Submitted:

24 March 2025

Posted:

25 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

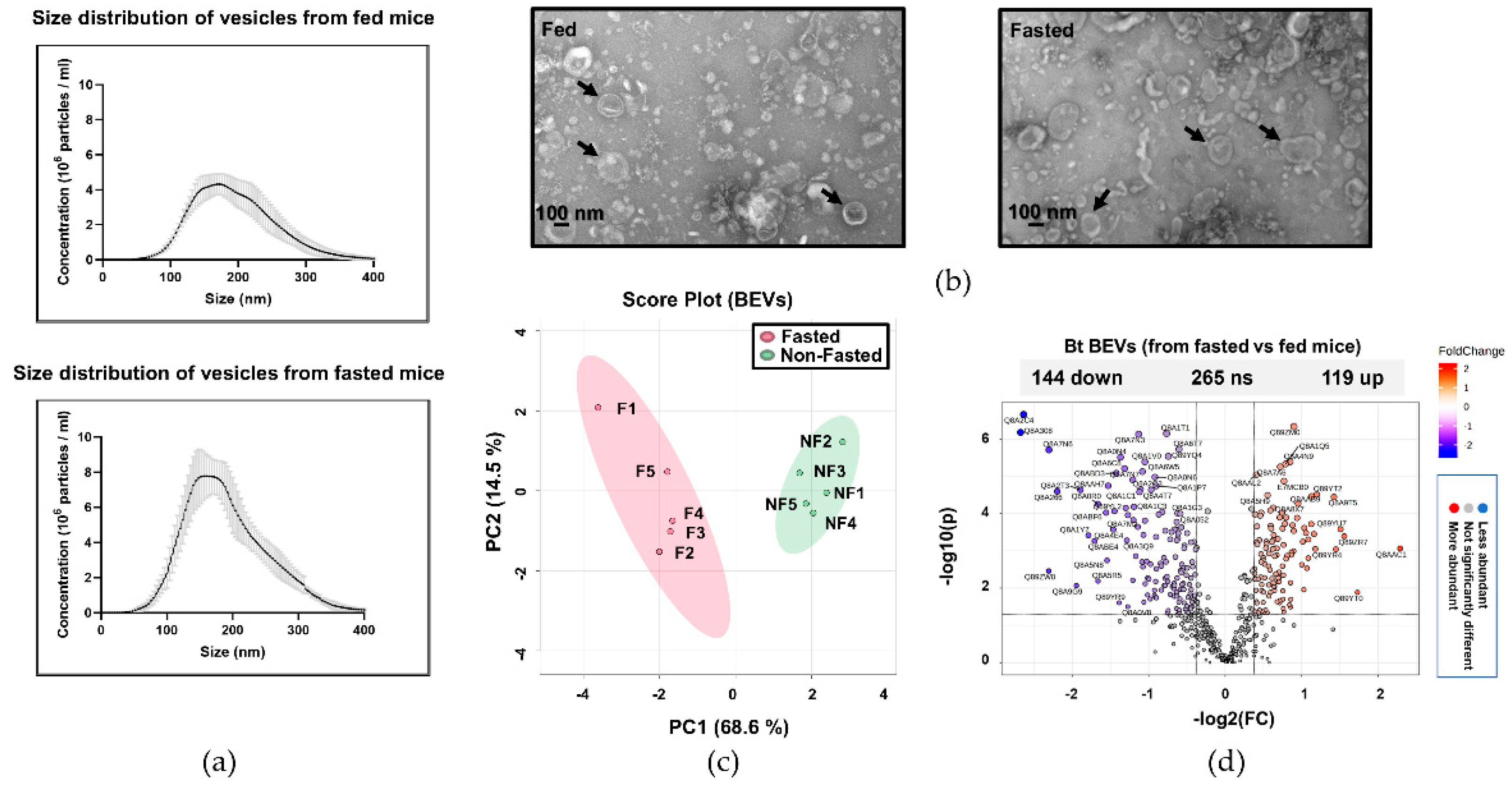

2.1. The Proteome of BEVs Produced In Vivo

2.2. Serine proteases are less abundant in BEVs produced in fasted mice

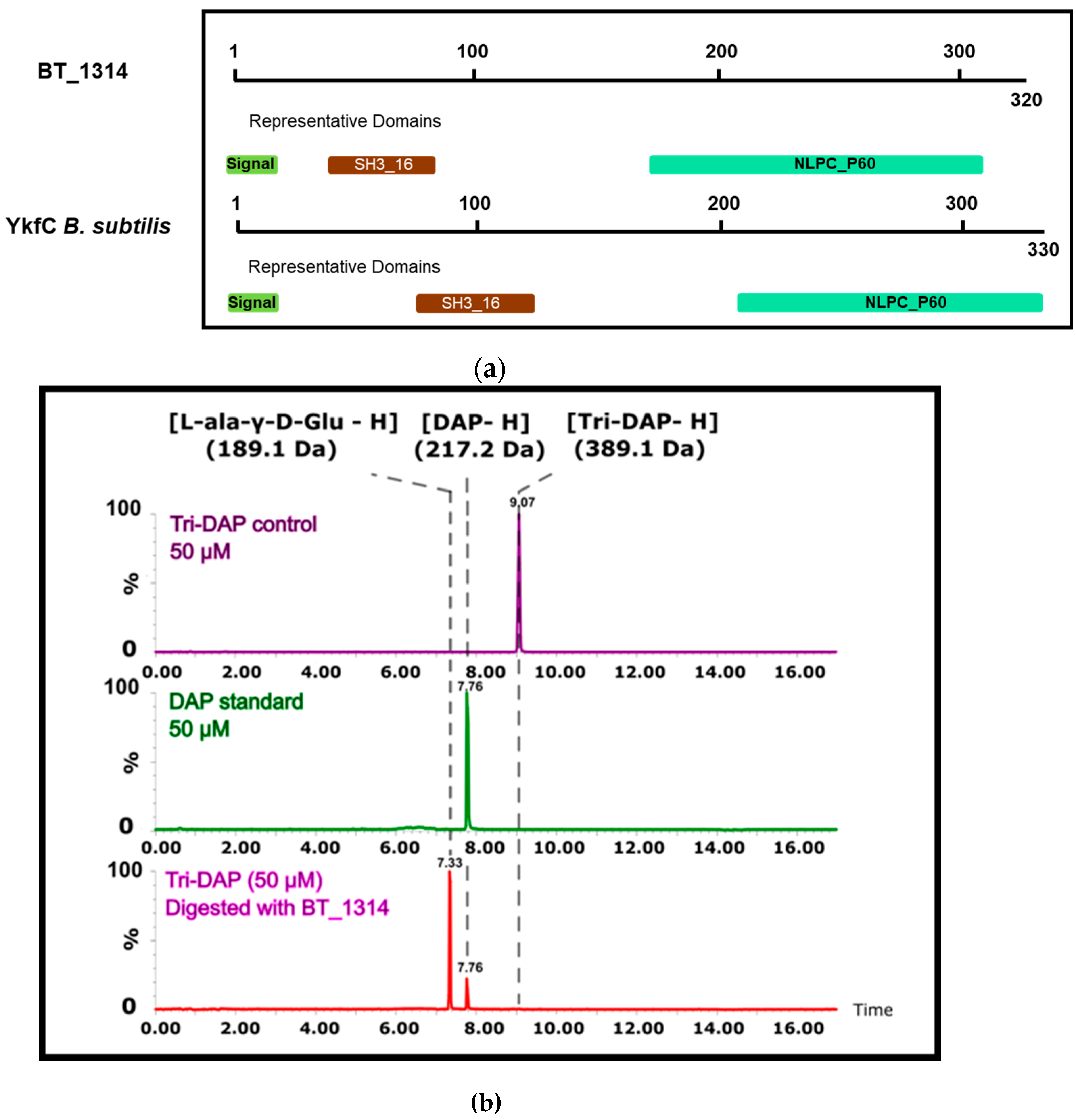

2.3. BT_1314 is a γ-D-glutamyl-L-diamino Acid Endopeptidase

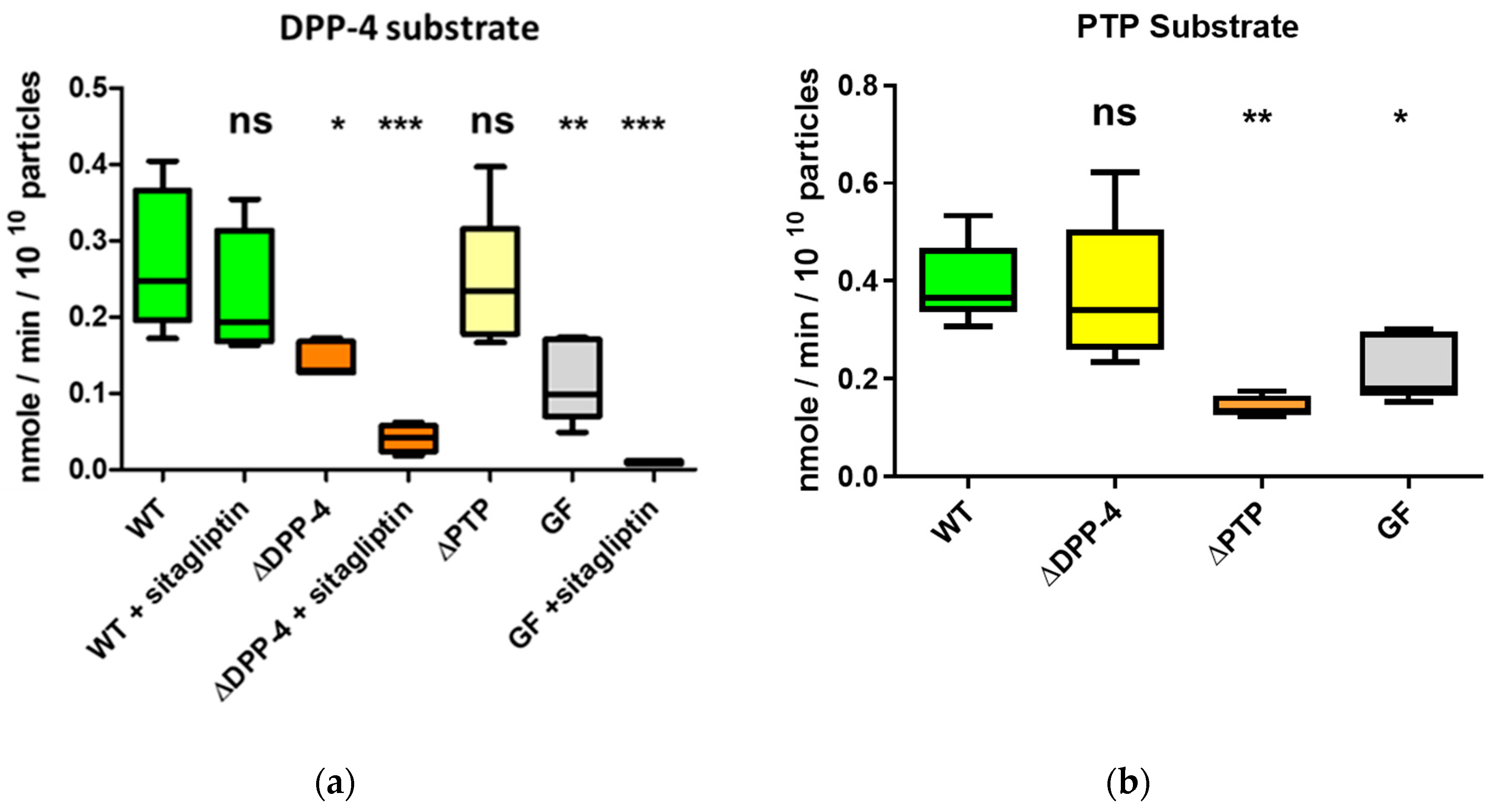

