1. Introduction

Aerodynamic flow control (AFC) is a multi-disciplinary area of research and development that holds the potential to revolutionize the design and performance of various aerodynamic systems. AFC focuses on manipulating and controlling the flow of air over an object’s surface to improve its aerodynamic performance like to reduce drag, enhance lift, and improve the overall efficiency and stability of the object, which is often an aircraft, but can also include cars, wind turbines, and other aerodynamic structures like buildings and bridges.

There are various techniques used in aerodynamic flow control, including passive, active and hybrid. Passive flow control involves typically designing the object’s surface in a way that naturally influences airflow like vortex generators, winglets, and riblets, which are small surface features that help manage airflow and reduce drag. Active flow control uses external devices or systems to manipulate airflow dynamically like blowing or suction, where air is either injected into or removed from the boundary layer to delay separation and reduce drag. Other techniques are synthetic jets, plasma actuators, and electromagnetic fields. Hybrid flow control method combines both passive and active techniques and try to maximize the benefits of both approaches. This method often involves the use of passive devices in conjunction with active systems to achieve optimal aerodynamic performance.

The development and implementation of AFC technologies have significant implications for various industries. In aviation, these technologies can lead to more fuel-efficient and environmentally friendly aircraft by reducing drag and enhancing lift. In the automotive industry, aerodynamic flow control can improve vehicle performance and fuel efficiency. Additionally, in renewable energy, optimizing airflow over wind turbine blades can increase energy production. Another critical area in hydro and aerodynamics is the control of bluff-body wakes and the suppression of related vortex shedding, which allows significantly reduce unsteady loads and induced vibrations.

Recent literature surveys have highlighted that AFC systems and methods have become a significant trend across various industrial sectors. Several noteworthy papers have been identified in this context: Greenblatt and Williams [

20] and Lee et al. [

28] presented state-of-the-art methods for the aviation industry; Bharghava et al. [

6] provided a comprehensive survey of synthetic jet applications for active flow control systems; Mariaprakasam et al. [

46] discussed methods for reducing aerodynamic drag in vehicles; Rashidi et al. [

56] offered a detailed review of technologies for vortex-shedding suppression and wake-dynamics control; Chen et al. [

13] presented results dedicated to flow control for circular cylinders; Derakhshandeh and Alam [

16] and Lekkala et al. [

29] reviewed the wakes of bluff bodies; Tayebi and Torabi [

76] analyzed flow control techniques for vertical wind turbines.

In the aerospace industry, one example of an innovative project is the CRANE (control of revolutionary aircraft with novel effectors) program. The goal of this strategic initiative is to design, build, and flight test a new X-plane that incorporates AFC as a core design feature. The experimental aircraft, now designated the X-65, is being developed for the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency CRANE program. The X-65 is designed to demonstrate and test the use of AFC to control flight at tactical speeds and improve performance throughout the flight envelope, and has potential for both commercial and military applications. AFC technology replaces traditional flaps and rudders with actuators and effectors to control airflow, resulting in improved aerodynamics, reduced weight, and mechanical simplicity. The aerodynamic community believes that AFC-based flight control systems will be smaller and lighter than conventional systems, providing increased safety and stability in flight. For military purposes, AFC technology provides additional benefits such as reducing aircraft signature and increasing their survivability and maneuverability.

Aerodynamic flow control using Trapped Vortex Cells (TVC) distributed on various surfaces of an obstacle is a promising alternative technology applicable to a wide range of engineering disciplines. A brief historical overview can be found in the pioneering works by Sedda et al. [

66] and Lysenko et al. [

42]. The concept of trapping vortices was initially proposed by Ringleb [

58], followed by Kasper [

26], who patented a glider featuring a trapped vortex structure to achieve high lift. In the early 1990s, Savitsky et al. [

63] further developed this idea and tested the ’EKIP,’ a blended wing-body aircraft equipped with several TVCs.

In previous work by Lysenko et al. [

42], a novel bluff-body (BB hereafter) design incorporating AFC based on the trapped vortex cells was presented, accompanied by pioneering large-eddy simulations (LES). The bluff body consisted of a half-cylinder main block with a diameter and span length of

D, along with two attached semi-spherical blocks. The AFC system, albeit with some level of abstraction, successfully demonstrated nearly undetached flow past the obstacle. It is important to note that this configuration was a preliminary design, where the fluid suction system from the vehicle engine was replicated by boundary conditions with fixed, negative mass flow rates. The aerodynamic performance, measured as the lift-to-drag ratio (

K), of BB with AFC was significantly improved to

, compared to the original bluff body without AFC, which exhibited a negative lift force and

. The energy losses of the AFC system were estimated to be approximately

of the total drag force.

The present work extends these previous efforts. The bluff body, now designed as a thick airfoil with a thickness of

(equivalent to a semi-circular cylinder) and two integrated trapped vortex cells, is also investigated using LES. For development purposes, the design was simplified by removing the previously attached semi-spherical blocks to avoid complex interactions of unwanted eddies and vortex structures with the main flow. Numerical simulations are performed for a diameter-based Reynolds number of

, a Mach number of

, and a zero angle of attack. Previously, the numerical platform was validated for turbulent flows over the semi-circular (HC hereafter) and circular (CC hereafter) cylinders at the diameter-based Reynolds numbers of

[

41] and

[

44], respectively, realizing satisfactory matches with available experimental and numerical data. Results achieved in previous studies [

41,

42,

44] serve as the basis for further AFC concept development.

More specifically, the aims and objectives of this work are as follows:

To perform numerical simulations based on LES on a simplified bluff body with AFC at and zero angle of attack. To investigate its aerodynamic characteristics, energy losses and to verify that the flow is practically unseparated, except for small-scale turbulence.

Based on the classical RANS approach, to numerically investigate the effect of viscosity on the design efficiency and to show that this concept is practically invariant with respect to the Reynolds number, i.e., the lift-to-drag ratio is approximately constant over a wide range of Reynolds numbers () and converges to an asymptotic value. The limiting case when the Reynolds number tends to infinity, , is estimated based on both analytical considerations and a numerical experiment when the Euler equations are solved. As a general result, it was accomplished the lift force of the developed concept is approximately of its limiting analytical value ().

The article is presented in five parts. The first two sections are devoted to the problem statement and aspects of numerical and mathematical modeling. Then the main results are presented and compared with the already available experimental and numerical data. The fourth part provides a brief discussion and critical review. At the end, the main conclusions are presented.

2. Problem Statement And Computational Grids

A brief problem statement, key design features, description of the computational domain and finite-volume grids are presented. The turbulent flow is characterized by the following Reynolds and Mach numbers: , , respectively. Here is the density, U is the velocity, a is the speed of sound, represents the dynamic molecular viscosity, D is the diameter of the thick airfoil (semi-circular cylinder). The subscript ∞ indicates the flow parameters at the inlet boundary.

2.1. Overview of the Active Flow Control Concept Based on the Trapped Vortex Cells

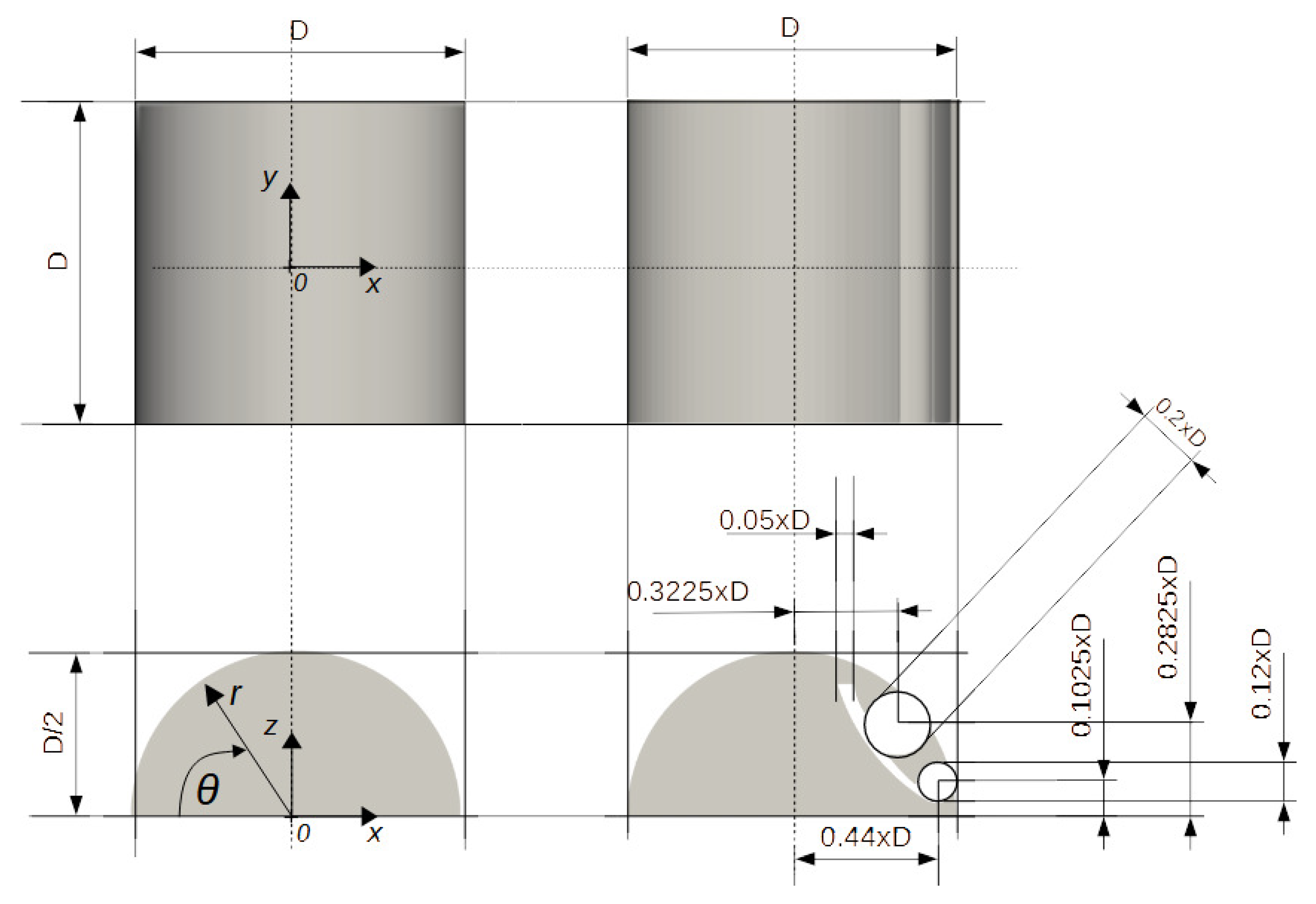

The primary design dimensions of the thick airfoil, both with and without an active flow control system, are depicted in

Figure 1. BB is composed of a main block shaped as a half-cylinder with a diameter

D and a span length of

D. The diameter of the half-cylinder,

D, serves as the linear reference scale. The overall width, height, and span lengths of the bluff body are

,

, and

, respectively. BB with active flow control incorporates a system of the two trapped vortex cells, with diameters of

and

respectively, positioned on its the suction (upper) side. Each TVC has a span length equal to

D. Two vortex cells are connected by an arch-shaped channel. The outlet section of the channel has a surface area of

, which is used for air suction (

Figure 2,a).

