Submitted:

20 March 2025

Posted:

24 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection of Plant Material

2.2. Extraction

2.3. Dilution Preparation

2.4. Inoculum Preparation

2.5. Microbicidal Effect on B. cinerea

2.6. Microbicidal Effect on P. syringae

2.7. Total Phenol Content and Flavonoid Content

2.8. Flavonoid Identification (HPLC)

3. Results

3.1. Extract obtained

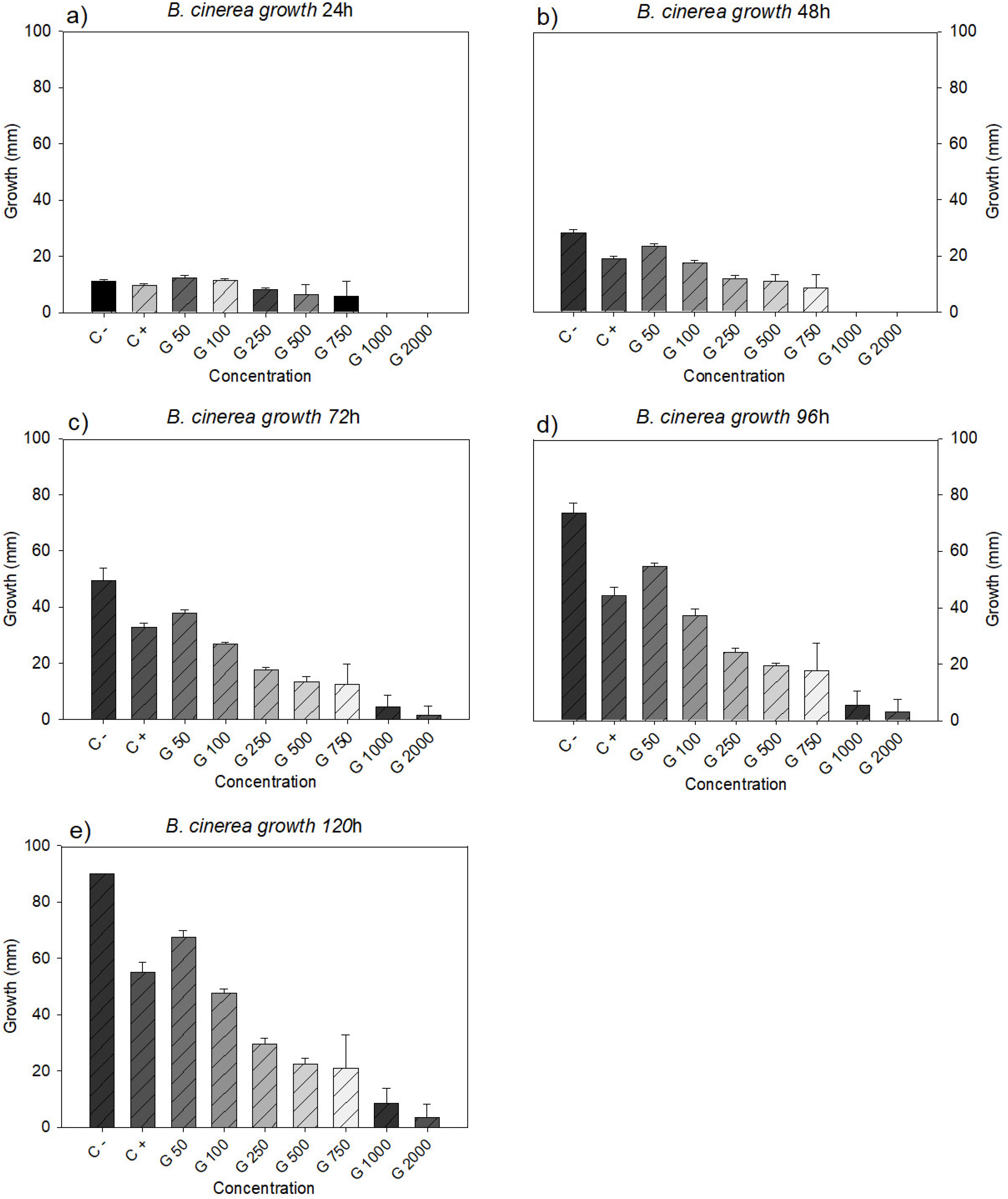

3.2. Fungicidal Effect on B. cinerea

