Submitted:

11 March 2025

Posted:

12 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Isolation and Cultivation

2.2. DNA Extraction

2.3. Genome Sequencing and Assembly of Pseudarthrobacter sp. So.54

2.4. Phylogenetic Analysis

2.5. Genomic Bioinformatics Analysis

3. Results

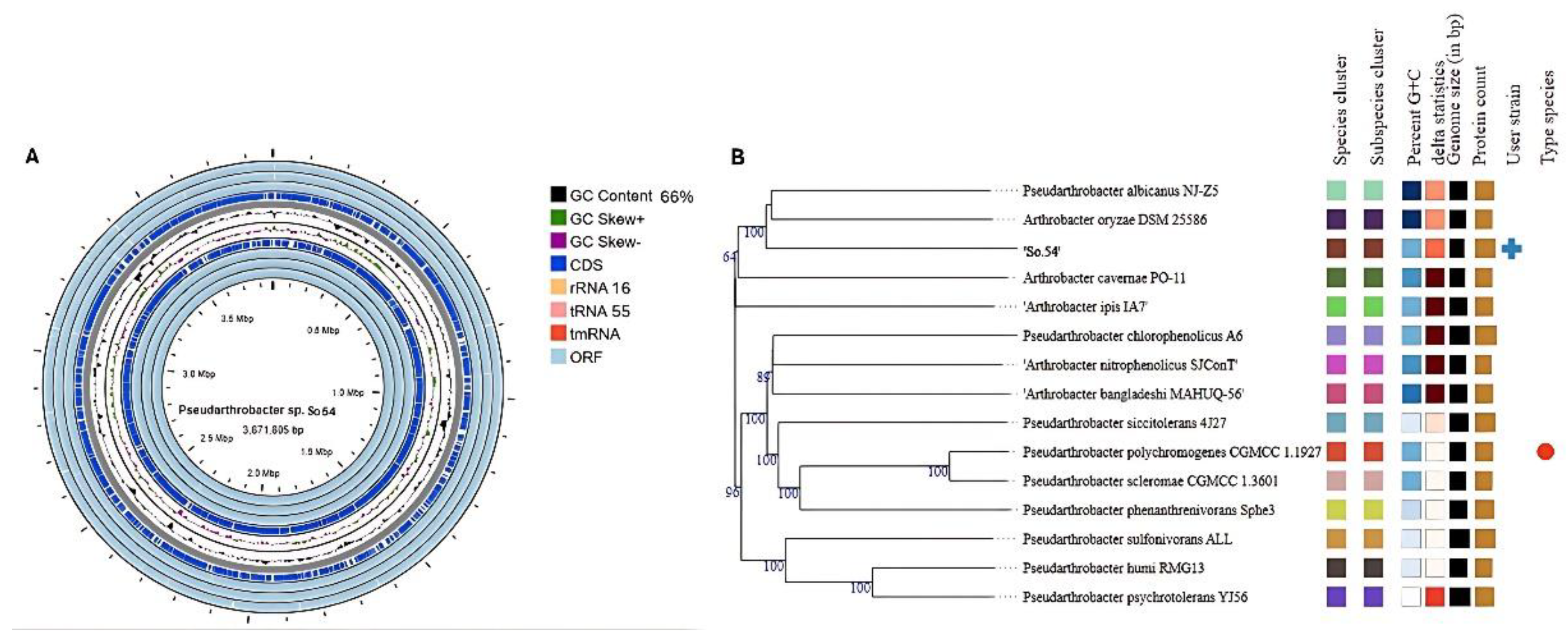

3.1. General Genomic Features of Strain So.54

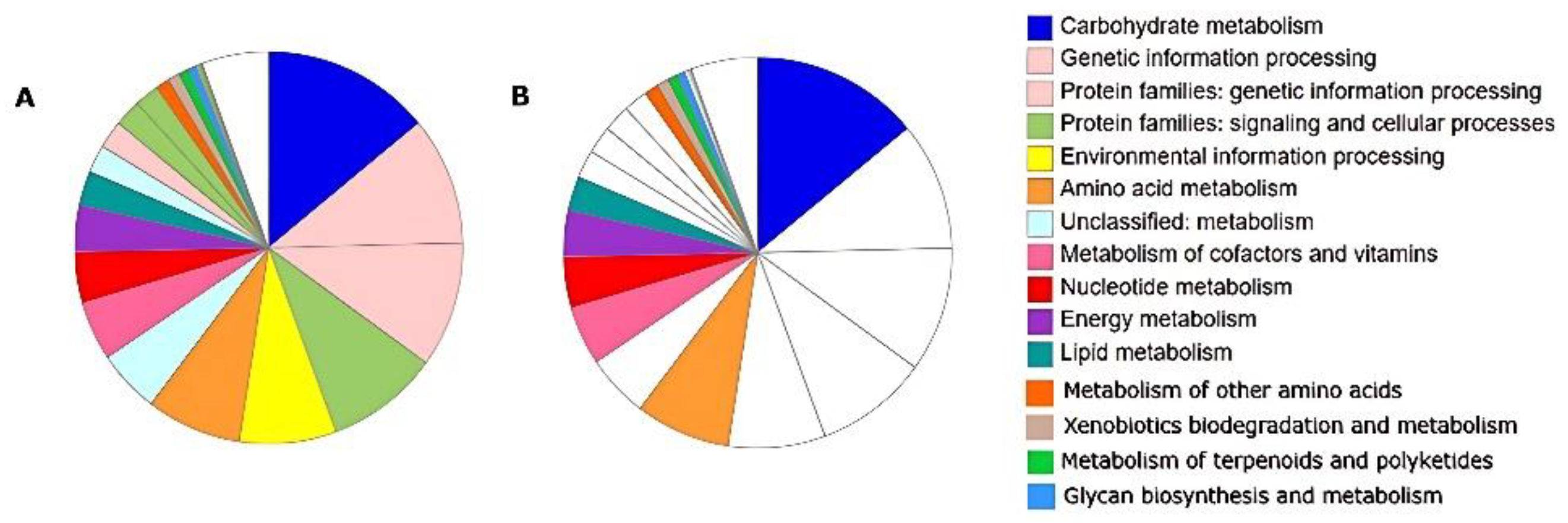

3.5. Metabolic Features and Genes Related to Environmental Adaptation

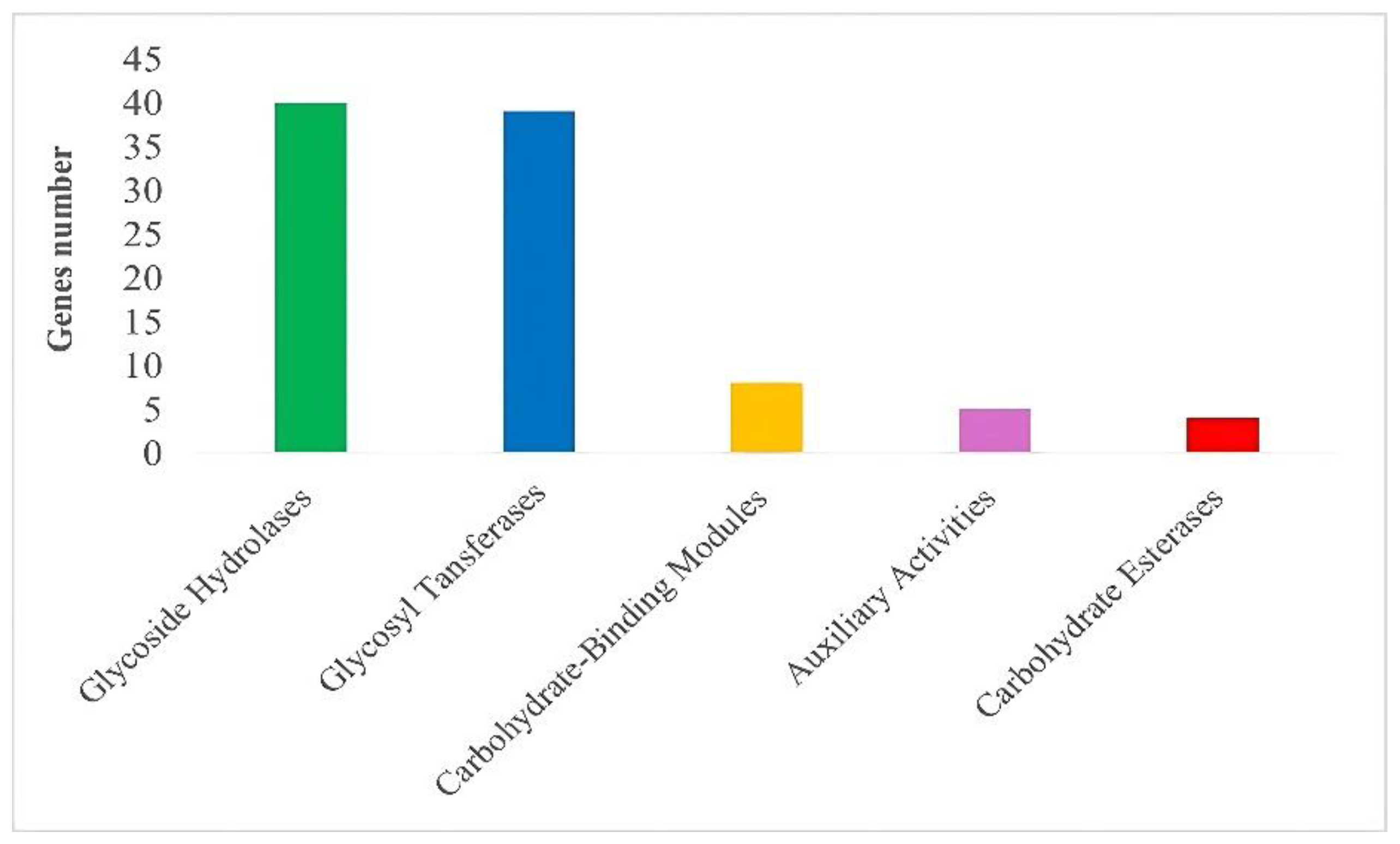

3.5.1. CAZyme Analysis

| CAZyme group | Enzyme activity | Genes | EC Number | Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase | glgC | EC 2.7.7.27 | 1 |

|

GT5 |

Predicted glycogen synthase, ADP-glucose transglucosylase, Actinobacterial type | glgA | EC 2.4.1.21 | 2 |

| NDP-glucose---starch glucosyltransferase | waxy | EC 2.4.1.242 | 2 | |

|

GH13 CBM48 |

1,4-alpha-glucan (glycogen) branching enzyme, GH-13-type | glgB | EC 2.4.1.18 | 3 |

| - | UTP--glucose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase | galU | EC 2.7.7.9 | 1 |

