1. Introduction

Since the beginning of the 20th century, there has been a substantial increase in economic growth worldwide, thanks to advancements in science and technology. This has led to significant economic progress in many countries. However, this growth has also had negative impacts on the environment, including increased exploitation of natural resources, increase in greenhouse gas emissions, global warming, and other environmental issues. As a result, policymakers and researchers need to find solutions that support sustainable growth, balancing economic development with environmental preservation. Understanding the future of environmental quality over time is therefore crucial.

In this line, the Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP28) offered a crucial opportunity to address the climate crisis and accelerate measures to combat it. With global temperatures at record levels and extreme weather events disrupting lives worldwide, the conference assessed progress under the Paris Agreement and defined an action plan to reduce emissions and protect people's lives. Traditional fuels like coal, oil, and gas production must decrease rapidly, while renewable energy capacity must triple by 2030. Additionally, financing for adaptation and resilience to climate change must increase significantly.

Numerous studies have examined the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) hypothesis, which explores the relationship between environmental quality and economic growth. However, the results have been varied and sometimes conflicting due to differences in the samples studied. Some studies, including those conducted by Jalil & Mahmud (2009) for China, Fosten et al. (2012) for the United Kingdom, Godil et al. (2020) and Shehzad et al. (2021) for Pakistan, and Sahoo et al. (2021) for India, support the EKC hypothesis. On the other hand, studies by Pao & Tsai (2011) for Brazil, Al-Mulali et al. (2015) for Vietnam, Amri et al. (2019) for Tunisia, and Le (2021) for ASEAN-6 countries, reject this hypothesis.

The variation in outcomes is not only limited to the countries being studied, but also influenced by additional variables included in the model. Previous studies have shown that corruption, population, energy consumption, financial development, urbanization, and trade openness all contribute to this variation. Some studies have also included the variable of information and communication technology in the model to examine its relationship with carbon dioxide emissions. Information and Communication Technology encompasses various communication technologies such as the internet, telephones, mobile phones, computers, software, and media applications such as video conferencing and social networking. ICT is closely linked to societal development and is a crucial tool for transitioning from developing to advanced societies. Investing in ICT can help developing countries catch up with developed ones. It lures in foreign investment and stimulates economic activity. The development of ICT infrastructure has changed global economic relations and created development opportunities. Technologies like the Internet have connected individuals, businesses, and governments globally. A modern telecommunications infrastructure is crucial for the development of the country (Belloumi & Touati, 2022). Information and communication technologies have a wide-ranging impact on economic activities, including job creation, income growth, improved business operations, accessible information and communication networks, and enhanced education services. These effects contribute to sustainable social and economic development, but can also have negative environmental impacts (Belloumi &Touati, 2022). The recent rapid development of ICT has had concerning environmental impacts, including increased consumption of non-renewable energy, significant production of toxic waste, and contribution to carbon dioxide emissions.

Financial development is also considered a crucial factor in driving economic growth and environmental pollution. Financial development can impact a nation's carbon emissions and GDP. It can have both positive and negative effects on the environment. On the negative side, financial development can lead to increased carbon emissions due to factors such as attracting foreign investment, promoting consumer spending on high-emission products, and enabling companies to expand and increase energy consumption. On the positive side, companies with strong governance may be more likely to adopt low-carbon practices, and financial development can support technological innovation and energy efficiency. It is believed that information and communication technology can enhance the financial sector by stimulating investment activities, reducing the cost of bank loans, and increasing trading activities and oversight of resources. Additionally, the financial sector encourages businesses and industries to adopt modern, environmentally friendly technology. Investments in ICT can lower costs by improving communication systems and reducing transaction costs. As a result, ICT has the potential to improve access to credit and deposit services, optimize credit allocation, simplify financial transfers, and foster financial inclusion.

Further research is needed to fully understand the relationship between financial development, information and communication technology, and carbon emissions. This study specifically integrates both ICT and financial development into the EKC model for the case of Saudi Arabia to analyze their impact on environmental quality. Our contribution is threefold. Firstly, according to our knowledge, it is the first work to investigate the impact of ICT and financial development on carbon emissions in Saudi Arabia. Previous studies have only focused on the effects of economic growth, international trade, FDI, energy use, urbanization, or population density on CO2 emissions (e.g. Alkhathlan & Javid, 2013; Alshehry & Belloumi, 2015; Belloumi & Alshehry, 2016; Alshehry & Belloumi, 2017; Raggad, 2018; Kahia et al., 2021a; Kahia et al., 2021b). Furthermore, in a more recent study, Kahia et al. (2023) examined how environmental innovation and the deployment of green energy have contributed to reducing CO2 emissions in Saudi Arabia from 1990 to 2018. Additionally, Kahia et al. (2024) conducted a comparative analysis on the effects of green energy and environmental innovation on four environmental indicators in Saudi Arabia using annual data spanning from 1990 to 2018. Our research seeks to address this research gap in previous studies that does not investigated the simultaneous impact of ICT and financial development on environmental quality in Saudi Arabia. This sets our results apart as unique and innovative in the context of Saudi Arabia. Thus, the study will contribute to the existing literature on environmental sustainability in Saudi Arabia. Secondly, we test the reliability of the results by substituting CO2 emissions in the model with greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Thirdly, examining an emerging country like Saudi Arabia, which has committed to achieving net zero greenhouse gas emissions, presents an intriguing and unique case. Saudi Arabia has introduced its 2030 vision aimed at reducing the economy's reliance on oil through economic diversification. The Saudi Vision 2030 outlines key pillars for establishing a diversified and sustainable economy, including the promotion of a knowledge-based economy (Moreau and Aligishiev, 2024). Furthermore, our study analyzes recent annual data spanning from 1990 to 2022, taking into account GDP per capita, energy use per capita, urbanization, and trade openness as control variables.

This study aims to examine the impact of ICT and financial development on environmental quality in Saudi Arabia through the use of an ARDL cointegration modelling approach. It analyzes sample data from 1990 to 2022. The research uses the ARDL bound test to examine if there is a co-integrated relationship, utilizing the standard F-test. One benefit of the ARDL test is its robustness and effectiveness with small sample sizes, making it suitable for this study. Additionally, the ARDL model estimation allows for investigating the effects of independent variables on environmental quality in both the short and long term. The findings from this research could provide valuable insights for policymakers in steering the economic diversification of Saudi Arabia towards knowledge-based and environmentally sustainable practices.

This paper is organized as follows: the second section provides a brief literature review, the third section explains the empirical methodology, the fourth section highlights the results obtained and their discussion, the fifth section is dedicated to the robustness of results, and we conclude the paper by presenting the conclusions in the final section.

2. A Literature Review

Previous studies have shown that ICT can have both positive and negative effects. On the positive side, ICT contributes to industrialization and economic growth. However, it can also have negative effects on the environment, such as increased energy consumption. This can lead to poor environmental conditions and harm to humanity, which could present environmental challenges as it may affect carbon sinks, food security, and biodiversity (Mahmood et al., 2024a and 2024b). Similarly, financial development is important for economic growth but can also contribute to environmental degradation. However, it also encourages businesses to adopt modern, environmentally friendly technology (Andrianaivo & Kpodar, 2012). The impact of ICT and financial development on environmental pollution is a subject of ongoing debate among academics (Zhang & Liu, 2015). The findings of previous empirical studies differ. Some studies have found that ICT and financial have positive effect on environmental quality, while others have found a negative impact. These differences in findings are influenced by various factors including the specific country or group of countries studied, the methodologies employed, the time period analyzed, the indicators used to measure environmental quality, and the independent variables included in the models. We first discuss the studies that found a positive impact, followed by those that reported a negative effect.

For the first type of studies, there is evidence to suggest that the internet can have a positive effect on reducing carbon dioxide emissions. For instance, teleconferencing has been shown to cut travel-related greenhouse gas emissions by 50% (Coroama et al., 2012). Moyer & Hughes (2012) studied the impact of ICT on global systems and carbon emissions. Their study concluded that over 50 years, ICT can lead to a decrease in overall carbon emissions. Additionally, Al-Mulali et al., (2015) found that online retailing can reduce carbon dioxide emissions in developed countries, although the effect is not significant in developing countries. Higon et al. (2017) reported a non-linear relationship between ICT and emissions in both developed and developing countries, showing an inverted U-shaped relationship. Furthermore, a study in sub-Saharan Africa showed that internet use can help protect the environment (Asongu et al., 2017). In the same line, Ozcan & Apergis (2017) found that internet access reduces air pollution in a group of emerging countries. Khan et al. (2018) demonstrated that ICT and financial development moderate emissions, and the interaction between ICT and GDP contributes positively to emission mitigation. Asongu (2018) studied the interaction between ICT and globalization in influencing CO2 emissions in 44 Sub-Saharan African countries from 2000 to 2012 using the generalized method of moments. ICT was measured using internet and mobile phone penetration, while globalization was measured in terms of trade and financial openness. The results indicated that ICT can mitigate the adverse impact of globalization on environmental degradation, such as CO2 emissions. This suggests that ICT can help reduce the negative effects of globalization activities that contribute to CO2 emissions. Batool et al. (2019) investigated the relationship between information and communication technology, economic output, energy use, and CO2 emissions in South Korea from 1973 to 2016. They found that ICT has a positive impact on reducing environmental degradation in the medium and long term. In their study, Godil et al. (2020) examined how financial development, ICT, and institutional quality affect CO2 emissions in Pakistan. They used the quantile autoregressive distributed lag model to analyze data from 1995Q1 to 2018Q4. The results showed that both financial development and ICT consistently reduce CO2 emissions over the long term, indicating that an increase in these factors could lead to a decrease in carbon emissions regardless of the emission level.

