Submitted:

07 March 2025

Posted:

07 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Key Concepts About Inflammation in Aged Individuals

2.1. The Concept of Inflammaging

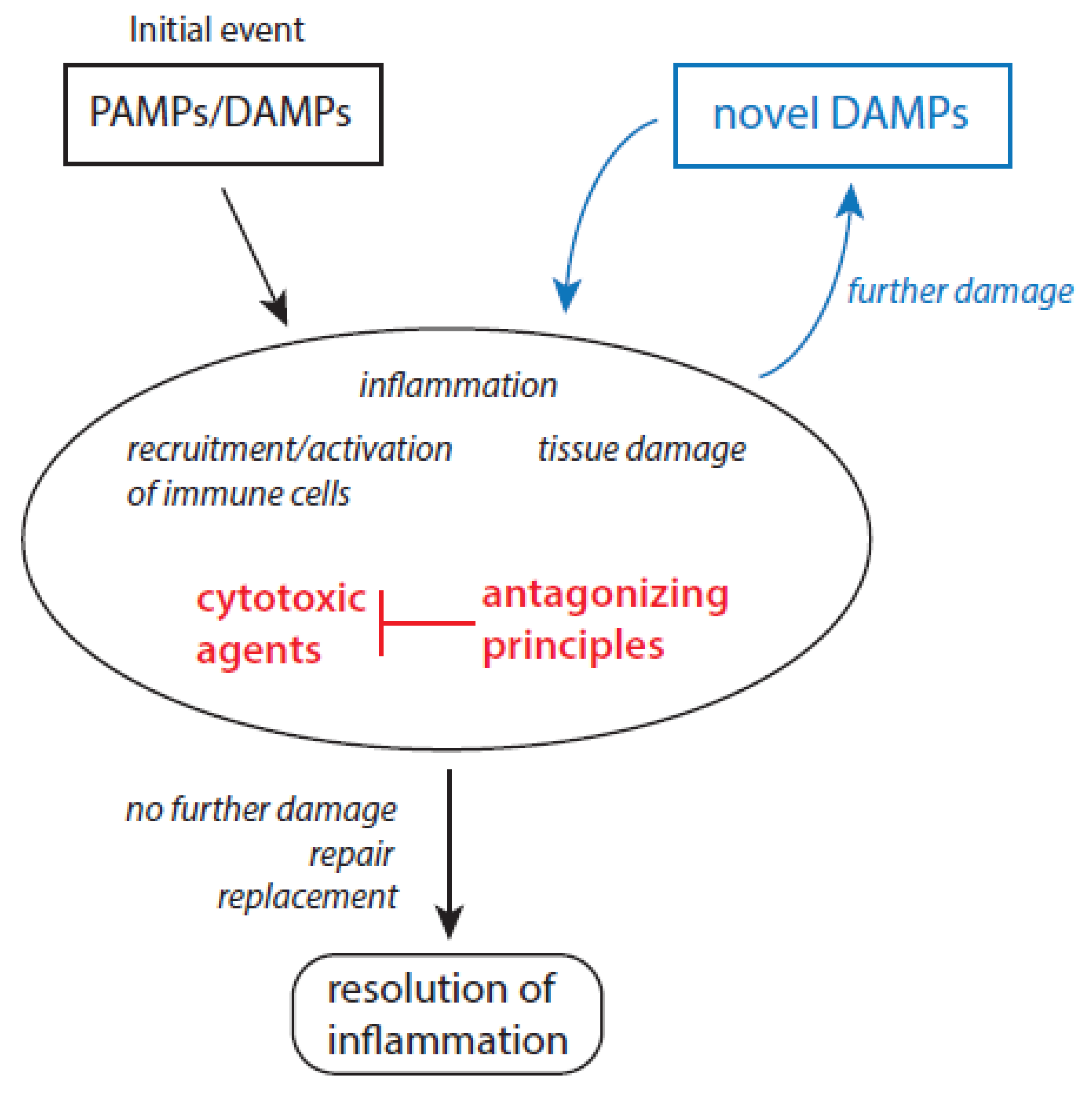

2.2. Molecular Patterns and Host-Derived Cytotoxic Agents in Inflammation

3. Peculiarities of the Energy Metabolism and Oxidative Stress in Aged Individuals

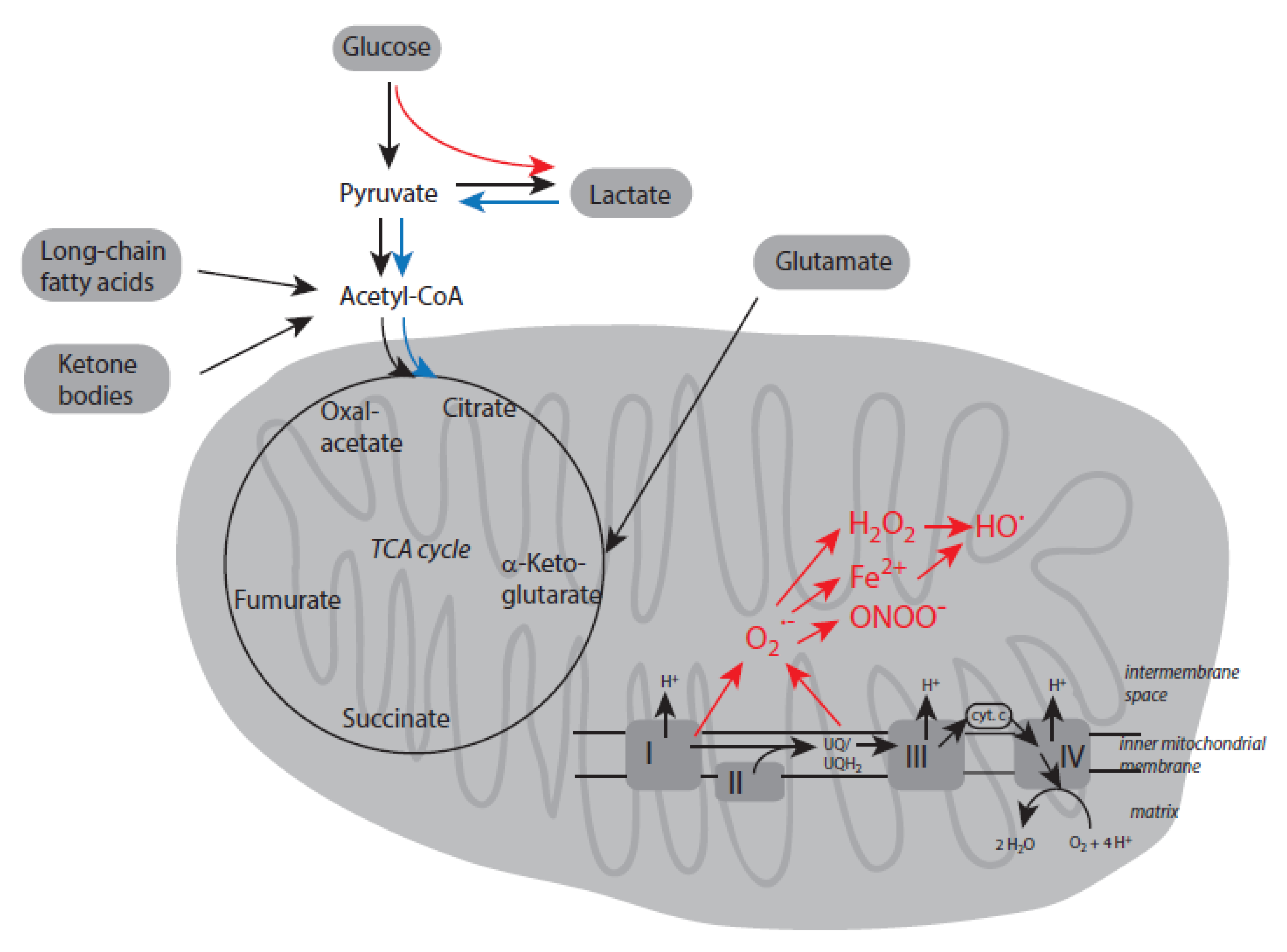

3.1. Energy Metabolism Under Normoxic Conditions

3.2. Deviations in Energy Metabolism in Aged Individuals

3.3. Responses to Hypoxia and Oxidative Stress

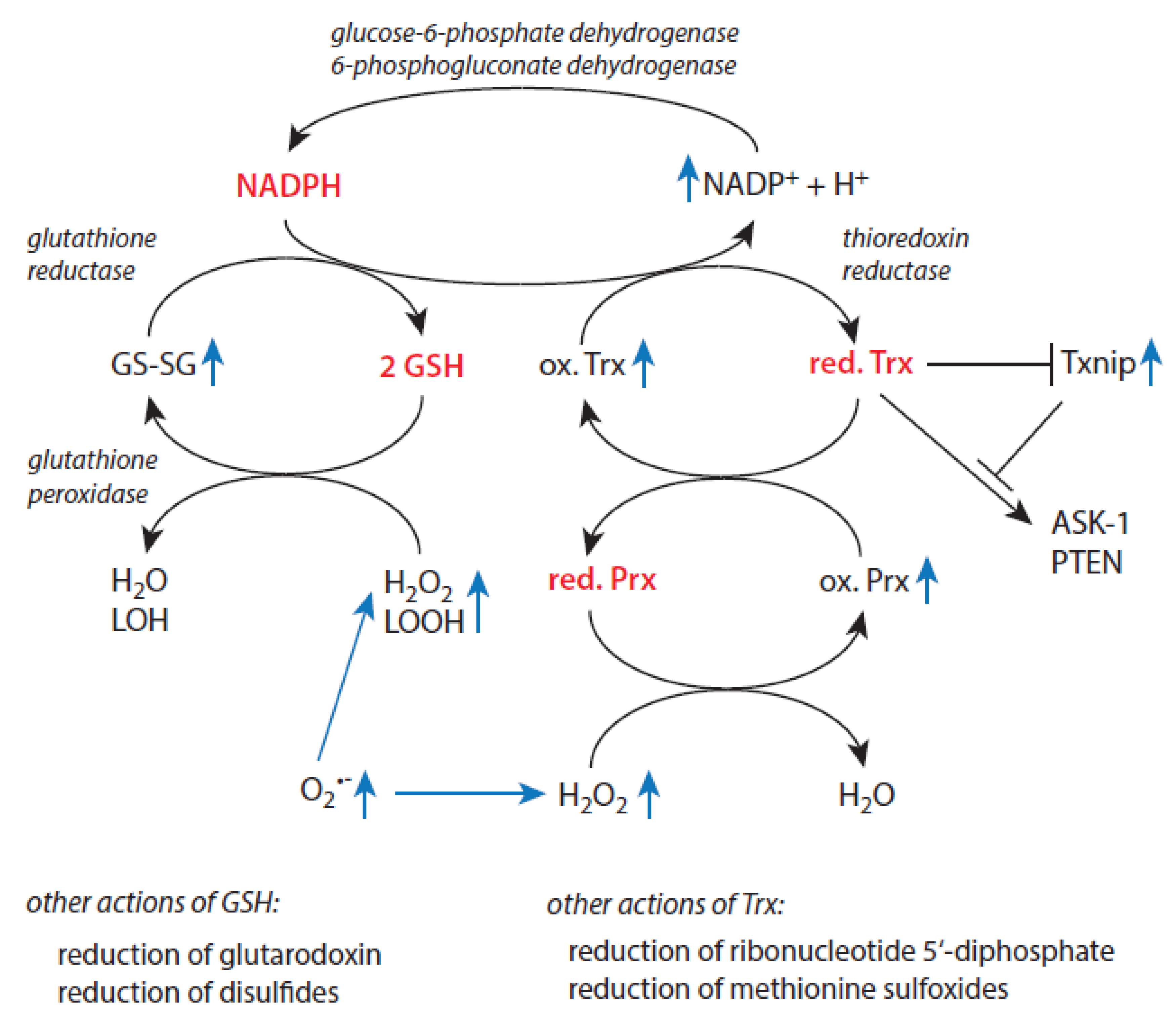

3.4. Redox Regulation and Antioxidative Defense in Aged Individuals

3.5. Activation of Proteolytic Systems in Aged Individuals

3.6. Inflammaging and Necrotic Cell Death

4. Age-Related Alterations in the Protection Against Oxidant-Based Cytotoxic Agents in Selected Disease Scenarios

4.1. Diseases of the Cardiovascular System

4.2. Diabetes Mellitus

4.3. Cancer

4.4. Neuro-Degenerative Diseases

5. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Medvedev, Z.A. An attempt at a rational classification of theories of aging. Biol. Rev. 1990, 375-398. [CrossRef]

- Arnhold, J. Aging in complex multicellular organisms. In Cell and Tissue Destruction. Mechanisms, Protection, Disorders; Academic Press: London, UK; San Diego, CA, USA; Cambridge, MA, USA; Oxford, UK, 2020; pp. 231–247. [CrossRef]

