1. Introduction

Vegetation phenology is a sensitive indicator of environmental factors change. Phenological change can reflect physiological condition of the plant itself [

1]. Phenophases refer to the times during which plant growth, development, and activities respond to seasonal variations, which represents some of the most prominent biological characteristics influenced by external conditions [

2]. Meanwhile, various plant organs such as leaf, flower, stem, root have been identified as bioreactor. Among these plant organs, leaf phenology and flowering phenology are critical traits within the field of reproductive biology research [

3]. Leaf undergoes various life processes such as bud emergence, growth, and expands, while flower engages in budburst, pollination, dispersal, and selection of suitable habitats for colonization. In the context of global warming, advanced leaf and flowering phenology in trees and shrubs have been generally reported by previous studies, and this phenomenon was more significantly in trees and shrubs compared to herbaceous plants [

4], indicating that woody species exhibit a more rapid response ability to external environmental changes. Furthermore, shifts in phenology may affect individual survival rates and population dynamics while potentially leading to differences in reproductive success.

Phenological alteration also provide feedback to the environment condition, various environmental factors have been identified as influencing vegetation phenology, including temperature [

5], photoperiod [

6], moisture [

7]. For humid temperate zones, a comprehensive study demonstrated that three primary factors exert considerable influence on the phenology of dominant tree species within forests: low winter temperatures, light and temperature[

8]. In mid-high latitude regions of the Northern Hemisphere, plant phenology responds more swiftly to temperature fluctuations [

9], indicated that the response priorities of plants to phenological influencing factors vary across different climate belts. Besides, variations in seasonal temperatures result in marked differences between spring and autumn phenology [

10]. For autumn phenological events, distinct dormancy stages possess unique requirements regarding temperature thresholds and accumulated chilling hours [

11]. Further, the various climate conditions impose selection pressures on plants, compelling them to adopt diverse ecological adaptation strategies that facilitate their growth and development. These strategies are particularly evident in alterations of the morphological and physiological traits of plants [

12], while phenophases variations result in changes across different organs' growth and development. Phenophases serves as a crucial link between the physiological characteristics of plants and environmental fluctuations. Understanding the relationship between phenophases and environmental factors is essential for elucidating the ecological adaptation strategies employed by species, especially in narrowly distributed species. On the basis, plant’s coping strategies to varying climatic conditions, and disturbances is clarified. Similarity, the accuracy of phenological models across various habitats will also be improved [

13,

14].

In previous study, there is a notable deficiency of long-term and detailed observational data on individual species. Although there have been studies using many target species, but the type of phenophases was also limited [

15,

16]. Betulaceae plants are acknowledged as valuable forest resources in their native distribution areas. For example,

Betula platyphylla, a highly adaptable dominant tree species found in the natural secondary forests of Northeast China, exhibits relative synchrony with various other tree species across different phenological rhythms [

17], suggests that habitat conditions impose natural selection pressures on internal biological rhythms. Moreover, its phenology have been consistently conducted, extensive cultivation throughout numerous regions in China [

18,

19].

B. microphylla as a tall tree within the

Betula genus of the Betulaceae family [

20], has a restricted distribution solely to Xinjiang, China. Xinjiang is situated in a high-latitude region characterized by significant diurnal temperature variations. Temperature serves as the primary factor influencing crop production and vegetation survival in this area, rendering it an important focus for research concerning arid and semi-arid regions of Northwest China. Additionally, diverse landform types have fostered various habitat types. Through years of field investigations conducted by our team, we have identified that

B. microphylla thrives in habitats such as plain wetlands, coniferous forests on slopes, river valleys, and marsh meadows. Hence, it has thus emerged as an essential natural forest resource within Xinjiang. However, no relevant reports have been found its phenological characteristics. In our study, we conducted long-term field observations on a total of 18 phenophases concerning leaf, flower, and fruit organs across the four seasons of the

B. microphylla population naturally distributed in the Mushroom Lake Plain Wetland at the southern margin of the Junggar Basin from 2010 to 2019. The specific start and end times of these phenophases were determined, interannual and seasonal variation trends were analyzed, and meteorological data were collected to investigate the relationship between phenophases and temperature. In summary, our aims were (1) to clarify the seasonal pattern of phenology in