Recently, Danish et al. (2021) examined the influence of information and communication technology, economic output, and financial development on carbon emissions in a specific group of emerging countries from 1990 to 2015. They used panel mean group and augmented mean group estimation methods and found that ICTs have a notable effect on reducing carbon emissions. Additionally, the combination of financial development and information and communication technology has a moderating effect on the level of CO2 emissions. The study suggests that policy interventions, such as increasing research and development in the ICT sector, are necessary to reduce CO2 emissions. Furthermore, implementing green ICT projects in the financial sector is a viable option to enhance energy efficiency. Shehzad et al. (2021) used the non-linear autoregressive distributed lag model to determine the non-linear impact of ICT on CO2 emissions in Pakistan. The analysis revealed that negative shocks in ICT usage could increase the level of CO2 emissions, while positive shocks decrease it. The study also found that domestic production of ICT devices has a more positive impact on environmental quality compared to importing from other countries. The researchers recommended that the government of Pakistan should encourage the public to use smart electrical devices and create opportunities for international ICT companies to establish production facilities in the country. According to a recent study, Habiba & Xinbang (2022) examined the impact of financial development on CO2 emissions. They utilized a two-stage system using the generalized method of moments and panel data from developed and emerging economies during the period spanning from 2000 to 2018. The results revealed that financial market development, as well as its sub-indices, have a reducing effect on CO2 emissions in both developed and emerging countries. Furthermore, the study demonstrated that financial institution development, as well as its sub-indices, enhance environmental quality in developed economies but impede it in emerging economies.

More recently, Tao et al. (2023) used an expanded Stochastic Impacts by Regression on Population, Affluence, and Technology (STIRPAT) model to investigate the effect of financial development on carbon emission intensity in OECD countries. They examined this relationship from both linear and non-linear perspectives and found that financial development plays a crucial role in reducing carbon emission intensity. The study also included a model that assessed the impact of financial development through information and communication technology on carbon emission intensity. The results showed a positive correlation between internet-based information and communication technology, service-based information and communication technology, and carbon emission intensity. In the same line, Fakher et al. (2024) studied the impact of financial development on the environmental quality in BRICS economies from 2005 to 2019. Their results suggested that financial development can improve environmental quality, while nonrenewable energy consumption worsen it. Additionally, there is a U-shaped relationship between environmental quality and economic growth for BRICS countries. Charfeddine et al. (2024) assessed the impact of digitalization, information and communication technology, renewable energy, and financial development on environmental quality in the top ten most polluted countries from 1995 to 2018 using the panel vector auto-regression model. They found that a digitalization-based index had a positive effect on environmental quality, along with renewable energy and economic complexity. However, financial development has a negative impact on the environment, even some improvements were observed in subsequent years.

There are numerous studies that have found a detrimental impact of ICT and financial factors on environmental quality in the second type of studies. In particular, Salahuddin & Alam (2015) found that a 1% increase in ICT usage results in a 0.16% increase in CO2 emissions. Later, Fakher et al. (2018) studied the simultaneous impact of trade and financial openness on ecological footprint in a selected sample of developing countries using panel data from 1994 to 2014. Their results indicated that trade and financial openness are influenced by various factors and cannot be considered as exogenous variables. By treating them as endogenous variables and considering their influencing factors, the study found that both trade and financial openness have positive and significant effect on ecological footprint (negative effect on environmental quality).

Tsaurai & Chimbo (2019) studied the influence of information and communication technology on CO2 emissions in a group of emerging economies. They revealed that financial development and economic output serve as channels through which information and communication technology could increase CO2 emissions. For BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) countries, Haseeb et al. (2019) showed that information and communication technology increases pollution emissions. Chen et al. (2019) examined how ICT affects CO2 emission intensity. They used internet and mobile phone usage to measure ICT penetration and applied quantile regression to analyze China's provincial panel data from 2001 to 2016 at five different quantiles (0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, and 0.9) to estimate the benchmark model. The results showed that ICT had a significant negative impact on CO2 emission intensity across all quantiles.

Jiang & Ma (2019) examined the relationship between financial development and carbon emissions using a system-generalized method of moments for two sub-groups: developed countries and emerging markets and developing countries. The findings indicated that financial development could significantly increase carbon emissions across all countries in the sample. This conclusion was consistent with the analysis of the emerging market and developing countries sub-group. However, the study also found that the impact of financial development on carbon emissions was not significant for the developed countries group. Shabani & Shahnazi (2019) examined the influence of energy consumption, GDP, and ICT on CO2 emissions in Iranian economic sectors from 2002 to 2013. The study confirmed that information and communication technology has a positive effect on pollution in the industrial sector, but a negative effect on pollution in the transportation and services sectors. Avom et al. (2020) concluded that the proliferation of mobile phones and the internet strongly stimulated carbon emissions in sub-Saharan African countries from 1996-2014. In their study, Raheem et al. (2020) examined the impact of ICT and financial development on carbon emissions in the G7 countries from 1990 to 2014 using the Pooled Mean Group estimator. They showed that information and communication technology has a lasting positive influence on carbon emissions, while financial development has a limited impact. The combined impact of information and communication technology and financial development yields negative coefficients. Shoaib et al. (2020) examined the connections between financial development and CO2 emissions in the eight highly industrialized countries and the eight developing countries of Bangladesh, Egypt, Indonesia, Iran, Malaysia, Nigeria, Pakistan, and Turkey from 1999 to 2013 using the Pooled Mean Group estimator. They found that financial development has a substantial and positive effect on carbon emissions in the long term. Recently, Magazzino et al. (2021) conducted a study to investigate the relationship between the penetration of information and communication technology and its impact on electricity consumption, economic activity, and pollution in 16 European Union countries from 1990 to 2017. They found that using ICT leads to increased electricity consumption, resulting in increased carbon dioxide emissions and improved GDP. In the same line, Charfeddine and Kahia (2021) studied the impact of ICT and renewable energy consumption on environmental quality in the MENA region from 1980 to 2019 by employing the STIRPAT model. They found that ICT usage led to increased CO2 emissions, while renewable energy consumption improved environmental quality. Additionally, causality tests showed bidirectional relationships between CO2 emissions and ICT and renewable energy consumption.

In their study, Wang & Xu (2021) explored a non-linear relationship between internet use and CO2 emissions in high, middle, and low-income countries from 1995 to 2018. They found that internet usage and human capital are key factors in developing a low-carbon economy. Human capital can offset the impact of internet usage on CO2 emissions. Internet usage can increase CO2 emissions when human capital is low, but it can reduce emissions when human capital is high. Similarly, Omri et al. (2021) studied the relationship between financial sector development, carbon emissions, and governance in Saudi Arabia from 1996 to 2016 using the dynamic ordinary least squares method. They found that financial development and governance quality both have significant impacts on carbon emissions. Good governance can mitigate the negative effects of financial development on the environment. Their results show that when financial development is coupled with good governance, it can lead to a reduction in carbon emissions. In the same line, Fakher & Murshed (2023) utilized the Panel Smooth Transition Regression method to analyze the Environmental Kuznets Curve and financial development Kuznets Curve hypotheses in 13 OPEC member countries. Their results indicated that financial development positively influenced the Composite Environmental Quality Index in the first regime but negatively affects it in the second regime. Additionally, economic growth positively impacts Composite Environmental Quality Index in the initial regime but has a negative effect in the second regime. Not later, Fakher & Ahmed (2023) studied the impact of financial development on the relationship between technological innovation and environmental quality in 25 OECD economies from 2000 to 2019. Their analysis revealed that financial development and energy consumption accelerate environmental degradation. However, financial development enhances the positive effects of technological innovation on ecological footprint, adjusted net savings, pressure on nature, and environmental performance. Yang et al. (2023) analyzed the impact of financial development on carbon emissions using panel data from 283 Chinese cities between 2006 and 2019. The findings revealed that financial development has a significant influence on increasing carbon emissions. Additionally, the upgrading of industrial structures also has a noticeable positive impact on carbon emissions, albeit with a moderate effect. In their research, Yu et al. (2023) investigated the relationship between financial development, foreign direct investment, and CO2 emissions in 57 countries, both developed and developing, from 2000 to 2017. The results of their study showed that the depth of financial institutions harmed CO2 intensity in developed countries and had a positive effect in developing countries. On the other hand, access to financial institutions hurt CO2 intensity in both types of economies. Furthermore, the stability of financial markets harmed CO2 intensity in developing economies and had a positive effect on developed economies. More recently, Nathaniel et al. (2024) studied the impact of clean energy, financial development, and globalization on the ecological footprint in Bangladesh using dynamic ARDL simulation techniques and bootstrap causality tests. Their results showed that financial development and globalization reduced the ecological footprint by 0.08% and 0.25%, respectively, supporting the Environmental Kuznets Curve hypothesis.

The literature review offers a comprehensive overview of the ongoing discussions regarding the impact of ICT and financial development on environmental quality. However, it is evident that empirical studies on this topic yield inconclusive and controversial results. Variations in findings are attributed to factors such as country-specific contexts, regional differences, time periods, data sources, econometric methodologies, and control variables. This study contributes uniquely to the existing literature in several ways. Firstly, it examines the combined effects of ICT and financial development on environmental quality in Saudi Arabia, a novel approach not previously explored. Secondly, the study rigorously tests the robustness of its findings by using both CO2 and GHG emissions as environmental quality indicators. Thirdly, the focus on a major oil-producing country like Saudi Arabia, committed to achieving net zero greenhouse gas emissions, presents a compelling case study. Additionally, the analysis covers recent annual data from 1990 to 2022, incorporating key variables such as GDP per capita, energy use per capita, urbanization, and trade openness. The insights generated from this research could inform policymakers in guiding Saudi Arabia's economic diversification towards knowledge-based and environmentally sustainable practices.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data

We investigate nine variables: Carbon dioxide emissions (metric tons per capita), total greenhouse gas emissions (metric tons per capita), primary energy consumption (Gigajoule per capita), domestic credit to the private sector (% of GDP), mobile cellular subscriptions (per 100 people), individuals using the internet (% of population), GDP per capita (constant 2015 US

$), trade (% of GDP), and urban population (% of total population). The study covers annual data from 1990 to 2022. Carbon dioxide emissions (CO2) and total greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) are used as indicators of environmental quality. Domestic credit to the private sector represents financial development (FD). There are three ways to measure information and communication technology: ICT readiness, ICT use, and ICT impact. Due to data limitations, we use proxies for ICT readiness and use. Specifically, we use mobile cellular subscriptions (MCS) per 100 people as a proxy for ICT readiness, and individuals using the internet (IUI) per 100 people as a proxy for ICT use. Primary energy consumption (EC), GDP per capita (GDP), trade openness (TO), and urban population (UR) are the main factors affecting the environment. Data on CO2, GHG, FD, MCS, IUI, GDP, TO, and UR are sourced from the World Development Indicators of the World Bank (WDI, 2024). EC data is obtained from the Energy Institute Statistical Review of World Energy (2023) (Source:

https://www.energyinst.org/statistical-review).