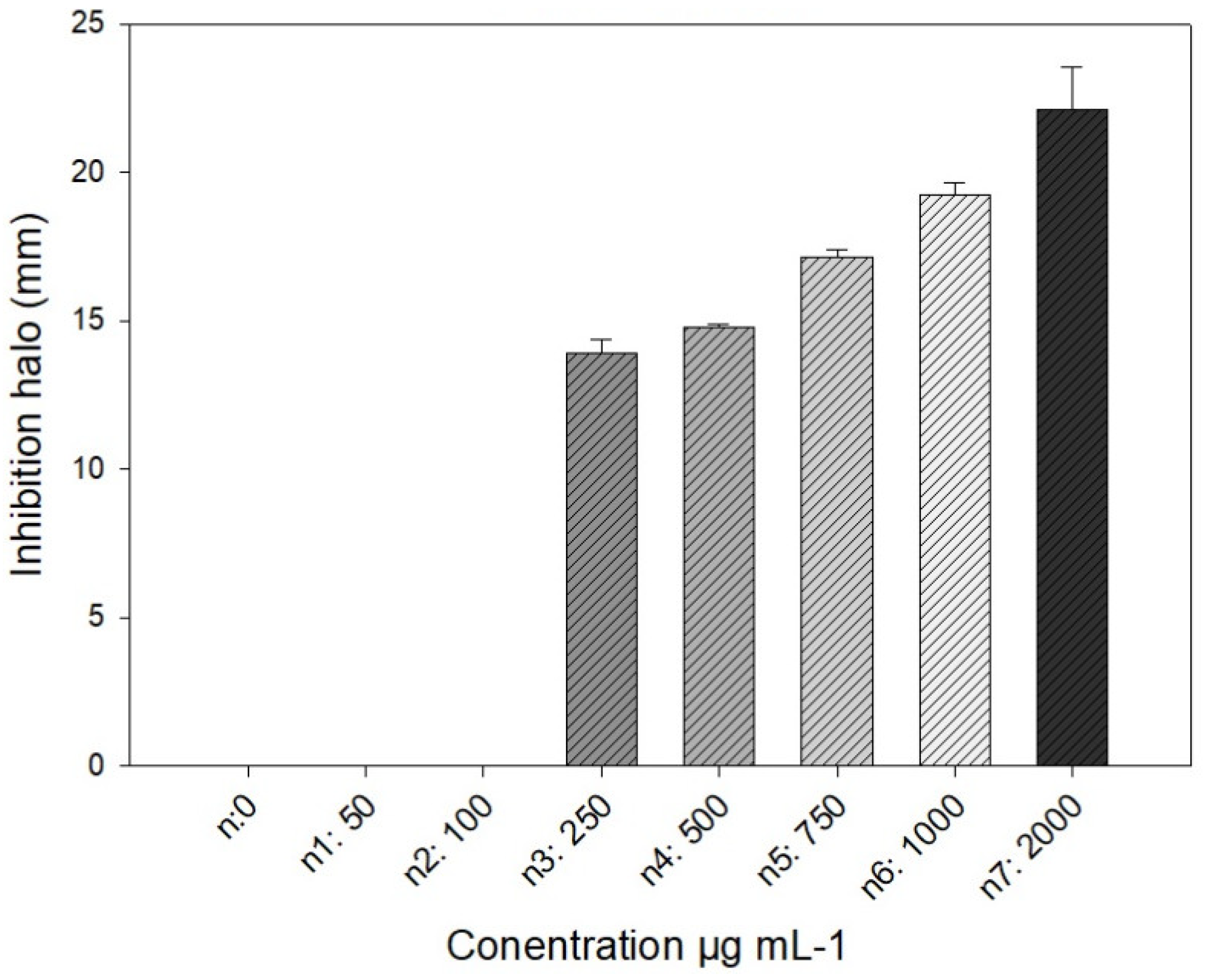

3.3. Bactericidal Effect on P. syringae

3.4. Total Phenol and Flavonoid Content

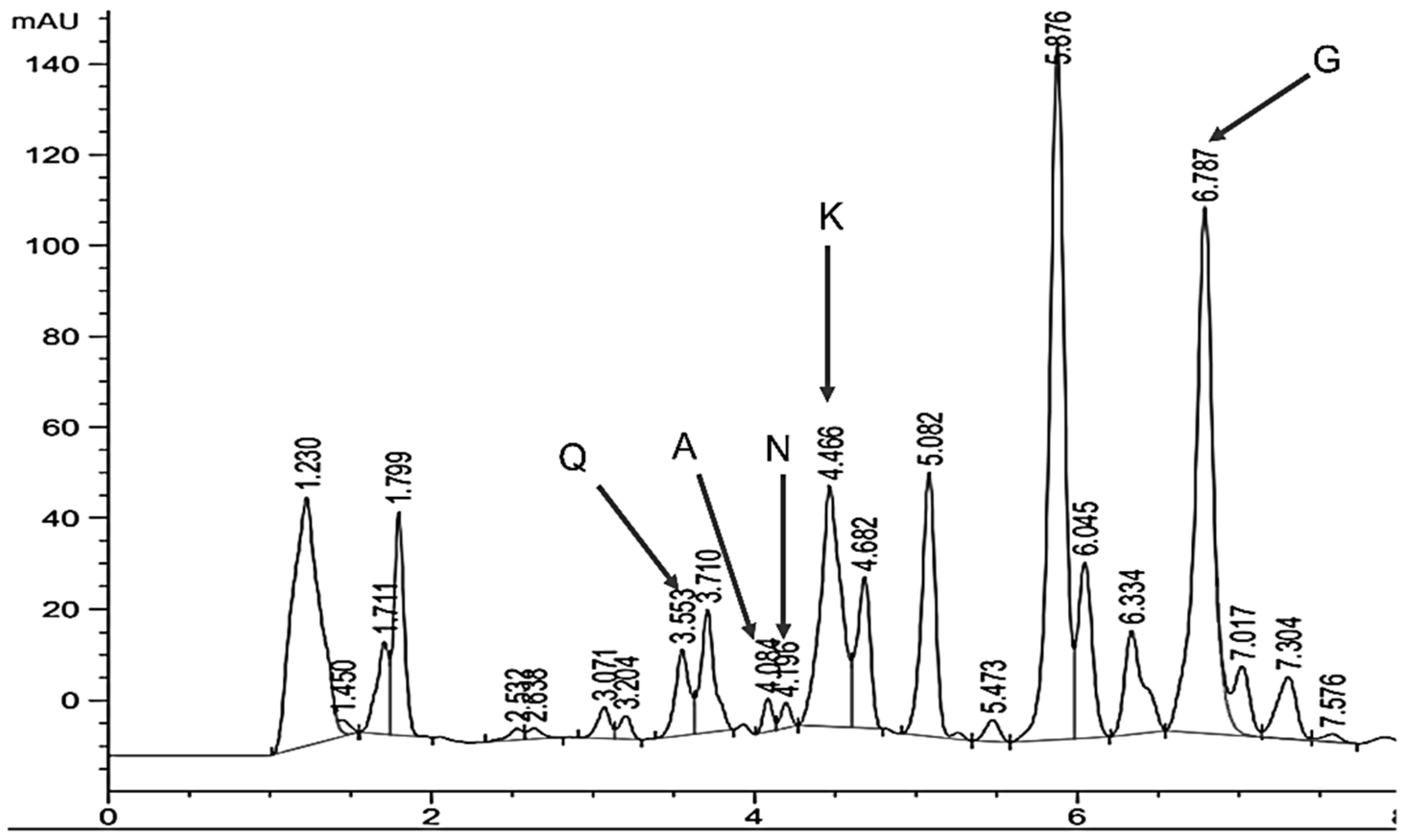

3.5. Compound Identification and Quantification (HPLC)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- SIAP, Servicio de Información Agroalimentaria y Pesquera. (2016). El impacto de las plagas y enfermedades en el sector agrícola. gob.mx. (accessed on 30-05-2024).

- Tudi, M.; Daniel Ruan, H.; Wang, L.; Lyu, J.; Sadler, R.; Connell, D.; Chu, C.; Phung, D.T. Agriculture development, pesticide application and its impact on the environment. IJERPH. 2021, 18(3), 1112- 1135 . [CrossRef]

- Jáquez-Matas, S.V.; Pérez-Santiago, G.; Márquez-Linares, M.A.; Pérez-Verdín, G. Impactos económicos y ambientales de los plaguicidas en cultivos de maíz, alfalfa y nogal en Durango, México. Rev. Int. Contam. Ambie. 2022, 38, 219–233.

