1. Introduction

Information and Communication Technology (ICT), an extension of the term Information Technology as we know it today, is a relatively new domain in the human society development compared to our long anthropological evolution. ICT first emerged as a concept in mathematics, connected with computing and communicating information in the 1950s. Soon after mathematics, its use extended to private and public economic and administrative fields (etc. military, research, diplomatic) [

1,

2,

3]. Its huge potential for social and economic development made it spread quickly to other fields, such as health, and education, though there is an innovation gap between the private and public sectors [

4,

5]. Compared to a century ago, at least in developed and many developing countries, we cannot conceive our personal, academic, and work life without the use of ICT tools [

6]. Despite little initial confidence that ICT will be a part of educational facilities, and as a result of COVID-19 accelerating effect the digitalisation process has become the focus of educational institutions more so than before, building what Manuel Castells calls Information Society [

7,

8,

9].

Current research shows that solely using ICT as tools mediating the process of reaching educational objectives may not have the same range of results as a set of educational tools and strategies chosen, adapted and combined for specific classes and fields by a skilled teacher, or even using a student-centred approach, as opposed to a teacher-centred approach [

10,

11,

12]. The social component of learning is perhaps the main reason why today, with all the knowledge and technology available to us, teaching is an entirely self-conducted activity, it is not performed fully online, using only digital tools and content, or it is not taught in class only by using technology to mediate the transmission of content. Lev Vygotsky founded his theory on the use of linguistic communication between child and teacher to enhance understanding of scientific principles in an era without digital tools [

13], while Seymour Papert applies his principle to devise games with a social component that would implicitly teach children scientific principles of an abstract nature [

14,

15], while other researchers state that digital platforms in learning may not be sufficient for an increase in knowledge acquisition, or skill development, as success in using digital platforms in teaching to enhance students’ skills and/or knowledge may depend on the taught field [

16,

17,

18].

1.1. The Benefits and Costs of Using ICT Tools in Education

The use of technology in class by students may have a distracting role for both students and teachers [

19,

20]. Even for the adult population, studies show that there is little transfer between domains for the cognitive abilities developed using digital devices, such as games or brain teasers [

21,

22]. Higher education-based research findings indicate that the use of off-task digital tools impacts the performance on low-order tasks (e.g. knowledge, comprehension) but not on high-order tasks (e.g. essay writing), and that it affects the quality of notes-taking and overall class performance [

23,

24] .

In fact, studies investigating the effects of ICT in teaching on student’s learning, or of ICT in learning alone, state that there is a myriad of factors that corroborate their effects onto the students’ performance from a micro level (e.g. the socio-economic status of the child’s family, the child’s intrinsic or extrinsic motivation to exo factors (teacher’s attitudes towards ICT, school’s location and access to infrastructure and other teaching sources), and even to macro factors (the country’s or regional policy in areas affecting education, telecommunication infrastructure or GDP, cultural and social values) [

11,

12,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. The benefits for the students exist if there are policies in place to motivate schools, and to train teachers to systematically incorporate ICT in teaching [

3,

26,

32]. For example, in a large study that included 39 countries, Park & Weng [

26] found a positive relationship between students’ PISA results and the country’s GDP per capita, and student’s interest and perceived ICT competence and autonomy. Similarly, authors [

33] found that the country’s ICT development level, and personal use of ICT significantly predicted the academic performance in mathematics, science and reading of 4

th and 8

th grade students. However, a further study of Spanish Autonomous Communities found that only PISA science scores improved as a result of a greater use of ICT in education, whilst the PISA scores in mathematics and reading decreased [

12]. Additionally, the UN ICT and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) unit mention the access to ICT for education is a prerequisite for child development in an inclusive and equalitarian society, which represent testimonies for the importance ICT’s role in education has acquired globally [

34]. Increasing the proportion of youth with ICT skills to offer them a better chance at decent working and living conditions and offering online materials to facilitate access to education to developing regions are important SDGs 4 targets [

35,

36].

A literature review on the benefits of ICT in school shows that research is far from decisively concluding that ICT in education has a positive effect on students’ performance [

16,

19,

24,

37], and those positive effects found are mainly between the use of ICT and cognitive abilities in pre-K12 students [

26].

The lack of conclusive findings may be due to the complex nature of the relationship between the adoption of technology by non-commercial fields, such as education, regulatory policy regarding ICT, and the digital maturity (DM) level of ICT users [

31]. At the same time, technology adoption in institutions following a standardized framework is much slower than its adoption in private life, yet these effects can be confounding [

38]. Additionally, the initial research on the effects of ICT on student’s abilities performed over almost two decades to inform regulatory policies, research and assessment frameworks become outdated because of the fast pace at which technology takes over more aspects of our life before it enters education. To counteract this aspect, Gibson [

39], in a study part of the UNESCO SDGs 2030 initiative, recommends the steps to be taken to align the frameworks of data collection tools on ICT in education, to make its effects more comparable, and also more inclusive of all the factors that may influence students’ performance, such as country and school infrastructure and funding, teachers’ beliefs, a learner-centred approach, and mobile learning, which are elements of the student’s micro, meso and macro systems [

40].

1.2. A Multi-Layered Framework for a Sustainable ICT-Based Education

In the absence of a clear research framework for the complexity of ICT in education [

39], this study proposes that the multi-layered reality of the adoption of ICT in education and its effects on students’ academic performance should be investigating using the ecological system theory proposed by Urie Bronfenbrenner, applicable from human to systemic development.

His theory postulates several layers that interact and have influence on the measured behavioural outcome {40, 41]:

the microsystem (items in direct proximity and interaction with the developing individual, e.g. student’s own digital skills);

the mesosystem (the interactions between two or more microsystems in which the individual is an active participant, e.g. teacher’s digital and/or pedagogical skills, the intensity of ICT use in class, for communication with teachers, administration and peers, etc);

the exo-system (the system which indirectly affect the individual’s development though they are not an active participant or determinant in its activities);

the macrosystem (items of influence over a larger group, such as political, educational, social systems, school’s size, educational programs, etc.);

the chronosystem (important historical events which influence the dynamic of the setting in which the developing person is active, and that can be normative or non-normative).

When analysing the ecology of ICT in teaching and its effect on students’ performance in this study, several factors from Bronfenbrenner’s theory are considered within the given design, in order to produce an accurate image of how the ICT systemic and individual factors interact to influence the efficiency of ICT in higher education (HE). Such an approach has been used by other researchers to investigate the digital disconnect phenomenon between home and education institutions and its effect on children’s digital skills [

41]. The presented studies are based on the premise that digital skills are continuously developing within an ecological system framework, with an input level of participants’ digital skills, school infrastructure, and teacher abilities that help students acquire knowledge and develop further their digital and reasoning abilities.

In the current case study, carried out in 2023, we focused on a Czech private higher-education institution that has bachelor and master programs only in the field of social sciences. Our aim is to investigate whether ICT tools in education impact the academic performance of the students of social sciences.