- Arnhold, J. Cells and organisms as open systems. In Cell and Tissue Destruction. Mechanisms, Protection, Disorders; Academic Press: London, UK; San Diego, CA, USA; Cambridge, MA, USA; Oxford, UK, 2020; pp. 3–22. [CrossRef]

- Arnhold, J. Immune response and tissue damage. In Cell and Tissue Destruction. Mechanisms, Protection, Disorders; Academic Press: London, UK; San Diego, CA, USA; Cambridge, MA, USA; Oxford, UK, 2020; pp. 155–204. [CrossRef]

- Arnhold, J. Acute-phase proteins and additional protective systems. In Cell and Tissue Destruction. Mechanisms, Protection, Disorders; Academic Press: London, UK; San Diego, CA, USA; Cambridge, MA, USA; Oxford, UK, 2020; pp. 205–228. [CrossRef]

- Franceschi, C.; Bonafè, M.; Valensin, S.; Olivieri, F.; de Luca, M.; Ottaviani, E.; de Benedictis, G. Inflamm-aging. An evolutionary perspective on immunosenescence. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2000, 244-254. [CrossRef]

- Ferrucci, L.; Fabbri, E. Inflammageing: Chronic inflammation in ageing, cardiovascular disease, and frailty. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2018, 15, 505-522. [CrossRef]

- Arnhold, J. Host-derived cytotoxic agents in chronic inflammation and disease progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3016. [CrossRef]

- Arnhold, J. Inflammation-associated cytotoxic agents in tumorigenesis. Cancers 2024, 16, 81. [CrossRef]

- Franceschi, C. Cell proliferation, cell death and aging. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 1989, 1, 3-15. [CrossRef]

- Kirkwood, T.B.L.; Franceschi, C. Is ageing a complex as it would appear? New perspectives in gerontological research. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1992, 663, 412-417. [CrossRef]

- Franceschi, C.; Capri, M.; Monti, D.; Giunta, S.; Olivieri, F.; Sevini, F.; Panourgia, M.P.; Invidia, L.; Celani, L.; Scurti, M.; Cevenini, E.; Castellani, G.C.; Salvioli, S. Inflammaging and antiinflammaging: A systemic perspective on aging and longevity emerged from studies on humans. Mech. Aging Dev. 2007, 128, 92-105. [CrossRef]

- Baggio, G.; Donazzan, S.; Monti, D. Mari, D.; Martini, S.; Cabelli, C.; Dalla Vestra, M.; Previato, L.; Guido, M.; Pigozzo, S.; Cortella, I.; Grepaldi, G.; Franceschi, C. Lipoprotein(a) and lipoprotein profile in healthy centenarians: A reappraisal of vascular risk factors. FASEB J. 1998, 12, 433-437. [CrossRef]

- Gangemi, S.; Basile, G.; Merendino, R.A.; Minciullo, P.L.; Novick, D.; Rubinstein, M.; Dinarello, C.A.; Lo Balbo, C.; Franceschi, C.; Basili, S.; D’Urbano, E.; Davi, G.; Nicita-Mauro, V.; Romano, M. Increased circulating interleukin-18 levels in centenarians with no signs of vascular disease: Another paradox of longevity. Exp. Gerontol. 2003, 38, 669-672. [CrossRef]

- Mannucchi, P.M.; Mari, D.; Merati, G.; Peyvandi, F.; Tagliabue, L.; Sacchi, E.; Taioli, E.; Sansoni, P.; Bertolini, S.; Franceschi, C. Gene polymorphism predicting high plasma levels of coagulation and fibrinolysis proteins. A study in centenarians. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 1997, 17, 755-759. [CrossRef]

- Coppola, R.; Mari, D.; Lattuada, A.; Franceschi, C. Von Willebrand factor in Italian centenarians. Haematologica 2003, 88, 39-43.

- Franceschi, C.; Campisi, J. Chronic inflammation (inflammaging) and its potential contribution to age-related diseases. J. Gerontol. Biol. Sci. 2014, S4-S9. [CrossRef]

- Troiano, L.; Pini, G.; Petruzzi, E.; Ognibene, A.; Franceschi, C.; Monti, D.; Casotti, G.; Cilotti, A.; Forti, G. Evaluation of adrenal function in aging. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 1999, 22, 74-75.

- Carrieri, G.; Marzi, E.; Olivieri, F.; Marchigiani, F.; Cavallone, L.; Cardelli, M.; Giovanetti, S.; Stecconi, R.; Molendini, C.; Trapassi, C.; De Benedictis, G.; Kletsas, T.; Franceschi, C. The G/C915 polymorphism of transforming growth factor beta1 is associated with human longevity: A study in Italian centenarians. Aging Cell 2004, 3, 443-448. [CrossRef]

- Baylis, D.; Bartlett, D.B.; Patel, H.P.; Roberts, H.C. Understanding how we age: Insights into inflammaging. Longevity Healthspan 2013, 2, 8. [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.B.; Sanders, J.L.; Kizer, J.R.; Boudreau, R.M.; Odden, M.C.; Zeki al Hazzouri, A.; Arnold, A.M. Trajectories of functions and biomarkers with age: The CHS all stars study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 1135-1145. [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, S.; Khanabdali, S.; Kalionis, B.; Wu, J.; Wan, W.; Tai, X. An update of inflamm-aging: Mechanisms, prevention, and treatment. J. Immunol. Res. 2016, 8426874. [CrossRef]

- Dugan, B.; Conway, J.; Duggal, N.A. Inflammaging as a target for healthy ageing. Age Ageing 2023, 52, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, C.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Qian, P.; Huang, H. Inflammation and aging: Signaling pathways and intervention therapies. Signal Transd. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 329. [CrossRef]

- Suresh, R.; Moser, D.M. Pattern recognition in innate immunity, host defense, and immunopathology. Adv. Physiol. Educ. 2013, 37, 284–291. [CrossRef]

- Matzinger, P. Tolerance, danger, and the extended family. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1994, 12, 991–1045. [CrossRef]

- Janeway, C.A.; Medzhitov, R. Innate immune recognition. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2002, 20, 197–216. [CrossRef]

- Scaffidi, P.; Misteli, T.; Bianchi, M.E. Release of chromatin protein HMGB1 by necrotic cells trigger inflammation. Nature 2002, 418, 191-195. [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.M.; Evans, J.E.; Rock, K.L. Molecular identification of a danger signal that alerts the immune system to dying cells. Nature 2003, 425, 516-521. [CrossRef]

- Scheibner, K.A.; Lutz, M.A.; Boodoo, S.; Fenton, M.J.; Powell, J.D.; Horton, M.R. Hyaluronan fragments act as an endogenous danger signal by engaging TLR2. J. Immunol. 2006, 177, 1272-1281. [CrossRef]

- Bours, M.J.; Swennon, E.L.; Di Virgilio, F.; Cronstein, B.N.; Dagnelie, P.C. Adenosine 5’-triphosphate and adenosine as endogenous signaling molecules in immunity and inflammation. Pharmacol. Ther. 2006, 112, 358-404. [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, R.T.; Fernandez, P.L.; Mourao-Sa, D.S.; Porto, B.N.; Dutra, F.F.; Alves, L.S.; Oliviera, M.F.; Graca-Souza, A.V.; Bozza, M.T. Characterization of heme as activator of toll-like receptor 4. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 20221-20229. [CrossRef]

- Farkas, A.M.; Kilgore, T.M.; Lotze, M.T. Detecting DNA: Getting and begetting cancer. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs 2007, 8, 981-986.

- Pepys, M.B.; Baltz, M.I. Acute phase proteins with special reference to C-reactive protein and related proteins (pentraxins) and serum amyloid A protein. Adv. Immunol. 1983, 34, 141–212. [CrossRef]

- Vandivier, R.W.; Henson, P.M.; Douglas, I.S. Burying the death: The impact of failed apoptotic cell removal (efferocytosis) on chronic inflammatory lung disease. Chest 2006, 129, 1673–1682. [CrossRef]

- Pober, J.S.; Sessa, W.C. Inflammation and the blood microvascular system. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol. 2015, 7, 016345. [CrossRef]

- Young, B.; Gleeson, M.; Cripps, A.W. C-reactive protein. A critical review. Pathology 1991, 23, 118-124. [CrossRef]

- Gewurz, H.; Mold, C.; Siegel, J.; Fiedel, B. C-reactive protein and acute phase response. Adv. Intern. Med. 1982, 27, 345-372.

- Kopf, H.; de la Rosa, G.M.; Horward, O.M.; Chen, X. Rapamycin inhibits differentiation of Th17 cells and promotes generation of FoxP3+ T regulatory cells. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2007, 7, 1819-1824. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Prados, J.C.; Través, P.C.; Cuenca, J.; Rico, D.; Aragonés, J.; Martin-Sanz, P.; Casante, M.; Boscá, L. Substrate fate in activated macrophages; a comparison between innate, classic, and alternative activation. J. Immunol. 2010, 185, 605-614. [CrossRef]

- Krawczyk, C.M.; Holowka, T.; Sun, J.; Blaigh, J.; Amiel, E.; DeBerardinis, R.J.; Cross, J.R.; Jung, E.; Thompson, C.B.; Jones, R.G.; Pearce, E.J. Toll-like receptor-induced changes in glycolytic metabolism regulate dendritic cell activation. Blood 2010, 115, 4742-4749. [CrossRef]

- Morrison, T.; Watts, E.R.; Sadiku, P.; Walmsley, S.R. The emerging role for metabolism in fueling neutrophilic inflammation. Immunol. Rev. 2023, 314, 427-441. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.O.; Wan, Y.Y.; Sanjabi, S.; Robertson, A.K.; Flavell, R.A. Transforming growth factor-beta regulation of immune response. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2006, 24, 99–146. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.O.; Flavell, R.A. Contextual regulation of inflammation: A duet of transforming growth factor-beta and interleukin-10. Immunity 2008, 28, 468–476. [CrossRef]

- Couper, K.N.; Blount, D.G.; Riley, E.M. IL-10: The master regulator of immunity to infection. J. Immunol. 2008, 180, 5771–5777. [CrossRef]

- Landén, N.X.; Li, D.; Ståhle, M. Transition from inflammation to proliferation: A critical step during wound healing. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2016, 73, 3861–3885. [CrossRef]

- Marega, M.; Chen, C.; Bellusci, S. Cross-talk between inflammation and fibroblast growth factor 10 during organogenesis and pathogenesis: Lessons learnt from the lung and other organs. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 656883. [CrossRef]

- Serhan, C.N.; Savill, J. Resolution of inflammation: The beginning programs the end. Nat. Immunol. 2005, 6, 1191–1197. [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekharan, J.A.; Sharma-Walia, N. Lipoxins: nature’s way to resolve inflammation. J. Inflamm. Res. 2015, 8, 181–192. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Pino, M.D.; Dean, M.J.; Ochoa, A.C. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC): When good intentions go awry. Cell Immunol. 2021, 362, 104302. [CrossRef]

- Veglia, F.; Sanseviero, E.; Gabrilovich, D.I. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the era of increasing myeloid cell diversity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 21, 485–498. [CrossRef]

- Murray, P.J.; Wynn, T.A. Protective and pathogenic functions of macrophage subsets. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 723–737. [CrossRef]

- Martinez, F.O.; Gordon, S.; Locati, M.; Montavani, A. Transcriptional profiling of the human monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation and polarization: New molecules and patterns of gene expression. J. Immunol. 2006, 177, 7303–7311. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, K.; Hoffmann, P.; Voelkl, S.; Meidenbauer, N.; Ammer, J.; Edinger, M.; Gottfried, E.; Schwarz, S.; Rothe, G.; Hoves, S.; et al. Inhibitory effect of tumor cell-derived lactic acid on human T cells. Blood 2007, 109, 3812–3819. [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Gyamfi, J.; Jang, H.; Koo, J.S. The role of tumor-associated macrophage in breast cancer biology. Histol. Histopathol. 2018, 33, 133–145. [CrossRef]

- Mu, X.; Shi, W.; Xu, Y.; Xu, C.; Zhao, T.; Geng, B.; Yang, J.; Pan, J.; Hu, S.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, J.; Wang, C.; Shen, J.; Che, Y.; Liu, Z.; Lv; Y.; Wen, H.; You, Q. Tumor-derived lactate induces M2 macrophage polarization via the activation of the ERK/STAT3 signaling pathway in breast cancer. Cell Cycle 2018, 17, 428-438. [CrossRef]

- Ratter, J.M.; Rooljackers, H.M.M.; Hoolveld, G.J.; Hijmans, A.G.M.; de Galan, B.E.; Tack, C.J.; Stienstra, R. In vitro and in vivo effects of lactate on metabolism and cytokine production of human primary PBMCs and monocytes. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2564. [CrossRef]

- McCord, J.; Fridovich, I. Superoxide dismutase: An enzymic function for erythrocuprein (hemocuprein). J. Biol. Chem. 1960, 224, 6049–6055.

