1. Introduction

Metamaterials and metasurfaces have been widely recognized as transformative platforms for controlling electromagnetic waves [

1,

2,

3]. These advanced materials utilize subwavelength structures to achieve remarkable electromagnetic properties, such as negative refraction, flat lensing and perfect light absorption and [

4,

5,

6]. By engineering their composition at the nanoscale, these systems enable accurate control over the amplitude, phase, and polarization of light [

7]. Depending on their dimensionality (i.e., 1D, 2D or 3D), these periodic structures provide compact solutions for manipulating light-matter interactions [

8,

9,

10].

The realization of such advanced materials relies on several physical concepts such as effective medium theory (EMT) [

11], lattice resonances [

12], particle scattering resonances [

13], and surface plasmon effects [

14]. EMT uses macroscopic effects from complex subwavelength interactions, which generates extraordinary properties such as negative refractive indices or anisotropic behavior [

11,

15]. Lattice resonances, namely guided-mode resonances (GMRs), arise from the coupling of guided resonances with diffracted waves in periodic arrays [

16,

17]. These periodic structures exhibit diverse spectral responses with high quality factor (high-Q) resonances, which enable them highly desirable for wavelength-selective photonic devices [

18]. Additionally, particle scattering resonances driven by electric or magnetic dipoles in individual structures facilitate strong light-matter interactions and related phenomena [

13,

19].

Recently, among various mechanisms, the concept of bound state in the continuum (BIC) has attracted significant attention in metasurface research, which are non-radiative states embedded within resonance modes under perfect symmetry condition [

20,

21]. By controlling symmetrical breaking such as off-normal incidence or structural asymmetry, BICs can transition into radiative modes known as quasi-BICs, which shows a great potential for innovative devices including narrowband filtering, optical switching, and biosensing [

22,

23,

24]. Recent advancements have revealed a new type of resonance in photonic lattices (PLs), where strong resonances radiate immediately at isolated spectral positions from adjacent bands when symmetry is broken. This phenomenon, known as the singular state, represents the realization of quasi-BIC and is explained through asymmetric guided-mode resonances (aGMRs) [

25].

In this work, we present a novel method for dynamically tuning singular states by employing PLs with air-slit-based structural modifications. This approach enables effective control over resonance positions and dual functionalities, including narrowband reflection and notch filtering. Furthermore, the introduction of multiple air-slits demonstrates that increasing asymmetry significantly enhances spectral tunability by inducing multiple folding behavior in the resonance bands. These tunable singular states show great potential for designing multifunctional photonic devices.

2. Air Slit Induced Singular States

To investigate tunable singular states, we broke the symmetry of a simple one-dimensional (1D) photonic lattice (PL) by incorporating an air-slit.