The present concept has been redesigned compared to initial study [

42], resulting in nearly undetached flow past the airfoil. It is important to highlight that this system was developed after several dozen optimization iterations. This concept also abstracts the active flow control system for air suction. In the current model, the consumed air is withdrawn inside BB, which is not a realistic scenario for real-life applications. However, the authors believe that this design is satisfactory as a proof-of-concept and holds potential for further development.

The physics and topology of the flow over BB without trapped vortex cells are qualitatively similar to the flow over a semi-circular cylinder at

, as discussed in detail previously [

41]. At a Reynolds number of

, the separation of the laminar boundary layers occurs in the sub-critical flow regime. This condition results in complex, nonlinear interactions between near and far wakes characterized by two types of flow instabilities (

Figure 2, b). The Kelvin-Helmholtz instability of the separated shear layer, along with vortex shedding (Bénard/von Kármán instability), dominates the wake.

Figure 2, c shows the schematic flow over the BB with integrated vortex cells. Unlike the initial study [

42], this design completely rearranges the flow over the airfoil, making it predominantly unseparated.

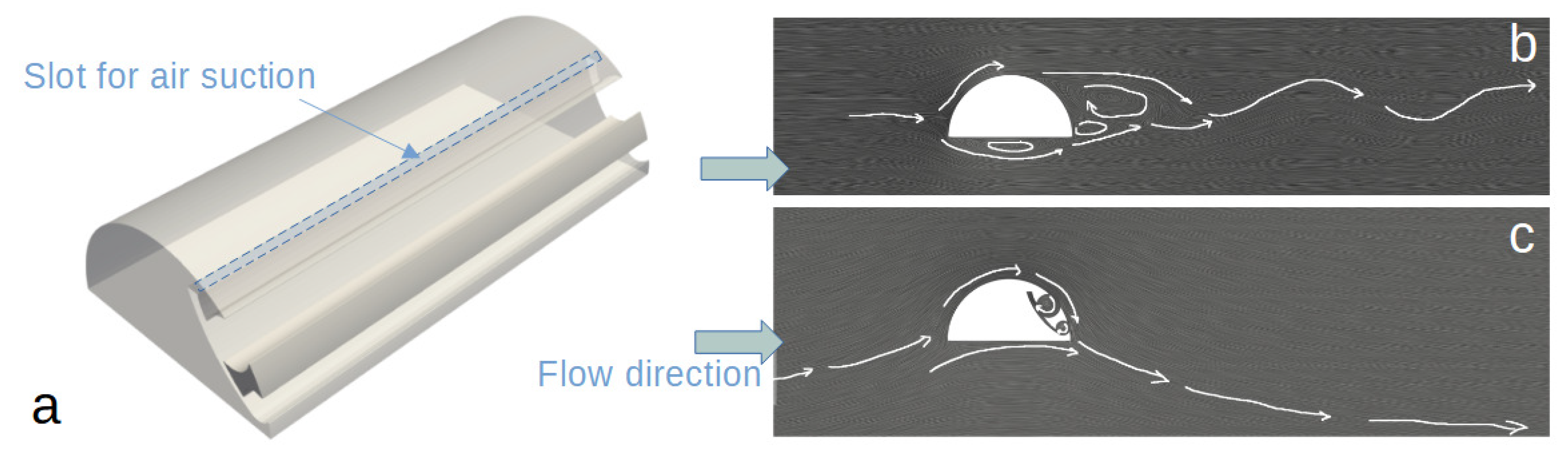

2.2. Computational Grids

Numerical simulations of the turbulent flow over a semi-circular cylinder were conducted using an unstructured, hexahedral-dominated grid with various levels of adaptation (referred to as H0 and displayed in

Figure 3). The computational domain was defined as a rectangular parallelepiped with dimensions

in the

x,

y, and

z directions, respectively. Initially, the computational block was divided into

nodes. Subsequently, the region from

to

was adapted with a coefficient of

. Next, the region from

to

was refined using a uniform cell size of

. The rectangular region with dimensions

to

and from

to

was constructed using a uniform cell size of

. Finally, the last rectangular block with dimensions

to

and from

to

was refined using a uniform cell size of

. Grid adaptation at all levels covered the computational region in the spanwise direction comprehensively. To adequately resolve the boundary layer of BB, a viscous sub-grid was added with a minimum dimensionless cell height of

, an expansion factor of

, and a total of 20 layers. The total grid size amounted to

cells.

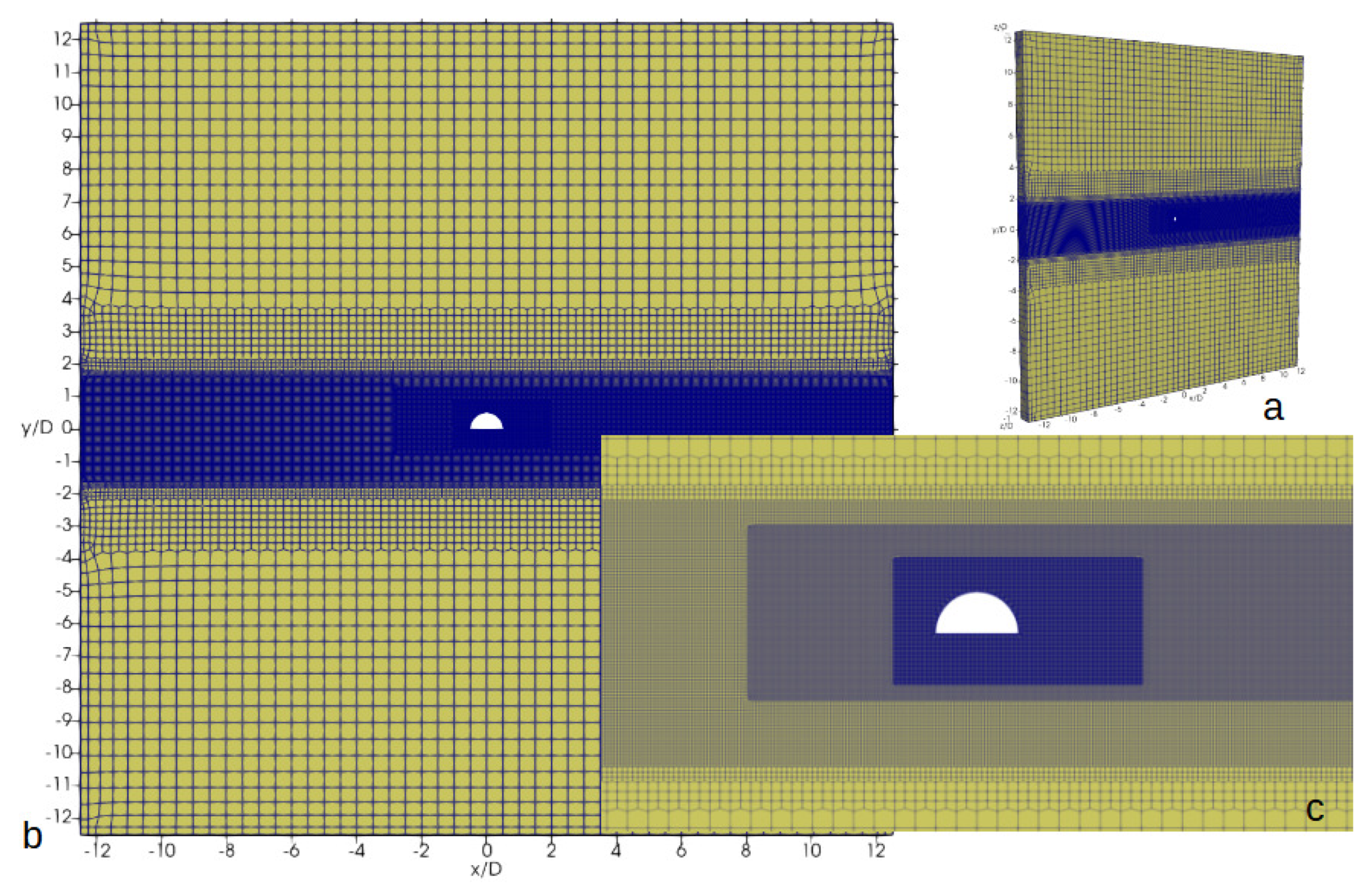

The unstructured, hexahedral-dominated grid used to simulate the flow over BB with the implemented active flow control was designed similarly to the grid for the semi-circular cylinder (referred to as A0 and presented in

Figure 4). The computational domain was defined as a rectangular block with dimensions

, initially seeded with

nodes in the

x,

y, and

z directions, respectively. The region from

to

was refined with a coefficient of

at the next level. The block from

to

was further refined using a uniform cell size of

. Finally, the cylindrical region with a radius of

, located at the center of the Cartesian coordinates, was meshed with a uniform cell size of

. A viscous sub-grid was added to the obstacle with averaged

, an expansion factor of

, and a total of 5 layers. The total grid size amounted to

cells. For the second grid (referred to as A1), the cylindrical region with a radius of

was re-meshed with uniform cell sizes of

, resulting in a total of

cells.

