Introduction

Brief Overview of Leishmaniasis as a Neglected Tropical Disease

Leishmaniasis is a vector-borne parasitic disease caused by protozoa of the Leishmania genus and transmitted through the bite of infected female Phlebotomus and Lutzomyia sandflies. It is classified as a Neglected Tropical Disease (NTD) by the World Health Organization (WHO) due to its significant health burden, lack of widespread awareness, and limited research funding (WHO, 2023). The disease is endemic in over 98 countries, with an estimated 1 million new cases annually and a high mortality rate, particularly in regions with inadequate healthcare infrastructure (Burza et al., 2018).

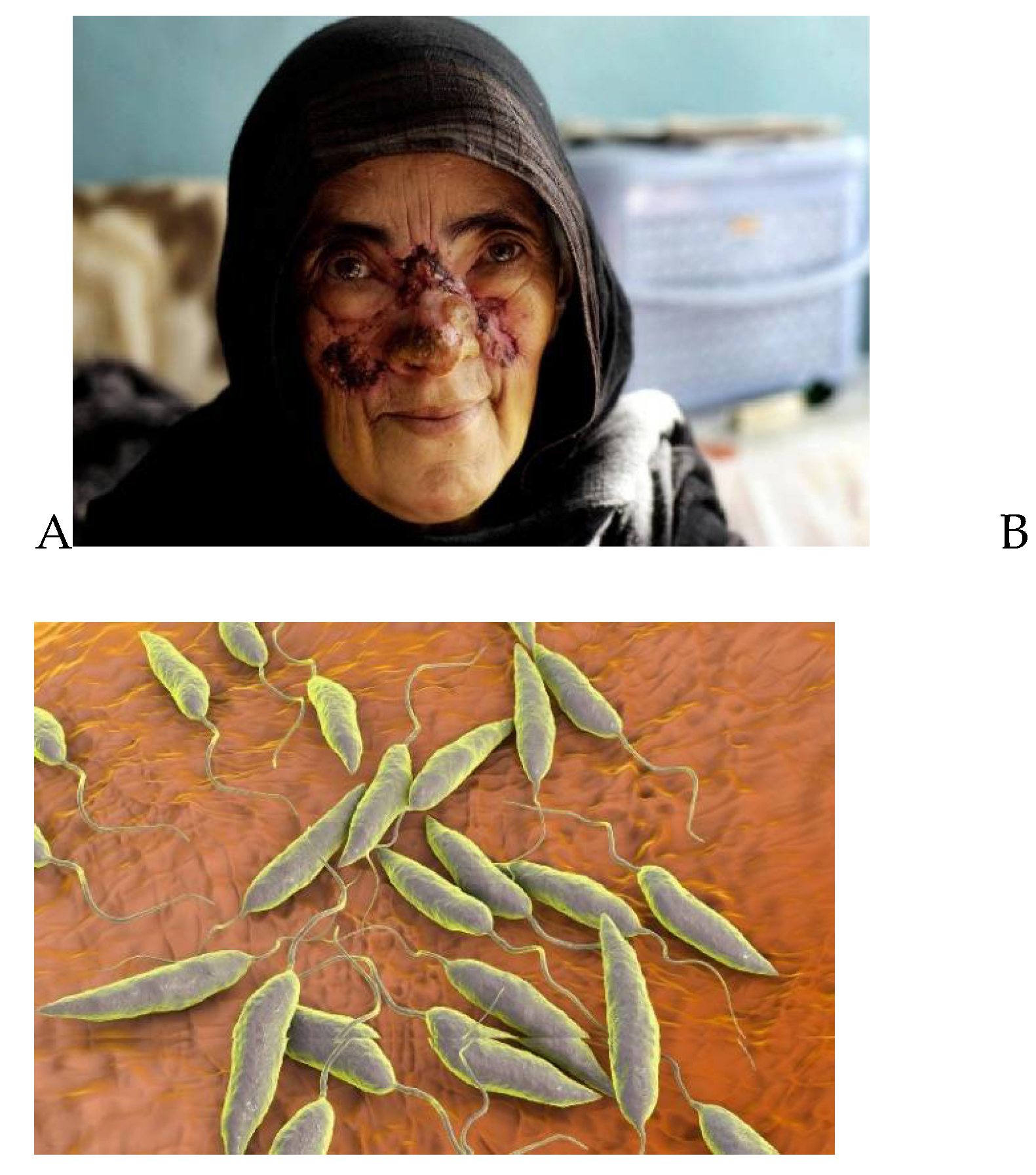

Figure 1.

represents A woman suffering from leishmaniasis, a disease transmitted by sand flies, at the Maywand Hospital in Kabul, Afghanistan, Wednesday December 14, 2005, and B represents Leishmania sp. protozoa, computer illustration. This parasite causes the tropical disease leishmaniasis. This can take several forms, causing open sores on the skin or potentially fatal liver damage.

Figure 1.

represents A woman suffering from leishmaniasis, a disease transmitted by sand flies, at the Maywand Hospital in Kabul, Afghanistan, Wednesday December 14, 2005, and B represents Leishmania sp. protozoa, computer illustration. This parasite causes the tropical disease leishmaniasis. This can take several forms, causing open sores on the skin or potentially fatal liver damage.

Leishmaniasis presents in three primary clinical forms:

Visceral leishmaniasis (VL) (Kala-Azar) – The most severe form, affecting internal organs such as the spleen, liver, and bone marrow, leading to fever, weight loss, anemia, and potentially fatal outcomes if untreated (Hotez et al., 2020).

Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) – The most common form, causing ulcerative skin lesions that may result in permanent scarring and social stigma (Alvar et al., 2012).

Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis (MCL) – A rare but severe manifestation, where parasites spread to mucosal tissues, leading to facial and nasal deformities (Oryan & Akbari, 2016).

Why is Leishmaniasis Neglected?

▪ Affects marginalized populations with limited healthcare access.

▪ Underfunded research and drug development due to low commercial interest.

▪ Drug resistance and lack of affordable treatment options.

