Submitted:

17 March 2025

Posted:

24 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Induction of CRO Tolerance, Assessment of Tolerance and CRO Susceptibility

RNA-Sequencing and Bioinformatic Analyses

Results

- i.

- Condition 1: 10.2 (control sample) vs 10.3, 10.4, 10.7, 10.8 (tolerant samples) isolates from day 1 CRO-exposure

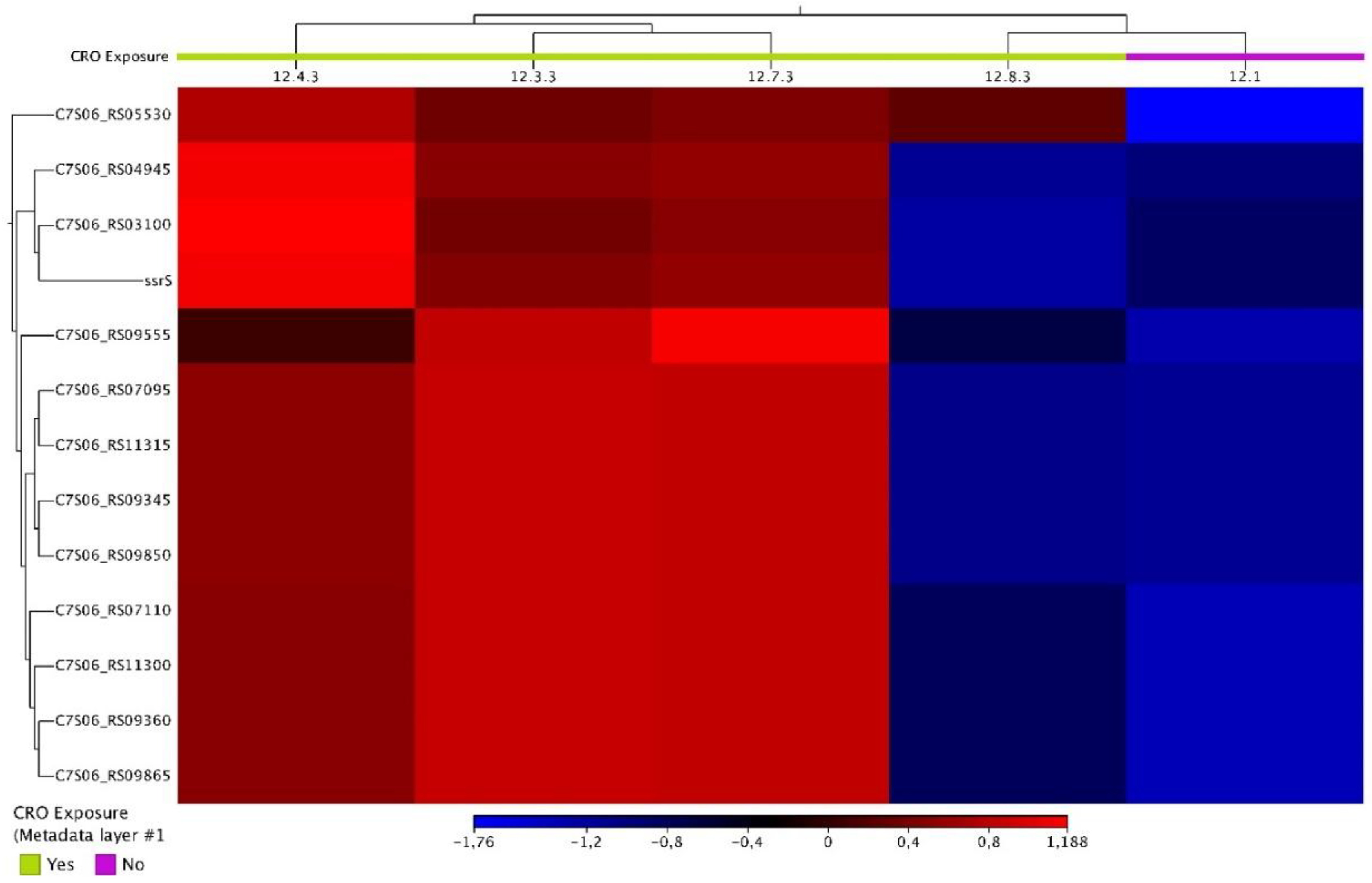

- ii.