Figure 5 displays the probability function of

and its visualization at the surface of the airfoil for the A1 mesh .

3. Brief Aspects of Mathematical Modeling and Numerical Simulations

3.1. Overview of the Large Eddy Simulation Technique

The Favre-filtered balance equations for mass, momentum, and energy are:

The symbols , p, and represent density, pressure, and velocity, respectively. Enthalpy per unit mass, h, is given by , with as internal energy per unit mass and T as temperature. The notations , , and indicate Reynolds-averaging, Favre-averaging, and filtering operations, respectively.

The conductive flux and viscous stresses are expressed as:

and

where the rate-of-strain tensor,

, is:

Here, viscosity, is calculated by Sutherland’s law and – conductivity.

For completeness, a filtered equation of state (EoS) is provided to close the system of governing equations using the ideal gas law:

Assuming the sub-grid scales incompressibility hypothesis [

18,

19], the SGS stress

and heat flux

can be expressed as follows:

For closure, the

k-equation eddy viscosity SGS model [

22,

65,

83] and its dynamic version are used, based on the SGS kinetic energy,

. The SGS turbulence stresses are expressed as:

with SGS viscosity computed as:

where

is the filter length. The transport equation used to estimate

is:

where production

, diffusion

, and dissipation

are expressed as:

Here,

is the unit tensor,

is the density-weighted stress tensor,

is the deviatoric part of the rate of strain tensor, and model coefficients are

and

[

62]. The dynamic modification, which is used in the present study, can be derived using the Germano identity with another filter kernel of width

(the theoretical background can be found in [

19]).

3.2. Overview Of The Numerical Methodology

Large eddy simulation is performed using the CFD platform Ansys Fluent 2021R1 [

3] (hereinafter, AF). To close the filtered, Favre-averaged Navier-Stokes equations, the dynamic modification of the differential subgrid scale model for the turbulence kinetic energy (

k-model) is used. The numerical platform is based on the finite volume method (FVM) implemented as a pressure-based solver [

24] using a limited central differencing scheme of the second-order (bounded CDS-2) for the velocity, a second-order upwind scheme (SOU) for the remaining nonlinear convective terms and an implicit Euler method (bounded BDF-2) for time integration [

19]. The time integration step is chosen to ensure that the local Courant number is less than one,

. The system of linear algebraic equations is solved using the algebraic multigrid method (AMG) accompanied by the additive correction strategy [

23] and the classical iterative Gauss-Seidel procedure.

The compressible Reynolds-averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) equations are solved using the factorized FVM with a second order accuracy in space and time. The linear system of equations is solved in the same spirit as for LES. All convective terms are approximated using the SOU scheme. To close the system of the favre-averaged Navier-Stokes equations the realizable

k-

turbulence model of Shih [

70] (RKE here and after) is used. More details reader can find in [

35]. For the inviscid simulation the system of Euler equations for a perfect gas with the heat capacity ratio,

, is solved using the Godunov-type FVM solver [

21], where inviscid fluxes are computed using the advection upstream splitting method (AUSM) [

31].

3.3. Boundary And Initial Conditions

The boundary conditions were established to ensure that the free-stream parameters were

and

. For LES, a synthetic turbulence generator, proven effective in the previous work [

43], was used to realistically reproduce the turbulent inlet flow, with the subgrid kinetic energy intensity set to

. Symmetry conditions were applied on the lateral planes, while non-reflecting conditions were set on the other boundaries of the computational domain. For RANS, inlet turbulence was specified using parameters such as intensity (

) and hydraulic diameter (

D). Fixed values for the free stream velocity and total temperature were set at the inlet boundary, while a fixed static pressure was set at the outlet. The body surface was considered adiabatic with no-slip conditions. Simulation of the air suction from the vortex cell system was implemented by setting a fixed static pressure drop of

Pa. The initial conditions corresponded to a sudden stop of the body in the fluid flow, meaning the inlet boundary conditions were initially extended to the entire computational domain. The ideal gas law was used to account for compressibility, with constant molecular viscosity and thermal conductivity. The Prandtl number was taken to be

, and the ratio of specific heat capacities was

.

3.4. Ultimate Analytical Lift Properties of Airfoils in Potential Flows

By analogy to knowing the limits in thermodynamics to understand what is possible, knowing the limits in aerodynamics helps us to estimate the maximum lift we can achieve [

71]. For this purpose we strongly follow the analysis by Smith [

71], when the inviscid potential flows where separation will not occur are assumed and Joukowski airfoil theory is applicable:

where

– the angle of attack and

– the angle determining the maximum airfoil curvature,

, where

f is the max airfoil curvature and

D represents the cord of airfoil . It is worth noting that Equations (

19) are valid when the Chaplygin-Joukowski condition is met at the trailing edge of the airfoil. The given dependencies make it possible to estimate several limiting cases of the lift coefficient for different geometrical shapes:

– flow around a flat-plate airfoil installed at a given angle of attack (see

Figure 6,a):

. The max theoretical value of the lift force of a thin plate is achieved at the angle of attack,

,

-

– flow around a curved plate in the form of a half-circle (see

Figure 6,b). In this case the following values of

can be obtained:

One can see clearly, that the maximum lift coefficient can be achieved for

. Of course, the value of

depends on the length used as a reference. Here, it i assumed that the conventional chord is applied. For a circle, under the imposed assumptions, it is possible to recover

as a limit. In the same spirit, for the half-circle limit of

can be considered. That is the limiting value for any single-element airfoil [

71].

Critical remark. This analysis does not consider the effects of Mach number. As speed increases, high values of lift coefficient () cannot be sustained indefinitely, because soon the surface pressures would drop below absolute zero.

4. Results

In this section, the main results for BB with aerodynamic flow control using LES on the A0 and A1 grids are analyzed, and are indexed as LES-AFC-A0 and LES-AFC-A1, respectively. Also, the complementary run for the semi-circular cylinder without AFC, HC-LES-H0, based on the H0 grid is added for the purpose of comparison.

The characteristic convective time, , is defined as the ratio of the streamwise length of the computational domain () to the free-stream velocity (), represented as . The solution is considered statistically converged when exceeds 3. To ensure statistically independent data, time averaging is conducted over an interval of , with the averaging operator denoted as .

The main results are presented in

Table 1 and

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10 and

Figure 11.

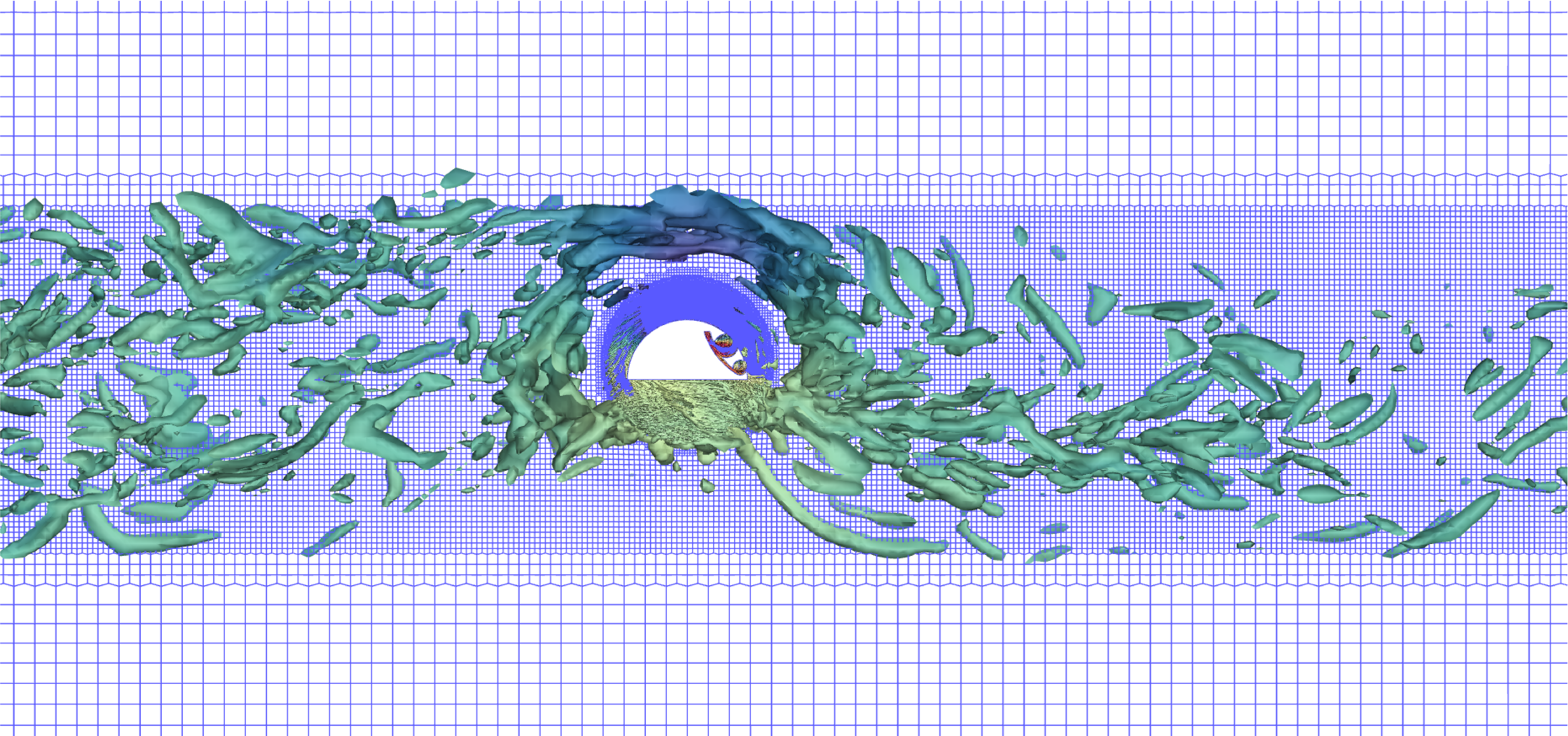

Figure 7 shows the visualization of the instantaneous velocity field using the Q-criterion, clearly depicting the turbulent flow over the object with implemented AFC.

