Introduction

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the increase in mortality in Japan has become a topic of discussion [

1]. In particular, reports indicate a rise in excess mortality, which represents the difference between observed deaths and the expected deaths projected based on historical data and statistical models.

Notably, since 2021, mortality rates have increased significantly, posing a major public health challenge. Statistical data up to 2022 suggest that, in addition to COVID-19 itself, factors such as senility, cardiovascular diseases, and malignant neoplasms have contributed to the rising mortality rate [

2]. Moreover, long-term monitoring of excess mortality and other quantitative data beyond 2022 has been emphasized as essential [

3].

In February 2025, nationwide and municipal-level statistical reports on mortality in 2024 have begun to be released. Discussions on social media platforms such as X have highlighted concerns regarding a renewed increase in deaths in 2024. (

https://x.com/cr_cidp/status/1895037084777488589, https://x.com/sunsun_38/status/1895017200710496449)

Analysis of National and Municipal Mortality Trends

Interested in the data observed on social media, the author first verified the accuracy of annual nationwide mortality trends in Japan over the past decade (since 2015) using the confirmed statistics published in the Vital Statistics of Japan by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. (

https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/list/81-1a.html) For 2024, preliminary figures published on the relevant governmental website were adopted.

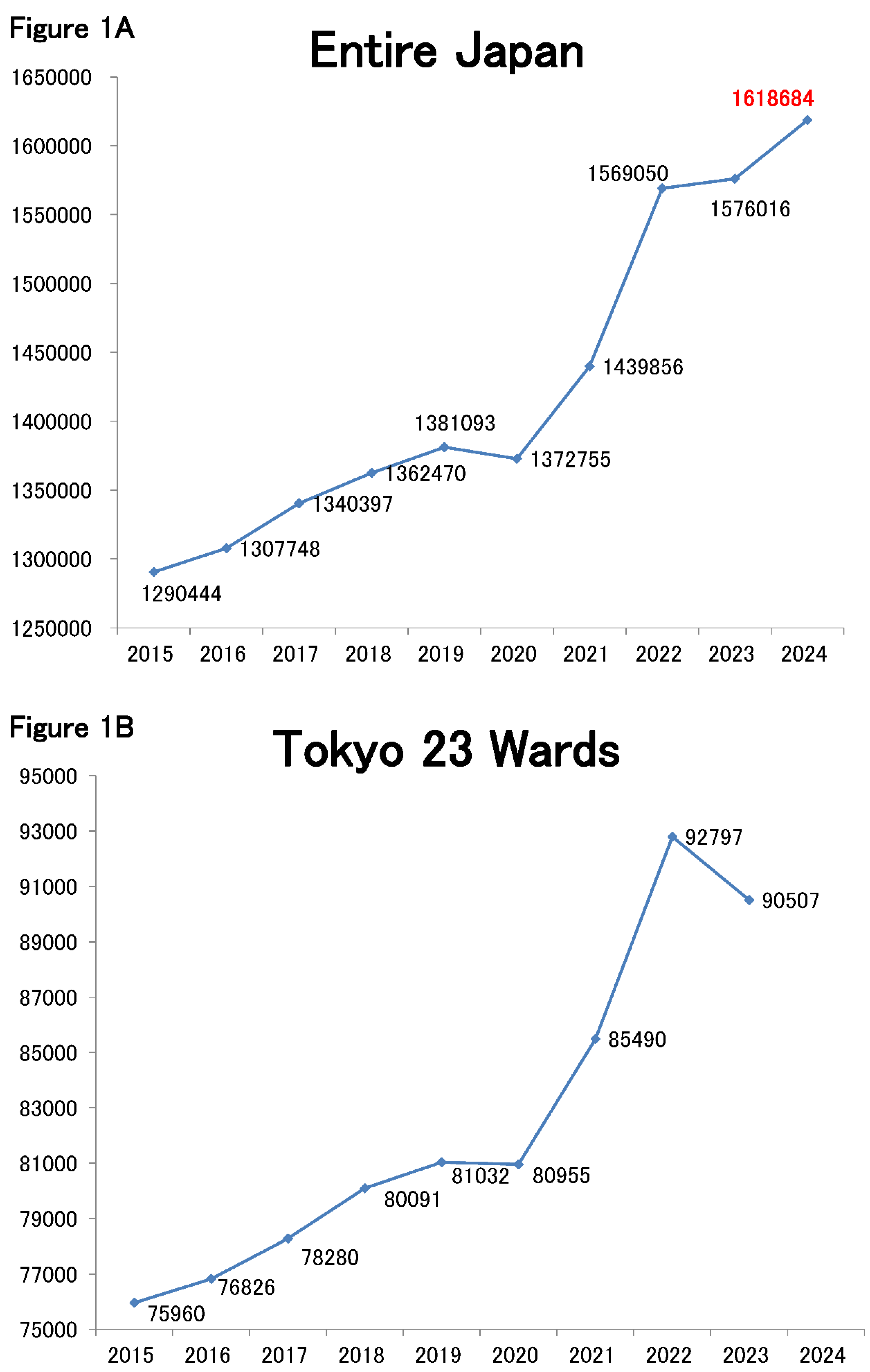

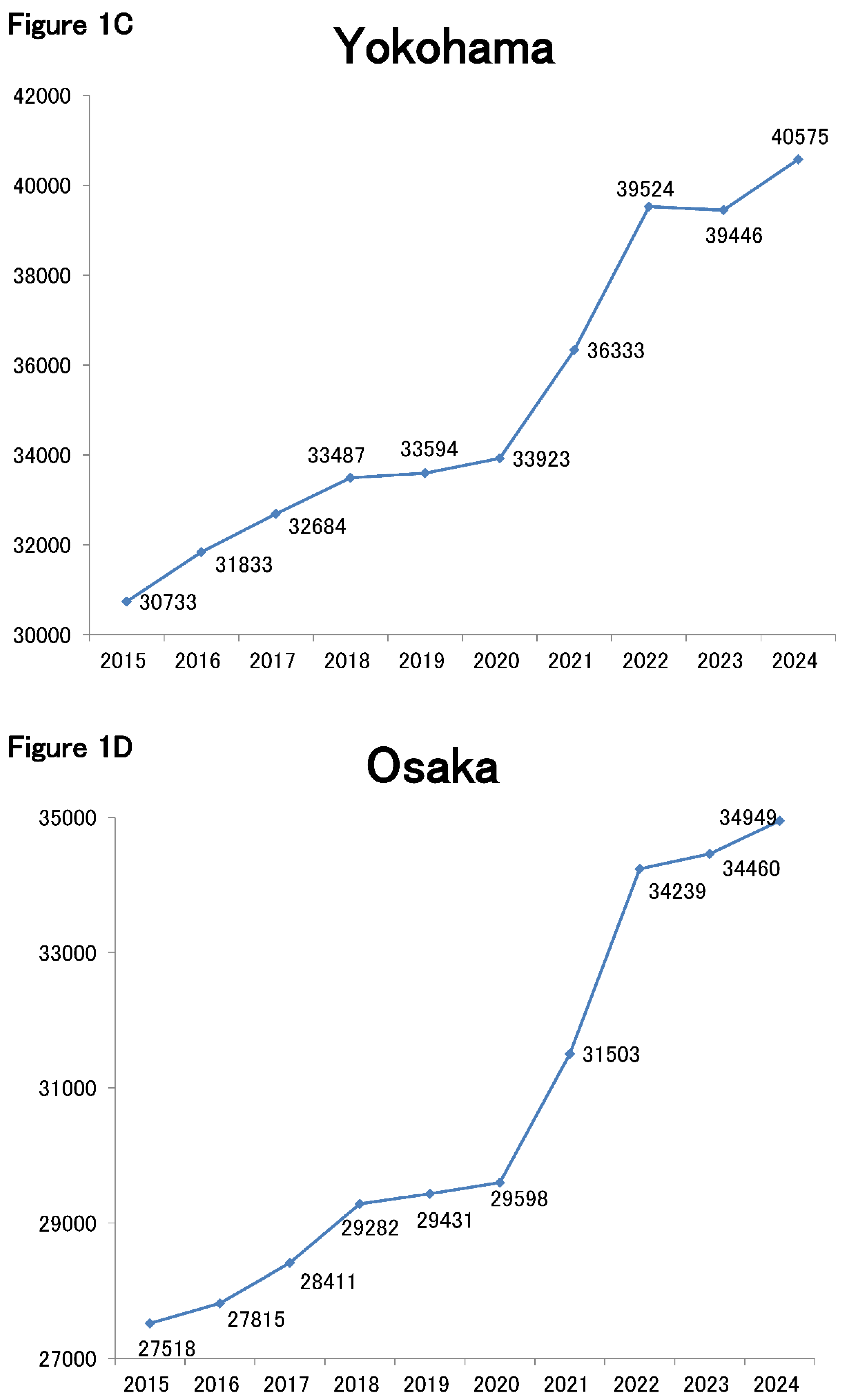

A line graph plotting these figures is presented in Figure 1A, which closely resembles those observed on social media. The nationwide mortality trend in Japan showed a slight decline in 2020, the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, followed by a significant increase for two consecutive years in 2021 and 2022. Mortality remained elevated in 2023 and 2024.

Figure 1.

Trends in the number of deaths for each year since 2015. A: Entire Japan, B: Tokyo 23 Wards, C: Yokohama, D: Osaka, E: Nagoya, F: South Korea.

Figure 1.

Trends in the number of deaths for each year since 2015. A: Entire Japan, B: Tokyo 23 Wards, C: Yokohama, D: Osaka, E: Nagoya, F: South Korea.

