Submitted:

13 March 2025

Posted:

14 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Establishment of Parameters

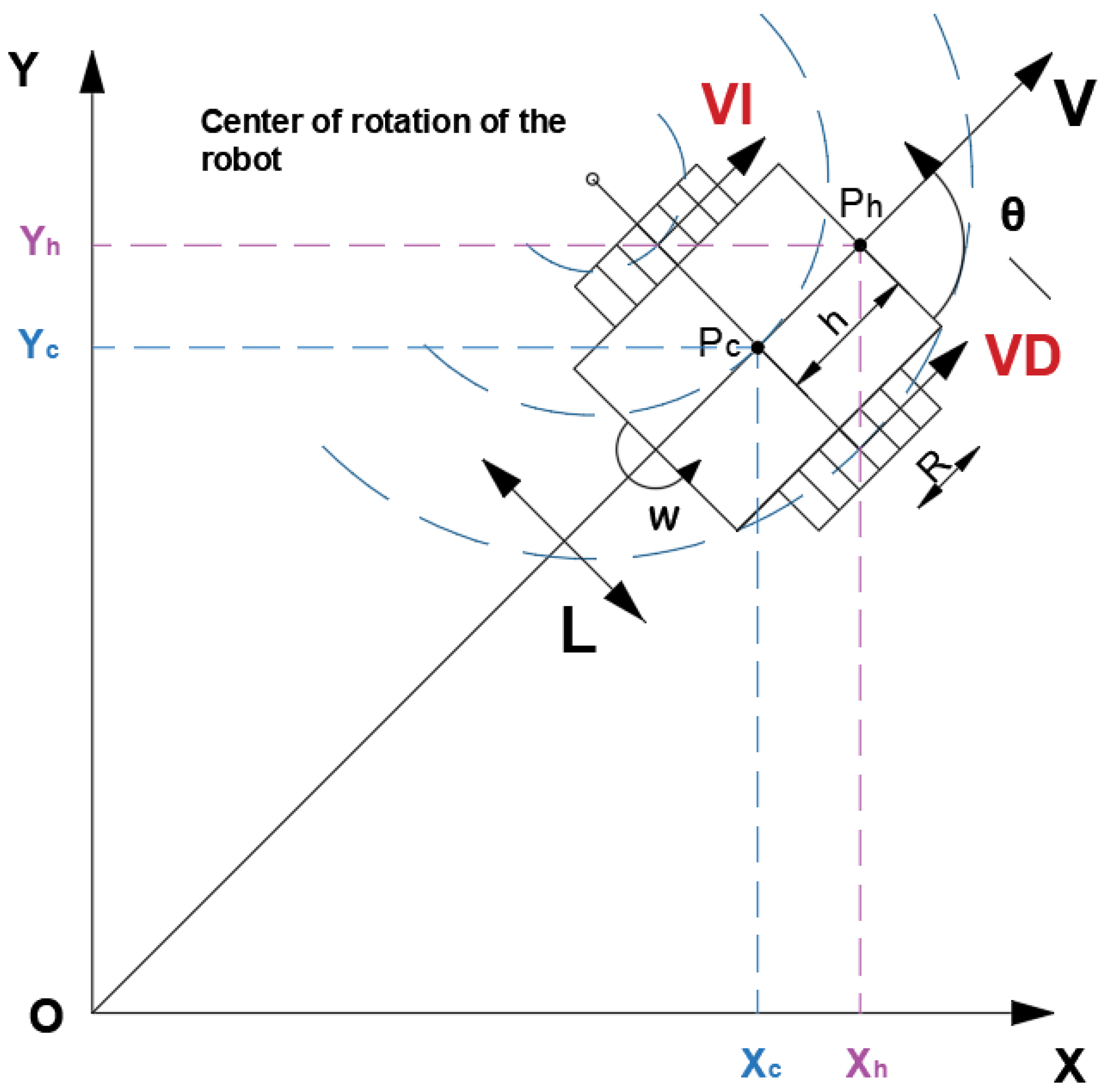

2.1.1. Robot Kinematic Model

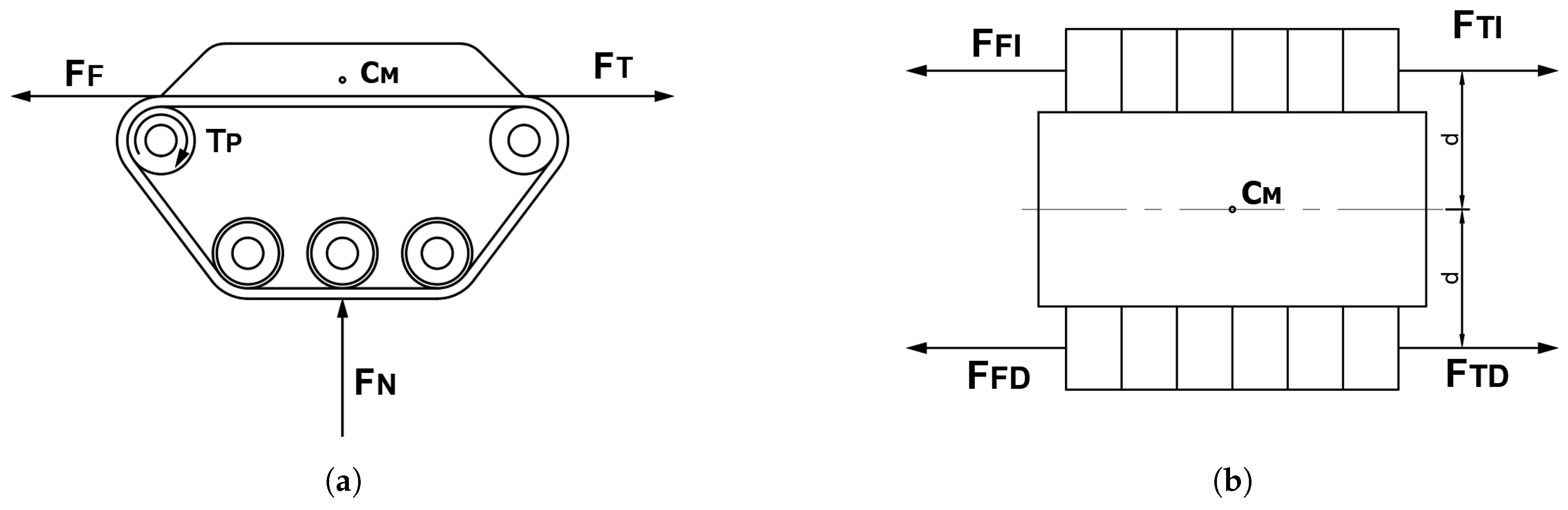

2.1.2. Dynamic Model of the Robot