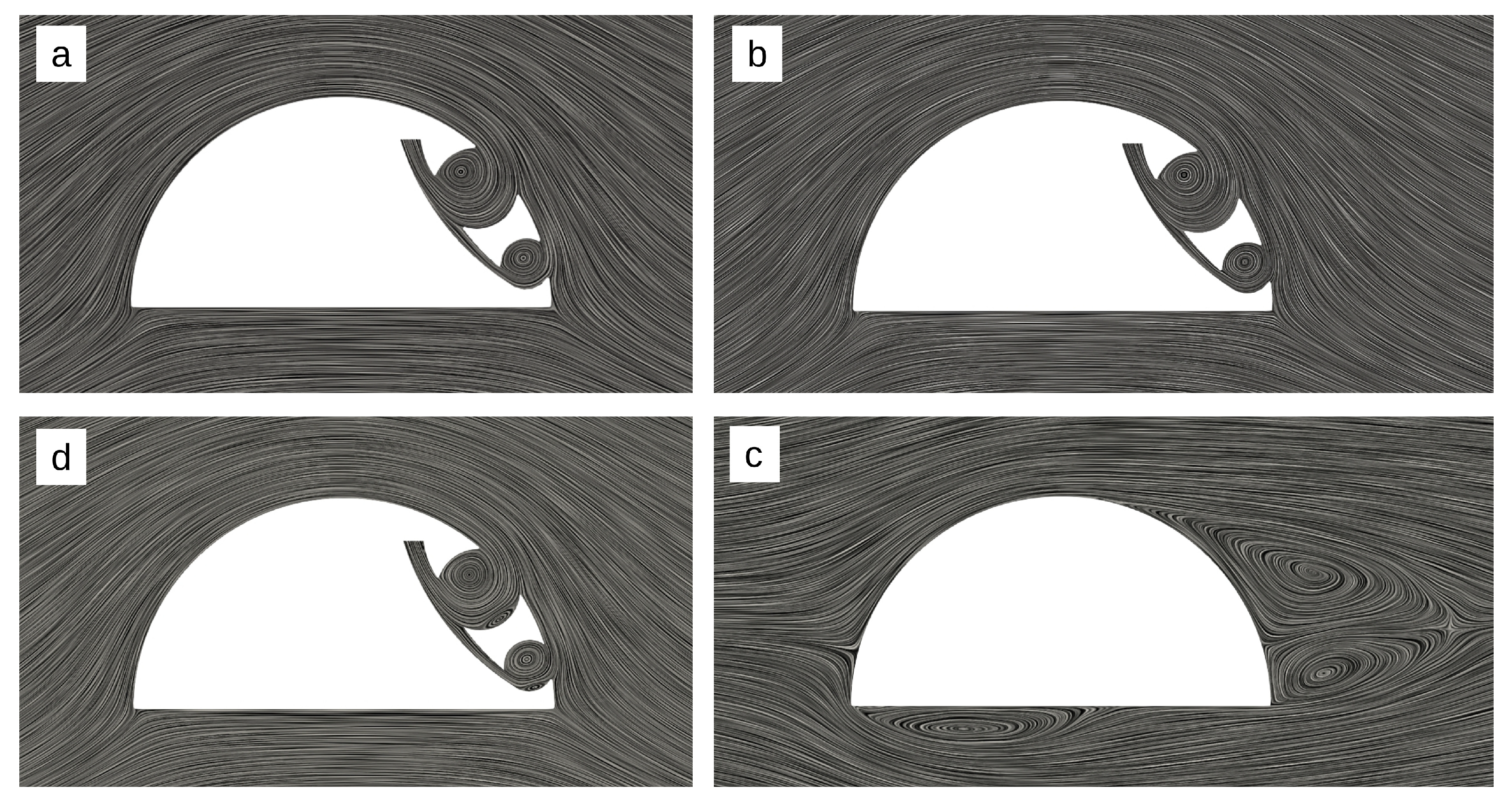

Figure 8a,b displays the time-averaged flow field using the LIC (Line Integral Convolution) technique, demonstrating completely non-separated flow over the concept.

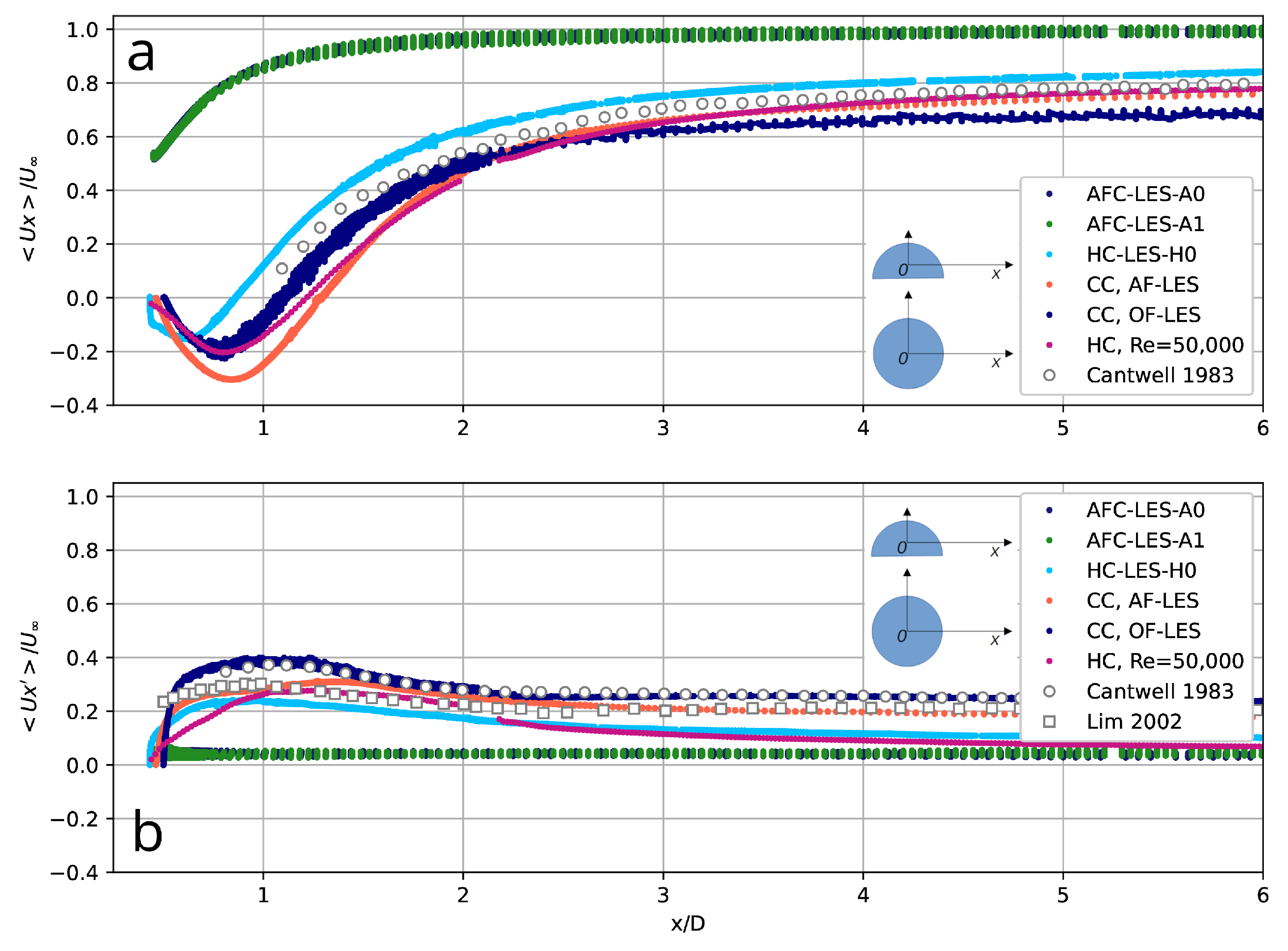

Figure 9 shows the mean values of the streamwise velocity (

) and its fluctuations (

) along the central axial section. For comparison, the values of

and

obtained for the flow past a circular cylinder for

([

44]), a semi-circular cylinder for

([

41]), as well as available experimental data are accumulated. The practically unperturbed flow field over the new concept with AFC predicted numerically is clearly visible.