In the Materials and Method section we present the research objectives, instruments and techniques used to collect the data and provide triangulation for specific assessments, the participants, and the procedure followed in this study. The results of the statistical and content analysis performed on the collected data are presented in the Results section and discussed further against the reviewed literature in the Discussion section. We included a Limitation section to ensure future research can use designs that reduce these limitations. We summarised our findings and their contribution to research and practice in the Conclusion section.

2. Materials and Methods

While there is a plethora of taxonomies of digital skills aligned with specific computer applications, or clusters of digital skills defined later as digital competences, with levels of proficiency [

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47], in the last decade international governmental institutions, such as the European Union, and United Nations, allocated grants for the development of, and selected several platforms that outline digital skills more consistently with the current use of ICT in education and employment [

48]. For our study we selected an ICT assessment tool (see in next paragraph) which is aligned with the UNESCO SDGs standards, the National Educational Technology Standards [

48,

49] and aligned with the ECDL criteria used to assess ICT users [

50], aiming to make our results more comparable with those of other researchers.

2.1. Research Objectives

The aim of our study is to investigate whether ICT-based pedagogical tools and methods in HE social sciences programs impact the academic performance of the students participating in these programs.

The study uses a combination of methods, in an overall case study using both quantitative (structured questionnaires and experimental interventions) and qualitative (qualitative course feedback) methods, to understand whether introducing ICT in teaching non-technical subjects (social sciences – Economic Policies, Global Economy Studies, Political Economy of the EU) can increase the academic performance of students in the included courses.

These subjects are taught traditionally without the aid of any application, or with a minimum use of MS Office apps (PowerPoint presentations for the lecturer, MS Outlook and/or email and MS Teams for teacher-student communication, MS Word and PowerPoint for seminar assignments). The pedagogical intervention in the project consists of:

1. Using applications and sites appropriate for the course content in the delivering of the course material and basing the seminar exercises on ICT resources’ functionalities.

2. Requiring class assignments that are based on the use of specific course-appropriate applications, databases, and SW making use of ICT competences (creativity and innovation, communication, technology and operations concepts and skills, critical thinking and research planning, digital citizenship, research and information fluency) part of ISTE-based maturity model (ISTE-MM) used in [

48,

49].

The research questions set for this study were:

RQ1. What is the relationship between students’ digital skills and their performance in class?

RQ2. What is the relationship between the intensity of ICT use in teaching and the students’ seminar assignment performance and exam performance?

RQ3. What teaching tools are valuable for increasing the student’s understanding, from the students’ perspective?

2.2. Data Collection

This is a case study that uses a combination of research methods, qualitative and quantitative, for data collection and analysis. The following methods and instruments were used for data collection:

The assessment of the students’ digital skills used a comprehensive Information Technology Self-Assessment Tool developed in 2009 by Virginia Niebuhr, Donna D’Alessandro and Marney Gundlach (researchers at the University of Texas Medical Branch). The tool was developed as part of the Education Technology for the Educational Scholars Program at the Academic Paediatric Association, and its authors created it as an adaptable tool for various fields of activities. It covers 13 areas of competencies which are aligned with the Van Deursen and Van Dijk’s digital skills framework [

45]. The original assessment tool is retrievable from

https://www.utmb.edu/pedi_ed/ADAPT/Toolbox/Information%20Technology%20Self-Assessment%20Tool.doc

The seminar assessments were assessed using the ISTE criteria [

48,

49], which are aligned with the questionnaires’ constructs on digital competencies.

Exam grades from the courses’ oral examination were included as relevant indicators for the students’ performance to assimilate and evaluate course-relevant material delivered using ICT tools and traditional methods.

At the end of each course examination, which were performed orally for the purpose of this research, each examined student was asked about the teaching methods, digital or traditional, that were helpful for them to comprehend the course material, which allowed the extraction of qualitative material from a total of 33 students, for three courses, but with a total of 56 responses as feedback, with some students having attended two or all three courses.

Individual semi-structured interviews were performed with 11 students to collect qualitative data on the use and usefulness of ICT-tools in teaching and communication with the teachers, school administration, and peers.

2.3. Participants

The participants in this study were 34 students of a small-size Higher Education Institution (HEI) majoring in economics, political science, or a combination of these fields. Out of the 45 students, 29 were evaluated in Course 1, 13 in Course 2, and 17 in Course 3. Some students took more than one course included in this study. The demographics of the participants are presented in

Table 1: Student participants, per course and gender.

2.4. Procedure and Ethical Considerations

As presented in

Table 2.

, the materials for the three classes taught by one of the paper’ author were designed to have different proportions of ICT tools used in teaching and seminar activities. The number of taught classes was of 12 for Course 1 (Political Economy of the EU), and of 24 (12 lectures and 12 seminars) for the other two courses (Global Economy Studies – Course 2, Economic Policies – Course 3).

All lectures and seminars for all courses made use of ICT and non-ICT resources and activities. All three assignments involved using digital tools, both provided in class and researched independently, filtering, analysing, and structuring data. Furthermore, the assignment made use of critical thinking to identify relevant information, integrate it to answer the requirements, and be able to provide a coherent explanation for the presented content.

Qualitative feedback on the used teaching tools and methods was sought from each examined student after the teacher had entered the grade in the school information system (IS), to avoid increased demand characteristics. Quantitative feedback on the digital maturity of the class (DMC) and digital maturity of the HEI (DMHEI) were given in questions 8-9 of the semi-structured interviews (the full qualitative study, which includes questionnaire with students, school managerial and IT administrators, is not included in this study report).

Content analysis was performed on the qualitative material from the course feedback.

The questionnaires based on ICTE and ISTE criteria were created in Google forms and were distributed via emails to all, and, additionally, via course MS Teams channels to students.

All questionnaires had an answering scale from 1-5, 1 being the lowest score and 5 being the highest score for the measured construct or variable.

The quantitative data was analysed statistically using SPSS licensed software.

The study was performed following the British Psychological Society (BPsS) ethical rules of conduct in research.

In the first class students were informed about the research and asked to complete the questionnaires online in class, explaining their rights as participants. Participants’ informed consent was explicitly asked in the questionnaire heading and given with the questionnaire submission.

3. Results

In the sample of 50 students who were officially enrolled in the three courses included in this study, some of whom tool more than one class. Out of 45 individuals, 17 were male and 28 were female (

Table 1). Due to withdrawal, late or no submission of seminar assignment, and/or no exam participation not all registered students were included in the measurements.

