1. Introduction

Reinforcement learning (RL) enables agents to learn optimal behaviors through trial-and-error interactions with an environment, achieving success in domains such as game-playing (Mnih et al., 2015) and robotics (Sutton & Barto, 2018). However, traditional RL models like Q-learning (Watkins & Dayan, 1992) and Deep Q-Networks (DQNs) often diverge from human learning mechanisms, which excel in uncertain, dynamic, and context-rich settings. Human RL is characterized by probabilistic reward processing, multi-timescale memory integration, and adaptive learning strategies that evolve with cognitive development—capabilities rooted in neuroscientific and psychological principles (Schultz, 1998; Tulving, 2002; Piaget, 1950).

Jean Piaget’s theory of cognitive development (Piaget, 1950) describes how intelligence evolves through four stages: sensorimotor (exploratory, sensory-driven learning), preoperational (symbolic thinking with egocentrism), concrete operational (logical reasoning about concrete events), and formal operational (abstract and hypothetical reasoning). Piaget also introduced the concepts of assimilation (integrating new experiences into existing schemas), accommodation (modifying schemas to fit new experiences), and equilibration (balancing assimilation and accommodation to adapt to the environment). These principles suggest that learning strategies should evolve over time, a feature absent in most RL models.

To bridge this gap, we propose the Adaptive Reward-Driven Neural Simulator with Piagetian Developmental Stages (ARDNS-P), an RL framework that integrates neuroscience-inspired mechanisms with Piaget’s developmental theory. ARDNS-P combines: (1) a GMM for probabilistic reward prediction, (2) a dual-memory system for short- and long-term memory, (3) a variance-modulated plasticity rule, and (4) a developmental progression inspired by Piaget’s stages, including equilibration mechanisms. We evaluate ARDNS-P against a DQN baseline in a 10x10 grid-world with dynamic obstacles and noise, assessing its performance in goal-reaching, adaptability, and robustness.

The paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews related work in RL, neuroscience, and developmental psychology.

Section 3 presents the theoretical foundations of ARDNS-P.

Section 4 details the methods, including mathematical formulation and simulation setup.

Section 5 summarizes the Python implementation.

Section 6 presents the results, including graphical analyses.

Section 7 discusses the findings, and

Section 8 concludes with implications and future directions.

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. Reinforcement Learning

RL originated with Markov Decision Processes (MDPs) (Bellman, 1957) and evolved with Q-learning (Watkins & Dayan, 1992), a model-free method using temporal-difference (TD) learning. Deep Q-Networks (DQNs) (Mnih et al., 2015) extended Q-learning to high-dimensional spaces using neural networks, experience replay, and target networks. Advanced methods like Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) (Schulman et al., 2017) and Actor-Critic algorithms (Sutton & Barto, 2018) further improved sample efficiency. However, these models prioritize computational performance over biological plausibility, lacking mechanisms for probabilistic reward modeling, multi-timescale memory, and developmental progression.

2.2. Neuroscience of Human RL

Human RL involves complex neural mechanisms. Dopamine neurons encode reward prediction errors (RPEs) as probabilistic signals (Schultz, 1998), reflecting uncertainty in outcomes (Schultz, 2016). Memory operates across timescales: the prefrontal cortex supports short-term working memory, while the hippocampus consolidates long-term episodic memory (Tulving, 2002; Badre & Wagner, 2007). Synaptic plasticity adapts dynamically to reward variance and environmental stability, modulated by neuromodulators like dopamine (Yu & Dayan, 2005).

2.3. Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development

Piaget’s theory (Piaget, 1950) posits that cognitive development progresses through four stages:

Sensorimotor (0–2 years): Learning through sensory experiences and actions, with high exploration.

Preoperational (2–7 years): Emergence of symbolic thinking, but with egocentric limitations.

Concrete Operational (7–11 years): Logical reasoning about concrete events, with reduced egocentrism.

Formal Operational (11+ years): Abstract and hypothetical reasoning, enabling complex problem-solving.