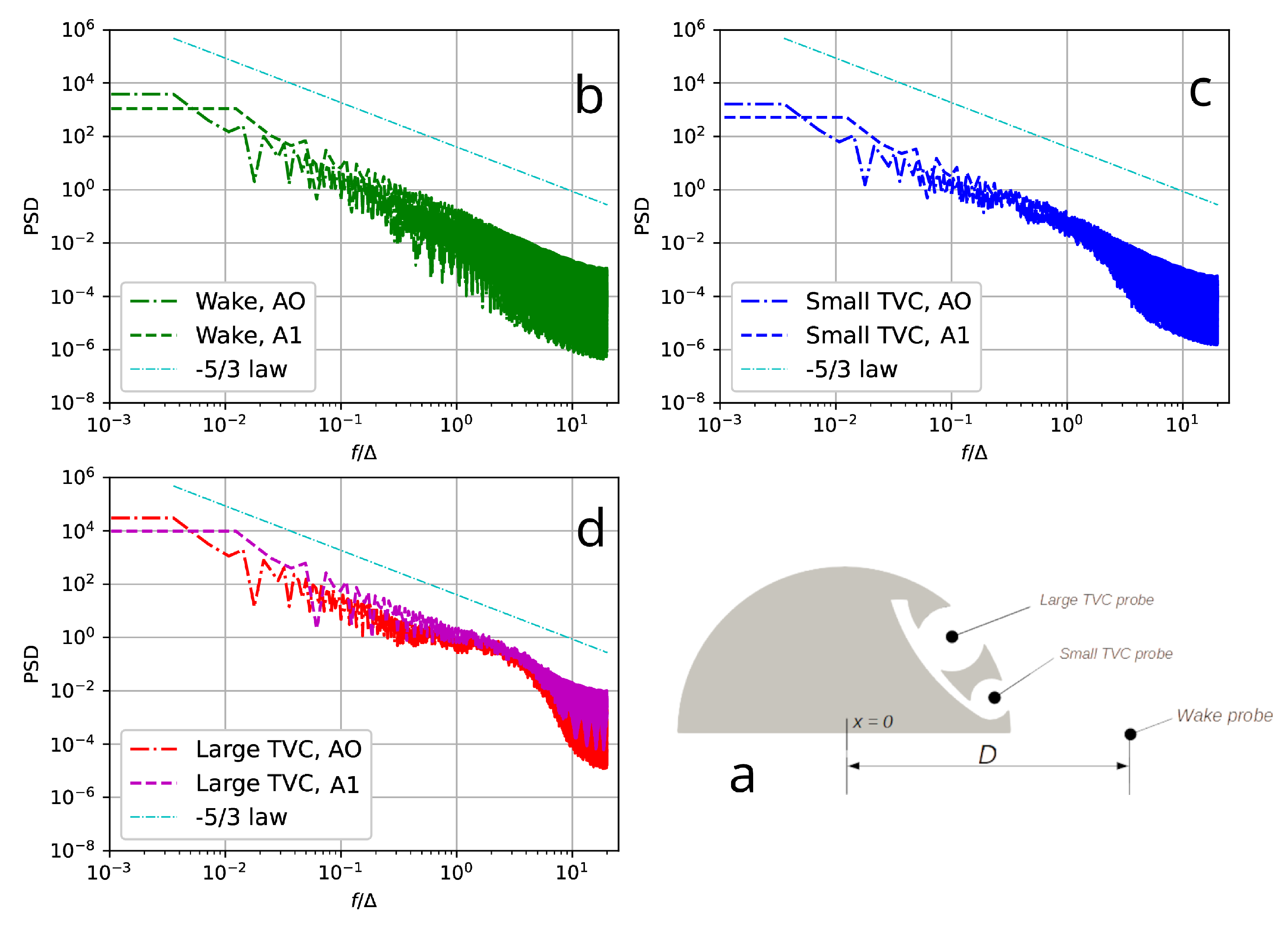

Figure 10 shows the one-dimensional energy spectra of the velocity magnitude obtained at the centers of vortex cells and in the near wake. The spectra obtained on grids A0 and A1 are practically identical, agree well with the universal power law of

, and also show the absence of any characteristic low-frequency oscillations associated with vortex dynamics, both in the near wake and in the trapped vortex cells.

The mean aerodynamic coefficients obtained in both simulations for the concept with AFC were

and

. It is significant that both parameters obtained using two computational grids, A0 and A1, practically coincide, indicating satisfactory grid independence of the results. LES for the semi-circular cylinder reveals:

and

.

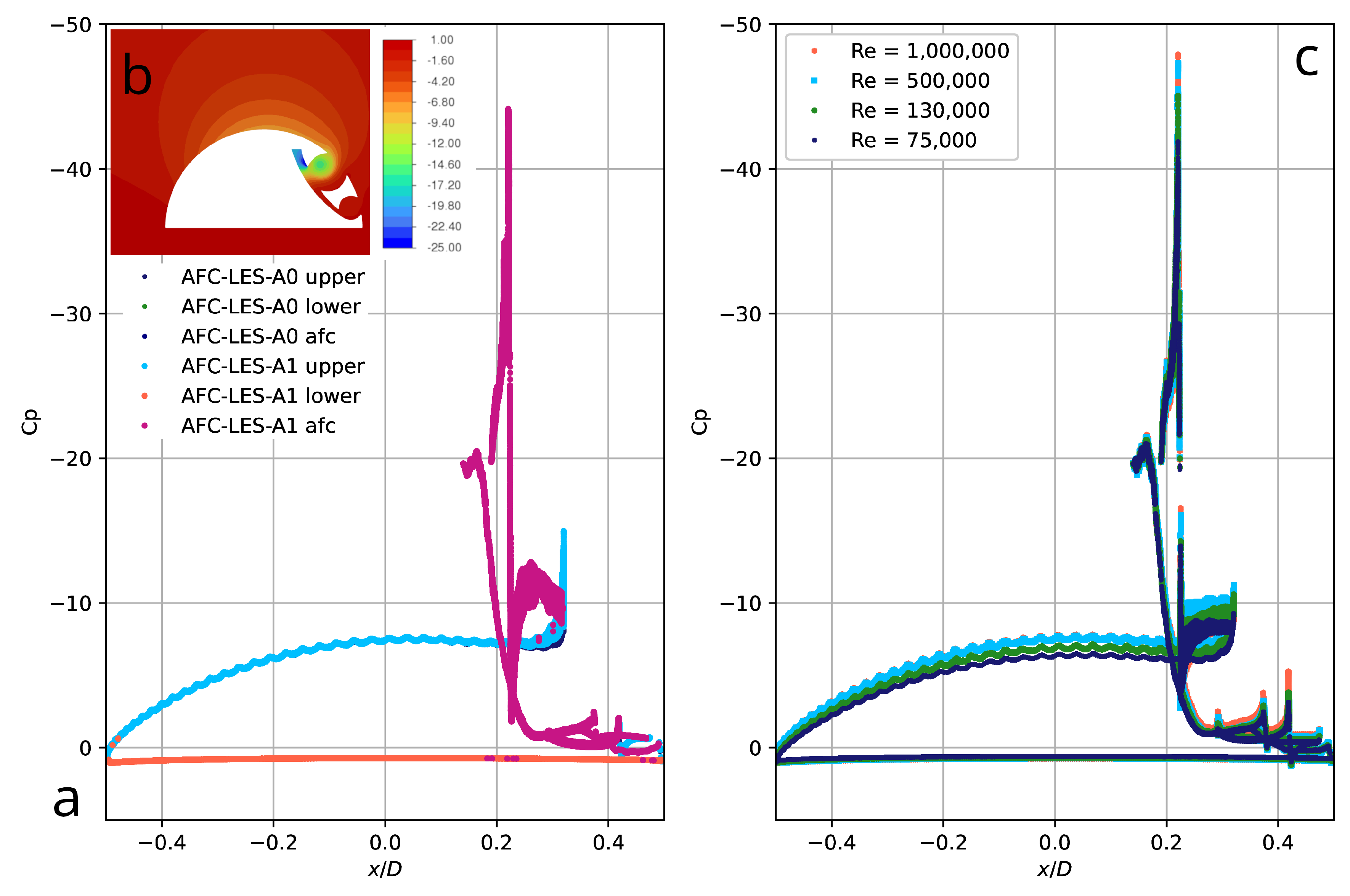

Figure 11,a shows the distribution of the time-averaged pressure coefficient along the streamwise dimension for the lower (pressure), upper (suction), and AFC system surfaces. Contours of the mean pressure coefficient (

Figure 11,b) indicate a strong rarefaction formed above the upper surface of BB and in the vortex cells, which physically justifies a significant increase in lift. The computed

coefficient reaches approximately

of the maximum analytical value. It is worth emphasizing that, in practice, the magnitude of the lift also depends on the Mach number (compressibility of the air), which is ignored in this work. All simulations are performed for a Mach number of 0.05, and the analytical predictions for

are also made without considering compressibility.

It should be noted that although a significant increase in lift is achieved compared to BB without AFC, the drag force of the concept is approximately twice that of the semi-circular cylinder. The coefficient is closely related to the energy losses in the AFC system, which in turn depends on the pressure drop required to effectively suction air out of the vortex cells. In this work, the pressure drop was artificially increased by approximately to ensure the stability of numerical simulations. In practice, a smaller or larger pressure drop will result in correspondingly smaller or larger AFC energy losses. The influence of the pressure drop on the stability of the AFC system and its energy losses was not investigated in this work, although it is one of the critical topics for further optimization and development of the concept.

5. Discussion

It is important to analyze the effects of viscosity on the aerodynamic characteristics of the AFC concept, specifically their dependence on the Reynolds number. To this end, a series of simulations were conducted for discrete Reynolds numbers: , , and using the classical RANS approach. Additionally, to analyze asymptotic behavior, the limiting case for an inviscid gas was studied by solving the Euler equations.