- Condition 2: 12.1 (control sample) vs. 12.3.3, 12.4.3, 12.7.3, and 12.8.3 (tolerant samples) isolates from day 3 CRO-exposure

- iii.

- Condition 3: 16.1 (control sample) vs. 16.3.-2.3, 16.4.3, 16.7-2.3, and 16.8-2.3. (tolerant samples) isolates from day 7 CRO-exposure

- iv.

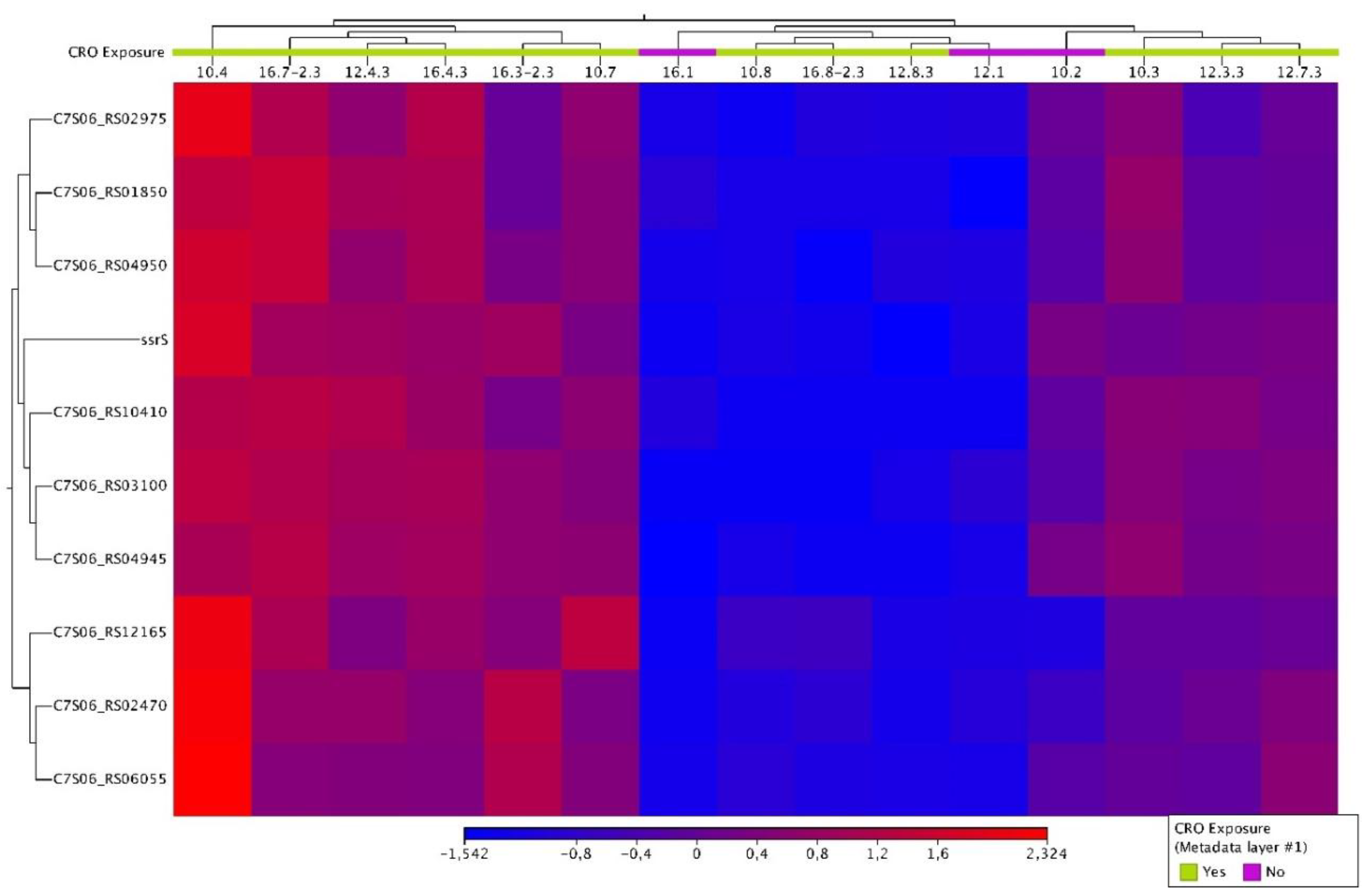

- Condition 4: all the control samples (n=3) vs. all the tolerant samples (n=12)

Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Westblade, L.F.; Errington, J.; Dörr, T. Antibiotic tolerance. PLoS Pathog 2020, 16, e1008892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handwerger, S.; Tomasz, A. Antibiotic tolerance among clinical isolates of bacteria. Rev Infect Dis 1985, 7, 368–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eric, M.; Pratt, W.B. The antimicrobial drugs; Eric M. Scholar, William B. Pratt., Second edi.; Oxford University Press: New York, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, J.M. Determination of minimum inhibitory concentrations. J Antimicrob Chemother 2001, 48 (Suppl 1), 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotková, H.; Cabrnochová, M.; Lichá, I.; et al. Evaluation of TD test for analysis of persistence or tolerance in clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. J Microbiol Methods 2019, 167, 105705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, W. Microbial persistence. Yale J Biol Med 1958, 30, 257–291. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brauner, A.; Fridman, O.; Gefen, O.; Balaban, N.Q. Distinguishing between resistance, tolerance and persistence to antibiotic treatment. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trastoy, R.; Manso, T.; Fernández-García, L.; et al. Mechanisms of Bacterial Tolerance and Persistence in the Gastrointestinal and Respiratory Environments. Clin Microbiol Rev 2018, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, B.R.; Rozen, D.E. Non-inherited antibiotic resistance. Nat Rev Microbiol 2006, 4, 556–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin-Reisman, I.; Ronin, I.; Gefen, O.; et al. Antibiotic tolerance facilitates the evolution of resistance. Science (80- ) 2017, 355, 826–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin-Reisman, I.; Brauner, A.; Ronin, I.; Balaban, N.Q. Epistasis between antibiotic tolerance, persistence, and resistance mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2019, 116, 14734–14739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huemer, M.; Mairpady Shambat, S.; Brugger, S.D.; Zinkernagel, A.S. Antibiotic resistance and persistence-Implications for human health and treatment perspectives. EMBO Rep 2020, 21, e51034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kussell, E.; Kishony, R.; Balaban, N.Q.; Leibler, S. Bacterial persistence: a model of survival in changing environments. Genetics 2005, 169, 1807–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, K. Multidrug tolerance of biofilms and persister cells. Bact biofilms 2008, 107–131. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarovits, G.; Gefen, O.; Cahanian, N.; et al. Prevalence of Antibiotic Tolerance and Risk for Reinfection Among Escherichia coli Bloodstream Isolates: A Prospective Cohort Study. Clin Infect Dis an Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am 2022, 75, 1706–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santi, I.; Manfredi, P.; Maffei, E.; et al. Evolution of antibiotic tolerance shapes resistance development in chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. MBio 2021, 12, e03482–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, N.D.; Born, S.E.M.; Robertson, G.T.; et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis precursor rRNA as a measure of treatment-shortening activity of drugs and regimens. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conlon, B.P. Staphylococcus aureus chronic and relapsing infections: Evidence of a role for persister cells: An investigation of persister cells, their formation and their role in S. aureus disease. Bioessays 2014, 36, 991–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salina, E.G.; Makarov, V. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Dormancy: How to Fight a Hidden Danger. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatov, D.V.; Salina, E.G.; Fursov, M.V.; et al. Dormant non-culturable Mycobacterium tuberculosis retains stable low-abundant mRNA. BMC Genomics 2015, 16, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miki, M.; Miyu, H.; Madhuri, S.; et al. Genetic and Transcriptomic Analyses of Ciprofloxacin-Tolerant Staphylococcus aureus Isolated by the Replica Plating Tolerance Isolation System (REPTIS). Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2019, 63, 10.1128–aac.02019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, E.J.; Andrews, I.W.; Grote, A.T.; et al. Modulating the evolutionary trajectory of tolerance using antibiotics with different metabolic dependencies. