Submitted:

12 March 2025

Posted:

13 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

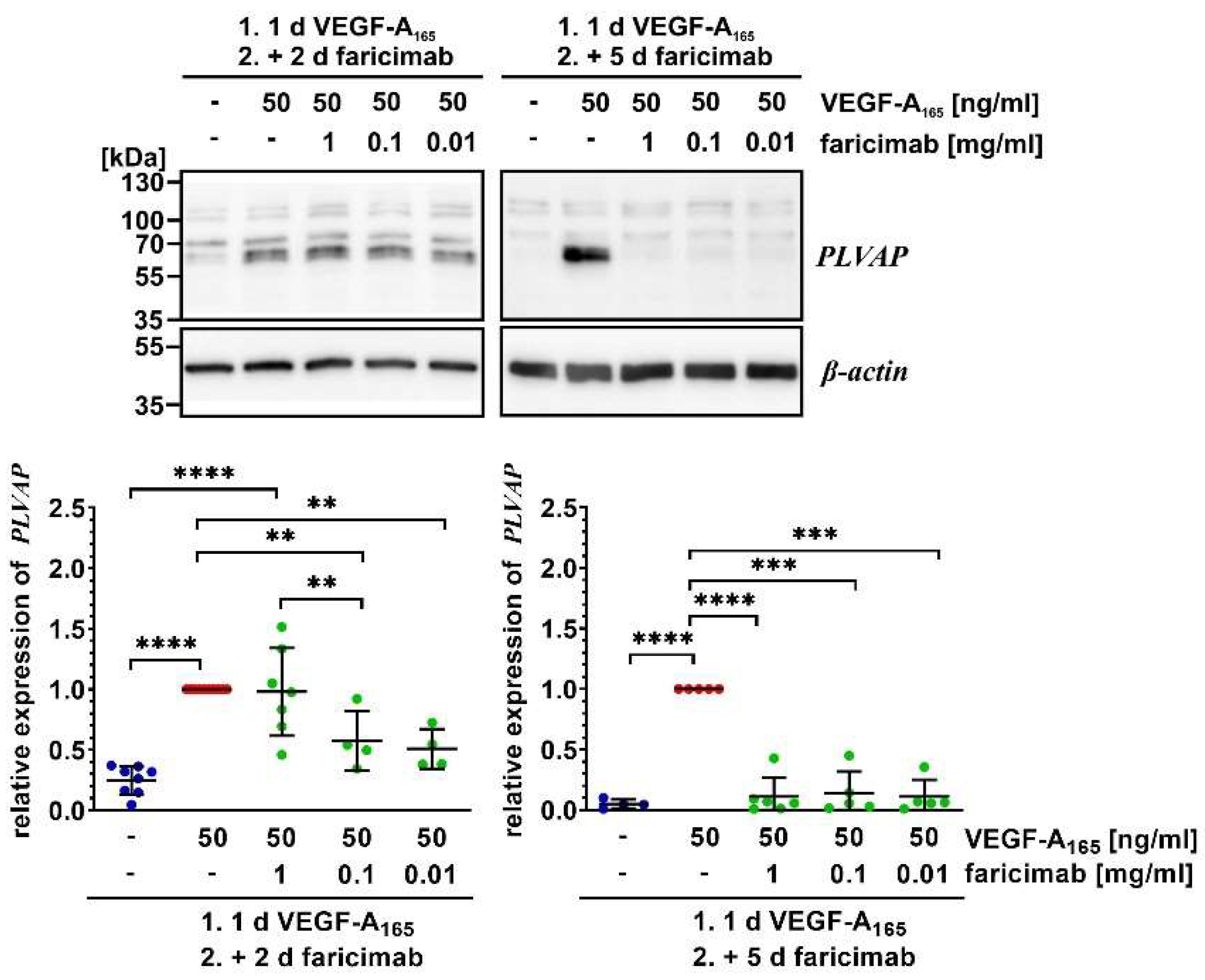

VEGF‑A165-induced persistent dysfunction of the barrier formed by immortalized bovine retinal endothelial cells (iBREC) is only transiently reverted by inhibition of VEGF‑A-driven signaling. As angiopoietin‑2 (Ang‑2) enhances the detrimental action of VEGF‑A165, we studied if binding of both growth factors by the bi-specific antibody faricimab sustainably reverts barrier impairment. Confluent monolayers of iBREC were exposed to VEGF‑A165 for one day before 10-1000 µg/ml faricimab were added for additional five days. To assess barrier function, we performed continuous electric cell-substrate impedance, i.e. cell index, measurements. VEGF‑A165 significantly lowered the cell index values which recovered to normal values within hours after addition of faricimab. Stabilization lasted for two to five days depending on the antagonist’s concentration. As determined by Western-blotting, only ≥100 µg/ml faricimab efficiently normalized altered expression of claudin‑1 and claudin‑5, but all concentrations prevented further increase of plasmalemma vesicle-associated protein induced by VEGF‑A165; these proteins are involved in barrier stability. Secretion of Ang‑2 by iBREC was significantly higher after exposure to VEGF‑A165, and strongly reduced by faricimab even below basal levels; aflibercept was significantly less efficient. Taken together, faricimab sustainably reverts VEGF‑A165-induced barrier impairment, and protects against detrimental actions of Ang‑2 by lowering its secretion.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. General Information

2.2. Faricimab Strongly Suppressed Higher Secretion of Ang-2 by VEGF-A165-Treated iBREC

2.3. Faricimab Efficiently Reverted VEGF-A165-Induced Barrier Impairment

2.4. Faricimab Reverted VEGF-A165-Induced Changes of Expression of Claudin-1 and PLVAP

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Antibodies and Reagents

4.2. Cultivation of iBREC

4.3. Cell Index Measurements

4.4. Measurement of VGEF-A165, Ang-2 and IL-6 by ELISA

4.5. Western Blot Analyses of Protein Extracts

4.6. Statistical Analyses

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement and Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AJ | adherens junction |

