1. Introduction

Climate change has become one of the most pressing challenges of our time, with global temperatures rising at an unprecedented rate. A significant contributor to this trend is the steady increase in waste heat generated by human activities, which intensifies the concentration of greenhouse gases, primarily carbon dioxide, in the atmosphere [

1]. Since the mid-20th century, the industrial combustion of fossil fuels has been a major source of CO₂ emissions, with large-scale industries responsible for a substantial portion of global energy losses. In Europe alone, these industries account for 21% of wasted energy, most of which is dissipated into the atmosphere as heat, representing over a quarter of the continent's primary energy consumption [

2].

To address these challenges, numerous green technologies are being developed to harvest energy from different physical domains and transform it into electrical energy [3, 4], thereby helping to reduce the carbon footprint. Thermoelectric generators (TEGs) are at the forefront of such technologies, harvesting heat to produce energy [

5]. This dual benefit simultaneously generates electrical energy while reducing heat emissions into the atmosphere. Waste Heat Recovery Systems (WHRS) [6, 7] are a key example, transforming dissipated heat into electrical energy. These systems rely on the Seebeck effect, the transduction mechanism used in thermoelectric devices, typically Peltier cells. Based on the Carnot cycle for waste heat, WHRS are generally designed to operate in sectors with medium-temperature differentials. For instance, the WHRS implemented at

Bodegas Miguel Torres (HRS-Torres) [

8] is used to harvest energy and monitor the status of a pellet stove.

While the energy output of thermoelectric devices is still insufficient to power systems with high energy demands, they can generate enough energy to sustain Wireless IoT devices. This makes IoT applications one of the primary use cases where TEG devices can provide sufficient energy to power systems [3, 9, 10]. Many IoT nodes today rely on batteries, which are not only expensive and environmentally harmful but also pose significant limitations in industrial environments. In contrast, WHRS can harvest energy from any hot surface, enabling self-powered IoT nodes in remote or hard-to-reach areas of industrial facilities, without requiring electrical power distribution. Furthermore, WHRS can operate in hazardous environments where batteries or grid power would pose safety risks.

This paper expands on this concept by incorporating the benefits of Narrowband IoT (NB-IoT) technology, a key enabler for robust and secure long-range wireless communications in industrial settings. NB-IoT eliminates the need for extensive wiring, significantly reducing installation costs and complexity in large facilities. Its robustness and security make it particularly well-suited for harsh industrial environments, including explosive or high-temperature areas. For example, in a petroleum refinery, the integration of WHRS-powered IoT nodes with NB-IoT technology has demonstrated a reliable and efficient solution for condition monitoring and predictive maintenance, even in challenging operational conditions. Additionally, this protocol will allow the implementation of the spectrum analysis for electric machine predictive maintenance standard implementation (ISO 10816 [

11]).

Building on prior work, this paper presents an improved architecture for Waste Heat Recovery Systems (IoT-WHRS), designed to power IoT nodes. This new architecture enhances the performance and efficiency of earlier designs by addressing key limitations, particularly those related to thermal path optimization and air gaps within the system enclosure. The complete thermoelectric system model includes the contribution of the TEG and all other components of the WHRS. A dynamic model for the thermoelectric device is employed, which captures its behaviour in transforming heat power into electrical energy [

12]. However, the physical parameters of TEG cells, such as the Seebeck coefficient, thermal conductivity, and thermal resistivity, are often not provided by manufacturers and must be calculated using datasheet figures [

13]. Effective parameter calculation methods are applied in this study [

14].

The WHRS design also incorporates thermal resistances and capacitances for all elements along the thermal path, including contact resistances and heatsink fin behaviour, which significantly affect system efficiency [15, 16]. Within this context, this paper outlines the methodology for modelling and simulating the improved IoT-WHRS architecture. The experimental validation demonstrates that the enhancements achieve superior efficiency and better performance compared to the earlier design.

The paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 introduces the key benefits of predictive maintenance for Industry 4.0. The architecture of the improved IoT-WHRS for IoT applications, the modelling methodology of the IoT-WHRS and the finite difference model are detailed in section 3. The detailed hardware architecture is introduced in section 4. Simulation and experimental results as well as the final installation of the pilot in the CEPSA oil refinery are discussed in

Section 5.

Sections 6 presents the background and related work. Finally, the conclusions summarize this work and discuss future opportunities for IoT-WHRS.

2. Industrial IoT Application for Predictive Maintenance

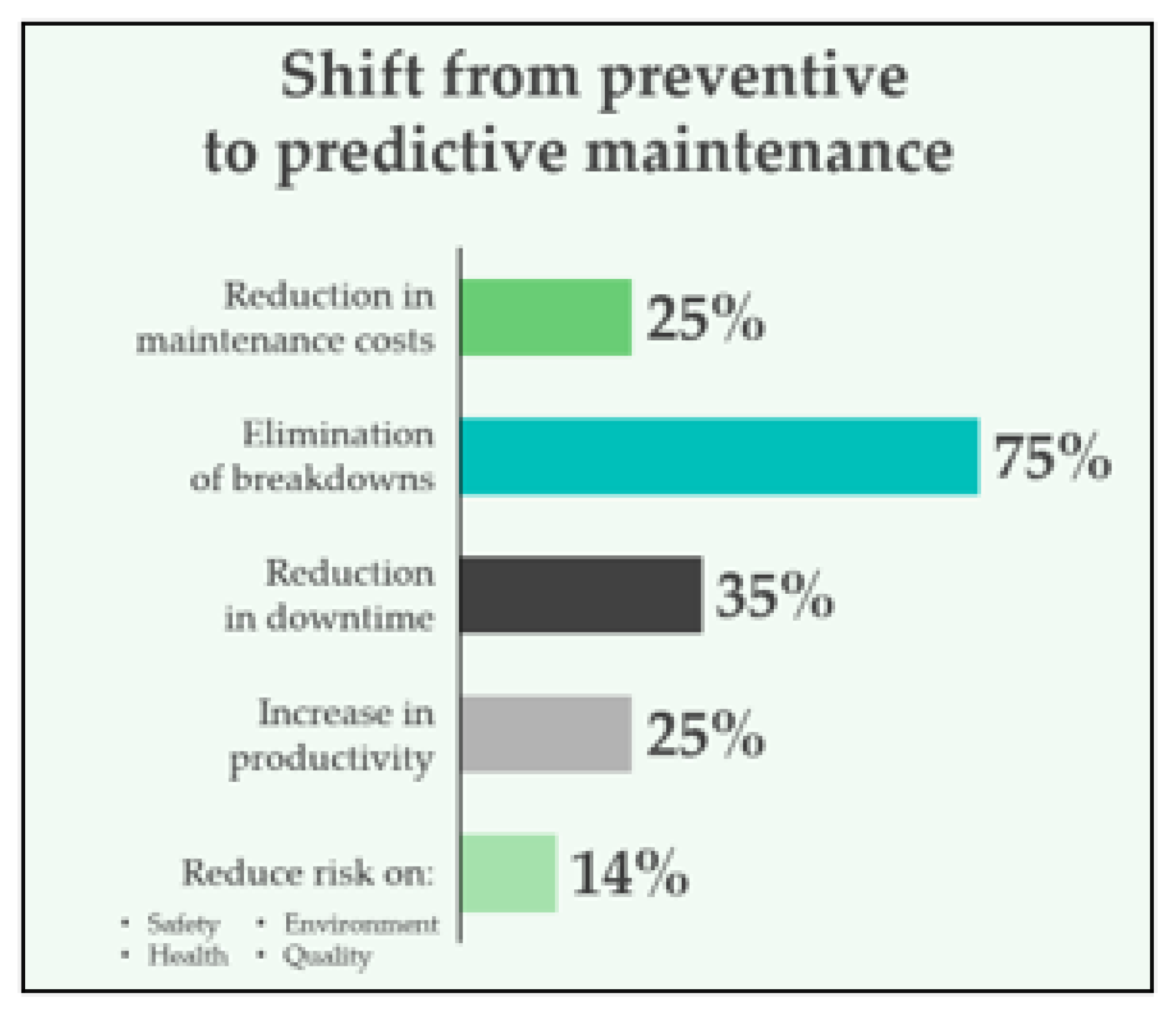

2.1. Main Benefits

Predictive maintenance has revolutionized the operation of electric machines by enabling early detection of potential failures, optimizing maintenance schedules, and minimizing unplanned downtime. One of its greatest advantages lies in its ability to extend machine life while reducing operational costs. In recent years, integrating predictive maintenance with IoT devices has further enhanced its effectiveness, particularly in industrial environments where energy efficiency and real-time data processing are critical. Benefits for industries are illustrated in

Figure 1.

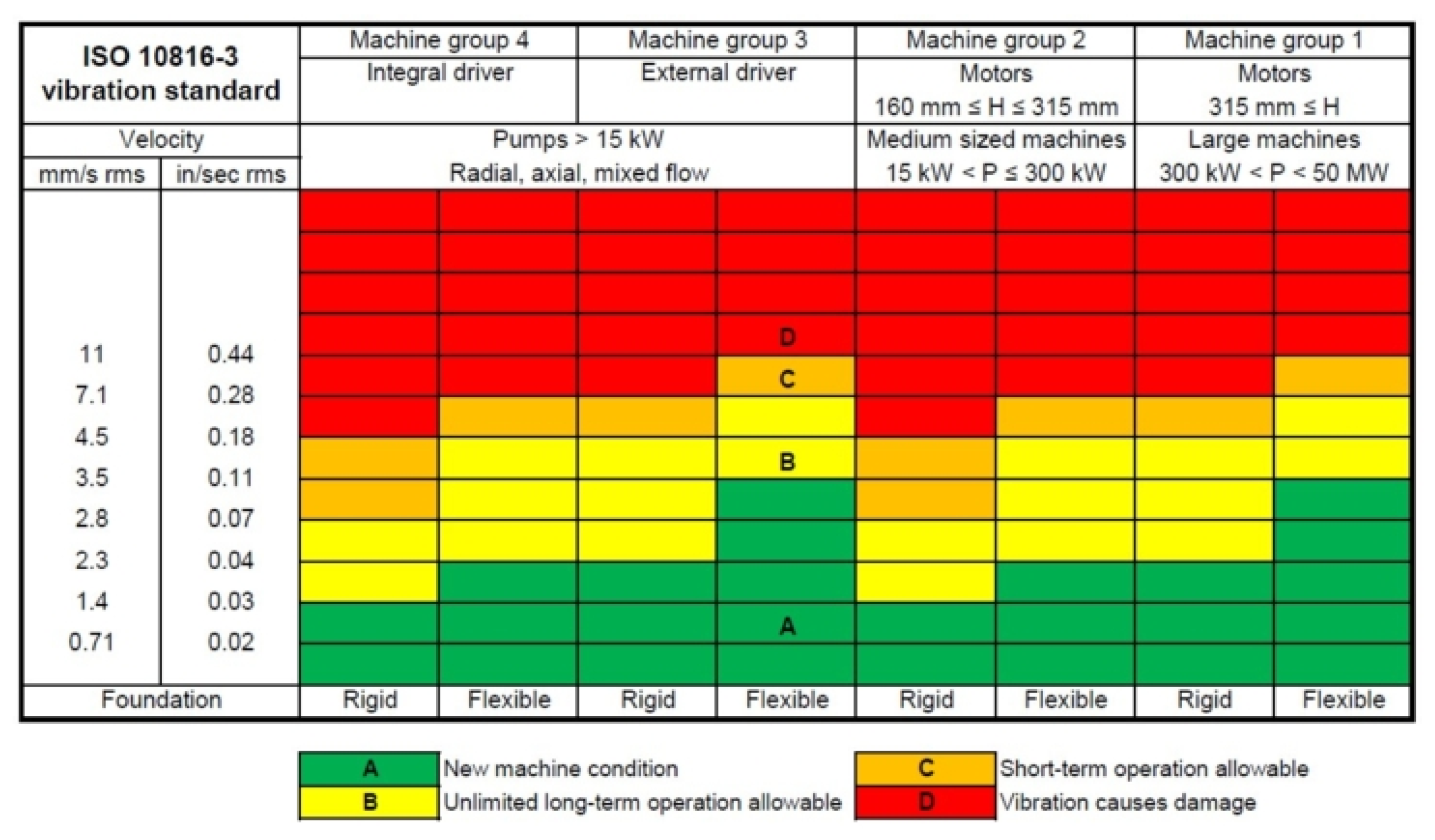

2.2. Velocity Measurement

A key component of predictive maintenance is vibration monitoring, which serves as a reliable indicator of a machine's health. Standards like ISO 10816 provide clear guidelines for evaluating the mechanical condition of rotating machinery by measuring vibration velocity in root mean square (RMS) values (mm/s). The standard categorizes machine condition into three distinct zones:

Green Zone: Normal operation, no intervention needed.