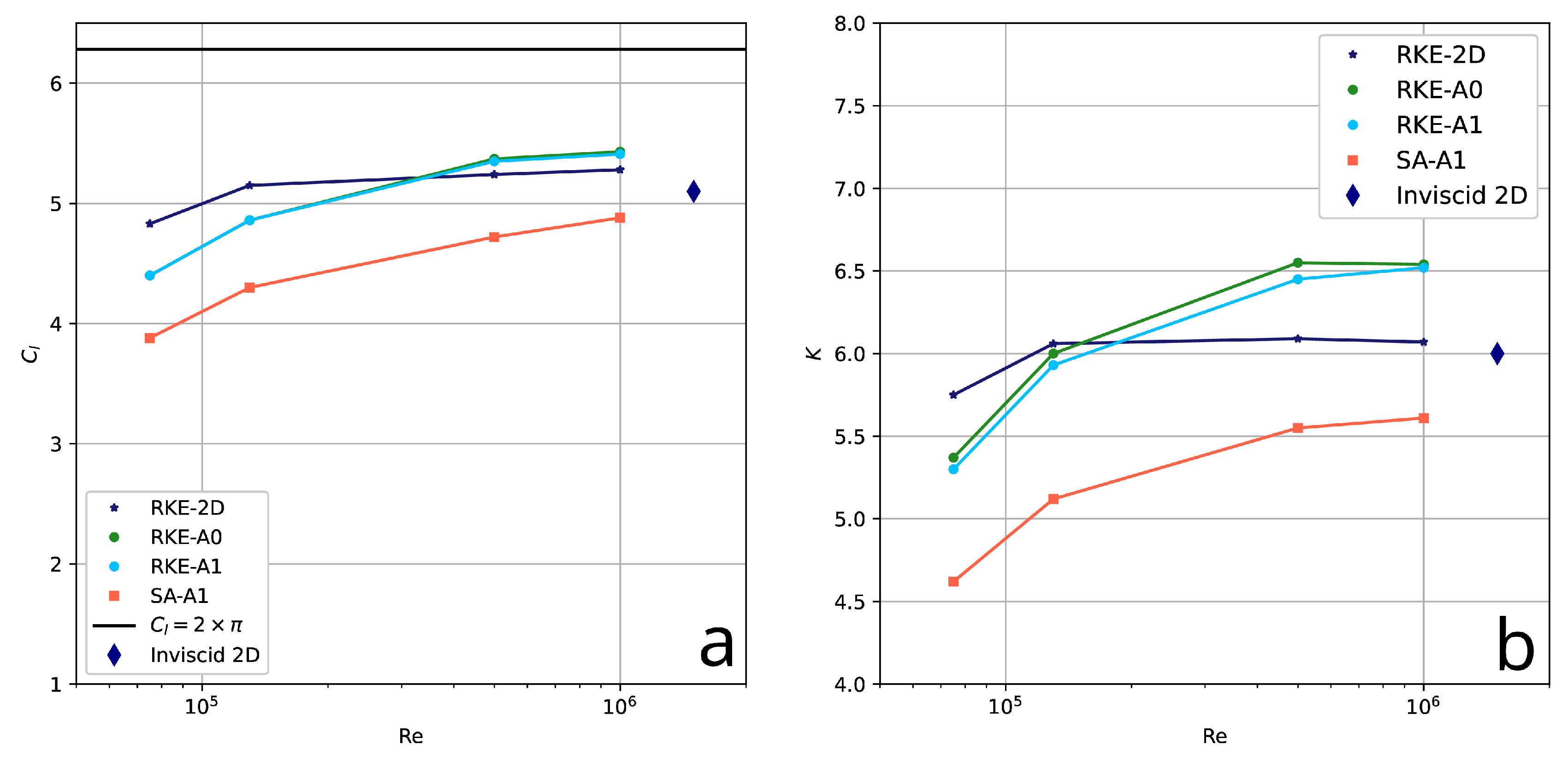

The main results, presented in

Table 2 and

Figure 12, analyze the following: a) influence of two-dimensional versus three-dimensional effects (2D vs. 3D); b) mesh convergence for A0 and A1 grids; c) turbulence modeling: realizable

k-

[

70] vs. Spalart-Allmaras [

73] (SA here and after). The obtained results correlate satisfactorily and show the same trend for the drag and lift coefficients (and, consequently, aerodynamic quality), with values increasing smoothly and linearly with increasing Reynolds number and reaching an asymptotic value. The lift coefficient comes to its maximum value, approximately

of the analytical limit.

To summarize, the following conclusions can be made:

The results obtained in 2D diverge by approximately from the 3D results for Reynolds numbers of and . As the Reynolds number increases, this discrepancy diminishes.

There is almost perfect agreement between the baseline simulations using the realizable k- turbulence model on the A0 and A1 grids, indicating grid independence.

The influence of turbulence models is limited; both RKE and SA models show the same trend but have a systematic shift of around .

For the limiting case of inviscid fluid, the lift coefficient value is about

lower than the values obtained using RKE for a Reynolds number of

. This is explained by vortex breakups or the coexistence of small coherent vortex structures in the trapped vortex cells and additional vortices in the system channels, as demonstrated in

Figure 8,d. The limiting case confirms the general trend.

From the perspective of numerical modeling, satisfactory agreement is achieved between the aerodynamic coefficients, with a minimum difference of for LES and RANS for a Reynolds number of . It is important to emphasize that for both approaches, grid dependence of the solution is practically non-existent. The agreement between the results can be attributed to the consistency of both methodologies and the use of a differential, algebraic equation for the kinetic energy to close the Navier-Stokes equations.

6. Conclusions

In previous work, the concept of a bluff body with aerodynamic flow control using trapped vortex cells was tested at a Reynolds number of . This resulted in a significant improvement in lift and aerodynamic quality (from to ) and demonstrated nearly unseparated flow over the body, except for the attached recirculation zone and two saddle-shaped vortices from the lower and lateral surfaces.

In this paper, the concept is further optimized. The free-stream Reynolds number was increased to , while the Mach number remained the same. To study the properties of the aerodynamic flow control system, the bluff body design was simplified by replacing the lateral surfaces with simple symmetrical planes. Several optimization iterations were conducted to determine the best configuration of the channel and the location of the vortex cells. As a result, nearly non-separating flow over the bluff body was achieved, providing an ultimate lifting force of about of the maximum analytical value ().

The next logical step was to study the influence of viscosity effects (or Reynolds number). It was shown that the aerodynamic properties of the developed model are practically independent of viscosity effects. Over a wide range of Reynolds numbers (), a slight increase in lift and aerodynamic quality (with an almost constant drag coefficient) is observed, with a gradual (linear) approach to an asymptotic value.

It is noteworthy that the aerodynamic drag of the concept increased by about compared to a conventional thick airfoil (semi-circular cylinder). This increase is likely due to the consistent pressure drop set in all simulations for air suction from the vortex cells. Additionally, the pressure drop value was slightly overestimated to ensure the stability of the numerical simulations. The study of the pressure drop’s influence on the aerodynamic characteristics of the object remained beyond the scope of this work but is a fundamental topic for further optimization.

Also, a logical continuation of this work involves further study of compressibility effects (Mach numbers) and detailed verification of the numerical methodology for critical and super-critical regimes over different bluff bodies.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AF |

Ansys Fluent |

| AMG |

Algebraic Multigrid Method |

| BB |

Bluff-Body |

| BDF |

Backward Differencing Formula |

| CC |

Circular Cylinder |

| CDS |

Central Differencing Scheme |

| CFD |

Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| CRANE |

Control of Revolutionary Aircraft with Novel Effectors |

| FFT |

Fast Fourier transform |

| FVM |

Finite Volume Method |

| GAMG |

Geometric Multigrid Method |

| HC |

Semi-circular Cylinder |

| LES |

Large Eddy Simulation |

| LIC |

Line Integral Convolution |

| PDF |

Probability Density Distribution |

| SOU |

Second-order Upwind Scheme |

| TVC |

Trapped Vortex Cell |

References

- Alberti, T., Daviaud, F., Donner, R.V., Dubrulle, B., Faranda, D., Lucarini, V., Chameleon attractors in a turbulent flow, Chaos Solitons Fractals, 168, 113195 (2023).

- Achenbach, E., Distribution of local pressure and skin friction around a circular cylinder in cross-flow up to Re = 5 × 106, J Fluid Mech, 34(4), 625-639 (1968) . [CrossRef]

- ANSYS FLUENT 2021SRb. Theory guide. Tech. rep., Ansys Inc. (2021).

- Bearman, P.W., On vortex shedding from a circular cylinder in the critical Reynolds number regime, J Fluid Mech, 37, 577-85 (1969) . [CrossRef]

- Bloor, M., The transition to turbulence in the wake of a circular cylinder, J Fluid Mech, 19, 290-304 (1964) . [CrossRef]

- Bharghava, D.S.N., Jana, T., Kaushik, M., A survey on synthetic jets as active flow control, AS 7, 435-451 (2024) . [CrossRef]

- Breuer, M., A challenging test case for large eddy simulation: High Reynolds number circular cylinder flow, Int J Heat Fluid Flow, 21(5), 648-654 (2000) . [CrossRef]

- Brogi, F., Bnà, S., Boga, G., Amati, G., Esposti Ongaro, T., Cerminara, M., On floating point precision in computational fluid dynamics using OpenFOAM, Future Generation Computer Systems, 152, 1-16 (2024) . [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y., Tamura, T., Numerical investigations into effects of three-dimensional wake patterns on unsteady aerodynamic characteristics of a circular cylinder at Re=1.3 × 105, J Fluids Struct, 59, 351-369 (2015) . [CrossRef]

- Cantwell, B., Coles, D., An experimental study of entrainment and transport in the turbulent near wake of a circular cylinder, J Fluid Mech, 136, 321-374 (1983) . [CrossRef]

- Capone, A., Klein, C., Felice, F.D., Miozzi, M., Phenomenology of a flow around a circular cylinder at sub-critical and critical Reynolds numbers, Phys Fluids, 28(7) (2016) . [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.F. and Ballengee, D.B., Vortex shedding from circular cylinders in an oscillating freestream, AIAA J, 9(2) (1971) . [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-L., Huang, Y., Chen, C., Yu, H., Gao, D., Review of active control of circular cylinder flow, Ocean Eng., 258, 111840 (2022) . [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, C., and F. Pellegrini, F., PT-Scotch: A tool for efficient parallel graph ordering, Parallel Comput, 34, 318-331 (2008) . [CrossRef]

- Delany, K. and Sorensen, N.E., Low-speed drag of cylinders of various shapes, NACA-TM-3038 (1956).

- Derakhshandeh, J.F., Alam, Md. M., A review of bluff body wakes, Ocean Eng., 182, 475-488 (2019) . [CrossRef]

- Dong, S., Karniadakis, G.E., Ekmekci, A., Rockwell, D., A combined direct numerical simulation particle image velocimetry study of the turbulent air wake, J Fluid Mech, 569, 185-207 (2006).

