1. Introduction

Radiation is a term that carries both promise and peril for human life. It was first discovered on November 8, 1895, when Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen captured a famous “röntgenogram” of his wife's hand, revealing the bone and a wedding ring. He named the enigmatic radiation “X-ray” (Glasser, 1995). Shortly thereafter, Henri Becquerel serendipitously discovered the radiation emitted by uranium salts without any external energy source while investigating the properties of X-rays. Marie and Pierre Curie made a breakthrough discovery by conducting further investigations and discovering additional elements like radium and polonium (Dutreix, 1996), which led to the term “radioactivity”.

1.1. Radiation

As defined by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), radiation is the emission and propagation of energy in the form of waves or particles that travel from one place to another (Galindo, 2023). Radiation can be classified into two types: ionizing radiation and non-ionizing radiation. Ionizing radiation comprises X-rays, gamma rays, and particles that can penetrate deep into tissues and cause DNA damage. It can have both immediate and long-term detrimental effects on living organisms, such as acute radiation syndrome, cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and other health issues (USEPA, 2023). Non-ionizing radiation, on the other hand, includes radio waves, microwaves, infrared, visible light, and ultraviolet radiation. Although it has less energy and is generally considered less harmful to biological tissues compared to ionizing radiation, it can still cause effects such as skin damage from excessive exposure to ultraviolet rays. Non-ionizing radiation, however, is generally not considered harmful to human health (Galindo, 2023).

1.2. Low and High Dose Radiation

Radiation doses are commonly measured in units called gray (Gy) and sievert (Sv). Sievert is used to measure the level of effectiveness of ionizing radiation on the human body and is the replacement for the older unit “rem” (roentgen equivalent man) (ICRP, 1977). In addition to the equivalent and effective dose, gray was introduced as the absorbed dose for a proper clinical judgement for tissue damage (Anon, 1987). This is necessary because actual doses may be exposed homogeneously, and the tissue may absorb a different dose than when it is released from the source. Although X-rays and gamma rays have the same radiation weighting factor (WR) from Gy to Sv, the WR for alpha particles differs. 1 Gy is equivalent to 20 Sv for alpha particles. Additionally, the expression of Gy and Sv are different in the International System (SI) units. Gy is expressed as 1 m²·s⁻² and Sv is expressed as 1 J/kg.

Low dose radiation, generally defined as a single dose below 100 mSv, is typically referred to when the dose is around or slightly above the levels of natural background radiation that humans are exposed to annually (typically around 2-3 mSv but can vary based on location and other factors). Low dose radiation is of interest in epidemiological studies and radiation protection guidelines because it represents the levels that the general population and workers in certain industries might be exposed to. The biological effects of low dose radiation are still an active area of research, with studies investigating potential risks such as cancer and genetic damage. On the other hand, exposure to radiation doses above 1 Sv is less common and typically associated with severe radiation accidents or specific medical treatments, which are known as high dose radiation. At these levels, there is a significant risk of acute health effects, such as radiation sickness, and long-term effects, including an increased risk of cancer. High dose radiation is a critical concern in radiation protection, emergency response, and medical management of radiation injuries. In certain contexts, the term “moderate dose” is used to describe a radiation dose that falls between 100 mSv and about 1 Sv, the range of which is higher than typical background levels and is particularly relevant in specific occupational or medical settings, such as radiology or nuclear industry workers who might be exposed to higher doses, as well as patients undergoing certain diagnostic or therapeutic procedures (Furukawa et al., 2016; Little et al., 2012; Little et al., 2021). Therefore, “moderate dose” helps to differentiate this range from the lower background levels as well as the higher levels associated with acute radiation sickness and other immediate health effects. When distinguishing between low and high radiation doses, Sv is typically used in radiation protection scenarios, while Gy is more commonly used in radiobiological studies and literature.

1.3. Non-targeted Effects (NTE) of Radiation

While the traditional understanding of radiation effects focused primarily on direct DNA damage, recent research has expanded our knowledge to include a range of NTE that occur even without direct absorption of radiation by nuclear DNA. These responses include genomic instability, which involves the transmission of genetic alterations over time and can lead to an increased risk of cancer; bystander effects, where non-irradiated cells near irradiated ones exhibit radiation-like effects due to signalling molecules or other factors; abscopal effects, a phenomenon where radiation treatment at one site leads to therapeutic effects at distant, non-irradiated sites, often observed in cancer therapy; and adaptive responses, where low doses of radiation induce cellular resistance to subsequent higher doses, potentially reducing harmful effects. According to Kadhim et al., the NTE of radiation at the cellular level can be generally classified into two types: time-related and space-related. Genomic instability is time-dependent, while bystander effects are space-dependent (Kadhim et al., 2021). Although genomic instability involving the transmission of genetic alterations from irradiated cells into progeny cells is an interesting topic, our review will focus on radiation-induced bystander effects (RIBE), with some touch on bystander-mediated adaptive response and abscopal effects.

1.4. Radiation Therapy (RT)

RT is a well-established and effective treatment for destroying cancer cells and saving patients’ lives, but it also has the potential to induce RIBE, which can influence the response of non-irradiated cells surrounding the treated area. Over the years, advancements in RT technology and techniques have significantly improved the precision and effectiveness of treatment while minimizing the impact on healthy tissues. However, it is still not well-understood how RIBE affects some treatment-induced abscopal and bystander effects. RT can be used in combination with chemotherapy and/or surgery. The modern methods include the most common external beam RT and brachytherapy where a small radioactive source is placed in or near the tumour inside the body (Baskar et al., 2012). Among ongoing advancements, microbeam RT and FLASH RT are emerging as promising treatments for the future. Understanding the role of RIBE is crucial in the context of RT, as RIBE can influence the response of non-irradiated cells in the surrounding tissue, potentially affecting the overall outcome of the treatment.

1.4.1. Microbeam Radiation Therapy (MRT)

MRT is a promising notion of therapy to treat cancer patients with arrays of synchrotron-generated X-ray microbeams (Schültke et al., 2017). Generated by a synchrotron particle accelerator, the high-intensity and high-collimated X-ray can be applied to a very thin area with several micrometres in width (Zeman et al., 1961). Therefore, radiation doses are deposited in the target tissue with a pattern of peak dose, valley dose, and a transitional zone, leaving approximately 200-400 µm between the centers of neighbouring radiation peaks (Grotzer et al., 2015; Schültke et al., 2017). Owning to the great tolerance of normal organs and blood vessels in previous preclinical studies, MRT is expected to significantly reduce normal tissue damage providing better cancer treatment. The spatially fractionated dose distribution in MRT may also influence RIBE, potentially contributing to its therapeutic efficacy by affecting the response of cells in the valley dose and transitional zones.

1.4.2. FLASH Radiation Therapy (FLASH-RT)

In addition to MRT, FLASH is another experimental RT in development. More than fifty registered clinical trials are ongoing or have been completed, making FLASH a more promising therapy with potential clinical applications (U.S.NLM). Although the phenomenon was first observed in the 1960s, there has been renewed interest in FLASH-RT, which delivers ultra-high radiation doses at an ultra-high dose rate (>40 Gy/s) (Bogaerts et al., 2022). Scientists observed both radiosensitivity reduction and tissue hypoxia in response to large pulses of radiation, as compared to ordinary dose rates (Dewey & Boag, 1959; Hornsey & Bewley, 1971; Lv et al., 2022). Thanks to the development of a related device and the observation of the protection effect known as less damage to normal tissue compared to traditional RT, FLASH-RT shed light on patients with cancers difficult to treat (Vozenin et al., 2019). The rapid delivery of radiation in FLASH-RT may also trigger RIBE, potentially contributing to its therapeutic efficacy and differential effects on normal and cancerous tissues.

2. RIBE and Its Mechanisms

2.1. The Discovery of RIBE

RIBE have been a subject of scientific investigation for several decades. Back in 1992, Nagasawa and Little demonstrated a notable increase in sister chromatid exchange within Chinese hamster ovary cells at a remarkably low dose of 0.3 mGy of α-irradiation (Nagasawa & Little, 1992). Based on their findings, the study revealed that with only 1% of nuclei traversed by an α-particle, 30% of cells exhibited an increased frequency of sister chromatid exchange (Nagasawa & Little, 1992). This observation led the researchers to hypothesize the existence of a mechanism through which genetic damage occurs, despite the limited direct interaction with α-particles. This phenomenon is termed as the “Bystander effect”. Along with other experimental evidence, RIBE started to challenge the traditional linear no-threshold (LNT) model used to estimate radiation risks for radiation protection purposes (Tubiana et al., 2009). Scientists used to believe that the effects of radiation exposure were directly proportional to the dose received and that there was no threshold below which radiation would have no effect. However, researchers began to observe that cells which were not directly exposed to radiation also exhibited biological changes, such as DNA damage and cellular responses. These changes occurred in neighbouring cells without direct radiation exposure, prompting a shift in the paradigm of radiation research. The focus is no longer solely on the cells that directly receive energy deposition, but also on neighbouring and distant cells that were previously considered less important.

