Submitted:

14 March 2025

Posted:

14 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Establishment of Mouse Heat Stress Model

2.2. Detection of mRNA Expression Levels of Heat Shock Proteins, Marker of Intestinal Stress, Integrity and Inflammatory

2.3. Sampling and Isolation of Intestinal Tissues and Bacteria

2.4. Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations (MICs) of Enterococcus Strains

2.5. The Evaluation of the Genetic Variation of Enterococcus Species by Enterobacterial Repetitive Intergenic Consensus Sequence PCR (Eric-PCR)

2.6. Whole Genome Sequencing, Amplification Analysis and Antibiotic Resistance Genes (ARGs) Detection

2.7. Transfer Experiments

2.8. Intestinal Colonization with Erythromycin-Resistant Enterococcus and Heat Stress in Mice

2.9. Metagenomic Sequencing and Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Heat Stress on Markers of Intestinal Integrity and Function

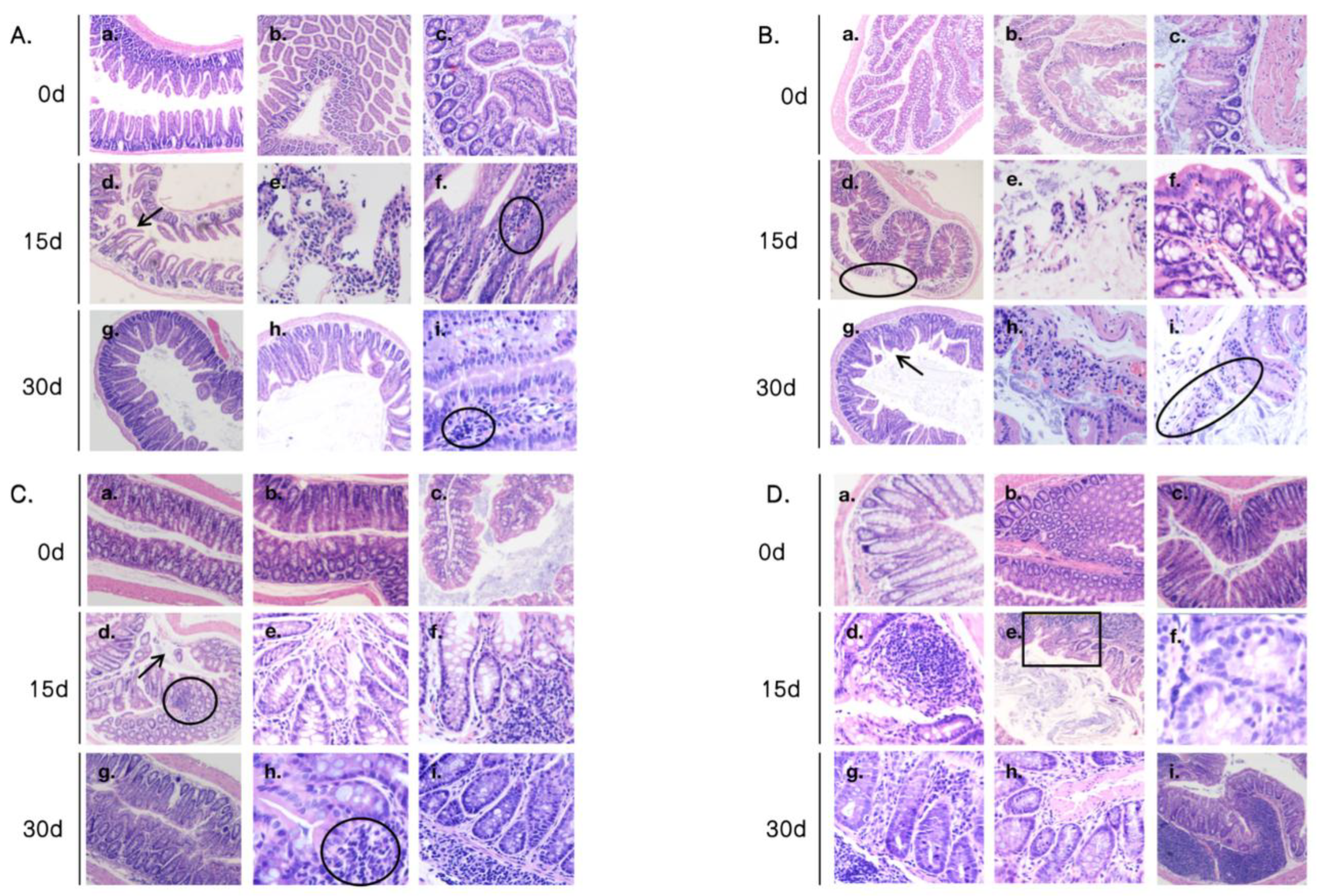

