Submitted:

06 March 2025

Posted:

06 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

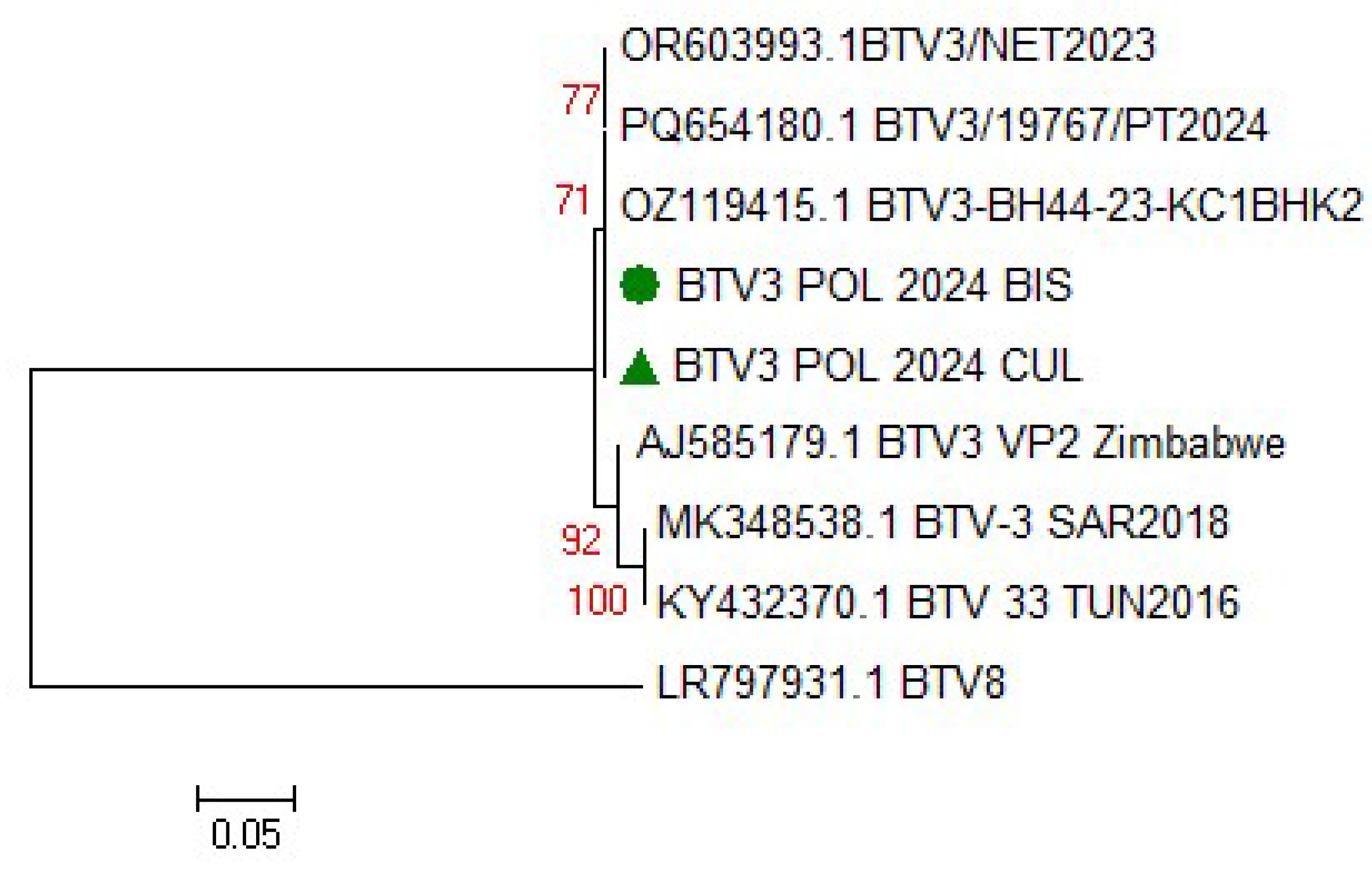

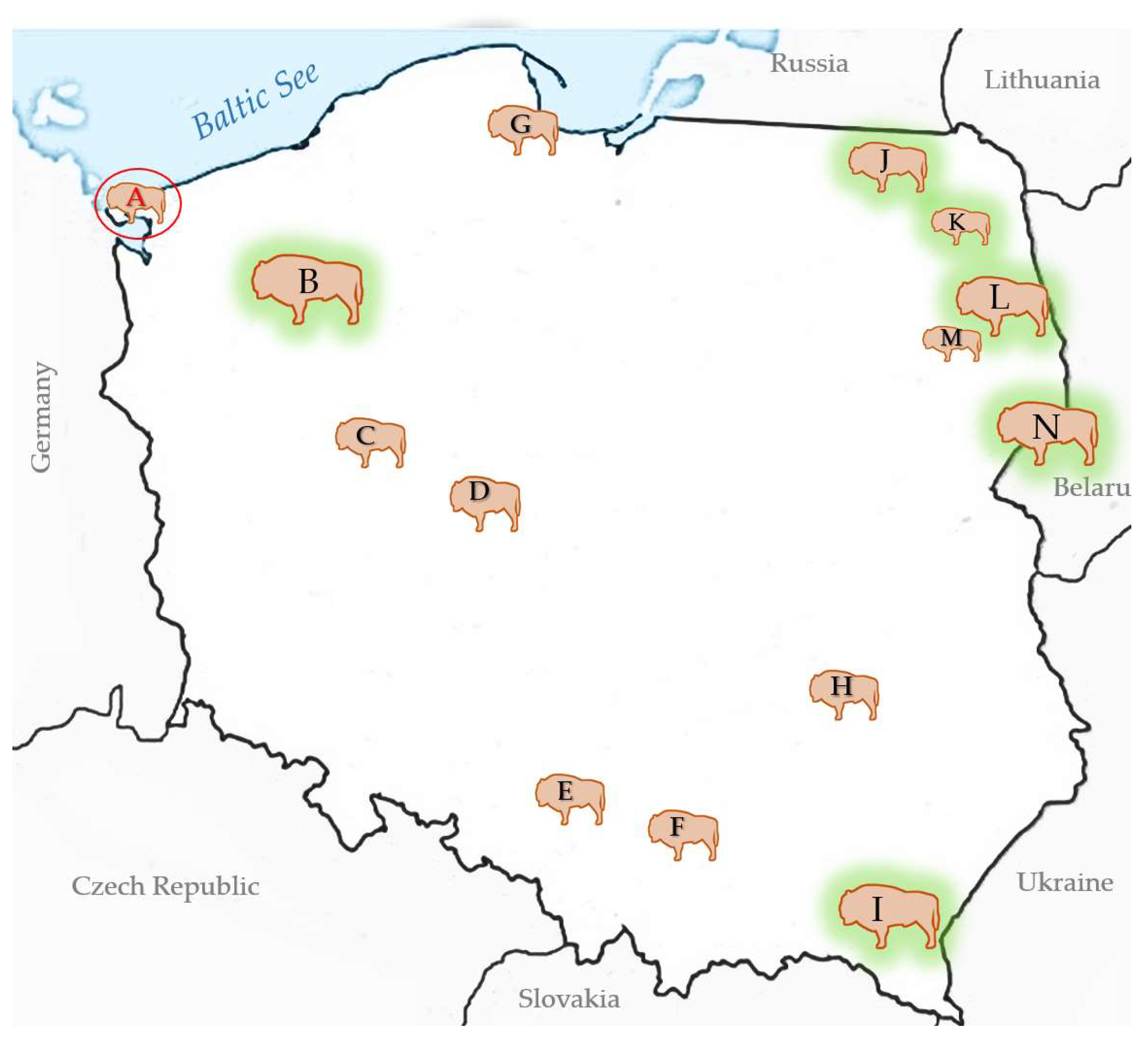

The emergence of an another bluetongue virus serotype BTV-3 has been causing great losses in animal farming in Europe since fall 2023. The virus spreads faster than the epidemic BTV-8, which appeared on the continent nine years earlier. The study describes first case of BTV-3 in Poland detected in European bison (Bison bonasus), just approx. 15 km from the German-Polish border. The animal suffered from severe and fatal hemorrhagic disease. The symptoms included respiratory problems, bloody diarrhea and rapidly progressive cachexia. In addition to confirmation of BTV-3 infection in the blood and spleen of the animal, the virus was also detected in one of pool of blood-fed Culicoides punctatus caught near the enclosure two weeks after the death of European bison. This is the first evidence of BTV-3 detection in C. punctatus what suggests vector competency for this serotype. Phylogenetic analysis based on the segment 2 of the virus revealed homology of Polish isolate to the BTV-3 strains circulating in the Netherlands, Germany and Portugal, and slightly lower similarity the BTV-3 strains detected in sheep in Sardinia (Italy) in 2018 and in Tunisia in November 2016. Retrospective serosurvey of the exposure to BTV in thirteen other European bison populations widespread in the country indicated that the observed case at the Wolin National Park was the first BTV-3 to be detected in Poland.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Study and Clinical Diagnosis