2.2. The Mechanisms of RIBE

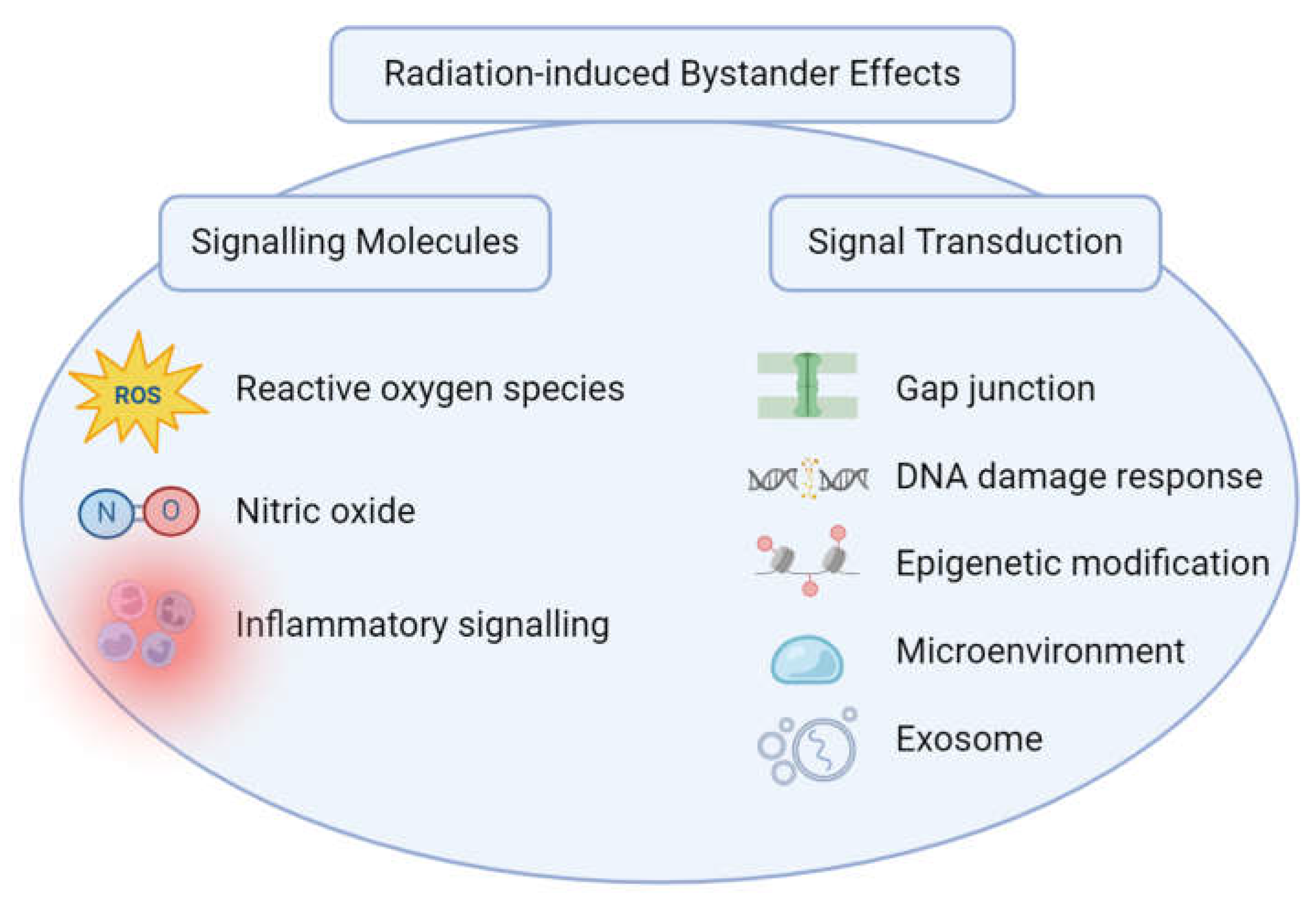

Cells exposed to radiation can trigger signalling molecules including reactive oxygen species (ROS), cytokines, and various elements. These signals can travel through and affect neighbouring cells and induce bystander effects. The bystander effect is affected by a variety of factors, including the type and dose of radiation, the distance between irradiated (donor) and bystander (recipient) cells, the types of cells involved, and genetic factors. Despite extensive ongoing research that has uncovered several factors, the mechanisms that influence the bystander impact are still waiting to be fully elucidated.

Figure 1 briefly shows RIBE mechanisms, categorized into signalling pathways and their approaches to signal transduction.

2.2.1. Signalling Molecules

Various signalling molecules are released by irradiated cells and can act as mediators of bystander effects. These molecules include cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, as well as nitric oxide (NO) and Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS). They can diffuse through the extracellular space and activate intracellular signalling pathways in neighbouring cells, leading to biological responses (Najafi et al., 2014). Lymphocytes and macrophages are also key signalling components that play a crucial role in the RIBE. However, their roles in the bystander effect are not as extensively studied as the roles of other factors.

Ionizing radiation can directly and indirectly generate ROS, including superoxide anions, hydrogen peroxide, and hydroxyl radicals. ROS then diffuse from irradiated cells to neighbouring non-irradiated cells, triggering oxidative stress and bystander responses (Mothersill & Seymour, 2006). In bystander cells, intracellular ROS are associated with micronuclei formation and mitochondrial dysfunction, indicating a dual role of ROS in RIBE, causing both DNA damage and protective autophagy (Wang et al., 2015). In addition, SirT1 knockdown promotes c-Myc transcription and ROS accumulation, indicating its potential to regulate RIBE by c-Myc-dependent ROS release (Xie et al., 2015). Interestingly, a study has shown a strong redox-mediated bystander effect by gradient-induced irradiation compared to uniform irradiation in a breast cancer cell line (Zhang et al., 2016).

NO is another signalling molecule which is released by the stimulation of irradiated cells (Yakovlev, 2015). The unique hydrophobic nature of NO allows it to easily permeate through the cytoplasm and plasma membrane, making it diffuse freely across these barriers without the need for gap junctions or other specialized transport mechanisms (Beckman & Koppenol, 1996). Therefore, NO is considered to facilitate chromosomal instability and DNA damage in bystander cells without direct radiation exposure (Lorimore et al., 1998; Watson et al., 2000). Matsumoto et al. demonstrated that exposure to X-ray irradiation leads to the activation of inducible nitric oxide synthase expression, which is detectable as early as three hours after irradiation and continues to escalate over the subsequent 24 hours (Matsumoto et al., 2001). In addition, the activity of constitutive nitric oxide synthase increased at a transient expression after radiation suggesting a NO-dependent pathway in the activation of adjacent cells (Kevin Leach et al., 2002). During both inducible and constitutive formats, NO can diffuse into neighbouring cells and exert its effects, potentially stimulating RIBE.

In addition to ROS and NO, inflammatory signals are also involved in bystander effects, including the pro-inflammatory cytokines released from irradiated and non-irradiated cells, such as interleukin-1 (IL-1), interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-8 (IL-8), tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) to name a few (Iyer & Lehnert, 2000; Pasi et al., 2010). When cells are exposed to RT, they can release cytokines and chemokines into the extracellular environment, which can activate a local immune response (Daguenet et al., 2020). It is believed that radiation can affect several immune-related components such as tumour-associated antigens (TAAs), antigen presenting cells (APCs), and cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), suggesting the contribution of radiation-making “in situ vaccinations” of the tumours that were irradiated (Gallo & Gallucci, 2013; Garnett et al., 2004; Lugade et al., 2005). As lymphocytes and macrophages play an important role in RIBE, scientists not only discovered low dose radiation could stimulate bystander effects in immune cells but further confirmed the production of NO and its association with the increasing production of cytokines (Hei et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2004; Najafi et al., 2014).

2.2.2. Signal Transduction

Signaling molecules do not act alone in affecting nearby or distant cells or tissue in response to radiation exposure, among which various mechanisms facilitate the process of signal transduction, including gap junctions through gap junctional intercellular communications (GJIC), and secreted components, such as the extracellular vesicles including exosomes (Kadhim et al., 2021).

Gap junctions, composed of integral membrane proteins called connexins, are intercellular channels that facilitate direct communication and the exchange of small molecules (≤1000 Da) between neighbouring cells for electrical and metabolic coordination (Alberts, 2015; Totland et al., 2020). GJIC can contribute to the transmission of bystander signals through the transmission of signalling molecules, ions, and secondary messengers from irradiated cells to non-irradiated cells, amplifying the bystander response (Azzam et al., 2003). For instance, hyperphosphorylation of the gap junction protein connexin43 was found to be associated with the closure of GJIC, indicating the protection of bystander cells with the inhibition of intercellular communication in the condition of low-energy ionizing radiation (Edwards et al., 2004).

