Submitted:

23 March 2025

Posted:

24 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Role of Ports in the Decarbonization of Maritime Transport

2.1. Key Regulations Driving Change

- International Maritime Organization (IMO): The IMO’s Initial Strategy for reducing GHG Emissions from Ships aims to cut emissions by at least 50% by 2050 compared to 2008 levels. The introduction of the Energy Efficiency Existing Ship Index (EEXI) and Carbon Intensity Indicator (CII) regulations in 2023 enforces compliance with stricter efficiency standards [1].

- European Green Deal: The European Union (EU) has adopted the Fit for 55 legislative packages, including the FuelEU Maritime Initiative. This initiative mandates a gradual shift towards alternative fuels and sets specific reduction targets for GHG emissions from shipping by 2030 and 2050 [5].

- Alternative Fuels Infrastructure Regulation (AFIR): The EU has proposed new infrastructure requirements for alternative fuel supply, ensuring ports are equipped with refuelling facilities for sustainable fuels like hydrogen, methanol, ammonia, and bio-LNG [13], among others.

2.2. Role of Ports in the Energy Transition and Technological Developments

2.3. Policy and Market Evolution

2.4. Integration of Renewable Energy in Ports

3. Maritime-Port Operations That Are Likely to Be Carried Out with a More Sustainable Energy Model

| Level | Name of Activity |

| 1 | Business Oriented Activities (Managed by Concessionaires) |

| 1.1. | Passenger Terminals: |

| 1.2. | Cargo Terminals: |

| 1.2.1 | Ro-Ro and Vehicle Terminals |

| 1.2.2. | Container Terminals |

| 1.2.3. | Multipurpose Terminals |

| 1.2.4. | Bulk Terminals: |

| 1.2.5. | Petroleum and Chemical Terminals (Dangerous cargo) |

| 1.3. | Private Services: |

| 1.3.1. | Storage of Cargo |

| 1.3.2. | Repair of Ships and Shipyards |

| 1.3.3 | Supply to Ships |

| 1.3.4. | Nautical Services |

| 1.3.5. | Hospitality Services |

| 2. | Services Oriented Activities (Managed by the Port Authority): |

| 2.1. | Infrastructure |

| 2.1.1. | Maintenance and Construction / Road Lighting |

| 2.2. | Port Services: |

| 2.2.1. | Pilots |

| 2.2.2. | Tugs |

| 2.2.3. | Mooring services |

| 2.3. | Administrative and Community Services: |

| 3. | Other activities. |

