Submitted:

21 March 2025

Posted:

24 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

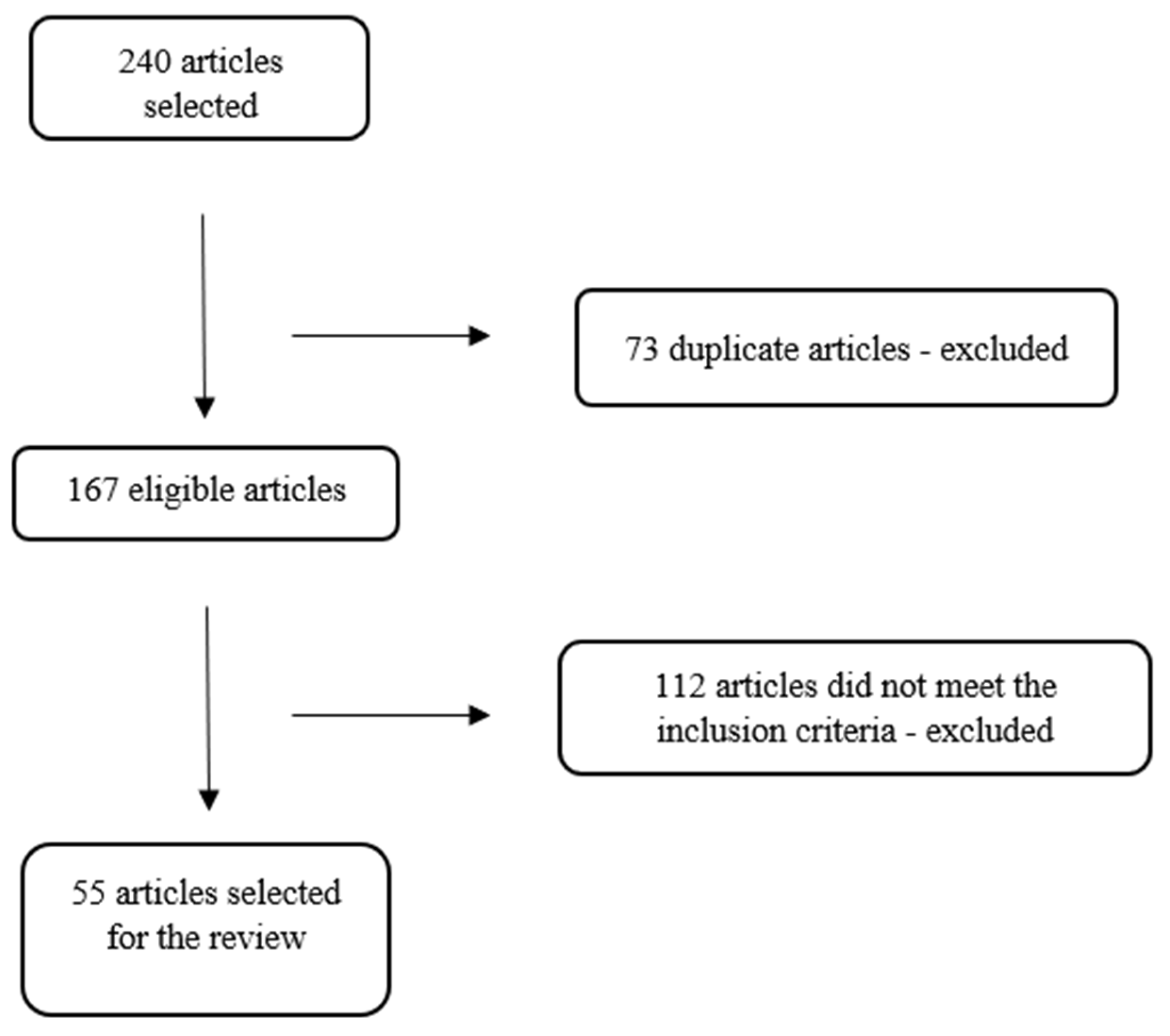

2. Materials and Methods

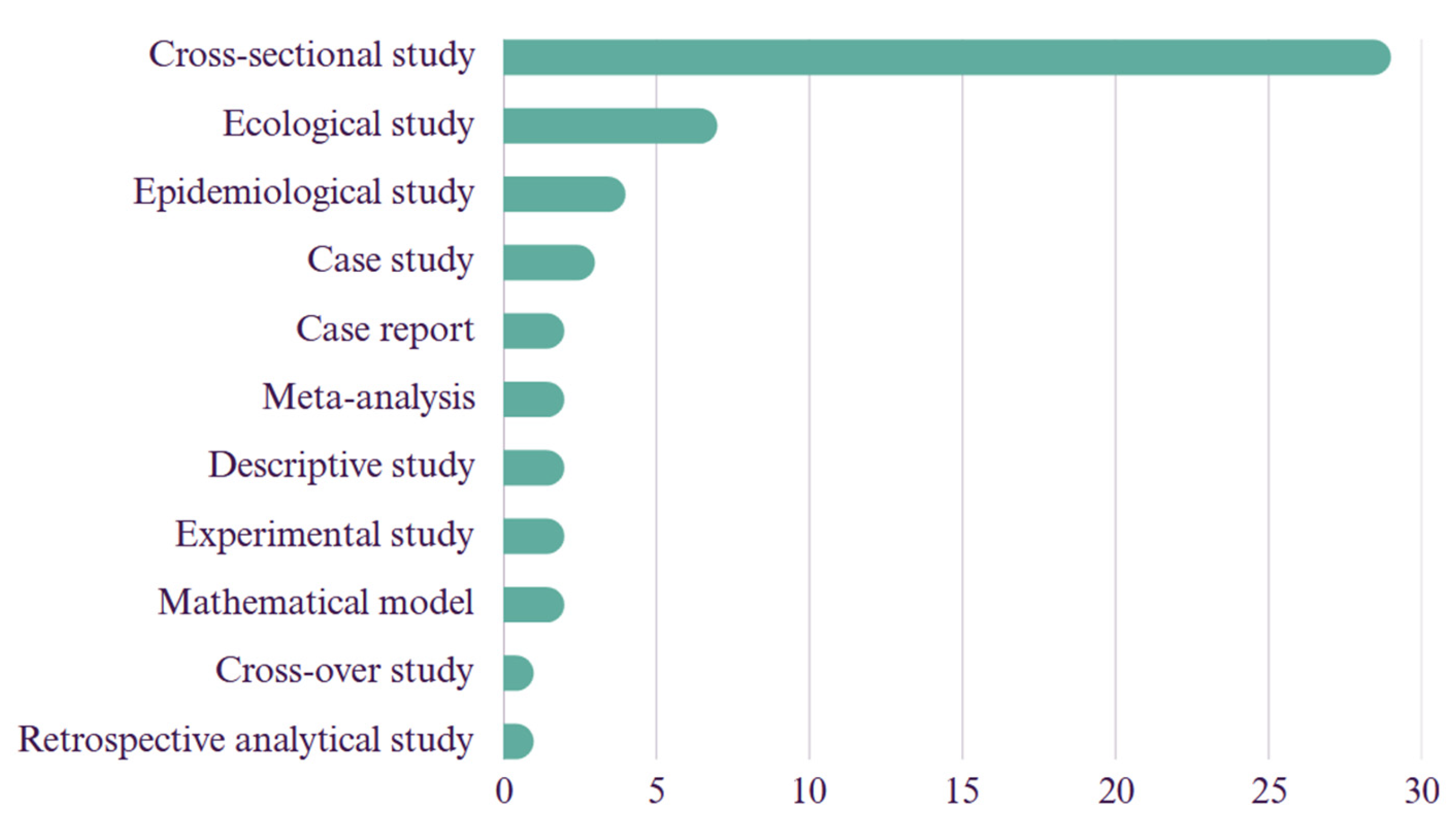

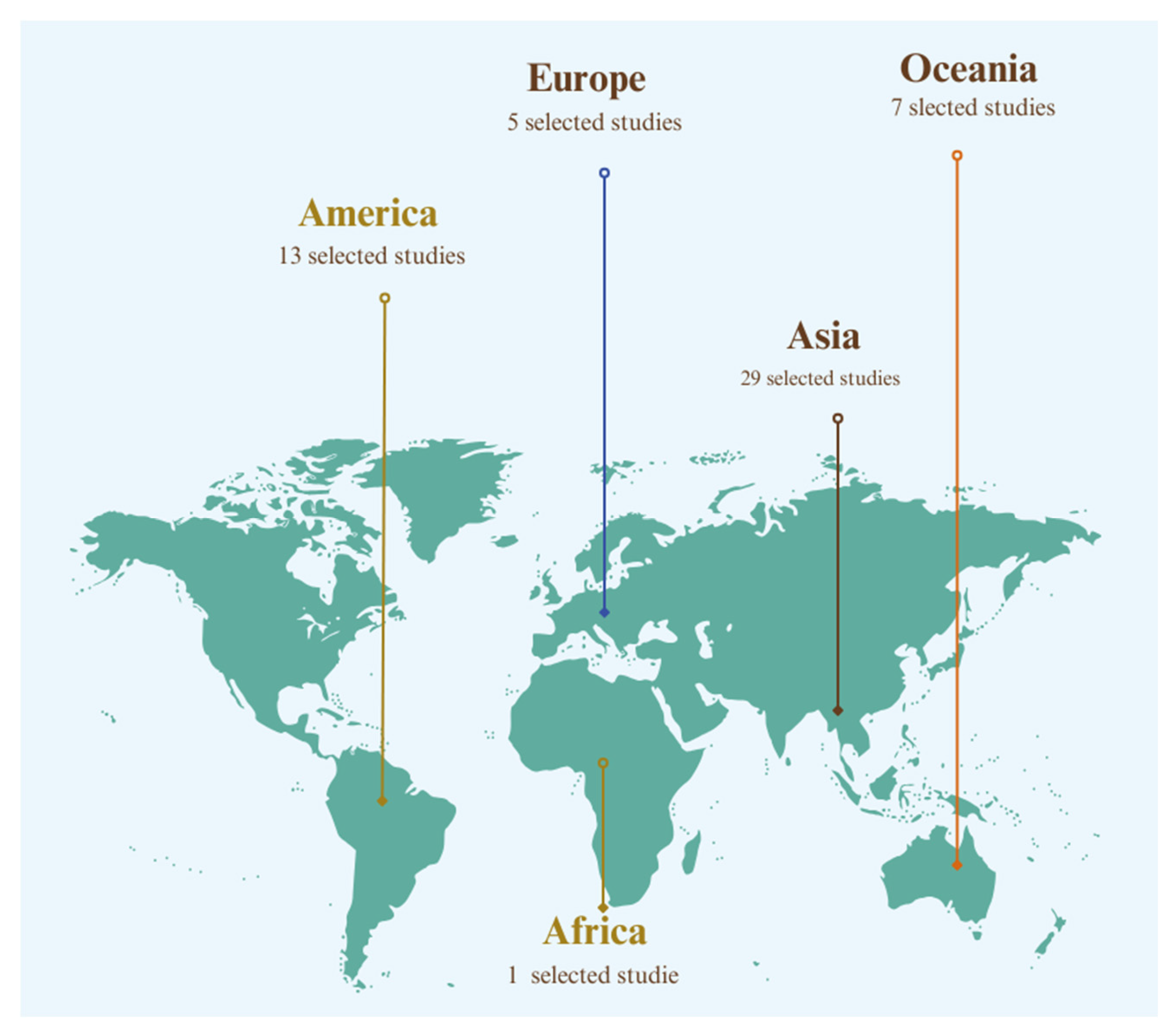

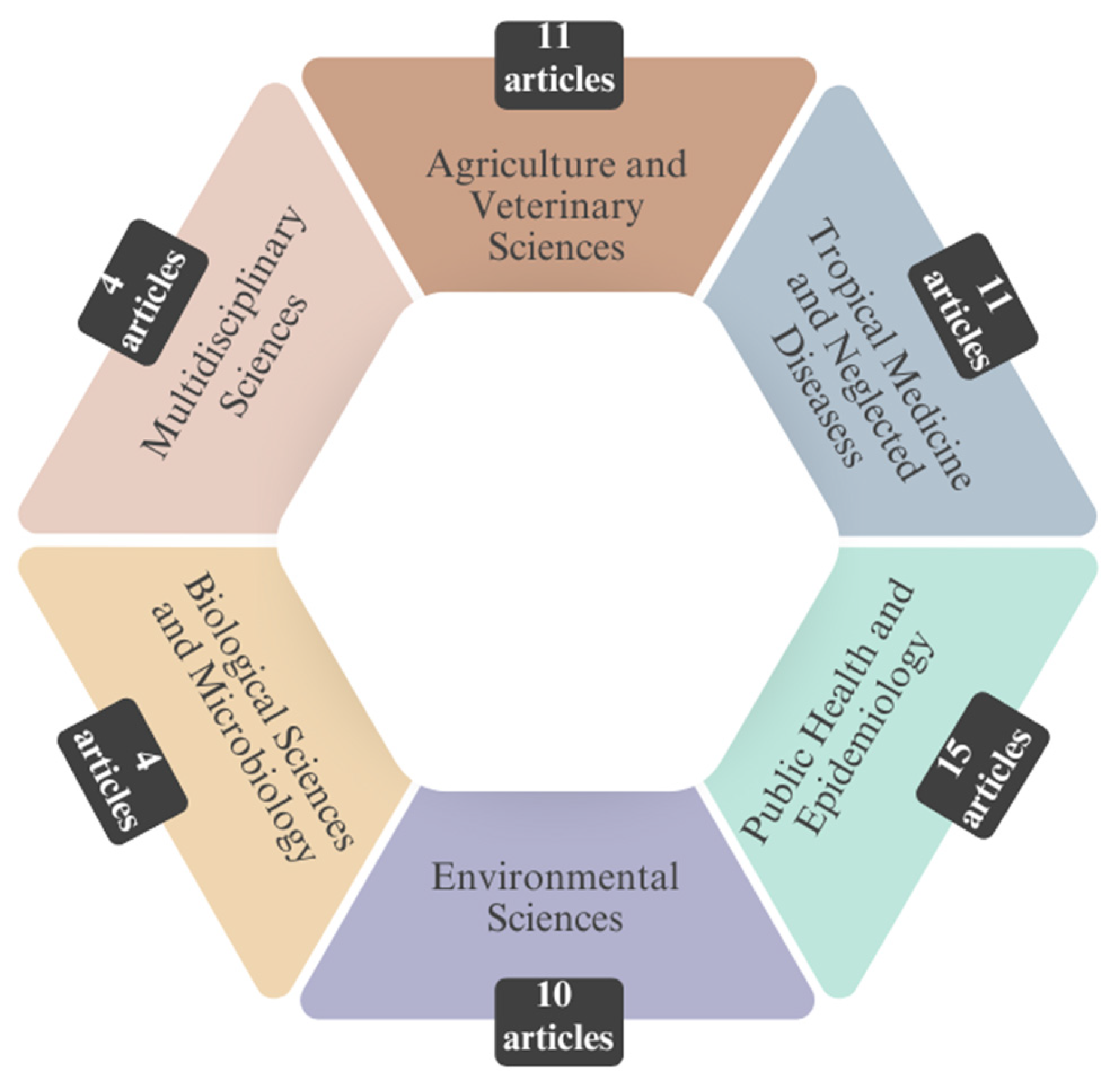

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Leptospirosis, Flooding, and Precipitation

4.2. Influence of Temperature on Leptospirosis Occurrence

4.3. Diversity of Serovars Found

4.4. Recommendations for Leptospirosis Control

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| MAT | Microscopic Agglutination Test |

References

- WHO. World Health Organization. Human leptospirosis: guidance for diagnosis, surveillance and control. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/human-leptospirosis-guidance-for-diagnosis-surveillance-and-control (accessed on 27 May 2024).

- Duarte, M.I.S.; Duarte Neto, A.N.; Pagliari, C. Doenças infecciosas: visão integrada da patologia, da clínica e dos mecanismos patogênicos; Artmed: Porto Alegre, Brasil, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Goarant, C. Leptospirosis: risk factors and management challenges in developing countries. Res Rep Trop Med 2016, 7, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenner, D.J.; Kaufmann, A.F.; Sulzer, K.R.; Steigerwalt, A.G.; Rogers, F.C.; Weyant, R.S. Further determination of DNA relatedness between serogroups and serovars in the family Leptospiraceae with a proposal for Leptospira alexanderi sp. nov. and four new Leptospira genomospecies. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 1999, 49, 839–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez, A.; Djelouadji, Z.; Lattard, V.; Kodjo, A. Overview of laboratory methods to diagnose leptospirosis and to identify and to type leptospires. Int Microbiol 2017, 20, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guernier, V.; Goarant, C.; Benschop, J.; Lau, C.L. A systematic review of human and animal leptospirosis in the Pacific Islands reveals pathogen and reservoir diversity. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2018, 12, e0006503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, H.; Nozha, C.; Hakim, K.; Abdelaziz, F. Leptospira: morphology, classification and pathogenesis. J Bacteriol Parasitol 2011, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, P.J.; Markey, B.K.; Leonard, F.C. Microbiologia veterinária essencial, 2nd ed; Artmed, 2019.

