1. Introduction

1.1. History of Rocket Propulsion

Rockets and their fundamentals have been around humankind history for a while, with their bigger developments being associated with warfare. Starting as bamboo tubes filled with gunpowder used in religious celebrities, primitive rockets are invented in the 1st century China. “Arrows of flying fire”, resembling solid propellant rockets, are the first warfare application of rocket propulsion, used in 1232 by the Chinese army to repel the Mongol invaders.

It is during the 20th century that rocketry is heavily developed into almost nowadays technology, being encourage by the needs of World War Two and the Cold War.

Robert H. Goddard, an american engineer, designs and builds the first liquid propellant rocket. 34 rockets where launch between 1926 and 1941, getting to altitudes of up to 2.6 km and speeds as high as 885 km/h. Later, in 1945, the single and multi-stage rocket engines for both rocket and jet-assisted takeoff are developed by Goddard.

During the same time, german engineer Wernher von Braun develops the V-2, a liquid-propellant rocket missile used by the Axis Forces in World War Two. In the after math of the war, von Braun is recruited by NASA becoming a prominent figure in the developing of the Saturn V launcher.

During the height of the Space Race, driven by the Cold War, the development of rocket technology reached its peak, resulting in several notable milestones[

1]:

1957 – The launch of the first Earth-orbiting artificial satellite, Sputnik I, by the USSR. The satellite Sputnik II carried a dog named Laika into orbit, later that year.

1959 – The lunar surface is firstly touched by a human-made object, the USSR’s Luna 2

1961 – Venus is first flew by the USSR’s Venera 1, being the first to reach another planet.

1962 – Yuri Gagarin is the first human in space onboard the USSR’s Vostok spacecraft.

1969 – The American Apollo 11, powered by Saturn V rockets, successfully landed the first humans on the moon, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin.

2013 – Voyager 1, launched in 1977 by the USA, becomes the first human-made object to leave the solar system.

Nowadays, several nations like Europeans countries (under ESA), India, Japan, China, Brazil, among many others, have their own space programs, for which rockets, and their development, are crucial. Even more recently, the space industry stopped being a centralized state research to become also a private business, as recent Space X, Blue Origin and Virgin Galactic launches prove.

2. De Laval Convergent-Divergent Nozzle

Thrust is generated in aerial vehicles by mass ejection, as per Newton’s third law, mathematically by the simplified Equation

1. Besides the first parcel of the Equation corresponding to mass ejection, a second force is generated by the pressure difference between the flow at the exit and the ambient pressure, translated in the second parcel [

1].

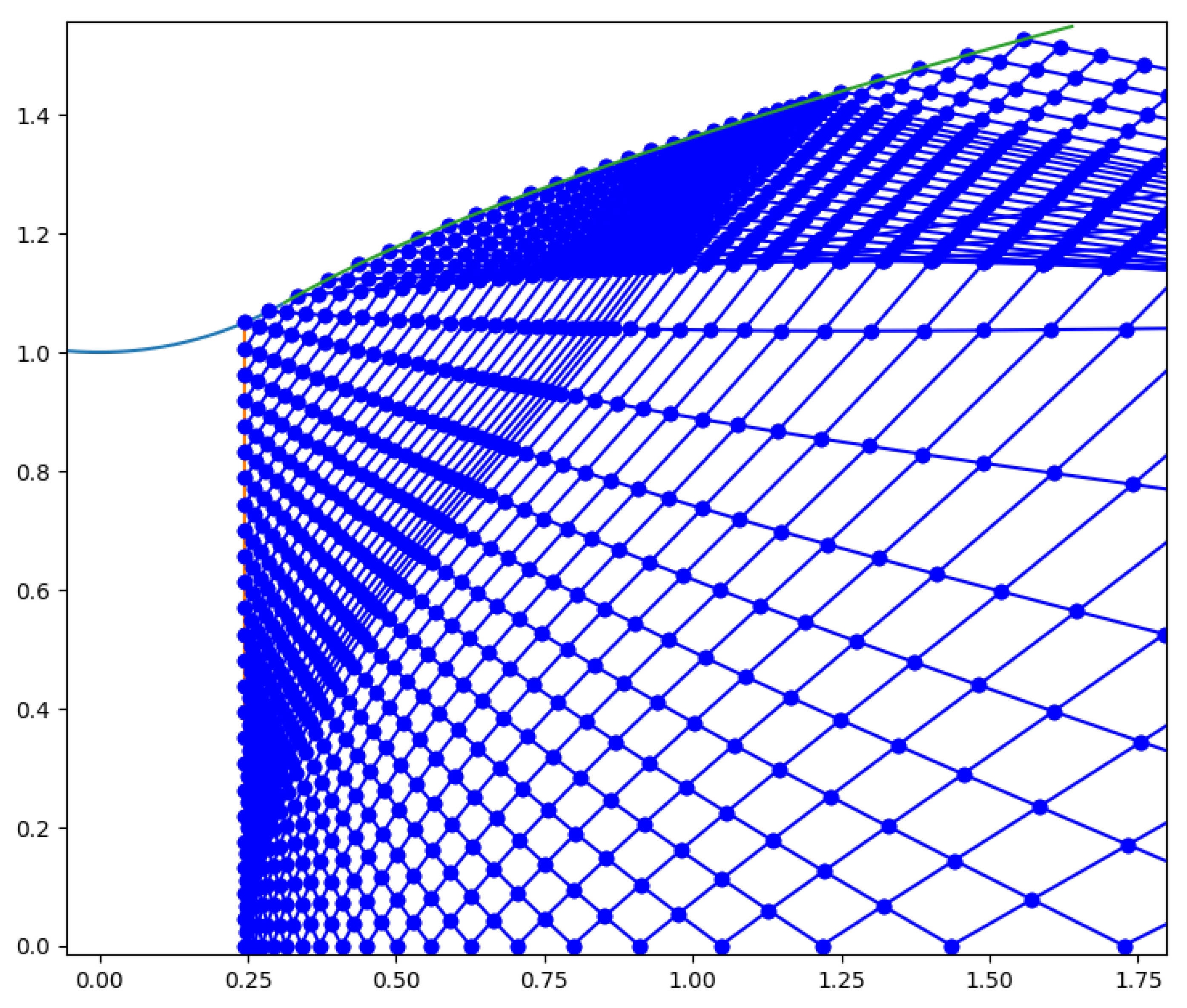

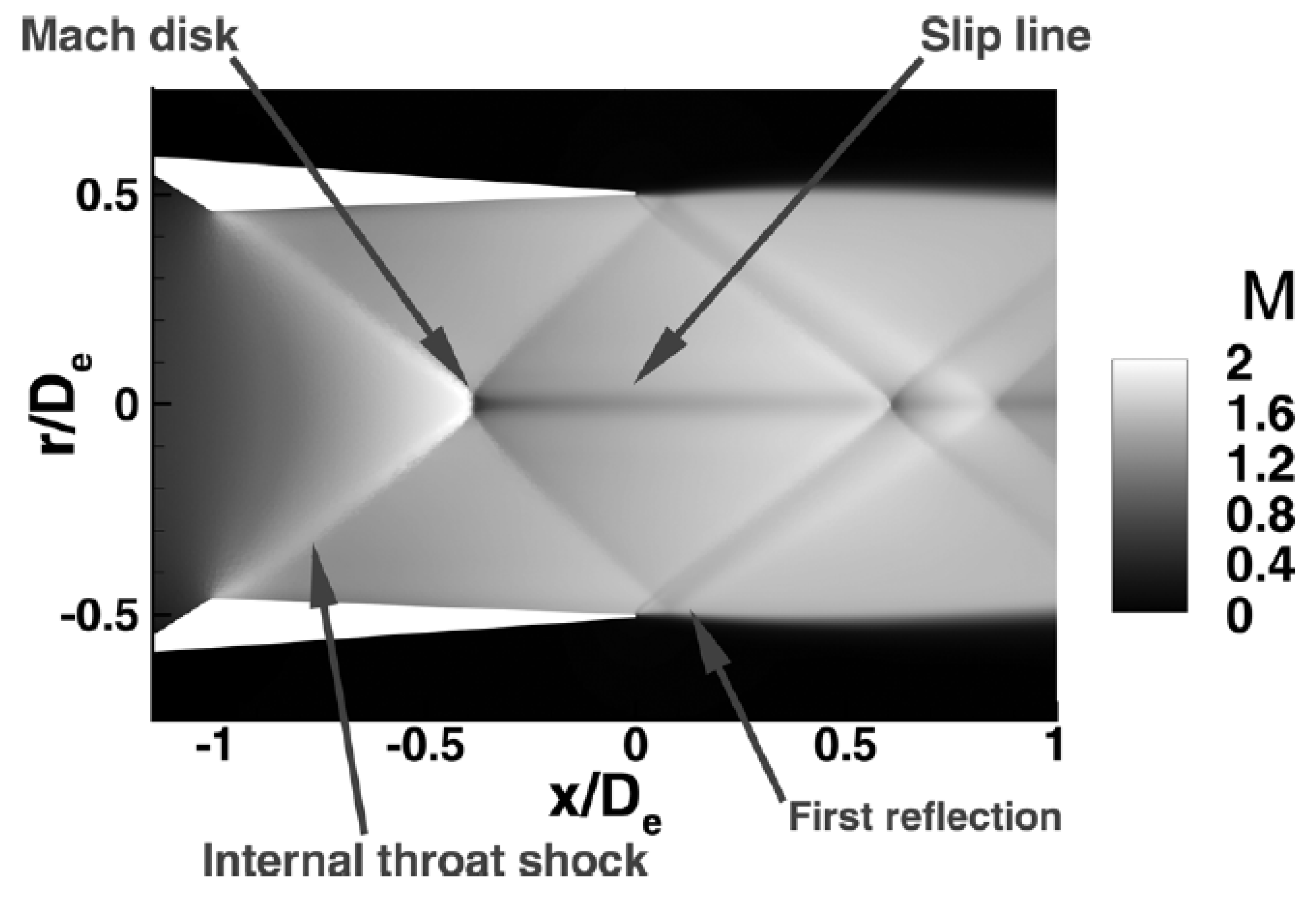

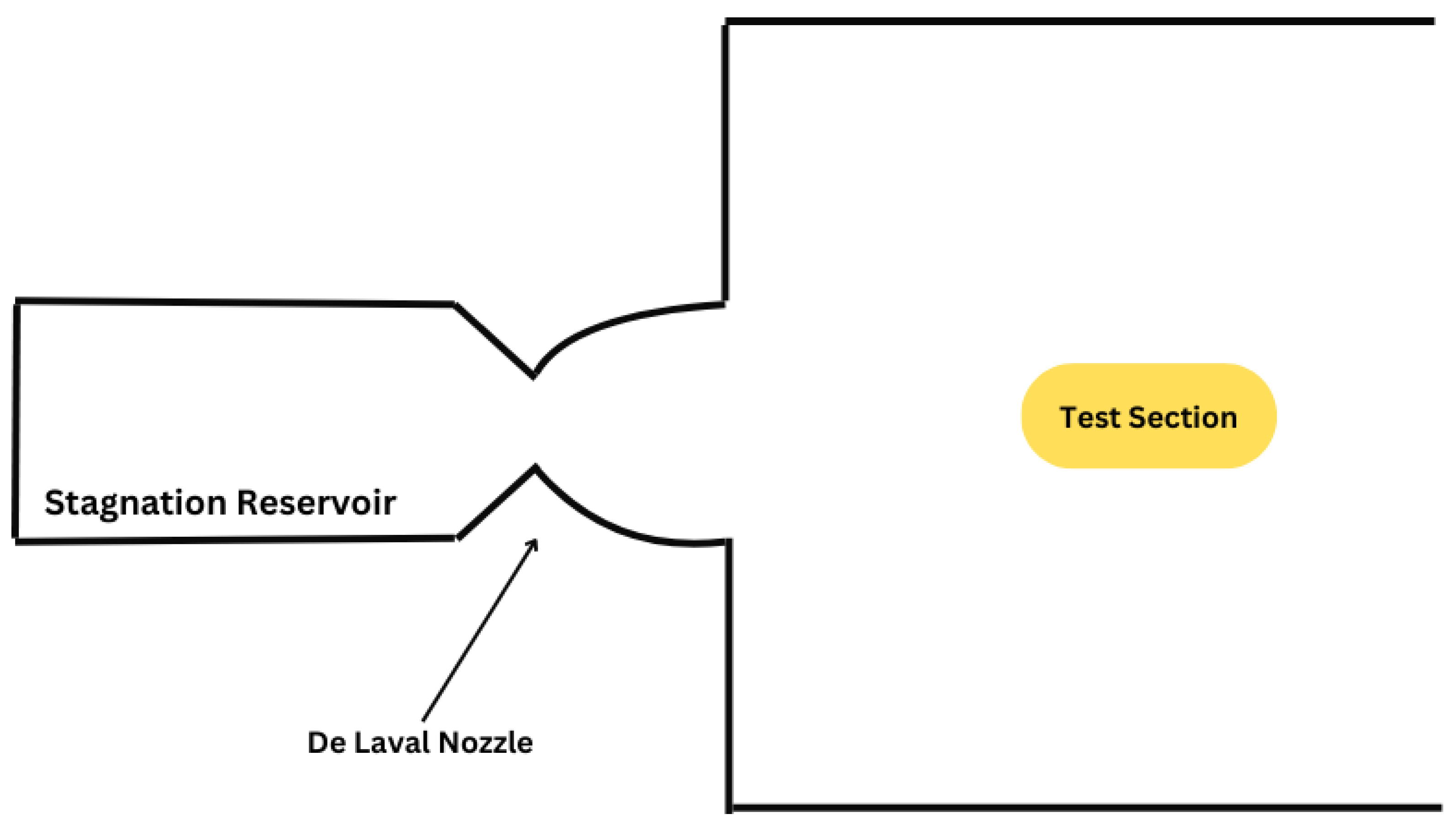

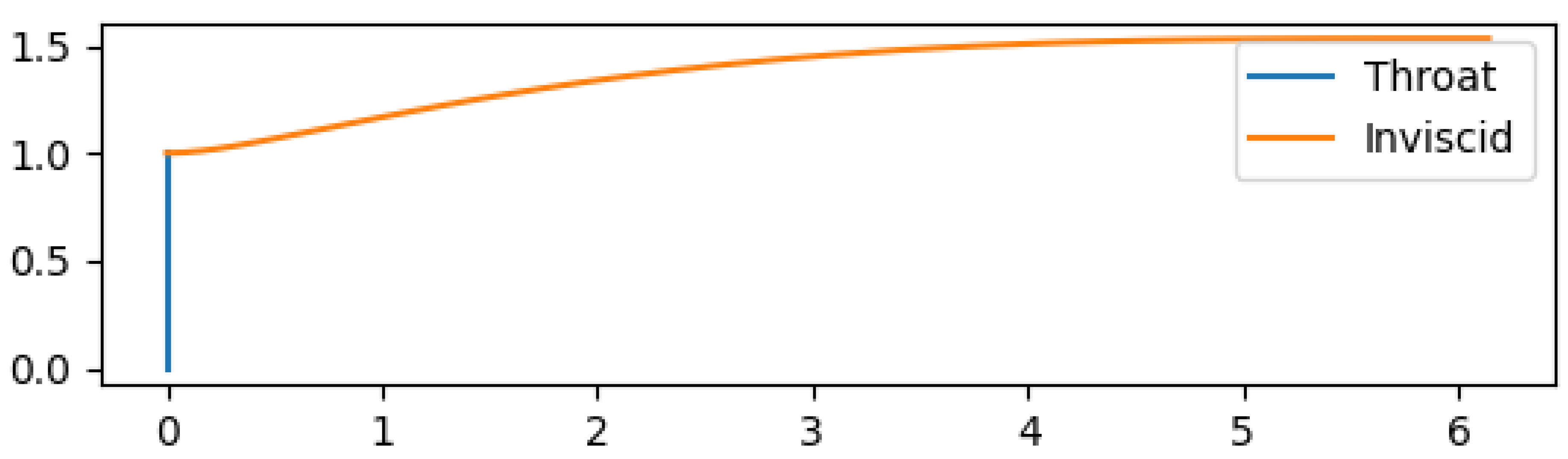

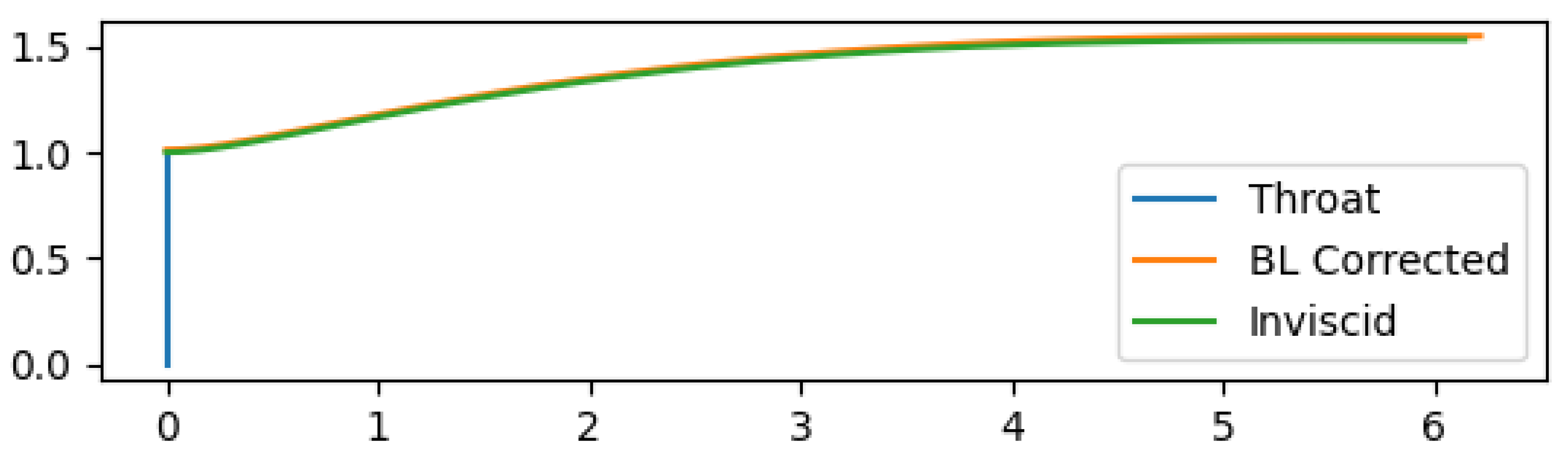

Nozzles where invented as means to change the properties of a flow such as velocity and pressure. The de Laval nozzle, containing a convergent followed by a divergent section does so in such a way that a supersonic flow can be obtain at the exit. The flow behavior off such nozzle is observed in

Figure 1.

A de Laval nozzle is composed of three sections: the convergent (subsonic), the throat (sonic) and the divergent (supersonic). In each regions, the flow behaves differently, with differentiated analysis methods to determinate its contribution for the production of thrust.

The convergent section accepts the hot and higly pressured exhaust gases from the combustion chamber, at almost static conditions, providing the first mean of acceleration until a sonic value. So, the convergent affects the mass flow and, at some degree, the efficiency of the combustion chamber.

At the throat, the flow reaches a sonic velocity, being choked, meaning it can not be accelerated further without area increases. Having a fixed area and Mach Number, it’s the throat, and flow’s properties dependent upon the conditions provided by the combustion chamber, that limits the mass flow through the nozzle, posing great impact on the thrust produced according to the first parcel of Equation

1.

The same parcel of thrust’s Equation

1, is also greatly impacted by the exit velocity. Since the flow is choked at the throat, is in the divergent section that accelerates it further to supersonic values. The comprehensible flow keeps on gaining kinetic energy as a trade off by losing internal energy (as seen in

Figure 1 by the decrease in temperature), with a pressure drop. The exit velocity is dependent on the ratio between exit and throat areas, outside conditions in relation to the chamber and the divergent section design that affects the flow’s orientation and can induce losses.

Three major concepts are necessary to evaluate a nozzle’s performance. The first concept, represented by Equation

2, is the specific impulse, which measures the thrust produced by the weight flow rate of propellant burned. It is important to understand the rocket’s nozzle efficiency.

The second concept, represented by Equation

3, is the total impulse, which measures the thrust produced over the entire duration of the engine’s operation.

Finally, the thrust coefficient, exhibited in Equation

4, represents the dimensionless value of thrust obtained by dividing it by the chamber pressure and the throat area. This is a fair indicator of nozzle efficiency since, in theory, the thrust value depends solely on the pressure ratio between the chamber and the ambient, and the area ratio between the exit plane and the throat [

3].

2.1. Ideal Nozzle

The ideal nozzle is a concept that provides the best theoretical performance for the given conditions, to which all nozzle designs are compared to. A parallel flow and exit pressure matching external pressure are some consequences from this simplification. Looking into more detail, the ideal nozzle involves the following considerations [

3]:

The exhaust gases are in chemical equilibrium, with a homogeneous composition and in a gaseous state.

The exhaust gases obey the perfect gases law.

The flow is adiabatic, meaning there are no appreciable heat transfers to the wall.

The flow is isentropic, without discontinuities in properties and/or shock waves.

The boundary layer effects are neglected, with no wall friction decelerating parts of the flow.

The flow rate is constant and steady, without gas pulsations, turbulence, and with the transient effects of starting-up and shutting down neglected since they are of short duration.

The exit flow is parallel and uni-dimensional.

The flow’s velocity, pressure, temperature, and density are uniform across any nozzle’s normal section.

Before the combustion process, propellants are store at ambient temperature, except for cryogenics which are at their boiling point.

Nonetheless, this are fair simplifications due to how fast the expansion occurs. For chemical rockets, tested efficiency parameters are usually just 1%-6% below those calculated with totally ideal assumptions [

3].

3. Real Nozzle

The level of precision required for rocket systems and to optimize an already very efficient system, demands more accurate algorithms that involve a better understanding of energy losses, heat transfer and other physical or chemical phenomena.

In real nozzles, not all the chemical energy contained in the propellant is available as thermal energy, and not all the thermal energy can be converted into kinetic energy. Therefore, the performance of a rocket nozzle is affected by several factors and non-idealities that can cause losses in thrust and specific impulse.

The first factor, already stated before as a concern, is the divergency losses resulting from a non-unidimensional flow profile at the exit plane due nozzle contours that don’t end in a null slope. Another factor is that small chamber areas relative to the throat, lead to pressure losses in the chamber and a reduction of the exhaust exit velocity and thrust produced.

Boundary layer effects can also be significant, particularly for smaller nozzles with low area ratios, making a portion of the flow, ranging from to , subsonic. Due to the no-slip condition, the flow next to the wall has zero-speed with high thermal energy that is dissipated to the wall and the nearby moving flow. The immediate flow is laminar and subsonic, turning further from the wall into transonic/supersonic zones where turbulence can occur, before it joins the totally supersonic free stream.

Combustion in the rocket propulsion is typically unsteady, resulting in flow oscillations and lower chamber pressure during transient operations. Chemical reactions in the flow can cause losses of up to , and incomplete mixing of the gas composition means that the gas constants are not uniform throughout the nozzle, contributing for some mathematical incongruities of the numerical models.

Small solid particles and liquid droplets also exist in the flow, which need to be accelerated, with little thermal energy contribution. If bigger than 0.015mm and equivalent to more than 6% of the flow’s mass, specific impulse losses can rise to -. Although less significant, in high area ratio nozzles, aggressive expansion can lead to the precipitation of some exhaust constituents.

It still must be mentioned that uncooled materials suffer erosion, a phenomena of upmost relevance for the throat since, if its area increases, some chamber pressure is lost, with an additional area ratio decrease. Up to of specific impulse can be lost.

And, at last, operating away from the design altitude reduces thrust and specific impulse for nozzles with fixed area ratio [

3].

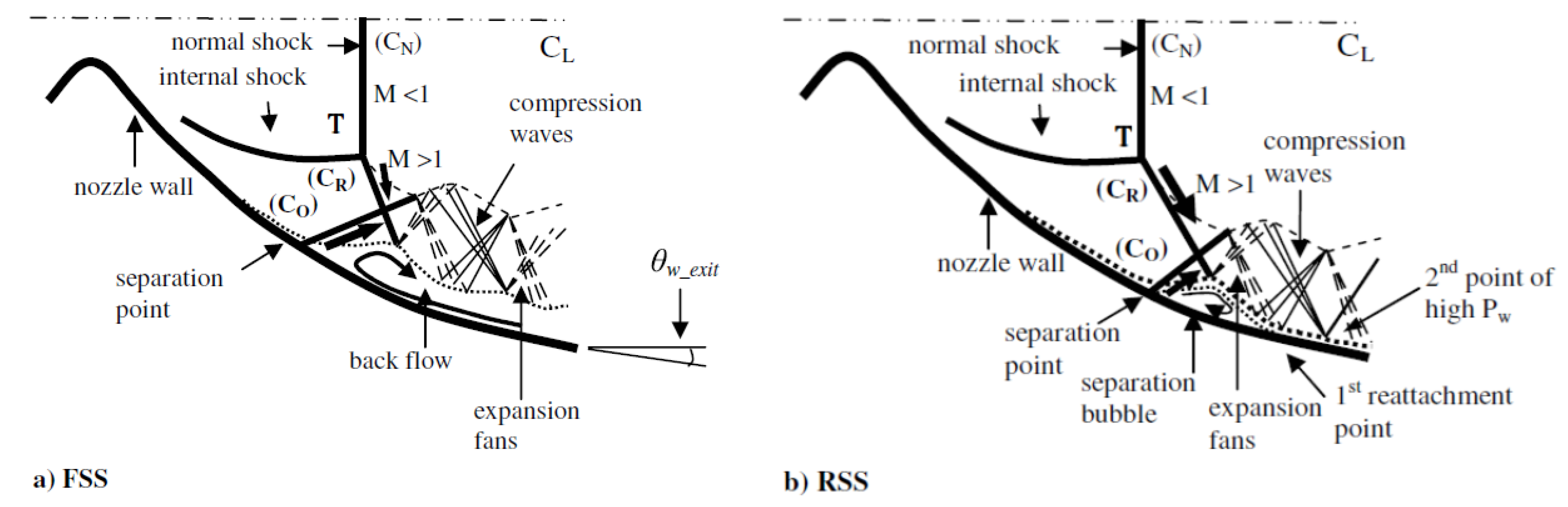

4. Nozzle Phenomena

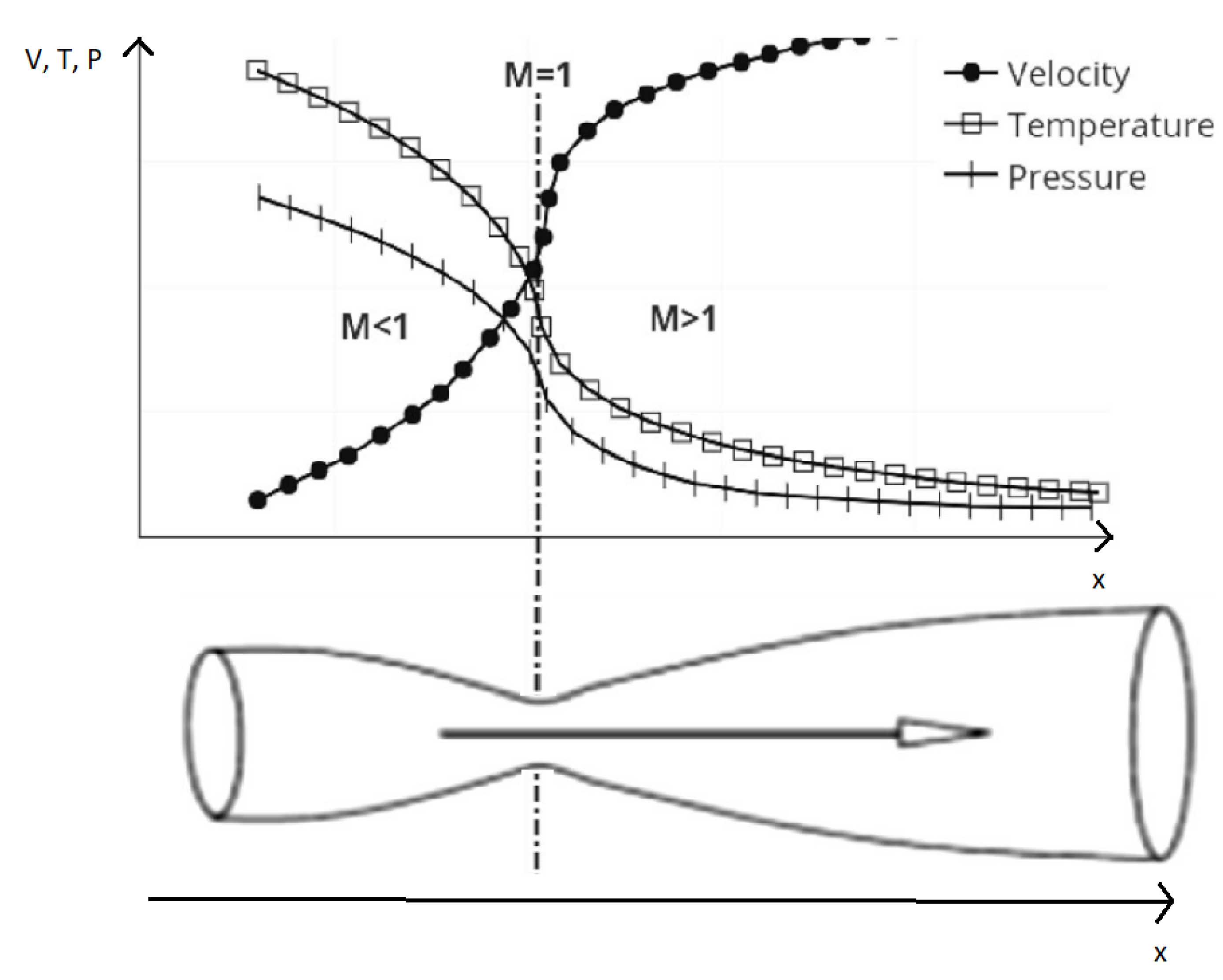

4.1. Operation Critical Points

Fixing the chamber pressure, flow begins in subsonic regime throughout the entire nozzle when the outside pressure starts to drop, expanding in the divergent and xompressing in the divergent. As the pressure ratio (

) increases, the flow accelerates and the mass flow rate rises until it reaches a sonic value at the throat, causing the flow to choke. Beyond the throat, the flow keeps compressing in the divergent section, and it returns to a subsonic regime. This point is called the first critical point and is represented in

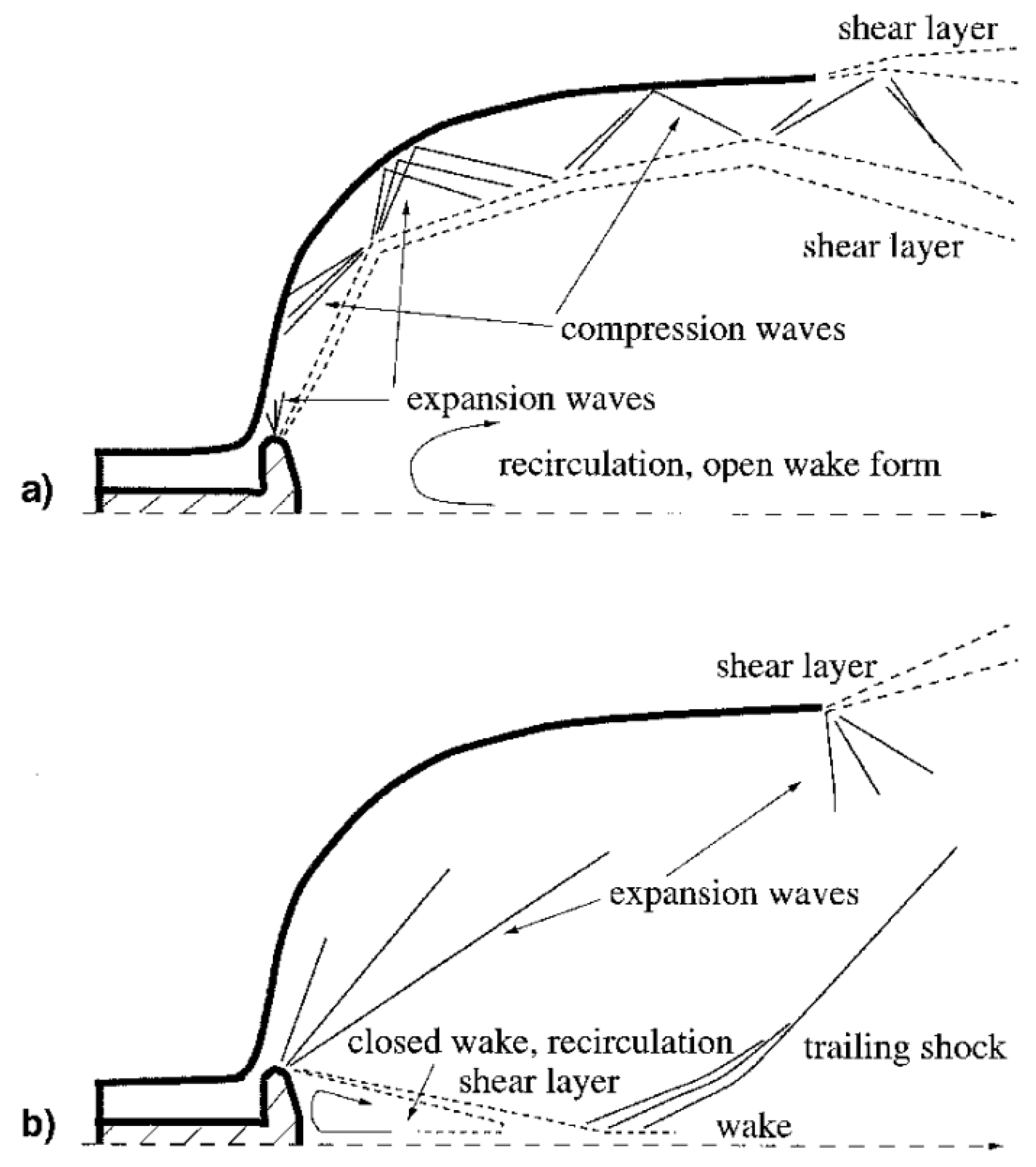

Figure 2 by curve a. Any infinitesimal decrease in the outside pressure beyond the first critical point will cause the flow in the divergent section to change from subsonic to supersonic.

