Submitted:

15 March 2025

Posted:

17 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

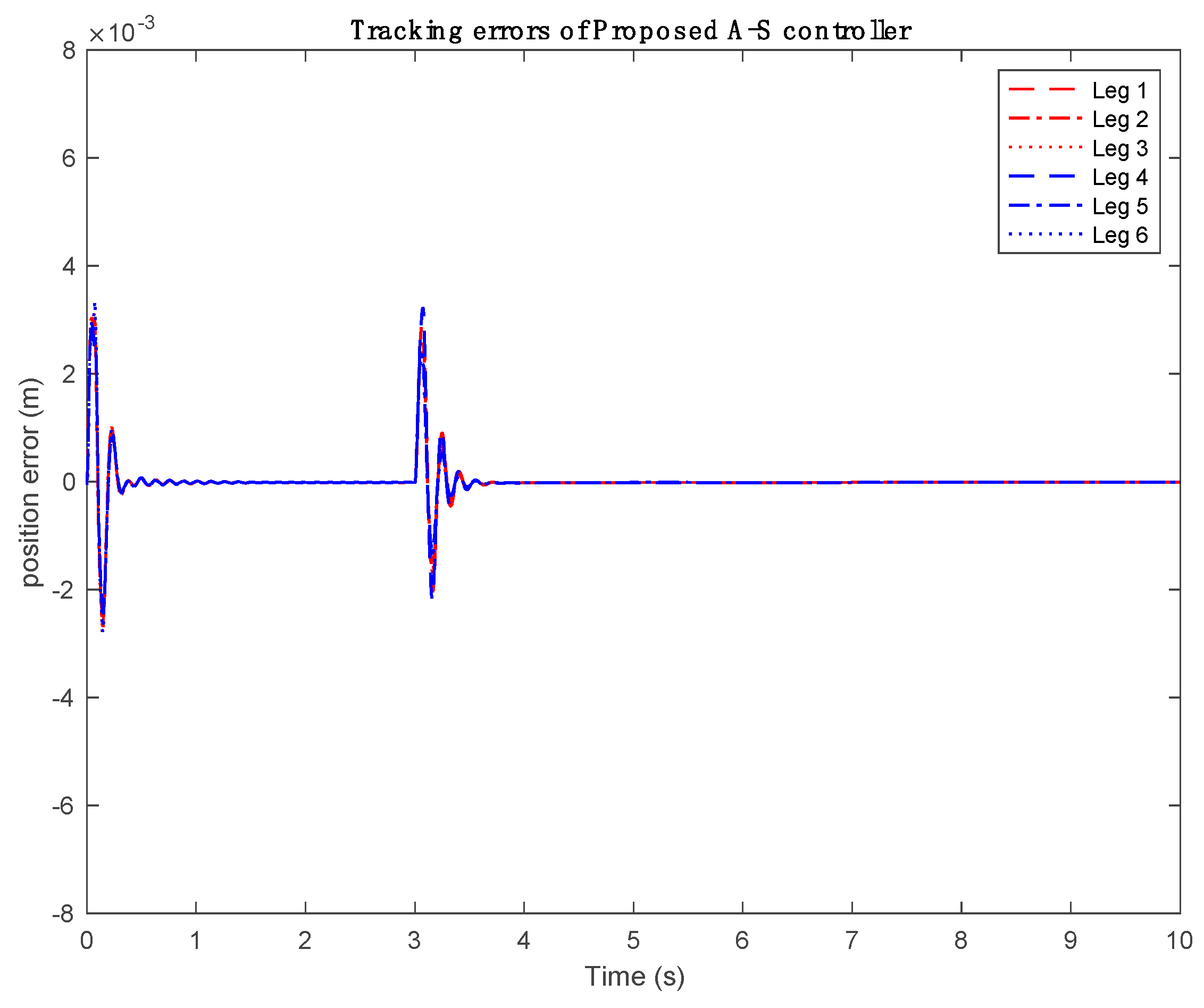

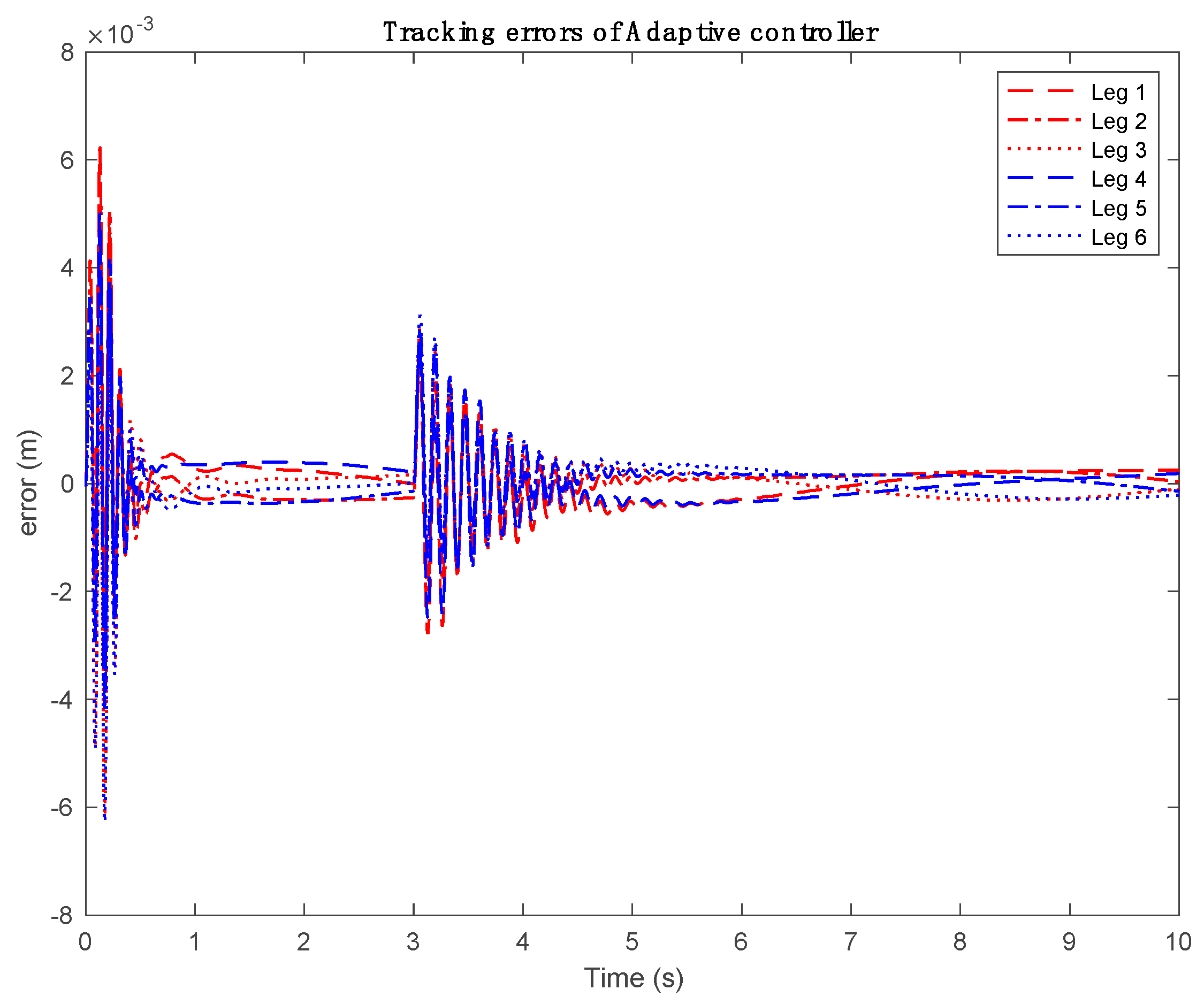

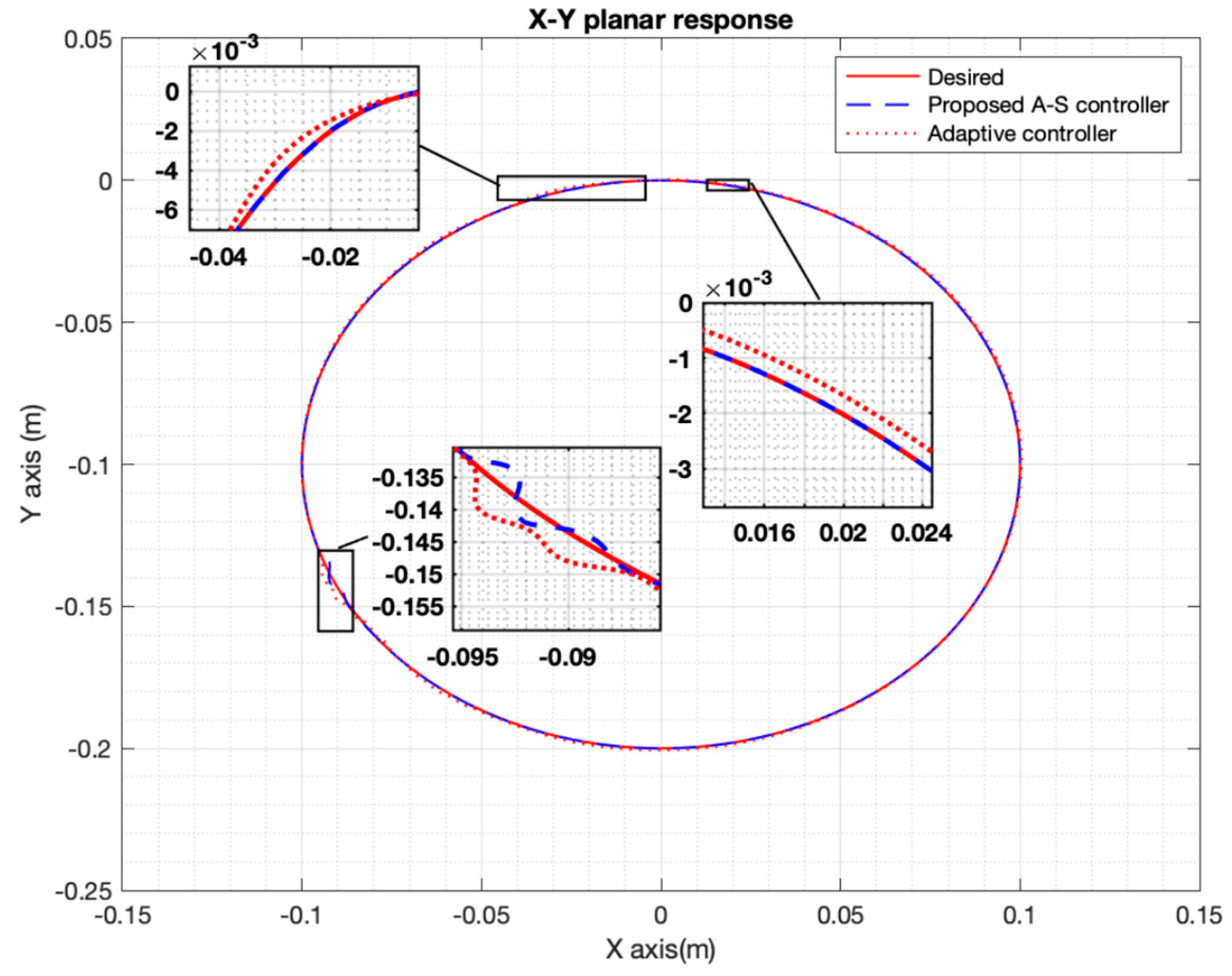

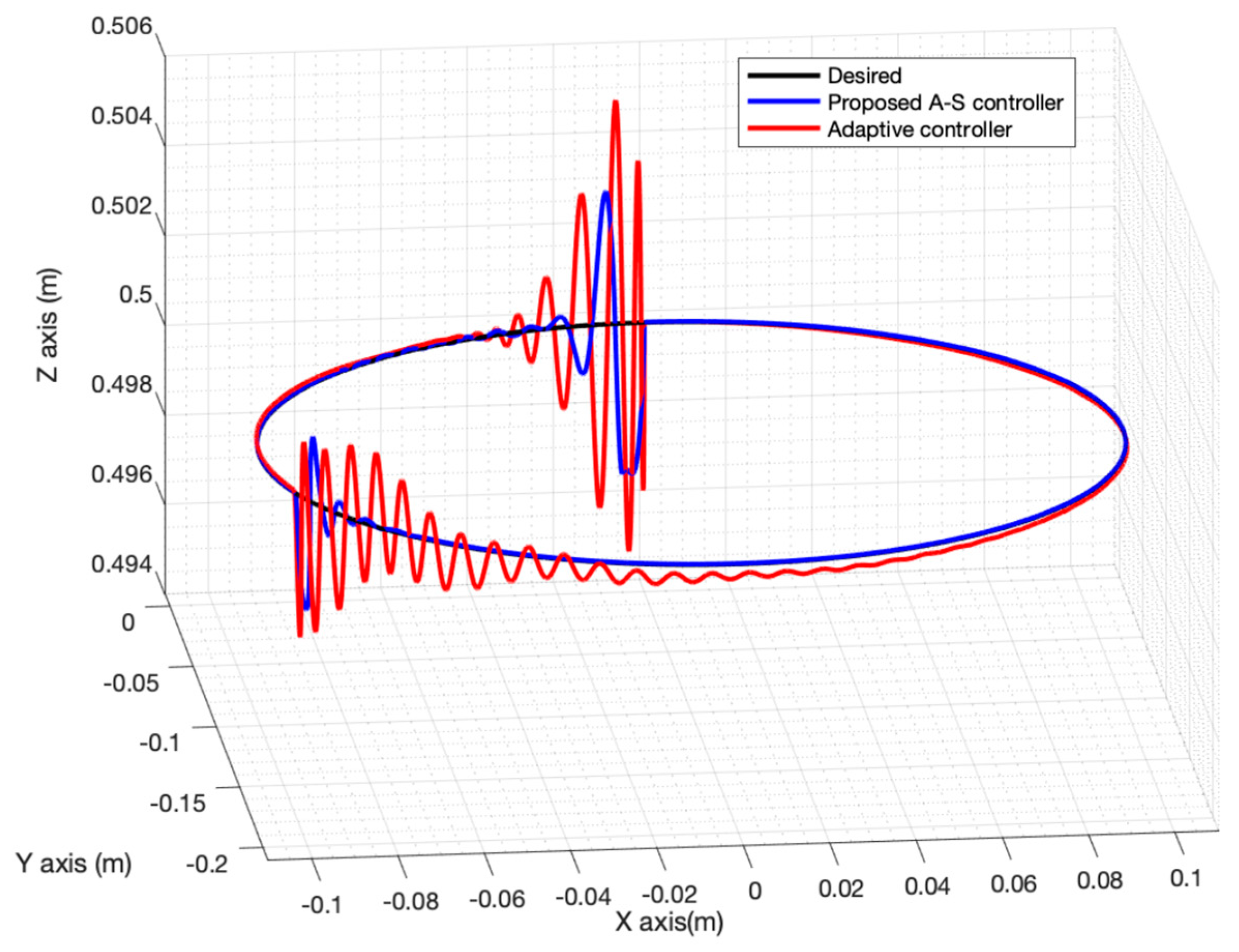

This paper presents a new decentralized adaptive control scheme for motion control of robot manipulators built based