Yellow Zone: Warning level, maintenance should be scheduled.

Red Zone: Critical level, immediate action required to prevent failure.

These thresholds simplify the assessment of machine health and are commonly represented in predictive maintenance tools using a colour-coded system (

Figure 2), allowing maintenance teams to quickly interpret data and act proactively. By combining IoT-enabled devices with vibration monitoring standards like ISO 10816, industrial environments can achieve safer, more efficient, and cost-effective maintenance strategies.

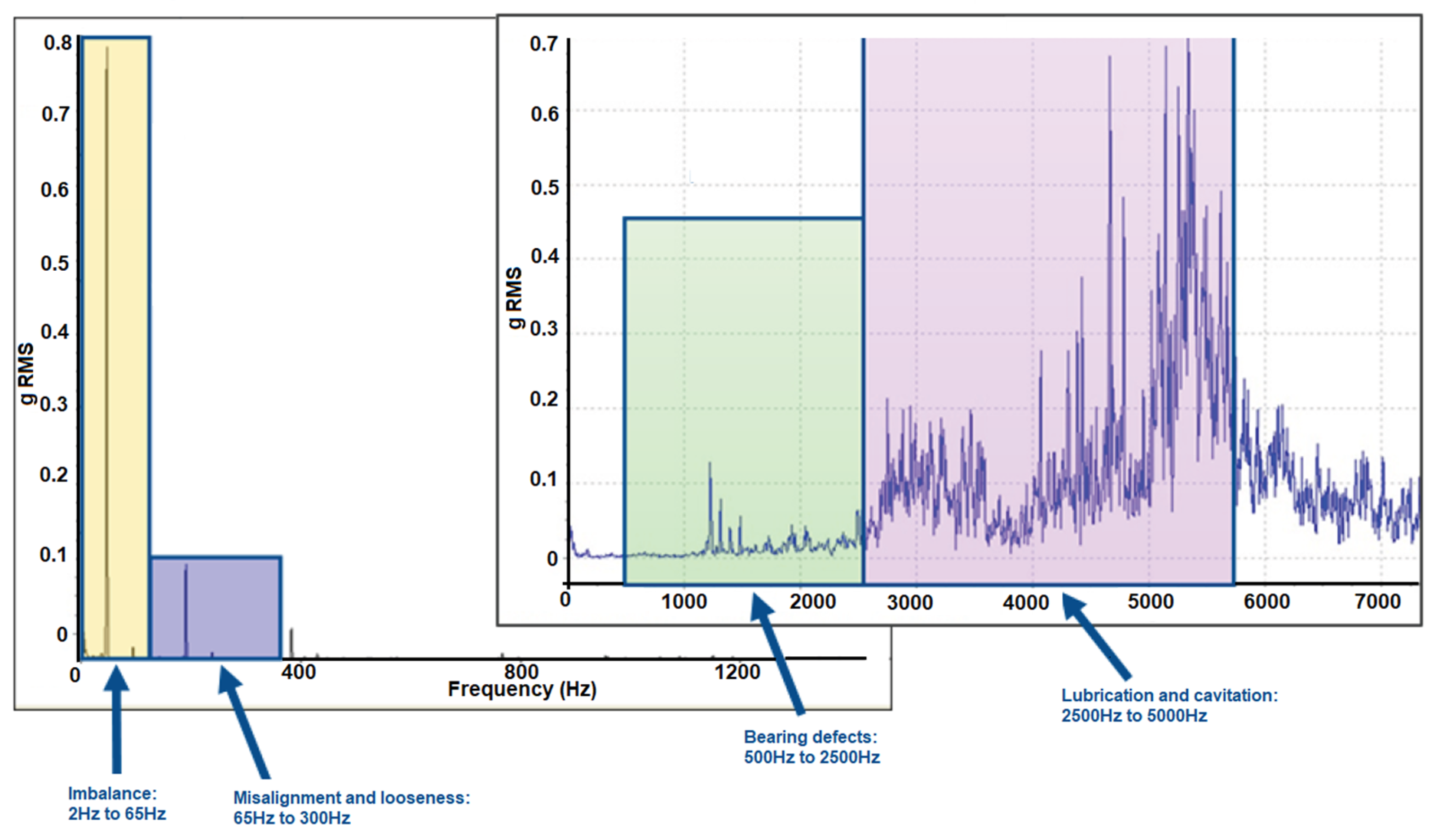

2.3 Spectral Analysis for Fault Diagnosis

While RMS vibration velocity (mm/s) provides an excellent overall indicator of machine health, incorporating spectral analysis offers a much deeper level for fault diagnosis. By analyzing vibration frequencies in the spectrum, it becomes possible to identify specific anomalies in the motor and determine their cause. This capability transforms the device into a powerful diagnostic tool, enabling targeted maintenance actions during scheduled downtimes, minimizing operational interruptions, and preventing catastrophic failures.

Vibration frequency analysis in Hertz (Hz) can reveal the signature patterns of various types of faults:

Imbalance: Detected at the rotational frequency of the motor (1× RPM or the fundamental frequency, typically from 2Ht to 65Hz).

Misalignment: Typically appears at 1× RPM and higher harmonics (e.g., 2× RPM, 3× RPM typically from 65Hz to 300Hz).

Bearing faults: Characterized by specific frequencies such as the Ball Pass Frequency Outer (BPFO), Ball Pass Frequency Inner (BPFI), or fundamental train frequency (FTF), which depend on the bearing geometry and rotational speed, typically from 500Hz to 2500Hz.

Lubrication and cavitation issues: Detects lack of lubrication in the gearboxes as well as air bubbles in the lubrication, typically from 2500Hz to 5000Hz.

By monitoring these specific frequencies, maintenance teams can pinpoint the origin of problems, such as an unbalanced rotor, misaligned shafts, or damaged bearings, allowing for swift corrective actions. The ability to measure and analyze vibration in both RMS velocity and spectral domains provides a comprehensive toolkit for ensuring the reliability and efficiency of industrial machinery.

In the figure

Figure 3.

Analysis spectrum of vibrations to determine potential malfunctions.

Figure 3.

Analysis spectrum of vibrations to determine potential malfunctions.

3. Heat-Powered IIoT Architecture

3.1 Introduction to IoT-WHRS Architecture

Low power consumption is a key requirement for IoT nodes deployed in predictive maintenance applications. These nodes often operate in environments with limited energy availability and experience bursts of high energy demand during data transmission. Thermoelectric energy harvesting systems (IoT-WHRS) have emerged as a sustainable solution for powering IoT nodes in such scenarios. These systems harvest energy from waste heat in facilities, storing it in energy buffers for efficient use during data acquisition, processing, and communication cycles.

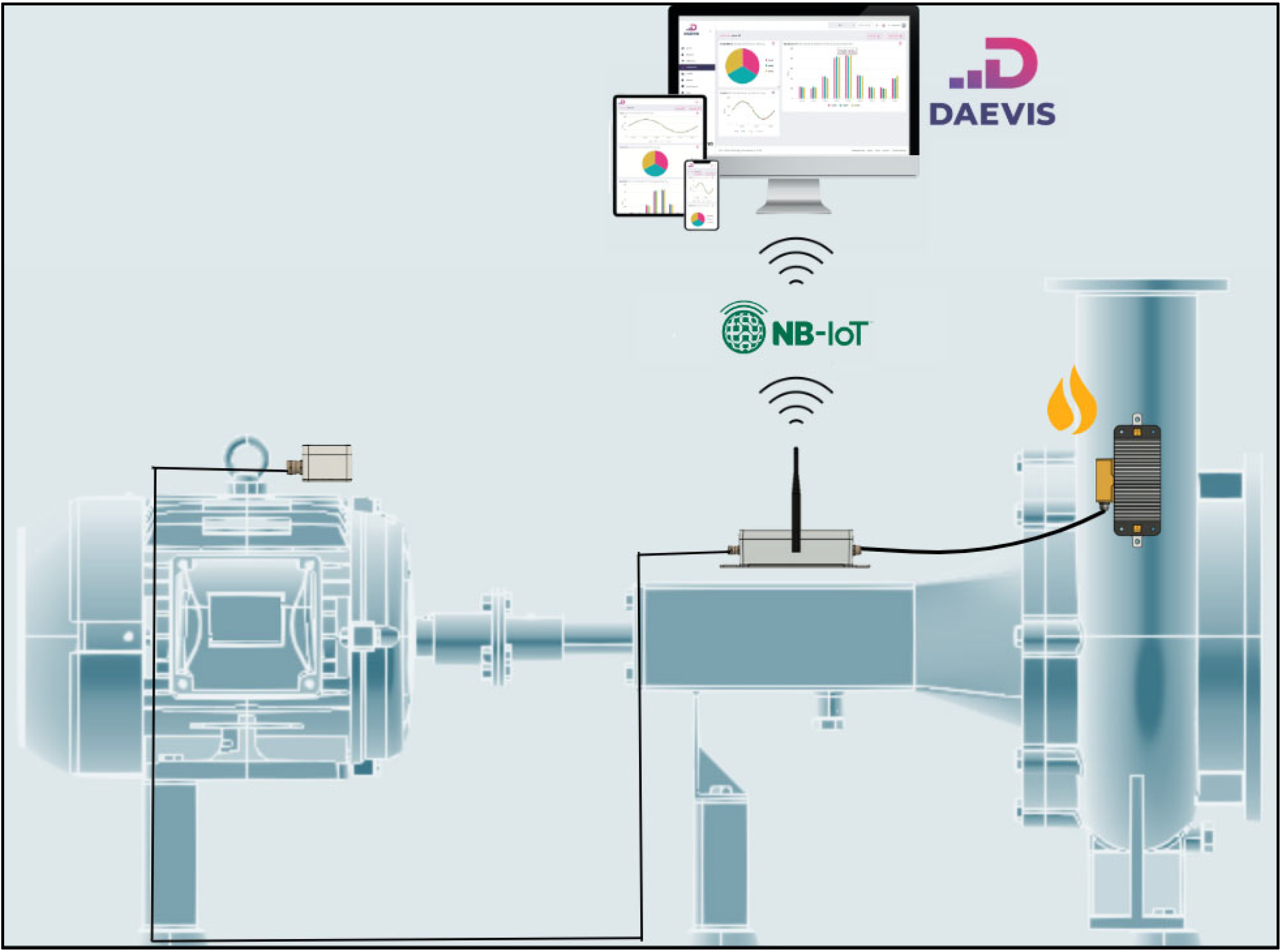

Figure 4 illustrates the architecture of a wireless IoT node powered by an energy harvesting system. The data acquisition collects information through smart sensors installed over the electric machine (left), processes it, and transmits it to a using NB-IoT communication protocol (centre). Meanwhile, the energy harvesting device (right) consists of components that harvest, rectify, regulate, and store the harvested energy, ensuring the node is powered only when necessary. Finally, all data is represented in a visualizer, typically in a cloud platform (top). In our case, this cloud platform is named DAEVIS (Dynamic AEInnova Visualizer) running on AWS. AEInnova is a company founded by the authors 10 years ago.

3.2. IoT-WHRS Model Parametrization

Thermoelectric energy harvesting systems must overcome several challenges to achieve high efficiency. Maintaining a significant temperature difference between the hot and cold sides of the thermoelectric generator (TEG) is essential for maximizing power output. The efficiency of the IoT-WHRS is influenced by the thermal resistance between the TEG, heat collector, and heatsink, as well as the presence of air gaps created by clamping mechanisms. These air gaps act as resistive thermal paths, reducing the overall system efficiency.