Now that there is a supersonic flow in the divergent section, it no longer compresses but expands, but the great area variation promotes a more aggressive expansion than the one needed to equal the ambient pressure. Thus, a shock forms inside the divergent section, starting at the throat and moving to the exit plane as the outside pressure drops and a non-isentropic compression besides the shock is needed so, after the shock, the flow becomes subsonic and uses the remaining divergent section as a compressor. This is represented by line b in

Figure 2. When the outside pressure is low enough, the shock reaches the exit plane, as suggested by line c in the same figure, representing the second critical point.

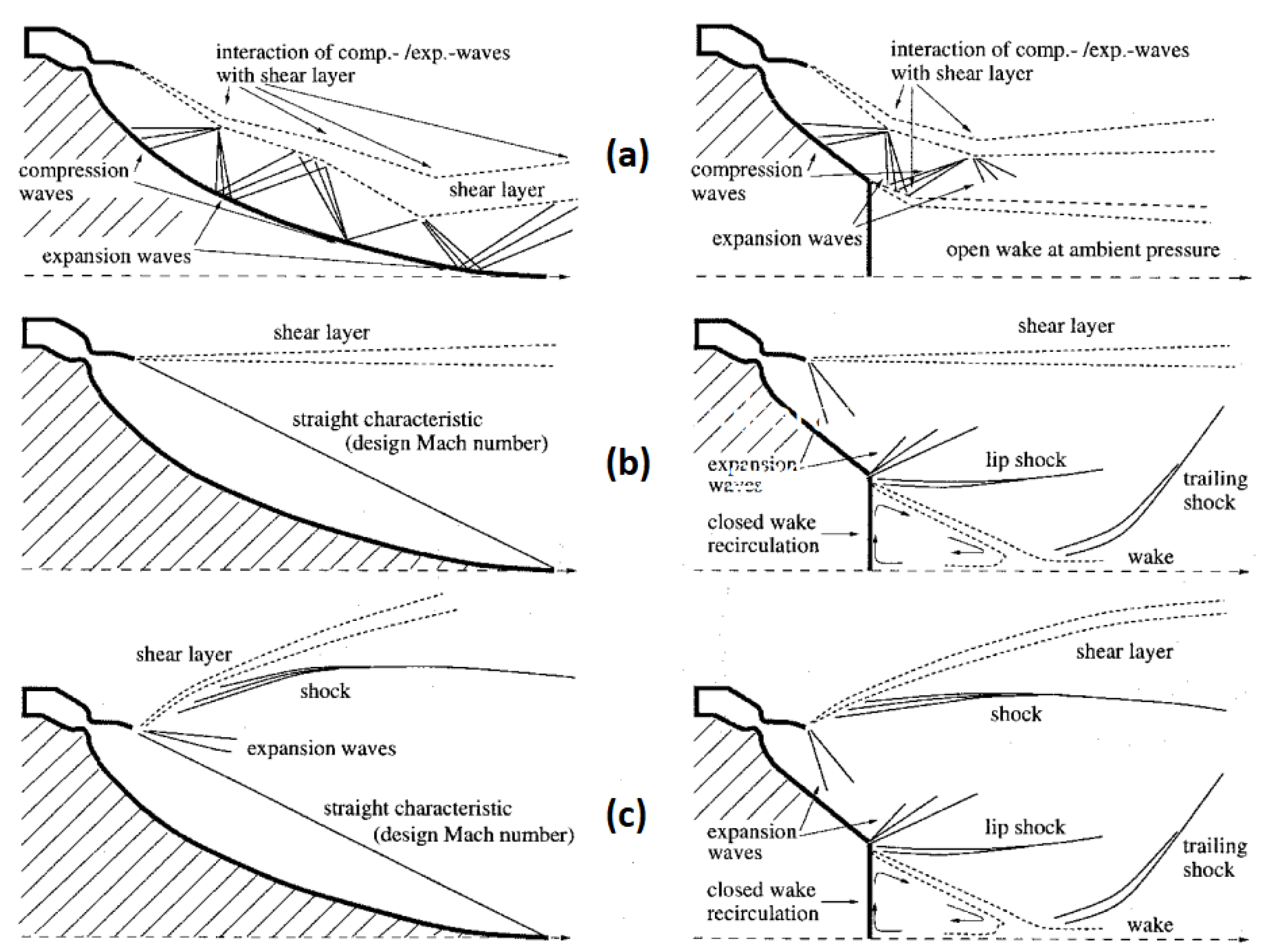

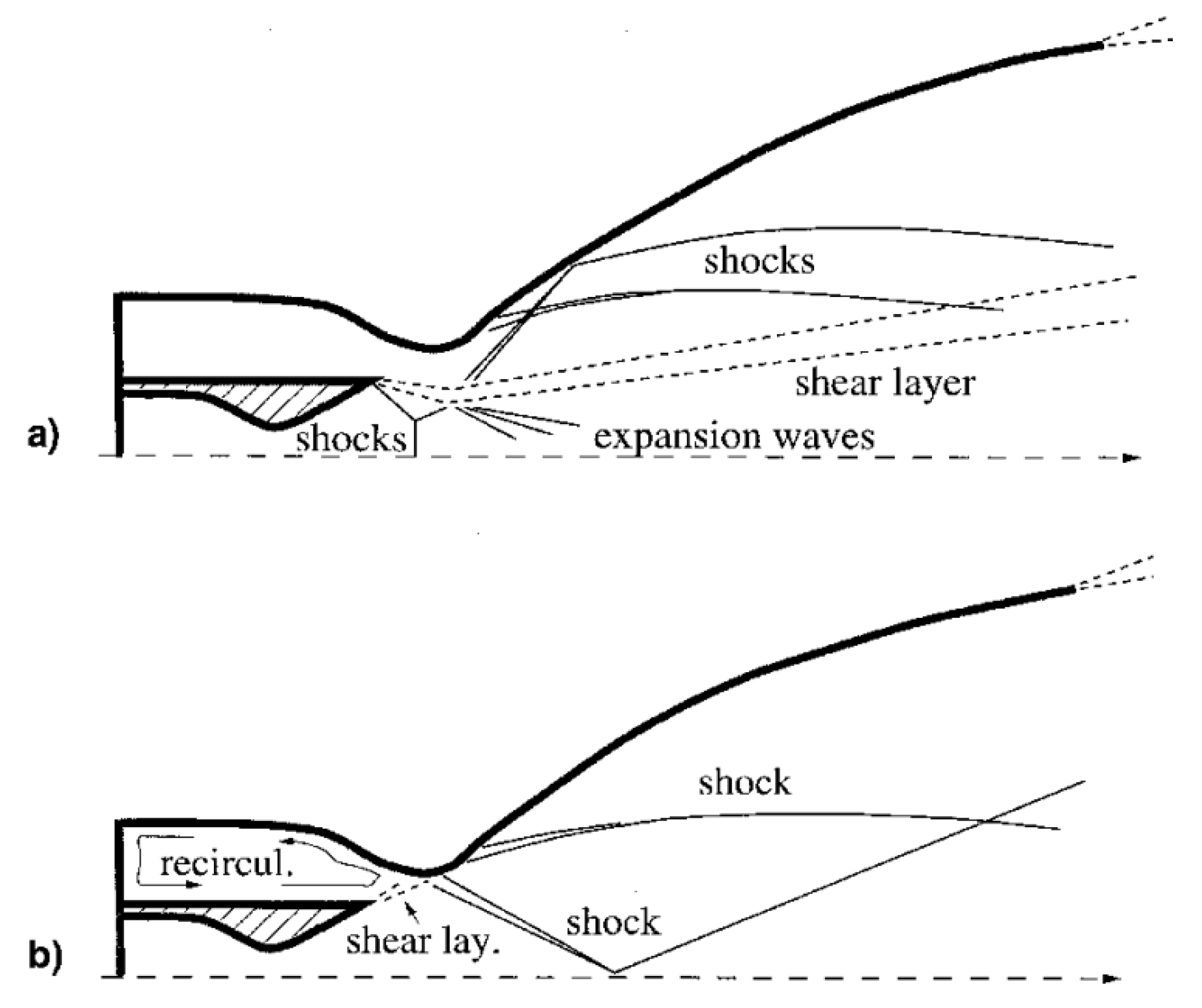

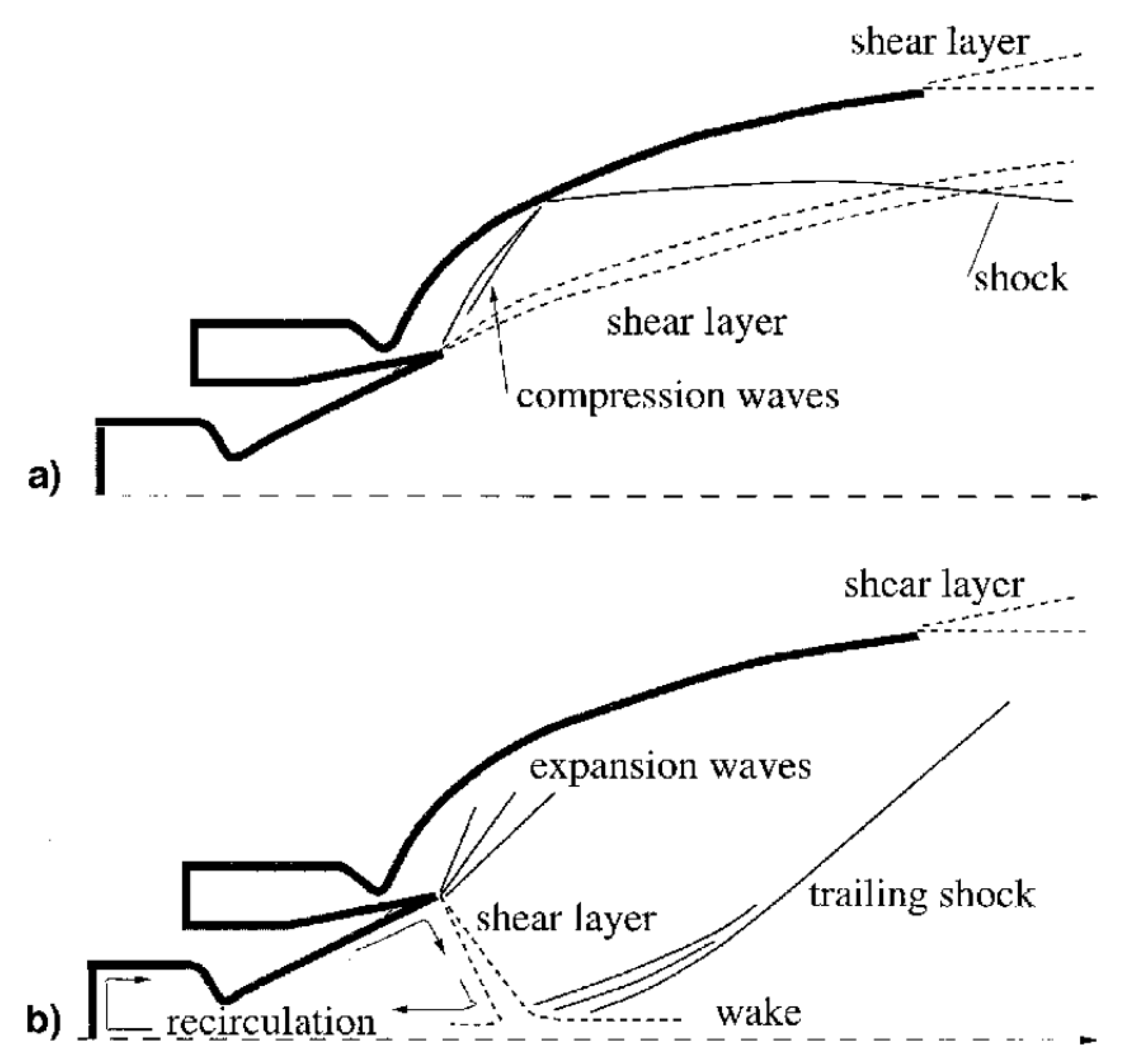

After the second critical point, the flow will not be able to expand much further even if the ambient pressure keeps dropping. However, it still reaches the exit plane at higher pressures than the ambient. Therefore, the normal shock at the exit begins to turn oblique, with its intensity/angle reducing as the outside pressure decreases. This phenomenon is known as an overexpanding nozzle.

The oblique shock will eventually reach a angle, representing no shock at all, and the nozzle reaches its third critical point. At this point, the flow is isentropic and is used as the nozzle’s design point.

Further decreases in outside pressure will cause the flow to have a pressure higher than the ambient pressure at the exit, which is known as underexpansion. In this case, expansion fans will be generated from the nozzle’s lips to allow the flow to be further expanded beyond the exit plane.

4.2. Overexpansion and Underexpansion Phenomena

The overexpansion occurs when the ambient pressure is higher than the one at the third critical point. A weak shock is needed at the exit so that the flow pressure increases until it matches the ambient pressure.

But the oblique shock will deviate the flow, so a second shock is needed to realign the flow. This will increase the pressure, making it higher than the ambient pressure, so now an expansion fan is needed to expand the flow and match the ambient pressure once again.

The expansion fan also deviates the flow, requiring another expansion fan to straighten the flow, returning it to a state where its pressure is again below the ambient pressure.

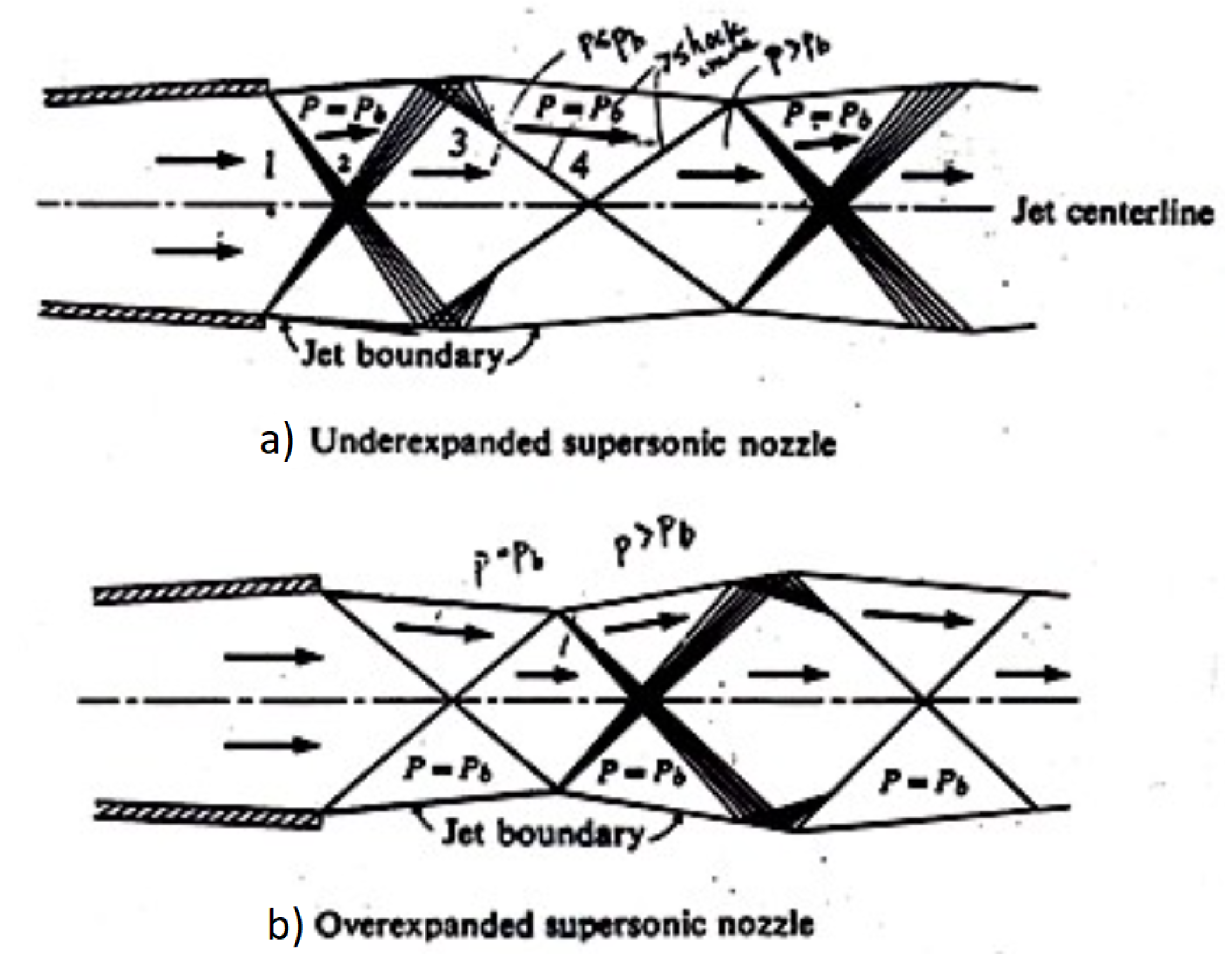

The process repeats itself, as shown in

Figure 3b), forming a structure known as the Mach Diamond. The underexpansion process, depicted in

Figure 3a), is similar, but starts with a pair of expansion fans at the exit .

5. Theory of Flow in Nozzles

6. Introduction to High Velocity Compressible Flow

When a flow subjected to great gradients and accelerates to high velocities from stagnation, density cannot be assumed to be constant raising the concept of compressible flow. Examining Equation

5, if the pressure experienced by a finite volume of fluid increases, compression occurs, resulting in a reduction in volume and an increase in density. The symbol

represents the compressibility of the gas, which has different values for isothermal and isentropic processes.

High-speed flows are often initiated and propelled by strong pressure gradients. Therefore, the impact of pressure on the gas density cannot be ignored. Equation

6 relates the three main properties for any two states in a gaseous flows assuming isentropy. [

6].

6.1. Speed of Sound and Mach Number

All particles within a fluid move in random directions with a certain velocity, attributing the fluid a specific internal energy. This random kinetic propagation speed is known as the speed of sound, and it is dependent on the fluid and its internal energy, as described by Equation

7 for thermally and calorically perfect gases. When a perturbation is applied to the fluid, it will excite nearby molecules, which will eventually collide with other molecules, transmitting the disturbance at a specified mean speed.

The Mach number is defined as the ratio between the velocity of the flow and the velocity of sound, as shown in Equation

8. It represents the relationship between the flow’s kinetic energy and the random molecular kinetic energy. Based on it, different flow regimes can be established, including:

Incompressible (M < 0.3) – Density variations are small, mostly because these flows are not associated with strong pressure gradients. Hence, this flow can be assumed to possess constant density.

Subsonic (0.3 < M < 0.8 at freestream) – Property variations are always continuous, and the flow exhibits straight and parallel streamlines that move, converge and shape around any obstacle. In every point, the flow has a Mach number less than 1, but compressibility effects cannot be ignored.

Transient (0.8 < M< 1.2) – As the flow approaches the speed of sound, it is not possible to guarantee that all the flow is subsonic since it may accelerate while contouring an object, creating supersonic "pockets." Shocks can appear, indicating discontinuous changes in properties.

Supersonic (M > 1) – The entire flow moves faster than the speed of sound. Streamlines do not bend around objects, except when encountering a shock or experiencing an expansion wave. After a shock, the flow must remain supersonic.

Hypersonic (M > 5) – At such high speeds, a shock wave causes explosive changes in properties. The temperature can increase so much that molecular dissociation effects must be considered. Nothing particularly special happens at M = 5, as the referred phenomenon increases with the Mach number, being just a convention.

The Mach number allows the calculation of the Mach Angle, as shown in Equation

9, which is half of the Mach Cone’s angle. This structure is formed by pressure waves and appears around bodies moving faster than the speed of sound. To be noted that the outside of the Mach Cone is called the silence zone, where the presence of a moving object cannot be heard.

6.2. Stagnation Properties

All motion is described in relation to a reference frame. In compressible flow, an isentropic deceleration can be implemented until the flow becomes static in relation to such reference frame. The new values of the fluid’s properties are called total or stagnation properties, identified with the suffix “0”. In a rocket’s nozzle, this reference state is the conditions felt at the combustion chamber, as velocity is so small compared to that at the nozzle, so it can be overlooked.

The static values of the properties are associated with the stagnation ones by the velocity at which the fluid is moving, as described by Equations

10,

11 and

12. As the Mach number of the flow increases by an isentropic process, these three static properties decrease.

6.3. Normal or Strong Shock

A shock represents a discontinuity in fluid properties that occurs in a very thin region, meaning there are significant temperature and pressure gradients, where viscosity and dissipative effects are strongly felt. As a result, the process is not isentropic, and the relations in Equation

6 are no longer valid. As no heat is added or removed from the flow, the process is adiabatic.

Equations

13,

14,

15, and

16 establish the properties of the flow across the normal shock through an adiabatic and irreversible process.

Nonetheless, these equations admit that the flow before the shock can be subsonic (M<1). Therefore, the second law of thermodynamics must be taken into account through Equation

17. For an unitary Mach number, an isentropic

infinitely weak normal shock is obtained, and for a subsonic Mach number, a negative variation of entropy is predicted, which is physically impossible.

Since shocks are adiabatic processes, the stagnation temperature remains the same. Nevertheless, the stagnation pressure drops, and it is related to the entropy gain as shown in Equation

18.

6.4. Oblique or Normal Shock

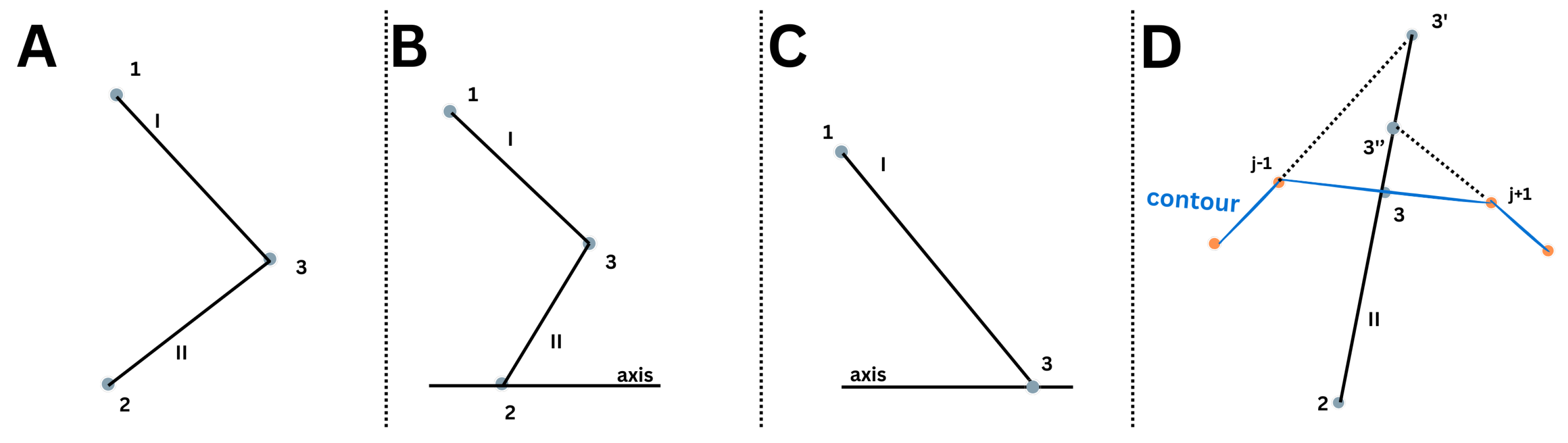

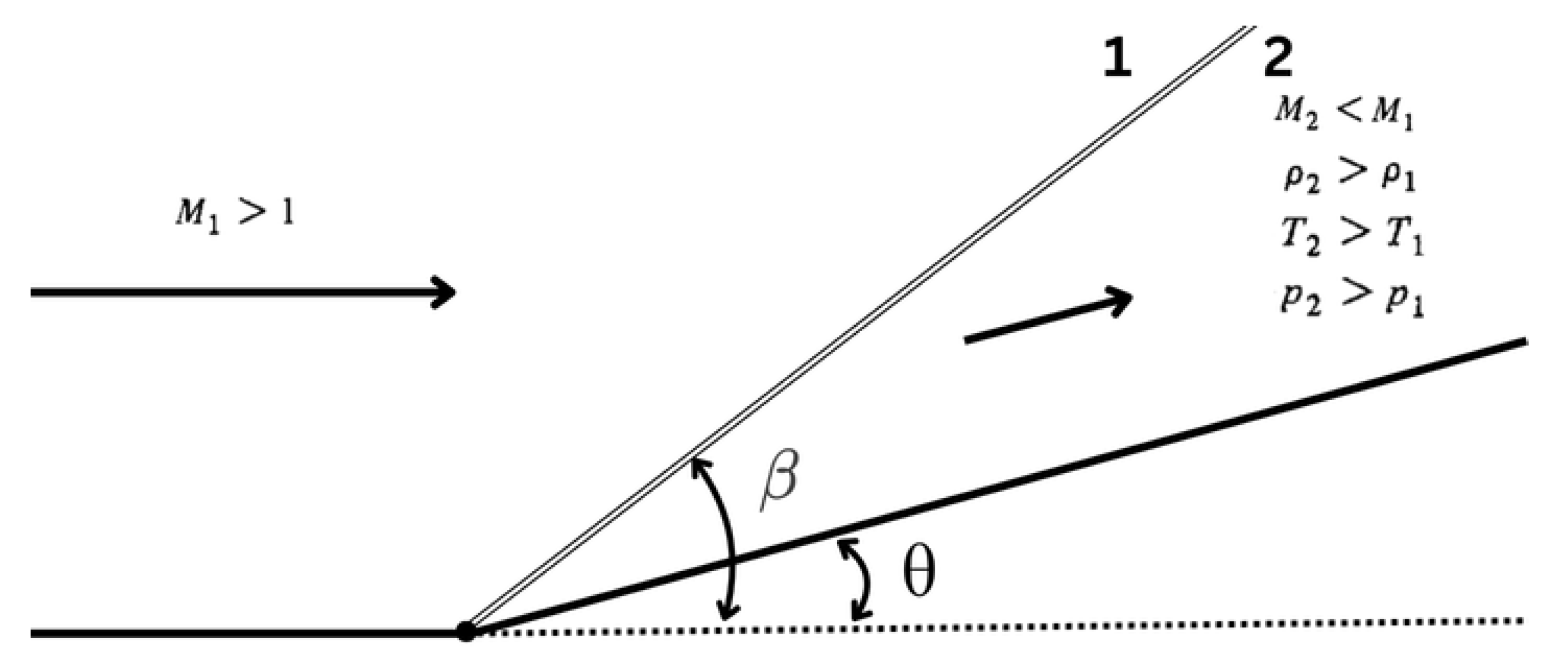

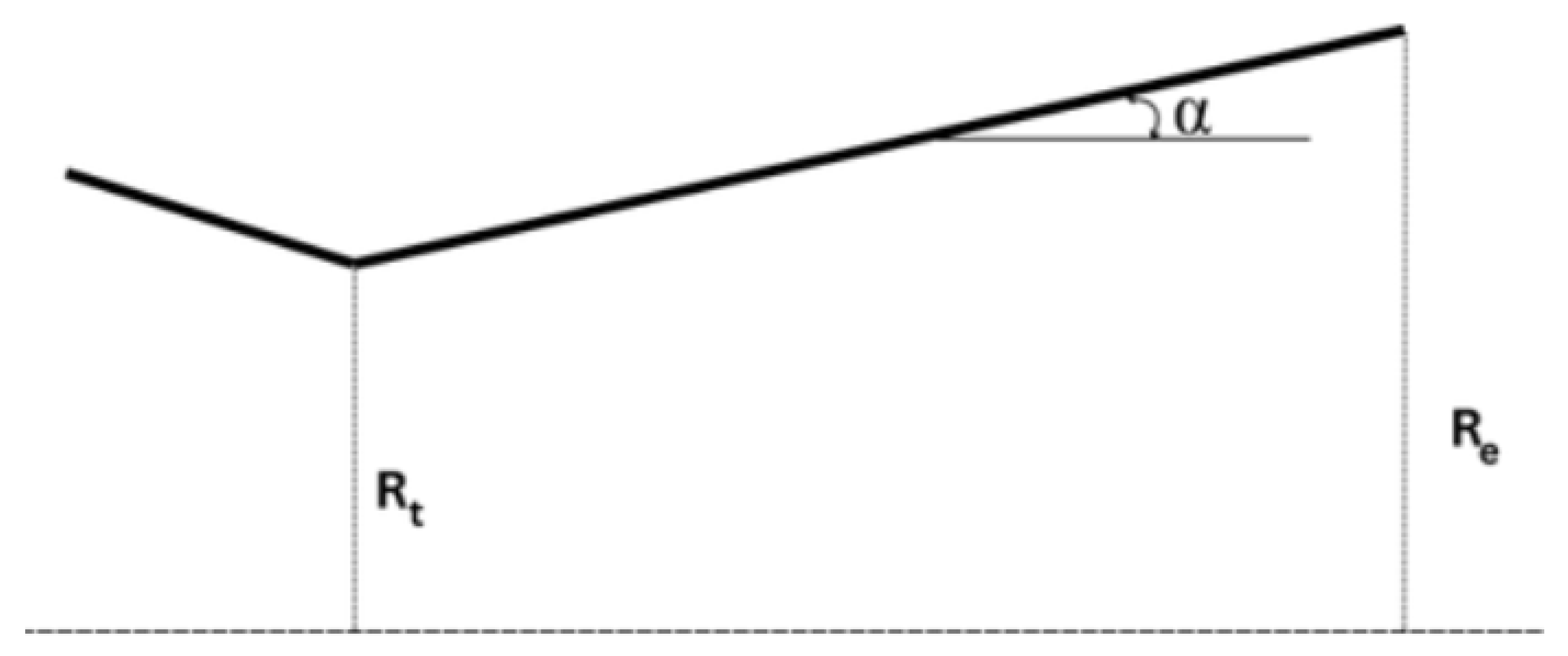

More broadly, shocks are considered oblique, as illustrated by

Figure 4, and are formed when the flow must be deflected at a certain angle,

, due to the presence of a concave surface. The streamlines are always parallel, changing direction discretely at the shock.

