1. Introduction

Gait and balance disorders are highly prevalent in aging populations, with their incidence increasing significantly over time. Clinical guidelines in recent years have shown that approximately 10% of individuals between the ages of 60 and 70 experience gait impairments, and this proportion rises to 60%–85% in individuals over 80 years old [

1,

2]. Among individuals aged 60 and above, gait disorders caused by neurological conditions affect nearly 24% [

3]. In hospital settings, particularly in neurosurgical and neurological departments, the prevalence is even higher, reaching approximately 60% [

4]. These disorders, particularly those of neurogenic origin, are associated with reduced emotional well-being, impaired mobility, and a substantial decline in quality of life. Moreover, they significantly increase the risk of falls and fractures, leading to severe health complications [

5]. Given these risks, the ability to accurately assess gait abnormalities is critical for early diagnosis, treatment planning, and rehabilitation to prevent long-term disability [

6].

Certain neurological disorders manifest with distinct gait abnormalities that provide valuable diagnostic information. For instance, patients with idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus (iNPH) typically exhibit small-stepped, magnetic, or broad-based gait patterns [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Distinguishing iNPH from other conditions such as brain atrophy and senile dementia is crucial, as their treatments and prognosis differ significantly [

11]: For the former, effective surgical treatment can be performed [

12]. A comprehensive assessment not only identifies deviations and impairments in gait behavior but also provides objective data to guide clinical decision-making, monitor disease progression, and evaluate rehabilitation outcomes [

9].

Despite its clinical significance, gait assessment in neurology and neurosurgery remains largely subjective. Traditional evaluation methods, such as visual observation or video recordings, lack quantitative precision and suffer from inter-rater variability. Standardized functional tests, including the 10-Meter Walk Test (10MWT), Timed Up and Go (TUG), and Tinetti Performance-Oriented Mobility Assessment (POMA), are commonly used but provide limited objective gait parameters and are susceptible to variability among examiners [

13,

14]. Advanced motion capture systems, such as the Vicon Optical 3D Motion Capture System, Optotrak Certus System, and GAITRite System, offer detailed and quantitative gait assessments [

15]. However, their high cost, technical complexity, and the need for specialized environments have long restricted their widespread adoption in routine clinical practice [

13,

16].

To address these limitations, alternative low-cost gait analysis solutions have been explored. One promising approach is the use of Kinect-V2, a depth-sensing camera originally developed for gaming by Microsoft Corporation (Redmond, WA, USA). Kinect-V2 can capture depth data, track 25 skeletal joints in three dimensions, and perform non-invasive, cost-effective motion analysis. Several studies have demonstrated that Kinect-V2-derived spatiotemporal gait parameters (e.g., stride length, step length, cadence, and base width) correlate well with those obtained from gold-standard motion capture systems [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Given its affordability, portability, and ease of use, Kinect-V2 presents a viable option for quantitative gait analysis in clinical settings.

However, existing Kinect-V2-based gait analysis methods have several limitations that hinder their practical application. First, most studies rely on a single Kinect-V2 sensor, which restricts the field of view, results in depth information loss, and reduces measurement accuracy [

23]. Additionally, single-sensor setups require participants to walk in a straight line, limiting their utility for multi-directional or complex gait assessments. Second, the accuracy of temporal gait parameters, such as gait cycle phases, stance, and swing durations, remains insufficient for clinical use [

24,

25,

26,

27]. Third, there is currently no standardized protocol for depth sensor-based gait analysis, leading to variability in methodologies. Previous studies have often relied on customized software or Microsoft’s Kinect SDK and third-party open-source libraries (e.g., PyKinect2,

github.com/Kinect/PyKinect2) [

28], which limit algorithm scalability and hinder widespread clinical adoption.

To overcome these challenges, this study aimed to develop a low-cost digital gait analysis system integrating dual Kinect-V2 sensors and general-purpose software. By combining data from two depth sensors, the system enhances the field of view, reduces motion capture errors, and improves measurement accuracy. The system was validated across diverse clinical and domestic environments to assess its feasibility and accuracy in real-world applications. Ultimately, this study seeks to provide a practical, accessible, and cost-effective tool for neurological gait assessment, clinical diagnosis, and rehabilitation monitoring.

