3.3. Disc Tears

Even at early stages of degeneration, the structural changes to the annulus will include internal disc disruption such as radial fissures and circumferential tears. Annular tears are found in 50% of lumbar discs under 35 years of age [

9] and 100% of L4-L5 discs in the 10-30 year age group [

10]. Circumferential tears, which are comprised primarily of delamination of adjacent lamellae [

11] are the most common and the first to appear 9-11]. Schwartzer [

12] found that 39% of low back pain patients had internal disc disruptions observed on CT discograms. Other early structural changes include inward buckling of the inner annulus, increased radial bulging of the outer annulus, reduced disc height, rim lesions, and endplate defects.

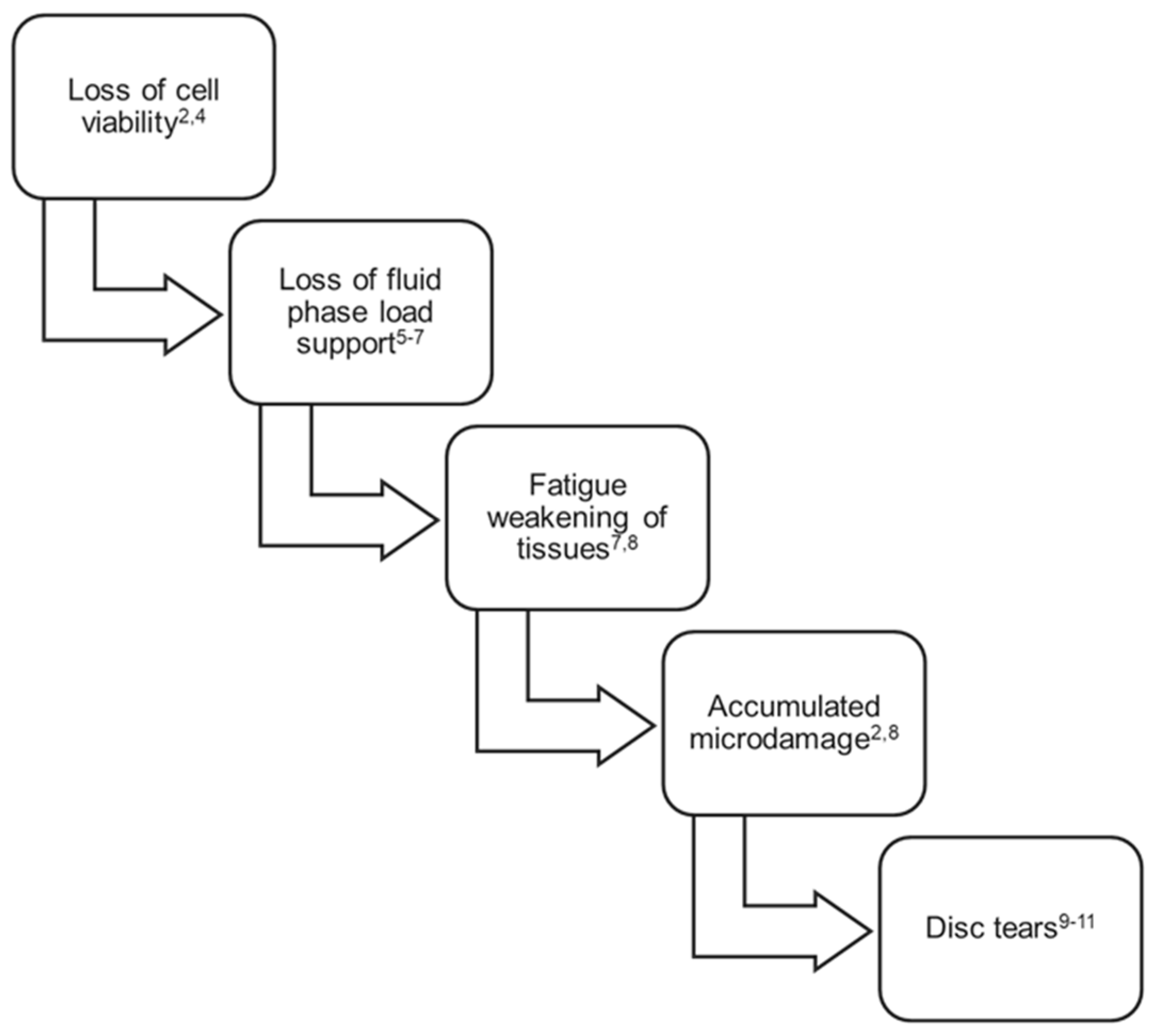

Figure 1 summarizes the factors known to contribute to early-stage lumbar disc degradation and the corresponding loss of load support and motion constraint.