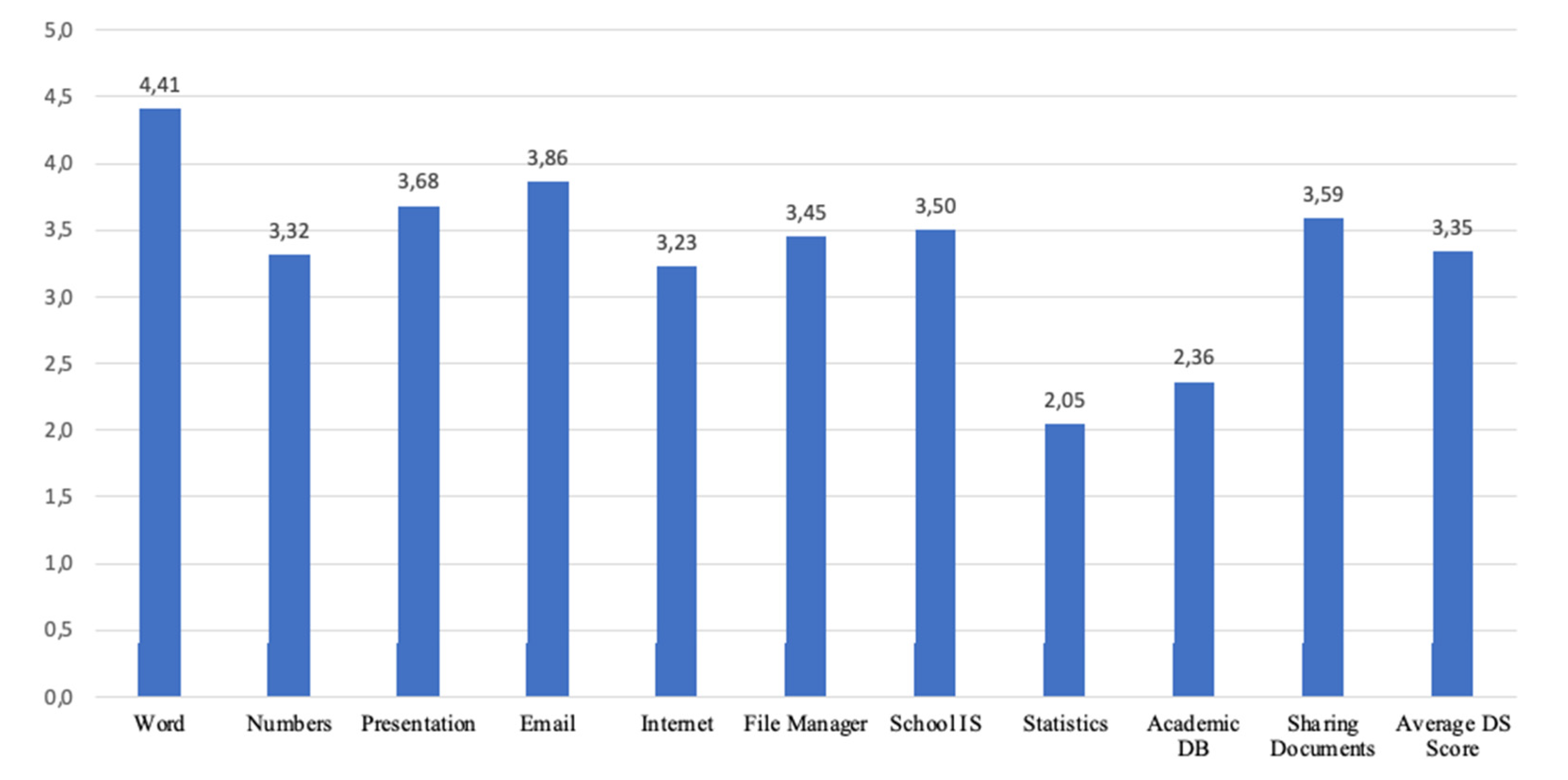

For the RQ1, descriptive statistics of digital skills per the entire sample completing this questionnaire (N=22) (

Figure 1.) indicate that students’ greatest strengths in digital skills are in Word processors (mean 4.71), Email (mean 4.3), and Presentation creators (mean 4.07). Their greatest skill gaps are in Statistical analysis applications (mean 2.52) and Searching academic DB (mean 2.66).

Independent t -sample tests showed no significantly significant differences between female and male students, though in the critical aspect of academic DB searches female students scores mean was lower by one standard deviation than that of male students (2.24 vs. 3.02, SD = .76). The non-assumed variance condition for the groups showed a statistically significant difference between female and male students on this criterion with t(20) = -2.012, p = .029, but confidence intervals range does not confirm this significance (95% CI [-1.58; 0.29]).

There were no significant correlational relationships between self-reported digital skills and course performance found for Course 2.

The figures in

Table 3. show that the Word processor and Email communication proficiency were significantly correlated with Course 1 assignments and exams, with a medium to strong positive relationship at significance level p<0.05. Email and school IS proficiency have a medium-strong positive and statistically significant correlational relationship with Course 3 exam score in Course 3, at p<0.05.

Linear regressions models were performed for all courses to investigate the predictability of the measured digital skills of students on their academic performance, measured in assignment and exam scores.

Table 4 presents several results of linear regression modelling run on each course. Other regression models, with different combinations of digital skills, were not found to be statistically significant predictors for neither the assignment nor the exam score.

The digital skills-digital competences relationship was investigated only using correlational analysis.

Table 5. shows for Course 1 the analysis found strong significant correlations between Word processor on one side, and Research and Information Fluency (RIF), and Critical Thinking (CT) on the other side. Similarly, there were found medium significant correlations between Word processor, Communication and Collaboration (CC), Digital Citizenship (DC), and Technology and Operational Concepts (TOC).

Number processor skills were found to have a medium significant correlational relationship with TOC for Course 1, and a strong significant correlational relationship with TOC for Course 3.

Email skills were found to have a medium significant correlational relationship with Creativity and Innovation (CI), CC, and CT for Course 1.

School IS skills were found to have a medium significant correlational relationship with CI for Course 3, though the confidence intervals marginally disprove the significance of this relationship.

There was no significant correlation found between self-reported digital skills and assessed digital competences for Course 2.

For RQ2 several statistical tests were performed, such as mean comparison, linear regressions, and bivariate correlations between the ICTE-MM factors and assignment and exam scores.