- Mcvey, S.; Kenneddy, M.; Chengappa, M.M. Microbiologia veterinária, 3rd ed; Editora Guanabara Koogan Ltd.a, 2017.

- Baharom, M.; Ahmad, N.; Hod, R.; Ja’afar, M.H.; Arsad, F.S.; Tangang, F.; Ismail, R.; Mohamed, N.; Mohd Radi, M.F.; Osman, Y. Environmental and occupational factors associated with leptospirosis: a systematic review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e23473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galan, D.I.; Roess, A.A.; Pereira, S.V.C.; Schneider, M.C. Epidemiology of human leptospirosis in urban and rural areas of Brazil, 2000–2015. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, N.; Ahmed, K. Leptospirosis in Malaysia: current status, insights, and future prospects. J Physiol Anthropol 2023, 42, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehan, S.T.; Ali, E.; Sheikh, A.; Nashwan, A.J. Urban flooding and risk of leptospirosis; Pakistan on the verge of a new disaster: a call for action. Int J Hyg Environ Health 2023, 248, 114081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.; Brodbelt, D.C.; Dobson, B.; Catchpole, B.; O’Neill, D.G.; Stevens, K.B. Spatio-temporal distribution and agroecological factors associated with canine leptospirosis in Great Britain. Prev Vet Med 2021, 193, 105407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazil. Leptospirose. Saúde de A a Z. https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/assuntos/saude-de-a-a-z/l/leptospirose (accessed 03 May 2024).

- CDC. Leptospirosis. https://www.cdc.gov/leptospirosis/infection/index.html (accessed 17 May 2024).

- CDC. Leptospirosis - Fact Sheet for Clinicians. https://www.cdc.gov/leptospirosis/pdf/fs-leptospirosis-clinicians-eng-508.pdf (accessed 04 October 2024).

- Adler, B.; Klaasen, E. Recent advances in canine leptospirosis: focus on vaccine development. Vet Med Res Rep 2015, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, W.A. Control of canine leptospirosis in Europe: time for a change? Vet Rec 2010, 167, 602–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sykes, J.E.; Hartmann, K.; Lunn, K.F.; Moore, G.E.; Stoddard, R.A.; Goldstein, R.E. 2010 ACVIM Small Animal Consensus Statement on Leptospirosis: diagnosis, epidemiology, treatment, and prevention. J Vet Intern Med 2011, 25, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, F.; Hagan, J.E.; Calcagno, J.; Kane, M.; Torgerson, P.; Martinez-Silveira, M.S.; Stein, C.; Abela-Ridder, B.; Ko, A.I. Global morbidity and mortality of leptospirosis: a systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2015, 9, e0003898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thibeaux, R.; Genthon, P.; Govan, R.; Selmaoui-Folcher, N.; Tramier, C.; Kainiu, M.; Soupé-Gilbert, M.-E.; Wijesuriya, K.; Goarant, C. Rainfall-driven resuspension of pathogenic Leptospira in a leptospirosis hotspot. Sci Total Environ 2024, 911, 168700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierque, E.; Thibeaux, R.; Girault, D.; Soupé-Gilbert, M.-E.; Goarant, C. A systematic review of Leptospira in water and soil environments. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0227055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.M.; Stull, J.W.; Moore, G.E. Potential drivers for the re-emergence of canine leptospirosis in the United States and Canada. Tropical Med 2022, 7, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. One Health. One Health. https://www.cdc.gov/one-health/about/ (accessed 24 May 2024).

- Artaxo, P. Mudanças Climáticas: caminhos para o Brasil: a construção de uma sociedade minimamente sustentável requer esforços da sociedade com colaboração entre a ciência e os formuladores de políticas públicas. Cienc Cult 2022, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójcik-Fatla, A.; Zając, V.; Wasiński, B.; Sroka, J.; Cisak, E.; Sawczyn, A.; Dutkiewicz, J. Occurrence of Leptospira DNA in water and soil samples collected in Eastern Poland. Ann Agric Environ Med 2014, 21, 730–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynwood, S.J., C., S.B.; Graham, G.C., B., B.R.; Burns, M.A., W., S.L.; Collet, T.A., M., D.B. The emergence of Leptospira borgpetersenii serovar Arborea as the dominant infecting serovar following the summer of natural disasters in Queensland, Australia 2011. Trop Biomed 2014, 31, 281–285. https://www.msptm.org/files/281_-_285_Craig_SB.pdf.