It is noteworthy that while some disc tears and the initial loss of fluid phase load support may be detectable in vivo using MRI, accumulated microdamage, tissue compositional changes, and fatigue weakening of disc tissue cannot be detected, much less quantified, using current imaging technologies including dynamic imaging techniques. While undetectable, these changes may be clinically consequential and should be understood as possible causal links between this known progressive degradation and patient recurrent or chronic pain and disability at early stages of the disorder.

Figure 1.

Factors contributing to disc degradation and mechanical insufficiency, first 3 decades of life.

Figure 1.

Factors contributing to disc degradation and mechanical insufficiency, first 3 decades of life.

3.4. Segmental Degenerative Instability

Because of the biomechanical role of the lumbar annulus fibrosus, accumulated microdamage of the annulus will directly affect disc mechanical function leading to increased tissue deformation, such as radial bulging under load, and a reduction in passive tissue constraint of joint motion [

13,

14]. Momentarily setting aside the increased disc bulging under normal physiological loading associated with mechanically degraded discs, segmental instability is a focal point in management of low back pain. To fully appreciate the relationship between progressive disc degradation and segmental instability, it is best to look at instability as a progressive three-dimensional motion and deformation disorder that is not limited to a classical, dichotomous, translational or rotational motion that surpasses a clinically determined limit. Clinical translational or rotational indicators of segmental instability are useful for standardizing and simplifying clinical decision making. However, behind these clinically useful limits, segmental degenerative instability is the degradation-related progressive motion disorder where tissue mechanical degradation causes a gradual loss of segmental constraint and load support. Like the core tissue degradation, degenerative segmental instability begins in the early decades of life and progresses thereafter. Loss of segmental constraint results in aberrant motions and deformations which could in turn elicit discogenic pain. A common metric used to assess joint instability is the neutral zone [

15]. This characteristic has been directly correlated with incidence of low back pain [