2. Materials and Methods

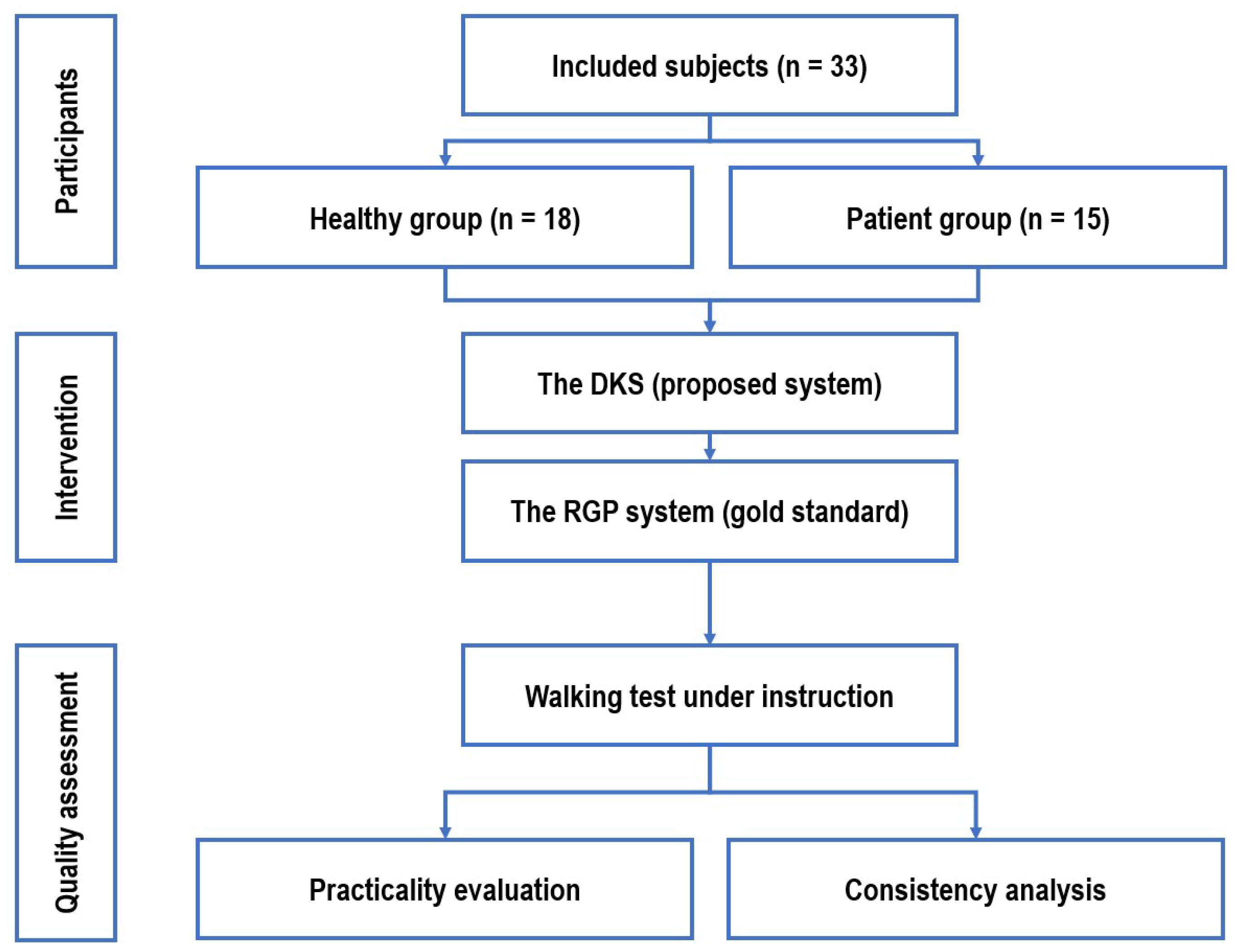

This section describes the inclusion and exclusion criteria of healthy participants and those with neurological gait disorders, followed by an overview of the apparatus, detailing the proposed "Dual Kinect-V2 System (DKS)" and the gold-standard, Right Gait & Posture (RGP) system, a commercial, high-sensitivity automated analysis system widely used in China. The experimental setup and protocol are then outlined, and the section concludes with the statistical interpretation used for system validation. The schematic of the study design is depicted in

Figure 1.

2.1. Participants

From December 2022 to December 2023, a total of 18 healthy volunteers and 15 patients with neurological gait disorders were recruited for this study. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Medical Center of the PLA General Hospital (Approval No. S2016-074-01). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion in the study.

2.1.1. Inclusion Criteria

Participants were recruited based on specific inclusion criteria: (1) Healthy participants were divided into two groups according to the Cutoff value commonly used in clinical guidelines in the field of gait analysis [

1,

2]: healthy adults (aged 18–60 years) and healthy elderly individuals (aged 60 years or older); (2) They had no prior medical conditions affecting gait and (3) were capable of following verbal instructions (e.g., “go straight,” “turn”). Patients with neurological gait disorders were diagnosed by a neurosurgeon or neurologist based on updated international guidelines: (1) They had no additional medical conditions likely to interfere with gait, (2) could walk independently, and (3) were able to comprehend and follow verbal instructions.

2.1.2. Exclusion Criteria

Participants were excluded if they: (1) had severe musculoskeletal or orthopedic conditions (e.g., osteoarthritis, limb deformities, recent lower limb surgery) that could significantly alter gait patterns. (2) Cognitive impairments (e.g., dementia, severe intellectual disability) that affected their ability to follow instructions also led to exclusion. (3) Individuals using assistive devices for ambulation (e.g., walkers, crutches, wheelchairs) were not included, as these interfere with natural gait assessment. (4) Those with severe neurological impairments (e.g., advanced Parkinson’s disease, stroke with severe hemiparesis, cerebellar ataxia) that prevented independent walking were excluded.