3.2. Intestinal Morphology in Mouse Intestinal Sections Under Heat Stress

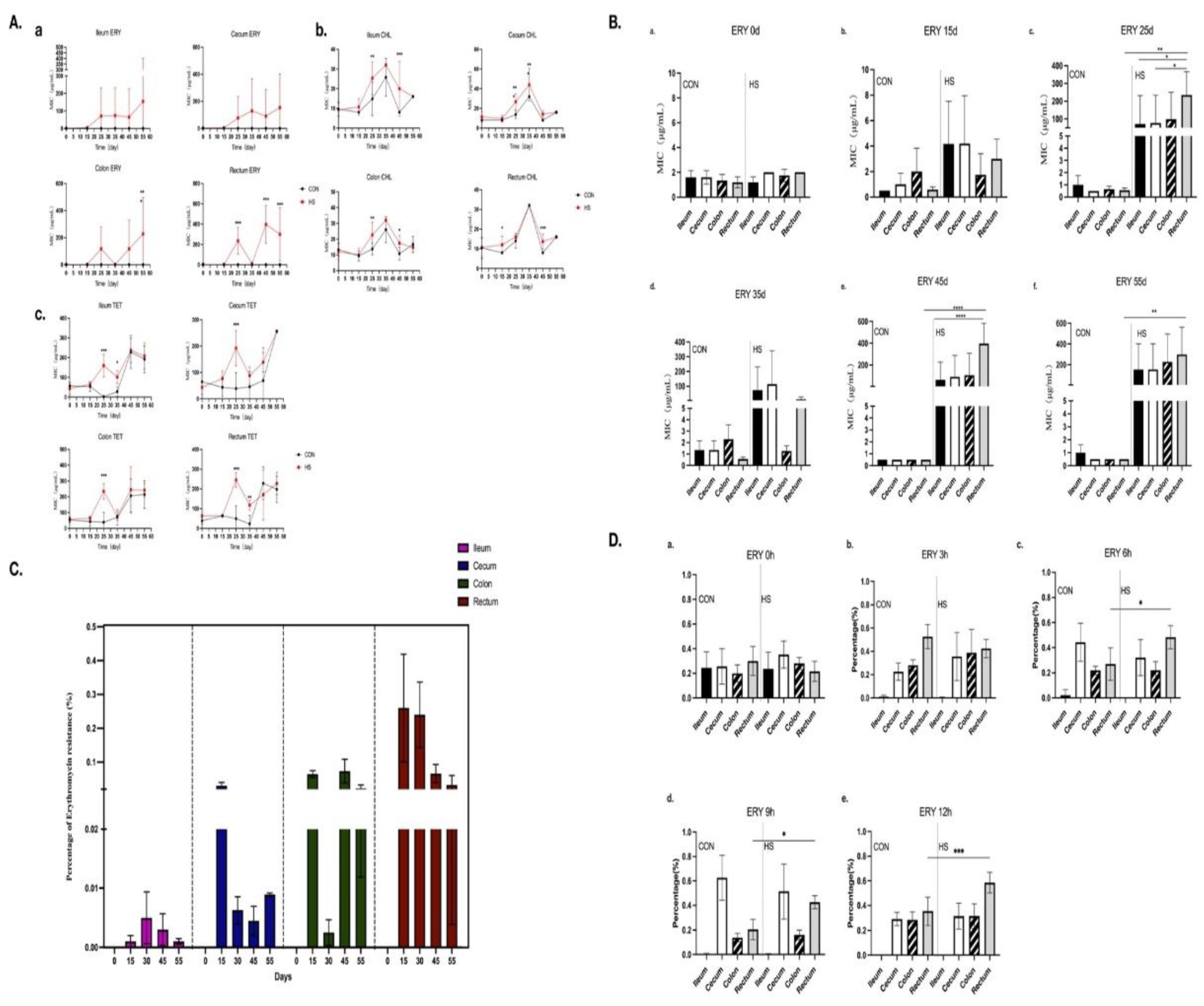

3.3. Determination of MICs for Enterococcus Strains

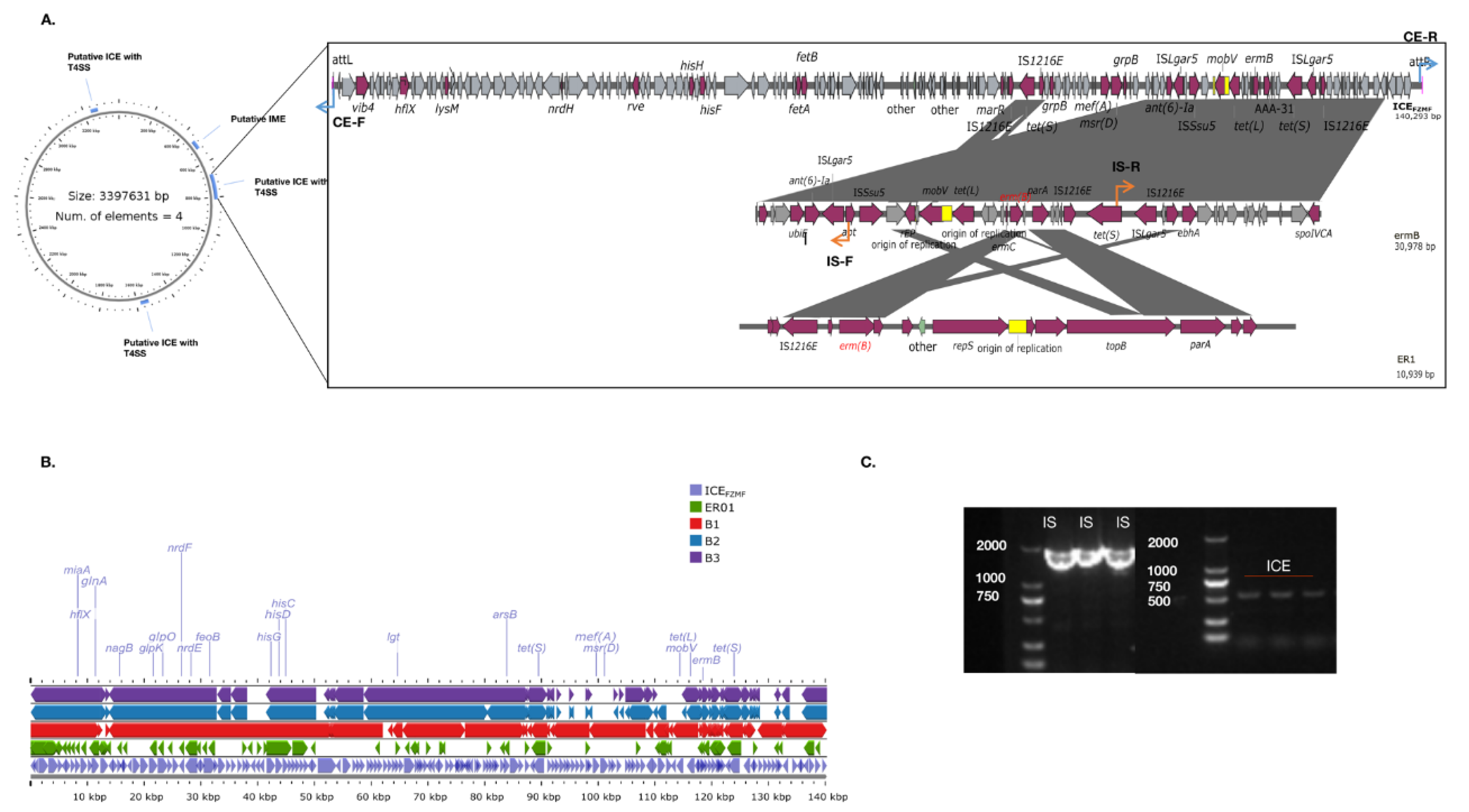

3.4. Antibiotic Resistance Genes (ARGs) Screen and Phylogenetic Analysis

3.5. Characterization of a Novel ICEFZMF and Its Transferability

3.6. Heat Stress Facilitates Enhanced Rectal Colonization of Erythromycin-Resistant Enterococci ER1

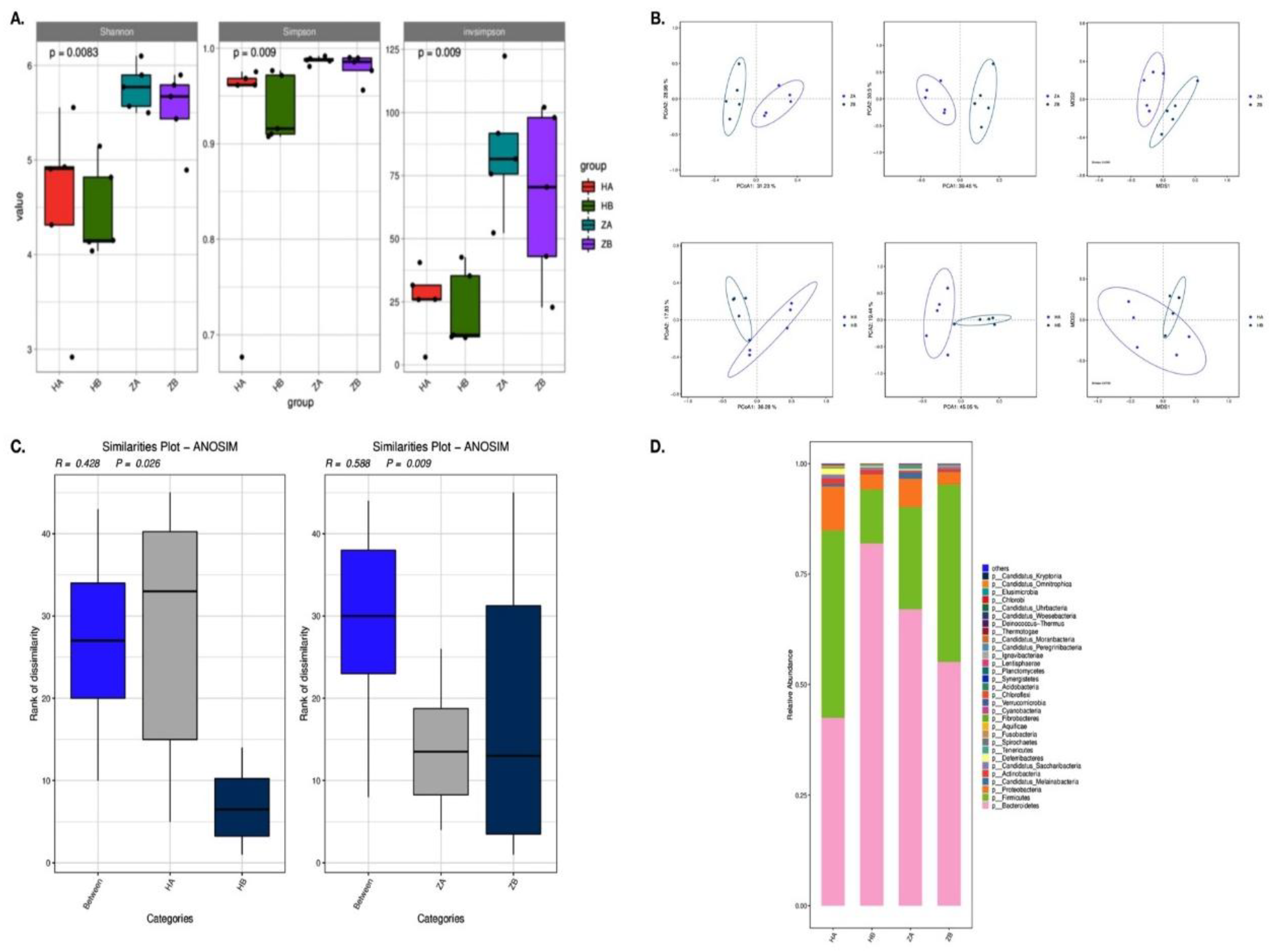

3.7. Effects of Heat Stress on Microbiota Composition in Different Intestinal Segments of Mice

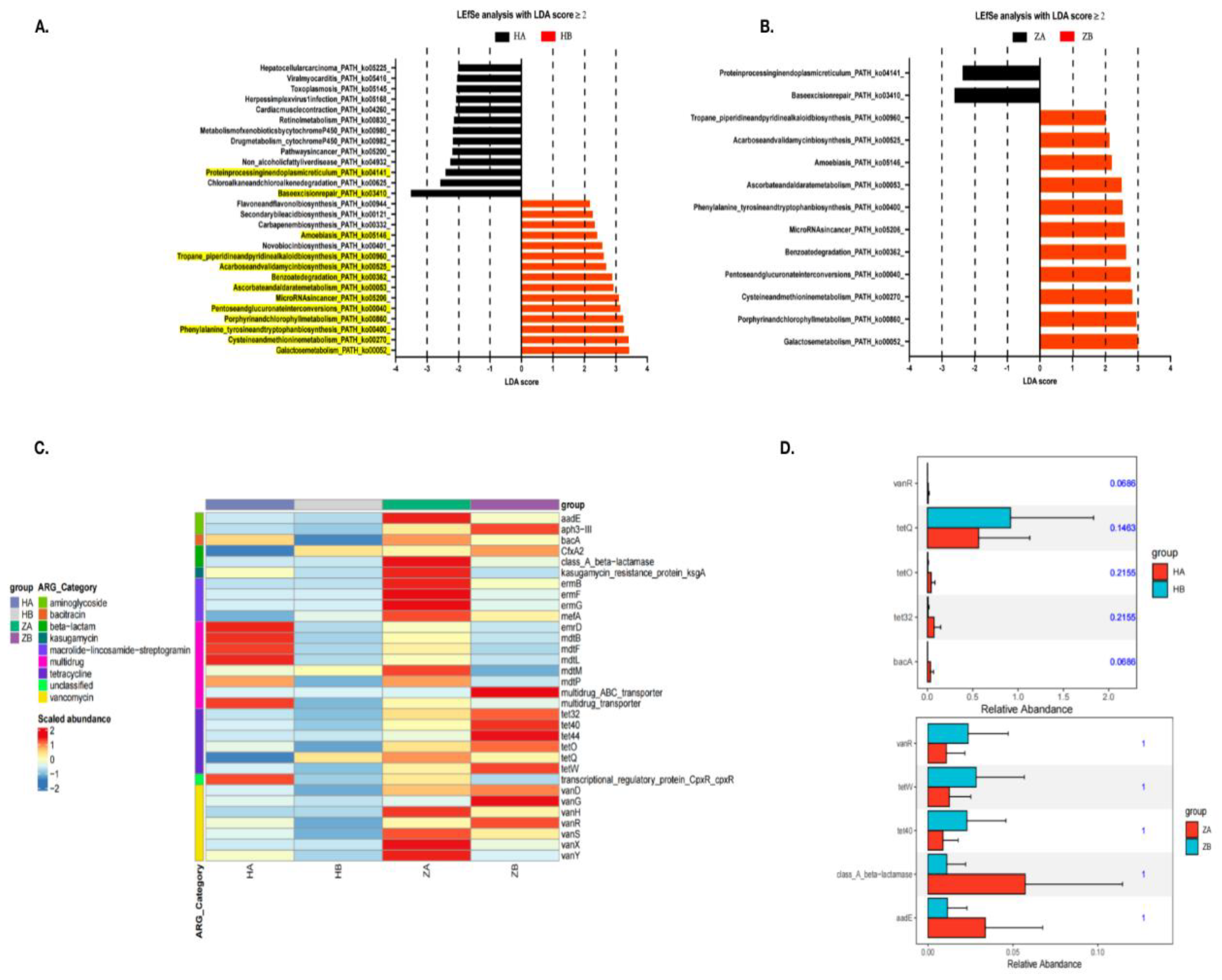

3.8. Metabolic Pathway Alterations in Response to Heat Stress

3.9. Effects of Heat Stress on Antimicrobial Resistance Genes in Gut Microbiota

4. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Data Availability

Conflicts of Interest Statement

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

References