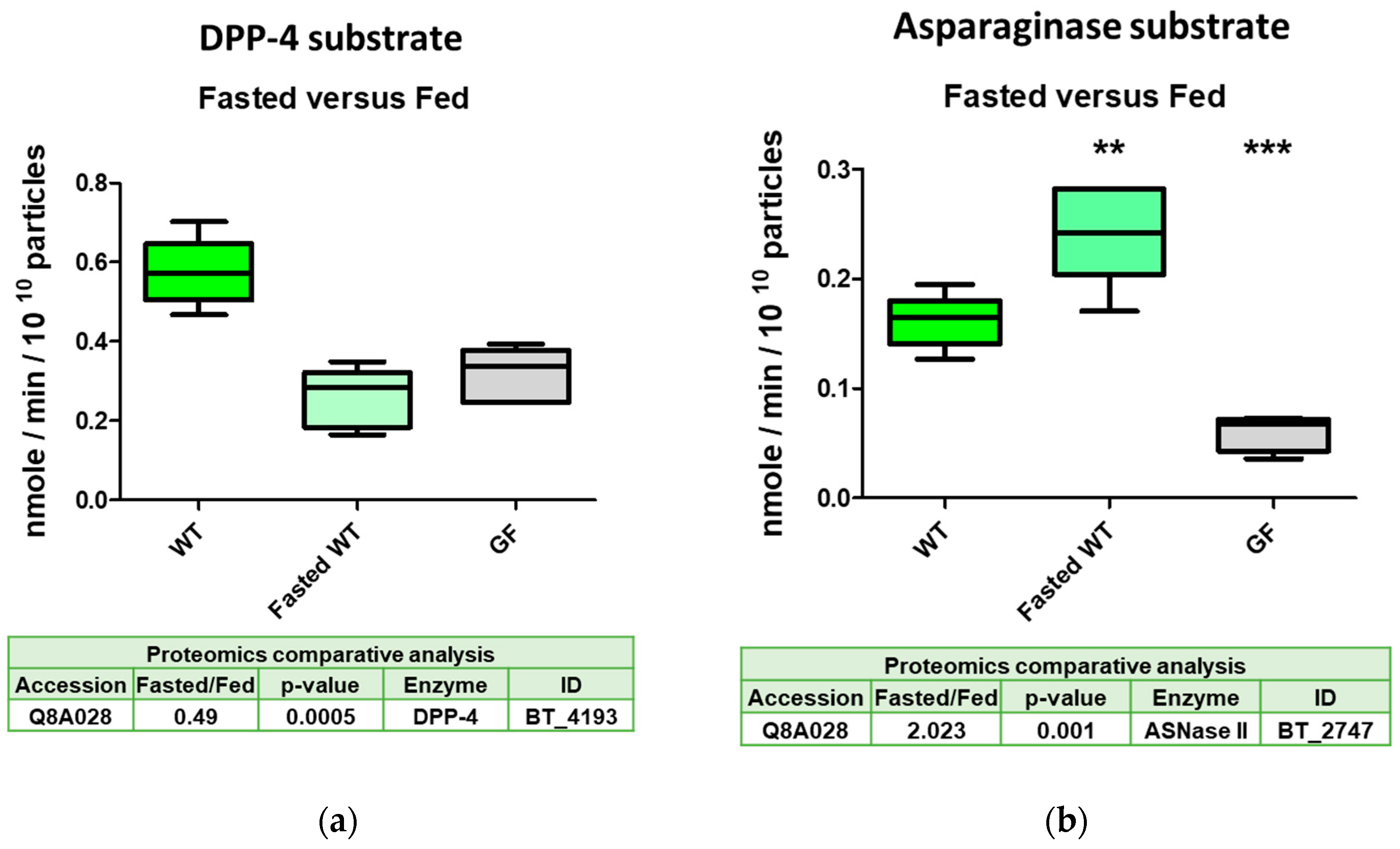

2.4. The Serine Protease BT_4193 Is a Functional DPP-4 Enzyme in BEVs

2.5. DPP-4 Activity in Intestinal Derived BEVs Is Decreased Under Fasting Conditions

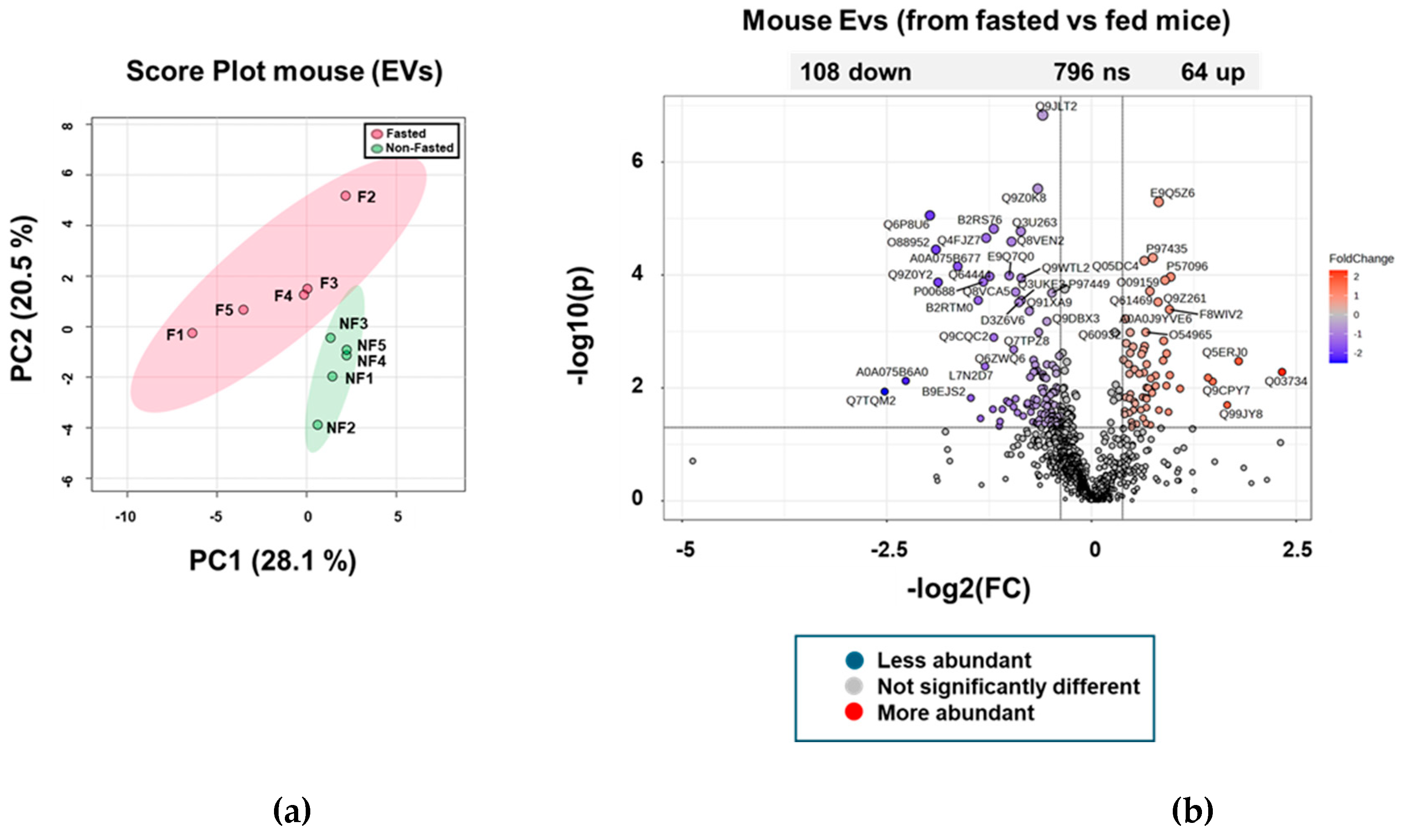

2.6. Proteome of Host EVs Produced in the GIT

2.7. Increased Abundance of Serine Protease Inhibitors and Antimicrobial Proteins in Host EVs Produced In Vivo