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schildkraut, J.A.; Coolen, J.P.M.; Burbaud, S.; et al. RNA Sequencing Elucidates Drug-Specific Mechanisms of Antibiotic Tolerance and Resistance in Mycobacterium abscessus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2022, 66, e0150921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balduck, M.; Laumen, J.G.E.; Abdellati, S.; et al. Tolerance to Ceftriaxone in Neisseria gonorrhoeae: Rapid Induction in WHO P Reference Strain and Detection in Clinical Isolates. Antibiot 2022, 11, 1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoharan-Basil, S.S.; Balduck, M.; Abdellati, S.; et al. Enolase is implicated in the emergence of gonococcal tolerance to ceftriaxone. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balduck, M.; Strikker, A.; Gestels, Z.; et al. The Prevalence of Antibiotic Tolerance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae Varies by Anatomical Site. Pathogens 2024, 13, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, D.G.; Goldman, J.D.; Demple, B.; Levy, S.B. Role of the acrAB locus in organic solvent tolerance mediated by expression of marA, soxS, or robA in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 1997, 179, 6122–6126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Haycocks, J.R.J.; Middlemiss, A.D.; et al. The multiple antibiotic resistance operon of enteric bacteria controls DNA repair and outer membrane integrity. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-H.; Di, Y.P. Analysis of RNA Sequencing Data Using CLC Genomics Workbench. Methods Mol Biol 2020, 2102, 61–113. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dong, H.; Nilsson, L.; Kurland, C.G. Co-variation of tRNA abundance and codon usage in Escherichia coli at different growth rates. J Mol Biol 1996, 260, 649–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, M.A.; Fehler, A.O.; Lo Svenningsen, S. Transfer RNA instability as a stress response in Escherichia coli: Rapid dynamics of the tRNA pool as a function of demand. RNA Biol 2018, 15, 586–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassarman, K.M. 6S RNA, a Global Regulator of Transcription. Microbiol Spectr 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storz, G.; Vogel, J.; Wassarman, K.M. Regulation by small RNAs in bacteria: expanding frontiers. Mol Cell 2011, 43, 880–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmqvist, E.; Wagner, E.G.H. Impact of bacterial sRNAs in stress responses. Biochem Soc Trans 2017, 45, 1203–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burenina, O.Y.; Elkina, D.A.; Ovcharenko, A.; et al. Involvement of E. coli 6S RNA in Oxidative Stress Response. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhu, L.; Yu, Z.; et al. 6S-1 RNA Contributes to Sporulation and Parasporal Crystal Formation in Bacillus thuringiensis. Front Microbiol 2020, 11, 604458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beare, P.A.; Unsworth, N.; Andoh, M.; et al. Comparative genomics reveal extensive transposon-mediated genomic plasticity and diversity among potential effector proteins within the genus Coxiella. Infect Immun 2009, 77, 642–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.; Brewer, M.N.; Elshahed, M.S.; Shaw, E.I. Comparative Transcriptomics and Genomics from Continuous Axenic Media Growth Identifies Coxiella burnetii Intracellular Survival Strategies. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kertesz, M.A. Bacterial transporters for sulfate and organosulfur compounds. Res Microbiol 2001, 152, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yurgel, S.N.; Rice, J.; Mulder, M.; Kahn, M.L. GlnB/GlnK PII proteins and regulation of the Sinorhizobium meliloti Rm1021 nitrogen stress response and symbiotic function. J Bacteriol 2010, 192, 2473–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, T.P.; Shauger, A.E.; Kustu, S. Salmonella typhimurium apparently perceives external nitrogen limitation as internal glutamine limitation. J Mol Biol 1996, 259, 589–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javelle, A.; Severi, E.; Thornton, J.; Merrick, M. Ammonium sensing in Escherichia coli. Role of the ammonium transporter AmtB and AmtB-GlnK complex formation. J Biol Chem 2004, 279, 8530–8538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, P.; Peliska, J.A.; Ninfa, A.J. Enzymological characterization of the signal-transducing uridylyltransferase/uridylyl-removing enzyme (EC 2.7.7.59) of Escherichia coli and its interaction with the PII protein. Biochemistry 1998, 37, 12782–12794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, F.Y.S.; Hatzis, C.L.; Lau, A.; et al. Treatment efficacy for pharyngeal Neisseria gonorrhoeae: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Antimicrob Chemother 2020, 75, 3109–3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenyon, C.; Laumen, J.; Manoharan-Basil, S. Choosing New Therapies for Gonorrhoea: We Need to Consider the Impact on the Pan-Neisseria Genome. A Viewpoint. Antibiot 2021, 10, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| CRO exposure [in days] | ||||||||

