Submitted:

12 March 2025

Posted:

14 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

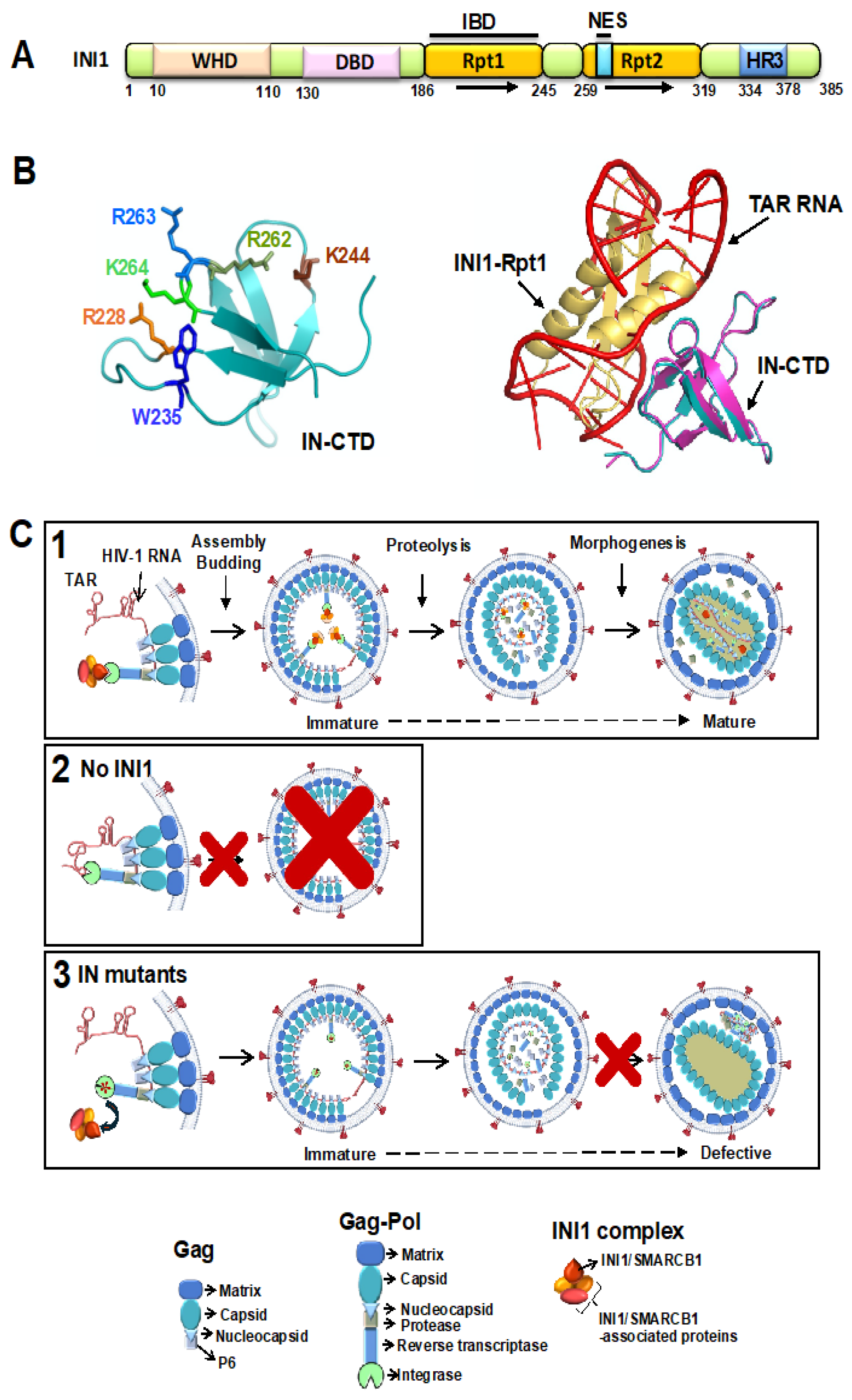

HIV-1 integrase (IN), an essential viral protein that catalyzes integration, also influences non-integration functions such as particle production and morphogenesis. The mechanism by which non-integration functions is mediated is not completely understood. Several factors influence this non-integration function including ability of IN to bind to viral RNA. INI1/SMARCB1 is an integrase binding host factor that influences HIV-1 replication at multiple stages, including particle production and particle morphogenesis. IN mutants defective for binding to INI1 are also defective for particle morphogenesis, similar to RNA-binding-defective IN mutants. Studies have indicated that the highly conserved Repeat (Rpt)1, the IN-binding domain of INI1, structurally mimics TAR RNA and that the Rpt1 and TAR RNA compete for binding to IN. Based on the RNA mimicry, we propose that INI1 may function as a “place-holder” for viral RNA to facilitate proper ribonucleoprotein complex formation required during the assembly and particle morphogenesis of the HIV-1 virus. These studies suggest that drugs that target IN/INI1 interaction may lead to dual inhibition of both IN/INI1 and IN/RNA interactions to curb HIV-1 replication.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Relevant Sections

Integrase as a Target for Inhibiting HIV-1 Late Events:

INI1/SMARCB1 Is an IN Binding Host Factor Essential for Viral Late Events

Structure of the Rpt1 Domain of INI1 and Structural Modeling of IN-CTD/INI1-Rpt1 Interactions

Structural Mimicry Between INI1-Rpt1 and TAR RNA

- (i)

- During these analyses, it was noted that some of the IN/INI1 interface residues (K264, R269), were also important for IN binding to HIV-1 genomic RNA [17,33] (Table 1). Substitution mutations of these interface IN residues (R228, W235, K264, R269), affected IN binding to both INI1 and TAR RNA and led to defective particle morphogenesis [17,33]. Our previous studies have indicated that IID IN mutants also led to defects in particle morphogenesis [32]. Based on these observations, it was surmised that IN residues involved in binding to INI1 and TAR RNA could overlap, and that this overlap in binding might explain the similarity in phenotypes of RNA-binding and INI1-binding-defective IN mutants in inducing particle