- Silveira-Gramont, M.I.; Aldana-Madrid, M.L.; Piri-Santana, J.; Valenzuela-Quintanar, A.I.; Jasa-Silveira, G.; Rodríguez-Olibarria, G. Plaguicidas agrícolas: un marco de referencia para evaluar riesgos a la salud en comunidades rurales en el estado de Sonora, México. Rev. Int. Contam. Ambie, 2018, 34(1), 7–21. [CrossRef]

- 5- Dewey (Molly), F.M.; Grant-Downton, R.. Botrytis-Biology, Detection and quantification. Botrytis – the fungus, the pathogen and its management in agricultural systems. Fillinger S.; Y. Elad, Y. Springer International Publishing. Thiverval-Grignon, France. 2016, pp. 17–34.

- Isman, M. BBotanical Insecticides in the Twenty-First Century—Fulfilling Their Promise? Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2020, 65, 233–249.

- Lengai, G.M.W.; Muthomi, J.W.; Mbega, E.R. Phytochemical activity and role of botanical pesticides in pest management for sustainable agricultural crop production. Scientific African. 2020, 7, e00239. [CrossRef]

- Mesa, V. a. M.; Marín, P., Ocampo, O.; Calle, J.; Monsalve, Z.. Fungicidas a partir de extractos vegetales: Una alternativa en el manejo integrado de hongos fitopatógenos. RIA. 2019, 45(1), 23–30.

- Daraban, G. M.; Hlihor, R.-M.; Suteu, D. Pesticides vs. Biopesticides: From Pest Management to Toxicity and Impacts on the Environment and Human Health. Toxics. 2023, 11(12), 983. [CrossRef]

- García-López, J.C.; Herrera-Medina, R.E.; Rendón-Huerta, J.A.; Negrete-Sánchez, L.O.; Lee-Rangel, H.A.; Álvarez-Fuentes, G. Acaricide Potential of Creosote Bush (Larrea tridentata) Extracts in the Control of Varroa destructor in Apis mellifera. JALSI. 2024, 27(3), 7–20. [CrossRef]

- 11- Millanes Moreno, D.; Mc Caughey-Espinoza, D.M.; García-Baldenegro, V.; Rodríguez Briseño, K.; Retes-López, R.; Lazo-Javalera, F.; Millanes Moreno, D.; Mc Caughey-Espinoza, D.M.; García-Baldenegro, V.; Rodríguez Briseño, K.; Retes-López, R.; Lazo-Javalera, F. Determinación del efecto del aceite esencial de Larrea tridentata sobre el gorgojo Acantocelides obtetus (Say) en frijol almacenado. Idesia (Arica). 2024, 42(2), 19–26. [CrossRef]

- Morales-Ubaldo, A.L.; Rivero-Perez, N.; Avila-Ramos, F.; Aquino-Torres, E.; Prieto-Mendez, J.; Hetta, H.F.; El-Saber Batiha, G.; & Zaragoza-Bastida, A. Bactericidal Activity of Larrea tridentata Hydroalcoholic Extract against Phytopathogenic Bacteria. Agronomy-Basel. 2021, 11(5), 957. [CrossRef]

- Turner, T., Ruiz, G.; Gerstel, J.; Langland, J. Characterization of the antibacterial activity from ethanolic extracts of the botanical, Larrea tridentata. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2021, 21(1), 177. [CrossRef]

- Lira-Saldívar, R.H. Estado Actual del Conocimiento Sobre las Propiedades Biocidas de la Gobernadora [Larrea tridentata (D.C.) Coville]. Revista Mexicana de Fitopatología. 2003, 21(2), 214–222.

- Guerrero-Rodríguez, E.; Solís Gaona, S.; Hernández Castillo, F.D.; Flores Olivas, A.; Sandoval López, V.; & Jasso Cantú, D. Actividad biológica in vitro de extractos de Flourensia cernua D.C. en patógenos de postcosecha: Alternaria alternata (Fr.:Fr.) Keissl., Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (Penz.) Penz. Y Sacc. Y Penicillium digitatum (Pers.:Fr.) Sacc. Revista Mexicana de Fitopatología. 2007, 25(1), 48–63.