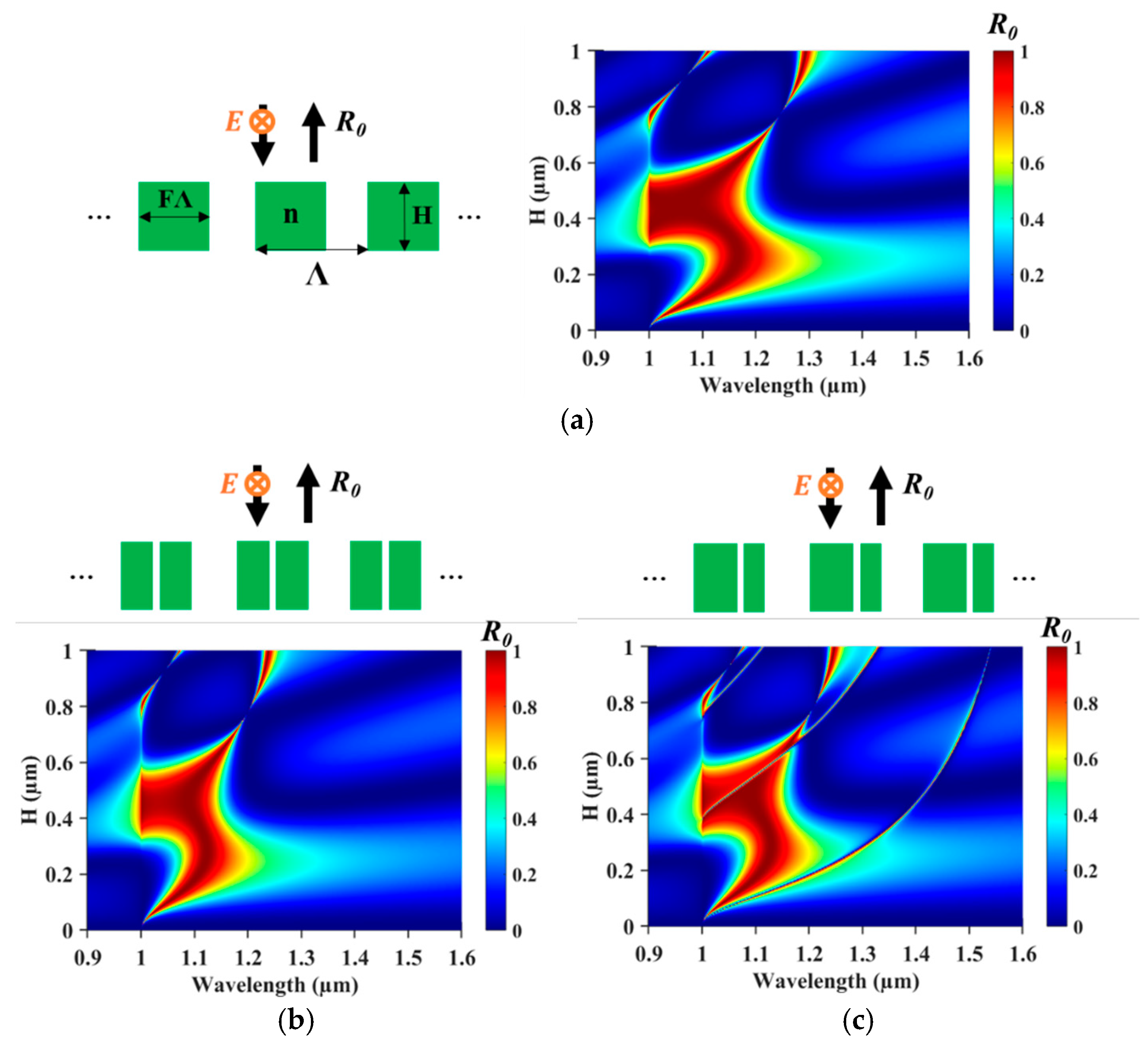

Figure 1a illustrates the 1D resonant structure, defined by grating parameters such as period (Λ), fill factor (F), and grating height (H) with refractive index (n). Continuing the study of singular states, we employed the previous design of the 1D PL [

26] where the grating parameter set is {

= 1 µm,

= 0.5,

= 0.5 µm} with a lossless material (

= 2). In this study, we characterized the zeroth-order reflectance (

) using the rigorous coupled-wave analysis (RCWA) [

27] method implemented in commercial software [

28]. The analysis is performed with TE-polarized light (electric field parallel to the grating grooves) illuminating the 1D PL at normal incidence in the air (

= 1). As shown in calculated

map of

Figure 1a, wideband perfect reflection is observed in the spectral region due to the resonant radiation, which has been understood by the guided mode resonance (GMR) phenomenon [

16]. As the height (

) increases, additional resonance bands are generated by excitation of higher GMR modes.

Figure 1b presents the case where an air-slit with a width of 0.05 µm is introduced at the center of the grating, preserving the structural symmetry. The

map shows resonance bands like those observed without the air-slit (i.e.,

Figure 1a) but only a slight narrowing observed. This narrowing can be attributed to the effective refractive index reduction due to the presence of air. In contrast, the resonance band is significantly changed when the symmetry is broken by shifting the air-slit.

Figure 1c shows the

map of the 1D PL with air slit displaced 0.05 µm from the center. The asymmetry of the 1D PL leads to the formation of a sharp band, which can be interpreted as an off-BIC (bound state in continuum) [

20] or asymmetric GMR [

25]. Observed in the asymmetric system, these resonance bands can be classified as asymmetric guided-mode resonance (aGMR) modes owing to their origin in asymmetric excitation of GMR modes. Notably, shown in the

map, the fundamental aGMR mode manifests as a singular state, distinctly separated from the other resonance bands. This singular state will be shown to be tunable through manipulation of the air slit.