The flow is decomposed into two components, one normal to the shock, according to Equation

19, which is analyzed as a normal shock, and one parallel component that is not affected by the shock, as per Equation

20. Note that

represents the shock angle that decomposes the velocity of the incoming flow, and

represents the deviation experienced by the flow after the shock, coinciding with the concavity of the surface.

The Mach number after the oblique shock is obtained by Equation

21. The angles

and

are related to each other according to Equation

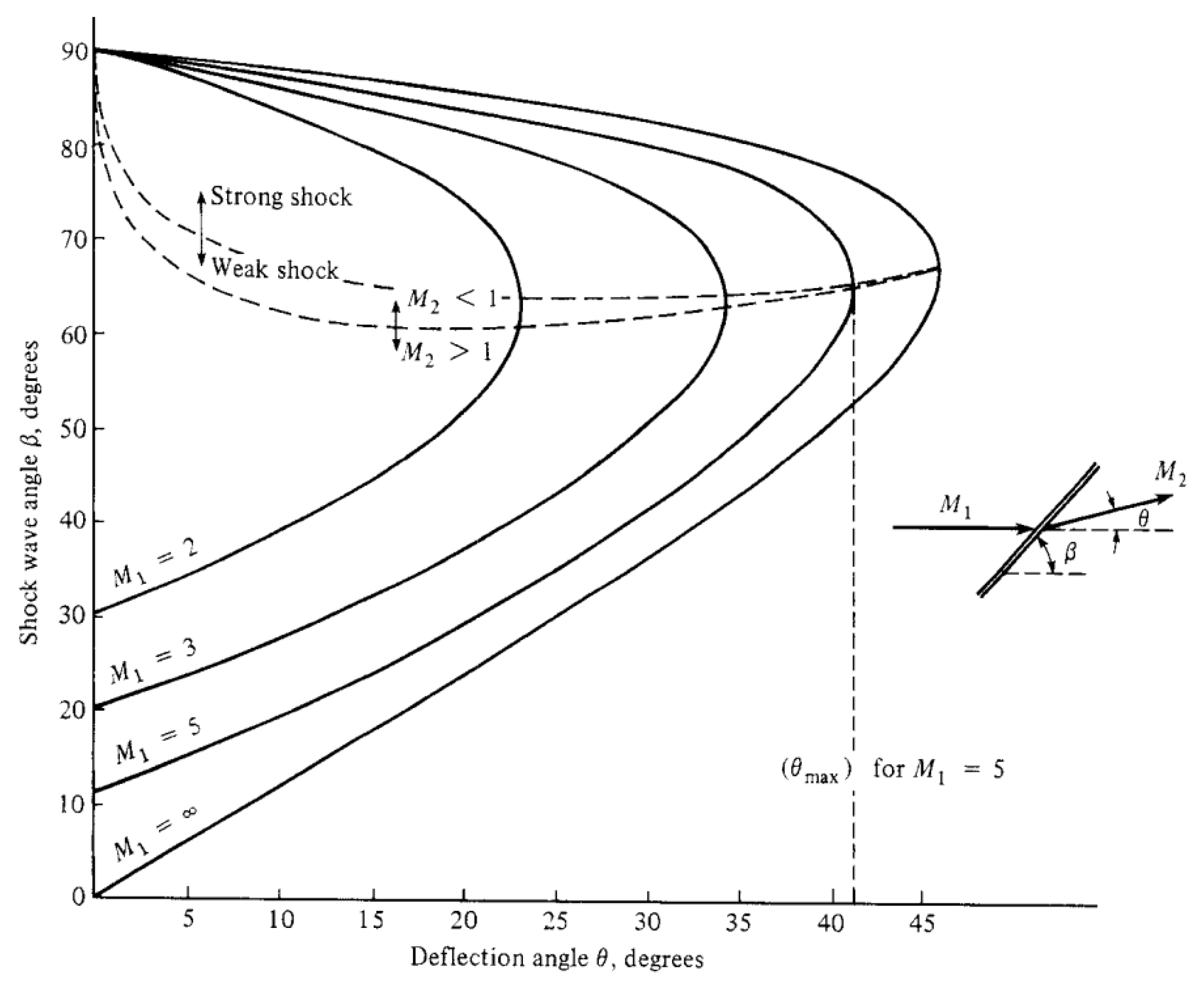

22, which is graphically represented in

Figure 5.

There is a maximum angle to which the flow can be deflected by a straight oblique shock. If the surface has , the shock will be bent and flow detachment may be induced.

Similarly, if the deflection angle is fixed, as the Mach number decreases, the shock angle increases until it reaches a value where the fixed equals the maximum possible deflection angle for that Mach number. Beyond this point, further decreases in the Mach number also do not have a straight shock solution.

For any given deflection angle, there are two possible shock wave angles. The smaller shock angle corresponds to the weak shock solution, with the flow after the shock remaining supersonic . The highest shock angle corresponds to the strong shock solution, with the flow after the shock being subsonic . The occurrence of each solution depends on the pressure conditions downstream in relation to the pre-shock flow. A strong pressure gradient will favor the strong shock solution, while a weaker gradient will favor the weak shock solution.

6.5. Prandtl-Meyer Expansion

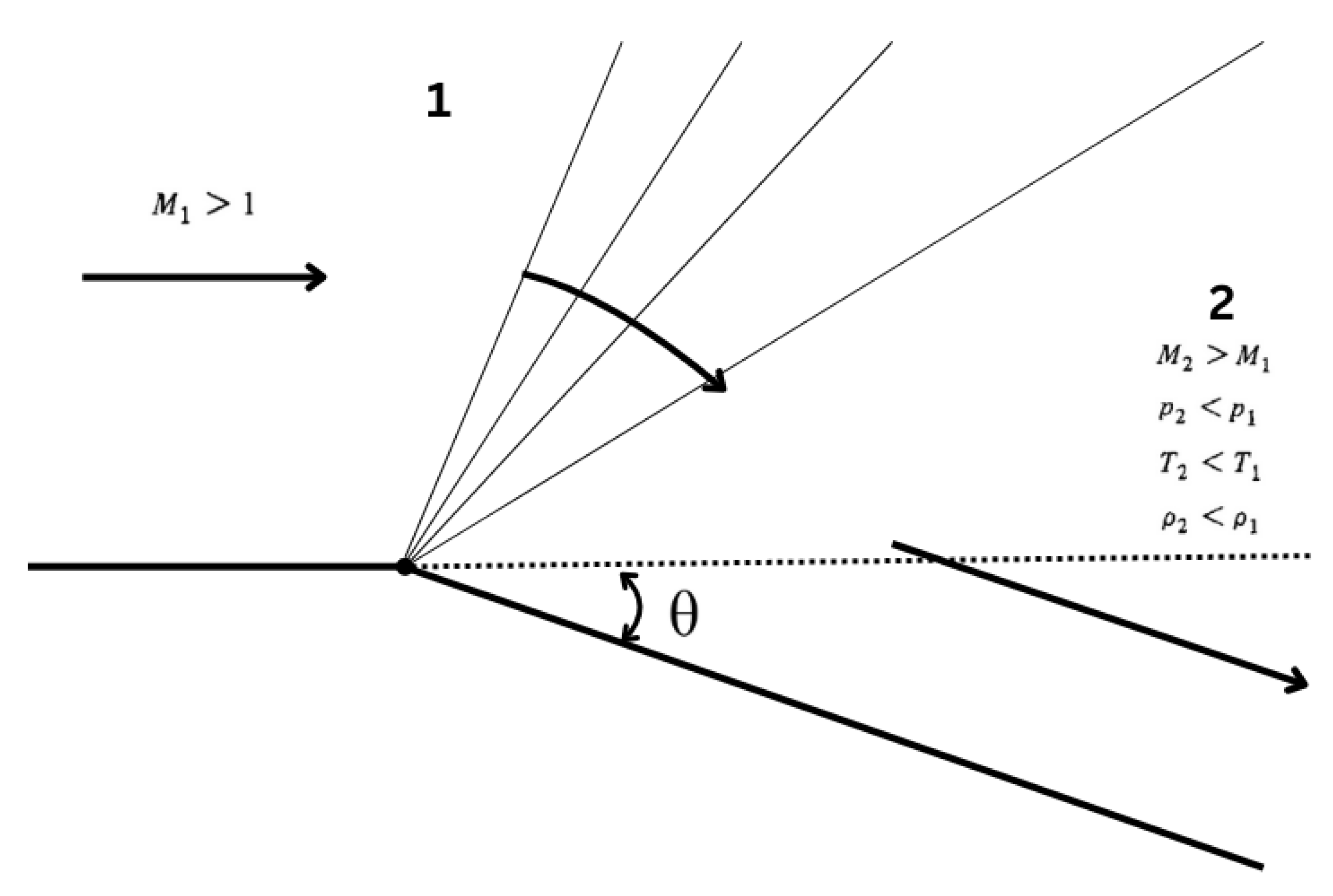

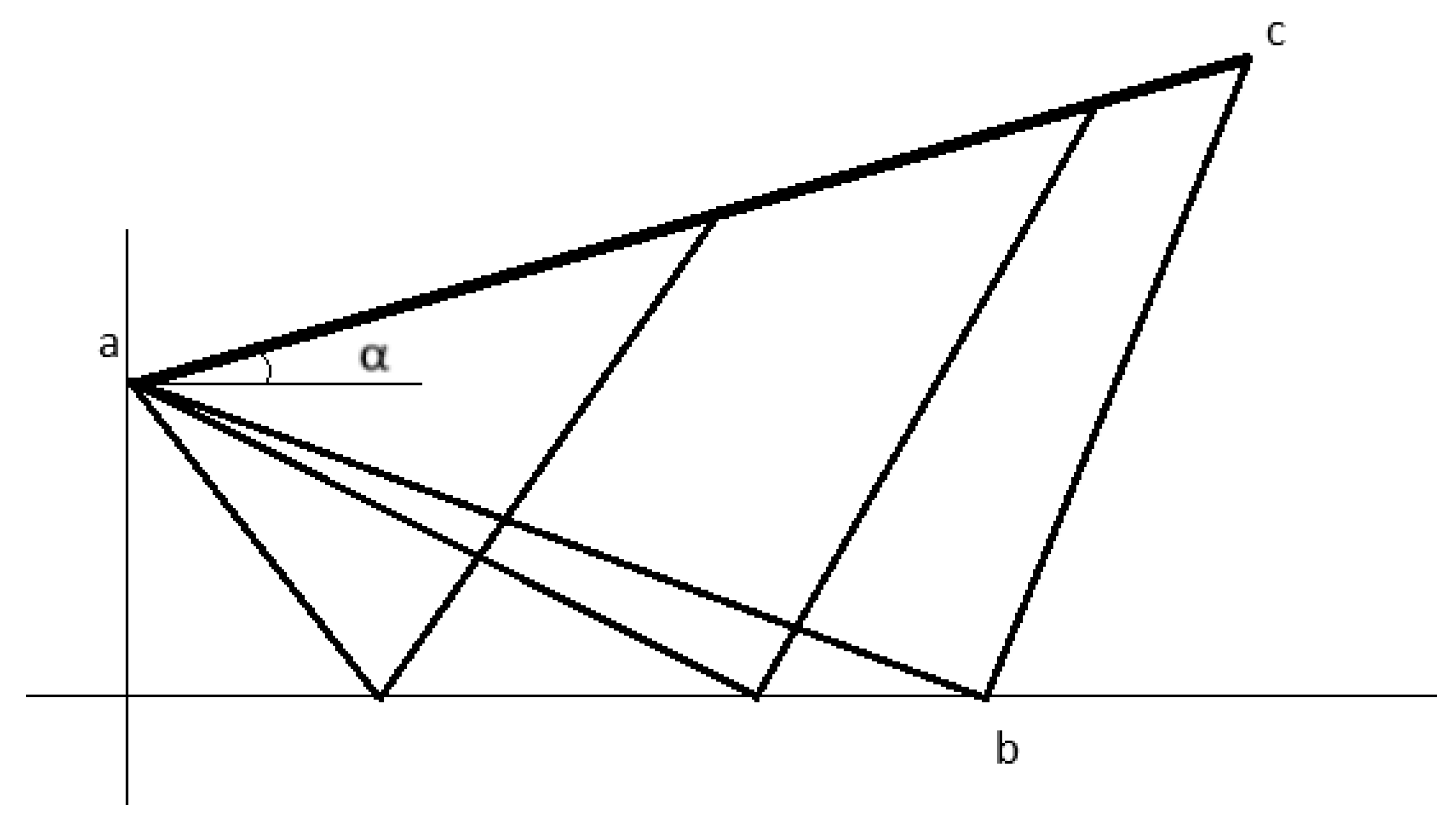

Looking at

Figure 6, when a supersonic flow encounters a convex surface, it must deflect from itself, wich promotes an expansion, as opposed to an oblique shock. Velocity increases, and the density, pressure, and temperature decrease. Also, these changes in properties are so smooth, that they can be assumed to be continuous, corresponding to an isentropic process. This occurs because the expansion is composed of a fan of waves, each of which contributes to infinitesimally accelerate the flow.

Basically, the vertex in

Figure 6 emanates infinitesimal Mach lines, responsible for expanding the flow. This Mach lines are characteristic lines.

Due to the isentropic behavior, the changes in the flow’s temperature and pressure are given by Equations

23 and

24, respectively. Density can be easily calculated using Equation

6 under an ideal gas assumption.

The Prandtl-Meyer angle is a characteristic of the flow, as a function of the Mach number by the definition of Equation

25 . As for the reflection angle, it is simply given as the difference between the Prandtl-Meyer angle before and after the expansion, as stated in Equation

26.

When numerical algorithms are implemented to solve compressible flows, sometimes it is necessary to calculate the Mach number from its associated Prandtl-Meyer angle. Obviously there is no analytical solution for Equation

25 so some inversion methods were developed [

7], one of which is described in

Appendix A.

7. Quasi-1D Flow

Similar to unidimensional flow, quasi-one-dimensional flow represents an improvement as it also allows for variations in area. The assumption of smooth wall angles, prevents shock formation, ensuring isentropy. Although the geometry is two-dimensional, the fluid properties are still assumed to be dependent only on the direction of the moving flow, meaning that they are constant through any given cross-sectional area.

The flow is still considered adiabatic and isentropic. The continuity equation also considers the transversal area, as suggested in Equation

27. This leads to the relation between area and Mach number stated in equation

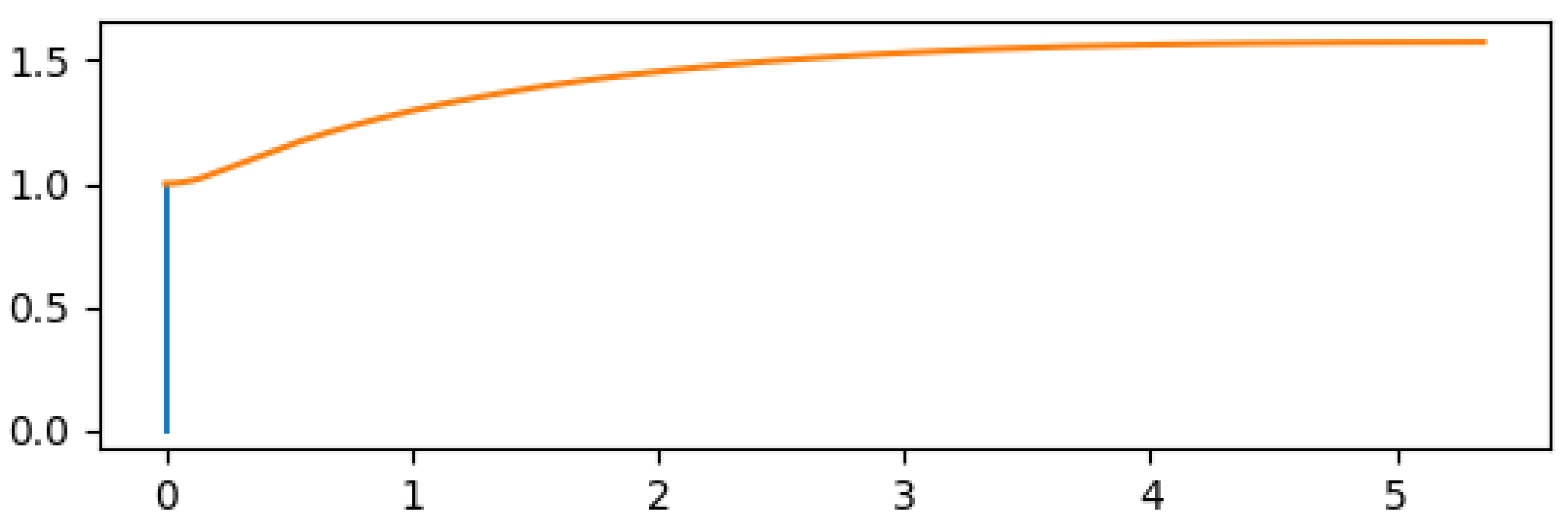

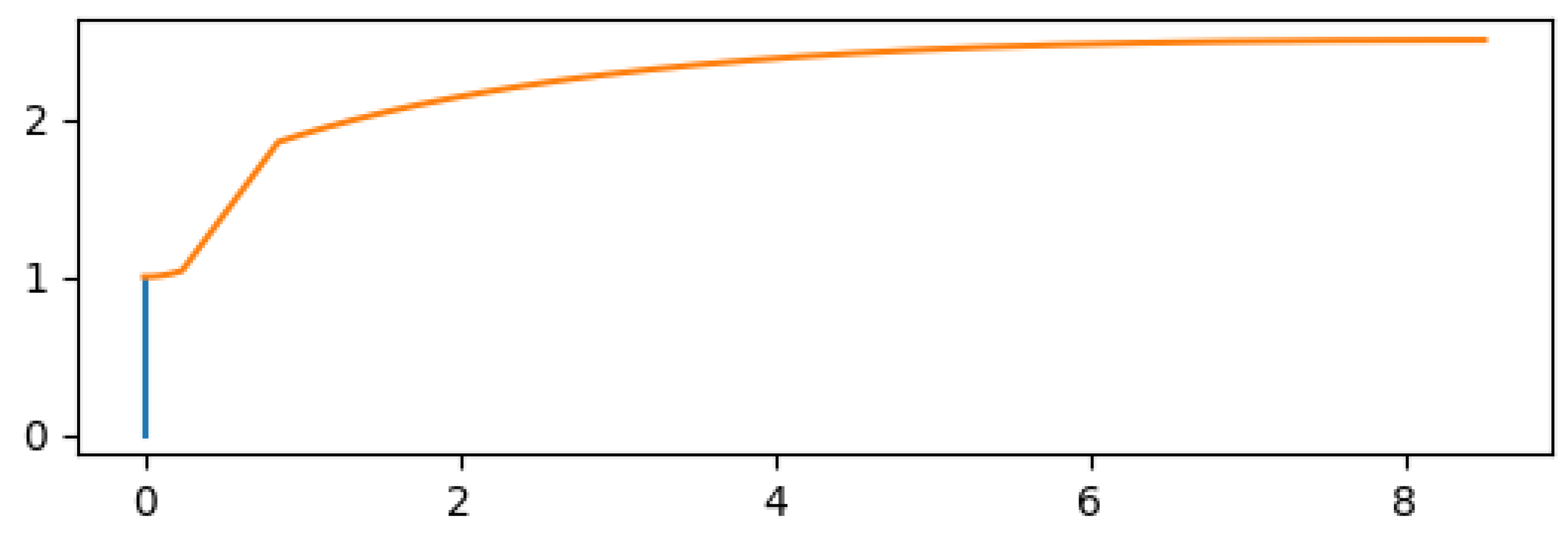

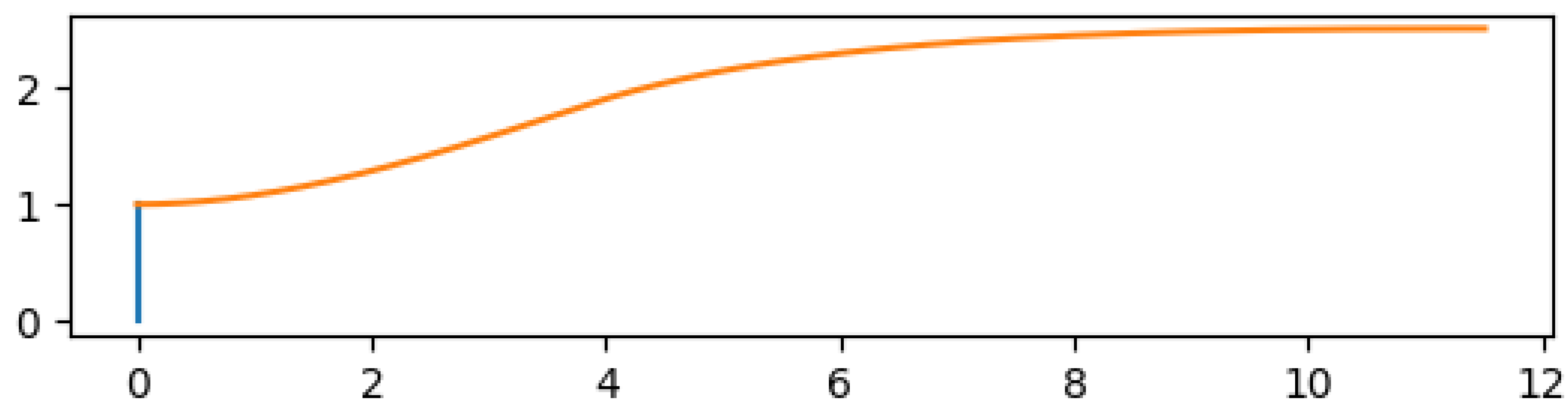

28.

For subsonic velocities, when section area decreases, velocity increases, and vice-versa. In a rocket nozzle, this results in the flow being accelerated by decreasing the area, forming the convergent segment. For supersonic velocities, area increases lead to velocity increases, with the opposite being true. Therefore, if the area increases, as in a rocket nozzle’s divergent, the velocity also increases. As for sonic velocities, Equation

29 suggests that a minimum area is reached, which in a rocket nozzle represents the throat, mathematically reasoning the chocking phenomena.

The area-Mach number relation, given by Equation

30, shows that the Mach number at any location in the duct is a function of the ratio between the local duct area and the sonic throat area. There are two solutions, a subsonic and a supersonic one. As this is an isentropic process, the relations for this type of process can be easily applied to solve the flow properties at any point in the duct.

8. Hypersonic Flow

Contemporary space and defense industries have a keen interest in developing hypersonic vehicles. In the past, hypersonic engineering challenges have already emerged; for instance, during the Apollo 11 mission, reentry into Earth’s atmosphere occurred at a velocity of Mach 36.

At Mach 5, although there isn’t a notable event akin to the sound barrier breakthrough at Mach 1, the flow field begins to be dominated by phenomena that are insignificant at lower velocities. As such, the study of hypersonic aerodynamics becomes a distinct subject within the discipline of compressible aerodynamics.

8.1. Initial Definition

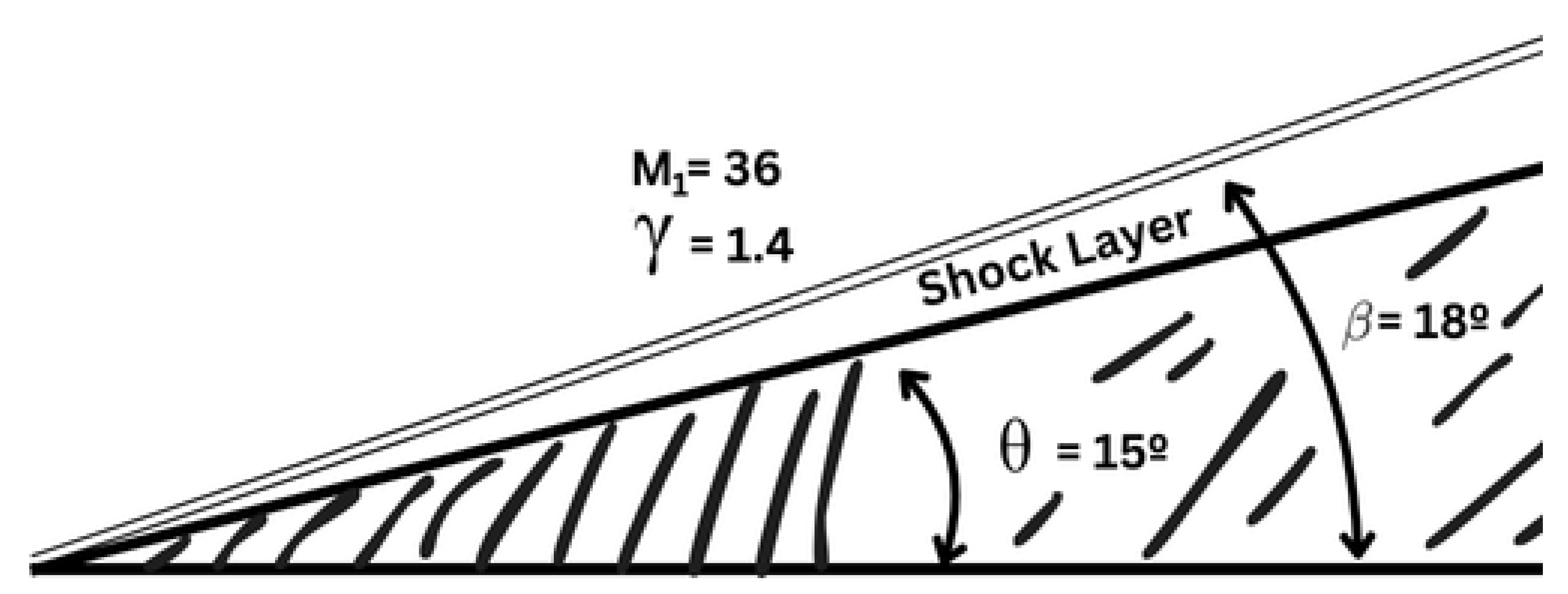

In hypersonic flow, the shock formed on a wedge will be positioned extremely close to the surface, resulting in a very thin shock layer, as illustrated in

Figure 7. The higher the incident Mach number, the stronger the shock, leading to a significant increase in fluid density downstream of the shock. As a consequence, the flow downstream of the shock can more easily "squeeze" into smaller spaces, resulting in a reduction in volume while conserving mass flow. Furthermore, if high enthalpy flow effects are considered, such as chemical reactions in the gas, the shock wave will have an angle even closer to that of the wedge.

