Submitted:

17 March 2025

Posted:

17 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Areas and Sample Collection

2.2. Microbiological Testing

2.3. DNA Extraction

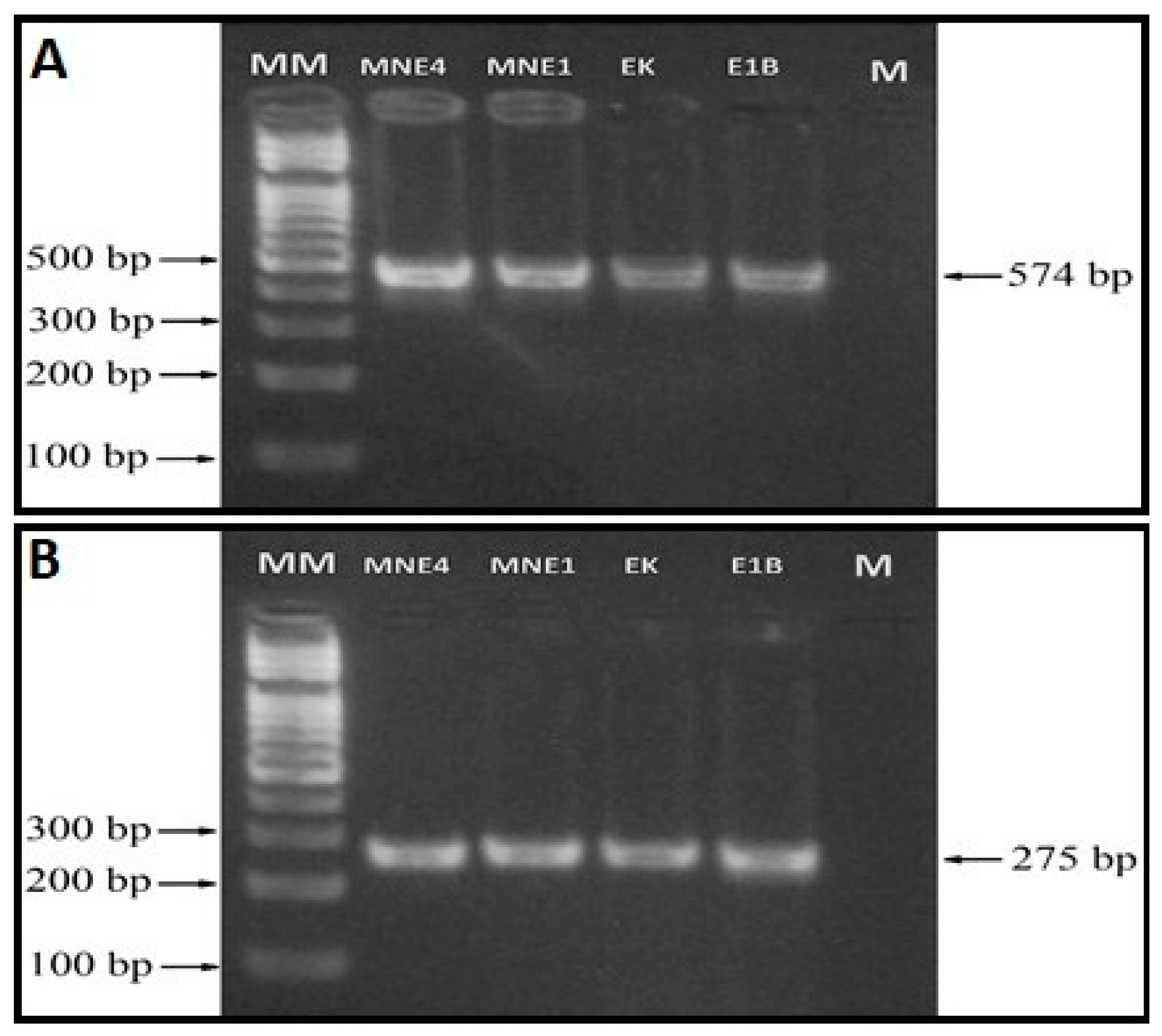

2.4. PCR for the rpsG and vmm Genes Amplification

2.5. Sequence and Bioinformatics Analysis