| Ang-2 | angiopoietin-2 |

| CI | cell index |

| EC | endothelial cells |

| ECGM | endothelial cell growth medium |

| FBS | fetal bovine serum |

| hEGF | human epidermal growth factor |

| HRP | horseradish peroxidase |

| HuREC | human retinal endothelial cells |

| (i)BREC | (immortalized) bovine retinal endothelial cells |

| PLVAP | plasma lemma vesicle associated protein |

| REC | retinal endothelial cells |

| TJ | tight junction |

| VEcadherin | vascular endothelial cadherin |

| VEGF-A | vascular endothelial growth factor-A |

| VEGFR | vascular endothelial growth factor receptor |

| WB | Western blot analyses |

References

- Antonetti, D.A.; Barber, A.J.; Hollinger, L.A.; Wolpert, E.B.; Gardner, T.W. Vascular endothelial growth factor induces rapid phosphorylation of tight junction proteins occludin and zonula occludens 1. J Biol. Chem 1999, 274, 23463–23467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deissler, H.; Deissler, H.; Lang, G.E. Inhibition of VEGF is sufficient to completely restore barrier malfunction induced by growth factors in microvascular retinal endothelial cells. Br J Ophthalmol 2011, 95, 1151–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaum, T.; Xu, Q.; Joussen, A.M.; Clemens, M.W.; Qin, W.; Miyamoto, K.; Hassessian, H.; Wiegand, S.J.; Rudge, J.; Yancopoulos, G.D.; Adamis, A.P. VEGF-initiated blood-retinal barrier breakdown in early diabetes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2001, 42, 2408–2413. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Eichmann, A.; Simons, M. VEGF signaling inside vascular endothelial cells and beyond. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2012, 24, 188–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deissler, H.L.; Stutzer, J.-N.; Lang, G.K.; Grisanti, S.; Lang, G.E.; Ranjbar, M. VEGF receptor 2 inhibitor nintedanib completely reverts VEGF-A165-induced disturbances of barriers formed by retinal endothelial cells or long-term cultivated ARPE-19 cells. Exp Eye Res 2020, 194, 108004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez, S.; McCollum, G.W.; Bretz, C.A.; Yang, R.; Capozzi, M.E.; Penn, J.S. Modulation of VEGF-induced retinal vascular permeability by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-β/δ. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2014, 55, 8232–8240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wisniewska-Kruk, J.; Hoeben, K.A.; Vogels, I.M.; Gaillard, P.J.; Van Noorden, C.J.; Schlingemann, R.O.; Klaassen, I. A novel co-culture model of the blood-retinal barrier based on primary retinal endothelial cells, pericytes and astrocytes. Exp Eye Res 2012, 96, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, M.; Fu, H.; Cheng, H.; Cao, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Mou, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Ke, Y. A dynamic real-time method for monitoring epithelial barrier function in vitro. Anal Biochem 2012, 425, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bischoff, I.; Hornburger, M.C.; Mayer, B.A.; Beyerle, A.; Wegener, J.; Fürst, R. Pitfalls in assessing microvascular endothelial barrier function: impedance-based devices versus the classic macromolecular tracer assay. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 23671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deissler, H.L.; Lang, G.K.; Lang, G.E. Inhibition of single routes of intracellular signaling is not sufficient to neutralize the biphasic disturbance of a retinal endothelial cell barrier induced by VEGF-A165. Cell Physiol Biochem 2017, 42, 1493–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deissler, H.; Deissler, H.; Lang, G.K.; Lang, G.E. Generation and characterization of iBREC: novel hTERT-immortalized bovine retinal endothelial cells. Int J. Mol Med 2005, 15, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deissler, H.L.; Rehak, M.; Busch, C.; Wolf, A. Blocking of VEGF-A is not sufficient to completely revert its long-term effects on the barrier formed by retinal endothelial cells. Exp Eye Res 2022, 216, 108945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deissler, H.L.; Rehak, M.; Wolf, A. Impairment of the retinal endothelial cell barrier induced by long-term treatment with VEGF-A165 no longer depends on the growth factor’s presence. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, M.; Li, Y.; Baccouche, B.; Kazlauskas, A. VEGF induces expression of genes that either promote or limit relaxation of the retinal endothelial barrier. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 6402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, N.; Damico, L.; Shams, N.; Lowman, H.; Kim, R. Development of ranibizumab, an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antigen binding fragment, as therapy for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Retina 2006, 26, 859–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudreault, J.; Gunde, T.; Floyd, H.S.; Ellis, J.; Tietz, J.; Binggeli, D.; Keller, B.; Schmidt, A.; Escher, A. Preclinical pharmacology and safety of ESBA1008, a single-chain antibody fragment, investigated as potential treatment for age related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2012, 53, 3025, ARVO Annual Meeting Abstract, Fort Lauderdale, USA, March 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Deissler, H.L.; Rehak, M.; Lytvynchuk, L. VEGF-A165a and angiopoietin-2 differently affect the barrier formed by retinal endothelial cells. Exp Eye Res 2024, 247, 110062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangasamy, S.; Srinivasan, R.; Maestas, J.; McGuire, P.G.; Das, A. A potential role for angiopoietin 2 in the regulation of the blood–retinal barrier in diabetic retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011, 52, 3784–3791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyre, J.J.; Williams, R.L.; Levis, H.J. A human retinal microvascular endothelial-pericyte co-culture model to study diabetic retinopathy in vitro. Exp Eye Res 2020, 201, 108293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regula, J.T.; Lundh von Leithner, P.; Foxton, R.; Barathi, V.A.; Cheung, C.M.; Bo Tun, S.B.; Wey, Y.S.; Iwata, D.; Dostalek, M.; Moelleken, J.; Stubenrauch, K.G.; Nogoceke, E.; Widmer, G.; Strassburger, P.; Koss, M.J.; Klein, C.; Shima, D.T.; Hartmann, G. Targeting key angiogenic pathways with a bispecific CrossMAb optimized for neovascular eye diseases. EMBO Mol Med 2016, 8, 1265-1288. https://doi.org/10.15252/emmm.201505889. Corrections in: EMBO Mol Med 2017 9, 985. https://doi.org/10.15252/emmm.201707895. EMBO Mol Med 2019, 11, e10666. [CrossRef]