2.2. Culicoides Monitoring

2.3. Surveillance Sampling

2.4. Virological Testing

2.5. Molecular Testing

2.6. Serological Testing

2.7. Additional Testing

3. Results

3.1. Case Study

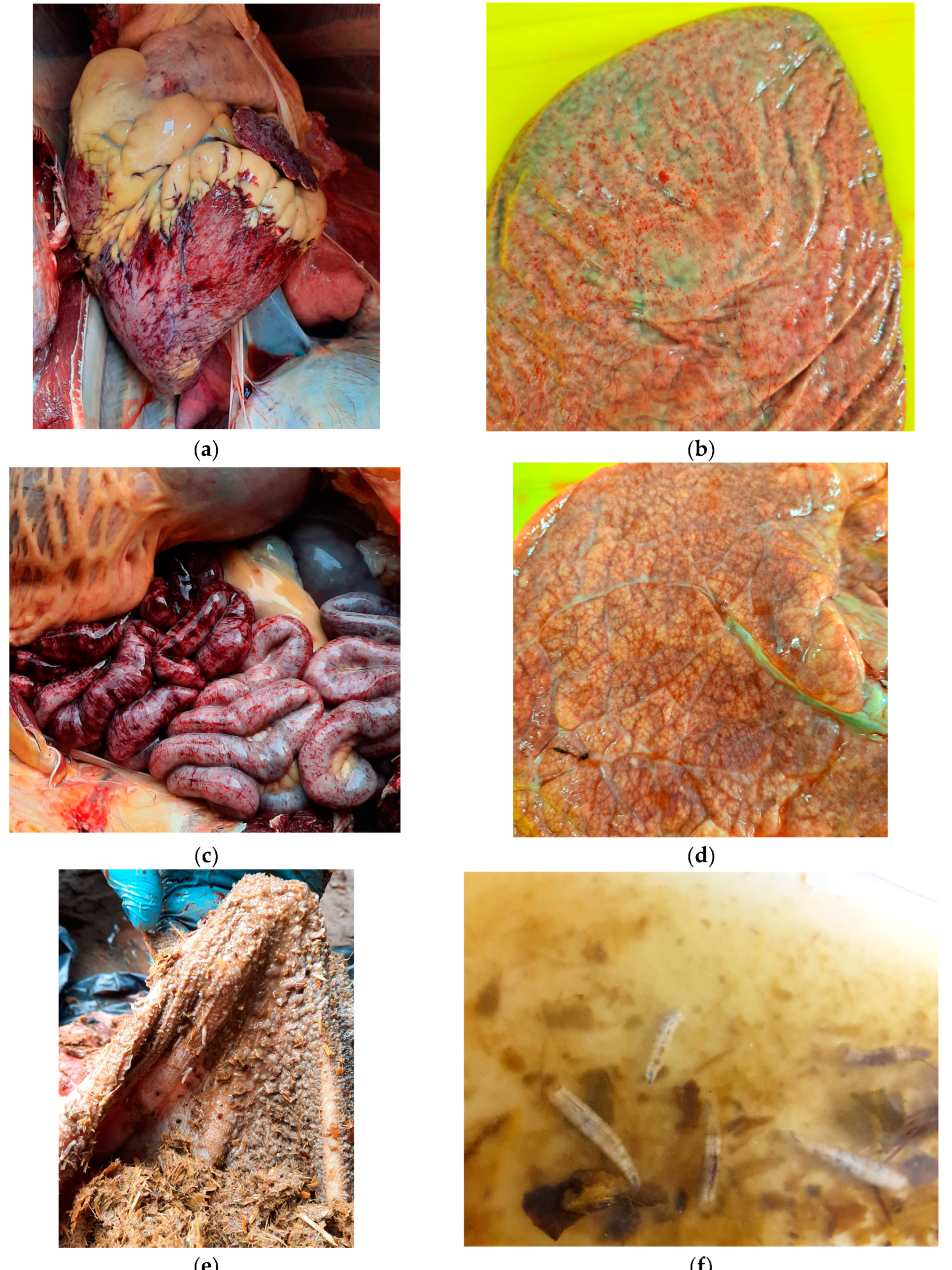

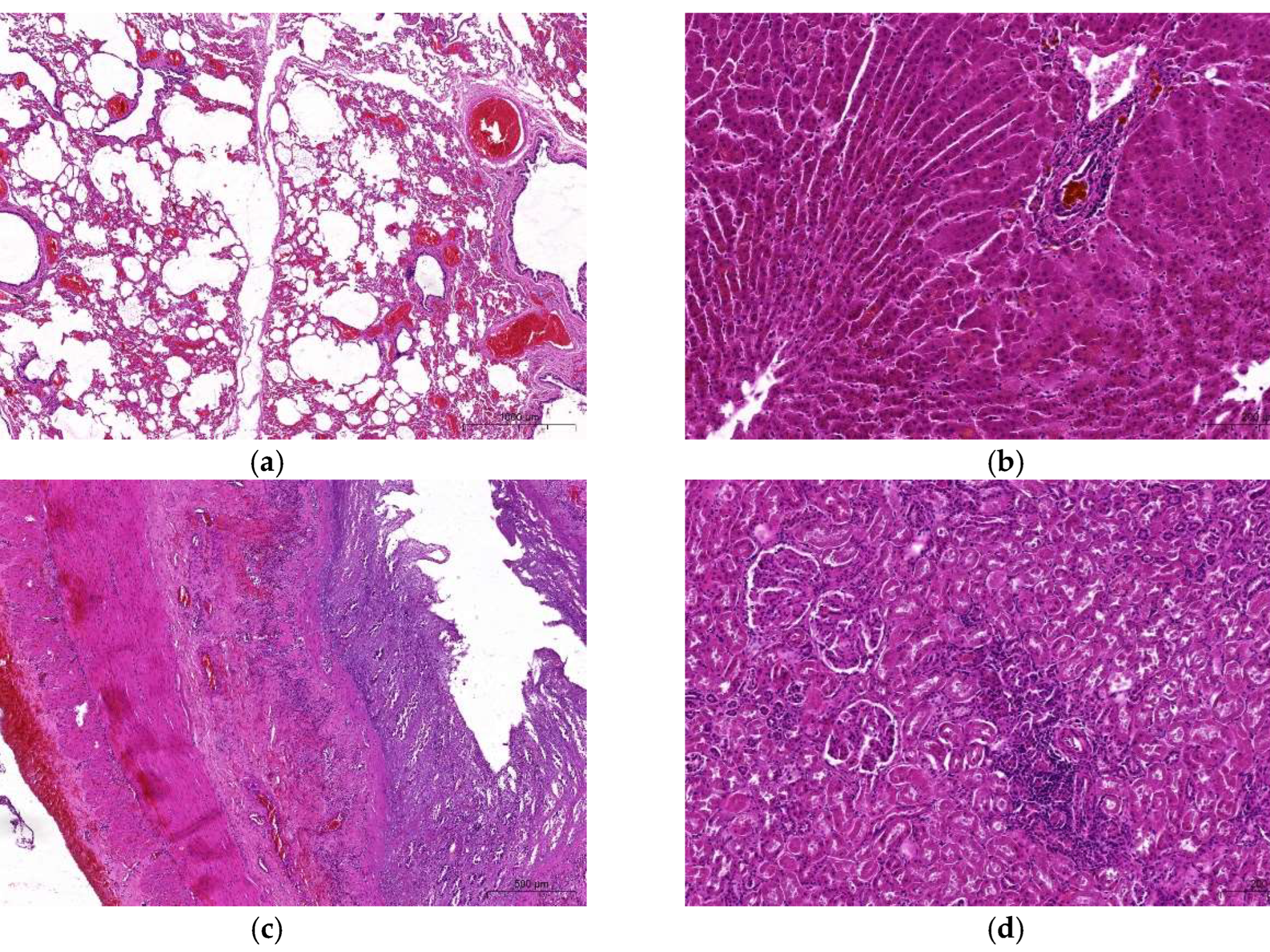

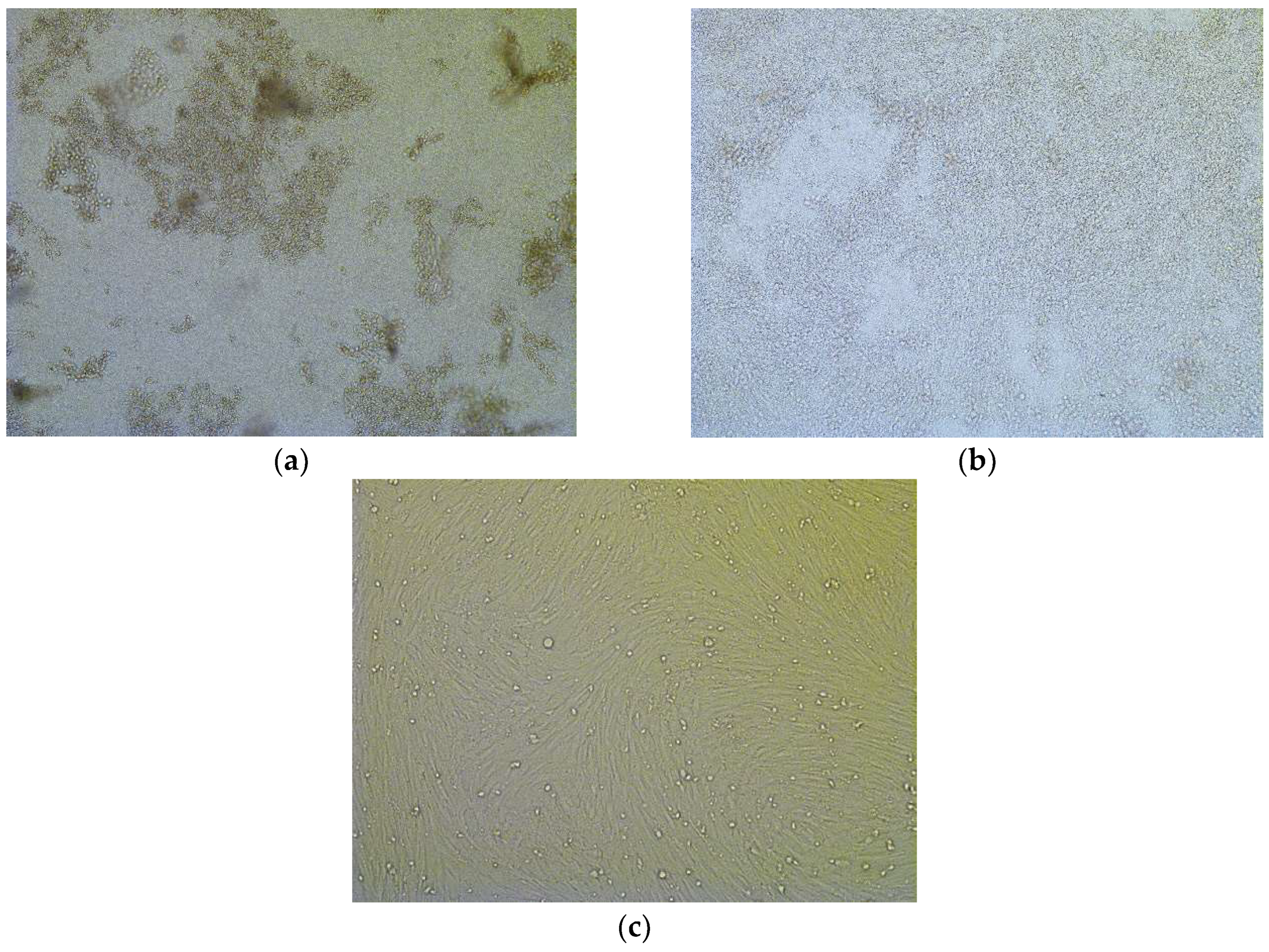

3.1.1. Macro- and Microscopic Findings

3.1.2. BTV Detection

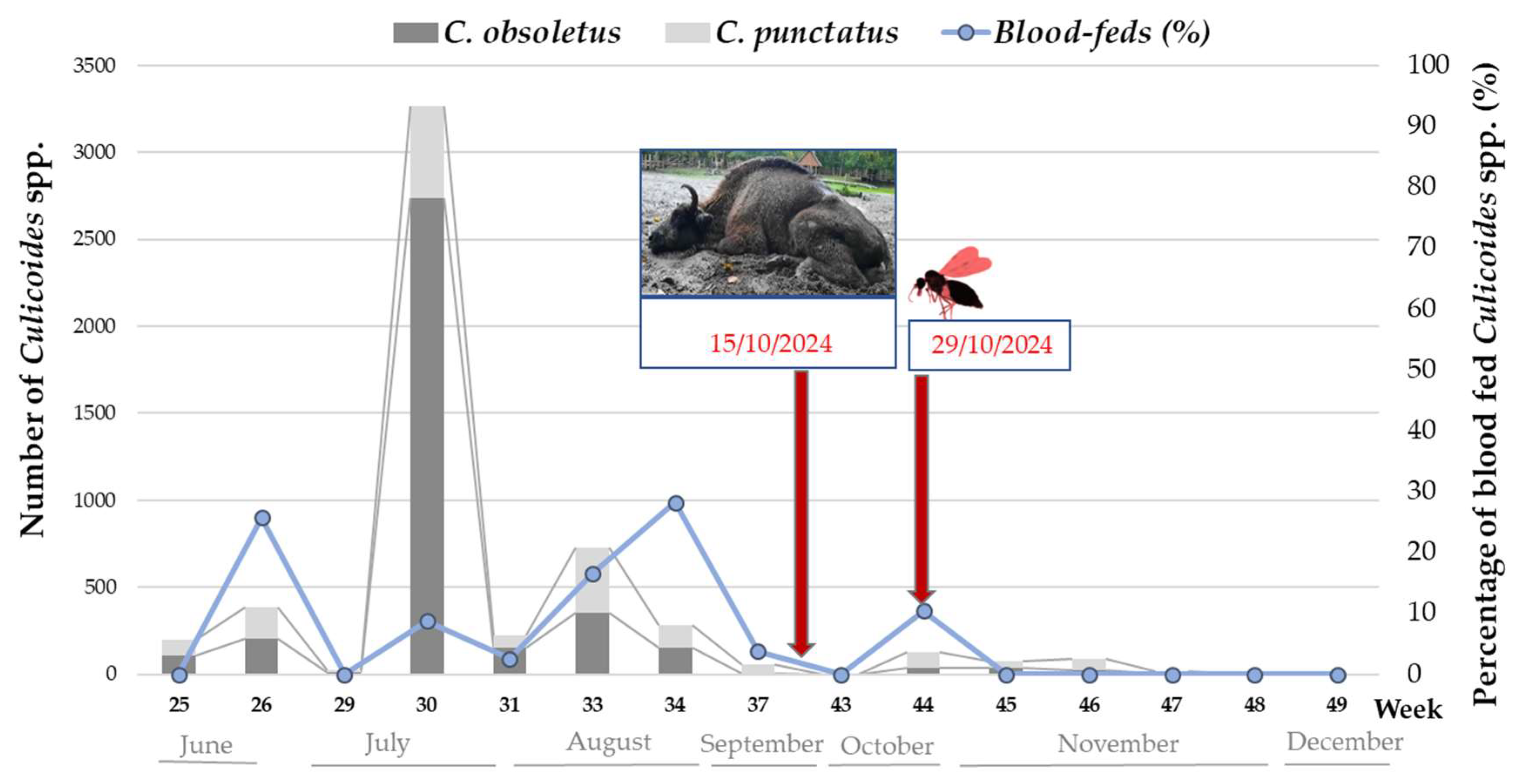

3.1.3. Culicoides spp. Activity and BTV Detection

3.1.4. BTV Strain Characterization

3.2. BTV Survey of European Bison in Poland

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Walton, T. E. The history of bluetongue and a current global overview. Vet. Ital. 2004, 40, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Purse, B. V.; Brown, H. E.; Harrup, L.; Mertens, P. P.; Rogers, D. J. Invasion of bluetongue and other orbivirus infections into Europe: the role of biological and climatic processes. Rev. Sci. Tech. 2008, 27, 427–442. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Boender, G. J.; Hagenaars, T. J.; Holwerda, M.; Spierenburg, M. A. H.; van Rijn, P. A.; van der Spek, A. N.; Elbers, A. R. W. Spatial Transmission Characteristics of the Bluetongue Virus Serotype 3 Epidemic in The Netherlands, 2023. Viruses 2024, 16, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van den Brink, K. M. J. A., Santman-Berends, I. M. G. A., Harkema, L., Scherpenzeel, C. G. M., Dijkstra, E., Bisschop, P. I. H., Peterson, K., van de Burgwal, N. S., Waldeck, H. W. F., Dijkstra, T., Holwerda, M., Spierenburg, M. A. H., van den Brom, R. Bluetongue virus serotype 3 in ruminants in the Netherlands: Clinical signs, seroprevalence and pathological findings. Vet. Rec. 2024, 195, e4533.

- Voigt, A., Kampen, H., Heuser, E., Zeiske, S., Hoffmann, B., Höper, D., Holsteg, M., Sick, F., Ziegler, S., Wernike, K., Beer, M., Werner, D. Bluetongue Virus Serotype 3 and Schmallenberg Virus in Culicoides Biting Midges, Western Germany, 2023. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2024, 30, 1438–1441.

- Newbrook, K., Obishakin, E., Jones, L. A., Waters, R., Ashby, M., Batten, C., Sanders, C. Clinical disease in British sheep infected with an emerging strain of bluetongue virus serotype 3. Vet. Rec. 2025, 196, e4910. [CrossRef]

- Barros, S. C., Henriques, A. M., Ramos, F., Luís, T., Fagulha, T., Magalhães, A., Caetano, I., Abade Dos Santos, F., Correia, F. O., Santana, C. C., Duarte, A., Villalba, R., Duarte, M. D. Emergence of Bluetongue Virus Serotype 3 in Portugal. Viruses 2024, 16, 1845.