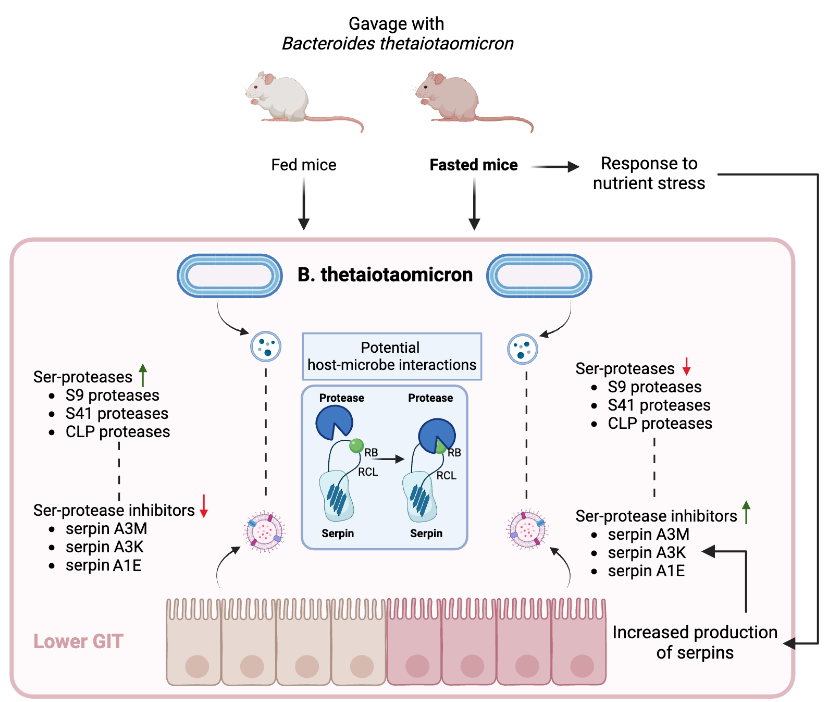

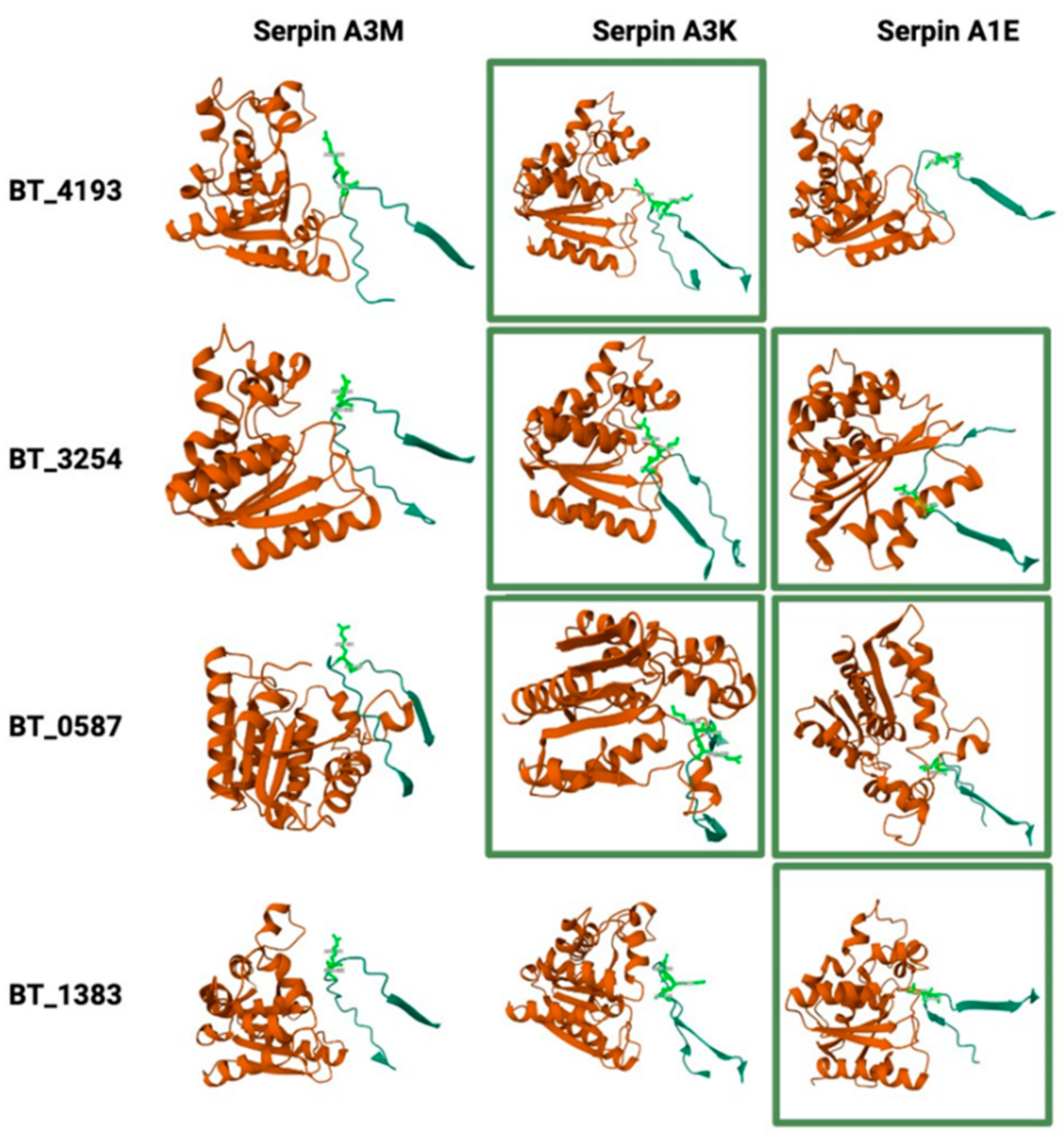

2.8. Potential Interactions Between Host Serpins and Bacterial Serine Proteases

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animal Studies

4.2. Nanoparticle Analysis

4.3. Proteomics

4.4. Statistical Analysis

4.5. Proteomics Data Curation

4.6. Gene Ontology Analysis

4.7. Electron Microscopy

4.8. BT_3254 (PTP) and BT_4193 (DPP-4) Deletion Mutants

4.9. DPP-4, PTP and Asparaginase Assays

4.10. Recombinant BT_1314 and Enzymatic Activity

4.11. Structural Analysis of Potential Bacterial Protease—Host Serpin Interactions

- MSA mode: mmseqs2_uniref_env – AlphaFold 2 suggests this mode, as in most cases mmseqs2_uniref_env tends to produce the best results;