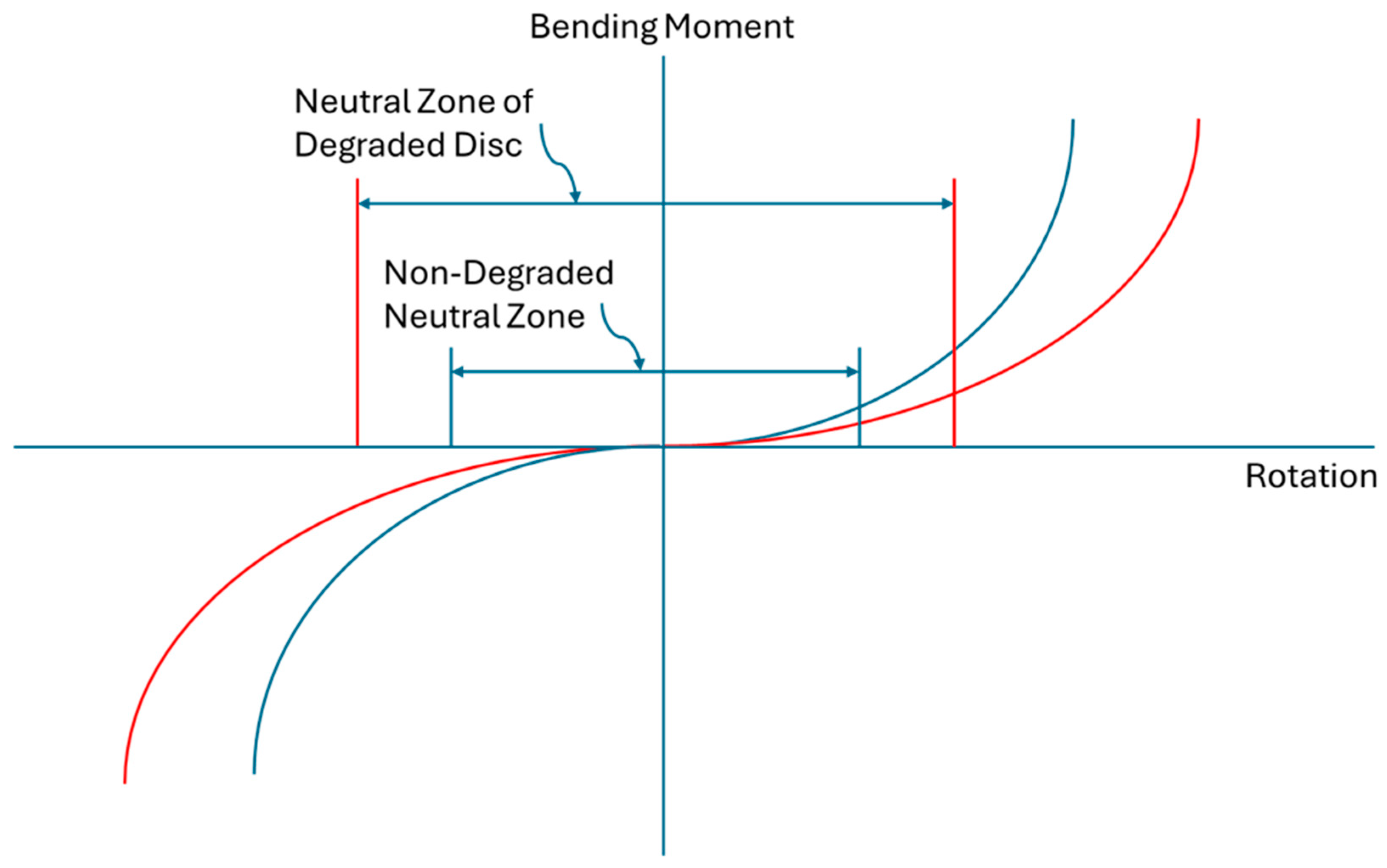

16]. As one of many possible examples of the progressive nature of this disorder, degenerative segmental instability could entail a gradual increase in neutral zone size due to a progressive reduction of passive joint constraint (

Figure 2). Another example would include tissue mechanical insufficiency reducing joint constraint that gradually increases translational slip when bending, eventually becoming a fixed anterior translation or spondylolisthesis. Another example would be the gradual increase in joint angulation under flexion loading due to a reduction of stiffness and load support in the degraded disc. Therefore, the loss of lumbar intervertebral joint constraint due to degradation of annulus tissues can be mechanistically linked to discogenic pain. The point at which this progressive segmental instability begins to contribute to episodes of low back pain, if that occurs, is likely to be different from individual to individual.

Increased lumbar disc bulge under load is sometimes referred to as vertical instability. Whether by acute events or a result of the progressive disc degradation described here, increased disc bulge due to insufficiency of the degraded disc [

17] has been shown to have a bulge magnitude [

18] that is three times the displacement required to elicit a neural response in mechano-nociceptive nerve fibers of the type found in the intervertebral disc [

19,

20,

21,

22]. Consequently, increased disc bulge resulting from loss of axial compressive load support due to degradation of annulus tissues can be mechanistically linked to discogenic pain.

3.5. Pathomechanics and Low Back Pain

Because this growing mechanical insufficiency begins early in life and the disc annulus is the primary anatomical structure providing load support and motion constraint in intervertebral joints [

23,

24], it follows that the early degradation of annulus tissue can be a primary contributor in the etiology of lumbar joint tissue failures and pain, both early-stage and later-stage. Despite the primary role of the annulus in lumbar joint mechanics, the majority of historical and emerging intradiscal treatment approaches have been directed to the nucleus pulposus region of the disc. The reasons for this are not clear but may lie in an incorrect assumption that nucleus degradation precedes annulus mechanical degradation. This assumption may be in part due to degradation detectability. Nucleus changes can be more readily observed by magnetic resonance imaging due to the loss of water content compared to changes in mechanical integrity of the fibrous, load carrying annulus. There may also be a sense that just as a flat tire needs to be reinflated to support a vehicle’s weight and function properly, addressing the loss of nucleus volume may enable the disc to function properly. Using the same analogy, reinflating a degraded and worn-out tire may be short-lived, or it may lead to a more dramatic failure of the tire if the mechanical deficiencies of the solid portions of the tire are not addressed.