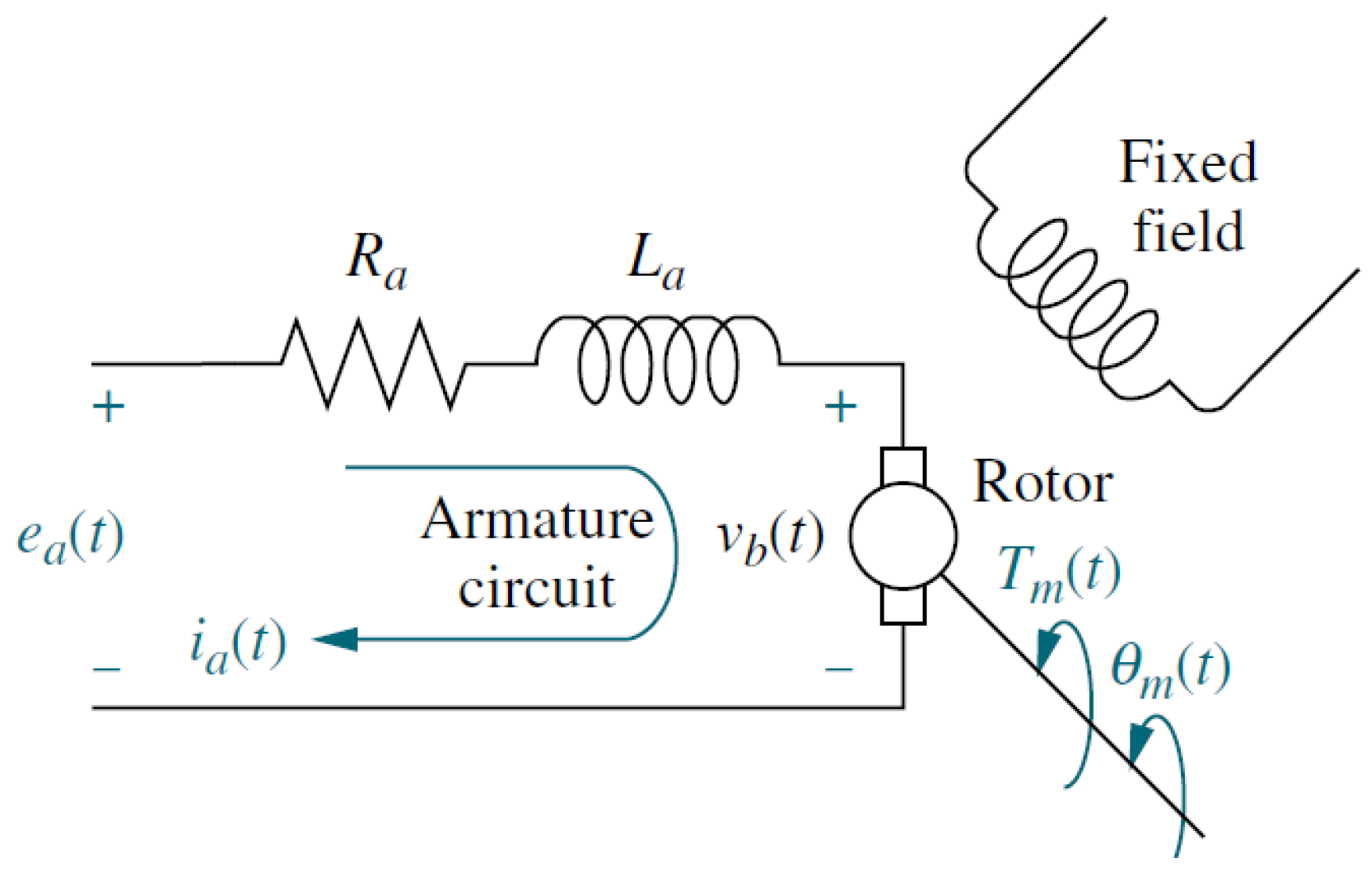

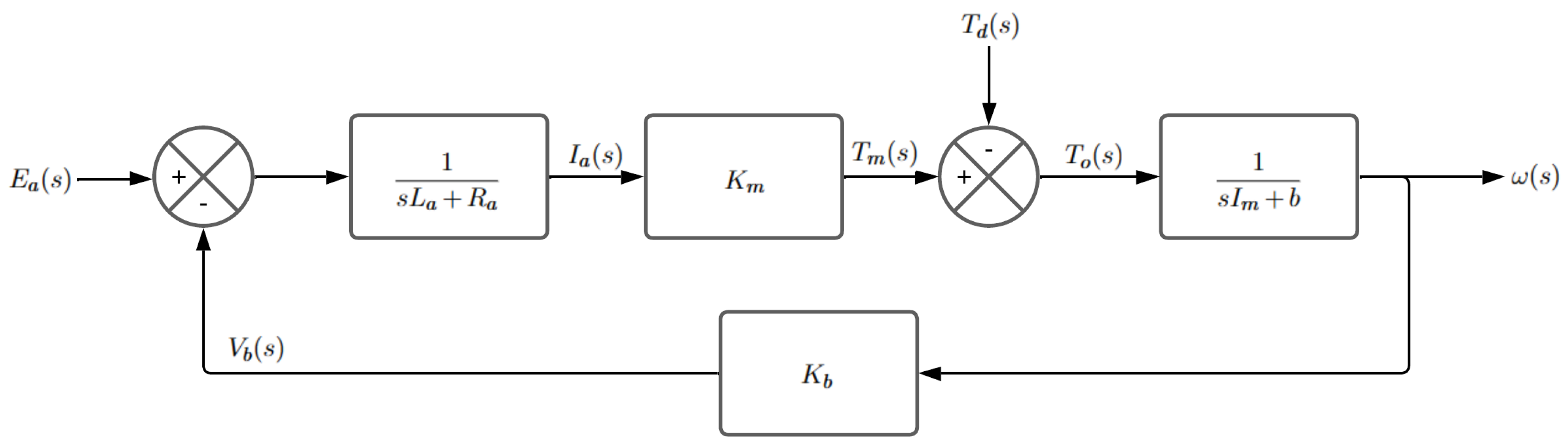

2.1.3. Parameters for the Control System

2.2. Design Proposal

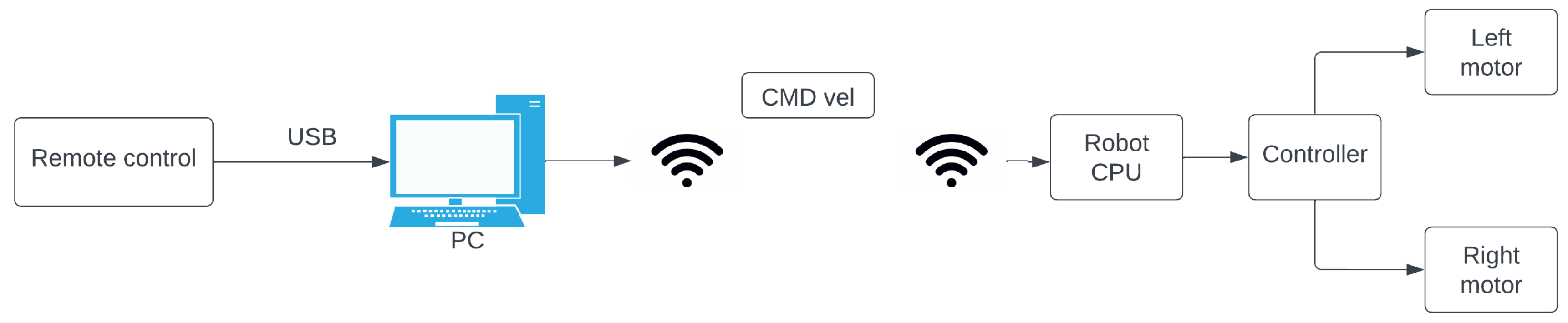

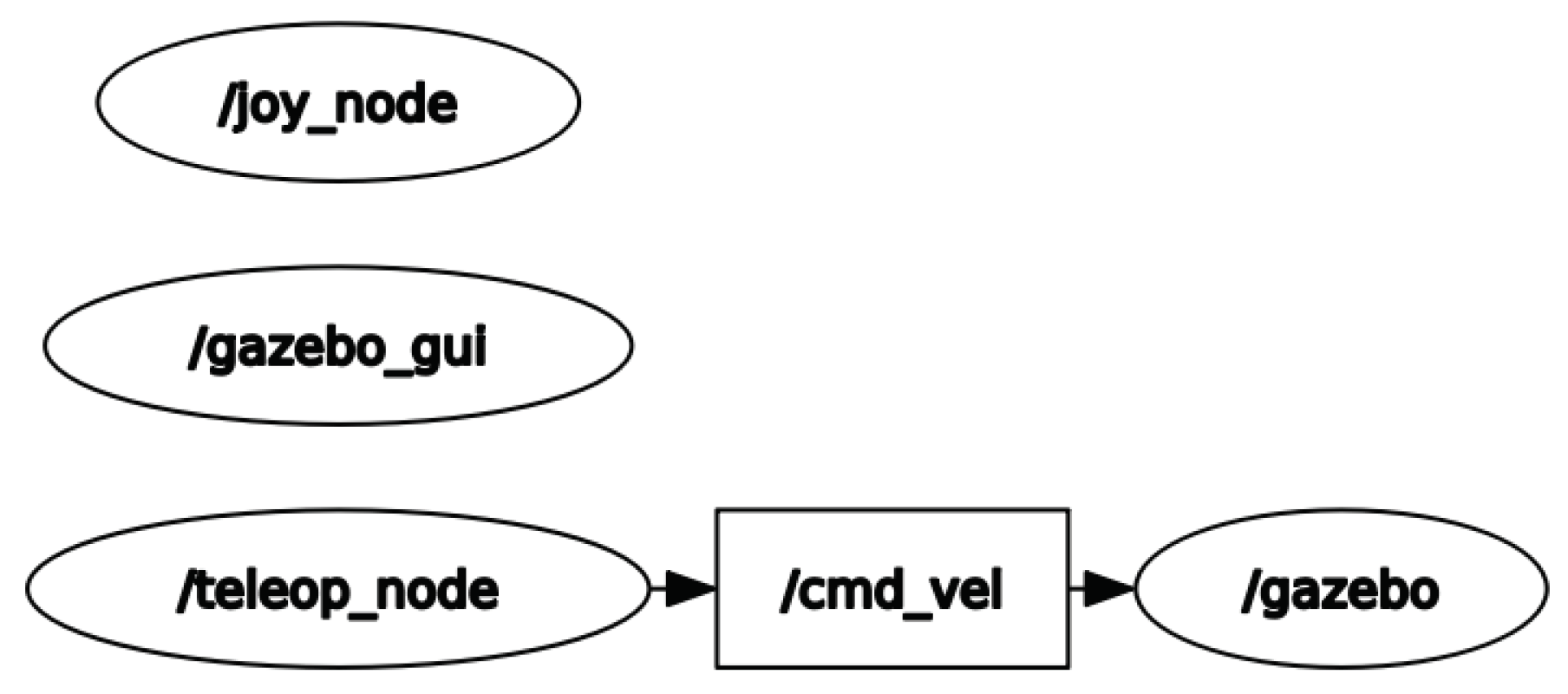