morphogenesis defects. The following experiments were carried out to establish the similarity of INI1 and TAR RNA binding to IN as follows: TAR RNA and INI1183-304 bind to the same residues of IN: A panel of IN-CTD substitution mutations that span the interface residues of IN-CTD/INI1-Rpt1 complex were tested for their ability to interact with TAR RNA using a protein-RNA interaction Alpha assay. The profile of interactions of TAR RNA and INI1183-304 with IN-CTD mutants were identical, indicating that these molecules recognize the same residues on IN [33] (also see Table 1).

- (ii)

- TAR RNA and INI1183-304 compete for binding to IN-CTD: TAR RNA and INI1183-304 competed for binding to IN-CTD with similar IC50 values (IC50 ≈ 5 nM) in an Alpha assay [33]. Furthermore, the inhibition of IN-CTD/INI1-Rpt1 interaction by TAR was specific, as a scrambled RNA or a different fragment of HIV-1 genomic RNA (nts 237-279) did not inhibit CTD/INI1183-304 binding [33]. Together, these results indicated that INI1 Rpt1 and TAR require the same surface of IN-CTD for binding.

- (iii)

- Structural similarity between INI1 Rpt1 and HIV-1 TAR RNA: To understand this further, the complex between IN-CTD and TAR RNA was computationally modelled using MdockPP [33,59,60]. It was found that the same set of hydrophobic and positively charged IN-CTD residues are involved in interaction with both INI1-Rpt1 and TAR RNA, confirming the biochemical studies (Figure 1B left panel). When the complexes of IN-CTD/INI1-Rpt1 were superimposed onto the complex of IN-CTD/TAR, INI1-Rpt1 and TAR overlapped with each other in three-dimentional space (Figure 1B right panel) [33]. Close examination of the Rpt1 NMR structures indicated that it has a string of surface-exposed, negatively charged residues that are positioned in a specific manner. Examination of the position of phosphate groups on TAR which overlap with INI1-Rpt1 in the superimposed structure indicated that these phosphate groups are positioned in a manner resembling the arrangement of the negatively charged residues on the INI1-Rpt1 surface in three-dimensional space [33]. These analyses indicated that TAR RNA and INI-Rpt1 are overall similar in shape and electrostatic charge distribution on the surface, explaining how these two molecules could contact the same residues on the surface of IN-CTD, consistent with the similarity in binding of these two molecules to IN [33].