3. Interpretation of Singular States

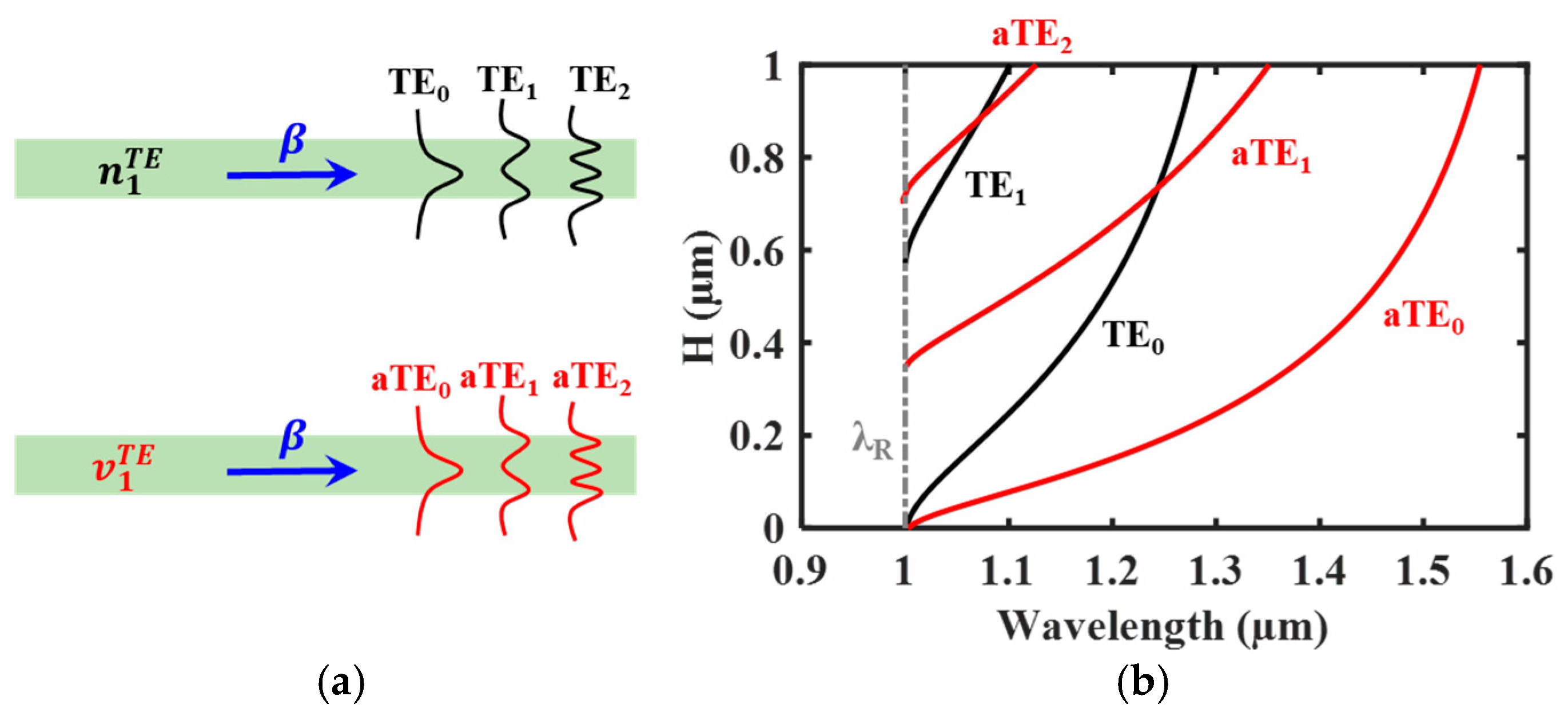

Singular states can be interpreted by analyzing the slab waveguide modes of an equivalent 1D PL. As depicted in

Figure 2a, the 1D PL can be approximated as a slab waveguide where electromagnetic fields are confined through the coupling of diffracted waves to a propagation constant (

). For this equivalent slab waveguide, the 1D grating layer is homogenized using effective medium theory (EMT) with the Rytov’s formalism [

29]. The effective refractive indices (

and

) are determined by the

mth order solutions from the following equations [

29,

30]:

Here, the

and

represent the symmetric and asymmetric field EMT solutions from each equation (1) and (2). Considering the first diffraction waves, we apply the first solution

and

for slab waveguide analysis. The eigenvalue problem of the

lth TE mode of slab waveguide can be expressed as [

25,

31]:

where the

and

are vertical propagation vectors of first-order diffracted waves and propagation constant (

) in vacuum, respectively. Based on the different EMT solutions (

and

), the

is given by

or

. The

represents the propagation constant of the guided mode, assuming coupled from the first-order grating vector (

). Consequently, the

lth TE guided modes (

or

) are obtained as eigen-solutions using symmetric and asymmetric effective refractive indices.

Figure 2b displays the calculated

or

modes, which matches the resonance bands observed in the asymmetric air slit 1D PL in

Figure 1c. Indeed, the singular state originates from the

, indicating the fundamental guided mode of asymmetric EMT slab coupled by first-order diffracted waves.

4. Analysis of Air Slit-Induced Singular States

To characterize the

mode of the singular state, we analyze the electric field profiles at specific points on the

spectra of both the symmetric and asymmetric air-slit 1D PLs, as depicted in

Figure 2b and

Figure 2c.

