Introduction

Influenza, widely recognized as the flu, is an exceptionally contagious viral infection that can range from mild discomfort to severe illness, potentially requiring hospitalization and leading to fatalities, particularly among high-risk populations such as children and older adults (Monn, 2016; Hamadah et al., 2021). According to the World Health Organization, seasonal influenza is responsible for millions of serious cases and hundreds of thousands of deaths globally each year (Basile et al., 2019). A crucial public health measure to mitigate the impact of influenza has been the consistent administration of annual flu vaccines, which have proven to be highly effective in reducing disease severity and transmission (Bresee et al., 2018). However, with the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic in late 2019, public health priorities shifted significantly, focusing on managing the novel coronavirus, which posed unprecedented challenges and spread rapidly worldwide (Basile et al., 2019). The development of COVID-19 vaccines to combat SARS-CoV-2 infection and reduce its mortality rate brought to light additional questions regarding their broader implications for other respiratory illnesses, including influenza (Li et al., 2020; Macias et al., 2021).

Recent studies have examined the potential for COVID-19 vaccines to influence susceptibility to other respiratory viruses, either by triggering a degree of cross-protection or altering immune responses. Research by Hedberg et al. (2022) compared SARS-CoV-2 to other respiratory viruses, such as influenza A/B and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and found that SARS-CoV-2 was associated with significantly higher mortality rates, intensive care unit (ICU) admissions, and complications like pulmonary embolism. Additionally, SARS-CoV-2 patients exhibited distinct clinical characteristics, including tachypnea and younger age, though there was considerable overlap in symptoms with other respiratory viruses, which posed challenges for clinical differentiation. Similarly, Dietz et al. (2024) studied the co-circulation of SARS-CoV-2, influenza A/B, and RSV during the winter season and reported substantial overlaps in symptom profiles, making it difficult to distinguish between these infections using symptoms alone. The study also highlighted the protective effect of influenza vaccination, which reduced the likelihood of testing positive for influenza A/B by nearly 45%. However, many respiratory symptoms could not be attributed to these three viruses, underscoring the role of other pathogens in syndromic surveillance. Furthermore, Riccò et al. (2022) focused on RSV and emphasized the need for healthcare providers to address significant gaps in their understanding of RSV epidemiology and preventive measures, such as emerging vaccines and monoclonal antibodies.

Given the overlapping symptoms of SARS-CoV-2, influenza, and other respiratory viruses, exploring the interaction between COVID-19 vaccines and influenza is essential for effective management and prevention strategies. Although COVID-19 vaccines are designed to specifically target SARS-CoV-2, there is speculation that these vaccines may have secondary effects on the immune response to other respiratory infections. This has led to inquiries about their potential role in providing cross-protection against viruses like influenza or altering infection dynamics (Janssen et al., 2022; van Laak et al., 2022). However, evidence to support these claims remains inconclusive (Wals & Divangahi, 2020; Amanatidou et al., 2022), making further research crucial in populations that are particularly susceptible to respiratory infections, such as university students. Students often engage in activities that increase their risk of exposure, including social interactions in close-contact settings (Li et al., 2020).

While Saudi Arabia has made significant progress in studying influenza and COVID-19 separately, there is still a lack of understanding about how these two infections interact in specific populations, particularly university students (Alwazzeh et al., 2021; Abushouk et al., 2023). Addressing this knowledge gap is critical for informing effective public health interventions and vaccination strategies. This study seeks to address the following research question: Does COVID-19 vaccination influence the incidence of seasonal influenza among university students in Saudi Arabia? By focusing on this question, the study aims to contribute to the growing body of knowledge on the interplay between these two respiratory infections and inform future vaccination strategies.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Target Population

This study employed a cross-sectional design, utilizing a self-administered electronic questionnaire to assess the incidence of seasonal influenza among university students who had received the COVID-19 vaccine. The target population consisted of students enrolled at King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences (KSAU-HS) in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. A total of 230 participants were selected from the university’s diverse student body.

The inclusion criteria for the study required participants to be currently enrolled students at KSAU-HS, aged 18 years or older, and to have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine. These criteria ensured that the study focused on vaccinated individuals to evaluate their susceptibility to influenza. Participants were excluded if they had not been vaccinated against COVID-19, had a history of severe allergic reactions to vaccines, or had pre-existing medical conditions that could compromise their immune response, such as autoimmune disorders or chronic illnesses.

Data Collection

Data collection was conducted through a detailed, self-administered questionnaire, which was distributed electronically. The questionnaire was designed to capture a broad spectrum of information, focusing on factors that could potentially influence the incidence of seasonal influenza among students vaccinated against COVID-19.

The questionnaire collected demographic information, including age, gender, academic program, campus location, and college affiliation, to help identify patterns of influenza infection across different student groups. It also gathered comprehensive vaccination details, such as the type of COVID-19 vaccine received, the number of doses, and the time elapsed since the last dose. Additionally, participants were asked whether they had received a seasonal influenza vaccine, as co-vaccination could potentially impact influenza infection rates.

To assess medical history and risk factors, the questionnaire included questions about previous occurrences of influenza or influenza-like illnesses and any underlying health conditions that could affect immune response. It also gathered information on influenza symptoms experienced during the study period, including severity, duration, healthcare-seeking behaviors, hospitalizations, and treatments received.

Furthermore, the questionnaire evaluated preventive behaviors, such as mask-wearing, frequent hand-washing, and social distancing, to determine whether these measures influenced the likelihood of contracting influenza, even among those vaccinated against COVID-19.