Model to Explain the Role of INI1 in HIV-1 Late Events Based on Its RNA Mimicry

Role of RNA and/or INI1 in Particle Morphogenesis

Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2D | two-dimensional |

| 3D | three-dimensional |

| aa | Amino acid |

| AIDS | Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome |

| ALLINI | Allosteric inhibitors of integrase |

| ART | Anti-retroviral therapy |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| BAF47 | Bramha Related Gene (BRG)1-associated factor 47 |

| CA | Capsid |

| cDNA | Complementary deoxyribonucleic acid |

| CTD | C-terminal domain |

| DBD | DNA binding domain |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| GST | Glutathione S-transferase |

| HADDOCK | High ambiguity driven protein-protein Docking |

| HDAC1 | Histone deacetylase 1 |

| HIV | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| HR3 | Homology region III |

| hSNF5 | Human Sucrose non-Fermenting |

| IBD | Integrase binding domain |

| IC50 | Half maximal inhibitory concentration |

| IID | INI1-interaction-defective |

| IN | Integrase |

| INI1 | Integrase interactor 1 |

| LEDGF | Lens epithelium–derived growth factor |

| LTR | Long terminal repeat |

| MA | Matrix |

| NC | Nucleocapsid |

| ND | Not determined |

| NES | Nuclear export signal |

| NMR | Nuclear magnetic resonance |

| nts | nucleotides |

| PDB | Protein Data Bank |

| PPI | Protein-protein interaction |

| PR | Protease |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

| RNP | Ribonucleoprotein |

| Rpt1 | Repeat 1 |

| Rpt2 | Repeat 2 |

| RT | Reverse transcriptase |

| SAP18 | Sin3A Associated Protein 18 |

| shRNA | Short hairpin ribonucleic acid |

| SIV | Simian immunodeficiency virus |

| SMARCB1 | SWI/SNF-related matrix-associated actin-dependent regulator of chromatin subfamily B member 1 |

| SWI/SNF | Switch/sucrose non-fermenting |

| TAR | Trans-activation response |

| Tat | Trans-activator of transcription |

| Vpr | viral protein R |

| WHD | Winged Helix DNA binding domain |

| WT | Wild-type |

References

- 1. World Health Organization, HIV and AIDS. 2023.

- Lichterfeld, M., C. Gao, and X.G. Yu, An ordeal that does not heal: understanding barriers to a cure for HIV-1 infection. Trends Immunol, 2022. 43(8): p. 608-616. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P., et al., A multiclade env-gag VLP mRNA vaccine elicits tier-2 HIV-1-neutralizing antibodies and reduces the risk of heterologous SHIV infection in macaques. Nat Med, 2021. 27(12): p. 2234-2245. [CrossRef]

- Back, D. and C. Marzolini, The challenge of HIV treatment in an era of polypharmacy. J Int AIDS Soc, 2020. 23(2): p. e25449. [CrossRef]

- Clavel, F. and A.J. Hance, HIV drug resistance. New England Journal of Medicine, 2004. 350(10): p. 1023-35. [CrossRef]

- Roux, H. and N. Chomont, Measuring Human Immunodeficiency Virus Reservoirs: Do We Need to Choose Between Quantity and Quality? J Infect Dis, 2024. 229(3): p. 635-643. [CrossRef]

- Henderson, L.J., et al., Advances toward Curing HIV-1 Infection in Tissue Reservoirs. J Virol, 2020. 94(3). [CrossRef]