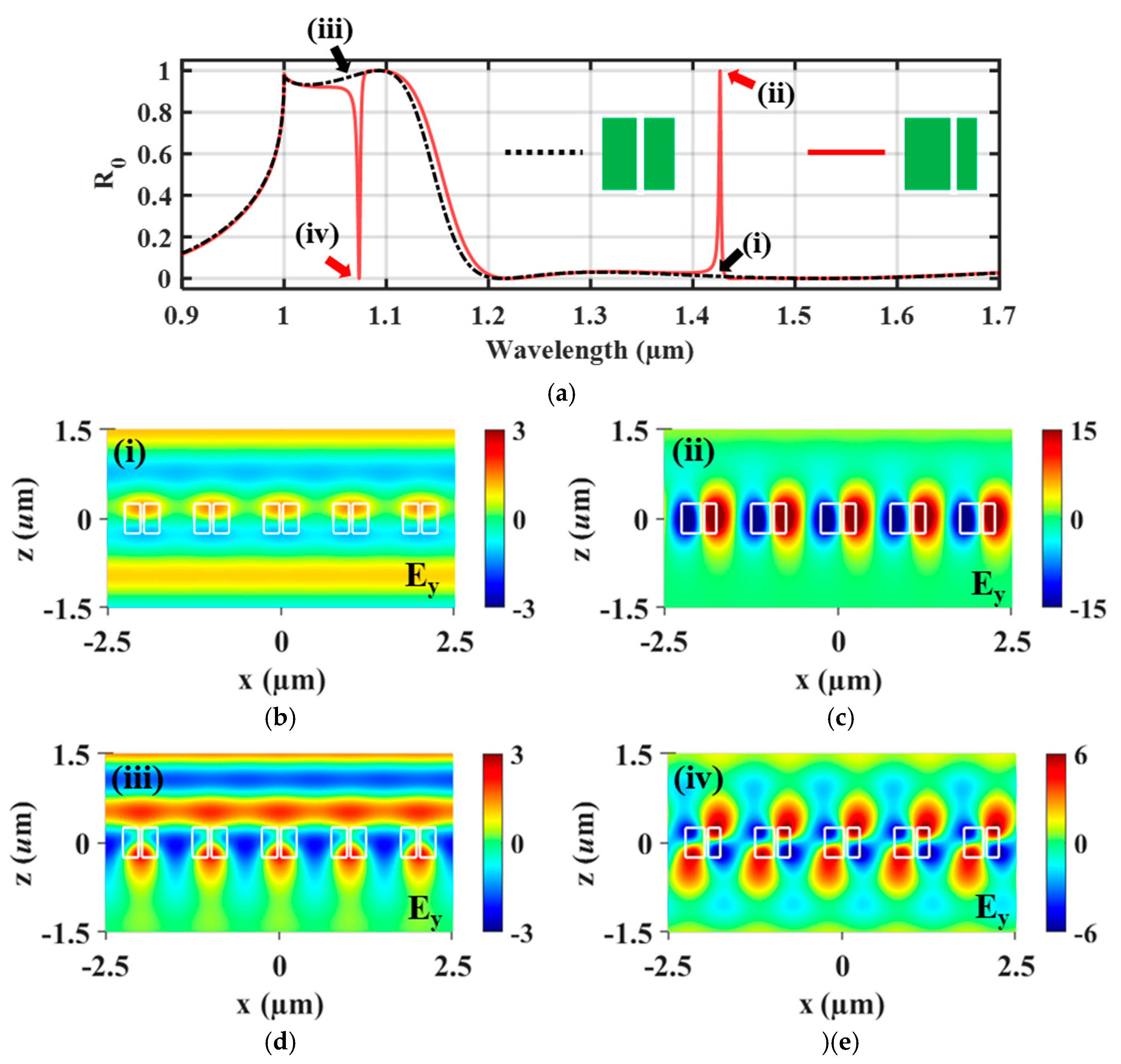

Figure 3a shows these points (i)-(iv) on the

spectra for the air slit 1D PLs. In contrast to point (i) on the spectrum of the symmetric air-slit 1D PL (black dash line), the point (ii) on the asymmetric air-slit 1D PL (red solid line) spectrum exhibits a sharp resonance peak at λ=1.4266 µm, associated with a singular state. In shorter wavelength region, the point (iii) corresponds high reflection while point (iv) shows a sharp dip at

=1.0734 µm. The electric field distributions (

, as out of plane) corresponding to these points are presented in

Figure 3b to 3e. As shown in

Figure 3b, the light propagates through the 1D PL without resonance. In

Figure 3c, however, the light is strongly confined to the lattice with asymmetric air-slit. This

profile represents the singular state, formed by the fundamental guided modes (i.e.,

). In

Figure 3d, the light is highly reflected from the symmetric air-slit 1D PL. Conversely, in

Figure 3e, it passes through in the asymmetric air-slit 1D PL due to interaction with enhanced

field, forming the first guided modes (i.e.,

).