B. microphylla, (2) to find meteorological factors influence the phenophases of

B. microphylla, (3) to understand ecological adaptation strategies manifest in

B. microphylla under varying conditions from a phenological perspective.

4. Results

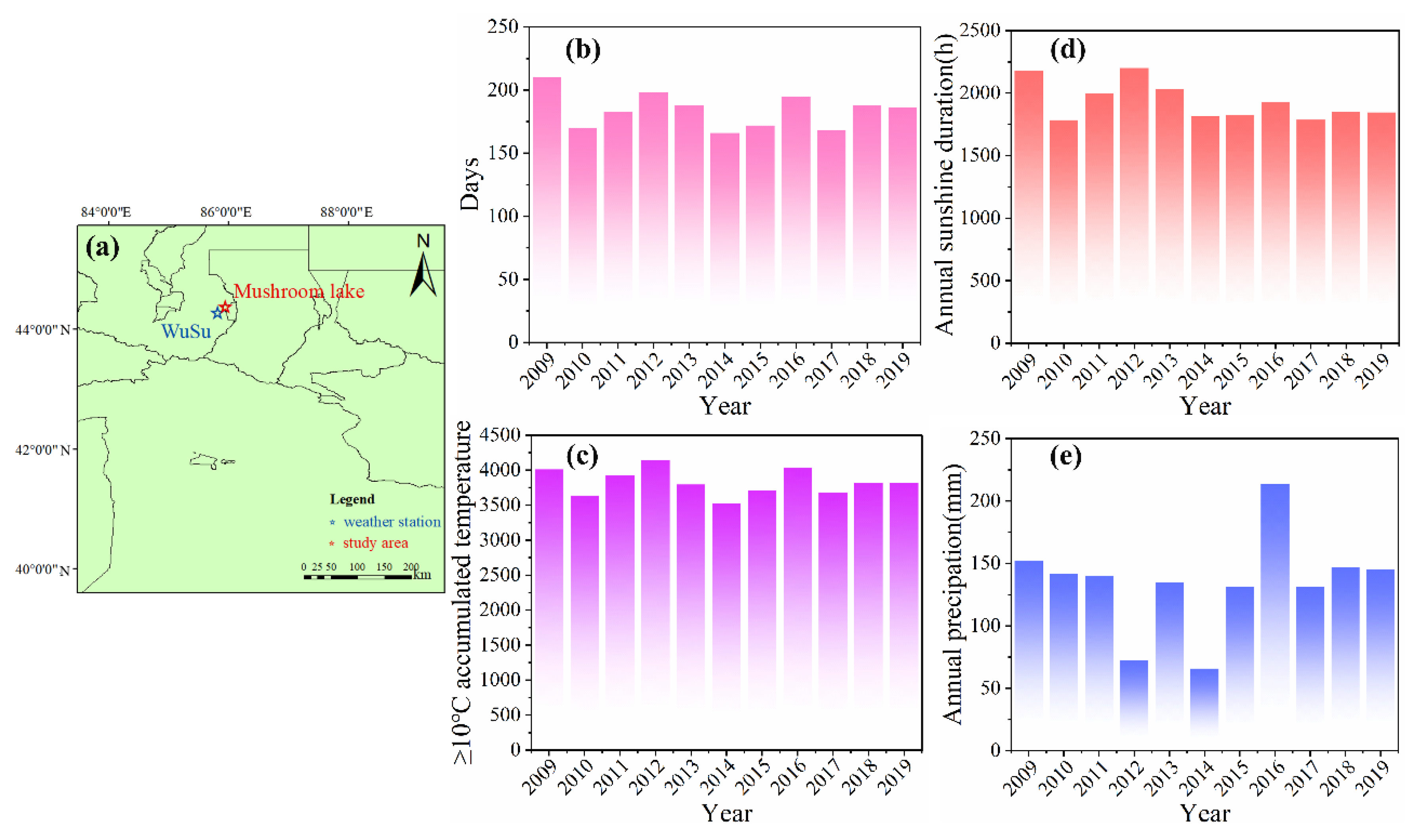

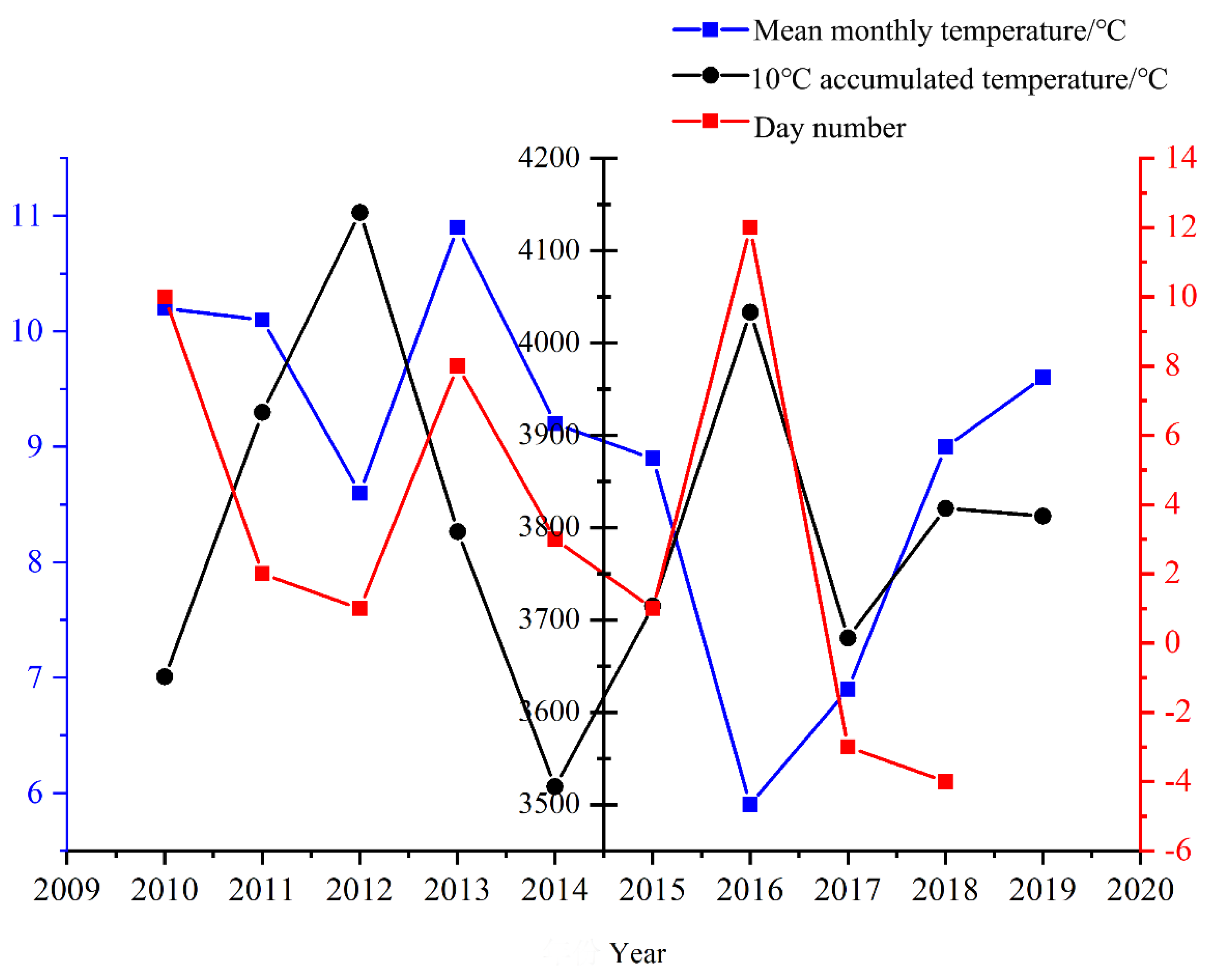

4.1. Accumulated Temperature and Sunshine Hours Across Different Years

The start and end dates of the ≥10℃ accumulated temperature across different years exhibit considerable variation, as do the corresponding accumulated temperature values. When classifying climatic year, 2012 stands out as a relatively warm year, with the initiation date for the ≥10℃ accumulated temperature recorded on March 31st. The duration between the start and end dates was 198 days, ranking second only to the highest value (210 days) observed among all studied years. Furthermore, this year experienced an impressive total accumulated temperature of ≥10℃ amounting to 4141.3℃, despite having an annual precipitation of merely 72.6mm. Similarly, another notably warm year, 2016, the start date for the ≥10℃ accumulated temperature occurred even earlier than any other year within the ten-year observation period, specifically on March 24th. The interval from start to end lasted for 195 days, while annual precipitation reached its peak among all ten years at 213.4mm. In 2014, the latest starting point for ≥10℃ accumulating temperatures, was recorded on April 26th, this resulted in a shorter duration at just 166 days and yielded the lowest ≥10℃ accumulated temperature at only 3519.5℃. Additionally, precipitation levels in 2014 were also found to be minimal compared to other observed years at just 65.8mm. In summary, there exists a significant positive correlation between the values of ≥10℃ accumulated temperatures and the number of days spanning from their respective start to end dates over this study period. Notably, an early or late start date for ≥10℃ accumulated temperatures correlates with higher or lower annual precipitation levels respectively.