closed-kinematic chain mechanism (CKCM). By employing the synchronization technique and model reference adaptive control (MRAC) based on the Lyapunov direct method, the Decentralized Adaptive Synchronized Control (DASC) scheme is developed. The DASC scheme can ensure global asymptotic convergence of tracking errors while forcing all active joints to move in a predefined synchronous manner in the presence of uncertainties and sudden changes in payload. In addition, the control scheme has a simple structure that does not depend on the knowledge of the dynamic mathematical model of a robot manipulator resulting in computational efficiency of control scheme implementation. Results of computer simulation conducted to evaluate the performance of the control scheme applied to control the motion of a CKCM manipulator with 6 degrees of freedom are reported and discussed.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Synchronization Control

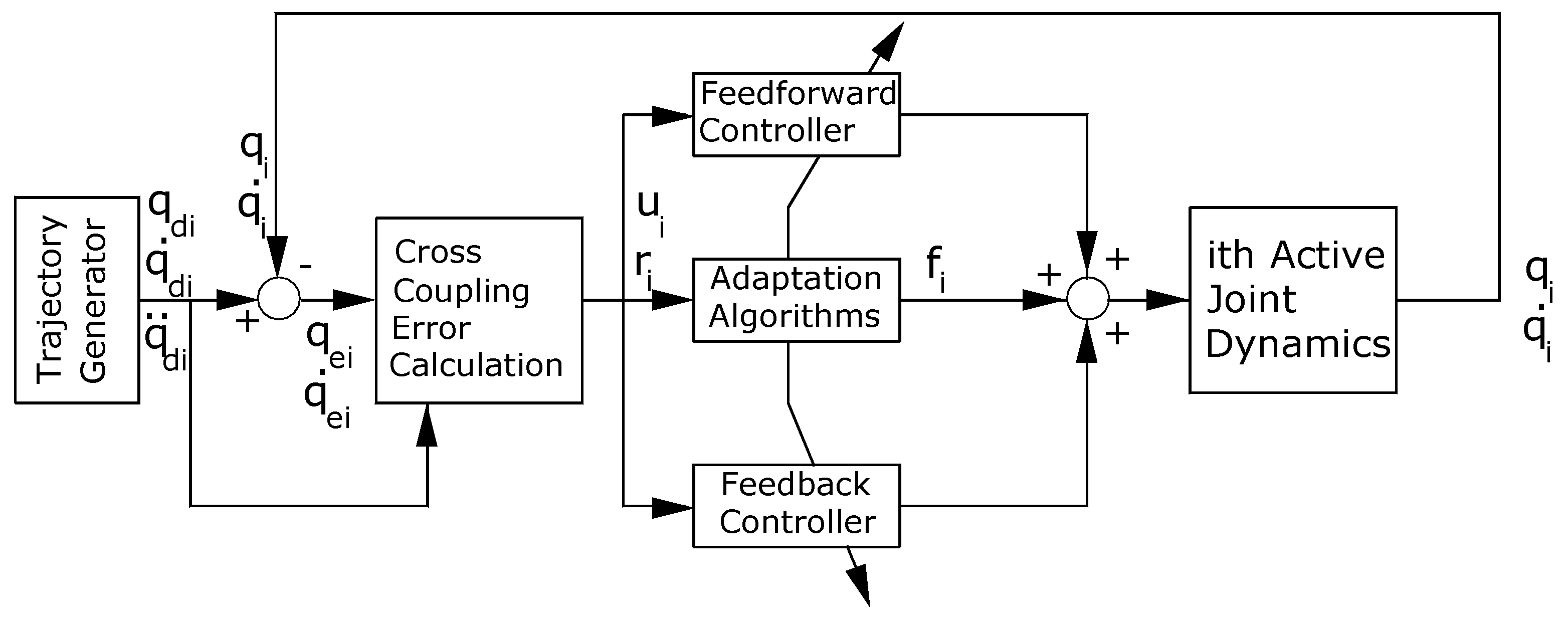

3. Development of the DASC Scheme

- The first term represents auxiliary signal to improve the tracking performance and partly compensate for disturbance