2.2. Apparatus

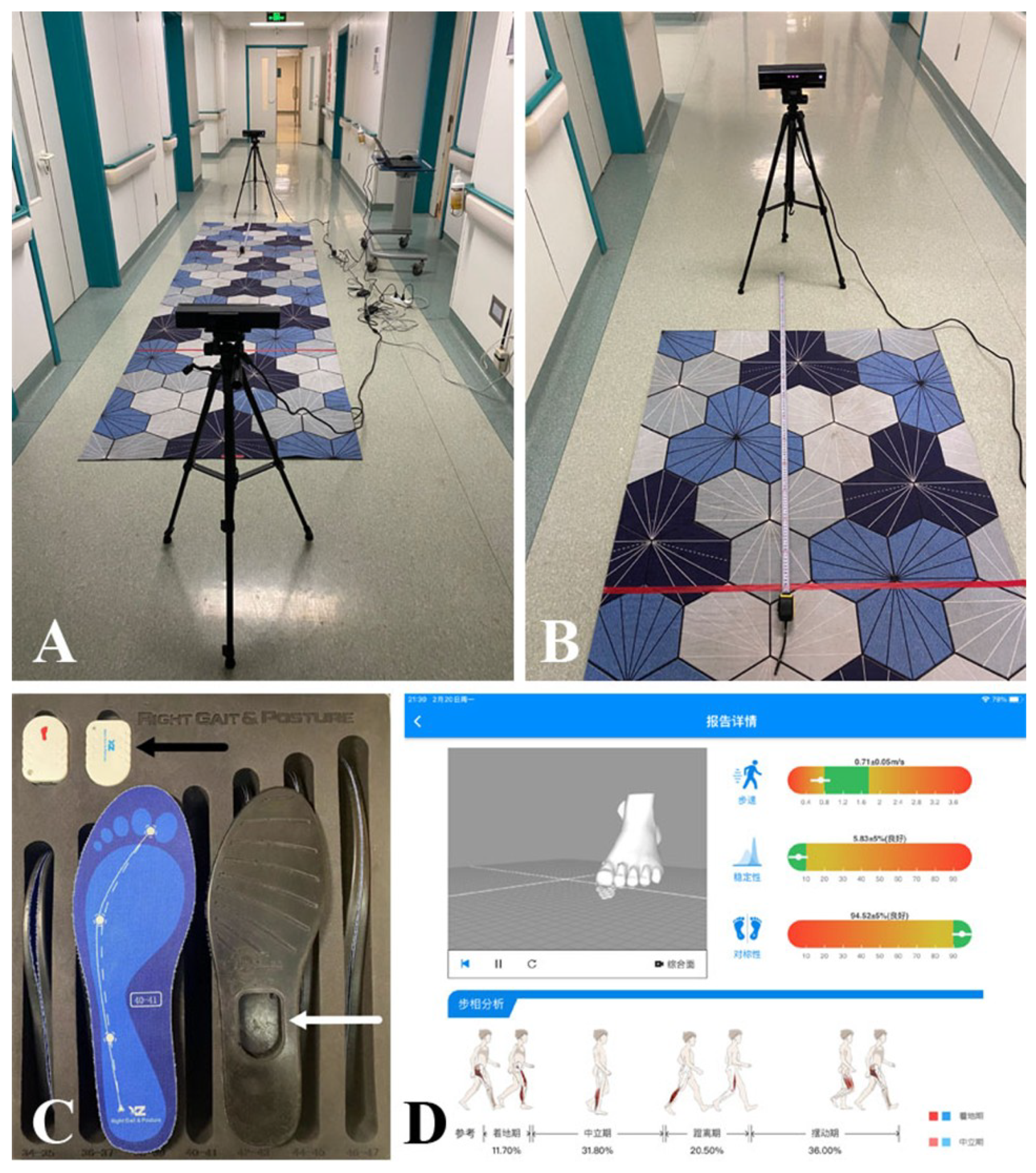

This study is aimed to develope and evaluate a newly developed, low-cost digital gait analysis system DKS based on dual Kinect-V2 sensors (see

Figure 2A,B), validating its accuracy against the RGP system, a well-established commercial gait analysis system (see

Figure 2C,D).

2.2.1. The Proposed Dual Kinect-V2 System (DKS)

The DKS is the newly developed, dual Kinect-V2-based gait analysis system proposed in this study (see

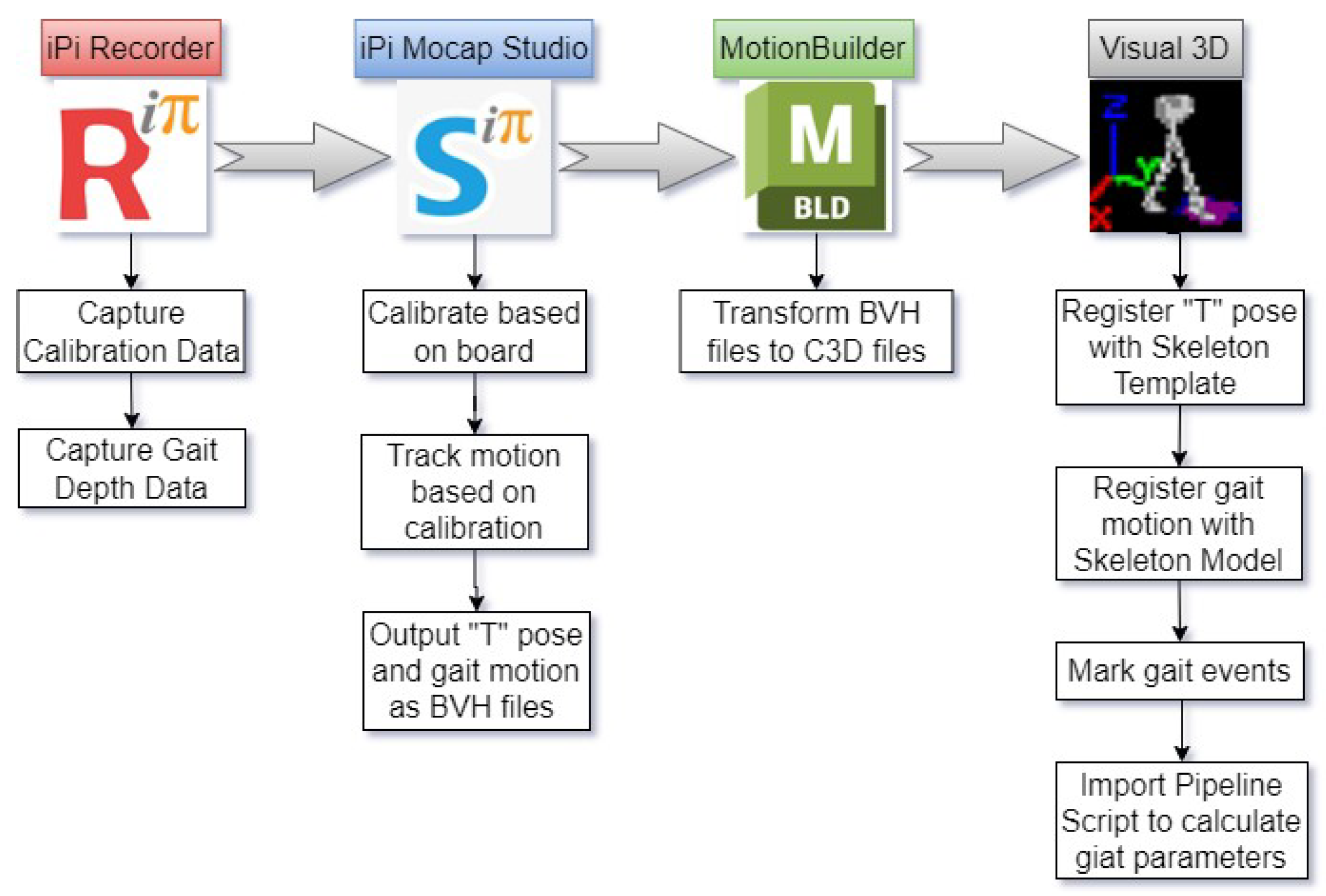

Figure 2A,B). It integrates two Kinect-V2 sensors with four general-purpose software platforms: iPi Recorder (V4.6.5.94, iPi Soft LLC, Moscow, Russia), iPi Mocap Studio (V4.5.0.249, iPi Soft LLC, Moscow, Russia), MotionBuilder 2023 (V23.0.0.21, Autodesk, Inc., San Rafael, California, USA), and Visual 3D (V3.21.0, C-Motion Inc., Germantown, Maryland, USA).

