Submitted:

09 March 2025

Posted:

10 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

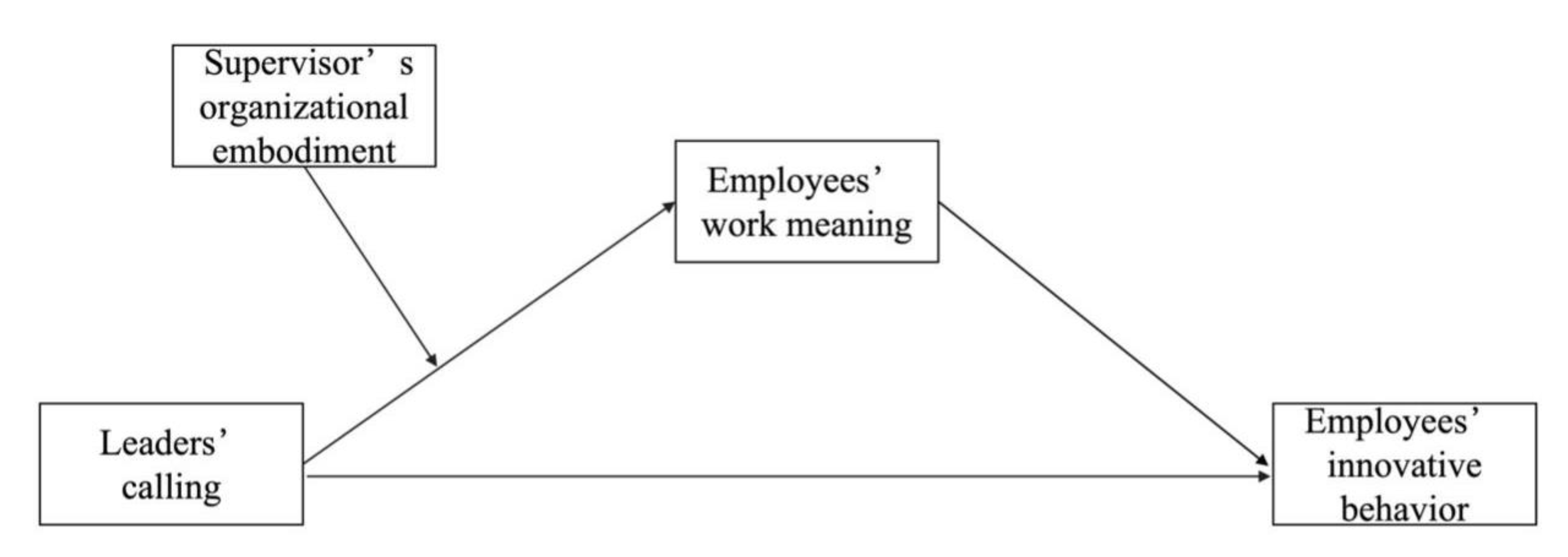

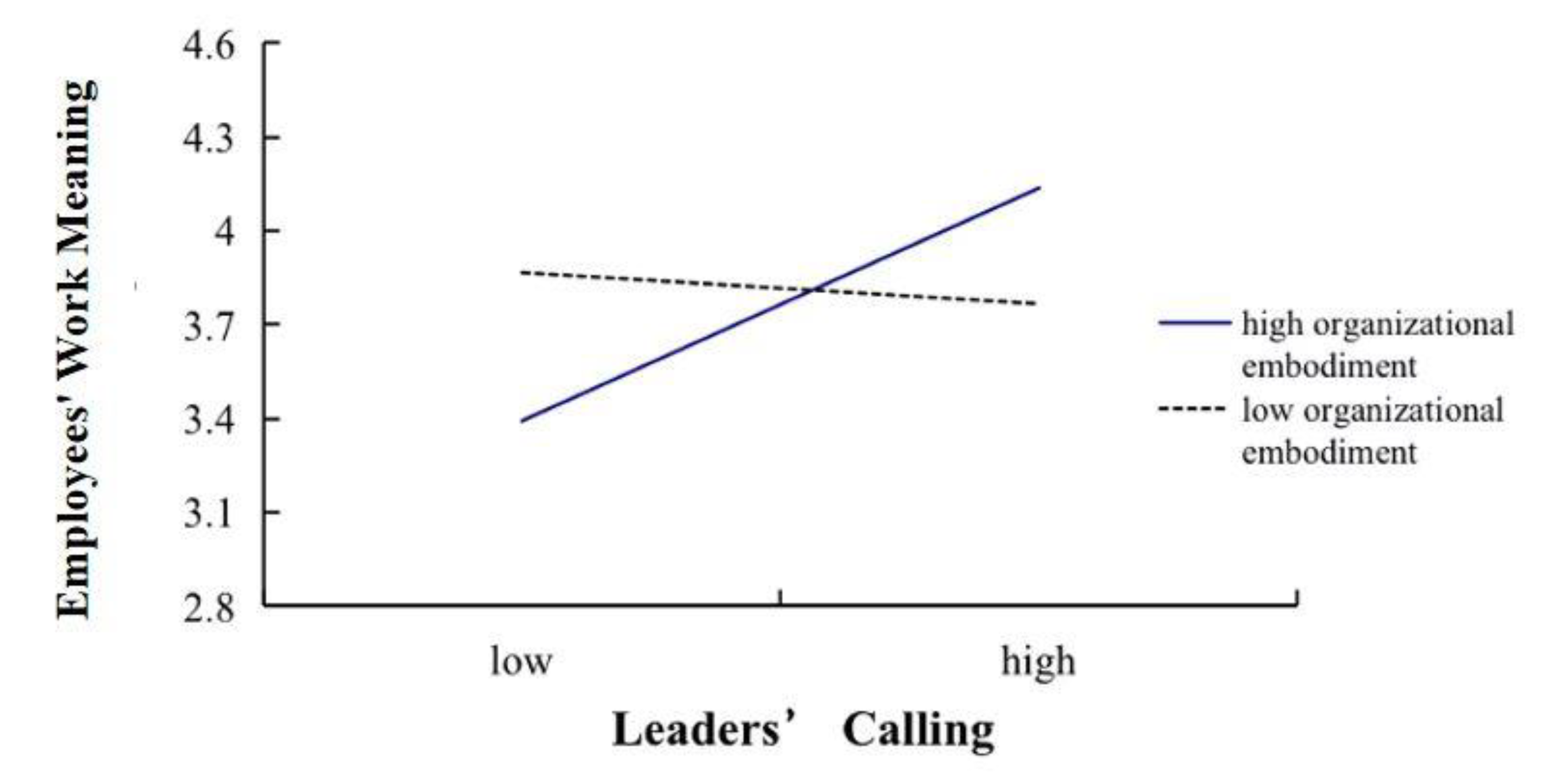

The objective of this research is to investigate whether and how leaders' sense of calling influences employees' innovative behavior, and to explore the conditions that may define the boundaries of this effect. This research, based on the theory of interpersonal sensemaking, conducted an empirical analysis using data from 186 pairs of supervisor-subordinate matching questionnaires and developed a moderated mediation model. We hypothesized and found that: firstly, leaders’ calling directly enhanced employees’ innovative behavior. Secondly, the relationship between the leaders’ calling and employees’ innovative behavior was mediated by employee’s sense of work meaning. Thirdly, the supervisor’s organizational embodiment positively regulated the relationship between the leaders’ calling and the employee’s sense of work meaning. Specifically, when the degree of supervisor’s organizational embodiment is higher, the relationship between the leaders’ calling and employee’s work meaning will be stronger. At the same time, the supervisor’s organizational embodiment positively regulates the mediating effect. Specifically, when the degree of supervisor’s organizational embodiment is higher, the mediating effect of employee’s work meaning is stronger.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. Leader’s Calling and Employees’ Innovative Behavior

2.2. Leaders’ Calling, Employees’ Work Meaning, and Employees’ Innovative Behavior

2.3. The Moderating Effect of Supervisor’s Organizational Embodiment on the Relationship Between Leaders’ Calling and Employees’ Creative Behavior

2.4. A Moderated Mediation Model

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedures

3.2. Measures

3.3. Analytic Strategy

4. Results

4.1. Assessment of the Measurement Model

4.2. Correlation Analysis

4.3. Tests of the Study Hypotheses

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limits and Future Directions