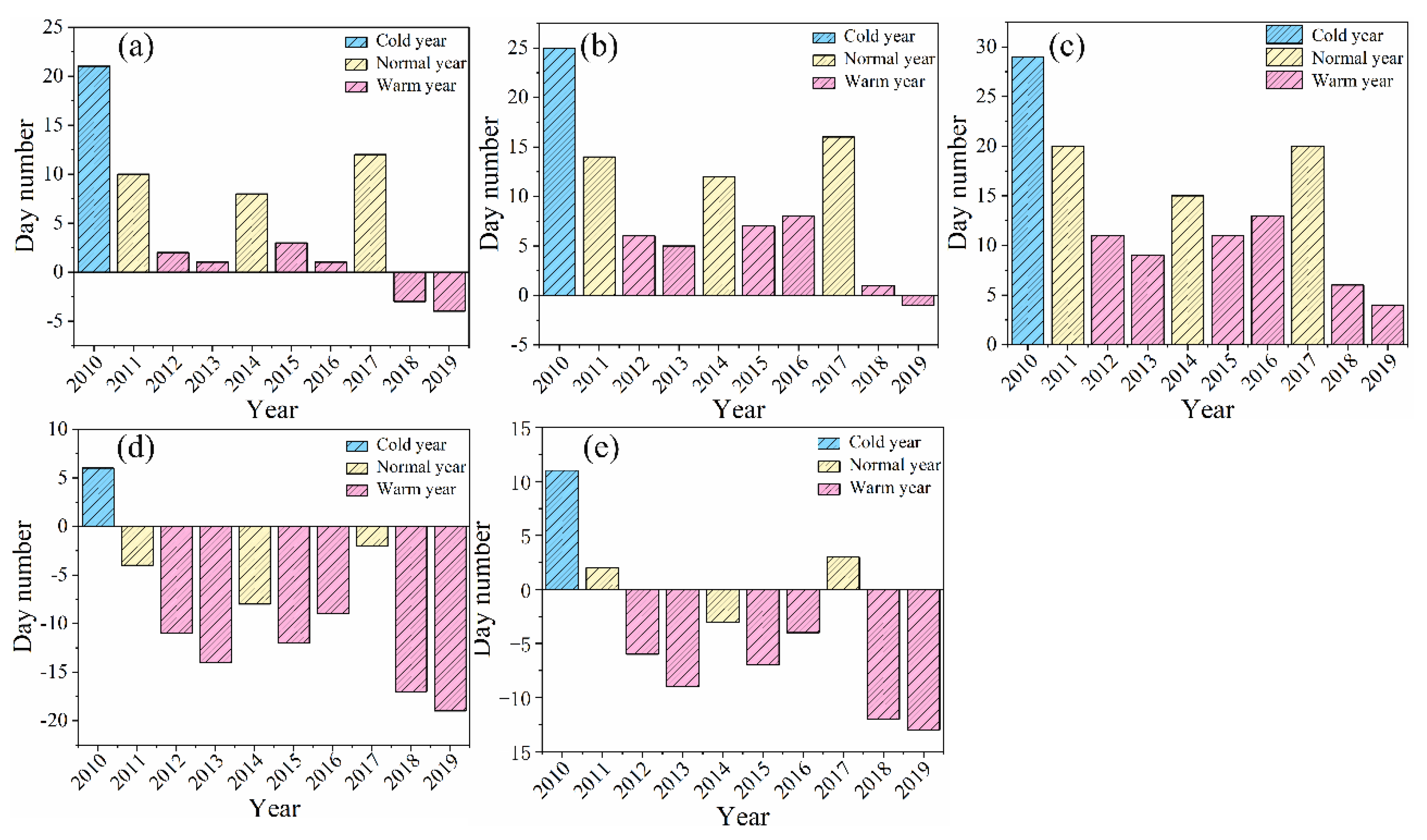

4.2. The Leaf Phenology of B. microphylla

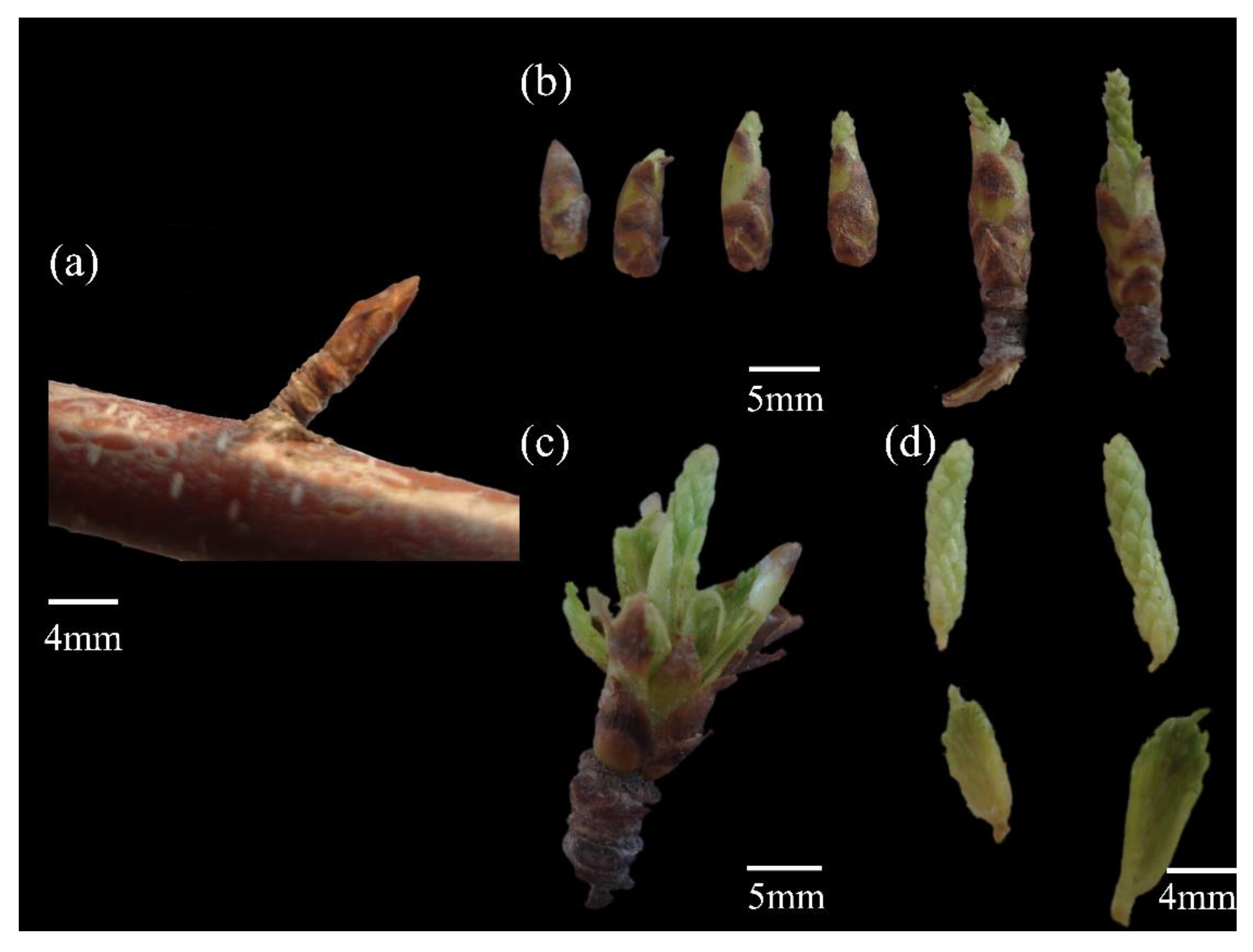

Based on the observational data collected by our team, the terminal and axillary buds of

B. microphylla begin to sprout in Mid-April. The emergence of fresh, green young leaf at the apex of the leaf buds indicates a successful transition into the young leaf stage. Both the leaf flush stage and the young leaf stage demonstrate favorable responses in both cold and warm years. Although average temperatures from March to April may meet criteria for a warm year (