Table 1 outlines the definition and source of data for the various variables utilized. We convert all variables to logarithmic form and represent them as LCO2, LGHG, LFD, LMCS, LIUI, LGDP, LEC, LTO, and LUR, respectively.

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics for the different series. It shows that all series are normally distributed at a 5% significance level.

3.2. Methods

We utilize the linear ARDL model to examine the impact of financial development and ICT on environmental quality in Saudi Arabia. The ARDL model, developed by Pesaran et al. (2001), offers advantages over other co-integration methods such as Engle & Granger (1987) and Johansen (1988). It is particularly useful when dealing with limited data and can handle a combination of I(0) and I(1) variables. However, it does not apply to second-order integrated series. Moreover, despite its benefits, conducting a long-run relationship test using the ARDL framework can be challenging. The test statistic's distribution is nonstandard and relies on different aspects of the model and data, such as the variables' integration order. Pesaran et al. (2001) introduced a "bounds test" method that compares conventional F and t statistics with critical values (CV) to determine if the null hypothesis can be rejected. If the test falls outside the bounds, the null hypothesis is either rejected or not rejected conclusively. When within the bounds, the test results are inconclusive (Kripfganz and Schneider, 2023).

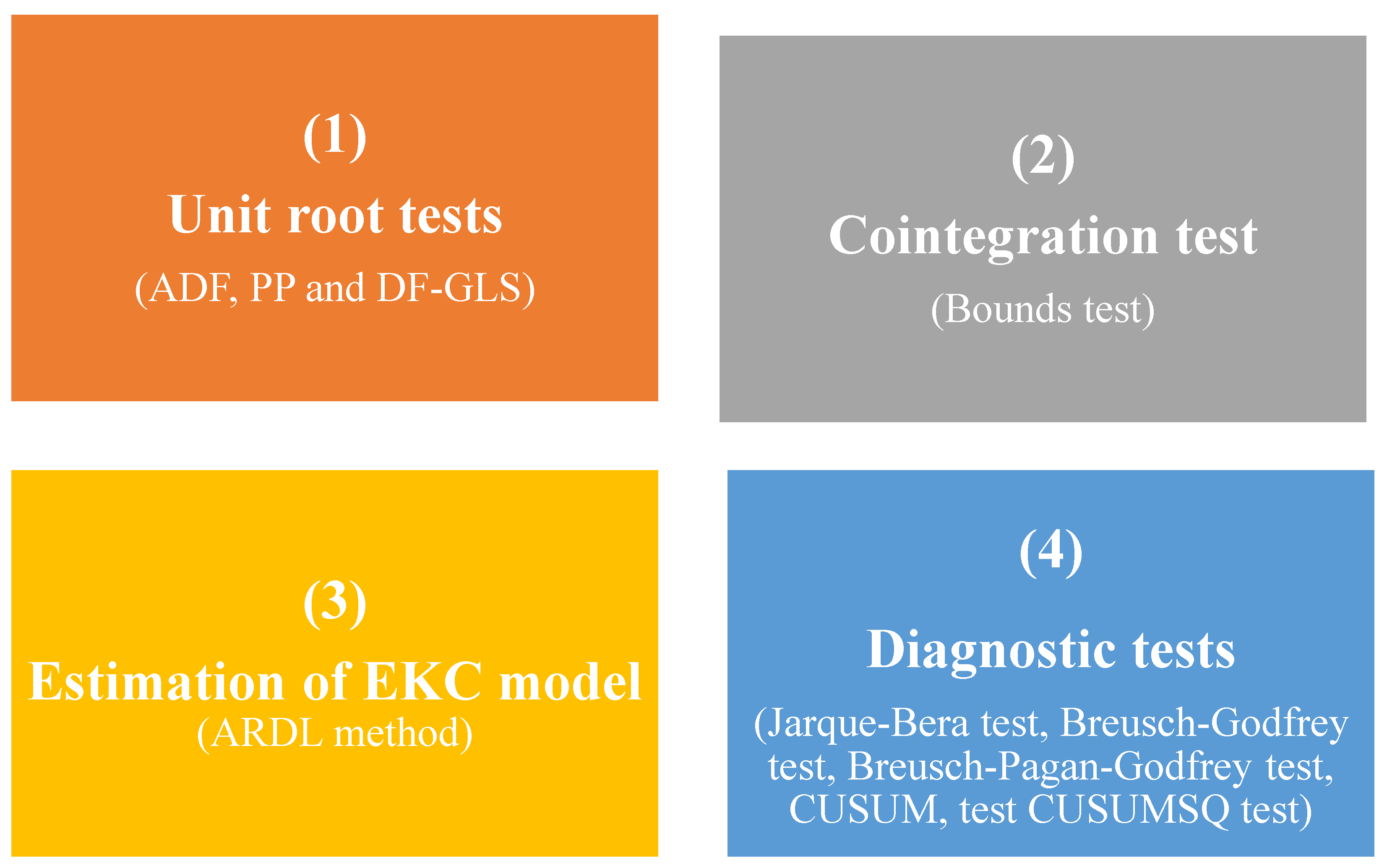

The ARDL techniques implementation involves multiple steps. Initially, unit root tests are conducted to assess the stationarity of the different series. In time series analysis, identifying the nonstationarity of economic variables is crucial due to their trending behavior. This distinction helps prevent spurious regressions and determine cointegration relationships among the variables under study. Before testing for cointegration and model estimation, it is essential to evaluate the stationarity of the economic variables used in this study. Common procedures such as the augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) (developed by Dickey & Fuller, 1979), Phillips-Perron (PP) (developed by Phillips & Perron, 1988), and DF-GLS test (developed by Elliot et al.

, 1996) tests are employed for this purpose. The PP test stands out for correcting heteroskedasticity and serial correlation in the error term. The DF-GLS test is tailored for series with deterministic components like a constant or linear trend. The null hypothesis for all three tests is that the time series is nonstationary, with the alternative hypothesis being stationarity. Subsequently, the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) is used to determine the optimal lag lengths of the model. The Fisher bounds test is then conducted to examine cointegration relationships among the variables. Following this, the short and long-run effects of financial development and ICT on environmental quality in Saudi Arabia are estimated. Finally, various diagnostic tests are performed, including the Jarque-Bera test for error term normality, Breusch-Godfrey Serial Correlation LM test for error term correlation, Breusch-Pagan-Godfrey LM test for error term homoscedasticity, and CUSUM and CUSUMSQ tests for model stability assessment. These tests help validate the estimated model. The various stages of the econometric modeling strategy are outlined in

Figure 1.

In our study, we examine the impact of financial development and ICT on environmental quality in Saudi Arabia in the context of the EKC hypothesis. The EKC hypothesis is based on the idea that economic growth can lead to environmental deterioration, with a negative impact on environmental quality. The relationship between economic growth and environmental degradation goes through three phases influenced by scale, composition, and technical effects (Grossman and Krueger 1991). Initially, as the economy grows, it exerts a scale effect on the environment by increasing the demand for natural resources and generating industrial waste. This leads to a decline in environmental quality as policymakers prioritize economic growth over environmental concerns. As the economy develops, the composition of the economy changes, with a shift towards cleaner technologies and increased energy efficiency. This composition effect has a positive impact on the environment. In the final stage, economic growth leads to a technical effect on environmental quality as the economy transitions to a knowledge-intensive service sector. Investments in research and development result in the adoption of environmentally friendly technologies, leading to simultaneous growth in both economic and environmental quality. The relationship between economic growth and environmental quality is often depicted as a bell-shaped curve or inverted U-shape, known as the EKC hypothesis (AlKhars et al., 2022).

While studies on the EKC hypothesis may utilize various methodologies, most of them tend to follow similar model specifications. Typically, the model used generally follows the format shown in Equation (1):

where EQ represents the environmental quality, GDP represents the economic growth, and X represents a vector of other explanatory variables. GDP2 represents the square of GDP, while GDP3 represents the cubic of GDP. The relationship between economic growth and environmental indicators in this model can take on various shapes, including N-shaped, inverted N-shaped, no relationship, inverted U-shaped, U-shaped, positive monotonic, and negative monotonic (AlKhars et al., 2022).

To address the issues of omitted variable bias and collinearity, this study follows the previous studies on Saudi Arabia (Alkhathlan & Javid, 2013; Alshehry & Belloumi, 2017; Raggad, 2018; Alfantookh et al., 2023) and utilizes a standard log-linear functional relationship between environmental quality indicator, real GDP per capita, the square of real GDP per capita, total energy consumption per capita, financial development, ICT, trade openness, and urbanization. The logarithmic model used is as follows:

where L is the natural logarithm operator, EQ represents environmental quality, such as CO2 or GHG emissions, and ICT represents either MCS or IUI.

Then, the linear logarithmic ARDL model can be derived from Equation (2), and it is expressed as follows:

where Y = (LEC, LGDP, LGDP2, LFD, LICT, LTO, LUR) represents the vector of independent variables. The coefficients β, η, and αj correspond to the error correction term (ECT), the long-run parameters, and the short-run parameters, respectively.

