Submitted:

11 March 2025

Posted:

12 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

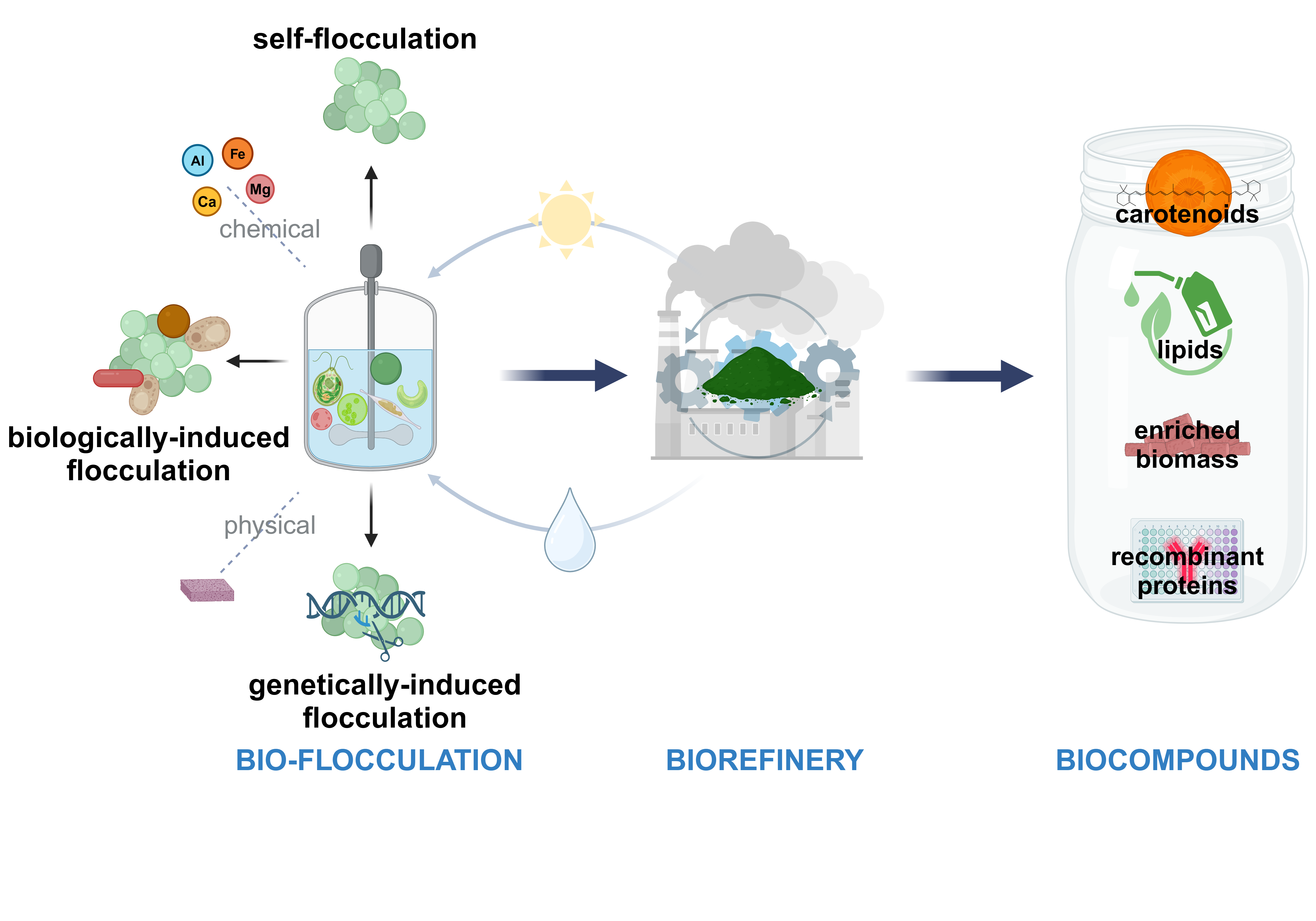

1. Introduction

2. Flocculation Methods

2.1. Physical Flocculation

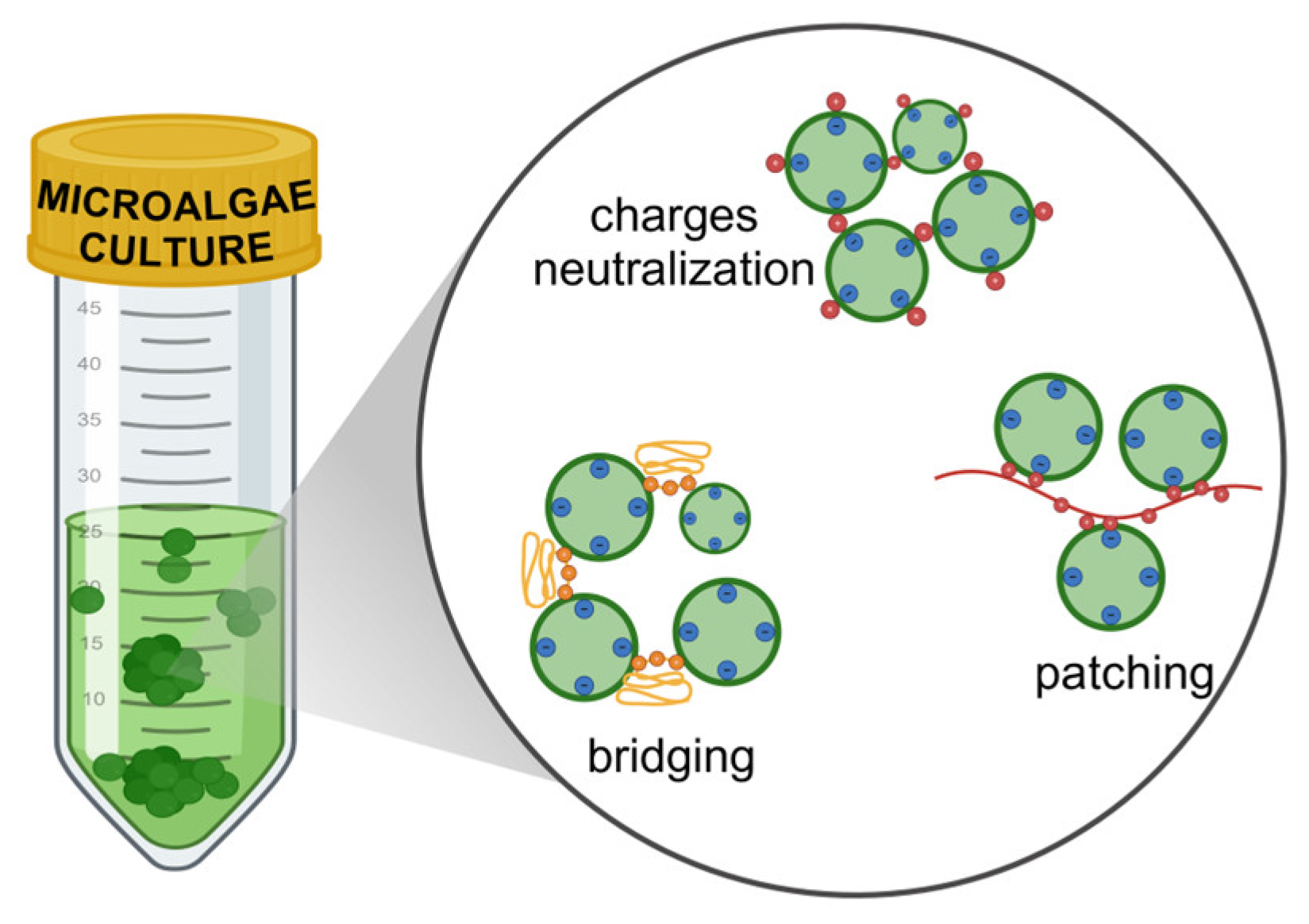

2.2. Chemical Flocculation

2.3. Bio-Flocculation

2.3.1. Flocculation by Bio-Flocculant Molecules

2.3.2. Fungi-Mediated Flocculation

2.3.3. Bacteria-Mediated Flocculation

2.3.4. Alga-Mediated Flocculation

2.3.5. Self-Flocculation

3. Valuable Microalgae Compounds and Bio-Flocculation Implications

3.1. Lipids

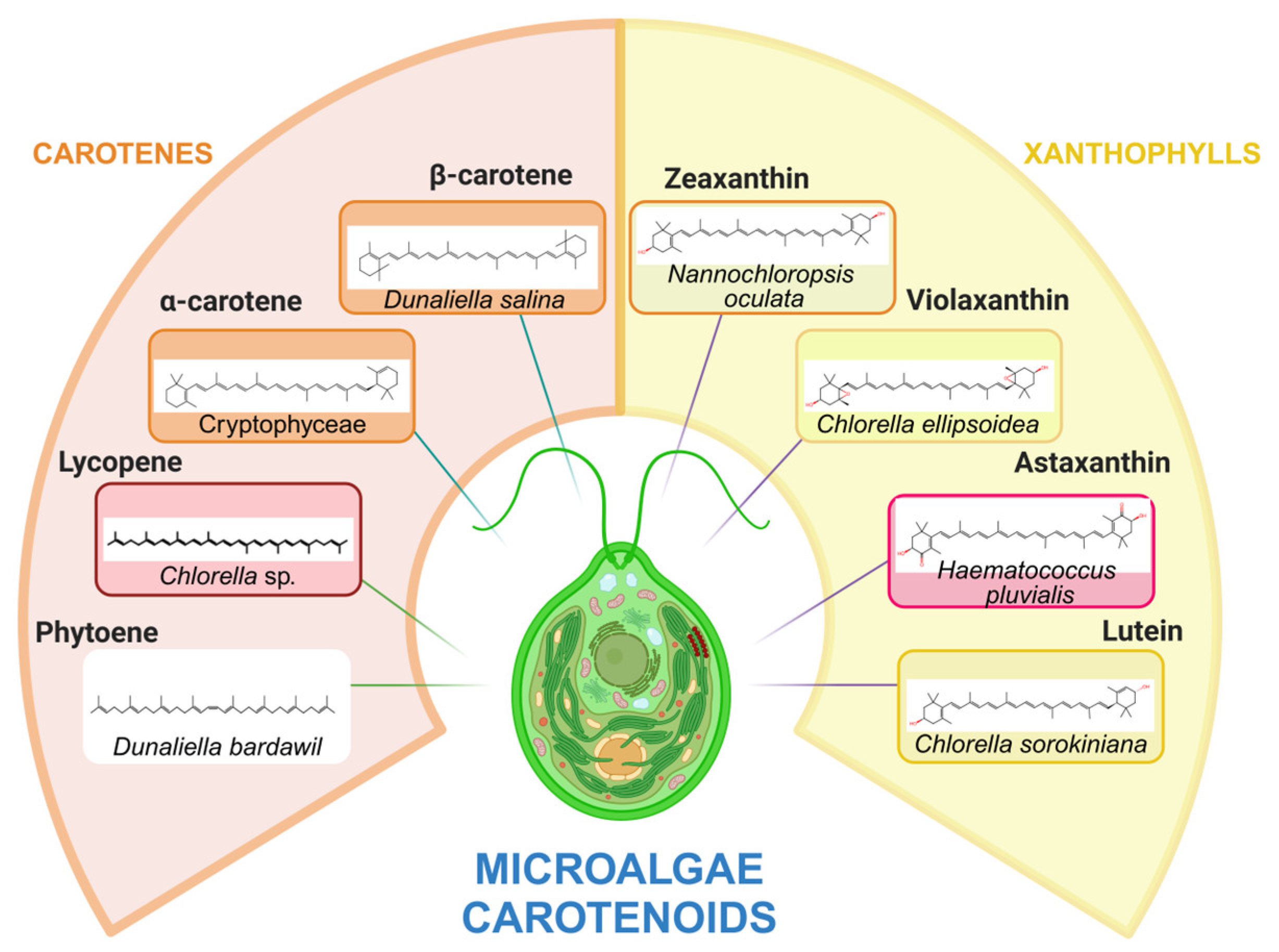

3.2. Carotenoids

3.3. Proteins

3.4. Other Valuable Compounds

Phytohormones and Biostimulant Molecules

Biocidal Molecules

Enriched Biomass and Biofertilization

Polysaccharides

Starch and Other Carbohydrates

4. Conclusion

5. Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, L.; Cheng, W.; Liu, T. Combined Production of Fucoxanthin and EPA from Two Diatom Strains Phaeodactylum Tricornutum and Cylindrotheca Fusiformis Cultures. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng 2018, 41, 1061–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darwesh, O.M.; Matter, I.A.; Eida, M.F.; Moawad, H.; Oh, Y.K. Influence of Nitrogen Source and Growth Phase on Extracellular Biosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Cultural Filtrates of Scenedesmus Obliquus. Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspeta, L.; Buijs, N.A.A.; Nielsen, J. The Role of Biofuels in the Future Energy Supply. Energy Environ Sci 2013, 6, 1077–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abas, N.; Kalair, A.; Khan, N. Review of Fossil Fuels and Future Energy Technologies. Futures 2015, 69, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, A.; Banerjee, S.; Das, D. Microalgal Bio-Flocculation: Present Scenario and Prospects for Commercialization. [CrossRef]

- Malik, S.; Khan, F.; Atta, Z.; Habib, N.; Haider, M.N.; Wang, N.; Alam, A.; Jambi, E.J.; Gull, M.; Mehmood, M.A.; et al. Microalgal Flocculation: Global Research Progress and Prospects for Algal Biorefinery. Biotechnol Appl Biochem 2020, 67, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathimani, T.; Senthil Kumar, T.; Chandrasekar, M.; Uma, L.; Prabaharan, D. Assessment of Fuel Properties, Engine Performance and Emission Characteristics of Outdoor Grown Marine Chlorella Vulgaris BDUG 91771 Biodiesel. Renew Energy 2017, 105, 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Hu, J.; Zhu, L. Self-flocculation as an Efficient Method to Harvest Microalgae: A Mini-review. Water (Switzerland) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milledge, J.J.; Heaven, S. A Review of the Harvesting of Micro-Algae for Biofuel Production. Rev Environ Sci Biotechnol 2013, 12, 165–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Nugroho, Y.K.; Shakeel, S.R.; Li, Z.; Martinkauppi, B.; Hiltunen, E. Using Microalgae to Produce Liquid Transportation Biodiesel: What Is Next? Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2017, 78, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, B.H.H.; Ong, H.C.; Cheah, M.Y.; Chen, W.H.; Yu, K.L.; Mahlia, T.M.I. Sustainability of Direct Biodiesel Synthesis from Microalgae Biomass: A Critical Review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2019, 107, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, S.R.; Ong, H.C.; Chew, K.W.; Show, P.L.; Phang, S.M.; Ling, T.C.; Nagarajan, D.; Lee, D.J.; Chang, J.S. Sustainable Approaches for Algae Utilisation in Bioenergy Production. Renew Energy 2018, 129, 838–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, L.; Morón-Villarreyes, J.A.; D’Oca, M.G.M.; Abreu, P.C. Effects of Flocculants on Lipid Extraction and Fatty Acid Composition of the Microalgae Nannochloropsis Oculata and Thalassiosira Weissflogii. Biomass Bioenergy 2011, 35, 4449–4454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.J.L.B.; Laurens, L.M.L. Microalgae as Biodiesel & Biomass Feedstocks: Review & Analysis of the Biochemistry, Energetics & Economics. Energy Environ Sci 2010, 3, 554–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Mishra, S.K.; Shrivastav, A.; Park, M.S.; Yang, J.W. Recent Trends in the Mass Cultivation of Algae in Raceway Ponds. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2015, 51, 875–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eze, C.N.; Onyejiaka, C.K.; Ihim, S.A.; Ayoka, T.O.; Aduba, C.C.; Ndukwe, J.K.; Nwaiwu, O.; Onyeaka, H. Bioactive Compounds by Microalgae and Potentials for the Management of Some Human Disease Conditions. AIMS Microbiol 2023, 9, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Branyikova, I.; Filipenska, M.; Urbanova, K.; Ruzicka, M.C.; Pivokonsky, M.; Branyik, T. Physicochemical Approach to Alkaline Flocculation of Chlorella Vulgaris Induced by Calcium Phosphate Precipitates. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2018, 166, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.C.; Lee, K.; Oh, Y.K. Recent Nanoparticle Engineering Advances in Microalgal Cultivation and Harvesting Processes of Biodiesel Production: A Review. Bioresour Technol 2015, 184, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Hu, T.; Xu, Y.; Wang, J.; Chu, R.; Yin, Z.; Mo, F.; Zhu, L. A Review on Flocculation as an Efficient Method to Harvest Energy Microalgae: Mechanisms, Performances, Influencing Factors and Perspectives. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2020, 131, 110005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandamme, D.; Pontes, S.C.V.; Goiris, K.; Foubert, I.; Pinoy, L.J.J.; Muylaert, K. Evaluation of Electro-Coagulation-Flocculation for Harvesting Marine and Freshwater Microalgae. Biotechnol Bioeng 2011, 108, 2320–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Baz, F.K.; Gad, M.S.; Abdo, S.M.; Abed, K.A.; Matter, I.A. Performance and Exhaust Emissions of a Diesel Engine Burning Algal Biodiesel Blends. International Journal of Mechanical and Mechatronics Engineering 2016, 16, 151–158. [Google Scholar]