In addition to direct physical contact, the DNA Damage Response (DDR) represents a sophisticated network of signalling pathways tasked with detecting and repairing DNA damage, playing an important role in responding to both direct and indirect radiation-induced damage. In bystander cells, the DDR can be activated by releasing signalling molecules or transferring damaged DNA or damaged DNA components from irradiated cells to recipient cells through intercellular communication. The in vivo mice sex-mismatch bone marrow transplantation experiments revealed that a p53-dependent cellular response to the initial radiation damage could cause an inflammatory process with cytokines releasing and subsequent p53-independent apoptotic pathways (Lorimore et al., 2013). In the prevalent context of p53 tumour suppressor pathway inactivation during cancer progression, this identification posits a potential therapeutic strategy by inducing tumour apoptosis through the utilization of RIBE. As comprehensively documented in prior reviews, the induction of DNA damage in bystander cells is attributed to the deregulation of redox homeostasis, coupled with the transformation of single-stranded DNA breaks into double-stranded ones, mediated by ROS (Jaiswal & Lindqvist, 2015). The function of ROS in the initiation of RIBE through the DDR pathway was also supported in the study of spatial signal transduction in the intra- and inter-system of C. elegans (Li et al., 2017).

Bystander effects have additionally been linked to changes in epigenetic regulation, including DNA methylation, histone alterations, and RNA-associated silencing, all of which have the potential to influence gene expression patterns within bystander cells (Belli & Tabocchini, 2020; Kovalchuk & Baulch, 2008). Changes in the epigenetic profiles can influence cellular responses and contribute to the long-lasting effects of bystander signalling. Research on lung cancer cell lines has revealed that ionizing radiation can induce increased CpG methylation in radiosensitive cell lines in comparison to radioresistant ones, which process may be modulated by downregulating the expression of the corresponding methylated gene, thereby enhancing the radio-resistance in cells previously characterized as radio-sensitive (Kim et al., 2010). The losses of histone and genomic DNA methylation are regarded as indicative of malignant transformation. Investigation into an in vivo mouse model revealed that exposure to low-dose X-ray irradiation resulted in a reduction of H4 histone trimethylation within the thymus, accompanied by a decrease in global DNA methylation and augmentation in DNA damage (Pogribny et al., 2005).

Furthermore, the microenvironment surrounding irradiated cells has the capacity to modulate bystander cells through components such as extracellular matrix constituents, intercellular interactions, and tissue-specific elements that can exert influence on both the transmission and amplification of bystander signals. The heterogeneity of cell types and the spatial configuration of these cells are also significant determinants of the magnitude and character of bystander responses. Observation from an ex vivo study on RIBE in both normal and malignant rectal tissues demonstrated a reduction in the level of oxidative phosphorylation in the mitochondria of bystander cells, suggesting that alterations in mitochondrial function and metabolism played a critical role in the mechanisms underpinning RIBE within the microenvironment (Heeran et al., 2021). In the context of RT, a recent transcriptomic study showed that breast cancer cells stimulated with surgical wound fluids with intraoperative radiotherapy and with conditioned medium from irradiated cells shared common enhancement of cell-cycle regulation, DNA repair, and oxidative phosphorylation, indicating RIBE might alter the biological properties of its biological environment (Kulcenty et al., 2020).

In addition to signal transduction mechanisms mentioned above, extracellular vesicles, notably exosomes, play an indispensable role in mediating intercellular communication, thereby facilitating the manifestation of the bystander effect in response to ionizing radiation. One of the consequences caused by the signalling molecules in exosomes is DNA breaks in the recipient cells, showing the bystander effect including the accumulation of γH2AX foci and generation of chromosomal lesions (Smolarz et al., 2022). Smolarz’s research shows that the activation of replication stress is critical for the cellular response in recipient cells triggered by exosomes discharged from irradiated cells, which is a process accompanied by the involvement of specific phosphorylated proteins contributing to cell adhesion and migration, consequently enhancing the motility of the recipient cells (Smolarz et al., 2022). Within the framework of human pancreatic cancer cell lines, it has been reported that exosomes from irradiated cells contribute to an elevation in intracellular ROS levels and an increase in DNA damage in the recipient cancer cells, according to which an amplified effect of radiation could be attributed to the mechanism of Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase enzyme (SOD1) inhibition by specific microRNAs contained within the exosomes (Nakaoka et al., 2021).

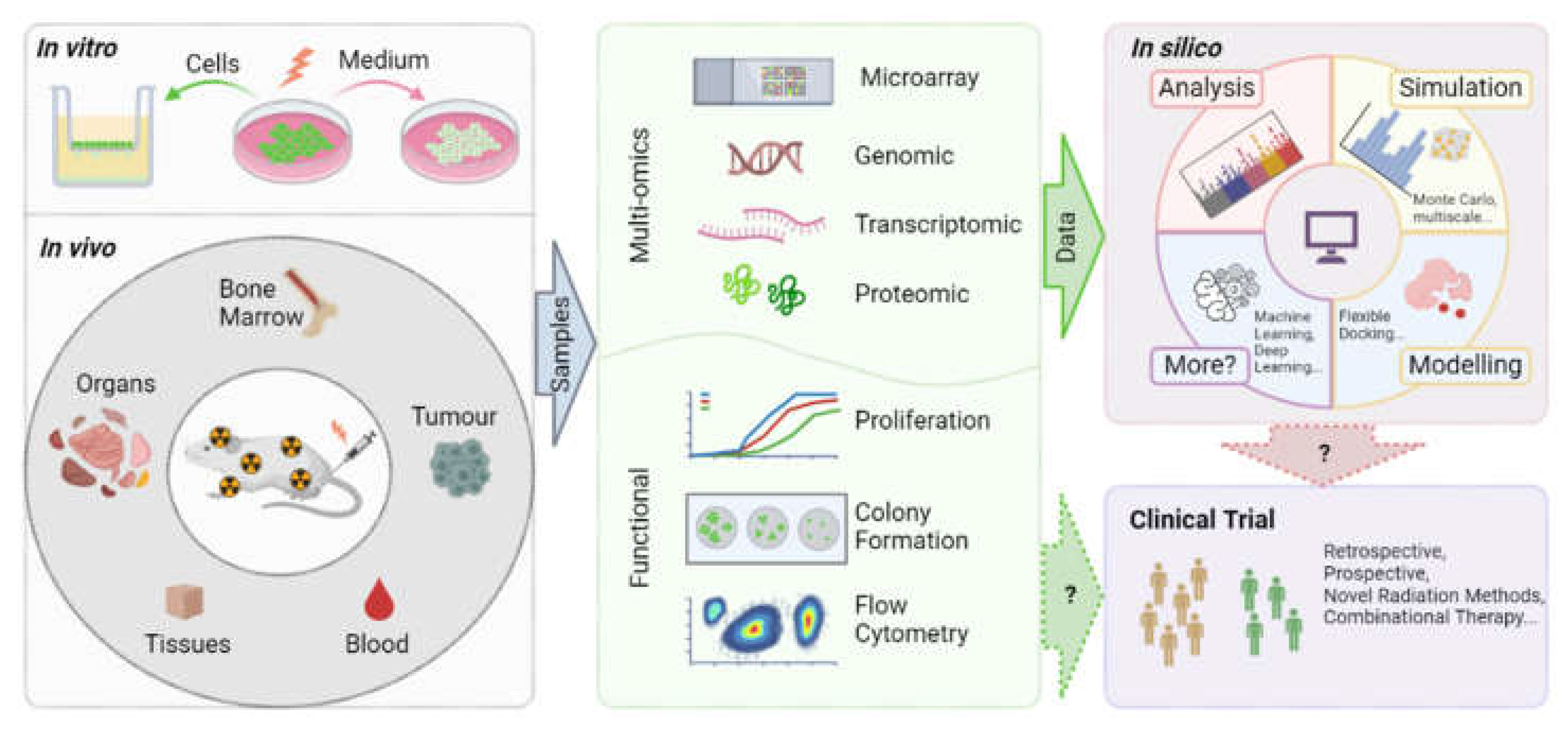

3. Experimental Methods of RIBE

The investigation of bystander effects within the realms of radiobiology and radiotherapy necessitates the utilization of diverse scientific methodologies and techniques to elucidate the biological alterations occurring in cells that were not directly exposed to irradiation. Several pertinent experimental techniques will be elaborated here including designs for

in vitro,

in vivo, and

in silico models, encompassing analyses at the cellular, molecular, and proteomic levels. A diagram provides an overview of the experimental methodologies discussed in this section and delineates their prospective pathways toward clinical trial application (

Figure 2).

3.1. In Vitro Study Methods

3.1.1. Medium Transfer Method:

The gamma radiation-caused bystander effect was first evaluated using the medium transfer method almost three decades ago, proving the toxic effect on unirradiated fibroblast cells from the medium produced by irradiated epithelial cell cultures (Mothersill & Seymour, 1997). Although this in vitro approach is straightforward, involving the transfer of growth medium from irradiated to unirradiated cell culture, it challenged the paradigm that nuclear damage from radiation is a necessary precursor for eliciting biological effects (Azzam & Little, 2004). Moreover, this method demonstrates that unirradiated cells can also manifest biological responses to the impact of ionizing radiation on adjacent cells, confirming and underscoring the RIBE and its influence on cellular behaviour. In addition to RIBE, the medium transfer technique is widely used in the study of radiation-induced adaptive effects by adding priming or initiating low dose irradiation.