The shock wave can interact with the boundary layer, causing it to thicken and leading to modeling complexities, especially for laminar boundary layers. At high Reynolds numbers, the shock layer can be considered inviscid, and Newtonian Theory provides a simple and straightforward method for modeling the fluid dynamics.

The analysis of supersonic flow reveals that entropy increases through a shock and is directly proportional to the shock strength. Consequently, when the flow encounters a blunt nose, different streamlines experience varying degrees of shock strength, resulting in strong entropy gradients around the nose. These gradients extend away from the shock, creating an "entropy layer" around the body. This layer interacts with the boundary layer, posing additional challenges for its analytical modeling.

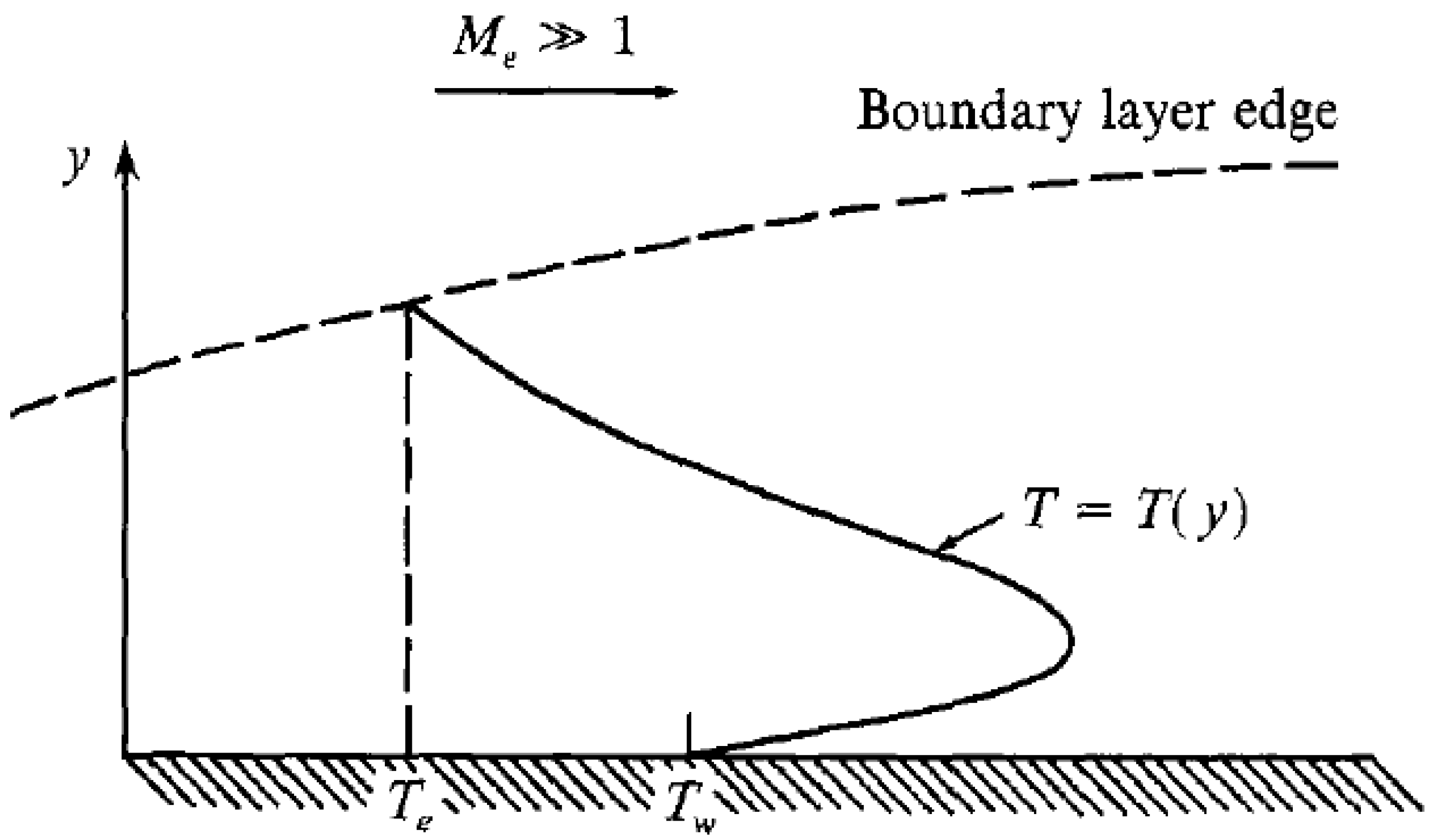

Viscous dissipation occurs as kinetic energy is converted into internal energy due to the velocity profile imposed by the no-slip condition within the boundary layer. This phenomenon leads to an increase in the local static temperature of the flow, as illustrated by

Figure 8, which shows the static temperature profile of a hypersonic boundary layer.

A hypersonic boundary layer is typically thick and develops rapidly due to the high temperatures involved. This increase in temperature leads to higher viscosity coefficients, thickening the boundary layer. Additionally, to maintain mass flow conservation, the thickness of the boundary layer must increase since there’s a decrease in density, keeping pressure constant across a transverse section.

In engineering applications, this thickening of the boundary layer causes a significant displacement of inviscid streamlines, making bodies appear much wider. This displacement can lead to changes in the freestream flow, which further exacerbates the growth of the boundary layer in a feedback loop process known as viscous interaction. This interaction affects calculations of lift, drag, and stability due to its impact on surface pressure distribution.

Friction within the boundary layer dissipates kinetic energy, increasing the static temperature to values where molecular vibration, dissociation, and ionization may occur. These phenomena challenge the assumption of a calorically perfect gas and is further complicated if the vehicle is coated with ablative shielding materials.

Strong shocks in hypersonic flow can significantly elevate the freestream flow temperature, influencing the aerodynamic behavior of the vehicle. Heat transfer rates, including convection heating and radiation from the hot gas in the shock layer, become crucial design parameters in engineering applications. The presence of hot plasma around a reentering vehicle can also pose challenges for communications.

While high enthalpy flows introduce additional complexities, simpler analysis can assume a calorically perfect gas. Hypersonic flow exhibits various phenomena, including thin shock layers, entropy layers, viscous interaction effects, and high temperatures, all of which must be considered in engineering design and analysis.

8.2. Wave Relations

Equations presented previously for shock relations are valid for any Mach number greater than unity, so they can also be applied to hypersonic flow. In fact, for hypersonic flow, some approximations and simplifications can be made, that are important to understand the flow’s behavior.

Most simplifications advent from the fact that every term of

and higher absolves smaller terms when

.

Looking at previous Equations it can be seen that the temperature and pressure ratios can become infinitely large while density and velocity components ratios reach finite limits when .

8.3. Local Surface Inclination Method

Linearized supersonic flow leads to the pressure coefficient given by Equation

38. Therefore, the pressure coeficient is a linear function of the plate inclination, for given freestream conditions. In theory this analysis can be extended to supersonic values.

From Equation

36, obtained as

, a condition

yields

. Similarly, applying the same condition to Equation

32 results in

. By considering mass conservation, the shock angle aligns with the surface inclination, i.e.,

. Thus, Equation

39 is derived, which coincides with the

Newtonian Theory.

It can be concluded that as and , Newtonian Theory provides a better approximation for modeling the flow. However, real hypersonic flow may not adhere strictly to these conditions, rendering Newtonian Theory inaccurate when compared to experimental results. Nevertheless, the theory yields results accurate enough for preliminary analyses where simplicity is desired.

With Newtonian Theory, the aerodynamic behavior of a flat plate is described by Equations

40,

41, and

42.

The lift-to-drag ratio of the plate increases as the plate inclination decreases, approaching infinity when . However, when friction effects are considered, drag will always have a finite value, leading as . Unlike subsonic and supersonic flow, lift is not linear for , but after, peaking at .

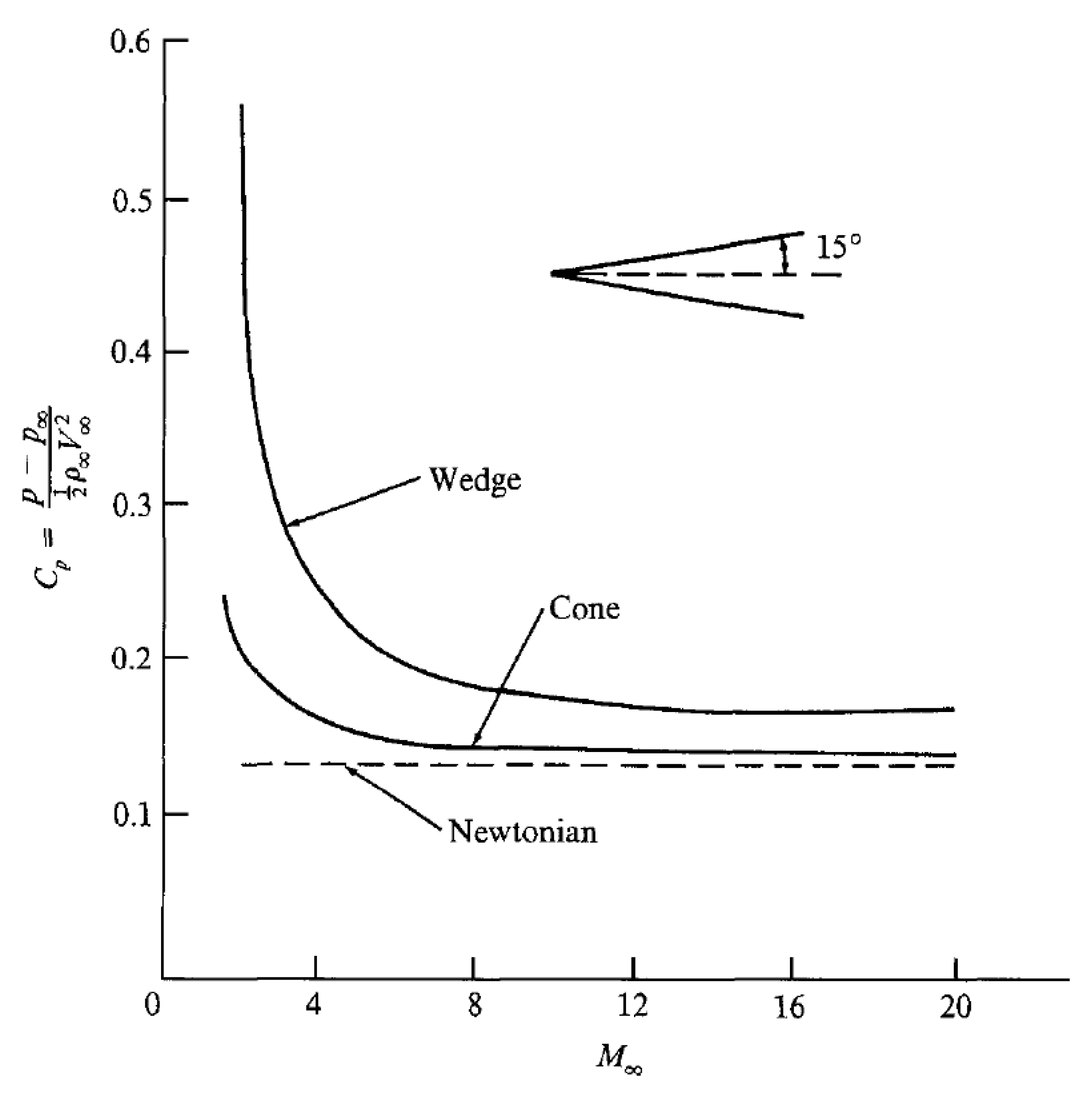

Experimental results of the pressure coefficient for various geometries compared with Newtonian Theory are illustrated in

Figure 9. It is evident that Newtonian Theory becomes more accurate with increasing Mach number, particularly beyond

. Additionally, there is higher accuracy for 3D objects (cone) compared to 2D objects (wedge).

There are other surface inclination methods for hypersonic flow such as the tangent wedge, tangent cone and shock-expansion.

9. High Enthalpy Flow

Apollo 11 mission reentered the atmosphere at a velocity of 11 km/s, equivalent to Mach 32.5 at an altitude of 53 km. Analyzing the strong shock that forms at the blunt nose of the vehicle, assuming a calorically perfect gas, results in a shock layer with a static temperature of 58300 K, which is incorrect. When heating the air, before reaching such temperature, the gas gets vibrationally excited and can even chemically react or ionize, absorbing energy. In fact, the shock layer is composed by a partially ionized plasma. When the previous analysis is performed but with a chemically reacting gas, and the adiabatic index becomes a function of both pressure and temperature, static temperature is "just" 11600 K.

If atmospheric air is heated at a pressure of , oxygen and nitrogen molecules will begin to dissociate at temperatures of and , respectively. Once the temperature reaches , all the molecules have fully dissociated, and atom ionization begins. From a calorically perfect gas perspective, these phenomena "consume" heat that does not contribute to an increase in the system’s temperature.

9.1. Microscopic Description of Gases

Quantum mechanics dictates that particles can only possess quantized values of energy, with the lowest value observed at , denoted by and referred to as the zero-point energy, defining the ground state. The energy of a molecule can be measured relative to this ground state, such that .

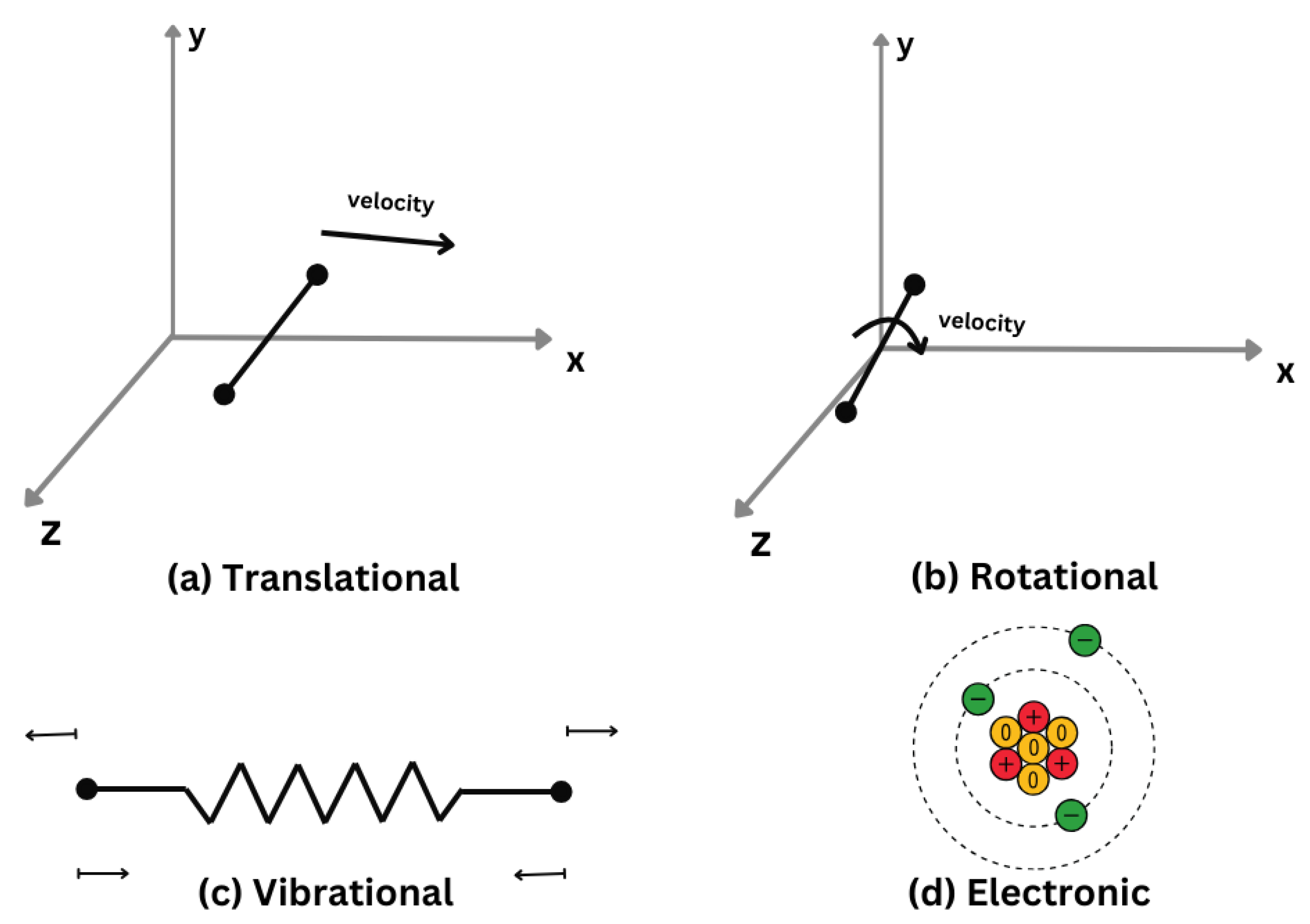

The energy of a molecule is the sum of four energy modes, as suggested by Equation

43. These energy modes are quantized, associated with a particular atomic behavior.

9.1.1. Translational Energy

As depicted in

Figure 10a), this energetic mode pertains to the translational motion of the center of mass of a molecule. It encompasses the associated kinetic translational energy, which can be further decomposed into three degrees of geometric and thermal freedom (one for each orthogonal direction).

All quantized modes of translational energy are closely spaced, giving the illusion of continuous changes in energy. Equation

44 quantifies this energetic mode, where

are quantum integer numbers, h is the Planck’s constant and

linear dimensions that describe the system’s volume.

9.1.2. Rotational Energy

Besides translation, a molecule can rotate around the orthogonal axis around its center of mass, as seen in

Figure 10b). Both kinetic rotational energy and the moment of inertia contribute to this energetic mode.

Similar to translational motion, rotational motion also exhibits three degrees of geometric and thermal freedom. However, linear molecules have negligible rotation around the z-axis, resulting in only two degrees of freedom.

The energy levels become more distant with increasing energy, indicating that it takes more energy to transition from one level to the next. It is the only energetic mode that has a total value of zero at the ground state.

Rotational energy is defined by Equation

45, where J is the rotational quantum number and I the moment of inertia of the molecule.

9.1.3. Vibrational Energy

Atoms within a molecule oscillate around their equilibrium positions. For a diatomic molecule, this motion can be visualized as a spring connecting the two atoms, as depicted in

Figure 10c).

In this analogy, the vibrational mode involves kinetic energy associated with the linear motion of each atom and potential energy resulting from intramolecular forces. Despite having only one degree of geometric freedom, diatomic molecules exhibit two degrees of thermal freedom. However, polyatomic molecules are more complex, featuring multiple vibrational modes.

The spacing between vibrational energy levels is even greater than that of rotational energy levels, but this spacing decreases. Consequently, it requires less energy to transition from one vibrational level to the next compared to transitioning between rotational levels.

Vibrational energy is defined by Equation

46, where n is the vibrational quantum integer number and v the fundamental vibrational frequency of the molecule.

9.1.4. Electronic Energy

An atom, as depicted in

Figure 10d), consists of electrons orbiting the nucleus with a certain rotational kinetic energy and potential energy arising from their electromagnetic interaction.

In this context, the concepts of geometric and thermal degrees of freedom become obsolete. Additionally, it’s easy to understand why the total electronic energy is above zero at the ground state. If it were null, it would imply that the electrons had collapsed into the nucleus.

The spacing between each energy level in the electronic mode is the largest among all energetic modes, and it decreases with increasing energy.

9.1.5. Macrostate

The molecules that composed a thermodynamic system will mandatorily occupy quantized energy levels.

is the number of molecules that inhabit the level of energy

, constituting that level’s population. The total energy of the system is given by Equation 47.

Due to intermolecular collisions, the molecules within a system are always changing their energy level, meaning the population distribution is constantly changing. Each different population distribution is called a macrostate.

There’s a macrostate that is the most likely to occur at any given time. Statistical mechanics delivers the tools to predict the most likely macrostate, with it corresponding to thermodynamic equilibrium.

Within an energy level, there are some microstates, that its population can inhabit, without changing its macrostate. Molecular collisions also promote the alternating of microstates internally to the energy level.

Since each microstate is considered to take place with equal probability, the most likely macrostate is the one that has the highest number of microstates associated. Usually, there’s a single macrostate of the system that has considerably many more microstates than the others due to the high number of molecules that constitute the typical system for engineering applications.

9.1.6. Microstate

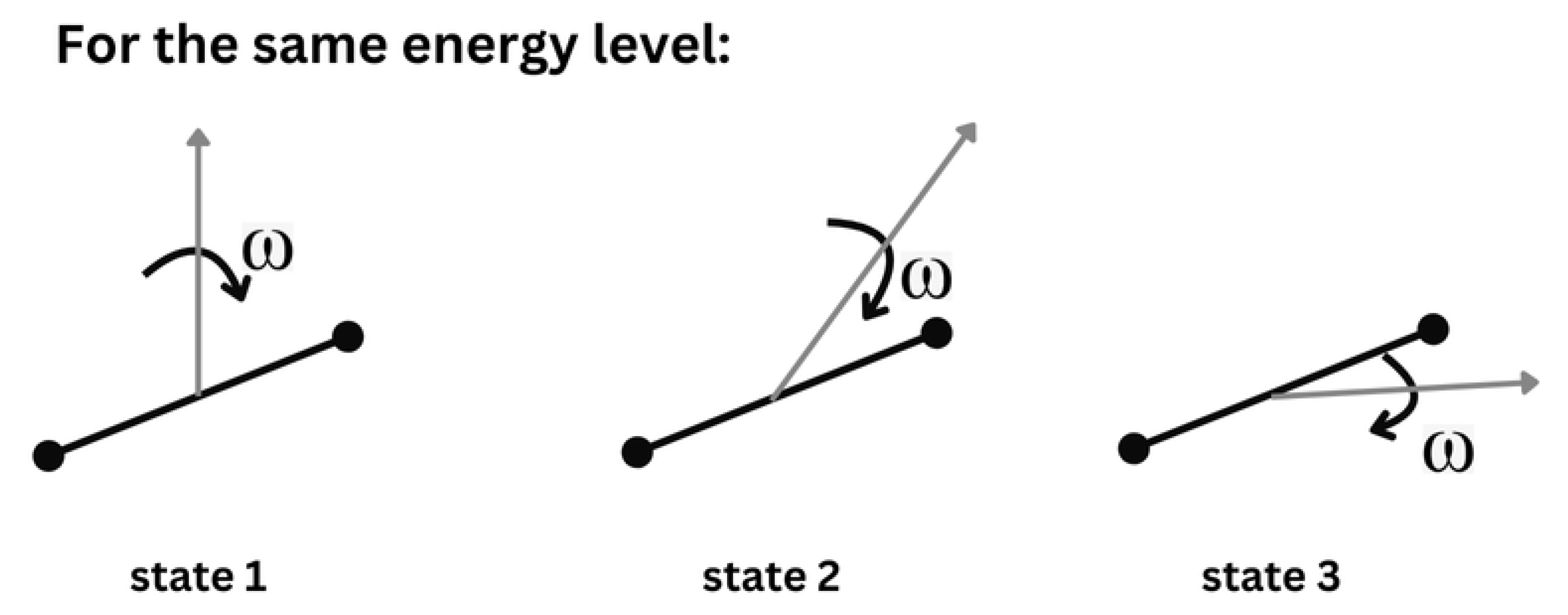

The angular momentum of a given molecule, being a vector quantity, can have different directions but all with the same associated energy

. The angular momentum is also quantized, meaning only a few directions are allowed. For example, in

Figure 11, only the three depicted orientations are allowed, without intermediate states. Analogous phenomenon occurs for vibrational and electronic modes.

What was described are distinguishable scenarios among the population of a given energy level. So, each possible variation within an energy level is called a degeneracy or statistical weight, and each is represented by .

The microstate is defined as the distribution of the population among the degenerate states of a certain energy level.

There are two theoretical cases for calculating the population of each energy level for the most likely macrostate.

9.1.7. Boson

If a molecule has an even number of elementary particles, it will follow the Bose-Einstein statistical distribution.

Each microstate can be inhabited by an unlimited number of the molecules from the corresponding energy level.

Equation

48 represents the number of microstates of the

indistinguishable molecules from energy level

that has

degenerate states.

Thermodynamic probability,

W, can be defined as the sum of Equation

48 for the several energy levels

j that the molecules of the system can occupy. Put simply, it measures the disorder of the system by counting the number of possible microstates within a macrostate.

Each macrostate will have different values of

W, and the most probable macrostate is the one with the largest value of

W. To find it,

W must be maximized, a task from which Equation

49 emerges. The symbol * denotes the most likely macrostate and is used to define the population

for each energy level

, thereby defining a macrostate.

9.1.8. Fermion

If a molecule has an odd number of elementary particles, it will obey the Fermi-Dirac statistical distribution.

Each microstate can only be inhabited by a single molecule at a time, so

. Equation

50 gives the number of microstates for an energy level.

Analogously to the boson, the most likely macrostate for a fermion is given by Equation

51.

9.1.9. Boltzmann Distribution

At low temperatures (like ), the differences between bosons and fermions are evident as molecules densely occupy the lower levels of energy. But at high temperatures, there are many more energy levels being inhabited and so, each population is scarce, meaning .

So the population distribution is given for both bosons and fermions by Equation

52. This is called the Boltzmann distribution and is applicable for temperatures considerably above

, like in most engineering applications.

A partition function is defined in Equation

53 that is function of the systems temperature and volume.

can be obtained by combining both classical and statistical mechanics in Equation

54, where

k is the Boltzmann constant.

From zero-point energetic measurements and some mathematical manipulation,

can be replaced, yielding Equation

55.

So, in a system with

N particles, quantum mechanics states that there are well-defined quantized energy levels

with a certain

amount of degenerate states each, on which molecules will be distributed. Equation

55 precisely determines the number of molecules

on each energy level

when the system reaches thermodynamic equilibrium at a certain temperature and volume.

9.1.10. Partition Function as a Function of Volume and Temperature

The partition function of a molecule is the product of the partition function for each energetic mode, as suggested in Equation

56. The volume dependence arises from the multiplication of the spatial dimension of the molecule

in Equation

57. Temperature dependence is evident in all energetic modes.

To note, Equation

59 is only applicable to diatomic molecules, as polyatomic molecules possess multiple and complex vibrational modes. Equation

60 takes into account considerations from spectroscopic data concerning the electronic levels

. The value of

is relatively high, such that for

, a second-degree expansion provides accurate results.

9.1.11. Microscopic Thermodynamic Properties

In equilibrium, the internal energy of the system is obtained with Equation

61, measured above the zero-point. At constant volume, in a system with

N molecules, it can be generalized to Equation

62. Often, internal energy per unit mass is desired, so Equation

63 can be used, where

R represents the universal gas constant.

Other thermodynamic properties can be derived from statistical mechanics, as shown in Equations

64,

65, and

66 for enthalpy, entropy, and pressure, respectively.

9.2. Thermodynamic Properties Evolution

The Equipartition Theorem states that each thermal degree of freedom contributes

to the internal energy of a gas. This applies to both translational and rotational internal energy, as shown in Equations

67 and

68, respectively.

However, the Equipartition Theorem does not apply to the vibrational mode. This is because it was formulated using classical mechanics based on macroscopic observations, without considering microscopic and quantum mechanics. Typically,

, and its value for diatomic molecules is given in Equation

69.

The sensible energy of the system is the sum of the previous three energetic modes and the electronic mode

, for which a specific formula is not provided. Both the sensible energy and the specific heat at constant volume, depicted in Equation

70, are functions of temperature alone in a thermally perfect gas. This is due to the disregard of intermolecular interactions, which simplifies the equally likely microstates.