2.2.1. Programming the Robot in ROS

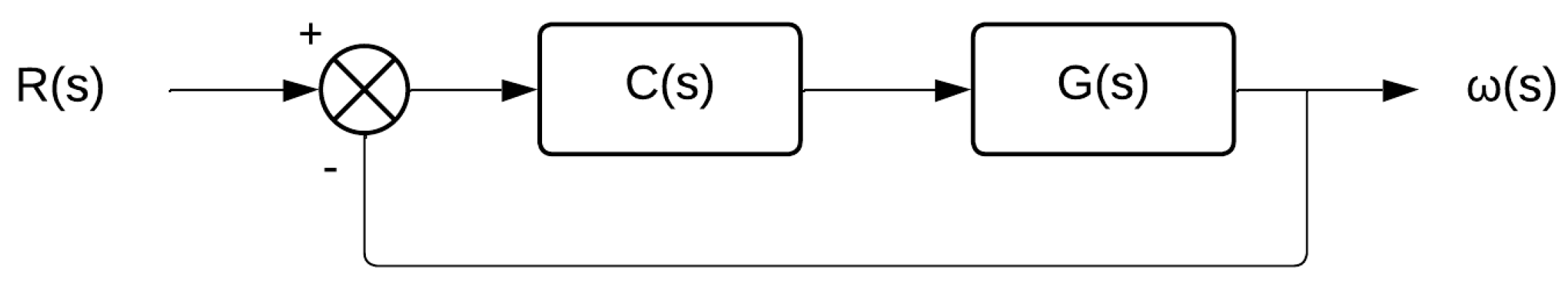

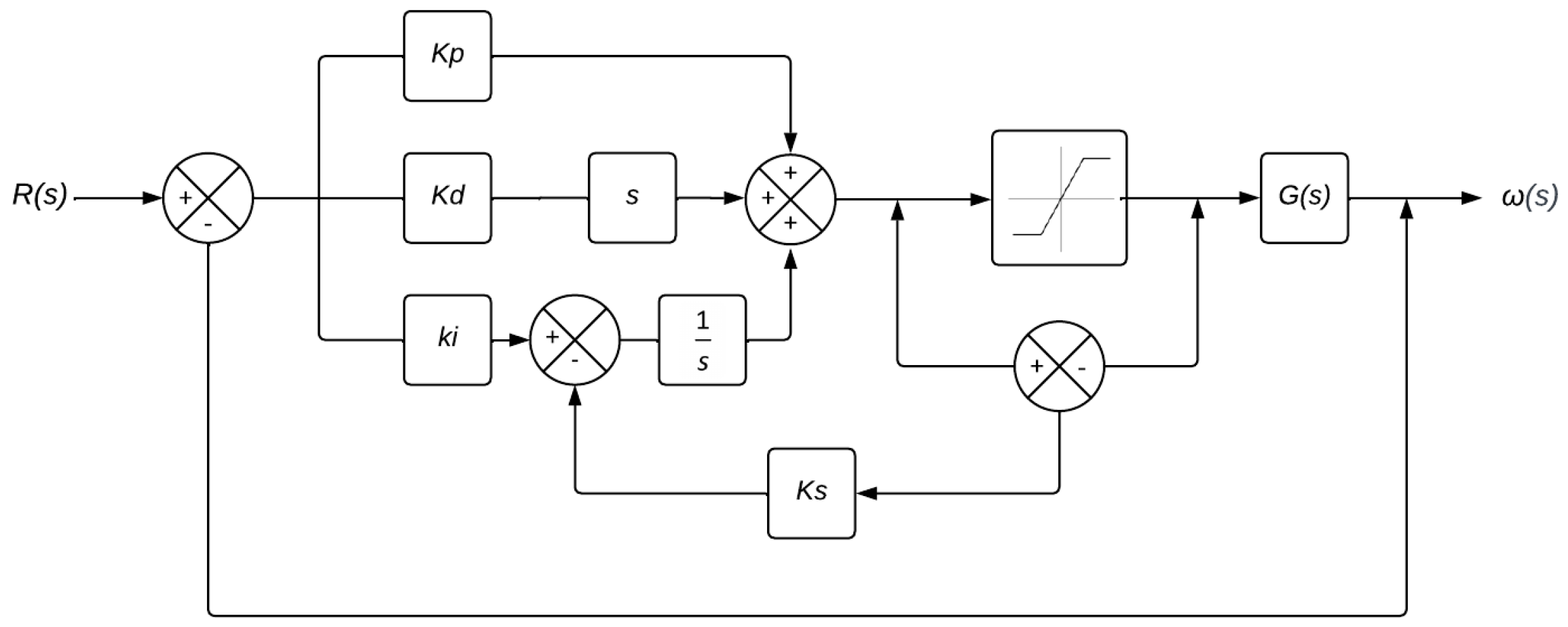

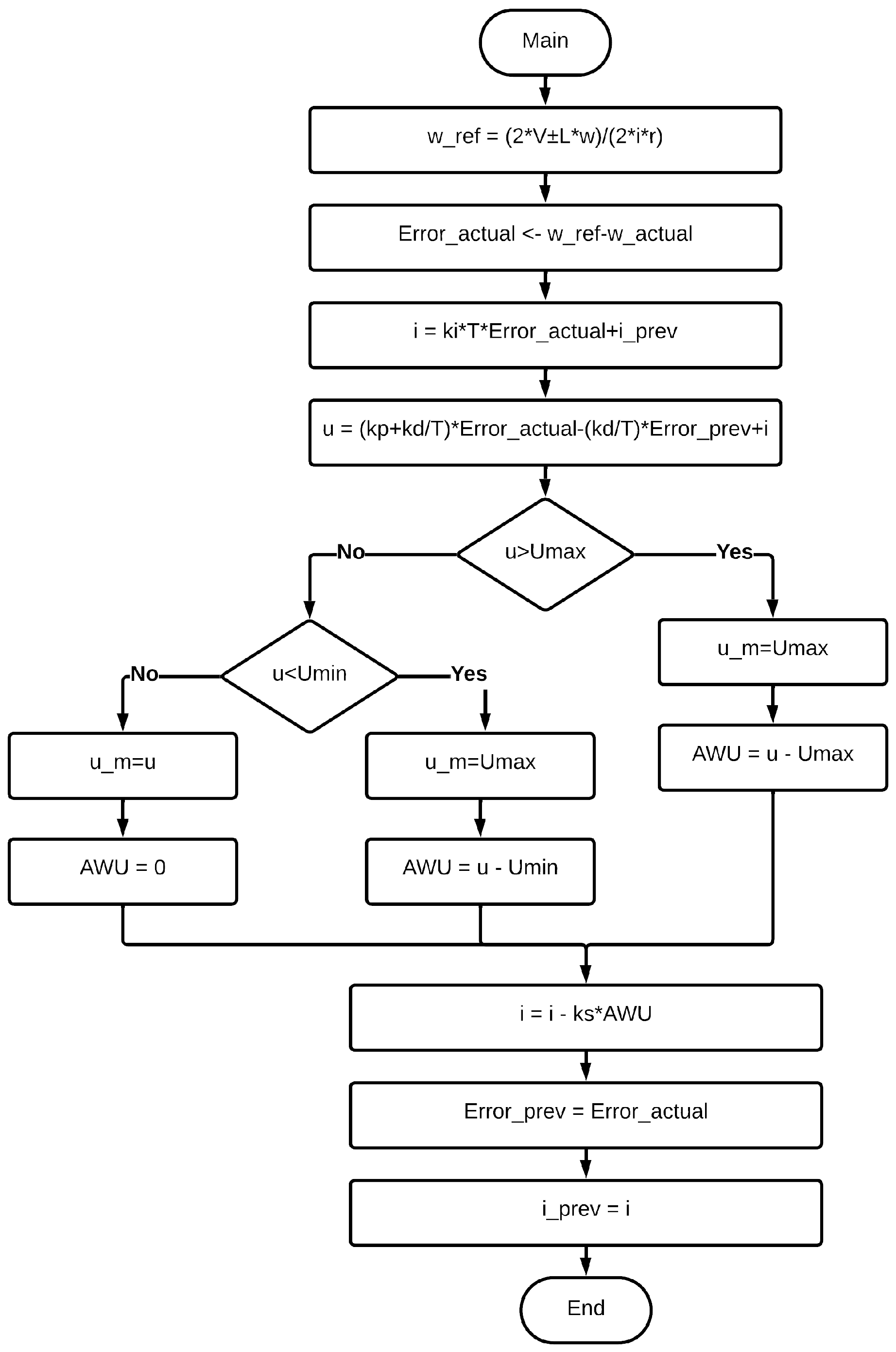

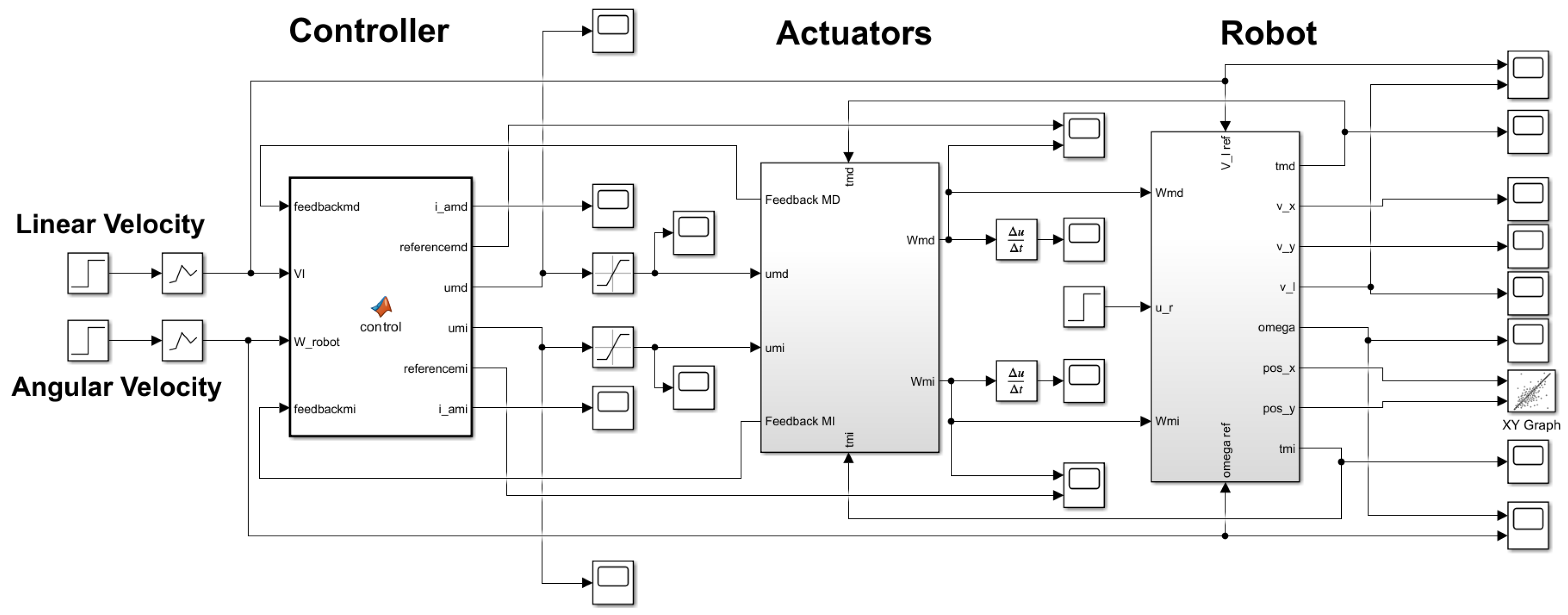

2.2.2. Design of the Control System

3. Results

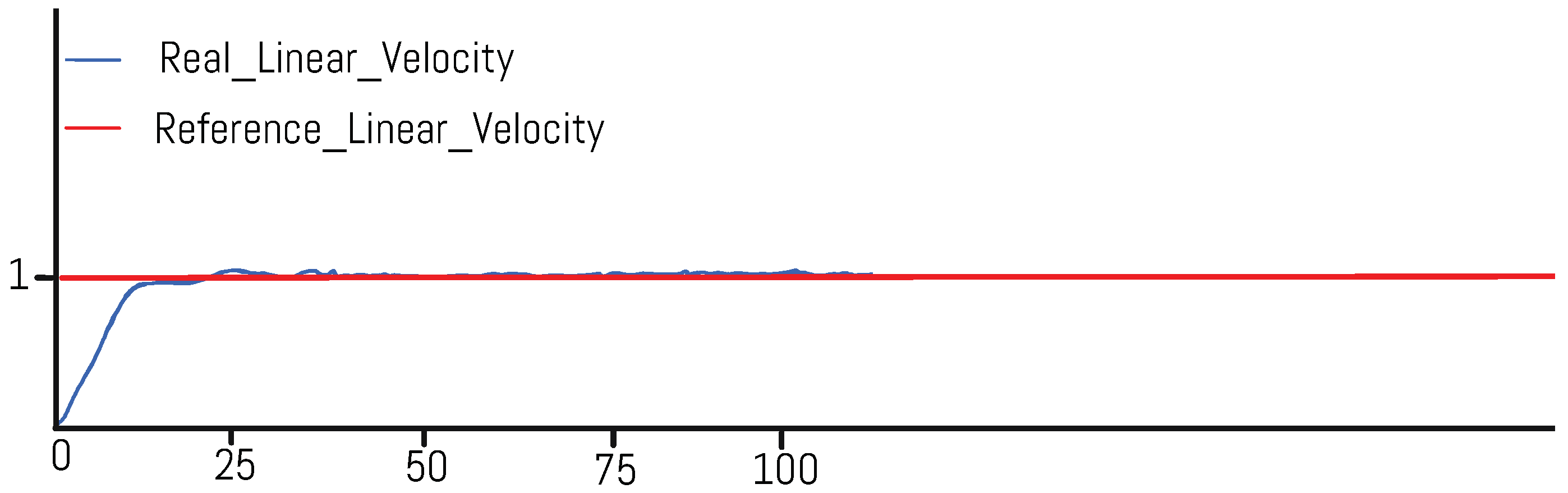