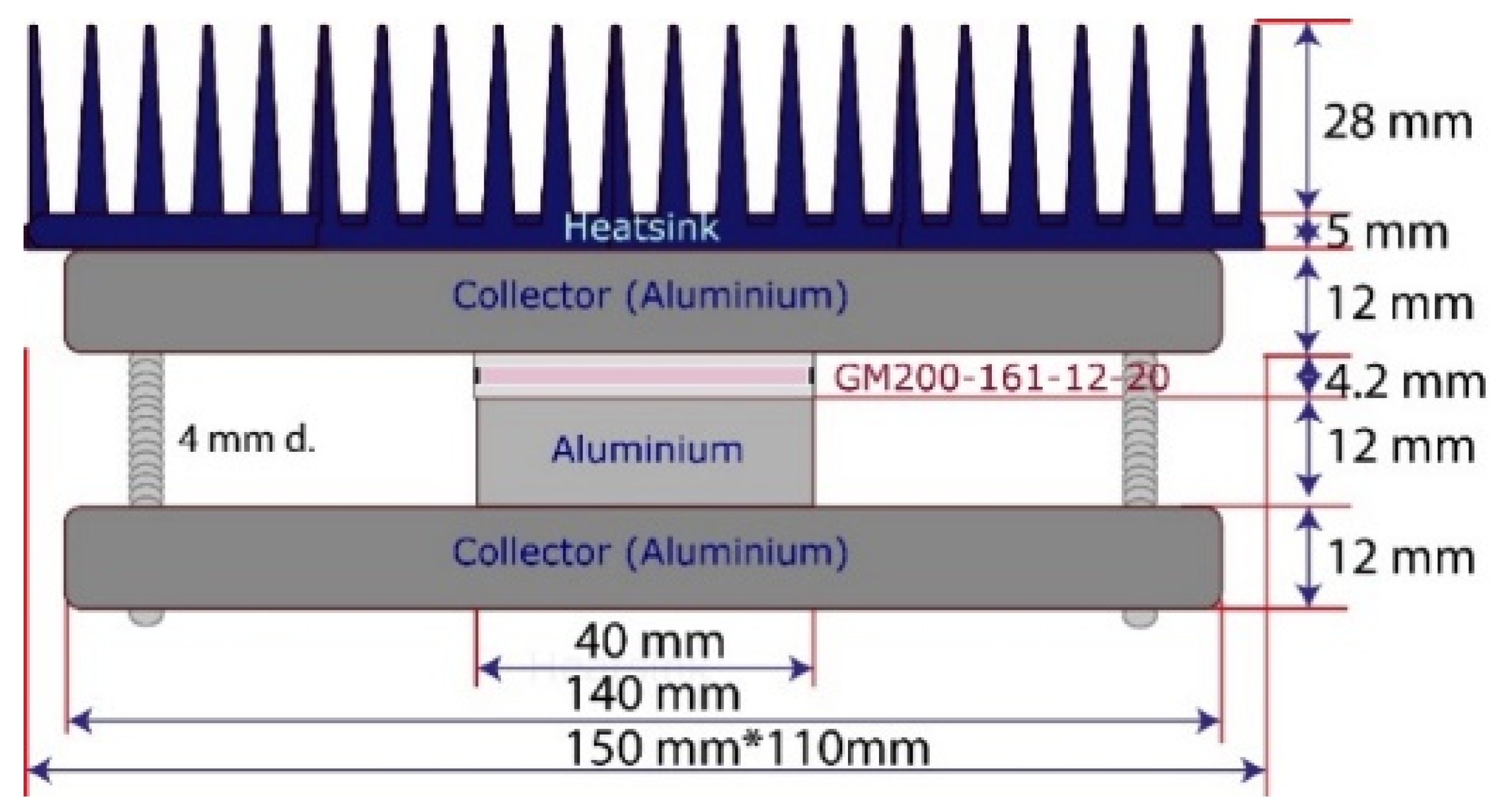

Figure 5 presents the IoT-WHRS architecture used in this study, comprising:

A GM200-161-12-20 Peltier cell acting as the TEG.

An aluminium plate serves as the heat transmitter between the aluminium collector and the TEG.

Finally, the system is fastened between two pieces of aluminium Al6063-T5, corresponding to the collector and the base of the heatsink, which is attached to an Al6063-T5 heatsink base. This optimized design allows the IoT-WHRS to harness energy efficiently from waste heat.

The power generation of the IoT-WHRS (Waste Heat Recovery System) is determined by the thermoelectric generator (TEG) and depends on the system's architecture and materials. The thermal performance is modelled through thermal resistances and capacities, influenced by the physical properties of the materials used, such as density, thermal conductivity, and specific heat, which are summarized in Table I.

Key factors include:

Thermal Properties of Materials: Materials like copper, aluminium alloys (Al6063-T5), alumina, graphite, and mica contribute differently to heat transfer. Copper offers the highest thermal conductivity, while air is modelled as an ideal gas due to its low density.

Contact Resistance: Microhardness and surface roughness influence the contact resistance between materials, affecting heat transfer efficiency [

18]. Air gaps caused by surface irregularities can increase resistance, reducing performance.

TEG Model: The TEG's performance is modelled using an "effective parameter model" due to limited manufacturer specifications, incorporating properties of its pellets, ceramics, and welds.

Heatsink Efficiency: The heatsink’s fins dissipate heat to the environment, while the base transfers heat from the TEG. The material and geometry of the fins are crucial for cooling performance [

19].

In summary, the IoT-WHRS system's efficiency depends on minimizing thermal resistance through material optimization and precise control of contact interfaces, ensuring effective heat capture and dissipation.

Table 1.

IoT-WHRS Materials Properties.

Table 1.

IoT-WHRS Materials Properties.

| |

Units |

Air (*) |

Al6063-T5 |

Graphite |

| Density |

ρ, (Kg/m3) |

1.1839 |

2700 |

1800 |

| Thermal conductivity |

K, (W/(mK)) |

0.0261 |

209 |

5 |

| Specific heat |

Cp, (J/(kgK)) |

1,004.3 |

896 |

895 |

| Micro-hardness (**)

|

μH, (MPa) |

|

670 |

100 |

| Surface roughness (**)

|

sR, (μm) |

|

1.8 |

2.0 |

3.3 Thermal Modeling of IoT-WHRS

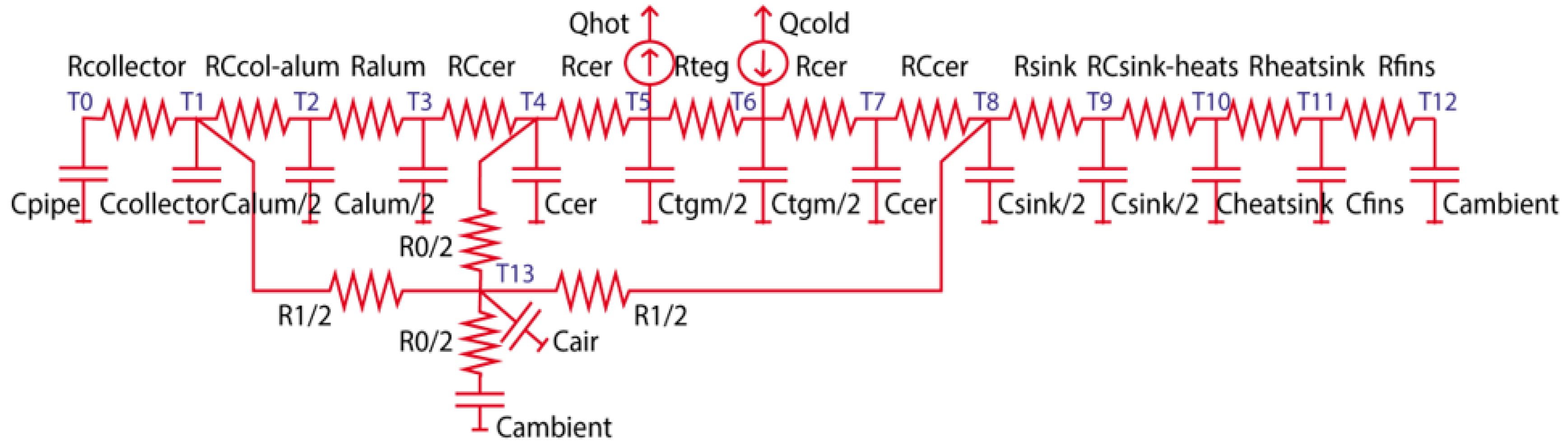

Figure 6 illustrates the thermal resistances and capacitances that play a central role in the IoT-WHRS model. Each component in the system contributes to heat transfer by acting as a thermally resistive element.

The heat storage capacity of the materials is determined by their specific heat, while the thermal resistance and capacitance of the air gap are integral to the system's overall performance. The IoT-WHRS establishes two distinct heat transfer pathways: one through the elements surrounding the TEG and another across the air channel. Key contributors to heat flow and distribution include:

Collector and heatsinks: Constructed from aluminum to optimize heat conduction.

Thermoelectric generator (TEG): Encompasses the thermoelectric effect, ceramic plates, and welds connecting these plates. Heat rejection and absorption are represented by Qhot and Qcold, respectively.

Heatsink and its fins: Responsible for dissipating heat into the surrounding environment.

Contact interfaces: Points of interaction between components introduce thermal resistance that impedes heat transfer.

Airgap volume: Acts as a thermal barrier, contributing to the overall resistance within the system.

Additionally, the thermal circuit accounts for the TEG's dynamic behavior to refine model accuracy. The heat transfer mechanism in the IoT-WHRS is characterized by two distinct channels, as previously outlined, which work together to manage the heat flow efficiently.

3.3.1. Heat Transfer Contribution Via the TEG ChannelHeat transfer within the TEG channel involves contributions from multiple components. Following the models described in [13], the TEG's thermal behaviour accounts for the resistive and capacitive properties of its thermoelectric pellets represented as Rteg and Cteg. These parameters are temperature-dependent and must be recalculated dynamically during simulations. Surrounding the pellets are ceramic plates (made of alumina), which add their own thermal resistance (Rceramics and heat capacity (Cceramics), derived from the material’s conductivity, heat capacity, and geometry.

The interconnecting aluminium between the pellets is excluded from direct modelling because the effective parameter approach accounts for its contribution, as explained in Section IV.

The aluminium collector is modelled using its thermal resistance (Rcollector) and heat capacity (Ccollector), while the aluminium separator plate (positioned between the collector and the TEG) is represented by Ralum and Calum.

The heatsink requires a more intricate model. Its base and fins are treated as separate components. The base, similar to the collector plate, is modelled with R

heatsink and C

heatsink. Meanwhile, the fins, critical for heat dissipation, are represented by R

fins and C

fins as per the approach in [

16].

Heat flow originates in the hot surface, where it is collected by the aluminium plate, and dissipates into the environment via the heatsink. The machine's hot surface (where we are harvesting the heat) and the external environment are modelled as high-capacity thermal reservoirs (Cpipe and Cambient), effectively considered infinite in the simulation.

All RC

xxx resistances in the thermal circuit account for contact resistances, which are critical factors for accurate heat transfer modelling, as detailed in [

15].

3.3.2. Heat Transfer Contribution Via the TEG Channel

The airgap channel represents the air layer formed by the clamping mechanism that secures the TEG between the collector and the heatsink. This enclosed air volume significantly impacts the system's thermal performance by contributing to heat flow around the TEG. The air layer is confined by the collector and the aluminium heatsink base, which has high thermal resistivity.

To capture the thermal effects of the airgap, the model incorporates several thermal resistances and capacities:

R0: Represents the transverse heat transfer between the TEG and the surrounding environment.

R1: Models the thermal channel connecting the heatsink and the collector.

R2: Accounts for heat transfer between the insulator and the collector.

Cair1 and Cair2: Represent the heat storage capacities of the airgap channels.

This layered modelling approach ensures a more precise representation of heat propagation within the airgap and its interaction with the overall system.

3.4. TEG Effective Parameters Model

The efficiency of the IoT-WHRS system is strongly tied to the performance of the thermoelectric module, which converts thermal energy into electrical energy. The energy output of the TEG is driven by the interplay of key physical phenomena within the thermoelectric semiconductors: the Seebeck, Peltier, Thomson, and Joule effects, as summarized in

Table 2. To enhance energy production, the Seebeck effect must be maximized while minimizing heat transfer. Heat transfer within the TEG is predominantly influenced by its internal resistance, R

0, which impacts the overall efficiency, denoted by the maximum efficiency coefficient (η

max). The figure of merit (Z

T) is used to benchmark thermoelectric performance.

To simulate the TEG’s behaviour in the IoT-WHRS system, the thermoelectric properties—Seebeck coefficient (α), electrical conductivity (σ), and thermal conductivity (κ)—must be determined. However, these parameters are rarely provided by manufacturers. Instead, the model employs effective parameters (α

∗, κ

∗, ρ

∗, and ZT

∗) derived from the TEG’s datasheet specifications. This approach introduces minimal errors while providing sufficient accuracy for simulation purposes [

20]. As shown in

Table 3, the effective parameters are calculated using maximum power (W

max), open-circuit voltage (V

max), maximum current (I

max), and efficiency (η

max).