| Days (d) | d0 | d1 | d2 | d3 | d4 | d5 | d6 | d7 |

| Control 1 | - | 10.2 | - | 12.1 | - | - | - | 16.1 |

| Control 2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Lineage 1 | - | 10.3 T | 11.3-2.3 T | 12.3.3 T | 13.3.3 T | 14.3.3 T | 15.3-2.3 T | 16.3-2.3 T |

| Lineage 2 | - | 10.4 T | 11.4-2.3 T | 12.4.3 T | 13.4.3 T | 14.4.3 T | 15.4-2.3 T | 16.4-2.3 T |

| Lineage 3 | - | - | 11.5-2.3 T | - | - | - | - | 16.5-2.3 T |

| Lineage 4 | - | - | - | 12.6.3 T | - | - | - | 16.6-2.3 T |

| Lineage 5 | - | 10.7 T | 11.7-2.3 T | 12.7.3 T | 13.7.3 T | 14.7.3 T | 15.7.3 T | 16.7-2.3 T |

| Lineage 6 | - | 10.8 T | 11.8-2.3 T | 12.8.3 T | - | - | - | 16.8-2.3 T |

| Condition | Samples | Name | Product | Log2 fold change | P-value | FDR p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition 1 | 10.2 vs 10.3, 10.4, 1.0.7, 10.8 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Condition 2 | 12.1 vs 12.3.3, 12.4.3, 12.7.3, 12.8.3 | C7S06_RS03100 | tRNA-Ser | -7.39860353 | 1.38E-06 | 2.84E-04 |

| C7S06_RS04945 | tRNA-Leu | -8.83399392 | 2.96E-08 | 1.34E-05 | ||

| C7S06_RS05530 | helix-turn-helix domain-containing protein | -6.9900684 | 1.34E-06 | 2.84E-04 | ||

| C7S06_RS07095 | 23S ribosomal RNA | -7.36462585 | 6.27E-07 | 2.25E-04 | ||

| C7S06_RS07110 | 16S ribosomal RNA | -8.49118611 | 1.91E-09 | 1.13E-06 | ||

| C7S06_RS09345 | 23S ribosomal RNA | -7.36644228 | 6.99E-07 | 2.25E-04 | ||

| C7S06_RS09360 | 16S ribosomal RNA | -8.50896375 | 2.00E-09 | 1.13E-06 | ||

| C7S06_RS09555 | hypothetical protein | -3.17366339 | 3.48E-06 | 6.55E-04 | ||

| C7S06_RS09850 | 23S ribosomal RNA | -7.37838277 | 9.49E-07 | 2.38E-04 | ||

| C7S06_RS09865 | 16S ribosomal RNA | -8.55848201 | 1.93E-09 | 1.13E-06 | ||

| ssrS | 6S RNA | -4.0081717 | 1.04E-04 | 0.017997931 | ||

| C7S06_RS11300 | 16S ribosomal RNA | -8.57394491 | 1.10E-09 | 1.13E-06 | ||

| C7S06_RS11315 | 23S ribosomal RNA | -7.34451019 | 8.95E-07 | 2.38E-04 | ||

| Condition 3 | 16.1 vs 16.3.3, 16.4.3, 16.7-2.3, 16.8-2.3 | secB | protein-export chaperone SecB | -1.84506299 | 1.12E-04 | 9.76E-03 |