- Hu, H.; Bai, X.; Shah, A.A.; Wen, A.Y.; Hua, J.L.; Che, C.Y.; He, S.J.; Jiang, J.P.; Cai, Z.H.; Dai, S.F. Dietary supplementation with glutamine and gamma-aminobutyric acid improves growth performance and serum parameters in 22- to 35-day-old broilers exposed to hot environment. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl) 2016, 100, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jindal, A.K.; Pandya, K.; Khan, I.D. Antimicrobial resistance: A public health challenge. Med J Armed Forces India 2015, 71, 178–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lane, J.K.; Kelly, T.; Bird, B.; Chenais, E.; Roug, A.; Vidal, G.; Gallardo, R.; Zhou, H.; VanHoy, G.; Smith, W. A One Health Approach to Reducing Livestock Disease Prevalence in Developing Countries: Advances, Challenges, and Prospects. Annu Rev Anim Biosci 2025, 13, 277–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bava, R.; Castagna, F.; Lupia, C.; Poerio, G.; Liguori, G.; Lombardi, R.; Naturale, M.D.; Mercuri, C.; Bulotta, R.M.; Britti, D.; et al. Antimicrobial Resistance in Livestock: A Serious Threat to Public Health. Antibiotics (Basel) 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, S.; Silva, V.; Dapkevicius, M.L.E.; Igrejas, G.; Poeta, P. Enterococci, from Harmless Bacteria to a Pathogen. Microorganisms 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, C.; Alonso, C.A.; Ruiz-Ripa, L.; Leon-Sampedro, R.; Del Campo, R.; Coque, T.M. Antimicrobial Resistance in Enterococcus spp. of animal origin. Microbiol Spectr 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, L.; Beig, M.; Wang, L.; Navidifar, T.; Moradi, S.; Motallebi Tabaei, F.; Teymouri, Z.; Abedi Moghadam, M.; Sedighi, M. Global status of antimicrobial resistance in clinical Enterococcus faecalis isolates: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 2024, 23, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Zhang, S.; Shang, X.; Wang, X.; Yan, Z.; Li, H.; Li, J. Short communication: Antimicrobial resistance and