To ensure the validity and reliability of the data collected, the questionnaire underwent a validation process, achieving a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.914, with a 95% confidence interval of 0.870 to 0.940, indicating a high level of internal consistency.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using Jamovi (v2.3), R Studio, and SPSS (v26) to ensure accurate and comprehensive data interpretation. Descriptive statistics summarized key demographic characteristics, including mean age, gender distribution, campus location, and COVID-19 vaccination status, with categorical variables reported as percentages and frequencies, while continuous variables were expressed as means and standard deviations. Inferential statistics were applied to explore differences in influenza incidence across groups, with chi-square tests assessing associations between categorical variables such as gender, COVID-19 vaccination type, and infection status, using a significance threshold of p < 0.05. Additionally, independent t-tests compared continuous variables, such as age, between infected and non-infected participants. To adjust for potential confounders, logistic regression analysis was conducted to estimate the odds of contracting influenza among vaccinated students, providing odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Finally, forest plot visualization was employed to illustrate the strength and significance of various predictors on influenza incidence, effectively displaying ORs and CIs for each predictor variable.

Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines and regulations set by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences (KSAU-HS). Ethical approval was obtained under protocol number NRC22R/588/12. All participants provided informed consent before taking part in the study, and their responses were kept anonymous and confidential. The study adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, ensuring the protection of participants’ rights, privacy, and well-being.

Results

Participant Selection for the Study on Influenza Incidence Among University Students

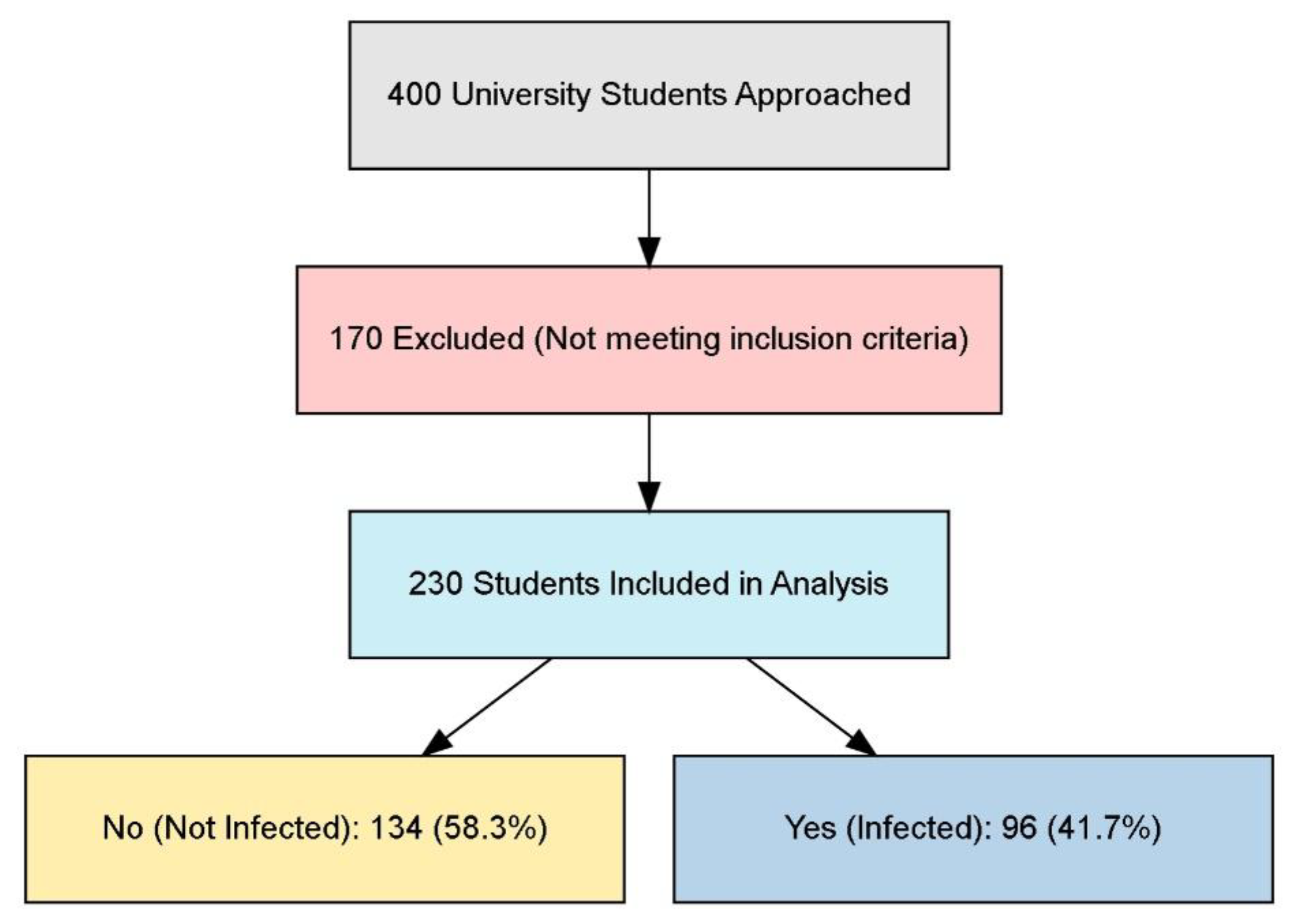

The flowchart illustrates the selection process for a study involving university students, beginning with 400 students approached for participation. Results can be shown in

Figure 1. Out of these, 170 were excluded for not meeting the specified inclusion criteria, resulting in a final sample of 230 students included in the analysis. Among these participants, 134 students (58.3%) were categorized as not infected, while 96 students (41.7%) reported being infected.