- Van Haver, L.; Nayar, S. Polyelectrolyte Flocculants in Harvesting Microalgal Biomass for Food and Feed Applications. Algal Res 2017, 24, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanyano, N.; Chetpattananondh, P.; Chongkhong, S. Coagulation-Flocculation of Marine Chlorella Sp. for Biodiesel Production. Bioresour Technol 2013, 147, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Patidar, S.K. Microalgae Harvesting Techniques: A Review. J Environ Manage 2018, 217, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathimani, T.; Mallick, N. A Comprehensive Review on Harvesting of Microalgae for Biodiesel - Key Challenges and Future Directions. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2018, 91, 1103–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Alam, M.A.; Zhao, X.Q.; Zhang, X.Y.; Guo, S.L.; Ho, S.H.; Chang, J.S.; Bai, F.W. Current Progress and Future Prospect of Microalgal Biomass Harvest Using Various Flocculation Technologies. Bioresour Technol 2015, 184, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, J.; Sung, M.; Ryu, H.; Oh, Y.K.; Han, J.I. Microalgae Dewatering Based on Forward Osmosis Employing Proton Exchange Membrane. Bioresour Technol 2017, 244, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laamanen, C.A.; Ross, G.M.; Scott, J.A. Flotation Harvesting of Microalgae. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2016, 58, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, I.; Besson, A.; Guiraud, P.; Formosa-Dague, C. Towards a Better Understanding of Microalgae Natural Flocculation Mechanisms to Enhance Flotation Harvesting Efficiency. Water Science and Technology 2020, 82, 1009–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukenik, A.; Bilanovic, D.; Shelef, G. Flocculation of Microalgae in Brackish and Sea Waters. Biomass 1988, 15, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battah, M.; El-Ayoty, Y.; El-Fatah Abomohra, A.; El-Ghany, S.A.; Esmael, A.; Chaudhary, R.; Khattar, J.; Singh, D.; Luísa da Cunha Gonçalves, A.; José Vieira Simões José Carlos Magalhães Pires, M.; et al. Flocculation as a Low-Cost Method for Harvesting Microalgae for Bulk Biomass Production KU Leuven Kulak, Laboratory Aquatic Biology, E. Sabbelaan 53, 8500 Kortrijk, Corresponding Author: Trends Biotechnol 2013, 31, 233–239. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, Y.K.; Ho, Y.H.; Leung, H.M.; Ho, K.C.; Yau, Y.H.; Yung, K.K.L. Enhancement of Chlorella Vulgaris Harvesting via the Electro-Coagulation-Flotation (ECF) Method. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2017, 24, 9102–9110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estrada-Graf, A.; Hernández, S.; Morales, M. Biomitigation of CO2 from Flue Gas by Scenedesmus Obtusiusculus AT-UAM Using a Hybrid Photobioreactor Coupled to a Biomass Recovery Stage by Electro-Coagulation-Flotation. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2020, 27, 28561–28574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.Y.; Lee, K.; Lee, J.; Lee, Y.H.; Han, J.I.; Park, J.Y.; Oh, Y.K. Acidified-Flocculation Process for Harvesting of Microalgae: Coagulant Reutilization and Metal-Free-Microalgae Recovery. Bioresour Technol 2017, 239, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Tang, Z.; Yang, D.; Dai, X.; Chen, H. Enhanced Growth and Auto-Flocculation of Scenedesmus Quadricauda in Anaerobic Digestate Using High Light Intensity and Nanosilica: A Biomineralization-Inspired Strategy. Water Res 2023, 235, 119893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerff, M.; Morweiser, M.; Dillschneider, R.; Michel, A.; Menzel, K.; Posten, C. Harvesting Fresh Water and Marine Algae by Magnetic Separation: Screening of Separation Parameters and High Gradient Magnetic Filtration. Bioresour Technol 2012, 118, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Lee, S.Y.; Na, J.G.; Jeon, S.G.; Praveenkumar, R.; Kim, D.M.; Chang, W.S.; Oh, Y.K. Magnetophoretic Harvesting of Oleaginous Chlorella Sp. by Using Biocompatible Chitosan/Magnetic Nanoparticle Composites. Bioresour Technol 2013, 149, 575–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, J.K.; Chieh, D.C.J.; Jalak, S.A.; Toh, P.Y.; Yasin, N.H.M.; Ng, B.W.; Ahmad, A.L. Rapid Magnetophoretic Separation of Microalgae. Small 2012, 8, 1683–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumathi, Y.; Kumar, P.; Singhania, R.R.; Chen, C.W.; Gurunathan, B.; Dong, C. Di; Patel, A.K. Harnessing Fe3O4 Nanoparticles for Sustainable Harvesting of Astaxanthin-Producing Microalgae: Advancing Industrial-Scale Biorefinery. Sep Purif Technol 2025, 353, 128408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, G.; Pandey, V.K.; Ahmad, S.; Irum; Khujamshukurov, N. A.; Farooqui, A.; Mishra, V. Utilizing Novel Aspergillus Species for Bio-Flocculation: A Cost-Effective Approach to Harvest Scenedesmus Microalgae for Biofuel Production. Curr Res Microb Sci 2024, 7, 100272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Liu, C.; Wang, A.; Yue, B.; Lin, T.; Ding, M. Microalgae Treatment of Food Processing Wastewater for Simultaneous Biomass Resource Recycling and Water Reuse. J Environ Manage 2024, 369, 122394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekli, L.; Corjon, E.; Tabatabai, S.A.A.; Naidu, G.; Tamburic, B.; Park, S.H.; Shon, H.K. Performance of Titanium Salts Compared to Conventional FeCl3 for the Removal of Algal Organic Matter (AOM) in Synthetic Seawater: Coagulation Performance, Organic Fraction Removal and Floc Characteristics. J Environ Manage 2017, 201, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maia, C.; Pôjo, V.; Tavares, T.; Pires, J.C.M.; Malcata, F.X. Surfactant-Mediated Microalgal Flocculation: Process Efficiency and Kinetic Modelling. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yudong, N.; Tao, Z.; Haihua, W.; Haixing, C. Upcycling Harmful Algal Blooms into Short-Chain Organic Matters Assisted with Cellulose-Based Flocculant. Bioresour Technol 2024, 397, 130425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papazi, A.; Makridis, P.; Divanach, P. Harvesting Chlorella Minutissima Using Cell Coagulants. J Appl Phycol 2010, 22, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rwehumbiza, V.M.; Harrison, R.; Thomsen, L. Alum-Induced Flocculation of Preconcentrated Nannochloropsis Salina: Residual Aluminium in the Biomass, FAMEs and Its Effects on Microalgae Growth upon Media Recycling. Chemical Engineering Journal 2012, 200–202, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beach, E.S.; Eckelman, M.J.; Cui, Z.; Brentner, L.; Zimmerman, J.B. Preferential Technological and Life Cycle Environmental Performance of Chitosan Flocculation for Harvesting of the Green Algae Neochloris Oleoabundans. Bioresour Technol 2012, 121, 445–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Gao, Z.; Yin, J.; Tang, X.; Ji, X.; Huang, H. Harvesting of Microalgae by Flocculation with Poly (γ-Glutamic Acid). Bioresour Technol 2012, 112, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, Y.P.; Guo, J.S.; Fang, F.; Yan, P. Flocculation-Enhanced Photobiological Hydrogen Production by Microalgae: Flocculant Composition, Hydrogenase Activity and Response Mechanism. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 485, 150065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.T.; Le, B.H.; Lee, D.J.; Chen, C.L.; Wang, H.Y.; Chang, J.S. Microalgae Harvesting and Subsequent Biodiesel Conversion. Bioresour Technol 2013, 140, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swar, S.S.; Boonnorat, J.; Ghimire, A. Algae-Based Treatment of a Landfill Leachate Pretreated by Coagulation-Flocculation. J Environ Manage 2023, 342, 118223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinho, Y.F.; de Oliveira, A.P.S.; Oliveira, C.Y.B.; Napoleão, T.H.; Guedes Paiva, P.M.; de Sant’Anna, M.C.S.; Malafaia, C.B.; Gálvez, A.O. Usage of Moringa Oleifera Residual Seeds Promotes Efficient Flocculation of Tetradesmus Dimorphus Biomass. Biomass Convers Biorefin 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lama, S.; Pappa, M.; Brandão Watanabe, N.; Formosa–Dague, C.; Marchal, W.; Adriaensens, P.; Vandamme, D. Interference of Extracellular Soluble Algal Organic Matter on Flocculation–Sedimentation Harvesting of Chlorella Sp. Bioresour Technol 2024, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Liu, Z.; Li, D.; Liu, C.; Zheng, P.; Chen, S. Using Ammonia for Algae Harvesting and as Nutrient in Subsequent Cultures. Bioresour Technol 2012, 121, 298–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imbimbo, P.; Ferrara, A.; Giustino, E.; Liberti, D.; Monti, D.M. Microalgae Flocculation: Assessment of Extraction Yields and Biological Activity. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endrawati, H.; Widianingsih, W.; Nuraini, R.A.T.; Hartati, R.; Redjeki, S.; Riniatsih, I.; Mahendrajaya, R.T. The Effect of Chitosan Concentration on Flocculation Efficiency Microalgae Porphyridium Cruentum (Rhodhophyta). IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci 2021, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gani, P.; Apandi, N.M.; Mohamed Sunar, N.; Matias-Peralta, H.M.; Kean Hua, A.; Mohd Dzulkifli, S.N.; Parjo, U.K. Outdoor Phycoremediation and Biomass Harvesting Optimization of Microalgae Botryococcus Sp. Cultivated in Food Processing Wastewater Using an Enclosed Photobioreactor. Int J Phytoremediation 2022, 24, 1431–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.D.P.; Tran, T.N.T.; Le, T.V.A.; Nguyen Phan, T.X.; Show, P.L.; Chia, S.R. Auto-Flocculation through Cultivation of Chlorella Vulgaris in Seafood Wastewater Discharge: Influence of Culture Conditions on Microalgae Growth and Nutrient Removal. J Biosci Bioeng 2019, 127, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, L.; Salgueiro, J.L.; Maceiras, R.; Cancela, Á.; Sánchez, Á. An Effective Method for Harvesting of Marine Microalgae: PH Induced Flocculation. Biomass Bioenergy 2017, 97, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlesinger, A.; Eisenstadt, D.; Bar-Gil, A.; Carmely, H.; Einbinder, S.; Gressel, J. Inexpensive Non-Toxic Flocculation of Microalgae Contradicts Theories; Overcoming a Major Hurdle to Bulk Algal Production. Biotechnol Adv 2012, 30, 1023–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verfaillie, A.; Blockx, J.; Praveenkumar, R.; Thielemans, W.; Muylaert, K. Harvesting of Marine Microalgae Using Cationic Cellulose Nanocrystals. Carbohydr Polym 2020, 240, 116165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mixson, S.M.; Stikeleather, L.F.; Simmons, O.D.; Wilson, C.W.; Burkholder, J.A.M. PH-Induced Flocculation, Indirect Electrocoagulation, and Hollow Fiber Filtration Techniques for Harvesting the Saltwater Microalga Dunaliella. J Appl Phycol 2014, 26, 1701–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spilling, K.; Seppälä, J.; Tamminen, T. Inducing Autoflocculation in the Diatom Phaeodactylum Tricornutum through CO2 Regulation. J Appl Phycol 2011, 23, 959–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ’t Lam, G.P.; Vermuë, M.H.; Olivieri, G.; van den Broek, L.A.M.; Barbosa, M.J.; Eppink, M.H.M.; Wijffels, R.H.; Kleinegris, D.M.M. Cationic Polymers for Successful Flocculation of Marine Microalgae. Bioresour Technol 2014, 169, 804–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Huang, W.; Zhang, C.; Li, T.; Zhang, Y.; Li, A. Evaluation of Flocculation Induced by PH Increase for Harvesting Microalgae and Reuse of Flocculated Medium. Bioresour Technol 2012, 110, 496–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, L.; Xu, X.; Yan, F.; Du, W.; Dai, R. Simultaneous Removal of Cyanobacteria and Algal Organic Matter by Mn(VII)/CaSO3 Enhanced Coagulation: Performance and Mechanism. J Hazard Mater 2025, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.R.; Wang, F.; Wang, S.K.; Liu, C.Z.; Guo, C. Efficient Harvesting of Marine Microalgae Nannochloropsis Maritima Using Magnetic Nanoparticles. Bioresour Technol 2013, 138, 387–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Hende, S.; Carré, E.; Cocaud, E.; Beelen, V.; Boon, N.; Vervaeren, H. Treatment of Industrial Wastewaters by Microalgal Bacterial Flocs in Sequencing Batch Reactors. Bioresour Technol 2014, 161, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.G.; La, H.J.; Ahn, C.Y.; Park, Y.H.; Oh, H.M. Harvest of Scenedesmus Sp. with Bioflocculant and Reuse of Culture Medium for Subsequent High-Density Cultures. Bioresour Technol 2011, 102, 3163–3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Wang, T.; Dou, Z.; Xie, X. Microalgae Harvesting by Self-Driven 3D Microfiltration with Rationally Designed Porous Superabsorbent Polymer (PSAP) Beads. Environ Sci Technol 2021, 55, 15446–15455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Humairi, S.T.; Lee, J.G.M.; Harvey, A.P.; Salman, A.D.; Juzsakova, T.; Van, B.; Le, P.C.; La, D.D.; Mungray, A.K.; Show, P.L.; et al. A Foam Column System Harvesting Freshwater Algae for Biodiesel Production: An Experiment and Process Model Evaluations. Science of the Total Environment 2023, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ma, Q.; Pan, Y.; Chen, Q.; Sun, Z.; Hu, P. Development of an Effective Flocculation Method by Utilizing the Auto-Flocculation Capability of Phaeodactylum Tricornutum. Algal Res 2021, 58, 102413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorin, K. V.; Sergeeva, Y.E.; Butylin, V. V.; Komova, A. V.; Pojidaev, V.M.; Badranova, G.U.; Shapovalova, A.A.; Konova, I.A.; Gotovtsev, P.M. Methods Coagulation/Flocculation and Flocculation with Ballast Agent for Effective Harvesting of Microalgae. Bioresour Technol 2015, 193, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, H.-M.; Lee, S.J.; Park, M.-H.; Kim, H.-S.; Kim, H.-C.; Yoon, J.-H.; Kwon, G.-S.; Yoon, B.-D. Harvesting of Chlorella Vulgaris Using a Bioflocculant from Paenibacillus Sp. AM49; 2001; Vol. 23;