▪ Poor disease surveillance in endemic regions.

Public Health Concern and Control Efforts The Indian government, in collaboration with WHO, has implemented several Kala-Azar elimination programs focusing on vector control, early diagnosis, and effective treatment strategies. However, challenges such as drug resistance, lack of vaccines, and socio-economic barriers continue to hinder eradication efforts. India remains a hotspot for visceral leishmaniasis, particularly in Bihar, Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh, and West Bengal, accounting for a significant proportion of global VL cases (Mondal & Alvar, 2020). Despite ongoing elimination programs and advancements in vector control and treatment strategies, the disease persists due to drug resistance, poor healthcare access, and socio-economic challenges (Sundar & Singh, 2018). The urgent need for affordable vaccines and novel therapies highlights the importance of continued research and investment in combating this neglected disease.

Epidemiology and Global Burden, with a Focus on INDIA

In the case of global Burden of Leishmaniasis an estimated 1 million new cases of leishmaniasis occur annually, with over 20,000 to 30,000 deaths each year (WHO, 2023). The disease primarily affects South Asia, East Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East. The three main clinical forms visceral leishmaniasis (VL), cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL), and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis (MCL) vary in severity and geographical distribution. Visceral leishmaniasis (VL), also known as Kala-Azar, is the most lethal form, responsible for over 90% of deaths caused by leishmaniasis worldwide (Alvar et al., 2012). Major endemic countries include India, Brazil, Ethiopia, Sudan, South Sudan, and Bangladesh, which together account for over 70% of VL cases globally (Mondal & Alvar, 2020). Key Statistics shows that India accounted for nearly 50% of global VL cases in the early 2000s, but cases have significantly declined due to the National Kala-Azar Elimination Program (Mondal & Alvar, 2020). The disease burden is highest among economically disadvantaged communities, where poor housing conditions and malnutrition increase susceptibility. Post-Kala-Azar Dermal Leishmaniasis (PKDL) is a growing concern, as it contributes to continued disease transmission even after VL treatment (Sundar & Singh, 2018). Drug resistance and limited access to treatment remain challenges, requiring continued surveillance and research (Burza et al., 2018).

Efforts Toward Kala-Azar Elimination in India

India has made significant progress toward eliminating VL, defined as less than one case per 10,000 population at the district level. Major efforts include:

Vector control measures, such as indoor residual spraying (IRS) and insecticide-treated nets.

Early case detection and treatment through government-led programs.

Introduction of liposomal amphotericin B (LAmB) as the primary treatment option, reducing mortality rates.

Cross-border collaborations with Nepal and Bangladesh to curb disease transmission.

Despite these efforts, challenges such as emerging drug resistance, lack of vaccines, and persistent socio-economic barriers continue to hinder complete elimination (Hirve et al., 2017). Sustained research, public health interventions, and global collaborations remain critical to eradicating leishmaniasis in India and worldwide.

Importance of Understanding Pathology and Treatment Strategies

Importance of Understanding Pathology

The pathology of leishmaniasis varies depending on the species of Leishmania parasite, the host immune response, and the form of the disease (visceral, cutaneous, or mucocutaneous). Key reasons for studying the disease pathology include:

A. Host-Parasite Interaction and Immune Response

Leishmania parasites invade and replicate inside macrophages, evading the host immune response (Olivier et al., 2005). The disease progression depends on T-cell immune responses, with Th1 responses promoting parasite clearance and Th2 responses facilitating disease progression (Sacks & Noben-Trauth, 2002). Understanding immune evasion mechanisms helps in developing vaccines and immune-based therapies.

B. Disease Manifestations and Diagnosis

In visceral leishmaniasis, the parasite spreads to the spleen, liver, and bone marrow, causing hepatosplenomegaly, fever, anemia, and weight loss. Post-Kala-Azar Dermal Leishmaniasis (PKDL), common in India, is crucial for disease transmission even after treatment. Advanced molecular diagnostic tools like PCR and serological tests are based on understanding the parasite’s biochemical markers (Sundar & Singh, 2018).

C. Drug Resistance and Disease Progression

Pentavalent antimonials, once the first-line treatment, have become ineffective in many endemic regions due to parasite resistance (Croft et al., 2006). Studying genetic mutations in Leishmania helps predict treatment failures and design targeted therapies.

2. Importance of Treatment Strategies

Timely and effective treatment is essential to prevent complications, reduce transmission, and ultimately eliminate leishmaniasis. The importance of understanding treatment strategies includes:

A. Optimizing First-Line and Combination Therapies

Liposomal Amphotericin B (LAmB) has become the preferred treatment for VL, but high costs and cold-chain requirements limit its use in resource-poor settings (Sundar & Singh, 2018). Miltefosine, the first oral drug, is widely used but faces emerging resistance. Combination therapies including Amphotericin B with Miltefosine reduces treatment duration and resistance risk (Burza et al., 2018).

B. Addressing Drug Resistance and Toxicity

Resistance to pentavalent antimonials has made them obsolete in regions like India. Amphotericin B toxicity (renal side effects) limits its prolonged use. Research on new drug targets, nanomedicine, and immunotherapy is crucial to overcome these challenges (Croft & Olliaro, 2011).

C. Need for a Leishmaniasis Vaccine

There is no licensed vaccine exists for human leishmaniasis. Several experimental vaccines, including recombinant protein vaccines and live-attenuated Leishmania, are under development (Hotez et al., 2020). A vaccine combined with vector control could be a sustainable strategy for elimination.

Objective

The primary objective of this study report is to provide a comprehensive understanding of Leishmaniasis, focusing on its pathology, transmission, clinical manifestations, and emerging treatment strategies. The specific objectives include:

-

Understanding the Pathology of Leishmaniasis

To explore the etiology and epidemiology of Leishmaniasis, including its global prevalence and endemic regions.

To analyse the life cycle of Leishmania parasites and their interaction with the host immune system.

To examine the different clinical forms of Leishmaniasis (cutaneous, mucocutaneous, and visceral) and their pathological effects on the human body.