Figure 3.), a later onset date for ≥10℃ accumulated temperatures compared to previous years can lead to delays in both leaf flush and young leaf stage (as observed in 2014). Moreover, sudden weather events represent an external factor that significantly influence plant phenology. In 2014, precipitation levels plummeted to their lowest recorded value of 65.8 mm among all observed years, coinciding with a strong cold front that swept across Xinjiang, this was accompanied by widespread rain, snow, fresh gale, sandstorm, abrupt cooling event, and frost conditions. As a result, both leaf flush and young leaf stages for

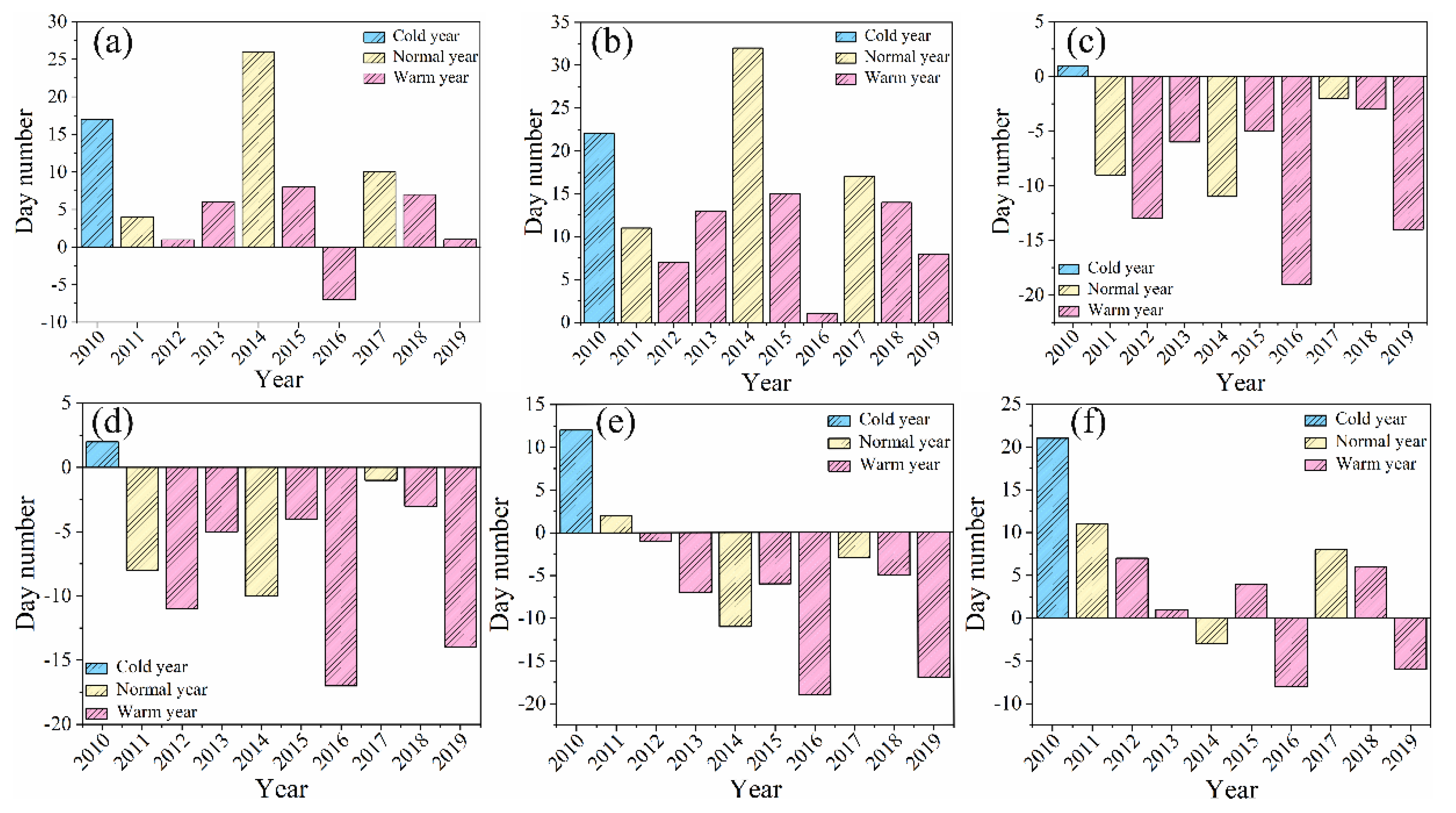

B. microphylla were markable delayed when compared to other typical years (such as 2011 and 2017) within our observation timeframe. Immediately after, approximately nine days later than usual marked the beginning of the leaf unfolding stage, which lasts roughly fifty days. It is noteworthy that leaf unfolding stage tends to be postponed in colder years, compared to normal or warmer years. During warm years such as 2013 and 2015, there was no significant advancement in leaf unfolding stage when juxtaposed with adjacent normal years. A comparative analysis revealed that average temperatures played a crucial role, April's average temperature in 2013 was recorded at 14.1℃, 2℃ lower than that of its preceding year. Similarity, low average temperature were noted for April 2015 at just 13.5℃, a decrease of 7.1℃ from those experienced in April 2014. These findings underscore that specific changes in leaf phenology continue to exhibit a high degree of synchrony with monthly average temperature fluctuations.