| C7S06_RS01160 | 2,3-diphosphoglycerate-dependent phosphoglycerate mutase | -1.28680155 | 7.56E-04 | 0.035587745 | ||

| C7S06_RS01850 | tRNA-Ser | -7.99931846 | 1.70E-06 | 4.27E-04 | ||

| C7S06_RS02470 | IS1595 family transposase | -3.02614034 | 3.15E-06 | 5.92E-04 | ||

| htpX | protease htpX | -1.91863904 | 4.27E-04 | 0.023548408 | ||

| C7S06_RS02975 | tRNA-Gln | -5.7211052 | 1.49E-05 | 1.98E-03 | ||

| cysT | sulfate ABC transporter permease subunit CysT | 1.46371918 | 1.68E-04 | 0.012145005 | ||

| C7S06_RS03025 | isoprenylcysteine carboxyl methyltransferase family protein | -1.30810263 | 2.18E-04 | 0.014056098 | ||

| C7S06_RS03100 | tRNA-Ser | -15.0233146 | 5.45E-04 | 0.026758275 | ||

| C7S06_RS03105 | tRNA-Ser | -7.48792977 | 2.47E-04 | 0.015104502 | ||

| C7S06_RS03165 | hypothetical protein | -6.48897383 | 2.84E-06 | 5.82E-04 | ||

| C7S06_RS03180 | hypothetical protein | -3.58579449 | 1.59E-05 | 1.99E-03 | ||

| C7S06_RS03675 | carbonic anhydrase family | -1.83404995 | 2.14E-04 | 0.014056098 | ||

| C7S06_RS04010 | alpha-hydroxy-acid oxidizing protein | -2.16189144 | 5.07E-05 | 4.98E-03 | ||

| glnD | [protein-PII] uridylyltransferase | 1.13672092 | 4.82E-04 | 0.024762705 | ||

| C7S06_RS04945 | tRNA-Leu | -16.2019008 | 1.93E-04 | 0.013209519 | ||

| C7S06_RS04950 | tRNA-Ser | -8.19485807 | 1.55E-07 | 1.17E-04 | ||

| C7S06_RS05295 | serine hydroxymethyltransferase | -1.44687599 | 1.30E-04 | 0.010872726 | ||

| C7S06_RS05355 | sulfate ABC transporter substrate-binding protein | 1.20861114 | 8.61E-04 | 0.03813733 | ||

| C7S06_RS05905 | protein-disulfide reductase DsbD | -1.94221647 | 8.44E-04 | 0.03813733 | ||

| C7S06_RS06055 | hypothetical protein | -2.92315591 | 2.87E-05 | 3.24E-03 | ||

| C7S06_RS06120 | nucleoid-associated protein | -1.05820139 | 5.62E-04 | 0.027017799 | ||

| C7S06_RS06180 | nitronate monooxygenase family protein | -1.47848462 | 4.65E-04 | 0.024439693 | ||

| C7S06_RS13545 | glutamate dehydrogenase | -2.85215757 | 2.35E-04 | 0.014715194 | ||

| C7S06_RS06985 | hemolysin III family protein | -2.22464042 | 2.37E-05 | 2.82E-03 | ||

| C7S06_RS07095 | 23S ribosomal RNA | -8.91263195 | 1.07E-05 | 1.85E-03 | ||

| C7S06_RS07110 | 16S ribosomal RNA | -9.86029166 | 4.90E-07 | 1.61E-04 | ||

| C7S06_RS07485 | PepSY domain-containing protein | 1.81879489 | 4.40E-04 | 0.023678349 | ||

| C7S06_RS07550 | GrxB family glutaredoxin | -1.79669437 | 1.67E-04 | 0.012145005 | ||