virulence genes of Enterococcus faecalis isolated from subclinical bovine mastitis cases in China. J Dairy Sci 2019, 102, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, L.; Xu, R.; Yuan, X.; Ren, Z.; Song, H.; Lai, H.; Sun, Z.; Deng, H.; Yang, B.; Yu, D. Heat stress enhances the occurrence of erythromycin resistance of Enterococcus isolates in mice feces. J Therm Biol 2024, 120, 103786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Yang, Y.; Wang, T.; Sun, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ji, J.; Sun, X. Effects of acid, alkaline, cold, and heat environmental stresses on the antibiotic resistance of the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Food Res Int 2021, 144, 110359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Nabulsi, A.A.; Osaili, T.M.; Elabedeen, N.A.; Jaradat, Z.W.; Shaker, R.R.; Kheirallah, K.A.; Tarazi, Y.H.; Holley, R.A. Impact of environmental stress desiccation, acidity, alkalinity, heat or cold on antibiotic susceptibility of Cronobacter sakazakii. Int J Food Microbiol 2011, 146, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorrian, J.M.; Briggs, D.A.; Ridley, M.L.; Layfield, R.; Kerr, I.D. Induction of a stress response in Lactococcus lactis is associated with a resistance to ribosomally active antibiotics. FEBS J 2011, 278, 4015–4024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Verdugo, A.; Gaut, B.S.; Tenaillon, O. Evolution of Escherichia coli rifampicin resistance in an antibiotic-free environment during thermal stress. BMC Evol Biol 2013, 13, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochera, A.; Muppirala, A.N.; Kuziel, G.A.; Soualhi, S.; Shepherd, A.; Sun, L.; Issac, B.; Rosenberg, H.J.; Karim, F.; Perez, K.; et al. Enteric glia regulate Paneth cell secretion and intestinal microbial ecology. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLSI. CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 32nd ed.CLSI supplement M100. 2022.