The synthesis of chlorophyll involves a series of enzymatic reactions, with the optimal temperature ranging from 20℃ to 30℃. The leaf mainly absorbs blue purple light and appear green. In addition, other types of pigments are present in plants, such as lutein and carotenoids, an increase in temperature not only accelerates the pigment synthesis process but also leads to the decomposition of certain pigments, thereby revealing the colors of other pigments. From July to August, the leaf edges of B. microphylla begin to turn yellow, marking the onset of the leaf yellowing stage, which lasts approximately 20 days. The causes behind phenological fluctuations are multifaceted. Firstly, the average temperature in August for both 2013 (22.7℃) and 2015 (22.6℃) were indicative of warmer years. Conversely, August 2014 experienced an average temperature significantly lower at just 16.3℃ during a regular year. So, the earlier onset of the leaf yellowing stage in both 2013 and 2015 compared to that in 2014 may be attributed to various factors including pest infestations and disease outbreaks. Secondly, during these warmer years, specifically in 2013 and 2015, the total hours of sunshine recorded were notably higher at 2031.2h and 1825.3h respectively when compared with only 1813.4h observed in 2014. Under cooler temperature, leaf photosynthesis within B. microphylla is inhibited, to trigger non-photochemical quenching wherein chlorophyll undergoes decomposition as a means to minimize photosynthetic loss. Thirdly, at lower temperatures chlorophyll molecules become increasingly fragile and more susceptible to damage. The reduced average monthly temperatures coupled with fewer sunlight hours experienced in August 2014 resulted in diminished chlorophyll content along with functional impairment, consequently leading those leaf into an earlier transition into their leaf yellowing stage than observed during other years. In 2013 and 2015, the relatively favorable temperatures facilitated a greater accumulation of chlorophyll in the leaf, leading to a delayed onset of the leaf yellowing stage. The leaf of B. microphylla began to abscise in Mid-September, with nearly all leaf having fallen by the end of October. Consequently, the growth phenology of B. microphylla, which spans approximately 200 days throughout the year, comes to an end.

4.3. The Phenology of Female Inflorescences of B. microphylla

The inflorescence type of

B. microphylla is a catkin, and it is classified as a monoecious plant. Ensuring the consistency of pollen release timing is crucial for the efficient completion of pollination in monoecious species. Consequently, the female inflorescence, serving as the reproductive organ for one growing season, must maintain a relatively rapid growth rate. We observed that various life processes associated with female inflorescences, such as budburst, elongation, shaping, and the formation of both young and mature fruiting structures, all occurred successively from mid-April to late May. As illustrated in

Figure 4, there was a significant delay in the phenology of female inflorescence budburst to young fruit stage until late April during colder years. In contrast, this process advanced to varying degrees during warmer years compared to adjacent normal years. Notably, in 2013 and 2015, delays were recorded which may have been influenced by average or accumulated temperatures in April. By conducting linear regression analysis on monthly average temperature data alongside phenological day sequences (

Figure 5), we found that during dormancy release stage when

B. microphylla experienced high accumulated temperatures, the budburst for female inflorescences was delayed due to insufficient low-temperature accumulation (notably observed in 2010, 2013, and 2017). Furthermore, when monthly average temperatures remained approximately consistent over multiple years (specifically from 2017-2019), early budburst of female inflorescences was noted. This indicates that as a reproductive organ functioning within an annual cycle it responds positively to stable interannual variations in monthly average temperature. Finally, part of the accumulated temperature acquired by these plants contributes towards breaking dormancy, thus in certain years characterized by elevated accumulated temperature values some energy is allocated toward promoting meristematic development leading to an earlier onset of female inflorescence budburst (2012 and 2016). However, in years marked by lower accumulated temperature above process tends to be delayed resulting in postponed entry into germinative phenology ( 2015).

Following the pollination of male flowers, the female inflorescences undergoing a transformation to fruit clusters. After receiving adequate sunlight and absorbing substantial nutrients, these female fruit-clusters reach maturity. The samaras align systematically, upon accumulating sufficient temperature exposure, begin to flutter down with the wind, thus completing the process of seed dissemination. The above stages are referred to as the maturity and abscission stage of the female fruit-clusters. Due to the relatively synchronized timing of life activities among female flowers, they tend to enter the maturity and fruit abscission stage later in colder years or when monthly average temperatures are lower during corresponding months (

Figure 5.). In warmer years such as 2014 (with an average temperature of 24.5°C in June), there is an acceleration in fruit shedding leading to an earlier onset of the fruit abscission stage. In summary, the influence of monthly average temperature on both the maturity and abscission stages of female fruit-clusters aligns consistently with previous observations regarding phenological variations within these clusters.

4.4. The Phenology of Male Inflorescences of B. microphylla

B. microphylla is generally a wind pollinated plant, small nut with membranous wings. Its male inflorescences serve as reproductive organs that endure through the winter months. Moreover, the phenological development of these inflorescences begins in late May, with flowering not occurring until April of the following year. By mid to late April, the flower buds initiate budburst, these buds crack and elongate within 4-5 days, followed by a peak period of pollen dispersion lasting 2-3 days (

Figure 6.). Thus, the entire process of pollen dissemination is completed within 8-10 days. Overall, the variations in flowering phenology (