- Chang, L.Y.; Slot, J.W.; Geuze, H.J.; Crapo, J.D. Molecular immunocytochemistry of the CuZn superoxide dismutase in rat hepatocytes. J. Cell Biol. 1988, 107, 2169–2179. [CrossRef]

- Weisiger, R.A.; Fridovich, I. Mitochondrial superoxide dismutase. Site of synthesis and intramolecular localization. J. Biol. Chem. 1973, 248, 4793–4796.

- Antonyuk, S.V.; Strange, R.W.; Marklund, S.L.; Hasnain, S.S. The structure of human extracellular copper-zinc superoxide dismutase at 1.7 Å resolution: Insights into heparin and collagen binding. J. Mol. Biol. 2009, 388, 310–326. [CrossRef]

- Ursini, F.; Maiorino, M.; Roveri, A. Phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase (PHGPx): More than an antioxidant enzyme? Biomed. Environm. Sci. 1997, 10, 327–332.

- Low, F.M.; Hampton, M.P.; Winterbourn, C.C. Prx2 and peroxide metabolism in the erythrocyte. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2008, 10, 1621–1630. [CrossRef]

- Goyal, M.M.; Basak, A. Human catalase: Looking for complete identity. Protect. Cell 2010, 1, 888–897. [CrossRef]

- Gutteridge, J.M.C. Ferrous-salt-promoted damage to deoxyribose and benzoate. The increased effectiveness of hydroxyl-radical scavengers in the presence of EDTA. Biochem. J. 1987, 18, 37-49. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Zhang, A.-S.; Enns, C.A. Iron regulation by hepcidin. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 123, 2337–2343. [CrossRef]

- Gkouvatsos, K.; Papanikolaou, G.; Pantopoulos, K. Regulation of iron transport and the role of transferrin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2011, 1820, 188–202. [CrossRef]

- Gamella, E.; Buratti, P.; Cairo, G.; Recalcati, S. The transferrin receptor: The cellular iron gate. Metallomics 2017, 9, 1367–1375. [CrossRef]

- Massover, W.H. Ultrastructure of ferritin and apoferritin: A review. Micron 1993, 24, 389–437. [CrossRef]

- Prohaska, J.R. Role of copper transporters in copper homeostasis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 88, 826S–829S. [CrossRef]

- Sokolov, A.V.; Ageeva, K.V.; Pulina, M.O.; Cherkalina, O.S.; Samygina, V.R.; Vlasova, I.I.; Panasenko, O.M.; Zakharova, E.T.; Vasilyev, V.B. Ceruloplasmin and myeloperoxidase in complex affect the enzymatic properties of each other. Free Radic. Res. 2008, 42, 989–998. [CrossRef]

- Chapman, A.L.P.; Mocatta, T.J.; Shiva, S.; Seidel, A.; Chen, B.; Khalilova, I.; Paumann-Page, M.E.; Jameson, G.N.L.; Winterbourn, C.C.; Kettle, A.J. Ceruloplasmin is an endogenous inhibitor of myeloperoxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 6464–6477. [CrossRef]

- Samygina, V.R.; Sokolov, A.V.; Bourenkov, G.; Petoukhov, M.V.; Pulina, M.O.; Zakharova, E.T.; Vasilyev, V.B.; Bartunik, H.; Svergun, D.I. Ceruloplasmin: Macromolecular assemblies with iron-containing acute phase proteins. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e67145. [CrossRef]

- Sokolov, A.V.; Kostevich, V.A.; Zakharova, E.T.; Samygina, V.R.; Panasenko, O.M.; Vasilyev, V.B. Interaction of ceruloplasmin with eosinophil peroxidase as compared to its interplay with myeloperoxidase: Reciprocal effect on enzymatic properties. Free Radic. Res. 2015, 49, 800–811. [CrossRef]

- Ashby, M.T.; Carlson, A.C.; Scott, M.J. Redox buffering of hypochlorous acid by thiocyanate in physiologic fluids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 15976–15977. [CrossRef]

- Nagy, P.; Beal, J.L.; Ashby, M.T. Thiocyanate is an efficient endogenous scavenger of the phagocytic killing agent hypobromous acid. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2006, 19, 587–593. [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.J.; Hawkins, C.L. The role of myeloperoxidase in biomolecule modification, chronic inflammation, and disease. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2020, 32, 957–981. [CrossRef]

- Love, D.T.; Barrett, D.J.; White, M.Y.; Cordwell, S.J.; Davies, M.J.; Hawkins, C.L. Cellular targets of the myeloperoxidase-derived oxidant hypothiocyanous acid (HOSCN) and its role in the inhibition of glycolysis in macrophages. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2016, 94, 88–98. [CrossRef]

- Frommherz, K.J.; Faller, B.; Bieth, J.G. Heparin strongly decreases the rate of inhibition of neutrophil elastase by α1-proteinase inhibitor. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 15356–15362. [CrossRef]

- Ermolieff, J.; Boudier, C.; Laine, A.; Meyer, B.; Bieth, J.G. Heparin protects cathepsin G against inhibition by protein proteinase inhibitors. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 29502–29508. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.C.; Ohlsson, K. Isolation, properties, and complete amino acid sequence of human secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor, a potent inhibitor of leukocyte elastase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1986, 83, 6692–6696. [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.E.; Brown, T.I.; Roghanian, A.; Sallenave, J.M. SLPI and elafin: One glove, many fingers. Clin. Sci. 2006, 110, 21–35. [CrossRef]

- Verrier, T.; Solhonne, B.; Sallenave, J.M.; Garcia-Verdugo, I. The WAP protein Trappin-2/Elafin: A handyman in the regulation of inflammatory and immune responses. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2012, 44, 1377–1380. [CrossRef]

- Duranton, J.; Adam, C.; Blieth, J.G. Kinetic mechanism of the inhibition of cathepsin G by α1-antichymotrypsin and α1-proteinase inhibitor. Biochemistry 1997, 37, 11239–11245. [CrossRef]

- Travis, J.; Bowen, J.; Baugh, R. Human α1-antichymotrypsin: Interaction with chymotrypsin-like proteinases. Biochemistry 1978, 26, 5651–5656. [CrossRef]

- Kalsheker, N.A. α1-Antichymotrypsin. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1996, 28, 961–964. [CrossRef]

- Gordon, J.L. Extracellular ATP: Effects, sources and fate. Biochem. J. 1986, 233, 309-319. [CrossRef]

- Khakh, B.S.; Burnstock, G. The double life of ATP. Sci. Am. 2009, 301, 84-90. [CrossRef]

- Dou, L.; Chen, Y.F.; Cowan, P.J.; Chen, X.-P. Extracellular ATP signaling and clinical relevance. Clin. Immunol. 2018, 188, 67-73. [CrossRef]

- Flood, D.; Lee, E.S.; Taylor, C.T. Intracellular energy production and distribution in hypoxia. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299, 105103. [CrossRef]

- El Bacha, T.; Luz, M.R.M.P.; Da Poian, A.T. Dynamic adaptation of nutrient utilization in humans. Nat. Educ. 2010, 3, 8.

- Chandel, N.S. Amino acid metabolism. Cold Spring Harbor Persp. Biol. 2021, 13, a040584. [CrossRef]

- Delgoffe, G.M.; Polizzi, K.N.; Waickman, A.T.; Heikamp, E.; Meyers, D.J.; Horton, M.R.; Xiao. B.; Worley, P.F.; Powell, J.D. The kinase mTOR regulates the differentiation of helper T cells through the selective activation of signaling by mTORC1 and mTORC2. Nat. Immunol. 2011, 12, 295-303. [CrossRef]

- Buck, M.D.; O’Sullivan, D.; Pearce, E.L. T cell mechanism drives immunity. J. Exp. Med. 2015, 212, 1345-1360. [CrossRef]

- Schiaffino, S.; Reggiani, C. Fiber types in mammalian skeletal muscles. Physiol. Rev. 2011, 91,1447-1531. [CrossRef]

- Ørtenblad, N.; Westerblad, H.; Nielsen, J. Muscle glycogen stores and fatigue. J. Physiol. 2013, 591, 4405-4413. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, T.E.; Richter, E.A. regulation of glucose and glycogen metabolism during and after exercise. J. Physiol. 2012, 590, 1069-1076. [CrossRef]

- Laffel, L. Ketone bodies: A review of physiology, pathophysiology and application of monitoring to diabetes. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 1999, 15, 412-416.

- Holeček, M. Origin and roles of alanine and glutamine in gluconeogenesis in the liver, kidneys, and small intestine under physiological and pathological conditions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7037. [CrossRef]

- Bratic, I.; Trifunovic, A. Mitochondrial energy metabolism and aging. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010, 1707, 961-967. [CrossRef]

- Santanasto, A.J.; Glynn, N.W.; Jubrias, S.A.; Conley, K.E.; Boudreau, R.M.; Amati, F.; Mackey, D.C.; Simonsick, E.M.; Strotmeyer, E.S.; Coen, P.M.; Goodpaster, B.H., Newman, A.B. Skeletal muscle mitochondrial function and fatigability in older adults. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2015, 70, 1379-1385. [CrossRef]

- Lima, T.; Li, T.Y.; Mottis, A.; Auwerx. Pleiotropic effects of mitochondria on aging. Nat. Aging 2022, 2, 199-213. [CrossRef]

- Miquel, J.; Economos, A.C.; Fleming, J.; Johnson, J.E. Jr. Mitochondrial role in cell aging. Exp. Gerontol. 1980, 15, 575-591. [CrossRef]

- Chistiakov, D.A.; Sobenin, I.A.; Revin, V.V.; Orekhov, A.N.; Bobryshev, Y.V. Mitochondrial aging and age-related dysfunction of mitochondria. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 238463. [CrossRef]

- Crane, J.D.; Devries, M.C.; Safdar, A.; Hamadeh, M.J.; Tarnopolsky, M.A. The effect of aging on human skeletal muscle mitochondrial and intramyocellular lipid ultrastructure. J. Gerontol. A 2010, 65, 119-128. [CrossRef]

- Marzetti, E.; Leeuwenburgh, C. Skeletal muscle apoptosis, sarcopenia and frailty at old age. Exp. Gerontol. 2006, 41, 1234-1238. [CrossRef]

- Mouchiroud, L.; Houtkooper, R.H.; Moullan, N.; Katsyuba, E.; Ryu, D.; Cantó, C.; Mottis, A.; Jo, Y.-S.; Viswanathan, M.; Schoonjans, K.; Guarente, L.; Auwerx, J. The NAD+/sirtuin pathway modulates longevity through activation of mitochondrial UPR and FOXO signaling. Cell 2013, 154, 430–441. [CrossRef]

- Gomes, A.P.; Price, N.L.; Ling, A.J.Y.; Moslehi, J.J.; Montgomery, M.K.; Rajman, L.; White, J.P.; T eodoro, J.S.; Wrann, C.D.; Hubbard, B.P.; Mercken, E.M.; Palmeira, C.M.; de Cabo, R.; Rolo, A.P.; Turner, N.; Bell, E.L.; Sinclair, D.A. Declining NAD+ induces a pseudohypoxic state disrupting nuclear-mitochondrial communication during aging. Cell 2013, 155, 1624–1638. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, A.P.; Pierzynowski, S.G. Biological effects of 2-oxoglutarate with particular emphasis on the regulation of protein, mineral and lipid absorption/metabolism, muscle performance, kidney function, bone formation and cancerogenesis, all viewed from a healthy ageing perspective state of the art–review article. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2008, 59, Suppl. 1, 91–106.