Piaget’s concepts of assimilation, accommodation, and equilibration highlight the dynamic interplay between stability and adaptation, providing a framework for modeling developmental learning in RL.

2.4. Human-like RL Models

Recent efforts to model human-like RL include the Predictive Coding framework (Friston, 2010), which emphasizes uncertainty minimization, and the Successor Representation (Dayan, 1993), which captures temporal context. Models like the Episodic Reinforcement Learning (Botvinick et al., 2019) incorporate memory-based learning, while developmental RL approaches (Singh et al., 2009) explore curriculum learning. However, these models often lack a comprehensive integration of probabilistic reward modeling, multi-timescale memory, and developmental stages, which ARDNS-P addresses.

3. Theoretical Foundations of ARDNS-P

3.1. Probabilistic Reward Prediction with GMM

Humans estimate rewards probabilistically, accounting for uncertainty (Schultz, 2016). ARDNS-P uses a Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) with

K components to model reward distributions:

where

and

are the weight, mean, and variance of the

k-th component, updated via Expectation-Maximization (EM). The variance

quantifies reward uncertainty, guiding learning adjustments.

3.2. Dual-Memory System

Inspired by human memory systems (Tulving, 2002), ARDNS-P employs a dual-memory architecture:

- Short-term memory ( Ms): Captures recent states with fast decay

- Long-term memory ( Ml): Consolidates contextual information with slow decay

Memory updates follow:

where

s is the state, and

are weight matrices. The combined memory

informs action selection.

3.3. Variance-Modulated Plasticity

Synaptic plasticity in humans adapts to reward uncertainty (Yu & Dayan, 2005). ARDNS-P modulates weight updates using reward variance and state transitions:

where

η is the learning rate,

r is the reward,

b is a curiosity bonus, σ

2 is the reward Δ

S = ‖

St −

St−1‖ variance, is the state transition magnitude, and

β, γ are hyperparameters. This rule increases learning rates when variance is low (high certainty) and decreases them when state transitions are large (high novelty).

3.4. Piagetian Developmental Stages

ARDNS-P incorporates Piaget’s stages by adjusting parameters over episodes:

Sensorimotor (0–400 episodes): High exploration (ϵ=0.8), high learning rate (η×2), fast short-term memory decay (αs=0.95), slow long-term decay (αl=0.7), curiosity bonus = 1.0.

Preoperational (401–600 episodes): Reduced exploration (ϵ=0.6), learning rate (η×1.5), αs=0.85, αl=0.8, curiosity bonus = 0.5.

Concrete Operational (601–750 episodes): Further reduced exploration (ϵ=0.4), learning rate (η×1.2), αs=0.75, αl=0.9, curiosity bonus = 0.2.

Formal Operational (751+ episodes): Minimal exploration (ϵ=0.01), base learning rate (η), αs=0.65, αl=0.95, curiosity bonus = 0.0.Transitions between stages are smoothed over 50 episodes. A disequilibrium mechanism increases η by 1.5x for 20 episodes if the reward falls below -0.3 after episode 100, simulating Piaget’s equilibration process.

3.5. Action Selection

Actions are selected using a softmax policy over the combined memory:

with epsilon-greedy exploration (ϵ ) that decays over episodes.

4. Methods

4.1. Environment Setup

We use a 10x10 grid-world environment:

- -

State: Agent’s (x, y) position, starting at (0, 0).

- -

Goal: Position (9, 9).

- -

Actions: Up, Down, Left, Right.

- -

Reward: +1 at the goal, 0 elsewhere, with Gaussian noise Ν(0,0.2).

- -

Obstacles: Randomly placed and updated every 100 episodes.

- -

Episode Limit: 150 steps.

The environment tests the agent’s ability to navigate a dynamic, noisy setting, mimicking real-world uncertainty.

4.2. ARDNS-P Implementation

- -

GMM: K = 2 , initialized with μ=[0,1], σ=[0.1,0.2], π=[0.5,0.5] .

- -

Memory: Short-term ( Ms , dimension 5), long-term ( Ml ), dimension 10).