3.1.2. Co-Culture Method:

The co-culture system is another in vitro method to qualitative and quantitative measure RIBE, in which irradiated cells are cultured together with non-irradiated cells and the biological changes in the non-irradiated cells are then monitored. According to an example study in combination of co-culture of irradiated and unirradiated rat liver epithelial cells with flow cytometry, gamma radiation showed a stimulating impact on the proliferation of adjacent unirradiated cells (Gerashchenko & Howell, 2003). On the other hand, a transwell insert co-culture system is applied for a better physical separation of the irradiated and unirradiated cells to study medium-mediated and GJIC-mediated RIBE (Verma & Tiku, 2017; Yang et al., 2005). Interestingly, different cell types could be cultured at each side of the porous membrane with physical separation, making it a well-designed in vitro model for studying gap junctions and signal transduction in a double-layered co-culture system (Buonanno et al., 2011; de Toledo et al., 2017). By choosing the size of the porous membrane, various particles and soluble factors would be allowed or blocked to transfer between the physical barrier, suggesting the possible mechanisms of signal transduction. The co-culture method could be coupled with a variety of endpoint studies, including DNA microarray analysis, microRNA analysis, clonogenic assay, gamma-H2AX foci formation, and apoptotic analysis, to name a few (Hu et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2012).

3.2. In Vivo Preclinical Study Methods:

Although conventional cell culture methods have revealed tremendous evidence, in vitro studies lack the cellular architecture, microenvironment, and immune responses that may play a critical role in the development of RIBE, especially in the context of carcinogenesis and radiotherapy (Chai & Hei, 2008). Bone marrow transplantation is one of the often used technologies to study the biological effects of radiation on hemopoietic stem cells in different rodent models, such as nude mice in chromosomal translocation and deletion, CBA/Ca mice in radiation-induced acute myeloid leukemia, and C57BL/6 mice in delayed genomic instability (Chai & Hei, 2008; Watson et al., 2000). Interestingly, a recent study for the first time demonstrated that extracellular vesicles isolated from bone marrows of irradiated mice could induce RIBE by reducing the expression of antioxidant enzyme genes, therefore altering the cellular redox system (Hargitai et al., 2021). In the context of carcinogenesis, the syngeneic model is often applied, including implanting tumour tissue or cells from donor mice subcutaneously into immunocompetent mice, marking it a better model than the xenograft model in the aspect of functional immune system and interactive responses (Redon et al., 2010). This also leads to the study of the radiation-induced abscopal effect, in which a distant organ or tissue may be influenced by the signals transported from the original site to another part of the body. Another widely used method especially for RT is partial irradiation, meaning that irradiation is only applied in a localized region of the body, such as the left or right lung, the head, part of the skin tissue, or specific organ and limps of the animal, while the rest of the body is shielded from irradiation. This method has been demonstrated as a well-established in vivo method, confirming the observation of RIBE from in vitro studies, including radiation-induced production of ROS, NO, and DNA damage in both in and out of radiation fields (Khan et al., 1998; Khan et al., 2003).

3.3. In Silico Method:

Although there are only three available studies of RIBE using the in silico method, computational simulation has been explored in the past two decades to predict the bystander effect to complement the signal transduction and cell communication between irradiated and recipient cells. With the availability of experimental data, the comparison between computer simulations with experimental results has become practical by using the Monte Carlo method. A preliminary model was presented by using the random reaction time technique on the diffusion model to study RIBE and calculate the induced oncogenic transformation frequencies observed in experiments, showing fewer bystander effects in the situation of high-dose broad-beam irradiation (Khvostunov & Nikjoo, 2002). In the spatial distribution study of bystander cells, Poisson statistics were introduced to estimate the bystander signal emission, showing good agreement with corresponding experimental results (Sasaki et al., 2012). In the context of understanding the role of RIBE in risk management after cancer treatment, multiscale mathematical models could serve as a powerful tool to explore the spatio-temporal characteristics of radiotherapy, especially in the prediction of bystander signals in low-dose hypersensitivity (Powathil et al., 2016). By screening small molecule clinical compounds with an in silico flexible docking approach, a modelling method to predict the interaction between a molecule and a protein with three-dimensional structures, potential radioprotectors were reported as novel candidates to target the protein-inducing inflammation and RIBE, such as cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) (Joshi et al., 2013). Currently, there is no available study utilizing machine learning or deep learning to explore the multiscale biological endpoints of RIBE, leaving a potential niche in the further development of methodology.

3.4. Multi-Omics Study Methods:

Genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics are high-throughput techniques that can provide comprehensive insights into the molecular changes associated with RIBE by identifying changes in gene expression, protein levels, and metabolic pathways in bystander cells. Although a comprehensive study that integrates multiple omics analyses has yet to be undertaken, an extensive body of research has been conducted at individual levels, laying the foundation for the potential development of multi-omics investigations. Even though a recent study did not specify the dosage or dose rate of radiation administered, it showed the involvement of radiation-specific CD8+ T cells in facilitating intestinal cell-to-cell communication as the bystander effects corresponding to RT through the technology of single-cell RNA sequencing (Han et al., 2022). Genome-wide microarray was also employed previously to investigate the transcriptional responses of radiation and RIBE, indicating the propagation of bystander effects with the transient enrichment in genes belonging to the ribosome, oxidative phosphorylation, as well as the induction of apoptotic signalling and formation of cellular immune response (Kalanxhi & Dahle, 2012). Furthermore, a two-dimensional gel-based proteomic approach was utilized to identify stress granules in chondrosarcoma cells, contributing to the understanding of low-dose radiation-induced bystander effects, which shed light on various cellular and molecular mechanisms involvement, including the oxidative stress response and exosome pathways, among others (Tudor et al., 2021). Although metabolomics study pertaining to RIBE is still in its infancy with very few studies available, one of which used a Seahorse technology to measure oxygen consumption rate and extracellular acidification rate in a human rectal cancer ex vivo explant model, assessing mitochondrial respiration and glycolysis simultaneously (Agilent, 2024; Buckley et al., 2019; Heeran et al., 2021). The other study applied ex vivo tissue nuclear magnetic resonance metabolomics to reveal the bystander metabolic change induced by liver irradiation in mouse liver parenchyma, which also raised the concern of clinical practice with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography and computed tomography (18F-FDG PET/CT) imaging in hepatocellular carcinoma patients (Chung et al., 2021).

4. Clinical Trial Studies

In a systematic search for registered clinical trials employing the keywords “microbeam” and “FLASH” in conjunction with “radiation” and/or “radiotherapy”, it was found that, despite the promising potential of these radiation therapies, no studies have been conducted on microbeam radiotherapy at this moment (U.S.NLM).

The potential connection between RIBE and FLASH-RT lies in the unique biological responses elicited by the rapid delivery of radiation in FLASH-RT. Some studies have suggested that FLASH-RT may induce fewer detrimental bystander effects compared to conventional radiotherapy. However, of the aforementioned fifty-seven clinical trials identified using the keywords “FLASH” and “radiation”, merely four explicitly utilize FLASH radiotherapy as the intervention treatment. The details of the four FLASH radiotherapy clinical trials are summarised in Table 1 (please refer to the milestone memo). The studies range from feasibility assessments to phase II trials, examining the efficacy, safety, and outcomes of FLASH radiotherapy across multiple clinical conditions and participants without previous RT, including symptomatic bone metastases, skin cancer and melanoma. In the first complete clinical nonrandomized trial of FLASH radiation treatment (FAST-01), ultra-high-dose-rate proton FLASH radiotherapy showed clinical feasibility with consistent adverse events compared to conventional radiotherapy (Mascia et al., 2023; U.S.NLM, 2020). Building on the initial success, the FAST-02 trial is currently in the recruitment stage and is actively ongoing (U.S.NLM, 2022). This subsequent study is designed to administer the same radiation dose of 8 Gy, as in its predecessor, FAST-01. However, it distinguishes itself by extending the evaluation period post-treatment, aiming to comprehensively assess long-term outcomes and effects. Switzerland, alongside the U.S., is at the forefront of incorporating FLASH radiotherapy into clinical trials, spearheading efforts to evaluate its efficacy in both Phase I and II settings with a larger participant cohort than those in the FAST-01 and FAST-02 trials. The Phase I Irradiation of Melanoma in a Pulse (IMPulse) trial, conducted in Switzerland, represents a groundbreaking first-in-human, dose-finding study of high-dose-rate radiotherapy for patients with skin metastases from melanoma (U.S.NLM, 2021). Consistent with the inclusion criteria of the aforementioned studies, only individuals aged eighteen and above are considered eligible. Conversely, the Phase II FLASH Radiotherapy for Skin Cancer (LANCE) trial distinctively sets the minimum age requirement at sixty years, aiming to enroll 60 participants, which is uniquely focused on comparing FLASH radiotherapy against conventional modalities, underscoring its potential to redefine treatment paradigms (U.S.NLM, 2023).