- Ayad, H.I.; Matter, I.A.; Gharieb, M.M.; Darwesh, O.M. Bioflocculation Harvesting of Oleaginous Microalga Chlorella Sp. Using Novel Lipid-Rich Cellulolytic Fungus Aspergillus Terreus (MD1) for Biodiesel Production. Biomass Convers Biorefin. [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, G.; Pandey, V.K.; Ahmad, S. ; Irum; Khujamshukurov, N.A.; Farooqui, A.; Mishra, V. Utilizing Novel Aspergillus Species for Bio-Flocculation: A Cost-Effective Approach to Harvest Scenedesmus Microalgae for Biofuel Production. Curr Res Microb Sci.

- Cho, K.; Hur, S.P.; Lee, C.H.; Ko, K.; Lee, Y.J.; Kim, K.N.; Kim, M.S.; Chung, Y.H.; Kim, D.; Oda, T. Bioflocculation of the Oceanic Microalga Dunaliella Salina by the Bloom-Forming Dinoflagellate Heterocapsa Circularisquama, and Its Effect on Biodiesel Properties of the Biomass. Bioresour Technol 2016, 202, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roselet, F.; Burkert, J.; Abreu, P.C. Flocculation of Nannochloropsis Oculata Using a Tannin-Based Polymer: Bench Scale Optimization and Pilot Scale Reproducibility. Biomass Bioenergy 2016, 87, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farid, M.S.; Shariati, A.; Badakhshan, A.; Anvaripour, B. Using Nano-Chitosan for Harvesting Microalga Nannochloropsis Sp. Bioresour Technol 2013, 131, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hothaly, K.A. An Optimized Method for the Bio-Harvesting of Microalgae, Botryococcus Braunii, Using Aspergillus Sp. in Large-Scale Studies. MethodsX 2018, 5, 788–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; He, G. Influence of Nutritional Conditions on Exopolysaccharide Production by Submerged Cultivation of the Medicinal Fungus Shiraia Bambusicola. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 2008, 24, 2903–2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, S.; Banerjee, D. Fungal Exopolysaccharide: Production, Composition and Applications. Microbiol Insights 2013, 6, MBI.S10957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civzele, A.; Mezule, L. Fungal – Assisted Microalgae Flocculation and Simultaneous Lignocellulolytic Enzyme Production in Wastewater Treatment Systems. Biotechnology Reports 2025, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, R.J.; Hill, R.T. Mechanism of Algal Aggregation by Bacillus Sp. Strain RP1137. Appl Environ Microbiol 2014, 80, 4042–4050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Zhao, X.Q.; Guo, S.L.; Asraful Alam, M.; Bai, F.W. Bioflocculant Production from Solibacillus Silvestris W01 and Its Application in Cost-Effective Harvest of Marine Microalga Nannochloropsis Oceanica by Flocculation. Bioresour Technol 2013, 135, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakshmikandan, M.; Murugesan, A.G.; Ameen, F.; Maneeruttanarungroj, C.; Wang, S. Efficient Bioflocculation and Biodiesel Production of Microalgae Asterococcus Limneticus on Streptomyces Two-Stage Co-Cultivation Strategy. Biomass Bioenergy 2023, 175, 106886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndikubwimana, T.; Zeng, X.; Liu, Y.; Chang, J.S.; Lu, Y. Harvesting of Microalgae Desmodesmus Sp. F51 by Bioflocculation with Bacterial Bioflocculant. Algal Res 2014, 6, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.; Hur, S.P.; Lee, C.H.; Ko, K.; Lee, Y.J.; Kim, K.N.; Kim, M.S.; Chung, Y.H.; Kim, D.; Oda, T. Bioflocculation of the Oceanic Microalga Dunaliella Salina by the Bloom-Forming Dinoflagellate Heterocapsa Circularisquama, and Its Effect on Biodiesel Properties of the Biomass. Bioresour Technol 2016, 202, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.M.; Lee, S.J.; Park, M.H.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, H.C.; Yoon, J.H.; Kwon, G.S.; Yoon, B.D. Harvesting of Chlorella Vulgaris Using a Bioflocculant from Paenibacillus Sp. AM49. Biotechnol Lett 2001, 23, 1229–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Chen, Y.; Shao, Z.; Chen, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, W.; Zheng, T. Effective Harvesting of the Microalgae Chlorella Vulgaris via Flocculation-Flotation with Bioflocculant. Bioresour Technol 2015, 198, 922–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, Y.; Liu, L.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, K.; Zheng, T.; Wang, H. First Evidence of Bioflocculant from Shinella Albus with Flocculation Activity on Harvesting of Chlorella Vulgaris Biomass. Bioresour Technol 2016, 218, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelaar, J.C.T.; De Keizer, A.; Spijker, S.; Lettinga, G. Bioflocculation of Mesophilic and Thermophilic Activated Sludge. Water Res 2005, 39, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Woo, S.G.; Ten, L.N. Shinella Daejeonensis Sp. Nov., a Nitrate-Reducing Bacterium Isolated from Sludge of a Leachate Treatment Plant. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2011, 61, 2123–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, T.; Shinzato, N.; Tamaki, H.; Muramatsu, M.; Hanada, S. Shinella Yambaruensis Sp. Nov., a 3-Methy-Sulfolane-Assimilating Bacterium Isolated from Soil. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2009, 59, 536–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, A.; Das, D. Biomass Production and Identification of Suitable Harvesting Technique for Chlorella Sp. MJ 11/11 and Synechocystis PCC 6803. 3 Biotech 2016, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.; Zheng, Y. Overview of Microalgal Extracellular Polymeric Substances (EPS) and Their Applications. Biotechnol Adv 2016, 34, 1225–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemming, H.C.; Wingender, J. The Biofilm Matrix. Nat Rev Microbiol 2010, 8, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulsen, B.S.; Aslaksen, T.; Freire-Nordi, C.S.; Vieira, A.A.H. Extracellular Polysaccharides from Ankistrodesmus Densus (Chlorophyceae). J Phycol 1998, 34, 638–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadaoui, I.; Cherif, M.; Siddiqui, S.A.; Al Jabri, H.; Sayadi, S. Algal-Algal Bioflocculation Enhances the Recovery Efficiency of Picochlorum Sp. QUCCCM130 with Low Auto-Settling Capacity. Algal Res 2023, 71, 103038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, S.; Bosma, R.; Vermuë, M.H.; Wijffels, R.H. Harvesting of Microalgae by Bio-Flocculation. J Appl Phycol 2011, 23, 849–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, S.; Vermuë, M.H.; Wijffels, R.H. Ratio between Autoflocculating and Target Microalgae Affects the Energy-Efficient Harvesting by Bio-Flocculation. Bioresour Technol 2012, 118, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.A.; Wan, C.; Guo, S.L.; Zhao, X.Q.; Huang, Z.Y.; Yang, Y.L.; Chang, J.S.; Bai, F.W. Characterization of the Flocculating Agent from the Spontaneously Flocculating Microalga Chlorella Vulgaris JSC-7. J Biosci Bioeng 2014, 118, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, S.; Kosterink, N.R.; Tchetkoua Wacka, N.D.; Vermuë, M.H.; Wijffels, R.H. Mechanism behind Autoflocculation of Unicellular Green Microalgae Ettlia Texensis. J Biotechnol 2014, 174, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Xiao, J.; Ding, W.; Cui, N.; Yu, X.; Xu, J.W.; Li, T.; Zhao, P. An Effective Method for Harvesting of Microalga: Coculture-Induced Self-Flocculation. J Taiwan Inst Chem Eng 2019, 100, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.L.; Zhao, X.Q.; Tang, Y.; Wan, C.; Alam, M.A.; Ho, S.H.; Bai, F.W.; Chang, J.S. Establishment of an Efficient Genetic Transformation System in Scenedesmus Obliquus. J Biotechnol 2013, 163, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ma, Q.; Pan, Y.; Chen, Q.; Sun, Z.; Hu, P. Development of an Effective Flocculation Method by Utilizing the Auto-Flocculation Capability of Phaeodactylum Tricornutum. Algal Res 2021, 58, 102413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muir, E.; Grossman, A.R.; Chisti, Y.; Fedrizzi, B.; Guieysse, B.; Plouviez, M. Self-Aggregation for Sustainable Harvesting of Microalgae. Algal Res 2024, 83, 103685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.Q.; Bai, F.W. Yeast Flocculation: New Story in Fuel Ethanol Production. Biotechnol Adv 2009, 27, 849–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, F.F.; Govender, P.; Bester, M.C. Yeast Flocculation and Its Biotechnological Relevance. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2010, 88, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, A.; Vandamme, D.; Chun, W.; Zhao, X.; Foubert, I.; Wang, Z.; Muylaert, K.; Yuan, Z. Bioflocculation as an Innovative Harvesting Strategy for Microalgae. Rev Environ Sci Biotechnol 2016, 15, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Huang, W.; Zhang, C.; Li, T.; Zhang, Y.; Li, A. Evaluation of Flocculation Induced by PH Increase for Harvesting Microalgae and Reuse of Flocculated Medium. Bioresour Technol 2012, 110, 496–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aljuboori, A.H.R.; Uemura, Y.; Thanh, N.T. Flocculation and Mechanism of Self-Flocculating Lipid Producer Microalga Scenedesmus Quadricauda for Biomass Harvesting. Biomass Bioenergy 2016, 93, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.; Zhang, H.; Sun, S.; Dong, F.; Sun, H.; Li, B. Rapid Flocculation-Sedimentation of Microalgae with Organosilane-Functionalized Halloysite. Appl Clay Sci 2019, 177, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, A.; Sirotiya, V.; Mourya, M.; Khan, M.J.; Ahirwar, A.; Sharma, A.K.; Kawatra, R.; Marchand, J.; Schoefs, B.; Varjani, S.; et al. Sustainable Treatment of Dye Wastewater by Recycling Microalgal and Diatom Biogenic Materials: Biorefinery Perspectives. Chemosphere 2022, 305, 135371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Shao, S.; He, Y.; Luo, Q.; Zheng, M.; Zheng, M.; Chen, B.; Wang, M. Nutrients Removal from Piggery Wastewater Coupled to Lipid Production by a Newly Isolated Self-Flocculating Microalga Desmodesmus Sp. PW1. Bioresour Technol 2020, 302, 122806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.; Chen, D.; Liu, W.; Cobb, K.; Zhou, N.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, Q.; Chen, P.; Zhou, C.; et al. Auto-Flocculation Microalgae Species Tribonema Sp. and Synechocystis Sp. with T-IPL Pretreatment to Improve Swine Wastewater Nutrient Removal. Science of the Total Environment 2020, 725, 138263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilian, O.; Benemann, C.S.E.; Niyogi, K.K.; Vick, B. High-Efficiency Homologous Recombination in the Oil-Producing Alga Nannochloropsis Sp. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011, 108, 21265–21269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trentacoste, E.M.; Shrestha, R.P.; Smith, S.R.; Glé, C.; Hartmann, A.C.; Hildebrand, M.; Gerwick, W.H. Metabolic Engineering of Lipid Catabolism Increases Microalgal Lipid Accumulation without Compromising Growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013, 110, 19748–19753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valverde, F.; Romero-Campero, F.J.; León, R.; Guerrero, M.G.; Serrano, A. New Challenges in Microalgae Biotechnology. Eur J Protistol 2016, 55, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Hao, N.; Hou, Y.; Wang, Q.; Liu, Q.; Yan, S.; Chen, F.; Zhao, L. Technologies for Harvesting the Microalgae for Industrial Applications: Current Trends and Perspectives. Bioresour Technol 2023, 387. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, S.L.; Zhao, X.Q.; Wan, C.; Huang, Z.Y.; Yang, Y.L.; Asraful Alam, M.; Ho, S.H.; Bai, F.W.; Chang, J.S. Characterization of Flocculating Agent from the Self-Flocculating Microalga Scenedesmus Obliquus AS-6-1 for Efficient Biomass Harvest. Bioresour Technol 2013, 145, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Santos, E.; Vila, M.; Vigara, J.; León, R. A New Approach to Express Transgenes in Microalgae and Its Use to Increase the Flocculation Ability of Chlamydomonas Reinhardtii. J Appl Phycol 2016, 28, 1611–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S. ; Pooja; Yadav, S.K. CRISPR-Cas for Genome Editing: Classification, Mechanism, Designing and Applications. Int J Biol Macromol 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pickar-Oliver, A.; Gersbach, C.A. The next Generation of CRISPR–Cas Technologies and Applications. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2019, 20, 490–507. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, A.K.; Singhania, R.R.; Awasthi, M.K.; Varjani, S.; Bhatia, S.K.; Tsai, M.L.; Hsieh, S.L.; Chen, C.W.; Dong, C. Di Emerging Prospects of Macro- and Microalgae as Prebiotic. Microb Cell Fact 2021, 20, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.M.; Lin, J.Y.; Tsai, T.H.; Yang, R.Y.; Ng, I.S. Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) Technology and Genetic Engineering Strategies for Microalgae towards Carbon Neutrality: A Critical Review. Bioresour Technol 2023, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhokane, D.; Shaikh, A.; Yadav, A.; Giri, N.; Bandyopadhyay, A.; Dasgupta, S.; Bhadra, B. CRISPR-Based Bioengineering in Microalgae for Production of Industrially Important Biomolecules. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aditi; Bhardwaj, R. ; Yadav, A.; Swapnil, P.; Meena, M. Characterization of Microalgal β-Carotene and Astaxanthin: Exploring Their Health-Promoting Properties under the Effect of Salinity and Light Intensity. Biotechnology for Biofuels and Bioproducts 2025, 18, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, S.; Qadir, M.L.; Hussain, N.; Ali, Q.; Han, S.; Ali, D. Advances in CRISPR/Cas9 Technology: Shaping the Future of Photosynthetic Microorganisms for Biofuel Production. Functional Plant Biology 2025, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.H.T.; Park, S.; Jeong, J.; Shin, Y.S.; Sim, S.J.; Jin, E.S. Enhancing Lipid Productivity by Modulating Lipid Catabolism Using the CRISPR-Cas9 System in Chlamydomonas. J Appl Phycol 2020, 32, 2829–2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajjawi, I.; Verruto, J.; Aqui, M.; Soriaga, L.B.; Coppersmith, J.; Kwok, K.; Peach, L.; Orchard, E.; Kalb, R.; Xu, W.; et al. Lipid Production in Nannochloropsis Gaditana Is Doubled by Decreasing Expression of a Single Transcriptional Regulator. Nat Biotechnol 2017, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.R.; Ng, I.S. Development of CRISPR/Cas9 System in Chlorella Vulgaris FSP-E to Enhance Lipid Accumulation. Enzyme Microb Technol 2020, 133, 109458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kneip, J.S.; Kniepkamp, N.; Jang, J.; Mortaro, M.G.; Jin, E.; Kruse, O.; Baier, T. CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Knockout of the Lycopene ε-Cyclase for Efficient Astaxanthin Production in the Green Microalga Chlamydomonas Reinhardtii. Plants 2024, 13, 1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Feng, S.; Liang, G.; Du, J.; Li, A.; Niu, C. CRISPR/Cas9-Induced β-Carotene Hydroxylase Mutation in Dunaliella Salina CCAP19/18. AMB Express 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Græsholt, C.; Brembu, T.; Volpe, C.; Bartosova, Z.; Serif, M.; Winge, P.; Nymark, M. Zeaxanthin Epoxidase 3 Knockout Mutants of the Model Diatom Phaeodactylum Tricornutum Enable Commercial Production of the Bioactive Carotenoid Diatoxanthin. Mar Drugs 2024, 22, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambily, B.; Limna Mol, V.P.; Sini, H.; Nevin, K.G. CRISPR-Based Microalgal Genome Editing and the Potential for Sustainable Aquaculture: A Comprehensive Review. J Appl Phycol 2024.