- Pau, A.K. and J.M. George, Antiretroviral therapy: current drugs. Infect Dis Clin North Am, 2014. 28(3): p. 371-402. [CrossRef]

- Woollard, S.M. and G.D. Kanmogne, Maraviroc: a review of its use in HIV infection and beyond. Drug Des Devel Ther, 2015. 9: p. 5447-68. [CrossRef]

- Craigie, R., The molecular biology of HIV integrase. Future Virol, 2012. 7(7): p. 679-686. [CrossRef]

- Engelman, A., et al., Multiple effects of mutations in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase on viral replication. J Virol, 1995. 69(5): p. 2729-36. [CrossRef]

- Elliott, J.L., et al., Integrase-RNA interactions underscore the critical role of integrase in HIV-1 virion morphogenesis. Elife, 2020. 9. [CrossRef]

- Elliott, J.L. and S.B. Kutluay, Going beyond Integration: The Emerging Role of HIV-1 Integrase in Virion Morphogenesis. Viruses, 2020. 12(9). [CrossRef]

- Engelman, A.N. and M. Kvaratskhelia, Multimodal Functionalities of HIV-1 Integrase. Viruses, 2022. 14(5). [CrossRef]

- Kleinpeter, A. and E.O. Freed, How to package the RNA of HIV-1. Elife, 2020. 9. [CrossRef]

- Feng, L., et al., HIV-1 integrase multimerization as a therapeutic target. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol, 2015. 389: p. 93-119. [CrossRef]

- Kessl, J.J., et al., HIV-1 Integrase Binds the Viral RNA Genome and Is Essential during Virion Morphogenesis. Cell, 2016. 166(5): p. 1257-1268 e12. [CrossRef]

- Yung, E., et al., Inhibition of HIV-1 virion production by a transdominant mutant of integrase interactor 1. Nat Med, 2001. 7(8): p. 920-6. [CrossRef]

- Cherepanov, P., et al., HIV-1 integrase forms stable tetramers and associates with LEDGF/p75 protein in human cells. J Biol Chem, 2003. 278(1): p. 372-81. [CrossRef]

- Engelman, A. and P. Cherepanov, The lentiviral integrase binding protein LEDGF/p75 and HIV-1 replication. PLoS Pathog, 2008. 4(3): p. e1000046. [CrossRef]

- Turlure, F., et al., Human cell proteins and human immunodeficiency virus DNA integration. Front Biosci, 2004. 9: p. 3187-208. [CrossRef]

- Kalpana, G.V., et al., Binding and stimulation of HIV-1 integrase by a human homolog of yeast transcription factor SNF5. Science, 1994. 266(5193): p. 2002-6. [CrossRef]

- Batisse, C., et al., Integrase-LEDGF/p75 complex triggers the formation of biomolecular condensates that modulate HIV-1 integration efficiency in vitro. J Biol Chem, 2024. 300(6): p. 107374. [CrossRef]

- Bedwell, G.J., et al., rigrag: high-resolution mapping of genic targeting preferences during HIV-1 integration in vitro and in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res, 2021. 49(13): p. 7330-7346. [CrossRef]

- Lapaillerie, D., et al., Modulation of the intrinsic chromatin binding property of HIV-1 integrase by LEDGF/p75. Nucleic Acids Res, 2021. 49(19): p. 11241-11256. [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.K., G.J. Bedwell, and A.N. Engelman, Spatial and Genomic Correlates of HIV-1 Integration Site Targeting. Cells, 2022. 11(4). [CrossRef]

- Cano, J. and G.V. Kalpana, Inhibition of early stages of HIV-1 assembly by INI1/hSNF5 transdominant negative mutant S6. J Virol, 2011. 85(5): p. 2254-65. [CrossRef]

- La Porte, A., et al., An Essential Role of INI1/hSNF5 Chromatin Remodeling Protein in HIV-1 Posttranscriptional Events and Gag/Gag-Pol Stability. J Virol, 2016. 90(21): p. 9889-9904. [CrossRef]