- The second term = represents the PID feedback controller

- The last term represent the feedforward controller

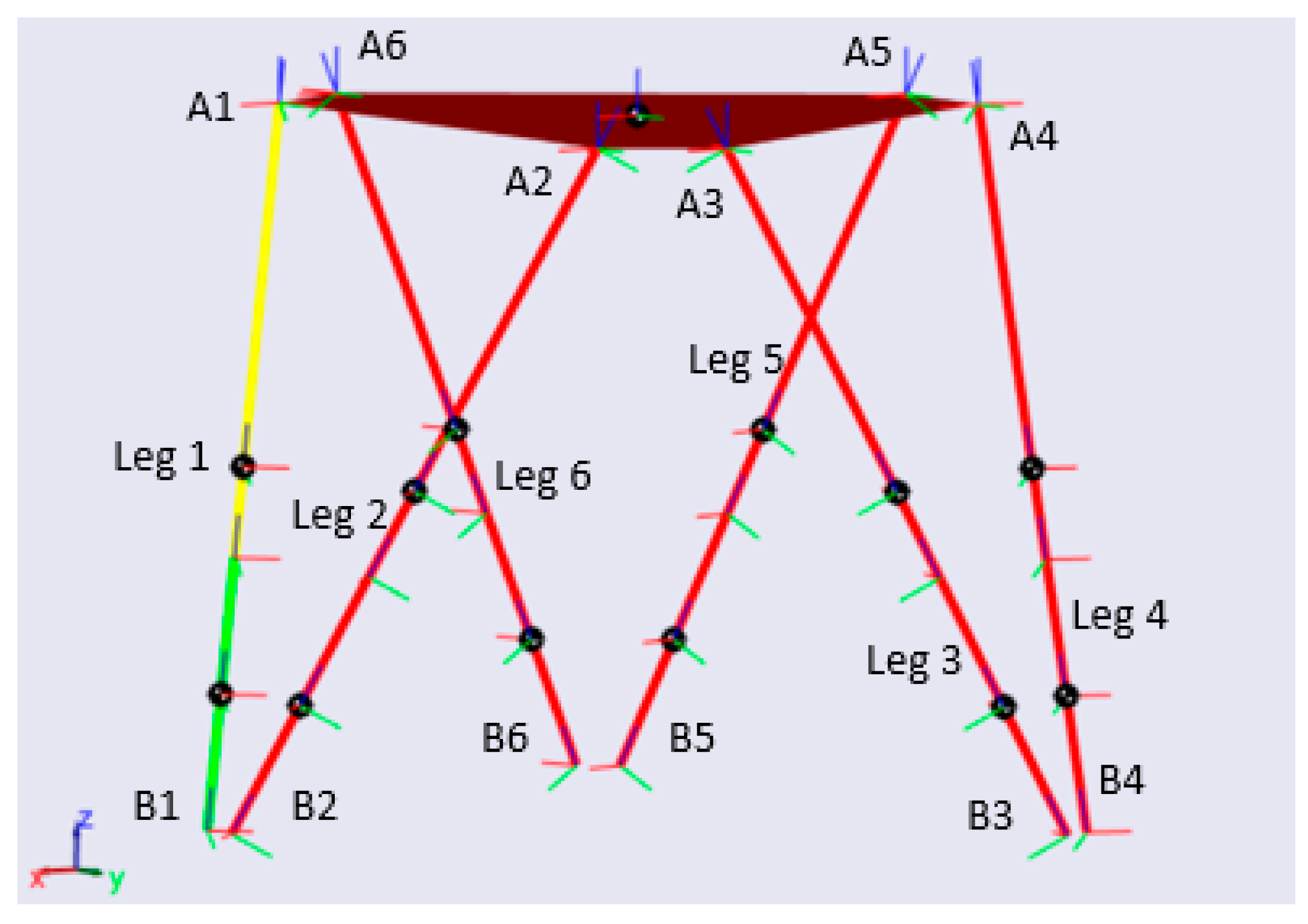

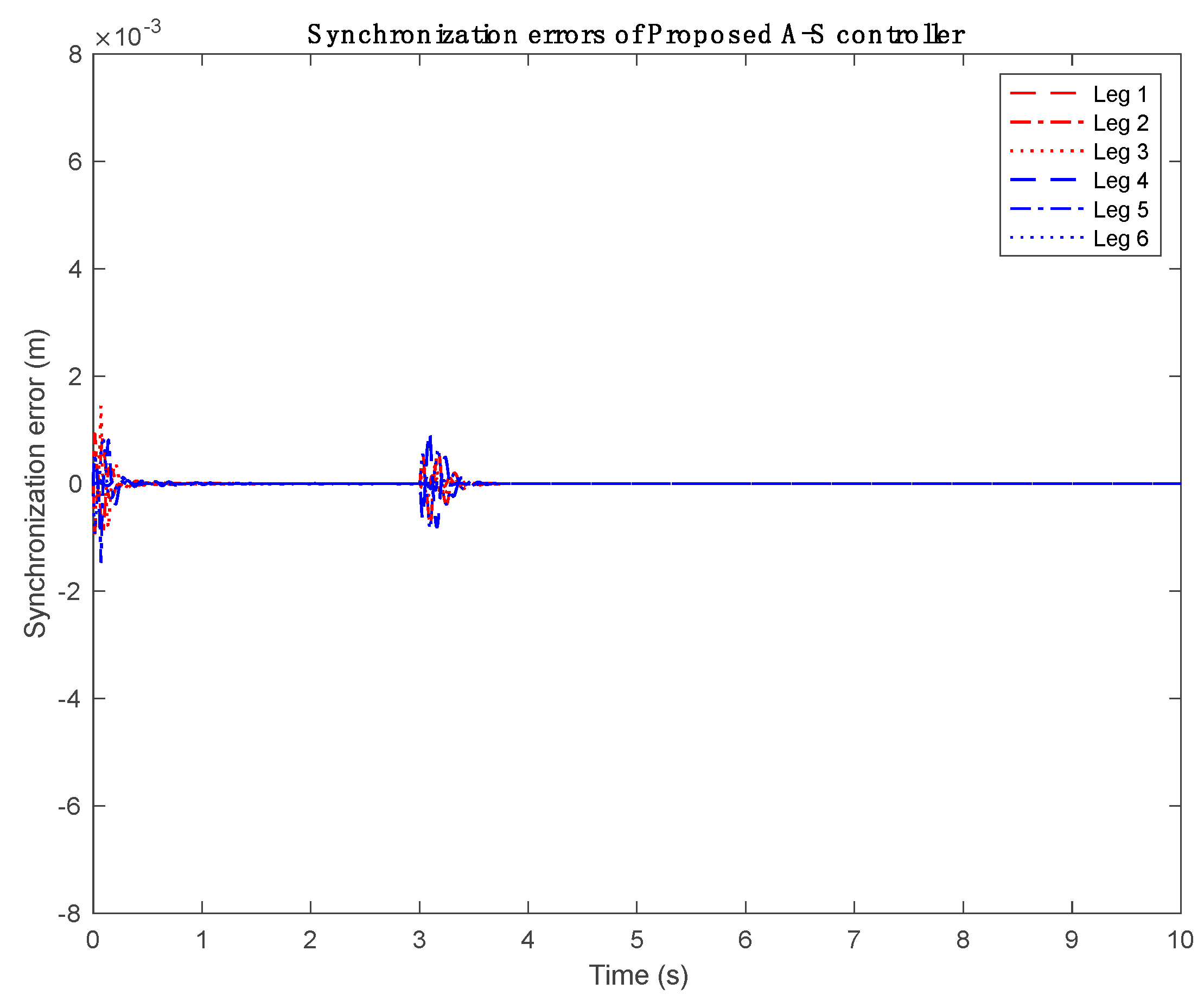

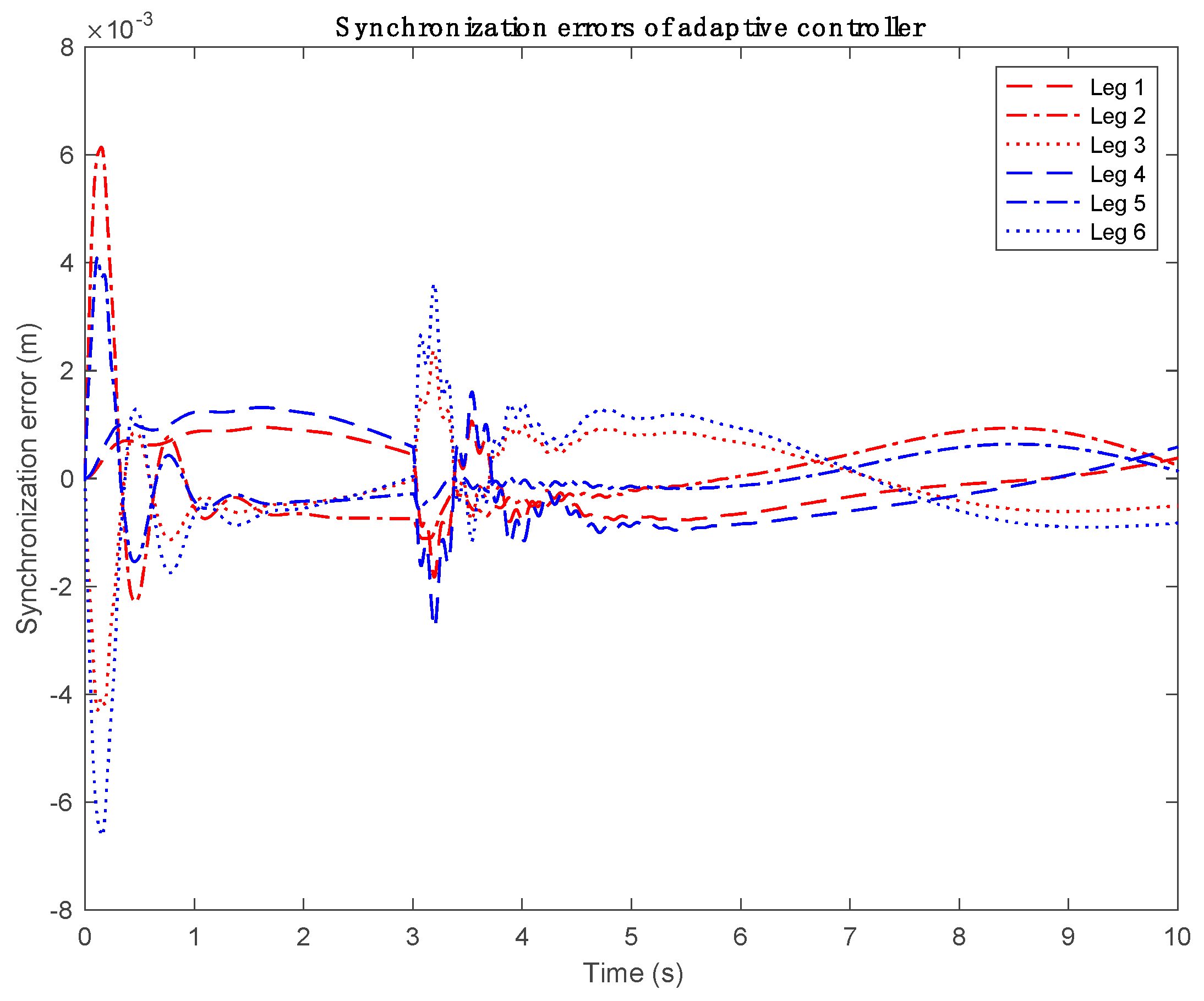

4. Computer Simulation Study

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Merlet, J. P. Parallel robots (Vol. 128). Springer Science & Business Media. 2006.

- Tsai, L. W. Robot analysis: the mechanics of serial and parallel manipulators. 1999, John Wiley & Sons.

- Stewart, D., A Platform with Six Degrees of Freedom, Proc. Institute of Mechanical Engineering, vol. 180, part 1, No. 5, pp. 371-386, 1965-1966.

- Dasgupta, B.; Mruthyunjaya, T. S. The Stewart platform manipulator: a review. Mechanism and machine theory. 2000, 35, 15–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, R.; Davila, V. S.; Perez, J. A. L. Control of robot manipulators in joint space. Springer Science & Business Media. 2006.