- Agampodi, S.B.; Dahanayaka, N.J.; Bandaranayaka, A.K.; Perera, M.; Priyankara, S.; Weerawansa, P.; Matthias, M.A.; Vinetz, J.M. Regional differences of leptospirosis in Sri Lanka: observations from a flood-associated outbreak in 2011. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2014, 8, e2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pimenta, C.L.R.M.; Castro, V.; Clementino, I.J.; Alves, C.J.; Fernandes, L.G.; Brasil, A.W.L.; Santos, C.S.A.B.; Azevedo, S.S. Leptospirose bovina no estado da Paraíba: prevalência e fatores de risco associados à ocorrência de propriedades positivas. Pesq Vet Bras 2014, 34, 332–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, R.M.; Cruz, O.G.; Parreira, V.G.; Mazoto, M.L.; Vieira, J.D.; Asmus, C.I.R.F. Análise temporal da relação entre leptospirose e ocorrência de inundações por chuvas no município do Rio de Janeiro, Brasil, 2007-2012. Cien Saude Colet 2014, 19, 3683–3692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gracie, R.; Barcellos, C.; Magalhães, M.; Souza-Santos, R.; Barrocas, P. Geographical scale effects on the analysis of leptospirosis determinants. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2014, 11, 10366–10383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwanpakdee, S.; Kaewkungwal, J.; White, L.J.; Asensio, N.; Ratanakorn, P.; Singhasivanon, P.; Day, N.P.J.; Pan-Ngum, W. Spatio-temporal patterns of leptospirosis in Thailand: is flooding a risk factor? Epidemiol Infect 2015, 143, 2106–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matono, T.; Kutsuna, S.; Koizumi, N.; Fujiya, Y.; Takeshita, N.; Hayakawa, K.; Kanagawa, S.; Kato, Y.; Ohmagari, N. Imported flood-related leptospirosis from Palau: awareness of risk factors leads to early treatment. J Travel Med 2015, 22, 422–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, C.L.; Watson, C.H.; Lowry, J.H.; David, M.C.; Craig, S.B.; Wynwood, S.J.; Kama, M.; Nilles, E.J. Human leptospirosis infection in Fiji: an eco-epidemiological approach to identifying risk factors and environmental drivers for transmission. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2016, 10, e0004405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohail, M.L.; Khan, M.S.; Avais, M.; Zahoor, M.Y.; Ijaz, M.; Ullah, A.; Fatima, Z.; Naseer, O.; Khattak, I.; Ali, S. Seroprevalence of Leptospira spp. in horses of distinct climatic regions of Punjab, Pakistan. J Equine Vet Sci 2016, 44, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gloriani, N.G., V., S.Y.A.M. Post-flooding surveillance of leptospirosis after the onslaught of typhoons Nesat, Nalgae and Washi in the Philippines. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2016, 47, 774–786.

- Azócar-Aedo, L.; Monti, G. Meta-analyses of factors associated with leptospirosis in domestic dogs. Zoonoses Public Health 2016, 63, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledien, J.; Sorn, S.; Hem, S.; Huy, R.; Buchy, P.; Tarantola, A.; Cappelle, J. Assessing the performance of remotely-sensed flooding indicators and their potential contribution to early warning for leptospirosis in Cambodia. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0181044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayati, K.S., S.N., S.I.; Salmiah, M.S., E.M.A.; Khin T.D. Hot-spot and cluster analysis on legal and illegal dumping sites as the contributors of leptospirosis in a flood hazard area in Pahang, Malaysia. Asian J Agric Biol 2018, 78–82.

- Syamsuar; Daud, A.; Maria, I.L.; Hatta, Muh.; Widyastuti, D. Identification of serovar leptospirosis in flood-prone areas Wajo district. Indian J Public Health Res Dev 2018, 9, 325. [CrossRef]