-

Investigating Current and Emerging Treatment Approaches

To review the traditional treatment options, including antimonial drugs, amphotericin B, and miltefosine, along with their effectiveness and limitations.

To evaluate emerging therapies, such as novel drug formulations, combination therapies, immunotherapies, and vaccine developments.

To assess the challenges in drug resistance, accessibility, and affordability of Leishmaniasis treatment in endemic regions.

-

Exploring Future Perspectives in Leishmaniasis Management

To discuss advancements in molecular research and how they contribute to new drug targets.

To analyse the role of vector control, public health policies, and community awareness in the prevention and management of Leishmaniasis.

To highlight ongoing clinical trials and research efforts aimed at improving treatment outcomes and eradicating the disease.

By achieving these objectives, this report aims to contribute to a better understanding of Leishmaniasis pathology and treatment innovations, ultimately aiding in the development of more effective control and eradication strategies.

Pathology of Leishmaniasis

A. Entry and Establishment in the Host

There are various route of establishment of the parasite in the host body discussed in below statement.

- I.

Transmission: Leishmania promastigotes are introduced into the host’s skin through the bite of an infected sandfly.

- II.

Macrophage Infection: Promastigotes are phagocytosed by macrophages but resist destruction by preventing phagolysosomal fusion.

- III.

Amastigote Transformation: Inside macrophages, promastigotes differentiate into amastigotes, which multiply and cause cell rupture.

- IV.

Dissemination: Released amastigotes infect new macrophages, spreading the infection within skin, mucosa, or internal organs, depending on the species.

B. Clinical Forms and Pathological Manifestations

a. Cutaneous Leishmaniasis (CL)

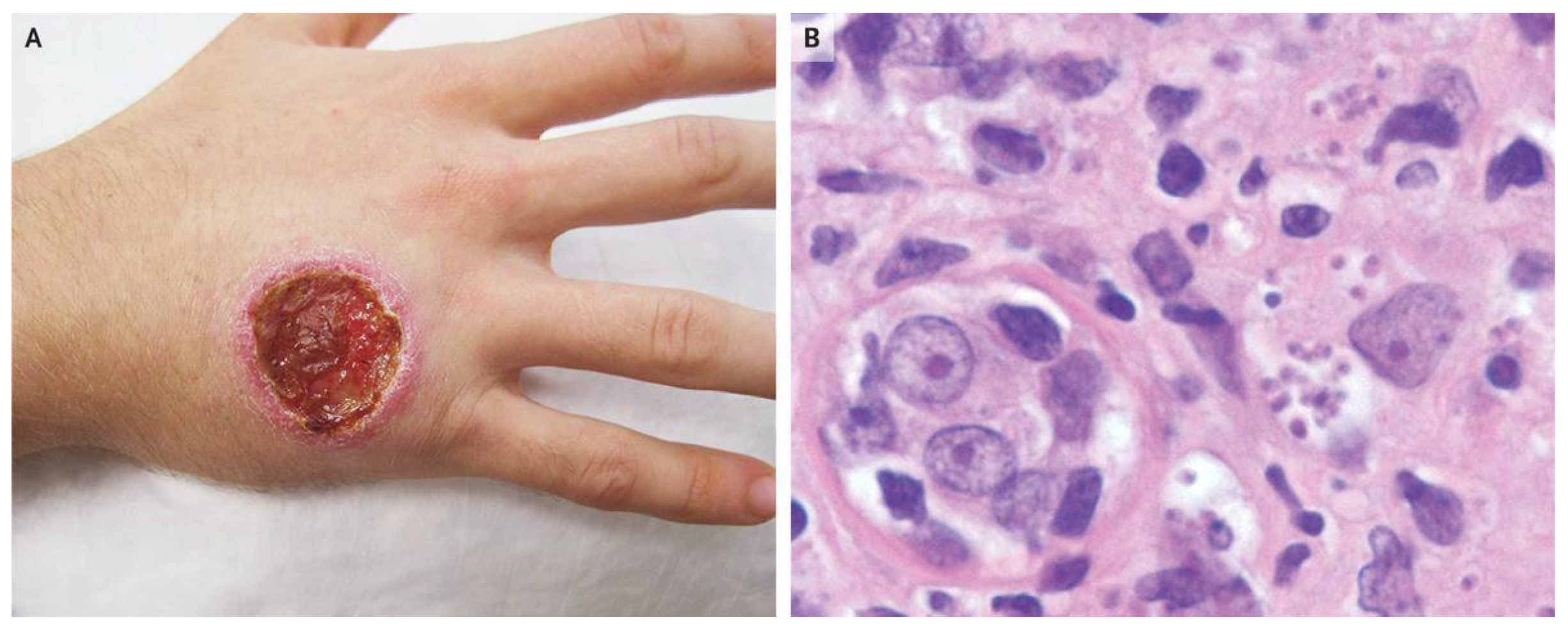

Figure 2.

Sign of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. B represents a punch-biopsy specimen of the edge of the ulcer showed a dense infiltrate of lymphocytes and histiocytes containing intracellular organisms consistent with leishmania amastigotes.

Figure 2.

Sign of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. B represents a punch-biopsy specimen of the edge of the ulcer showed a dense infiltrate of lymphocytes and histiocytes containing intracellular organisms consistent with leishmania amastigotes.

It Caused by species such as L. major, L. tropica, and L. mexicana.

Pathology: Localized skin lesions due to macrophage lysis, chronic inflammation, and granuloma formation.

Histopathology: Infiltration of lymphocytes, macrophages, and plasma cells, with necrosis in severe cases.

Healing Process: Lesions may ulcerate and eventually heal with scarring, but chronic forms can persist.

b. Mucocutaneous Leishmaniasis (MCL)

Figure 3.

Progress of Mucocutaneous Leishmaniasis.

Figure 3.

Progress of Mucocutaneous Leishmaniasis.

It caused by L. braziliensis complex.

Pathology: Destruction of mucosal tissues in the nose, throat, and oral cavity due to excessive inflammatory responses.