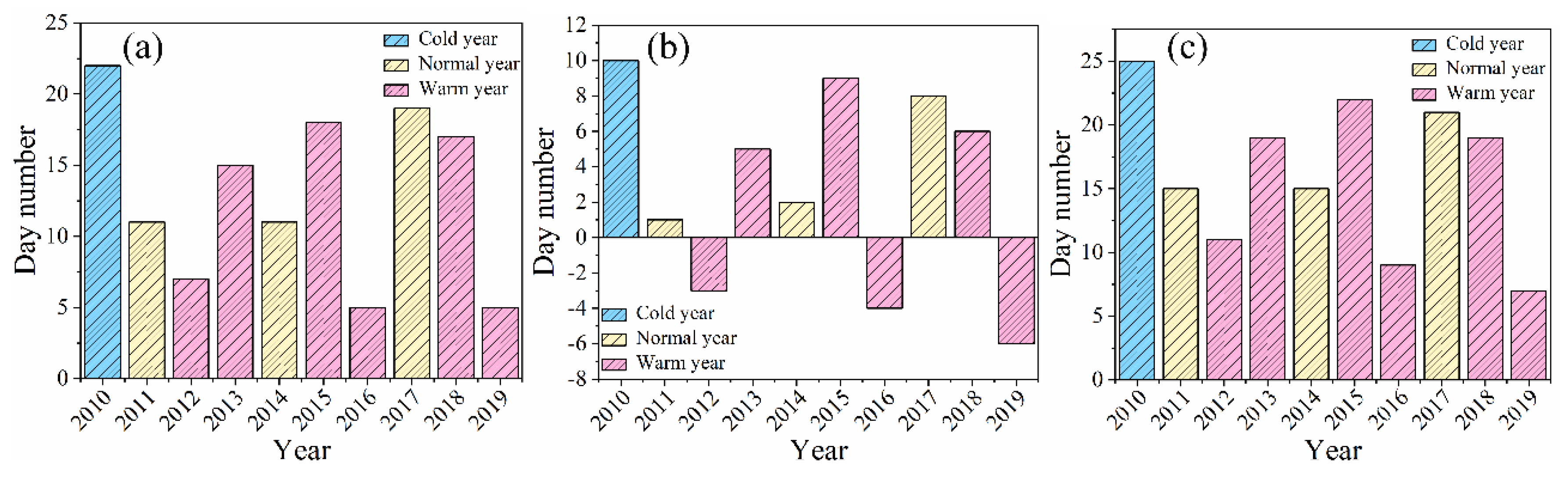

Figure 7.), specifically during the budburst stage, elongation stage, and pollen dispersion stage are closely associated with climatic classifications such as warm years, cold years, and normal years. In warmer years, this phenology occurs significantly earlier than in normal years, conversely, it is delayed during colder years. As May approaches, male inflorescences enter their budburst stage, a pattern that mirrors the developmental timeline from budburst to young fruit stage observed in female inflorescences. Following pollen dispersion, male flowers begin to wither until they eventually abscise. The withering process may be postponed only during colder years when average monthly temperatures are lower. Otherwise, it typically concludes by mid to late April in other conditions. Elevated temperatures tend to further expedite both withering and abscission processes for male inflorescences. In June, rising temperatures stimulate growth phenology among male inflorescences, the elongation stage commences currently. Over nearly three months' duration thereafter, these organs continue to extend until they reach maturity by early September. Notably lower average monthly temperatures recorded in adjacent years can also contribute to relatively later elongation stage observed during warmer seasons such as those experienced in 2013 and 2015.