- Sorin, M., et al., Recruitment of a SAP18-HDAC1 complex into HIV-1 virions and its requirement for viral replication. PLoS Pathog, 2009. 5(6): p. e1000463. [CrossRef]

- Sorin, M., et al., HIV-1 replication in cell lines harboring INI1/hSNF5 mutations. Retrovirology, 2006. 3: p. 56. [CrossRef]

- Yung, E., et al., Specificity of interaction of INI1/hSNF5 with retroviral integrases and its functional significance. J Virol, 2004. 78(5): p. 2222-31. [CrossRef]

- Mathew, S., et al., INI1/hSNF5-interaction defective HIV-1 IN mutants exhibit impaired particle morphology, reverse transcription and integration in vivo. Retrovirology, 2013. 10: p. 66. [CrossRef]

- Dixit, U., et al., INI1/SMARCB1 Rpt1 domain mimics TAR RNA in binding to integrase to facilitate HIV-1 replication. Nat Commun, 2021. 12(1): p. 2743. [CrossRef]

- Engelman, A., In Vivo Analysis of Retroviral Integrase Structure and Function, in Advances in Virus Research K. Rlaramorosch, F.A. Murphy, and A.J. Shawn, Editors. 1999, Academic Press. p. 411-26.

- Leavitt, A.D., et al., Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase mutants retain in vitro integrase activity yet fail to integrate viral DNA efficiently during infection. J Virol, 1996. 70(2): p. 721-8. [CrossRef]

- Sundquist, W.I. and H.G. Krausslich, HIV-1 assembly, budding, and maturation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med, 2012. 2(7): p. a006924. [CrossRef]

- Shehu-Xhilaga, M., S.M. Crowe, and J. Mak, Maintenance of the Gag/Gag-Pol ratio is important for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA dimerization and viral infectivity. J Virol, 2001. 75(4): p. 1834-41. [CrossRef]

- Jurado, K.A., et al., Allosteric integrase inhibitor potency is determined through the inhibition of HIV-1 particle maturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2013. 110(21): p. 8690-5. [CrossRef]

- Centore, R.C., et al., Mammalian SWI/SNF Chromatin Remodeling Complexes: Emerging Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies. Trends Genet, 2020. 36(12): p. 936-950. [CrossRef]

- Reddy, D., S. Bhattacharya, and J.L. Workman, (mis)-Targeting of SWI/SNF complex(es) in cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev, 2023. 42(2): p. 455-470. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. and J. Tang, SWI/SNF complexes and cancers. Gene, 2023. 870: p. 147420. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, G.W. and A.L. Hong, SMARCB1-Deficient Cancers: Novel Molecular Insights and Therapeutic Vulnerabilities. Cancers (Basel), 2022. 14(15). [CrossRef]

- Graf, M., et al., Single-cell transcriptomics identifies potential cells of origin of MYC rhabdoid tumors. Nat Commun, 2022. 13(1): p. 1544. [CrossRef]

- Sevenet, N., et al., Constitutional mutations of the hSNF5/INI1 gene predispose to a variety of cancers. Am J Hum Genet, 1999. 65(5): p. 1342-8. [CrossRef]

- Bushman, F., Targeting retroviral integration. Science, 1995. 267(5203): p. 1443-4. [CrossRef]

- Lesbats, P., et al., Functional coupling between HIV-1 integrase and the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex for efficient in vitro integration into stable nucleosomes. PLoS Pathog, 2011. 7(2): p. e1001280. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.W., et al., c-MYC interacts with INI1/hSNF5 and requires the SWI/SNF complex for transactivation function. Nat Genet, 1999. 22(1): p. 102-5. [CrossRef]

- Craig, E., et al., A masked NES in INI1/hSNF5 mediates hCRM1-dependent nuclear export: implications for tumorigenesis. EMBO J, 2002. 21(1-2): p. 31-42. [CrossRef]