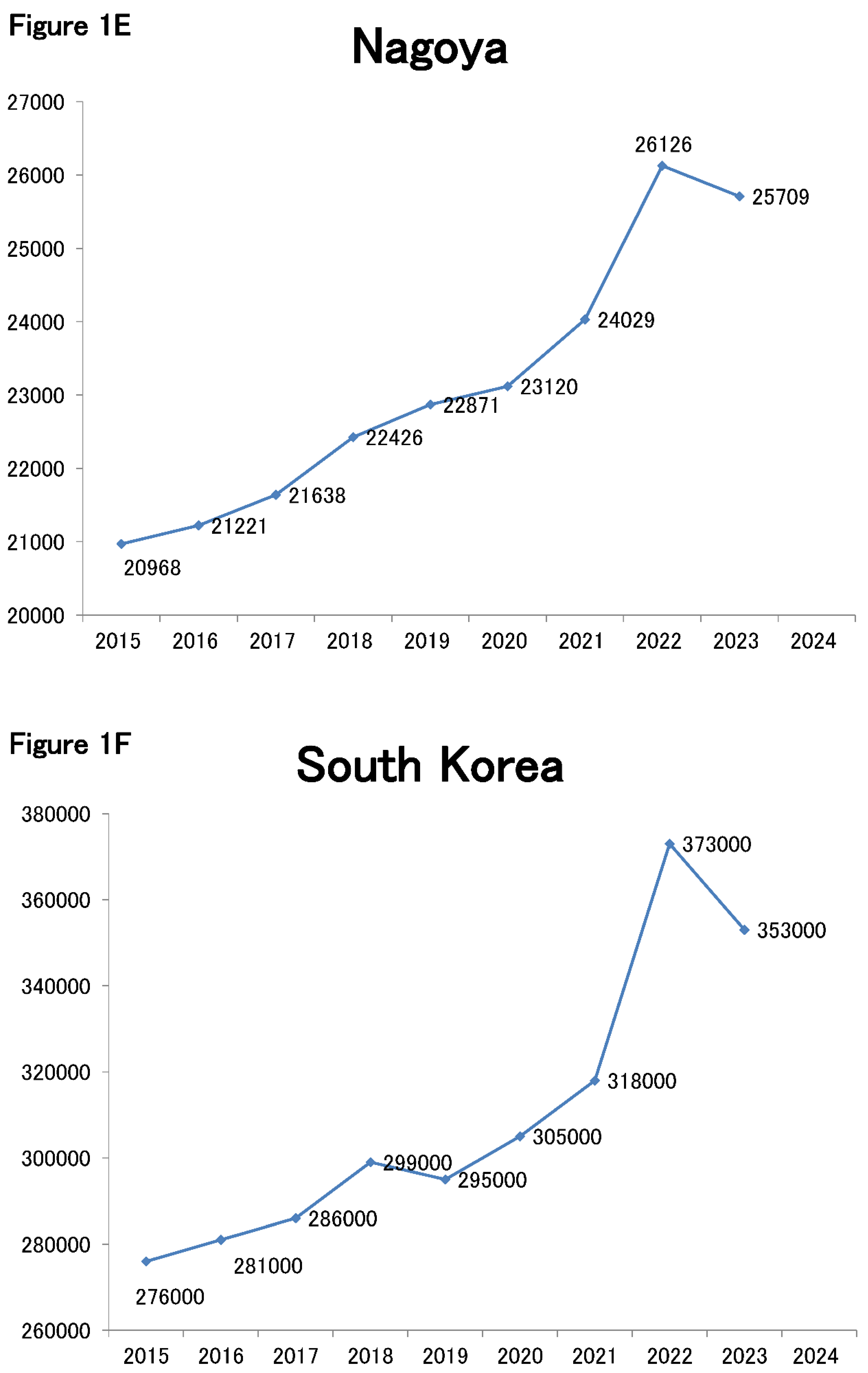

How do these trends compare at the municipal level? To investigate this, line graphs were generated for annual mortality trends in Japan’s four largest cities by population—Tokyo’s 23 wards, Yokohama, Osaka, and Nagoya—using publicly available statistical data from each municipal government (

Table 1 provides URLs to these data sources). The mortality trends for Tokyo’s 23 wards (

Figure 1B), Yokohama City (

Figure 1C), Osaka City (

Figure 1D), and Nagoya City (

Figure 1E) are shown.

Similar to the nationwide trend (Figure 1A), mortality in all four major cities increased sharply from 2021 and remained elevated through 2022 and 2023. In cities where preliminary 2024 data were available—Yokohama and Osaka—mortality figures showed a further increase in 2024. Overall, all four major cities exhibited nearly identical mortality trends.