4. Met-Ocean Strategy for Assessing the Feasibility of Marine Renewable Energy Near Ports

4.1. Introduction

4.1. Selection of the Most Suitable Agitation Model

4.2. Bathymetric, Port Contour / Typologies, Instrumental Data and Forcing Used

4.3. Selection of Coastal/Port Contour Reflection Coefficients

4.4. Design of the MSP Numerical Grid

4.5. Model Runs and General Results

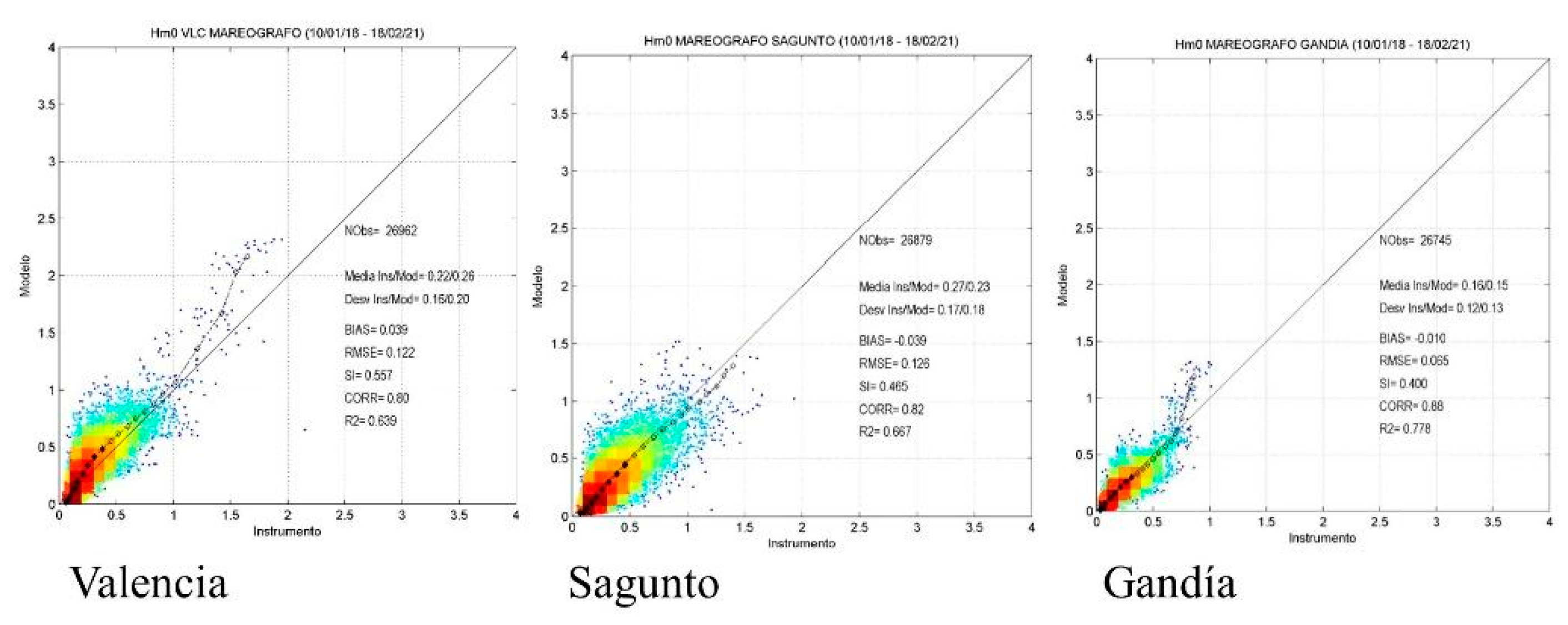

4.6. Pre-Operational Validation and System Calibration

4.7. Post-Processing

- ρ is the density of seawater, ρ = 1,025 kg/m³

- is the acceleration due to gravity, g = 9.81 m/s²

- S(ω,θ) is the directional energy spectrum representing the energy density (energy per unit area) assigned to each frequency ω and direction θ of the sea state.

- Cg(ω,z) is the group celerity representing the propagation velocity of wave energy, calculated by:

- is the wave celerity, c = L/T = ω/k

- ω is the angular frequency of the wave, ω = 2π/T

- is the wave number, k = 2π/L

- is the wave period

- is the wavelength

- is the water depth (positive distance from the surface to the seabed)

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

5.1. Integration of Marine Renewable Energy in Port Operations

5.2. The Role of Predictive Modeling in Enhancing Energy Feasibility Assessments

5.3. Implications for Port Sustainability and Energy Sovereignty

5.4. Future Directions and Research Opportunities

5.5. Final Considerations

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The calculation of greenhouse gas emissions is divided into three scopes: Scope 1: direct emissions, Scope 2: energy-related indirect emissions, and Scope 3: indirect emissions from other activities. |

References

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). (2022). Review of Maritime Transport 2022. https://unctad.org, accessed on 26th January 2025.

- International Maritime Organization (IMO). (2020). Fourth IMO GHG Study 2020. https://www.imo.org, accessed on 26th January 2025.

- European Community Shipowners’ Associations (ECSA). (2021). Decarbonization Pathways for Maritime Transport. https://www.ecsa.eu, accessed on 26th January 2025.

- Port of Rotterdam. (2023). Shore Power Projects for Sustainable Shipping. https://www.portofrotterdam.com, accessed on 26th January 2025.