The number of thermocouples in the TEG module (n) is also incorporated. This study utilizes the Kryotherm GM200-161-12-20 module.

Table 4 presents its key specifications and the corresponding effective parameters calculated based on the equations listed in

Table 3.

3.5 IoT-WHRS Finite Difference Model

The IoT-WHRS simulation focuses on capturing the thermal energy flow from the hot pipe temperature to the cooler ambient temperature, with the thermoelectric module converting the captured heat into electrical energy. The system is modelled under the constraint that the electrical power generated is equal to the thermal energy difference between the hot (QH) and cold (QC) heat fluxes.

The heat transfer within the system is described by a set of partial differential equations that characterize the temperature distribution across the components. As heat generation in the TEG varies with temperature, the system exhibits non-linear behaviour. Solving these non-linear equations analytically is impractical, so the system is discretized using finite difference equations [

5]. Starting with initial pipe (T

pipe) and ambient (T

ambient) temperatures, the system’s internal temperature evolution is computed iteratively.

The thermoelectric module’s power output is determined by the cold side temperature of the TEG and the temperature gradient across its surfaces. This numerical approach transforms the heat transfer equations into a discrete set of difference equations, as expressed in Equation (1). This iterative methodology allows for the simulation of temperature dynamics and power generation under varying conditions.

The subscripts

a and

b correspond to adjacent nodes connected through the thermal resistance R

a,b. In this formulation (as shown in the models of

Figure 6), T represents the current temperature at a node, while T′ is the temperature to be determined in the current time step (δt) iteration. Ra,b denotes the thermal resistance between the two nodes, C

a is the thermal capacity assigned to the node, and Q

a˙ represents the heat generated at the node.

The matrix terms (depicted in Equation (1) by the expression in parentheses) are derived based on the thermal resistance and thermal capacity values defined by the model connections. For instance, in the IoT-WHRS model (

Figure 6), there are 14 nodes, leading to the creation of a 14x14 matrix, as shown in Equation (2).

Each entry in the matrix is determined by the connections defined in the model. For instance, the non-zero elements in the first two and last two rows of this matrix are calculated based on the thermal links shown in

Figure 6. These terms are derived directly from the relationships and interactions outlined in the figure.

In this equation, several terms depend on temperature and must be recalculated at each simulation step. During each iteration, the finite difference system solves for the current temperatures, requiring the inversion of the state matrix—a computationally intensive task. Additionally, all temperature-dependent parameters must be updated at every step, including the thermal resistance of the fins, the resistances and capacities of the airgap, the thermal resistance of the contacts, and the heat transfer within the TEG.

4. Edge Computing for Battery-less Device with NB-IoT

This section outlines the development of an innovative wireless IIoT edge device powered by energy harvesting, which eliminates the need for batteries. By incorporating NB-IoT communication and real-time edge-computing capabilities, this device addresses key limitations in industrial monitoring and predictive maintenance applications.

4.1. Eliminating Batteries: A New Paradigm for IIoT Monitoring

IIoT devices typically require 30–150 mW of power, which is traditionally supplied by lithium batteries. However, batteries face significant challenges in industrial environments, especially in compact devices where limited space reduces energy storage capacity, shortening the operational lifespan of IoT nodes to just a few months or years depending on data acquisition frequency. This leads to recurring costs for replacement and maintenance, logistical difficulties, and environmental concerns. These issues are aggravated in large-scale industrial facilities and hazardous environments (e.g., EX/ATEX zones), where lithium batteries are prohibited due to safety regulations. As a result, these limitations have historically impeded the adoption of wireless IIoT technology for critical applications like vibration monitoring and predictive maintenance.

To address these challenges, the thermoelectric energy-harvesting device developed in this work has been sized for powering high-energy sensors and advanced computing processes without relying on batteries. Thermoelectric generators (TEGs) provide a continuous and sustainable power supply, enabling high-frequency data acquisition, real-time edge computing, and long-range wireless communication.

4.2 Overcoming Technological Barriers for Wireless IIoT

Industrial monitoring systems often require real-time data acquisition and processing, secure communication protocols, and minimal reliance on third-party systems. These demands place significant constraints on battery-powered IoT devices, which are further affected by the Battery storage capacity (mAh), the environmental conditions, such as temperature and humidity and Component power consumption, including:

Efficiency of DC/DC converters.

-

Processor operations, such as:

- ▪

Operational frequency (MHz).

- ▪

Power-saving modes (e.g., sleep, ultra-sleep).

- ▪

Edge-computing algorithms and firmware optimization.

Sensor power requirements and signal conditioning electronics.

Wireless communication protocol energy usage.

By leveraging energy harvesting, the proposed IIoT device overcomes these barriers, supporting:

Edge-computing capabilities for advanced data processing, including FFT, filtering, and ML / DL algorithms.

Continuous operation in hazardous environments (ATEX) without requiring battery replacements.

Data transmission at high throughput rates of up to 256 Kbps.

4.3 NB-IoT: The Optimal Protocol for Industrial Applications

Selecting the appropriate wireless protocol is a critical decision for industrial wireless sensor networks, as it directly affects node energy consumption, communication range, network scalability, and security. For edge-computing IIoT devices, the protocol must also support robust communication in challenging industrial environments while maintaining low latency and high data throughput.

Among Low-Power Wide-Area Network (LPWAN) protocols, Narrowband IoT (NB-IoT) stands out as an ideal solution for energy-efficient, long-range communication. According to studies by 3GPP, GSMA, and Kais et al. [

24], NB-IoT offers significant advantages for industrial applications, including the scalability (large numbers of devices can connect to a single gateway), low latency (ensures real-time monitoring and data transmission), the data security (encrypted communication for critical applications) and the cost efficiency (operates on licensed frequency bands, ensuring reliability and reduced interference).

In this work, NB-IoT is integrated into the energy-harvesting IIoT device to provide a secure and efficient communication protocol for industrial applications. For example, in the oil and gas sector, the system has been successfully deployed for vibration monitoring and predictive maintenance in high-risk environments. The integration of NB-IoT enables robust and reliable data transmission across large facilities, reducing infrastructure costs and enhancing operational safety.

4.4 Internal Architecture of the Edge-Computing Node

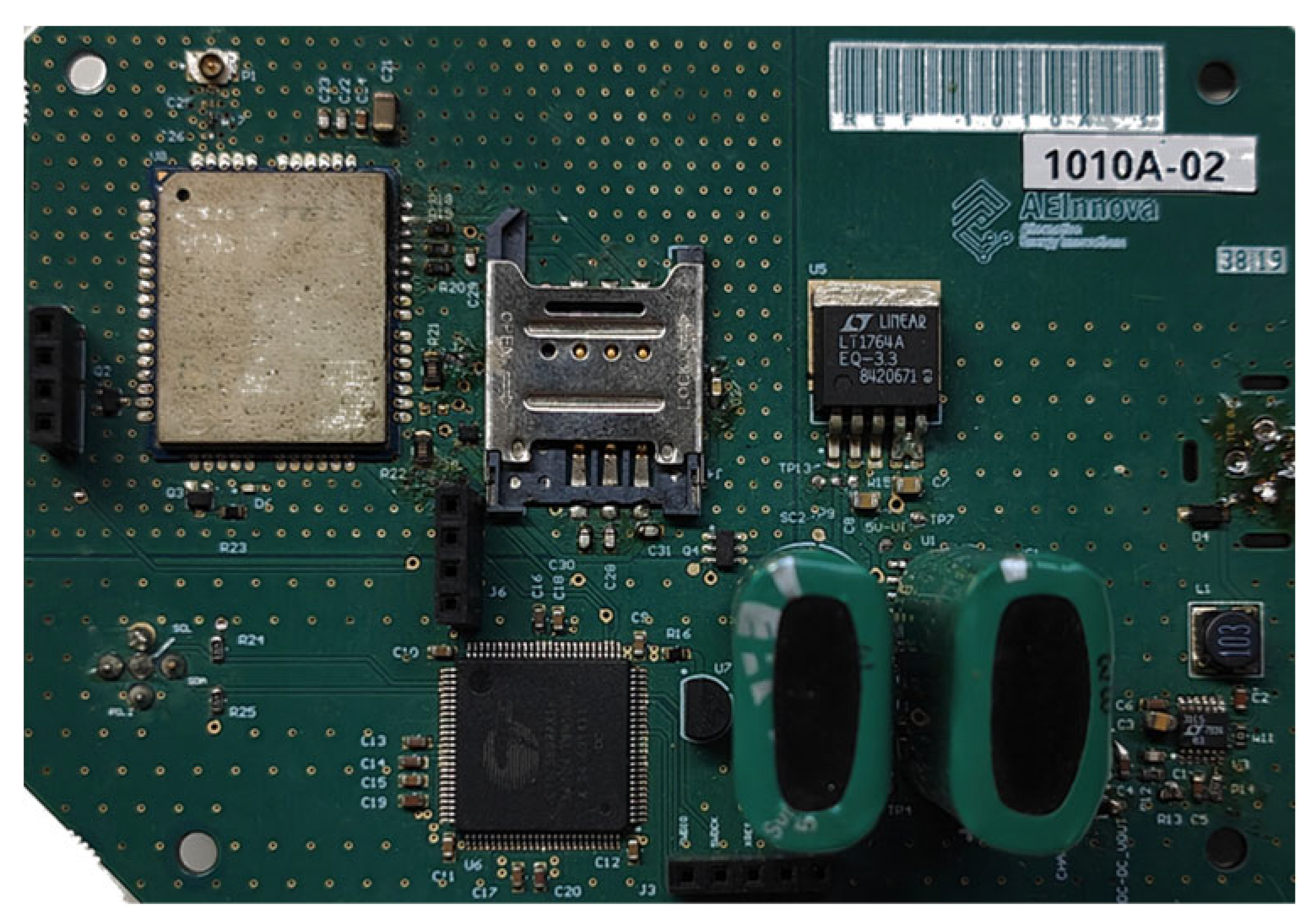

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 show the internal architecture of the NB-IoT sensing node, which is composed of the following key components:

Communications Hardware: Includes a 5 dBi antenna, the Quectel BG96 NB-IoT UART module, and a SIM card for wireless connectivity (from Vodafone).

Power Electronics: Comprises a DC/DC converter with MPPT to supply power to the external sensor, an energy buffer for alternative energy sources, energy management circuitry, and an SPI bus interface connected to an internal 3-axis vibration IMU (Inertial Measurement Unit) from STMicroelectronics.

Programmable Cortex M3 (32-bit processor), integrated Flash and RAM memory, analog and digital FPGA capabilities, and communication interfaces such as digital communication buses.

This modular architecture enables efficient sensing, processing, and communication for industrial IoT applications.

4.5 Data Acquisition, Processing, and Communication Flow

To calculate data latency and size the energy buffer, it is essential to first determine the total energy harvested to meet the system’s energy requirements. Data latency depends on the power generated by the thermoelectric unit and the energy consumed by the edge-computing algorithm, assuming up to one data package is transmitted per minute at 150°C.