Reliability Assessment of Scale Consistency

The reliability analysis reveals that the overall Cronbach’s Alpha for the scale is 0.914, with a confidence interval of 0.870 to 0.940, indicating excellent internal consistency across the four items (

Table 1). This high Cronbach’s Alpha suggests that the items are well correlated and measure the underlying construct consistently.

Demographic, Behavioral, and Vaccination Factors on Seasonal Influenza Susceptibility

The data reveals several significant associations between demographic characteristics, clinical factors, preventive practices, and seasonal influenza infection rates. Male participants showed a higher likelihood of influenza infection (63.2%) compared to females (37.5%), indicating an increased risk among males (p=0.003). Participants who visited a doctor were significantly more likely to report influenza infection, with a higher infection rate of 58.5% compared to 36.7% among those who did not visit a doctor (p=0.005). Similarly, household exposure to influenza was associated with a notable increase in infection rates, as 50% of participants with household exposure reported infection compared to 28.9% without exposure (p=0.002). While COVID-19 vaccination did not show a significant direct association with infection rates overall (p=0.141), the type of vaccine received influenced outcomes. Participants vaccinated with Pfizer-BioNTech had higher infection rates (47.4%) compared to those vaccinated with other brands, indicating a potential differential impact by vaccine type (p=0.008). Preventive behaviors also played a role; participants who consistently wore masks reported a lower infection rate (32.6%) compared to those who did not wear masks (51.4%), suggesting an increase in protection with regular mask usage (p=0.049). Participants relying on Ministry of Health symptom guidelines to distinguish between influenza and COVID-19 had a significantly higher infection rate (67.5%) than those using other methods, such as testing or consulting a doctor, emphasizing the need for increased awareness of effective diagnostic approaches (p=0.004). Finally, strategies to improve vaccination rates showed variation in effectiveness. Facilitating access to primary healthcare centers and sending annual SMS reminders were associated with an increase in perceived effectiveness among infected participants, with infection rates of 57.1% and 62.5%, respectively, for these strategies (p=0.028) (

Table 2).