Histopathology: Extensive tissue damage, necrosis, and secondary bacterial infections due to persistent immune activation.

Complications: Severe disfigurement and airway obstruction in advanced cases.

c. Visceral Leishmaniasis (VL or Kala-azar)

Figure 4.

View of a young boy suffering from visceral leishmaniasis with enlarged liver and spleen.

Figure 4.

View of a young boy suffering from visceral leishmaniasis with enlarged liver and spleen.

It caused by L. donovani and L. infantum (chagasi).

Pathology: Systemic infection affecting the spleen, liver, bone marrow, and lymph nodes.

Histopathology:

Spleen & Liver: Hyperplasia of mononuclear phagocyte system, hepatosplenomegaly.

Bone Marrow: Pancytopenia due to parasite infiltration leading to anemia, leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia.

Lymph Nodes: Granuloma formation, fibrosis, and parasite persistence.

Complications: Severe immunosuppression, secondary infections, and organ failure if untreated.

d. Post-Kala-Azar Dermal Leishmaniasis (PKDL)

Figure 5.

Symptoms of Post-Kala-Azar Dermal Leishmaniasis.

Figure 5.

Symptoms of Post-Kala-Azar Dermal Leishmaniasis.

It occurs after VL treatment, caused by L. donovani.

Pathology: Chronic skin involvement with macular, papular, or nodular lesions harboring parasites.

Histopathology: Dermal infiltration of macrophages and plasma cells with persistent parasites.