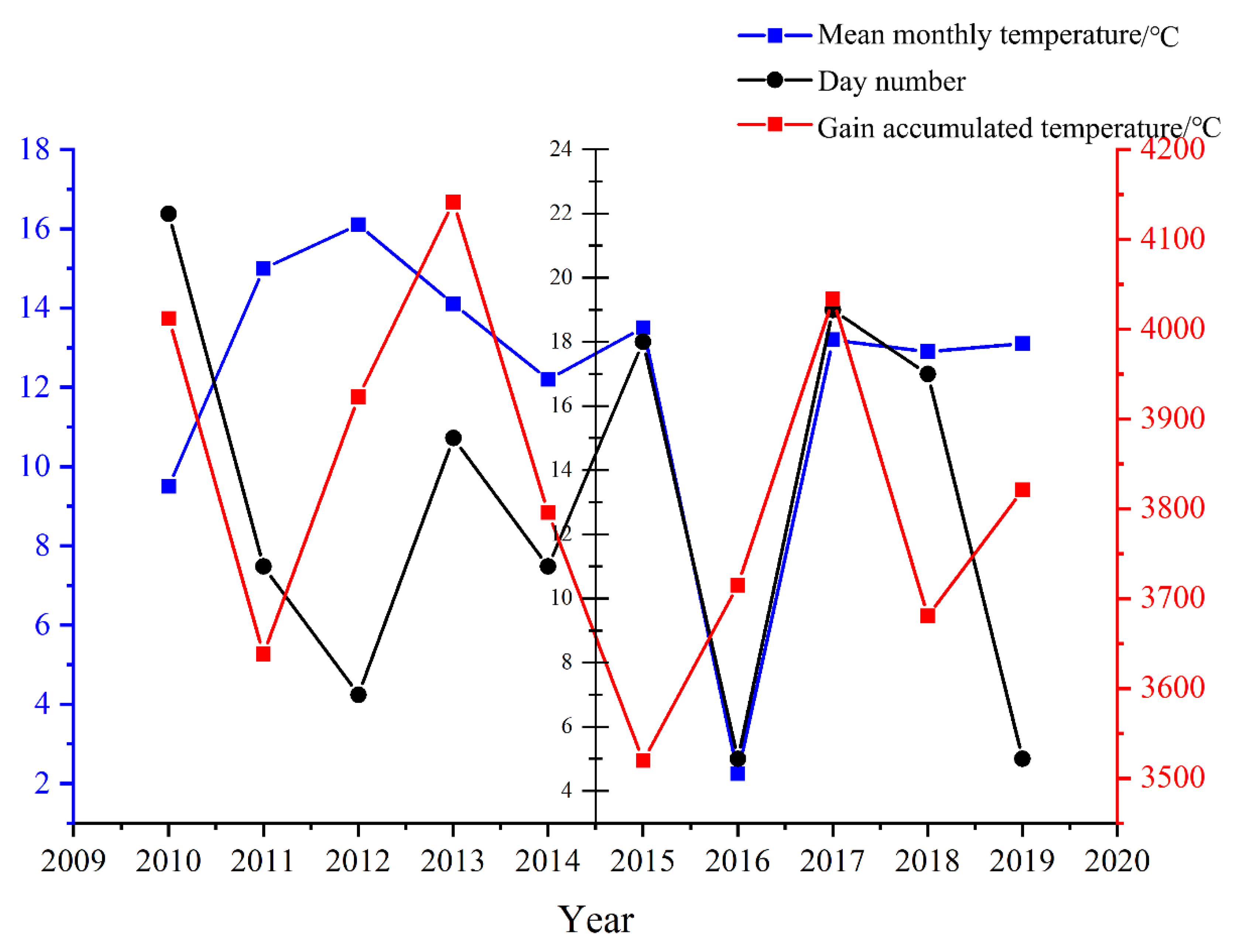

When the male inflorescence reaches a specific length, width, and defined shape, it enters a critical phase of growth phenology known as the dormancy stage at the end of October. During this time, the organism suspends complex life activities and accumulates energy for the budburst of flower buds in the following year. Successfully navigating this dormancy stage is an essential prerequisite for both the budburst of flower buds in the subsequent year and the timely onset of the next flowering phenology. Firstly, by comparing the day number of male inflorescence budburst phenology observed from 2010 to 2019 with both the monthly average temperature during its dormancy stage from the previous year and ≥10℃ accumulated temperatures (

Figure 8), it becomes evident that there is a strong correlation between these factors. Specifically, variations in monthly average temperature during dormancy are closely linked to timing patterns in subsequent years' budburst stages. Secondly, ≥10℃ accumulated temperatures provide a complementary effect on mitigating low values recorded for monthly average temperatures during male inflorescence dormancy. This relationship is particularly notable between 2016's dormancy stage and 2017's budburst stage. In this instance, while January through March averages indicated a lower mean temperature of 5.9℃ during dormancy in 2016 compared to 8.9℃ recorded for similar months in 2015, an impressive total heat accumulation reached approximately 4033.4℃ over a span of just under seven months (195 days). However, the release of physiological dormancy in plants necessitates a certain accumulation of low temperatures. The inadequate accumulation of low temperatures in 2016 resulted in a delay in the budburst stage of male inflorescence during the spring of 2017. Ultimately, there exists a threshold value for the complementary effect between ≥10°C accumulated temperatures and the monthly average temperature throughout the dormancy stage of male inflorescence. In 2017, the monthly average temperature during this dormancy stage of male inflorescence was recorded at 6.9°C, while the ≥10°C accumulated temperature amounted to 3680.6°C. In contrast, although both the monthly average temperature and ≥10°C accumulated temperature increased in 2018 compared to 2017, no complementary relationship was observed that year. However, this complementary relationship re-emerged in subsequent years, thus indicating that there is indeed a minimum threshold necessary for such an interaction between accumulated temperatures and monthly average temperatures to occur. It is only when the monthly average temperature meets or exceeds this minimum threshold that this complementary effect becomes evident.

6. Conclusions

Based on nearly 10 years of phenology observations, we analyzed the relationship between temperature and 18 phenophases of B. microphylla located in the southern margin of the Junggar Basin and have conducted a systematic study on the ecological adaptation strategies of B. microphylla to seasons variation. Our study also revealed the differences between the phenological response of warmer years and colder years to temperature. The results indicated that (1) The seasonal phenological patterns of B. microphylla exhibit distinct variations. Moreover, the types of phenophases across different seasons remain relatively stable while their durations show minimal variation. (2) The primary influencing factor for phenological variations is the monthly average temperature during specific phenological events. Throughout the year, leaf phenology is predominantly influenced by the monthly average temperature as well as the differences in climatic year. In spring, the budburst of female inflorescences is associated with accumulated temperature, the type of budburst stage, and energy allocation stages. Conversely, high temperatures experienced during plant’s dormancy stage may delay the budburst of male inflorescences. (3) A comprehensive and scientific theory regarding ecological strategies for B. microphylla has been clearly articulated based on trait analysis and climatic data. The impact of climate on the phenology of B. microphylla can be attributed to five key strategies: a "multiple low-temperature requirements" strategy for inflorescence budburst; a "preceding leaf growth" strategy concerning inflorescences; a "quantity victory" strategy for male inflorescences; a "long dormancy" strategy applicable to male inflorescences under elevated autumn temperatures; and a "spatial dislocation" strategy pertaining to both male and female inflorescences. Xinjiang, located in the northwest and remote from the ocean, exhibits an exceptionally intense continental climate characterized by terrains such as grasslands and deserts. Currently, the rational exploitation, utilization, and protection of native natural forest resources in Xinjiang hold paramount importance. Our findings will effectively provide valuable insights into research on the response of B.microphylla to climate change. We hope to draw attention to the significance of narrow-distributed endemic species through a case study of B. microphylla phenology and adaptation strategies.