- Fernandes, T.; Cordeiro, N. Microalgae as Sustainable Biofactories to Produce High-Value Lipids: Biodiversity, Exploitation, and Biotechnological Applications. Mar Drugs 2021, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, S.R. Microalgal Lipids: Biochemistry and Biotechnology. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2022, 74, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Y.; Wu, S.; Miao, C.; Xu, T.; Lu, Y. Towards Lipid from Microalgae: Products, Biosynthesis, and Genetic Engineering. Life 2024, 14, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, H.; Wang, Y.; Zuo, M.; Wang, X.; Shen, B. Structural Analysis of Isolated Components in Microalgal Lipids: Neutral Lipids, Phospholipids, and Glycolipids. Bioresour Technol Rep 2025, 29, 102083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J.; Costa, E.; Maia Dias, J.; Pires, J.C. Biodiesel Production by Biocatalysis Using Lipids Extracted from Microalgae Oil of Chlorella Vulgaris and Aurantiochytrium Sp. Bioenergy Res 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyani, D.A.; Maryam, S.; Amina, S.J.; Ahmad, A.; Chattha, M.W.A.; Janjua, H.A. Lipid Extraction and Analysis of Microalgae Strain Pectinodesmus PHM3 for Biodiesel Production. BMC Biotechnol 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Singh, R.P.; Yadav, P.; Kumar, I.; Kaushik, A.; Roychowdhury, R.; Mubeen, M.; Singh, S.K.; Kumar, A.; Wang, J. Recent Advances in Biotechnology and Bioengineering for Efficient Microalgal Biofuel Production. Fuel Processing Technology 2025, 270, 108199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutanda, T.; Naidoo, D.; Bwapwa, J.K.; Anandraj, A. Biotechnological Applications of Microalgal Oleaginous Compounds: Current Trends on Microalgal Bioprocessing of Products. Front Energy Res 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Ye, X.; Bi, H.; Shen, Z. Microalgae Biofuels: Illuminating the Path to a Sustainable Future amidst Challenges and Opportunities. Biotechnology for Biofuels and Bioproducts 2024, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Tsui, T.-H.; Tong, Y.W.; Liu, R.; Baganz, F. Harvesting of Oleaginous Microbial Cells and Extraction of Microbial Lipids. In Microbial Lipids. In Microbial Lipids and Biodiesel Technologies; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2025; pp. 223–239. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Tsui, T.-H.; Tong, Y.W.; Liu, R.; Aggarangsi, P. Microbial Lipid Technology Based on Oleaginous Microalgae. In Microbial Lipids and Biodiesel Technologies; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2025; pp. 77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Muradov, N.; Taha, M.; Miranda, A.F.; Wrede, D.; Kadali, K.; Gujar, A.; Stevenson, T.; Ball, A.S.; Mouradov, A. Fungal-Assisted Algal Flocculation: Application in Wastewater Treatment and Biofuel Production. Biotechnol Biofuels 2015, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, K.K.; Kumar, V.; Gururani, P.; Vlaskin, M.S.; Parveen, A.; Nanda, M.; Kurbatova, A.; Gautam, P.; Grigorenko, A. V. Bio-Flocculation of Oleaginous Microalgae Integrated with Municipal Wastewater Treatment and Its Hydrothermal Liquefaction for Biofuel Production. Environ Technol Innov 2022, 26, 102340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmikandan, M.; Murugesan, A.G.; Ameen, F.; Maneeruttanarungroj, C.; Wang, S. Efficient Bioflocculation and Biodiesel Production of Microalgae Asterococcus Limneticus on Streptomyces Two-Stage Co-Cultivation Strategy. Biomass Bioenergy 2023, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Li, Z.; Hiltunen, E. Theoretical Assessment of Biomethane Production from Algal Residues after Biodiesel Production. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Energy Environ 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbonna, C.N.; Nwoba, E.G. Bio-Based Flocculants for Sustainable Harvesting of Microalgae for Biofuel Production. A Review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021, 139, 110690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, B.; Yang, J. Bio-Flocculation Property Analyses of Oleaginous Microalgae Auxenochlorella Protothecoides Utex 2341. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2021, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjandraatmadja, G.; Diaper, C. Sources of Critical Contaminants in Domestic Wastewater - a Literature Review. 2006, 88.