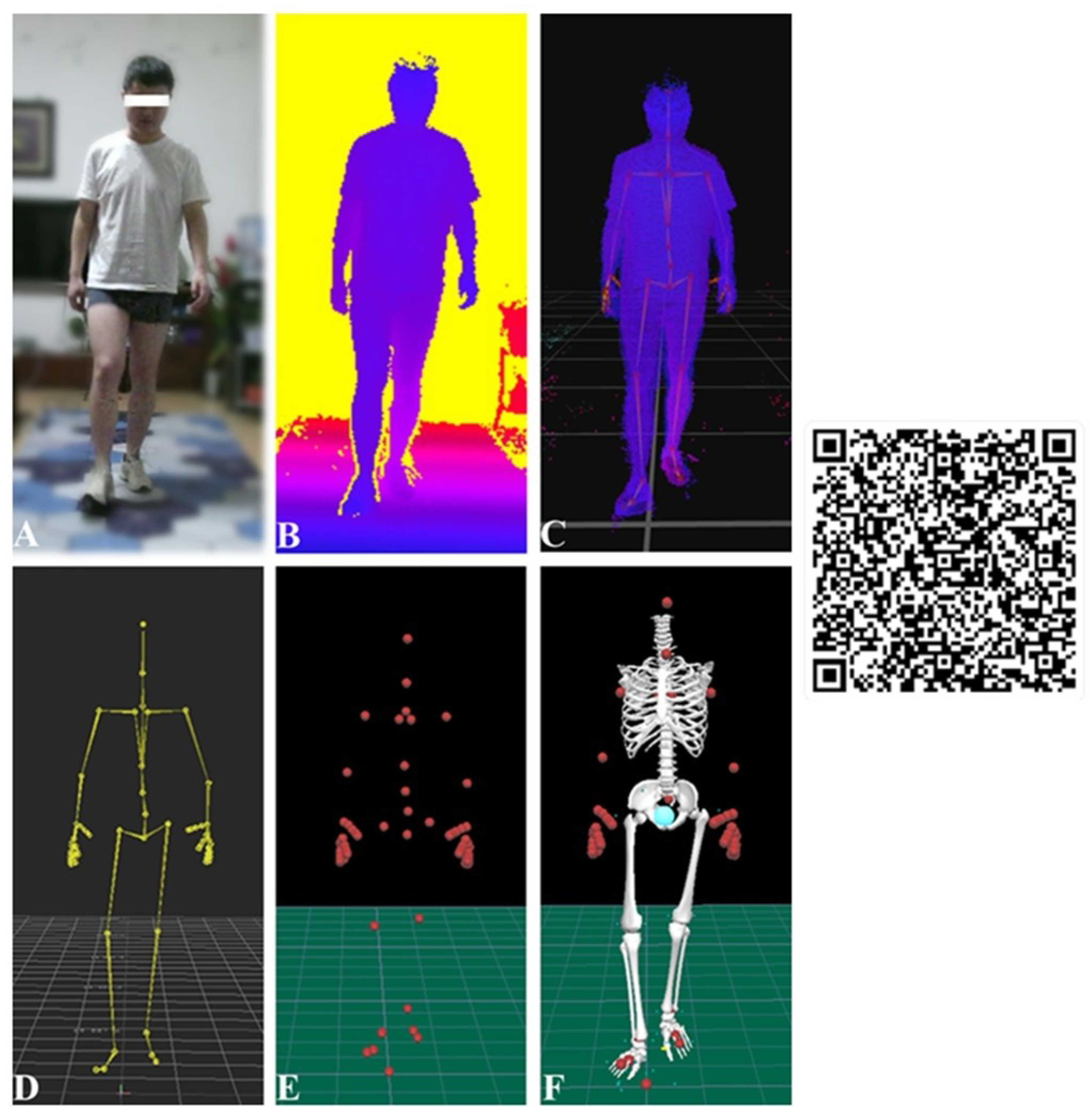

The Dual Kinect-V2 System (DKS) integrates dual Kinect-V2 sensors with multiple software tools to achieve real-time skeletal tracking and gait analysis. As shown in

Figure 3, iPi Recorder first captures depth-based gait motion and calibration data, which is then processed in iPi Mocap Studio, where bilateral depth information is fused into a 3D skeletal model tracking 23 joints at 30 Hz. The gait motion data is initially exported in BVH format, but since Visual 3D requires C3D format, the skeletal data is converted using MotionBuilder. In Visual 3D, the motion data is registered with a customized lower-limb skeletal template, key gait events are marked, and a computational pipeline extracts spatiotemporal gait parameters. This structured workflow ensures accurate gait assessment while maintaining a low-cost and portable alternative to traditional gait analysis systems. The transformation of gait data across different files and formats (i.e., RGB, depth, BVH, C3D, and so on) is illustrated in

Figure 4.

2.2.2. The Right Gait & Posture (RGP) System (Gold Standard)

The RGP system (Medical 3.0, Xingzheng Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China, RGP) is a commercial sensor-based system widely used in China that incorporates micro-posture sensors of various sizes within smart insoles to capture real-time gait data. During testing, participants walked in a straight path while wearing RGP-equipped smart insoles, which continuously transmitted gait data via Bluetooth to a cloud-based algorithm library for real-time processing. The system then generated an electronic gait analysis report, providing quantitative spatiotemporal gait parameters, as shown in

Figure 2C,D. Given its commercial validation and established measurement accuracy, the RGP was selected as the gold standard reference system against which the accuracy of DKS was assessed.