Mortality Trends Outside Japan

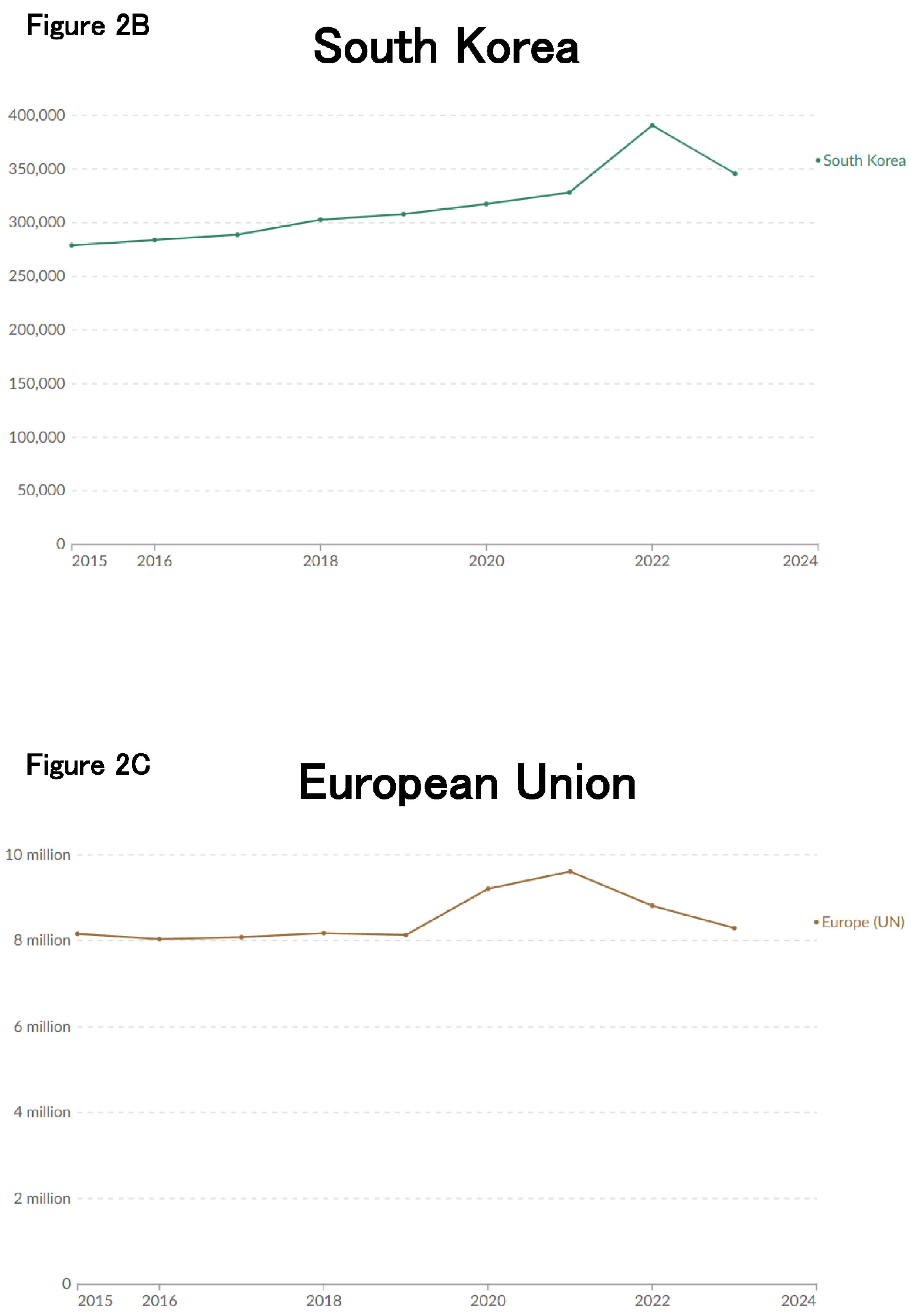

How have mortality trends evolved in countries outside Japan? To investigate this, population statistics from South Korea (

https://kostat.go.kr/ansk/) were collected and analyzed in the same manner. The results revealed a sharp increase in mortality beginning in 2022, followed by persistently high mortality in 2023, demonstrating a pattern similar to that observed in Japan.