The estimated ECT coefficient measures how quickly the environmental quality returns to equilibrium when the explanatory variables varied. It has a negative sign for cointegrated series. After checking the stationarity of the series, we estimate the model with up to four lags. The AIC criterion is used to determine the optimal lag length. Next, we test for cointegration between the variables by employing the F-test statistics of Pesaran et al. (2001) with the null hypothesis: H0: η = 0. If the value of the F statistic exceeds the critical upper bound value, we reject the null hypothesis, indicating that the variables are cointegrated.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Results of Unit Root Tests

During the initial analysis stage, we perform non-stationary tests, including the augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test, the Phillips-Perron (PP) test, and the DF-GLS test. These tests help us determine the order of integration of the various variables. The results of these unit root tests are presented in

Table 3, which shows that all series are integrated of order one (I(1)).

4.2. Results and Their Discussion

We estimate the ARDL model using CO2 emissions as a proxy for environmental quality, as all the series are stationary at their first differences. We estimate three versions of the model (model 1, model 2, and model 3). In model 1, we test for the existence of the Environmental Kuznets Curve by including the square of GDP as an independent variable. In models 2 and 3, we do not consider the EKC hypothesis. The lag length is selected using the AIC, with a maximum length of 4 for all three models.

The results of the Bounds test are shown in

Table 4, while the short and long-run results are displayed in

Table 5. The F-statistic value of the Bounds test exceeds the upper bound at a 1% significance level in all three models, indicating the presence of long-term effects of the independent variables on environmental quality in KSA. Additionally, the ECT has a coefficient that is both negative and significant at a 1% level in all three models, supporting the previous results of the Bounds test and indicating a long-term relationship between CO2 and the independent variables.