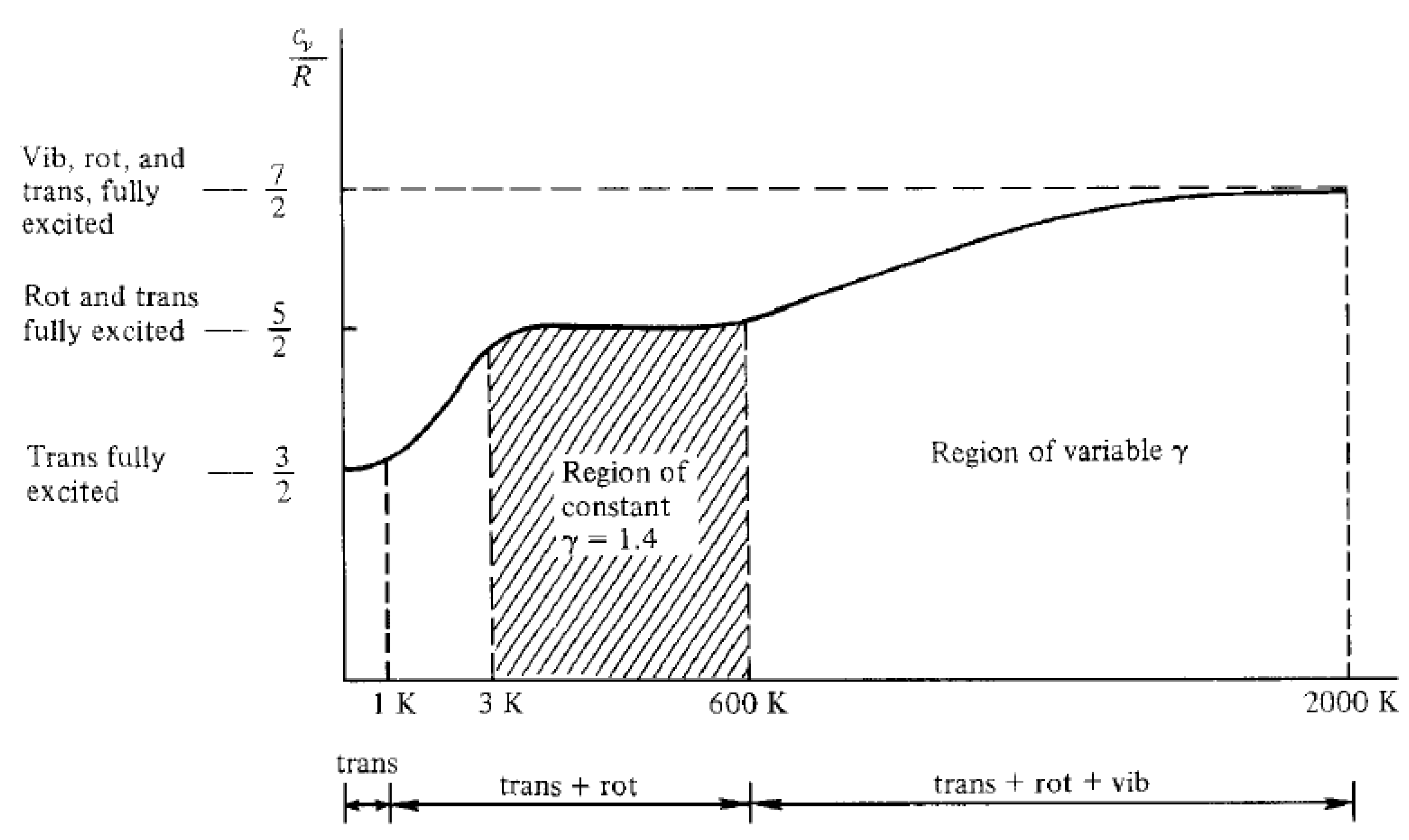

Now, the definition of a calorically perfect gas also becomes more evident. For air, , , and . It is clear that this simplification only considers translational and rotational energies, which is fairly valid for , as there are little to no effects from the vibrational mode.

Looking at

Figure 12, one could expect

as

, but this is not true, as at higher temperatures, effects from dissociation and ionization change

. Another aspect from the graphic is that at

, there’s only a contribution from the translational mode and

, with the initial increases in temperature responsible for increasing rotational energy from a null value.

9.3. Chemical Equilibrium

Consider the chemical reaction described by Equation

71, derivated from the generic form of Equation

72. Chemical equilibrium is achieved when the system has matured to the point where its composition (quantity of each species) is constant, and each direction of the chemical equation is occurring at the same pace.

Noting that

is the number of molecules of the species

x in the system and

the number of molecules of the species

x in the energy level

, the total energy of the system is given by Equation

73.

The microscopic calculation of chemical equilibrium can be translated, once again, to finding the most likely macrostate, taking into account the energy levels and respective degenerate states of all the molecular species that intervene in the reaction. The population for each energy level is obtained by relating it to the partition function as per Equations

77 to

79.

9.3.1. Equilibrium Constant

The law of mass action is obtained by relating the several species of reactants and products, based on the zero-point energy as shown in Equation

80. Nonetheless, it is not practical to measure the number of molecules of the system, so Equation

81 relates the partial fraction of each species to the partition functions. The latter are directly dependent on volume, so the partial pressure fraction becomes solely a function of temperature, introducing the concept of a thermally variable

equilibrium constant.

The equilibrium constant is more precisely defined for a general chemical reaction in Equation

82, where

represents the stoichiometric coefficient of the species

i, with positive values for products and negative values for reactants.

9.3.2. Equilibrium Calculation

Qualitatively speaking, the equilibrium composition depends on temperature and pressure. To implement a proper algorithm capable of solving the equilibrium of a gaseous mixture, all relevant chemical reactions and their respective equilibrium constants must be defined. As a rule of thumb, for a mixture with x species containing y different elements, x-y independent chemical reactions must be considered. It’s likely to have more molecular species than equations, so other concepts need to be taken into account, such as conservation of atomic nuclei or Dalton’s law for gas partial pressure.

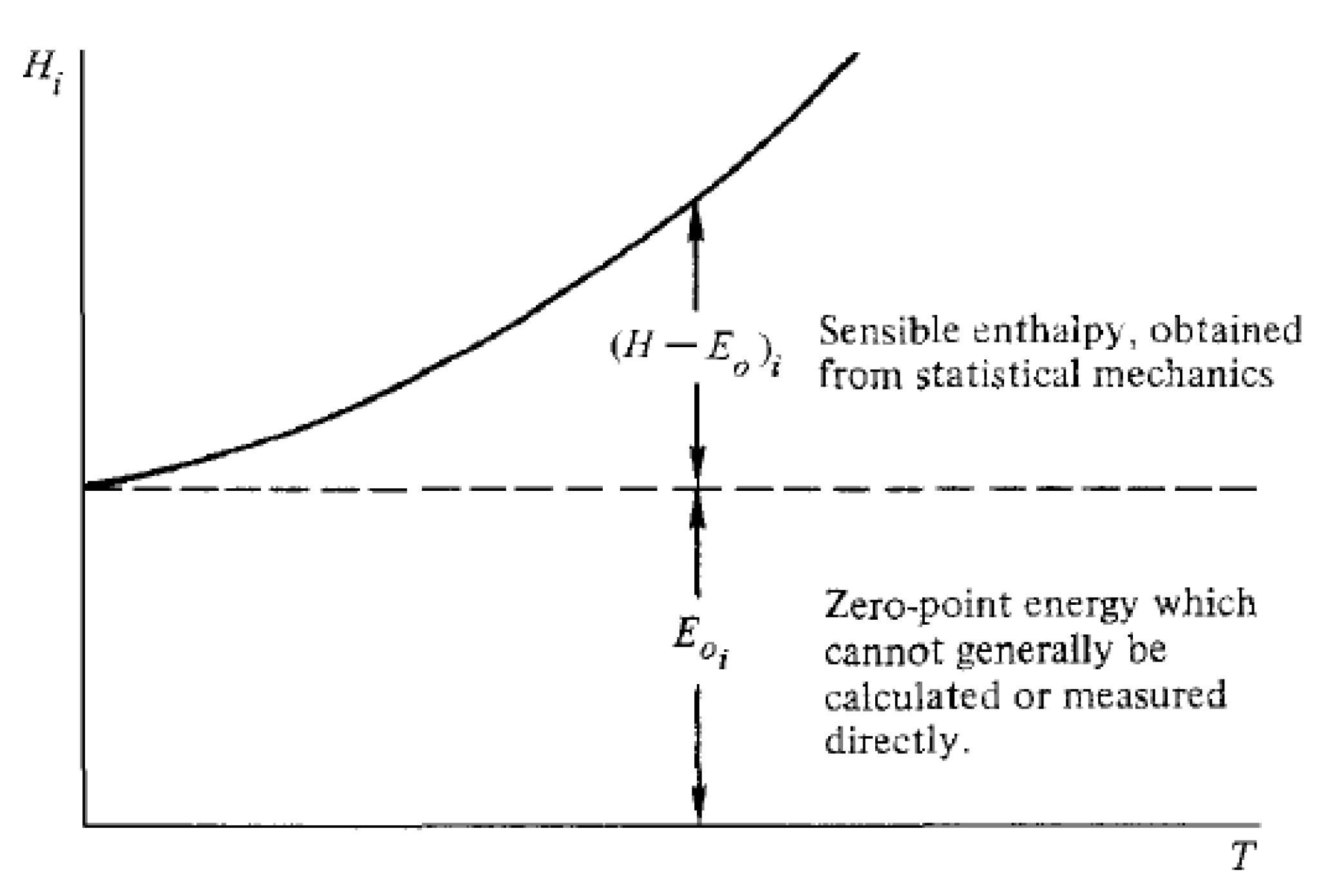

9.3.3. Equilibrium Enthalpy

Equation

83 represents the absolute enthalpy of a given species i, relating sensible enthalpy to the zero-point energy.

Figure 13 illustrates the concept. The total absolute enthalpy of the entire mixture can be given by Equation

84, taking into account the mole-mass ratio

.

Unfortunately, absolute enthalpy cannot be measured, a fact that does not undermine chemical studies, as the pertinent concept is the variation of enthalpy. In a chemically reacting mixture, it is necessary to establish a reference level for enthalpy, relative to which all energies are measured.

Equation

85 establishes the enthalpy variation for a system, with the second term relating to the heat of formation. This heat represents the energy released or absorbed during the formation of a given species from its constituent elements (for example, the natural element for species containing oxygen is

) under standard conditions (

).

The heat of standard formation can be defined at absolute zero, where the temperature of both reactants and products is . In chemical reactions, the difference between the zero-point energy of the products and the reactants equals the difference between the heats of formation at . The heat of formation at absolute zero is considered the "effective" zero-point energy.

Equation

86 defines the total enthalpy, with the first term representing the sensible enthalpy calculated from statistical mechanics, and the second term reflecting the effective zero-point energy derived from the heat of formation at absolute zero, which has been experimentally determined and tabulated.

9.4. Nonequilibrium Systems

Chemical processes take time to occur and depend on molecular collisions, meaning processes are not instantaneous. The molecular collision frequency Z, proportional to , represents the number of collisions per second per molecule.

For example, an molecule needs around 20,000 collisions before becoming vibrationally excited. More broadly, the number of collisions depends on the molecule and its kinetic energy (i.e., its temperature). Increasing the temperature of the system leads to more violent collisions, which may provoke dissociation. For example, the molecule needs around 200,000 collisions to dissociate into atomic oxygen.

A system in chemical nonequilibrium simply hasn’t had enough time for all the necessary molecular collisions to occur and achieve a constant composition, pressure, and temperature at its chemical equilibrium. For instance, right downstream from a shock, the flow will have a non-equilibrium region due to pressure and temperature changes.

9.4.1. Vibrational Rate Equations

The expected number of transitions of the vibrational mode from level i to level is defined as the transition probability . Its product with the molecular collision frequency Z gives the number of transitions per particle per second, represented by . Further multiplying by the number of molecules in the system gives the number of transitions from vibrational level i to per second.

Often, a given energy level will receive and give molecules more likely to its neighboring energy levels. So, the population of the energy level

will vary accordingly with Equation

87.

Studying nonequilibrium conditions deepens the understanding of chemical equilibrium. For instance, the principle of detailed balancing states that in chemical equilibrium, the number of transitions from to and vice versa needs to be equal, in fact .

In a nonequilibrium situation, an equilibrium vibrational energy can be established so the system moves in that direction. However, as the vibrational energy decreases, it is transferred to translational energy, increasing the temperature, which, in turn, raises the expected equilibrium vibrational energy to which the system is converging.

Equation

88 allows for the modeling of the vibrational energy as the system moves in the direction of chemical equilibrium. It’s important to note that, besides the current vibrational energy

, the expected equilibrium vibrational energy

is also a function of time.

represents the model’s relaxation factor, which depends on the system’s temperature and pressure and combines the transition probability

and collision frequency

Z.

9.4.2. Rate of Chemical Reactions

A given chemical reaction will have two equilibrium constants,

and

, referring to the forward and backward directions of the chemical equation. The rate of change in concentration of the reactant participant

for the forward and backward reactions is given by Equations

89 and

90, respectively. Equation

91 represents the net rate in the system.

The entire chemical equation can be modeled with an equilibrium constant

K defined in Equation

92, with the prefix c if referring to species concentration or p if referring to species partial pressure. The equilibrium constants for most generic chemical equations have already been experimentally found.

9.5. Modeling of High Enthalpy Flow

Chemical equilibrium denotes a constant chemical composition of the system, with consistent partial pressure of gaseous species. Thermodynamic equilibrium occurs when the system lacks pressure, temperature, velocity, and species concentration gradients, indicating that the energy levels are populated in accordance with the Boltzmann distribution.

When a system is in both chemical and thermodynamic equilibrium, it is referred to as being in complete thermodynamic equilibrium. However, in practical terms, this state is only achieved in a stationary gas and does not accurately represent flows.

It’s crucial to note that the Mach number loses its relevance in high enthalpy flows and, in nonequilibrium models, it forfeits its physical significance. Additionally, specific heats exhibit significant oscillations in value, making them less commonly used.

9.5.1. Local Equilibrium

The flow expanding in a rocket nozzle typically does not achieve complete thermodynamic equilibrium. However, if pressure and temperature gradients are sufficiently small, infinitesimal equilibrium can be assumed.

In this context, equilibrium is calculated for each point in the flow based on local pressure and temperature conditions, implying an infinite chemical rate of change.

For instance, through a shock, the temperature increase can lead to the gas becoming vibrationally activated and chemically reactive. To calculate the flow properties after the shock, the following iterative method can be employed:

Assume an initial value for ( is often used);

Calculate

with Equation

93;

Calculate

with Equation

94;

Calculate as a function of and using equations of state;

Calculate the new ;

Return to step 2. In case and have converge, follow to step 7;

With and calculate using equations of state;

Calculate

with Equation

95.

In a calorically perfect gas, the conditions downstream of the shock depend solely on the upstream Mach number . However, in a chemically reacting gas, properties depend on the local equilibrium established by and , and consequently on the upstream temperature , pressure , and velocity magnitude . For a thermally perfect gas, the pressure dependence is disregarded.

Equation 96 presents the equilibrium velocity of sound, which is established under the assumption that pressure and temperature within the shock wave remain constant and in local equilibrium.

9.5.2. Frozen Flow

If chemical rates are considered null, the gas composition remains constant, allowing for analogies to a calorically perfect gas. However, this method can only be applied under the assumption of inviscid flow, as diffusion could alter the local gas composition.

A vibrationally frozen flow can be established, resulting in lower predicted temperatures since frozen energy is not transferred to other energetic modes. If the flow is also chemically frozen, specific heats remain constant. Equations 97 and 98 represent the specific heats as the sum of the frozen specific heat and the contribution due to chemical reactions. The additional contribution from chemical reactions is often dominant in terms of magnitude.

Equivalent properties can be employed, such as considering the velocity at which sound would travel if the flow were not chemically reacting (frozen speed of sound, ) or the adiabatic index to plot an isentropic expansion (effective adiabatic index ). Although this approach improves results, they are still deficient in accuracy compared to numerical solutions.

9.5.3. Nonequilibrium Numerical Modulation

So, for chemical reactions with a finite, non-zero rate, numerical solutions to the governing equations must be employed. Chemical composition becomes a function not only of pressure, temperature, and velocity magnitude but also of the chemical reaction rate and duct geometry.

The continuity equation is split for each chemical species in the flow, as shown in Equation

99. Here,

represents the local rate of change of the species

i due to chemical reactions, reflecting Equation

91. If viscosity is considered, a diffusive term must be added. The other governing equations undergo similar considerations.

9.5.4. High Enthalpy Shock

In a shockwave, the conversion of the flow’s kinetic energy into molecular internal energy occurs. In a calorically perfect gas, all of this energy is delivered to translational and rotational energy modes, resulting in a higher predicted temperature, .

However, in a thermally perfect gas, the internal energy is distributed among not only translational and rotational modes but also vibrational modes, and even zero-point energies in the case of chemically reacting gas. This means that will be lower compared to the calorically perfect gas case.

Pressure, on the other hand, is less sensitive to these energy distributions as it is a "mechanical" property, depending mostly on the flow conditions themselves rather than on thermodynamics. A higher pressure upstream, , will result in a higher pressure downstream, , which can retard phenomena such as dissociation and ionization, leading to a higher downstream temperature as translational and rotational modes of energy receive more energy.

The shock front itself is so thin that it can always be considered frozen, and nonequilibrium conditions begin immediately downstream of the shock front.

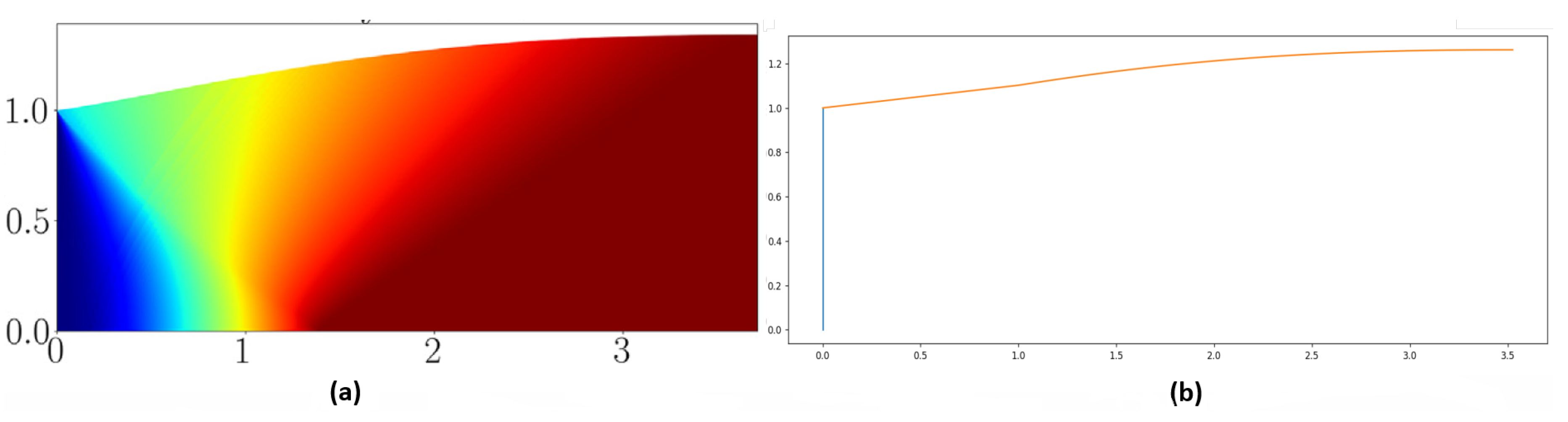

9.5.5. High Enthalpy Quasi-1D Flow

In a nozzle, where the flow is likely to be chemically reactive, a quasi-1D analysis can be applied using local equilibrium, as changes in pressure and temperature are quickly corrected by the flow. This analysis resembles that of a calorically perfect gas, but with an iterative method to calculate the equilibrium. Pressure and temperature across the nozzle are functions of stagnation conditions and local velocity magnitude.

Figure 14 shows that in the reservoir, high temperatures lead to molecular dissociation, with atoms recombining through the expansion, as temperature decreases. In the expansion, temperature decreases less then with calorically perfect gas, as molecular recombination gives away energy due to zero-point energy decreasing.

If nonequilibrium is being considered, the sonic line, from local equilibrium considerations, will be slightly curved and downstream of the geometric throat [

6].

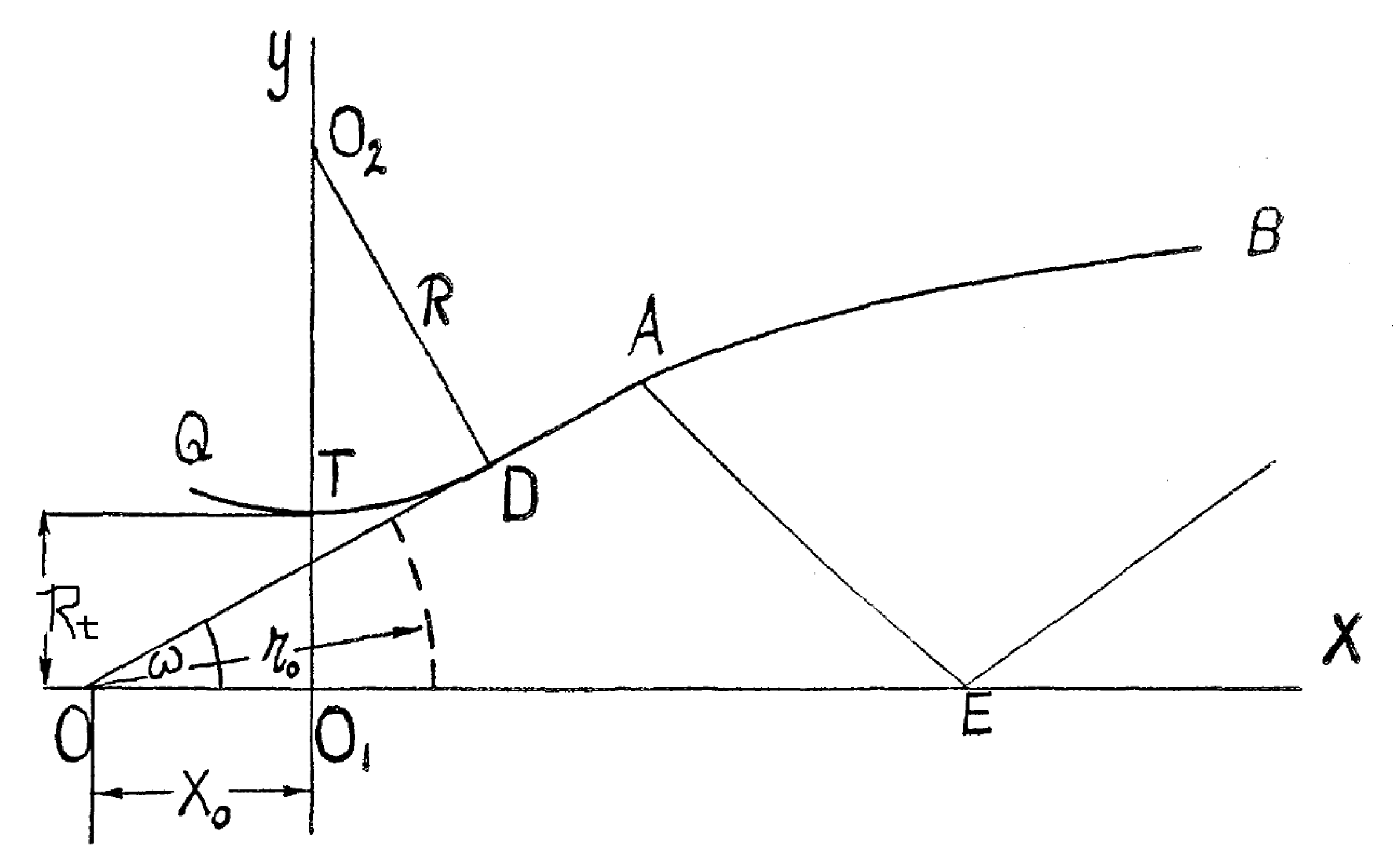

10. Transonic Solution

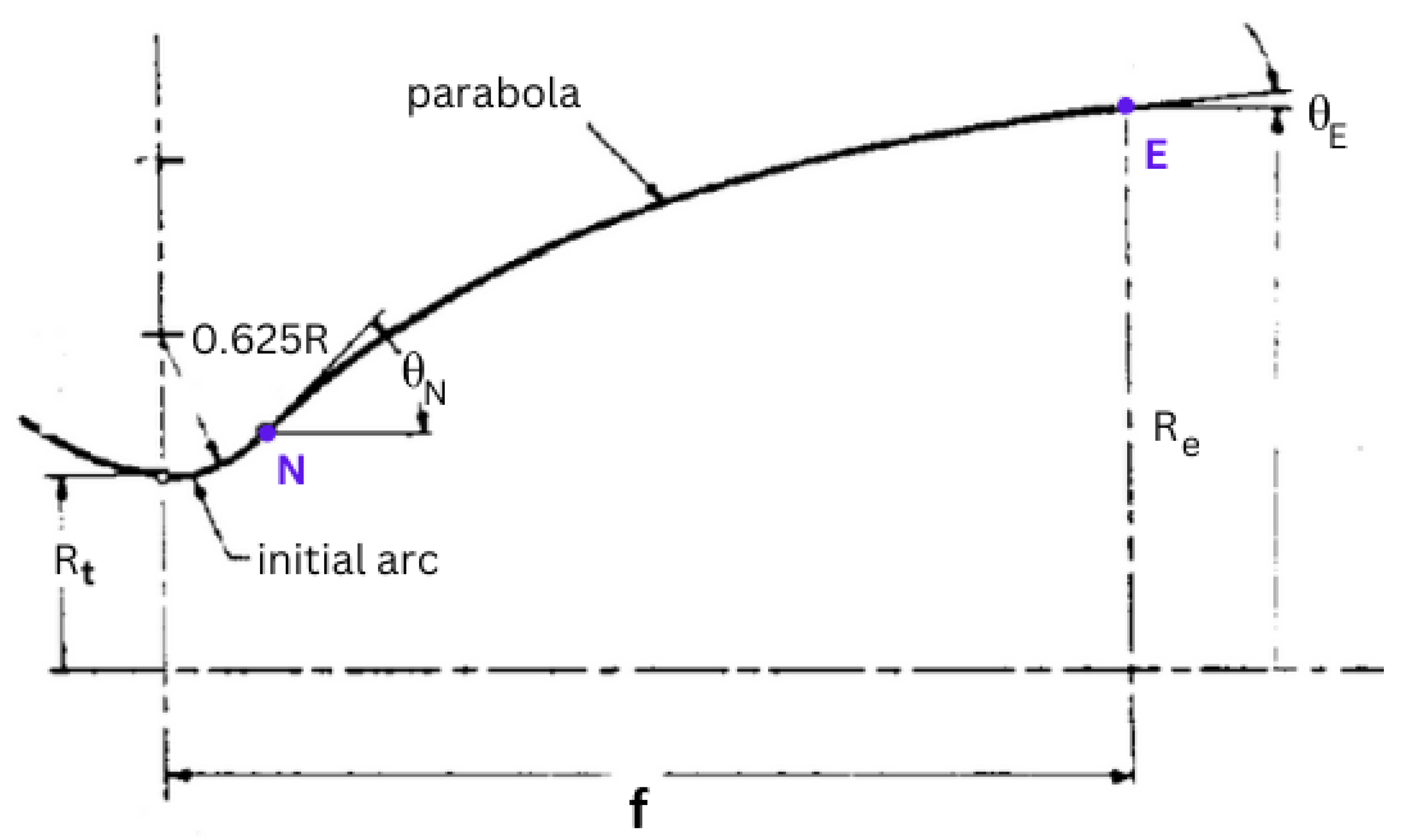

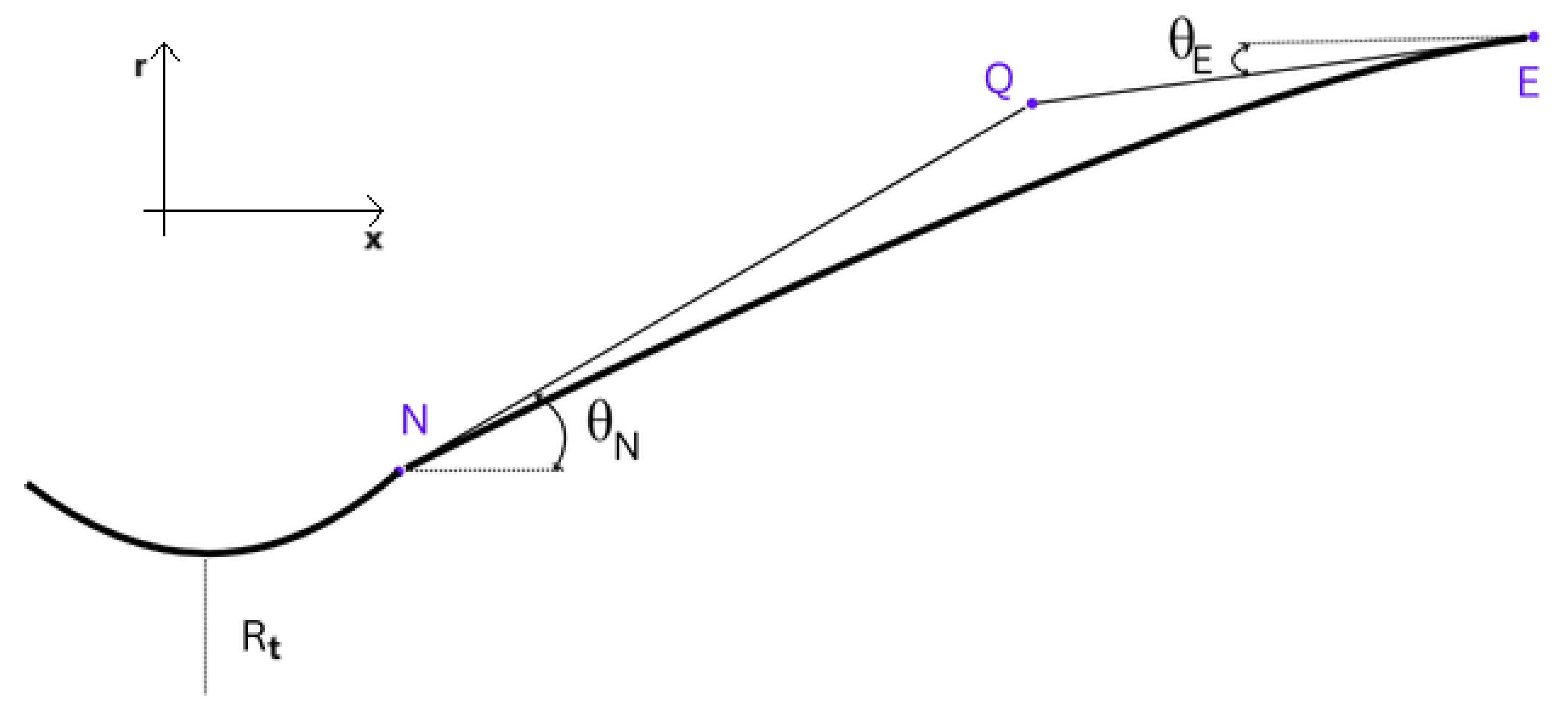

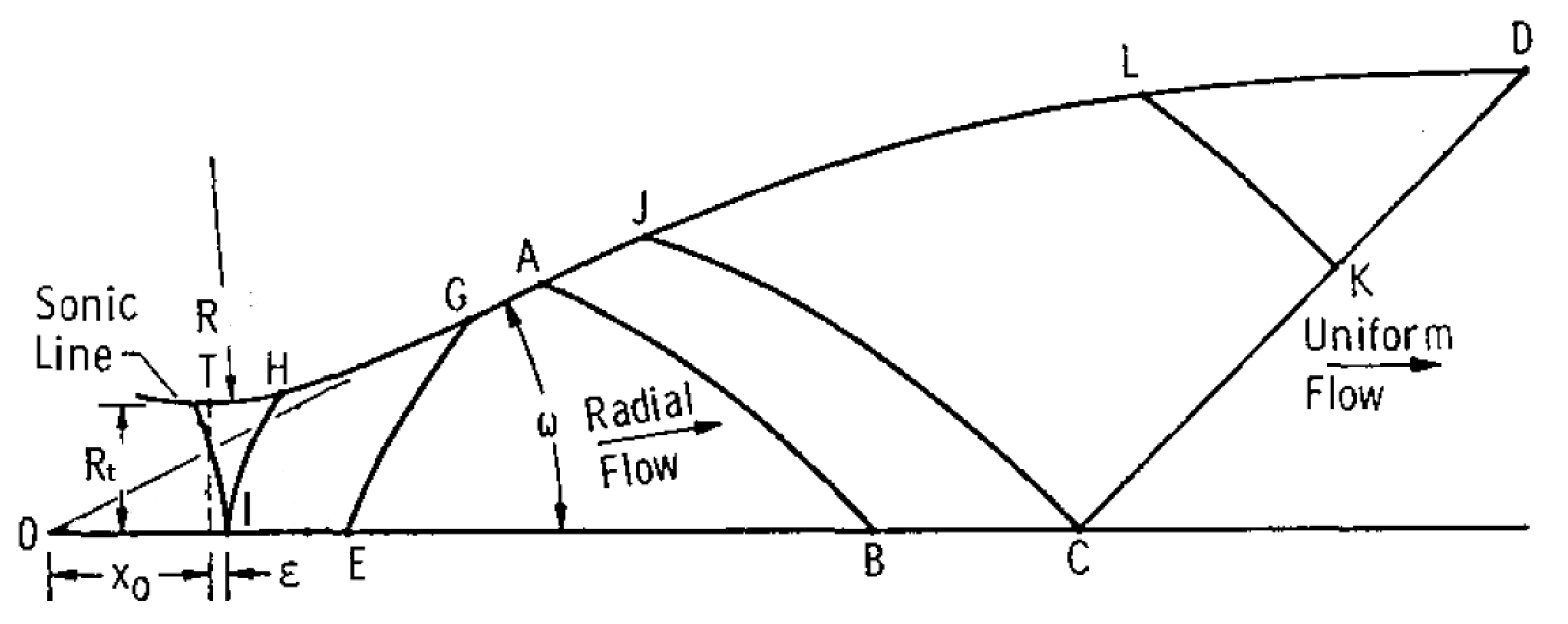

The throat region of a convergent-divergent nozzle must be carefully studied, as it is where the flow chokes, and most contour design methods derive crucial boundary conditions. Early on, it was discovered that the sonic line is not straight but actually slightly convex in the upstream direction, a consequence of the nature intrinsic to the local flow, which exhibits both subsonic and supersonic phenomena, characterized by pockets at different regimes. It became of utmost importance to develop a sufficiently accurate method to model the velocity vectors of the flow in the throat region.