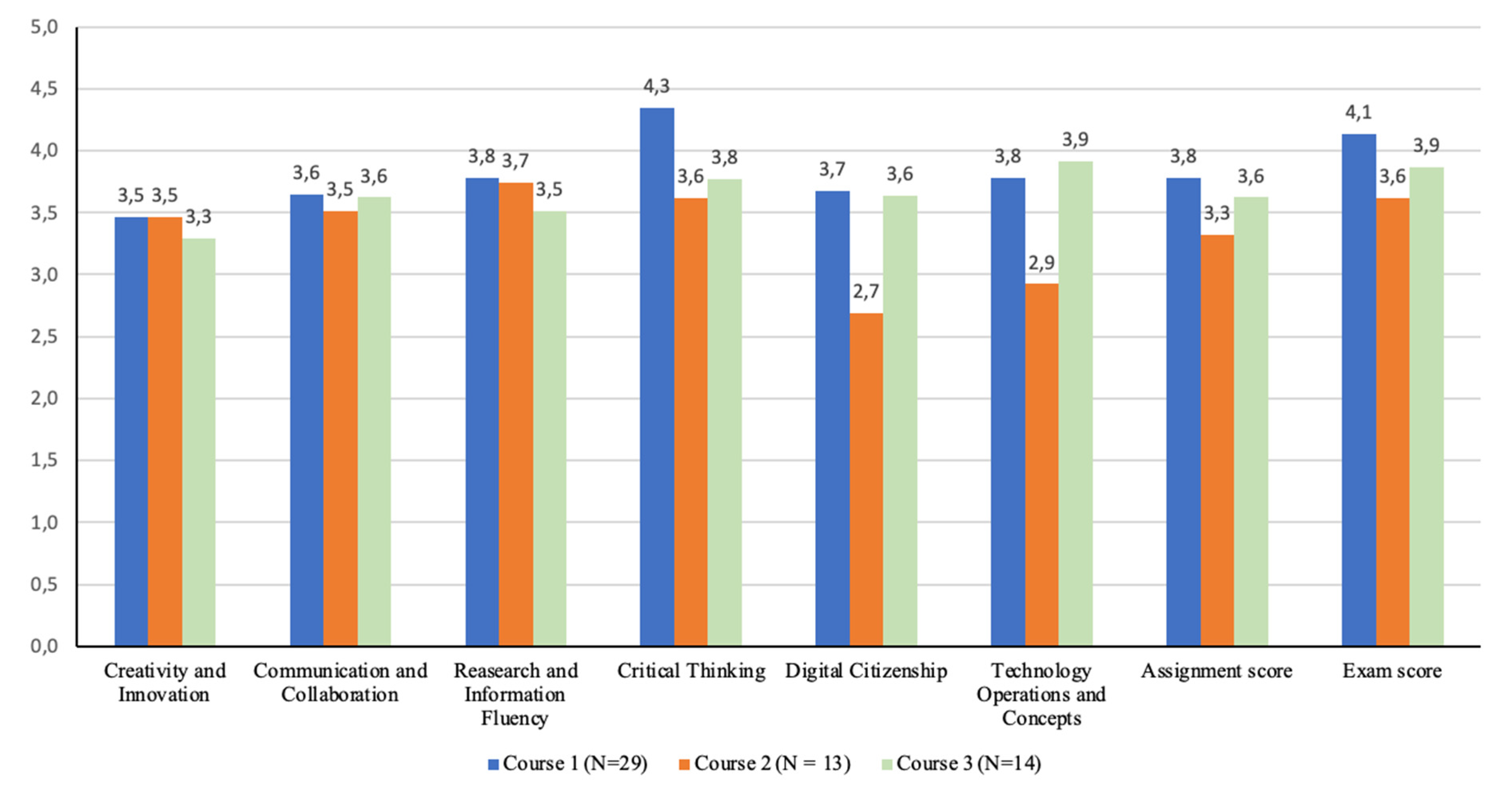

The means of digital competences measured in course assignments per each measured domain and the exam scores in each course are presented in

Figure 2., and they indicate that in Course 1 students’ assignments showed levels of competences in all ICTE-MM fields higher than in the other two assignments, indicating that the students assignment scores in Course 1 which have a wider variety of ICT and non-ICT teaching tools are higher than scores in Course 2 where students had to rely mostly on the data sites provided in class and invest effort to search further independently for statistical data to produce a good assignment. Similarly, scores in Course 3 were superior to those in Course 2, as in Course 3 independent search was needed aside from the course information, but it required less statistical data and more policy-based information than in Course 2, which are easier to evaluate and use at this educational level than statistical data. These differences in the competences used for the assignments may also explain the lower means of DC) and TOC scores and the higher mean of RIF score in Course 2, compared to the other courses.

Linear regressions of all ICTE-MM criteria as impacting variables on exams showed that for Course 1 CT was a significant predictor of the exam score (t = 2.5 p = .02) with F(6,22) = 12.455, p<.001, while all digital competences criteria explain 77% of the exam score.

Linear regressions of all ICTE-MM criteria as impacting variables on exams showed that for Course 2 DC was a significant predictor of the exam score (t = 2.95 p = .03) with F(6,6) = 5.842, p=.025, while all digital competences criteria explain 85% of the exam score.

There was no statistically significant result for linear regression tests between ICTE-MM criteria and exam scores for Course 3.

The digital maturity of the class (DMC) is medium to strongly negatively correlated with the assignment score and the RIF score in Course 1 and Course 3, and CC in Course 1 (

Table 6). These correlation relations are based on a small sample (N-10) for Course 1, and with N = 5 for Course 3, which reduces the relevance of the correlations, however, the fact that systematically students rated the author’s classes with a higher digital maturity that that of other classes or the institution as a whole is indicative that the interventions performed in these classes being noticeable and beyond the institution’s norms or average practices on the use of ICT tools in teaching. In the semi-structured interviews questions 8-9 asked the interviewees to evaluate the DMHEI and DMC from a scale from 1 to 5, 1 being the smallest rating. The average DMC was 4.36 (SD = .5) while the average DMHEI was 3.64 (SD = .71), indicated the included classes used more and/or more effectively ICT tools in teaching compared to other teachers from the HEI considered by students in their evaluations.

The digital maturity of the institution rated by the interviewed students is highly correlated with the digital maturity of the classes taught by the author, which indicates the reliance of the teaching methods and digital tools employed in class on the institution’s digital infrastructure, resources, and processes.

For Course 1 all the ICTE-MM criteria were medium to strongly and positively correlated with the exam score, all but one item at a high significance level (p<.001).

For Course 2 the CC, RIF, and Critical Thinking (CT) items were medium positively correlated with the exam score at a p<.05.

The figures for Course 3 show similar small-medium positive correlations with the exam scores in the same areas as Course 2, in addition to Creativity and Innovation (CI) item, also at a p<.05.

We extracted additional meaning regarding the teaching exercise involving ICT-tools form the content analysis of the qualitative data.