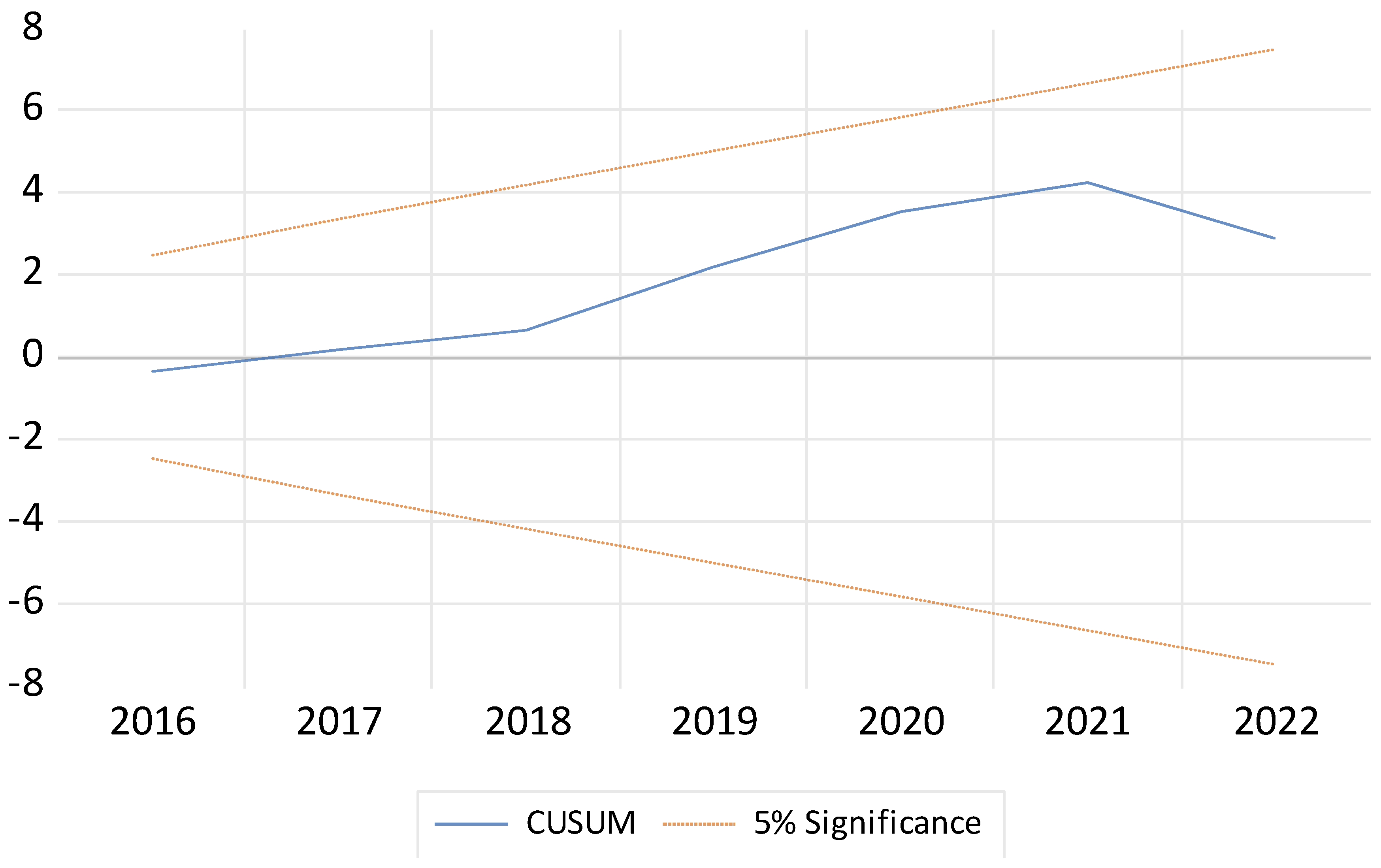

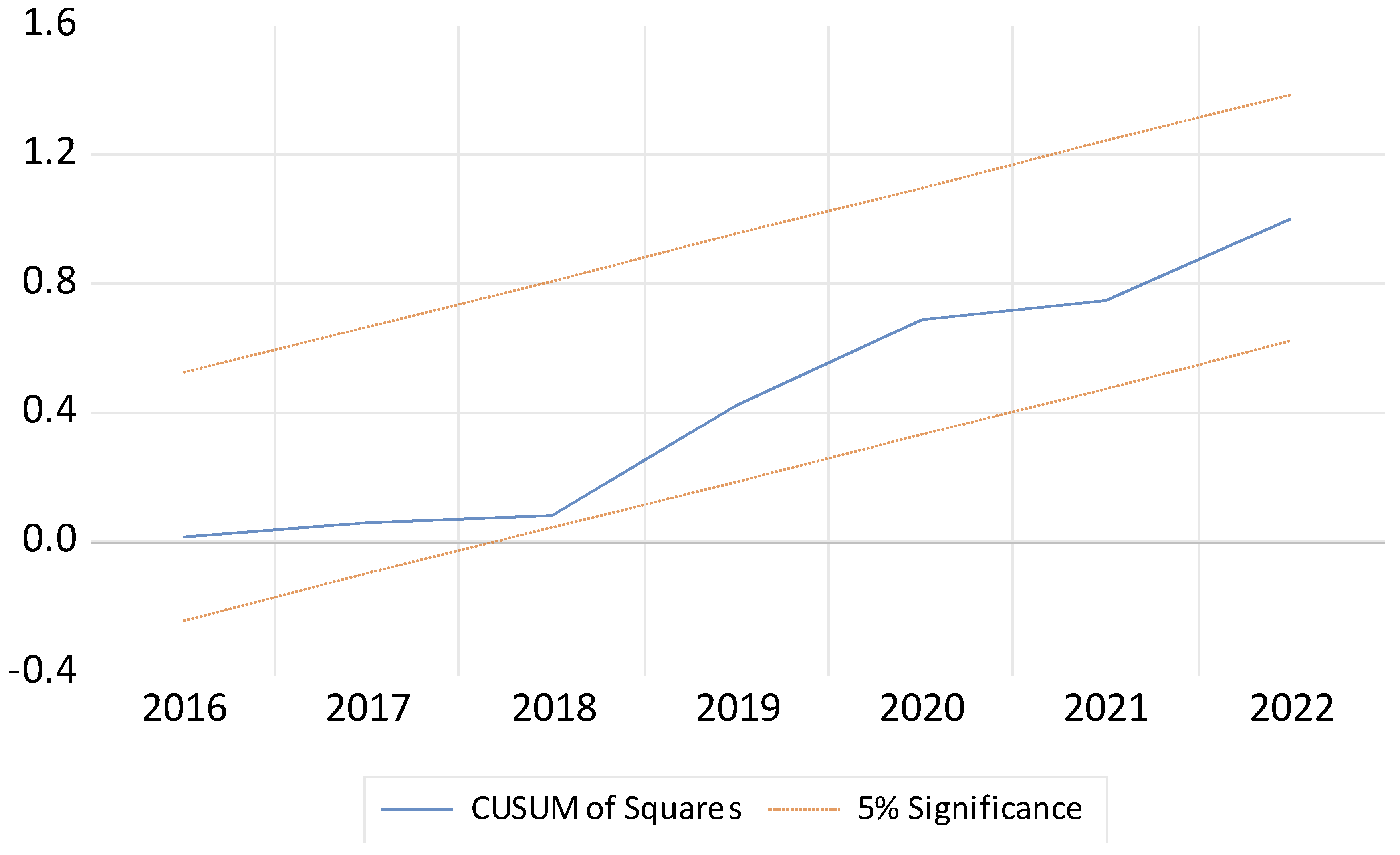

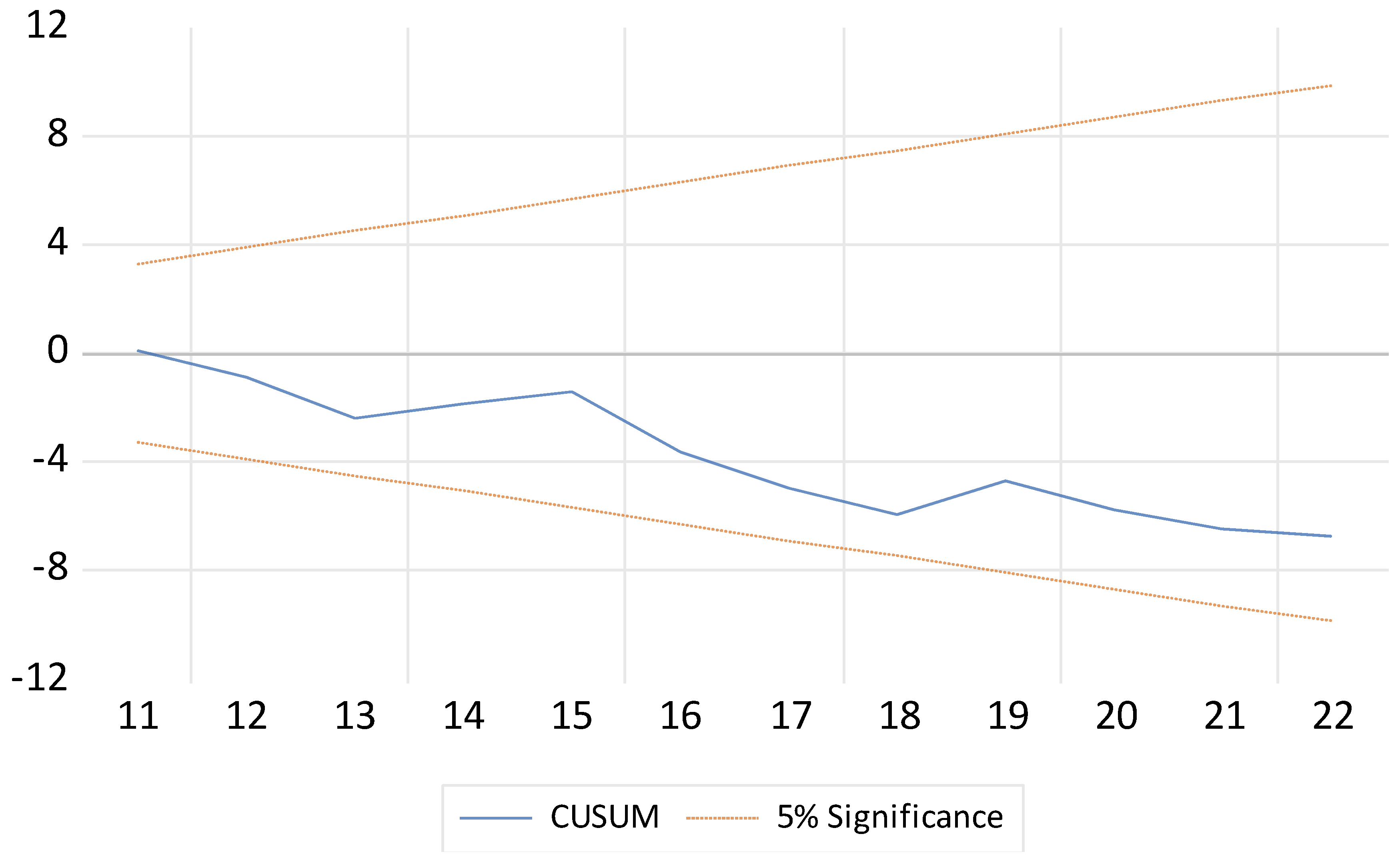

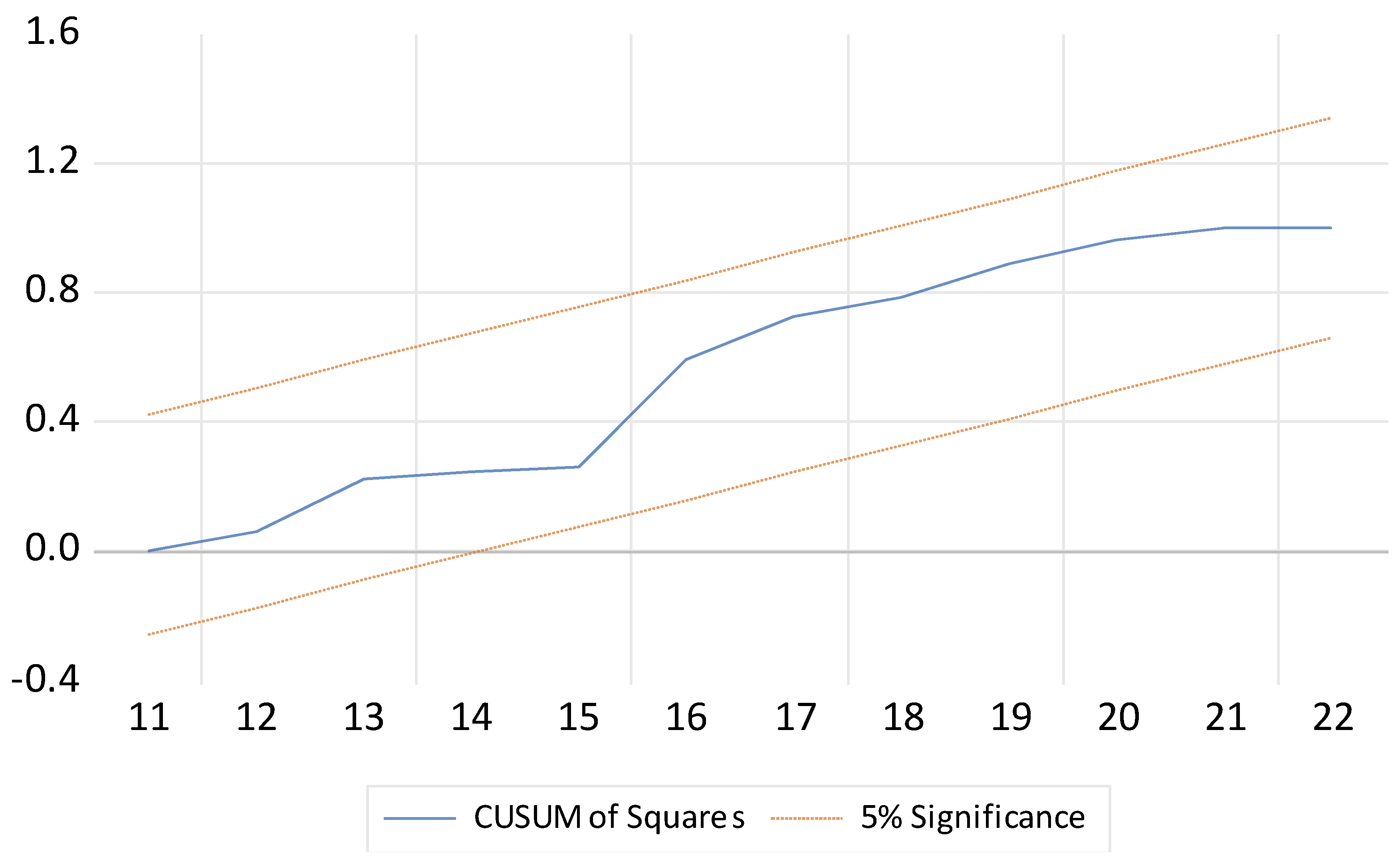

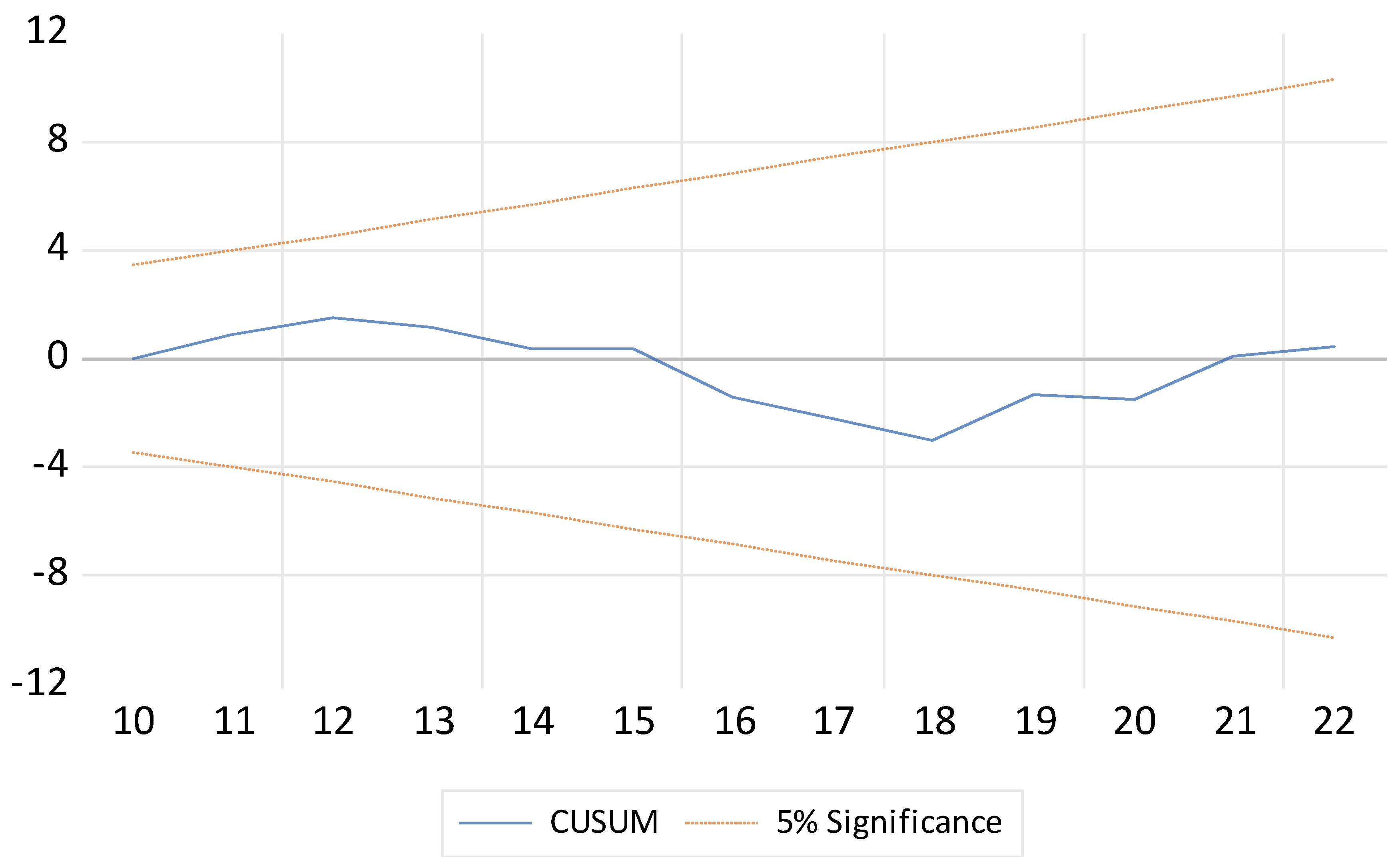

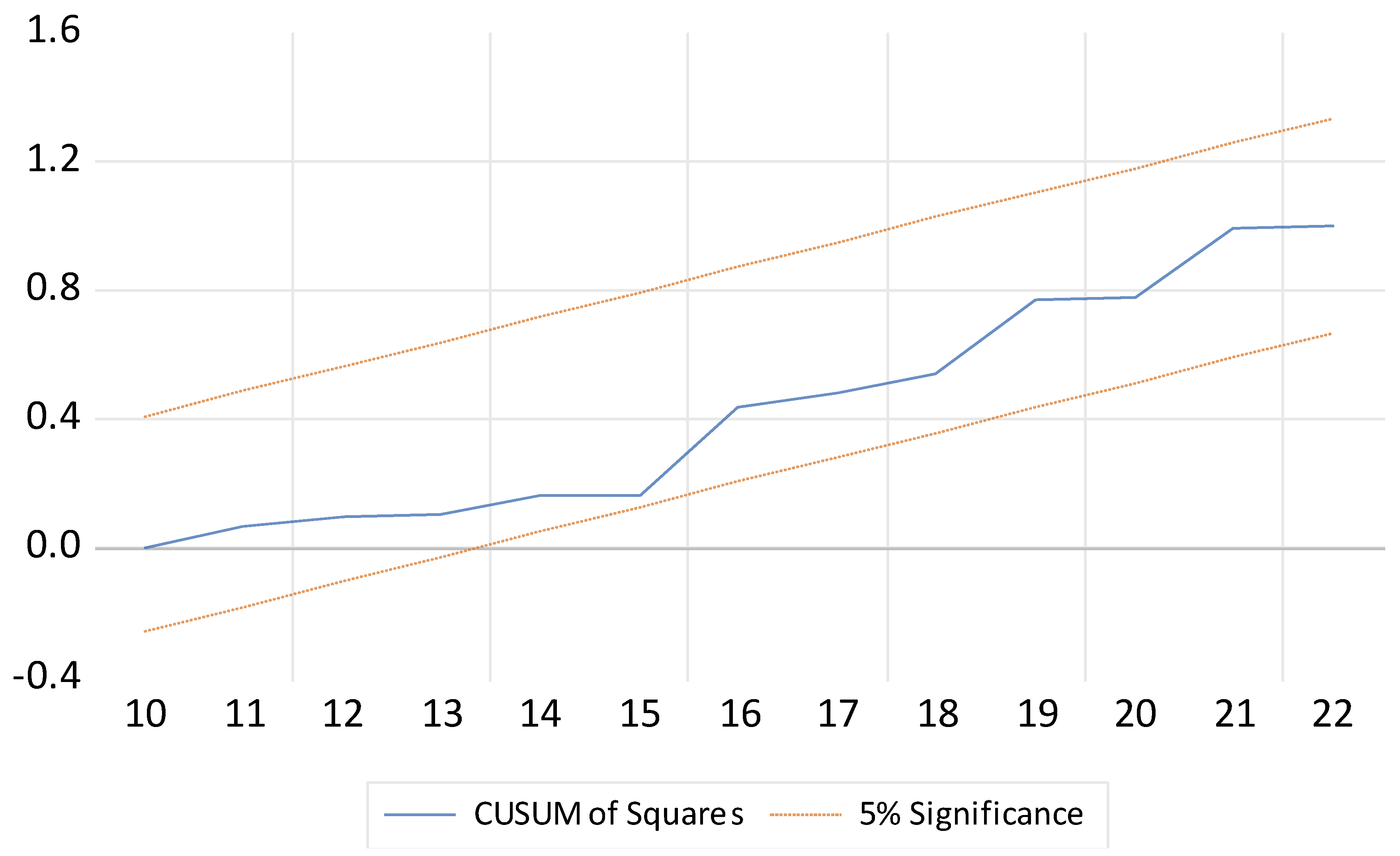

The various employed diagnostic tests confirm that the error terms in the three ARDL models are normally distributed, have equal variances, and are not correlated. To assess the stability of the coefficients, we use the CUSUM and CUSUMSQ tests. These tests detect systematic and sudden changes in the coefficients. The results of the CUSUM and CUSUMSQ tests, shown in

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

Figure 8, indicate that the blue line falls within the critical bands at a 5% significance level. Therefore, we can conclude that the three ARDL models estimated are stable and our findings are reliable.

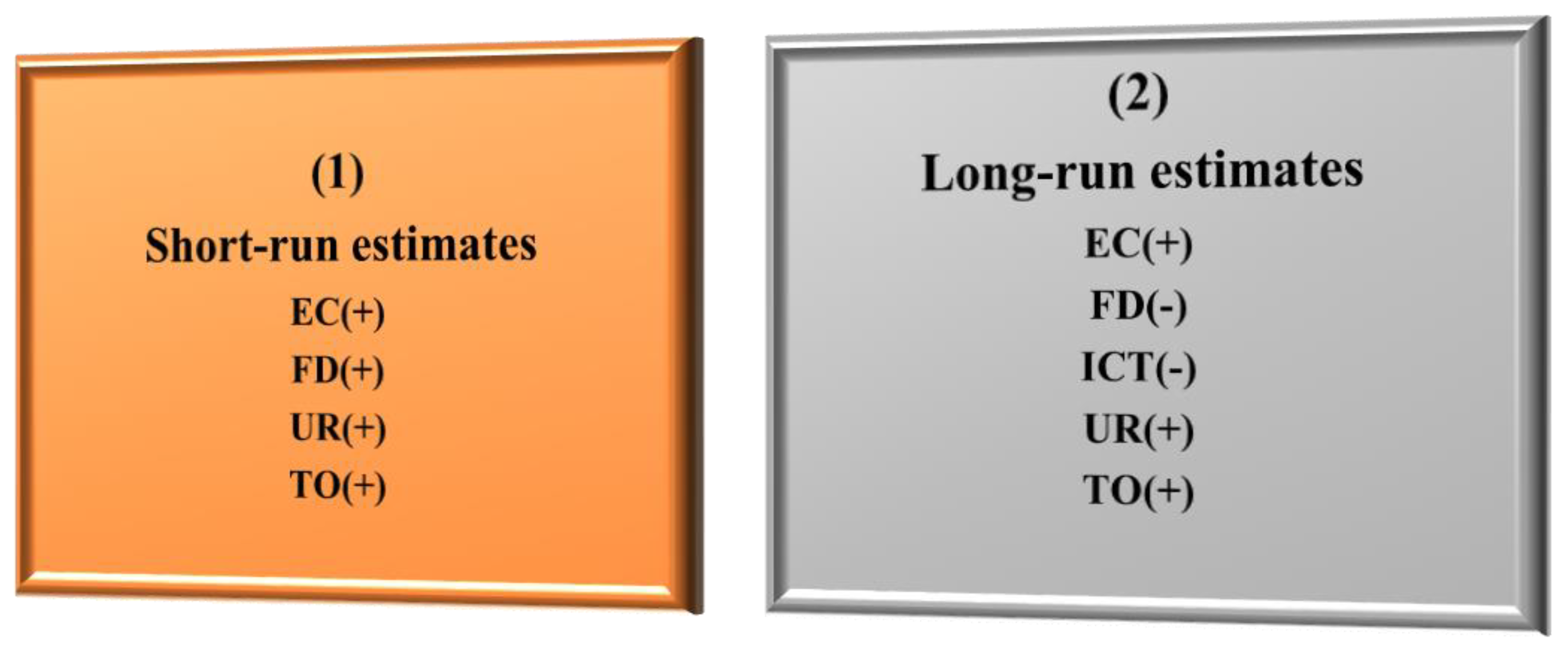

Figure 2.

Summary of major findings.

Figure 2.

Summary of major findings.

We will concentrate the discussion of results on those of model 1. The results of the ARDL model 1 show that the coefficient of GDP squared (LGDP2) is not significant in both the short and long run, indicating that the EKC hypothesis is not valid for Saudi Arabia. This finding is consistent with the main findings of previous studies on Saudi Arabia by Alkhathlan & Javid (2013), Raggad (2018), Alshehry and Belloumi (2017), Kahia et al. (2021b), Alfantookh et al. (2023), and Kahia et al. (2024), but it differs from the results of Mahmood et al. (2020) and Kahia et al. (2021a) which supported the