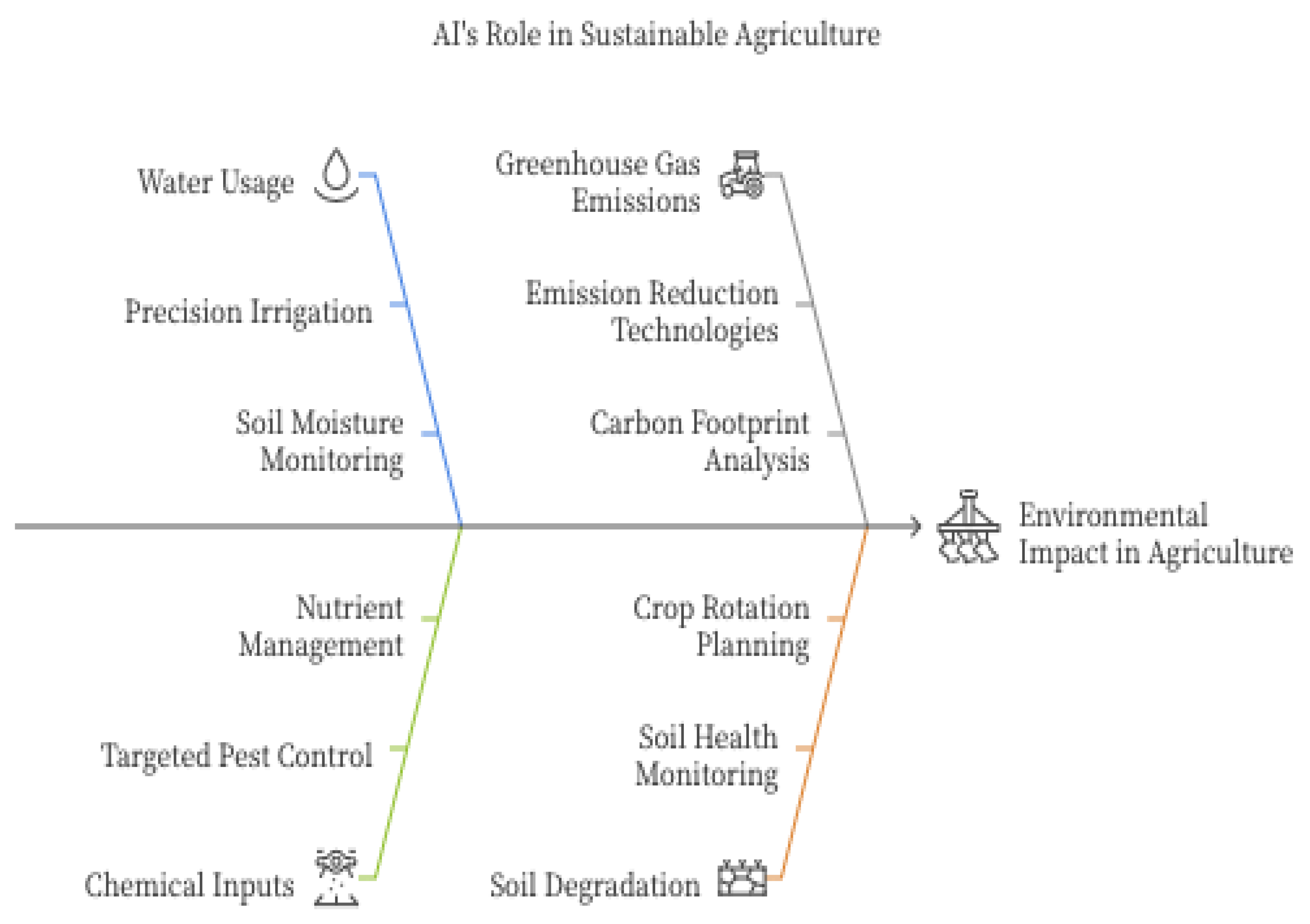

4. Beyond Technology: Economic, Environmental, and Social Impacts

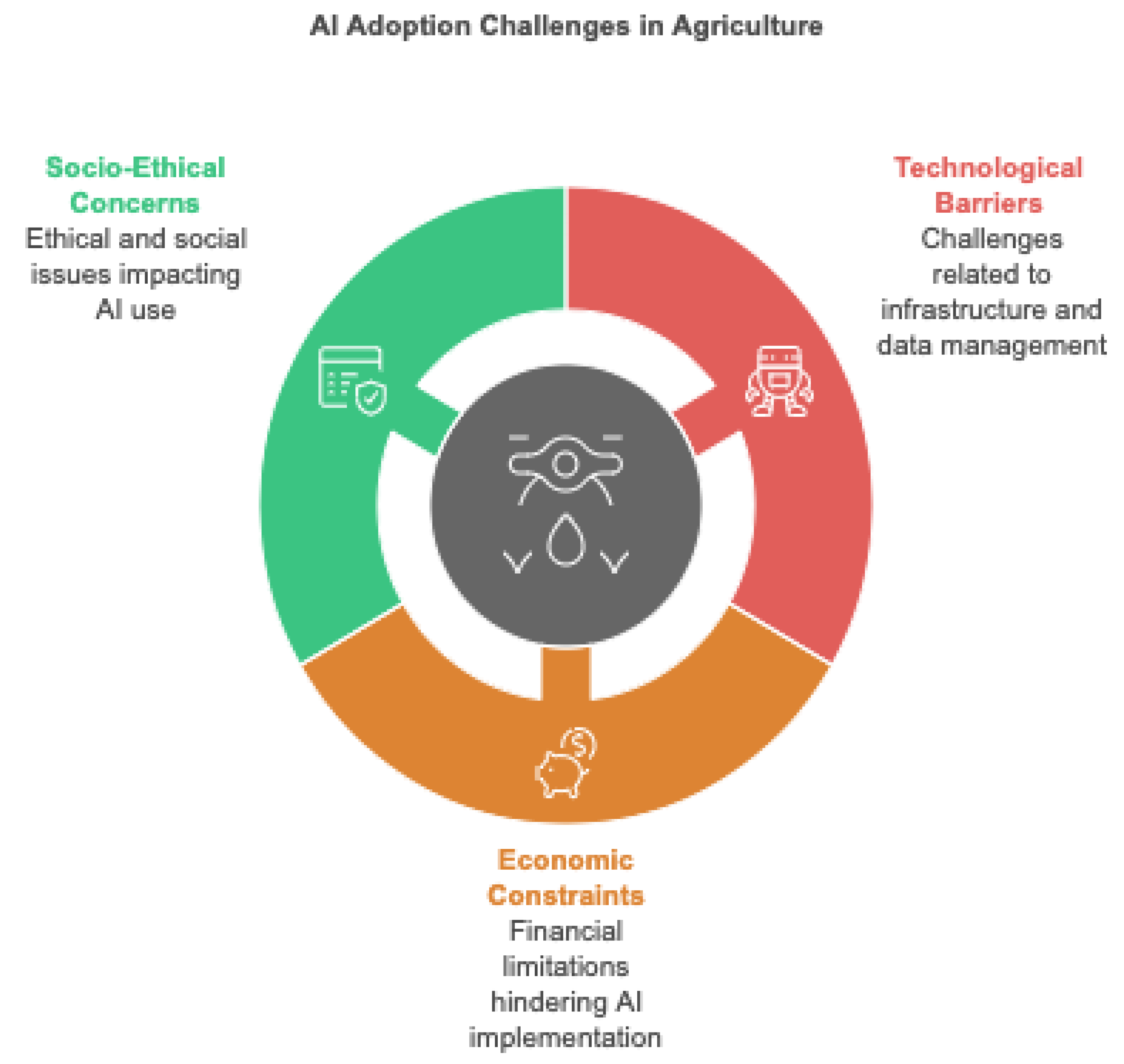

5. Navigating the Challenges: Roadblocks to Widespread AI Adoption

6. Charting the Course: A Strategic Vision for the Future

7. Conclusion: A Call for Collaborative, Responsible Innovation

References

- Altieri, M.A. Agroecology, small farms, and food sovereignty. Monthly Review 2009, 61, 102. [Google Scholar]

- Bac, C.W.; Hemming, J.; Van Henten, E.J. Harvesting robots for high-value crops: State-of-the-art review and challenges ahead. Journal of Field Robotics 2014, 31, 888–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechar, A.; Vigneault, C. Agricultural robots for field operations: Concepts and components. Biosystems Engineering 2016, 149, 94–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebber, D.P.; Ramotowski, M.A.; Gurr, S.J. Crop pests and pathogens move polewards in a warming world. Nature Climate Change 2013, 3, 985–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berckmans, D. Precision livestock farming technologies for welfare management in intensive livestock systems. Revue Scientifique et Technique 2014, 33, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, C.M. (2006). Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning. Springer.

