Submitted:

13 March 2025

Posted:

14 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Type of Study, Site, and Sample

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Experimental Design

2.4. Procedures

2.4.1. Physical Activity Level (PAL)

2.4.2. Body Mass and Height

2.4.3. Body Composition

2.4.4. Handgrip Strength (HGS)

2.4.5. Flexibility

2.4.6. Lower Limb Endurance

2.5. Statistical Analysis

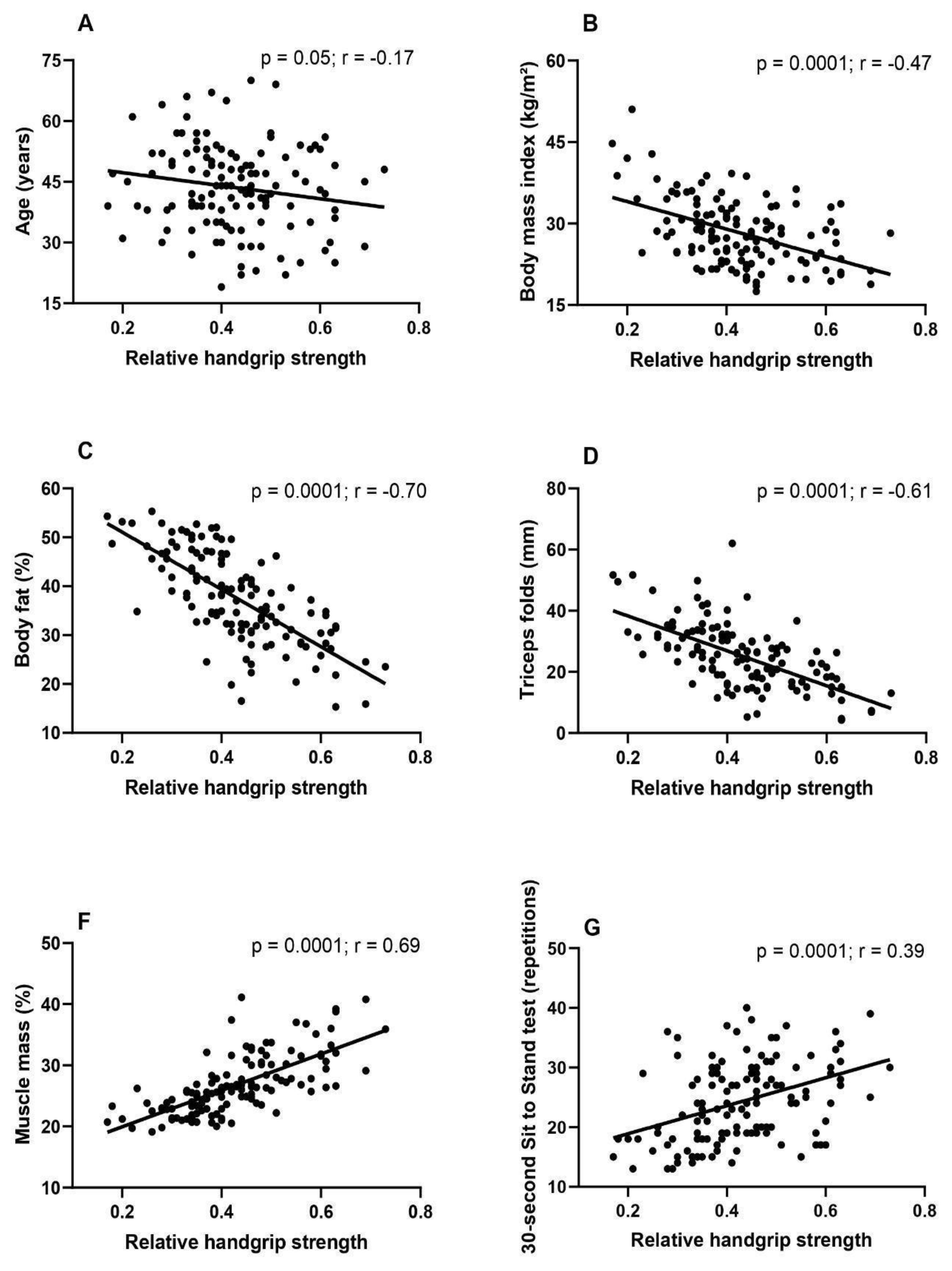

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cassee, F.R.; Bleeker, E.A.J.; Durand, C.; Exner, T.; Falk, A.; Friedrichs, S.; Heunisch, E.; Himly, M.; Hofer, S.; Hofstätter, N.; Hristozov, D.; Nymark, P.; Pohl, A.; Soeteman-Hernández, L.G.; Suarez-Merino, B.; Valsami-Jones, E.; Groenewold, M. Roadmap towards safe and sustainable advanced and innovative materials. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 2024, 2, 105–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Useche, S.A.; Robayo, S.; Orozco-Fontalvo, M. The hidden cost of your 'too fast food': stress-related factors and fatigue predict food delivery riders' occupational crashes. Int J Occup Saf Ergon 2024, 30, 825–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Üngüren, E.; Tekin, Ö.A. The relationship between workplace toxicity, stress, physical activity and emotional eating. Int J Occup Saf Ergon 2024, 30, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamers, S.L.; Beresford, S.A.; Cheadle, A.D.; Zheng, Y.; Bishop, S.K.; Thompson, B. The association between worksite social support, diet, physical activity and body mass index. Prev Med 2011, 53, 53–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappa, S.; Ntella, V.; Giannakas, T.; Giannakoulis, V.G.; Papoutsi, E.; Katsaounou, P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun 2020, 88, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, F.B.; Lasgaard, M.; Willert, M.V.; Sørensen, J.B. Estimating the causal effects of work-related and non-work-related stressors on perceived stress level: A fixed effects approach using population-based panel data. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0290410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tazzeo, C.; Zucchelli, A.; Vetrano, D.L.; Demurtas, J.; Smith, L.; Schoene, D.; Sanchez-Rodriguez, D.; Onder, G.; Balci, C.; Bonetti, S.; Grande, G.; Torbahn, G.; Veronese, N.; Marengoni, A. Risk factors for multimorbidity in adulthood: A systematic review. Ageing Res Rev 2023, 91, 102039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, R.; Lloyd-Sherlock, P.; Soliz, P.; Ebrahim, S.; Vega, E.; Ordunez, P.; McKee, M. Trends in premature avertable mortality from non-communicable diseases for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a population-based study. Lancet Glob Health 2020, 8, e511–e523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchir, D.R.; Szafron, M.L. Occupational Health Needs and Predicted Well-Being in Office Workers Undergoing Web-Based Health Promotion Training: Cross-Sectional Study. J Med Internet Res 2020, 