| grpE | nucleotide exchange factor GrpE | -1.53580284 | 8.15E-05 | 7.67E-03 | ||

| C7S06_RS08065 | NAD(P)H-dependent oxidoreductase | -3.44183551 | 1.08E-04 | 9.75E-03 | ||

| xth | exodeoxyribonuclease III | -1.15381669 | 5.19E-04 | 0.026030321 | ||

| C7S06_RS08615 | metalloregulator ArsR/SmtB family transcription factor | -1.88716147 | 1.99E-06 | 4.50E-04 | ||

| C7S06_RS08785 | hypothetical protein | -2.31744916 | 3.43E-05 | 3.69E-03 | ||

| C7S06_RS08795 | immunity 41 family protein | -4.78449117 | 0 | 0 | ||

| C7S06_RS09345 | 23S ribosomal RNA | -8.94549528 | 1.28E-05 | 1.92E-03 | ||

| C7S06_RS09360 | 16S ribosomal RNA | -9.91623085 | 5.20E-07 | 1.61E-04 | ||

| C7S06_RS09460 | chloride channel protein | 1.18464463 | 8.43E-04 | 0.03813733 | ||

| C7S06_RS09850 | 23S ribosomal RNA | -8.90732152 | 1.21E-05 | 1.92E-03 | ||

| C7S06_RS09865 | 16S ribosomal RNA | -9.93544646 | 5.64E-07 | 1.61E-04 | ||

| C7S06_RS10210 | pilin | -6.01251507 | 3.06E-04 | 0.017737818 | ||

| C7S06_RS10410 | tRNA-Met | -6.9457042 | 1.63E-04 | 0.012145005 | ||

| ssrS | 6S RNA | -5.31517647 | 1.04E-07 | 1.17E-04 | ||

| C7S06_RS10580 | amino acid ABC transporter permease | 2.03399688 | 1.72E-04 | 0.012145005 | ||

| C7S06_RS10585 | amino acid ABC transporter permease | 1.76436842 | 2.55E-04 | 0.015174939 | ||

| C7S06_RS10775 | hypothetical protein | -1.76534988 | 1.65E-04 | 0.012145005 | ||

| C7S06_RS11300 | 16S ribosomal RNA | -9.8672322 | 5.21E-07 | 1.61E-04 | ||

| C7S06_RS11315 | 23S ribosomal RNA | -8.94465167 | 1.41E-05 | 1.98E-03 | ||

| C7S06_RS11330 | helix-hairpin-helix domain-containing protein | -1.28389104 | 3.92E-04 | 0.022138925 | ||

| C7S06_RS12160 | tRNA-Asp | -9.4247375 | 5.70E-07 | 1.61E-04 | ||

| C7S06_RS12240 | MFS transporter | 1.82688438 | 4.79E-05 | 4.91E-03 | ||

| Condition 4 | All Control (n=3) vs All Tolerant (n=12) isolates | C7S06_RS01850 | tRNA-Ser | -6.10107845 | 1.91E-07 | 1.45E-04 |

| C7S06_RS02470 | IS1595 family transposase | -2.46234082 | 5.57E-05 | 0.015579126 | ||

| C7S06_RS02975 | tRNA-Gln | -3.88761923 | 3.93E-05 | 0.015579126 | ||

| C7S06_RS03100 | tRNA-Ser | -7.28200512 | 5.49E-09 | 1.25E-05 | ||

| C7S06_RS04945 | tRNA-Leu | -4.95129854 | 6.05E-05 | 0.015579126 | ||

| C7S06_RS04950 | tRNA-Ser | -5.37973119 | 1.22E-07 | 1.39E-04 | ||

| C7S06_RS06055 | hypothetical protein | -2.54434011 | 6.16E-05 | 0.015579126 | ||

| C7S06_RS10410 | tRNA-Met | -5.07346986 | 6.95E-05 | 0.015835072 | ||

| ssrS | 6S RNA | -3.37642264 | 5.21E-05 | 0.015579126 | ||

| C7S06_RS12165 | tRNA-Val | -3.7538874 | 3.59E-05 | 0.015579126 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).