EKC hypothesis. This finding indicates that Saudi Arabia is generally in the early stages of development, and as the economy grows, it has a significant impact on the environment by increasing the demand for natural resources, particularly fossil fuels, and the generation of industrial waste, leading to a decline in environmental quality. Financial development has a negative and significant impact on CO2 emissions in the long run, but it has a positive and significant effect in the short run. Specifically, a 10% increase in financial development may lead to a decrease in CO2 emissions by 0.4% in the long run, while the same increase in financial development may lead to a rise in CO2 emissions by 0.6% in the short run. This result can be attributed to the initial increase in economic activities and environmental pollution caused by financial development in the short term. This is primarily driven by factors like encouraging consumer spending on high-emission products, and facilitating the expansion of companies leading to higher energy consumption. However, in the long run, this trend is reversed as a result of improvements in energy efficiency and technological advancements. Our long-term findings align with Khan et al. (2018), Godil et al. (2020), Habiba & Xinbang (2022), Tao et al. (2023), and Fakher et al. (2024) while our short-term findings align with those of Jiang & Ma (2019). However, our results contradict those reported by Fakher et al. (2018), Omri et al. (2021), Fakher & Murshed (2023), Fakher & Ahmed (2023), Charfeddine et al. (2024), and Nathaniel et al. (2024).