- Gonelimali, F.D.; Lin, J.; Miao, W.; Xuan, J.; Charles, F.; Chen, M.; Hatab, S.R.. Antimicrobial Properties and Mechanism of Action of Some Plant Extracts Against Food Pathogens and Spoilage Microorganisms. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2018, 9, 1639 . [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, I.; Moguel Ordóñez, Y.; Acevedo, J.J.; Betancur, D. Calidad microbiológica y actividad antibacteriana de miel producida por Melipona beecheii en Yucatán, México. Revista MVZ Córdoba. 2023, 28, e3175.

- Villagomez Zaldivar, G.; González Victoriano, L.; Chanona Pérez, J.; Ferrer Gonzáles, B.; Gutiérrez Martínez, M.. Obtención y evaluación de propiedades antioxidantes de extractos de orégano (Lippia graveolens), eucalipto (Eucalyptus cinerea) y chile jalapeño (Capsicum annuum cv.). Investigación Y Desarrollo En Ciencia Y Tecnología De Alimentos. 2023, 8, 319–325.

- Hernández Zarate, M.S.; Abraham Juárez, M.R.; Céron García, A.; Gutiérre Chávez, A.J.; Gutiérrez Arenas, D.A.; Avila-Ramos, F. Flavonoids, phenolic content, and antioxidant activity of propolis from various areas of Guanajuato, Mexico. JFST 2017, 2, 607–612. [CrossRef]

- Martins, S.; Amorim, E.L.C.; Sobrinho, T.J.S.P.; Saraiva, A.M.; Pisciottano, M.N.C.; Aguilar, C.N.; Teixeira, J.A.; Mussatto, S.I. Antibacterial activity of crude methanolic extract and fractions obtained from Larrea tridentata leaves. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2013. 41, 306–311. [CrossRef]

- Gómez, J.; Simirgiotis, M.J.; Manrique, S.; Piñeiro, M.; Lima, B., Bórquez, J.; Feresin, G.E.; Tapia, A. UHPLC-ESI-OT-MS Phenolics profiling, free radical scavenging, antibacterial and nematicidal activities of “yellow-brown resins” from Larrea spp. Antioxidants. 2021, 10(2), 185.

- Morales-Márquez, R.; Delgadillo-Ruiz, L., Esparza-Orozco, A.; Delgadillo-Ruiz, E.; Bañuelos-Valenzuela, R.; Valladares-Carranza, B.; Chávez-Ruvalcaba, M.I.; Chávez-Ruvalcaba, F.; Valtierra-Marín, H.E.; Gaytán-Saldaña, N.A.; Mercado-Reyes, M.; Arias-Hernández, L.A. Evaluation of Larrea tridentata extracts and their antimicrobial effects on strains of clinical interest. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26(3), 1032. [CrossRef]

- Morales-Ubaldo, A.L.; Gonzalez-Cortazar, M.; Zaragoza-Bastida, A.; Meza-Nieto, M.A.; Valladares-Carranza, B.; A. Alsayegh, A.; El-Saber Batiha, G.; Rivero-Perez, N. Nor 3′-Demethoxyisoguaiacin from Larrea tridentata Is a Potential Alternative against Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria Associated with Bovine Mastitis. Molecules. 2022, 27(11), 3620. [CrossRef]

- Favela-Hernández, J.M.J.; García, A.; Garza-González, E.; Rivas-Galindo, V.M.; Camacho-Corona, M.R. Antibacterial and antimycobacterial lignans and flavonoids from Larrea tridentata. Phytotherapy Research: PTR. 2012, 26(12), 1957–1960. [CrossRef]

- FAO, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Programa ONU Medio Ambiente América Latina y el Caribe. ¿Por qué es importante reducir el uso de antibióticos en los sistemas agroalimentarios?. (accessed on 13-03-2025).