5. Tunable Singular States by Asymmetric Air-Slit 1D Lattice

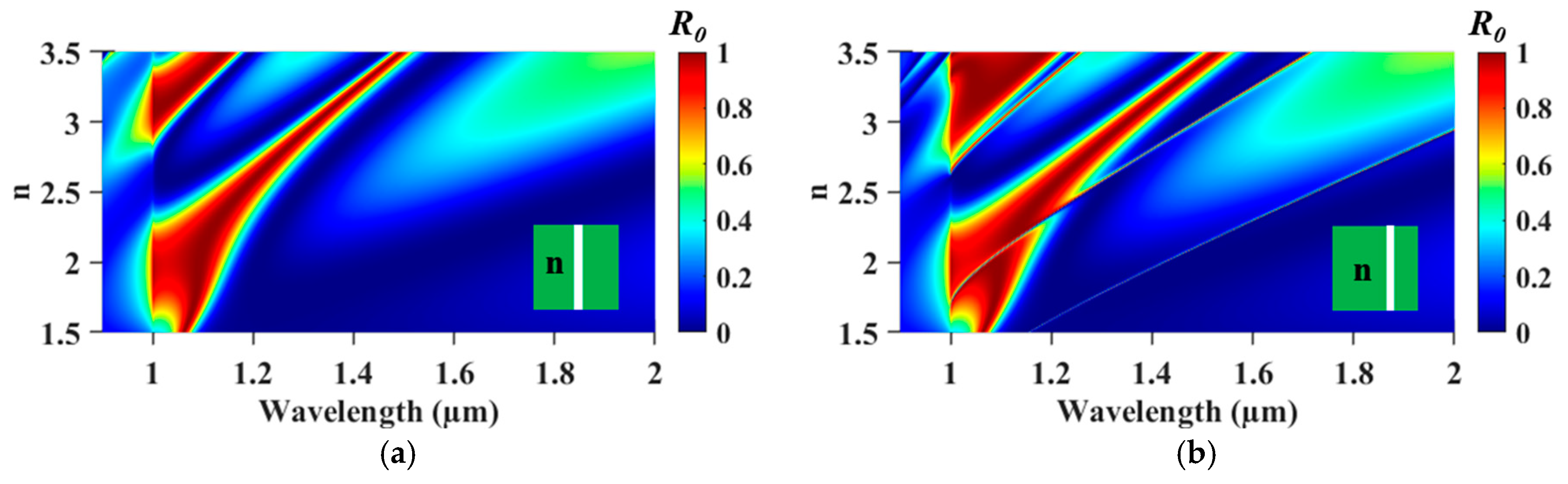

Prior to designing tunable singular states, we examine the refractive index (

) effects on the singular state in the asymmetric air-slit 1D PL.

Figure 4a presents the

map for the symmetric air-slit 1D PL where the spectral response is calculated by varying the

from 1.5 to 3.5. As observed, two resonance bands shift toward longer wavelengths as

increases. This red shift is a characteristic behavior of GMRs as higher

increases a propagation constant of guided mode.

Figure 4b shows the corresponding

map for the asymmetric air-slit case under the same refractive index variations. As expected, sharp resonance bands appear and exhibit a red shift. Notably, the singular state becomes increasingly isolated from the other resonance bands for higher refractive index material as silicon nitride (Si

3N

4, n ≈ 2) and silicon (Si, n ≈ 3.5).