| GT3 | Glycogen synthase | gys | EC 2.4.1.11 | 1 |

| GT35 | Glycogen phosphorylase | glgP | EC 2.4.1.1 | 3 |

| - | Phosphoglucomutase | pgm | EC 5.4.2.2 | 1 |

| GH13 CBM48 |

Isoamylase/Glycogen debranching enzyme | treX/glgX | EC 3.2.1.68/ 3.2.1.- | 2 |

| Malto-oligosyltrehalose synthase | treY | EC 5.4.99.15 | 5 | |

| Malto-oligosyltrehalose trehalohydrolase | treZ | EC 3.2.1.141 | 1 |

3.5.2. Stress Response Genes in the Strain So.54

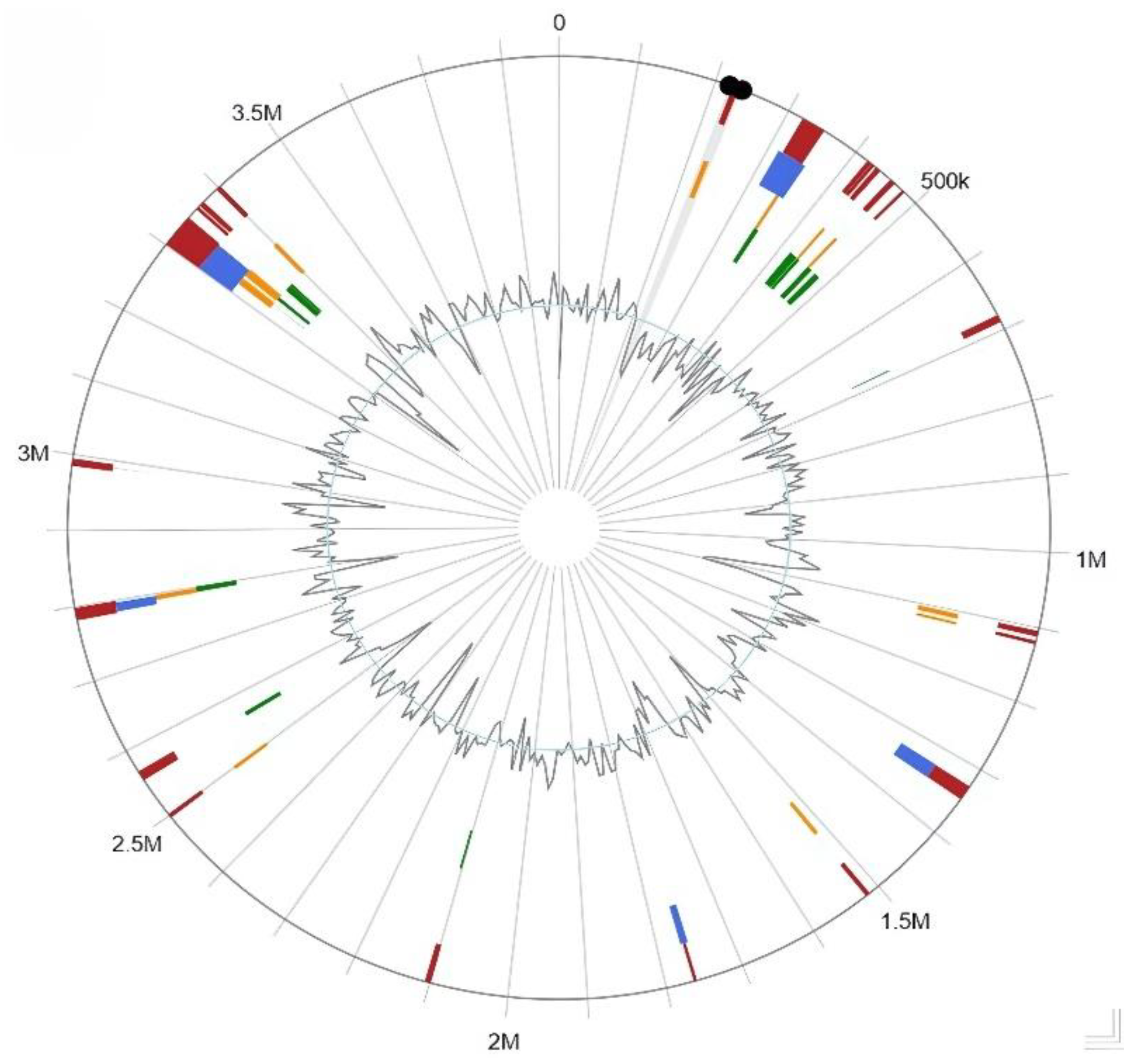

3.6. Genomic Islands Prediction

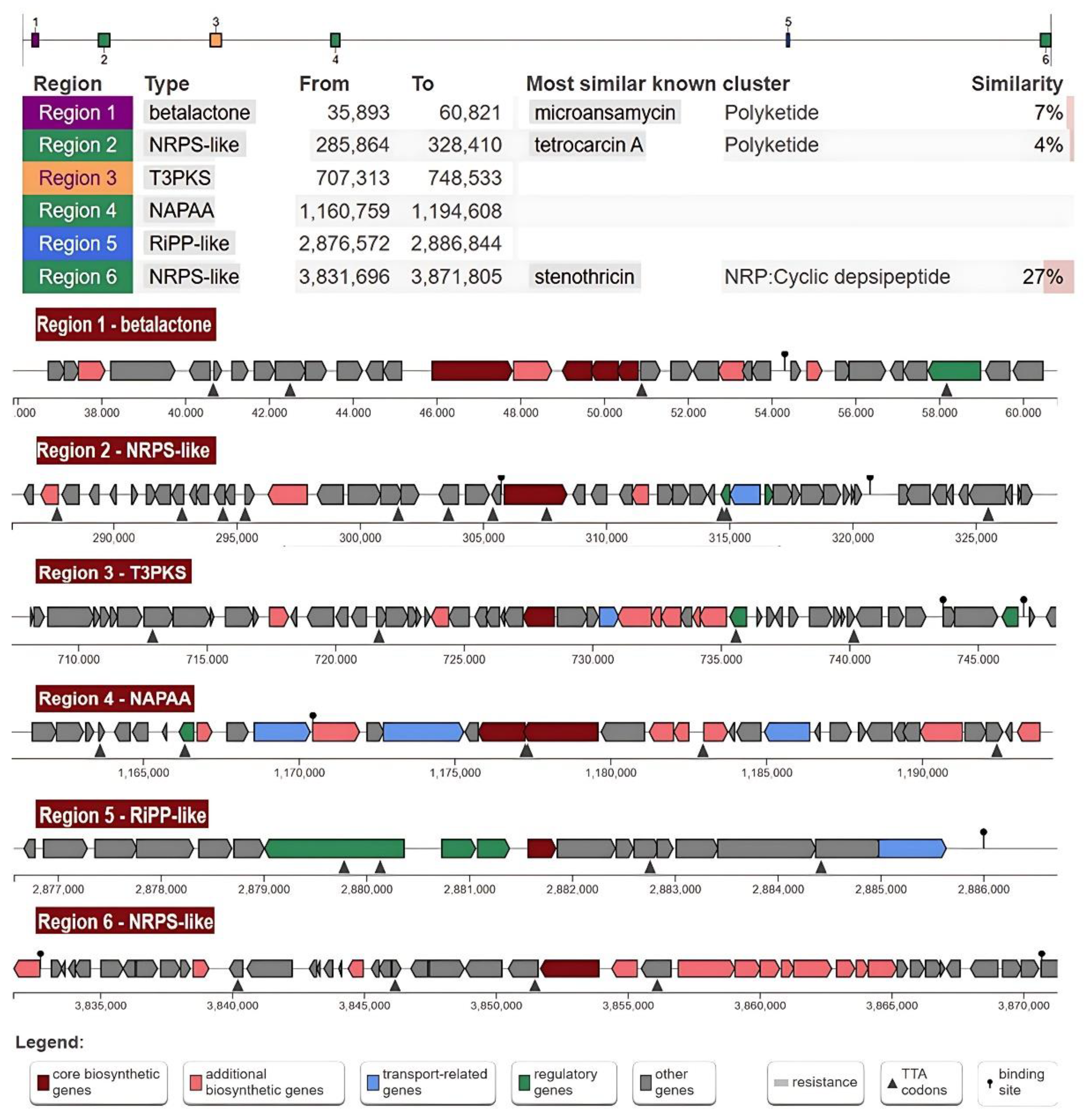

3.7. Secondary Metabolites

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Park, M.K.; Park, Y.J.; Kim, M.; Kim, M.C.; Ibal, J.C.; Kang, G.U.; et al. Complete genome sequence of a plant growth-promoting bacterium Pseudarthrobacter sp. NIBRBAC000502772, isolated from shooting range soil in the Republic of Korea. Korean J. Microbiol. 2020, 56, 390-393. [CrossRef]

- Busse, H.J. Review of the taxonomy of the genus Arthrobacter, emendation of the genus Arthrobacter sensu lato, proposal to reclassify selected species of the genus Arthrobacter in the novel genera Glutamicibacter gen. nov., Paeniglutamicibacter gen. nov., Pseudoglutamicibacter gen. nov., Paenarthrobacter gen. nov. and Pseudarthrobacter gen. nov., and emended description of Arthrobacter roseus. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 9-37. [CrossRef]

- Busse, H.J.; Schumann, P. Reclassification of Arthrobacter enclensis as Pseudarthrobacter enclensis comb. nov., and emended descriptions of the genus Pseudarthrobacter, and the species Pseudarthrobacter phenanthrenivorans and Pseudarthrobacter scleromae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2019, 69, 3508-3511. [CrossRef]

- Sivalingam, P.; Hong, K.; Pote, J.; Prabakar, K. Extreme environment Streptomyces: potential sources for new antibacterial and anticancer drug leads?. Int. J. Microbiol. 2019, 2019, 5283948. [CrossRef]