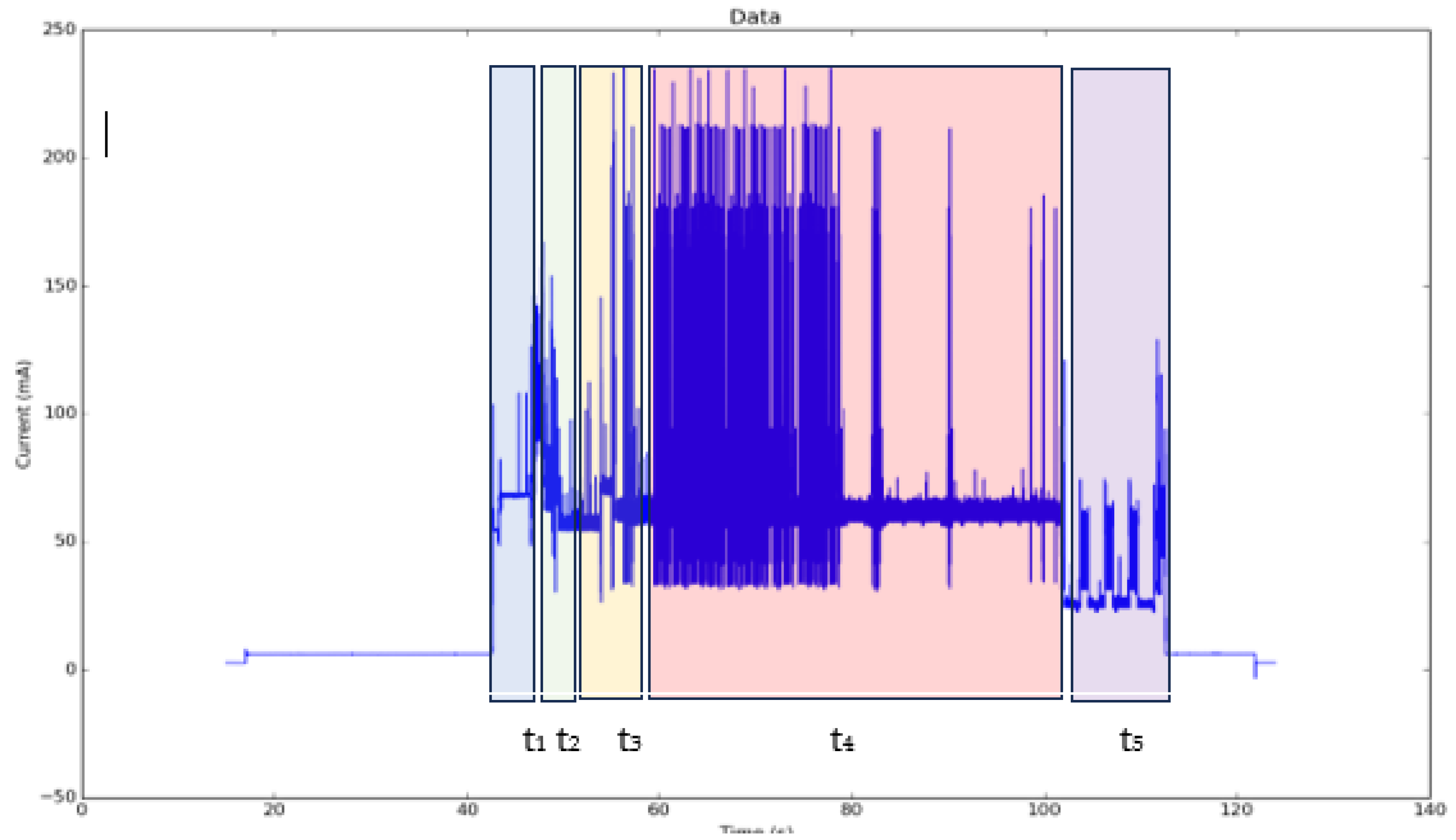

The process is divided into five-time slots or operational states, each with a specific duration and power consumption. These factors collectively determine the energy cost of each state, as illustrated in Figure 13 and detailed in subsection 5.2.

5. Results

5.1 WHRU Characterization

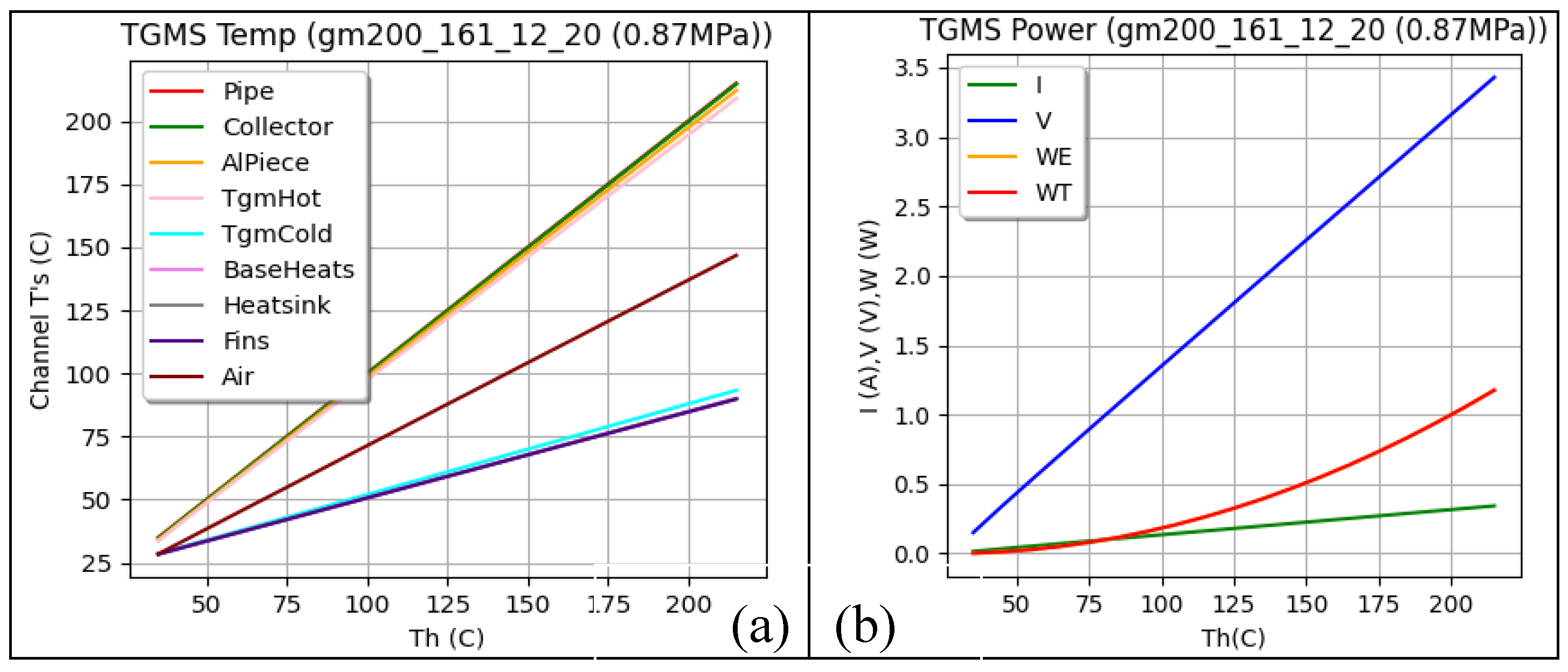

5.1.1 Simulation Results

Table 5 presents the setup parameters for the IoT-WHRS simulation, which correspond to the configuration of the devices under test. R

load represents the external electrical resistance coupled to the system, matching the internal electrical resistance of the thermoelectric device to achieve maximum power output. Torque, force, and screw diameter define the mechanical fixing parameters that secure the thermoelectric device to the collector and heatsink.

The model parameters of IoT-WHRS system are derived from the physical characteristics of the components used (

Figure 5) and the material properties listed in Table I. Contact resistances and fin dissipation capacities are calculated based on references [

15,

16], respectively.

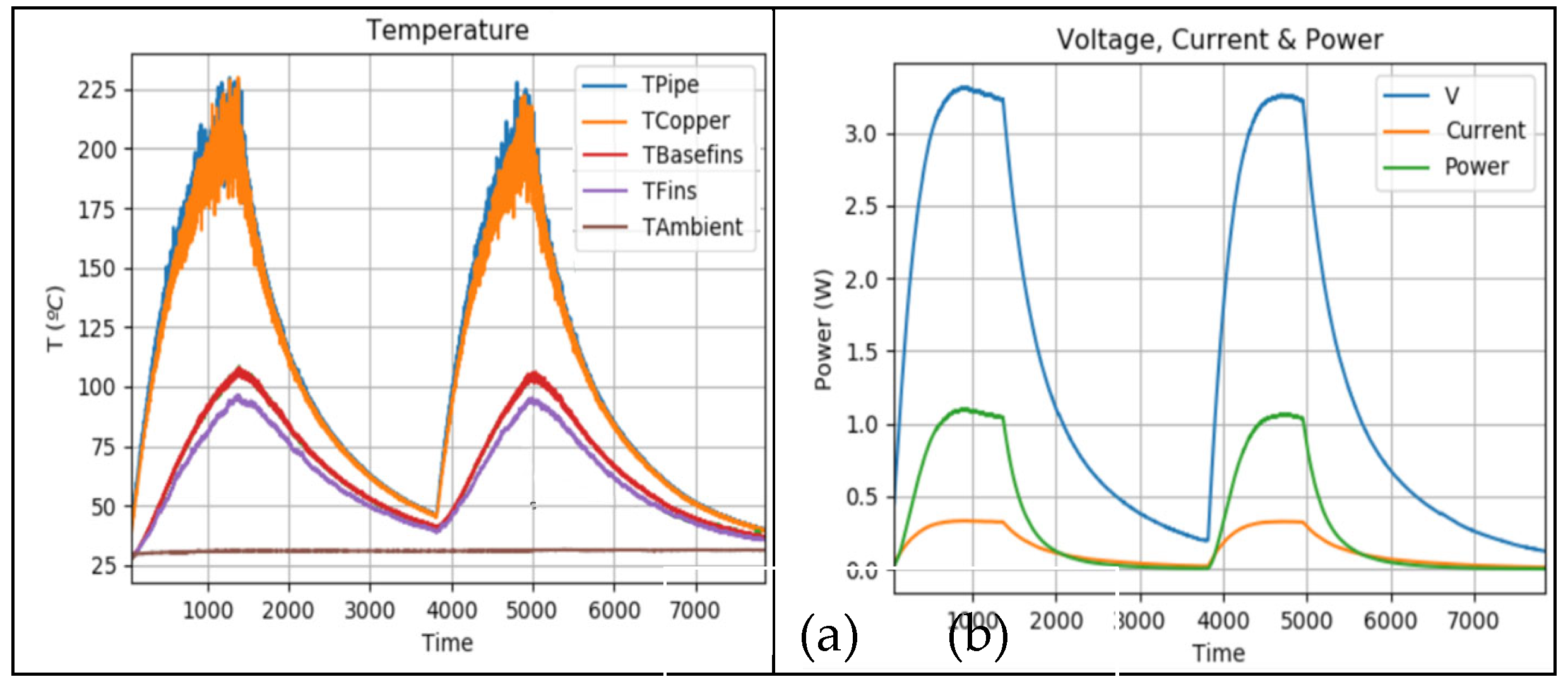

Figure 7 shows the results of a simulation of the IoT-WHRS. The left figure (a)illustrates the temperature evolution, and the right (b) depicts the power output of the systems. The simulation spans a Thot range from 25 ºC to 225 ºC, while Tcold is maintained at 25 ºC. As expected, the thermal power harvested (WT) matches the electrical power generated (WE). The power output of the two IoT-WHRS architectures is comparable.

Figure 9.

(a) Results of the IoT-WHRs simulation, (b) Power supplied by the system

Figure 9.

(a) Results of the IoT-WHRs simulation, (b) Power supplied by the system

5.1.2 Experimental results

The device was tested across a temperature range from room temperature to 200 ºC. The temperature and power evolution of the system were recorded using temperature sensors placed inside the module. The parameters were maintained as specified in the simulation (

Table 5).

The test was conducted by heating the collector of IoT-WHRS system. During each experiment, the collector was heated until its temperature stabilized at approximately 200 ºC (

Figure 10), after which it was allowed to cool back to room temperature. 5 heating and cooling cycles were performed during each experiment. On average, one hour was required for the heating phase and another hour for the cooling phase. Temperature measurements were taken every second at specific locations within the system. In the graphs, Tpipe represents the temperature of the collector, Tcopper corresponds to the copper separator, Theatsink represents the base of the heatsink, Tbasefins is the temperature at the base of the heatsink fins, and Tfins refers to the tip of the fins. Additionally, room temperature was also measured.

The left plot illustrates the temperature variations during the heating and cooling cycles. At higher temperatures, the data shows greater dispersion due to the reduced sensitivity of thermistors in this range. The right plot displays the measured voltage, current, and power.

The experimental results align closely with the simulation outcomes. Similarly, the system’s power behaviour during the heating and cooling cycles is consistent. This is because the power generated depends on the temperature of the hot side and the temperature difference across the TEG.