- Das, B.C., M.E. Smith, and G.V. Kalpana, Design, synthesis of novel peptidomimetic derivatives of 4-HPR for rhabdoid tumors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett, 2008. 18(14): p. 4177-80. [CrossRef]

- Das, B.C., M.E. Smith, and G.V. Kalpana, Design and synthesis of 4-HPR derivatives for rhabdoid tumors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett, 2008. 18(13): p. 3805-8. [CrossRef]

- Das, S., J. Cano, and G.V. Kalpana, Multimerization and DNA binding properties of INI1/hSNF5 and its functional significance. J Biol Chem, 2009. 284(30): p. 19903-14. [CrossRef]

- Morozov, A., E. Yung, and G.V. Kalpana, Structure-function analysis of integrase interactor 1/hSNF5L1 reveals differential properties of two repeat motifs present in the highly conserved region. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1998. 95(3): p. 1120-5. [CrossRef]

- Pathak, R., et al., Inhibition of nuclear export restores nuclear localization and residual tumor suppressor function of truncated SMARCB1/INI1 protein in a molecular subset of atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumors. Acta Neuropathol, 2021. 142(2): p. 361-374. [CrossRef]

- Valencia, A.M., et al., Recurrent SMARCB1 Mutations Reveal a Nucleosome Acidic Patch Interaction Site That Potentiates mSWI/SNF Complex Chromatin Remodeling. Cell, 2019. 179(6): p. 1342-1356 e23. [CrossRef]

- Allen, M.D., et al., The SWI/SNF Subunit INI1 Contains an N-Terminal Winged Helix DNA Binding Domain that Is a Target for Mutations in Schwannomatosis. Structure, 2015. 23(7): p. 1344-9. [CrossRef]

- Morozov, A., et al., INI1 induces interferon signaling and spindle checkpoint in rhabdoid tumors. Clin Cancer Res, 2007. 13(16): p. 4721-30. [CrossRef]

- Kohashi, K. and Y. Oda, Oncogenic roles of SMARCB1/INI1 and its deficient tumors. Cancer Sci, 2017. 108(4): p. 547-552. [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.Y., et al., Epstein-Barr virus nuclear protein 2 (EBNA2) binds to a component of the human SNF-SWI complex, hSNF5/Ini1. J Virol, 1996. 70(9): p. 6020-8. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L., et al., Computational Modeling of IN-CTD/TAR Complex to Elucidate Additional Strategies to Inhibit HIV-1 Replication. Methods Mol Biol, 2023. 2610: p. 75-84. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X., et al., Performance of MDockPP in CAPRI rounds 28-29 and 31-35 including the prediction of water-mediated interactions. Proteins, 2017. 85(3): p. 424-434. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.Y., et al., Inclusion of the orientational entropic effect and low-resolution experimental information for protein-protein docking in Critical Assessment of PRedicted Interactions (CAPRI). Proteins, 2013. 81(12): p. 2183-91. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.Y. and X. Zou, A knowledge-based scoring function for protein-RNA interactions derived from a statistical mechanics-based iterative method. Nucleic Acids Res, 2014. 42(7): p. e55. [CrossRef]

- Lu, R., H.Z. Ghory, and A. Engelman, Genetic analyses of conserved residues in the carboxyl-terminal domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase. J Virol, 2005. 79(16): p. 10356-68. [CrossRef]

- Semenova, E.A., C. Marchand, and Y. Pommier, HIV-1 integrase inhibitors: update and perspectives. Adv Pharmacol, 2008. 56: p. 199-228. [CrossRef]

- Wiskerchen, M. and M.A. Muesing, Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase: effects of mutations on viral ability to integrate, direct viral gene expression from unintegrated viral DNA templates, and sustain viral propagation in primary cells. J Virol, 1995. 69(1): p. 376-86. [CrossRef]

- Ao, Z., et al., Interaction of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 integrase with cellular nuclear import receptor importin 7 and its impact on viral replication. J Biol Chem, 2007. 282(18): p. 13456-67. [CrossRef]