- Boetius, A.; Anesio, A.M.; Deming, J.W.; Mikucki, J.A.; Rapp, J.Z. Microbial ecology of the cryosphere: sea ice and glacial habitats. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 677-690. [CrossRef]

- King-Miaow, K.; Lee, K.; Maki, T.; LaCapBugler, D.; Archer, S.D.J. Airborne microorganisms in Antarctica: transport, survival and establishment. In The Ecological Role of Micro-organisms in the Antarctic Environment; Castro-Sowinski, S., Ed; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 163-196. [CrossRef]

- Ben Fekih, I.; Ma, Y.; Herzberg, M.; Zhang, C.; Li, Y.P.; Mazhar, S.H.; et al. Draft genome sequence of Pseudarthrobacter sp. strain AG30, isolated from a gold and copper mine in China. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2018, 7, e01329-18. [CrossRef]

- Karmacharya, J.; Shrestha, P.; Han, S.R.; Park, H.; Oh, T.J. Complete genome sequencing of polar Arthrobacter sp. PAMC25284, copper tolerance potential unraveled with genomic analysis. Int. J. Microbiol. 2022, 2022, 1162938. [CrossRef]

- Han, S.R.; Kim, B.; Jang, J.H.; Park, H.; Oh, T.J. Complete genome sequence of Arthrobacter sp. PAMC25564 and its comparative genome analysis for elucidating the role of CAZymes in cold adaptation. BMC Genom. 2021, 22, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Shivani, T.; Aishwarya, H.; Mahesh, C.; Suneel, D. Psychrophiles: A journey of hope. J. Biosci. 2021, 46, 64. [CrossRef]

- Seyedsayamdost, M.R. High-throughput platform for the discovery of elicitors of silent bacterial gene clusters. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2014, 111, 7266-7271. [CrossRef]

- Nair, S.; Abraham, J. Natural products from Actinobacteria for drug discovery. In Advances in Pharmaceutical Biotechnology: Recent Progress and Future Applications; Patra, J., Shukla, A., Das, G., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 333-363. [CrossRef]