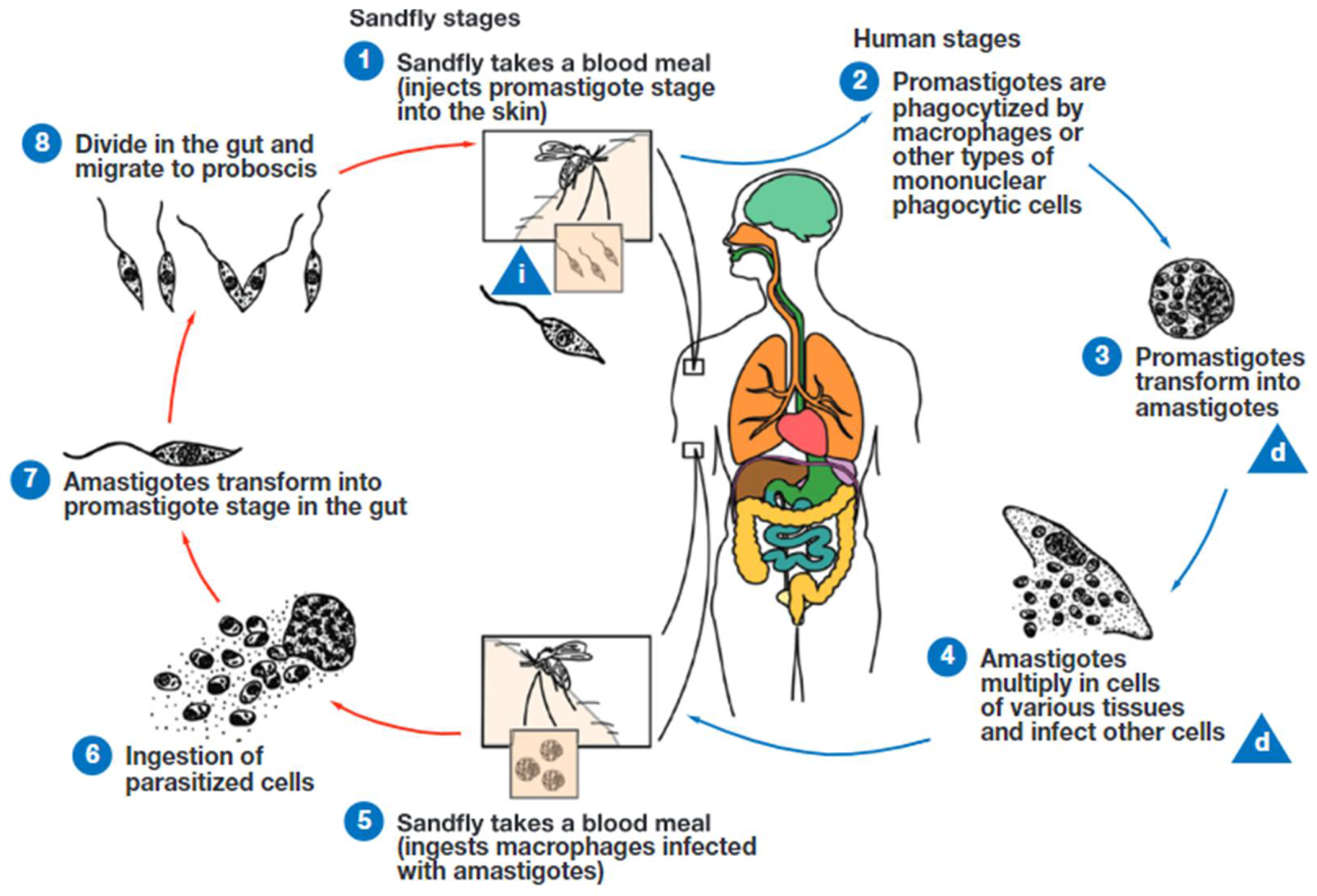

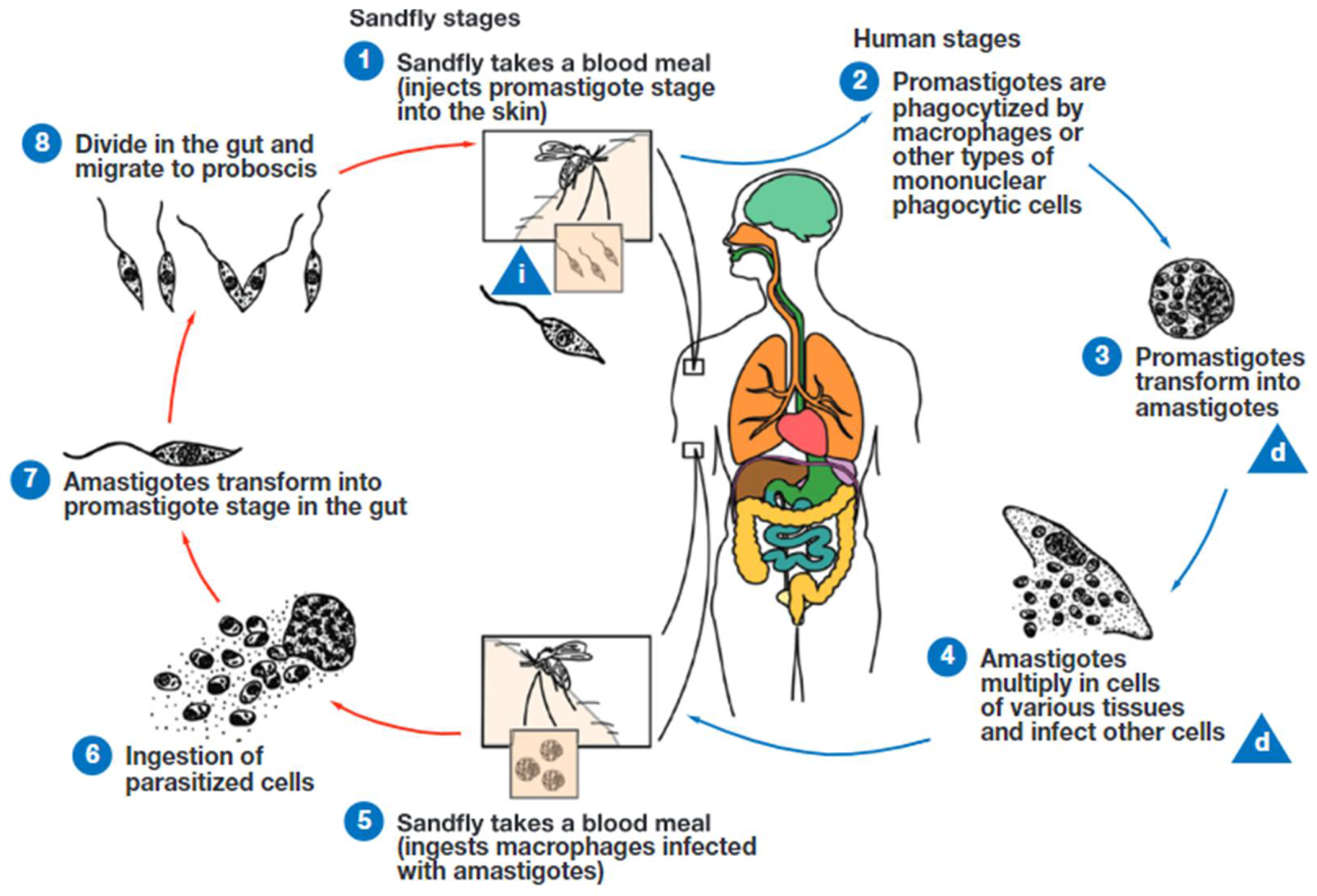

Figure 6.

Life cycle of Leishmania species. Leishmania is transmitted by the bite of infected female phlebotomine sand flies. The sand flies release the infective stage (i) (metacyclic promastigotes) during blood meals (1). Promastigotes that reach the puncture wound are phagocytized by macrophages (2) and other types of mononuclear phagocytic cells. Promastigotes transform into amastigotes, the tissue stage of the parasite (3), which multiply by binary division and proceed to infect other mononuclear phagocytic cells (4). The parasites are carried to other body sites in the infected monocytes. Sand flies become infected by ingesting infected cells during blood meals (5, 6). In the gut of the sand flies, amastigotes transform into procyclic promastigotes. The procyclic promastigotes transform into nectomonad trypomastigotes and then leptomonad promastigotes (7). The leptomonad promastigotes replicate by binary fission in the gut of the fly (8). Leptomonad promastigotes migrate to the proboscis of the fly and transform into infective metacyclic promastigotes. The cycle continues when the fly takes a blood meal. d, diagnostic stage. Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Figure 6.

Life cycle of Leishmania species. Leishmania is transmitted by the bite of infected female phlebotomine sand flies. The sand flies release the infective stage (i) (metacyclic promastigotes) during blood meals (1). Promastigotes that reach the puncture wound are phagocytized by macrophages (2) and other types of mononuclear phagocytic cells. Promastigotes transform into amastigotes, the tissue stage of the parasite (3), which multiply by binary division and proceed to infect other mononuclear phagocytic cells (4). The parasites are carried to other body sites in the infected monocytes. Sand flies become infected by ingesting infected cells during blood meals (5, 6). In the gut of the sand flies, amastigotes transform into procyclic promastigotes. The procyclic promastigotes transform into nectomonad trypomastigotes and then leptomonad promastigotes (7). The leptomonad promastigotes replicate by binary fission in the gut of the fly (8). Leptomonad promastigotes migrate to the proboscis of the fly and transform into infective metacyclic promastigotes. The cycle continues when the fly takes a blood meal. d, diagnostic stage. Image courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Pathogenesis

Even among the same species, leishmania infections can present with a variety of clinical manifestations. The development of disease has been found to be significantly influenced by the host immune response, particularly type 1 (Th1) and type 2 (Th2) helper T cells. The host immune response is biassed towards an anti-inflammatory Th2 phenotype in visceral Leishmania infections, with increased interleukin (IL)4 and IL10 and decreased interferon γ production (Bennett et al., 2016). Response stays localised to the lesion while the proinflammatory Th1 response dominates systemically. The basic Th1/Th2 paradigm in Leishmania pathogenesis has been expanded to incorporate responses mediated by Th17 cells and the inflammasome thanks to recent evidence (Tian et al., 2017). Leishmania is less significantly controlled by the humoral immune response. Visceral illness patients may have detectable Leishmania antibodies, but these are not enough to eradicate the infection (Galvao-Castro et al., 1984).