- Rengel, R.; Giraldez, I.; Díaz, M.J.; García, T.; Vigara, J.; León, R. Simultaneous Production of Carotenoids and Chemical Building Blocks Precursors from Chlorophyta Microalgae. Bioresour Technol 2022, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Lan, J.C.-W.; Kondo, A.; Hasunuma, T. Metabolic Engineering and Cultivation Strategies for Efficient Production of Fucoxanthin and Related Carotenoids. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2025, 109, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, W.; Chen, L.; Tan, Z.; Deng, Z.; Liu, H. Application of Filamentous Fungi in Microalgae-Based Wastewater Remediation for Biomass Harvesting and Utilization: From Mechanisms to Practical Application. Algal Res 2022, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, R.K.; Mehariya, S.; Karthikeyan, O.P.; Verma, P. Fungi-Assisted Bio-Flocculation of Picochlorum Sp.: A Novel Bio-Assisted Treatment System for Municipal Wastewater. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2024, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Úbeda, B.; Gálvez, J.Á.; Michel, M.; Bartual, A. Microalgae Cultivation in Urban Wastewater: Coelastrum Cf. Pseudomicroporum as a Novel Carotenoid Source and a Potential Microalgae Harvesting Tool. Bioresour Technol 2017, 228, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Indahsari, H.S.; Tassakka, A.C.M.A.R.; Dewi, E.N.; Yuwono, M.; Suyono, E.A. Effects of Salinity and Bioflocculation during Euglena Sp. Harvest on the Production of Lipid, Chlorophyll, and Carotenoid with Skeletonema Sp. as a Bioflocculant. J Pure Appl Microbiol 2022, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshobary, M.E.; Ebaid, R.; Alquraishi, M.; Ende, S.S.W. Synergistic Microalgal Cocultivation: Boosting Flocculation, Biomass Production, and Fatty Acids Profile of Nannochloropsis Oculata and Phaeodactylum Tricornutum. Biomass Bioenergy 2025, 193, 107595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, S.; Ashraf, M.U.F.; Shahid, A.; Javed, M.R.; Khan, A.Z.; Usman, M.; Manivannan, A.; Mehmood, M.A.; Ashraf, G.A. Characterization of a Newly Isolated Self-Flocculating Microalga Bracteacoccus Pseudominor BERC09 and Its Evaluation as a Candidate for a Multiproduct Algal Biorefinery. Chemosphere 2022, 304, 135346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galán-González, J.; Quintero-Zapata, I.; Elías-Santos, M.; Galán-Wong, L.J.; López-Chuken, U.J.; Guajardo-Barbosa, C.; Beltrán-Rocha, J.C. Harvest by Autoflocculation, Biomass, and Carotenoid Production in Sequential Batch Culture of Haematococcus Pluvialis Under High Ionic Strength and Macroelements Content. J Mar Sci Technol 2024, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, E.; Odenthal, K.; Nunes, N.; Fernandes, T.; Fernandes, I.A.; Pinheiro de Carvalho, M.A.A. Protein Extracts from Microalgae and Cyanobacteria Biomass. Techno-Functional Properties and Bioactivity: A Review. Algal Res 2024, 82, 103638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, R.; Raja, T.; Kumar, S.; Gokhale, T. Biorefinery Approach to Obtain Sustainable Biofuels and High-Value Chemicals from Microalgae. Microalgal Biofuels 2025, 109–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, A.; Guo, Y.; Yang, T.; Ud Din, A.S.; Ahmad, K.; Li, W.; Hou, H. Microalgae-Derived Peptides: Exploring Bioactivities and Functional Food Innovations. J Agric Food Chem 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Hu, Z.; Liu, S.; Luo, S.; He, R.; Yang, X.; Li, S.; Yang, X.; An, Y.; Lu, Y. Utilization of Microalgae and Duckweed as Sustainable Protein Sources for Food and Feed: Nutritional Potential and Functional Applications. J Agric Food Chem 2025.