- Barua, S. , Rana, E. A., Prodhan, M. A., Akter, S. H., Gogoi-Tiwari, J., Sarker, S., Annandale, H., Eagles, D., Abraham, S., Uddin, J. M. The Global Burden of Emerging and Re-Emerging Orbiviruses in Livestock: An Emphasis on Bluetongue Virus and Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease Virus. Viruses 2024, 17, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Mayo, C. , Mullens, B., Gibbs, E. P., MacLachlan, N. J. Overwintering of Bluetongue virus in temperate zones. Vet. Ital. 2016, 52, 243–246. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, A. , Darpel, K., Mellor, P. S. Where does bluetongue virus sleep in the winter? PLoS Biol. 2008, 6, e210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larska, M. , Lechowski, L., Grochowska, M., Żmudziński, J. F. Detection of the Schmallenberg virus in nulliparous Culicoides obsoletus/scoticus complex and C. punctatus - the possibility of transovarial virus transmission in the midge population and of a new vector. Vet. Microbiol. 2013, 166, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Falconi, C. , López-Olvera, J. R., Gortázar, C. BTV infection in wild ruminants, with emphasis on red deer: a review. Vet. Microbiol. 2011, 151, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Talavera, S. , Muñoz-Muñoz, F., Verdún, M., Pujol, N., Pagès, N. Revealing potential bridge vectors for BTV and SBV: a study on Culicoides blood feeding preferences in natural ecosystems in Spain. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2018, 32, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Plumb, G., Kowalczyk, R. Hernandez-Blanco, J.A. Bison bonasus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T2814A45156279. (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Nores, C. , Álvarez-Laó D., Navarro A., Pérez-Barbería F. J., Castaños P. M., Castaños de la Fuente J., Morales Muñiz A., Azorit C., Muñoz-Cobo J., Fernández Delgado C., Granado Lorencio C., Palmqvist P., Soriguer R., Delibes M., Vilà M., Simón M., Cabezudo B., Galán C., García-Berthou E., Almodóvar A., Elvira B., Brufao Curiel P., Casinos A., Herrero J., Blanco J. C., García-González R., Nogués-Bravo D., Margalida A., Fisher B., Arlettaz R., Gordon I. J., Ludwig A., Lovari S., Cook B. D., Carranza J., Csányi S., Apollonio M., Kowalczyk R., Demarais S., López-Bao J. V. Rewilding through inappropriate species introduction: The case of European bison in Spain. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2024, 6, e13221. [Google Scholar]