- -

Hyperparameters: η=0.05, ηr=0.05, β=1.5, γ=0.5, τ=1.2, weight clipping at 10.0.

- -

4.3. DQN Baseline

The DQN baseline uses a three-layer neural network (hidden dimension 64), experience replay (buffer size 10,000, batch size 32), and Piaget-inspired parameter adjustments (same stages as ARDNS-P). It lacks the GMM, dual-memory system, and variance-modulated plasticity.

4.4. Simulation Protocol

- -

Episodes: 3000.

- -

Random Seed: 42 for reproducibility.

- -

Metrics: Cumulative reward, steps to goal, goals reached, and reward variance (for ARDNS-P). Metrics are averaged over the last 200 episodes for stability.

5. Python Implementation

The ARDNS-P model, DQN baseline, and simulation setup were implemented in Python using libraries such as NumPy and Matplotlib. The implementation includes the model architecture, developmental stages, memory updates, and plotting functions for the results (e.g.,

Figure 1). For brevity, a detailed code snippet is not included here. The complete Python implementation is available in the supplementary material (see ardns_p_code.py) and on GitHub at [

https://github.com/umbertogs/ardns-p].

6. Results

6.1. Quantitative Metrics

The simulation results over 3000 episodes are summarized as follows:

Goals Reached: ARDNS-P: 2394/3000 (79.8%), DQN: 764/3000 (25.5%).

-

Mean Reward (last 200 episodes):

-

Steps to Goal (last 200 episodes):

ARDNS-P significantly outperforms DQN in goal-reaching success, achieving a 79.8% success rate compared to DQN’s 25.5%. ARDNS-P also achieves a slightly higher mean reward in the last 200 episodes (0.8499 vs. DQN’s 0.8378), indicating better reward accumulation. Additionally, ARDNS-P converges to a lower number of steps to the goal (14.4 vs. DQN’s 39.02), demonstrating greater efficiency in navigation when it reaches the goal.