- Bongiovanni, R.; Lowenberg-Deboer, J. Precision agriculture and sustainability. Precision Agriculture 2004, 5, 359–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronson, K. Smart farming: Including rights holders for responsible agricultural innovation. Technology Innovation Management Review 2018, 8, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronson, K.; Knezevic, I. Big Data in food and agriculture. Big Data & Society 2016, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonell, I.M. The ethics of big data in agriculture. Internet Policy Review 2016, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpio, C.E.; Isengildina-Massa, O. To tell or not to tell: Crop yield and weather information and market expectations. Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics 2009, 34, 276–297. [Google Scholar]

- Carrick, P.J.; Krüger, R. Restoring degraded landscapes in lowland Namaqualand: Lessons from the mining experience and from regional ecological dynamics. Journal of Arid Environments 2007, 70, 767–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CASP. (2018). Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Checklists. https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/.

- Chavas, J.P.; Nauges, C. Uncertainty, learning, and technology adoption in agriculture. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy 2020, 42, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; et al. An artificial intelligence model for crop yield prediction. Agricultural Systems 2019, 176, 102632. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Ba, T.; Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; Gong, X. Optimizing crop planning and water resource allocation for sustainable agricultural development. Agricultural Water Management 2021, 243, 106505. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. (2016). XGBoost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (pp. 785–794).

- Chlingaryan, A.; Sukkarieh, S.; Whelan, B. Machine learning approaches for crop yield prediction and nitrogen status estimation in precision agriculture: A review. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2018, 151, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colomina, I.; Molina, P. Unmanned aerial systems for photogrammetry and remote sensing: A review. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2014, 92, 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corke, P.; Winstanley, G.; Walker, R. (2004). Agriculture robotics: A stream mapping review. In Proceedings of the Australian Conference on Robotics and Automation.

- Creswell, A.; et al. Generative adversarial networks: An overview. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine 2018, 35, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossa, J.; et al. Genomic selection in plant breeding: Methods, models, and perspectives. Trends in Plant Science 2017, 22, 961–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doss, C.R.; Morris, M.L. How does gender affect the adoption of agricultural innovations? The case of improved maize technology in Ghana. Agricultural Economics 2001, 25, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckett, T.; Pearson, S.; Blackmore, S.; Grieve, B. Agricultural robotics: The future of robotic agriculture. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1806.06762. [Google Scholar]

- Eastwood, C.; Klerkx, L.; Ayre, M.; Dela Rue, B. Managing socio-ethical challenges in the development of smart farming: From a fragmented to a comprehensive approach for responsible innovation. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics 2017, 32, 741–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastwood, C.; et al. Making sense in the cloud: Farm advisory services in a smart farming future. NJAS-Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences 2019, 90–91, 100298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission (2019) Ethics guidelines for trustworthy, A.I. High-Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence.

- FAO. (2011). The State of the World's Land and Water Resources for Food and Agriculture (SOLAW). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- FAO. (2017). Information and Communication Technology (ICT) in Agriculture. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Ferris, S.; et al. (2014). Linking smallholder farmers to markets and the implications for extension and advisory services. MEAS Discussion Paper, 4.

- Fleming, A.; et al. Is big data for big farming or for everyone? Perceptions in the Australian grains industry. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 2018, 38, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, P.; Yu, J. Soil fertility and precision agriculture. International Journal of Agricultural and Biological Engineering 2008, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Gers, F.A.; Schmidhuber, J.; Cummins, F. Learning to forget: Continual prediction with LSTM. Neural Computation 2000, 12, 2451–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebbers, R.; Adamchuk, V.I. Precision agriculture and food security. Science 2010, 327, 828–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godwin, R.J.; et al. Precision farming of cereal crops: A review of a six-year experiment to develop management guidelines. Biosystems Engineering 2003, 84, 375–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.; et al. Generative adversarial nets. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2014, 27, 2672–2680. [Google Scholar]

- Grigorescu, S.; Trasnea, B.; Cocias, T.; Macesanu, G. A survey of deep learning techniques for autonomous driving. Journal of Field Robotics 2020, 37, 362–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, P.A.; Pérez-Ortiz, M.; Sánchez-Monedero, J.; Fernández-Navarro, F.; Hervás-Martínez, C. Ordinal regression methods: Survey and experimental study. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 2016, 28, 127–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashem, I.A.T.; et al. The rise of "big data" on cloud computing: Review and open research issues. Information Systems 2015, 47, 98–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Friedman, J. (2009). The Elements of Statistical Learning. Springer.