- Tian, Q.; Zhao, J.; Yang, Q.; Wang, B.; Deavila, J.M.; Zhu, M.-J.; Du, M. Dietary α-ketoglutarate promotes beige adipogenesis and prevents obesity in middle-aged mice. Aging Cell 2020, 19, e13059. [CrossRef]

- Houtkooper, R.H.; Pirinen, E.; Auwerx, J. Sirtuins as regulators of metabolism and healthspan. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 225–238. [CrossRef]

- Katsyuba, E.; Romani, M.; Hofer, D.; Auwerx, J. NAD+ homeostasis in health and disease. Nat. Metab. 2020, 2, 9–31. [CrossRef]

- Rajman, L.; Chwalek, K.; Sinclair, D.A. Therapeutic potential of NAD-boosting molecules: The in vivo evidence. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 529–547. [CrossRef]

- Imai, S.-I.; Guarente, L. It takes two to tango: NAD+ and sirtuins in aging/longevity control. npj Aging Mech. Dis. 2016, 2, 16017. [CrossRef]

- Fasolino, M.; Liu, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Z. Distinct cellular and molecular environments support aging-related DNA methylation changes in the substantia nigra. Epigenomics 2017, 9, 21–31. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Deng, P.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zheng, X.; Zhou, L.; Liu, W.; Li, Q.; Lin, W.; Qi, X.; Ou, G.; Wang, C.; Yuan, Q. Alpha-ketoglutarate ameliorates age-related osteoporosis via regulating histone methylations. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5596. [CrossRef]

- Borkum, J.M. The tricarboxylic acid cycle as a central regulator of the rate of aging: Implications for metabolic interventions. Adv. Biol. 2023, 7, 2300095. [CrossRef]

- Gardner, P.R. Superoxide-driven aconitase Fe-S cycling. Biosci. Rep. 1997, 17, 33–42. [CrossRef]

- Gardner, P.R. Aconitase: Sensitive target and measure of superoxide. Meth. Enzymol. 2002, 349, 9–23. [CrossRef]

- Harmer, A.R.; Chisholm, D.J.; McKenna, M.J.; Hunter, S.K.; Ruell, P.A.; Naylor, J.M.; Maxwell, L.J.; Flack, J.R. Sprint training increases muscle oxidative metabolism during high-intensity exercise in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2008, 31, 2097–2102. [CrossRef]

- Levy, B.; Gibot, S.; Franck, P.; Cravoisy, A.; Bollaert, P.-E. Relation between muscle Na+K+ATPase activity and raised lactate concentrations in septic shock: A prospective study. Lancet 2005, 365, 871–875. [CrossRef]

- Nalbandian, M.; Radak, Z.; Takeda, M. Lactate metabolism and satellite cell fate. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 610983. [CrossRef]

- Schafer, F.Q.; Buettner, G.R. Redox environment of the cell as viewed through the redox state of the glutathione disulfide/glutathione couple. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2001, 30, 1191-1212. [CrossRef]

- Bergman, B.C.; Horning, M.A.; Casazza, G.A.; Wolfel, E.E.; Butterfield, G.E.; Brooks, G.A. Endurance training increases gluconeogenesis during rest and exercise in men. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2000, 278, E244–E251. [CrossRef]

- Bergman, B.C.; Tsvetkova, T.; Lowes, B.; Wolfel, E.E. Myocardial glucose and lactate metabolism during rest and atrial pacing in humans. J. Physiol. 2009, 587, 2087–2099. [CrossRef]

- Glenn, T.C.; Martin, N.A.; Horning, M.A.; McArthur, D.L.; Hovda, D.A.; Vespa, P.; Brooks, G.A. Lactate: Brain fuel in human traumatic brain injury: A comparison with normal healthy control subjects. J. Neurotrauma 2015, 32, 820–832. [CrossRef]

- Suhara, T.; Hishiki, T.; Kasahara, M.; Hayakawa, N.; Oyaizu, T.; Nakanishi, T.; Kubo, A.; Morisaki, H.; Kaelin, W.G. Jr.; Suematsu, M.; Minamishima, Y.A. Inhibition of the oxygen sensor PHD2 in the liver improves survival in lactic acidosis by activating the Cori cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 11642-11647. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Lin, X.; Fu, X.; An, Y.; Zou, Y.; Wang, J.-X.; Wang, Z.; Yu, T. Lactate metabolism in human health and disease. Sign. Transd. Targ. Ther. 2022, 7, 305. [CrossRef]

- Bartolini, B.; Mannelli, M.; Gamberi, T.; Fiaschi, T. The multiple roles of lactate in the skeletal muscle. Cells 2024, 13, 1177. [CrossRef]

- Colegio, O.R.; Shu, N.Q.; Shabo, A.I.; Chu, T.; Rhebergen, A.M.; Jairam, V.; Cyrus, N.; Brokowski, C.E.; Eisenbarth, S.E.; Philipps, G.M.; Cline, G.W.; Philipps, A.J.; Medzhitov, R. Functional polarization of tumour-associated macrophages by tumour-derived lactic acid. Nature 2014, 513, 559-563. [CrossRef]

- Goetze, K.; Walenta, S.; Ksiazkiewicz, M.; Kunz-Schughart, L.A.; Mueller-Klieser, W. Lactate enhances motility of tumor cells and inhibits monocyte migration and cytokine release. Int. J. Oncol. 2011, 39, 453-463. [CrossRef]

- Ragni, M.; Fornelli, C.; Nisoli, E.; Penna, F. Amino acids in cancer and cachexia: An integrated view. Cancers 2022, 14, 5691. [CrossRef]

- Stalnecker, C.A.; Cluntun, A.A.; Cerione, R.A. Balancing redox stress: Anchorage-independent growth requires reductive carboxylation. Transl. Cancer Res. 2016, 5, S433-S437. [CrossRef]

- Yeo, E.-J. Hypoxia and aging. Exp. Mol. Med. 2019, 51, 67. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.T.; Scholz, C.C. The effect of HIF on metabolism and immunity. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2022, 18, 573-587. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Giunta, S.; Xia, S. Hypoxia in aging and aging-related diseases: Mechanism and therapeutic strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8165. [CrossRef]

- Kozlov, A.M.; Lone, A.; Betts, D.H.; Cumming, R.C. Lactate preconditioning promotes a HIF-1α-mediated metabolic shift from OXPHOS to glycolysis in normal human diploid fibroblasts. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8388. [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, K.; Fukuda, A.; Hisatake, K. Mechanisms of the metabolic shift during somatic cell reprogramming. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2254. [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, F.; Hamanaka, R.; Wheaton, W.W.; Weinberg, S.; Joseph, J.; Lopez, M.; Kalyanaraman, B.; Mutlu, G.M.; Budinger, G.R.S.; Chandel, N.S. Mitochondrial metabolism and ROS generation are essential for Kras-mediated tumorigenicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 8788–8793. [CrossRef]

- Davis, L.; Recktenwald, M.; Hutt, E.; Fuller, S.; Briggs, M.; Goel, A.; Daringer, N. Targeting HIF-2α in the tumor microenvironment: Redefining the role of HIF-2α for solid cancer therapy. Cancers 2022, 14, 1259. [CrossRef]

- Löfstedt, T.; Fredlund, E.; Holmquist-Mengelbier, L.; Pietras, A.; Overnberger, M.; Pollinger, L.; Påhlman, S. Hypoxia inducible factor-2α in cancer. Cell Cycle 2007, 6, 919–926. [CrossRef]

- de Saedeleer, C.J.; Copetti, T.; Porporato, P.E.; Verrax, J.; Feron, O.; Sonveaux, P. Lactate activates HIF-1 in oxidative but not in Warburg-phenotype human tumor cells. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e46571. [CrossRef]

- Pires, B.R.B.; Mencalha, A.L.; Ferreira, G.M.; Panis, C.; Silva, R.C.M.C.; Abdelhay, E. The hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha signaling pathway and its relation to cancer and immunology. Am. J. Immunol. 2014, 10, 215-224. [CrossRef]

- Ivan, M.; Haberberger, T.; Gervasi, D.C.; Michelson, K.S.; Günzler, V.; Kondo, K.; Yang, H.; Sorokina, I.; Conawey, R.C.; Conawey, J.W.; Kaelin W.G. Jr. Biochemical purification and pharmacological inhibition of a mammalian prolyl hydroxylase acting on hypoxia-inducible factor. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 13459-13464. [CrossRef]

- Lennicke, C.; Rahn, J.; Lichtenfels, R.; Wessjohann, L.A.; Seliger, B. Hydrogen peroxide—Production, fate and role in redox signaling of tumor cells. Cell Commun. Signal. 2015, 13, 39. [CrossRef]

- Cyran, A.M.; Zhitkovich, A. HIF1, HSF1, and NRF2: Oxidant-responsive trio raising cellular defenses and engaging immune system. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2022, 35, 1690–1700. [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo, M.C.; Zhang, D.D. The emerging role of the Nrf2-Keap1 signaling pathway in cancer. Genes Dev. 2013, 27, 2179–2191. [CrossRef]

- Song, M.-Y.; Lee, D.-Y.; Chun, K.-S.; Kim, E.-H. The role of Nrf2/keap1 signaling pathway in cancer metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4376. [CrossRef]

- Meister, A. Glutathione metabolism and its selective modification. J. Biol. Chem. 1988, 263, 17205-17208. [CrossRef]

- Mustacich, D.; Powis, G. Thioredoxin reductase. Biochem. J. 2000, 346, 1-8.

- Holmgren, A.; Johansson, C.; Berndt, C.; Lönn, M.E.; Hudemann, C.; Lillig, C.H. Thiol redox control via thioredoxin and glutaredoxin systems. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2005, 33, 1375-1377. [CrossRef]

- Riganti, C.; Gazzano, E.; Polimeni, M.; Aldieri, E.; Ghigo, D. The pentose phosphate pathway: An antioxidant defense and a crossroad in tumor cell fate. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012, 53, 421-436. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xing, X.; Zhang, P.; Chen, L.; Pei, H. Homeostatic regulation of NAD(H) and NADP(H) in cells. Genes Dis. 2024, 11, 101146. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ryu, D.; Wu, Y.; Gariani, K.; Wang, X.; Luan, P.; D’Amigo, D.; Ropelle, E.R.; Lutolf, M.P.; Aebersold, R.; Schoonjans, K.; Menzies, K.J.; Auwerx, J. NAD+ repletion improves mitochondrial and stem cell function and enhances life span in mice. Science 2016, 352, 1436–1443. [CrossRef]

- Bai, P.; Cantó, C.; Oudart, H.; Brunyánszki, A.; Cen, Y.; Thomas, C.; Yamamoto, H.; Huber, A.; Kiss, B.; Houtkooper, R.H.; Schoonjans, K.; Schreiber, V.; Sauve, A.A.; Menissier-de Murcia, J.; Auwerx, J. PARP-1 inhibition increases mitochondrial metabolism through SIRT1 activation. Cell Metab. 2011, 13, 461–468. [CrossRef]

- Pirinen, E.; Cantó, C.; Jo, Y.S.; Morato, L.; Zhang, H.; Menzies, K.J.; Williams, E.G.; Mouchiraud, L.; Moullan, N.; Hagberg, C.; Li, W.; Timmers, S.; Imhof, R.; Verbeek, J.; Pujol, A.; van Loon, B.; Viscomi, C.; Zeviani, M.; Schrauwen, P.; Sauve, A.A.; Auwerx, J. Pharmacological Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases improves fitness and mitochondrial function in skeletal muscle. Cell Metab. 2014, 19, 1034–1041. [CrossRef]

- Yoshino, J.; Mills, K.F.; Yoon, M.J.; Imai, S. Nicotinamide mononucleotide, a key NAD+ intermediate, treats the pathophysiology of diet- and age-induced diabetes in mice. Cell Metab. 2011, 14, 528–536. [CrossRef]

- Cantó, C.; Houtkooper, R.H.; Pirinen, E.; Youn, D.Y.; Oosterveer, M.H.; Cen, Y.; Fernandez-Marcos, P.J.; Yamamoto, H.; Andreux, P.A.; Cettour-Rose, P.; Gademann, K.; Rinsch, C.; Schoonjans, K.; Sauve, A.A.; Auwerx, J. The NAD+ precursor nicotinamide riboside enhances oxidative metabolism and protects against high-fat diet-induced obesity. Cell Metab. 2012, 15, 838–847. [CrossRef]

- Arnhold, J. Oxidation and reduction of biological material. In Cell and Tissue Destruction. Mechanisms, Protection, Disorders; Academic Press: London, UK; San Diego, CA, USA; Cambridge, MA, USA; Oxford, UK, 2020; pp. 55–97. [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Del Cerro, E.; de Toda, I.M.; Félix, J.; Baca, A.; De la Fuente, M. Components of the glutathione cycle as markers of biological age: An approach to clinical application in aging. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1529. [CrossRef]

- Lang, C.A.; Naryshkin, S.; Schneider, D.L.; Mills, B.J.; Lindemann, R.D. Low blood glutathione levels in healthy aging adults. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1992, 120, 720-725.