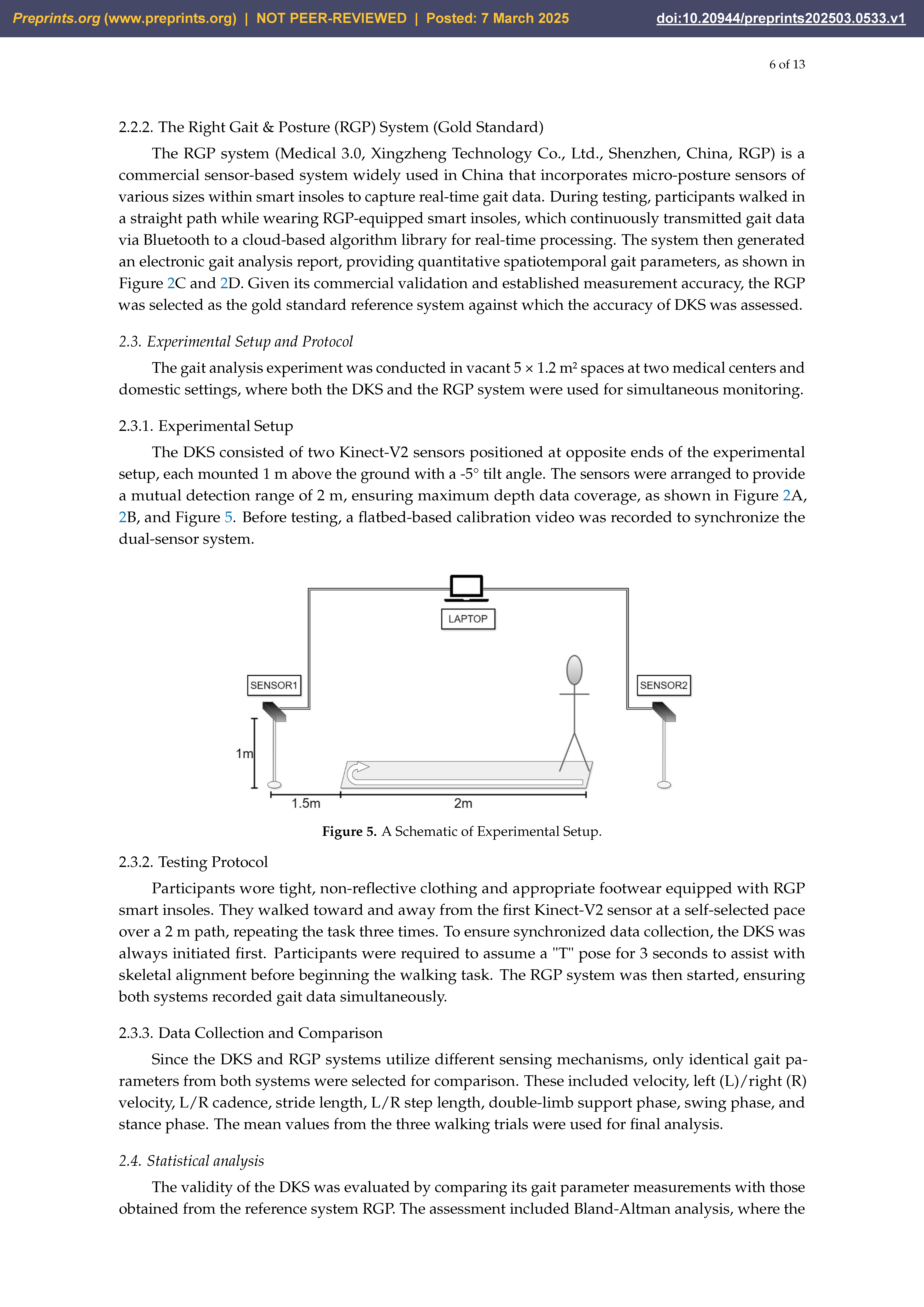

2.3. Experimental Setup and Protocol

The gait analysis experiment was conducted in vacant 5 × 1.2 m² spaces at two medical centers and domestic settings, where both the DKS and the RGP system were used for simultaneous monitoring.

2.3.1. Experimental Setup

The DKS consisted of two Kinect-V2 sensors positioned at opposite ends of the experimental setup, each mounted 1 m above the ground with a -5° tilt angle. The sensors were arranged to provide a mutual detection range of 2 m, ensuring maximum depth data coverage, as shown in

Figure 2A,B and

Figure 5. Before testing, a flatbed-based calibration video was recorded to synchronize the dual-sensor system.

2.3.2. Testing Protocol

Participants wore tight, non-reflective clothing and appropriate footwear equipped with RGP smart insoles. They walked toward and away from the first Kinect-V2 sensor at a self-selected pace over a 2 m path, repeating the task three times. To ensure synchronized data collection, the DKS was always initiated first. Participants were required to assume a "T" pose for 3 seconds to assist with skeletal alignment before beginning the walking task. The RGP system was then started, ensuring both systems recorded gait data simultaneously.

2.3.3. Data Collection and Comparison

Since the DKS and RGP systems utilize different sensing mechanisms, only identical gait parameters from both systems were selected for comparison. These included velocity, left (L)/right (R) velocity, L/R cadence, stride length, L/R step length, double-limb support phase, swing phase, and stance phase. The mean values from the three walking trials were used for final analysis.

2.4. Statistical analysis

The validity of the DKS was evaluated by comparing its gait parameter measurements with those obtained from the reference system RGP. The assessment included Bland-Altman analysis, where the mean difference (Mean Diff) and 95% limits of agreement (LOA) were calculated. Additionally, the Pearson’s correlation coefficient (PCC, r) was used to determine the relative consistency and linear relationship between the two systems [

29], while the concordance correlation coefficient (CCC,

) measured absolute agreement [

30]. Correlation strength was classified according to the criteria outlined by Koo et al. [

31], where values were interpreted as poor (< 0.5), moderate (≥ 0.5 and < 0.75), good (≥ 0.75 and < 0.9), and excellent (≥ 0.9). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 [

32]. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (Version 26.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, New York, USA).

3. Results

This section first describes the demographic data results, as well as the technical aspects of gait data processing. Due to the increased complexity of detecting gait events in patients with gait disorders, the agreement between the RGP and the DKS was assessed separately for the healthy group (adults and elderly participants) and the patient group.