- Holzworth, D.P.; et al. APSIM–evolution towards a new generation of agricultural systems simulation. Environmental Modelling & Software 2014, 62, 327–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Hoffmann, W.C.; Lan, Y.; Wu, W.; Fritz, B.K. Development of a low-cost agricultural remote sensing system based on an autonomous unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV). Transactions of the ASABE 2010, 52, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. (2014). Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Cambridge University Press.

- Jayaraman, P.P.; Yavari, A.; Georgakopoulos, D.; Morshed, A.; Zaslavsky, A. Internet of things platform for smart farming: Experiences and lessons learnt. Sensors 2016, 16, 1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.H.; Resop, J.P.; Mueller, N.D.; et al. Random forests for global and regional crop yield predictions. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0156571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.; et al. Random forest algorithm for modeling global rice yield predictions using satellite imagery and climate data. Remote Sensing 2018, 10, 395. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Li, C.; Paterson, A.H. High throughput phenotyping of cotton plant height using depth images under field conditions. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2020, 168, 105107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolliffe, I.T. (2002). Principal Component Analysis. Springer.

- Jordan, M.I.; Mitchell, T.M. Machine learning: Trends, perspectives, and prospects. Science 2015, 349, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamilaris, A.; Kartakoullis, A.; Prenafeta-Boldú, F.X. A review on the practice of big data analysis in agriculture. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2017, 143, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaki, S.; Wang, L. Crop yield prediction using deep neural networks. Frontiers in Plant Science 2019, 10, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2012, 25, 1097–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kshetri, N. The emerging role of big data in key development issues: Opportunities, challenges, and concerns. Big Data & Society 2014, 1, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Soil carbon management and climate change. Carbon Management 2013, 4, 439–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Soil health and carbon management. Food and Energy Security 2016, 5, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesk, C.; Rowhani, P.; Ramankutty, N. Influence of extreme weather disasters on global crop production. Nature 2016, 529, 84–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liakos, K.G.; Busato, P.; Moshou, D.; Pearson, S.; Bochtis, D. Machine learning in agriculture: A review. Sensors 2018, 18, 2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobell, D.B.; Field, C.B. Global scale climate–crop yield relationships and the impacts of recent warming. Environmental Research Letters 2007, 2, 014002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobell, D.B.; Schlenker, W.; Costa-Roberts, J. Climate trends and global crop production since 1980. Science 2011, 333, 616–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobell, D.B.; et al. Prioritizing Climate Change Adaptation Needs for Food Security in 2030. Science 2008, 319, 5863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowder, S.K.; Skoet, J.; Raney, T. The number, size, and distribution of farms, smallholder farms, and family farms worldwide. World Development 2016, 87, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; et al. Recent advances of hyperspectral imaging technology and applications in agriculture. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makanza, R.; et al. High-throughput phenotyping of canopy cover and senescence in maize field trials using aerial digital canopy imaging. Remote Sensing 2018, 10, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayr, M.; Koppensteiner, G.; Schmidhuber, M. (2019). Reinforcement learning for autonomous greenhouse management. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (pp. 4925–4931).

- McKinsey Global Institute. (2018). Harvesting technology for agriculture's future. McKinsey & Company.

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLOS Medicine 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, S.P.; Hughes, D.P.; Salathé, M. Using deep learning for image-based plant disease detection. Frontiers in Plant Science 2016, 7, 1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, D.R. Soil erosion and agricultural sustainability. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2007, 104, 13268–13272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulla, D.J. Twenty-five years of remote sensing in precision agriculture: Key advances and remaining knowledge gaps. Biosystems Engineering 2013, 114, 358–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdogan, M.; et al. Remote sensing of irrigated agriculture: Opportunities and challenges. Remote Sensing 2010, 2, 2274–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantazi, X.E.; Moshou, D.; Bochtis, D. AI applications of predictive models in precision agriculture. Agronomy 2020, 10, 98. [Google Scholar]

- Potts, S.G.; et al. Safeguarding pollinators and their values to human well-being. Nature 2016, 540, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, D.K.; et al. Climate change has likely already affected global food production. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijswijk, K.; Brazendale, R. (2017). Technology and skills in the agri-food system: An overview of trends and policy options for the future. Agribusiness and Economics Research Unit, Lincoln University.