In the context of clinical trials investigating RIBE, a comprehensive search was conducted on ClinicalTrials.gov using the keywords "radiation" and "bystander effect." This search yielded a limited number of studies, with only four registered clinical trials identified, encompassing a broad temporal range, extending from as early as 2005 up to the recent year of 2023 (U.S.NLM, 2024). Among the identified studies, half explicitly measured radiotherapy-associated bystander effects as either a primary or secondary outcome (Table 2, also see the milestone memo).

Notably, while a singular Phase I proof of principle trial from Austria was terminated due to limited patient recruitment, its Phase II counterpart has been completed (Tubin et al., 2020; U.S.NLM, 2019). The unconventional RT is designed to enhance therapeutic outcomes by inducing bystander and abscopal effects through partial tumour irradiation, supported by preclinical findings that hypoxic tumour segments have a greater potential for generating these effects compared to normoxic cells (Tubin et al., 2018; Tubin & Raunik, 2017). The Phase I study assessed the unconventional stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) for unresectable bulky tumours by targeting their hypoxic segments (SBRT-PATHY), measuring non-targeted effects of radiotherapy, including bystander (local) and abscopal (distant) effects (Tubin, Popper, et al., 2019). This study involved 23 patients receiving localized irradiation of hypoxic tumour segments without systemic therapy, demonstrating an 87% progression-free survival rate, with bystander and abscopal response rates of 96% and 52%, respectively, and significant tumour reduction without any toxicity, highlighting feasibility and efficacy of this novel treatment in bulky tumour management (Tubin, Popper, et al., 2019). Following that, a mono-institutional phase II trial investigated SBRT-PATHY versus standard chemotherapy and palliative radiotherapy in 60 non-small cell lung cancer patients, revealing significantly improved overall and cancer-specific survival rates, tumour control, and induced bystander and abscopal effects (95% and 45%, respectively) with lower toxicity and better symptom management in SBRT-PATHY group (Tubin, Khan, et al., 2019). Meanwhile, the evaluation of time-synchronized immune-guided SBRT-PATHY through biomarker analysis illustrated an enhanced induction of bystander and abscopal effects, indicating a promising approach to align radiotherapy with the oscillating immune response, thereby potentially improving radiotherapy outcomes (Tubin, Ashdown, et al., 2019).

Apart from the application of RIBE to improve cancer treatment, the studies taken in France were initiated as a surveillance of the prostate adenocarcinoma patients who experienced overexposure to radiation, aiming for evaluation of the correlation of radiation toxicity in radiation-induced lymphocyte apoptosis (RILA) and circulating microvesicles using flow cytometry (Ribault et al., 2023; U.S.NLM, 2008b; Vogin et al., 2018). Nonetheless, the study found no significant association between RILA rates and the severity of toxicity, indicating that the degree of radiation overdosage may overshadow the predictive potential of individual radiosensitivity markers such as RILA (Vogin et al., 2018). On the other hand, scientists discovered that elevated levels of platelet- and monocyte-derived circulating microvesicles were significantly associated with higher rectal bleeding toxicity grades, suggesting new potential biomarkers for risk prediction in the situation of RT complications (Ribault et al., 2023).

In a Phase II clinical trial of high-risk prostate cancer with unknown status, the combination of gene therapy, androgen deprivation therapy, radiotherapy, and surgery was proposed to leverage the cytotoxic bystander effects, facilitated by immunological responses and gap junction-mediated metabolite transport, to enhance therapeutic efficacy (U.S.NLM, 2018). As of the preparation of this report, there have been no updates on this study. Another unknown-status study investigating haploidentical stem cell transplantation in combination with tumour-targeted radioisotope treatment with Iodine 131 labelled metaiodobenzylguanidine in neuroblastoma was designed by the hypothesis that tumour cells escaping natural killer cell-mediated immunity could be eradicated by infused donor T-cells through major histocompatibility complex-dependent mechanisms or via a bystander effect (U.S.NLM, 2008a). However, in a related comprehensive analysis of two prospective phase I/II trials on pediatric patients with refractory or relapsed metastatic neuroblastoma, the scientists claimed the feasibility of haploidentical stem cell transplantation as a treatment option along with tolerable side effects and no transplantation-related mortality, thereby suggesting potential for further post-transplantation therapeutic strategies leveraging the donor-derived immune system (Illhardt et al., 2018). Unfortunately, neither of these two studies targeted to understand the mechanisms and contributions of bystander effects related to radiotherapy. Given the limited research on RIBE in clinical contexts, a significant knowledge gap exists, underscoring the necessity for further exploration of this phenomenon.

5. Future Directions

A comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms underpinning RIBE is paramount for leveraging its capabilities in cancer therapy. Future investigations should prioritize the delineation of critical signaling molecules, including ROS, nitric oxide NO, and a variety of cytokines, that facilitate bystander effects. Unraveling the signaling pathways and genetic determinants involved in RIBE will shed light on methods to modulate these effects to enhance treatment efficacy. Utilization of advanced molecular and cellular methodologies, such as CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing and single-cell RNA sequencing, is advocated to explore the intricate interactions between irradiated and bystander cells.

The translation of RIBE knowledge into clinical application necessitates the execution of rigorously designed clinical trials. These trials are essential for evaluating the bystander effects' impact on tumor control, normal tissue toxicity, and overall patient survival. Investigating RIBE's role across various cancer types and stages is crucial for customizing radiation therapy protocols to optimize therapeutic outcomes while reducing adverse reactions.

Exploring the synergistic potential of RIBE with other therapeutic modalities, including immunotherapy, chemotherapy, or targeted therapy, presents a promising pathway to boost therapeutic efficacy. The integration of radiation therapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors, for instance, could potentiate immune-mediated bystander effects, thereby enhancing tumor suppression. The conduction of preclinical studies and clinical trials is imperative for identifying potent combinations and refining treatment schedules.

The identification of reliable biomarkers for the prediction and monitoring of bystander effects holds significance for personalized radiation therapy. Prospective biomarkers might encompass circulating microvesicles, cytokine profiles, or molecular signatures indicative of RIBE. The application of high-throughput omics technologies, such as proteomics and metabolomics, is instrumental in uncovering novel biomarkers. Clinical validation of these biomarkers will facilitate treatment customization based on individual patient reactions to radiation therapy.

Developing strategies to safeguard normal tissues from bystander effects, while amplifying the tumoricidal impact of radiation, represents a crucial research domain. This may involve the employment of radioprotectors or the targeted administration of radiation to minimize healthy tissue exposure. Additionally, examining the timing and sequencing of radiation therapy in conjunction with other treatments could aid in alleviating bystander-induced toxicity.

Technological advancements in imaging and radiation delivery are vital for the precise targeting of irradiated cells and the real-time monitoring of bystander effects. Innovations such as real-time imaging-guided radiation therapy, microbeam radiation therapy, and FLASH-RT introduce new avenues for minimizing bystander damage while effectively targeting tumor cells. The continued development and clinical integration of these technologies will enhance the precision and effectiveness of radiation therapy.

Addressing these pivotal areas, future research on RIBE holds the promise to substantially advance the comprehension and application of radiation therapy in the context of cancer treatment, ultimately leading to improved clinical outcomes.

6. Conclusion & Discussion

In this literature review, we include the mechanisms, methodologies, and implications of RIBE with a special focus on RT, underscoring the potential of RIBE to enhance the efficacy of cancer treatments. While MRT remains in the preclinical phase and FLASH-RT emerges as a promising direction, both strategies aim to enhance therapeutic outcomes and reduce collateral damage to healthy tissues. The capacity of RIBE to mediate effects in non-targeted cells suggests a paradigm shift in the application of radiobiological principles for clinical advantage, emphasizing precision in cancer treatment through a deeper understanding of RIBE mechanisms. This insight could lead to the development of therapies that harness bystander effects for improved clinical results, potentially optimizing tumour control and minimizing toxicity. Nonetheless, significant research is required to reveal the intricate signalling pathways of RIBE, setting the theoretical foundations for novel therapeutic approaches in clinical applications.

Acknowledgments

Funding and support for the research were provided by a Federal Nuclear Science and Technology Work Plan of the Atomic Energy of Canada Limited. Figures are created in BioRender.com

References

- Agilent. (2024). What does Seahorse XF technology measure? Agilent Technologies, Inc. Retrieved Feb. 15, 2024 from https://www.agilent.com/en/support/cell-analysis/what-does-xf-tech-measure.

- Alberts, B. J., A.; Lewis, J.; Morgan, D.; Raff, M.; Roberts, K.; Walter, P. (2015). Molecular Biology of the Cell, 6th ed. Garland Science.

-

Anon. (1987). Radiation quantities and units ICRU report 33. International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements. http://inis.iaea.org/search/search.aspx?orig_q=RN:25005999 .