- Garnier, E., Adams, N., Sagaut, P.: Large eddy simulation for compressible flows. Springer, New York(2009).

- Geurts, B, Elements of direct and large-eddy simulation, R.T.Edwards, Philadelphia (2004).

- Greenblatt, D. and Williams, D.R., Flow control for Unmanned Air Vehicles, Annual Review Fluid Mech, 54, 383-412 (2022) . [CrossRef]

- Godunov, S.K., I. Bohachevsky, I., Finite difference method for numerical computation of discontinuous solutions of the equations of fluid dynamics, Matematičeskij sbornik, 47(89) (3), 271-306 (1959).

- Horiuti, K., Large eddy simulation of turbulent channel flow by one-equation modeling, J Phys Soc Jpn, 54(8), 2855-2865 (1985) . [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson B, Raithby G. A multigrid method based on the additive correction strategy, J Numer Heat Transfer, 9, 511-37 (1986).

- Issa, R., Solution of the implicitly discretized fluid flow equations by operator splitting, J Comput Phys, 62, 40-65 (1986).

- George Karypis, G., and Kumar, V., Multilevel k-way partitioning scheme for irregular graphs, J Parallel Dist Comput, 48(1), 96-129 (1998).

- Kasper, W., Aircraft wing with vortex generation, US Patent No. 3831885 (1974).

- Kravchenko, A., Moin, P., Numerical studies of flow over a circular cylinder at Re = 3900, Phys Fluids, 12(2), 403-417 (2000) . [CrossRef]

- Lee, S., Zhao, Y., Luo, J. , Zou, J., Zhang, J., Zheng, Y., Zhang, Y., A Review of Flow Control Strategies for Supersonic/Hypersonic Fluid Dynamics, Aerosp Res Commun, 2 (2024).

- Lekkala, M.R., Latheef, M., Jung, J.H., Coraddu, A., Zhu, H., Srinil, N., Lee, B.-H., Kim, D.K., Recent advances in understanding the flow over bluff bodies with different geometries at moderate Reynolds numbers, Ocean Eng., 261, 111611 (2022).

- Hee-Chang Lim, H.-C., Lee, S-J., Flow control of circular cylinders with longitudinal grooved surfaces, AIAA J, 40(10), 2027-2036 (2002).

- Liou, M.-S., Steffen, C., A new flux splitting scheme, J Comput Phys, 107, 23-39 (1993) . [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, T.P., James, M., Large eddy simulations of a circular cylinder at Reynolds numbers surrounding the drag crisis, Applied Ocean Research, 59, 676-686 (2016) . [CrossRef]

- Lyapunov, A.M., The general problem of the stability of motion, Int J Control, 55(3), 521-790 (1992) . [CrossRef]

- Lysenko, D.A., Ertesvåg, I.S., Rian, K.E., Large-eddy simulation of the flow over a circular cylinder at Reynolds number 3900 using the OpenFOAM toolbox, Flow Turbul Combust, 89, 491-518 (2012) . [CrossRef]

- Lysenko, D.A., Ertesvåg, I.S., Rian, K.E., Modeling of turbulent separated flows using OpenFOAM, Comput, Fluids, 80, 408-422 (2013).

- Lysenko, D.A., Ertesvåg, I.S., Rian, K.E., Large-eddy simulation of the flow over a circular cylinder at Reynolds number 2 × 104, Flow Turbul Combust, 92, 673-698 (2014) . [CrossRef]

- Lysenko, D.A., Ertesvåg, I.S., Rian, K.E., Numerical simulations of the Sandia flame D using the Eddy Dissipation Concept, Flow Turbul Combust, 93, 665-687 (2014) . [CrossRef]

- Lysenko, D.A., Ertesvåg, I.S., Rian, K.E., Towards simulation of far-field aerodynamic sound from a circular cylinder using OpenFOAM, I J Aeroacoustics, 13(1), 141 – 168 (2014).

- Lysenko, D.A., Ertesvåg, I.S., Reynolds-Averaged, Scale-Adaptive and Large-Eddy Simulations of Premixed Bluff-Body Combustion Using the Eddy Dissipation Concept, Flow Turbulence Combust, 100, 721-768 (2018) . [CrossRef]

- Lysenko, D.A., Ertesvåg, I.S., Assessment of algebraic subgrid scale models for the flow over a triangular cylinder at Re = 45000, Ocean Eng, 222 (2021) 108559 . [CrossRef]

- Lysenko, D.A., Donskov, M., Ertesvåg, I.S., Large-eddy simulations of the flow over a semi-circular cylinder at Re = 50000, Comput Fluids, 228 (2021) 10505 . [CrossRef]

- Lysenko, D.A., Donskov, M., Ertesvåg, I.S., Large-eddy simulations of the flow past a bluff-body with active flow control based on trapped vortex cells at Re = 50000, Ocean Eng, 280, 114496 (2023).

- Lysenko, D.A. Free stream turbulence intensity effects on the flow over a circular cylinder at Re = 3900: bifurcation, attractors and Lyapunov metric, Ocean Eng, 287, 115787 (2023) . [CrossRef]

- Lysenko, D.A. Large-Eddy Simulation of the Flow Past a Circular Cylinder at Re = 130,000: Effects of Numerical Platforms and Single- and Double-Precision Arithmetic, Fluids, 10, 4 (2025) . [CrossRef]

- Ma, X., Karamanos, G.-S., Karniadakis, G.E., Dynamics and low-dimensionality of a turbulent near wake, J Fluid Mech, 410, 29-65 (2000) . [CrossRef]

- Mariaprakasam, R.D.R., Mat, S., Samin, P.M., Othman, N., Wahid, M., Said, M., Review on flow controls for vehicles aerodynamic drag reduction, J Adv Res Fluid Mech Therm Sci, 101(1), 11-36 (2023) . [CrossRef]

- Nastac, G., Labahn, J.W., Magri, L., Ihme, M., Lyapunov exponent as a metric for assessing the dynamic content and predictability of large-eddy simulations, Phys Rev Fluids, 2, 094606 (2017) . [CrossRef]

- Norberg, C., Effects of Reynolds number and a low intensity freestream turbulence on the flow around a circular cylinder, Publication No. 87/2, Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden (1987).

- Norberg, C., Flow around rectangular cylinders: Pressure forces and wake frequencies, J Wind Eng Ind Aerodyn, 49(1-3), 187-196 (1993) . [CrossRef]

- Norberg, C., Experimental investigation of the flow around a circular cylinder: Influence of aspect ratio, J Fluid Mech, 258, 287-316 (1994) . [CrossRef]

- Norberg, C. Flow around a circular cylinder: Aspects of fluctuating lift, J Fluids Struct, 15, 459-69 (2001) . [CrossRef]

- Ong, L., Wallace, J., The velocity field of the turbulent very near wake of a circular cylinder, Exp Fluids, 20, 441-453 (1996) . [CrossRef]

- Oseledets, V.I., Multiplicative ergodic theorem. Characteristic Lyapunov exponents of dynamical systems, Tr. Mosk. Mat. Obs., 19, 179-210 (1968).

- Parnaudeau, P., Carlier, J., Heitz, D., Lamballais, E., Experimental and numerical studies of the flow over a circular cylinder at Reynolds number 3900, Phys Fluids, 20 (8), 085101 (2008).

- Plata, M., Lamballais, E., Naddei, F., On the performance of a high-order multiscale DG approach to LES at increasing Reynolds number, Comput. Fluids, 194, 104306 (2019) . [CrossRef]

- Rashidi, S., Hayatdavoodi, M., Esfahani, J.A., Vortex shedding suppression and wake control: A review, Ocean Eng., 126, 57-80 (2016) . [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A., Williamson, C.H.K., The instability of the shear layer separating from a bluff body, J Fluid Mech, 333, 375-402 (1997) . [CrossRef]

- Ringleb, F.O., Separation control by trapped vortices. In: Boundary Layer and Flow Control, Ed. Lachmann G.V., Pergamon Press (1961).

- Roshko, A., On the drag and shedding frequency of two-dimensional bluff bodies. In: National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, NACA-TN-3169 (1953).

- Ruelle, D., Takens, F., On the nature of turbulence, Communications Math Phys, 23(4), 343-344 (1971).

- Sadeh, W.Z., Saharon, D.B., Turbulence effect on crossflow around a circular cylinder at subcritical Reynolds numbers, NASA-CR-3622 (1982).

- Sagaut, P., 2006. Large eddy simulation for incompressible flows, third ed. Springer Berlin.

- Savitsky, A.I., Schukin, L.N., Karelin, V.G., Mass, A.M., Pushkin, R.M., Shibamov, A.P., Schukin, I.L., Fischenko, S.V., Method for controlling boundary layer on an aerodynamic surface of a flying vehicle, US Patent No. 5417391 (1995).

- Schewe, G., On the force fluctuations acting on a circular cylinder in crossflow from subcritical up to transcritical Reynolds numbers, J Fluid Mech, 133, 265-285 (1983) . [CrossRef]

- Schumann, U., Subgrid scale model for finite difference simulations of turbulent flows in plane channels and annuli, J Comput Phys, 18, 376-404 (1975) . [CrossRef]

- Sedda, S., Sardu, C., Lasagna, D., Iuso, G., Donelli, R.S., Gregorio, F. De., Trapped vortex cell for aeronautical applications: Flow analysis through PIV and Wavelet transform tools, 10th Pacific Symposium on Flow Visualization and Image Processing, Naples, Italy (2015).