- European Commission. (2021). Fit for 55: Delivering the EU’s 2030 Climate Target on the Way to Climate Neutrality. https://ec.europa.eu, accessed on 26th January 2025.

- https://www.offshorewind.biz/2023/07/07/port-of-esbjerg-lines-up-eur-780-million-investment-in-offshore-wind-turbine-production-facilities. Accessed on 17th March 2025.

- Pérez-Collazo, C., Greaves, D., Iglesias, G. (2015). A review of combined wave and off-shore wind energy, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, Volume 42, Pages 141-153, ISSN 1364-0321. [CrossRef]

- Linfeng, L. et al. (2024), Optimal planning of renewable energy infrastructure for ports under multiple design scenarios considering system constraints and growing transport demand, Journal of Cleaner Production, Volume 477, ISSN 0959-6526. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, G. (2020). Offshore Wind Resource Assessment Techniques. https://www.dnv.com, accessed on 26th January 2025.

- World Meteorological Organization (WMO). (2022). Advances in Numerical Weather Prediction for Ports. https://public.wmo.int. Accessed on 26th January 2025.

- DNV. (2022). Maritime Forecast to 2050: Energy Transition Outlook. https://www.dnv.com, accessed on 28th January 2025.

- European Commission. (2022). Extension of the EU Emissions Trading System to Maritime Transport. https://ec.europa.eu. Accessed on 28th January 2025.

- European Parliament. (2023). Alternative Fuels Infrastructure Regulation (AFIR). https://www.europarl.europa.eu. Accessed on 28th January 2025.

- Port of Rotterdam. (2023). Hydrogen and LNG Bunkering Facilities. https://www.portofrotterdam.com. Accessed on 28th January 2025.

- European Sea Ports Organisation. (2022). Sustainable Ports in Europe: Shore-Side Electricity. https://www.espo.be. Accessed on 28th January 2025.

- Global Maritime Forum. (2022). The Development of Green Shipping Corridors. https://www.globalmaritimeforum.org. Accessed on 28th January 2025.

- WindEurope. (2023). Floating Offshore Wind Farms: Opportunities for Ports. https://windeurope.org. Accessed on 28th January 2025.

- Cascajo, R.; García, E.; Quiles, E.; Correcher, A.; Morant, F. (2019). Integration of Marine Wave Energy Converters into Seaports: A Case Study in the Port of Valencia. Energies, 12, 787. [CrossRef]

- Informe de emisiones de gases de efecto invernadero del puerto de valencia. Año 2016. https://www.valenciaport.com/wp-content/uploads/Memoria-Verificaci%C3%B3n-GEI-2016.pdf. Accessed on 3rd March 2025.

- Cascajo, R. Cascajo, R., Molina, R., & Pérez-Rojas, L. (2022). Sectoral Analysis of the Fundamental Criteria for the Evaluation of the Viability of Wave Energy Generation Facilities in Ports—Application of the Delphi Methodology. Energies, 15(7), 2667. [CrossRef]

- Puertos del Estado. (n.d.). Red de boyas: Información meteorológica y oceanográfica. https://www.puertos.es, accessed on 28th January 2025.

- G. Diaz-Hernandez, B. Rodríguez Fernández, E. Romano-Moreno et al., An improved model for fast and reliable harbour wave agitation assessment. Coastal Engineering, Volume 170, 2021, 104011, ISSN 0378-3839. [CrossRef]

- Vílchez, M., Clavero, M., &Losada, M. A. (2015). “Operational behaviour of a 2D breakwater: Synthesis and design performance curves”. Report EM 200. Instituto Interuniversitario de Investigación del Sistema Tierra en Andalucía. Sede CEAMA. Universidad de Granada.

- Vílchez, M., Clavero, M., & Losada, M. A. (2016). “Hydraulic performance of different non-overtopped breakwaters types under 2D wave attack”, Coastal Engineering, Volume 107, January 2016, Pages 34-52.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).