Hall [

8] proposed the first method of a transonic solution near a de Laval nozzle, that is still applied by some contemporary literature. It consists of an expansion in order of

, where

is the radius of the contour immediately downstream of the geometric throat. By expanding the series of velocity to

, parabolic, hyperbolic, and circular arc throats are considered. This method can be implemented for other divergent shapes with some adaptations.

Hall’s method demonstrates considerable accuracy compared to experimental results for , and two-dimensional flow. The series expansion to yielded an error of just and when fully expanded to , the error further decreased to only .

For

, Hall’s solution starts to detriorate, and for values

, category of most of the current rocket nozzles, the method diverges in an oscillatory manner. Some inaccuracies can also be detected in the terms of the third degree parcel of the expansion for

and

. To address these problems, Kliegel [

9] presented a similar method, but the series are expansions of

. This upgraded method can even consider sharp corner corresponding to

.

Hall’s solution employs cylindrical coordinates, but Kliegel defends that toroidal coordinates must be used as that’s the only way to exactly solve the wall boundary condition. Kliegel’s method shows good correlation with experimental results for .

Nonetheless, Kliegel’s method still presents some errors. Specifically, in bringing the problem back to cylindrical coordinates from toroidal ones, it does not ensure that the equations of motion are respected in the cylindrical coordinates.

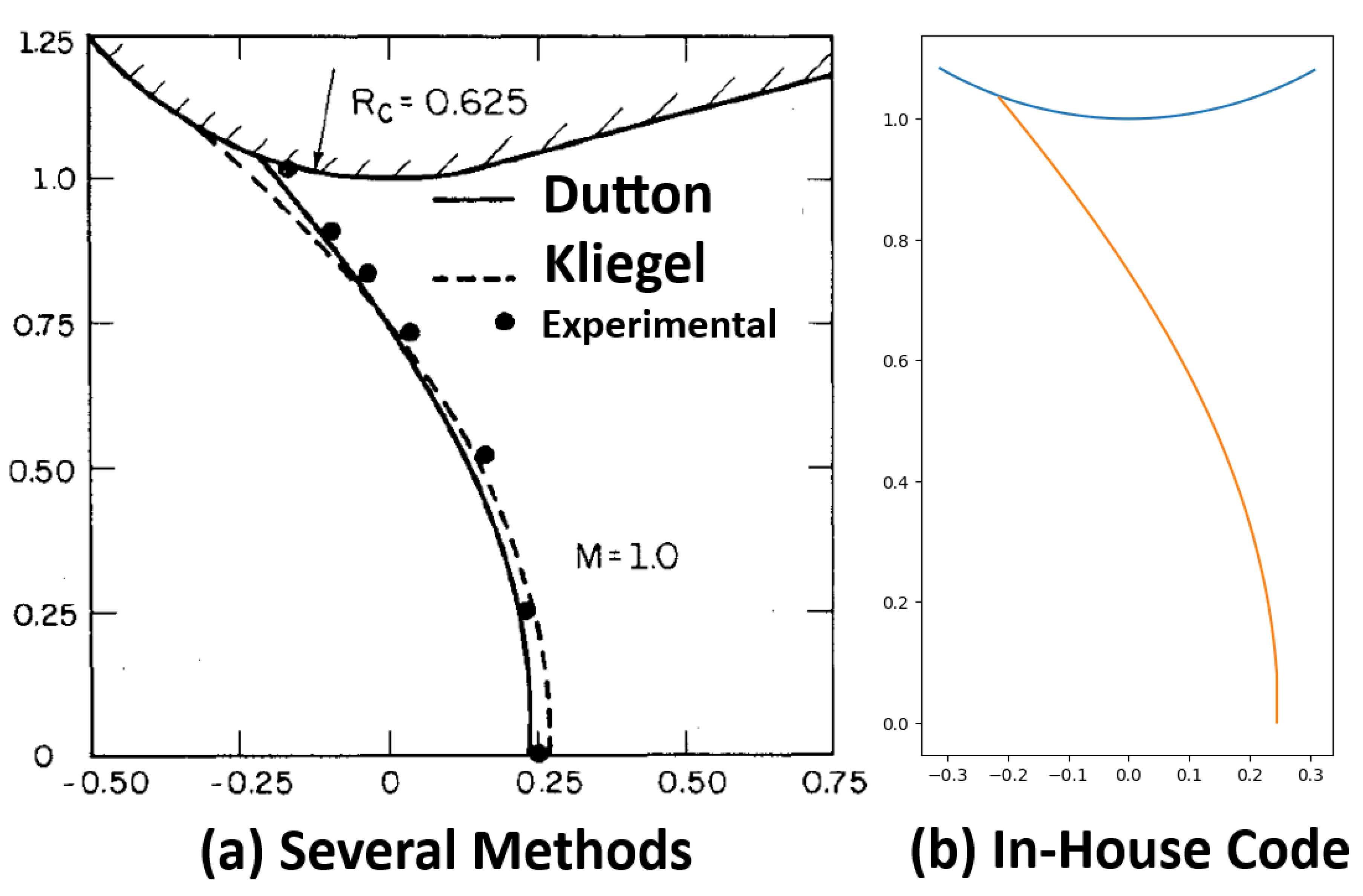

Dutton [

10] addresses this problem with a

expansion, where

is arbitrary. Dutton method respects the differential equations of motion for cylindrical coordinates when bringing the control volume back from toroidal. In fact, as seen in

Figure 15 a), Dutton’s method is the most accurate for

compared to experimental results.

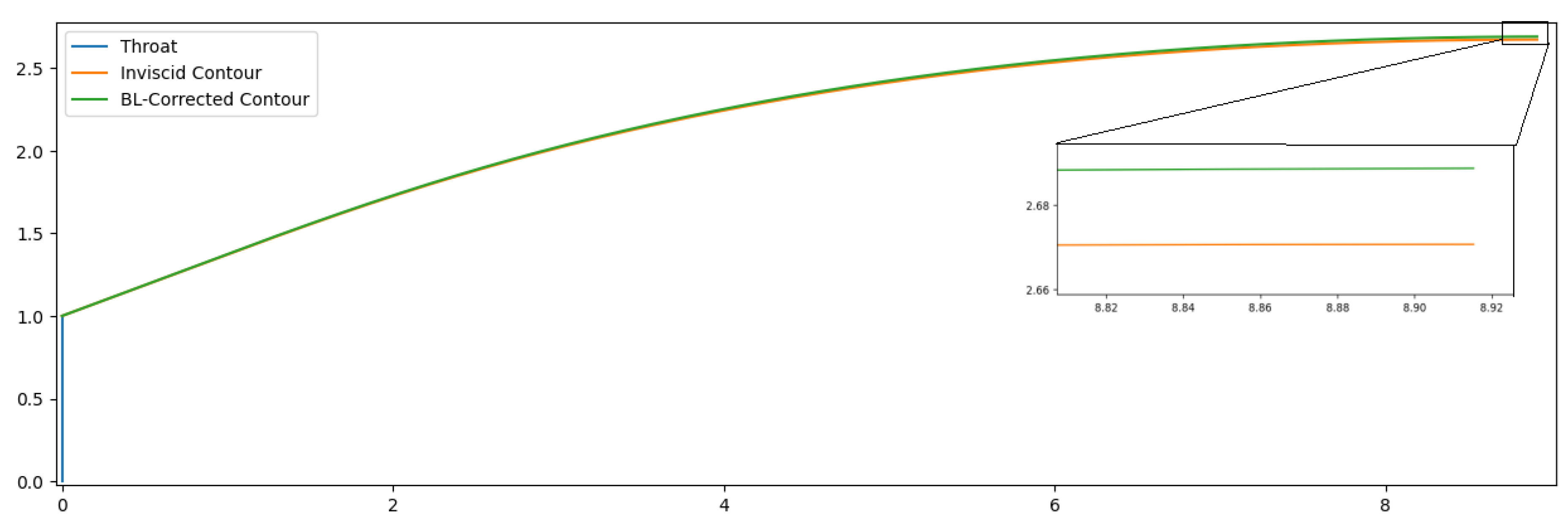

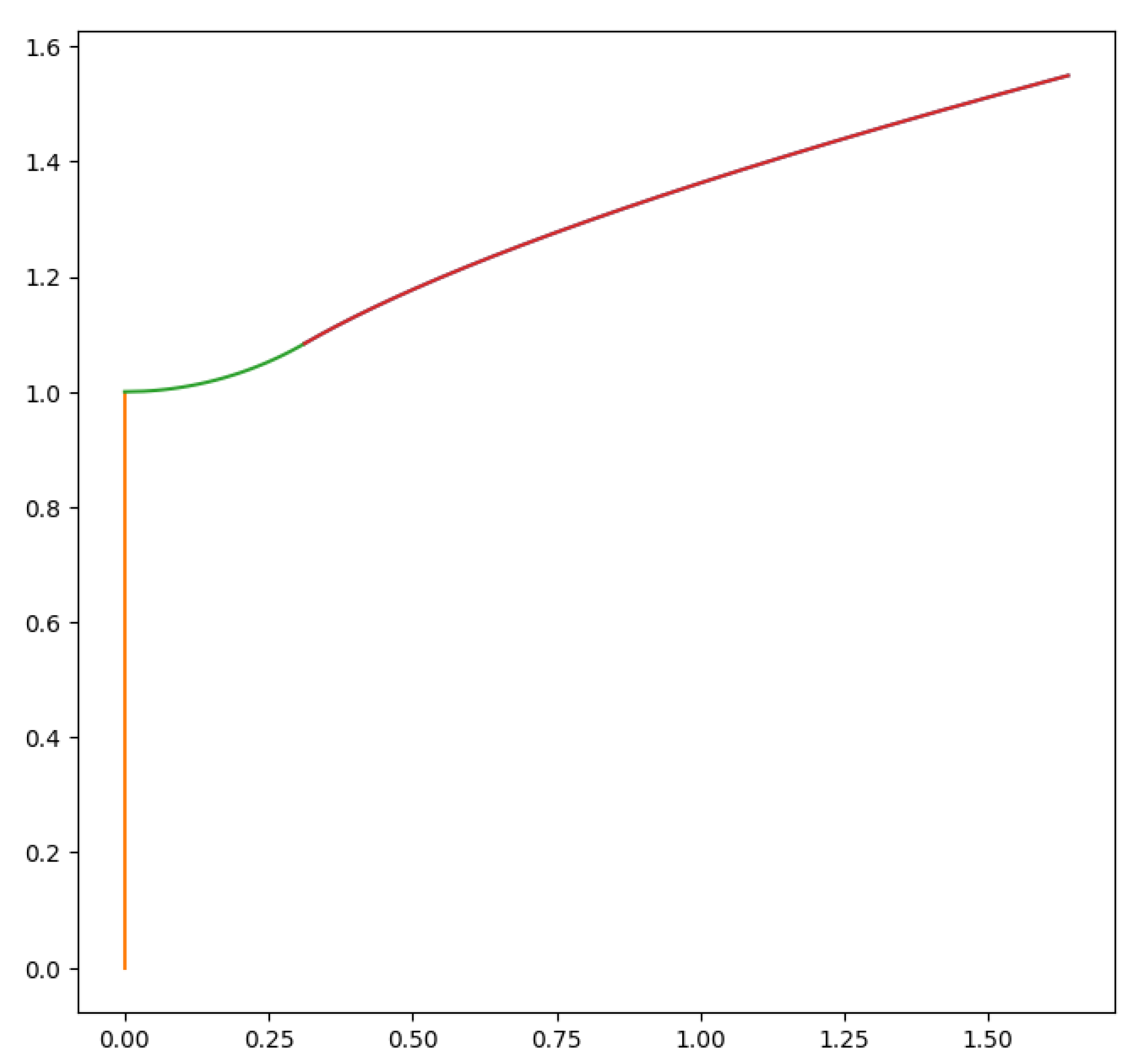

An algorithm with Dutton’s method was implemented, presented in

Appendix B with the respective Equations. Its sonic line for

was traced and can be seen in

Figure 15 b), where’s evident the in-house code provides a curve with similar shape and intercepts the axis and contour in the same points as Dutton’s graphic.

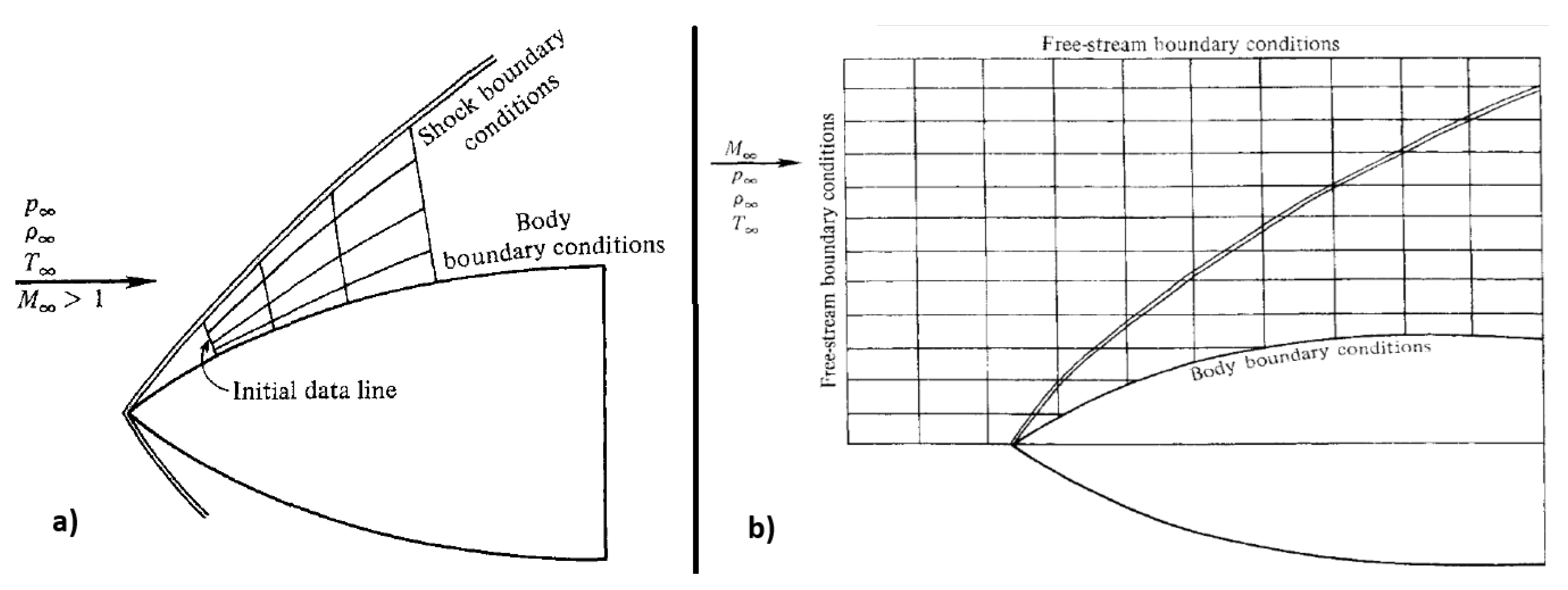

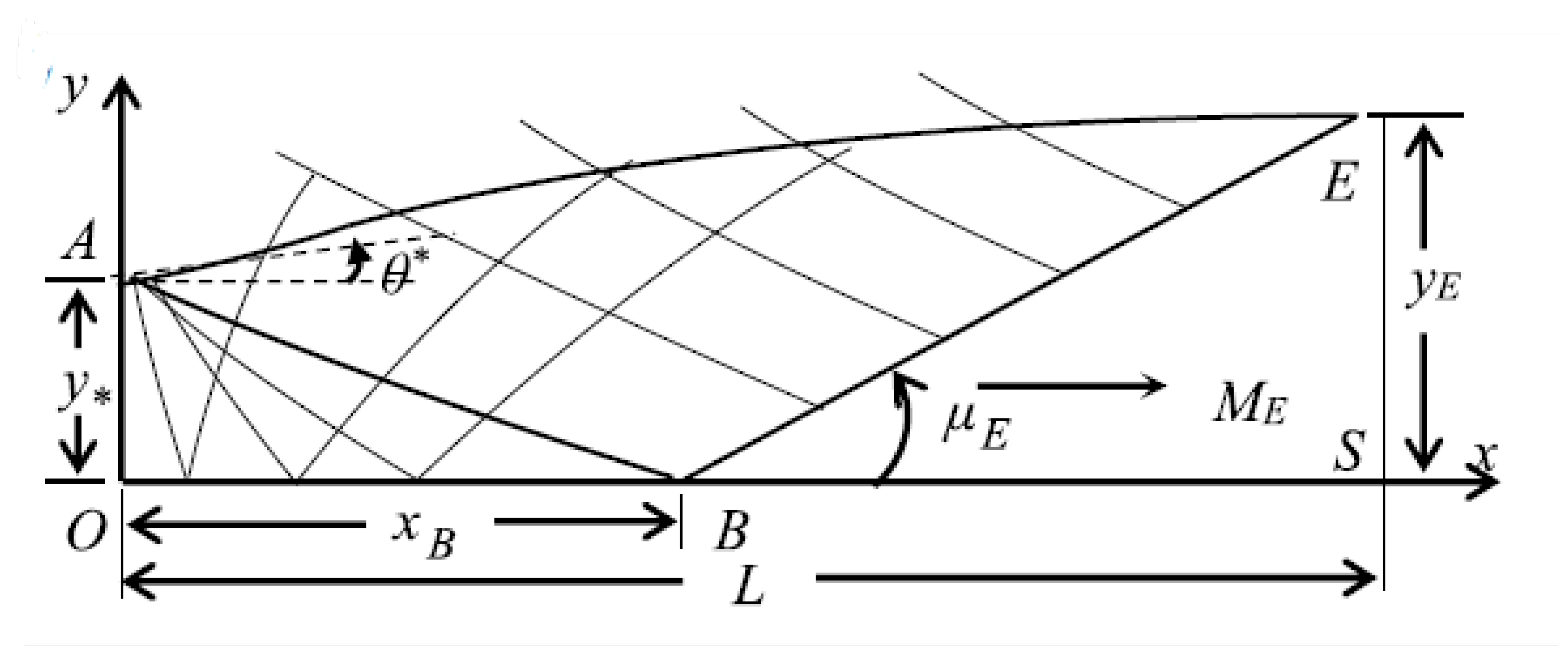

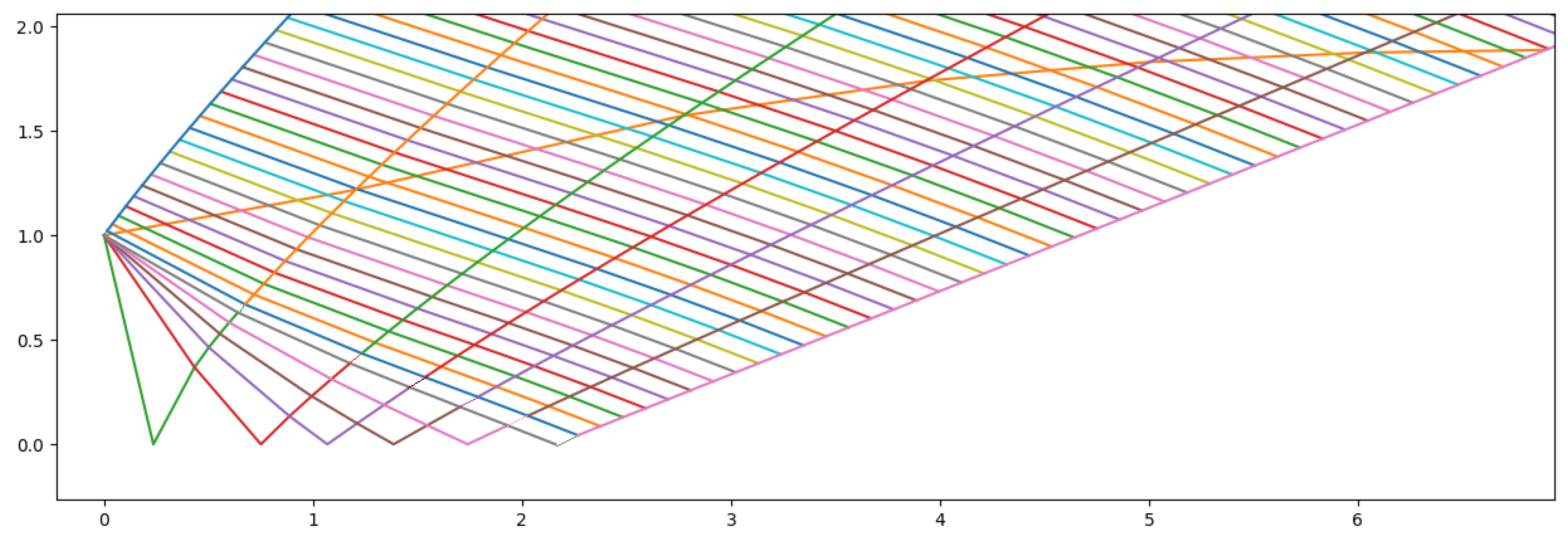

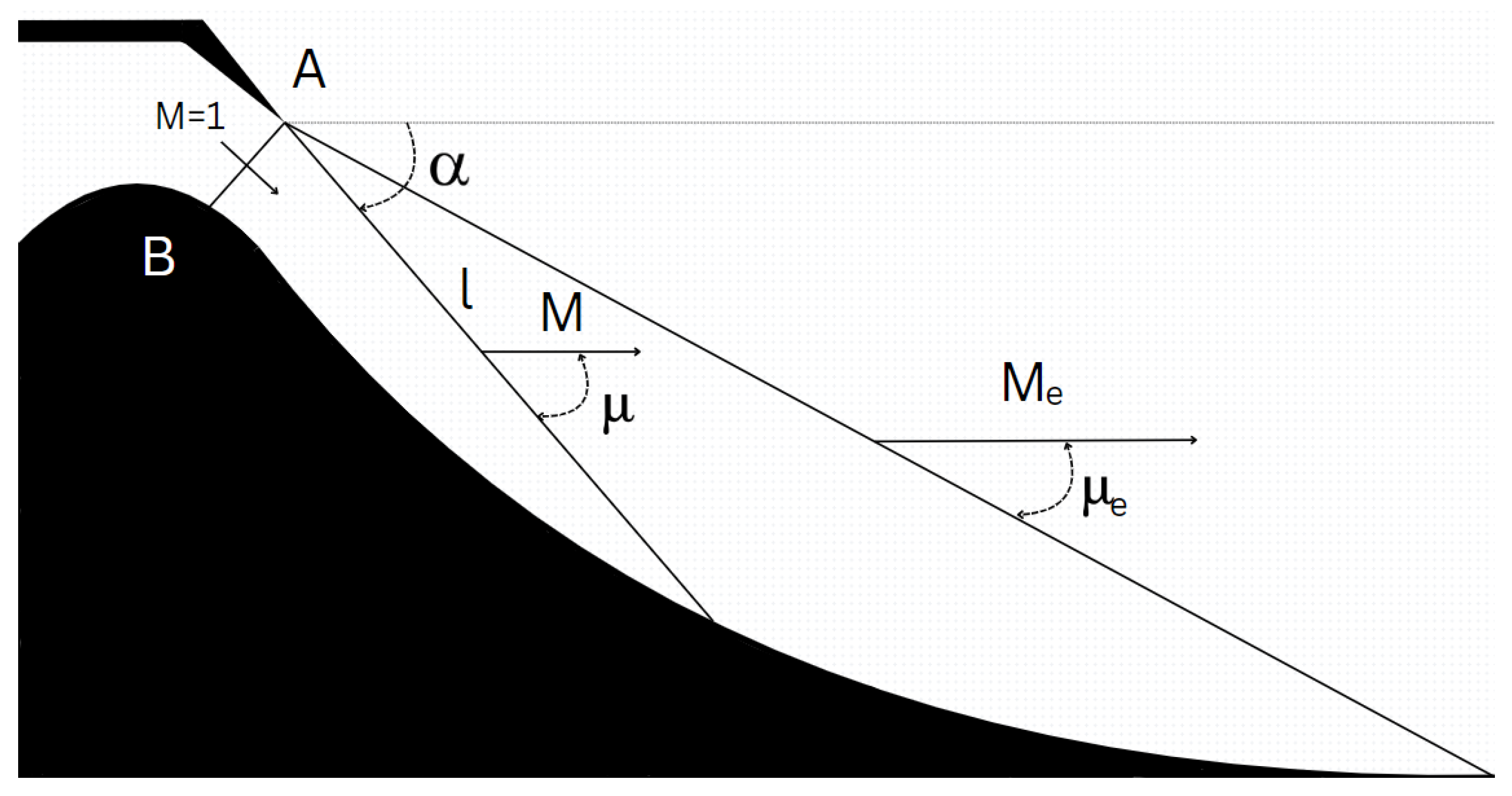

11. Method of Characteristics

The quasi-1D approach fails to consider the multidimensional of velocity and other flow properties, making it unfit to provide contour designs and analyses. Within a flow, the full-velocity potential equation takes the form of a partial differential equation (PDE). The Method of Characteristics (MOC) is a mathematical tool to solve PDEs by transforming them into ordinary differential equations (ODE).

To accomplish this, the MOC employs characteristic lines, inherent to the mathematical definition of a PDE, along which the PDE simplifies into an ODE. These lines maintain a mathematical link, facilitating the solving of the flow at different points, starting from known conditions, often derived from assumptions specific to a given nozzle design.

To apply the following description of the MOC, the flow must be assumed to be supersonic, steady, inviscid (with neglected boundary layer effects) and irrotational[

6].

The potential velocity in Equation

100 is obtained by combining the continuity equation and Euler’s equation for a two-dimensional, irrotational flow. This results in a nonlinear PDE that becomes a hyperbolic equation if Equation

101 is satisfied, a condition met in supersonic flow.

The direction lines defining the hyperbola are known as characteristics, and in the context of the velocity potential in supersonic flows, coincide with the Mach lines.

As a function of both

x and

y, the velocity potential’s derivatives are expressed by Equations

102 and

103.

By combining Equations

100,

102 and

103 in a system of linear algebraic equations with variables

,

and

, and solving for

, using Crammer’s, Equation

104 can be obtained.

At a given point in the flow, implies that along a direction , the velocity undergoes changes corresponding to the respective and components, except for a specific direction, where the denominator equals zero. Along this direction, the derivative lacks a specific finite value, posing an inconsistency. Therefore, for this scenario to be indeterminate, the numerator must also be zero.

From this mathematical definition, despite the flow’s properties being continuous in the absence of shocks, the first derivative must be indeterminate along a characteristic line. This condition allows for the crossing of several streamlines.

Setting the denominator of Equation

104 to zero, results in Equation

105. The slope of the characteristic lines that pass through a given point can then be obtained using Equation

106, simplified into Equation

107 [

11].

Considering Equation

107, it becomes evident that, in supersonic flow, any given point is intersected by two characteristic lines. In the case of sonic flow, a single characteristic line exists, and its slope equals the Mach angle. For subsonic flow, the Mach angle becomes imaginary, signifying that the characteristic lines take an elliptical form [

6].

