Submitted:

10 March 2025

Posted:

11 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

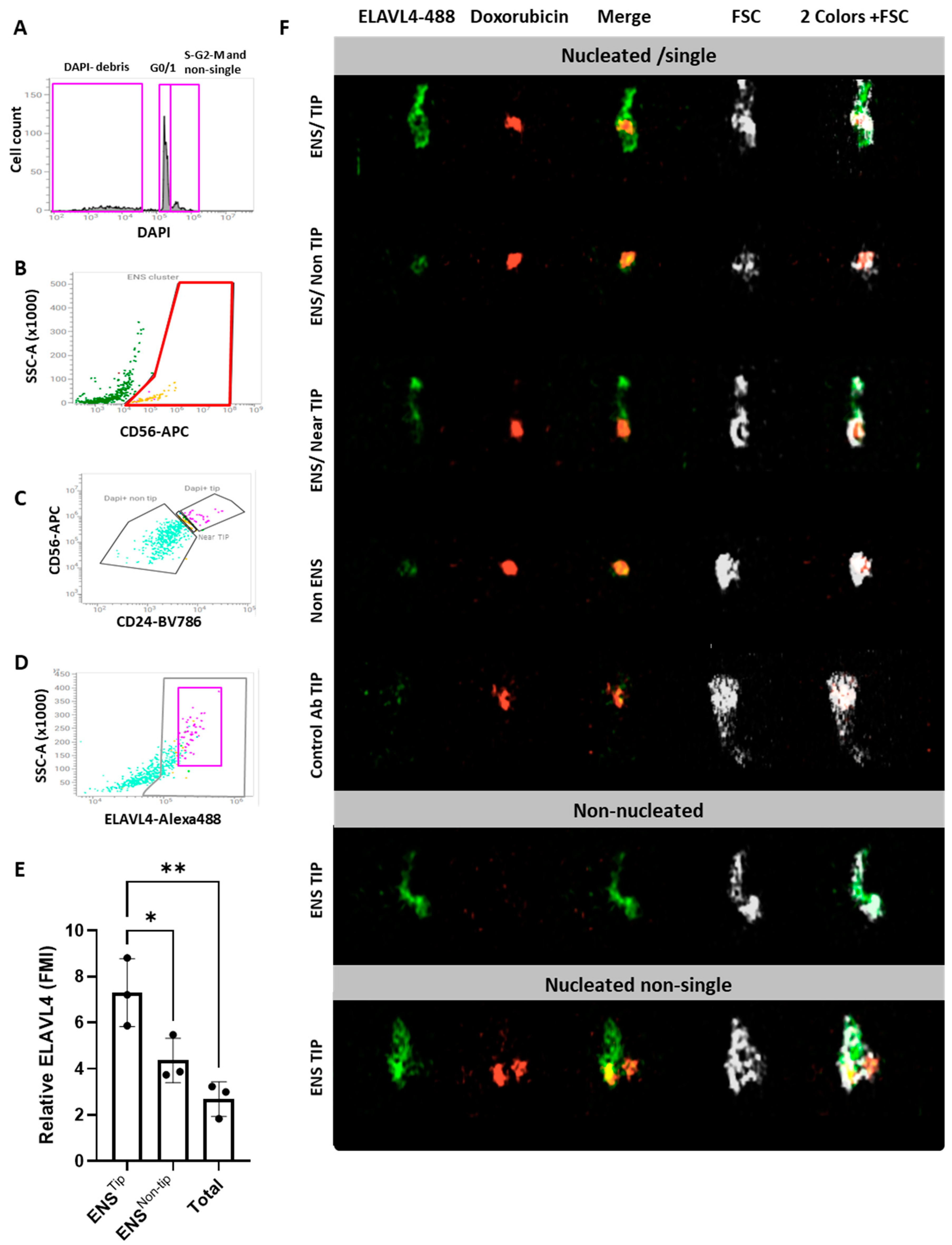

Isolation of neurons and glial cells from the enteric nervous system (ENS) enables ex-vivo studies, including analysis of genomic and transcriptomic profiles. While we previously reported a fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS)-based isolation protocol for human ENS cells, no equivalent exists for mice. As directly applying the human protocol to mouse tissue, resulted in low recovery of live ENS cells, we compared different protocols to optimize tissue dissociation of mouse colons. A 30-minute Liberase-based digestion showed optimal recovery of viable ENS cells, with CD56 and CD24 emerging as the most reliable markers to select and subdivide these cells. ENS identity was further validated by FACS using neuronal (TUBB3) and glial (SOX10) markers, and reverse transcriptase quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) on sorted fractions. Overall, the mouse ENS expression profile significantly overlapped with the human one, confirming that current dissociation protocols yield a mixed staining pattern of enteric neurons and glia. Nonetheless, using the imaging flow cytometer BD S8 FACS Discover, and ELAVL4 as a neuronal soma-associated marker, we observed enrichment of neurons, at the TIP of the CD56/CD24 population. In conclusion, we present here a protocol for high purity FACS-based isolation of viable enteric neurons and glial cells, suitable for downstream applications.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Mouse ENS Cells Are Successfully Isolated with the Human Protocol, but with Low Viability