- Naghavi, M.; Vollset, S.E.; Ikuta, K.S.; Swetschinski, L.R.; Gray, A.P.; Wool, E.E.; Aguilar, G.R.; Mestrovic, T.; Smith, G.; Han, C.; Hsu, R.L.; Chalek, J.; Araki, D.T.; Chung, E.; Raggi, C.; Hayoon, A.G.; Weaver, N.D.; Lindstedt, P.A.; Smith, A.E.; Murray, C.J.L. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance 1990–2021: A systematic analysis with forecasts to 2050. The Lancet. 2024, 404(10459), 1199–1226. [CrosRef] . [CrossRef]

- 27 Shuping, D.S.S.; Eloff, J.N. The use of plants to protect plants and food against fungal pathogens: A review. AJTCAM. 2017, 14(4), 120–127. [CrossRef]

- Sagaste, C.A.; Montero, G.; Coronado, M.A.; Ayala, J.R.; León, J.Á., García, C.; Rojano, B.A.; Rosales, S.; Montes, D.G. Creosote Bush (Larrea tridentata) extract assessment as a green antioxidant for biodiesel. Molecules. 2019, 24(9), 1786. [CrossRef]

- Cerón-Ramírez, L.B.; Talamantes-Gómez, J.M.; Gochi, L.C.; Márquez-Mota, C.C. Efecto del solvente de extracción sobre el contenido compuestos fenólicos de hojas, tallo y planta completa de Tithonia diversifolia. AIA. 2021, 25(3), 134–135.

- Hyder, P.W., Fredrickson, E.L.; Estell, R.E.; Tellez, M.; Gibbens, R.P. Distribution and concentration of total phenolics, condensed tannins, and nordihydroguaiaretic acid (NDGA) in creosotebush (Larrea tridentata). Biochem. Syst. Ecol.. 2002, 30(10), 905–912. [CrossRef]

- Cereceres-Aragón, A.; Rodrigo-García, J.; Álvarez-Parrilla, E.; Rodríguez-Tadeo, A.; Cereceres-Aragón, A.; Rodrigo-García, J.; Álvarez-Parrilla, E.; Rodríguez-Tadeo, A. Ingestión de compuestos fenólicos en población adulta mayor. Nutr Hosp. 2019, 36(2), 470–478.

- Abd-elfattah, M.; Maina, N.; Kareru, P.G.; El-Shemy, H.A. Antioxidant potential of eight selected Kenyan medicinal plants. Egypt. J. Chem. 2023, 66(1), 545–553. [CrossRef]

- Thirumurugan, D.; Cholarajan, A.; Vijayakumar, S.S.S.R.; R., Thirumurugan, D., Cholarajan, A.; Vijayakumar, R. An Introductory Chapter: Secondary Metabolites. Secondary metabolites - sources and applications 1st ed.; Vijayakumar, R., Suresh, S. S. R. IntechOpen London, United Kingdom, 2018. Volume 1, pp. 3-21.

- Andrade-Bustamante, G.; García-López, A.M.; Cervantes-Díaz, L.; Aíl-Catzim, C.E., Borboa-Flores, J. Rueda-Puente, E.O. Estudio del potencial biocontrolador de las plantas autóctonas de la zona árida del noroeste de México: Control de fitopatógenos. REV FAC CIENC AGRAR. 2017, 49(1), 127–142.

- Vázquez-Cervantesa, G.I.; Villaseñor-Aguayoa, K.; Hernández-Damiána, J.; Aparicio-Trejoa, O.E., Medina-Camposa, O.N.; López-Marureb, R.; Pedraza-Chaverria, J. Antitumor Effects of Nordihydroguaiaretic Acid (NDGA) in bladder T24 cancer cells are related to increase in ROS production and mitochondrial leak respiration. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2018, 13(11), 1523 - 1526. [CrossRef]

- Martins, S.; Mussatto, S.I.; Aguilar, C.N.; Teixeira, J.A.; Martins, S.; Mussatto, S.I.; Aguilar, C.N.; Teixeira, J.A. Antioxidant capacity and NDGA content of Larrea tridentata (a desert bush) leaves extracted with different solvents. J. Biotechnol. 2010 150, 500. [CrossRef]

- Martins, S.; Amorim, E.L.C.; Sobrinho, T.J.S.P.; Saraiva, A.M.; Pisciottano, M.N.C.; Aguilar, C.N.; Teixeira, J.A.; Mussatto, S.I. Antibacterial activity of crude methanolic extract and fractions obtained from Larrea tridentata leaves. IND CROP PROD. 2013, 41, 306–311. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G.; Negi, H.S.; Ghosh, P., Sharma, S.; Ojha, P.K.; Singh, V.; Chandel, S. Sensitivity of Botrytis cinerea isolate collected from gladiolus against selected fungicides, plant oils and botanicals in North India. Not Bot Horti Agrobo. 2023, 51(4), 13360. [CrossRef]

- Chavan, N.; Janjal, P.H.; Jadhao, K.; Kale, S.; Shinde, A. Synergistic effect of medicinal plant extracts and antibiotics against bacterial pathogens. J. Pharm. Innov. 2023, 12(4), 1322–1328.