- Raczyński, J. European Bison Pedigree Book 2023; Białowieża National Park: Białowieża, Poland, 2024; p. 9. Available online: https://bpn.gov.pl/pliki-do-pobrania/pobierz/7cc95262-0985-45df-9b39-493b293e87da.pdf (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Mathieu, B. , Cêtre-Sossah, C., Garros, C., Chavernac, D., Balenghien, T., Carpenter, S., Setier-Rio, M. L., Vignes-Lebbe, R., Ung, V., Candolfi, E., Delécolle, J. C. (2012). Development and validation of IIKC: an interactive identification key for Culicoides (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae) females from the Western Palaearctic region. Parasites vectors 2012, 5, 137. [Google Scholar]

- Kęsik-Maliszewska, J. , Larska, M., Collins, Á. B., Rola, J. Post-Epidemic Distribution of Schmallenberg Virus in Culicoides Arbovirus Vectors in Poland. Viruses 2019, 11, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larska, M. , Tomana, J., Socha, W., Rola, J., Kubiś, P., Olech, W., Krzysiak, M. K. Learn the Past and Present to Teach the Future—Role of Active Surveillance of Exposure to Endemic and Emerging Viruses in the Approach of European Bison Health Protection. Diversity 2023, 15, 535. [Google Scholar]

- Larska, M.; Krzysiak, M. K. Infectious diseases monitoring as an element of Bison bonasus species protection. In Compendium of the European Bison (Bison bonasus) Health Protection, National Veterinary Research Institute: Puławy, Poland, 2022; pp. 71–96.

- Larska, M. , Krzysiak M.K. Infectious Disease Monitoring of European Bison (Bison Bonasus). In Wildlife Population Monitoring, Ferretti M. Ed.; IntechOpen Limited, London, UK, 2019; pp. 1-21.

- WOAH Terrestrial Manual 2021, Bluetongue (Infection with Bluetongue Virus), chapter 3.3.3.

- Hofmann, M. , Griot, C., Chaignat, V. P., Erler, L., Thür, B. Bluetongue disease reaches Switzerland. Schweiz. Arch. Tierheilkd. 2008, 150, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Tamura, K., Dudley, J., Nei, M., Kumar, S.: MEGA4: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol 2007, 24, 1596–1599.

- Larska, M. , Tomana, J., Krzysiak, M. K., Pomorska-Mól, M., Socha, W. Prevalence of coronaviruses in European bison (Bison bonasus) in Poland. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanDevanter, D. R. , Warrener, P., Bennett, L., Schultz, E. R., Coulter, S., Garber, R. L., Rose, T. M. Detection and analysis of diverse herpesviral species by consensus primer PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1996, 34, 1666–1671. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Videvall, E. , Bensch, S., Ander, M., Chirico, J., Sigvald, R., Ignell, R. Molecular identification of bloodmeals and species composition in Culicoides biting midges. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2013, 27, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Friedrich-Loeffler-Institut (FLI) webpage on Bluetongue situation. Available online: https://www.fli.de/de/aktuelles/tierseuchengeschehen/blauzungenkrankheit/ (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Rodrigues, E. (PWN Waterleidingbedrijf Noord-Holland, Velserbroek, the Netherlands); Rasmussen, T. B. (Statens Serum Institut, Copenhagen, Denmark). Personal communication, 2024.

- Larska, M. , Krzysiak, M. K., Smreczak, M., Polak, M. P., Żmudziński, J. F. First detection of Schmallenberg virus in elk (Alces alces) indicating infection of wildlife in Białowieża National Park in Poland. Vet. J. 2013, 198, 279–281. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Krzysiak, M. K. , Iwaniak, W., Kęsik-Maliszewska, J., Olech, W., Larska, M. Serological study of exposure to selected arthropod-borne pathogens in European bison (Bison bonasus) in Poland. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2017, 64, 1411–1423. [Google Scholar]

- Orłowska, A. , Trębas, P., Smreczak, M., Marzec, A., Żmudziński, J. F. First detection of bluetongue virus sero-type 14 in Poland. Arch. Virol. 2016, 161, 1969–1972. [Google Scholar]

- Koltsov, A. , Tsybanov, S., Gogin, A., Kolbasov, D., Koltsova, G. Identification and characterization of bluetongue virus serotype 14 in Russia. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Flannery, J. , Frost, L., Fay, P., Hicks, H., Henstock, M., Smreczak, M., Orłowska, A., Rajko-Nenow, P., Darpel, K., Batten, C. BTV-14 Infection in Sheep Elicits Viraemia with Mild Clinical Symptoms. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 892. [Google Scholar]

- Krzysiak, M.K. , Anusz, K., Konieczny, A., Rola, J., Salat, J., Strakova, P., Olech, W., Larska, M. The European bison (Bison bonasus) as an indicatory species for the circulation of tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV) in natural foci in Poland. Ticks Tick Borne Dis, 1799. [Google Scholar]

- Kęsik-Maliszewska, J., Krzysiak, M. K., Grochowska, M., Lechowski, L., Chase, C., Larska, M. EPIDEMIOLOGY OF SCHMALLENBERG VIRUS IN EUROPEAN BISON ( BISON BONASUS) IN POLAND. J. Wildl. Dis. 2018; 54, 272–282.