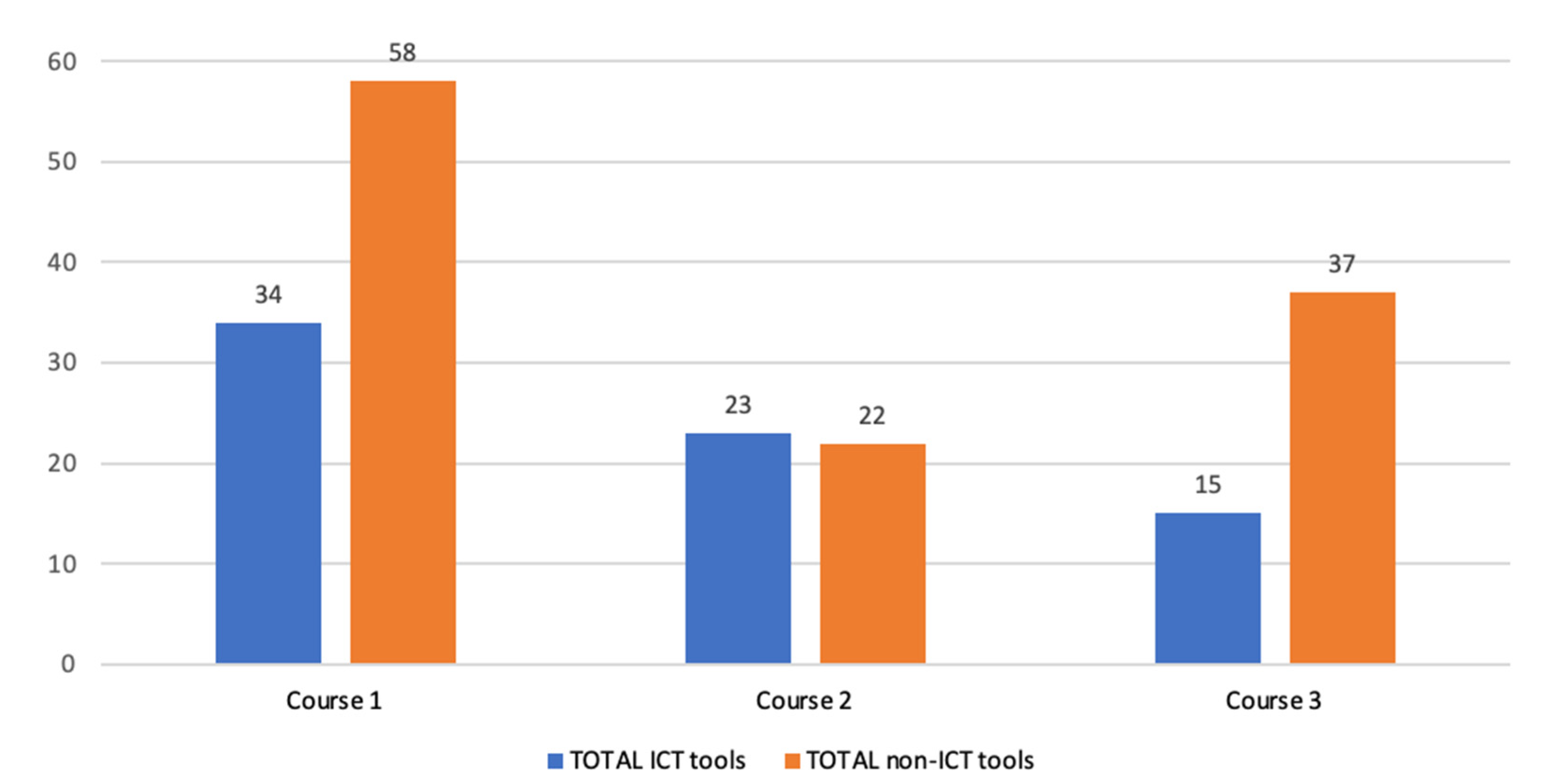

To address RQ3, using content analysis on the course feedback given after the oral examination, the frequency of occurrence of the methods used in teaching was recorded.

Figure 3. shows the split between ICT and non-ICT tools used in teaching that were mentioned in the course feedback by students.

As shown in

Figure 3 and

Table 7, reported in exam feedback, for Course 1 students mentioned almost twice more non-ICT tools than ICT tools as being helpful in their learning, by large the most memorable for students were debates, presentations, and the negotiation/voting simulation exercise (which made use of ICT tools - voting application but it was counted as non-ICT practical method). For Course 2 the difference between the two types was insignificant, with the most mentions counted for site links, debates, and other non-ICT.

For Course 3 the non-ICT tools mentioned were more than twice in number compared to the ICT tools, with the most mentioned received by Other non-ICT group, followed by debates.

4. Discussion

The interpretation of the quantitative results will be aided by the findings from the qualitative research. To reduce the teacher bias in evaluating the seminar assignments, all assignments submitted in the form of a presentation on a course topic were also separately assessed by a second teacher at the same HEI, and the evaluations were introduced in SPSS to calculate the coder agreement rate (Cohen’s Kappa score for the 16 criteria was between .707 and .946).

Supporting existing research [

26,

27,

51,

52], the results from the self-reported digital skills questionnaires and the students’ performance in the three courses show that self-perceived ICT competency and ICT used in teaching are positively linked to student’s performance in certain areas (Word processors, Email, and School IS). Additionally, the differences between the courses’ content were reflected in the type of assignments received and the information students needed to master in the oral exam for each of these courses. Therefore, with the same level of digital skills, as an average over the group, they handled these requirements best in Course 1 where ICT was most used and in more activities regardless of the fact that it consisted of fewer lectures and seminars, followed by Course 2 in which their strengths (Word processors, Email, Presentations, School IS) weighed more in the assignment and exam, compared to Course 3 where their gaps in skills (Statistical analysis and Academic DB search) weighted more for the course performance. The gender difference should also be noted, as even in developed countries female students appear to score higher on gender-stereotypical digital competences (communication-oriented), compared to investigative areas (scientific database search). Alternatively, the gender difference may only reflect the gender-stereotypical level of self-esteem [

8].

The medium-strong positive correlations between communication-based digital skills proficiency and assignment and/or exam scores in Course 1 and Course 3 suggests online and in-person communication were essential for students’ understanding, as well as being able to take notes and use them effectively later, clarify requirements with teachers and peers, and express their understanding, supporting the findings of prior research on the mediating role of ICT in teaching and on the benefits of a student-approach to teaching, compared to a teacher-approach [

10,

11,

29]. It may also suggest that the ability to locate study materials, information about class activities, and being able to submit one’s assignments according to requirements and on time, along with the ability to communicate with your teachers and peers for class purposes are similarly essential for their class performance. These findings also align with Waite [

23] that the use of ICT tools in teaching helps with the material comprehension. Students can effectively use these skills also if the institutional and class environment allow it, as part of the systemic influence of ICT tools effect on learning (cf. [

16,

26,

29,

33,

39,

40,

41]). As reported by students in qualitative feedbacks and semi-structure interviews, being able to pay attention to the teacher in class makes it less likely for them to get distracted by the digital tools used to take notes during class, which they can transfer in digital form at home, an aspect reported also by [

19,

24]. At the same time, effective use of digital communication in offline communication or online streaming benefits the students by helping them clarify information with teachers and peers quickly to absorb the material while still fresh.

The school IT infrastructure was also a contributing factor to students’ performance, as stipulated by Graham and Cullinan [

30,

58], which should be taken into consideration as a critical factor for the students’ academic performance especially in developing countries where the infrastructure is only developing. Policy makers must take note of the positive role of infrastructure in schools that provide opportunities for both students and teachers to access and use up-to-date and diverse materials and applications in learning and teaching. Having Wi-Fi connection in the school and on their devices, as well as a course online streaming platform, allow them also to search information instantaneously, connect to classes remotely and not miss as much as they would in the absence of those. Communication in person with the teacher was also mentioned as being refreshing in the school, which is a result of being a small-size HEI. In larger HEI classes, teachers are reported as “always on the move”, which hinders the effective personal teacher-student communication, which can make the students more receptive to the information. These factors are indicative of the positive effect of the synchronous social interaction with a teacher, and of role of exo and meso-system factors in the student’s performance, supporting the use of Bronfenbrenner’s ecological system theory when analysing the complex role of ICT in education (cf. [

13,

16,

27,

40,

51]).