It is suggested in this paper that discogenic low back pain experienced in the third and fourth decades of life (ages 20s and 30s) can often be attributed to the accumulated damage to lumbar discs in the first 3 decades of life and the resulting disc pathomechanics associated with this degradation. Psychosocial factors play a role in the chronicity of low back pain, but inadequate biological repair and progressive mechanical insufficiency are the sparks that light the fire. Lumbar disc tissue changes are universally present in the first three decades of life, however they are not always associated with symptoms. While all repair-limited and mechanically degraded discs are not necessarily symptomatic, all persistent low back pain cases have in common disc degradation and the associated mechanical insufficiency of this primary load carrying and motion constraining tissue [

25,

26].

From the early 1990s, tissue degradation and aberrant mechanical stress have been linked to low back pain incidence in several studies. The simple fact that mechanical provocation of discs can reproduce severe and chronic back pain indicates the role that mechanical stress and therefore tissue mechanical insufficiency can play in pain generation [

27,

28,

29,

30]. The outer annulus fibrosus is known to contain nerve endings [

31] that may be responsive to aberrant strains, deformations, and motions.

Consistent with the evidence implicating early-stage mechanical degradation of lumbar discs in the etiology of recurrent and chronic low back pain, several studies demonstrate that the pain and disability associated with this degradation typically begins at the early stages of a person’s adult life and progresses for decades thereafter [

32], during the primary working years of the individuals. Deyo and Tsui-Wu in 1987 [

33] found the peak age of onset of low back pain to be between 20 and 29 years, with new cases declining after age 29. Likewise, Laslett et al. in 1991 [

34] found that nearly 50% of New Zealanders with low back pain suffered their first episode before the age of 30 years. Similarly, Biering-Sorensen in 1983 [

35] when evaluating 1-year follow-up questionnaires of 30, 40, 50, and 60 year-olds found the incidence of first attacks of low back pain was highest in the 30-year-olds and decreased in the older age-groups.

For a variety of reasons, this debilitating disorder is widespread in Western society. Over 80% of the population experiences an episode of LBP at some point in their lifetime [

36], with lifetime recurrence rates up to 85% [

37,

38]. The point prevalence in the adult population of degenerative disc disease is 37% and the 1-year prevalence is 76% [

39], with more than two-thirds of recent onset cases and four-fifths of non-recent onset cases being repetitive (episodic and lasting more than a year) or chronic [

26,

32,

40].

Chronic low back pain (CLBP) is more prevalent in women and increases linearly from the third decade until about age 60 [

41,

42], with 10-12% of the population disabled by CLBP [

6,

42]. As a consequence, degenerative disc associated low back pain is the second most common pain condition resulting in lost work time (first is headache) [

43,

44], with a total annual cost in the US estimated to exceed 100 billion dollars [

45].

3.7. Preferred Treatment Characteristics

With the advent of more refined imaging techniques and methods of diagnosing discogenic low back pain, the diagnosis of “discogenic, recurrent low back pain” is beginning to replace the previously common identifier of “non-specific low back pain”. Arguably, the term “non-specific low back pain” wrongly suggests that a likely reason for the pain cannot be determined, when the universal and not insignificant degree of lumbar disc mechanical degradation is well known as described in this review. The fact that disc mechanical degradation is not always associated with pain does not take away from the associations of progressive mechanical degradation with aberrant motions and deformations known to be causative in discogenic pain through several known pathways.

Considering that early stage discogenic pain and disability stems from core mechanical deficiencies, appropriate interventions will be directed to ameliorate the mechanical degradation both to address current pain and disability and with the intent to intercept the progressive cascade of degradation leading to increasing tissue degradation and worsening symptoms. Therefore, a successful intervention will act to restabilize the affected segment and add load support where it has been lost to fatigue weakening, loss of fluid phase load support, and accumulated microdamage. Preferably this added motion constraint and load support will not alter or interfere with the mechanical loading patterns inherent in the disc tissues as this could potentially contribute to additional degradation and loss of the mechanical attributes of the tissues. Ideally, the added mechanical support and constraint are immediately effective rather than requiring the passage of several weeks or the cumulative effects of multiple administrations.

Palliative treatments including epidural steroid injections, opioid and non-opioid analgesics, and nerve ablations are perhaps contraindicated in early-stage disc degradation related pain and disability cases. Pain-masking could be detrimental to already mechanically insufficient tissues due to a corresponding absence of pain-avoidance constraints on movements while undergoing daily activities leading to a greater frequency of deleterious loading events.