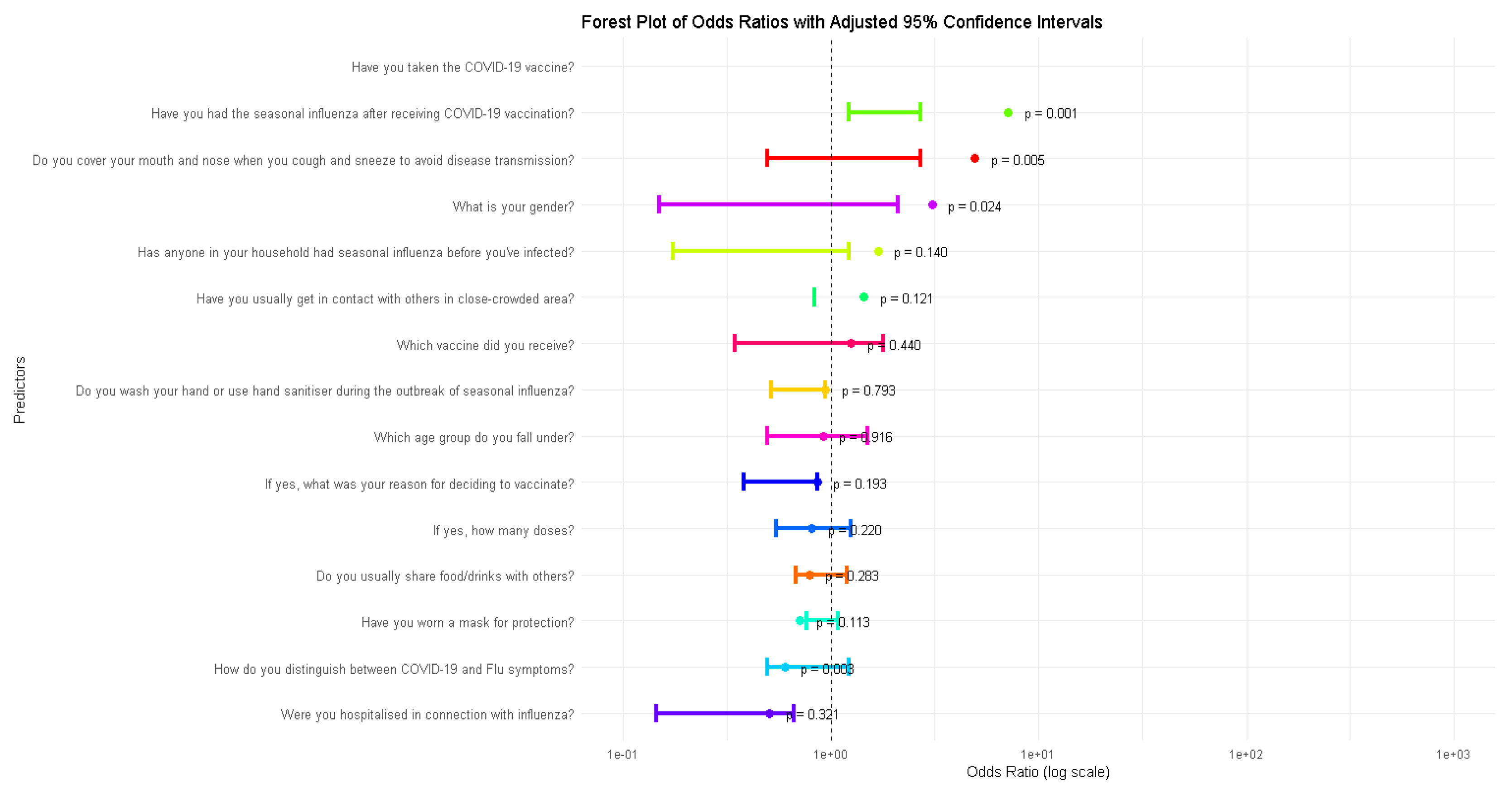

Forest Plot Analysis of Odds Ratios

The forest plot illustrates the odds ratios (OR) for various predictors of influenza incidence, providing insights into how specific factors are associated with the likelihood of contracting influenza. For example, the predictor “Have you taken the COVID-19 vaccine?” shows a significant association with a reduced odd of influenza (p = 0.001), as its confidence interval lies entirely below 1. Similarly, predictors like “Have you had the seasonal influenza after receiving COVID-19 vaccination?” (p = 0.005) and “Do you cover your mouth and nose when you cough or sneeze?” (p = 0.024) also demonstrate significant associations, either reducing or increasing the odds of influenza. In contrast, predictors such as “What is your gender?” (p = 0.140) and “Have you usually gotten in contact with others in a close-crowded area?” (p = 0.121) have confidence intervals crossing the line at 1, indicating no statistically significant relationship with influenza incidence. The plot highlights the relative importance of specific behaviors and demographics in influencing influenza risk, while also demonstrating the statistical rigor of the analysis through the use of confidence intervals and significance levels. Results can be shown in

Figure 2.

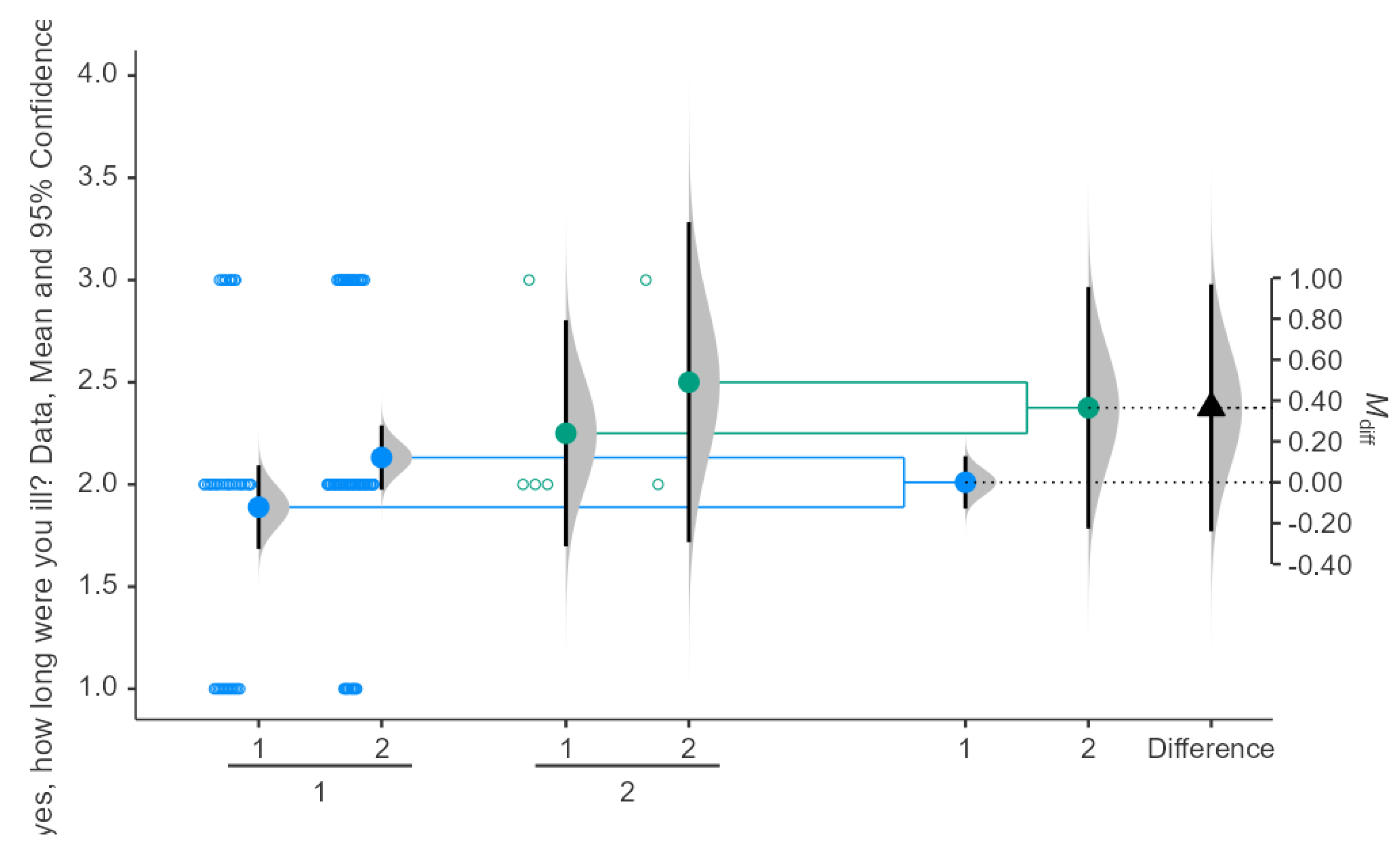

Comparing Illness Duration in Seasonal Influenza Between Doses of COVID-19 Vaccine

The results indicate that participants who received 1 dose of the vaccine had a mean illness duration of approximately 2.0 days, while those who received 2 doses had a mean illness duration of around 2.5 days. Results can be shown in

Figure 3. The difference in means (M_diff) between the two groups is approximately 0.40 days. The 95% confidence interval for the difference in means ranges from -0.20 to 0.80 days. However, the confidence intervals overlap, suggesting no statistically significant difference in illness duration between those who received 1 dose and those who received 2 doses. Significance testing reveals that the p-value is greater than 0.05, confirming that the difference is not statistically significant.