- Azzam, E. I., De Toledo, S. M., & Little, J. B. (2003). Oxidative metabolism, gap junctions and the ionizing radiation-induced bystander effect. Oncogene, 22(45 REV. ISS. 5), 7050-7057. [CrossRef]

- Azzam, E. I., & Little, J. B. (2004). The radiation-induced bystander effect: evidence and significance. Hum Exp Toxicol, 23(2), 61-65. [CrossRef]

- Baskar, R., Lee, K. A., Yeo, R., & Yeoh, K. W. (2012). Cancer and radiation therapy: current advances and future directions. Int J Med Sci, 9(3), 193-199. [CrossRef]

- Beckman, J. S., & Koppenol, W. H. (1996). Nitric oxide, superoxide, and peroxynitrite: the good, the bad, and ugly. Am J Physiol, 271(5 Pt 1), C1424-1437. [CrossRef]

- Belli, M., & Tabocchini, M. A. (2020). Ionizing Radiation-Induced Epigenetic Modifications and Their Relevance to Radiation Protection. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(17), 1-34. [CrossRef]

- Bogaerts, E., Macaeva, E., Isebaert, S., & Haustermans, K. (2022). Potential Molecular Mechanisms behind the Ultra-High Dose Rate "FLASH" Effect. Int J Mol Sci, 23(20). [CrossRef]

- Buckley, A. M., Dunne, M. R., Lynam-Lennon, N., Kennedy, S. A., Cannon, A., Reynolds, A. L., Maher, S. G., Reynolds, J. V., Kennedy, B. N., & O'Sullivan, J. (2019). Pyrazinib (P3), [(E)-2-(2-Pyrazin-2-yl-vinyl)-phenol], a small molecule pyrazine compound enhances radiosensitivity in oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Letters, 447, 115-129. [CrossRef]

- Buonanno, M., de Toledo, S. M., Pain, D., & Azzam, E. I. (2011). Long-term consequences of radiation-induced bystander effects depend on radiation quality and dose and correlate with oxidative stress. Radiat Res, 175(4), 405-415. [CrossRef]

- Chai, Y., & Hei, T. K. (2008). Radiation Induced Bystander Effect in vivo. Acta medica Nagasakiensia, 53(SUPPL.), S65-S65. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2903761/.

- Chung, Y. H., Tsai, C. K., Yu, C. F., Wang, W. L., Yang, C. L., Hong, J. H., Yen, T. C., Chen, F. H., & Lin, G. (2021). Radiation-Induced Metabolic Shifts in the Hepatic Parenchyma: Findings from (18)F-FDG PET Imaging and Tissue NMR Metabolomics in a Mouse Model for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Molecules, 26(9). [CrossRef]

- Daguenet, E., Louati, S., Wozny, A. S., Vial, N., Gras, M., Guy, J. B., Vallard, A., Rodriguez-Lafrasse, C., & Magne, N. (2020). Radiation-induced bystander and abscopal effects: important lessons from preclinical models. Br J Cancer, 123(3), 339-348. [CrossRef]

- de Toledo, S. M., Buonanno, M., Harris, A. L., & Azzam, E. I. (2017). Genomic instability induced in distant progeny of bystander cells depends on the connexins expressed in the irradiated cells. Int J Radiat Biol, 93(10), 1182-1194. [CrossRef]

- Dewey, D. L., & Boag, J. W. (1959). Modification of the oxygen effect when bacteria are given large pulses of radiation. Nature, 183(4673), 1450-1451. [CrossRef]

- Dutreix, J. (1996). From X-rays to radioactivity and radium. The discovery and works of Henri Becquerel (1851-1908). Bull Acad Natl Med, 180(1), 109-118. (Des rayons X à radioactivité et au radium. La découverte et l'oeuvre d'Henri Becquerel (1852-1908).).

- Edwards, G. O., Botchway, S. W., Hirst, G., Wharton, C. W., Chipman, J. K., & Meldrum, R. A. (2004). Gap junction communication dynamics and bystander effects from ultrasoft X-rays. British Journal of Cancer 2004 90:7, 90(7), 1450-1456. [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, K., Misumi, M., Cologne, J. B., & Cullings, H. M. (2016). A Bayesian Semiparametric Model for Radiation Dose-Response Estimation. Risk Anal, 36(6), 1211-1223. [CrossRef]

- Galindo, A. (2023, 17 Apr 2023). What is Radiation? International Atomic Energy Agency. Retrieved Jan. 3, 2024 from https://www.iaea.org/newscenter/news/what-is-radiation.

- Gallo, P. M., & Gallucci, S. (2013). The dendritic cell response to classic, emerging, and homeostatic danger signals. Implications for autoimmunity. Front Immunol, 4, 138. [CrossRef]

- Garnett, C. T., Palena, C., Chakraborty, M., Tsang, K. Y., Schlom, J., & Hodge, J. W. (2004). Sublethal irradiation of human tumor cells modulates phenotype resulting in enhanced killing by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Cancer Res, 64(21), 7985-7994. [CrossRef]

- Gerashchenko, B. I., & Howell, R. W. (2003). Flow cytometry as a strategy to study radiation-induced bystander effects in co-culture systems. Cytometry. Part A : the journal of the International Society for Analytical Cytology, 54(1), 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Glasser, O. (1995). W. C. Roentgen and the discovery of the Roentgen rays. American Journal of Roentgenology, 165(5), 1033-1040. [CrossRef]

- Grotzer, M. A., Schültke, E., Bräuer-Krisch, E., & Laissue, J. A. (2015). Microbeam radiation therapy: Clinical perspectives. Physica Medica, 31(6), 564-567. [CrossRef]

- Han, X., Chen, Y., Zhang, N., Huang, C., He, G., Li, T., Wei, M., Song, Q., Mo, S., & Lv, Y. (2022). Single-cell mechanistic studies of radiation-mediated bystander effects. Frontiers in Immunology, 13. [CrossRef]

- Hargitai, R., Kis, D., Persa, E., Szatmári, T., Sáfrány, G., & Lumniczky, K. (2021). Oxidative Stress and Gene Expression Modifications Mediated by Extracellular Vesicles: An In Vivo Study of the Radiation-Induced Bystander Effect. Antioxidants, 10(2), 156. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3921/10/2/156 .

- Heeran, A. B., Berrigan, H. P., Buckley, C. E., Bottu, H. M., Prendiville, O., Buckley, A. M., Clarke, N., Donlon, N. E., Nugent, T. S., Durand, M., Dunne, C., Larkin, J. O., Mehigan, B., McCormick, P., Brennan, L., Lynam-Lennon, N., & O'Sullivan, J. (2021). Radiation-induced Bystander Effect (RIBE) alters mitochondrial metabolism using a human rectal cancer ex vivo explant model. Translational Oncology, 14(1), 100882-100882. [CrossRef]

- Hei, T. K., Zhou, H., Ivanov, V. N., Hong, M., Lieberman, H. B., Brenner, D. J., Amundson, S. A., & Geard, C. R. (2008). Mechanism of radiation-induced bystander effects: a unifying model. J Pharm Pharmacol, 60(8), 943-950. [CrossRef]

- Hornsey, S., & Bewley, D. K. (1971). Hypoxia in mouse intestine induced by electron irradiation at high dose-rates. Int J Radiat Biol Relat Stud Phys Chem Med, 19(5), 479-483. [CrossRef]

- Hu, B., Shen, B., Su, Y., Geard, C. R., & Balajee, A. S. (2009). Protein Kinase C epsilon is involved in ionizing radiation induced bystander response in human cells. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology, 41(12), 2413-2413. [CrossRef]

- ICRP. (1977). Recommendations of the ICRP. ICRP Publication 26. Ann.: International Commission on Radiological Protection Retrieved from https://www.icrp.org/publication.asp?id=ICRP%20Publication%2026.

- Illhardt, T., Toporski, J., Feuchtinger, T., Turkiewicz, D., Teltschik, H.-M., Ebinger, M., Schwarze, C.-P., Holzer, U., Lode, H. N., Albert, M. H., Gruhn, B., Urban, C., Dykes, J. H., Teuffel, O., Schumm, M., Handgretinger, R., & Lang, P. (2018). Haploidentical Stem Cell Transplantation for Refractory/Relapsed Neuroblastoma. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, 24(5), 1005-1012. [CrossRef]

- Iyer, R., & Lehnert, B. E. (2000). Effects of ionizing radiation in targeted and nontargeted cells. Arch Biochem Biophys, 376(1), 14-25. [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, H., & Lindqvist, A. (2015). Bystander communication and cell cycle decisions after DNA damage. Frontiers in Genetics, 6(FEB). [CrossRef]

- Joshi, J., Barik, T. K., Shrivastava, N., Dimri, M., Ghosh, S., Mandal, R. S., Ramachandran, S., & Kumar, I. P. (2013). Cycloxygenase-2 (COX-2)--a potential target for screening of small molecules as radiation countermeasure agents: an in silico study. Curr Comput Aided Drug Des, 9(1), 35-45.