2.2. New Dissociation Protocols for Isolation of Murine ENS Cells

2.2.1. New Dissociation Protocols and Gating Strategy

2.2.2. The Liberase-Based Protocol Increases Overall Viability and ENS Recovery from Mouse Colons

2.3. Validation and Subdivision of the ENS Cluster

2.4. CD56/CD24TIP Is Enriched in Neurons

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals and Intestinal Isolation

4.2. Dissociation of Mouse Colon Tissue

4.3. Intracellular and Extracellular Staining

4.4. Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting

4.5. Gene Expression Analysis

4.6. Quantification and Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gulbransen, B.D.; Sharkey, K.A. Novel functional roles for enteric glia in the gastrointestinal tract. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2012, 9, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, N.J.; Hu, H. Enteric nervous system: sensory transduction, neural circuits and gastrointestinal motility. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2020, 17, 338–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, R.K.; Hirano, I. The enteric nervous system. N Engl J Med 1996, 334, 1106–1115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Avetisyan, M.; Schill, E.M.; Heuckeroth, R.O. Building a second brain in the bowel. J Clin Invest 2015, 125, 899–907. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Holland, A.M.; Bon-Frauches, A.C.; Keszthelyi, D.; Melotte, V.; Boesmans, W. The enteric nervous system in gastrointestinal disease etiology. Cell Mol Life Sci 2021, 78, 4713–4733. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Graham, K.D.; López, S.H.; Sengupta, R.; Shenoy, A.; Schneider, S.; Wright, C.M.; Feldman, M.; Furth, E.; Valdivieso, F.; Lemke, A.; et al. Robust, 3-Dimensional Visualization of Human Colon Enteric Nervous System Without Tissue Sectioning. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 2221–2235 e2225. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Windster, J.D.; Sacchetti, A.; Schaaf, G.J.; Bindels, E.M.; Hofstra, R.M.; Wijnen, R.M.; Sloots, C.E.; Alves, M.M. A combinatorial panel for flow cytometry-based isolation of enteric nervous system cells from human intestine. EMBO Rep 2023, 24, e55789. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bondurand, N.; Southard-Smith, E.M. Mouse models of Hirschsprung disease and other developmental disorders of the enteric nervous system: Old and new players. Dev Biol 2016, 417, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McQuade, R.M.; Singleton, L.M.; Wu, H.; Lee, S.; Constable, R.; Di Natale, M.; Ringuet, M.T.; Berger, J.P.; Kauhausen, J.; Parish, C.L.; et al. The association of enteric neuropathy with gut phenotypes in acute and progressive models of Parkinson's disease. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 7934. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Baydi, Z.; Limami, Y.; Khalki, L.; Zaid, N.; Naya, A.; Mtairag, E.M.; Oudghiri, M.; Zaid, Y. An Update of Research Animal Models of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. ScientificWorldJournal 2021, 2021, 7479540. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Drokhlyansky, E.; Smillie, C.S.; Van Wittenberghe, N.; Ericsson, M.; Griffin, G.K.; Eraslan, G.; Dionne, D.; Cuoco, M.S.; Goder-Reiser, M.N.; Sharova, T.; et al. The Human and Mouse Enteric Nervous System at Single-Cell Resolution. Cell 2020, 182, 1606–1622 e1623. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Llorente, C. Isolation of Myenteric and Submucosal Plexus from Mouse Gastrointestinal Tract and Subsequent Co-Culture with Small Intestinal Organoids. Cells 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schonkeren, S.L.; Küthe, T.T.; Idris, M.; Bon-Frauches, A.C.; Boesmans, W.; Melotte, V. The gut brain in a dish: Murine primary enteric nervous system cell cultures. Neurogastroenterology & Motility 2022, 34, e14215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morarach, K.; Mikhailova, A.; Knoflach, V.; Memic, F.; Kumar, R.; Li, W.; Ernfors, P.; Marklund, U. Diversification of molecularly defined myenteric neuron classes revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing. Nature Neuroscience 2021, 24, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Windster, J.D.; Kakiailatu, N.J.M.; Kuil, L.E.; Antanaviciute, A.; Sacchetti, A.; MacKenzie, K.C.; Peulen-Zink, J.; Kan, T.W.; Bindels, E.; de Pater, E.; et al. Human Enteric Glia Diversity in Health and Disease: New Avenues for the Treatment of Hirschsprung Disease. Gastroenterology 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Components | Manufacturer | Cat. No. | Final concentration | Dissociation medium1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMEM/F12 | Gibco | 11320-074 | N/A | A & B & C |

| HEPES (1M) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 15630106 | 10 mM | A & B & C |