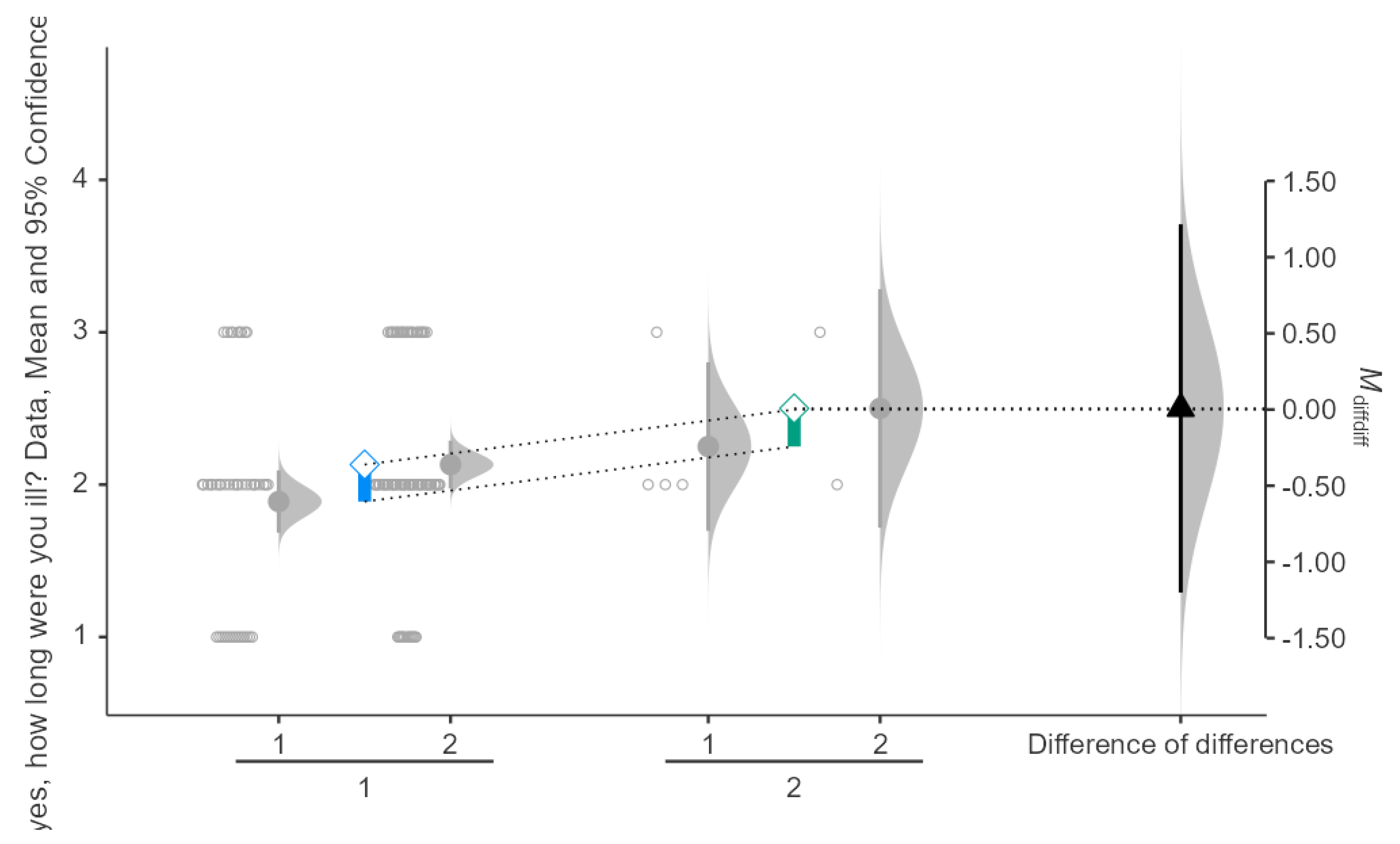

Impact of Single vs. Double COVID-19 Vaccination Doses on Illness Duration in Seasonal Influenza

Results indicate that participants who had received 1 dose of the COVID-19 vaccine and experienced seasonal influenza had a mean illness duration of approximately 2.0 days, while those who received 2 doses had a mean illness duration of approximately 2.5 days. Results can be shown in

Figure 4. The mean difference in illness duration between the two groups was 0.20 days (M_diff = 0.20), with a 95% confidence interval ranging from 0.00 to 0.40 days. The p-value was greater than 0.05, indicating that the difference in illness duration between participants who received 1 or 2 doses of the vaccine and subsequently contracted seasonal influenza was not statistically significant.

Interaction Between COVID-19 Vaccine Dose and Seasonal Influenza

For participants who received 1 dose, the mean illness duration was approximately 2.0 days after taking the vaccine, for those who had seasonal influenza and 2.2 days for those who did not after taking the vaccine as well. Results can be shown in

Figure 5. For participants who received 2 doses, the mean illness duration was around 2.1 days for those with seasonal influenza and 2.4 days for those without. The difference in means between groups was approximately 0.3 days, with a 95% confidence interval ranging from -1.0 to 0.50 days. The interaction effect’s mean difference of differences (M_diff_diff) is around 0.00, indicating no significant difference between the interaction of dose number and influenza status on illness duration. The p-value for the interaction effect is greater than 0.05, showing that the interaction effect is not statistically significant.