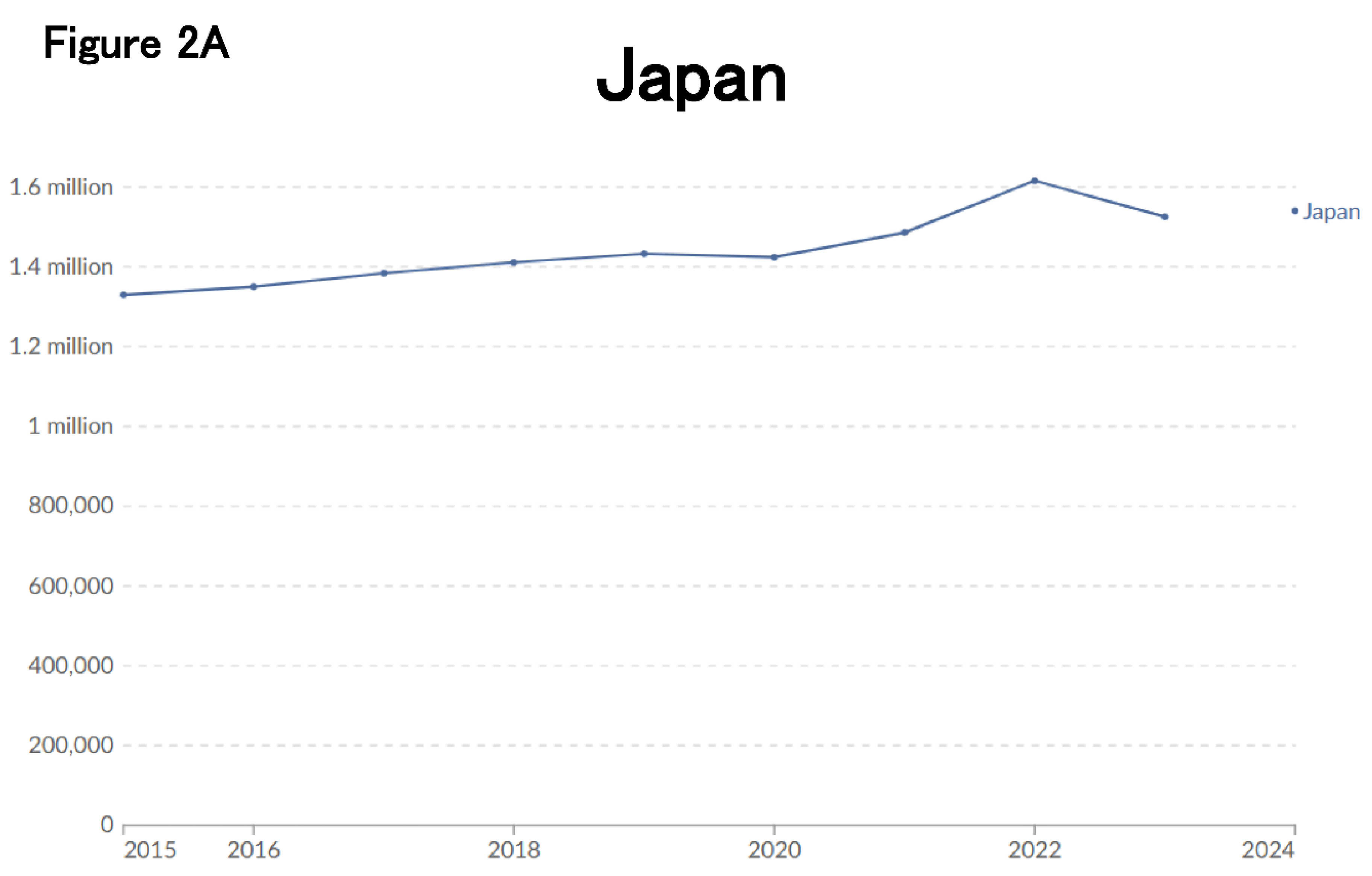

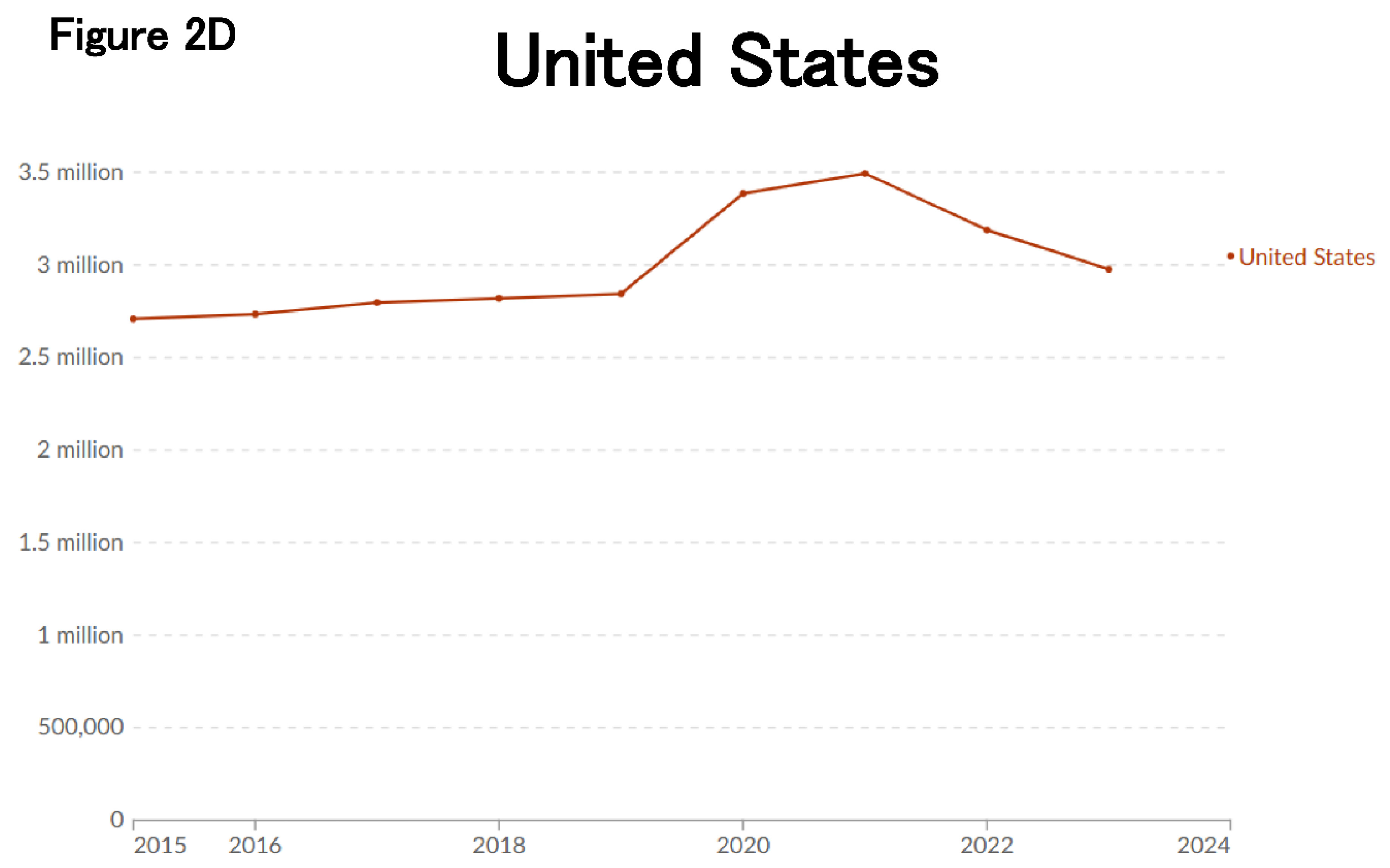

Using data from Our World in Data (

https://ourworldindata.org/births-and-deaths), we plotted the mortality trends for Japan (