- Holash, J.; Davis, S.; Papadopoulos, N.; Croll, S.D.; Ho, L.; Russell, M.; Boland, P.; Leidich, R.; Hylton, D.; Burova, E.; Ioffe, E.; Huang, T.; Radziejewski, C.; Bailey, K.; Fandl, J.P.; Daly, T.; Wiegand, S.J.; Yancopoulos, G.D.; Rudge, J.S. VEGF-Trap: A VEGF blocker with potent antitumor effects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2002, 99, 11393–11398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, C.; Tetzner, R.; Strunz, T.; Rittenhouse, K.D. Aflibercept suppression of angiopoietin-2 in a rabbit retinal vascular hyperpermeability model. Transl Vis Sci Technol 2023, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosma, E.K.; van Noorden, C.J.F.; Schlingemann, R.O.; Klaassen, I. The role of plasmalemma vesicle-associated protein in pathological breakdown of blood–brain and blood–retinal barriers: potential novel therapeutic target for cerebral edema and diabetic macular edema. Fluids Barriers CNS 2018, 15, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosma, E.K.; Darwesh, S.; Habani, Y.I.; Cammeraat, M.; Serrano Martinez, P.; van Breest Smallenburg, M.E.; Zheng, J.Y.; Vogels, I.M.C.; van Noorden, C.J.F.; Schlingemann, R.O.; Klaassen, I. Differential roles of eNOS in late effects of VEGF-A on hyperpermeability in different types of endothelial cells. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 21436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisniewska-Kruk, J.; van der Wijk, A.E.; van Veen, H.A.; Gorgels, T.G.; Vogels, I.M.; Versteeg, D.; Van Noorden, C.J.; Schlingemann, R.O.; Klaassen, I. Plasmalemma vesicle-associated protein has a key role in blood-retinal barrier loss. Am J Pathol 2016, 186, 1044–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluger, M.S.; Clark, P.R.; Tellides, G.; Gerke, V.; Pober, J.S. Claudin-5 controls intercellular barriers of human dermal microvascular but not human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2014, 33, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, C.; Rehak, M.; Hollborn, M.; Wiedemann, P.; Lang, G.K.; Lang, G.E.; Wolf, A.; Deissler, H.L. Type of culture medium determines properties of cultivated retinal endothelial cells: induction of substantial phenotypic conversion by standard DMEM. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.Y.; Haskova, Z.; Asik, K.; Baumal, C.R.; Csaky, K.G.; Eter, N.; Ives, J.A.; Jaffe, G.J.; Korobelnik, J.F.; Lin, H.; Murata, T.; Ruamviboonsuk, P.; Schlottmann, P.G.; Seres, A.I.; Silverman, D.; Sun, X.; Tang, Y.; Wells, J.A.; Yoon, Y.H.; Wykoff, C.C. YOSEMITE and RHINE investigators. Faricimab treat-and-extend for diabetic macular edema: 2-year results from the randomized phase 3 YOSEMITE and RHINE trials. Ophthalmology 2024, 131, 708–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strohl, L.L.; Zang, J.B.; Ding, W.; Manni, M.; Zhou, X.K.; Granstein, R.D. Norepinephrine and adenosine-5’-triphosphate synergize in inducing IL-6 production by human dermal microvascular endothelial cells. Cytokine 2013, 64, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lytvynchuk, L.; Nolte, K.L.; Deissler, H.L. Novel needle for intravitreal injections maintains activity of VEGF-binding proteins. ARVO Annual Meeting Abstract, Salt Lake City, USA, 6 May 2025.

- Dejana, E.; Tournier-Lasserve, E.; Weinstein, B.M. The control of vascular integrity by endothelial cell junctions: molecular basis and pathological implications. Dev Cell 2009, 16, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barton, W.A.; Tzvetkova-Robev, D.; Miranda, E.P.; Kolev, M.V.; Rajashankar, K.R.; Himanen, J.P.; Nikolov, D.B. Crystal structures of the Tie2 receptor ectodomain and the angiopoietin-2-Tie2 complex. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2006, 13, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisonpierre, P.C.; Suri, C.; Jones, P.F.; Bartunkova, S.; Wiegand, S.J.; Radziejewski, C.; Compton, D.; McClain, J.; Aldrich, T.H.; Papadopoulos, N.; Daly, T.J.; Davis, S.; Sato, T.N.; Yancopoulos, G.D. Angiopoietin-2, a natural antagonist for Tie2 that disrupts in vivo angiogenesis. Science 1997, 277, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scharpfenecker, M.; Fiedler, U.; Reiss, Y.; Augustin, H.G. The Tie-2 ligand angiopoietin-2 destabilizes quiescent endothelium through an internal autocrine loop mechanism. J Cell Sci 2005, 118, 771–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diack, C.; Avery, R.L.; Cheung, C.M.G.; Csaky, K.G.; Gibiansky, L.; Jaminion, F.; Gibiansky, E.; Sickert, D.; Stoilov, I.; Cosson, V.; Bogman, K. Ocular pharmacodynamics of intravitreal faricimab in patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration or diabetic macular edema. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2024, 13, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deissler, H.L.; Busch, C.; Wolf, A.; Rehak, M. Beovu, but not Lucentis impairs the function of the barrier formed by retinal endothelial cells in vitro. Sci Rep. 2022, 12, 12493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martos, A.; Koch, W; Jiskoot, W; Wuchner, K.; Winter, G.; Friess, W; Hawe, A. Trends on analytical characterization of polysorbates and their degradation products in biopharmaceutical formulations. J Pharm Sci 2017, 106, 1722–1735. [CrossRef]