- De Coster, W.; D’hert, S.; Schultz, D.T.; Cruts, M.; Van Broeckhoven, C. NanoPack: visualizing and processing long-read sequencing data. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 2666-2669. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Nie, F.; Xie S.Q.; Zheng, Y.F.; Dai, Q.; Bray, T.; et al. Efficient assembly of nanopore reads via highly accurate and intact error correction. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 60. [CrossRef]

- Gurevich, A.; Saveliev, V.; Vyahhi, N.; Tesler, G. QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 1072-1075. [CrossRef]

- Parks, D.H.; Imelfort, M.; Skennerton, C.T.; Hugenholtz, P.; Tyson, G.W. CheckM: assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res. 2015, 25, 1043-1055. [CrossRef]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Göker, M. TYGS is an automated high-throughput platform for state-of-the-art genome-based taxonomy. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2182. [CrossRef]

- Ondov, B.D.; Treangen, T.J.; Melsted, P.; Mallonee, A.B.; Bergman, N.H.; Koren, S.; Phillippy, A.M. Mash: fast genome and metagenome distance estimation using MinHash. Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Lagesen, K.; Hallin, P.; Rødland, E.A.; Stærfeldt, H.H.; Rognes, T.; Ussery, D.W. RNAmmer: consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, 3100-3108. [CrossRef]

- Camacho, C.; Coulouris, G.; Avagyan, V.; Ma, N.; Papadopoulos, J.; Bealer, K.; Madden, T.L. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinform. 2009, 10, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Auch, A.F.; Klenk, H.P.; Göker, M. Genome sequencebased species delimitation with confidence intervals and improved distance functions. BMC Bioinform. 2013, 14, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Lefort, V.; Desper, R.; Gascuel, O. FastME 2.0: a comprehensive, accurate, and fast distance-based phylogeny inference program. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015, 32, 2798-2800. [CrossRef]

- Kreft, Ł.; Botzki, A.; Coppens, F.; Vandepoele, K.; Van Bel, M. PhyD3: a phylogenetic tree viewer with extended phyloXML support for functional genomics data visualization. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 2946-2947. [CrossRef]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Hahnke, R.L.; Petersen, J.; Scheuner, C.; Michael, V.; et al. Complete genome sequence of DSM 30083 T, the type strain (U5/41 T) of Escherichia coli, and a proposal for delineating subspecies in microbial taxonomy. Stand. Genomic Sci. 2014, 9, 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Environmental Microbial Genomics Laboratory. Available online: https://enve-omics.gatech.edu/ (accessed on 06 June 2024).

- Aziz, R.K.; Bartels, D.; Best, A.A.; DeJongh, M.; Disz, T.; Edwards, R.A.; et al. The RAST Server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genom. 2008, 9, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Brettin, T.; Davis, J.J.; Disz, T.; Edwards, R.A.; Gerdes, S.; Olsen, G.J.; et al. RASTtk: a modular and extensible implementation of the RAST algorithm for building custom annotation pipelines and annotating batches of genomes. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 8365. [CrossRef]

- Seemann, T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2068–2069. [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Sato, Y.; Morishima, K. BlastKOALA and GhostKOALA: KEGG tools for functional characterization of genome and metagenome sequences. J. Mol. Biol. 2016, 428, 726-731. [CrossRef]

- Eren, A.M.; Esen, Ö.C.; Quince, C.; Vineis, J.H.; Morrison, H.G.; Sogin, M.L.; Delmont, T.O. Anvi’o: an advanced analysis and visualization platform for ’omics data. PeerJ 2015, 3, e1319. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Ge, Q.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Huang, L.; Yin, Y. dbCAN3: automated carbohydrate-active enzyme and substrate annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, W115-W121. [CrossRef]

- Bertelli, C.; Laird, M.R.; Williams, K.P.; Simon Fraser University Research Computing Group; Lau, B.Y.; Hoad, G.; et al. IslandViewer 4: expanded prediction of genomic islands for larger-scale datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, W30-W35. [CrossRef]

- Blin, K.; Shaw, S.; Kloosterman, A.M.; Charlop-Powers, Z.; Van Wezel, G.P.; Medema, M.H.; Weber, T. antiSMASH 6.0: improving cluster detection and comparison capabilities. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W29-W35. [CrossRef]

- Tshishonga, K.; Serepa-Dlamini, M.H. Draft genome sequence of Pseudarthrobacter phenanthrenivorans Strain MHSD1, a bacterial endophyte isolated from the medicinal plant Pellaea calomelanos. Evol. Bioinform. 2020, 16, 1176934320913257. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ping, W.; Zhu, L.; Xin, Y.; Zhang, J. Pseudarthrobacter albicanus sp. nov., isolated from Antarctic soil. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2022, 72, 005182. [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Lee, B.H.; Lee, K.E.; Park, W. Pseudarthrobacter psychrotolerans sp. nov., a cold-adapted bacterium isolated from Antarctic soilInt. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 6106-6114. [CrossRef]

- Richter, M.; Rosselló-Móra, R. Shifting the genomic gold standard for the prokaryotic species definition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2009, 106, 19126-19131. [CrossRef]

- Qin, Q.L.; Xie, B.B.; Zhang, X.Y.; Chen, X.L.; Zhou, B.C.; Zhou, J.; et al. A proposed genus boundary for the prokaryotes based on genomic insights. J. Bacteriol. 2014, 196, 2210-2215. [CrossRef]

- Jantaro, S.; Kanwal, S. Low-molecular-weight nitrogenous compounds (GABA and polyamines) in blue–green algae. In Algal Green Chemistry; Rastogi, R.P., Madamwar, D., Pandey, A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 149-169. [CrossRef]

- Shiels, K.; Murray, P.; Saha, S.K. Marine cyanobacteria as potential alternative source for GABA production. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2019, 8, 100342. [CrossRef]