| DNase I | Sigma | 11284932001 | 200 µg/ml | A & B & C |

| Dispase | Gibco | 17105-041 | 0.25 mg/ml | A |

| Dispase | Gibco | 17105-041 | 1 mg/ml | B |

| FBS | Capricorn Scientific | FBS-12A | 5% | B |

| Collagenase II | Gibco | 17101-017 | 3mg/ml | A |

| Collagenase I | Gibco | 17101-015 | 1 mg/ml | B |

| Liberase | Roche | 5401119001 | 0.5 mg/ml | C |

| Fluorophore | Lasers | BP filter (nm) | LP filter (nm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hoechst/DAPI/BV421 | 405 nm | 450/40 | - | ||

| FITC/A488/Cycle Green | 488 nm | 530/30 | 502 | ||

| PE | 561 nm | 582/15 | - | ||

| APC | 633 nm | 660/20 | - | ||

| Alexa 700 | 633 nm | 730/45 | 690 | ||

| BV605 | 405 nm | 610/20 | 570 | ||

| BV786 | 405 nm | 780/60 | 750 | ||

| BV510 | 405 nm | 530/30 | 502 | ||

| Primary antibody | Reactivity1 | Fluorochrome | Supplier; Cat.# | Dilution | Application |

| CD56 | H | APC | Biolegend, 362504 | 1:40 | FACS Aria |

| CD90 | H | Alexa 700 | Sony, 2240600 | 1:40 | FACS Aria |

| CD24 | H | PE | BD, 555428 | 1:20 | FACS Aria |

| CD31 | H | BV421 | Biolegend 564089 | 1:0 | FACS Aria |

| CD45 | H | BV421 | Biolegend 304031 | 1:40 | FACS Aria |

| CD24 | M | PE | Biolegend; 101807 | 4 µg/ml | FACS Aria |

| CD24 | M | BV786 | BD 744470 | 4 µg/ml | FACS Aria |

| CD24 | M | BV605 | Biolegend 101827 | 4 µg/ml | FACS Aria |

| CD56 | M | APC | R&D systems; FAB2408A-100UG | 4 µg/ml | FACS Aria |

| CD90 | M | Alexa 700 | Biolegend; 105320 | 4 µg/ml | FACS Aria |

| CD45 | M | BV421 | Biolegend; 103133 | 4 µg/ml | FACS Aria |

| CD31 | M | BV421 | Biolegend; 102423 | 4 µg/ml | FACS Aria |

| TER119 | M | BV421 | BD 563998 | 4 µg/ml | FACS Aria |

| TUBB3 | M/H | Alexa 555 | BD 560339 | 1 µg/ml | FACS Aria |

| TUBB3 | M/H | Alexa 488 | Biolegend (Covance) A488-435L | FACS Aria | |

| SOX103 | M/H | Unconjugated | ThermoFisher; 10422-1-AP | 0.4 µg/ml | FACS Aria |

| ELAVL4 | M/H | CL 488 | Proteintech, 67835-1-Ig | 1 µg/ml | FACS Discovery S8 |

| Control Mouse IgG | - | Unconjugated | Santa Cruz, sc-2025 | 1 µg/ml | FACS Discovery S8 |

| Control Rabbit IgG | - | Unconjugated | Biolegend, 910801 | 0.4 µg/ml | FACS Discovery S8 |

| Secondary antibody | Reactivity | Supplier; Cat.# | Dilution | FACS Discovery S8 | |

| Anti-mouse | Cy3 | Jackson; 715-165-150 | 1:200 | FACS Discovery S8 | |

| Anti-rabbit | Rabbit IgGs | Alexa 568 | ThermoFisher; A10042 | 1:200 | FACS Discovery S8 |

| Goat anti-rabbit (Fab) | Rabbit IgGs | PE | Jacksonimmuno; 111-117-008 | - | FACS Discovery S8 |

| Donkey anti-mouse (Fab) | Mouse IgGs | Alexa 488 | Jacksonimmuno; 715-547-003 | - | FACS Discovery S8 |

| Nuclear staining | |||||

| Dye Cycle™ Green | - | - | Termofisher, V35004 | 1:40002 | FACS Aria/ FACS Discovery S8 |

| Doxorubicin | - | - | Pharmachemie, 51.223.805 | 0.4 µg/ml2 | FACS Discovery S8 |

| DAPI | - | - | Sigma Aldrich | 1 µg/ml2 | FACS Aria |

| Gene | Forward primer (5→3) | Reverse primer (5→3) |

|---|---|---|

| Tubb3 | CAGATAGGGGCCAAGTTCTGG | GTTGTCGGGCCTGAATAGGT |

| Elavl4 | TCAGACTCCAGACCAAAACCA | TGATGCGACCGTATTGAGAGA |

| Sox10 | GCAAGACACTAGGCAAGCTC | CCTCTCAGCCTCCTCAATGA |

| Ncam1 | CACCATCTACAACGCCAACA | GGGGTTGGTGCATTCTTGAA |

| β-Actin | CTCCACCAGTCTTAAATGGA | AACATAACAACTCTGCAGTCA |

| Gapdh | ACTTTGGCATTGTGGAAGGG | ACAGTCTTCTGGGTGGCAGTG |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).