6. Conclusion

Appendix A

| 1=Strongly disagree or never |

| 2=Disagree |

| 3=Neutral |

| 4=Agree |

| 5= Strongly agree or very frequently |

References

- Zhou, J.; George, J.M. Awakening employee creativity: The role of leader emotional intelligence. Leadersh. Q. 2003, 14, 545–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirst, G.; Van Dick, R.; Van Knippenberg, D. A social identity perspective on leadership and employee creativity. J. Organ. Behav. 2009, 30, 963–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, Z.; Liang, L.; Zhang, X. Why and when paradoxical leader behavior impacts employee creativity: Thriving at work and psychological safety. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 1911–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tierney, P. Leadership and employee creativity. In Handbook of Organizational Creativity; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Krasikova, D.V.; Liu, D. I can do it, so can you: The role of leader creative self-efficacy in facilitating follower creativity. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2016, 132, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dik, B.J.; Duffy, R.D. Calling and vocation at work: Definitions and prospects for research and practice. Couns. Psychol. 2009, 37, 424–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schabram, K.; Nielsen, J.; Thompson, J. The dynamics of work orientations: An updated typology and agenda for the study of jobs, careers, and callings. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2023, 17, 405–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.G.; Bruce, R.A. Determinants of innovative behavior: A path model of individual innovation in the workplace. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 37, 580–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amabile, T.M.; Pratt, M.G. The dynamic componential model of creativity and innovation in organizations: Making progress, making meaning. Res. Organ. Behav. 2016, 36, 157–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, A.B.; Dik, B.J.; Conner, B.T. Conceptualizing calling: Cluster and taxometric analyses. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 114, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, R.D.; Bott, E.M.; Allan, B.A.; Torrey, C.L.; Dik, B.J. Perceiving a calling, living a calling, and job satisfaction: Testing a moderated, multiple mediator model. J. Couns. Psychol. 2012, 59, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirschi, A. Callings and work engagement: Moderated mediation model of work meaningfulness, occupational identity, and occupational self-efficacy. J. Couns. Psychol. 2012, 59, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafi, M.; Lei, Z.; Song, X.; Sarker, M.N.I. The effects of transformational leadership on employee creativity: Moderating role of intrinsic motivation. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2020, 25, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.H.; Bai, Y. Leaders can facilitate creativity: The moderating roles of leader dialectical thinking and LMX on employee creative self-efficacy and creativity. J. Manag. Psychol. 2020, 35, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin Saeed, B.; Afsar, B.; Shahjehan, A.; Imad Shah, S. Does transformational leadership foster innovative work behavior? The roles of psychological empowerment, intrinsic motivation, and creative process engagement. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraž. 2019, 32, 254–281. [CrossRef]