- Y. Koren, “Cross-coupled biaxial computer control for manufacturing systems”, Journal of Dynamic Systems Measurement and Control, 1980.

- Li, Y.; Nielsen, C. Position synchronized path following for a mobile robot and manipulator. 52nd IEEE Conference on Decision and Control, 2013, pp. 3541-3546.

- Do, K. D. Synchronization motion tracking control of multiple underactuated ships with collision avoidance. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics. 2016, 63, 2976–2989. [Google Scholar]

- Bouteraa, Y.; Ghommam, J.; Poisson, G.; Derbel, N. Distributed synchronization control to trajectory tracking of multiple robot manipulators. Journal of Robotics. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Sun, D. A synchronization control strategy for multiple robot systems using shape regulation technology. 2008 7th World Congress on Intelligent Control and Automation. 2008, pp. 467-472.

- Shang, W.; Cong, S.; Ge, Y. Coordination motion control in the task space for parallel manipulators with actuation redundancy. IEEE Transactions on Automation Science and Engineering. 2012, 10, 665–673. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, D.; Wang, C.; Shang, W.; Feng, G. A synchronization approach to trajectory tracking of multiple mobile robots while maintaining time-varying formations. IEEE Transactions on Robotics 2009, 25, 1074–1086. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, D.; Mills, J. K. Adaptive synchronized control for coordination of two robot manipulators. In Proceedings 2002 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation. 2002, (Cat. No. 02CH37292) (Vol. 1, pp. 976-981).