- Juszczyk, A., Larska, M., Krzysiak, M.K. Frequency of tick infestation in European bison species in the context of changing environmental conditions as an indicator of potential risk of pathogen exposure. In Proceedings of the Conference 100 years of European bison restitution, Niepołomice, Poland, 6-8 March 2023; pp. 37–38.

- Foxi, C., Delrio, G., Falchi, G., Marche, M. G., Satta, G., & Ruiu, L. Role of different Culicoides vectors (Diptera: Ceratopogonidae) in bluetongue virus transmission and overwintering in Sardinia (Italy). Parasit. Vectors 2016, 9, 440.

- Goffredo, M. , Catalani, M., Federici, V., Portanti, O., Marini, V., Mancini, G., Quaglia, M., Santilli, A., Teodori, L., Savini, G. Vector species of Culicoides midges implicated in the 2012–2014 Bluetongue epidemics in Italy. Vet. Ital. 2015, 51, 131–138. [Google Scholar]

- Yavru, S., Dik, B., Bulut, O., Uslu, U., Yapici, O., Kale, M., Avci, O. New Culicoides vector species for BTV transmission in Central and Central West of Anatolia. Annu. Res. Rev. Biol. 2018, 27, 1–9.

- Hoffmann, B. , Bauer, B., Bauer, C., Bätza, H. J., Beer, M., Clausen, P. H., Geier, M., Gethmann, J. M., Kiel, E., Liebisch, G., Liebisch, A., Mehlhorn, H., Schaub, G. A., Werner, D., Conraths, F. J. Monitoring of putative vectors of bluetongue virus serotype 8, Germany. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2009, 15, 1481–1484. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | BTV seropositive | Pan-BTV RT-PCR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/N1 | % (CI2) | n/N1 | strain | ||

| Origin (total population size3) | |||||

| A - Wolin National Park (9) | 1/3 | 33.3 (0.8-90.6) | 13/1 | BTV-3 | |

| B – Zachodniopomorskie herds (349) | 0/4 | 0 (0-60.2) | 0/0 | ||

| I – Bieszczady (750) | 0/10 | 0 (0-30.8) | 0/0 | ||

| C - ZOO Poznań (9) | 0/1 | 0 (0-97.5) | 0/0 | ||

| D – Gołuchów (7) | 0/2 | 0 (0-84.1) | 0/0 | ||

| E – Pszczyna (53) | 1/51 | 2 (0.05-10.5) | 0/1 | ||

| F – Niepołomice (16) | 0/1 | 0 (0-97.5) | 0/0 | ||

| G - ZOO Gdańsk (8) | 0/2 | 0 (0- | 0/0 | ||

| H – Bałtów (9) | 0/4 | 0 (0-60.2) | 0/0 | ||

| J - Borecka Forest (127) | 0/3 | 0 (0-70.8) | 0/0 | ||

| K - Augustowska Forest (23) | 0/1 | 0 (0-97.5) | 0/0 | ||

| L - Knyszyńska Forest (298) | 3/16 | 18.8 (4.0-45.6) | 0/3 | ||

| M – Kopna Góra | 0/1 | 0 (0-97.5) | 0/0 | ||

| N - Białowieża Forest (829) | 33/62 | 53.2 (40.1-66.0) | 0/33 | ||

| Population type | |||||

| free-living | 35/82 | 42.7 (31.8-54.1) | |||

| captive | 3/79 | 3.8 (0.7-10.7) | |||

| Age group | |||||

| ≤ 1 year old | 2/26 | 7.7 (1.0-25.1) | 0/1 | ||

| 2-3 years old | 1/38 | 2.6 (0.056-13.8) | 0/1 | ||

| ≥ 4 years old | 34/97 | 35.0 (25.9-45.8) | 14/34 | BTV-3 | |

| Gender | |||||

| female | 22/72 | 30.6 (20.5-43.0) | 14/22 | BTV-3 | |

| male | 15/89 | 16.8 (9.7-26.3) | 0/15 | ||

| Sanitary status | |||||

| immobilized (healthy) | 7/84 | 8.3 (3.4-16.4) | 0/7 | ||

| eliminated | 17/40 | 42.5 (27.0-59.1) | 0/17 | ||

| fallen | 11/26 | 42.3 (23.4-63.1) | 14/11 | BTV-3 | |

| dead in traffic accident | 2/7 | 28.6 (3.7-71.0) | 0/2 | ||

| missing data | 1/4 | 25.0 (0.6-80.6) | 0/1 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).