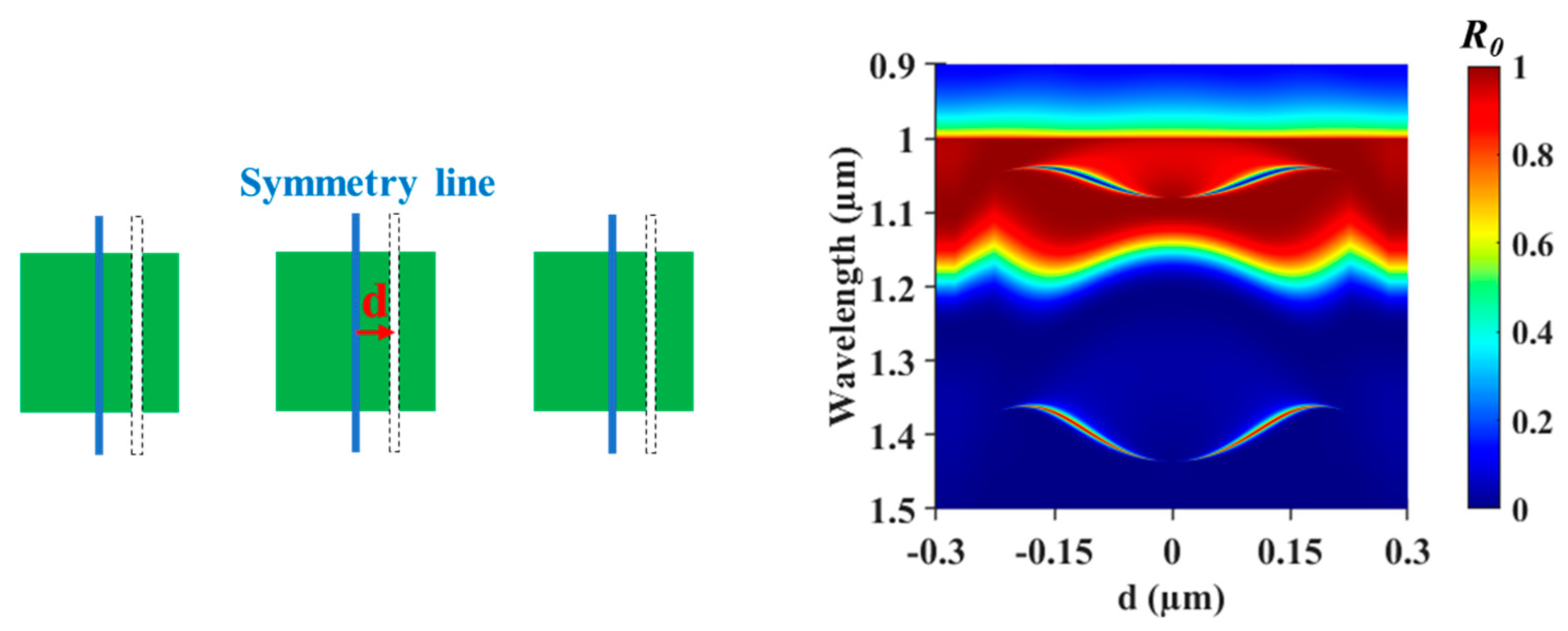

The aGMR enables the generation of tunable singular state by varying asymmetry of the air-slit 1D PL.

Figure 5 shows the tunable singular state in an air-slit 1D PL based on a dielectric material (

=2), where the grating parameter set is {

= 1 µm,

= 0.5,

= 0.5 µm}. As illustrated in the schematic of

Figure 5, a single air-slit with a width of 0.05 µm is displaced by a distance

from the symmetric line. In the

map of the asymmetric air-slit 1D PL, two sharp resonances are observed due to the aGMRs. The lower peak corresponds to the

mode, while the upper dip represents the

mode. These modes arise from the interference between leaky waveguide modes and background radiation, as a phenomenon characteristic of Fano resonances [

32]. At the low reflection region, the

peak can be used as a notch filter. In contrast, the

dip around the high reflection band for band pass filter. When the

gradually increases from zero to

0.15 µm, these dual functionalities can be simultaneously tuned by varying the

.