- Zhu, W. H. On adaptive synchronization control of coordinated multi robots with flexible/rigid constraints. IEEE Transactions on Robotics. 2005, 21, 520–52. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H. Task-space synchronization of networked robotic systems with uncertain kinematics and dynamics. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control. 2013, 58, 3169–3174. [Google Scholar]

- Long, Y.; Yang, X. J. Robust adaptive fuzzy sliding mode synchronous control for a planar redundantly actuated parallel manipulator. 2012 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Biomimetics (ROBIO) 2012, pp. 2264-2269.

- Fuh, C. C.; Tsai, H. H.; Huang, C. C. A fuzzy cross-coupled linear quadratic regulator for improving the contour accuracy of bi-axis machine tools. In Proceedings of the 48h IEEE Conference on Decision and Control (CDC) held jointly with 2009 28th Chinese Control Conference 2009, pp. 4156-4161.

- Zhao, D.; Zhu, Q.; Li, N.; Li, S. Neural networked based synchronized control for multiple robotic manipulators. 10th IEEE International Conference on Control and Automation (ICCA) 2013, pp. 1950-1955.

- Le, D. K.; Ahn, K. K. Synchronization algorithm for controlling 3-R planar parallel pneumatic artificial muscle robot. 2011 11th International Conference on Control, Automation and Systems 2011, pp. 1588-1593.

- Su, Y. X.; Sun, D.; Ren, L.; Wang, X.; Mills, J. K. Nonlinear PD synchronized control for parallel manipulators. In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE international conference on robotics and automation 2005, pp. 1374-1379.

- Sun, D.; Tong, M. C. (2009). A synchronization approach for the minimization of contouring errors of CNC machine tools. IEEE transactions on automation science and engineering 2009, 6, 720–729. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, D.; Li, S.; Gao, F. Fully adaptive feedforward feedback synchronized tracking control for Stewart Platform systems. International Journal of Control, Automation, and Systems 2008, 6, 689–701. [Google Scholar]

- Seraji, H. Decentralized adaptive control of manipulators: theory, simulation, and experimentation. IEEE Transactions on Robotics and Automation 1989, 5, 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Searcoid, M. Metric spaces. Springer Science & Business Media 2006.

- J. Craig, Robotics: Mechanics and Control, Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA, 1986.

- Khalil, H. K.; Grizzle, J. W. Nonlinear systems 2002; Vol. 3. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice hall.

- Slotine, J. J. E.; Li, W. On the adaptive control of robot manipulators. The international journal of robotics research 1987, 1987 6, 49–5. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, D.; Shao, X.; Feng, G. A model-free cross-coupled control for position synchronization of multi-axis motions: theory and experiments. IEEE Transactions on Control Systems Technology 2007, 15, 06–314. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, D. Position synchronization of multiple motion axes with adaptive coupling control. Automatic 2003, 39, 997–1005. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, D.; Mills, J.K. Adaptive Synchronized Control for Coordination of Multirobot Assembly Tasks. IEEE Transactions on Robotics and Automation 2002, 18, 498–510. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Lu; Xingzhuang Zhao. "Coupled Dynamics of Vehicle-Bridge Interaction System Using High Efficiency Method." Advances in Civil Engineering 2021, 1-22.

- Yanna, Y.; Huiying, W.; Lu, S.; Wei, H. The Influence of Road Geometry on Vehicle Rollover and Skidding. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 1-17, 1648. [Google Scholar]

| Plant parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Base radius (m) | 0.36 |

| Platform radius(m) | 0.27 |

| Initial height (m) | 0.5 |

| Base offset angle (deg) | 2.5 |

| Platform offset angle (deg) | 10 |

| Mass of the platform (kg) | 4.92 |

| Mass of the leg cylinder (kg) | 10.29 |

| Inertia coefficient of the platform, Ixx (kg*m2) | 0.09 |

| Inertia coefficient of the platform, Iyy (kg*m2) | 0.09 |

| Inertia coefficient of the platform, Izz (kg*m2) | 0.18 |

| Seraji Controller |

DASC Controller |

|

|---|---|---|

| 0.508 | 0.0226 | |

| 0.501 | 0.0284 | |

| 0.28 | 0.0947 | |

| 0.379 | 0.0988 | |

| 0.323 | 0.0905 | |

| 0.318 | 0.0909 | |

| 0.375 | 0.0972 | |

| 0.331 | 0.0832 | |

| 0.341 | 0.0860 | |

| 0.5109 | 0.0021 | |

| 0.6637 | 0.0122 | |

| 0.6245 | 0.0156 | |

| 0.7342 | 0.0176 | |

| 0.3961 | 0.0117 | |

| 0.8946 | 0.0211 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).