- Kanyairita, G.G.; Mortley, D.G.; Collier, W.E.; Fagbodun, S.; Mweta, J.M.; Uwamahoro, H.; Dowell, L.T.; Mukuka, M.F. An in vitro evaluation of industrial hemp extracts against the phytopathogenic bacteria Erwinia carotovora, Pseudomonas syringae pv. Tomato, and Pseudomonas syringae pv. Tabaci. Molecules. 2024, 29(24) 5902.

- Shao, W.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, Z. Advances in Understanding Fungicide Resistance in Botrytis cinerea in China. Phytopathology. 2021, 111(3), 455–463. [CrossRef]

- Weber, R.W.S.; Hahn, M. Grey mould disease of strawberry in northern Germany: Causal agents, fungicide resistance and management strategies. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103(4), 1589–1597. [CrossRef]

- Abbey, J.A.; Percival, D.; Abbey, Lord, Asiedu, S.K.; Prithiviraj, B.; Schilder, A. (2019). Biofungicides as alternative to synthetic fungicide control of grey mould (Botrytis cinerea) – prospects and challenges. Biocontrol Science and Technology. [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.U.; Arshad, M.; Mukhtar, K.; Nabi, B.G.; Goksen, G.; Starowicz, M.; Nawaz, A.; Ahmad, I.; Walayat, N.; Manzoor, M.F.; Aadil, R.M. Natural plant extracts: An update about novel spraying as an alternative of chemical pesticides to extend the postharvest shelf life of fruits and vegetables. Molecules. 2022, 27(16) 5152. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Castro, A.; Torres-Herrera, S.; Calleros, A.D.; Romero-García, A.; Silva-Flores, M. Extractos vegetales para el control de Fusarium oxysporum, Fusarium solani y Rhizoctonia solani, una alternativa sostenible para la agricultura. Abanico Agroforestal. 2020, 2(0), 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Boiteux, J., Espino, M.; Fernández, M. de los Á.; Pizzuolo, P.; Silva, M.F. ECo-friendly postharvest protection: Larrea cuneifolia-nades extract against Botrytis cinerea. Rev. FCA UNCUYO. 2019, 51(2), 427-437.

- Flores-Bedregal, E.; Puelles-Román, J.; Mendoza-Moncada, A.; Chacon-Rodriguez, K.; Terrones-Ramirez, L.; Mendez-Vilchez, W. Actividad antifúngica in vitro de extractos de ramas/hojas de arándano y semilla de palta contra Botrytis sp. J. Agric. Sci. 2023, 13(2), 55-66.

- Bressan Merlo, M.E. “Larrea ameghinoi Speg.“ Jarilla rastrera”: efecto antioxidante, antimicrobiano y estudio químico. bachelor level. Degree in biology. San Juan, Argentina. 2024.

- Šernaitė, L.; Rasiukevičiūtė, N.; Valiuškaitė, A. Application of Plant Extracts to Control Postharvest Gray Mold and Susceptibility of Apple Fruits to B. cinerea from Different Plant Hosts. Foods. 2020, 9(10) .

| Extract yield | |

|---|---|

| Dry matter weight | 50.0 g |

| Extract obtained | 11.7 g |

| Dry matter yield | 23.4 % |

| Concentration | Inhibition (%) |

|---|---|

| C- | 0 ±0 |

| C+ | 39.62 ±3.81 |

| 50 | 24.91 ±19.86 |

| 100 | 46.97 ±1.59 |

| 250 | 67.1 ±2.24 |

| 500 | 74.93 ±2.56 |

| 750 | 76.7 ±7.98 |

| 1000 | 90.42 ±5.92 |

| 2000 | 96.1 ±5.41 |

| Phenol content EAG | |

|---|---|

| FTEAG mg gE-1 | 291.02 |

| FTEAG mg gMS-1 | 73.92 |

| Fl EQ mg gE-1 | 598.27 |

| Fl EQ mg gMS-1 | 153.40 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).