- Ijaz, M.; Abbas, S.N.; Farooqi, S.H.; Aqib, A.I.; Anwar, G.A.; Rehman, A.; Ali, M.M.; Mehmood, K.; Khan, A. Sero-epidemiology and hemato-biochemical study of bovine leptospirosis in flood affected zone of Pakistan. Acta Trop 2018, 177, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Supe, A.; Khetarpal, M.; Naik, S.; Keskar, P. Leptospirosis following heavy rains in 2017 in Mumbai: report of large-scale community chemoprophylaxis. Natl Med J India 2018, 31, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chadsuthi, S.; Chalvet-Monfray, K.; Wiratsudakul, A.; Suwancharoen, D.; Cappelle, J. A remotely sensed flooding indicator associated with cattle and buffalo leptospirosis cases in Thailand 2011–2013. BMC Infect Dis 2018, 18, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitale, M.; Agnello, S.; Chetta, M.; Amato, B.; Vitale, G.; Bella, C.D.; Vicari, D.; Presti, V.D.M.L. Human leptospirosis cases in Palermo Italy. The role of rodents and climate. J Infect Public Health 2018, 11, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsushita, N.; Ng, C.F.S.; Kim, Y.; Suzuki, M.; Saito, N.; Ariyoshi, K.; Salva, E.P.; Dimaano, E.M.; Villarama, J.B.; Go, W.S.; Hashizume, M. The non-linear and lagged short-term relationship between rainfall and leptospirosis and the intermediate role of floods in the Philippines. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2018, 12, e0006331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radi, M.F.; Hashim, J.H.; Jaafar, M.H.; Hod, R.; Ahmad, N.; Mohammed Nawi, A.; Baloch, G.M.; Ismail, R.; Farakhin Ayub, N.I. Leptospirosis outbreak after the 2014 major flooding event in Kelantan, Malaysia: a spatial-temporal analysis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2018, 98, 1281–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayfield, H.J.; Lowry, J.H.; Watson, C.H.; Kama, M.; Nilles, E.J.; Lau, C.L. Use of geographically weighted logistic regression to quantify spatial variation in the environmental and sociodemographic drivers of leptospirosis in Fiji: a modelling study. Lancet Planet Health 2018, 2, e223–e232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohail, M.L.; Khan, M.S.; Ijaz, M.; Naseer, O.; Fatima, Z.; Ahmad, A.S.; Ahmad, W. Seroprevalence and risk factor analysis of human leptospirosis in distinct climatic regions of Pakistan. Acta Trop 2018, 181, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togami, E.; Kama, M.; Goarant, C.; Craig, S.B.; Lau, C.; Ritter, J.M.; Imrie, A.; Ko, A.I.; Nilles, E.J. A Large leptospirosis outbreak following successive severe floods in Fiji, 2012. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2018, 99, 849–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widiyanti, D.; Djannatun, T.; Astuti, I.I.P.; Maharsi, E.D. Leptospira detection in flood-prone environment of Jakarta, Indonesia. Zoonoses Public Health 2019, 66, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, G.; Li, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, B.; Jiang, B.; Li, D.; Xing, W.; Liu, Q.; Liu, X.; Hou, H. A time-trend ecological study for identifying flood-sensitive infectious diseases in Guangxi, China from 2005 to 2012. Environ Res 2019, 176, 108577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumalapao, D.P.; Del Rosario, B.M.; Suñga, L.L.; Walthern, C.; Gloriani, N. Frequency of typhoon occurrence accounts for the poisson distribution of human leptospirosis cases across the different geographic regions in the Philippines. Asian Pac J Trop Med 2019, 12, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naing, C.; Reid, S.A.; Aye, S.N.; Htet, N.H.; Ambu, S. Risk factors for human leptospirosis following flooding: a meta-analysis of observational studies. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0217643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López, M.S.; Müller, G.V.; Lovino, M.A.; Gómez, A.A.; Sione, W.F.; Aragonés Pomares, L. Spatio-temporal analysis of leptospirosis incidence and its relationship with hydroclimatic indicators in northeastern Argentina. Sci Total Environ 2019, 694, 133651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Péres, E.W.; Russo, A.; Nunes, B. The association between hydro-meteorological events and leptospirosis hospitalizations in Santa Catarina, Brazil. Water 2019, 11, 1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, S.H.; Ismail, R.; Lau, S.F.; Megat Abdul Rani, P.A.; Mohd Mohidin, T.B.; Daud, F.; Bahaman, A.R.; Khairani-Bejo, S.; Radzi, R.; Khor, K.H. Risk factors and prediction of leptospiral seropositivity among dogs and dog handlers in Malaysia. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019, 16, 1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamond, C.; Silveira, C.S.; Buroni, F.; Suanes, A.; Nieves, C.; Salaberry, X.; Aráoz, V.; Costa, R.A.; Rivero, R.; Giannitti, F.; Zarantonelli, L. Leptospira interrogans serogroup Pomona serovar Kennewicki infection in two sheep flocks with acute leptospirosis in Uruguay. Transbound Emerg Dis 2019, 66, 1186–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagojević, J.; Šekler, M.; Rajičić, M.; Pejić, B.; Budinski, I.; Jovanović, V.M.; Adnađević, T.; Vidanović, D.; Matović, K.; Vujošević, M. The prevalence of pathogenic forms of Leptospira in natural populations of small wild mammals in Serbia. Acta Vet Hung 2019, 67, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chery, G.; Francis, L.; Hunte, S.-A.; Leon, P. Epidemiology of human leptospirosis in Saint Lucia, 2010–2017. Rev Panam Salud Publica 2020, 44, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baki, N.N.A.; Ali, M.R.M.; Rahman, E.N.S.E.A.; Yusof, N.Y.; Ismail, N.; Chan, Y.Y. Detection and distribution of putative pathogenicity-associated genes among serologically important Leptospira strains and post-flood environmental isolates in Malaysia. Malays J Microbiol 2020, 16, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.E.P.; Chiaravalloti Neto, F.; Conceição, G.M.D.S. Leptospirosis and its spatial and temporal relations with natural disasters in six municipalities of Santa Catarina, Brazil, from 2000 to 2016. Geospat Health 2020, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracie, R.; Xavier, D.R.; Medronho, R. Inundações e leptospirose nos municípios brasileiros no período de 2003 a 2013: utilização de técnicas de mineração de dados. Cad Saude Publica 2021, 37, e00100119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syakbanah, N.L.; Fuad, A. Human leptospirosis outbreak: a year after the ‘Cempaka’ tropical cyclone. Jurnal Kesehatan Lingkungan 2021, 13, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadsuthi, S.; Chalvet-Monfray, K.; Wiratsudakul, A.; Modchang, C. The effects of flooding and weather conditions on leptospirosis transmission in Thailand. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Khairani Bejo, S.; Zakaria, Z.; Hassan, L.; Azri Roslan, M. Seroprevalence and distribution of leptospiral serovars in livestock (cattle, goats, and sheep) in flood-prone Kelantan, Malaysia. J Vet Res 2020, 65, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenum, I.; Medina, M.C.; Garner, E.; Pieper, K.J.; Blair, M.F.; Milligan, E.; Pruden, A.; Ramirez-Toro, G.; Rhoads, W.J. Source-to-tap assessment of microbiological water quality in small rural drinking water systems in Puerto Rico six months after hurricane Maria. Environ Sci Technol 2021, 55, 3775–3785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mgode, G.F.; Mhamphi, G.G.; Massawe, A.W.; Machang’u, R.S. Leptospira seropositivity in humans, livestock and wild animals in a semi-arid area of Tanzania. Pathog 2021, 10, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagihara, Y.; Villanueva, S.Y.A.M.; Nomura, N.; Ohno, M.; Sekiya, T.; Handabile, C.; Shingai, M.; Higashi, H.; Yoshida, S.; Masuzawa, T.; Gloriani, N.G.; Saito, M.; Kida, H. Leptospira is an environmental bacterium that grows in waterlogged soil. Microbiol Spectr 2022, 10, e02157–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.E.P.; Latorre, M.D.R.D.D.O.; Chiaravalloti Neto, F.; Conceição, G.M.D.S. Tendência temporal da leptospirose e sua associação com variáveis climáticas e ambientais em Santa Catarina, Brasil. Cien Saude Colet 2022, 27, 849–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taunton, C.; Hayek, C.E.; Field, E.; Rubenach, S.; Esmonde, J.; Smith, S.; Preston-Thomas, A. Undetected serovars: leptospirosis cases in the Cairns region during the 2021 wet season. Commun Dis Intell 2022, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardoni Marteli, A.; Guasselli, L.A.; Diament, D.; Wink, G.O.; Vasconcelos, V.V. Spatio-temporal analysis of leptospirosis in Brazil and its relationship with flooding. Geospat Health 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.S.; Bejo, S.K.; Zakaria, Z.; Hassan, L.; Roslan, M.A. Detection of Leptospira wolffii in water and soil on livestock farms in Kelantan after a massive flood. Sains Malays 2023, 52, 1383–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marić, J.S.; Nedić, D.; Vejnović, B.; Velić, L.; Obrenović, S. Seroprevalence of serovars of pathogenic Leptospira in dogs and red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) from Bosnia and Herzegovina. Acta Vet 2023, 73, 389–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaramu, V.; Zulkafli, Z.; De Stercke, S.; Buytaert, W.; Rahmat, F.; Abdul Rahman, R.Z.; Ishak, A.J.; Tahir, W.; Ab Rahman, J.; Mohd Fuzi, N.M.H. Leptospirosis modelling using hydrometeorological indices and random forest machine learning. Int J Biometeorol 2023, 67, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udayar, S.; Chengalarayappa, N.; Madeshan, A.; Shivanna, M.; Marella, K. Clinico epidemiological study of human leptospirosis in Hilly area of South India - a population-based case control study. Indian J Community Med 2023, 48, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn-Hausner, N.; Kmetiuk, L.B.; Biondo, A.W. One Health approach to leptospirosis: human–dog seroprevalence associated to socioeconomic and environmental risk factors in Brazil over a 20-year period (2001–2020). Tropical Med 2023, 8, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Rodríguez, V.; Castro-Cordero, A.; Calderón-Rangel, A.; Martínez-Ibarra, E.; Yasnot, M.; Agudelo-Flórez, P.; Monroy, F.P. Acute human leptospirosis in a caribbean region of Colombia: from classic to emerging risk factors. Zoonoses Public Health 2024, 71, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifejube, O.J.; Kuriakose, S.L.; Anish, T.S.; Van Westen, C.; Blanford, J.I. Analysing the outbreaks of leptospirosis after floods in Kerala, India. Int J Health Geogr 2024, 23, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, T.M.V.; Balassiano, I.T.; Silva, T.D.S.M.D.; Nogueira, J.M.D.R. Leptospirose: características da enfermidade em humanos e principais técnicas de diagnóstico laboratorial. RBAC 2022, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharti, A.R.; Nally, J.E.; Ricaldi, J.N.; Matthias, M.A.; Diaz, M.M.; Lovett, M.A.; Levett, P.N.; Gilman, R.H.; Willig, M.R.; Gotuzzo, E.; Vinetz, J.M. Leptospirosis: a zoonotic disease of global importance. Lancet Infect Dis 2003, 3, 757–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plank, R.; Dean, D. Overview of the epidemiology, microbiology, and pathogenesis of Leptospira spp. in humans. Microbes Infect 2000, 2, 1265–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerqueira, G.M.; Picardeau, M. A century of Leptospira strain typing. Infect Genet Evol 2009, 9, 760–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haake, D.A.; Levett, P.N. Leptospirosis in humans. In Leptospira and leptospirosis. Current topics in microbiology and immunology; Adler, B., Ed.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2015; Volume 387, pp. 65–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.E.R.; Wiggans, K.T.; Jablonski Wennogle, S.A.; Curtis, K.; Chandrashekar, R.; Lappin, M.R. Vaccine-associated Leptospira antibodies in client-owned dogs. J Vet Intern Med 2014, 28, 789–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felix, C.R.; Siedler, B.S.; Barbosa, L.N.; Timm, G.R.; McFadden, J.; McBride, A.J.A. An overview of human leptospirosis vaccine design and future perspectives. Expert Opin Drug Discov 2020, 15, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors (year) | Database | Country of Study | Journal | Leptospirosis X Climate Change X Humans/Animals | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wójcik-Fatla et al. [28] | Scopus | Poland | Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine | Occurrence of pathogenic Leptospira in water and soil samples. |