3.1. Participant Demography

A total of nine healthy adults, nine healthy elderly individuals, and fifteen patients with neurological gait disorders successfully completed the experimental tasks without incident. The demographic and clinical characteristics of all participants are summarized in

Table 1.

3.2. Practicality Evaluation

Each full gait motion capture session required approximately 15 minutes, followed by 45 minutes for data processing and analysis. The DKS successfully processed and analyzed the gait data of all participants without any malfunctions.

3.3. Validation in the Healthy Group

The agreement between DKS and RGP in the healthy group is presented in

Table 2. The Mean Diff values indicate slight discrepancies in L cadence (Mean Diff = -1.163) and

r cadence (Mean Diff = -2.602). The PCC analysis demonstrates excellent relative agreement for velocity,

r velocity, L cadence,

r cadence, L step length, and

r step length (0.908 ≤

r≤ 0.967, p < 0.01). Additionally, L velocity, stride length, double-limb support phase, swing phase, and stance phase exhibited good relative agreement (0.750 ≤

r≤ 0.880, p < 0.01). Regarding CCC results, most gait parameters showed moderate to good absolute agreement (0.712 ≤

≤ 0.882, p < 0.01), except for double-limb support phase (

= 0.572, p < 0.01), swing phase (

= 0.603, p < 0.01), and stance phase (

= 0.569, p < 0.01), which demonstrated lower absolute agreement.

3.4. Validation in the Patient Group

The validation results for the patient group are summarized in

Table 3. Compared to the gold standard (RGP), the double-limb support phase (Mean Diff = 5.324), swing phase (Mean Diff = -2.539), and stance phase (Mean Diff = 2.333) exhibited more pronounced differences. Despite these discrepancies, PCC analysis revealed a strong correlation between the gait parameters obtained from both systems. With the exception of double-limb support phase, swing phase, and stance phase, which showed moderate relative agreement (0.708 ≤

r≤ 0.717, p < 0.01), all other gait parameters exhibited good to excellent relative agreement (0.854 ≤

r≤ 0.985, p < 0.01). The CCC results further indicated good to excellent absolute agreement for most parameters (0.767 ≤

≤ 0.933, p < 0.01), except for double-limb support phase, swing phase, and stance phase, which showed lower absolute agreement (0.383 ≤

≤ 0.533, p < 0.05).

4. Discussion

Accurate gait assessment is essential for the diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation of neurological disorders [

14]. However, clinical gait evaluation remains largely subjective, relying on visual observation and standardized functional tests that lack quantitative precision [

33]. The emergence of depth sensor-based gait analysis systems, such as those utilizing Kinect V1/V2, presents a promising solution by providing objective, repeatable, and quantitative gait data [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

24,

25,

26,

27].

This study presents the first low-cost digital gait analysis system based on dual Kinect-V2 sensors and open-source software, designed to offer an affordable and accessible alternative to existing clinical gait analysis systems. Through a controlled validation study, the system’s technical feasibility and accuracy were evaluated against the commercially validated RGP system, which served as the gold standard. Additionally, a self-developed post-processing module enabled end-to-end motion capture, skeletal modeling, and digital gait analysis for both patients in medical centers and healthy adults in domestic settings.

The results of this study demonstrated that the spatiotemporal gait parameters obtained from the DKS showed strong consistency with those from the RGP system, with the exception of temporal gait parameters (i.e., double-support, swing, and stance phases), which exhibited greater variability. Notably, the accuracy achieved in this study was comparable to, if not superior to, that of previous studies [

22,

25,

27]. Moreover, the gait analysis process was systematically optimized to improve efficiency and clinical usability, ensuring that the system could be reliably integrated into various healthcare settings.

The statistical validation revealed good to excellent agreement for most spatiotemporal parameters, confirming the reliability of the DKS. However, slight discrepancies were observed in step length, stride length, and velocity, which were likely due to minor tracking drift along the Y-axis (forward-backward movement). Although enlarging the detected foot size in motion tracking could mitigate this drift, the data fusion from dual sensors may have resulted in occasional bilateral switching of tracking targets, affecting measurement consistency. The most significant deviations were found in temporal gait parameters, particularly in patients with gait disorders. These discrepancies were primarily due to difficulties in accurately detecting heel strike and toe-off events, which are essential for computing swing, stance, and double-support phases. The presence of abnormal gait patterns in patients further complicated event detection. Despite these challenges, the relative agreement for these parameters remained moderate to good, indicating that they maintained a linear relationship with the gold-standard system and could still provide clinically relevant gait information. Several factors likely contributed to the observed deviations, including differences in frame rate, as the DKS operated at 25–30 Hz, whereas the RGP system recorded at 50 Hz, potentially affecting temporal accuracy. Additionally, the DKS estimates joint positions using depth data, which may not align precisely with true anatomical landmarks, especially in the lower limbs. Differences in computational algorithms also played a role, as the DKS relies on simulated joint modeling, while the RGP system captures gait parameters using posture sensors embedded in smart insoles.

The DKS developed in this study has several advantages over existing commercial solutions. First, its cost-effectiveness is a significant benefit, as the hardware costs approximately $1,000, and with the addition of self-developed software, the total cost remains under $2,000, making it affordable for clinical and research use. The system is also non-invasive, requiring no direct contact with the patient, which reduces discomfort and simplifies setup procedures compared to wearable sensor-based systems. Furthermore, the DKS is highly portable and flexible, allowing deployment in outpatient clinics, community healthcare centers, and even home environments, thus making gait analysis more accessible and convenient. Given these strengths, the system has potential applications not only in clinical diagnosis but also in home-based gait assessment, supporting remote monitoring and rehabilitation programs for patients with mobility impairments.

Despite its promising results, the DKS has certain limitations that warrant improvement. One key issue is the accuracy of temporal gait parameters, particularly in detecting heel strike and toe-off events, which affects stance, swing, and double-limb support phase calculations [

34]. Depth-based skeletal tracking may not precisely align with true anatomical landmarks, leading to deviations. Additionally, the system lacks validation for kinematic parameters such as hip, knee, and ankle joint angles [

35,

36], as these were not included in the RGP system. The need for manual gait event selection also limits automation, preventing real-time analysis. Future improvements in skeletal tracking algorithms and gait event detection, along with upgrading to advanced depth sensors like Azure Kinect, could enhance accuracy, spatial resolution, and tracking reliability [

37].