Figure 2A) and South Korea (

Figure 2B). While minor discrepancies exist due to differences in data aggregation methods, the overall trends align with those shown in

Figure 1A and

Figure 1E. Specifically, no significant increase in mortality was observed in 2020; however, mortality began to rise from 2021 to 2022. In contrast, mortality trends in the European Union (

Figure 2C) and the United States (

Figure 2D) exhibited a different pattern: these regions experienced a sharp increase in deaths in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic (2020), followed by a decline in mortality from 2022 to 2023.

Figure 2.

Trends in the number of deaths in each country since 2015. A: Japan, B: South Korea, C: European Union, D: United States.

Figure 2.

Trends in the number of deaths in each country since 2015. A: Japan, B: South Korea, C: European Union, D: United States.

During the early phase of the pandemic, East Asian countries such as Japan and South Korea recorded significantly fewer severe cases and deaths from COVID-19 compared to Western nations. The underlying reason for this disparity remained unclear and was referred to as “Factor X.” However, leading infectious disease experts categorically dismissed the existence of “Factor X” as a mere illusion. The author has repeatedly questioned whether such a dismissal was appropriate [

4,

5]. Given that the impact of infectious diseases can vary significantly depending on genetic, environmental, and regional factors, it is crucial to consider such differences when formulating future pandemic response strategies.

Preliminary Mortality Data for January 2025 and Possible Contributing Factors

The preliminary mortality data for each municipality in January 2025 was released in February 2025, revealing a significant increase in the number of deaths compared to the previous year. This sharp rise has become a topic of widespread discussion.

A study in the United Kingdom has reported that the Standardized Mortality Ratio (SMR) for all-cause mortality is higher in COVID-19 vaccinated individuals compared to unvaccinated individuals [

6]. Opponents of COVID-19 vaccination argue that the recent increase in excess mortality is a direct consequence of the harmful effects of COVID-19 vaccines.

Indeed, there are opinions that the long-term effects of mRNA vaccines may have contributed to an increase in cardiovascular diseases or immune dysfunction [

7], and this possibility cannot be entirely ruled out. Furthermore, the significant increase in the number of deaths in Japan became evident in 2021, when COVID-19 vaccinations began. Some have speculated that the rise in mortality observed from 2024 to 2025 may be a delayed manifestation of vaccine-related adverse effects or long-term complications. However, in addition to the potential impact of vaccines, several other factors may also have contributed to the increase in mortality. One major factor is demographic: in 2024, the baby boomer generation in Japan reached the age of 75 and older, a stage at which natural mortality rates begin to rise. Additionally, issues related to healthcare access, such as the strain on medical institutions and a decline in healthcare-seeking behavior, may have played a role. The aftermath of the pandemic also led to increased stress levels and a decline in routine health checkups, potentially exacerbating chronic diseases. The author has previously pointed out that prioritizing infection control may have led to delays in diagnosing other diseases 5), and that strict patient isolation protocols may have hindered flexible responses in clinical settings, potentially lowering the overall quality of medical care [

8]. Although there may be an opinion that if infection control measures had not been implemented, the number of deaths directly caused by COVID-19 would have been higher, if the extensive efforts, financial costs, and sacrifices made for infection control ultimately led to an increase in mortality, it would be a deeply ironic outcome.