| 2 | Wynwood et al. [29] | Scopus | Australia | Tropical Biomedicine | Humans infected with serovar Arborea after flooding. |

| 3 | Agampodi et al. [30] | Scopus | Sri Lanka | PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases | Disease outbreak in humans in a dry region. |

| 4 | Pimenta et al. [31] | Scielo | Brazil | Pesquisa Veterinária Brasileira | Serovar prevalence in cattle. |

| 5 | Guimarães et al. [32] | Pubmed | Brazil | Ciência & Saúde Coletiva | Positive effect of precipitation on transmission. |

| 6 | Gracie et al. [33] | Pubmed | Brazil | International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health | Environmental and socioeconomic factors (densely urbanized areas, flood-prone regions, and altitude) in disease transmission. |

| 7 | Suwanpakdee et al. [34] | Pubmed | Thailand | Epidemiology and Infection | Influence of flooding on human disease. |

| 8 | Matono et al. [35] | Pubmed | Japan | Journal of Travel Medicine | Report of two positive leptospirosis cases after traveling to a flooded area. |

| 9 | Lau et al. [36] | Pubmed | Fiji | PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases | Serovars involved and environmental factors. |

| 10 | Sohail et al. [37] | Scopus | Pakistan | Journal of Equine Veterinary Science | Seroprevalence and risk factors in equines. |

| 11 | Gloriani et al. [38] | Scopus | Philippines | Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health | Human seroprevalence of the disease after floods. |

| 12 | Azócar-Aedo & Monti [39] | Pubmed | Chile | Zoonoses and Public Health | Factors associated with canine leptospirosis. |

| 13 | Ledien et al. [40] | Pubmed | Cambodia | PloS One | Development of a flood indicator test. |

| 14 | Hayati et al. [41] | Scopus | Malaysia | Asian Journal of Agriculture and Biology | Environmental factors linked to leptospirosis risk in humans. |

| 15 | Syamsuar et al. [42] | Scopus | India | Indian Journal of Public Health Research and Development | Human seroprevalence in flood-prone areas. |

| 16 | Ijaz et al. [43] | Scopus | Pakistan | Acta Tropica | Seroprevalence and risk factors in cattle. |