22, e14093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, C.; Pignata, S.; Bezak, E.; Tie, M.; Childs, J. Workplace interventions to improve well-being and reduce burnout for nurses, physicians and allied healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e071203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzmarzyk, P.T.; Powell, K.E.; Jakicic, J.M.; Troiano, R.P.; Piercy, K.; Tennant, B. Sedentary Behavior and Health: Update from the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2019, 51, 1227–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mixter, S.; Mathiassen, S.E.; Bjärntoft, S.; Lindfors, P.; Lyskov, E.; Hallman, D.M. Fatigue, Stress, and Performance during Alternating Physical and Cognitive Tasks-Effects of the Temporal Pattern of Alternations. Ann Work Expo Health 2021, 65, 1107–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, S.S.; Abbasi, M.; Mehrdad, R. Risk Factors for Upper Extremity Musculoskeletal Disorders Among Office Workers in Qom Province, Iran. Iran Red Crescent Med J 2016, 18, e29518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Gu, J.; Chen, R.; Wang, Q.; Ding, N.; Meng, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, H. Sheng, Z.; Zheng, H. Handgrip Strength and Muscle Quality: Results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Database. J Clin Med 2023, 12, 3184. [CrossRef]

- Gouvêa-E-Silva, L.F.; Brito, E.R.; Sol, N.C.C.; Fernandes, E.V.; Xavier, M.B. Relationship of handgrip strength with health indicators of people living with HIV in west Pará, Brazil. Int J STD AIDS 2023, 34, 932–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.Y. Importance of Handgrip Strength as a Health Indicator in the Elderly. Korean J Fam Med 2021, 42, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S. Associations Between Dietary Patterns and Handgrip Strength: The Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2014-2016. J Am Coll Nutr 2020, 39, 488–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Väisänen, D.; Kallings, L.V.; Andersson, G.; Wallin, P.; Hemmingsson, E.; Ekblom-Bak, E. Lifestyle-associated health risk indicators across a wide range of occupational groups: a cross-sectional analysis in 72,855 workers. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.H.; Macfarlane, D.J.; Lam, T.H.; Stewart, S.M. Validity of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form (IPAQ-SF): a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2011, 8, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, D.M.; Gouvêa-e-Silva, L.F.; da Costa, V.S.; Villela, E.F.M.; Fernandes, E.V. Association between social isolation, level of physical activity, and sedentary behavior in pandemic times. Rev. Bras. Promoç. Saúde 2021, 34, 12280. [CrossRef]

- Basso, G.D.B.; Siqueira, M.A.; Kono, E.M.; Souza, J.D.; Baseggio, L.T.; Fernandes, E.V.; Takanashi, S.Y.L.; Gouvêa-e-Silva, L.F. Relationship between handgrip strength and body composition and laboratory indicators in diabetic and hypertensive patients. Medicina (Ribeirão Preto) 2023, 56, e-210088. [CrossRef]