- Kark, R.; Van Dijk, D.; Vashdi, D.R. Motivated or demotivated to be creative: The role of self-regulatory focus in transformational and transactional leadership processes. Appl. Psychol. 2018, 67, 186–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Liu, H.; Gu, J. A multi-level study of servant leadership on creativity: The roles of self-efficacy and power distance. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2017, 38, 610–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D.J.; Lee, A.; Tian, A.W.; Newman, A.; Legood, A. Leadership, creativity, and innovation: A critical review and practical recommendations. Leadersh. Q. 2018, 29, 549–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.M. Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 1442–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, B.D.; Dekas, K.H.; Wrzesniewski, A. On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Res. Organ. Behav. 2010, 30, 91–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzesniewski, A.; Dutton, J.E.; Debebe, G. Interpersonal sensemaking and the meaning of work. Res. Organ. Behav. 2003, 25, 93–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoss, M.K.; Eisenberger, R.; Restubog, S.L.D.; Zagenczyk, T.J. Blaming the organization for abusive supervision: The roles of perceived organizational support and supervisor’s organizational embodiment. J. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 98, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberger, R.; Shoss, M.K.; Karagonlar, G.; Gonzalez-Morales, M.G.; Wickham, R.E.; Buffardi, L.C. The supervisor POS-LMX-subordinate POS chain: Moderation by reciprocation wariness and supervisor’s organizational embodiment. J. Organ. Behav. 2014, 35, 635–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.E.; Treviño, L.K.; Harrison, D.A. Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2005, 97, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Learning Theory; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse, A.N.; Van Knippenberg, D.; Schippers, M.; Stam, D. Transformational and transactional leadership and innovative behavior: The moderating role of psychological empowerment. J. Organ. Behav. 2010, 31, 609–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cingöz, A.; Akdoğan, A.A. An empirical examination of performance and image outcome expectation as determinants of innovative behavior in the workplace. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 24, 847–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Huang, J.C.; Farh, J.L. Employee learning orientation, transformational leadership, and employee creativity: The mediating role of employee creative self-efficacy. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 765–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sameer, Y.M. Innovative behavior and psychological capital: Does positivity make any difference? J. Econ. Manag. 2018, 32, 75–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Jiang, W. Transformational leadership, transactional leadership, and employee creativity in entrepreneurial firms. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2018, 54, 302–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.; Li, M. Proactive personality and innovative behavior: The mediating roles of job-related affect and work engagement. Soc. Behav. Personal. 2018, 46, 431–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, N.K.; Dhar, R.L. Transformational leadership, innovation climate, creative self-efficacy and employee creativity: A multilevel study. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 51, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yidong, T.; Xinxin, L. How ethical leadership influence employees’ innovative work behavior: A perspective of intrinsic motivation. J. Bus. Ethics. 2013, 116, 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Peng, Y.; Zhu, Y. How does empowering leadership motivate employee innovative behavior: A job characteristics perspective. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 18280–18290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Lee, K.; Lim, J.I.; Sohn, Y.W. Leading with callings: Effects of leader’s calling on followers’ team commitment, voice behavior, and job performance. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Sohn, Y.W. Is it happy to work with leaders viewing their work as a calling? Investigating mediators and a moderator on the relationship between leader calling and follower job satisfaction. Korean J. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2018, 31, 353–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buis, B.C.; Kluemper, D.H.; Weisman, H.; Tao, S. Your employees are calling: How organizations help or hinder living a calling at work. J. Vocat. Behav. 2024, 149, 103958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldham, G.R.; Cummings, A. Employee creativity: Personal and contextual factors at work. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 607–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.J.; Zhou, J. Transformational leadership, conservation, and creativity: Evidence from Korea. Acad. Manag. J. 2003, 46, 703–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avey, J.B.; Luthans, F.; Youssef, C.M. The additive value of positive psychological capital in predicting work attitudes and behaviors. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 430–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Lysova, E.I.; Bossink, B.A.; Khapova, S.N.; Wang, W. Psychological capital and self-reported employee creativity: The moderating role of supervisor support and job characteristics. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2019, 28, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, G.; Li, Y.; Hong, A. The strategic role of digital transformation: Leveraging digital leadership to enhance employee performance and organizational commitment in the digital era. Systems. 