5.1.3. Statistical results

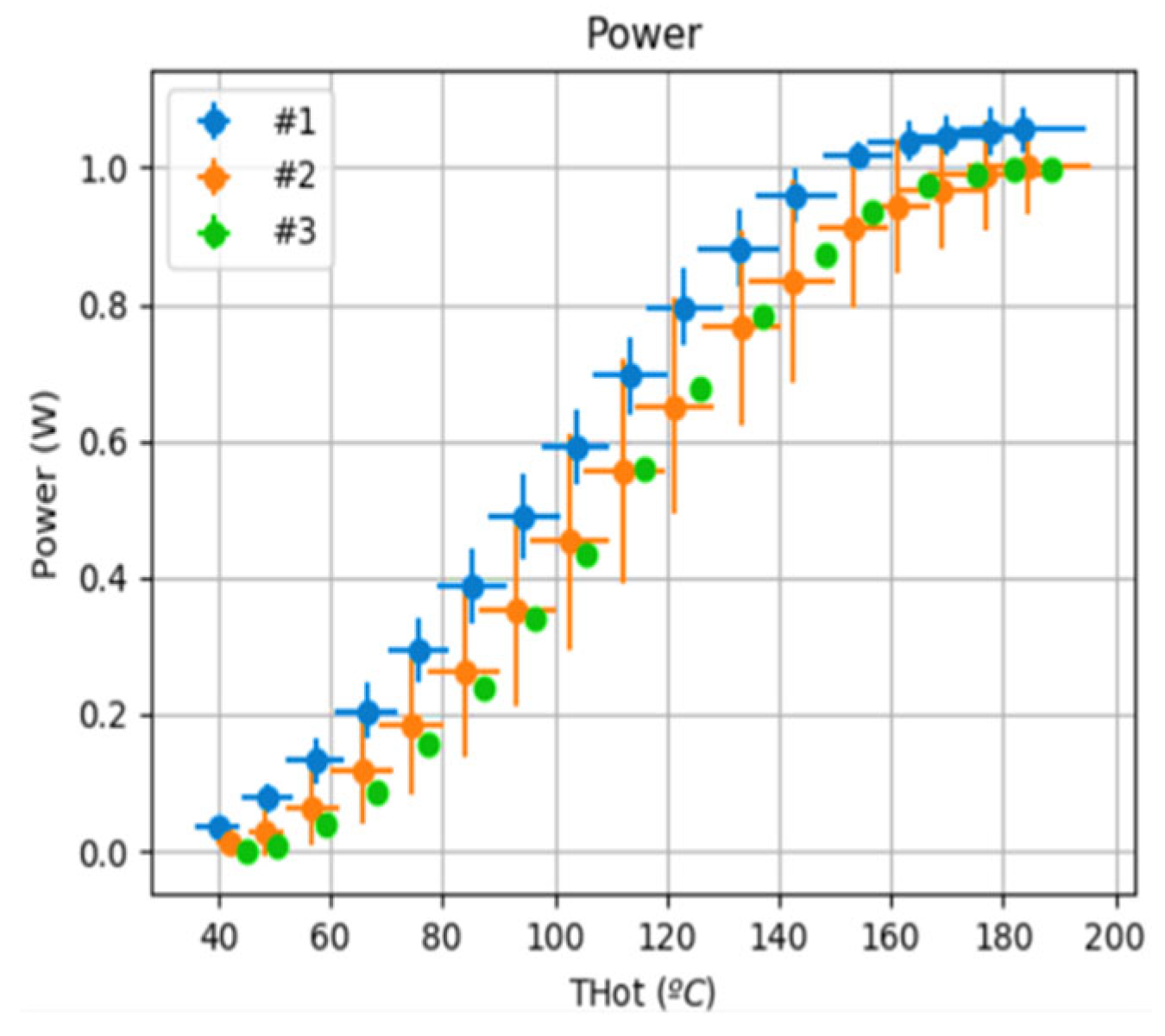

Several experiments are performed using three GM200-161-12-20 TEG cells to analyse the behaviour of the IoT-WHR systems (

Figure 11). A total of 21 tests with heating and cooling cycles is performed. The points represent the mean value and the crosses the variability. The figure shows the good behaviour of the cells in each IoT-WHRS. The power generated is similar for each thermoelectric cell, remaining inside the error bar.

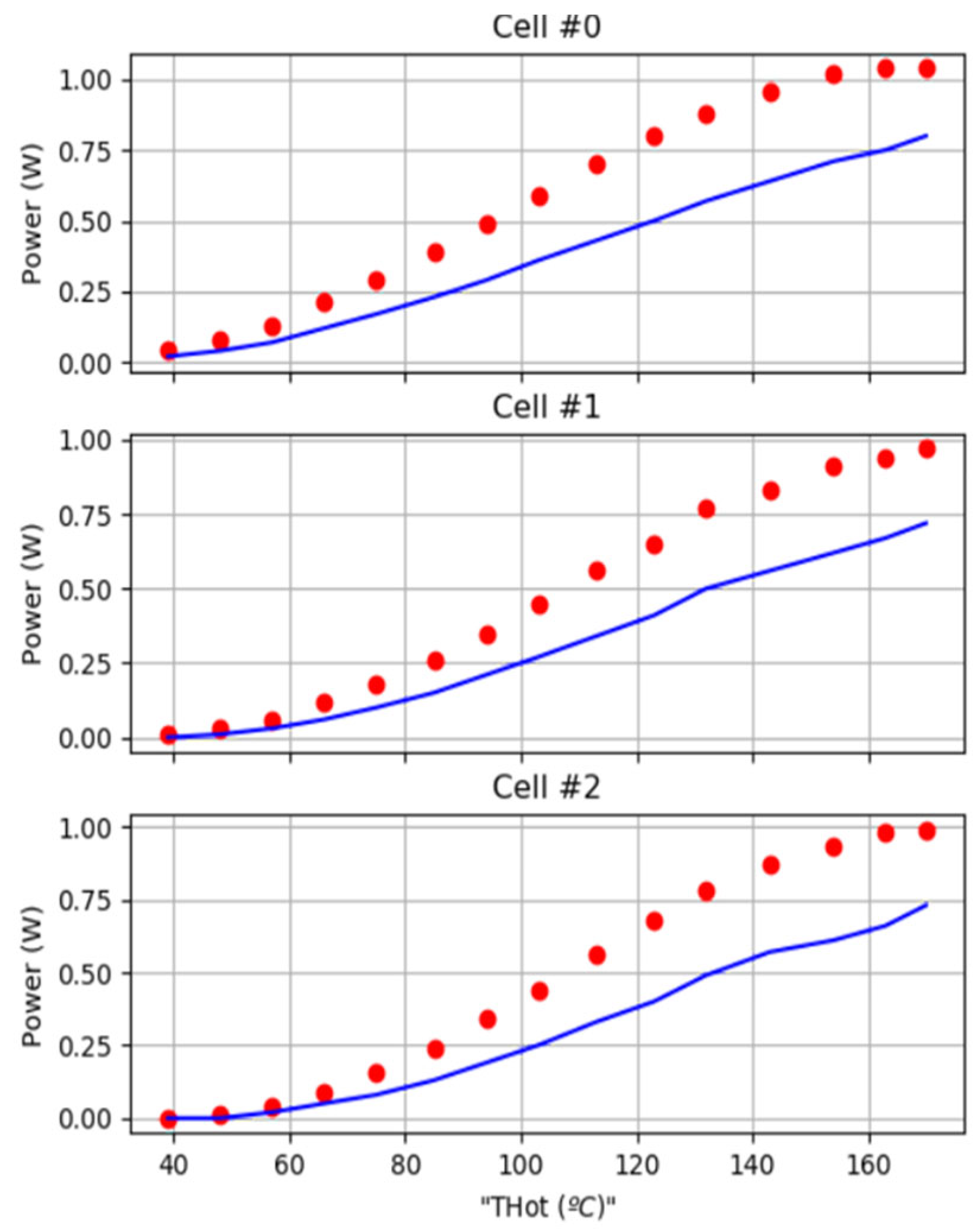

Figure 12 compares the experimental power output with the theoretical predictions as a function of the hot-side and cold-side temperatures. The experimental results exhibit a lower efficiency, ranging from 10% to 28% below the theoretical values. One contributing factor to this discrepancy is the use of the effective parameters model, which introduces an error of approximately 10% at average temperatures and is influenced by the cold-side temperature.

5.2 IIoT Node Power Characterization.

This subsection evaluates the power consumption of the IIoT node using the MQTT + TLS protocol for secure communication. MQTT + TLS is a lightweight publish-subscribe protocol secured with the Transport Layer Security (TLS) cryptographic protocol, which ensures communication security through x.509 authentication certificates.

Two experiments were conducted to assess the energy impact of MQTT + TLS, with the results shown in

Figure 13. In this figure, it is identified what are major process energy consumption demands:

T1. Wake-up.

T2. Data acquisition from the 3-axis vibration sensor.

T3. Data processing (velocity and spectrum).

T4. NB-IoT link and communication to the network.

T5. Data storage for postprocessing.

Comparisons were made between the NB-IoT and LTE-CATM1 communication protocols, both implemented within the Quectel BG96 chipset in

Table 6, where we observe a significant consumption increase in LTE-CATM1 versus NB-IoT. LTE-CATM1 offers higher speed and data capacity, but at the cost of increased energy consumption due to its wider bandwidth, higher processing complexity, and greater network activity. NB-IoT, being optimized for low-power devices and IoT applications, significantly reduces energy consumption by sacrificing speed and data capacity. This makes it ideal for applications where low energy consumption is more important than transmission performance.

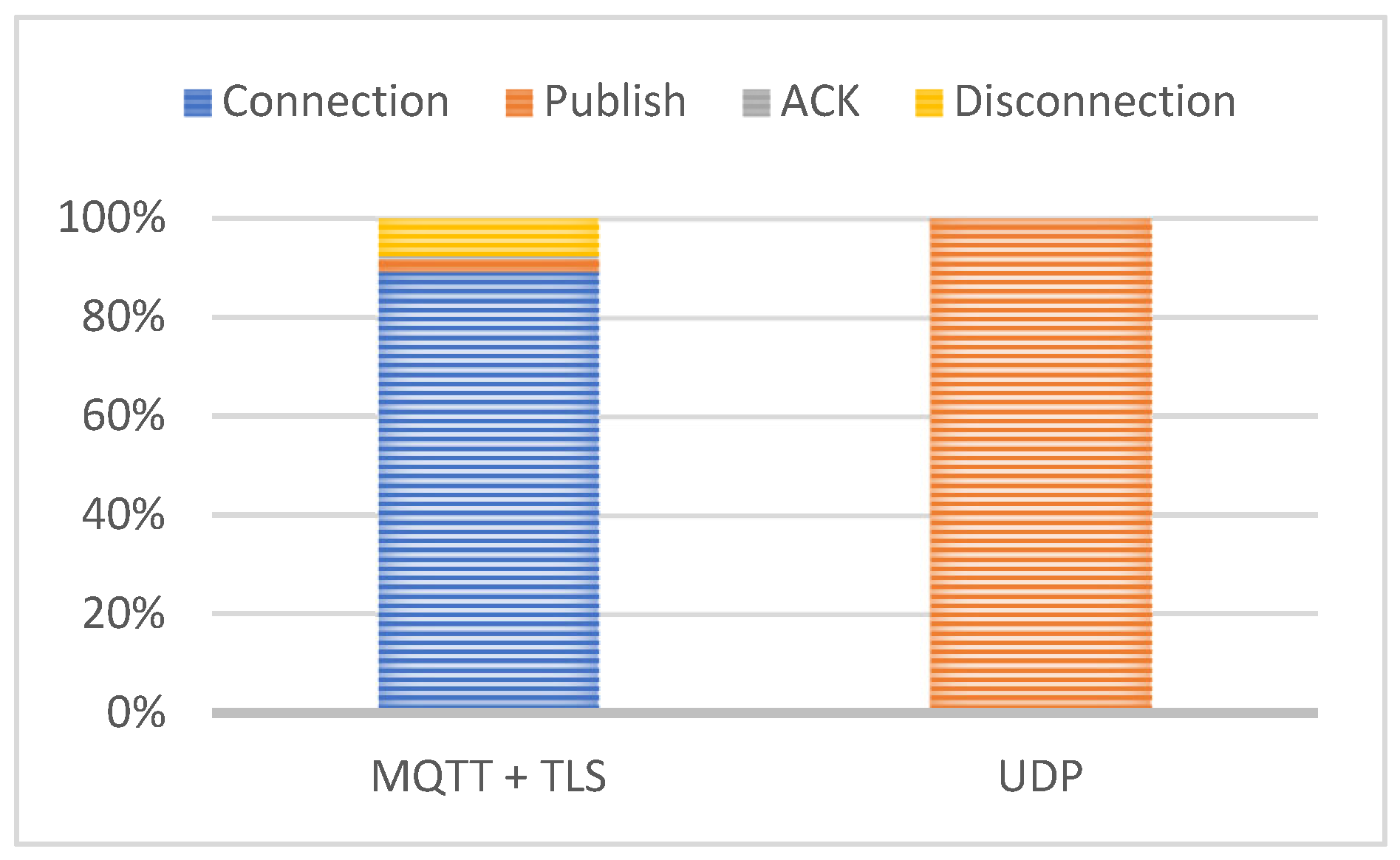

Additionally, the proportion of energy consumption for MQTT + TLS compared to UDP is shown in

Figure 14. The results demonstrate that MQTT + TLS, while providing robust security, incurs a higher energy cost compared to UDP due to the added cryptographic overhead.