In addition, both variables representing ICT (MCS and IUI) have negative and significant effects on CO2 emissions in the long run but are not significant in the short term. In the long run, MCS has a negative and significant coefficient (-0.05) at a 1% level of significance, indicating that a 10% increase in MCS would lead to about a 0.5% decrease in CO2 emissions. Similarly, IUI has a negative and significant coefficient (-0.16) at a 1% level of significance in the long run, suggesting that a 10% increase in IUI would lead to about a 1.6% decrease in CO2 emissions. These results can be attributed to the advancement of ICT infrastructure in Saudi Arabia, which is a key factor in transitioning the country from a developing nation to an emerging one. The implementation of a modern telecommunications infrastructure utilizing cutting-edge technologies could potentially result in a decrease in CO2 emissions in the long run. These results are consistent with previous studies such as Coroama et al. (2012), Moyer & Hughes (2012), Ozcan & Apergis (2017), Asongu et al. (2017), Batool et al. (2019), Godil et al. (2020), and Charfeddine et al. (2024) but differ from those of Salahuddin & Alam (2015), Haseeb et al. (2019) and Charfeddine & Kahia (2021). However, in the short run, both ICT indicators do not appear to affect CO2 emissions. Therefore, improving information and communication technology could reduce CO2 emissions only in the long run in Saudi Arabia.

This study is the first to show that ICT plays a significant role in reducing CO2 emissions in Saudi Arabia. The findings suggest that advancements in ICT can help accelerate the transition to a greener economy in the country. This new insight adds to the existing literature on the impact of ICT on environmental sustainability.

The variable energy consumption has a positive and significant impact on CO2 emissions in both the long and short run in Saudi Arabia. GDP does not affect CO2 emissions in either the short or long run. Finally, the variables of trade openness and urbanization have positive and significant effects on CO2 emissions in both the short and long run in Saudi Arabia. This suggests that openness to international trade and urbanization may contribute to environmental degradation in Saudi Arabia. The key results of both short-term and long-term estimates are displayed in

Figure 2. The results of models 2 and 3 can be interpreted in the same way.

5. Robustness of Results

To ensure the reliability of our findings, we substitute the variable LCO2 emissions with LGHG emissions in the three ARDL models that we estimate. Both CO2 and GHG emissions are used as indicators of environmental quality. A decrease in either CO2 or GHG emissions signifies an enhancement in environmental quality.

Table 6 displays the outcomes of the Bounds tests. It is clear that the F statistics consistently surpass the upper bounds, even at a significance level of 1%. This indicates the existence of cointegration relationships in all three models that we estimate.

Table 7 presents the findings of the short-term and long-term effects of the independent variables on GHG emissions, as well as the results of the diagnostic tests. The diagnostic tests, which include the Jarque-Bera normality test, the Breusch-Godfrey serial correlation LM test, and the Breusch-Pagan-Godfrey heteroscedasticity LM test, confirm that the error terms in all three ARDL models are normally distributed, uncorrelated, and homoscedastic. When examining the variables of interest (FD, MCS, and IUI), we observe that financial development has a negative and significant coefficient in both the short and long term in all three estimated models. This suggests that financial development may lead to a decrease in GHG emissions and an improvement in environmental quality in Saudi Arabia. The results for the variables representing ICT are mixed, with some showing positive and significant coefficients and others being insignificant in both the short and long term. This indicates that ICT could potentially lead to a rise in greenhouse gas emissions in Saudi Arabia.

6. Conclusion and Policy Recommendations

6.1. Conclusion

Our study aims to analyze the effects of financial development and ICT on environmental quality in Saudi Arabia using the ARDL model from 1990 to 2022. We measure environmental quality through carbon dioxide emissions and GHG emissions. In addition to financial development and ICT variables, we include other factors that affect environmental quality, such as economic growth, energy use, trade openness, and urbanization. The Bounds tests indicate that there are cointegration relationships between the variables studied when considering either CO2 emissions or GHG emissions as dependent variables. Overall, when considering the results of all models estimated, our findings suggest that financial development can improve environmental quality in both the short and long term in Saudi Arabia, while ICT hurts the environment in the short term but has a positive impact in the long term. Furthermore, our findings do not validate the EKC hypothesis in Saudi Arabia, and they confirm the negative effects of economic growth, energy consumption, trade openness, and urbanization on the environment.

6.2. Policy Recommendations

The findings emphasize the importance of ICT and financial development in improving long-term environmental quality, providing valuable insights for policymakers. It is essential for policymakers to focus on promoting cleaner ICT technologies to stimulate innovation. Furthermore, the study underscores the significance of financial development in enhancing environmental quality. Policymakers should consider facilitating access to digital financial services, especially in industries with significant environmental footprints, to support this objective. Promoting policies that foster financial sector growth can enhance environmental conditions. Increased financial development offers an opportunity to invest in sustainable industries, reducing carbon emissions. Empirical findings suggest that investing in clean energy projects can lower emissions. Implementing green ICT projects in the financial sector can improve energy efficiency in Saudi Arabia. However, the short-term negative effects of ICT on the environment should be considered. Saudi Arabia should increase investments in green ICT to address environmental concerns. Green ICT focuses on monitoring, managing applications, improving energy efficiency, and product recycling. Developing environmentally friendly ICT products and services can minimize environmental impact. Green ICT is crucial for sustainable economic development through initiatives like green banking, trade, governance, and buildings. It also plays a vital role in environmental protection, sustainability, education, and rural development. Green ICT aims to produce materials with minimal environmental impact, reduce energy consumption, and enhance recycling efforts.

Saudi Arabia's financial system can help reduce CO2 emissions by supporting companies working to decarbonize the economy and pressuring others to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Policymakers should raise awareness about the costs and benefits of ICT and support emission-reducing policies. Pollution control technology, recycling, and reducing electronic waste can also contribute to emission reduction efforts. All these policies could contribute to accelerating the diversification of economic activities, reducing dependence on oil, and achieving the greenhouse gas emission reduction targets set out in Saudi Vision 2030.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research Recommendations

Our research is limited by the relatively short time period, as data for some variables before 1990 was not available. Despite this constraint, our study provides valuable insights into Saudi Arabia as a major oil-producing country. The use of the ARDL model effectively addresses this limitation and is well-suited for analyzing data for a limited timeframe. While this study delves deeply into the relationship between ICT, financial development, and environmental quality, there is potential for additional research to examine this relationship in various developmental settings. Subsequent studies could investigate how governance mechanisms in Saudi Arabia can utilize ICT to improve environmental quality. Furthermore, a study focusing on a disaggregated level, such as the industrial or transport sector, could offer more precise insights into the impact of ICT on environmental quality. Lastly, an empirical investigation into the effects of economic diversification under Saudi Vision 2030 on environmental quality would be a compelling area for further research.

References

- Alfantookh, N. , Osman, Y., Ellaythey, I., 2023. Implications of Transition towards Manufacturing on the Environment: Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 Context. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 16: 44. [CrossRef]

- AlKhars, M.A. , Alwahaishi, S., Fallatah, M.R., Kayal, A., 2022. A literature review of the Environmental Kuznets Curve in GCC for 2010-2020. Environmental and Sustainability Indicators, 14, 100181. [CrossRef]

- Alkhathlan, K. , Javid, M., 2013. Energy consumption, carbon emissions and economic growth in Saudi Arabia: An aggregate and disaggregate analysis. Energy Policy, 62, 1525-1532. [CrossRef]

- Al-Mulali, U. , Sheau-Ting, L., Ozturk, I., 2015. The global move toward Internet shopping and its influence on pollution: An empirical analysis. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 22(13), 9717–9727.

- Alshehry, A. , Belloumi, M., 2015. Energy consumption, Carbon dioxide emissions and Economic Growth: The case of Saudi Arabia. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 41, 237-247.

- Alshehry, A. , Belloumi, M., 2017. Study of the environmental Kuznets curve for transport carbon dioxide emissions in Saudi Arabia. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 75, 1339-1347.

- Amri, F. , Zaied, Y.B., Lahouel, B.B., 2019. ICT, total factor productivity, and carbon dioxide emissions in Tunisia. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 146, 212–217.

- Andrianaivo, M. , Kpodar, K., 2012. Mobile phones, financial inclusion, and growth. Review of economics and institutions 3(2), 1–30.

- Asongu, S.A. , 2018. ICT, openness and CO2 emissions in Africa. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 25, 9351-9359. [CrossRef]

- Asongu, S. A. , Le Roux, S., Biekpe, N., 2017. Enhancing ICT for environmental sustainability in Sub-Saharan Africa. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 118, 44–54.

- Avom, D. , Nkengfack, H., Fotio, H. K., Totouom, A., 2020. ICT and environmental quality in Sub-Saharan Africa: Effects and transmission channels. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 155, 120028.

- Batool, R. , Sharif, A., Islam, T., Zaman, K., Shoukry, A.M., Sharkawy, M.A., Hishan, S.S., 2019. Green is clean: the role of ICT in resource management. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 26 (24), 25341–25358.

- Belloumi, M. , Alshehry, A., 2016. The Impact of Urbanization on Energy Intensity in Saudi Arabia. Sustainability, 8 (4), 375.

- Belloumi, M. , Touati, K., 2022. Do FDI Inflows and ICT Affect Economic Growth? An Evidence from Arab Countries. Sustainability 14, 6293. [CrossRef]

- Charfeddine, L. , and Kahia, M., 2021. Do information and communication technology and renewable energy use matter for carbon dioxide emissions reduction? Evidence from the Middle East and North Africa region. Journal of Cleaner Production, 327, 129410. [CrossRef]

- Charfeddine, L. , Hussain, B., Kahia, M., 2024. Analysis of the Impact of Information and Communication Technology, Digitalization, Renewable Energy and Financial Development on Environmental Sustainability. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 201, 114609. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. , Gong, X., Li, D., Zhang, J., 2019. Can information and communication technology reduce CO2 emission? A quantile regression analysis. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 26, 32977–32992. [CrossRef]

- Coroama, C. , Hilty, L.M., Birtel, M., 2012. Effects of Internet-based multiple-site conferences on greenhouse gas emissions. Telematics and Informatics 29(4), 362-374.