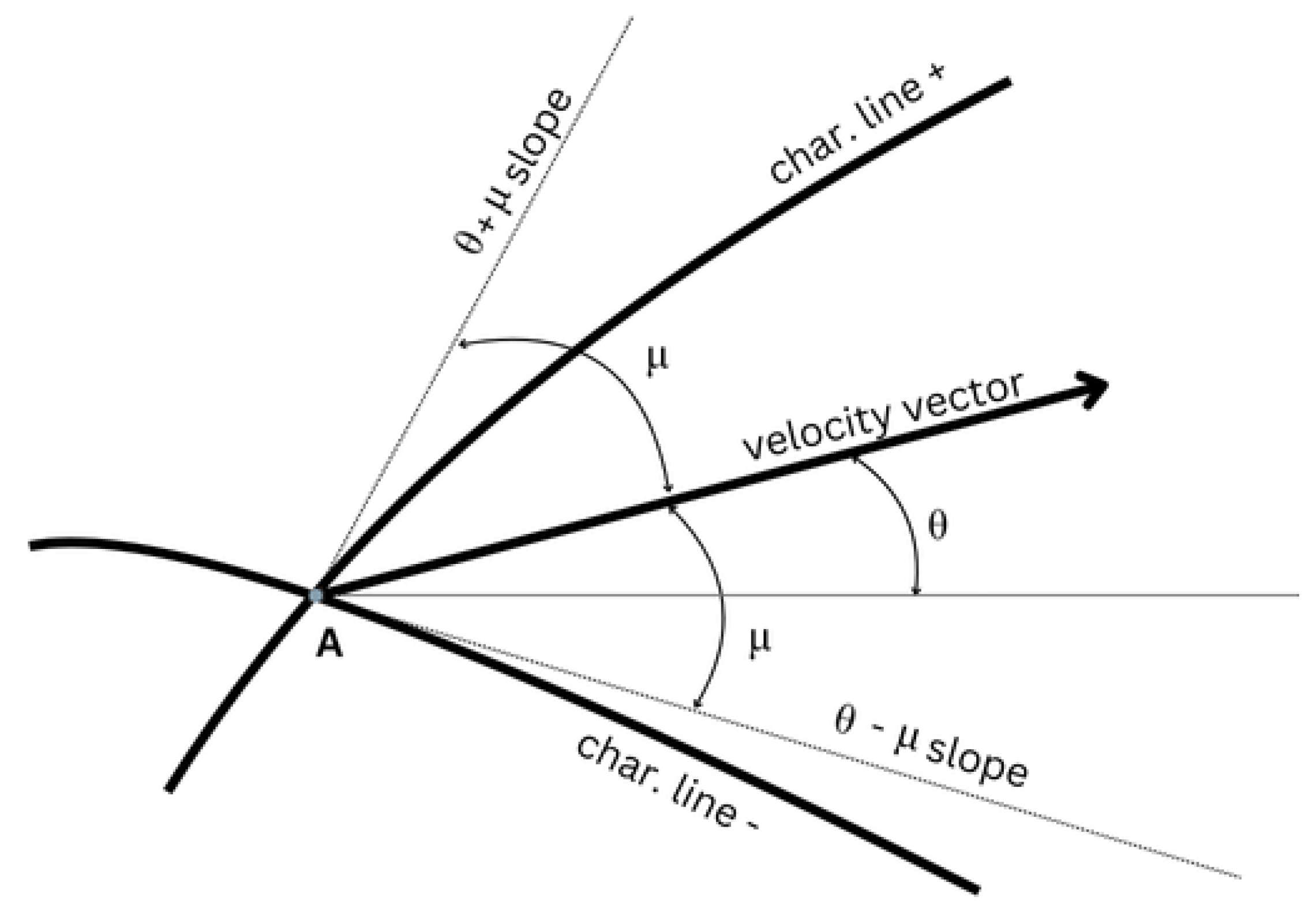

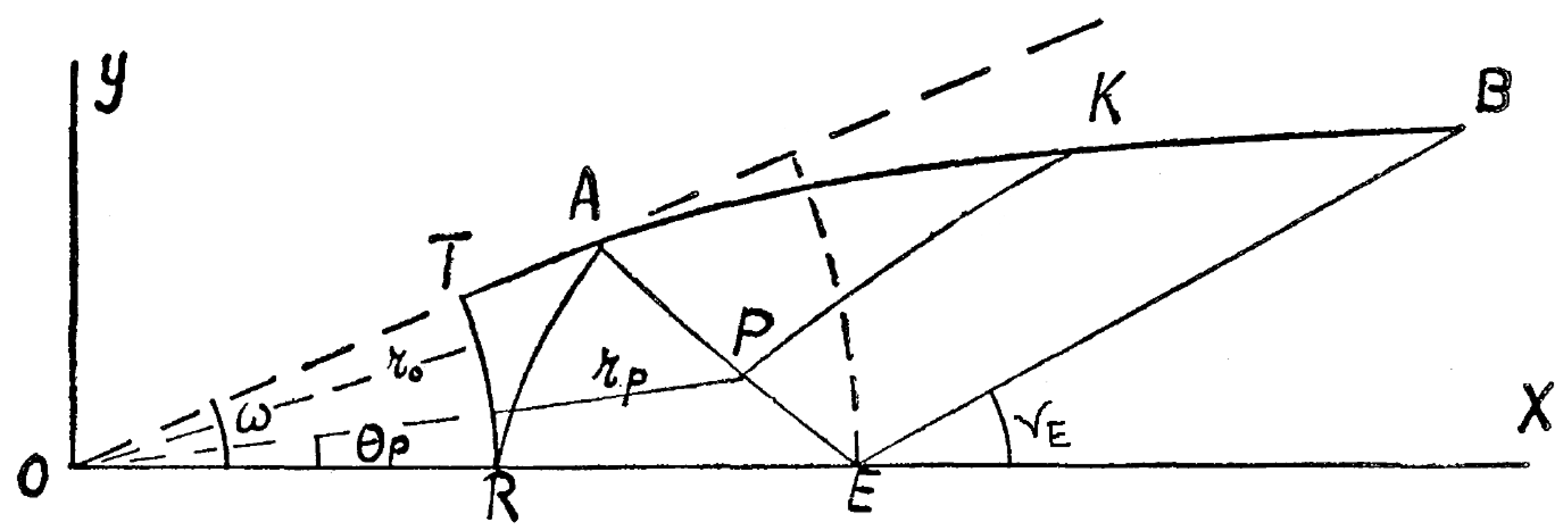

Examining

Figure 16, two characteristics are observed passing through a designated point A: a left characteristic

with a slope of

and a right characteristic

with a slope of

To solve the flow along a characteristic line, the governing PDE describing the flow reduces to ODEs, also known as compatibility equations. These equations are obtained by setting the determinant of the numerator in Equation

104 to zero, resulting in Equation

108.

Equation

109 represents the set of ODEs obtained from Equation

108. With algebraic manipulation it leads to the expressions illustrated in Equations

110 and

111 for a planar flow.

In cases where the flow is unknown but the characteristic constants have been established at the nodes, Equations

112 and

113 can be employed to determine the flow axial deviation and Prandtl-Meyer angle, respectively [

11].

Rocket nozzles commonly exhibit axisymmetric behavior, making cylindrical coordinates a more appropriate choice for describing the flow. The prior description of the MOC can be modified, with the key distinction lying in the compatibility equations denoted in Equations

114 and

115. In the axisymmetric MOC, the assumption of a constant relation along a given characteristic line no longer holds. Consequently, the relation between the variables

and

requires integration, which can be achieved by employing the finite differences method described in

Appendix C accordingly to Zebbiche [

12] and Restrepo [

13].

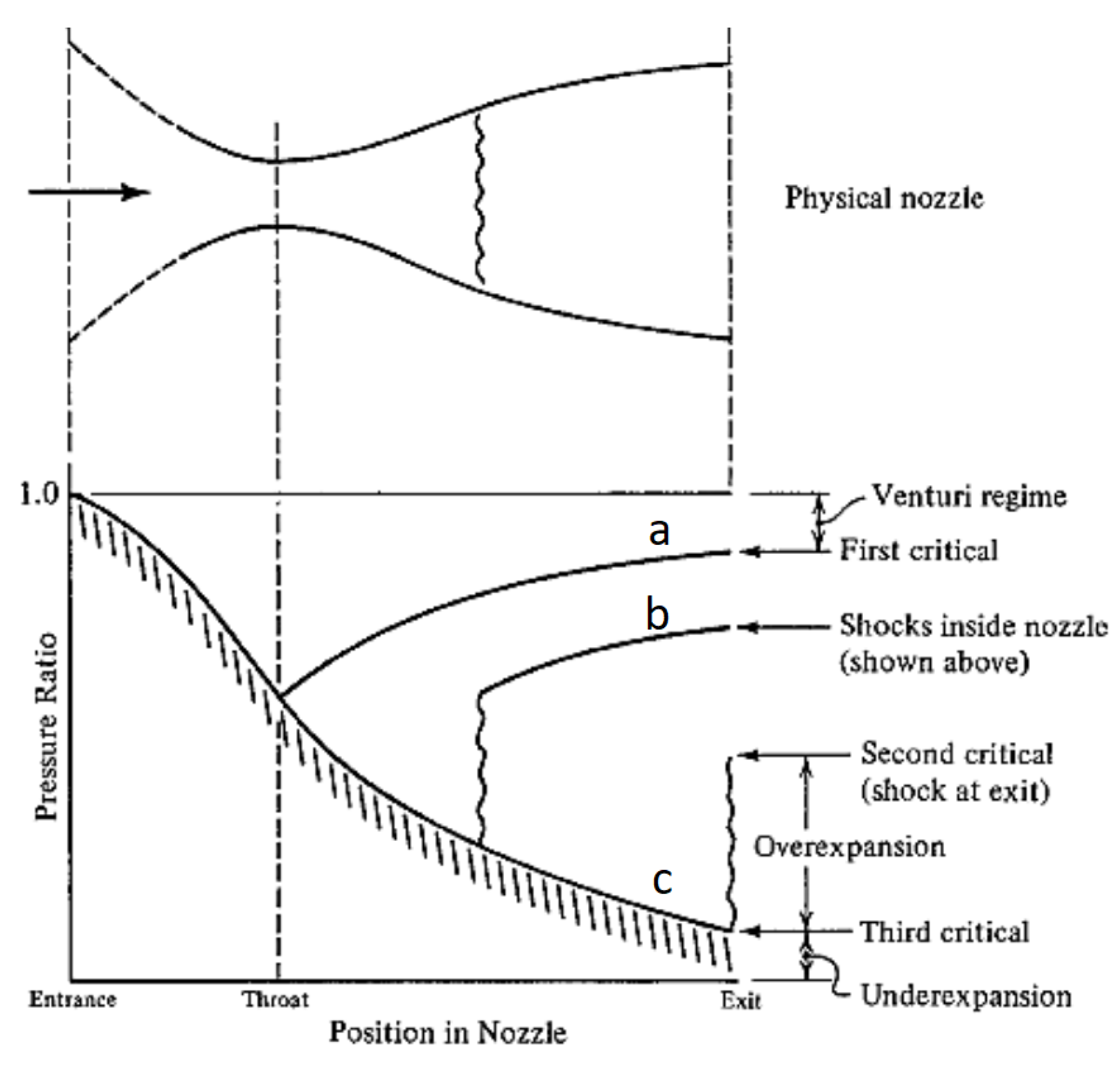

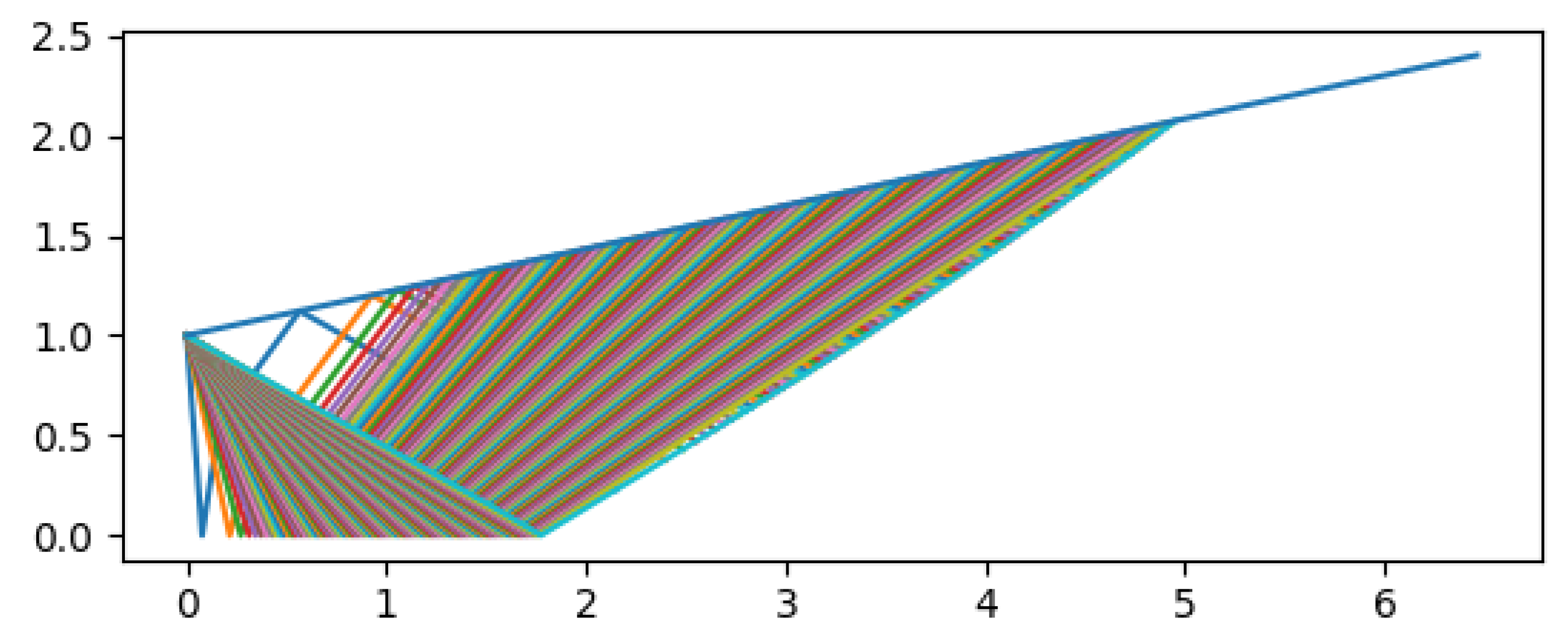

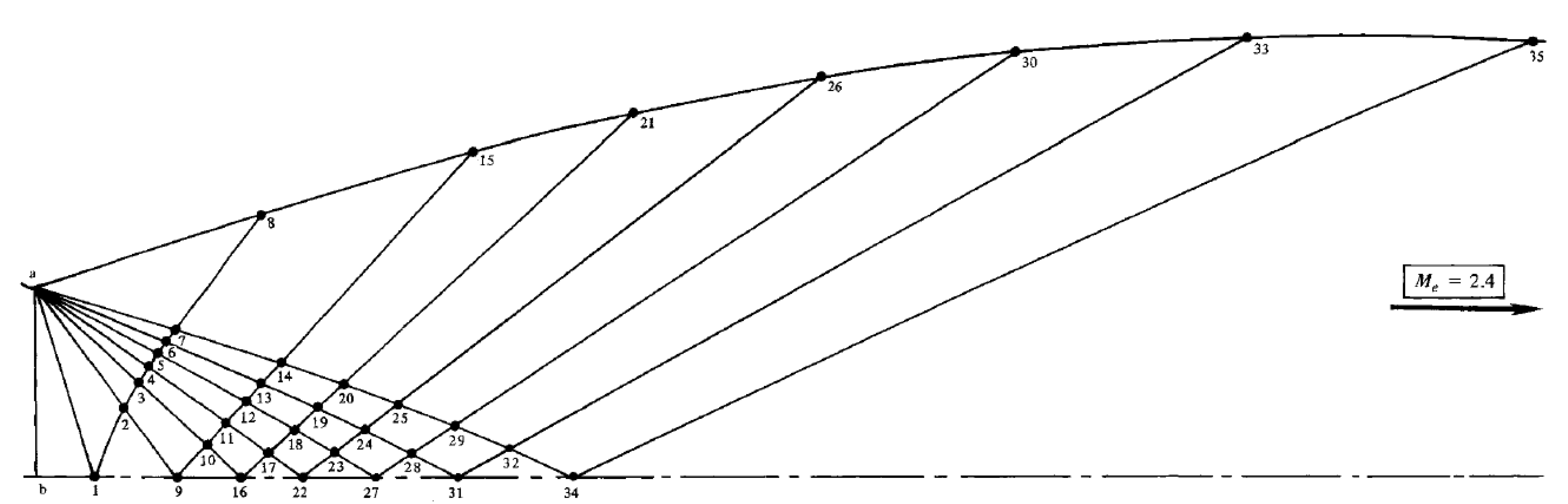

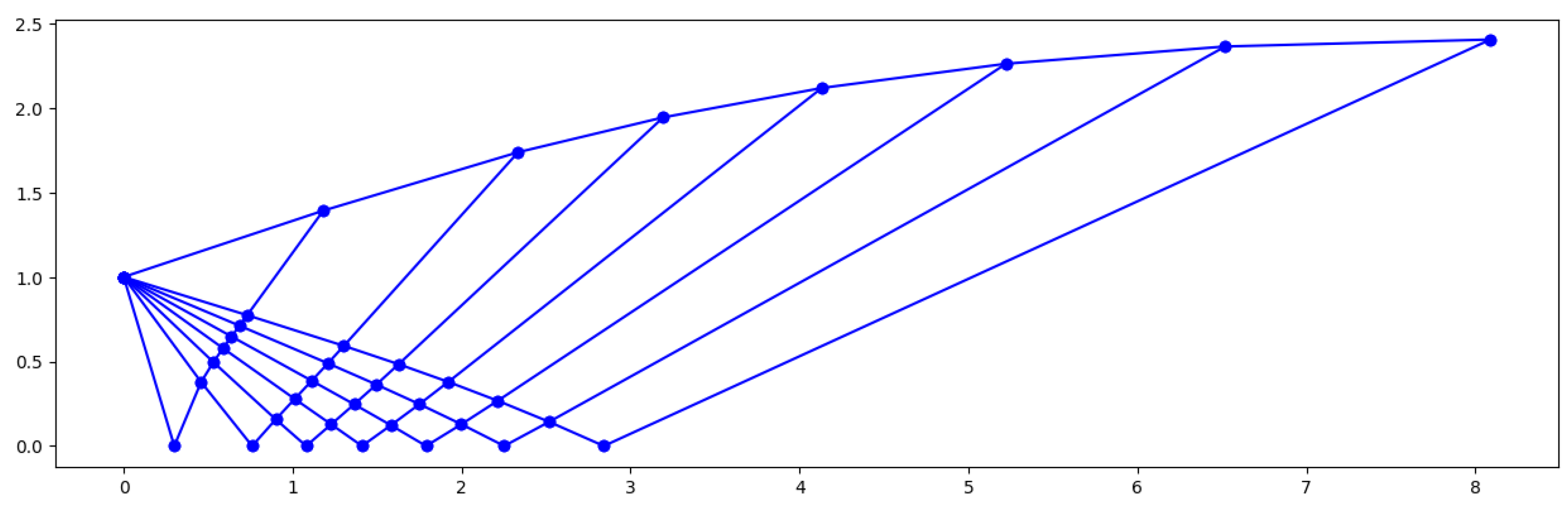

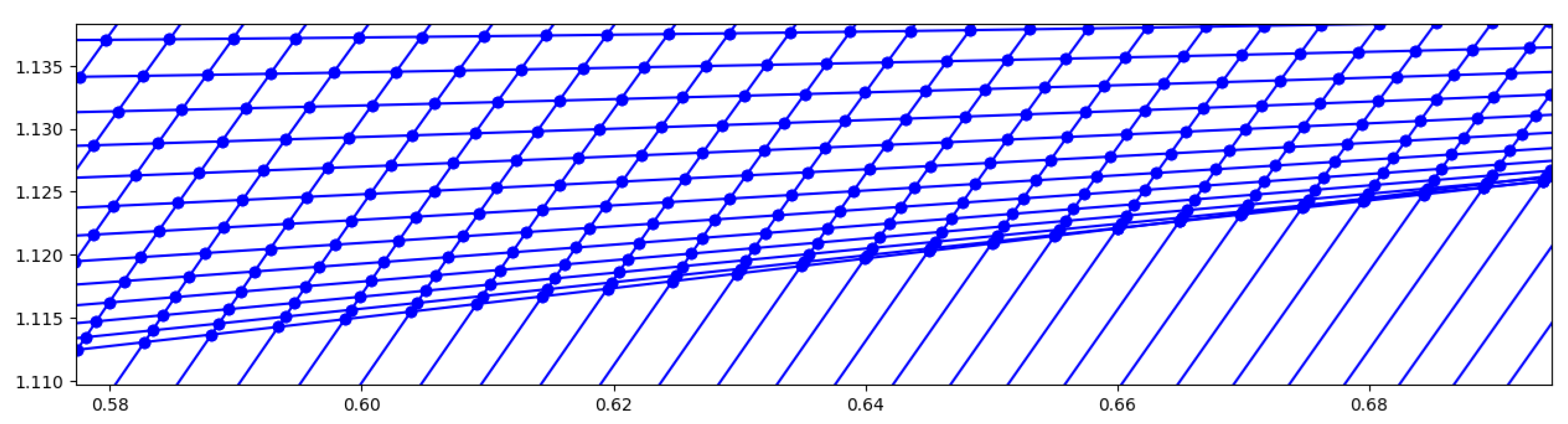

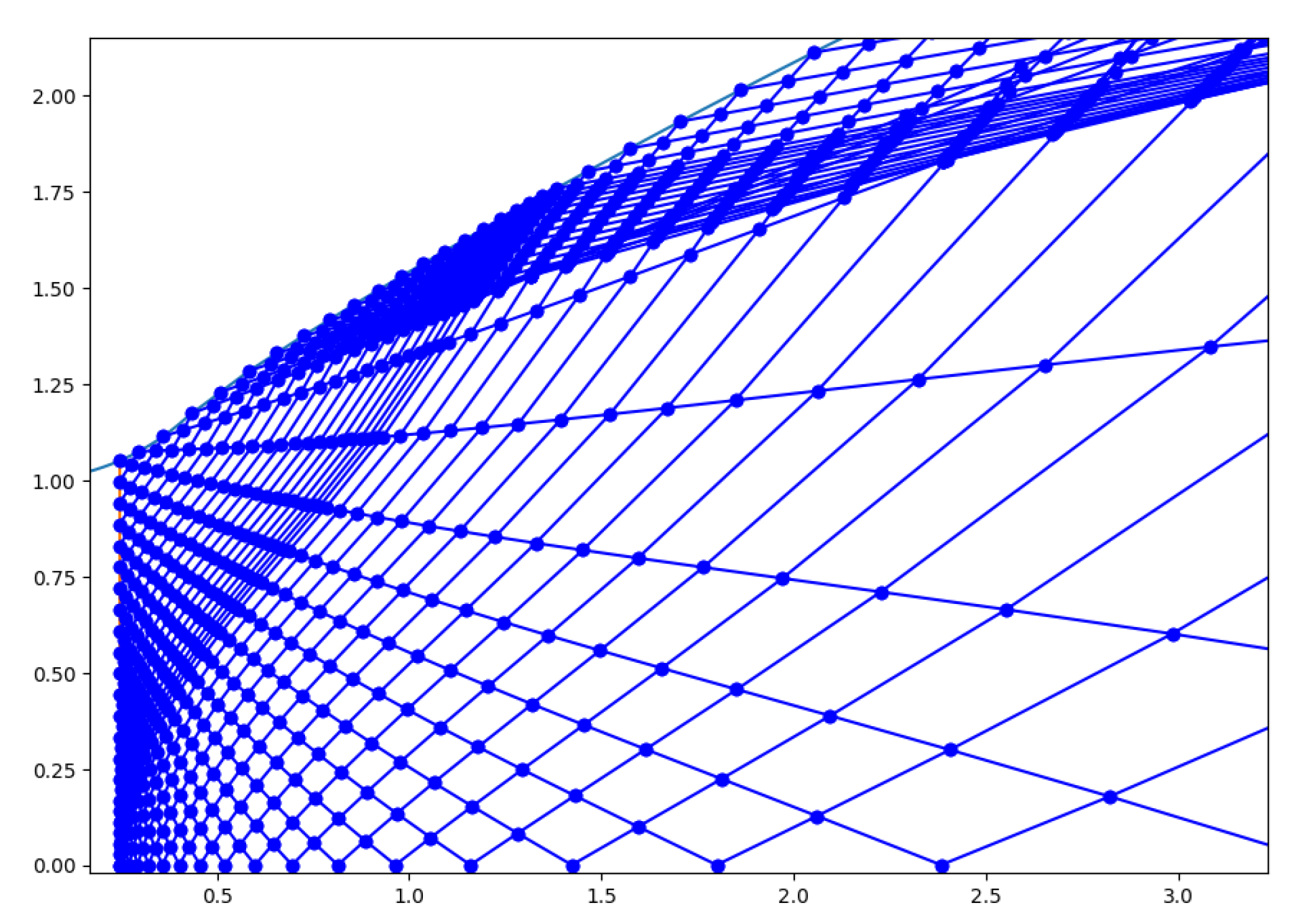

For a planar context, initiating from established boundary conditions, characteristic lines radiate to form a grid. The MOC is initially employed to solve the flow at each node. Subsequently, the slopes obtained are utilized to construct the grid, imparting geometric dimensions to the nodes, solving the flow. To note that, when approximating a characteristic line between two nodes i and i+1, to a straight line, the sloop should be an average as depicted in Equation

116. For an axisymmetric case, both the nodes and their coordinates are solved at once and one node at the time as there’s no longer a constant through a characteristic line.

If the MOC is employed to draw the contour of a nozzle, there are two main philosophies: either drawing a line that follows the orientation of the flow at each point or setting mass conservation to draw a specific streamline. The origin of the grid depends on the particular nozzle design and associated assumptions.

A great programming language to employed MOC algorithms is Python, as it is one of the most widely used in aerospace engineering, including by NASA, especially in non-safety critical systems [

14]. It is characterized as a high-level programming language that emphasizes readability and encourages the creation of open-source libraries. Additionally, Python is free to use and does not require a compilation step, which accelerates the edit-test-debug cycle and prevents segmentation faults from incorrect user usage through the use of exceptions.

12. CFD - Computational Fluids Dynamics

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) is a branch of fluid mechanics, including any numerical method that can analyze and solve problems that involve flows. By discretizing the fluid domain into a grid and solving governing equations using numerical methods, CFD enables the visualization and understanding of complex fluid behaviors.

This powerful tool is extensively used in engineering and physics, allowing for the prediction of aerodynamics, heat transfer, and other fluid-related phenomena. CFD simulations play a vital role in optimizing designs, evaluating performance, and reducing the reliance on costly physical prototypes in various industries.

Although the MOC can be considered part of CFD, this section of the book aims to provide a broader understanding of CFD, incorporating simplifications typical of supersonic flows.

Reference [

6] serves as the basis for this Section, except the last Subsection.

12.1. Differential Conservation Equations for lnviscid Flows

Traditional, fluid analysis, and consequently conservation equations, are set for a control volume

delimited by surface area

S. So, for any vector function

A and scalar function

Equations

117 and

118 are true for any control volume, respectively.

12.1.1. Continuity

Equation

119 represents the continuity equation for a given control volume. From Equation

117 with

, Equation

120 is obtained.

For Equation

120 to be null, the first parcel of the integral could be annulled by the second. This is impractical, as the analysis must be true for any random control volume, so the only chance for it to be zero is if the control volume is a single point, being precisely the goal in CFD. So Equation

121 is obtained, representing the

differential equation of continuity.

12.1.2. Momentum

Equation

122 represents the momentum conservation for a given control volume. If combined with Equation

118 with

, Equation

123 is obtained. Equation

124 represents its scalar decomposition in the x direction.

If Equation

117 assumes

, Equation

125 is obtained. Further consideration of Equation

124 leads to a single integral equal to zero, as depicted in Equation

126.

Solving Equation

126 with the same philosophy of the continuity, Equations

127 ,

128,

129 represent

differential equations of momentum conservation for each Cartesian direction.

12.1.3. Energy

Equation

130 represents the energy equation for a given control volume. Combined with Equation

117 and setting

and

, Equation

131 is reached.

Solving Equation

131 with the previous philosophy, Equation

132 is set and represents the

differential equations of energy conservation.