2024, 12, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, W.; Tang, X.; Li, Y.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, H. Perceived organizational support and employee creativity: The mediation role of calling. Creat. Res. J. 2020, 32, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalley, C.E.; Gilson, L.L. What leaders need to know: A review of social and contextual factors that can foster or hinder creativity. Leadersh. Q. 2004, 15, 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M.F.; Dik, B.J.; Duffy, R.D. Measuring meaningful work: The work and meaning inventory (WAMI). J. Career Assess. 2012, 20, 322–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, M.S.; Garza, A.S.; Slaughter, J.E. Work engagement: A quantitative review and test of its relations with task and contextual performance. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 89–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharaj, I.; Schlechter, A.F. Meaning in life and meaning of work: Relationships with organizational citizenship behaviour, commitment and job satisfaction. Manag. Dyn. 2007, 16, 24–41 https://hdlhandlenet/10520/EJC69726. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, J.; Jiang, X.; Ding, S.; Xie, L.; Huang, B. Calling leveraged work engagement: Above and beyond the effects of job and personal resources. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2018, 21, 107–120 https://linkoverseacnkinet/doi/1016471/jcnki11. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Cardona, I.; Vera, M.; Marrero-Centeno, J. Job resources and employees’ intention to stay: The mediating role of meaningful work and work engagement. J. Manag. Organ. 2023, 29, 930–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, M.; Colbert, A.E.; Nielsen, J.D. Stories of calling: How called professionals construct narrative identities. Adm. Sci. Q. Adm. Sci. Q. 2021, 66, 66–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, R.D.; Dik, B.J.; Douglass, R.P.; England, J.W.; Velez, B.L. Work as a calling: A theoretical model. J. Couns. Psychol. J. Couns. Psychol. 2018, 65, 65–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martela, F.; Pessi, A.B. Significant work is about self-realization and broader purpose: Defining the key dimensions of meaningful work. Front. Psychol. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 9–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbach, A.; Woolley, K. The structure of intrinsic motivation. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2022, 9, 9–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.; Zhang, X.; Miao, J.; Zhang, X.; Xu, J. The conceptualization, antecedents and interventions of occupational calling in Chinese context. Adv. Psychol. Sci. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2023, 31, 31–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B.; Umrani, W.A. Transformational leadership and innovative work behavior: The role of motivation to learn, task complexity and innovation climate. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2020, 23, 23–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashdan, T.B.; Rose, P.; Fincham, F.D. Curiosity and exploration: Facilitating positive subjective experiences and personal growth opportunities. J. Pers. Assess. 2004, 82, 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, M.; Fishbach, A. The small-area hypothesis: Effects of progress monitoring on goal adherence. J. Consum. Res. J. Consum. Res. 2012, 39, 493–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Karagonlar, G.; Stinglhamber, F.; Neves, P.; Becker, T.E.; Gonzalez-Morales, M.G.; Steiger-Mueller, M. Leader–member exchange and affective organizational commitment: The contribution of supervisor’s organizational embodiment. J. Appl. Psychol. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 95–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.D.; Hou, Y.H.; Chen, K.Y.; Zhuang, W.L. To help or not to help: Antecedents of hotel employees’ organizational citizenship behavior. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 30–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Lin, X.; Ding, H. The influence of supervisor developmental feedback on employee innovative behavior: A moderated mediation model. Front. Psychol. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 10–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Shanock, L. Rewards, intrinsic motivation, and creativity: A case study of conceptual and methodological isolation. Creat. Res. J. Creat. Res. J. 2003, 15, 15–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackey, J.D.; McAllister, C.P.; Brees, J.R.; Huang, L.; Carson, J.E. Perceived organizational obstruction: A mediator that addresses source-target misalignment between abusive supervision and OCBs. J. Organ. Behav. J. Organ. Behav. 2018, 39, 39–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, D.M.; Kuenzi, M.; Greenbaum, R.; Bardes, M.; Salvador, R.B. How low does ethical leadership flow? Test of a trickle-down model. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2009, 108, 108–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dik, B.J.; Eldridge, B.M.; Steger, M.F.; Duffy, R.D. Development and validation of the calling and vocation questionnaire (CVQ) and brief calling scale (BCS). J. Career Assess. J. Career Assess. 2012, 20, 20–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Lu, X.; Choi, J.N.; Guo, W. Ethical leadership and team-level creativity: Mediation of psychological safety climate and moderation of supervisor support for creativity. J. Bus. Ethics. J. Bus. Ethics. 2019, 159, 159–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017.