Visceral Leishmaniasis

Leishmania disease's most deadly form is visceral leishmaniasis, sometimes referred to as kala-azar. Although VL has been reported in immunocompromised persons, it is more frequently linked to L donovani (East Africa, India) and L infantum (Mediterranean, Middle East, and the Americas) (Alvar et al., 2008; van Griensven & Diro, 2012). Prolonged fever, weight loss, pancytopenia, hypergammaglobulinemia, and hepatosplenomegaly are the usual pentad of VL symptoms (Badaro et al., 1986). The start of symptoms is subtle and frequently happens months to years after infection in the 5% of infected people who go on to develop clinical illness (Pearson et al., 1992). VL can develop into haemorrhage, cachexia, and bone marrow failure if treatment is not received. VL mortality may be increased in those with immunocompromise (such as HIV or immunosuppression brought on by medication) (Lyons et al., 2003). According to current guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America, universal screening is not advised due to the low frequency in the United States (Aronson et al., 2016). Patients who suffer from VL may also be susceptible to post-kala-azar cutaneous leishmaniasis, depending on the area. Areas of Africa are at the highest risk, while India and the Americas are at the lowest (Rahman et al., 2010; Zijlstra et al., 2000).

Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

Leishmaniasis is found worldwide in areas where it is endemic and is categorized into Old World and New World diseases. Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis is primarily linked to the species L major, L tropica, and L aethiopica; however, L donovani and L infantum, while more commonly associated with visceral leishmaniasis, can also lead to isolated cutaneous lesions (Siriwardana et al., 2007). In the Americas, New World cutaneous leishmaniasis is primarily caused by Leishmania species from the subgenus Vianna, most notably L braziliensis, and also includes species from the genus Endotrypanum and Leishmania, such as L mexicana. After a phlebotomine sand fly feeds on blood, a painless papule or dermal nodule may emerge anywhere from 2 weeks to several months post-bite (Weigle & Saravia, 1996). Typically, this nodule expands gradually in a concentric manner, resulting in a central ulcerated cavity. Despite its striking appearance, the ulcer tends to be painless. Several informal terms have been used to describe the lesions of cutaneous leishmaniasis, such as “pizza-like,” which refers to the elevated outer edge of the epithelium surrounding the ulcerated center filled with granulation tissue and fibrin (Davies et al., 1995). Those who recover from cutaneous leishmaniasis often have a typical scar, characterized by changes in pigmentation and a central area that is lower than the surrounding skin. Recovery from the disease is linked to a decreased risk of reinfection by the same Leishmania species, though individuals still remain susceptible to the possibility of relapse or new infections(Weigle et al., 1993). In studies of three patient groups in Brazil, Colombia, and Peru, recurrence rates were observed at 2.7% of 369 cases, 2.0 per 100 person-years, and 2.9 per 100 person-years, respectively. The cutaneous manifestations vary partly according to the species that caused the infection (Herwaldt et al., 1992). A study on New World cutaneous leishmaniasis indicated that L braziliensis produced larger lesions, less complete reepithelization, and longer recovery times compared to L mexicana.

Mucocutaneous LEISHMANIASIS

Mucocutaneous symptoms of Leishmania are typically associated with the new world subgenus Vianna (L braziliensis, L panamensis, and L guyanensis), while less frequently seen in old world species (L tropica, L major, and L donovani). Various case reports indicate that old world mucocutaneous leishmaniasis (ML) tends to be milder than its New World counterparts. In particular, the old-world types show a reduced incidence of nasal cavity involvement compared to the New World forms (15% versus 90%) and a more favourable treatment outcome (82%). The typical mucosal lesions in ML arise in 1% to 5% of those infected in areas where the Vianna subgenus is endemic, and they usually appear after the resolution of cutaneous lesions. In a smaller percentage of cases (10%–20%), mucosal lesions may emerge without any preceding or simultaneous skin lesions. Mucosal lesions typically manifest as destructive ulcerations or inflammatory swelling in the nasal cavity. In severe cases, ML can lead to lasting disfigurement or airway obstruction due to pharyngeal involvement. Given that mucosal lesions can develop months or even years after the treatment and resolution of the cutaneous form, patients diagnosed with or suspected of having infections from the Vianna subgenus should be monitored closely. Emerging research suggests that Leishmania RNA virus-1 (LRV1) may influence the severity of mucocutaneous disease. Initially noted in L guyanensis, LRV1 was found to enhance toll-like receptor 3 (TRL3)-mediated cytokine production and increase parasitemia in an animal model. This virus has since been identified in other Leishmania species, although the clinical relevance of LRV1 detection is still to be established.

Current Treatment Strategies in India

First-Line Treatment Options

Amphotericin B (Fungizone; Mysteclin-F; AmBisome) and miltefosine (Impavido) are the two anti-leishmanial medications currently licensed by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Pentavalent antimony, paromomycin, azole drugs, and pentamidine are other therapy alternatives. Depending on the Leishmania species, infection site, and relapse monitoring period, these treatments have shown varying degrees of clinical success. It is crucial to remember that clinical cure—such as wound healing, improved blood counts, or the elimination of splenomegaly—does not imply parasitological cure when assessing therapy response. When cultured after clinical remission, scar tissue from lymph nodes and cutaneous lesions has shown live organisms. Miltefosine, which was initially created as an antineoplastic medication, was approved by the FDA in 2014 to treat VL brought on by L. donovani as well as CLs or MLs brought on by L. braziliensis, L. guyanensis, and L. panamensis. Miltefosine's clinical cure rates for VLs were initially high in India, but later trials conducted there and in other nations have shown a cure rate of more than 75% six to twelve months after therapy. Miltefosine's efficacy in treating New World CL varies to a similar extent; research conducted in Colombia showed a cure rate of over 90%, while trials conducted in Guatemala showed a cure rate of only 53%. The variation in clinical efficacy is suspected to be due in part to species and strain variation between these regions. Among anti-leishmanial drugs documented in the World Health Organization (WHO) List of Essential Medicines, miltefosine is the only oral treatment.