Demonstrations of joint re-stabilization and augmentation of disc mechanical load support are therefore important indicators of a potentially appropriate intervention. Considering the progressive nature of this disorder, the ability to restabilize degraded lumbar joints and increase disc annulus strength and other mechanical properties following the intervention are perhaps as important as demonstrations of rapid and long-term reductions of pain and disability. To that end, mechanical benefits in both tissue strengthening and motion constraint can be most clearly evaluated and quantified by in vitro cadaveric tissue studies, or for interventions which rely on a biological response, from ex vivo experiments. Mechanical benefits demonstrated in cadaver experiments or from tissues harvested following in vivo animal administration would ultimately need to be confirmed in human clinical studies, with the understanding that confirmation of mechanical changes resulting directly from an intervention may have to rely exclusively on changes in patient kinematics following the treatment compared to baseline characteristics.

Protection of disc tissues and adjacent musculoskeletal tissues by the use of non-destructive microinvasive methods is essential for an intervention at the early stages of this chronic and progressive disorder. Preservation of tissue anatomy and avoidance of treatment adverse effects that could potentially be detrimental to the disc or adjacent tissues are vitally important at this early stage. The common motto is to “not burn any bridges”. With tissues already showing symptomatic mechanical insufficiency, the intervention should be strictly beneficial mechanically, especially in the essentially avascular intervertebral disc tissues which have very limited capacity for healing or regeneration.

Durability of treatment effect is another important consideration in the success of interventions for early-stage disc degradation related pain and disability. Permanent, non-degrading mechanical support for the degraded disc is the ideal remedy. Patient compliance is typically at odds with the need for repeated treatments, therefore the less frequently that a restabilizing treatment would have to be administered to be effective, the better.

Healthcare and societal cost considerations are also paramount. Expensive interventions face an uphill battle for reimbursement by the insurance industry and those making decisions regarding public healthcare cost coverages. Cost benefits for treatments that reduce the likelihood of follow-on procedures and expensive surgeries may only be fully calculable after long-term cost and effectiveness studies. Conversely, early-stage and durable treatments that reduce the cost for care (relative to traditional joint fusions, decompression, and disc replacement surgeries), or the need for ongoing visits to a health care provider, could provide a vital treatment option to marginalized and economically challenged groups as well as providing a global treatment option for those countries or regions that don’t have ready access to more invasive solutions. Another consideration is the accessibility of the treatment to physicians in terms of procedure simplicity, minimal learning curve, and not requiring specialized or advanced equipment.

Lorio et al. [

46] describe intradiscal interventions as filling “the extensive treatment gap between conservative management and traditional spine surgery”. Considering the early onset of recurrent discogenic pain described above, this treatment gap often involves one to four decades of pain, disability, and loss of workdays prior to patients and providers accepting the suitability of an expensive and higher risk spinal surgery.

Even after a new technology has demonstrated the ability to address early-stage disc degradation related pain and the ability to resist the progression of degradation of the disc and surrounding load supporting tissues, improved clinical care for this widespread disorder will require adoption by all the medical care stakeholders including frontline clinicians (primarily general practitioners), spine interventionalists and surgeons, clinical practices and hospitals, and medical insurance providers. Beyond filling a treatment gap in the current continuum of care, a successful early-stage discogenic back pain intervention that addresses and ameliorates the mechanical degradation at the center of this disorder would potentially reduce the need for traditional spine surgery at the later stages of the treatment continuum. With one component of potential healthcare cost savings coming from the prevention of progressive lumbar tissue deterioration, cost advantages will only be fully demonstrated with long-term and large clinical studies with real-world patients to quantify the reduction of post-intervention costs associated with repeated visits to healthcare providers, increasing severity of the disorder (progression to disc herniation, radicular pain, spinal stenosis, spondylolisthesis, etc.) and avoidance of expensive surgeries. In addition to these follow-on healthcare costs, the cost reduction of fewer workdays lost to recurrent back pain, during what would otherwise be a treatment gap period, should also be carefully evaluated. One medical insurance related hindrance to obtaining the data to propel a significant change in patient care, a “catch-22” of sorts, is that novel treatments typically have to demonstrate cost savings and effectiveness before long-term and large studies of this type are financially feasible.