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G.; Reno, R.R. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991.

- Li, S.; Yu, W.; Lei, Y.; Hu, M. How does spiritual leadership inspire employees’ innovative behavior? The role of psychological capital and intrinsic motivation. Eur. Rev. Appl. Psychol. Eur. Rev. Appl. Psychol. 2023, 73, 73–100905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalley, C.E.; Gilson, L.L.; Blum, T.C. Interactive effects of growth need strength, work context, and job complexity on self-reported creative performance. Acad. Manag. J. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 52–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuckert, M.; Kim, T.T.; Paek, S.; Lee, G. Motivate to innovate: How authentic and transformational leaders influence employees’ psychological capital and service innovation behavior. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 30–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Gong, Z.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, Y. Impact of the supervisor feedback environment on creative performance: A moderated mediation model. Front. Psychol. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xu, H.; Liu, Y. Servant leadership as a driver of employee service performance: Test of a trickle-down model and its boundary conditions. Hum. Relat. Hum. Relat. 2018, 71, 71–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinglhamber, F.; Marique, G.; Caesens, G.; Hanin, D.; De Zanet, F. The influence of transformational leadership on followers’ affective commitment: The role of perceived organizational support and supervisor’s organizational embodiment. Career Dev. Int. Career Dev. Int. 2015, 20, 20–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, A.; Keller, A.C.; Spurk, D.M. Living one’s calling: Job resources as a link between having and living a calling. J. Vocat. Behav. J. Vocat. Behav. 2018, 106, 106–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, T.L.; Crino, M.D.; Fredendall, L.D. An integrative model of the empowerment process. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2002, 12, 12–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, A.M. Leading with meaning: Beneficiary contact, prosocial impact, and the performance effects of transformational leadership. Acad. Manag. J. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 55–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auger, P.; Woodman, R.W. Creativity and intrinsic motivation: Exploring a complex relationship. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2016, 52, 52–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaubroeck, J.; Peng, A.C.; Hannah, S.T.; Ma, J.; Cianci, A.M. Struggling to meet the bar: Occupational progress failure and informal leadership behavior. Acad. Manag. J. Acad. Manag. J. 2021, 64, 64–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birdi, K.; Leach, D.; Magadley, W. The relationship of individual capabilities and environmental support with different facets of designers’ innovative behavior. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2016, 33, 33–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Item | Number (person) | Proportion |