- Danish, K.N. , Baloch, M.A., Saud, S., Fatima, T., 2021. The effect of ICT on CO2 emissions in emerging economies: does the level of income matters? Environmental Science and Pollution Research 25(23), 22850–22860. [CrossRef]

- Datta, A. , Agarwal, S., 2004. Telecommunications and economic growth: a panel data approach. Applied Economics 36(15), 1649–1654.

- Dickey, D.A. , Fuller, W.A., 1979. Distribution of the estimators for autoregressive time series with a unit root. Journal of the American Statistical Association 74, 427–431.

- Elliott, G. , Rothenberg, T.J., Stock, J.H., 1996. Efficient tests for an autoregressive unit root. Econometrica 64, 813–836.

- Engle, R. , Granger, C., 1987. Cointegration and Error Correction: Representation, Estimation and Testing. Econometrica 55, 251-276. [CrossRef]

- Fakher, H. A. , Abedi, Z., Shaygani, B., 2018. Investigating the relationship between trade and financial openness with ecological footprint. Quarterly journal of economical modelling, 11(40), 49-67. (In Persian). http://eco.iaufb.ac.ir/article_604867.html?lang=en.

- Fakher, H.A. , Ahmed, Z., 2023. Does financial development moderate the link between technological innovation and environmental indicators? An advanced panel analysis. Financial Innovation, 9(1), 112. [CrossRef]

- Fakher, H. A. , Murshed, M., 2023. Does financial and economic expansion allow for environmental sustainability? Fresh insights from a new composite index and PSTR analysis. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 67(12), 2885-2908. [CrossRef]

- Fakher, H. A. , Nathaniel, S. P., Ahmed, Z., Ahmad, M., Moradhasel, N., 2024. The environmental repercussions of financial development and green energy in BRICS economies: From the perspective of new composite indices. Energy & Environment, 0(0). [CrossRef]

- Fosten, J. , Morley, B., Taylor, T., 2012. Dynamic misspecification in the environmental Kuznets curve: evidence from CO2 and SO2 emissions in the United Kingdom. Ecological Economics 76, 25e33.

- Godil, D.I. , Sharif, A., Agha, H., Jermsittiparsert, K., 2020. The dynamic nonlinear influence of ICT, financial development, and institutional quality on CO2 emission in Pakistan: new insights from QARDL approach. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 27, 24190–24200. [CrossRef]

- Habiba, U. , Xinbang, C., 2022. The impact of financial development on CO2 emissions: new evidence from developed and emerging countries. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 29, 31453–31466. [CrossRef]

- Haseeb, A. , Xia, E., Saud, S., Ahmad, A., Khurshid, H., 2019. Does information and communication technologies improve environmental quality in the era of globalization? An empirical analysis. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 26(9), 8594–8608.

- Higon, D.A. , Gholami, R., Shirazi, F., 2017. ICT and environmental sustainability: A global perspective. Telematics and Informatics 34(4), 85-95.

- Jalil, A. , Mahmud, S.F., 2009. Environment Kuznets curve for CO2 emissions: a cointegration analysis for China. Energy Policy 37, 5167– 5172.

- Jiang, C., Ma, X., 2019. The Impact of Financial Development on Carbon Emissions: A Global Perspective. Sustainability 11(19), 5241. [CrossRef]

- Johansen, S. , 1988. Statistical Analysis of Cointegrating Vectors. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 12, 231-254.

- Kahia, M., Omri, A., Jarraya, B., 2021a. Green Energy, Economic Growth and Environmental Quality Nexus in Saudi Arabia. Sustainability, 13(3):1264. [CrossRef]

- Kahia, M., Omri, A., Jarraya, B., 2021b. Does Green Energy Complement Economic Growth for Achieving Environmental Sustainability? Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Sustainability, 13(1), 180. [CrossRef]

- Kahia, M., Jarraya, B., Kahouli, B., Omri, A., 2023. Do Environmental Innovation and Green Energy Matter for Environmental Sustainability? Evidence from Saudi Arabia (1990–2018). Energies, 16(3):1376. [CrossRef]

- Kahia, M. , Jarraya, B., kahouli, B. Omri, A., 2024. The Role of Environmental Innovation and Green Energy Deployment in Environmental Protection: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Journal of Knowledge Economy, 15, 337-363. [CrossRef]

- Khan, D.N. , Baloch, M.A., Saud, S., Fatima, T., 2018. The level of ICT on CO2 emissions in emerging economies: Does the level of income matters? Environmental Science and Pollution Research 25(23), 22850-22860.

- Kripfganz, S. , Schneider, D.C., 2023. ARDL: Estimating autoregressive distributed lag and equilibrium correction models. The Stata Journal, 23 (4), 983–1019.

- Le, T.H. , 2021. Drivers of greenhouse gas emissions in ASEAN + 6 countries: a new look, Environment, Development and Sustainability: A Multidisciplinary Approach to the Theory and Practice of Sustainable Development, Springer 23(12), 18096-18115.

- Mahmood, H. , Tawfik, T., Alkhateeb, Y., Furqan, M., 2020. Oil sector and CO2 emissions in Saudi Arabia: Asymmetry analysis. Palgrave Communications, 6, 1-10.

- Mahmood, H., Furqan, M., Meraj, G., Shahid Hassan, M., 2024a. The effects of COVID-19 on agriculture supply chain, food security, and environment: a review. PeerJ 12:e17281. [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, H. , Meraj, G., Meraj, G., Shahid Hassan, M., Furgan, M., 2024b. Bioenergy Expansion and Economic Sustainability from Environment-Energy-Food Security Nexus: A Review. International Journal of Sustainable Development and Planning, 2813-2823.

- Magazzino, C. , Porrini, D., Fusco, G., Schneider, N., 2021. Investigating the link among ICT, electricity consumption, air pollution, and economic growth in EU countries. Energy Sources, Part B: Economics, Planning, and Policy.

- Moreau, F. , Aligishiev, Z., 2024. Diversification in sight? A macroeconomic assessment of Saudi Arabia’s vision 2030. International Economics, 180, 100538.

- Moyer, J.D. , Hughes, B.B., 2012. ICTs: do they contribute to increased carbon emissions? Technological Forecasting and Social Change 79(5), 919-931.

- Nathaniel, S.P. , Ahmed, Z., Shamansurova, Z., Fakher, H.A., 2024. Linking clean energy consumption, globalization, and financial development to the ecological footprint in a developing country: Insights from the novel dynamic ARDL simulation techniques. Heliyon, 10(5), e27095.

- Omri, A. , Kahia, M. & Kahouli, B., 2021. Does good governance moderate the financial development-CO2 emissions relationship? Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 28, 47503–47516. [CrossRef]

- Ozcan, B. , Apergis, N., 2017. The impact of Internet use on air pollution: evidence from emerging countries. Environmental Science Pollution Research 25(5), 4174–4189.

- Pao, H.T. , Tsai, C.M., 2011. Modeling and forecasting the CO2 emissions, energy consumption, and economic growth in Brazil. Energy 36(5), 2450–2458.

- Pesaran, M.H. , Shin, Y., Smith, R.J., 2001. Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. Journal of Applied Economics 16, 289-326.

- Phillips, P. C. B. , Perron, P., 1988. Testing for a unit root in time series regression. Biometrika 75, 335–346. [CrossRef]

- Raggad, B. , 2018. Carbon dioxide emissions, economic growth, energy use, and urbanization in Saudi Arabia: evidence from the ARDL approach and impulse saturation break tests. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 25, 14882-14898. [CrossRef]

- Raheem, I.D. , Tiwari, A.K., Balsalobre-Lorente, D., 2020. The role of ICT and financial development in CO2 emissions and economic growth. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 27:1912–22. [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, M. , Gupta, M. b., Srivastava, P., 2021. Does information and communication technology and financial development lead to environmental sustainability in India? An empirical insight. Telematics and Informatics 60, 101598.

- Salahuddin, M. , Alam, K., 2015. Internet usage, electricity consumption and economic growth in Australia: A time series evidence. Telematics and Informatics 32, 862–878.

- Shabani, Z.D., Shahnazi, R., 2019. Energy consumption, carbon dioxide emissions, information and communications technology, and gross domestic product in Iranian economic sectors: a panel causality analysis. Energy 169, 1064–1078.

- Shehzad, K. , Xiaoxing, L., Sarfraz, L., 2021. Envisaging the asymmetrical association among FDI, ICT, and climate change: a case from developing country. Carbon Management 12(2), 123–137. [CrossRef]

- Shoaib, H.M. , Rafique, M.Z., Nadeem, A.M., Huang, S., 2020. Impact of financial development on CO2 emissions: A comparative analysis of developing countries (D8) and developed countries (G8). Environmental Science and Pollution Research 27, 12461–12475. [CrossRef]

- Tao, M. , Sheng, M.S., Wen, L., 2023. How does financial development influence carbon emission intensity in the OECD countries: Some insights from the information and communication technology perspective. Journal of Environmental Management 335, 117553. [CrossRef]

- Tsaurai, K. , Chimbo, B., 2019. The Impact of Information and Communication Technology on Carbon Emissions in Emerging Markets. International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy 9(4), 320-326.

- Wang, J. , Xu, Y., 2021. Internet Usage, Human Capital and CO2 Emissions: A Global Perspective. Sustainability 13, 8268. https:// doi.org/10.3390/su13158268.

- WDI, 2023. World Development Indicators database of the World Bank. Washington.

- Yang, W.J. , Tan, M.Z., Chu, S.H., Chen, Z., 2023. Carbon emission and financial development under the “double carbon” goal: Considering the upgrade of industrial structure. Frontiers in Environmental Science 10,1091537. [CrossRef]

- Yu, X. , Kuruppuarachchi, D., Kumarasinghe, S., 2023. Financial development, FDI, and CO2 emissions: does carbon pricing matter? [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.G. , Liu, C., 2015. The impact of ICT industry on CO2 emissions: A regional analysis in China. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Review 44, 12–19.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).