With the emergence of intradiscal interventions that are capable of re-stabilization and mechanical load support of degraded lumbar discs, it is expected that there will need to be a paradigm shift in the continuum of care for this disorder, from a reliance on conservative care followed by “watchful waiting”, physical therapy, nerve blocks, and other palliative care standard treatments, placing the new therapeutic as the preferred approach at the early stage of treatments.

3.8. Existing and Emerging Intradiscal Treatments

Until recently, virtually all treatment guidelines for the management of chronic “nonspecific” low back pain could not recommend intradiscal injections until supporting high quality randomized controlled trial data is available [

47]. Intradiscal treatments are increasingly used today for recurrent and chronic discogenic low back pain, but spine health societies and payers are still reticent to give their full recommendation for any of these procedures. Quality randomized controlled trial data is indeed an appropriate standard. Notably, the current standard treatments (or non-treatment) set a low bar for treatment superiority when patient reported outcomes, costs and frequency of repeated physician visits and follow-on procedures, use of analgesic medicines, and reducing work time lost are all included in the assessment.

The recent paper by Lorio et al. (2024) [

46] is referenced here as a relatively comprehensive listing of the current state of the art regarding intradiscal injections in the treatment of discogenic pain. Most of the candidate therapies listed in this paper are biologic in nature: mesenchymal stromal cells, platelet-rich plasma, nucleus pulposus structural allograft, and other cell-based compositions. The disadvantages of biological approaches include clinical success often turning out to be patient-specific with distinctly different outcomes for “responders” and “non-responders”, the treatments can be costly or require more than one procedure to initiate the repair, and biological treatments by their nature generally require several weeks to demonstrate an effect.

Lorio et al. describe the “overriding challenge” for biological agents to provide a durable restorative effect lies in the harsh biological conditions of the lumbar intervertebral disc as discussed earlier in this review. One might question whether it is a rational choice to attempt to employ a cell-based or other biological therapeutic in a nutritionally deficient tissue

4 that has been declining in cell viability since birth [

2]. After more than two decades and an immense worldwide research investment in both funding and human capital, the sage advice provided by Urban, et al. [

4] continues to ring true: “New methods of disc repair involving stimulation of native cells or insertion of new cells or tissue-engineered disc should, however, be used with caution in humans. For successful disc repair, the newly inserted or stimulated cells have to exist in conditions where they remain viable and active. It is thus essential that the nutrient supply to the disc is adequate and, moreover, that it can support the increased nutritional demands these methods induce; the disc will need more nutrients to support inserted cells or cells for which the activity has been increased.” Urban et al. continues, “it is unrealistic to expect that reimplantation of cells into such discs would effect a repair. Before cell based therapies can be introduced successfully, some method of selecting suitable patients on the basis of an adequate nutrient supply to the affected disc appears absolutely crucial.”

Similarly, Lorio et al., some twenty years later, describe the requirements for durable clinical success for biological agents, including: the ability to remain viable in the degenerated disc long enough to contribute to matrix production, ability to generate adequate paracrine signaling to alter the behavior of native cells, support the recruitment of regenerative cell types or limit infiltration of fibrotic/catabolic cells, and provide intradiscal mechanical support – aligning with the theme of this article.

Other emerging intradiscal approaches referenced in Lorio et al. include Discseel, which uses allogeneic fibrin, Hydrafil, a polymer composite hydrogel augmentation material, and Discure, a multi-electrode implanted catheter that provides intradiscal electrical stimulation in an attempt to increase the osmotic gradient and induce increased hydration in the degraded disc.

It is well known that fibrin is one component of blood clots, but fibrin clots are unstable and breakdown without the crosslinking component transglutaminase, an enzyme that catalyzes the crosslinking of proteins by forming covalent bonds between lysine and glutamine residues in various polypeptides. Factor XIII-A is the active transglutaminase that plays a crucial role in the coagulation cascade. While tissue sealing effects including forming a physical barrier to resist migration of catabolic agents may occur in the short term after intradiscal delivery of fibrin, it is debatable that these effects would endure long enough to be consequential clinically without adequate transglutaminase-catalyzed covalent crosslinking to make this sealant stable and more resistant to breakdown. Longer-term effects such as resisting neoinnervation into the degraded annular fibers are unlikely to occur without a stable sealant construct which fibrin alone does not provide.