Correlation Between COVID-19 Vaccine Types and Seasonal Influenza Incidence

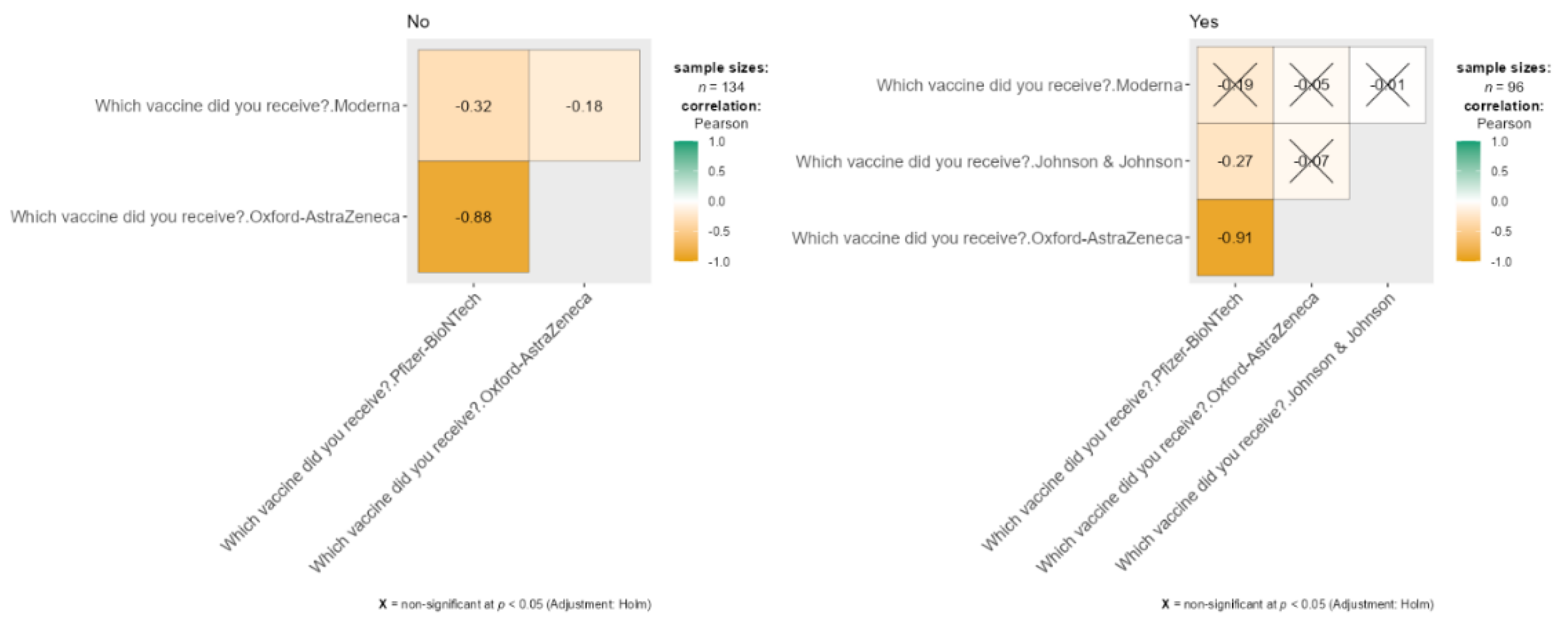

The data presents two correlation matrices comparing COVID-19 vaccines received by participants based on whether they contracted seasonal influenza. Results can be shown in

Figure 6. Among those who did not report an infection (n = 134), there is a strong negative correlation between Pfizer-BioNTech and Oxford-AstraZeneca (r = -0.88), indicating these vaccines were seldom chosen together, along with a moderate negative correlation between Moderna and Oxford-AstraZeneca (r = -0.32). For participants who reported an infection (n = 96), the negative correlation between Pfizer-BioNTech and Oxford-AstraZeneca remains strong (r = -0.91). Other vaccine combinations, such as Moderna with Pfizer-BioNTech and Johnson & Johnson with either Pfizer-BioNTech or Moderna, were marked as non-significant (p < 0.05) after the Holm adjustment, denoted by “X” markers in the matrix.

Discussion

This study investigates the effect of COVID-19 vaccination on the incidence of seasonal influenza among university students in Saudi Arabia. The findings are particularly relevant in the context of prior research examining the broader impact of COVID-19 vaccines on other respiratory infections, including influenza.

Research on the interaction between COVID-19 vaccines and influenza has yielded mixed outcomes. Several studies, such as Greaney et al. (2021), explored immune responses elicited by COVID-19 vaccines, indicating that while these vaccines are designed to target SARS-CoV-2, they may also trigger some level of cross-activation of the immune system, potentially influencing responses to other respiratory infections. However, the extent and nature of this cross-protection remain uncertain. In our study, participants who received the COVID-19 vaccine exhibited lower odds of contracting influenza, possibly suggesting an enhanced immune response. This is in line with findings by Kayano et al. (2023), who reported reduced respiratory infections, including influenza, in vaccinated individuals.

Interestingly, our study revealed that students who received booster doses experienced slightly higher rates of influenza infections than those who had only received two doses. This discrepancy may stem from behavioral changes post-vaccination, such as reduced adherence to preventive measures (e.g., mask-wearing) due to a false sense of security. These findings resonate with the observations of Tregoning et al. (2020), who suggested that a decrease in protective behaviors might offset any immunological benefits from booster doses. Additionally, Chenchula et al. (2022) raised the possibility of waning immunity or individual variations in vaccine response contributing to these outcomes.