3. Results

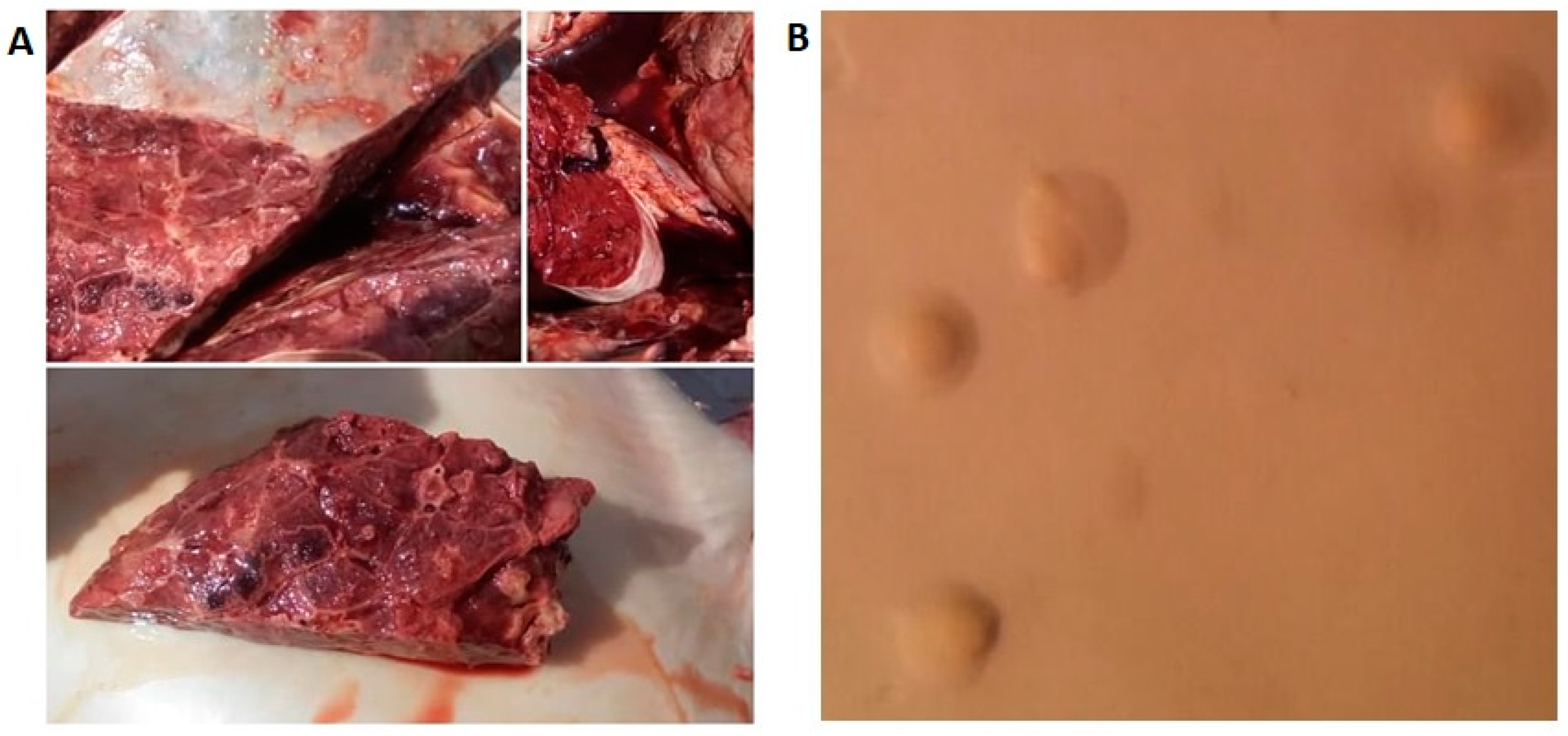

3.1. Microbiological Examinations

3.2. Molecular Identification

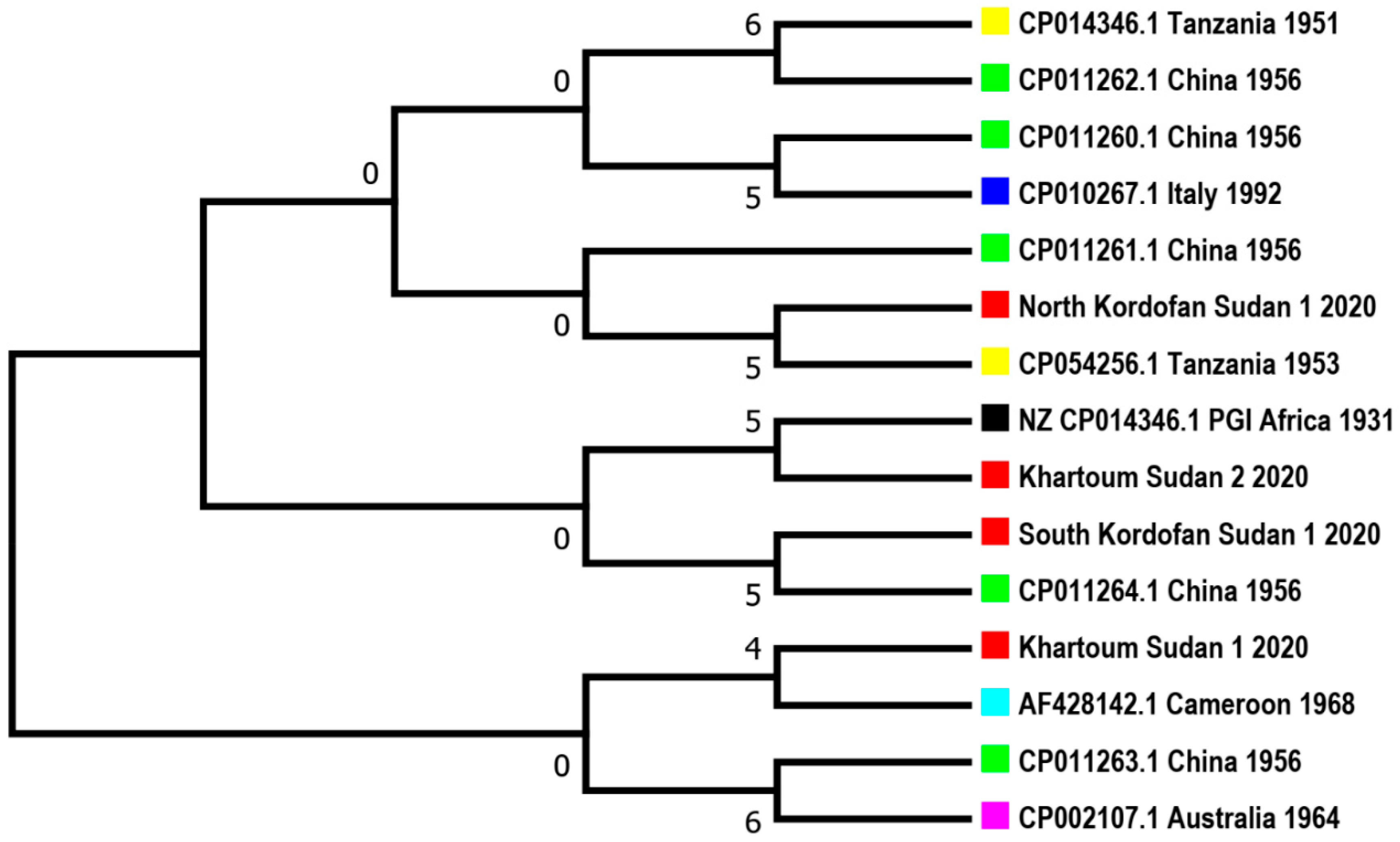

3.3. Sequences Blasting and Phylogenetic Tree

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Westberg J, Persson A, Holmberg A, Goesmann A, Lundeberg J, Johansson K-E, et al. The genome sequence of Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. mycoides SC type strain PG1T, the causative agent of contagious bovine pleuropneumonia (CBPP). Genome Res. 2004;14:221–7. [CrossRef]