The FDA has approved liposomal amphotericin B, a polyene antibiotic, to treat visceral leishmaniasis in the US. It works by disrupting the parasite cell membrane by inhibiting the formation of ergosterol. In two European clinical trials, liposomal amphotericin B showed a 100% cure rate when used in regimens with a total dose greater than 21 mg/kg, according to papers that were filed to the FDA. At different dosages (6–20 mg/kg), additional research conducted in Brazil, Kenya, and India showed comparable levels of clinical effectiveness (83%–100%). Liposomal amphotericin B has shown clinical efficacy in cutaneous and mucocutaneous diseases, despite not being authorised for the treatment of nonvisceral diseases. Pentavalent antimony (SbV) has been used to treat VL, ML, and CL since World War II. The SbV can be diluted in saline and given intravenously, or it can be given as a series of intralesional or intramuscular injections. Although the precise mechanism of action is still unclear, several possible mechanisms have been studied, including direct suppression of glycolysis, stimulation of the host immunological response, and inhibition of parasitic trypanothione reductase by trivalent antimony (i.e., the reduced form of SbV). With the exception of some Indian districts where resistance rates of greater than 40% have been found, the SbV treatment may be taken into consideration for the first-line treatment of VLs. In 2020, the company stopped producing sodium stibogluconate, a formulation of SbV, which was previously available in the United States through an Investigational New Drug procedure from the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Drug Services.

Emerging Therapies and Drug Resistance Concerns

As discussed above, every available antileishmanial drug has significant drawbacks. Thus, there is an urgent need for new antileishmanial drugs that are oral, safe, and affordable, with shorter duration of treatment.

CO2 laser administration and thermotherapy

In order to directly eradicate the Leishmania parasites, CL is treated in Iran with CO2 laser and thermotherapy, which deliver external heat to the afflicted tissues in order to specifically harm the parasites. CO2 laser treatment is an affordable and effective first therapy for leishmaniasis, according to (Asilian et al., 2004). The Handheld Exothermic Crystallisation Thermotherapy for CL (HECT-CL) device, a low-cost heat pack that provides safe, dependable, and renewable heat conduction, was introduced by (Sadeghian et al., 2007). With a 60% overall conclusive clinical cure rate, the HECT-CL treatment is a viable choice. Skin lesions might heal more quickly when direct heat is applied. After a single treatment session, the CO2 laser treatment was more effective (definitive cure 93.7%) than a combination of cryotherapy and intralesional SbV in treating CL, and the healing period was shorter (6 weeks vs. 12 weeks) (Sadeghian et al., 2007). According to certain OWCL studies, thermotherapy outperformed intralesional SbV treatment in terms of cure rate, with similar or fewer side effects (Roatt et al., 2020).

Cryotherapy

Using a CO2 cryo-machine, cryotherapy was first tested on 30 L. major-infected patients in Saudi Arabia (Bassiouny et al., 1982). There was a 100% cure rate with no recurrence or obvious scarring after 4–5 weeks. Liquid nitrogen at a temperature of -195°C is used in cryotherapy (Negera et al., 2012). Cryotherapy showed over 95% efficacy when applied once or twice a week to leishmania lesions. Ice crystals that form inside parasites cause membrane lysis and localised ischaemic necrosis, which ultimately leads to their demise. Swelling, redness, and either hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation at the treatment site were among the adverse effects noted. Liquid nitrogen can therefore be regarded as one of the CL therapy alternatives (Chakravarty & Sundar, 2019).

Topical Nitric Oxide Derivates

Experimental animals have demonstrated the capacity of nitric oxide (NO), which is generated by activated murine macrophages, to impede the development and induce cell death of a variety of infections, including Leishmania major (Bassiouny et al., 1982). All lesions were completely healed, and new skin was grown in CL patients after using an S-nitroso-N-acetyl penicillamine (SNAP) cream (Negera et al., 2012). On the other hand, only 37.1% of Colombian patients with CL caused by Leishmania (V.) panamensis experienced cure in a clinical trial that applied a topical nano-fibre nitric oxide (NO) releasing patch for 12 hours a day for 20 days. Nevertheless, the low rate of side effects and the ease of topical application justify the necessity of more study and the creation of novel nitric oxide release mechanisms for the management of CL (Chakravarty & Sundar, 2019).

Novel Drugs Under Research

Liposome Nanoparticles

Bilayer phospholipids form the nanoscale spherical vesicles known as liposome nanoparticles, which offer aqueous support for the adherence of hydrophilic and lipophilic medications (Momeni et al., 2013). Liposomes can lower the dosage and frequency of therapeutic delivery while maintaining and regulating drug release. Liposomes are a developing therapeutic approach and are frequently used in the exploration of several anticipated medicinal drugs (Schwendener et al., 2011).

Polymeric Nanoparticles (PNP)

Colloidal particles that are both biocompatible and biodegradable make up these nanoparticles. They range in size from 1 to 1000 nm (Carreiró et al., 2020). PNPs result in better cellular dynamics, biodegradability, regulated drug distribution, and increased bioavailability. PNPs may use one of three methods to deliver medications to the intended locations (Sirisha & D’Souza, 2016). First, by means of an enzymatic reaction that causes the polymer to break down at the desired site, releasing the medication (Müller et al., 2000; Tiwari et al., 2023). Second, by causing the PNP to expand, which is followed by hydration and drug release through diffusion. Thirdly, by dissociating the medication from the polymer. Poly DL-lactide-co-glycolide (PLGA) nanospheres were created by nanoprecipitation and then surface-modified with mannose, mannan, or mannosamine groups via a carbodiimide procedure. These nanocarriers are taken up by murine primary macrophages via clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Macrophages were activated and produced pro-inflammatory cytokines when they were co-cultured with nanospheres functionalised with carbs. A single dosage of amphotericin B administered via mannan-functionalized nanospheres elicited a favourable response in mice with VL (Barros et al., 2015).