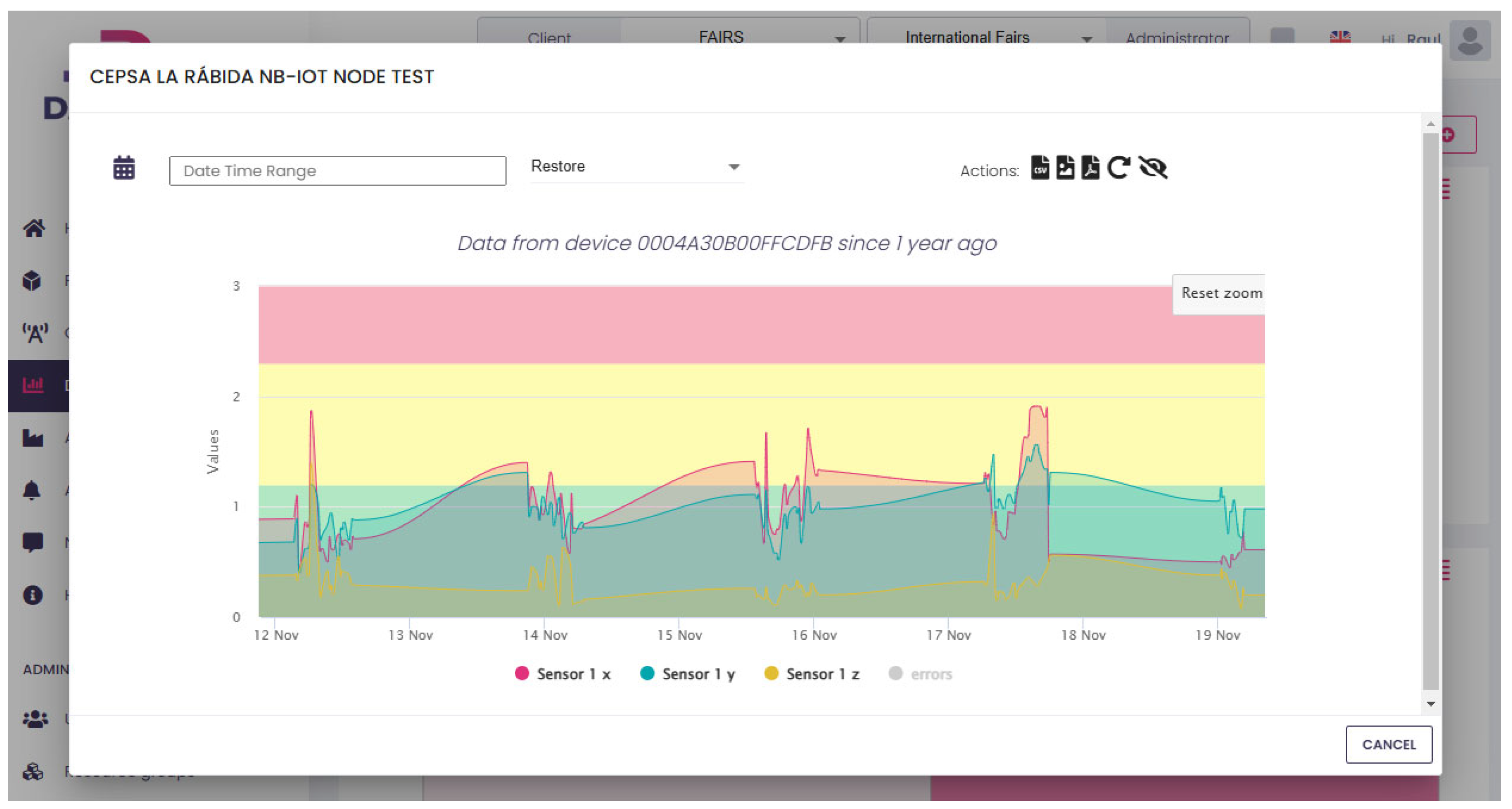

5.3. Pilot Installation in a Hot Water Pump

This section presents the first results of the implementation. They were overseen entirely in AEInnova’s laboratory, a spin-off of the Microelectronics Department at the Autonomous University of Barcelona. Subsequently, the device will be tested under real-world conditions at CEPSA La Rábida refinery in Spain. The complete system has been deployed to monitor vibrations in a hot water pump of CEPSA. In

Figure 15, the thermoelectric generator harvests heat from a central water pipeline (top), where the water temperature is maintained at 80 ºC. The generated energy is transferred to the NB-IoT node located on the left side of the setup, enabling data transmission. The node collects data from the 3-axis vibration sensor, which is positioned at the bottom of the installation.

Vibration data is analyzed by converting measurements from the acceleration domain (g) to the velocity domain (RMS in mm/s), following the ISO 10816 standard for predictive maintenance [

21]. The analysis spans a frequency range of 1 Hz to 1000 Hz across three axis.

Figure 16 presents vibration monitoring data recorded over a 8-day period, focusing on critical vibrations in the water pump. The machine is classified as a Group 4 machine, with a rigid base mounted on the ground, and must accomplish to the ISO standard, which defines the following critical velocity ranges:

Green: Healthy machine: 0 mm/s to 1.2 mm/s

Yellow: Short-term operation allowable: 1.2 mm/s to 2.3 mm/s

Red: Machine damage likely: Above 2.3 mm/s

The figure highlights several periods during days 2, 3, and 4 where vibration levels significantly exceed the warning threshold of 2.3 mm/s in the Y-Axis and X-Axis. This indicates that the machine requires urgent maintenance to prevent severe or critical damage.

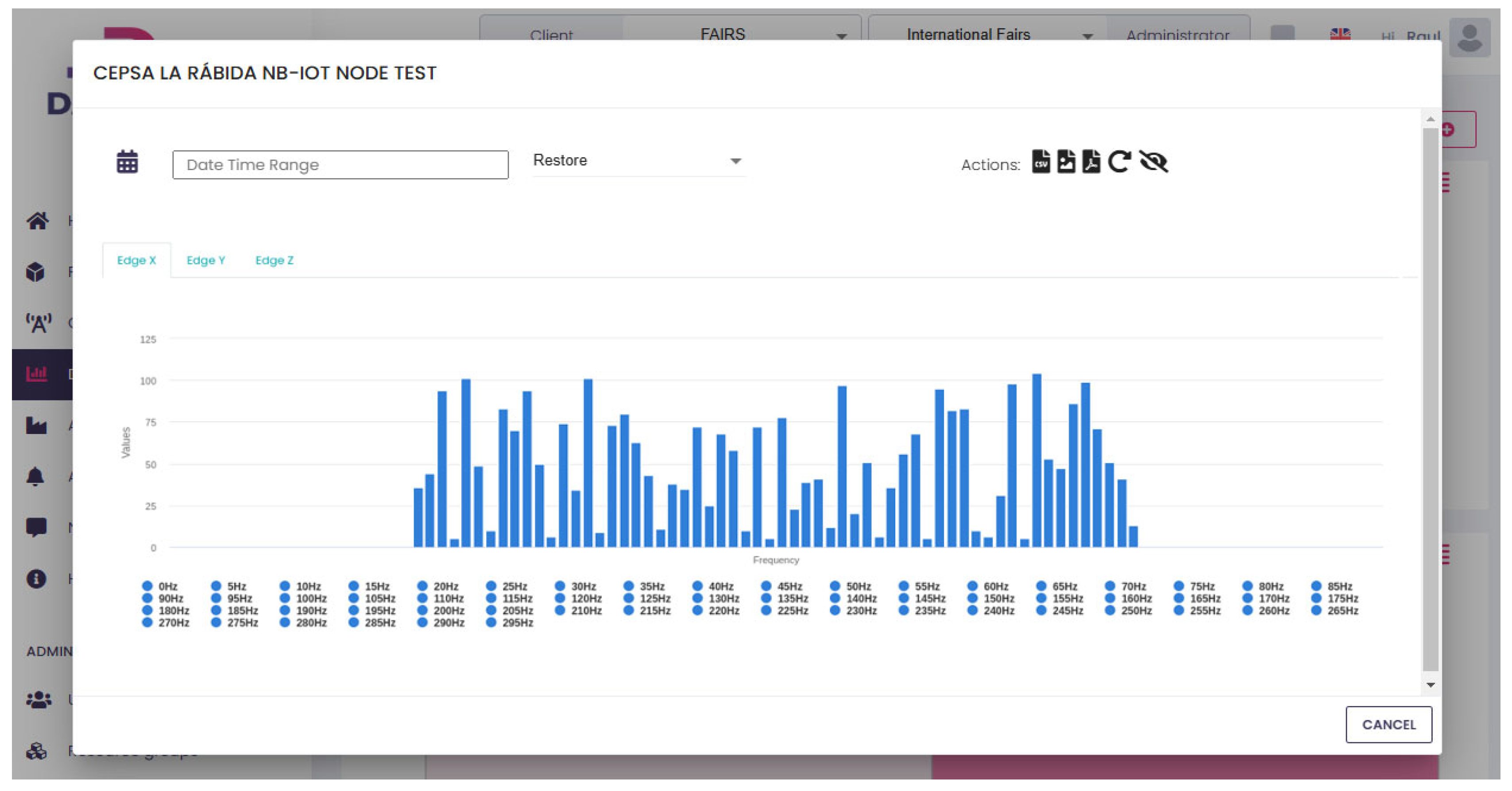

The spectrum analysis (

figure 17) reveals that the dominant frequency tones are mostly distributed below 300 Hz. This indicates that the issues affecting the hot water pump are likely related to imbalance and misalignment. These are common mechanical problems in rotating machinery and typically manifest as low-frequency vibrations within this range. Addressing these issues promptly is crucial to ensure the proper functioning and longevity of the pump.

6. Background and Related Work

To provide a comprehensive market analysis and assess the competitive landscape,

Table 2 compares existing vibration monitoring technologies with our proposed solution. This comparison includes leading manufacturers offering similar systems and evaluates key parameters such as technological approach, functional features, target industries, and communication protocols. Notably, our solution is the only vibration sensor on the market that utilizes the NB-IoT standard for communication. Competing devices primarily rely on battery-powered systems integrated with wireless communication protocols or on wired solutions (e.g., Modbus). However, due to the energy demands of the NB-IoT protocol, battery-powered devices cannot guarantee data transmission beyond one week of operation without frequent battery replacements or recharges.

Our technology differentiates itself through its innovative energy-harvesting system, which uses residual heat as a power source instead of traditional batteries. This approach not only eliminates the limitations of finite energy sources but also aligns with sustainability goals by reducing waste and environmental impact. Furthermore, the integration of NB-IoT for long-range wireless communication provides a significant advantage over traditional short-range systems like WirelessHART or propiertary wireless protocols, which require substantial investment in gateways and infrastructure.

By combining energy harvesting with long-range connectivity, our solution sets a new standard for industrial monitoring, offering a sustainable, cost-effective, and scalable alternative to conventional technologies.

Table 7.

Comparison of commercial vibration sensors.

Table 7.