- Shema Mugisha, C., et al., Emergence of Compensatory Mutations Reveals the Importance of Electrostatic Interactions between HIV-1 Integrase and Genomic RNA. mBio, 2022. 13(5): p. e0043122. [CrossRef]

- Cannon, P.M., et al., Conserved sequences in the carboxyl terminus of integrase that are essential for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication. J Virol, 1996. 70(1): p. 651-7. [CrossRef]

- Charpentier, C. and D. Descamps, Resistance to HIV Integrase Inhibitors: About R263K and E157Q Mutations. Viruses, 2018. 10(1). [CrossRef]

- De Houwer, S., et al., The HIV-1 integrase mutant R263A/K264A is 2-fold defective for TRN-SR2 binding and viral nuclear import. J Biol Chem, 2014. 289(36): p. 25351-61. [CrossRef]

- Rozina, A., et al., Complex Relationships between HIV-1 Integrase and Its Cellular Partners. Int J Mol Sci, 2022. 23(20). [CrossRef]

- Cereseto, A., et al., Acetylation of HIV-1 integrase by p300 regulates viral integration. EMBO J, 2005. 24(17): p. 3070-81. [CrossRef]

- Madison, M.K., et al., Allosteric HIV-1 Integrase Inhibitors Lead to Premature Degradation of the Viral RNA Genome and Integrase in Target Cells. J Virol, 2017. 91(17). [CrossRef]

- Brockman, M.A., et al., Uncommon pathways of immune escape attenuate HIV-1 integrase replication capacity. J Virol, 2012. 86(12): p. 6913-23. [CrossRef]

- Nomaguchi, M., et al., Natural single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the 3’ region of the HIV-1 pol gene modulate viral replication ability. J Virol, 2014. 88(8): p. 4145-60. [CrossRef]

- Li, M. and R. Craigie, Processing of viral DNA ends channels the HIV-1 integration reaction to concerted integration. J Biol Chem, 2005. 280(32): p. 29334-9. [CrossRef]

- Ghasabi, F., et al., First report of computational protein-ligand docking to evaluate susceptibility to HIV integrase inhibitors in HIV-infected Iranian patients. Biochem Biophys Rep, 2022. 30: p. 101254. [CrossRef]

- Rogers, L., et al., Structural Implications of Genotypic Variations in HIV-1 Integrase From Diverse Subtypes. Front Microbiol, 2018. 9: p. 1754. [CrossRef]

- Katz, A., et al., Molecular evolution of protein-RNA mimicry as a mechanism for translational control. Nucleic Acids Res, 2014. 42(5): p. 3261-71. [CrossRef]

- Tsonis, P.A. and B. Dwivedi, Molecular mimicry: structural camouflage of proteins and nucleic acids. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2008. 1783(2): p. 177-87. [CrossRef]

- Walbott, H., et al., The H/ACA RNP assembly factor SHQ1 functions as an RNA mimic. Genes Dev, 2011. 25(22): p. 2398-408. [CrossRef]

- Kutluay, S.B., et al., Global changes in the RNA binding specificity of HIV-1 gag regulate virion genesis. Cell, 2014. 159(5): p. 1096-1109. [CrossRef]

- Angelov, D., et al., Differential remodeling of the HIV-1 nucleosome upon transcription activators and SWI/SNF complex binding. J Mol Biol, 2000. 302(2): p. 315-26. [CrossRef]

- Ariumi, Y., et al., The integrase interactor 1 (INI1) proteins facilitate Tat-mediated human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transcription. Retrovirology, 2006. 3: p. 47. [CrossRef]

- Rafati, H., et al., Repressive LTR nucleosome positioning by the BAF complex is required for HIV latency. PLoS Biol, 2011. 9(11): p. e1001206. [CrossRef]