Furthermore, as previously suggested by Alshmmary and Kim [

16,

17], the study showed that solely using more ICT tools does not always improve class performance, and the digitalisation of teaching and learning is a complex environment containing from institutional policies towards ICT adoption, teacher’s pedagogical and ICT skills, and student’s own motivation to learn (cf. [

4,

8,

11,

16,

27,

51]). This complex picture is revealed when ICT tools are used in a wider range of and diverse activities, including practical exercises, which make use of the students’ digital skills strengths. In these situations, we observed an increase in students’ class performance. Courses 2 and 3 had the same range of ICT-tools used in class and required in seminar assignments, yet the differences in the type of digital skills used made the difference between the scores they received in seminar assignments. Moreover, the ICT-tools used in class in Course 2 additional to the students’ own digital skills seem to have impacted their Digital Citizenship score making it a reliable predictor for the exam score. In Course 1 though Critical Thinking was found to be a reliable predictor for the exam score, indicating that perhaps the larger range of ICT and non-ICT tools used in teaching increased the student’s ability to effectively evaluate and integrate information and perform better in the exam. The findings, however, indicate that students cannot consistently transfer digital skills to different domains, suggesting they do not have mature digital competences, and supporting the studies of Simons and Souders [

21,

22].

Our study found that for each course different ICTE-MM competences were found for correlate strongly and positively with the exam score, indicating that the assignments and the exams required more from the students than memorizing facts and figures, such as critical thinking, communication skills, and research fluency. Also, they may suggest that the more, and more diverse, ICT and non-ICT tools were used in class, the more of those ICTE-maturity model (ICTE-MM) key areas were used by students in class and exam, supporting the research that showed positive effects between ICT in teaching and student’s developed abilities (cf. [

16,

27,

52]). Additionally, more non-ICT tools being mentioned in Course 1 and 3 and as being useful in their overall learning with students evaluating positively the role of class dynamic, teachers’ approach to communication. We can infer from the data from this case study, that, ICT-tools can help develop skills and increase class performance in students, but only in corroboration with a good teacher-student communication (ICT-mediated or in-person) and appropriate pedagogical skills.

Furthermore, the field of the HEI is important for the range of ICT tools that can be employed to convey the subject matter to students, and, similarly, to attract teaching and non-teaching staff that are capable to innovate the school’s activity by incorporating more ICT tools. Tegmark in

The mathematical universe hypothesis [

53] proposes that the further we go towards social sciences, the more interpretative language we use to explain the field’s subject matter, as opposed to objective mathematical structures. Thus, the range of ICT tools used in education for natural science fields (drill and practice programs, tutoring system, intelligent tutoring systems, simulations, hypermedia systems) is broader than for social sciences, where teachers can generally aim at most to use ICT to engage students in social and civic activities discussed and critically debated in-person or using ICT for information search [

54,

56]. As a consequence, in social sciences, a HEI’s the range of ICT tools in teaching is reduced mostly to digitally stored interpretative content (e.g. hypermedia systems, presentations, videos, pictures, etc), and has less available algorithm-based data/information (e.g. interactive graphs, live maps, simulations, etc.). Thus, the HEI size and its non-technical field constitute influential factors in formally and consistently adopting (or delaying the adoption) of ICT in teaching, infrastructure, and school administration activities, which supports the findings of prior research [

55,

56,

57]. The pedagogical interventions in the three classes included in this study were noticeable to students precisely because they introduced ICT in a manner and number that differed from the HEI norms and average practices, which, due to its novelty in the field, could have contributed to a higher engagement of the students in classes.

All these findings can be useful for teachers in developing countries that implement UN SDGs programs in the fields of education and technology improvement. There is a parallel that can be drawn between educational institutions or programs (such as social sciences) from developed countries with low implementation of technology-based teaching tools and methods and newly built educational institutions in developing countries that are slowly implementing ICT infrastructure and skills in teaching any type of subjects. Both sides of this comparison rely on (incipient) technical skills of students and teachers, as well as on an infrastructure that may not be accessible by all students alike and usable for each subject to the same degree [

58,

59]. Thus, the role of the teacher adjusting the teaching material and methods to make the best use of the student’s skills remains crucial to the academic performance of their students, in order to increase their competences in a growingly more technologized world.

A more unusual finding was the negative strong correlation between the DMC and ICTE-MM competencies in Course 1 and Course 3. While it is difficult to reliably interpret these findings not knowing how students understand the concept of digital maturity and due to the small sample, they may roughly suggest that students with higher than average digital skills also have higher expectations from the institution’s and class’s DM, leading to lower ratings for the school and class compared to their own skills; similarly, students than lower average digital skills also have lower expectations from the institution’s and class’s DM, leading to higher ratings for the school and class compared to their own skills. In other words, students compare the institution and class’s digital skills with their own digital skills. These inferences are based also on the results of the DM rating for the school, as evaluated by the managerial, administrative, academic and IT staff. The managerial, administrative and teaching staff mirror the estimates of students in the included classes, overestimating the DM of the HEI compared to the results based on qualitative data (interviews, observations and assessments) collected by the researcher. However, the IT department estimated the DM of the HEI as being at the same level as the inferred by the researcher from additional qualitative data, which were not included in the results here. It is important to mention this aspect, as the digital skills and competences of the evaluator have a clear influence on the evaluation of the DM of the HEI and classes, with these two levels of competences (the evaluator’s and the HEI/class’s) seemingly going in opposite directions for evaluator of a non-technical expertise (e.g. the administrative staff compared to the IT staff).

In an integrative manner using the ecological system theory, we can interpret the findings from all these sources as the interaction between the students’ micro system and the teacher’s micro system through their own digital skills, communication skills, and pedagogical skills (only teacher), within the meso and macro system offered by the infrastructure and processes established at the HEI level. These interactions give rise to the proximal processes which can nurture or hinder the student’s learning activity and their academic performance (cf. [

40,

41]). Thus, evaluating in isolation the ICT tools used in teaching cannot offer an accurate image of what factors influence students’ performance; an integrated evaluation of ICT, non-ICT tools, and students’ and teachers’ skills and competences provides a more accurate image of the role of ICT in HEI, especially when the subject matter is dynamic and prone to interpretation, as it is the case with specific fields of social sciences (cf. [

8,

25,

38,

39]). It is also important to look at this topic, and not only, in a systemic manner, as we integrate more skills and competences into our human activity to meet sustainable development goals that were set only in the last three decades and which we will need to constantly (re)evaluate and adapt in a reliable and realistic manner.

5. Limitations

The study’s limitations are related to the sample size, of only 45 individuals, and using self-reports, which we attempted to overcome with the triangulation of data on students’ performance and digital skills and included multiple measured on overlapping groups of students. In future research we attempt to use a larger student sample, include more courses from social sciences as data sources and compare the students’ performance with that of control groups of students in classes taught by teachers using only conservative teaching methods.

6. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the integration of ICT in social sciences education is a nuanced process that significantly influences students’ academic performance, but its impact is closely tied to the context in which it is used. The research shows that while ICT tools can enhance learning, their effectiveness depends on how well they are integrated with traditional teaching methods and how they align with students' existing digital skills. The study confirms that the role of the teacher remains crucial, not just in guiding the use of technology, but in maintaining a balance between digital and non-digital teaching strategies to optimize learning outcomes.