- Paired mode: unpaired – as the bacterial and host proteins are from different organisms, the unpaired set up separates the MSA for each chain;

- Number of ensembles recycles: Default settings (five recycles) were used to balance computational time with model accuracy;

- Number of ensembles: Default settings – 1 ensemble. The trunk of the network is run multiple times with different random choices for the MSA cluster centers.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hou, K.; Wu, Z.X.; Chen, X.Y.; Wang, J.Q.; Zhang, D.; Xiao, C.; Zhu, D.; Koya, J.B.; Wei, L.; Li, J.; et al. Microbiota in health and diseases. Signal Transduct. Targeted Ther. 2022, 7, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribaldone, D.G.; Pellicano, R.; Fagoonee, S.; Actis, G.C. Modulation of the gut microbiota: Opportunities and regulatory aspects. Minerva Gastroenterol. 2023, 69, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; He, M.; Yang, M.; Ai, X. Gut microbiota as a key regulator of intestinal mucosal immunity. Life Sci. 2024, 345, 122612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickard, J.M.; Zeng, M.Y.; Caruso, R.; Núñez, G. Gut microbiota: Role in pathogen colonization, immune responses, and inflammatory disease. Immunol. Rev. 2017, 279, 70–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandrini S; Aldriwesh M; Alruways M; Freestone P. Microbial endocrinology: host-bacteria communication within the gut microbiome. J. Endocrinol. 2015, 225, R21–R34. [CrossRef]

- Spragge, F.; Bakkeren, E.; Jahn, M.T.; Araujo, E.B.N.; Pearson, C.F.; Wang, X.; Pankhurst, L.; Cunrath, O.; Foster, K.R. Microbiome diversity protects against pathogens by nutrient blocking. Science 2023, 382, eadj3502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J.A. Modulating brain function with microbiota. Science 2022, 376, 936–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Sakamoto, S.; Ishii, C.; Smith, M.D.; Ito, K.; Obayashi, M.; Tanaka, T.K.; Suzuki, Y.A.; Takahashi, H.K.; Nakamura, S.H; et al. Dectin-1 signaling on colonic γδ T cells promotes psychosocial stress responses. Nat. Immunol. 2023, 24, 625–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keely, SJ. Decoding host–microbiota communication in the gut – now we're flying! J. Physiol. 2017, 595, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, R.; Zhang, D.; Qi, S.; Liu, Y. Metabolite interactions between host and microbiota during health and disease: Which feeds the other? Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 160, 114295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulkens, J.; De Wever, O.; Hendrix, A.; Dhondt, B.; Pinheiro, C.; Geeurickx, E.; Vergauwen, G.; Van Der Pol, E.; Nieuwland, R.; Decock, A.; et al. Analyzing bacterial extracellular vesicles in human body fluids by orthogonal biophysical separation and biochemical characterization. Nat. Protoc. 2020, 15, 40–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryant, W.A.; Stentz, R.; Le Gall, G.; Sternberg, M.J.E.; Carding, S.R.; Wilhelm, T. In silico analysis of the small molecule content of outer membrane vesicles produced by Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron indicates an extensive metabolic link between microbe and host. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsen, I.; Amano, A. Outer membrane vesicles - offensive weapons or good Samaritans? J. Oral Microbiol. 2015, 7, 27468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, H.M.; Kuehn, M.J.; Zebell, S.G.; Ristaino, J.B.; Dong, X.; Rogers, N.; Wadle, A.; Wiesner, M.R.; Hendren, C.O.; Hsu-Kim, H. The extracellular vesicle generation paradox: a bacterial point of view. EMBO J. 2021, 40, e108174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juodeikis, R.; Carding, S.R. Outer membrane vesicles: biogenesis, functions, and issues. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2022, 86, e0003222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Dai, N.; Sheng, K.; Lu, H.; Wang, J.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Y.H; Zhao, Q.L; Li, F.S; Wu, Z.Y; et al. Gut bacterial extracellular vesicles: important players in regulating intestinal microenvironment. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2134689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakoff-Nahoum S., Coyne M.J., Comstock L.E. An ecological network of polysaccharide utilization among human intestinal symbionts. Curr. Biol. 2014, 24, 40–49. [CrossRef]