- Shanbhogue, S.J., Husain, S., Lieuwen, T., Lean blowoff of bluff body stabilized flames: Scaling and dynamics, Prog Energy Combust Sci, 35, 98-120 (2009) . [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P., Chung, W.T., Akoush, B., Ihme, M., A Review of Physics-Informed Machine Learning in Fluid Mechanics, Energies, 16, 2343 (2023) . [CrossRef]

- Shih, W.C.L., Wang, C., Coles, D., Roshko, A., Experiments on flow past rough circular cylinders at large Reynolds numbers, J Wind Eng Ind Aerodynamics, 49(1-3), 351-368 (1993) . [CrossRef]

- Shih, T.H., Liou, W., Shabbir, A., Yang, Z., Zhu, J. A new k eddy-viscosity model for high Reynolds number turbulent flows - model development and validation, J Comput Fluids 24(3), 227-38 (1995).

- Smith, A.M.P., High lift aerodynamics, AIAA Paper No. 74939 (1974) . [CrossRef]

- Son, J., Hanratty, T., Velocity gradients at the wall for flow around a cylinder at Reynolds numbers from 5 × 103 to 105, J Fluid Mech, 35, 353-368 (1969) . [CrossRef]

- Spalart, P. and S. Allmaras, S., A one-equation turbulence model for aerodynamic flows, Technical Report AIAA-92-0439 (1992).

- Szepessy, S., Bearman, P.W., Aspect ratio and end plate effects on vortex shedding from a circular cylinder, J Fluid Mec, 234, 191-217 (1992) . [CrossRef]

- Takens, F., Detecting strange attractors in turbulence, 898, 366-381 (1981).

- Tayebi, A., Torabi, F., Flow control techniques to improve the aerodynamic performance of Darrieus vertical axis wind turbines: A critical review, J Wind Eng Indust Aero, 252, 105820 (2024) . [CrossRef]

- Welch, P., The use of fast Fourier transform for the estimation of power spectra: A method based on time averaging over short, modified periodograms, IEEE Trans Audio Electroacoust, 15(6), 70–73 (1967) . [CrossRef]

- Weller, H.G., Tabor, G., Jasak, H., Fureby, C., A tensorial approach to computational continuum mechanics using object-oriented techniques, J Comput Phys, 12(6), 620-631 (1998) . [CrossRef]

- Wen, P. and Qiu, W., Numerical studies of VIV of a smooth cylinder. In: Proceedings of the 27th ITTC workshop on wave run-up and vortex shedding (2013).

- Wesseling, P., Oosterlee, C.W., Geometric multigrid with applications to computational fluid dynamics, Comput. Appl. Math., 128, 311-334 (2001) . [CrossRef]

- West, G.S., Apelt, C.J., Measurements of fluctuating pressures and forces on a circular cylinder in the Reynolds number range 104 to 2.5 × 105, J Fluids Structures, 7(3), 227-244 (1993) . [CrossRef]

- Yeon, S.M., Yang, J., Stern, F., Large-eddy simulation of the flow past a circular cylinder at sub- to super-critical Reynolds numbers, Applied Ocean Research, 59, 663-675 (2016) . [CrossRef]

- Yoshizawa, A., Statistical theory for compressible shear flows, with the application to subgrid modelling, Phys Fluids, 29(2152), 1416-1429 (1986).

Figure 1.

Key design characteristics of a thick airfoil: with and without Trapped Vortex Cells. x, y and z are Cartesian coordinates in the longitudinal, vertical and spanwise directions

Figure 1.

Key design characteristics of a thick airfoil: with and without Trapped Vortex Cells. x, y and z are Cartesian coordinates in the longitudinal, vertical and spanwise directions

Figure 2.

General view of a bluff body with the integrated active flow control system and locations of the surface for air suction (a). The flow mechanics over the thick airfoil (b) and airfoil with AFC (c)

Figure 2.

General view of a bluff body with the integrated active flow control system and locations of the surface for air suction (a). The flow mechanics over the thick airfoil (b) and airfoil with AFC (c)

Figure 3.

General view of the baseline mesh and computational domain (a,b) and its frontal view and zoom in the vicinity of a semi-circular cylinder (c).

Figure 3.

General view of the baseline mesh and computational domain (a,b) and its frontal view and zoom in the vicinity of a semi-circular cylinder (c).

Figure 4.

General view of the baseline mesh and computational domain (a,b) and its frontal view and zoom in the vicinity of the semi-circular cylinder with AFC (c).

Figure 4.

General view of the baseline mesh and computational domain (a,b) and its frontal view and zoom in the vicinity of the semi-circular cylinder with AFC (c).

Figure 5.

PDF distributions of (a) and its iso-contours (b) at the surface of the bluff-body with AFC, computed for the mesh A1.

Figure 5.

PDF distributions of (a) and its iso-contours (b) at the surface of the bluff-body with AFC, computed for the mesh A1.

Figure 6.

Geometrical parameters of an idealized airfoil: a flat-plate (a) and half-circle (b).

Figure 6.

Geometrical parameters of an idealized airfoil: a flat-plate (a) and half-circle (b).

Figure 7.

Instantaneous flow visualization over BB with integrated aerodynamic control system (LES-AFC-A1) at . Iso-surfaces of the Q-criterion (, where S is the strain rate and is the vorticity).

Figure 7.

Instantaneous flow visualization over BB with integrated aerodynamic control system (LES-AFC-A1) at . Iso-surfaces of the Q-criterion (, where S is the strain rate and is the vorticity).

Figure 8.

LIC visualization of the the flow over a bluff-body with integrated aerodynamic control system at : LES-AFC-A0 (a), LES-AFC-A0 (b) and LES-HC-H0 (c). LIC flow pattern for the specific case using an inviscid gas assumption, when (d).

Figure 8.

LIC visualization of the the flow over a bluff-body with integrated aerodynamic control system at : LES-AFC-A0 (a), LES-AFC-A0 (b) and LES-HC-H0 (c). LIC flow pattern for the specific case using an inviscid gas assumption, when (d).

Figure 9.

Distribution of the mean streamwise velocity (a) and its RMS values along the central axis for the flow over a bluff-body with and without AFC at

. Supplementary data are provided for HC at

[

41] and CC at

[

44], respectively. Experimental data are included from Cantwell and Coles [

10] and Lim and Lee [

30].

Figure 9.

Distribution of the mean streamwise velocity (a) and its RMS values along the central axis for the flow over a bluff-body with and without AFC at

. Supplementary data are provided for HC at

[

41] and CC at

[

44], respectively. Experimental data are included from Cantwell and Coles [

10] and Lim and Lee [

30].

Figure 10.

One-dimensional energy spectra of the velocity magnitude computed for an obstacle with AFC at : general scheme (a) of the measurement probe locations in the near wake (b) and in the centers of the trapped vortex cells (c,d).

Figure 10.

One-dimensional energy spectra of the velocity magnitude computed for an obstacle with AFC at : general scheme (a) of the measurement probe locations in the near wake (b) and in the centers of the trapped vortex cells (c,d).

Figure 11.

Distribution of the mean pressure coefficient (a) over the lower (pressure), top (suction) and AFC surfaces of the concept with AFC at obtained by AFC-LES-A0 and AFC-LES-A1, iso-contours of the mean pressure coefficient (b) and dependence of the mean pressure coefficient from Reynolds number (c) computed using the RANS approach.

Figure 11.

Distribution of the mean pressure coefficient (a) over the lower (pressure), top (suction) and AFC surfaces of the concept with AFC at obtained by AFC-LES-A0 and AFC-LES-A1, iso-contours of the mean pressure coefficient (b) and dependence of the mean pressure coefficient from Reynolds number (c) computed using the RANS approach.

Figure 12.

Reynolds number dependence of lift coefficient (a) and aerodynamic quality (b): summary of RANS simulations from

Table 2.

Figure 12.

Reynolds number dependence of lift coefficient (a) and aerodynamic quality (b): summary of RANS simulations from

Table 2.

Table 1.

Main results: the mean drag, lift coefficients and the aerodynamic quality.

Table 1.

Main results: the mean drag, lift coefficients and the aerodynamic quality.

| Run |

|

|

|

|

| LES-AFC-A0 |

0.870 |

5.094 |

5.855 |

|

| LES-AFC-A1 |

0.875 |

5.092 |

5.819 |

|

| LES-HC-H0 |

0.387 |

-0.883 |

-2.152 |

|

Table 2.

Summary of the RANS cases investigating the sensitivity of the AFC concept to Reynolds number: TM – turbulence model, Mesh – 2D, A0 or A1, , and K represent drag, lift coefficients and aerodynamic quality, respectively

Table 2.

Summary of the RANS cases investigating the sensitivity of the AFC concept to Reynolds number: TM – turbulence model, Mesh – 2D, A0 or A1, , and K represent drag, lift coefficients and aerodynamic quality, respectively

|

TM |

Mesh |

|

|

|

|

|

SA |

A1 |

0.84 |

3.88 |

4.62 |

75 |

| SA |

A1 |

0.84 |

4.3 |

5.12 |

130 |

| SA |

A1 |

0.85 |

4.72 |

5.55 |

500 |

| SA |

A1 |

0.87 |

4.88 |

5.61 |

1,000 |

|

RKE |

A0 |

0.82 |

4.4 |

5.37 |

75 |

| RKE |

A0 |

0.81 |

4.86 |

6.00 |

130 |

| RKE |

A0 |

0.82 |

5.37 |

6.55 |

500 |

| RKE |

A0 |

0.83 |

5.43 |

6.54 |

1,000 |

|

RKE |

A1 |

0.83 |

4.4 |

5.30 |

75 |

| RKE |

A1 |

0.82 |

4.86 |

5.93 |

130 |

| RKE |

A1 |

0.83 |

5.35 |

6.45 |

500 |

| RKE |

A1 |

0.83 |

5.41 |

6.52 |

1,000 |

|

RKE |

2D |

0.84 |

4.83 |

5.75 |

75 |

| RKE |

2D |

0.85 |

5.15 |

6.06 |

130 |

| RKE |

2D |

0.86 |

5.24 |

6.09 |

500 |

| RKE |

2D |

0.87 |

5.28 |

6.07 |

1,000 |

|

Inviscid |

2D |

0.85 |

5.1 |

6.00 |

∞ |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).