- Heubel, A.D.; Gimenes, C.; Marques, T.S.; Arca, E.A.; Martinelli, B.; Barrile, S.R. Multicomponent training improves functional fitness and glycemic control in elderly people with type 2 diabetes. J Phys Educ 2018, 29, e2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, C.C.A.; Abad, C.C.C.; Barros, R.V.; Barros Neto, T.L. Flexibility level obtained by the sit-and-reach test from a study conducted in Greater São Paulo. Braz. J. Cineantropon. Hum Perform 2010, 12, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demissie, B.; Bayih, E.T.; Demmelash, A.A. A systematic review of work-related musculoskeletal disorders and risk factors among computer users. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, F.W.; Roberts, C.K.; Thyfault, J.P.; Ruegsegger, G.N.; Toedebusch, R.G. Role of Inactivity in Chronic Diseases: Evolutionary Insight and Pathophysiological Mechanisms. Physiol Rev 2017, 97, 1351–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Wu, Z.; Huang, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Mo, X.; Lowis, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, M. Role of the physical fitness test in risk prediction of diabetes among municipal in-service personnel in Guangxi. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019, 98, e15842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tersa-Miralles, C.; Pastells-Peiró, R.; Rubí-Carnacea, F.; Bellon, F.; Rubinat Arnaldo, E. Effectiveness of workplace exercise interventions in the treatment of musculoskeletal disorders in office workers: a protocol of a systematic review. BMJ Open 2020, 2020 10, e038854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedenreich, C.; Lynch, B. Can living a less sedentary life decrease breast cancer risk in women? Womens Health (Lond) 2012, 8, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bácsné, Bába. É.; Müller, A.; Pfau, C.; Balogh, R.; Bartha, É.; Szabados, G.; Bács, Z.; Ráthonyi-Ódor, K., Ráthonyi, G. Sedentary Behavior Patterns of the Hungarian Adult Population. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023, 20, 2702. [CrossRef]

- Evenson, K.R.; Alhusseini, N.; Moore, C.C.; Hamza, M.M.; Al-Qunaibet, A.; Rakic, S.; Alsukait, R.F.; Herbst, C.H.; AlAhmed, R.; Al-Hazzaa, H.M.; Alqahtani, S.A. Scoping Review of Population-Based Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior in Saudi Arabia. J Phys Act Health 2023, 20, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.C.; Chang, S.H.; Yang, X. Relationship between Sociodemographic and Health-Related Factors and Sedentary Time in Middle-Aged and Older Adults in Taiwan. Medicina (Kaunas) 2024, 60, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mclaughlin, M.; Atkin, A.J.; Starr, L.; Hall, A.; Wolfenden, L.; Sutherland, R.; Wiggers, J.; Ramirez, A.; Hallal, P.; Pratt, M.; Lynch, B.M.; Wijndaele, K. Sedentary, Behaviour Council Global Monitoring Initiative Working Group. Worldwide surveillance of self-reported sitting time: a scoping review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2020, 17, 111. [CrossRef]

- Rocha, S.V.; Barbosa, A.R.; Araújo, T.M. Leisure-time physical inactivity among healthcare workers. Int J Occup Med Environ Health 2018, 31, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmaleh-Sachs, A.; Schwartz, J.L.; Bramante, C.T.; Nicklas, J.M.; Gudzune, K.A.; Jay, M. Obesity Management in Adults: A Review. JAMA 2023, 330, 2000–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares Amaro, M.G.; Conde de Almeida, R.A.; Marques Donalonso, B.; Mazzo, A.; Negrato, C.A. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among health professionals with shift work schedules: A scoping review. Chronobiol Int 2023, 40, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuzzo, J.L. Narrative Review of Sex Differences in Muscle Strength, Endurance, Activation, Size, Fiber Type, and Strength Training Participation Rates, Preferences, Motivations, Injuries, and Neuromuscular Adaptations. J Strength Cond Res 2023, 37, 494–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, G.K.; Rockov, Z.A.; Byrne, C.; Trentacosta, N.E.; Stone, M.A. The role of relaxin in anterior cruciate ligament injuries: a systematic review. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2023, 33, 3319–3326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udo, T.; Grilo, C.M. Physical activity levels and correlates in nationally representative sample of U.S. adults with healthy weight, obesity, and binge-eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord 2020, 53, 85-95. [CrossRef]