- Stentz, R.; Carvalho, A.L.; Jones, E.; Carding, S.R. Fantastic voyage: the journey of intestinal microbiota-derived microvesicles through the body. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2018, 46, 1021–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durant, L.; Stentz, R.; Noble, A.; Brooks, J.; Gicheva, N.; Reddi, D.; O'Connor, M. J.; Hoyles, L.; McCartney, A. L.; Man, R.; et al. Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron-derived outer membrane vesicles promote regulatory dendritic cell responses in health but not in inflammatory bowel disease. Microbiome, 2020, 8, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhenawy, W.; Debelyy, M.O.; Feldman, M.F. Preferential packing of acidic glycosidases and proteases into Bacteroides outer membrane vesicles. mBio 2014, 5, e00909-14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stentz, R.; Jones, E.; Juodeikis, R.; Wegmann, U.; Guirro, M.; Goldson, A.; Brion, A.; Booth, C.; Sudhakar, P.; Brown, I.R.; et al. The proteome of extracellular vesicles produced by the human gut bacteria Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron in vivo is influenced by environmental and host-derived factors. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 88, e0053322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Niel, G.; Raposo, G.; Candalh, C.; Boussac, M.; Hershberg, R.; Cerf-Bensussan, N.; Heyman, M.; Thery, C.; Chamaillard, M.; Savina, A.; et al. Intestinal epithelial cells secrete exosome-like vesicles. Gastroenterology 2001, 121, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mignini, I.; Piccirilli, G.; Termite, F.; Paratore, M.; Esposto, G.; Laterza, L.; Petito, V.; Lopetuso, L.R.; Schiavoni, E.; Scaldaferri, F.; et al. Extracellular vesicles: novel potential therapeutic agents in inflammatory bowel diseases. Cells 2023, 13, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.J.; Shimaoka, M.; Kiyono, H. Functional flexibility of exosomes and microRNAs of intestinal epithelial cells in affecting inflammation. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 854487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Deeke, S.A.; Ning, Z.; Starr, A.E.; Butcher, J.; Li, J.; Mayne, J.; Cheng, K.; Liao, B.; Li, L.; et al. Metaproteomics reveals associations between microbiome and intestinal extracellular vesicle proteins in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.D.; King, P.T.; Bai, X.; Schoffstall, A.M.; Sandhaus, R.A.; Buckle, A.M. The inhibition of serine proteases by serpins is augmented by negatively charged heparin: A concise review of some clinically relevant interactions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Navarro, A.; Gonzalez-Soria, I.; Caldino-Bohn, R.; Bobadilla, N.A. An integrative view of serpins in health and disease: the contribution of SerpinA3. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2021, 320, C106–C118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, J.W.; Xu, H.; Chen, X.; Gao, Y.; Jiang, H.G.; Wang, Y.; Wu, H.; Yang, L.; Wang, W.B.; et al. Therapy-induced senescent tumor cell-derived extracellular vesicles promote colorectal cancer progression through SERPINE1-mediated NF-κB p65 nuclear translocation. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrapon, N.; Lombard, V.; Drula, É.; Lapébie, P.; Al-Masaudi, S.; Gilbert, H.J.; Henrissat, B.; Raghavan, V.; Hess, M.; Pereira, G.; et al. PULDB: the expanded database of Polysaccharide Utilization Loci. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D677–D683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stentz, R.; Cheema, J.; Philo, M.; Carding, S.R. A Possible Aquatic Origin of the Thiaminase TenA of the Human Gut Symbiont Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron. J. Mol. Evol. 2023, 91, 482–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, A.H.; Schyns, G.; Potot, S.; Sun, G.; Begley, T.P. A new thiamin salvage pathway. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007, 3, 492–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivares, M.; Schüppel, V.; Hassan, A.M.; Beaumont, M.; Neyrinck, A.M.; Bindels, L.B.; Benítez-Páez, A.; Sanz, Y.; Haller, D.; Holzer, P.; et al. The potential role of the dipeptidyl peptidase-4-like activity from the gut microbiota on the host health. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, L.J.; Nguyen, T.H.; Liu, L.J.; Hurysz, B.M.; Lakemeyer, M.; Guerra, M.; Gelsinger, D.J.; Chanin, R.; Ngo, N.; Lum, K.M.; et al. Chemoproteomic identification of a DPP4 homolog in Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2023, 19, 1469–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malloy, C.; Ahern, M.; Lin, L.; Hoffman, D.A. Neuronal roles of the multifunctional protein dipeptidyl peptidase-like 6 (DPP6). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Abdubek, P.; Astakhova, T.; Axelrod, H.L.; Bakolitsa, C.; Cai, X.; Carlton, D.; Chen, C.; Chiu, H.J.; Chiu, M.; et al. Structure of the γ-D-glutamyl-L-diamino acid endopeptidase YkfC from Bacillus cereus in complex with L-Ala-γ-D-Glu: insights into substrate recognition by NlpC/P60 cysteine peptidases. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 2010, 66, 1354–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paysan-Lafosse, T.; Blum, M.; Chuguransky, S.; Grego, T.; Pinto, B.L.; Salazar, G.A.; Bileschi, M.L.; Bork, P.; Bridge, A.; Colwell, L.; et al. InterPro in 2022. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 51, D418–D427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalmasso, G.; Nguyen, H.T.; Charrier-Hisamuddin, L.; Yan, Y.; Laroui, H.; Demoulin, B.; Sitaraman, S.V.; Merlin, D. PepT1 mediates transport of the proinflammatory bacterial tripeptide L-Ala-γ-D-Glu-meso-DAP in intestinal epithelial cells. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2009, 299, G687–G696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Zhang, Z.; Hang, J.; Liu, J.; Guo, F.; Ding, Y.; Li, M.; Nie, Q.; Wu, H.; Ding, Q.; et al. Microbial-host-isozyme analyses reveal microbial DPP4 as a potential antidiabetic target. Science 2023, 381, eadd5787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagiannides, I.; Torres, D.; Tseng, Y.H.; Bowe, C.; Carvalho, E.; Espinoza, D.O.; Luan, Q.; Bronson, R.; Smith, S.R.; Kokkotou, E.G. Substance P as a novel anti-obesity target. Gastroenterology 2008, 134, 747–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitti, S.V.; Gummadi, S.; Kang, T.; Shahi, S.; Marzan, A.L.; Nedeva, C.; Sanwlani, R.; Mathivanan, S.; Kalra, H.; Gupta, V.; et al. Vesiclepedia 2024: an extracellular vesicles and extracellular particles repository. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, D1694–D1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raposo, G.; Stoorvogel, W. Extracellular vesicles: exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J. Cell Biol. 2013, 200, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hessvik, N.P.; Llorente, A. Current knowledge on exosome biogenesis and release. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2018, 75, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeppesen, D.K.; Fenix, A.M.; Franklin, J.L.; Higginbotham, J.N.; Zhang, Q.; Zimmerman, L.J.; Liebler, D.C.; Ping, J.; Liu, Q.; Evans, R.; et al. Reassessment of Exosome Composition. Cell 2019, 177, 428–445.e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouton, M.C.; Geiger, M.; Sheffield, W.P.; Irving, J.A.; Lomas, D.A.; Song, S.; Gettins, P.G.W.; Rau, J.C.; Olson, S.T.; Huntington, J.A.; et al. The under-appreciated world of the serpin family of serine proteinase inhibitors. EMBO Mol. Med. 2023, 15, e17144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Yokoi, Y.; Fukaya, R.; Ohira, S.; Shinozaki, R.; Nishida, T.; Takaki, M.; Sano, Y.; Shibata, S.; Higashiyama, S.; et al. Expression and localization of Paneth cells and their α-defensins in the small intestine of adult mouse. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 570296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marijanovic, E.M.; Fodor, J.; Riley, B.T.; Needham, E.J.; Cabrita, L.D.; Bottomley, S.P.; Buckle, A.M. Reactive centre loop dynamics and serpin specificity. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohl, K.D.; Amaya, J.; Passement, C.A.; Dearing, M.D.; McCue, M.D. Unique and shared responses of the gut microbiota to prolonged fasting: A comparative study across five classes of vertebrate hosts. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2014, 90, 883–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cignarella, F.; Cantoni, C.; Ghezzi, L.; Salter, A.; Dorsett, Y.; Chen, L.; Phillips, D.; Weinstock, G.M.; Fontana, L.; Cross, A.H.; et al. Intermittent fasting confers protection in CNS-autoimmunity by altering the gut microbiota. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 1222–1235.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macfarlane, G.T.; Gibson, G.R. Formation of glycoprotein degrading enzymes by Bacteroides fragilis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1991, 61, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnenburg, J.L.; Xu, J.; Leip, D.D.; Chen, C.H.; Westover, B.P.; Weatherford, J.; Buhler, J.D.; Gordon, J.I. Glycan foraging in vivo by an intestine-adapted bacterial symbiont. Science 2005, 307, 1955–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, E.C.; Chiang, H.C.; Gordon, J.I. Mucosal glycan foraging enhances fitness and transmission of a saccharolytic human gut bacterial symbiont. Cell Host Microbe 2008, 4, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caminero, A.; Guzman, M.; Libertucci, J.; Lomax, A.E. The emerging roles of bacterial proteases in intestinal diseases. Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2181922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galipeau, H.J.; Caminero, A.; Turpin, W.; Bermudez-Brito, M.; Santiago, A.; Libertucci, J.; Constante, M.; Raygoza Garay, J.A.; Rueda, G.; Armstrong, S.; et al. Novel fecal biomarkers that precede clinical diagnosis of ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 1532–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galipeau, H.J.; Caminero, A.; Verdu, E.F. Increased bacterial proteolytic activity detected before diagnosis of ulcerative colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2021, 27, e144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, R.H.; Dulai, P.S.; Vázquez-Baeza, Y.; Sauceda, C.; Daniel, N.; Gerner, R.R.; Batachari, L.E.; Malfavon, M.; Zhu, Q.; Weldon, K.; et al. Multi-omics analyses of the ulcerative colitis gut microbiome link Bacteroides vulgatus proteases with disease severity. Nature Microbiol. 2022, 7, 262–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E.J.; Booth, C.; Fonseca, S.; Parker, A.; Cross, K.; Miquel-Clopés, A.; Hautefort, I.; Mayer, U.; Wileman, T.; Stentz, R.; Carding, S.R. The Uptake, Trafficking, and Biodistribution of Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron Generated Outer Membrane Vesicles. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E.; Stentz, R.; Telatin, A.; Savva, G.M.; Booth, C.; Baker, D.; Rudder, S.; Knight, S.C.; Noble, A.; Carding, S.R. The Origin of Plasma-Derived Bacterial Extracellular Vesicles in Healthy Individuals and Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Pilot Study. Genes 2021, 12, 1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mezer, M.; Rogaliński, J.; Przewoźny, S.; Chojnicki, M.; Niepolski, L.; Sobieska, M.; Żaba, R.; Adamski, Z.; Bowszyc-Dmochowska, M.; Dańczak-Pazdrowska, A. SERPINA3: Stimulator or inhibitor of pathological changes. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edogawa, S.; Edwinson, A.L.; Peters, S.A.; Chikkamenahalli, L.L.; Sundt, W.; Graves, S.; Gurunathan, S.V.; Breen-Lyles, M.; Johnson, S.; Dyer, R.; et al. Serine proteases as luminal mediators of intestinal barrier dysfunction and symptom severity in IBS. Gut 2019, 69, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, A.K.; Yu, Z. Genomic Insights into the Distribution of Peptidases and Proteolytic Capacity among Prevotella and Parabacteroides Species. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0218521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambadapadi, S.; Munuswamy-Ramanujam, G.; Zheng, D.; Sullivan, C.; Dai, E.; Morshed, S.; McFadden, B.; Feldman, E.; Pinard, M.; McKenna, R.; et al. Reactive center loop (RCL) peptides derived from serpins display independent coagulation and immune modulating activities. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 2874–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bui, T.M.; Mascarenhas, L.A.; Sumagin, R. Extracellular vesicles regulate immune responses and cellular function in intestinal inflammation and repair. Tissue Barriers 2018, 6, e1431038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, M. , Karlsson-Sjöberg, J. & Pütsep, KA. CRS-peptides: unique defense peptides of mouse Paneth cells. Mucosal Immunol 2012, 5, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mi, H.; Muruganujan, A.; Huang, X.; Ebert, D.; Mills, C.; Guo, X.; Thomas, P.D. Protocol Update for large-scale genome and gene function analysis with the PANTHER classification system (v.14.0). Nat. Protoc. 2019, 14, 703–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Bayona, L.; Comstock, L.E. Streamlined genetic manipulation of diverse Bacteroides and Parabacteroides isolates from the human gut microbiota. mBio 2019, 10, e01762–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stentz, R.; Horn, N.; Cross, K.; Salt, L.; Brearley, C.; Livermore, D.M.; Carding, S.R. Cephalosporinases associated with outer membrane vesicles released by Bacteroides sp. protect gut pathogens and commensals against β-lactam antibiotics. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015, 70, 701–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zeng, X.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, R. AlphaFold2 and its applications in the fields of biology and medicine. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirdita, M.; Schütze, K.; Moriwaki, Y.; Heo, L.; Ovchinnikov, S.; Steinegger, M. ColabFold: making protein folding accessible to all. Nat. Methods 2022, 19, 679–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, R.; O'Neill, M.; Pritzel, A.; Antropova, N.; Senior, A.; Green, T.; Žídek, A.; Bates, R.; Blackwell, S.; Yim, J.; et al. Protein complex prediction with AlphaFold-Multimer. bioRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehnal, D.; Bittrich, S.; Deshpande, M.; Svobodová, R.; Berka, K.; Bazgier, V.; Velankar, S.; Burley, S.K.; Koča, J.; Rose, A.S. Mol* Viewer: modern web app for 3D visualization and analysis of large biomolecular structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W431–W437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Accession | Fasted/Feda | Protein classb | Accession | Fasted/Feda | Protein classb | |||