- Kadhim, M., Tuncay Cagatay, S., & Elbakrawy, E. M. (2021). Non-targeted effects of radiation: a personal perspective on the role of exosomes in an evolving paradigm. International Journal of Radiation Biology, 98(3), 410-420. [CrossRef]

- Kalanxhi, E., & Dahle, J. (2012). Genome-wide microarray analysis of human fibroblasts in response to γ radiation and the radiation-induced bystander effect. Radiat Res, 177(1), 35-43. [CrossRef]

- Kevin Leach, J., Black, S. M., Schmidt-Ullrich, R. K., & Mikkelsen, R. B. (2002). Activation of constitutive nitric-oxide synthase activity is an early signaling event induced by ionizing radiation. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 277(18), 15400-15406. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. A., Hill, R. P., & Van Dyk, J. (1998). Partial volume rat lung irradiation: an evaluation of early DNA damage. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 40(2), 467-476. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. A., Van Dyk, J., Yeung, I. W. T., & Hill, R. P. (2003). Partial volume rat lung irradiation; Assessment of early DNA damage in different lung regions and effect of radical scavengers. Radiotherapy and Oncology, 66(1), 95-102. [CrossRef]

- Khvostunov, I. K., & Nikjoo, H. (2002). Computer modelling of radiation-induced bystander effect. J Radiol Prot, 22(3a), A33-37. [CrossRef]

- Kim, E. H., Park, A. K., Dong, S. M., Ahn, J. H., & Park, W. Y. (2010). Global analysis of CpG methylation reveals epigenetic control of the radiosensitivity in lung cancer cell lines. Oncogene, 29(33), 4725-4731. [CrossRef]

- Kovalchuk, O., & Baulch, J. E. (2008). Epigenetic changes and nontargeted radiation effects--is there a link? Environ Mol Mutagen, 49(1), 16-25. [CrossRef]

- Kulcenty, K., Piotrowski, I., Rucinski, M., Wroblewska, J. P., Jopek, K., Murawa, D., & Suchorska, W. M. (2020). Surgical Wound Fluids from Patients with Breast Cancer Reveal Similarities in the Biological Response Induced by Intraoperative Radiation Therapy and the Radiation-Induced Bystander Effect-Transcriptomic Approach. Int J Mol Sci, 21(3). [CrossRef]

- Li, Q., Shi, J., Chen, L., Zhan, F., Yuan, H., Wang, J., Xu, A., & Wu, L. (2017). Spatial function of the oxidative DNA damage response in radiation induced bystander effects in intra- and inter-system of Caenorhabditis elegans. Oncotarget, 8(31), 51253-51263. [CrossRef]

- Little, M. P., Azizova, T. V., Bazyka, D., Bouffler, S. D., Cardis, E., Chekin, S., Chumak, V. V., Cucinotta, F. A., de Vathaire, F., Hall, P., Harrison, J. D., Hildebrandt, G., Ivanov, V., Kashcheev, V. V., Klymenko, S. V., Kreuzer, M., Laurent, O., Ozasa, K., Schneider, T.,…Lipshultz, S. E. (2012). Systematic review and meta-analysis of circulatory disease from exposure to low-level ionizing radiation and estimates of potential population mortality risks. Environmental health perspectives, 120(11), 1503-1511. [CrossRef]

- Little, M. P., Azizova, T. V., & Hamada, N. (2021). Low- and moderate-dose non-cancer effects of ionizing radiation in directly exposed individuals, especially circulatory and ocular diseases: a review of the epidemiology. Int J Radiat Biol, 97(6), 782-803. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S. Z., Jin, S. Z., & Liu, X. D. (2004). Radiation-induced bystander effect in immune response. Biomed Environ Sci, 17(1), 40-46.

- Lorimore, S. A., Kadhim, M. A., Pocock, D. A., Papworth, D., Stevens, D. L., Goodhead, D. T., & Wright, E. G. (1998). Chromosomal instability in the descendants of unirradiated surviving cells after alpha-particle irradiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 95(10), 5730-5733. [CrossRef]

- Lorimore, S. A., Rastogi, S., Mukherjee, D., Coates, P. J., & Wright, E. G. (2013). The influence of p53 functions on radiation-induced inflammatory bystander-type signaling in murine bone marrow. Radiation Research, 179(4), 406-415. [CrossRef]

- Lugade, A. A., Moran, J. P., Gerber, S. A., Rose, R. C., Frelinger, J. G., & Lord, E. M. (2005). Local radiation therapy of B16 melanoma tumors increases the generation of tumor antigen-specific effector cells that traffic to the tumor. J Immunol, 174(12), 7516-7523. [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y., Lv, Y., Wang, Z., Lan, T., Feng, X., Chen, H., Zhu, J., Ma, X., Du, J., Hou, G., Liao, W., Yuan, K., & Wu, H. (2022). FLASH radiotherapy: A promising new method for radiotherapy. Oncol Lett, 24(6), 419. [CrossRef]

- Mascia, A. E., Daugherty, E. C., Zhang, Y., Lee, E., Xiao, Z., Sertorio, M., Woo, J., Backus, L. R., McDonald, J. M., McCann, C., Russell, K., Levine, L., Sharma, R. A., Khuntia, D., Bradley, J. D., Simone, C. B., 2nd, Perentesis, J. P., & Breneman, J. C. (2023). Proton FLASH Radiotherapy for the Treatment of Symptomatic Bone Metastases: The FAST-01 Nonrandomized Trial. JAMA Oncol, 9(1), 62-69. [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, H., Hayashi, S., Hatashita, M., Ohnishi, K., Shioura, H., Ohtsubo, T., Kitai, R., Ohnishi, T., & Kano, E. (2001). Induction of Radioresistance by a Nitric Oxide-Mediated Bystander Effect. Radiation Research, 155(3), 387-396. [CrossRef]

- Mothersill, C., & Seymour, C. (1997). Medium from irradiated human epithelial cells but not human fibroblasts reduces the clonogenic survival of unirradiated cells. Int J Radiat Biol, 71(4), 421-427. [CrossRef]

- Mothersill, C., & Seymour, C. B. (2006). Radiation-induced bystander effects and the DNA paradigm: an "out of field" perspective. Mutation research, 597(1-2), 5-10. [CrossRef]

- Nagasawa, H., & Little, J. B. (1992). Induction of sister chromatid exchanges by extremely low doses of alpha-particles. Cancer Res, 52(22), 6394-6396. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1423287/.

- Najafi, M., Fardid, R., Hadadi, G., & Fardid, M. (2014). The mechanisms of radiation-induced bystander effect. J Biomed Phys Eng, 4(4), 163-172.

- Nakaoka, A., Nakahana, M., Inubushi, S., Akasaka, H., Salah, M., Fujita, Y., Kubota, H., Hassan, M., Nishikawa, R., Mukumoto, N., Ishihara, T., Miyawaki, D., Sasayama, T., & Sasaki, R. (2021). Exosome-mediated radiosensitizing effect on neighboring cancer cells via increase in intracellular levels of reactive oxygen species. Oncology Reports, 45(4). [CrossRef]

- Pasi, F., Facoetti, A., & Nano, R. (2010). IL-8 and IL-6 bystander signalling in human glioblastoma cells exposed to gamma radiation. Anticancer Res, 30(7), 2769-2772.

- Pogribny, I., Koturbash, I., Tryndyak, V., Hudson, D., Stevenson, S. M. L., Sedelnikova, O., Bonner, W., & Kovalchuk, O. (2005). Fractionated low-dose radiation exposure leads to accumulation of DNA damage and profound alterations in DNA and histone methylation in the murine thymus. Molecular cancer research : MCR, 3(10), 553-561. [CrossRef]

- Powathil, G. G., Munro, A. J., Chaplain, M. A., & Swat, M. (2016). Bystander effects and their implications for clinical radiation therapy: Insights from multiscale in silico experiments. J Theor Biol, 401, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Redon, C. E., Dickey, J. S., Nakamura, A. J., Kareva, I. G., Naf, D., Nowsheen, S., Kryston, T. B., Bonner, W. M., Georgakilas, A. G., & Sedelnikova, O. A. (2010). Tumors induce complex DNA damage in distant proliferative tissues in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(42), 17992-17997. [CrossRef]

- Ribault, A., Benadjaoud, M. A., Squiban, C., Arnaud, L., Judicone, C., Leroyer, A. S., Rousseau, A., Huet, C., Guha, C., Benderitter, M., Lacroix, R., Flamant, S., Chen, E. I., Simon, J. M., & Tamarat, R. (2023). Circulating microvesicles correlate with radiation proctitis complication after radiotherapy. Sci Rep, 13(1), 2033. [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, K., Wakui, K., Tsutsumi, K., Itoh, A., & Date, H. (2012). A simulation study of the radiation-induced bystander effect: modeling with stochastically defined signal reemission. Comput Math Methods Med, 2012, 389095. [CrossRef]

- Schültke, E., Balosso, J., Breslin, T., Cavaletti, G., Djonov, V., Esteve, F., Grotzer, M., Hildebrandt, G., Valdman, A., & Laissue, J. (2017). Microbeam radiation therapy - grid therapy and beyond: a clinical perspective. Br J Radiol, 90(1078), 20170073. [CrossRef]

- Smolarz, M., Skoczylas, Ł., Gawin, M., Krzyżowska, M., Pietrowska, M., & Widłak, P. (2022). Radiation-Induced Bystander Effect Mediated by Exosomes Involves the Replication Stress in Recipient Cells. Int J Mol Sci, 23(8). [CrossRef]