- Rijswijk, K.; Klerkx, L.; Turner, J.A. Digitalisation in the New Zealand agricultural knowledge and innovation system: Initial understandings and emerging organisational responses to digital agriculture. NJAS - Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences 2019, 90–91, 100313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, D.C.; Chilvers, J. Agriculture 4.0: Broadening responsible innovation in an era of smart farming. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2018, 2, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossel RA, V.; Bouma, J. Soil sensing: A new paradigm for agriculture. Agricultural Systems 2016, 148, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossel, R.A.V.; et al. Continental-scale soil carbon composition anlyses prediction using, Vis-Nir. Geoderma 2016, 155. [Google Scholar]

- Rotz, S.; et al. Automated pastures and the digital divide: How agricultural technologies are shaping labour and rural communities. Journal of Rural Studies 2019, 68, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, E.J.; Evans, R.G.; Stone, K.C.; Camp, C.R. Opportunities for conservation with precision irrigation. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation 2005, 60, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, M.; Brem, A. How to benefit from open innovation? An empirical investigation of open innovation, external partnerships, and firm capabilities in the automotive industry. International Journal of Technology Management 2015, 69, 54–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seppelt, R.; et al. Harmonizing biodiversity conservation and productivity in the context of increasing demands on landscapes. BioScience 2016, 66, 890–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamshiri, R.R.; et al. Research and development in agricultural robotics: A perspective of digital farming. International Journal of Agricultural and Biological Engineering 2018, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; et al. Edge computing: Vision and challenges. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2016, 3, 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Ganapathysubramanian, B.; Singh, A.K.; Sarkar, S. Machine learning for high-throughput stress phenotyping in plants. Trends in Plant Science 2016, 21, 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sladojevic, S.; Arsenovic, M.; Anderla, A.; Culibrk, D.; Stefanovic, D. Deep neural networks based recognition of plant diseases by leaf image classification. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience 2016, 2016, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.; et al. (2014). Agriculture, forestry and other land use (AFOLU). In Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change (pp. 811–922). Cambridge University Press.

- Sørensen, C.G.; et al. A user-centric approach for information modelling in arable farming. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2010, 73, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R.S.; Barto, A.G. (2018). Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction. MIT Press.

- Thenkabail, P.S.; et al. Hyperspectral remote sensing of vegetation and agricultural crops. Photogrammetric Engineering & Remote Sensing 2018, 84, 741–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, F. (2017). A supply chain traceability system for food safety based on HACCP, blockchain & Internet of Things. In 14th International Conference on Services Systems and Services Management (pp. 1–6).

- Tilman, D.; Balzer, C.; Hill, J.; Befort, B.L. Global food demand and the sustainable intensification of agriculture. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2011, 108, 20260–20264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, A.P. Biosensors: Sense and sensibility. Chemical Society Reviews 2013, 42, 3184–3196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (2019). World Population Prospects 2019. https://population.un.org/wpp/.

- Ustin, S.L.; Middleton, E.M. Current and near-term advances in Earth observation for ecological applications. Ecological Processes 2021, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Burg, S.; et al. Ethics of smart farming: Current questions and directions for responsible innovation towards the future. NJAS-Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences 2019, 90–91, 100289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Waa, J.; et al. Contrastive explanations with local foil trees. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1806.07470. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; et al. Mapping soil erosion risk in a typical karst area using GIS and remote sensing. Environmental Earth Sciences 2016, 75, 142. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; et al. Integrating reinforcement learning with, agricultural systems. Applied Soft Computing 2018, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfert, S.; et al. Big data in smart farming—A review. Agricultural Systems 2017, 153, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; et al. Edge computing paradigm for smart farming: A case study. Sensors 2018, 18, 4347. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L.; et al. A hybrid model integrating a neural network with wavelet decomposition for commodity price forecasting. Applied Soft Computing 2016, 43, 478–494. [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, Z.; et al. Smart farming in poultry production with the integration of Internet of Things (IoT), blockchain, and artificial intelligence (AI). AgriEngineering 2020, 2, 416–442. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Kovacs, J.M. The application of small unmanned aerial systems for precision agriculture: A review. Precision Agriculture 2012, 13, 693–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Wang, M.; Wang, N. Precision agriculture—A worldwide overview. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2002, 36, 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| AI Technology | Applications in Agriculture | References |

|---|---|---|

| Machine Learning (ML) | Crop yield prediction, disease detection, input recommendation systems | Liakos et al. (2018); Jeong et al. (2016) |