- Rafati, H., et al., Correction: Repressive LTR Nucleosome Positioning by the BAF Complex Is Required for HIV Latency. PLoS Biol, 2015. 13(11): p. e1002302. [CrossRef]

- Treand, C., et al., Requirement for SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling complex in Tat-mediated activation of the HIV-1 promoter. EMBO J, 2006. 25(8): p. 1690-9. [CrossRef]

- Maillot, B., et al., Structural and functional role of INI1 and LEDGF in the HIV-1 preintegration complex. PLoS One, 2013. 8(4): p. e60734. [CrossRef]

- Maroun, M., et al., Inhibition of early steps of HIV-1 replication by SNF5/Ini1. J Biol Chem, 2006. 281(32): p. 22736-43. [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.M., et al., Stapled Peptides Inhibitors: A New Window for Target Drug Discovery. Comput Struct Biotechnol J, 2019. 17: p. 263-281. [CrossRef]

- Moiola, M., M.G. Memeo, and P. Quadrelli, Stapled Peptides-A Useful Improvement for Peptide-Based Drugs. Molecules, 2019. 24(20). [CrossRef]

| IN Residues | IN Mutations*, ** |

IN-INI1 Interaction | IN-RNA Interaction | Infection | Capsid Morphology | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charged | ||||||

| R228 | R228A | Defective | Defective | Defective | Defective | [12,33,63] |

| K244 | K244A | Defective | Defective | Defective | ND | [33,63] |

| K244E | ND | ND | Defective | ND | [64] | |

| K244A/E246A | ND | ND | Defective | ND | [65] | |

| K240A, K244A/R263A, K264A | ND | ND | Defective | ND | [66] | |

| R262 | R262A | ND | ND | Not Defective | ND | [63] |

| R262A/R263A | ND | Defective | Defective | Defective | [12,63,67] | |

| R262A/K264A | ND | ND | Defective | ND | [63] | |

| R262I/K264T | ND | ND | Defective | ND | [68] | |

| R262D/R263V/K264E | ND | ND | Defective | ND | [64] | |

| R263 | R263A | ND | ND | Less Defective | ND | [63] |

| R263K | ND | ND | Not Defective | ND | [69] | |

| R263L | ND | ND | Not Defective | ND | [64] | |

| R263S | ND | ND | Not Defective | ND | [68] | |

| R263A/K264A | ND | ND | Defective | ND | [70] | |

| K264 | K264A | ND | ND | Not Defective | ND | [63] |

| K264E | ND | ND | Defective | ND | [63] | |

| K264R | ND | ND | Not Defective | ND | [71] | |

| K264A/K266A | Defective | Defective | Defective | Defective | [17,33] | |

| K264R/K266R/K273R | ND | ND | Defective | ND | [72] | |

| R269 | R269A | ND | ND | Reduced and delayed | ND | [63,64] |

| R269A/D270A | ND | ND | Reduced | ND | [63,64] | |

| R269A/K273A | Defective | Defective | Defective | Defective | [17,33,73] | |

| Hydrophobic | ||||||

| I220 | I220L | ND | ND | Slightly Reduced | ND | [74] |

| F223 | F223A | ND | ND | Defective | ND | [75] |

| F223E | ND | ND | Defective | ND | [75] | |

| F223G | ND | ND | Defective | ND | [75] | |

| F223H | ND | ND | Less Defective | ND | [75] | |

| F223K | ND | ND | Defective | ND | [75] | |

| F223S | ND | ND | Defective | ND | [75] | |

| F223Y | ND | ND | Not Defective | ND | [75] | |

| W235 | W235A | Defective | Defective | Defective | ND | [33,34,76] |

| W235E | Defective | Defective | Defective | Defective | [33,34,76] | |

| W235K | Defective | Defective | Defective | ND | [33,34,76] | |

| W235F | Not Defective | Not Defective | Not Defective | ND | [33,34,76] | |

|

A265 |

A265T | ND | ND | Not Defective | ND | [77] |

| A265V | ND | ND | Not Defective | ND | [77,78] | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).