The findings also suggest that the field of study (social sciences in this case) and the institutional environment significantly influence the adoption and success of ICT in education. Students benefit most when ICT tools are used in a manner that complements their learning styles and when teachers are adept at blending these tools with traditional methods. This research underscores the importance of developing a more integrated and flexible approach to ICT in education, one that considers the complex interplay between technology, pedagogy, and student capabilities.

Future research should focus on expanding the sample size, including more courses, and comparing results across different types of educational institutions. Such studies could further clarify the relationship between ICT use and academic performance, providing more generalizable insights that could inform educational policy and practice in a variety of contexts, and particularly for sustainable goals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.M. and M.M.; methodology, E.M. and M.M.; validation, E.M., T.K. and M.M.; formal analysis, M.M.; investigation, M.M.; resources, M.M. and E.M.; data curation, M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, E.M. and M.M.; writing—review and editing, E.M., M.M. and T.K.; visualization, M.M.; supervision, E.M.; project administration, E.M.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study, as described in the section on the study procedure.

Data Availability Statement

Due to the confidentiality of the data collected from the HE institution, the data are not readily available for other purposes than the scope of the research study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CC |

Communication and Collaboration |

| CI |

Creativity and Innovation |

| CT |

Critical Thinking |

| DC |

Digital Citizenship |

| DM |

Digital Maturity |

| DMC |

Digital Maturity of the Class |

| DMHEI |

Digital Maturity of the HEI |

| ECDL |

European Computer Driving License |

| EU |

European Union |

| HE |

Higher Education |

| HEI |

Higher Education Institution |

| ICT |

Information and Communication Technology |

| ICTE |

Information and Communication Technology in Education |

| ICTE-MM |

ICTE- Maturity Model |

| IS |

Information System |

| ISTE |

International Society for Technology in Education |

| PISA |

Programme for International Student Assessment |

| RIF |

Research and Information Fluency |

| SDGs |

Sustainable Development Goals |

| TOC |

Technology Operations and Concepts |

| UN |

United Nations |

| UNESCO |

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation |

References

- Kline, R. R. Cybernetics, management science, and technology policy: The emergence of "Information Technology" as a keyword, 1948-1985. Technology and Culture 2006, 47(3), pp. 513-535. [CrossRef]

- Spariosu, M. I. Information and communication technology for human development: An intercultural perspective. In Remapping knowledge: Intercultural studies for a global age 2006, pp. 95-142. Berghahn Books. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv3znztw.

- Haddad, C. R., Nakić, V., Bergek, A., & Hellsmark, H. Transformative innovation policy: A systematic review. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 2022, 43, pp. 14-40. [CrossRef]

- Suchitwarasan, C., Cinar, E., Simms, C., & Demircioglu, M. A. Innovation for sustainable development goals: A comparative study of the obstacles and tactics in public organizations. The Journal of Technology Transfer 2024, 49(6), pp. 2234-2259. [CrossRef]

- Hinkley, S. Technology in the public sector and the future of government work. UC Berkeley Labor Center (2023, January 10). https://laborcenter.berkeley.edu/technology-in-the-public-sector-and-the-future-of-government-work/.

- TU. Measuring digital development: Facts and figures 2022. International Telecommunication Union. (2022) https://www.itu.int/itu-d/reports/statistics/facts-figures-2022/.

- Chandi, F. O. ICT in education: Possibilities and challenges. Universitat Oberta De Catalunya. (2004, October) https://www.academia.edu/1006536/ICT_in_education_Possibilities_and_challenges?auto=citations&from=cover_page.

- Timotheou, S. , Miliou, O., Dimitriadis, Y., Sobrino, S. V., Giannoutsou, N., Cachia, R., Monés, A. M., & Ioannou, A. Impacts of digital technologies on education and factors influencing schools' digital capacity and transformation: A literature review. Education and Information Technologies 2022, 28, 6695–6726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garnham, N. Information society theory as ideology: A critique. Loisir et Société / Society and Leisure 1998, 21(1), pp. 97-120. [CrossRef]

- Islam, M. K. , Sarker, M. F., & Islam, M. S. Promoting student-centred blended learning in higher education: A model. E-Learning and Digital Media 2021, 19, 36–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedi, E. A. Tensions between technology integration practices of teachers and ICT in education policy expectations: Implications for change in teacher knowledge, beliefs and teaching practices. Journal of Computers in Education 2023, 11, 1215–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Gutiérrez, M. , Gimenez, G., & Calero, J. Is the use of ICT in education leading to higher student outcomes? Analysis from the Spanish autonomous communities. Computers & Education 2020, 157, pp–103969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L. Thinking and speech. 1962. https://www.marxists.org/archive/vygotsky/works/words/Thinking-and-Speech.pdf.

- Tsalapatas, H. Programming games for logical thinking. EAI Endorsed Transactions on Game-Based Learning 2013, 1(1), pp. e4. [CrossRef]

- Harel, I.; Papert, S. Constructionism. 1991, Ablex Publishing Corporation.

- Alshammary, F. M., & Alhalafawy, W. S. Digital platforms and the improvement of learning outcomes: Evidence extracted from meta-analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15(2), pp. 1305. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Chung, K.; Yu, H. Enhancing digital fluency through a training program for creative problem solving using computer programming. The Journal of Creative Behavior 2013, 47(3), pp. 171-199. [CrossRef]

- Fatmi, N., Muhammad, I., Muliana, M., & Nasrah, S. The utilization of Moodle-based learning management system (LMS) in learning mathematics and physics to students’ cognitive learning outcomes. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Studies 2021, 3(2), pp. 155. [CrossRef]

- Warsi, L. Q. , Rahman, U., & Nawaz, H. Exploring influence of technology distraction on students' academic performance. Human Nature Journal of Social Sciences 2024, 5, 317–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepa, V. , Sujatha, R., & Baber, H. Moderating role of attention control in the relationship between academic distraction and performance. Higher Learning Research Communications 2022, 12, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, D. J.; Boot, W. R.; Charness, N.; Gathercole, S. E.; Chabris, C. F.; Hambrick, D. Z.; Stine-Morrow, E. A. Do “brain-training” programs work? Psychological Science in the Public Interest 2016, 17(3), pp. 103-186. [CrossRef]

- Souders, D. J.; Boot, W. R.; Blocker, K.; Vitale, T.; Roque, N. A.; Charness, N. Evidence for narrow transfer after short-term cognitive training in older adults. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 2017, 9, pp. 41-50. [CrossRef]

- Waite, B. M.; Lindberg, R.; Ernst, B.; Bowman, L. L.; Levine, L. E. Off-task multitasking, note-taking, and lower- and higher-order classroom learning. Computers & Education 2018, 120, pp. 98-111. [CrossRef]

- Dontre, A. J. The influence of technology on academic distraction: A review. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies 2020, 3, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvati, S. Use of digital technologies in education: The complexity of teachers’ everyday practice (2016, Doctoral dissertation, Linnaeus University, Växjö, Sweden). https://lnu.divaportal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1039657&dswid=2143.