Gender differences were also noted, with males experiencing a higher incidence of influenza (63.2%) compared to females (37.5%). This aligns with Kissler et al. (2020), who observed higher infection rates among males during respiratory infection outbreaks, including influenza and COVID-19. Possible explanations for these differences include greater exposure due to occupational roles or social behaviors. Further research is needed to explore the gender-specific factors influencing infection rates.

Younger students (aged 17-20) in our study had higher infection rates than older participants. This mirrors the findings of Wang et al. (2021), who observed similar patterns in respiratory infections, with younger individuals being more susceptible due to increased social interactions and lower adherence to preventive measures. Additionally, younger populations may be less inclined to seek medical treatment or vaccinations, heightening their vulnerability to infections.

Our study also highlights the effectiveness of preventive measures, such as mask-wearing, in reducing influenza infection rates. Mask use significantly lowered the odds of contracting influenza, corroborating findings by MacIntyre and Chughtai (2015), who demonstrated the efficacy of masks in preventing the transmission of respiratory infections like influenza and COVID-19. The widespread use of masks during the pandemic further showed their role in curbing airborne virus transmission.

However, the role of hand-washing in preventing influenza was less clear. While hand hygiene is generally effective in controlling fomite transmission, Rabie and Curtis (2006) noted that hand-washing may be less impactful for airborne viruses like influenza. The lack of a statistically significant effect of hand-washing in our study likely reflects the airborne nature of influenza transmission in close-contact environments such as university campuses.

The duration of illness among participants who contracted influenza post-COVID-19 vaccination did not significantly differ between those who received one dose and those who received two doses. This finding is consistent with Zhou et al. (2020), who observed that while vaccination may reduce the severity of respiratory infections, the number of COVID-19 vaccine doses does not significantly affect the duration of other infections like influenza. Our study suggests that while COVID-19 vaccination may offer some protection against severe outcomes, it does not notably alter the course of influenza once contracted.

The study will serve as a venue for the exploration of the concepts through the input of the tertiary students the interaction of COVID-19 vaccine and seasonal flu. It is anticipated that their observations and subjective experiences could not tell the whole truth about public health, thus compelling health workers in conducting treatment. The findings are mainly dependent on self-reported information gathered through questionnaires and not by rigorous then too laboratory methods and clinical markers, causing the resultant evidence on vaccine effectiveness or cross-protection against influenza to become somewhat doubtful. The absence of corroborative diagnostic procedures (like PCR or clinical markers) would limit the study to just observed associations. Rather, they will become casual associations. The cross-sectional design further lacks the capacity for causal determination, leaving it potentially open to the influence of bias and other confounding variables that cannot be controlled for, such as changes in behavior post-vaccination versus pre-existing immunity. Specifically, valuable insights into the lower odds of flu among vaccinated individuals and much higher odds among boosters can be assumed. However, a recall and reporting bias creeping into their very methodology warrants a more stringent way of doing things. This calls for greater longitudinal or experimental research for diverse population testing and objective clinical information in further validation and enhancement of application to effective public health strategies.

Limitations of the Study

This study has several limitations. Its cross-sectional design prevents establishing causal relationships between COVID-19 vaccination and influenza incidence. The self-reported data introduce recall bias and potential misclassification errors, as influenza cases were not clinically confirmed via PCR testing. The study’s voluntary participation and focus on a single university (KSAU-HS) limit generalizability to broader populations. Additionally, unmeasured confounders, such as immune status and previous influenza vaccination, may influence results. While logistic regression adjusted for key variables, behavioral changes post-vaccination could not be fully accounted for. Future research should employ longitudinal designs with clinical validation to provide stronger evidence on the interaction between COVID-19 vaccination and seasonal influenza.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study underscores the need for continued research into the complex interactions between different vaccines and respiratory viruses. (Lv et al., 2020) confirmed that the immune system’s response to one vaccine can have unpredictable effects on other pathogens, highlighting the importance of further investigation into the long-term impacts of COVID-19 vaccination on influenza and other respiratory infections.

This research contributes to the growing body of knowledge on the relationship between COVID-19 vaccination and seasonal influenza incidence. While COVID-19 vaccines may reduce the risk of influenza in some individuals, particularly when combined with preventive measures like mask-wearing, further studies are necessary to fully understand these interactions. Maintaining preventive behaviors and promoting influenza vaccination, even after receiving the COVID-19 vaccine, remain crucial in reducing the burden of respiratory infections in university settings and beyond.

References

-

Abushouk, A., Ahmed, M. E., Althagafi, Z., Almehmadi, A., Alasmari, S., Alenezi, F., Fallata, M., & Alshamrani, R. (2023). Knowledge, attitude, and practice toward seasonal influenza vaccine during the COVID-19 pandemic among students at King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences-Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 12(1), 17. [CrossRef]

-

Alwazzeh, M. J., Telmesani, L. M., AlEnazi, A. S., Buohliqah, L. A., Halawani, R. T., Jatoi, N.-A., Subbarayalu, A. V., & Almuhanna, F. A. (2021). Seasonal influenza vaccination coverage and its association with COVID-19 in Saudi Arabia. Informatics in Medicine Unlocked, 27, 100809. [CrossRef]

-

Amanatidou, E., Gkiouliava, A., Pella, E., Serafidi, M., Tsilingiris, D., Vallianou, N. G., Karampela, Ι., & Dalamaga, M. (2022). Breakthrough infections after COVID-19 vaccination: Insights, perspectives, and challenges. Metabolism Open, 14, 100180. [CrossRef]

-

Basile, L., Torner, N., Martínez, A., Mosquera, M., Marcos, M., & Jane, M. (2019). Seasonal influenza surveillance: Observational study on the 2017–2018 season with predominant B influenza virus circulation. Vacunas, 20(2), 53-59.