- Loguercio, C.; Taranto, D.; Vitale, L.M.; Beneduce, F.; Del Vecchio Blanco, C. Effect of liver cirrhosis and age on the glutathione concentration in the plasma, erythrocytes, and gastric mucosa of man. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1996, 20, 483-488. [CrossRef]

- de Toda, M.; Vida, C.; Garrido, A.; De la Fuente, M. Redox parameters as markers of the rate of aging and predictors of life span. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2020, 75, 613-620. [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, S.E.; Guo, H.; Fedarko, N.; DeZern, A.; Fried, L.P.; Xue, Q.-L.; Leng, S.; Beamer, B.; Walston, J.D. Glutathione peroxidase enzyme activity in aging. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2008, 63, 505-509. [CrossRef]

- Belrose, J.C.; Xie, Y.F.; Gierszewski, L.J.; MacDonald, J.F.; Jackson, M.F. Loss of glutathione homeostasis associated with neuronal senescence facilitates TRPM2 channel activation in cultured hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Mol. Brain 2012, 5, 11. [CrossRef]

- Iskusnykh, I.Y.; Zakharova, A.A.; Pathak, D. Glutathione in brain disorders and aging. Molecules 2022, 27, 324. [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Lin, Y.; Huang, Y.; Shen, Y.-Q.; Chen, Q. Thioredoxin (Trx): A redox target and modulator of cellular senescence and aging-related diseases. Redox Biol. 2024, 70, 103032. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, S.M.; Lee, R.T. Thioredoxin and thioredoxin target proteins: From molecular mechanisms to functional significance. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013, 18, 1165-1207. [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.; Zhang, F.; Qu, K.; Liu, C.; Zhang, J. TXNIP: A double-edged sword in disease and therapeutic outlook. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longevity 2022, 7805115. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Suh, H.-W.; Jeon, Y.H.; Hwang, E.; Nguyen, L.T.; Yeom, J.; Lee, S.-G.; Lee, C.; Kim, K.J.; Kang, B.S.; Jeong, J.-O.; Oh, T.-K.; Choi, I.; Lee, J.-O.; Kim, M.H. The structural basis for the negative regulation of thioredoxin by thioredoxin-interacting protein. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 2958. [CrossRef]

- Ismael, S.; Nasochi, S.; Li, L.; Aslam, K.S.; Khan, M.M.; El-Remessy, A.B.; McDonald, M.P.; Liao, F.-F.; Ishrat, T. Thioredoxin interacting protein regulates age-associated neuroinflammation. Neurobiol. Dis. 2021, 156, 105399. [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.-H.; Park, S.-J. TXNIP: A key protein in the cellular stress response pathway and a potential therapeutic target. Exp. Mol. Med. 2023, 55, 1348-1356. [CrossRef]

- Alhawiti, N.M.; Al Mahri, S.; Aziz, M.A.; Malik, S.S.; Mohammad, S. TXNIP in metabolic regulation: Physiological role and therapeutic outlook. Curr. Drug Targets 2017, 18, 1095–1103. [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Zheng, B.; Shaywitz, A.; Dagon, Y.; Tower, C.; Bellinger, G.; Shen, C.H.; Wen, J.; Asara, J.; McGraw, T.E.; Kahn, B.B.; Cantley, L.C. AMPK-dependent degradation of TXNIP upon energy stress leads to enhanced glucose uptake via GLUT1. Mol. Cell 2013, 49, 1167–1175. [CrossRef]

- Waldhart, A.N.; Dykstra, H.; Peck, A.S.; Boguslawski, E.A.; Madaj, Z.B.; Wen, J.; Veldkamp, K.; Hollowell, M.; Zheng, B.; Cantley, L.C.; McGraw, T.E.; Wu, N. Phosphorylation of TXNIP by AKT mediates acute influx of glucose in response to insulin. Cell. Rep. 2017, 19, 2005–2013. [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.S.; DeLuca, H.F. Isolation and characterization of a novel cDNA from HL-60 cells treated with 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D-3. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1994, 1219, 26–32. [CrossRef]

- Oberacker, T.; Bajorat, J.; Ziola, S.; Schroeder, A.; Röth, D.; Kastl, L.; Edgar, B.A.; Wagner, W.; Gülow, K.; Krammer, P.H. Enhanced expression of thioredoxin-interacting-protein regulates oxidative DNA damage and aging. FEBS Lett. 2018, 592, 2297-2307. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Tardivel, A.; Thorens, B.; Choi, I.; Tschopp, J. Thioredoxin-interacting protein links oxidative stress to inflammasome activation. Nat. Immunol. 2010, 11, 136–140. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Saxena, G; Mungrue, I.N.; Lusis, A.J.; Shalev, A. Thioredoxin-interacting protein: A critical link between glucose toxicity and beta-cell apoptosis. Diabetes 2008, 57, 938–944. [CrossRef]

- Gokulakrishnan, K.; Mohanavalli, K.T.; Monickaraj, F.; Mohan, V.; Balasubramanyam, M. Subclinical inflammation/oxidation as revealed by altered gene expression profiles in subjects with impaired glucose tolerance and Type 2 diabetes patients. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2009, 324, 173–181. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Ismael, S.; Nasoohi, S.; Sakata, K.; Liao, F.-F.; McDonald, M.P.; Ishrat, T. Thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP) associated NLRP3 inflammasome activation in human Alzheimer’s disease Brain. J. Alzheimers. Dis. 2019, 68, 255–265. [CrossRef]

- Su, C.-J.; Feng, Y.; Liu, T.-T.; Liu, X.; Bao, J.-J.; Shi, A.-M.; Hu, D.-M.; Liu, T.; Yu, Y.-L. Thioredoxin-interacting protein induced alpha-synuclein accumulation via inhibition of autophagic flux: Implications for Parkinson’s disease. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2017, 23, 717–723. [CrossRef]

- Ismael, S.; Wajidunnisa; Sakata, K.; McDonald, M.P.; Liao, F.-F.; Ishrat, T. ER stress associated TXNIP-NLRP3 inflammasome activation in hippocampus of human Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem. Int. 2021, 148, 105104. [CrossRef]

- Tsubaki, H.; Mendsaikhan, A.; Buyandelger, U.; Tooyama, I.; Walker, D.G. Localization of thioredoxin-interacting protein in aging and Alzheimer’s disease brains. NeuroSci. 2022, 3, 166-185. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Suh, H.-W.; Chung, J.W.; Yoon, S.-R.; Choi, I. Diverse functions of VDUP1 in cell proliferation, differentiation, and diseases. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2007, 4, 345-351.

- Yu, F.-Y.; Chai, T.F.; He, H.; Hagen, T.; Luo, Y. Thioredoxin-interacting protein (Txnip) gene expression. Sensing oxidative phosphorylation status and glycolytic rate. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 25822-25830. [CrossRef]

- Fabrizio, P.; Liou, L.-L.; Moy, V.N.; Diaspro, A.; Valentine, J.S.; Gralla, R.B.; Longo, V.D. SOD2 functions downstream of Sch9 to extend longevity in yeast. Genetics 2013, 163, 35-46. [CrossRef]

- Harris, N.; Costa, V.; Maclean, M.; Mollapour, M.; Moradas-Ferreira, P.; Piper, P.W. MnSOD overexpression extends the yeast chronological (G(0)) life span but acts independently of Sir2p histone deacetylase to shorten the replicative life span of dividing cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2003, 34, 1599-1606. [CrossRef]

- Van Raamsdonk, J.M.; Hekimi, S. Superoxide dismutase is dispensable for normal animal lifespan. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 5785-5790. [CrossRef]

- Mao, C.; Yuan, J.-Q.; Lv, Y.-B.; Gao, X.; Yin, Z.-X.; Kraus, V.B.; Luo, J.-S.; Chei, C.-L.; Matchar, D.B.; Zeng, Y.; Shi, X.-M. BMC Genetics 2019, 19, 104. [CrossRef]

- Huie, R.E.; Padmaja, S. Reactions of NO and O2•−. Free Radic. Res. Commun. 1993, 18, 195–199. [CrossRef]

- Kissner, R.; Nauser, T.; Bugnon, P.; Lye, P.G.; Koppenol, W.H. Formation and properties of peroxynitrite as studied by laser flash photolysis, high-pressure stopped-flow technique, and pulse radiolysis. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1997, 10, 1285–1292. [CrossRef]

- Nandi, A.; Yan, L.-L. Jana, C.K.; Das, N. Role of catalase in oxidative stress- and age-associated degenerative diseases. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 9613090. [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Deng, C.; Lo, T.-H.; Chan, K.-Y.; Li, X.; Wong, C.-M. Peroxiredoxin, senescence, and cancer. Cells 2022, 11, 1772. [CrossRef]

- Wonsey, D.R.; Zeller, K.I.; Dang, C.V. The c-Myc target gene PRDX3 is required for mitochondrial homeostasis and neoplastic transformation. Prod. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 6649-6655. [CrossRef]

- Huh, J.Y.; Kim, Y.; Jeong, J.; Park, J.; Kim, I.; Huh, K.H.; Kim, Y.S.; Woo, H.A.; Rhee, S.G., Lee, K.-J.; Ha, H. Peroxiredoxin 3 is a key molecule regulating adipocyte oxidative stress, mitochondrial biogenesis, and adipokine expression. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2012, 16, 229-243. [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto-Imoto, H.; Minami, S.; Shioda, T.; Yamashita, Y.; Sakai, S.; Maeda, S.; Yamamoto, T.; Oki, S.; Takashima, M.; Yamamura, T.; Yanagawa, K.; Edahiro, R.; Iwatani, M.; So, M.; Tokumura, A.; Abe, T.; Imamura, R.; Nonomura, N.; Okada, Y.; Ayer, D.E.; Ogawa, H.; Hara, E.; Takabatake, Y.; Isaka, Y.; Nakamura, S.; Yoshimori, T. Age-associated decline of mondoA drives cellular senescence through impaired autophagy and mitochondrial homeostasis. Cell Rep. 2022, 38, 110444. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.; Lingner, J. PRDX1 and MTH1 cooperate to prevent ROS-mediated inhibition of telomerase. Genes Dev. 2018, 32, 658-669. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.; Lingner, J. PRDX1 counteracts catastrophic telomeric cleavage events that are triggered by DNA repair activities post oxidative damage. Cell Rep. 2020, 33, 108347. [CrossRef]

- Aeby, E.; Ahmed, W,; Redon, S.; Simanis, V.; Lingner, J. Peroxiredoxin 1 protects telomeres from oxidative damage and preserves telomeric DNA for extension by telomerase. Cell Rep. 2016, 17, 3107-3114. [CrossRef]

- Chrichton, R.R.; Ward, R.J. Iron homeostasis. Met. Ions Biol. Syst. 1998, 35, 633–665.

- Ponka, P. Cellular iron metabolism. Kidney Int. 1999, 55, S2–S11. [CrossRef]

- Cankurtaran, M.; Yavuz, B.B.; Halil, M.; Ulger, Z.; Haznedaroglu, I.C.; Anogul, S. increased ferritin levels could reflect ongoing aging-associated inflammation and may obscure underlying iron deficiency in the geriatric population. Eur. Geriat. Med. 2012, 3, 277-280. [CrossRef]

- Kirsipuu, T.; Zadorožnaja, A.; Smirnova, J.; Friedemann, M.; Plitz, T.; Tougu, V.; Palumaa, P. Copper(II)-binding equilibria in human blood. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5686. [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, A.; Alonzo, E.; Sauble, E.; Chu, Y.L.; Nguyen, D.; Linder, M.C.; Sato, D.S.; Mason, A.Z. Copper binding components of blood plasma and organs, and their responses to influx of large doses of (65)Cu, in the mouse. Biometals 2008, 21, 525–543. [CrossRef]

- Osaki, S. Kinetic studies of ferrous ion oxidation with crystalline human ferroxidase (ceruloplasmin). J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 241, 5053–5059. [CrossRef]

- Patel, B.N.; Dunn, R.J.; Jeong, S.Y.; Zhu, Q.; Julien, J.-P.; David, S. Ceruloplasmin regulates iron levels in the CNS and prevents free radical injury. J. Neurosci. 2002, 22, 6578-6586. [CrossRef]

- Kono, S.; Yoshida, K.; Tomosugi, N.; Terada, T.; Hamaya, Y.; Kanaoka, S.; Miyajima, H. Biological effects of mutant ceruloplasmin on hepcidin-mediated internalization of ferroportin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1802, 968–975. [CrossRef]

- Kono, S. Aceruloplasminemia: An update. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2013, 110, 125–151. [CrossRef]

- Muckenthaler, M.U.; Rivella, S.; Hentze, M.W.; Galy, B. A red carpet for iron metabolism. Cell 2017, 168, 344–361. [CrossRef]

- Cheli, V.T.; Sekhar, M.; Santiago Conzález, D.A.; Angeliu, C.G.; Denaroso, G.E.; Smith, Z.; Wang, C.; Paez, P.M. The expression of ceruloplasmin in astrocytes is essential for postnatal myelination and myelin maintenance in the adult brain. Glia 2023, 71, 2323-2342. [CrossRef]

- Harris, Z.L.; Takahashi, Y.; Miyajima, H.; Serizawa, M.; MacGillivray, R.T.; Gitlin, J.D. Aceruloplasminemia: Molecular characterization of this disorder of iron metabolism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 2539 –2543. [CrossRef]

- Morita, H.; Ikeda, S.; Yamamoto, K.; Morita, S.; Yoshida, K.; Nomoto, S.; Kato, M.; Yanagisawa, N. Hereditary ceruloplasmin deficiency with hemosiderosis: A clinicopathological study of a Japanese family. Ann. Neurol. 1995, 37, 646–656. [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, K.; Furihata, K.; Takeda, S.; Nakamura, A.; Yamamoto, K.; Morita, H.; Hiyamuta, S.; Ikeda, S.; Shimizu, N.; Yanagisawa, N. A mutation in the ceruloplasmin gene is associated with systemic hemosiderosis in humans. Nat. Genet. 1995, 9, 267–272. [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.Y.; David, S. Age-related changes in iron homeostasis and cell death in the cerebellum of ceruloplasmin-deficient mice. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 9810-9819. [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.S.; Stockwell, B.R. Ferroptosis: Death by lipid peroxidation. Trends Cell Biol. 2016, 26, 165-176. [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Hou, W.; Song, X.; Yu, Y.; Huang, J.; Sun, X.; Kang, R.; Tang, D. Ferroptosis: Process and function. Cell Death Differ. 2016, 23, 369-379. [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Chen, X.-b.; Hong, Y.-c.; Zhu, H.; He, Q.-j.; Yang, B.; Ying, M.-d.; Cao, J. Identification of PRDX6 as a regulator of ferroptosis. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2019, 40, 1334-1342. [CrossRef]

- Torres-Velarde, J.M.; Allen, K.N.; Salvador-Pascual, A.; Leija, R.G.; Luang, D.; Moreno-Santillán, D.D.; Ensminger, D.C.; Vázquez-Medina, J.P. peroxiredoxin 6 suppresses ferroptosis in lung endothelial cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 218, 82-93. [CrossRef]

- Sauret, J.M.; Marinides, G.; Wang, G.K. Rhabdomyolysis. Am. Fam. Phys. 2002, 65, 907-912.