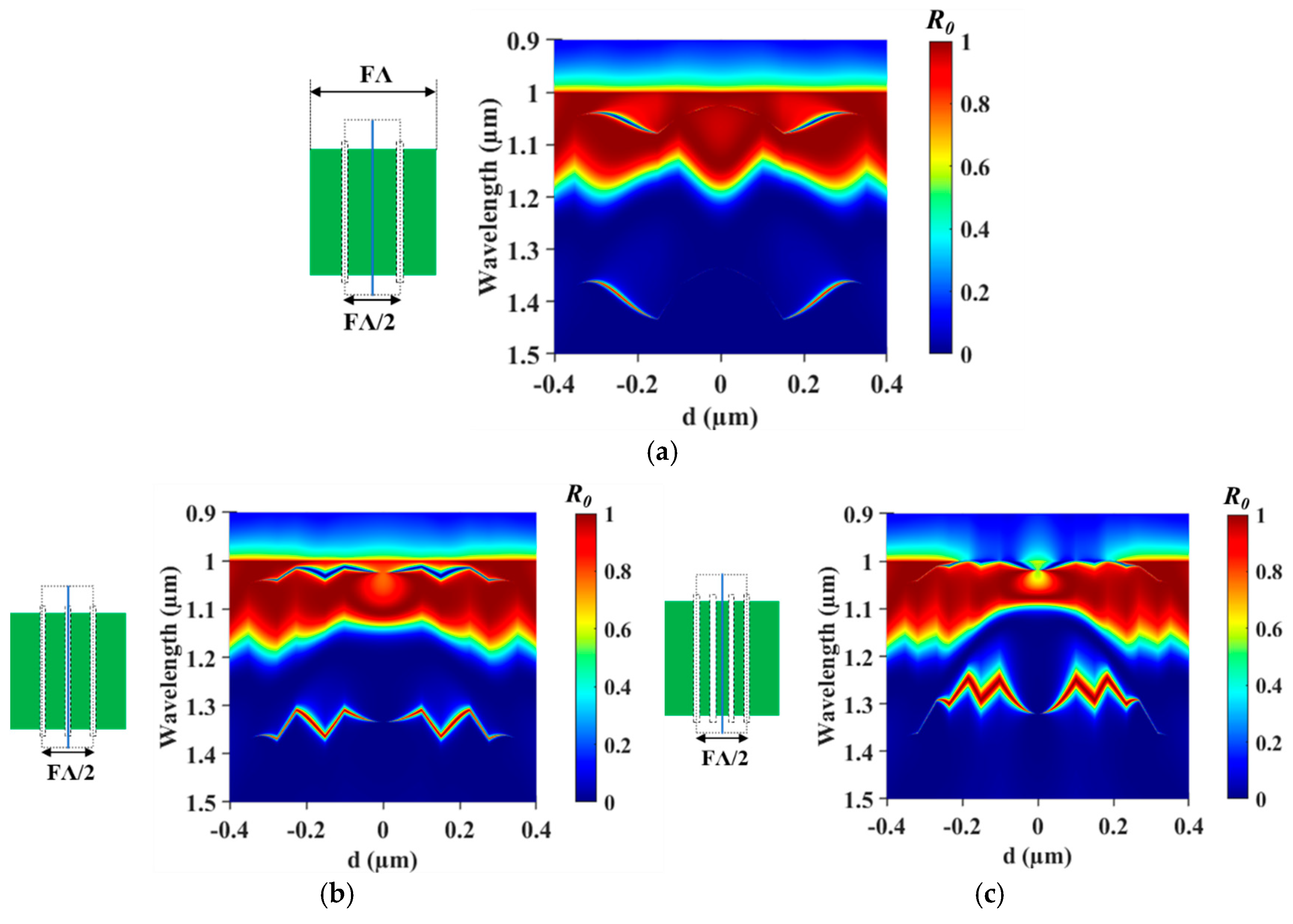

This dual functionality becomes even more dynamic with the introduction of multiple air-slits. As shown in the schematic of

Figure 6a, two air-slits are aligned with a pitch width of

=0.25 μm. By varying the displacement

from zero to

0.35 μm, as seen in

map of

Figure 6b, the two sharp aGMRs are rapidly tuned. This behavior corresponds to the one-fold radiation observed in the single air-slit case of

Figure 5. Using triple and quadruple air-slits, the aGMRs exhibit even faster tuning due to two- and three-fold radiation effects as presented in

Figure 6c and

Figure 6d. Herein, the triple and quadruple air-slits are equally distributed within the same pitch width (

=0.25 μm). These additional slits introduce more degrees of asymmetry, thus leading to more change of the spectral position of the aGMRs. Meanwhile, these resonances shift toward shorter wavelengths (blue-shift) as the number of air-slits increases because the effective refractive index is reduced by more air gaps. This ability to dynamically tune singular states by simply adjusting the multiple air-slit promise for applications in metamaterials and metasurfaces.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, the asymmetric guided-mode resonance (aGMR) mechanism enables the radiation of tunable singular states by varying the structural asymmetry of photonic lattices (PLs) through air-slits. Our analysis demonstrates that the air-slit induced singular state can effectively control the spectra position of strong resonance interfering with background radiation. Through systematic investigation, we have shown that the refractive index plays a critical role in determining the spectral position and isolation of singular states. Dielectric materials such as silicon nitride (Si3N4) and silicon (Si) are proper for realizing tunable singular states due to their high refractive indices and compatible fabrication technologies. Furthermore, the multiple air-slits significantly enhance the tunability of singular states, which enables dynamic control over resonance positions through multiple folding behavior of resonances. By displacing the air-slits, dual functionalities (i.e., narrowband band pass filter and notch filtering) are achieved. It expects to be useful for versatile metasurface and metamaterial applications in optical filters, switches and photonic devices. Despite potential fabrication challenges such as precise air-slit alignment and symmetry control, these structures are feasible with advanced nanofabrication techniques. The proposed concepts are extendable to other spectral regions and polarization-independent designs by 2D metastructures. This work will be useful for developing highly tunable optical devices for photonic applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.K.; methodology, Y.K.; formal analysis, Y.K; investigation, Y.K.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.K.; R.M.; project administration, R.M.; funding acquisition, R.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported, in part, by the UT System Texas Nanoelectronics Research Superiority Award funded by the State of Texas Emerging Technology Fund and by the Texas Instruments Distinguished University Chair in Nanoelectronics endowment.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying the results presented in this paper are not publicly available at this time but may be obtained from the authors upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interest or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Ji, W.; Chang, J.; Xu, H.-X.; Gao, J.R.; Gröblacher, S.; Urbach, H.P.; Adam, A.J.L. Recent advances in metasurface design and quantum optics applications with machine learning, physics-informed neural networks, and topology optimization methods. Light Sci. Appl. 2023, 12, 169. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Armelles, G.; Bergamini, L.; Zabala, N.; García, F.; Dotor, M.L.; Torné, L.; Alvaro, R.; Griol, A.; Martínez, A.; Aizpurua, J.; et al. Metamaterial Platforms for Spintronic Modulation of Mid-Infrared Response under Very Weak Magnetic Field. ACS Photonics 2018, 5, 3956–3961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, V.-C.; Chu, C.H.; Sun, G.; Tsai, D.P. Advances in optical metasurfaces: fabrication and applications [Invited]. Opt. Express 2018, 26, 13148–13182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakšić, Z.; Vuković, S.; Matovic, J.; Tanasković, D. Negative Refractive Index Metasurfaces for Enhanced Biosensing. Materials 2011, 4, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerji, S.; Meem, M.; Majumder, A.; Vasquez, F.G.; Sensale-Rodriguez, B.; Menon, R. Imaging with flat optics: metalenses or diffractive lenses? Optica 2019, 6, 805–810. [Google Scholar]