Beyond system constraints, this study has some methodological limitations. The small sample size, especially in the neurological patient group, may affect statistical robustness and generalizability. Expanding the cohort to include a wider range of neurological gait disorders would strengthen clinical applicability. Additionally, while spatiotemporal parameters were validated, the lack of a gold-standard kinematic reference system limited assessment of joint motion accuracy. Future studies should incorporate high-precision motion capture systems like VICON (

vicon.com) to validate full-body kinematics [

38]. Moreover, while the study demonstrated the system’s feasibility in clinical and home environments, its long-term real-world performance remains to be evaluated. Further research should assess its stability and reliability over extended periods in routine gait monitoring and rehabilitation settings.

5. Conclusions

In this study, a low-cost digital gait analysis system based on dual Kinect-V2 sensors was successfully developed and validated. Its clinical feasibility and accuracy were assessed by comparing it with a commercial gold-standard system, demonstrating its potential as an affordable and accessible solution for digital gait analysis in neurological disorders. Equipped with minimally invasive sensors and user-friendly software, the system allows medical professionals to perform rapid, quantitative, and relatively accurate gait assessments in outpatient clinics, hospital wards, and home settings for older adults at high risk of falls. This capability is particularly valuable for differential diagnosis, therapeutic monitoring, and rehabilitation follow-up in neurological conditions, as well as for fall prevention and risk assessment in aging populations. While the system shows significant promise, further optimization and advancements are needed to enhance gait parameter accuracy, streamline workflow, and enable fully automated gait capture and analysis, ultimately improving its clinical applicability and usability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Z., Z.Q., J.Z. and X.C.; methodology, S.Z., Z.G., X.C., X.X. and J.Z.; software, S.Z., Z.Q., M.A.S., J.Z., Z.G. and X.C.; validation, S.Z., Z.G. and M.A.S.; formal analysis, S.Z., Z.G., M.A.S., J.Z. and X.X.; investigation, S.Z.; resources, M.A.S., X.X., J.Z. and X.C.; data curation, S.Z., Z.G. and Z.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Z. and Z.Q.; writing—review and editing, Z.Q. and X.C.; visualization, S.Z. and Z.Q.; supervision, X.C. and J.Z.; project administration, X.C. and J.Z.; funding acquisition, X.C. and J.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funding was provided by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 82272134 (to X.C.)

Institutional Review Board Statement

The IRB and local ethics committee of the Chinese PLA General Hospital approved this study.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

Not Applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 10MWT |

10-Meter Walk Test |

| 2D |

Two-Dimensional |

| 3D |

Three-Dimensional |

| 95% LOA |

Limits of Agreements |

| BVH |

Biovision Hierarchy |

| CCC |

Concordance Correlation Coefficients |

| DKS |

Dual Kinect-V2 System |

| iNPH |

Idiopathic Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus |

| PCC |

earson’s correlation coefficien |

| POMA |

Performance-Oriented Mobility Assessment |

| RGB |

Red Green Blue |

| RGP |

Right Gait & Posture |

| SDK |

Software Development Kit |

| TUG |

Timed Up and Go |

References

- Pirker, W.; Katzenschlager, R. Gait disorders in adults and the elderly: A clinical guide. Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift 2017, 129, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Osoba, M.Y.; Rao, A.K.; Agrawal, S.K.; Lalwani, A.K. Balance and gait in the elderly: A contemporary review. Laryngoscope investigative otolaryngology 2019, 4, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mahlknecht, P.; Kiechl, S.; Bloem, B.R.; Willeit, J.; Scherfler, C.; Gasperi, A.; Rungger, G.; Poewe, W.; Seppi, K. Prevalence and burden of gait disorders in elderly men and women aged 60–97 years: a population-based study. PloS one 2013, 8, e69627. [Google Scholar]

- Stolze, H.; Klebe, S.; Baecker, C.; Zechlin, C.; Friege, L.; Pohle, S.; Deuschl, G. Prevalence of gait disorders in hospitalized neurological patients. Movement disorders: official journal of the Movement Disorder Society 2005, 20, 89–94. [Google Scholar]

- Jahn, K.; Zwergal, A.; Schniepp, R. Gait disturbances in old age: classification, diagnosis, and treatment from a neurological perspective. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International 2010, 107, 306. [Google Scholar]

- Kiprijanovska, I.; Gjoreski, H.; Gams, M. Detection of gait abnormalities for fall risk assessment using wrist-worn inertial sensors and deep learning. Sensors 2020, 20, 5373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Qi, Z.; Shao, Y.; Yao, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, Y.; E, Q.; Liu, C.; Hu, H.; et al. Quantitative evaluation of gait changes using APDM inertial sensors after the external lumbar drain in patients with idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Frontiers in Neurology 2021, 12, 635044. [Google Scholar]

- Relkin, N.; Marmarou, A.; Klinge, P.; Bergsneider, M.; Black, P.M. Diagnosing idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus. Neurosurgery 2005, 57, S2–4. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, R.; Marquez, J.; Osmotherly, P. Clinimetric properties and minimal clinically important differences for a battery of gait, balance, and cognitive examinations for the tap test in idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Neurosurgery 2019, 84, E378–E384. [Google Scholar]

- Mori, E.; Ishikawa, M.; Kato, T.; Kazui, H.; Miyake, H.; Miyajima, M.; Nakajima, M.; Hashimoto, M.; Kuriyama, N.; Tokuda, T.; et al. Guidelines for management of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Neurologia medico-chirurgica 2012, 52, 775–809. [Google Scholar]