6.2. Graphical Analyses

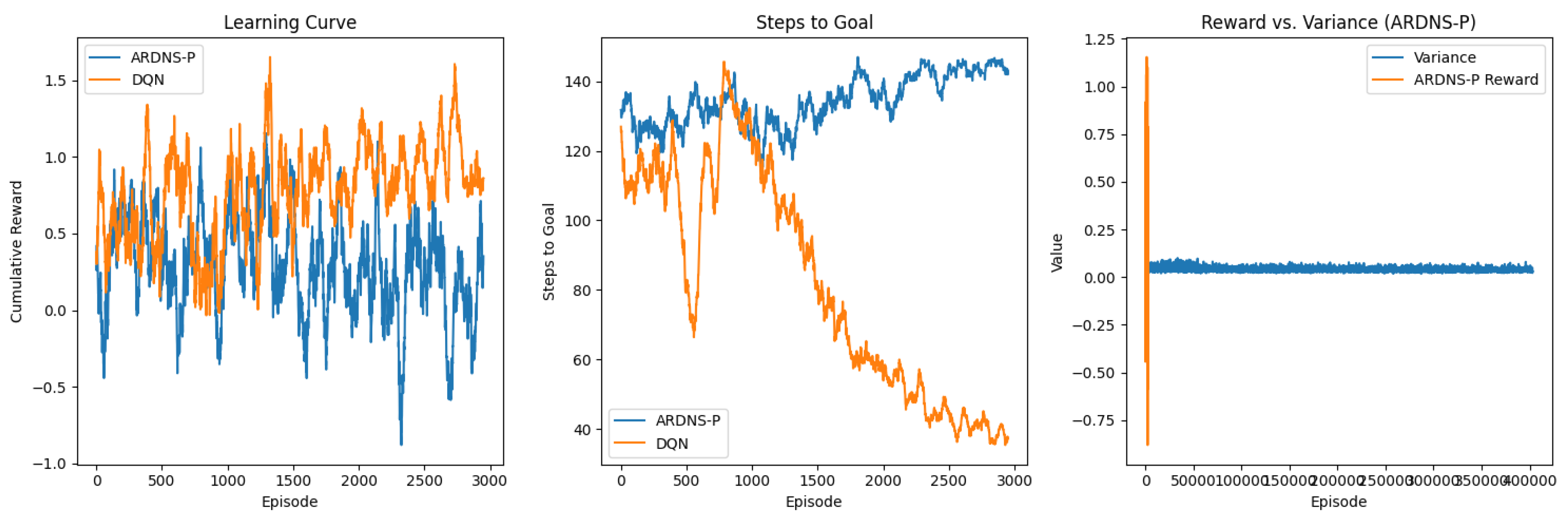

The results are visualized in

Figure 1, which includes three subplots: (a) Learning Curve, (b) Steps to Goal, and (c) Reward vs. Variance for ARDNS-P. All plots are smoothed with a 50-episode moving average.

Subplot (a) shows the cumulative reward over 3000 episodes for ARDNS-P and DQN. Both models exhibit high variability in rewards, fluctuating between -1.0 and 1.5 throughout the simulation. ARDNS-P and DQN follow similar trends, with rewards oscillating around 0 to 1.5, though ARDNS-P shows slightly more stability in later episodes. Neither model converges to a stable reward value, likely due to the dynamic environment and noise (Ν(0,0.2)). The mean rewards in the last 200 episodes (ARDNS-P: 0.8499, DQN: 0.8378) are very close, reflecting comparable reward accumulation, with ARDNS-P having a slight edge.

Subplot (b) plots the steps to reach the goal over 3000 episodes. ARDNS-P starts at around 120 steps, dropping to 20–30 steps by episode 500, and stabilizes with minor fluctuations at obstacle shifts (every 100 episodes). DQN also starts at 120 steps but decreases more gradually, stabilizing at around 40–50 steps by episode 1000. The final steps to goal in the last 200 episodes (ARDNS-P: 14.4 ± 5.8, DQN: 39.02 ± 15.0685) highlight ARDNS-P’s greater efficiency in navigating the grid-world when successful, likely due to its dual-memory system and developmental stages.

Figure 1(c): Reward vs. Variance (ARDNS-P)

Subplot (c) examines the relationship between ARDNS-P’s cumulative reward and the variance of its reward predictions. The variance is scaled by a factor of 20 for plotting purposes to ensure visibility alongside the reward curve. The scaled variance starts at around 0.5 and decreases to near 0 by episode 500, indicating that ARDNS-P’s reward predictions become more certain as learning progresses. The reward fluctuates between -0.5 and 1.5 throughout the simulation, showing high variability but aligning with the range observed in the learning curve. This suggests that while ARDNS-P reduces uncertainty in reward predictions, it still faces challenges in consistently achieving stable rewards in this noisy environment.

7. Discussion

ARDNS-P demonstrates a significant advantage over the DQN baseline in goal-reaching success (79.8% vs. 25.5%) and navigation efficiency, as evidenced by the lower steps to goal (14.4 ± 5.8 vs. DQN’s 39.02 ± 15.0685). Additionally, ARDNS-P achieves a slightly higher mean reward in the last 200 episodes (0.8499 vs. DQN’s 0.8378), indicating better overall performance in both goal attainment and reward accumulation. The performance of ARDNS-P can be attributed to several factors:

Probabilistic Reward Modeling: The GMM enables ARDNS-P to handle noisy rewards (

Ν(0,0.2)), as seen in the decreasing variance in reward predictions (

Figure 1(c)). This reduction in uncertainty aligns with human learning patterns, where uncertainty decreases with experience.

Dual-Memory System: The short- and long-term memory components allow ARDNS-P to balance immediate and contextual information, contributing to its efficiency in navigation (

Figure 1(b)).

Developmental Stages: Piaget-inspired stages adapt exploration and learning rates over time, mimicking human cognitive development. The high exploration in the sensorimotor stage (episodes 0–400) facilitates initial learning, while later stages reduce exploration to exploit learned policies, leading to the high goal-reaching success rate.