- Ciok, A.; Budzik, K.; Zdanowski, M.K.; Gawor, J.; Grzesiak, J.; Decewicz, P.; et al. Plasmids of psychrotolerant Polaromonas spp. isolated from Arctic and Antarctic glaciers–diversity and role in adaptation to polar environments. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1285. [CrossRef]

- Frankenberg, N.; Moser, J.; Jahn, D. Bacterial heme biosynthesis and its biotechnological application. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2003, 63, 115-127. [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, A.H.; Schyns, G.; Potot, S.; Sun, G.; Begley, T. P. A new thiamin salvage pathway. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007, 3, 492-497. [CrossRef]

- Revuelta, J.L.; Serrano-Amatriain, C.; Ledesma-Amaro, R.; Jiménez, A. Formation of folates by microorganisms: towards the biotechnological production of this vitamin. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 8613-8620. [CrossRef]

- Du, Q.; Wang, H.; Xie, J. Thiamin (vitamin B1) biosynthesis and regulation: a rich source of antimicrobial drug targets?. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2011, 7, 41. [CrossRef]

- Spry, C.; Kirk, K.; Saliba, K.J. Coenzyme A biosynthesis: an antimicrobial drug target. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2008, 32, 56-106. [CrossRef]

- Castro-Severyn, J.; Pardo-Esté, C.; Mendez, K.N.; Morales, N.; Marquez, S.L.; Molina, F.; et al. Genomic variation and arsenic tolerance emerged as niche specific adaptations by different Exiguobacterium strains isolated from the extreme Salar de Huasco environment in Chilean–Altiplano. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 554642. [CrossRef]

- Hunter, W.N. The non-mevalonate pathway of isoprenoid precursor biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 21573-21577. [CrossRef]

- Saini, R.K.; Sivanesan, I.; Keum, Y.S. Emerging roles of carotenoids in the survival and adaptations of microbes. Indian J. Microbiol. 2019, 59, 125-127. [CrossRef]

- Dieser, M.; Greenwood, M.; Foreman, C.M. Carotenoid pigmentation in Antarctic heterotrophic bacteria as a strategy to withstand environmental stresses. Arct. Antarct. Alp. Res. 2010, 42, 396-405. [CrossRef]

- Morozova, O.V.; Andreeva, I.S.; Zhirakovskiy, V.Y.; Pechurkina, N.I.; Puchkova, L.I.; Saranina, I.V.; et al. Antibiotic resistance and cold-adaptive enzymes of antarctic culturable bacteria from King George Island. Polar Sci. 2022, 31, 100756. [CrossRef]

- Aliyu, H.; De Maayer, P.; Cowan, D. The genome of the Antarctic polyextremophile Nesterenkonia sp. AN1 reveals adaptive strategies for survival under multiple stress conditions. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2016, 92. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wise, M.J. Glycogen with short average chain length enhances bacterial durability. Naturwissenschaften 2011, 98, 719-729. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Sun, H.; Yang, R.; Li, S.; Zhou, M.; Gao, T.; et al. Complete genome sequence of a psychotrophic Pseudarthrobacter sulfonivorans strain Ar51 (CGMCC 4.7316), a novel crude oil and multi benzene compounds degradation strain. J. Biotechnol. 2016, 231, 81-82. [CrossRef]

- Csonka, L.N. Physiological and genetic responses of bacteria to osmotic stress. Microbiol. Rev. 1989, 53, 121-147. [CrossRef]

- Wood, J.M. Osmosensing by bacteria: signals and membrane-based sensors. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1999, 63, 230-262. [CrossRef]

- Tanghe, A.; Van Dijck, P.; Thevelein, J. M. Why do microorganisms have aquaporins? Trends Microbiol. 2006, 14, 78- 85. [CrossRef]

- Ben-Amotz, A.; Avron, M.The role of glycerol in the osmotic regulation of the halophilic alga Dunaliella parva. Plant Physiol. 1973, 51, 875-878. [CrossRef]

- Otur, Ç.; Okay, S.; Kurt-Kızıldoğan, A. Whole genome analysis of Flavobacterium aziz-sancarii sp. nov., isolated from Ardley Island (Antarctica), revealed a rich resistome and bioremediation potential. Chemosphere 2023, 313, 137511. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Feng, D.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Q.; Luo, Y.; Dong, X. Proteomic insights into the temperature responses of a cold-adaptive archaeon Methanolobus psychrophilus R15. Extremophiles 2015, 19, 249- 259. [CrossRef]

- De Maayer, P.; Anderson, D.; Cary, C.; Cowan, D.A. Some like it cold: understanding the survival strategies of psychrophiles. EMBO Rep. 2014, 15, 508-517. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, G.; Ray, A.K.; Pandey, S.; Kumar, R. An alternative approach of toxic heavy metal removal by Arthrobacter phenanthrenivorans: assessment of surfactant production and oxidative stress. Curr. Sci. 2016, 110, 2124-2128. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24908142.

- Tucker, N.P.; Hicks, M.G.; Clarke, T.A.; Crack, J.C.; Chandra, G.; Le Brun, N.E.; et al. The transcriptional repressor protein NsrR senses nitric oxide directly via a [2Fe-2S] cluster. PloS one 2008, 3, e3623. [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.; Lata, C. Heavy metal stress, signaling, and tolerance due to plant-associated microbes: an overview. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 452. [CrossRef]

- Boehmwald, F.; Muñoz, P.; Flores, P.; Blamey, J.M. Functional screening for the discovery of new extremophilic enzymes. In Biotechnology of Extremophiles: Grand Challenges in Biology and Biotechnology; Rampelotto, P., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 1, pp. 321–350. [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, J.; Mehandia, S.; Singh, G.; Raina, A.; Arya, S.K. Catalase enzyme: Application in bioremediation and food industry. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2018, 16, 192-199. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Kokare, C. Microbial enzymes of use in industry. In Biotechnology of microbial enzymes, 2nd ed.; Brahmachari, G., Ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2023; pp. 405-444. [CrossRef]