- Lima, T.R.D.; Silva, D.A.S.; Kovaleski, D.F.; González-Chica, D.A. The association between muscle strength and sociodemographic and lifestyle factors in adults and the younger segment of the older population in a city in the south of Brazil. Ciencia & saude coletiva 2018, 23, 3811-3820. [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.S.; Lee, H.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.K.; Lee, K.Y.; Kim, N.H.; Shin, C. Paravertebral Muscles as Indexes of Sarcopenia and Sarcopenic Obesity: Comparison With Imaging and Muscle Function Indexes and Impact on Cardiovascular and Metabolic Disorders. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2021, 216, 1596–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stenholm, S.; Tiainen, K.; Rantanen, T.; Sainio, P.; Heliövaara, M.; Impivaara, O.; Koskinen, S. Long-term determinants of muscle strength decline: prospective evidence from the 22-year mini-Finland follow-up survey. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012, 60, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, R.; Azevedo, I. Chronic inflammation in obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Mediators Inflamm 2010, 2010, 289645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamboni, M.; Mazzali, G.; Fantin, F.; Rossi, A.; Di Francesco, V. Sarcopenic obesity: a new category of obesity in the elderly. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2008, 18, 388–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.J.; Files, D.C.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Z.M.; Messi, M.L.; Gregory, H.; Stone, J.; Lyles, M.F.; Dhar, S.; Marsh, A.P.; Nicklas, B.J.; Delbono, O. Intramyocellular Lipid and Impaired Myofiber Contraction in Normal Weight and Obese Older Adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2016, 71, 557–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Ji, Y.; Wang, R.; Yang, H.; Cao, X., Lu, S. Association between systemic immune-inflammation index and sarcopenic obesity in middle-aged and elderly Chinese adults: a cross-sectional study and mediation analysis. Lipids Health Dis 2024, 23, 230. [CrossRef]

- Silva, N.A.; de Menezes, T.N.; de Melo, R.L.P.; Pedraza, D.F. Handgrip strength and flexibility and their association with anthropometric variables in the elderly. Revista da Associação Médica Brasileira 2013, 59, 128-135. [CrossRef]

- Ballarin, G.; Valerio, G.; Alicante, P.; Di Vincenzo, O.; Monfrecola, F.; Scalfi, L. Could BIA-derived phase angle predict health-related musculoskeletal fitness? A cross-sectional study in young adults. Nutrition 2024, 122, 112388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.; López Sánchez, G.F.; Veronese, N.; Soysal, P.; Kostev, K.; Jacob, L.; Rahmati, M.; Kujawska, A.; Tully, M.A.; Butler, L.; Il Shin, J.; Koyanagi, A. Association Between Pain and Sarcopenia Among Adults Aged ≥65 Years from Low- and Middle-Income Countries. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2023, 78, 1020–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.I.; Gu, K.M.; Park, S.Y.; Baek, M.S., Kim, W.Y.; Choi, J.C.; Shin, J.W.; Kim, J.Y.; Chang, Y.D.; Jung, J.W. Correlation of handgrip strength with quality of life-adjusted pulmonary function in adults. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0300295. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Kim, T.; Park, J.C.; Kim, Y.H. Usefulness of hand grip strength to estimate other physical fitness parameters in older adults. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 17496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Function | ||

| Administrative sector | 24 (77.4) | 63 (64.3) |

| Healthcare professional | 07 (22.6) | 35 (35.7) |

| Age (years) | ||

| <40 | 11 (35.5) | 36 (36.7) |

| ≥40 | 20 (64.5) | 62 (63.3) |

| CNCD | ||

| Yes | 17 (54.8) | 63 (64.3) |

| No | 14 (45.2) | 35 (35.7) |

| PAL | ||

| Active | 12 (38.7) | 47 (48.0) |

| Inactive | 19 (61.3) | 5 (52.0) |

| BMI (kg/m²) | ||

| <25 | 06 (19.4) | 56 (57.1) |

| ≥25 | 25 (80.6) | 42 (42.9) |

| Flexibility(cm) | ||

| <25 | 18 (56.2) | 41 (42.3) |

| ≥25 | 14 (43.8) | 56 (57.7) |

| SST (repetitions) | ||

| <25 | 11 (35.5) | 58 (59.2) |

| ≥25 | 20 (64.5) | 40 (40.8) |

| Variables | HGS relative | p | OR (95%CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Adequate | |||

| n (%) | n (%) | |||

| BMI (kg/m²) | ||||

| ≥25 | 29 (82.9) | 56 (59.6) | 0.01 | 3.2 (1.29 - 8.40) |

| <25 | 06 (17.1) | 38 (40.4) | ||

| CNCD | ||||

| Yes | 28 (80.0) | 52 (55.3) | 0.01 | 3.2 (1.24 - 8.11) |

| No | 07 (20.0) | 42 (44.7) | ||

| SST (repetitions) | ||||

| <25 | 29 (82.9) | 41 (43.6) | 0.001 | 6.2 (2.47 - 15.92) |

| ≥25 | 06 (17.1) | 53 (56.4) | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).