| 17 | Supe et al. [44] | Pubmed | India | The National Medical Journal of India | Use of chemoprophylaxis for leptospirosis in humans in flooded areas. |

| 18 | Chadsuthi et al. [45] | Scopus | Thailand | BMC Infectious Diseases | Environmental factors in leptospirosis transmission in cattle and buffaloes. |

| 19 | Vitale et al. [46] | Pubmed | Italy | Journal of Infection and Public Health | Report of two symptomatic human leptospirosis cases. |

| 20 | Matsushita et al. [47] | Pubmed | Philippines | PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases | Association of rainfall and disease occurrence in humans. |

| 21 | Radi et al. [48] | Pubmed | Malaysia | The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene | Environmental factors such as floods and water bodies in disease distribution in humans. |

| 22 | Mayfield et al. [49] | Pubmed | Fiji | The Lancet Planetary Health | Use of geographically weighted logistic regression for human epidemiology. |

| 23 | Sohail et al. [50] | Pubmed | Pakistan | Acta Tropica | Seroprevalence and risk factors in humans. |

| 24 | Togami et al. [51] | Pubmed | Fiji | The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene | Occurrence of the disease in humans and factors such as floods. |

| 25 | Widiyanti et al. [52] | Scopus | Indonesia | Zoonoses and Public Health | Presence of bacteria in the environment, especially during floods. |

| 26 | Ding et al. [53] | Scopus | China | Environmental Research | Influence of floods on human cases. |

| 27 | Sumalapao et al. [54] | Scopus | Philippines | Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine | Relationship between typhoons and increased disease occurrence in humans. |

| 28 | Naing et al. [55] | Pubmed | Australia | PloS One | Significant association between floods and increased risk of human leptospirosis. |

| 29 | López et al. [56] | Scopus | Argentina | Science of the Total Environment | Hydro-climatic factors in disease occurrence in humans. |

| 30 | Péres et al. [57] | Scopus | Brazil | Water | Influence of extreme hydrometeorological events and increased human hospitalization rates due to leptospirosis in Santa Catarina state. |

| 31 | Goh et al. [58] | Pubmed | Malaysia | International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health | Rat contact and shared areas as risk factors for shelter dogs and their handlers. |

| 32 | Hamond et al. [59] | Pubmed | Uruguay | Transboundary and Emerging Diseases | Report of ovine leptospirosis. |

| 33 | Blagojevic et al. [60] | Pubmed | Serbia | Acta Veterinaria Hungarica | Detection of leptospirosis in wild mammals. |

| 34 | Chery et al. [61] | Scopus | Saint Lucia | Pan American Journal of Public Health | Human epidemiology and correlation with precipitation and temperature. |

| 35 | Baki et al. [62] | Scopus | Malaysia | Malaysian Journal of Microbiology | Detection of pathogenicity genes in environmental samples. |

| 36 | Silva et al. [63] | Pubmed | Brazil | Geospatial Health | Identifying human disease clusters in municipalities after natural disasters. |

| 37 | Gracie et al. [64] | Pubmed | Brazil | Cadernos de Saúde Pública | Higher risk of human leptospirosis in municipalities that declared floods. |

| 38 | Syakbanah & Fuad [65] | Scopus | Java | Jurnal Kesehatan Lingkungan | Human disease cases after a cyclone and flooding. |

| 39 | Chadsuthi et al. [66] | Pubmed | Thailand | Scientific Reports | Mathematical model to evaluate cases in humans, animals, and the environment. |

| 40 | Rahman et al. [67] | Pubmed | Malaysia | Journal of Veterinary Research | Disease prevalence in cattle, goats, and sheep after flooding. |

| 41 | Keenum et al. [68] | Pubmed | Puerto Rico | Environmental Science & Technology | Presence of bacteria in water systems after flooding. |

| 42 | Mgode et al. [69] | Pubmed | Tanzania | Pathogens | Disease prevalence in cattle. |

| 43 | Taylor et al. [14] | Pubmed | Great Britain | Preventive Veterinary Medicine | Disease prevalence in dogs. |

| 44 | Yanagihara et al. [70] | Scopus | Japan | Microbiology Spectrum | Presence of Leptospira in the environment. |

| 45 | Silva et al. [71] | Scielo | Brazil | Ciência e Saúde Coletiva | Climatic and environmental factors in human leptospirosis occurrence. |

| 46 | Taunton et al. [72] | Pubmed | Australia | Communicable Diseases Intelligence | Occurrence of human leptospirosis after heavy rains and flooding. |

| 47 | Marteli et al. [73] | Pubmed | Brazil | Geospatial Health | Flood-prone areas and human leptospirosis cases. |

| 48 | Rahman et al. [74] | Scopus | Malaysia | Sains Malaysiana | Presence of Leptospira in cattle farm soils after flooding. |

| 49 | Maric et al. [75] | Scopus | Bosnia and Herzegovina | Acta Veterinaria | Seroprevalence of leptospirosis in dogs and foxes after flooding. |

| 50 | Jayaramu et al. [76] | Pubmed | Malaysia | International Journal of Biometeorology | Hydrometeorological risk factors and human leptospirosis. |

| 51 | Udayar et al. [77] | Pubmed | India | Indian Journal of Community Medicine | Environmental risk factors associated with human leptospirosis. |

| 52 | Sohn-Hausner et al. [78] | Pubmed | Brazil | Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease | Risk factors such as flooding and serovars in dogs and their owners. |

| 53 | Thibeaux et al. [22] | Scopus | New Caledonia | Science of the Total Environment | Presence of Leptospira in soil samples after floods. |

| 54 | Rodríguez-Rodríguez et al. [79] | Pubmed | Malaysia | Zoonoses and Public Health | Risk factors for leptospirosis occurrence in humans. |

| 55 | Ifejube et al. [80] | Pubmed | India | International Journal of Health Geographics | Positive relationship between flooding and human cases. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).