Nanotubes

Nanotubes are cylindrical hollow molecules made of inorganic and metallic materials. Several studies have been undertaken to demonstrate that nanotubes are good nanocarriers. The antileishmanial activity of amphotericin B (AmB) in conjunction with carbon nanotubes was investigated. The authors discovered that this formulation outperformed free AmB in terms of targeted killing of L. donovani. To reduce medication-induced toxicity, in another study combined linked AmB, an antileishmanial agent, with functionalized carbon nanotubes (f-CNTs). This formulation inhibited parasite growth more effectively than AmB, however, significant renal and hepatic toxicity was reported in the kidney and liver of mice. In an in-vitro study, the f-Comp-AmB showed significantly enhanced effectiveness against intracellular amastigotes of L. donovani, with a 12.2-fold decrease in IC50 values compared to standard AmB. Conversely, f-Grap-AmB and f-CNT-AmB, other modified carbon nanomaterials, exhibited only 7.98- and 6.71-fold improvements, respectively, in their in vitro antileishmanial activity compared to conventional AmB.

Phytoproducts as Drug Targets

Using plants was associated with healing in ancient Mediterranean culture. Later advances in the chemical sciences allowed for the separation and extraction of components having a plant origin. Phytomedicines are medications derived from plant extracts. The biological activity of plant extracts has been associated with a variety of substances, including terpenoids, alkaloids, flavonoids, phenylpropanoids, and steroids (Sundar & Singh, 2018). To get a herbal medicine or an isolated active ingredient, several research methods may be employed, such as assessing the plant's toxicity, chemical makeup, traditional use, or a combination of numerous aspects. It is obvious that plants could yield novel antiprotozoal medications. Today, the demand for low-cost anti-leishmanial drugs with fewer adverse effects has led to the continued success of phytotherapy. Plant extracts are also pharmacologically suitable for use as medications due to their chemical diversity. Numerous recent studies have been published that support the use of medicinal herbs to treat leishmaniasis. Kalanchoe pinnata, which mostly includes triterpenes, sterols, and flavonoids, remains the subject of the most noteworthy research in this field. The literature describes a large number of substances with strong antileishmanial action and secondary metabolites. Oral administration of the leishmanicidal chemical obtained from plants has been shown in experimental investigations to have leishmanicidal activity equivalent to that of SbV without any negative side effects. Kalanchoe pinnata may be a safe and effective oral treatment for CL, according to research data. Additionally, by inducing programmed cell death, the extract from aloe vera leaves has demonstrated possible antileishmanial action. It has been shown that naphthoquinone and plumbagin inhibit L. donovani trypanothione reductase and induce cell death mediated by the mitochondria. One plant secondary metabolite that may have antileishmanial properties is naphthoquinone. Additional antileishmanial compounds need to be found. Many compounds derived from plants have shown promise in combatting leishmaniasis.

Conclusions

Ironically, a large number of VL patients were spared by SbV (urea stibamine), which was initially identified in 1920 and utilised to treat VL in Assam, Bengal, and other Indian states. With the exception of ISC, SbV remains the primary treatment for leishmaniasis, which is prevalent in 99 countries worldwide. Even though it has been associated to major side effects like cardiotoxicity and mortality, it is nevertheless routinely used internationally because there was no alternative option. Ironically, oral miltefosine, PM, and LAmB were not made available for the treatment of leishmaniasis for 75–85 years. There is an urgent need for new antileishmanial medications that are safe, affordable, stable at room temperature, and ideally oral with short regimens. At least in the ISC, LAmB is free to use in public health facilities due to a gift from the manufacturer and the World Health Organisation that has been in place for more than ten years.

Treatment of post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL) and HIV/VL co-infection, human reservoirs for leishmaniasis is very unsatisfactory. For the treatment of PKDL, either 120 days of SbV over four months or 60–80 infusions of AmB again for the duration of 4–5 months, was recommended initially. However, these are extremely unsatisfactory and prolonged regimens, with potentially toxic drugs; These modes of PKDL treatment are now abandoned in India. After miltefosine was approved for the treatment of VL in India, based on a small randomized multicentre study using 12 weeks of miltefosine, it was recommended by WHO that oral miltefosine be used for 12 weeks for the treatment of PKDL. However, We need an urgent treatment regimen for PKDL, which is a safer, shorter, and affordable treatment for these patients; sadly, we have nothing absolutely safe for them. We need to develop either single or multi-drug therapy with newly developed drugs.

As discussed above for the treatment of VL/CL/MCL, we need new antileishmanial compounds and, ways of therapy. There are several new compounds, already in advanced stage of development. But for use in humans, we need data coming out of well-designed clinical trials. Unfortunately, at the moment, there is only one compound in phase 2 clinical trial. The versatility and benefits of colloidal drug carriers such as emulsions, liposomes, and nanoparticles in treating parasite infections are of great interest. Nanoparticles can offer treatment for macrophage-mediated illnesses. Multidrug therapy can prevent drug resistance by reducing duration, doses, and toxicity. Numerous metabolic pathways are being studied as potential targets for drug discovery, targeting structures and ligands to discover new antileishmanial treatments.

Leishmaniasis is a serious and potentially life-threatening disease caused by protozoan parasites of the genera Leishmania and Endotrypanum. Naturally endemic to tropical and subtropical parts of the world, global travel has made leishmaniasis a worldwide medical and public health burden. There are 3 main clinical presentations of the disease: cutaneous, mucocutaneous, and visceral. Rapid diagnosis and species-level identification is crucial for successful management and prevention of morbidity. Serologic methods such as rapid antigen tests allow for non-invasive diagnosis of VL and initiation of therapy. Despite advances in molecular detection, diagnosis of CL still requires careful microscopic examination and integration of epidemiologic and clinical data. In situations of cutaneous disease, exclusion of species associated with ML is important to guide therapy and clinical follow-up. Historically, species-level identification has been performed by isoenzyme analysis, a time-consuming method relying on culturing the Leishmania parasite. Today, molecular methods are shortening the time to result by testing directly from clinical samples and using targets with increased diagnostic specificity.