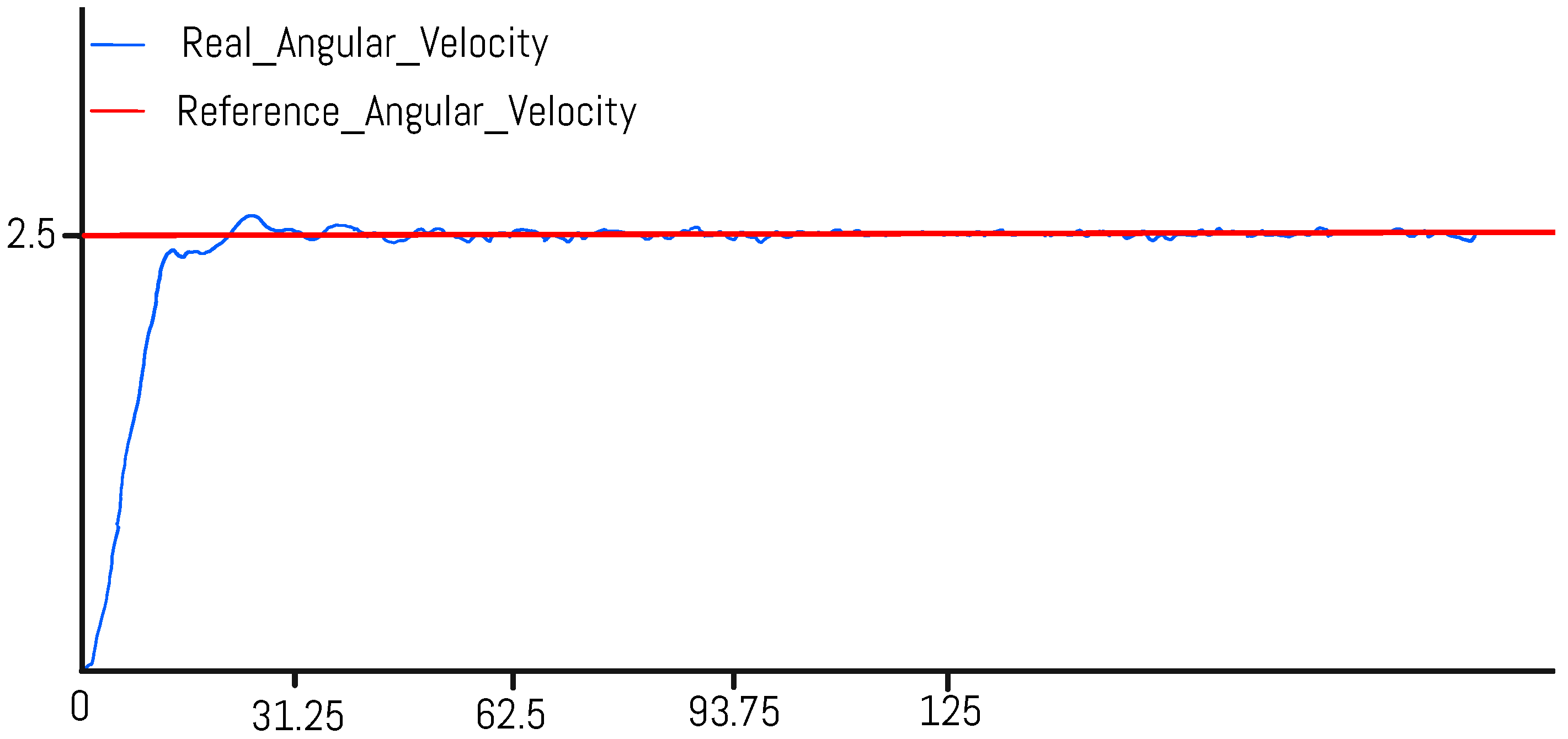

3.1. Implementation of ROS Nodes in Gazebo

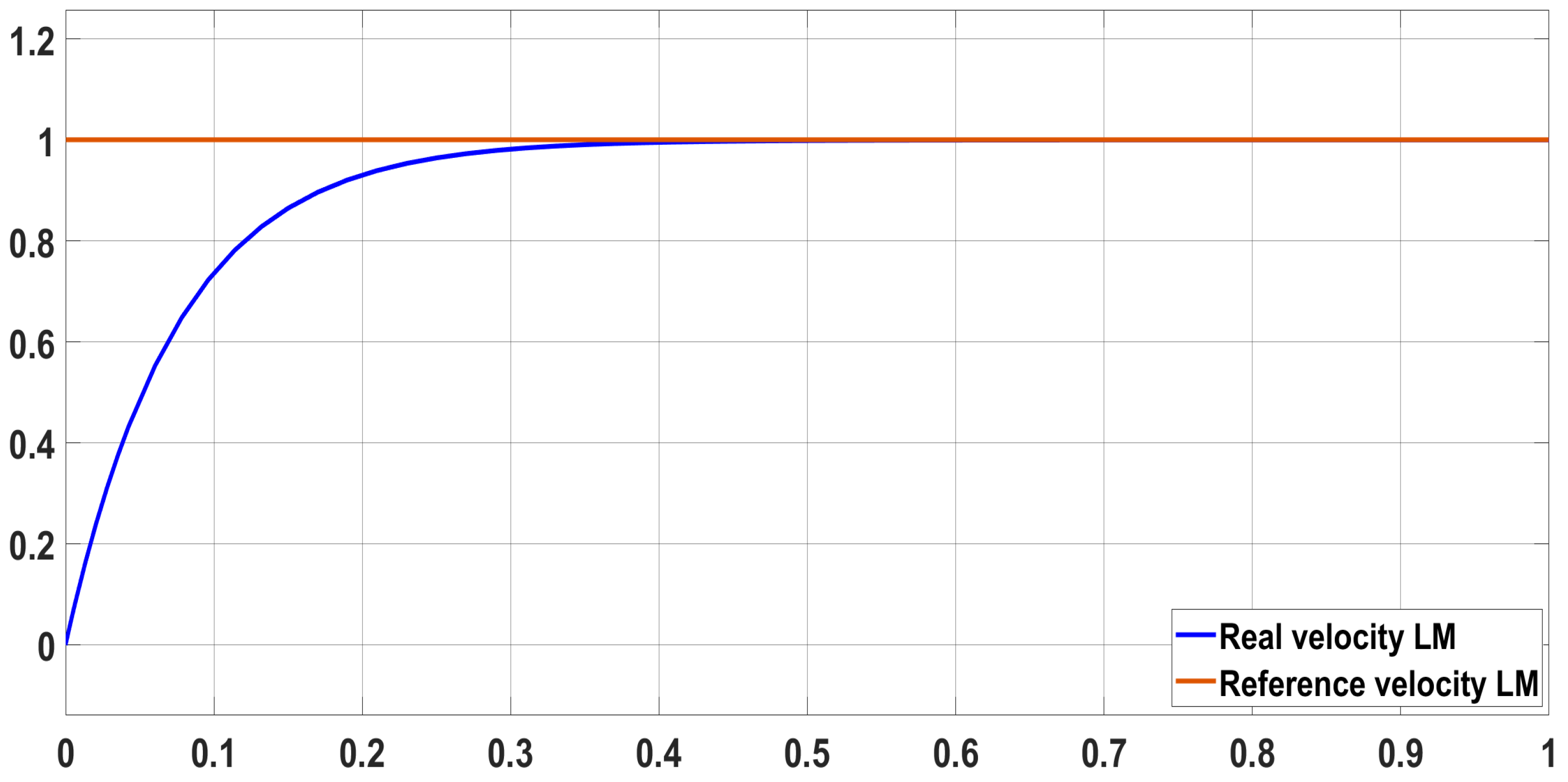

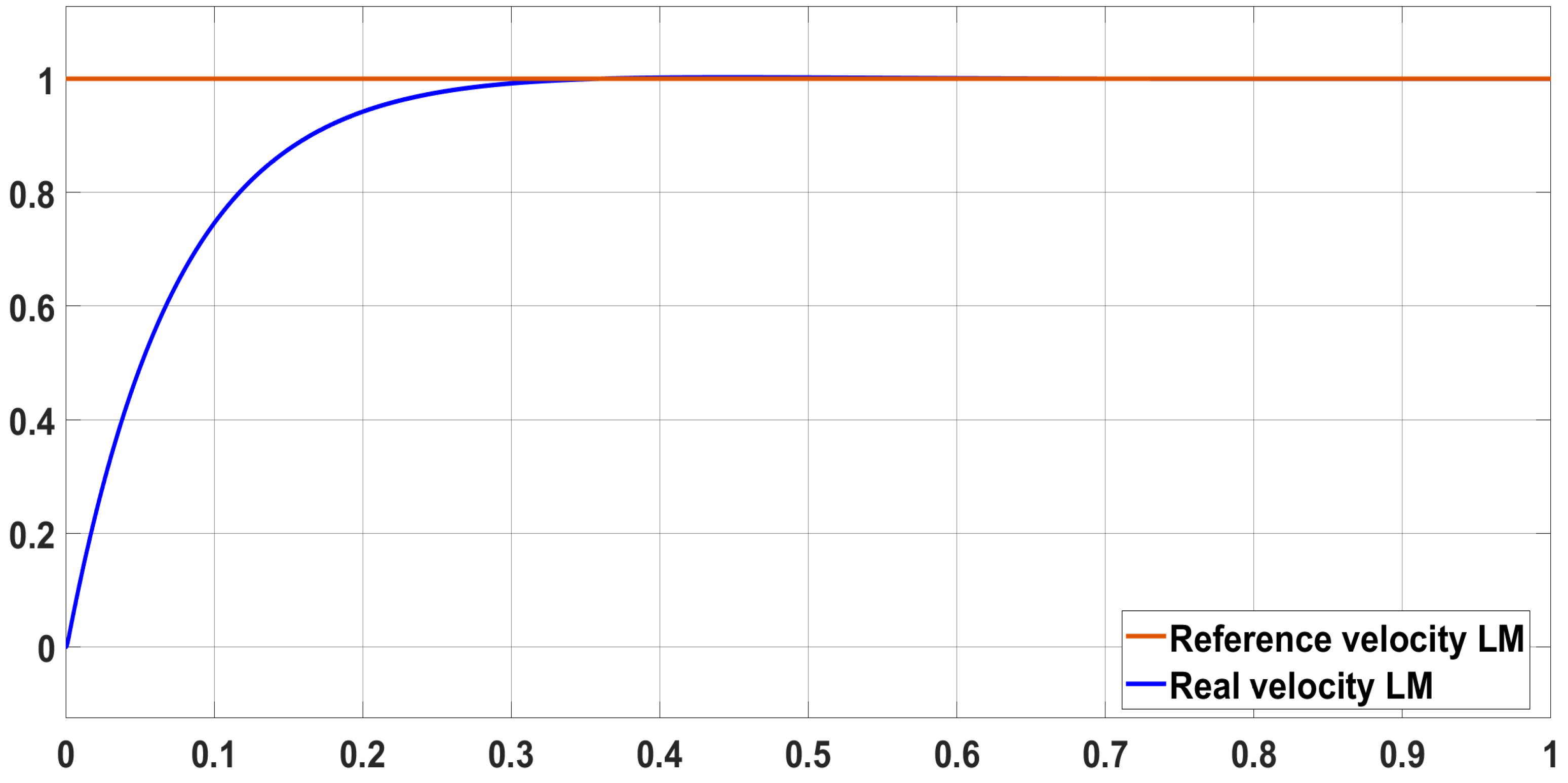

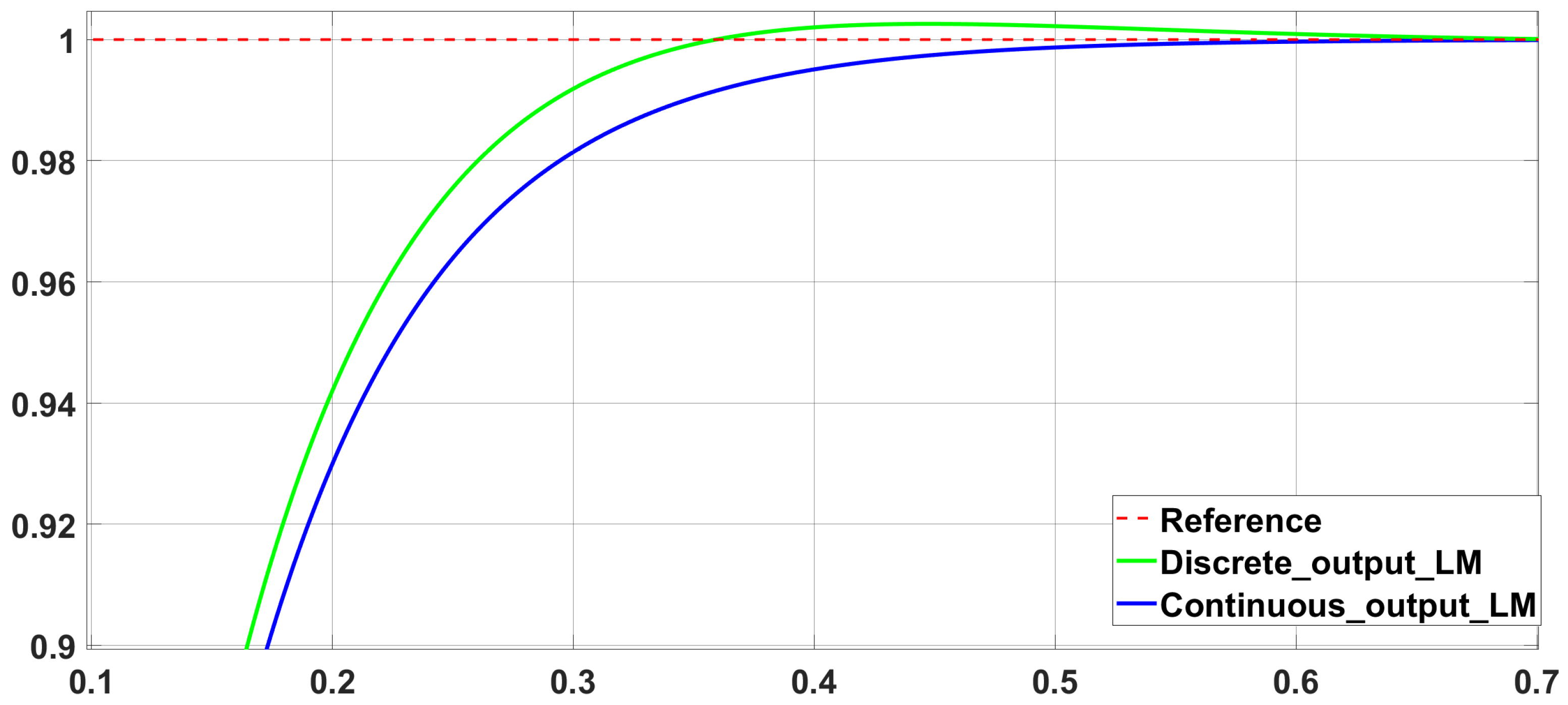

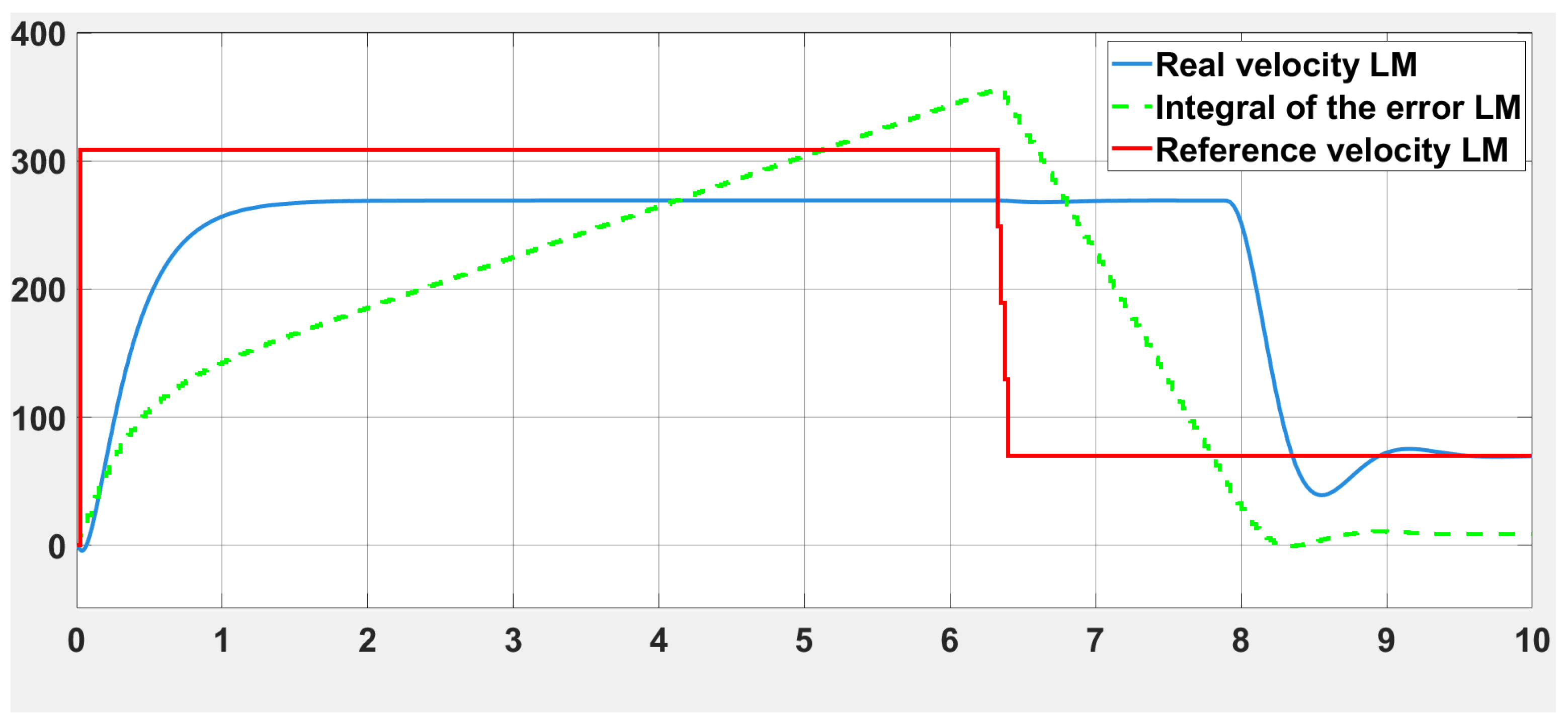