- Rother, R.P.; Bell, L.; Hillman, P.; Gladwin, M.T. The clinical sequelae of intravascular hemolysis and extracellular plasma hemoglobin. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2005, 293, 1653-1662. [CrossRef]

- Kristiansen, M.; Graversen, J.H.; Jacobsen, C.; Sonne, O.; Hoffmann, H.J.; Law, S.K.; Moestrup, S.K. Identification of the haemoglobin scavenger receptor. Nature 2001, 409, 198-201. [CrossRef]

- Chiabrando, D.; Vinchi, F.; Fiorito, V.; Tolosano, E. Haptoglobin and hemopexin in heme detoxification and iron recycling. In: Acute phase proteins – regulation and functions of acute phase proteins; Veas, F., Ed.; Intech: Rijeka, Croatia. 2011; pp. 261-288. [CrossRef]

- Bunn, H.F.; Jandl, J.H. Exchange of heme among hemoglobins and hemoglobin and albumin. J. Biol. Chem. 1968, 243, 465–475. [CrossRef]

- Hvidberg, V.; Maniecki, M.B.; Jacobson, C.; Højrup, P.; Møller, H.J.; Moestrup, S.K. Identification of the receptor scavenging hemopexin-heme complexes. Blood 2005, 106, 2572–2579. [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.; Wang, P.; Zheng, C.; Zhang, H.Y.; Lin, S.; Shao, B.; Zhuge, Q.; Jin, K. Aging systemic milieu impairs outcome after ischemic stroke in rats. Aging Dis. 2017, 8, 519–530. [CrossRef]

- Sarpong-Kumankomah, S.; Knox, K.B.; Kelly, M.E.; Hunter, G.; Popescu, B.; Nichol, H.; Kopciuk, K.; Ntanda, H.; Galler, J. Quantification of human plasma metalloproteins in multiple sclerosis, ischemic stroke and healthy controls reveals an association of haptoglobin-hemoglobin complexes with age. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262160. [CrossRef]

- Schipper, H.M.; Song, W.; Tavitan, A.; Cressatti, M. The sinister face of heme oxygenase-1 in brain aging and disease. Progr. Neurobiol. 2019, 172, 40-70. [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Qu, C.; Zhao, N.; Li, S.; Pu, N.; Song, Z.; Tao, Y. The significance of precisely regulating heme oxygenase-1 expression: Another avenue for treating age-related ocular disease? Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 97, 102308. [CrossRef]

- Picard, E.; Ranchon-Cole, I.; Jonet, L.; Beaumont, C.; Behar-Cohen, F.; Courtois, Y.; Jeanny, J.-C. Light-induced retinal degeneration correlates with changes in iron metabolism gene expression, ferritin level, and aging. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011, 52, 1261–1274. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Yang, K.; He, D.; Yang, B.; Tao, L.; Chen, J.; Wu, Y. Induction of ferroptosis by HO-1 contributes to retinal degeneration in mice with defective clearance of all-trans-retinal. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2023, 194, 245–254. [CrossRef]

- Miyamura, N.; Ogawa, T.; Boylan, S.; Morse, L.S.; Handa, J.T.; Hjelmeland, L.M. Topographic and age-dependent expression of heme oxygenase-1 and catalase in the human retinal pigment epithelium. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2004, 45, 1562–1565. [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Pi, C.; Yang, Y.; Lin, L.; Shi, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; He, X. Nampt expression decreases age-related senescence in rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells by targeting Sirt1. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0170930. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Williams, E.G.; Dubuis, S.; Mottis, A.; Jovaisaite, V.; Houton, S.M.; Argmann, C.A.; Faridi, P.; Wolski, W.; Kutalik, Z.; Zamboni, N.; Auwerx, J.; Aebersold, R. Multilayered genetic and omics dissection of mitochondrial activity in a mouse reference population. Cell 2014, 158, 1415–1430. [CrossRef]

- Migliavacca, E.; Tay, S.K.H.; Patel, H.P.; Sonntag, T.; Civiletto, G.; McFarlane, C.; Forrester, T.; Barton, S.J.; Leow, M.K.; Antoun, E.; Charpagne, A.; Chong, Y.S.; Descombes, P.; Feng, L.; Francis-Emmanuel, P.; Garratt, E.S.; Giner, M.P.; Green, C.O.; Karaz, S.; Kothandaraman, N.; Marquis, J.; Metairon, S.; Moco, S.; nelson, G.; Ngo, S.; Pleasants, T.; Raymond, F.; sayer, A.A.; Sim, C.M.; Slater-Jefferies, J.; Syddall, H.E.; Tan, P.F.; Titcombe, P.; Vaz, C.; Wetbury, L.D.; Wong, G.; Yonghui, W.; Cooper, C.; Sheppard, A.; Godfey, K.M.; Lillycrop, K.A.; Karnani, N.; Feige, J.N. Mitochondrial oxidative capacity and NAD+ biosynthesis are reduced in human sarcopenia across ethnicities. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5808. [CrossRef]

- Sorrentino, V.; Romani, M.; Mouchiroud, L.; Beck, J.S.; Zhang, H.; D’Amico, D.; Moullan, N.; Potenza, F.; Schmid, A.W.; Rietsch, S.; Counts, S.E.; Auwerx, J. Enhancing mitochondrial proteostasis reduces amyloid-β proteotoxicity. Nature 2017, 552, 187–193. [CrossRef]

- Beck, J.S.; Mufson, E.J.; Counts, S.E. Evidence for mitochondrial UPR gene activation in familial and sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2016, 13, 610–614. [CrossRef]

- Eisner, V.; Picard, M.; Hajnóczky, G. Mitochondrial dynamics in adaptive and maladaptive cellular stress responses. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018, 20, 755–765. [CrossRef]

- Youle, R.J.; van der Bliek, A.M. Mitochondrial fission, fusion, and stress. Science 2012, 337, 1062–1065. [CrossRef]

- Udagawa, O.; Ishihara, T.; Maeda, M.; Matsunaga, Y.; Tsukamoto, S.; Kawano, N.; Miyado, K.; Shitara, H.; Yokota, S.; Nomura, M.; Mihara, K.; Mizushima, N.; Ishihara, N. Mitochondrial fission factor Drp1 maintains oocyte quality via dynamic rearrangement of multiple organelles. Curr. Biol. 2014, 24, 2451–2458. [CrossRef]

- Kageyama, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Roda, R.; Fukaya, M.; Wakabayashi, J.; Wakabayashi, N.; Kensler, T.W.; Reddy, H.; Iijima, M.; Sesaki, H. Mitochondrial division ensures the survival of postmitotic neurons by suppressing oxidative damage. J. Cell Biol. 2012, 197, 535–551. [CrossRef]

- Glickman, M.H.; Ciechanover, A. The ubiquitin-proteasome proteolytic pathway: Destruction for the sake of construction. Physiol. Rev. 2002, 82, 373-429. [CrossRef]

- Pickart, C.M.; Eddins, M.J. Ubiquitin: Structure, functions, mechanisms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2004, 1695 55-72. [CrossRef]

- López-Otin, C.; Blasco, M. A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell, 2013, 153, 1194-1217. [CrossRef]

- Calderwood, S.K.; Murshid, A.; Prince, T. The shock of aging: Molecular chaperones and the heat shock response in longevity and aging--a mini-review. Gerontology, 2009, 55, 550-558. [CrossRef]

- Löw, P. The role of ubiquitin-proteasome system in aging. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2011, 172, 39-43. [CrossRef]

- Saez, I.; Vilchez, D. The mechanistic links between proteasome activity, aging and age-related diseases. Curr. Genomics 2014, 15, 38-51. [CrossRef]

- Frankowska, N.; Lisowska, K.; Witkowski, J.M. Proteolysis dysfunction in the process of aging and age-related diseases. Front. Aging 2022, 3, 927630. [CrossRef]

- Ponnappan, U.; Zhong, M.; Trebilcock, G.U. Decreased proteasome-mediated degradation in T cells from the elderly: A role in immune senescence. Cell. Immunol. 1999, 192, 167–174. [CrossRef]

- Chondrogianni, N.; Stratford, F.L.L.; Trougakos, I.P.; Friguet, B.; Rivett, A.J.; Gonos, E.S. Central role of the proteasome in senescence and survival of human fibroblasts. Induction of a senescence-like phenotype upon its inhibition and resistance to stress upon its activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 28026–28037. [CrossRef]

- Dahlmann, B. Role of proteasomes in disease, BMC Biochem. 2007, 8 (suppl. 1) S3. [CrossRef]

- Mizushima, N.; Komatsu, M. Autophagy: Renovation of cells and tissues. Cell 2011, 147, 728-741. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, S. Choose delicately and reuse adequately: The newly revealed process of autophagy. Biol. Pharmaceut. Bull. 2015, 38, 1098-1103. [CrossRef]

- Collins, T.J.; Berridge, M.J.; Lipp, P.; Bootman, M.D. Mitochondria are morphologically and functionally heterogeneous within cells. EMBO J. 2002, 21, 1616–1627. [CrossRef]

- Hoshino, A.; Mita, Y.; Okawa, Y.; Ariyoshi, M.; Iwai-Kanai, E.; Ueyama, T.; Ikeda, K.; Ogata, T.; Matoba, S. Cytosolic p53 inhibits parkin-mediated mitophagy and promotes mitochondrial dysfunction in the mouse heart. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2308. [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, T.G.; Prescott, A.R.; Allen, G.F.G.; Tamjar, J.; Munson, M.J.; Thomson, C.; Muqit, M.M.K.; Ganley, I.G. mito-QC illuminates mitophagy and mitochondrial architecture in vivo. J. Cell Biol. 2016, 214, 333-345. [CrossRef]

- Lazarou, M.; Sliter, D.A.; Kane, L.A.; Sarraf, S.A.; Wang, C.; Burman, J.L.; Sideris, D.P.; Fogel, A.I.; Youle, R.J. The ubiquitin kinase PINK1 recruits autophagy receptors to induce mitophagy. Nature 2015, 524, 309-314. [CrossRef]

- García-Prat, L.; Martinez-Vicente, M.; perdiguero, E.; ortet, L.; Rodriguez-Ubreva, J.; Rebello, E.; Ruiz-Bonilla, V.; Gutarra, S.; Ballestar, E.; Serrano, A.L.; Sandri, M.; Muñoz-Cánoves, P. Autophagy maintains stemness by preventing senescence. Nature 2016, 529, 37–42. [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.Y.; Blum, A.; Liu, J.; Finkel, T. The role of mitochondria in aging. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 3662-3670. [CrossRef]

- Pinti, M.; Cevenini, E.; Nasi, M.; de Biasi, S.; Salvioli, S.; Monti, D.; Benatti, S.; Gibellini, L.; Cotichini, R.; Stazi, M.A.; Trenti, T.; Franceschi, C.; Cossarizza, A. Circulating mitochondrial DNA increases with age and is a familiar trait: Implications for “inflamm-aging”. Eur. J. Immunol. 2014, 44, 1552-1562. [CrossRef]

- Mills, E.L.; Kelly, B.; O’Neill, L.A.J. Mitochondria are the powerhouses of immunity. Nat. Immunol. 2017, 18, 488–498. [CrossRef]

- Sliter, D.A.; Martinez, J.; Hao, L.; Chen, X.; Sun, N.; Fischer, T.D.; Burman, J.L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; narenda, D.P.; Borsche, M.; Klein, C.; Youle, R.J. Parkin and PINK1 mitigate STING-induced inflammation. Nature 2018, 561, 258–262. [CrossRef]

- Franceschi, C.; Garagnani, P.; Parini, P.; Giuliani, C.; Santoro, A. Inflammaging: A new immune-metabolic viewpoint for age-related diseases. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2018, 14, 576–590. [CrossRef]

- Penna, F.; Ballarò, R.; Beltrá, M.; de Lucia, S.; Costelli, P. Modulating metabolism to improve cancer-imduced muscle wasting. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longevity 2018, 7153610. [CrossRef]

- Argilés, J.M.; Busquets, S.; Stemmler, B.; López-Soriano, F.J. Cancer cachexia: Understanding the molecular basis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14,754-762. [CrossRef]