The Hydrafil composite hydrogel augmentation material (PVA/PEG/PVP/ barium sulfate) attempts to remedy the mechanical insufficiency of the disc by providing compressive load-carrying implant material to the degraded disc. The hydrogel also has a high hydrophilicity to draw in and retain interstitial water in the disc. Hydrafil has demonstrated improvements in back pain and disability in early studies with no persistently symptomatic serious adverse events [

48]. The hydrogel is injected as a relatively high-temperature liquid (65 °C) into the nucleus pulposus tissue using a relatively large needle (17Ga) with the intention to also flow into the annulus region of the disc. After it cools to body temperature, the hydrogel acts as a bulk-filler, a compressive-load carrying intradiscal solid material. It may be important to note the contrast between the mechanisms of load support between the disc annulus collagen matrix and the bulk filler. Collagen molecules and fibers in the disc annulus resist tensile stresses while a bulk filler resists compressive forces. It is not known how these contrasting mechanisms of load support by adjacent materials (native tissue and implant material) may affect the long-term integrity of the disc tissues. Also, in order to not displace or disrupt disc tissues, these fillers require gaps within the disc which is generally limited or not available in early to mid-stage degenerated discs. While it may have been initially intended for early-stage disc degeneration cases, Hydrafil is directed toward more severely degenerated discs (moderate to severe, Modified Pfirrmann Levels III-VI) that can accommodate the addition of a bulk material. Additional concerns include the potential for disc tissue damage in proximity to the implant material when it is injected as a hot liquid. Collagen can begin to denature at temperatures above 60 °C and cell death is likely to occur at those temperatures. The depth of tissue damage and cell death from contacting the temporarily hot liquid is not known and may be insignificant. The relatively large diameter needles used in this procedure may lead to implant material expulsion, as well as causing “drastic alteration” of annulus strain behavior leading to disc degeneration [

49,

50]. Initial clinical results showed relatively high rates of implant displacement or extrusion (15%) and serious adverse events (25%) [

48] by 6-months.

Discure, an implanted multi-electrode catheter, provides intradiscal electrical stimulation in an attempt to increase the osmotic gradient and induce increased hydration and potentially annular regeneration [

51] in the degraded disc. The multi-electrode catheter is connected to an implanted pulse generator to provide electrical stimulation in the degraded disc. A pre-clinical organ culture experiment using porcine intervertebral discs demonstrated several markers consistent with annular regeneration including an increase of anti-inflammatory cytokines and decrease in pro-inflammatory markers. Whether these effects can be consistently achieved with lasting effects in clinical settings has yet to be demonstrated.

Hedman et al. 2024 [

52] recently discussed the capabilities of Intralink, an injectable, self-polymerizing nano-tether mesh, in the treatment of lumbar disc degradation and the associated pain and disability. The intra-annular mesh is comprised of a large number of genipin tensile load carrying oligomers (relatively short monomers) that diffuse through the annulus tissue and covalently bond to amines on collagen. Unlike the compressive load support of bulk fillers in the disc (i.e. Hydrofil), Intralink adds a mesh of tensile load-carrying polymers that attach directly to the collagen and help to support the degraded, tensile load-carrying fibrous collagen in the annulus.

Intralink treated cadaveric disc experiments have quantified the mechanical effects of the intra-annular polymeric mesh including reduction of disc bulge under load, increasing resistance to annulus shear and delamination, increasing tissue tensile strength, and increasing intervertebral joint stability [

52]. The results from these

in vitro disc studies have begun to be replicated and confirmed in early clinical studies of the device, including demonstrations of immediate (1 to 2 weeks) and lasting (up to 2 years post-treatment) reductions of pain and disability coupled with kinematic data showing an increase in segmental stability, especially in painful joints with segmental instability, assessed pre-treatment, that were more than 1.5 standard deviations above the asymptomatic mean. These data suggest that the intra-annular polymeric mesh can be expected to provide durable motion constraint and load support when added to the degraded disc annulus tissues, and that addressing the core mechanical insufficiencies of degraded lumbar discs can result in immediate and lasting reductions of pain and disability. The early clinical data suggests an absence of serious adverse events in the use of this injectable treatment. Additional clinical evidence from larger clinical studies and randomized controlled trials is needed to establish the stage of disc degradation that is best suited to be treated using this technology.