12.2. Introduction to Finite Differences

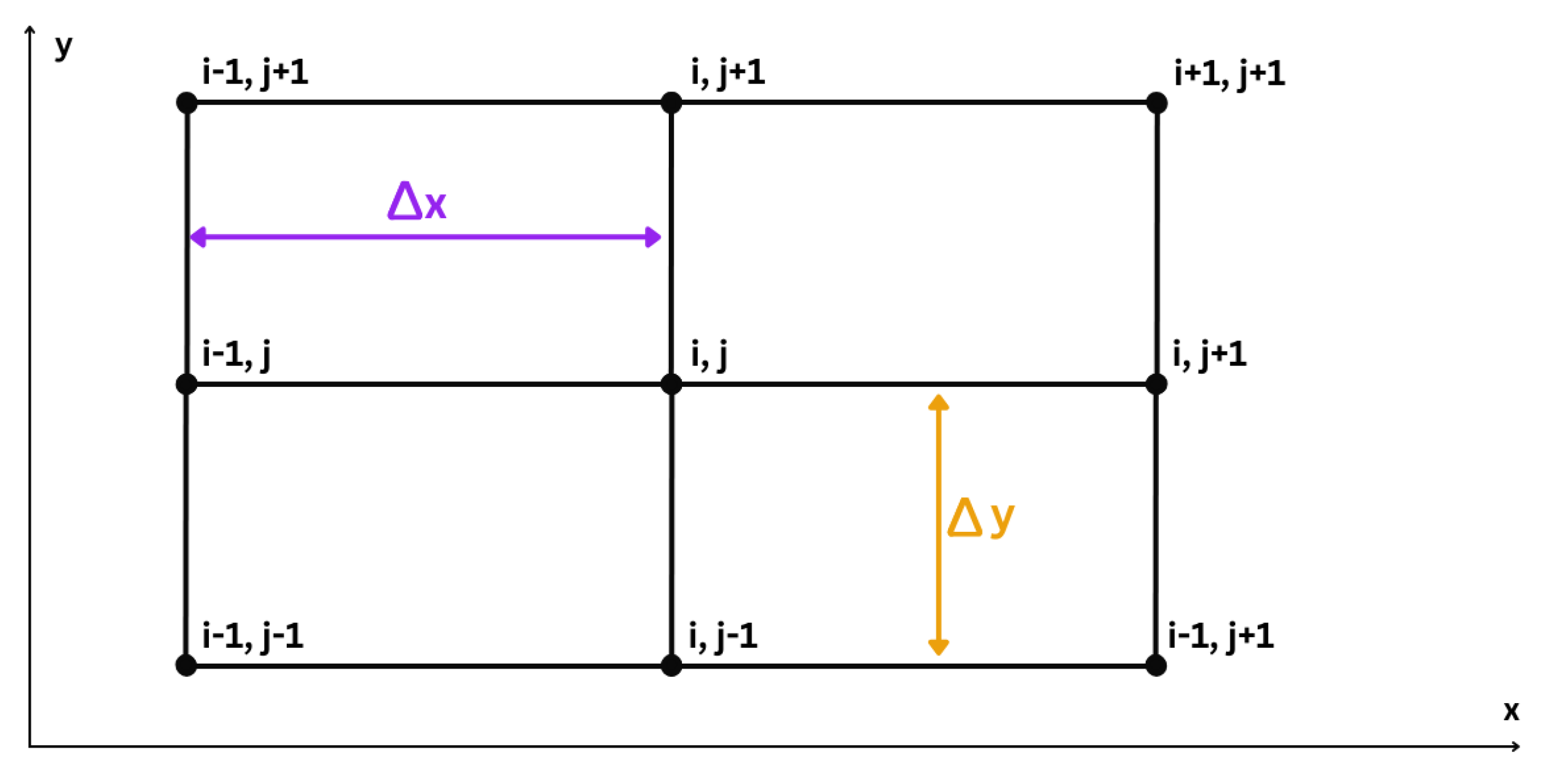

In finite differences methods, flow’s properties are known and calculated in discrete nodes. This unit process can be better understood by looking at

Figure 17. This method of solving the flow can be advantageous compared to the MOC, as sometimes characteristic lines can distort and following them is no longer possible, besides the impossibility of ensuring an uniform grid.

At each node, properties need to allow the expansion of modeling equations in the form of a Taylor’s series, as in Equation

133 for velocity

along the abscissa axis. Homologous equations are derivated for other properties and Cartesian directions.

12.2.1. Types of Differences

When building a CFD model, the way is found must be choose in accordance to the problem that’s being solved.

The

forward difference gives the derivative as the linear gradient between the node and the immediate next downstream node as per Equation

134.

The

rearward difference gives the derivative as the linear gradient between the node and the immediate prior upstream node as per Equation

135. For this case, the Taylor’s expansion is given by Equation

136.

The

central difference gives the derivative as the linear gradient between the prior upstream node and the immediate next downstream node as per Equation

137.

This way, the partial derivatives in the flow’s ruling equations can be replaced by algebraic differences.

12.2.2. Order of Accuracy

The truncation of the Taylor’s series introduces some errors, that will increment with the increasing of the partitions and/or . The more terms that are used, the more accurate the solution will be, but also lot more of computational power will be required. Factors like convergence behavior and stability must also be considered.

Usually

first-order accuracy is employed with the Taylor serie’s given by Equation

138.

If a more accurate solution is desired,

second-order accuracy can be employed as suggested in Equations

133 or

136. For viscous flows, second-order derivatives are present in the momentum and energy equations.

The following discussion will focus on first-order accuracy for inviscid supersonic flow.

12.2.3. Difference Equations

When the partial differentials in the flow’s equations are replaced with the differences presented before, difference flow’s equations are obtained.

For example, Equation

121 for steady 2D flow becomes Equation

139. Letting

and

and applying a forward difference in x and a central difference in y, Equation

140 is obtained, representing the

difference equation.

The governing equations can be expressed in a generic form for 3D steady flow, as shown in Equation

141. In this equation, each vector is defined, with the first term reflecting the continuity equation, the last term representing the energy equation, and the middle three terms each corresponding to a Cartesian projection of the momentum equation.

12.2.4. Explicit v.s. Implicit Methods

Considering the grid of

Figure 17, with the values of the vertical line i known. The downstream line i+1 values can be directly calculated from the values of line i.

This illustrates an explicit solver, where downstream nodes are calculated solely based on upstream information. Its the easiest to implement but the values of and must be carefully chosen so the solution is stable. It leads to more dense grids with higher computational cost.

Another algorithm may consider the variation of F as the average of the value of G of the upstream line i of known values and the unknown downstream line i+1, as suggested by Equation

146.

This way, a system of equations is built, so the solution does not only depend on upstream known flow but also on the downstream line that’s being calculated. It must be applied to several points at the same time so enough equations are available to build a proper solving matrix.

This implicit method has the advantage of permitting a more stable solutions for more scarce grids, allowing for faster advancement of the algorithm, with less computational costs, although the solving matrix takes some of the computational gains. Nonetheless, this type of method is harder to implement.

12.3. MacCormack’s Technique

There are several finite differences schemes with the present Subsection focusing on the one proposed by Robert MacCormack at the NASA Ames Research Center, that was very popular in the 70’s and 80’s. Although it currently has been surpassed by modern schemes, it is considered student friendly and is worth exploring to have a concrete idea of what this kind of algorithms do.

MacCormack’s method is applied to supersonic inviscid steady flow that has hyperbolic equations. It has two steps giving it a second-order accuracy although Taylor series are truncated at the first degree.

Starting by considering Equation

141 for 2D flow with no source in the fashion of Equation

147, the partial derivative can be given as an average between the known upstream line i and the unknown downstream line i+1 as suggested in Equation

148

Firstly, a

predictor step applies a forward difference to calculate the predicted

value as in Equation

149 for all the points in the upstream line i.

Then, in a

corrector step , and after

is used to calculate

, a reward difference is used in Equation

150 to find the average partial differential that is then calculated in Equation

151

Homologous thinking can be applied to solve the flow in another Cartesian directions.

There are still some applications of the MacCormack’s technique in contemporary literature like Li [

15] that proved a good correlation with experimental results, inclining in modeling an oblique shock.

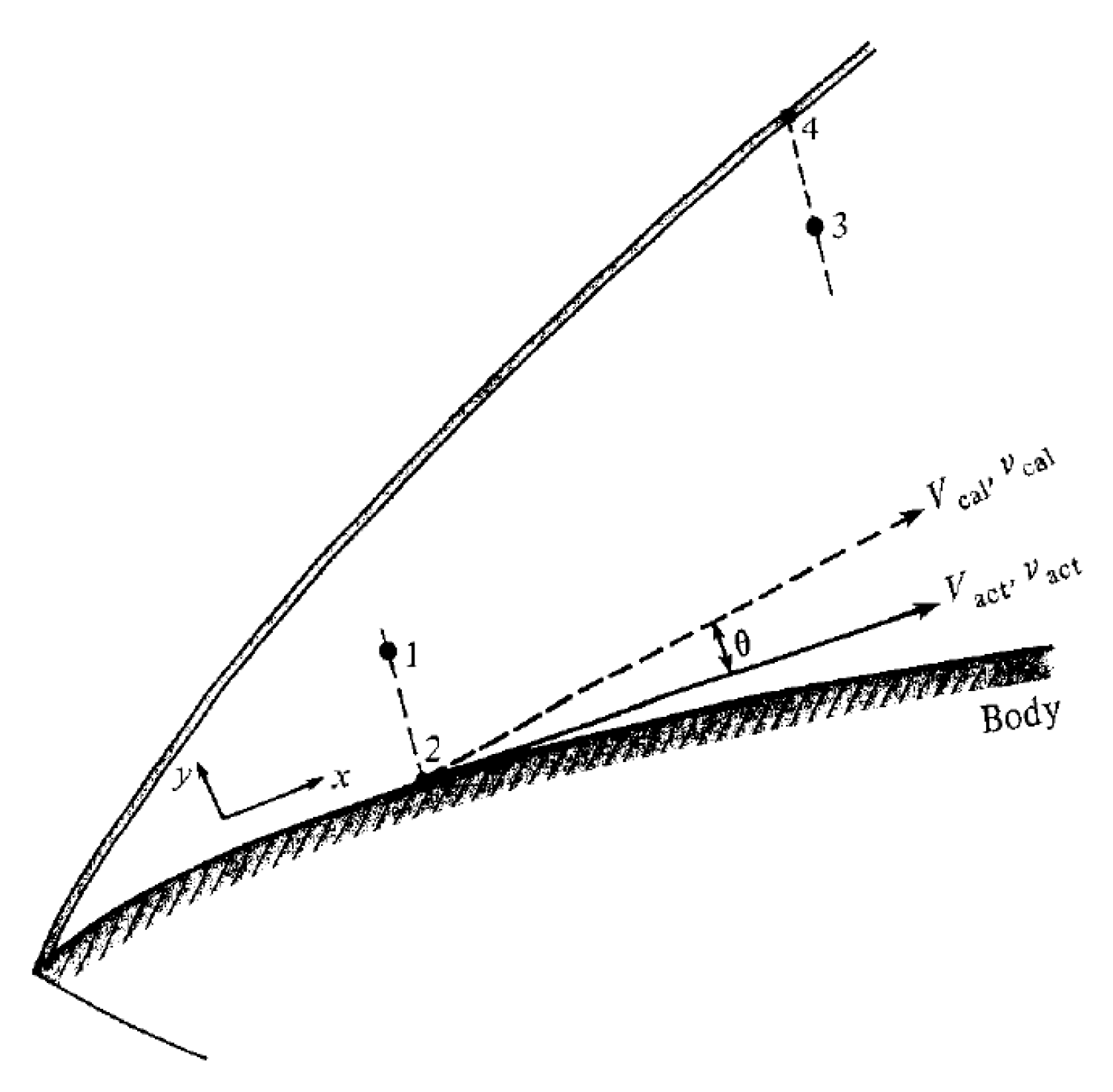

12.4. Boundary Conditions

Figure 18 highlights some challenges of finite differences, namely flow’s boundary conditions. Abbett’s method consist in an algorithm for inviscid, steady and supersonic flow that applies MacCormack’s technique but only with forward differences for both prediction-correction for physical walls, like in point 2.

The previous process will results in calculated velocity,

, that is not tangent to the surface. So a correction must be set as in Equation

152 that is reflected in all flow properties, meaning an isentropic expansion or compression takes place, deviating the flow an angle

.

Abbett’s method can also be applied for nodes downstream of shocks, like point 4, with the prediction-correction consisting on solely forward or reward differences. After the oblique shock, the actual angle of the flow is easily given by Equation

22.

12.5. Stability Criterion

As it has been refereed before, for explicit solvers, must be choose so the algorithm is stable in predicting the solution. Larger values of the previous ratio leads to excessive truncation errors decreasing accuracy.

For instances, it can be argued that, for a vertical line i, the node

should be upstream of the interception of the right and left characteristics of nodes

and

, respectively. Courant-Friedrichs-Lewy (CFL) criterion reflects precisely this and is mathematically formalized in Equation

153.

12.6. Shock Modeling

A

shock-fitting approach, seen in

Figure 19 a) can be implement when the shock localization and angle are known, modeling it as discontinuity in flow’s properties.

A

shock-capturing approach, seen in

Figure 19 b) will find the shock, with the grid covering all the flow and taking free stream properties as boundaries. The shock will be the region with strong properties gradients. Although there’s no prior need of knowing the shock, the grid needs to be denser and some calculations at the far-field are yield that will not be relevant for the final solution

12.7. Turbulence Models

The occurrence of laminar or turbulent flow is dependent on the relative influence of viscous and inertial effects, as described by the Reynolds number. As the Reynolds number increases, the development of a laminar flow into a turbulent flow becomes more likely.

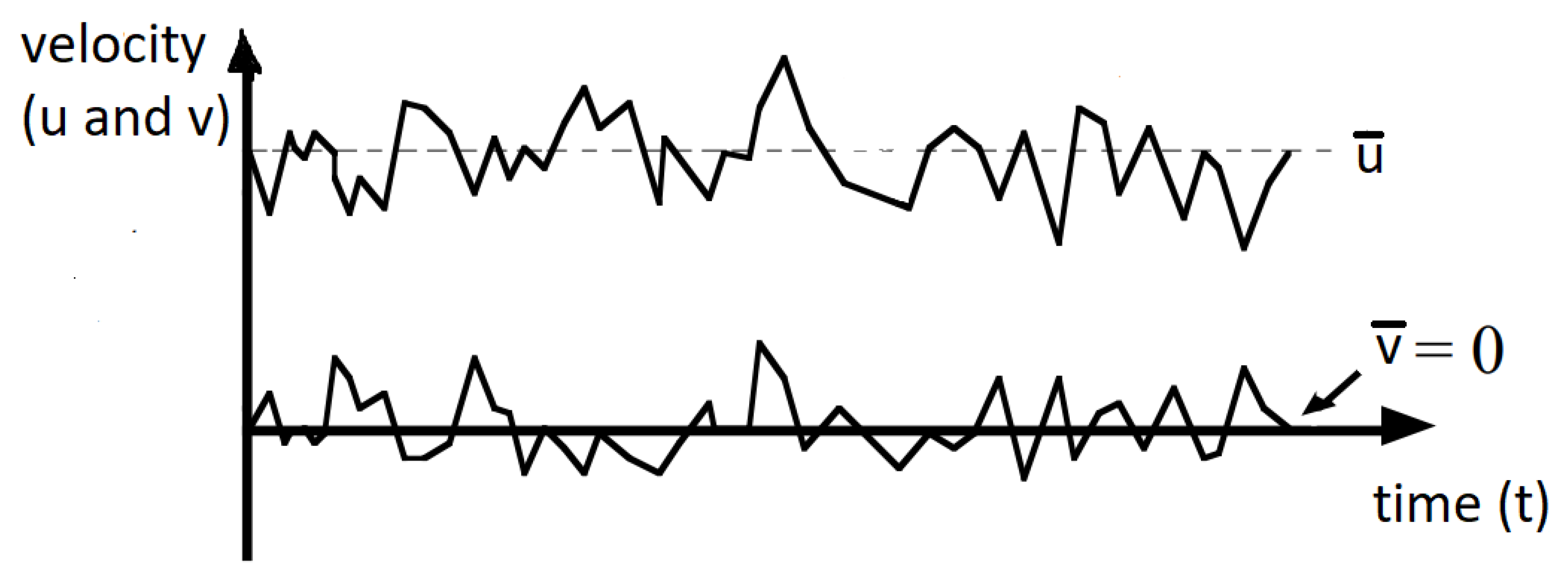

Turbulent flow is characterized by the existence of eddies that create large fluctuations in velocity and other properties, as depicted in

Figure 20. Reynolds’ decomposition states that the value of a velocity component at a certain point is the sum of its average value and a fluctuation that is a function of time, as seen in Equations

154 and

155. It is important to note that turbulent motion is random, and therefore a statistical treatment is essential [

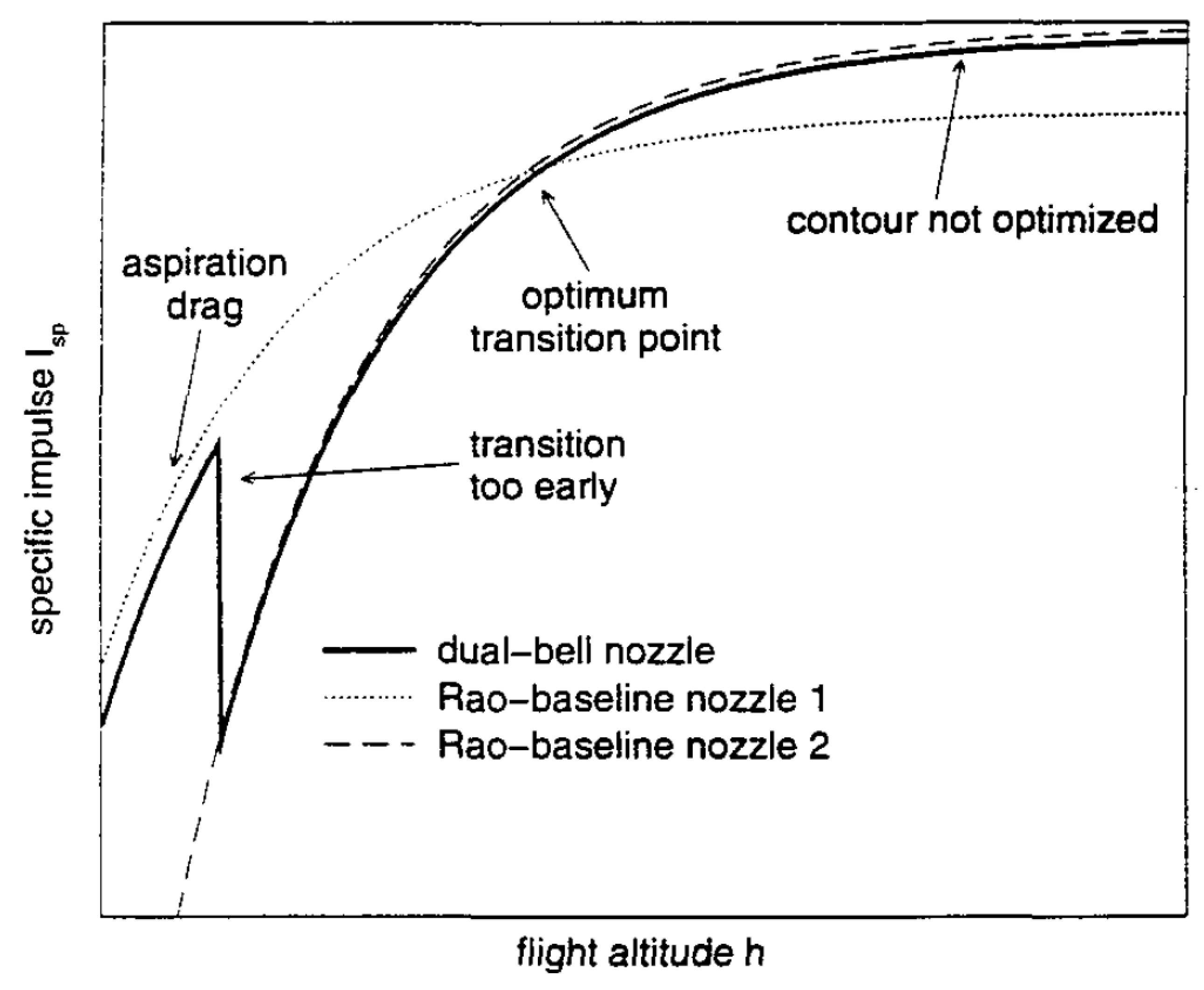

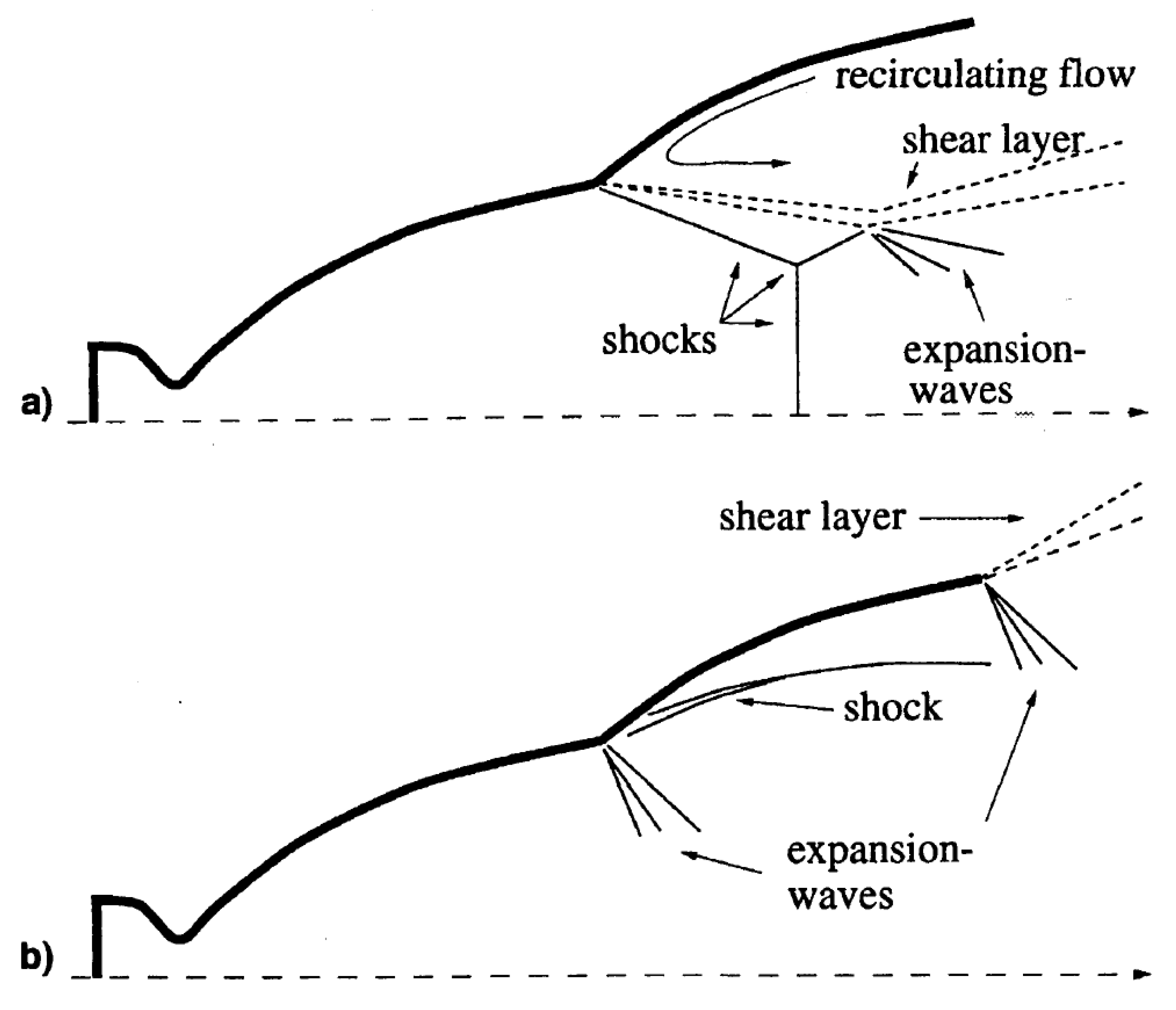

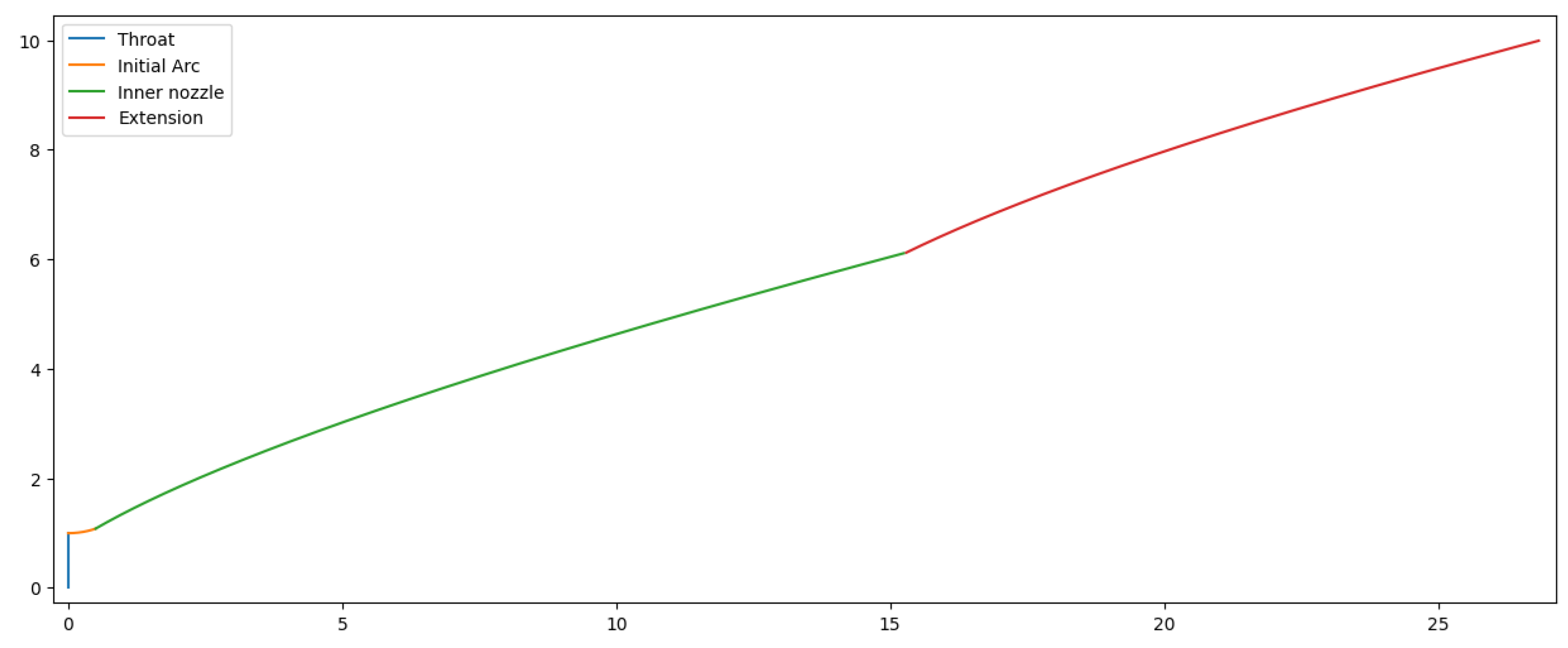

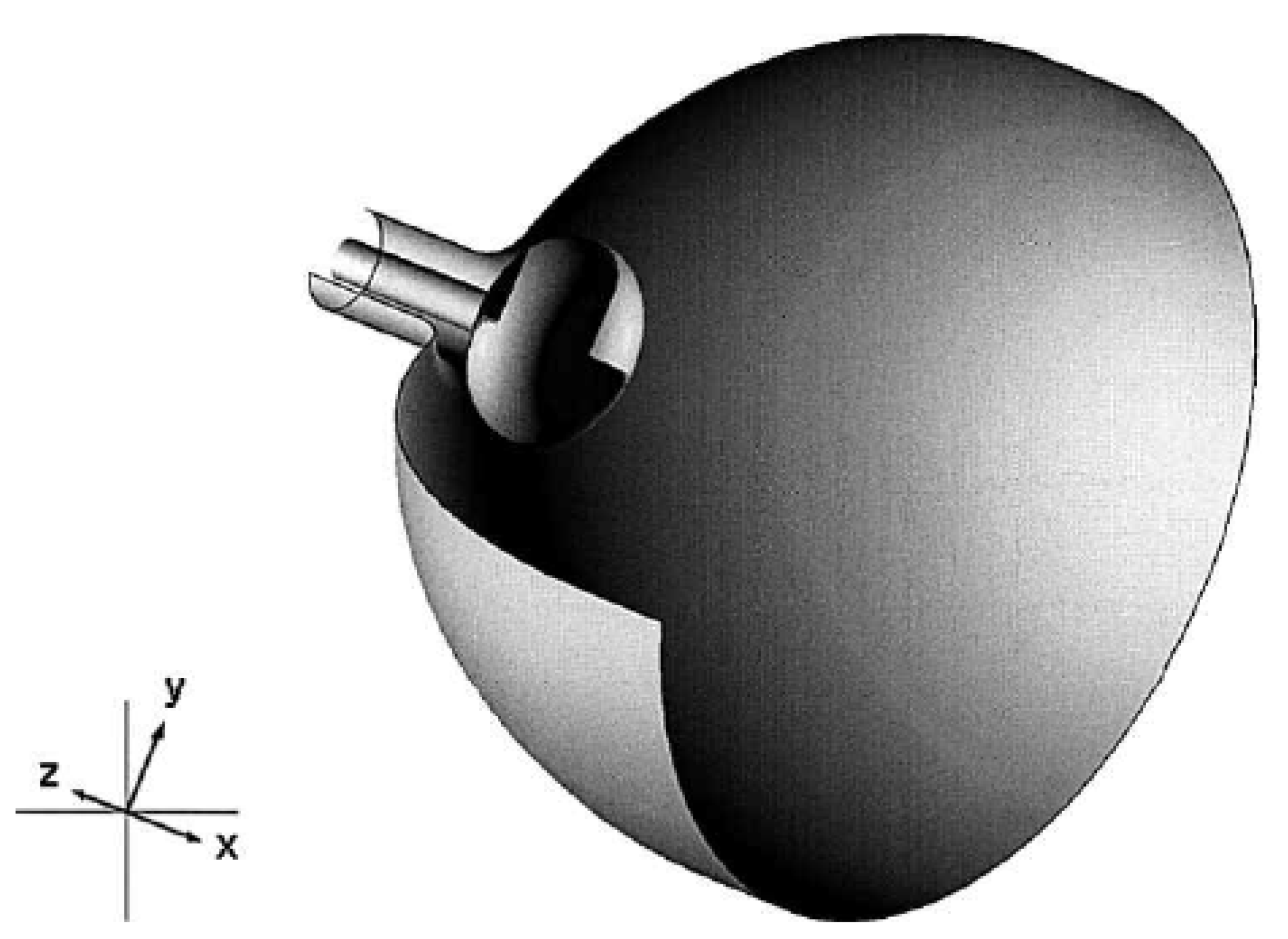

16].