- Bye, A.; Sjøblom, B.; Wentzel-Larsen, T.; Grønberg; B.H.; baracos, V.E.; Hjemstad, M.J.; Aass, N.; Bremnes, R.M.; Fløtten, Ø.; Jordhøy, M. Muscle mass and association to quality of life in non-small cell lung cancer patients. J. Cachexia, Sarcopenia Muscle 2017, 8, 759-767. [CrossRef]

- Nipp, R.D.; Fuchs, G.; El-Jawahri, A.; Mario, J.; Troschel, E.M.; Greer, J.A.; Gallgher, E.R.; Jackson, V.A.; Kambadakone, A.; Hong, T.S.; Temel, J.S.; Fintelmann, F.J. Sarcopenia is associated with quality of life and depression in patients with advanced cancer. Oncologist 2017, 23, 97–104. [CrossRef]

- Morley, J.E.; Anker, S.D.; Evans, W.J. Cachexia and aging: An update based on the fourth international cachexia meeting. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2009, 13, 47-55. [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Garcia, J.M. Sarcopenia, cachexia and aging: Diagnosis, mechanisms and therapeutic options. Gerontology 2014, 60, 294-305. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, C.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Qian, P.; Huang, H. Inflammation and aging: Signaling pathways and intervention therapies. Signal Transd. Targ. Ther. 2023, 8, 239. [CrossRef]

- De la Fuente, M.; Miquel, J. An update of the oxidation-inflammation theory of aging: The involvement of the immune system in oxi-inflamm-aging. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2009, 15, 3003–3026. [CrossRef]

- Martinez de Toda, I.; Ceprian, N.; Diaz-Del Cerro, E.; De la Fuente, M. The role of immune cells in oxi-inflamm-aging. Cells 2021, 10, 2974. [CrossRef]

- Santoro, A.; Bientinesi, E.; Monti, D. Immunosenescence and inflammaging in the aging process: Age-related diseases or longevity? Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 71, 101422. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.; Thadathil, N.; Selvarani, R.; Nicklas, E.H.; Wang, D.; Miller, B.F.; Richardson, A.; Deepa, S.S. Necroptosis contributes to chronic inflammation and fibrosis in aging liver. Aging Cell 2021, 20, e13512. [CrossRef]

- Miao, E.A; Leaf, I.A.; Treuting, P.M.; Mao, D.P.; Dors, M.; Sarkar, A.; Warren, S.E.; Wewers, M.D.; Aderem, A. Caspase-1-induced pyroptosis is an innate immune effector mechanism against intracellular bacteria. Nat. Immunol. 2010, 11, 1136–1142. [CrossRef]

- Duewell, P.; Kono, H.; Rayner, K.J.; Sirios, C.M.; Vladimer, G.; Bauernfeind, F.G.; Abela, G.S.; Franchi, L.; Nuñez, G.; Schnurr, M.; Espevik, T.; Lien, E.; Fitzgerald, K.A.; Rock, K.L.; Moore, K.J.; Wright, S.D.; Hornung, V.; Latz, E. NLRP3 inflammasomes are required for atherogenesis and activated by cholesterol crystals. Nature 2010, 464, 1357–1361. [CrossRef]

- Voet, S.; Srinivasan, S.; Lamkanfi, M.; van Loo, G. Inflammasomes in neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative diseases. EMBO Mol. Med. 2019, 11, e10248. [CrossRef]

- Ward, R.J; Zucca, F.A.; Duyn, J.H.; Crichton, R.R.; Zecca, L. The role of iron in brain ageing and neurodegenerative disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2014, 13, 1045–1060. [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Ardehali, H.; Min, J.; Wang, F. The molecular and metabolic landscape of iron and ferroptosis in cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2023, 20, 7–23. [CrossRef]

- Pittet, D.; Wenzel, R.P. Nosocomial bloodstream infections. Secular trends in rates, mortality, and contribution to total hospital deaths. Arch. Intern. Med. 1995, 155, 1177–1184. [CrossRef]

- Llewelyn, M.J.; Cohen, J. Tracking the microbes in sepsis: Advancements in treatment bring challenges for microbial epidemiology. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2007, 44, 1343–1348. [CrossRef]

- Kollef, K.E.; Schramm, G.E.; Wills, A.R.; Reichley, R.M.; Mirek, S.T.; Kollef, M.H. Predictors of 30-day mortality and hospital costs in patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia attributed to potentially antibiotic-resistant gram-negative bacteria. Chest 2008, 134, 281–287. [CrossRef]

- Babu, M.; Menon, V.P.; Devi, P.U. Prevalence of antimicrobial resistant pathogens in severe sepsis and septic shock patients. J. Young Pharm. 2018, 10, 358–361. [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.-L.; McGinley, J.P.; Drysdale, S.B.; Pollard, A.J. Epidemiology and immune pathogenesis of viral sepsis. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2147. [CrossRef]

- Podnos, Y.D.; Jiminez, J.C.; Wilson, S.E. Intraabdominal sepsis in elderly persons. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002, 35, 62–68. [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.D.; Braun, L.A.; Cooper, I.M.; Johnston, J.; Weiss, R.V.; Qualy, R.I.; Linde-Zwirble, W. Hospitalized cancer patients with severe sepsis: Analysis of incidence, mortality, and associated costs of care. Crit. Care 2004, 8, R291–R298. [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, D.; Parthasarathy, S.; Carew, T.E.; Khoo, J.C.; Witztum. Beyond cholesterol: Modification of low-density lipoprotein that increases its atherogenicity. N. Engl. J. Med. 1989, 320, 915-924. [CrossRef]

- Lusis, A.J. Atherosclerosis. Nature 2000, 407, 233-241. [CrossRef]

- Wick, G.; Knoflach, M, Xu, Q. Autoimmune and inflammatory mechanisms in atherosclerosis. Annu. Rev. Atheroscl. 2004,22, 361-403. [CrossRef]

- Tabas, I.; Garcia-Gardeña, G.; Owens, G.K. Recent insights into the cellular biology of atherosclerosis. J. Cell Biol. 2015, 209, 13-22. [CrossRef]

- Bergheanu, S.C.; Bodde, M.C.; Jukema, J.W. Pathophysiology and treatment of atherosclerosis. Current view and future perspective on lipoprotein modification treatment. Neth. Heart 2017, 25, 231-242. [CrossRef]

- Gisterå, A.; Hansson, G. The immunology of atherosclerosis. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2017, 13, 368-380. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.C.; Bennett, M. Aging and atherosclerosis. Mechanisms, functional consequences, and potential therapeutics for cellular senescence. Circ. Res. 2012, 111, 245-259. [CrossRef]

- Head, T.; Daunert, S.; Goldschmidt-Clermont, P.J. The aging risk and atherosclerosis: A fresh look at arterial homeostasis. Front. Genet. 2017, 8, 216. [CrossRef]

- Vecoli, C.; Borghini, A.; Andreassi, M.G. The molecular biomarkers of vascular aging and atherosclerosis: Telomere length and mitochondrial DNA4977 common deletion. Mut. Res. 2020, 784, 108309. [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.J.; Hong, R.; Teo, L.L.Y.; Tan, R.-S.; Koh, A.S. Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in aging and the role of advanced cardiovascular imaging. Cardiovasc. Health 2024, 1, 11. [CrossRef]

- Daugherty, A.; Dunn, J.L.; Rateri, D.L.; Heinecke, J.W. Myeloperoxidase, a catalyst for lipoprotein oxidation, is expressed in human atherosclerotic lesions. J. Clin. Investig. 1994, 94, 437-444. [CrossRef]

- Hazen, S.L.; Heinecke, J.W. 3-Chlorotyrosine, a specific marker of myeloperoxidase-catalyzed oxidation, is markedly elevated in low density lipoprotein isolated from human atherosclerotic intima. J. Clin. Investig. 1997, 99, 2075-2081. [CrossRef]

- Malle, E.; Marsche, G.; Arnhold, J.; Davies, M.J. Modification of low-density lipoprotein by myeloperoxidase-derived oxidants and reagent hypochlorous acid. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2006, 1761, 392-415. [CrossRef]

- Balla, G.; Jacob, H.S.; Eaton, J.W.; Belcher, J.D.; Vercelotti, G.M. Hemin: A possible physiological mediator of low density lipoprotein oxidation and endothelial injury. Arterioscl. Thromb. 1991, 11, 1700-1711. [CrossRef]

- Jeney, V.; Balla, J.; Yachie, A.; Varga, Z.; Vercelotti, G.M.; Eaton, J.W.; Balla, G. Pro-oxidant and cytotoxic effects of circulating heme. Blood 2002, 100, 879-887. [CrossRef]

- Reiter, C.D.; Wang, X.; Tanus-Santos, J.E.; Hogg, N.; Cannon III, R.O.; Schechter, A.N.; Gladwin, M.T. Cell-free hemoglobin limits nitric oxide bioavailability in sickle-cell disease. Nat. Med. 2002, 8, 1383-1389. [CrossRef]

- Eich, R.F.; Li, T.; Lemon, D.D.; Doherty, D.H.; Curry, S.R.; Aitken, J.F.; Mathews, A.J.; Johnson, K.A.; Smith, R.D.; Philips, Jr. G.N.; Olson, J.S. Mechanisms of NO-induced oxidation of myoglobin and hemoglobin. Biochemistry 1996, 35, 6076-6983. [CrossRef]

- Olson, J.S.; Foley, E.W.; Rogge, C.; Tsai, A.L.; Doyle, M.P.; Lemon, D.D. NO scavenging and the hypertensive effect of hemoglobin-based blood substitutes. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2004, 36, 685-697. [CrossRef]

- Flögel, U.; Fago, A.; Rassaf, T.; Keeping the heart in balance: The functional interactions of myoglobin with nitrogen oxides. J. Exp. Biol. 2010, 213, 2726-2733. [CrossRef]

- Eiserich, J.P.; Baldus, S.; Brennan, M.-L.; Ma, W.; Zhang, C.; Tousson, A.; Castro, L.; Lusis, A.J.; Nauseef, W.M.; White, C.R.; Freeman, B.A. Myeloperoxidase, a leukocyte-derived vascular NO oxidase. Science 2002, 196, 2391–2394. [CrossRef]

- Ariesen, M.J.; Claus, S.P.; Rinkel, G.J.; Algra, A. Risk factors for intracerebral hemorrhage in the general population: A systematic view. Stroke 2003, 34, 2060-2065. [CrossRef]

- Jani, B.; Rajkumar, C. Ageing and vascular ageing. Postgrad. Med. J. 2006, 82, 357-362. [CrossRef]

- Dastur, C.K.; Yu, W. Current management of spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage. Stroke Vasc. Neurol. 2017, e000047. [CrossRef]

- Flemmig, J.; Schlorke, D.; Kühne, F.-W.; Arnhold, J. Inhibition of heme-induced hemolysis of red blood cells by the chlorite-based drug WF10. Free Rad. Res. 2016, 50, 1386-1395. [CrossRef]

- Deuel, J.W.; Schaer, C.A.; Boretti, F.S.; Opitz, L.; Garcia-Rubio, I.; Baek, J.H.; Spahn, D.R.; Buehler, P.W.; Schaer, D.J. Hemoglobinuria-related acute kidney injury is driven by intrarenal oxidative reactions triggering a heme toxicity response. Cell Death Dis. 2016, 7, e2064. [CrossRef]

- Rosendaal, F.R.; van Hylckama Vlieg A.; Doggen, C.J.M. Venous thrombosis in the elderly. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2007, 5 (Suppl. 1), 310-317. [CrossRef]

- Engbers, M.J.; van Hylckama Vlieg A.; Rosendaal, F.R. Venous thrombosis in the elderly: Incidence, risk factors and risk groups. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2010, 8, 2105-2112. [CrossRef]

- Akrivou, D.; Perlepe, G.; Kirgou, P.; Gourgoulianis, K.I.; Malli, F. Pathophysiological aspects of aging in venous thromboembolism: An update. Medicina 2022, 58, 1078. [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, A.; Dunning, T.; Rodriguez-Mañas, L. Diabetes in older people: New insights and remaining challenges. Lancet Diabet. Endocrinol. 2015, 3, 275-285. [CrossRef]

- Arnhold, J. Cell and tissue destruction in selected disorders. In Cell and Tissue Destruction. Mechanisms, Protection, Disorders; Academic Press: London, UK; San Diego, CA, USA; Cambridge, MA, USA; Oxford, UK, 2020; pp. 249–287. [CrossRef]

- Potenza, M.A.; Gagliardi, S.; Nacci, C.; Carratu, M.R.; Montagnani, M. Endothelial dysfunction in diabetes: From mechanisms to therapeutic targets. Curr. Med. Chem. 2009, 16, 94-112. [CrossRef]

- Hirose, A.; Tanikawa, T.; Mori, H.; Okada, Y.; Tanaka, Y. Advanced glycation end products increase endothelial permeability through RAGE/Rho signaling pathway. FEBS Lett. 2010, 584, 61-66. [CrossRef]

- Koenig, R.J.; Peterson, C.M.; Jones, R.L.; Saudek, C.; Lehrmann, M.; Cerami, A. Correlation of glucose regulation and hemoglobin A1c in diabetes mellitus. N. Engl. J. Med. 1976, 295, 417-420. [CrossRef]

- Bunn, H.F.; Gabbay, K.H.; Gallop, P.M. The glycosylation of hemoglobin: Relevance to diabetes mellitus. Science 1978, 200, 21-27. [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Ku, Y.-H.; Ho, J.-X.; Kim, Y.-K.; Suh, J.-S.; Singh, M. Progressive impairment of erythrocyte deformability as indicator of microangiopathy in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin. Hemorheol. Microcirc. 2007, 36, 253-261.