- Cavicchioli, R.; Charlton, T.; Ertan, H.; Omar, S.M.; Siddiqui, K.S.; Williams, T. Biotechnological uses of enzymes from psychrophiles. Microb. Biotechnol. 2011, 4, 449-460. [CrossRef]

- Raymond-Bouchard, I.; Goordial, J.; Zolotarov, Y.; Ronholm, J.; Stromvik, M.; Bakermans, C.; Whyte, L.G. Conserved genomic and amino acid traits of cold adaptation in subzero-growing Arctic permafrost bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2018, 94, fiy023. [CrossRef]

- Abrashev, R.; Feller, G.; Kostadinova, N.; Krumova, E.; Alexieva, Z.; Gerginova, M.; et al. Production, purification, and characterization of a novel cold-active superoxide dismutase from the Antarctic strain Aspergillus glaucus 363. Fungal Biol. 2016, 120, 679-689. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Nie, P.; Hou, Y.; Wang, Y. Purification, biochemical characterization and DNA protection against oxidative damage of a novel recombinant superoxide dismutase from psychrophilic bacterium Halomonas sp. ANT108. Protein Expr. Purif. 2020, 173, 105661. [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, K.P.; Mahawar, L.; Rajasabapathy, R.; Rajeshwari, K.; Miceli, C.; Pucciarelli, S. Comprehensive insights on environmental adaptation strategies in Antarctic bacteria and biotechnological applications of cold adapted molecules. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1197797. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hou, Y.; Nie, P.; Wang, Y.; Ren, X.; Wei, Q.; Wang, Q. A novel cold-adapted and salt-tolerant RNase R from Antarctic sea-ice bacterium Psychrobacter sp. ANT206. Molecules 2019, 24, 2229. [CrossRef]

- Ham, S.H.; Yoon, A.R.; Oh, H.E.; Park, Y.G. Plant growth-promoting microorganism Pseudarthrobacter sp. NIBRBAC000502770 enhances the growth and flavonoid content of Geum aleppicum. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1241. [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Shahrajabian, M.H.; Soleymani, A. The Roles of Plant-Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR)-Based Biostimulants for Agricultural Production Systems. Plants 2024, 13, 613. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Wang, Y.; Ma, L.; Huang, S.; Wang, L.; He, J.; Guo, C. Genomic Characteristics and Functional Analysis of Brucella sp. Strain WY7 Isolated from Antarctic Krill. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2281. [CrossRef]

- Ishii, E.; Eguchi, Y. Diversity in sensing and signaling of bacterial sensor histidine kinases. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1524. [CrossRef]

- Newton, G.L.; Buchmeier, N.; Fahey, R.C. Biosynthesis and functions of mycothiol, the unique protective thiol of Actinobacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2008, 72, 471-494. [CrossRef]

- Lienkamp, A.C.; Heine, T.; Tischler, D. Glutathione: a powerful but rare cofactor among Actinobacteria. In Advances in Applied Microbiology; Gadd, G.M., Sariaslani, S., Eds.;, Academic Press: London, UK, 2020; pp. 181-217. [CrossRef]

- Masip, L.; Veeravalli, K.; Georgiou, G. The many faces of glutathione in bacteria. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2006, 8, 753-762. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xia, X.; Zhang, M.; Fang, J.; Li, Y. Purification and characterization of glutathione binding protein GsiB from Escherichia coli. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Tribelli, P.M.; López, N.I. Reporting key features in cold-adapted bacteria. Life 2018, 8, 8. [CrossRef]

- Bushra, R.; Uzair, B.; Ali, A.; Manzoor, S.; Abbas, S.; Ahmed, I. Draft genome sequence of a halotolerant plant growth-promoting bacterium Pseudarthrobacter oxydans NCCP-2145 isolated from rhizospheric soil of mangrove plant Avicennia marina. Electr. J. Biotechnol. 2023, 66, 52-59. [CrossRef]

- Issifu, M.; Songoro, E.K.; Onguso, J.; Ateka, E.M.; Ngumi, V.W. Potential of Pseudarthrobacter chlorophenolicus BF2P4-5 as a Biofertilizer for the Growth Promotion of Tomato Plants. Bacteria 2022, 1, 191-206. [CrossRef]

- Latif, A.; Ahmad, R.; Ahmed, J.; Mueen, H.; Khan, S.A.; Bibi, G. Novel halotolerant PGPR strains alleviate salt stress by enhancing antioxidant activities and expression of selected genes leading to improved growth of Solanum lycopersicum. Scientia Hortic. 2024, 338, 113625. [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.N.; Narzary, D. Heavy metal tolerance of bacterial isolates associated with overburden strata of an opencast coal mine of Assam (India). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 63111-63126. [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Soyol-Erdene, T.O.; Hwang, H.J.; Hong, S.B.; Hur, S.D.; Motoyama, H. Evidence of global-scale As, Mo, Sb, and Tl atmospheric pollution in the Antarctic snow. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 11550-11557. [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Montero, K.; Rojas-Villalta, D.; Barrientos, L. Antarctic Sphingomonas sp. So64. 6b showed evolutive divergence within its genus, including new biosynthetic gene clusters. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1007225. [CrossRef]