- Roger, T.; Vezzoli, S.; Bolduc, E.; Valente, J.; Heitz, J.J.F.; Jeffers, J.; Soci, C.; Leach, J.; Couteau, C.; Zheludev, N.I.; et al. Coherent perfect absorption in deeply subwavelength films in the single-photon regime. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Overvig, A.C.; Shrestha, S.; Malek, S.C.; Lu, M.; Stein, A.; Zheng, C.; Yu, N. Dielectric metasurfaces for complete and independent control of the optical amplitude and phase. Light Sci. Appl. 2019, 8, 92. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Xiao, J.; Lisevych, D.; Shakouri, A.; Fan, Z. Deep-subwavelength control of acoustic waves in an ultra-compact metasurface lens. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X. Subwavelength Optical Engineering with Metasurface Waves. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2018, 6, 1701201. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Luo, X.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Q.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, N.; Duan, H. 3D-Integrated metasurfaces for full-colour holography. Light Sci. Appl. 2019, 8, 86. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, Y. Effective medium theory for anisotropic metamaterials. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 7892. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, Y.H.; Razmjooei, N.; Hemmati, H.; Magnusson, R. Perfectly-reflecting guided-mode-resonant photonic lattices possessing Mie modal memory. Opt. Express 2021, 29, 26971–26982. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Van de Groep, J.; Polman, A. Designing Dielectric Resonators on Substrates: Combining Magnetic and Electric Resonances. Opt. Express 2013, 21, 26285–26302. [Google Scholar]

- Genevet, P.; Capasso, F.; Aieta, F.; Khorasaninejad, M.; Devlin, R. Recent Advances in Planar Optics: From Plasmonic to Dielectric Metasurfaces. Optica 2017, 4, 139–152. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Grzegorczyk, T.M.; Wu, B.-I.; Pacheco, J.; Kong, J.A. Robust method to retrieve the constitutive effective parameters of metamaterials. Phys. Rev. E 2004, 70, 016608. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.S.; Magnusson, R. Theory and applications of guided-mode resonance filters. Appl. Opt. 1993, 32, 2606–2613. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Jin, R.; Zhou, C.; Jiang, Y.; Jia, Y.; Gao, Y.; Xu, L.; Hu, W.; Gao, J.; Song, Q. Ultrahigh-Q guided mode resonances in an All-dielectric metasurface. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3433. [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson, R.; Wang, S.S. New principle for optical filters. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1992, 61, 1022–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Murai, S.; Castellanos, G.W.; Raziman, T.V.; Curto, A.G.; Rivas, J.G. Enhanced Light Emission by Magnetic and Electric Resonances in Dielectric Metasurfaces. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2020, 8, 1902024. [Google Scholar]

- Marinica, D.C.; Borisov, A.G.; Shabanov, S.V. Bound States in the Continuum in Photonics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100, 183902. [Google Scholar]

- Azzam, S.I.; Kildishev, A.V. Photonic Bound States in the Continuum: From Basics to Applications. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2021, 9, 2001469. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Xing, X.; Zou, D.; Mao, B.; Yao, J.; Ouyang, C.; Wang, Z.; Wu, L. Terahertz narrowband filter metasurfaces based on bound states in the continuum. Opt. Express 2023, 31, 35272–35281. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Che, Y.; Zhang, T.; Shi, T.; Deng, Z.-L.; Cao, Y.; Guan, B.-O.; Li, X. Ultrasensitive Photothermal Switching with Resonant Silicon Metasurfaces at Visible Bands. Nano Lett. 2024, 24, 576–583. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Peng, Y.; Jin, Z.; Wu, X.; Gu, H.; Wei, D.; Zhu, Y.; Zhuang, S. Terahertz ultrasensitive biosensor based on wide-area and intense light-matter interaction supported by QBIC. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 462, 142347. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, Y.H.; Hemmati, H.; Magnusson, R. Quantifying bound and leaky states of resonant optical lattices by Rytov-equivalent homogeneous waveguides. Opt. Lett. 2023, 48, 311–314. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ko, Y.H.; Lee, K.J.; Simlan, F.A.; Magnusson, R. Singular states of resonant nanophotonic lattices. Nanophotonics 2023, 12, 263–272. [Google Scholar]

- Moharam, M.G.; Grann, E.B.; Pommet, D.A.; Gaylord, T.K. Formulation for Stable and Efficient Implementation of the Rigorous Coupled-Wave Analysis of Binary Gratings. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 1995, 12, 1068–1076. [Google Scholar]

- RSoft Products. DiffractMod; Synopsys, Inc.: Sunnyvale, CA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Rytov, S.M. Electromagnetic properties of a finely stratified medium. Sov. Phys. JETP 1956, 2, 466–475. [Google Scholar]

- Hemmati, H.; Magnusson, R. Applicability of Rytov's Full Effective-Medium Formalism to the Physical Description and Design of Resonant Metasurfaces. ACS Photonics 2020, 7, 3177–3187. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, M.J. An Introduction to Optical Waveguides; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, J.W.; Magnusson, R. Fano resonance formula for lossy two-port systems. Opt. Express 2013, 21, 17751–17759. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).