- Babu, N.; Singh, M. Influence of hyperglycemia on aggregation, deformability and shape parameters of erythrocytes. Clin. Hemorheol. Microcirc. 2004, 31, 273-280.

- Kung, C.-M.; Tseng, Z.-I.; Wang, H.-L. Erythrocyte fragility with level of glycosylated hemoglobin in type 2 diabetic patients. Clin. Hemorheol. Microcirc. 2009, 43, 345-351. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Smart, T.; Nobre-Cordosa, J.; Richards, C.; Bhatnagar, R.; Tufail, A. Shima, D.; Jones, P.H.; Pavesio, C. Assessment of red blood cell deformability in type 2 diabetes mellitus and diabetic retinopathy by dual optical tweezers stretching technique. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 15873. [CrossRef]

- Ernst, E.; Matrai, A. Altered red and white blood cell rheology in type II diabetes. Diabetes 1986, 35, 1412-1415. [CrossRef]

- Popov, D. Endothelial cell dysfunction in hyperglycemia: Phenotypic change, intracellular signaling modification, ultrastructural alteration, and potential clinical outcomes. Int. J. Diabetes Mellitus 2010, 2, 189-195. [CrossRef]

- Popov, D. Towards understanding the mechanisms of impeded vascular function in the diabetic kidney. In Simionescu, M.; Sima, A.; Popov, D. (Eds.) Cellular dysfunction in atherosclerosis and diabetes – Reports from bench to bedside. Publishing House Rom, Acad. Bucharest, 2004, pp. 244-259.

- Dokken, B.B. The pathophysiology of cardiovascular disease and diabetes: Beyond blood pressure and lipids. Diabetes Spectr. 2008, 21, 160-165. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Cheng, J.; Wang, D.; Hu, X.; Xie, Y.; Stitham, J.; Atteva, G.; Du, J.; Tang, W.H.; Lee, S.H.; Leslie, K.; Spollett, G.; Liu, Z.; Herzog, E.; Herzog, R.I.; Lu, J.; Martin, K.A.; Hwa, J. Hyperglycemia repression of miR-24 coordinately upregulates endothelial cell expression and secretion of von Willebrand factor. Blood 2015, 125, 3377-3387. [CrossRef]

- Whincup, P.H.; Danesh, J.; Walker, M.; Lennon, L.; Thomson, A.; Appleby, P.; Rumley, A.; Lowe, G.D. Von Willebrand factor and coronary heart disease: Prospective study and meta-analysis. Eur. Heart J. 2002, 23, 1764-1770. [CrossRef]

- Frankel, D.S.; Meigs, J.B.; Massaro, J.M.; Wilson, P.W.; O’Donnell, C.J.; D’Agostino, R.B.; Tofler, G.H.; Von Willebrand factor, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and risk of cardiovascular disease: The Framingham offspring study. Circulation 2008, 118, 2533-2539. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Smyth, M.J. Targeting cancer-related inflammation in the era of immunotherapy. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2017, 95, 325–332. [CrossRef]

- Dunn, G.P.; Bruce, A.T.; Ikeda, H.; Old, L.J.; Schreiber, R.D. Cancer immunoediting: From immunosurveillance to tumor escape. Nat. Immunol. 2002, 3, 991–998. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Smyth, M.J. Myeloid immunosuppression and immune checkpoints in the tumor microenvironment. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2020, 17, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Labani-Motlagh, A.; Ashja-Mahdavi, M.; Loskog, A. The tumor microenvironment: A milieu hindering and obstructing antitumor immune response. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 940. [CrossRef]

- Barnestein, R.; Galland, L.; Kalfeist, L.; Ghiringhelli, F.; Ladoire, S.; Limagne, E. Immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment modulation by chemotherapies and targeted therapies to enhance immunotherapy effectiveness. OncoImmunology 2022, 11, 2120676. [CrossRef]

- Tie, Y.; Tang, F.; Wei, Y.-Q.; Wie, X.-W. Immunosuppressive cells in cancer: Mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 15, 61. [CrossRef]

- Othman, N.; Jamal, R.; Abu, N. Cancer-derived exosomes as effectors of key inflammation-related players. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2103. [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Zhang, S. Tumor-associated macrophages and their functional transformation in the hypoxic tumor microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 741305. [CrossRef]

- Pastorevka, S.; Ratcliffe, P.J.; Pastorek, J. Molecular mechanisms of carbonic anhydrase IX-mediated pH regulation under hypoxia. J. Compil. 2008, 101 (Suppl. 4) 8-15. [CrossRef]

- Kaluz, S.; Kaluzová, M.; Liao, S.-Y.; Lerman, M.; Stanbridge, E.J. Transcriptional control of the tumor- and hypoxia-marker carbonic anhydrase 9: A one transcription factor (HIF-1) show? Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2009, 1795, 162-177. [CrossRef]

- Becker, H.M. Carbonic anhydrase IX and acid transport in cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2020, 122, 157-167. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.; Jäättelä, Liu, B. pH gradient reversal fuels cancer progression. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2020, 125, 105796. [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Jeong, J.; Seong, S.; Kim, W. In silico evaluation of natural compounds for an acidic extracellular environment in human breast cancer. Cells 2021, 10, 2673. [CrossRef]

- Logozzi, M.; Spugnini, E.; Mizzoni, D.; Di Raimo, R.; Fais, S. Extracellular acidity and increased exosome release as key phenotypes of malignant tumors. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2019, 38, 93–101. [CrossRef]

- Riek, R.; Eisenberg, D.S. The activities of amyloids from a structural perspective. Nature 2016, 539, 227-235. [CrossRef]

- Walti, M.A.; Ravotti, F.; Arai, H.; Glabe, C.G.; Wall, J.S.; Bockmann, A.; Guntert, P.; Meier, B.H.; Riek, R. Atomic-resolution structure of a disease-relevant Abeta(1-42) amyloid fibril. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E4976-E4984. [CrossRef]

- Fezoui, Y.; Teplow, D.B. Kinetic studies of amyloid-bate protein fibril assembly. Differential effects of alpha-helix stabilization. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 36948-36954. [CrossRef]

- Uversky, V.N. Protein misfolding in lipid-mimetic environments. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2015, 855, 33-66. [CrossRef]

- Prasad, H.; Rao, R. Endosomal acid-base homeostasis in neurodegenerative diseases. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2020, 185, 195-231. [CrossRef]

- Decker, Y.; Németh, E.; Schomburg, R.; Chemla, A.; Fülöp, L.; Menger, M.D.; Liu, Y.; Fassbender, K. Decreased pH in the aging brain and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2021, 101, 40-49. [CrossRef]

- Hagihara, H.; Miyakawa, T. Decreased brain pH correlated with progression of Alzheimer disease neuropathology: A systematic review and meta-analyses of postmortem studies. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2024, pyae047. [CrossRef]

- Levi, S.; Finazzi, D. Neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation: Update on pathogenic mechanisms. Front. Pharmacol. 2014, 5, 99. [CrossRef]

- Mena, N.P.; Urrutia, P.J.; Lourido, F.; Carrasco, C.M.; Núñez, M.T. Mitochondrial iron homeostasis and its dysfunction in neurodegenerative disorders. Mitochondrion 2015, 21, 92-105. [CrossRef]

- Stockwell, B.R.; Angeli, J.P.F.; Bayir, H.; Bush, A.I.; Conrad, M.; Dixon, S.; Fulda, S.; Gascon, S.; Hatzios, S.K.; Kagan, V.; Noel, K.; Jiang, X.; Linkermann, A.; Murphy, M.E.; Overholtzer, M.; Oyagi, A.; Pagnussat, G.; Park, J.; Ran, Q.; Rosenfeld, C.S.; Salnikow, K.; Tang, D.; Torti, F.; Torti, S.; Toyokuni, S.; Woerpel, K.A.; Zhang, D.D. Ferroptosis: A regulated death nexus linking metabolism, redox biology, and disease. Cell 2017, 171, 273-285. [CrossRef]

- De Bie, P.; Muller, P.; Wijmenga, C.; Klomp, L.W.J. Molecular pathogenesis of Wilson and Menkes disease: Correlation of mutations with molecular defects and disease phenotypes. J. Med. Genet. 2007, 44, 673–688. [CrossRef]

- Squitti, R.; Pasqualetti, P.; Dal Forno, G.; Moffa, F.; Cassetta, E.; Lupoi, D.; Vernieri, F.; Rossi, L.; Baldassini, M.; Rossini, P.M. Excess of serum copper not related to ceruloplasmin in Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2005, 64, 1040–1046. [CrossRef]

- Squitti, R.; Bressi, F.; Pasqualetti, P.; Bonomini, C.; Ghidoni, R.; Binetti, G.; Cassetta, E.; Moffa, F.; Ventriglia, M.; Vernieri, F.; Rossini, P.M. Longitudinal prognostic value of serum “free” copper in patients with Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2009, 72, 50–55. [CrossRef]

- Righy, C.; Bozza, M.T.; Oliveira, M.F.; Bozza, F.A. Molecular, cellular and clinical aspects of intracerebral hemorrhage: Are the enemies within? Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2016, 14, 392–402. [CrossRef]

- Chiabrando, D.; Fiorito, V.; Petrillo, S.; Tolosano, E. Unraveling the role of heme in neurodegeneration. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 712. [CrossRef]

- Belcher, J.D.; Chen, C.; Nguyen, J.; Milbauer, L.; Abdulla, F.; Alayash, A.I.; Smith, A.; Nath, K.A.; Hebbel, R.P.; Vercelotti, G.M. Heme triggers TLR4 signaling leading to endothelial cell activation and vaso-occlusion in murine sickle cell disease. Blood 2014, 13, 377-390. [CrossRef]

- Chiziane, E.; Telemann, H.; Krueger, M.; Adler, J.; Arnhold, J.; Alia, A.; Flemmig, J. Free heme and amyloid-β: A fatal liaison in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018, 61, 963-984. [CrossRef]

- Song, I.-U.; Kim, Y.-D.; Chung, S.-W.; Cho, H.J. Association between serum haptoglobin and the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Intern. Med. 2015, 54, 453-457. [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, A.; Clark, M.; So, P.-W. The aging of iron man. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2018, 10, 65. [CrossRef]

- Moshage, H. Cytokines and the hepatic acute phase response. J. Pathol. 1997, 181, 74-80. [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Maita, D.; Thundivalappil, S.R.; Riley, F.E.; Hambsch, J.; van Marter, L.J.; Christou, H.A.; Berra, L.; Fagan, S.; Christiani, D.C.; Warren, H.S. Hemopexin in severe inflammation and infection: Mouse models and human diseases. Crit. Care 2015, 19, 166. [CrossRef]

| Predominant Features or Properties | Initiation and Propagation of Inflammation | Resolution of Inflammation |

|---|---|---|

| Immune response | Recruitment and activation of immune cells | Deactivation of immune cells, immunosuppression |

| Presence of molecular patterns | yes | no |

| Main physiological processes | Elimination of pathogens, removal of damaged cells and cell debris | Repair processes, synthesis of novel extracellular matrix |

| Typical mediators | IL-1, IL-6, IL-15, IL-8, TNF-α | TGF-β, IL-10, VEGF, lipoxins |

| Presence of CRP and SAA | enhanced values | decreasing values |

| Macrophage subtypes | M1 type | M2 type |

| Major pathways for ATP production in macrophages | Glycolysis | oxidative phosphorylation |

| Presence of MDSCs | low | enhanced |

| Cytotoxic Agent | Antagonizing Principles | References |

|---|---|---|

| Superoxide anion radicals | Superoxide dismutases | [58,59,60,61] |

| Hydrogen peroxide | Catalase, peroxiredoxins, glutathione peroxidases | [62,63,64] |

| Hydroxyl radicals | Limited protection by carbohydrates | [65] |

| Free transition metal ions | Proper control over all aspects of iron and copper ion metabolism | [66,67,68,69,70] |

| Myeloperoxidase | Ceruloplasmin | [71,72,73,74] |

| Hypochlorous acid, hypobromous acid | SCN-, taurine, glutathione, ascorbate | [75,76,77] |

| Hypothiocyanite | glutathione | [78] |

| Elastase | α1-antitrypsin (A1AT), secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor (SLPI), elafin, serpin B1, α2-macroglobulin | [79,80,81,82,83] |

| Cathepsin G | A1AT, SLPI, α1-antichymotrypsin | [79,80,81,84,85,86] |

| Proteinase 3 | A1AT, elafin | [79,80,82,83] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).