- Park, S.; Weng, W. The relationship between ICT-related factors and student academic achievement and the moderating effect of country economic indexes across 39 countries: Using multilevel structural equation modelling. Educational Technology & Society 2020, 23(3), pp. 1-15. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/26926422.

- Ben Youssef, A. , Dahmani, M., & Ragni, L. ICT use, digital skills and students’ academic performance: Exploring the digital divide. Information 2022, 13, 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, H.; Ali, I.; Khan, M. A.; Hamid, K. A study of university students’ motivation and its relationship with their academic performance. Int. Journal of Bussiness and Management 2010, 5(4), pp. 80-88. [CrossRef]

- Bice, H. , & Tang, H. Teachers’ beliefs and practices of technology integration at a school for students with dyslexia: A mixed methods study. Education and Information Technologies 2022, 27, 10179–10205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, M. A.; Stols, G.; Kapp, R. Teacher practice and integration of ICT: Why are or aren’t South African teachers using ICTs in their classrooms? International Journal of Instruction 2020,13(2), pp. 749-766. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. , Tigelaar, D. E., & Admiraal, W. From policy to practice: Integrating ICT in Chinese rural schools. Technology, Pedagogy and Education 2022, 31, 509–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, O. , & Ropo, E. Preparing student teachers to teach with technology: Case studies in Finland and Israel. International Journal on Integrating Technology in Education 2021, 10, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skryabin, M.; Zhang, J.; Liu, L.; Zhang, D. How the ICT development level and usage influence student achievement in reading, mathematics, and science. Computers & Education 2015, 85, pp. 49-58. [CrossRef]

- The Earth Institute, Columbia University; Ericsson. ICT and education. Sustainable Development Solutions Network. (2016) http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep15879.11.

- United Nations. Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. (2015, September 25). https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda. 25 September.

- United Nations. SDG 4: Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all. United Nations. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Sustainable Development. (2023). https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal4#targets_and_indicators.

- Hu, X., Gong, Y., Lai, C., & Leung, F. K. (2018). The relationship between ICT and student literacy in mathematics, reading, and science across 44 countries: A multilevel analysis. Computers & Education 2018, 125, pp. 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Begicevic Redjep, N.; Balaban, I.; Zugec, B. Assessing digital maturity of schools: Framework and instrument. Technology, Pedagogy and Education 2021, 30(1-5), pp. 643-658. [CrossRef]

- Gibson, D.; Broadley, T.; Downie, J.; Wallet, P. Evolving learning paradigms: Re-setting baselines and collection methods of information and communication technology in education statistics. Journal of Educational Technology & Society 2018, 21(2), pp. 62-73.

- Rosa, E. M.; Tudge, J. Urie Bronfenbrenner's theory of human development: Its evolution from ecology to bioecology. Journal of Family Theory & Review 2013, 5(4), pp. 243-258. [CrossRef]

- Edwards, S.; Henderson, M.; Gronn, D.; Scott, A.; Mirkhil, M. Digital disconnect or digital difference? A socio-ecological perspective on young children’s technology use in the home and the early childhood centre. Technology, Pedagogy and Education 2016, 26(1), pp. 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.; Grudziecki, J. DigEuLit: Concepts and tools for digital literacy development. Innovation in Teaching and Learning in Information and Computer Sciences 2006, 5(4), pp. 249-267. [CrossRef]

- Eshet, Y. Digital literacy: A conceptual framework for survival skills in the digital era. Journal of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia 2004, 13(1), pp. 93-106. https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/4793/.

- Aviram, A.; Eshet-Alkalai, Y. Towards a theory of digital literacy: Three scenarios for the next steps. European Journal of Open, Distance and eLearning 2006, 1, pp. 1-11. http://www.eurodl.org/index.php?p=archives&year=2006&halfyear=1.

- Van Deursen, A.; Van Dijk, J. Measuring digital skills. Paper presented at the 58th Conference of the International Communication Association, Montreal, Canada. (2008, May) https://www.utwente.nl/nl/bms/com/bestanden/ICA2008.pdf.

- Helsper, E. J.; Eynon, R. Distinct skill pathways to digital engagement. European Journal of Communication 2013, 28(6), pp. 696-713. [CrossRef]

- Volungevičienė, A.; Brown, M.; Greenspon, R.; Gaebel, M.; Morrisroe, A. Developing a high-performance digital education ecosystem: Institutional self-assessment instruments. European University Association absl. (2021) https://eua.eu/downloads/publications/digi-he%20desk%20research%20report.pdf.

- Solar, M.; Sabattin, J.; Parada, V. A maturity model for assessing the use of ICT in school education. Journal of Educational Technology & Society 2013, 16(1), pp/ 206-218. http://www.jstor.org/stable/jeductechsoci.16.1.206.

- ISTE. (n.d.). ISTE standards. International Society for Technology in Education. Retrieved August 2022, from https://www.iste.org/iste-standards.

- ECDL. (n.d.). International certification of digital literacy. European / International Certification of Digital Literacy and Digital Skills. Retrieved February 2023, from https://ecdl.cz/o_projektu.php.

- Rahman, A.; Rahman, F. M. Knowledge, attitude and practice of ICT use in teaching and learning: In the context of Bangladeshi tertiary education. International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) 2015, 4(12), pp. 755-760. [CrossRef]

- Hsin, C. T.; Li, M. C.; Tsai, C. C. The influence of young children's use of technology on their learning: A review. Journal of Educational Technology & Society 2014, 17(4), pp. 85-99.

- Tegmark, M. The mathematical universe. Foundations of Physics 2007, 38, pp. 101-150. [CrossRef]

- Hillmayr, D.; Ziernwald, L.; Reinhold, F.; Hofer, S. I.; Reiss, K. M. The potential of digital tools to enhance mathematics and science learning in secondary schools: A context-specific meta-analysis. Computers & Education 2020, 153, pp. 103897-103921. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, P. D.; Bombardelli, O. Editorial: Digital tools and social science education. Journal of Social Science Education 2016, 15(1), pp. 1-4. [CrossRef]

- Langan, D., Schott, N., Wykes, T., Szeto, J., Kolpin, S., Lopez, C., & Smith, N. Students’ use of personal technologies in the university classroom: Analysing the perceptions of the digital generation. Technology, Pedagogy and Education 2016, 25(1), pp. 101-117. [CrossRef]

- Zubković, B. R. , Pahljina-Reinić, R., & Kolić-Vehovec, S. Predictors of ICT use in teaching in different educational domains. Humanities Today: Proceedings 2022, 1, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullinan, J., Flannery, D., Harold, J., Lyons, S., & Palcic, D. The disconnected: COVID-19 and disparities in access to quality broadband for higher education students. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 2021, 18(1). [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, R. M. Impact of ICT on education: Challenges and perspectives. Propósitos y Representaciones 2017, 5(1), pp. 325. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).