- Costas M, Leach R, Mitchelmore D. Numerical analysis of PAGE protein patterns and the taxonomic relationships within the ‘Mycoplasma mycoides cluster.’ Microbiology. 1987;133:3319–29. [CrossRef]

- Stear, MJ. OIE Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals (Mammals, Birds and Bees) 5th Edn. Volumes 1 & 2. World Organization for Animal Health 2004. ISBN 92 9044 622 6.€ 140. Parasitology. 2005;130:727–727. [CrossRef]

- Olorunshola ID, Peters AR, Scacchia M, Nicholas RAJ. Contagious bovine pleuropneumonia - never out of Africa? CABI Rev. 2017;:1–7. [CrossRef]

- Thiaucourt F, Nwankpa N, Amanfu W. Contagious Bovine Pleuropneumonia Veterinary Vaccines: Principles and Applications. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Njeumi F, Taylor W, Diallo A, Miyagishima K, Pastoret P-P, Vallat B, et al. The long journey: a brief review of the eradication of rinderpest. Rev Sci Tech Int Off Epizoot. 2012;31:729–46. [CrossRef]

- Contagious bovine pleuropneumonia - WOAH (formerly OIE). WOAH - World Organisation for Animal Health. https://www.woah.org/en/disease/contagious-bovine-pleuropneumonia/. Accessed 30 Aug 2024.

- Regalla J, Caporale V, Giovannini A, Santini F, Martel JL, Gonçalves AP. Manifestation and epidemiology of contagious bovine pleuropneumonia in Europe. Rev Sci Tech Int Off Epizoot. 1996;15:1309–29. [CrossRef]

- Di Teodoro G, Marruchella G, Di Provvido A, D’Angelo AR, Orsini G, Di Giuseppe P, et al. Contagious bovine pleuropneumonia: a comprehensive overview. Vet Pathol. 2020;57:476–89. [CrossRef]

- Williams, H. Annual Report of the Sudan Veterinary Service, 1939. Annu Rep Sudan Vet Serv 1939. 1940.

- Amira S, Farh S. Contagious Bovine Pleuropneumonia Isolation and Seroprevalence in Khartoum State. Sudan Thesis Univ Khartoum. 2009.

- Thiaucourt F, Nwankpa ND, Amanfu W. Contagious bovine pleuropneumonia. Vet Vaccines Princ Appl. 2021;:317–26. [CrossRef]

- Dedieu L, Mady V, Lefèvre P-C. Development of a selective polymerase chain reaction assay for the detection of Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. mycoides SC (contagious bovine pleuropneumonia agent). Vet Microbiol. 1994;42:327–39. [CrossRef]

- Bashiruddin, JB. PCR and RFLP methods for the specific detection and identification of Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. mycoides SC. Mycoplasma Protoc. 1998;:167–78. [CrossRef]

- Monnerat M-P, Thiaucourt F, Poveda JB, Nicolet J, Frey J. Genetic and serological analysis of lipoprotein LppA in Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. mycoides LC and Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. capri. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1999;6:224–30. [CrossRef]

- Caswell, J. Failure of respiratory defenses in the pathogenesis of bacterial pneumonia of cattle. Vet Pathol. 2014;51:393–409. [CrossRef]

- Lesnoff M, Laval G, Bonnet P, Workalemahu A. A mathematical model of contagious bovine pleuropneumonia (CBPP) within-herd outbreaks for economic evaluation of local control strategies: an illustration from a mixed crop-livestock system in Ethiopian highlands. Anim Res. 2004;53:429–38. [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Animal Health and Welfare (EFSA AHAW Panel), Nielsen SS, Alvarez J, Bicout DJ, Calistri P, Canali E, et al. Assessment of the control measures of the Category A diseases of the Animal Health Law: prohibitions in restricted zones and risk-mitigating treatments for products of animal origin and other materials. EFSA J. 2022;20:e07443. [CrossRef]