- Bruns, A.F.; Shane, P.H.; Odell, A.F.; Jopling, H.M.; Hooper, N.M.; Zachary, I.C.; Walker, J.H.; Ponnambalam, S. Ligand-stimulated VEGFR2 signaling is regulated by co-ordinated trafficking and proteolysis. Traffic 2010, 11, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Zhang, H.; Hou, Y.; Wie, T.; Liu, J. Plasmalemma vesicle-associated protein: A crucial component of vascular homeostasis. Exp Ther Med 2016, 12, 1639–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, B.J.; Tse, D.; Stan. RV. Phorbol esters induce PLVAP expression via VEGF and additional secreted molecules in MEK1-dependent and p38, JNK and PI3K/Akt-independent manner. J Cell Mol Med 2019, 23, 920–933. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiello, L.P.; Avery, R.L.; Arrigg, P.G.; Keyt, B.A.; Jampel, H.D.; Shah, S.T.; Pasquale, L.R.; Thieme, H.; Iwamoto, M.A.; Park, J.E.; Nguyen, H.V.; Aiello, L.M.; Ferrara, N.; King, G.L. Vascular endothelial growth factor in ocular fluid of patients with diabetic retinopathy and other retinal disorders. N Engl J Med 1994, 331, 1480–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, S.; Cree, I.A.; Alexander, R.; Turowski, P.; Ockrim, Z.; Patel, J.; Boyd, S.R.; Joussen, A.M.; Ziemssen, F.; Hykin, P.G.; Moss, S.E. Angiopoietin modulation of vascular endothelial growth factor: Effects on retinal endothelial cell permeability. Cytokine 2007, 40, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, D.; Suzuma, K.; Suzuma, I.; Ohashi, H.; Ojima, T.; Kurimoto, M.; Murakami, T.; Kimura, T.; Takagi, H. Vitreous levels of angiopoietin 2 and vascular endothelial growth factor in patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol 2005, 139, 476–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klaassen, I.; Avery, P.; Schlingemann, R.O.; Steel, D.H.W. Vitreous protein networks around ANG2 and VEGF in proliferative diabetic retinopathy and the different effects of aflibercept versus bevacizumab pre-treatment. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 21062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammes, H.P.; Lin, J.; Wagner, P.; Feng, Y.; Vom Hagen, F.; Krzizok, T.; Renner, O.; Breier, G.; Brownlee, M.; Deutsch, U. Angiopoietin-2 causes pericyte dropout in the normal retina: Evidence for involvement in diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes 2004, 53, 1104–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Target | Host, Type and Conjugate | Sourcea) | Working concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| actin | mouse, monoclonal | clone 5J11, Novus Biologicals, #NBP2-25142 | 700 ng/ml |

| β-actin | mouse, monoclonal | clone BA3R, Invitrogen, #MA5-15739 | 100 ng/ml |

| claudin-1 | rabbit, polyclonal | Invitrogen, #51-9000 | 250 ng/ml |

| claudin-5 | rabbit, polyclonal | Invitrogen, #34-1600 | 100 ng/ml |

| PLVAPb) | rabbit, polyclonal | Invitrogen, #PA5-110183 | 2 µg/ml |

| VEcadherin | rabbit, polyclonal | Cell Signaling Technology B.V., #2158 | 1:2000 |

| whole rabbit IgG | goat, polyclonal, coupled to HRP |

Biorad, #170-5046 | 1:15000 |

| whole mouse IgG | goat, polyclonal, coupled to HRP |

Biorad, #170-5047 | 1:30000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).