- Blanco, A.E.; Barz, M.; Cavero, D.; Icken, W.; Sharifi, A.R.; Voss, M.; Buxade, C.; Preisinger, R. Characterization of Enterococcus faecalis isolates by chicken embryo lethality assay and ERIC-PCR. Avian Pathol 2018, 47, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Huang, J.; Huang, X.; He, Y.; Sun, J.; Dai, X.; Wang, X.; Shafiq, M.; Wang, L. Horizontal Transfer of Different erm(B)-Carrying Mobile Elements Among Streptococcus suis Strains With Different Serotypes. Front Microbiol 2021, 12, 628740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, P.T.; Bell, J.A.; Bejcek, C.E.; Malik, A.; Mansfield, L.S. An antibiotic depleted microbiome drives severe Campylobacter jejuni-mediated Type 1/17 colitis, Type 2 autoimmunity and neurologic sequelae in a mouse model. J Neuroimmunol 2019, 337, 577048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, P.; Hirt, H.; Bendahmane, A. The heat-shock protein/chaperone network and multiple stress resistance. Plant Biotechnol J 2017, 15, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acunzo, J.; Katsogiannou, M.; Rocchi, P. Small heat shock proteins HSP27 (HspB1), alphaB-crystallin (HspB5) and HSP22 (HspB8) as regulators of cell death. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2012, 44, 1622–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamaki, K.; Otaka, M.; Takada, M.; Yamamoto, S.; Odashima, M.; Itoh, H.; Watanabe, S. Evidence for enhanced cytoprotective function of HSP90-overexpressing small intestinal epithelial cells. Dig Dis Sci 2011, 56, 1954–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Lv, Y.; Yue, Z.; Islam, A.; Rehana, B.; Bao, E.; Hartung, J. Effects of transportation on expression of Hsp90, Hsp70, Hsp27 and alphaB-crystallin in the pig stomach. Vet Rec 2011, 169, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabler, T.W.; Greene, E.S.; Orlowski, S.K.; Hiltz, J.Z.; Anthony, N.B.; Dridi, S. Intestinal Barrier Integrity in Heat-Stressed Modern Broilers and Their Ancestor Wild Jungle Fowl. Front Vet Sci 2020, 7, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, W.; Wu, E.; Wang, K.; Chen, X.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, G.; Lv, F.; Wang, Y.; Peng, X.; et al. Polysaccharides From Abrus cantoniensis Hance Modulate Intestinal Microflora and Improve Intestinal Mucosal Barrier and Liver Oxidative Damage Induced by Heat Stress. Front Vet Sci 2022, 9, 868433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouellette, A.J.; Selsted, M.E. Paneth cell defensins: endogenous peptide components of intestinal host defense. FASEB J 1996, 10, 1280–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.Y.; Boivin, M.A.; Ye, D.; Pedram, A.; Said, H.M. Mechanism of TNF-alpha modulation of Caco-2 intestinal epithelial tight junction barrier: role of myosin light-chain kinase protein expression. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2005, 288, G422–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M.; Madsen, K.; Spiller, R.; Greenwood-Van Meerveld, B.; Verne, G.N. Intestinal barrier function in health and gastrointestinal disease. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2012, 24, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bischoff, S.C.; Barbara, G.; Buurman, W.; Ockhuizen, T.; Schulzke, J.D.; Serino, M.; Tilg, H.; Watson, A.; Wells, J.M. Intestinal permeability--a new target for disease prevention and therapy. BMC Gastroenterol 2014, 14, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastorelli, L.; De Salvo, C.; Mercado, J.R.; Vecchi, M.; Pizarro, T.T. Central role of the gut epithelial barrier in the pathogenesis of chronic intestinal inflammation: lessons learned from animal models and human genetics. Front Immunol 2013, 4, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Yin, J.; Du, M.; Yan, P.; Xu, J.; Zhu, X.; Yu, J. Heat-stress-induced damage to porcine small intestinal epithelium associated with downregulation of epithelial growth factor signaling. J Anim Sci 2009, 87, 1941–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabuurs, M.J.; Van Essen, G.J.; Nabuurs, P.; Niewold, T.A.; Van Der Meulen, J. Thirty minutes transport causes small intestinal acidosis in pigs. Res Vet Sci 2001, 70, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmid, T.E.; Multhoff, G. Radiation-induced stress proteins - the role of heat shock proteins (HSP) in anti- tumor responses. Curr Med Chem 2012, 19, 1765–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, L.; Durand, R.; Grenier, F.; Yang, J.; Yu, K.; Burrus, V.; Liu, J.H. PixR, a Novel Activator of Conjugative Transfer of IncX4 Resistance Plasmids, Mitigates the Fitness Cost of mcr-1 Carriage in Escherichia coli. mBio 2022, 13, e0320921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrindt, U.; Hochhut, B.; Hentschel, U.; Hacker, J. Genomic islands in pathogenic and environmental microorganisms. Nat Rev Microbiol 2004, 2, 414–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Chen, H.; Su, C.; Yan, S. Abundance and persistence of antibiotic resistance genes in livestock farms: a comprehensive investigation in eastern China. Environ Int 2013, 61, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Gomis, J.; Marin, P.; Otal, J.; Galecio, J.S.; Martinez-Conesa, C.; Cubero, M.J. Resistance patterns to C and D antibiotic categories for veterinary use of Campylobacter spp., Escherichia coli and Enterococcus spp. commensal isolates from laying hen farms in Spain during 2018. Prev Vet Med 2021, 186, 105222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, N.; Sun, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liao, X.; Mi, J. Short-term cold stress can reduce the abundance of antibiotic resistance genes in the cecum and feces in a pig model. J Hazard Mater 2021, 416, 125868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, N.; Li, N.; Duan, X.; Niu, H. Interaction between the gut microbiome and mucosal immune system. Mil Med Res 2017, 4, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevers, D.; Kugathasan, S.; Denson, L.A.; Vazquez-Baeza, Y.; Van Treuren, W.; Ren, B.; Schwager, E.; Knights, D.; Song, S.J.; Yassour, M.; et al. The treatment-naive microbiome in new-onset Crohn's disease. Cell Host Microbe 2014, 15, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Groups | Segments | ermA | ermB | mefA | fexA | optrA | tetS | tetL |