- Marzan, L.W.; Hossain, M.; Mina, S.A.; Akter, Y.; Chowdhury, A.M.A. Isolation and biochemical characterization of heavy-metal resistant bacteria from tannery effluent in Chittagong city, Bangladesh: Bioremediation viewpoint. Egypt. J. Aquat. Res. 2017, 43, 65-74. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, B.; Varjani, S.; Kumar, G.; Awasthi, M.K.; Awasthi, S.K.; Sindhu, R.; et al. Microbial approaches for remediation of pollutants: innovations, future outlook, and challenges. Energy Environ. 2021, 32, 1029-1058. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.X.; Chen, Y.Y.; Ge, L.; Fang, T.T.; Meng, J., Liu, Z.; et al. PCR screening reveals considerable unexploited biosynthetic potential of ansamycins and a mysterious family of AHBA- containing natural products in actinomycetes. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2013, 115, 77-85. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.C.; Sun, P.; Xue, J.; Du, Y.; Yan, H.; Wang, L.W.; et al. Arthrobacter wenxiniae sp. nov., a novel plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria species harbouring a carotenoids biosynthetic gene cluster. Antonie Van. Leeuwenhoek 2022, 115, 353-364. [CrossRef]

- Chhetri, G.; Kim, I.; Kang, M.; So, Y.; Kim, J.; Seo, T. An Isolated Arthrobacter sp. Enhances Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Plant Growth Microorg. 2022, 6, 1187. [CrossRef]

- Staunton, J.; Weissman, K.J. Polyketide biosynthesis: a millennium review. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2001, 18, 380- 416. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Decker, R.; Zhan, J. Biochemical characterization of a type III polyketide biosynthetic gene cluster from Streptomyces toxytricini. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2012, 166, 1020-1033. [CrossRef]

- Teufel, R.; Kaysser, L.; Villaume, M.T.; Diethelm, S.; Carbullido, M.K.; Baran, P.S.; Moore, B. S. One-pot enzymatic synthesis of merochlorin A and B. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 11019-11022. [CrossRef]

- Funabashi, M.; Funa, N.; Horinouchi, S. Phenolic lipids synthesized by type III polyketide synthase confer penicillin resistance on Streptomyces griseus. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 13983-13991. [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, Y.; Ogata, H.; Goto, S. Type III polyketide synthases: functional classification and phylogenomics. ChemBioChem 2017, 18, 50-65. [CrossRef]

- Ye, R.; Xu, H.; Wan, C.; Peng, S.; Wang, L.; Xu, H.; et al. Antibacterial activity and mechanism of action of ε-poly-l-lysine. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013, 439, 148-153. [CrossRef]

- Skinnider, M. A.; Johnston, C.W.; Edgar, R.E.; Dejong, C.A.; Merwin, N.J.; Rees, P.N.; Magarvey, N.A. Genomic charting of ribosomally synthesized natural product chemical space facilitates targeted mining. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2016, 113, E6343-E6351. [CrossRef]

- Verma, E.; Chakraborty, S.; Tiwari, B.; Mishra, A.K. Antimicrobial compounds from Actinobacteria: synthetic pathways and applications. In New and Future Developments in Microbial Biotechnology and Bioengineering; Singh, B.P., Gupta, V.K., Passari, A.K., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 277-295. [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, L.; Jia, X.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Liu, W. Cloning and characterization of the tetrocarcin A gene cluster from Micromonospora chalcea NRRL 11289 reveals a highly conserved strategy for tetronate biosynthesis in spirotetronate antibiotics. J. Bacteriol. 2008, 190, 6014-6025. [CrossRef]

- Vieweg, L.; Reichau, S.; Schobert, R.; Leadlay, P.F.; Süssmuth, R.D. Recent advances in the field of bioactive tetronates. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2014, 31, 1554-1584. [CrossRef]

- Tomita, F.; Tamaoki, T.; Shirahata, K.; Kasai, M.; Morimoto, M.; Ohkubo, S.; et al. Novel antitumor antibiotics, tetrocarcins. J. Antibiot. 1980, 33, 668-670. [CrossRef]

- Hasenböhler, A.; Kneifel, H.; König, W.A.; Zähner, H.; Zeiler, H.J. Metabolic products of microorganisms: 134. Stenothricin, a new inhibitor of the bacterial cell wall synthesis. Arch. Microbiol. 1974, 99, 307- 321. [CrossRef]

- Shaligram, S.; Narwade, N.P.; Kumbhare, S.V.; Bordoloi, M.; Tamuli, K.J.; Nath, S.; et al. Integrated Genomic and Functional Characterization of the Anti-diabetic Potential of Arthrobacter sp. SW1. Curr. Microbiol. 2021, 78, 2577-2588. [CrossRef]

| Gene | Start | Stop | Length (bp) | EC number | Protein description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aqpZ | 1215433 | 1214576 | 858 | Aquaporin Z | |

| glpF | 800030 | 799281 | 750 | Glycerol uptake facilitator protein | |

| nsrR | 3009139 | 3008675 | 465 | Nitrite-sensitive transcriptional repressor NsrR | |

| oxyR | 2203595 | 2204515 | 921 | Hydrogen peroxide-inducible genes activator | |

| yaaA | 1016474 | 1017181 | 708 | Peroxide stress protein YaaA | |

| ahpE | 1031338 | 1030820 | 519 | EC:1.11.1.15 | Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase E |

| trxA | 468834 1764701 2494905 3758479 |

469199 1765114 2495231 3758916 |

366 414 327 438 |

Thioredoxin | |

| tpx | 2154742 | 2155221 | 480 | Thioredoxin-dependent thiol peroxidase | |

| trxB | 2493849 3682416 |

2494865 3683393 |

1016 978 |

EC:1.8.1.9 | Thioredoxin-disulfide reductase |

| osmCL | 2895233 | 2895063 | 171 | Organic hydroperoxide resistance transcriptional regulator | |

| osmCLR | 119555 | 119337 | 219 | Organic hydroperoxide resistance protein | |

| sodA | 608696 | 609319 | 624 | EC:1.15.1.1 | Superoxide dismutase [Mn/Fe] |

| katA | 1782412 3440614 |

1783911 3441678 | 1500 1065 |

EC:1.11.1.6 | Catalase |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).