| Deep Learning (DL) | Image-based plant disease detection, phenotyping, weed and crop recognition | Mohanty et al. (2016); Jiang et al. (2020) |

| Computer Vision | Automated stress detection, real-time growth stage tracking, robotic harvesting | Sladojevic et al. (2016); Bac et al. (2014) |

| Reinforcement Learning | Autonomous vehicles navigation, resource management, greenhouse climate control | Mayr et al. (2019); Chen & Guestrin (2016) |

| Internet of Things (IoT) | Real-time monitoring using sensors, data collection for AI models, precision irrigation | Jayaraman et al. (2016); Turner (2013) |

| Robotics and Automation | Autonomous planting, weeding robots, robotic harvesting systems | Bechar & Vigneault (2016); Shamshiri et al. (2018) |

| Predictive Analytics | Market trend prediction, climate change impact assessment, yield optimization modeling | Yu et al. (2016); Lobell & Field (2007) |

| Benefit | Description | References |

|---|---|---|

| Increased Productivity | Higher crop yields and better quality due to optimized farming practices enabled by AI | McKinsey Global Institute (2018) |

| Cost Reduction | Decreased reliance on manual labor and efficient use of inputs reduce overall operational costs | Rotz et al. (2019) |

| Environmental Sustainability | Precision application of resources minimizes environmental impact, promoting sustainable agriculture | Zhai et al. (2020); Lal (2016) |

| Enhanced Decision-Making | Data-driven insights allow for proactive and informed decisions, reducing risks associated with farming | Bronson (2018); Chen et al. (2019) |

| Market Competitiveness | Ability to meet market demands with consistency and quality, improving competitiveness in global markets | Bronson (2018) |

| Labor Efficiency | Automation addresses labor shortages and reduces the physical burden on farmers | Bechar & Vigneault (2016) |

| Risk Management | Predictive analytics help in forecasting market trends and weather, aiding in risk mitigation strategies | Yu et al. (2016); Lobell & Field (2007) |

| Recommendation | Description | References |

|---|---|---|

| Investment in Infrastructure | Development of rural internet connectivity and energy supply to support AI technologies | Kshetri (2014); FAO (2017) |

| Capacity Building and Education | Training programs for farmers and technicians to build expertise in AI applications | Eastwood et al. (2019); FAO (2017) |

| Policy Support and Incentives | Government policies providing subsidies, tax incentives, and supportive regulations to encourage AI adoption | OECD (2019); European Commission (2019) |

| Data Governance and Security | Establishment of clear data ownership rights and robust cybersecurity measures | Wolfert et al. (2017); Carbonell (2016) |

| Development of Affordable Technologies | Creation of cost-effective AI solutions suitable for smallholder farmers | Ferris et al. (2014); Chavas & Nauges (2020) |

| Ethical Frameworks | Implementation of ethical guidelines to ensure fair and responsible use of AI in agriculture | van der Burg et al. (2019); European Commission (2019) |

| Encouraging Collaboration | Fostering partnerships among stakeholders, including farmers, tech developers, and policymakers | OECD (2018); Fleming et al. (2018) |

| Aspect | Traditional Farming | AI-Enabled Farming | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decision-Making | Based on farmer's experience and intuition | Data-driven, utilizing AI algorithms for precision | Liakos et al. (2018); Wolfert et al. (2017) |

| Resource Utilization | Uniform application of inputs across the field | Variable rate application based on real-time data | Mulla (2013); Gebbers & Adamchuk (2010) |

| Labor Requirements | High dependence on manual labor | Reduced labor through automation and robotics | Bechar & Vigneault (2016); Rotz et al. (2019) |

| Environmental Impact | Higher risk of overuse of chemicals and water | Minimized environmental footprint due to optimized input usage | Zhai et al. (2020); Lal (2016) |

| Yield and Productivity | Variable yields influenced by unpredictable factors | Improved yields through predictive analytics and proactive management | Khaki & Wang (2019); McKinsey Global Institute (2018) |

| Cost Efficiency | Potentially higher costs due to inefficiencies | Long-term cost savings from optimized operations despite initial investment | Chavas & Nauges (2020); Eastwood et al. (2019) |

| Adaptability to Challenges | Reactive approach to pests, diseases, and climate issues | Proactive and adaptive strategies informed by AI predictions | Singh et al. (2016); Lobell & Field (2007) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).