- Bölske G, Msami H, Gunnarsson A, Kapaga A, Loomu P. Contagious bovine pleuropneumonia in northern Tanzania, culture confirmation and serological studies. Trop Anim Health Prod. 1995;27:193–201. [CrossRef]

- Hussien M, Abdelhabib E, Hamid A, Musa A, Fadolelgaleel H, Alfaki S, et al. Seroepidemiological survey of contagious bovine pleuropneumonia among cattle in El Jazeera State (Central Sudan). Ir Vet J. 2024;77:9. [CrossRef]

- Molla W, Jemberu WT, Mekonnen SA, Tuli G, Almaw G. Seroprevalence and Risk Factors of Contagious Bovine Pleuropneumonia in Selected Districts of North Gondar Zone, Ethiopia. Front Vet Sci. 2021;8:626253. [CrossRef]

- Mamo Y, Bitew M, Teklemariam T, Soma M, Gebre D, Abera T, et al. Contagious bovine Pleuropneumonia: seroprevalence and risk factors in Gimbo district, southwest Ethiopia. Vet Med Int. 2018;2018. [CrossRef]

- Muuka G, Songolo N, Kabilika S, Hang’ombe BM, Nalubamba KS, Muma JB. Challenges of controlling contagious bovine pleuropneumonia in sub-Saharan Africa. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2012;45:9–15. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, RT. Directors of Veterinary Services in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan: Claude Percy Fisher (Director 1940-1944), 1918-1944. Director. 1944;1940:1918–44. [CrossRef]

- Zessin K-H, Baumann M, Schwabe CW, Thorburn M. Analyses of baseline surveillance data on contagious bovine pleuropneumonia in the southern Sudan. Prev Vet Med. 1985;3:371–89. [CrossRef]

- Gardner I, Colling A, Caraguel C, Crowther J, Jones G, Firestone S, et al. Introduction-Validation of tests for OIE-listed diseases as fit-for-purpose in a world of evolving diagnostic technologies. Rev Sci Tech Int Off Epizoot. 2021;40:19–28. [CrossRef]

- Edwards, S. OIE standards for vaccines and future trends. Rev Sci Tech Int Off Epizoot. 2007;26:373–8.

- Gourlay, R. Significance of mycoplasma infections in cattle. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1973;163:905–9. [CrossRef]

- Tully, JG. Tests for digitonin sensitivity and sterol requirement. In: Methods in mycoplasmology. Elsevier; 1983. p. 355–62.

- Ernø H, Stipkovits L. Bovine Mycoplasmas: Cultural and Biochemical Studies: I. Acta Vet Scand. 1973;14:436. [CrossRef]

- Senterfit, LB. Tetrazolium reduction. Methods Mycoplasmol V1 Mycoplasma Charact. 2012;1:377.

- Errington, J. L-form bacteria, cell walls and the origins of life. Open Biol. 2013;3:120143. [CrossRef]

- 36. Ciulla TA, Sklar RM, Hauser SL. A simple method for DNA purification from peripheral blood. Anal Biochem. 1988;174:485–8. [CrossRef]

- Tamura K, Nei M. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial DNA in humans and chimpanzees. Mol Biol Evol. 1993;10:512–26. [CrossRef]

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:1870–4. [CrossRef]

| Isolate location | No. lungs screened | Clinically diagnosed as CBPP |

|---|---|---|

| Khartoum | 12519 (39.1%) | 28 (15.7%) |

| North Kordofan | 10316 (32.2%) | 100 (56.2%) |

| South Kordofan | 9204 (28.7%) | 50 (28.1%) |

| Total | 32039 (100%) | 178 (0.6%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).