- Elisha, C.; Bhagwat, P.; Pillai, S. Emerging Production Techniques and Potential Health Promoting Properties of Plant and Animal Protein-Derived Bioactive Peptides. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2024.

- Quezada-Rivera, J.J.; Ponce-Alonso, J.; Davalos-Guzman, S.D.; Soria-Guerra, R.E. Chlamydomonas Reinhardtii for the Production of Recombinant Proteins: Current Knowledge and Perspectives. Fundamentals of Recombinant Protein Production, Purification and Characterization. [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.; Deng, L.; Wu, H.; Fan, J. Towards Green Biomanufacturing of High-Value Recombinant Proteins Using Promising Cell Factory: Chlamydomonas Reinhardtii Chloroplast. Bioresour Bioprocess 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera-Serrano, B.V.; Cabanillas-Salcido, S.L.; Cordero-Rivera, C.D.; Jiménez-Camacho, R.; Norzagaray-Valenzuela, C.D.; Calderón-Zamora, L.; De Jesús-González, L.A.; Reyes-Ruiz, J.M.; Farfan-Morales, C.N.; Romero-Utrilla, A.; et al. Antiviral Effect of Microalgae Phaeodactylum Tricornutum Protein Hydrolysates against Dengue Virus Serotype 2. Mar Drugs 2024, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, S.; Alonso-Pintre, L.; Morato-López, E.; González de la Fuente, S.; Gómez-Cortés, P.; Hernández-Ledesma, B. Microalga Nannochloropsis Gaditana as a Sustainable Source of Bioactive Peptides: A Proteomic and In Silico Approach. Foods 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stirk, W.A.; Ordog, V.; Novák, O.; Rolčík, J.; Strnad, M.; Balint, P.; van Staden, J. Auxin and Cytokinin Relationships in Twenty-Four Microalgae Strains. J Phycol 2013, 49, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stirk, W.A.; Bálint, P.; Tarkowská, D.; Novák, O.; Strnad, M.; Ördög, V.; van Staden, J. Hormone Profiles in Microalgae: Gibberellins and Brassinosteroids. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2013, 70, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Xu, J. Phytohormones in Microalgae: A New Opportunity for Microalgal Biotechnology? Trends Plant Sci 2015, 20, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puente-Padilla, B.L.; Romero-Villegas, G.I.; Sánchez-Estrada, A.; Cira-Chávez, L.A.; Estrada-Alvarado, M.I. Effect of Marine Microalgae Biomass (Nannochloropsis Gaditana and Thalassiosira Sp. ) on Germination and Vigor on Bean (Phaseolus Vulgaris L.) Seeds “Higuera.” Life 2025, 15, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cock, I.E.; Cheesman, M.J. A Review of the Antimicrobial Properties of Cyanobacterial Natural Products. Molecules 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhardwaj, R.; Yadav, A.; Sahoo, A.; Kumari, P.; Singh, L.A.; Swapnil, P.; Meena, M.; Kumar, S. Microalgal-Based Sustainable Bio-Fungicides: A Promising Solution to Enhance Crop Yield. Discover Sustainability 2025, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, P.; Kumar, R.; Neha, Y.; Srivatsan, V. Microalgae as next Generation Plant Growth Additives: Functions, Applications, Challenges and Circular Bioeconomy Based Solutions. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nur, M.M.A.; Mahreni; Murni, S. W.; Setyoningrum, T.M.; Hadi, F.; Widayati, T.W.; Jaya, D.; Sulistyawati, R.R.E.; Puspitaningrum, D.A.; Dewi, R.N.; et al. Innovative Strategies for Utilizing Microalgae as Dual-Purpose Biofertilizers and Phycoremediators in Agroecosystems. Biotechnology Reports 2025, 45, e00870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guehaz, K.; Boual, Z.; Abdou, I.; Telli, A.; Belkhalfa, H. Microalgae’s Polysaccharides, Are They Potent Antioxidants? Critical Review. Arch Microbiol 2024, 206. [Google Scholar]

- Babich, O.; Ivanova, S.; Michaud, P.; Budenkova, E.; Kashirskikh, E.; Anokhova, V.; Sukhikh, S. Synthesis of Polysaccharides by Microalgae Chlorella Sp. Bioresour Technol 2024, 406, 131043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pointcheval, M.; Massé, A.; Floc’hlay, D.; Chanonat, F.; Estival, J.; Durand, M.J. Antimicrobial Properties of Selected Microalgae Exopolysaccharide-Enriched Extracts: Influence of Antimicrobial Assays and Targeted Microorganisms. Front Microbiol 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Six, A.; Dimitriades-Lemaire, A.; Lancelon-Pin, C.; Putaux, J.L.; Dauvillée, D.; Petroutsos, D.; Alvarez Diaz, P.; Sassi, J.F.; Li-Beisson, Y.; Fleury, G. Red Light Induces Starch Accumulation in Chlorella Vulgaris without Affecting Photosynthesis Efficiency, Unlike Abiotic Stress. Algal Res 2024, 80, 103515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, P.; Bandyopadhyay, T.K.; Gopikrishna, K.; Nath Tiwari, O.; Bhunia, B.; Muthuraj, M. Algal Carbohydrates: Sources, Biosynthetic Pathway, Production, and Applications. Bioresour Technol 2024, 413, 131489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Microalgae | Bio-flocculant used | Recovery efficiency (%) | Reference |

| Chlorella vulgaris | Paenibacillus sp. AM49 | 90 | [74] |

| Chlorella sp. | Aspergillus terreus | 80-90 | [75] |

| Scenedesmus sp. | Aspergillus sp. | 80-90 | [76] |

| Dunaliella salina | Heterocapsa circularisquama | 80-90 | [77] |

| Nannochloropsis oculata | Tannin-based polymer | 99 | [78] |

| Nannochloropsis sp. | Nano-chitosan | 85 | [79] |

| Botryococcus braunii | Aspergillus sp. | 97 | [80] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).