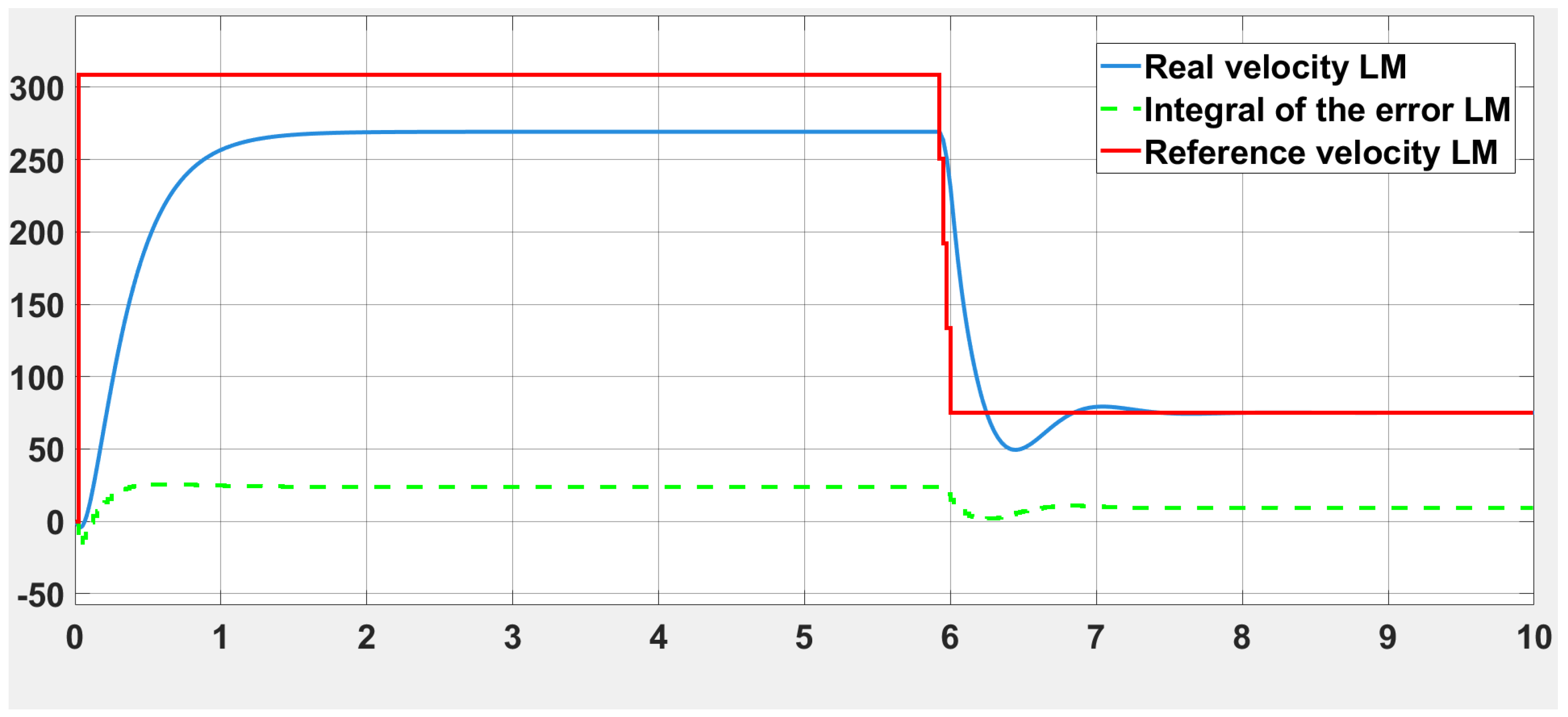

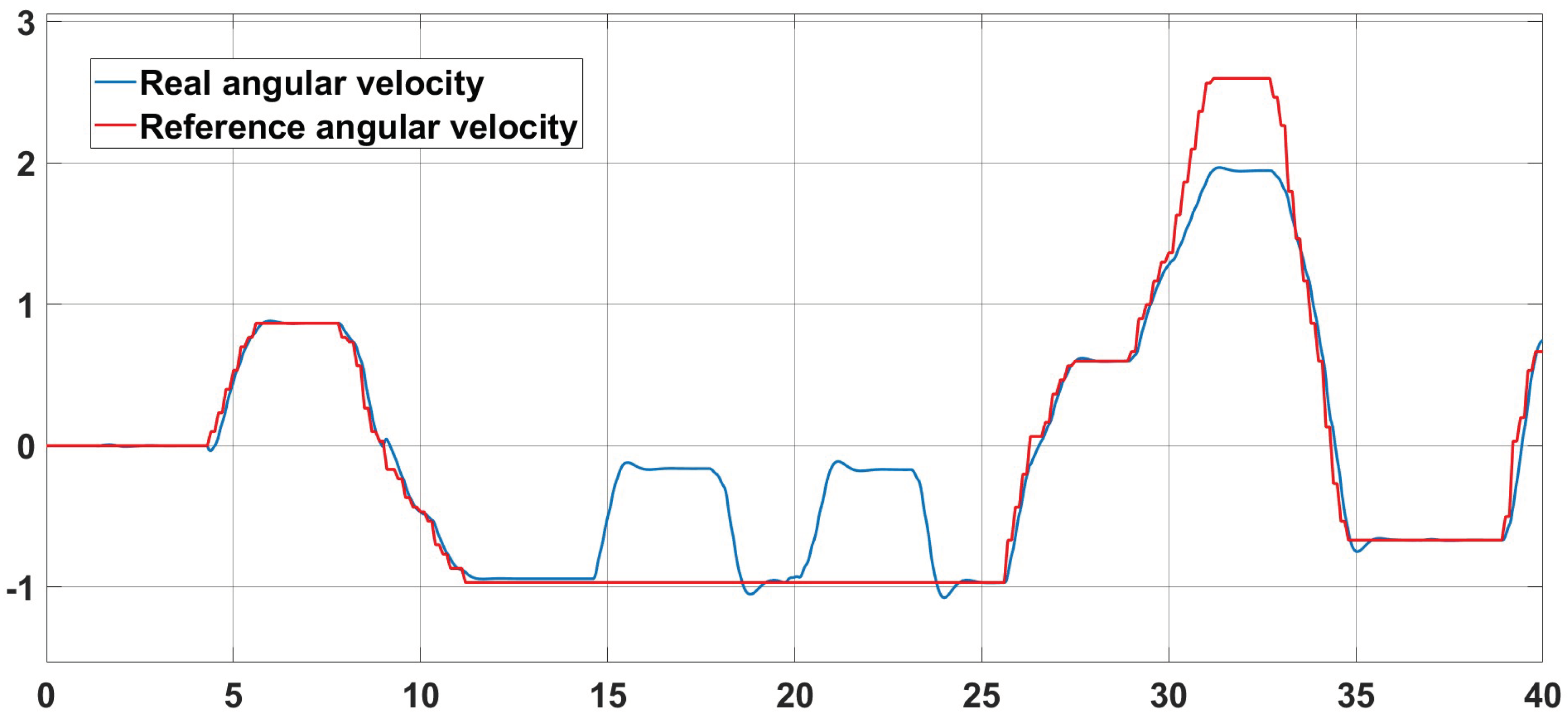

3.2. Simulation of the Control System

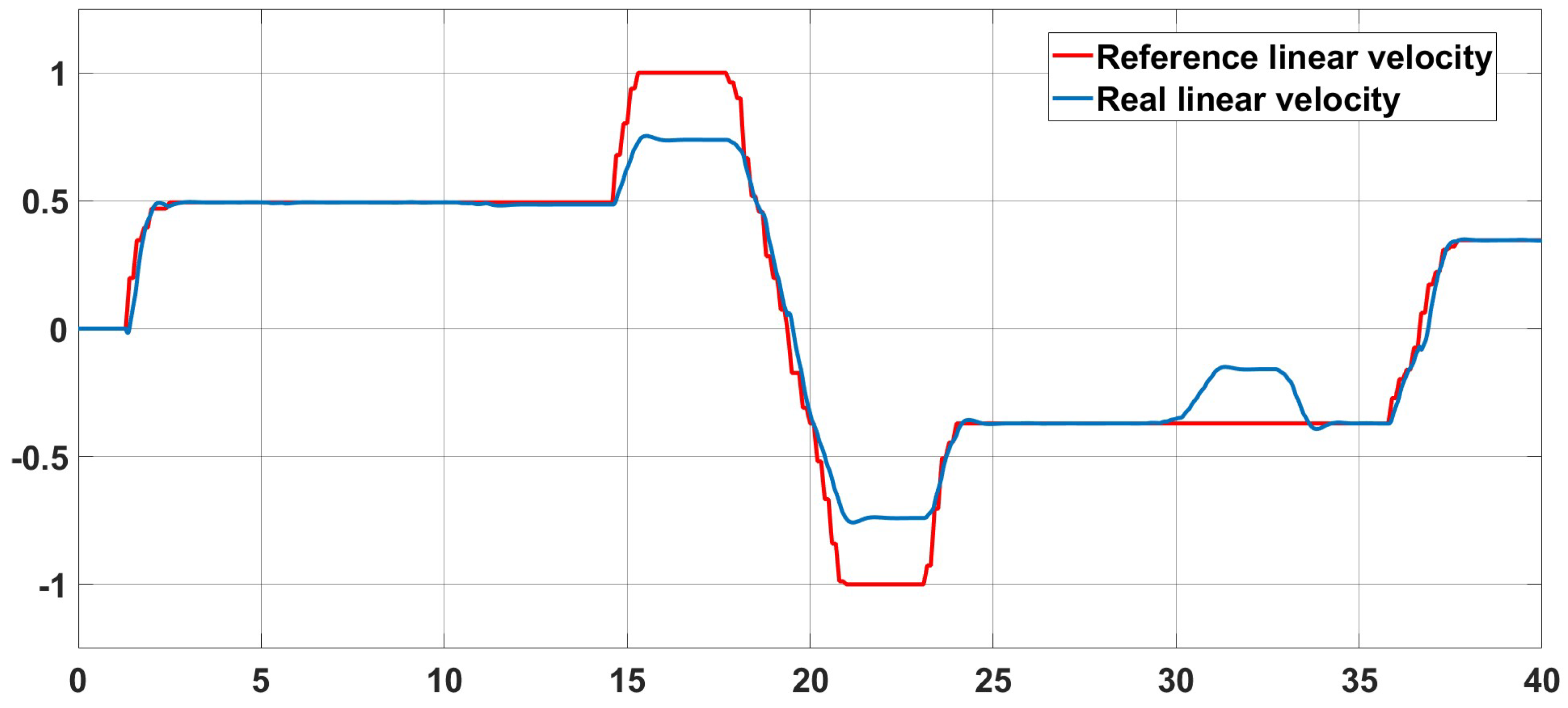

3.3. Implementation of the Navigation System

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baturone, A. Robótica: manipuladores y robots móviles; Marcombo, 2005; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Raj, R.; Kos, A. A Comprehensive Study of Mobile Robot: History, Developments, Applications, and Future Research Perspectives. Applied Sciences 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VALENCIA V., J.A.; MONTOYA O., A.; RIOS, L.H. MODELO CINEMÁTICO DE UN ROBOT MÓVIL TIPO DIFERENCIAL Y NAVEGACIÓN A PARTIR DE LA ESTIMACIÓN ODOMÉTRICA. Scientia Et Technica 2009.