Alternative Explanations from Vaccine Advocates

Conversely, proponents of COVID-19 vaccination may argue that the increase in mortality observed in 2024 stemmed from a decline in vaccine uptake in 2023. A report has suggested that COVID-19 vaccination contributed to a reduction in excess mortality among the elderly [

9]. Proponents may contend that individuals—particularly older adults and those with underlying health conditions—faced an elevated risk of severe disease and mortality due to decreased vaccine coverage. However, given that the severity of COVID-19 had declined substantially by 2023, it remains challenging to assert definitively that reduced vaccination rates were the primary driver of excess mortality. Moreover, the total annual deaths attributed to COVID-19 in recent years have been approximately 30,000

The Complexity of Mortality Trends and the Need for Careful Analysis

It is difficult to definitively determine whether the arguments presented by either proponents or opponents of COVID-19 vaccination are simply “correct” or “incorrect.” Changes in mortality rates are influenced by a multitude of factors, necessitating careful and rigorous data analysis. Rather than drawing simplistic causal conclusions, it is crucial to continue examining the issue from multiple perspectives.

To be candid, the author was initially skeptical about the accuracy of social media posts at the end of February 2025 that reported a significant increase in mortality. However, as demonstrated in this paper, data extracted from publicly accessible sources, including the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare and various municipal governments, and plotted on a simple line graph confirmed that the reported trend was indeed real.

Readers interested in verifying this finding are encouraged to consult the URLs listed in

Table 1, which link to statistical data from each municipality. Those who identify any discrepancies or potential errors in the data are welcome to contact the author.

Japan’s Declining Population and Its Implications

While the number of deaths in Japan has markedly increased, the birth rate has simultaneously declined sharply. Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the rise in mortality has exceeded initial projections, making it evident that Japan is facing a more significant population decline than previously anticipated. This demographic shift will bring substantial challenges, including economic stagnation, a decline in international influence, difficulties in maintaining social infrastructure and welfare systems, and security concerns. These issues will weigh heavily on Japanese society. However, regardless of whether we wish to acknowledge it, we must objectively confront this reality. Moving forward, the critical challenge will be to construct a sustainable society based on a model of shrinking equilibrium, in which population decline is assumed and accounted for in economic and social planning.

Population decline due to low birth rates and aging is a pressing social issue not only in Japan but also in other developed countries. In contrast, many developing countries continue to grapple with rapid population growth. The challenges of food and energy crises are global in nature, and population decline could contribute to reducing environmental burdens. From the perspective of environmental conservation, a shrinking population may not necessarily be viewed as an entirely negative phenomenon. By pioneering a model for a declining population society, Japan could provide valuable insights into the development of a sustainable future.

References

- Kaneda Y, Yamashita E, Kaneda U, Tanimoto T, Ozaki A. Japan’s Demographic Dilemma: Navigating the Postpandemic Population Decline. JMA J. 2024 Jul 16;7(3):403-405. Epub 2024 Jun 3. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka H, Nomura S, Katanoda K. Changes in Mortality During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Japan: Descriptive Analysis of National Health Statistics up to 2022. J Epidemiol. 2025 Mar 5;35(3):154-159. Epub 2025 Jan 31. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka H, Togawa K, Katanoda K. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mortality trends in Japan: a reversal in 2021? A descriptive analysis of national mortality data, 1995-2021.BMJ Open. 2023 Aug 31;13(8):e071785. [CrossRef]

- Kusunoki H. Current Status and Significance of Additional Vaccination with COVID-19 Vaccine in Japan-Considerations from Antibody Levels from Hybrid Immunity and Public Perceptions. Vaccines (Basel). 2024 Dec 15;12(12):1413. [CrossRef]

- Kusunoki H. COVID-19 and the COVID-19 vaccine in Japan—A review from a general physician’s perspective. Pharmacoepidemiology. 2023;2:188–208. [CrossRef]

- Alessandria M, Malatesta G, Di Palmo G, Cosentino M, Donzelli A. All-cause mortality according to COVID-19 vaccination status: An analysis of the UK office for National statistics public data.F1000Res. 2025 Feb 20;13:886. eCollection 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kakeya H, Nitta T, Kamijima Y, Miyazawa T. Significant Increase in Excess Deaths after Repeated COVID-19 Vaccination in Japan. JMA J. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Kusunoki H, Ohtani I, Miki Y. Problems in the Treatment of Common Fevers and Colds After the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Discussion of Typical Cases in Elderly COVID-19 Patients. Japanese Journal of Hospital General Medicine. 2025:21(2)in press.

- Ato D. The mRNA Vaccination Rate Is Negatively and the Proportion of Elderly Individuals Is Positively Associated With the Excess Mortality Rate After 2020 in Japan.Cureus. 2024 Jan 18;16(1):e52490. eCollection 2024 Jan. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).