| CON | Ileum | 0.0(0/32) | 0.0(0/32) | 0.0(0/32) | 0.0(0/32) | 0.0(0/32) | 0.6(20/32) | 0.1(2/32) |

| Cecum | 0.0(0/48) | 0.0(0/48) | 0.0(0/48) | 0.0(0/48) | 0.0(0/48) | 0.3(13/48) | 0.1(3/48) | |

| Colon | 0.0(0/34) | 0.0(0/34) | 0.0(0/34) | 0.0(0/34) | 0.0(0/34) | 0.5(18/34) | 0.1(4/34) | |

| Rectum | 0.0(0/40) | 0.0(0/40) | 0.0(0/40) | 0.0(0/40) | 0.0(0/40) | 0.5(20/40) | 0.02(1/40) | |

| Total | 0.0(0/154) | 0.0(0/154) | 0.0(0/154) | 0.0(0/154) | 0.0(0/154) | 0.5(71/154) | 0.1(10/154) | |

| HS | Ileum | 2.1(1/48) | 31.2(15/48) | 4.2(0/48) | 2.1(1/48) | 0.0(0/48) | 0.3(12/48) | 0.02(1/48) |

| Cecum | 0.0(0/55) | 58.2(32/55) | 1.8(0/55) | 10.9(6/55) | 1.8(1/55) | 0.4(20/55) | 0.1(5/55) | |

| Colon | 0.0(0/62) | 68.8(44/62) | 1.6(0/62) | 1.6(1/62) | 1.6(1/62) | 0.5(30/62) | 0.1(4/62) | |

| Rectum | 1.7(1/60) | 76.7(46/60) | 3.3(1/60) | 5(3/60) | 1.7(1/60) | 0.3(15/60) | 0.02(1/60) | |

| Total | 0.9(2/225) | 60.1(137/225) | 0.5 (1/225) | 4.9(11/225) | 1.3(3/225) | 0.3(77/225) | 0.05(11/225) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).