- Feng, S.; Liu, Y.; Pressgrove, I.; Ben-Tzvi, P. Autonomous Alignment and Docking Control for a Self-Reconfigurable Modular Mobile Robotic System. Robotics 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Jia, Y.; Matsuno, F. Tracking control for differential-drive mobile robots with diamond-shaped input constraints. IEEE Transactions on Control Systems Technology 2014, 22, 1999–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, C.D.; Palma, D.D.; Parlangeli, G. Online Odometry Calibration for Differential Drive Mobile Robots in Low Traction Conditions with Slippage. Robotics 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouvakas, N.D.; Koumboulis, F.N.; Sigalas, J. A Two Stage Nonlinear I/O Decoupling and Partially Wireless Controller for Differential Drive Mobile Robots. Robotics 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S. Feedback control design of differential-drive wheeled mobile robots. In Proceedings of the ICAR ’05. Proceedings., 12th International Conference on Advanced Robotics, 2005., 2005, pp. 135–140. [CrossRef]

- Sotelo Gomez, A.A. Implementación de un robot explorador con realidad virtual para incrementar la seguridad de la Institución Educativa 7213 Peruano Japonés en el distrito de Villa El Salvador–2020. Licenciatura thesis, Universidad Privada del Norte, 2020.

- Martinez, J.; Mandow, A.; Morales, J.; Garcia-Cerezo, A.; Pedraza, S. Kinematic modelling of tracked vehicles by experimental identification. In Proceedings of the 2004 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS) (IEEE Cat. No.04CH37566), 2004, Vol. 2, pp. 1487–1492 vol.2. [CrossRef]

- moosavian, S.A.A.; Kalantari, A. Experimental Slip Estimation for Exact Kinematics Modelling and Control of a Tracked Mobile Robot. 2008 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems 2008. [CrossRef]

- Iossaqui, J.G.; Camino, J.F.; Zampieri, D.E. A nonlinear control design for tracked robots with longitudinal slip. In Proceedings of the IFAC Proceedings Volumes (IFAC-PapersOnline). IFAC Secretariat, 2011, Vol. 44, pp. 5932–5937. [CrossRef]

- Choset, H.; Lynch, K.M.; Hutchinson, S.; Kantor, G.A.; Burgard, W. Configuration Space. In Principles of Robot Motion: Theory, Algorithms, and Implementations; MIT Press, 2005; pp. 47–68. [Google Scholar]

- Spong, M.W.; Hutchinson, S.; Vidyasagar, M. DYMAMICS AND MOTION PLANNING. In Robot Modeling and Control, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, 2020; Vol. 1, pp. 165–214. [Google Scholar]

- Du, K.L.; Swamy, M.N.S. Wireless Communication Systems. Conference Record of 2004 Annual Pulp and Paper Industry Technical Conference (IEEE Cat. No.04CH37523) 2010, pp. 94–101. [CrossRef]

- Blanco Abia, C. Desarrollo de un sistema de navegación para un robot móvil. PhD thesis, Universidad de Valladolid, Escuela de Ingenierías Industriales, 2014.

- Nasirian, A.; Khanesar, M.A. Sliding mode fuzzy rule base bilateral teleoperation control of 2-DOF SCARA system. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Automatic Control and Dynamic Optimization Techniques (ICACDOT), 2016, pp. 7–12. [CrossRef]

- Lee, C. Fuzzy logic in control systems: fuzzy logic controller. I. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics 1990, 20, 404–418. [CrossRef]

- Chapman, S. Motores y generadores de corriente directa. In Máquinas Eléctricas, 5 ed.; Mc Graw Hill, 2012; pp. 345–413. [Google Scholar]

- Nise, N.S. MODELING IN THE FREQUENCY DOMAIN. In Control Systems Engineering, 8 ed.; John Wiley & Sons, 2020; pp. 33–115. [Google Scholar]

- Stefek, A.; van Pham, T.; Krivanek, V.; Pham, K.L. Energy comparison of controllers used for a differential drive wheeled mobile robot. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 170915–170927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahayu, E.S.; Ma’arif, A.; Cakan, A. Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) Tuning of PID Control on DC Motor. International Journal of Robotics and Control Systems 2022, 2, 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nise, N.S. Controller Design. In Control Systems Engineering, 8 ed.; John Wiley & Sons, 2020; pp. 455–721. [Google Scholar]

- Ogata, K. Diseño de controladores. In Ingeniería de control moderna, 5 ed.; Pearson Educación, 2010; pp. 416–745. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C. Fuzzy logic in control systems: fuzzy logic controller. I. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics 1990, 20, 404–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra-García, J.E.; Santos, M. Redes neuronales y aprendizaje por refuerzo en el control de turbinas eólicas. Revista Iberoamericana de Automática e Informática industrial 2021, 18, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlucho, I.; Paula, M.D.; Acosta, G.G. Double Q-PID algorithm for mobile robot control. Expert Systems with Applications 2019, 137, 292–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bârsan, A. Position Control of a Mobile Robot through PID Controller. Acta Universitatis Cibiniensis. Technical Series 2019, 71, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padhy, P.K.; Sasaki, T.; Nakamura, S.; Hashimoto, H. Modeling and position control of mobile robot. In Proceedings of the 2010 11th IEEE International Workshop on Advanced Motion Control (AMC). IEEE, 3 2010, pp. 100–105. [CrossRef]

- MSajnekar, D.; scholar Ycce.; Road, H. Comparison of Pole Placement & Pole Zero Cancellation Method for Tuning PID Controller of A Digital Excitation Control System. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications 2013, 3.

- Kim, K.; Schaefer, R. Tuning a PID controller for a digital excitation control system. In Proceedings of the Conference Record of 2004 Annual Pulp and Paper Industry Technical Conference (IEEE Cat. No.04CH37523). IEEE, 2004, pp. 94–101. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Cui, Y.; Ding, X. An improved analytical tuning rule of a robust pid controller for integrating systems with time delay based on the multiple dominant pole-placement method. Symmetry 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Vrancic, D.; Hanus, R. Anti-windup, bumpless, and conditioned transfer techniques for PID controllers. IEEE Control Systems 1996, 16, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohn, C.; Atherton, D.P. An analysis package comparing PID anti-windup strategies. IEEE Control Systems 1995, 15, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gün, A. Attitude control of a quadrotor using PID controller based on differential evolution algorithm. Expert Systems with Applications 2023, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousakazemi, S.M.H.; Ayoobian, N. Robust tuned PID controller with PSO based on two-point kinetic model and adaptive disturbance rejection for a PWR-type reactor. Progress in Nuclear Energy 2019, 111, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosaad, A.M.; Attia, M.A.; Abdelaziz, A.Y. Whale optimization algorithm to tune PID and PIDA controllers on AVR system. Ain Shams Engineering Journal 2019, 10, 755–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, W.; Liu, X.; Jia, G.; Zhang, C.; Sun, B. Research on the Prediction Model of Engine Output Torque and Real-Time Estimation of the Road Rolling Resistance Coefficient in Tracked Vehicles. Sensors 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FunctionBay, I. Discrete Time Integrator, n.d. Accessed: 2024-07-10.

| Variable | Valor |

|---|---|

| Distance between wheels (L) | 0.650048 m |

| Track sprocket radius (r) | 0.07286 m |

| Number of motor output teeth (N1) | 18 |

| Number of teeth of the track sprocket (N2) | 27 |

| Mass of the structure | 6.949 kg |

| Track mass | 5.435 kg |

| Wheel mass | 3.589 kg |

| Front sprocket mass | 2.898 kg |

| Rear sprocket mass | 2.36 kg |

| Casing mass | 6.464 kg |

| Other components | 13.667 kg |

| Robot inertia () | 15.3 kg· m2 |

| Maximum angular velocity of motor () | 321.6 rad/s |

| Maximum motor torque () | 1.1333 Nm |

| Gearbox motor transmission ratio () | 1/15 |

| Motor supply voltage | 24 V |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Maximum linear speed of the robot (V) | 1.03396 m/s |

| Maximum angular velocity of the robot () | 3.18119 rad/s |

| Maximum angular acceleration of the motors () | 1000 rad/s2 |

| Parameter | Unit |

|---|---|

| KT | 0.1039 Nm/A |

| Kb | 0.0694 V· s/rad |

| Im | 0.000512 kg· m2 |

| b | 0.000251 Nm · s /rad |

| La | 0.153063 H |

| Ra | 2.2 |

| Parameter | Unit |

|---|---|

| KT | 0.1086 Nm/A |

| Kb | 0.0694 V· s/rad |

| Im | 0.000542 kg· m2 |

| b | 0.000272 Nm · s /rad |

| La | 0.164792 H |

| Ra | 2.3 |

| Parameter | Right motor | Left motor |

| kp | 0.149347 | 0.158561 |

| 0.067278 | 0.069166 | |

| 0.150127 | 0.158682 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).