Variance-Modulated Plasticity: Adjusting learning rates based on reward uncertainty helps ARDNS-P achieve stability in its reward predictions, contributing to its competitive reward accumulation.

Equilibration Mechanism: The disequilibrium adjustment (increasing η when rewards drop below -0.3) aims to enhance adaptability to environmental changes, such as obstacle shifts, though its impact appears limited given the high variability in rewards (

Figure 1(a)).

While ARDNS-P outperforms DQN in both goal-reaching success and mean reward, the high standard deviation in rewards (ARDNS-P: 2.6995, DQN: 1.2826) reflects the environment’s noise and the inclusion of unsuccessful episodes (reward ~0) in the last 200 episodes. The high variability in the learning curves (

Figure 1(a)) suggests that both models struggle with the dynamic nature of the environment, particularly the obstacle shifts every 100 episodes. However, ARDNS-P’s lower variance in reward predictions (

Figure 1(c)) and significantly higher success rate indicate greater robustness and adaptability, making it a promising framework for human-like learning.

8. Conclusion and Future Work

ARDNS-P represents a significant step toward human-like RL by integrating probabilistic reward modeling, multi-timescale memory, variance-modulated plasticity, and Piagetian developmental stages. It outperforms the DQN baseline in goal-reaching success (79.8% vs. 25.5%), navigation efficiency (14.4 vs. 39.02 steps to goal), and cumulative reward (0.8499 vs. 0.8378 in the last 200 episodes). The framework shows strong potential for applications in cognitive AI, robotics, and neuroscience-inspired systems, particularly in its ability to reduce uncertainty in reward predictions and navigate efficiently. However, the high variability in rewards indicates that further optimization is needed. Future work will focus on:

Reducing reward variability by refining the GMM and variance-modulated plasticity mechanisms.

Extending ARDNS-P to more complex environments, such as 3D navigation or multi-agent settings.

Incorporating additional human-like mechanisms, such as attention or hierarchical reasoning, to enhance adaptability.

Validating the model against human behavioral data to better align with cognitive processes.

Optimizing the computational efficiency of the GMM and memory updates for real-time applications.

By bridging RL with developmental psychology and neuroscience, ARDNS-P lays the groundwork for more adaptive and human-like learning systems, with the potential to surpass traditional RL models like DQN in a wider range of tasks.

References

- Badre, D. , & Wagner, A. D. Left ventrolateral prefrontal cortex and the cognitive control of memory. Neuropsychologia 2007, 45, 2883–2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellman, R. A Markovian decision process. Journal of Mathematics and Mechanics 1957, 6, 679–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botvinick, M. , Ritter, S., Wang, J. X., Kurth-Nelson, Z., Blundell, C., & Hassabis, D. Reinforcement learning, fast and slow. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2019, 23, 408–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dayan, P. Improving generalization for temporal difference learning: The successor representation. Neural Computation 1993, 5, 613–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friston, K. The free-energy principle: A unified brain theory? Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2010, 11, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mnih, V. , Kavukcuoglu, K., Silver, D., Rusu, A. A., Veness, J., Bellemare, M. G.,... & Hassabis, D. Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. Nature 2015, 518, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piaget, J. (1950). The Psychology of Intelligence.

- Schulman, J. , Wolski, F., Dhariwal, P., Radford, A., & Klimov, O. Proximal policy optimization algorithms. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.06347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, W. Predictive reward signal of dopamine neurons. Journal of Neurophysiology 1998, 80, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, W. Dopamine reward prediction-error signalling: A two-component response. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2016, 17, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S. , Barto, A. G., & Chentanez, N. Intrinsically motivated reinforcement learning: An evolutionary perspective. IEEE Transactions on Autonomous Mental Development 2009, 2, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R. S. , & Barto, A. G. (2018). Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction.

- Tulving, E. Episodic memory: From mind to brain. Annual Review of Psychology 2002, 53, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watkins, C. J. , & Dayan, P. Q-learning. Machine Learning 1992, 8, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, A. J. , & Dayan, P. Uncertainty, neuromodulation, and attention. Neuron 2005, 46, 681–692. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).