- Totland, M. Z., Rasmussen, N. L., Knudsen, L. M., & Leithe, E. (2020). Regulation of gap junction intercellular communication by connexin ubiquitination: physiological and pathophysiological implications. Cell Mol Life Sci, 77(4), 573-591. [CrossRef]

- Tubiana, M., Feinendegen, L. E., Yang, C., & Kaminski, J. M. (2009). The Linear No-Threshold Relationship Is Inconsistent with Radiation Biologic and Experimental Data. Radiology, 251(1), 13-13. [CrossRef]

- Tubin, S., Ahmed, M. M., & Gupta, S. (2018). Radiation and hypoxia-induced non-targeted effects in normoxic and hypoxic conditions in human lung cancer cells. Int J Radiat Biol, 94(3), 199-211. [CrossRef]

- Tubin, S., Ashdown, M., & Jeremic, B. (2019). Time-synchronized immune-guided SBRT partial bulky tumor irradiation targeting hypoxic segment while sparing the peritumoral immune microenvironment. Radiation oncology (London, England), 14(1), 220. [CrossRef]

- Tubin, S., Gupta, S., Grusch, M., Popper, H. H., Brcic, L., Ashdown, M. L., Khleif, S. N., Peter-Vörösmarty, B., Hyden, M., Negrini, S., Fossati, P., & Hug, E. (2020). Shifting the Immune-Suppressive to Predominant Immune-Stimulatory Radiation Effects by SBRT-PArtial Tumor Irradiation Targeting HYpoxic Segment (SBRT-PATHY). Cancers, 13(1). [CrossRef]

- Tubin, S., Khan, M. K., Salerno, G., Mourad, W. F., Yan, W., & Jeremic, B. (2019). Mono-institutional phase 2 study of innovative Stereotactic Body RadioTherapy targeting PArtial Tumor HYpoxic (SBRT-PATHY) clonogenic cells in unresectable bulky non-small cell lung cancer: profound non-targeted effects by sparing peri-tumoral immune microenvironment. Radiation oncology (London, England), 14(1), 212. [CrossRef]

- Tubin, S., Popper, H. H., & Brcic, L. (2019). Novel stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT)-based partial tumor irradiation targeting hypoxic segment of bulky tumors (SBRT-PATHY): improvement of the radiotherapy outcome by exploiting the bystander and abscopal effects. Radiation oncology (London, England), 14(1), 21. [CrossRef]

- Tubin, S., & Raunik, W. (2017). Hunting for abscopal and bystander effects: clinical exploitation of non-targeted effects induced by partial high-single-dose irradiation of the hypoxic tumour segment in oligometastatic patients. Acta Oncol, 56(10), 1333-1339. [CrossRef]

- Tudor, M., Gilbert, A., Lepleux, C., Temelie, M., Hem, S., Armengaud, J., Brotin, E., Haghdoost, S., Savu, D., & Chevalier, F. (2021). A proteomic study suggests stress granules as new potential actors in radiation-induced bystander effects. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(15), 7957-7957. [CrossRef]

- U.S.NLM. ClinicalTrials.gov. Retrieved Jan. 4, 2024 from https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=&term=FLASH+radiation&cntry=&state=&city=&dist=&Search=Search.

- U.S.NLM. ClinicalTrials.gov. Retrieved Feb. 16, 2024 from https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=&term=microbeam+radiotherapy&cntry=&state=&city=&dist=&Search=Search.

- U.S.NLM. (2008a, February 21, 2021). Haploidentical Stem Cell Transplantation in Neuroblastoma. ClinicalTrials.gov. Retrieved Feb.19, 2024 from https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00790413?term=radiation+bystander+effect&draw=2&rank=4.

- U.S.NLM. (2008b, February 27, 2014). Patients Overexposed for a Prostate Adenocarcinoma (EPOPA). ClinicalTrials.gov. Retrieved Feb.19, 2024 from https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00773656?term=radiation+bystander+effect&draw=2&rank=2.

- U.S.NLM. (2018, April 6, 2021). Phase II High Risk Prostate Cancer Trial Using Gene & Androgen Deprivation Therapies, Radiotherapy, & Surgery. ClinicalTrials.gov. Retrieved Feb.19, 2024 from https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03541928?term=radiation+bystander+effect&draw=2&rank=3.

- U.S.NLM. (2019, November 2, 2023). SBRT-based PArtial Tumor Irradiation of HYpoxic Segment (SBRT-PATHY). ClinicalTrials.gov. Retrieved Feb.19, 2024 from https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04168320?term=radiation+bystander+effect&draw=2&rank=1.

- U.S.NLM. (2020, September 7, 2023). Feasibility Study of FLASH Radiotherapy for the Treatment of Symptomatic Bone Metastases (FAST-01). ClinicalTrials.gov. Retrieved Feb.16, 2024 from https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04592887?term=FLASH+radiation&draw=2&rank=1.

- U.S.NLM. (2021, September 21, 2023). Irradiation of Melanoma in a Pulse (IMPulse). ClinicalTrials.gov. Retrieved Feb.16, 2024 from https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04986696?term=FLASH+radiation&draw=2&rank=4.

- U.S.NLM. (2022, March 22, 2023). FLASH Radiotherapy for the Treatment of Symptomatic Bone Metastases in the Thorax (FAST-02). ClinicalTrials.gov. Retrieved Feb.16, 2024 from https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05524064?term=FLASH+radiation&draw=2&rank=2.

- U.S.NLM. (2023, June 26, 2023). FLASH Radiotherapy for Skin Cancer (LANCE). ClinicalTrials.gov. Retrieved Feb.16, 2024 from https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05724875?term=FLASH+radiation&draw=2&rank=3.

- U.S.NLM. (2024). Search of: radiation bystander effect - List Results - ClinicalTrials.gov. ClinicalTrials.gov. Retrieved Feb.19, 2024 from https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=&term=radiation+bystander+effect&cntry=&state=&city=&dist=&Search=Search.

- USEPA. (2023, 15 Feb, 2023). Radiation Health Effects. United States Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved Jan. 3, 2024 from https://www.epa.gov/radiation/radiation-health-effects#:~:text=Exposure%20to%20very%20high%20levels,as%20cancer%20and%20cardiovascular%20disease.

- Verma, N., & Tiku, A. B. (2017). Significance and nature of bystander responses induced by various agents. Mutation Research/Reviews in Mutation Research, 773, 104-121. [CrossRef]

- Vogin, G., Merlin, J. L., Rousseau, A., Peiffert, D., Harlé, A., Husson, M., Hajj, L. E., Levitchi, M., Simon, T., & Simon, J. M. (2018). Absence of correlation between radiation-induced CD8 T-lymphocyte apoptosis and sequelae in patients with prostate cancer accidentally overexposed to radiation. Oncotarget, 9(66), 32680-32689. [CrossRef]

- Vozenin, M. C., De Fornel, P., Petersson, K., Favaudon, V., Jaccard, M., Germond, J. F., Petit, B., Burki, M., Ferrand, G., Patin, D., Bouchaab, H., Ozsahin, M., Bochud, F., Bailat, C., Devauchelle, P., & Bourhis, J. (2019). The Advantage of FLASH Radiotherapy Confirmed in Mini-pig and Cat-cancer Patients. Clin Cancer Res, 25(1), 35-42. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Zhang, J., Fu, J., Wang, J., Ye, S., Liu, W., & Shao, C. (2015). Role of ROS-mediated autophagy in radiation-induced bystander effect of hepatoma cells. Int J Radiat Biol, 91(5), 452-458. [CrossRef]

- Watson, G. E., Lorimore, S. A., Macdonald, D. A., & Wright, E. G. (2000). Chromosomal instability in unirradiated cells induced in vivo by a bystander effect of ionizing radiation. Cancer Res, 60(20), 5608-5611.

- Xie, Y., Tu, W., Zhang, J., He, M., Ye, S., Dong, C., & Shao, C. (2015). SirT1 knockdown potentiates radiation-induced bystander effect through promoting c-Myc activity and thus facilitating ROS accumulation. Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis, 772, 23-29. [CrossRef]

- Yakovlev, V. A. (2015). Role of nitric oxide in the radiation-induced bystander effect. Redox Biol, 6, 396-400. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H., Asaad, N., & Held, K. D. (2005). Medium-mediated intercellular communication is involved in bystander responses of X-ray-irradiated normal human fibroblasts. Oncogene, 24(12), 2096-2103. [CrossRef]

- Zeman, W., Curtis, H. J., & Baker, C. P. (1961). Histopathologic effect of high-energy-particle microbeams on the visual cortex of the mouse brain. Radiat Res, 15, 496-514.

- Zhang, D., Zhou, T., He, F., Rong, Y., Lee, S. H., Wu, S., & Zuo, L. (2016). Reactive oxygen species formation and bystander effects in gradient irradiation on human breast cancer cells. Oncotarget, 7(27), 41622-41636. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Ng, W. L., Wang, P., Tian, L. L., Werner, E., Wang, H., Doetsch, P., & Wang, Y. (2012). MicroRNA-21 Modulates the Levels of Reactive Oxygen Species Levels by Targeting SOD3 and TNFα. Cancer Research, 72(18), 4707-4707. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).