-

Bresee, J., Fitzner, J., Campbell, H., Cohen, C., Cozza, V., Jara, J., Krishnan, A., & Lee, V. (2018). Progress and remaining gaps in estimating the global disease burden of influenza. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 24(7), 1173. [CrossRef]

-

Chenchula, S., Karunakaran, P., Sharma, S., & Chavan, M. (2022). Current evidence on efficacy of COVID-19 booster dose vaccination against the Omicron variant: A systematic review. Journal of Medical Virology, 94(7), 2969-2976. [CrossRef]

-

Dietz, E., Pritchard, E., Pouwels, K., Ehsaan, M., Blake, J., Gaughan, C., ... & Walker, A. S. (2024). SARS-CoV-2, influenza A/B, and respiratory syncytial virus positivity and association with influenza-like illness and self-reported symptoms, over the 2022/23 winter season in the UK: A longitudinal surveillance cohort. BMC Medicine, 22(1), 143. [CrossRef]

-

Greaney, A. J., Loes, A. N., Crawford, K. H. D., Starr, T. N., Malone, K. D., Chu, H. Y., & Bloom, J. D. (2021). Comprehensive mapping of mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain that affect recognition by polyclonal human plasma antibodies. Cell Host & Microbe, 29(3), 463-476.e466. [CrossRef]

-

Hamadah, R. E., Hussain, A. N., Alsoghayer, N. A., Alkhenizan, Z. A., Alajlan, H. A., & Alkhenizan, A. H. (2021). Attitude of parents towards seasonal influenza vaccination for children in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 10(2), 904-909. [CrossRef]

-

Hedberg, P., Valik, J. K., van der Werff, S., Tanushi, H., Mendez, A. R., Granath, F., ... & Naucler, P. (2022). Clinical phenotypes and outcomes of SARS-CoV-2, influenza, RSV, and seven other respiratory viruses: A retrospective study using complete hospital data. Thorax, 77(2), 1-10. [CrossRef]

-

Janssen, C., Mosnier, A., Gavazzi, G., Combadière, B., Crepey, P., Gaillat, J., Launay, O., & Botelho-Nevers, E. (2022). Coadministration of seasonal influenza and COVID-19 vaccines: A systematic review of clinical studies. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 18(6), 2131166. [CrossRef]

-

Kayano, T., Ko, Y., Otani, K., Kobayashi, T., Suzuki, M., & Nishiura, H. (2023). Evaluating the COVID-19 vaccination program in Japan, 2021 using the counterfactual reproduction number. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 17762. [CrossRef]

-

Kissler, S. M., Tedijanto, C., Goldstein, E., Grad, Y. H., & Lipsitch, M. (2020). Projecting the transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 through the post-pandemic period. Science, 368(6493), 860-868.

-

Li, Q., Tang, B., Bragazzi, N. L., Xiao, Y., & Wu, J. (2020). Modeling the impact of mass influenza vaccination and public health interventions on COVID-19 epidemics with limited detection capability. Mathematical Biosciences, 325, 108378. [CrossRef]

-

Lv, H., Wu, N. C., Tsang, O. T., Yuan, M., Perera, R., Leung, W. S., ... & Mok, C. K. P. (2020). Cross-reactive antibody response between SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV infections. bioRxiv. [CrossRef]

-

Macias, A. E., McElhaney, J. E., Chaves, S. S., Nealon, J., Nunes, M. C., Samson, S. I., Seet, B. T., Weinke, T., & Yu, H. (2021). The disease burden of influenza beyond respiratory illness. Vaccine, 39, A6-A14. [CrossRef]

-

MacIntyre, C. R., & Chughtai, A. A. (2015). Facemasks for the prevention of infection in healthcare and community settings. BMJ, 350. [CrossRef]

-

Rabie, T., & Curtis, V. (2006). Handwashing and risk of respiratory infections: A quantitative systematic review. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 11(3), 258-267. [CrossRef]

-

Riccò, M., Ferraro, P., Peruzzi, S., Zaniboni, A., & Ranzieri, S. (2022). Respiratory syncytial virus: Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of general practitioners from North-Eastern Italy (2021). Pediatric Reports, 14(2), 147-165. [CrossRef]

-

Tregoning, J. S., Brown, E. S., Cheeseman, H. M., Flight, K. E., Higham, S. L., Lemm, N., Pierce, B. F., Stirling, D. C., Wang, Z., & Pollock, K. M. (2020). Vaccines for COVID-19. Clinical & Experimental Immunology, 202(2), 162-192.

-

van Laak, A., Verhees, R., Knottnerus, J. A., Hooiveld, M., Winkens, B., & Dinant, G.-J. (2022). Impact of influenza vaccination on GP-diagnosed COVID-19 and all-cause mortality: A Dutch cohort study. BMJ Open, 12(9), e061727. [CrossRef]

-

Wals, P. D., & Divangahi, M. (2020). Could seasonal influenza vaccination influence COVID-19 risk? medRxiv, 2020.2009, 2002.20186734.

-

Wang, Z., Schmidt, F., Weisblum, Y., Muecksch, F., Barnes, C. O., Finkin, S., ... & Nussenzweig, M. C. (2021). mRNA vaccine-elicited antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 and circulating variants. Nature, 592(7855), 616-622. [CrossRef]

-

Zhou, F., Yu, T., Du, R., Fan, G., Liu, Y., Liu, Z., ... & Cao, B. (2020). Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: A retrospective cohort study. The Lancet, 395(10229), 1054-1062. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).