| Gender | Male | 62 | 33.3% |

| Female | 124 | 66.7% | |

| Age | Under 25 years old | 30 | 16.1% |

| 25 (inclusive)-35 years old | 111 | 59.7% | |

| 35 (inclusive)-45 years old | 32 | 17.2% | |

| 45 (inclusive)-55 years old | 13 | 7.0% | |

| Education | Below junior college | 17 | 9.1% |

| Junior college | 46 | 24.7% | |

| Undergraduate | 102 | 54.8% | |

| Masters’ degree | 19 | 10.2% | |

| Doctoral degree or post-doctorate | 2 | 1.1% | |

| Organizational tenure | Less than 1 year | 52 | 28.0% |

| 1 (inclusive) to 5 years | 90 | 48.4% | |

| 5 (inclusive) to 10 years | 26 | 14.0% | |

| More than 10 (inclusive) years | 18 | 9.7% | |

| Leader–follower dyad tenure | Less than 1 year | 72 | 38.7% |

| 1 (inclusive) to 5 years | 102 | 54.8% | |

| 5 (inclusive) to 10 years | 10 | 5.4% | |

| More than 10 (inclusive) years | 2 | 1.1% |

| Model | χ2 | df | △χ2 | RMSEA | CFI | NFI |

| Four-factor model (L; E; M; B) | 296.35 | 129 | .08 | .95 | .92 | |

| Three-factor model (L+E; M; B) | 886.72 | 132 | 590.37 | .18 | .80 | .77 |

| Three-factor model (M+B; L; E) | 531.51 | 132 | 235.16 | .13 | .88 | .84 |

| Two-factor model (L+E; M+B) | 1115.09 | 134 | 818.74 | .20 | .72 | .69 |

| One-factor model (L+ E+M+B | 1597.16 | 135 | 1300.81 | .24 | .61 | .58 |

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 1.Leaders’ calling | 3.92 | .73 | ||||||||

| 2.Employees’ work meaning | 3.75 | .87 | .18* | |||||||

| 3.Employees’ innovative behavior | 3.47 | .90 | .24** | .25** | ||||||

| 4.Supervisor’s organizational embodiment | 2.19 | .82 | -.20** | -.09 | -.13 | |||||

| 5.Gender | 1.67 | .47 | .21** | -.17* | -.06 | -.09 | ||||

| 6.Age | 2.15 | .77 | -.09 | .01 | .09 | .19* | -.31*** | |||

| 7.Education | 2.69 | .82 | .21** | .07 | .07 | -.17* | .41*** | -.37*** | ||

| 8.Org. tenure | 2.05 | .90 | -.19* | .17* | .17* | .08 | -.28*** | .46*** | -.26*** | |

| 9.Dyad. tenure | 1.69 | .62 | -.06 | .10 | .21** | -.01 | - .06 | .20** | .02 | .60*** |

| Variables | Outcome: employees’ innovative behavior | Outcome: employees’ work meaning | |||

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | |

| Control variables | |||||

| Gender | -.06 | -.10 | -.22** | -.24** | -.22** |

| Age | .06 | .04 | -.09 | -.10 | -.09 |

| Education | .13 | .10 | .18* | .15 | .13 |

| Org. tenure | .07 | .11 | .22* | .26* | .26* |

| Dyad. tenure | .15 | .14 | -.04 | -.04 | -.02 |

| Predictors | |||||

| Leaders’ calling | .27*** | .23** | .24** | ||

| Moderator | |||||

| Supervisor’s organizational embodiment | -.04 | -.02 | |||

| Interaction term | |||||

| Leaders’ calling × supervisor’s organizational embodiment | .20** | ||||

| △R2 | .07 | . | .05 | .04 | |

| F | 2.34* | 4.44*** | 3.27** | 4.00*** | 4.60*** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).