Comparison of commercial vibration sensors.

| roduct / Model |

Wireless technology |

Energy source |

Bandwidth |

Nº Axis |

Information sent |

Data transmit |

| AEInnova Indueye (this paper) |

NB-IOT |

Waste heat. |

1Hz to 2KHz |

3 |

Velocity 3 axis. Spectrum |

Every 60 seconds up to 1 hour. |

| Everactive / Fluke 3562 [22] |

Proprietary Wireless protocol. Up to 1000 nodes and 250m. |

Waste Heat or solar |

6Hz a 1KHz |

3 |

Velocity 3 axis. Spectrum |

From 15 seconds to 15 minutes. |

| Emerson AMS [23] |

WirelessHART. Up to 100 nodes and 50m. |

Battery. Expected 3-5 years in lab conditions. |

X, Y 1KHz, Z up to 20KHz |

3 |

Velocity 3 axis. Spectrum. Battery voltage.. |

1 Hour velocity, 1 time per day Spectrum. |

| SKF Vibration Sensor [24] |

WirelessHART. Up to 100 nodes and 50m. |

Battery. Expected 2-3 years in lab conditions. |

10 Hz a 1KHz |

1 |

Vibration:

Velocity 3 axis. Acceleration. Battery voltage.

Temperature:

-40 a 85ºC. Precision +-2ºC.

|

Temperature every 5 minutes. Vibration every 1 hour. |

| Yokogawa Sushi [25] |

LoRaWAN (up to 2Km) |

Battery. Expected 2 years. |

10Hz a 1KHz. |

3 |

Vibration:

Velocity 3 axis. Acceleration. Battery voltage. Temperature:

|

1 data per minute up to every 3 days. |

6. Conclusions

This paper presented the modelling, testing, and application of IoT-WHRS systems designed to power IoT devices by harvesting waste heat from medium-temperature sources. These systems eliminate the need for external energy sources, enabling IoT nodes to be deployed in remote locations or critical facilities where power grids or batteries are impractical or not recommended.

The methodology proposed is generic and can be standardized for any IoT-WHRS architecture. Simulation and experimental results demonstrate strong agreement, confirming the feasibility of IoT-WHRS as a reliable power source for IoT devices. By utilizing thermoelectric technology, the system eliminates batteries, reducing maintenance costs and ensuring compatibility with explosive atmospheres (ATEX).

The integration of NB-IoT communication further enhances the system’s applicability in large industrial facilities, such as refineries, by providing long-range, low-power communication without extensive wiring. NB-IoT ensures efficient, scalable, and reliable real-time data transmission with low latency, critical for industrial monitoring. Comparative analysis of communication protocols highlights the energy efficiency of UDP over MQTT+TLS, making it an optimal choice for IIoT applications.

Additionally, the study emphasized the benefits of predictive maintenance through vibration monitoring in both the velocity domain (RMS) and spectrum domain (Hz). This approach effectively identifies potential failures in rotating machinery, enabling timely interventions and reducing downtime.

The real-world deployment of this system at the CEPSA La Rábida refinery showcases its ability to address key industrial challenges. By combining energy harvesting, advanced communication protocols, and predictive maintenance technologies, the proposed solution offers a sustainable, cost-effective, and scalable approach to improving energy efficiency, reducing environmental impact, and enhancing operational safety in energy-intensive industries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.A., J.O., and C.F.; methodology, R.A., J.O., and C.F.; software, R.A.; validation, R.A.; formal analysis, R.A., J.O; investigation, R.A. J.O; data curation, R.A., J.O., and C.F.; writing—review and editing, R.A., J.O., and C.F.; visualization, R.A.; project administration, R.A.; funding acquisition, R.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by (1) by the European Commission H2020 EIC Pilot Project InduEye 2.0 under grant number 946845.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

We thank Alternative Energy Innovations SL (AEInnova) technical staff, and CEPSA Oil refinery for facilitating the place for testing the pump in one of its Oil refineries in Spain.

Conflicts of Interest

The author Raúl Aragonés is employed by the company Alternative Energy Innovations, S.L.—AEInnova. Carles Ferrer and Joan Oliver declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- D. W. Kweku, O. Bismark, A. Maxwell, K. A. Desmond, K. B. Danso, E. A. Oti-Mensah, A. T. Quachie and B. B. Adormaa, ”Greenhouse effect: greenhouse gases and their impact on global warming,” in Journal of Scientific Research & Reports, JSRR.39630, 17(6), pp 1-9, Feb. 2018.

- G. Bianchi, G.P. Panayiotou, L. Aresti, S.A. Kalogirou, G. A. Florides, K. Tsamos, S.A. Tassou and P. Christodoulides., “Estimating the waste heat recovery in the European Union industry,” in Energy, Ecology and Environment, 4(5), pp. 211–221, Elsevier, 2019.

- H. Elahi, K. Munir, M. Eugeni. and S. Atek, P. Gaudenzi, “Energy harvesting towards self-powered IoT devices,” in Energies, 13, 5528, pp 1-31, 2020.

- O.H. Ando Junior, A. L. O. Maran and N. C. Henao, “A review of the development and applications of thermoelectric microgenerators for energy harvesting,” in Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 91, pp 376-393, 2018.

- S. Patidar, “Applications of thermoelectric energy: a review,” in International Journal for Research in Applied Science & Engineering Technology (IJRASET), Vol 6 no V, pp. 1992-1996, May, 2018.

- H.Jouhara, N. Khordehgah, S. Almahmoud, B. Delpech, A. Chauhan and S.A. Tassou, “Waste heat recovery technologies and applications,” in Thermal Science and Engineering Progress, 6, pp. 268-289, Elsevier, 2018.

- A. Rodríguez, J.G. Vián, D. Astrain and A. Martínez, “Study of thermoelectric systems applied to electric power generation,” in Energy Conversion and Management, 50, pp. 1236–1243, 2009.

- J. Oliver, R. Malet, R. Aragonés, R. Voces and C. Ferrer, “Waste heat recovery unit for energy intensive industries Thermoelectricity Harvesting,” in Proc. IEEE 29th International Symposium on Industrial Electronics (ISIE), Delft, The Netherlands, 2020, 17-19, pp 1041-1046.

- T. Sanislav, G.D. Mois, S. Zeadally, S.C. and Folea, “Energy harvesting techniques for internet of things (IoT),” in IEEE Access, Vol 9, pp. 39530-39549, Mar, 2021.

- S. Zeadally, F. K. Shaikh, A. Talpur and Q. Z. Sheng, "Design architectures for energy harvesting in the Internet of Things," in Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 128(1), pp 1-22.

- Jamil, N.; Hassan, M.; Lim, S.; Yusoff, A. "Predictive maintenance for rotating machinery by using vibration analysis." Journal of Mechanical Engineering and Sciences, 2021, 15(3), pp. 8289–8299.

- P. Aranguren, M. Araiz., D. Astrain and A. Martinez, “Thermoelectric generators for waste heat harvesting: a computational and experimental approach,” in Energy Conversion and Management, 148, pp. 680–91, 2017.

- S.L.L. Weera. “Analytical performance evaluation of thermoelectric modules using effective material properties”. M.S. Thesis. Western Michigan University. 2014.

- C. Alaoui, “Peltier thermoelectric modules modeling and evaluation,” in Int. Journal of Engineering (IJE), Vol. 5, Issue 1, pp 114-121, 2011.

- M. M. Yovanovich, J. R. Culham and P. Teertstra. “Calculating interface resistance”. University of Waterloo. 1997.

- H. Lee, “Thermal design: heat sinks, thermoelectrics, heat pipes, compact heat exchangers, and solar cells,” John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2011.

- Elise Brannon, “simplified vibration monitoring: ISO 10816-3 Guidelines”, https://www.cbmconnect.com/simplified-vibration-monitoring-iso-10816-3-guidelines/ , 2024. Accessed on 21st Nov 2024.

- M. M. Yovanovich, J. R. Culham and P. Teertstra. “Calculating interface resistance”. University of Waterloo. 1997.

- H. Lee, “Thermal design: heat sinks, thermoelectrics, heat pipes, compact heat exchangers, and solar cells,” John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2011.

- D. Luo, R. Wang and W. Yu, “Comparison and parametric study of two theroretical approaches based on an air-to-water thermoelectric generator system,” in Journal of Power Sources, 439, 226079, 2019.

- Rieger, N.; Kuhn, M. Predictive Maintenance in Rotating Machinery Based on ISO 10816 Vibration Standards. Journal of Mechanical Systems 2023, 45, 112–120.

- Everactive Website. Available online: https://everactive.com/ (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Emerson Website. Available online: https://www.emerson.com/en-gb/catalog/ams-wirelessvibrationmonitor-en-gb (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- SKF Website. Available online: https://www.skf.com/us/services/condition-based-maintenance/vibration-analysis-and-diagnostics (accessed on 4 July 2024).

- Yokogawa Website. Available online: https://www.yokogawa.com/us/solutions/solutions/asset-management-and-integrity/asset-performance-management/sushi-sensor/ (accessed on 4 July 2024).

Figure 1.

Benefits of predictive maintenance versus preventive maintenance.

Figure 1.

Benefits of predictive maintenance versus preventive maintenance.

Figure 2.

Color-coded threshold for a pump, applying ISO 10816 [

17].

Figure 2.

Color-coded threshold for a pump, applying ISO 10816 [

17].

Figure 4.

Energy harvesting architecture in IIoT nodes.

Figure 4.

Energy harvesting architecture in IIoT nodes.

Figure 5.

IoT-WHRS system and dimensions.

Figure 5.

IoT-WHRS system and dimensions.

Figure 6.

Thermal resistances and heat capacitances of the model.

Figure 6.

Thermal resistances and heat capacitances of the model.

Figure 7.

IIot Board with the processing and communicating sub-circuits.

Figure 7.

IIot Board with the processing and communicating sub-circuits.

Figure 8.

PCB with DC/DC MPPT, supercapacitors, Processing and communicating elements.

Figure 8.

PCB with DC/DC MPPT, supercapacitors, Processing and communicating elements.

Figure 10.

Temperature evolution (a) and power generated (b) results.

Figure 10.

Temperature evolution (a) and power generated (b) results.

Figure 11.

Power graph of the IoT-WHRS.

Figure 11.

Power graph of the IoT-WHRS.

Figure 12.

Comparison of the theoretical power computation (red dots) with respect to experimental power (blue line) as a function of the hot face and the cold face temperatures.

Figure 12.

Comparison of the theoretical power computation (red dots) with respect to experimental power (blue line) as a function of the hot face and the cold face temperatures.

Figure 13.

MQTT TLS energy profile.

Figure 13.

MQTT TLS energy profile.

Figure 14.

MQTT+TLS normalized versus UDP.

Figure 14.

MQTT+TLS normalized versus UDP.

Figure 15.

Pilot layout in CEPSA La Rábida.

Figure 15.

Pilot layout in CEPSA La Rábida.

Figure 16.

Results of 8 days testing.

Figure 16.

Results of 8 days testing.

Figure 17.

FFT of day November 17th at 1.30pm.

Figure 17.

FFT of day November 17th at 1.30pm.

Table 2.

TEG Thermoelectric Model.

Table 2.

TEG Thermoelectric Model.

| Seebeck effect: |

|

| Peltier effect: |

|

| Thomson effect: |

|

| Joule effect: |

|

| Efficiency coefficient: |

|

| Figure of merit: |

|

Table 3.

Effective Parameter Equations.

Table 3.

Effective Parameter Equations.

|

| |

|

| |

Table 4.

GM200-161-12-20 Specifications and Calculated Effective Parameters

Table 4.

GM200-161-12-20 Specifications and Calculated Effective Parameters

| Thermoelectric parameters |

| Number of pellets, n |

199 |

|

| Maximum power (Th=200 ºC), Wmax

|

5.3 |

W |

| Max. voltage (no load), Vmax

|

11.2 |

V |

| Max. current, Imax

|

1.88 |

A |

| Max. efficiency, ηmax

|

5.6 |

% |

| Matched load resistance (200 ºC), RL

|

5.9 |

Ω |

| Effective parameters |

| Effective Seebeck coefficient, α* |

3.33 10-4

|

V/K |

| Effective thermal conductivity, κ* |

1.94 |

W/(m·K) |

| Effective resistivity, ρ* |

3.8 10-5

|

Ω·m |

| Figure of merit Z* |

1.6 10-3

|

1/K |

| Figure of merit ZT* |

0.48 |

|

Table 5.

Simulation Conditions and Model Parameters.

Table 5.

Simulation Conditions and Model Parameters.

| Simulation setup parameters |

Rload = 10.0 Ω

Torque = 0.7 N/m

Force = 875000 Pa

Screw diameter = 5 mm ∅ |

Table 6.

Power comparison.

Table 6.

Power comparison.

|

Power Consumption |

| Protocol |

NB-IoT |

LTE-CATM1 |

| UDP |

1.17mWh |

2.15mWh |

| MQTT-TLS |

2.82mWh |

2.64mWh |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).