| Q8ABE4 | 0.306 | Oxidoreductase (PC00176) | Q8A739 | 0.645 | Ligase (PC00142) | |||

| Q8ABF6 | 0.34 | Serine protease (PC00203) BT_0154 | Q8A1G3 | 0.65 | Amylase (PC00048) | |||

| Q8AAH7 | 0.346 | Carbohydrate kinase (PC00065) | Q8A1H6 | 0.659 | Glycosidase (PC00110) | |||

| Q89YR9 | 0.382 | Lyase (PC00144) | Q8ABF8 | 0.664 | Esterase (PC00097) | |||

| Q8A3Q9 | 0.41 | Glycosidase (PC00110) | Q8A1Z2 | 0.671 | Glycosidase (PC00110) | |||

| Q8A2Q1 | 0.474 | Serine protease (PC00203) BT_3254 | Q8AA78 | 0.672 | Serine protease (PC00203) BT_0587 | |||

| Q8A3W3 | 0.478 | Kinase (PC00137) | Q8A9Q8 | 0.673 | Galactosidase (PC00104) | |||

| Q8AAV4 | 0.483 | Glycosidase (PC00110) | Q8A7W6 | 0.678 | Transporter (PC00258) | |||

| Q8A406 | 0.484 | Serine protease (PC00203) BT_2798 | Q8A1F8 | 0.689 | Phosphatase (PC00181) | |||

| Q8A028 | 0.49 | Serine protease (PC00203) BT_4193 | Q8A1K7 | 0.706 | Galactosidase (PC00104) | |||

| Q8A8R1 | 0.495 | Aldolase (PC00044) | Q89ZQ6 | 0.717 | Metalloprotease (PC00153) | |||

| Q8A7I6 | 0.495 | Hydrolase (PC00121) | Q8A862 | 0.728 | Serine protease (PC00203) BT_1312 | |||

| Q8A156 | 0.5 | Metalloprotease (PC00153) | Q8A4H0 | 0.739 | Hydrolase (PC00121) | |||

| Q8A7J8 | 0.507 | Isomerase (PC00135) | Q8A123 | 0.743 | Chaperone (PC00072) | |||

| Q8A4T7 | 0.511 | Dehydrogenase (PC00092) | Q8A4P9 | 0.756 | Transferase (PC00220) | |||

| Q8A1P7 | 0.536 | Chaperone (PC00072) | Q8A3A0 | 0.766 | Dehydrogenase (PC00092) | |||

| Q8A0A2 | 0.561 | Lyase (PC00144) | Q89ZX8 | 0.768 | Dehydrogenase (PC00092) | |||

| Q8A5T2 | 0.574 | Isomerase (PC00135) | P94598 | 0.771 | Dehydrogenase (PC00092) | |||

| Q8AAB5 | 0.58 | Phosphodiesterase (PC00185) | Q8A0Q9 | 0.772 | Hydrolase (PC00121) | |||

| Q8A326 | 0.581 | Structural protein (PC00211) | Q8A470 | 0.786 | DNA polymerase (PC00019) | |||

| Q8A414 | 0.584 | Kinase (PC00137) | Q8A8Z9 | 0.791 | Lyase (PC00144) | |||

| Q8A8K6 | 0.59 | Cysteine protease (PC00081) | Q8A1Y1 | 0.8 | Hydrolase (PC00121) | |||

| Q8A5K0 | 0.594 | Serine protease (PC00203) BT_2239 | Q8A0N1 | 0.801 | Hydrolase (PC00121) | |||

| Q8A1S8 | 0.61 | Dehydrogenase (PC00092) | Q8A6B2 | 0.825 | Dehydrogenase (PC00092) | |||

| Q8A1L2 | 0.632 | Protease (PC00190) | Q8A3H7 | 0.828 | Chaperone (PC00072) | |||

| Q8A3Q6 | 0.643 | Glycosidase (PC00110) | Q8A6N9 | 0.84 | Serine protease (PC00203) BT_1838 | |||

| Q89ZB2 | 0.643 | Voltage-gated ion channel (PC00241) | Q8A129 | 0.846 | Serine protease (PC00203) BT_3842 | |||

| Q8AAW1 | 0.644 | Isomerase (PC00135) | ||||||

| aProtein abundance fold-change in BEVs from fasted versus fed mice; bPanther classification (Panther Class ID) | ||||||||

| Accession | Description | (S) / (NS)a | T-test | Protein Class |

| Increased abundance in fasted mice | ||||

| Q03734 | Serine protease inhibitor A3M | 5.01 | 0.013575 | Protease inhibitor |

| Q5ERJ0 | CRS1C-2 alpha-defensin | 3.47 | 0.007428 | Defensin |

| Q9CPY7 | Cytosol aminopeptidase Lap3 | 2.79 | 0.047037 | Aminopeptidase |

| A0A0R4J0I1 | Serine protease inhibitor A3K | 2.682 | 0.03133 | Protease inhibitor |

| Q00898 | Alpha-1-antitrypsin 1-5 (Serpina1e) | 2.117 | 0.010164 | Protease inhibitor |

| Q9CYL5 | Golgi-associated plant pathogenesis-related protein 1 | 2.014 | 0.022046 | - |

| Q8R000 | Organic solute transporter subunit alpha | 2.01 | 0.017694 | Transport |

| Decreased abundance in fasted mice | ||||

| E9Q7Q0 | Mucin-4 | 0.499 | 0.001219 | Cell-matrix adhesion |

| I6L958 | Igk protein | 0.498 | 0.023509 | Immunoglobulin |

| P02816 | Prolactin-inducible protein homolog | 0.489 | 0.01436 | - |

| E9Q035 | Uncharacterized protein | 0.47 | 0.012476 | Transport/Carrier |

| B1AWC9 | Phosphodiesterase | 0.463 | 0.033889 | Phosphodiesterase |

| Q7TQD7 | Myo1b protein | 0.46 | 0.030377 | Actin-binding |

| B2RS76 | Carboxypeptidase B1 (Tissue) | 0.437 | 2.29E-05 | Peptidase |

| Q9CQC2 | Colipase | 0.437 | 0.001193 | Protein-binding activity modulator |

| Q9D2R0 | Acetoacetyl-CoA synthetase | 0.434 | 0.007679 | Ligase |

| Q64444 | Carbonic anhydrase 4 | 0.422 | 0.000349 | Lyase |

| Q4FJZ7 | Ada protein | 0.41 | 0.000154 | Deaminase |

| L7N2D7 | Uncharacterized protein | 0.408 | 0.020565 | - |

| P00688 | Pancreatic alpha-amylase | 0.4 | 0.000298 | Amylase |

| B2RTM0 | Histone H4 | 0.383 | 0.01015 | Metalloprotease |

| Q683Y7 | Immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region | 0.323 | 0.017091 | Immunoglobulin |

| A0A075B677 | Immunoglobulin kappa variable 4-53 | 0.322 | 2.75E-05 | Immunoglobulin |

| Q9Z0Y2 | Phospholipase A2 | 0.273 | 0.001599 | Phospholipase |

| O88952 | Protein lin-7 homolog C | 0.268 | 0.004373 | Cell junction |

| Q6P8U6 | Pancreatic triacylglycerol lipase | 0.255 | 0.000247 | Lipase |

| aRatios > 2 or < 0.5 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).