- Petersen, G.; Ortega-Matute, E.; Perez-Nieto, D.; Inzunza, A.; Navarro, V.G. Diagnostic importance of disproportionately enlarged subarachnoid space hydrocephalus and Callosal Angle measurements in the context of normal pressure hydrocephalus: A useful tool for clinicians. Journal of the Neurological Sciences 2024, 466, 123250. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Williams, M.A.; Malm, J. Diagnosis and treatment of idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Continuum: Lifelong Learning in Neurology 2016, 22, 579–599. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Simon, S.R. Quantification of human motion: gait analysis—benefits and limitations to its application to clinical problems. Journal of biomechanics 2004, 37, 1869–1880. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- do Carmo Vilas-Boas, M.; Cunha, J.P.S. Movement quantification in neurological diseases: Methods and applications. IEEE reviews in biomedical engineering 2016, 9, 15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Bilney, B.; Morris, M.; Webster, K. Concurrent related validity of the GAITRite® walkway system for quantification of the spatial and temporal parameters of gait. Gait & posture 2003, 17, 68–74. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, Y.; Cheung, L.; Patterson, K.K.; Iaboni, A.; et al. Factors influencing the clinical adoption of quantitative gait analysis technologies for adult patient populations with a focus on clinical efficacy and clinician perspectives: protocol for a scoping review. JMIR research protocols 2023, 12, e39767. [Google Scholar]

- Dubois, A.; Bresciani, J.P. Validation of an ambient system for the measurement of gait parameters. Journal of biomechanics 2018, 69, 175–180. [Google Scholar]

- Steinert, A.; Sattler, I.; Otte, K.; Röhling, H.; Mansow-Model, S.; Müller-Werdan, U. Using new camera-based technologies for gait analysis in older adults in comparison to the established GAITRite system. Sensors 2019, 20, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilas-Boas, M.d.C.; Rocha, A.P.; Choupina, H.M.P.; Cardoso, M.N.; Fernandes, J.M.; Coelho, T.; Cunha, J.P.S. Validation of a single RGB-D camera for gait assessment of polyneuropathy patients. Sensors 2019, 19, 4929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Mithraratne, K.; Wilson, N.C.; Wang, X.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, Y. The validity and reliability of a kinect v2-based gait analysis system for children with cerebral palsy. Sensors 2019, 19, 1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summa, S.; Tartarisco, G.; Favetta, M.; Buzachis, A.; Romano, A.; Bernava, G.M.; Sancesario, A.; Vasco, G.; Pioggia, G.; Petrarca, M.; et al. Validation of low-cost system for gait assessment in children with ataxia. Computer methods and programs in biomedicine 2020, 196, 105705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Springer, S.; Yogev Seligmann, G. Validity of the kinect for gait assessment: A focused review. Sensors 2016, 16, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usami, T.; Nishida, K.; Iguchi, H.; Okumura, T.; Sakai, H.; Ida, R.; Horiba, M.; Kashima, S.; Sahashi, K.; Asai, H.; et al. Evaluation of lower extremity gait analysis using Kinect V2® tracking system. SICOT-J 2022, 8, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, J.; Kuenze, C.; Jacopetti, M.; Signorile, J.F.; Eltoukhy, M. Validity of the Microsoft Kinect™ in assessing spatiotemporal and lower extremity kinematics during stair ascent and descent in healthy young individuals. Medical engineering & physics 2018, 60, 70–76. [Google Scholar]

- Guffanti, D.; Brunete, A.; Hernando, M.; Rueda, J.; Navarro Cabello, E. The accuracy of the Microsoft Kinect V2 sensor for human gait analysis. A different approach for comparison with the ground truth. Sensors 2020, 20, 4405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, R.; Kubota, T.; Yamasaki, T.; Higashi, A. Validity of the total body centre of gravity during gait using a markerless motion capture system. Journal of Medical Engineering & Technology 2018, 42, 175–181. [Google Scholar]

- Albert, J.A.; Owolabi, V.; Gebel, A.; Brahms, C.M.; Granacher, U.; Arnrich, B. Evaluation of the pose tracking performance of the azure kinect and kinect v2 for gait analysis in comparison with a gold standard: A pilot study. Sensors 2020, 20, 5104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.a.; Ruppert, T.; Eigner, G.; Abonyi, J. Assessing human worker performance by pattern mining of Kinect sensor skeleton data. Journal of Manufacturing Systems 2023, 70, 538–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amdisen, A. Pearson’s correlation coefficient, p-value, and lithium therapy. Biological psychiatry 1987, 22, 926–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, T.S.; Chinchilli, V.M.; Carrasco, J.L. A repeated measures concordance correlation coefficient. Statistics in medicine 2007, 26, 3095–3113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, T.K.; Li, M.Y. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. Journal of chiropractic medicine 2016, 15, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mehta, D.; Sridhar, S.; Sotnychenko, O.; Rhodin, H.; Shafiei, M.; Seidel, H.P.; Xu, W.; Casas, D.; Theobalt, C. Vnect: Real-time 3d human pose estimation with a single rgb camera. Acm transactions on graphics (tog) 2017, 36, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallmann, H.W. Introduction to observational gait analysis. Home health care management & practice 2009, 22, 66–68. [Google Scholar]

- Rudisch, J.; Jöllenbeck, T.; Vogt, L.; Cordes, T.; Klotzbier, T.J.; Vogel, O.; Wollesen, B. Agreement and consistency of five different clinical gait analysis systems in the assessment of spatiotemporal gait parameters. Gait & posture 2021, 85, 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Błażkiewicz, M. Muscle force distribution during forward and backward locomotion. Acta of Bioengineering and Biomechanics 2013, 15, 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Naderi, S.; Mohammadipour, F.; Amir Seyfaddini, M.R. Kinematics of lower extremity during forward and backward walking on different gradients. Physical Treatments-Specific Physical Therapy Journal 2017, 7, 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Yeung, L.F.; Yang, Z.; Cheng, K.C.C.; Du, D.; Tong, R.K.Y. Effects of camera viewing angles on tracking kinematic gait patterns using Azure Kinect, Kinect v2 and Orbbec Astra Pro v2. Gait & posture 2021, 87, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Jebeli, M.; Bilesan, A.; Arshi, A. A study on validating KinectV2 in comparison of Vicon system as a motion capture system for using in Health Engineering in industry. Nonlinear Engineering 2017, 6, 95–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).